ABSTRACT

The marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri initiates symbiotic colonization of its squid host, Euprymna scolopes, by forming and dispersing from a biofilm dependent on the symbiosis polysaccharide locus (syp). Historically, genetic manipulation of V. fischeri was needed to visualize syp-dependent biofilm formation in vitro, but recently, we discovered that the combination of two small molecules, para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA) and calcium, was sufficient to induce wild-type strain ES114 to form biofilms. Here, we determined that these syp-dependent biofilms were reliant on the positive syp regulator RscS, since the loss of this sensor kinase abrogated biofilm formation and syp transcription. These results were of particular note because loss of RscS, a key colonization factor, exerts little to no effect on biofilm formation under other genetic and medium conditions. The biofilm defect could be complemented by wild-type RscS and by an RscS chimera that contains the N-terminal domains of RscS fused to the C-terminal HPT domain of SypF, the downstream sensor kinase. It could not be complemented by derivatives that lacked the periplasmic sensory domain or contained a mutation in the conserved site of phosphorylation, H412, suggesting that these cues promote signaling through RscS. Lastly, pABA and/or calcium was able to induce biofilm formation when rscS was introduced into a heterologous system. Taken together, these data suggest that RscS is responsible for recognizing pABA and calcium, or downstream consequences of those cues, to induce biofilm formation. This study thus provides insight into signals and regulators that promote biofilm formation by V. fischeri.

IMPORTANCE Bacterial biofilms are common in a variety of environments. Infectious biofilms formed in the human body are notoriously hard to treat due to a biofilm’s intrinsic resistance to antibiotics. Bacteria must integrate signals from the environment to build and sustain a biofilm and often use sensor kinases that sense an external signal, which triggers a signaling cascade to elicit a response. However, identifying the signals that kinases sense remains a challenging area of investigation. Here, we determine that a hybrid sensor kinase, RscS, is crucial for Vibrio fischeri to recognize para-aminobenzoic acid and calcium as cues to induce biofilm formation. This study thus advances our understanding of the signal transduction pathways leading to biofilm formation.

KEYWORDS: RscS, Vibrio fischeri, biofilms, calcium signaling, pABA, sensor kinase, signal transduction

INTRODUCTION

Two-component systems are the predominant way that bacteria sense and respond to their environment (1). At their most basic level, these systems consist of two main proteins, the sensor histidine kinase (SK) and a cognate response regulator (RR). SKs sense signals from the environment through their sensory domains, resulting in autophosphorylation and a signal cascade that leads to activation (or inhibition) of the cognate RR, causing altered physiology, often via a change in gene expression (2–6).

More complex forms of the SK are known as hybrid sensor kinases (1). These SKs contain two to three domains involved in phospho-transfer: the histidine kinase/ATPase (HATPase) domain, the response regulator-like receiver (Rec) domain and the histidine phosphotransferase (HPT) domain (3, 7). Once the sensory domain senses a signal, a conserved histidine within the HATPase domain becomes phosphorylated. Subsequently, the phosphoryl group is transferred to an aspartic residue within the Rec domain and, lastly, to a histidine within an HPT domain (within the same protein or in a separate protein). The phosphoryl group is then donated to the RR (1). Once the RR is phosphorylated, it typically undergoes a conformational change that allows it to activate its effector domain and change the signaling output (1).

Vibrio fischeri, a Gram-negative marine bacterium, utilizes many two-component regulators to sense changes in the environment during its life cycle (8). V. fischeri transitions from a planktonic state in the sea to form a one-to-one symbiotic relationship within the light organ of the Hawaiian bobtail squid Euprymna scolopes. Initiating this symbiosis involves key steps that result in successful squid colonization by V. fischeri (9, 10). One of these steps is the formation of a biofilm-like aggregate of cells on the surface of the squid’s light organ. Previous work has shown that disruption of genes within the biofilm-promoting symbiosis polysaccharide (syp) locus causes a severe defect in squid colonization and loss of symbiotic aggregate formation (11–13). Conversely, strains with increased syp-dependent biofilm formation in culture produce larger symbiotic aggregates and outcompete their parent for colonization (11–15).

Control over symbiosis-relevant biofilm formation has been intensively probed in the best-studied V. fischeri squid isolate, ES114. This strain contains an 18-gene syp locus that is tightly regulated at the level of transcription by a number of two-component regulators (Fig. 1). The syp regulatory network was originally uncovered using genetically manipulated strains that overexpressed a positive regulator (RscS, SypF, or SypG) and/or lacked a negative regulator (SypE or BinK) (12, 15–21). In laboratory culture, these strains form strong syp-dependent biofilms, such as wrinkled colonies on solid agar and cohesive pellicles in static liquid culture. In contrast, their wild-type (WT) parent ES114 fails to produce syp-dependent biofilms, instead displaying smooth, unsticky colonies and turbid static cultures that lack a cohesive pellicle. The enhanced phenotypes of the engineered strains in vitro correspond to augmented phenotypes in the context of symbiosis. For example, overproduction of RscS resulted not only in hyperbiofilm formation in culture but also increased aggregation in the squid and the ability to outcompete the WT strain for symbiotic colonization (12). Correspondingly, mutants for rscS, sypF, sypG, and hahK were deficient in squid colonization and the latter three for biofilm formation in culture (8, 19, 20, 22, 23). The strong correlation between the biofilm phenotypes in vitro and in vivo suggests that the mechanisms uncovered in culture are relevant to symbiosis.

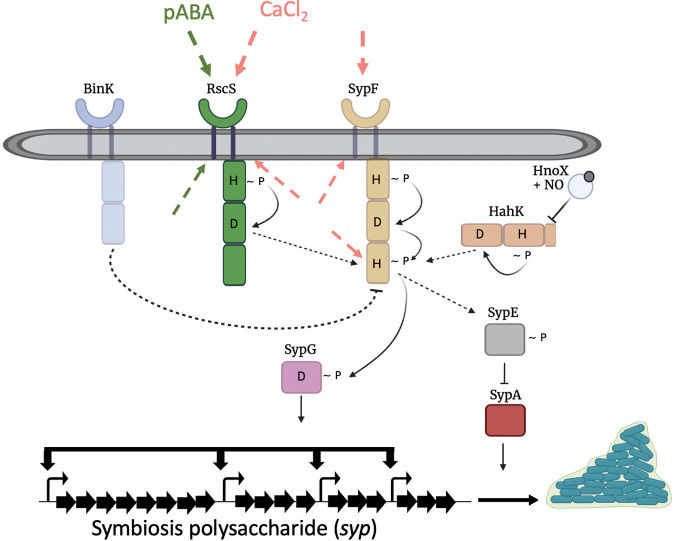

FIG 1.

Model of biofilm regulation in V. fischeri. Many two-component regulators positively and negatively regulate biofilm formation through control of syp transcription and eventual SYP production. Our current evidence suggests that the hybrid sensor kinase, RscS, responds to pABA or a downstream effector, in the presence of calcium, to promote biofilm formation. The green and pink dashed arrows represent potential sensory regions for recognizing pABA and calcium (or their downstream consequences), respectively, including the periplasmic loop region and PAS domain (not shown) of RscS and the periplasmic loop region, HAMP domain (not shown), and HPT domain of SypF. These cues appear to promote an RscS-dependent phosphorelay that drives the activation of the response regulator SypG via the HPT domain of the sensor kinase SypF. Another hybrid sensor kinase, HahK, also functions upstream of SypF’s HPT domain to promote biofilm formation. There are also three negative regulators: HnoX, BinK, and SypE. HnoX, a nitric oxide-binding protein, inhibits biofilm formation by controlling HahK activity and thus syp transcription. BinK, a hybrid sensor kinase, is a strong negative regulator of syp transcription that may remove phosphoryl groups from SypF. Finally, the response regulator SypE controls biofilm formation posttranscriptionally by inhibiting the activity of the positive regulator SypA. For simplicity, monomer forms of the proteins are shown. This figure was exported under a paid subscription. Image created with BioRender.com.

The current model of the regulatory network that controls SYP-dependent biofilm is shown in Fig. 1. The RR SypG directly induces syp gene transcription, resulting in production of proteins that synthesize and export SYP (12, 16, 18). Activation of SypG, in turn, occurs by phosphorylation via the SK SypF. SypF acts as a central regulator due to the fact that its HPT domain is necessary and sufficient for syp transcription and biofilm formation induced by two other SKs, RscS, and HahK (19–21, 24). For example, overproduction of RscS induces biofilm formation dependent on SypF, and more specifically, on the HPT domain of SypF (20). Furthermore, overproduction of an RscS-SypF hybrid that contained the HPT domain of SypF in place of its own HPT domain permitted induction of biofilm formation even in the absence of SypF (20). Similarly, the effect of the SK HahK depends on the HPT domain of SypF (19). In addition to controlling the activation state of SypG, RscS functions upstream of a second response regulator, SypE, via SypF (14, 20, 25). In turn, SypE modulates the activity of the small STAS domain protein, SypA, which promotes biofilm formation in an unknown manner (26). Finally, the hybrid sensor kinase BinK (15, 27) is a key negative regulator whose loss permits an otherwise wild-type strain to form substantial SYP-dependent biofilms when calcium is present (19). BinK’s negative activity depends on its putative sites of phosphorylation, and thus it may function as a phosphatase to prevent/reduce signaling through SypF (28).

The ability of RscS to induce biofilm formation was firmly established through overexpression studies; however, a mutant phenotype for the rscS gene, outside of a requirement for squid colonization, has been somewhat elusive. Indeed, the only in vitro phenotype for a strain lacking rscS was found in the context of a complicated mutant background: a strain that lacked the negative regulator BinK and the positive activators SypF and HahK and expressed only the HPT domain of SypF. Residual biofilm formation of this base strain was disrupted with deletion of rscS (19). Together, these data implied that, while RscS clearly makes a contribution to host colonization via biofilm induction, its role under standard laboratory conditions was modest at best.

Recently, we discovered laboratory conditions, TBS (tryptone broth salt) medium supplemented with calcium (Ca) and the vitamin para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA), that promoted syp-dependent biofilm formation by WT strain ES114 in culture (29). Transcription of syp was induced only when both Ca and pABA were added, suggesting that these molecules provide coordinate signaling. However, how these conditions promote syp transcription and biofilm formation remained unknown.

Here, we find that RscS is crucial for pABA- and calcium-induced biofilm formation since the loss of RscS abrogates biofilm formation, suggesting that RscS might represent the main sensory input under these conditions. Furthermore, expression of an RscS-SypF chimera that contains the N-terminal domains of RscS fused to the C-terminal HPT domain of SypF promoted biofilm formation in the double sypF rscS mutant in response to pABA and Ca. Lastly, pABA and/or calcium was able to induce biofilm formation when rscS was introduced into a heterologous system that does not normally promote biofilm in response to these additives. Taken together, these results suggest that RscS responds to pABA and calcium to induce ES114 biofilm formation.

RESULTS

pABA/calcium-induced biofilm formation requires SypF and SypG.

Our recent discovery that supplementation of a tryptone-based medium with pABA and calcium (TPC) promotes syp transcription and biofilm formation by WT strain ES114 (29) prompted us to reevaluate the established syp regulatory network. To begin to determine which syp regulator(s) are important for ES114 to produce a biofilm, we assessed biofilm formation using deletion mutants of sypG and sypF grown on TPC. The sypG and the sypF deletions disrupted biofilm formation on pABA/calcium, as evident from the lack of colony stickiness in the “toothpick assay” and could be complemented fully (Fig. 2A and B). Furthermore, SypG and SypF were also required for pABA/calcium-mediated induction of syp transcription (Fig. 2C). Together, these data support our previous conclusion that these biofilms are syp dependent (29).

FIG 2.

The HPT domain of SypF is necessary and sufficient for biofilm formation in TBS containing pABA and Ca2+. (A) Colony biofilm formation was evaluated following growth on tTBS with pABA and calcium (TPC) of the following strains: WT ES114, the ΔsypG mutant (KV1787), the sypG complement (KV6475), the ΔsypF mutant (KV5367), the sypF complement (KV6659), and the sypF mutant complemented with only the SypF HPT domain (KV7226). Pictures were taken using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope with ×6.5 magnification at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of three separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. Dotted arrows represent where “pulling” was observed but to a lesser extent, with portions of the colony breaking off during disruption. (B) Biofilm cohesion was quantified from images as described in Materials and Methods with scores of 1 assigned to a null phenotype and 4 to the most biofilm formation/the strongest phenotypes (most/strongest). Statistics for panel B were performed via a one-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where biofilm strength was the dependent variable. *, P = 0.0210; **, P = 0.0017; ****, P < 0.0001. (C) sypA promoter activity (Miller units) was measured using a PsypA-lacZ reporter present in the parent (KV8079) and ΔsypG and ΔsypF derivatives (KV10307 and KV10317, respectively) following subculture for 22 h in tTBS (T), tTBS+calcium (TC), tTBS+pABA (TP), and tTBS+pABA/calcium (TPC). Statistics for panel C were performed via a two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where Miller units was the dependent variable. ****, P < 0.0001.

Past work with different media and inducing conditions demonstrated that SypF’s HPT domain alone (i.e., SypF missing its sensory, kinase/phosphatase, and REC domains) was sufficient to restore biofilm formation to a sypF deletion mutant (20). We therefore wondered whether the same was true in the context of ES114 and pABA/calcium conditions. Indeed, the HPT domain of SypF alone was able to partially restore biofilm formation to the ΔsypF mutant, albeit to a lesser extent than full-length SypF: the ΔsypF mutant that expressed SypF-HPT consistently displayed slightly stronger cohesion than the ΔsypF mutant, but some parts of the colony were left behind following disruption (dashed arrow in Fig. 2A; Fig. 2A and B). These data indicated that the sensory and autophosphorylation domains of SypF are not essential for ES114 to produce biofilms in response to pABA/calcium and suggested that one of the other sensor kinases, HahK or RscS (Fig. 1), may be necessary for syp induction under these conditions.

HahK and HnoX are not required for pABA/Ca-induced biofilms.

In the absence of the negative regulator BinK expressing only SypF-HPT, HahK exerts a considerable positive influence over SYP-dependent biofilm formation; in turn the nitric oxide-binding protein HnoX inhibits the activity of HahK, thus impairing biofilm formation (19, 23, 30). We therefore hypothesized that these two regulators would also have a significant impact under TPC conditions. We thus evaluated biofilm formation by hahK and hnoX single deletion mutants as well as the double mutant on TPC. Under TPC conditions, we noted no differences in any of the mutants (Fig. 3A and C). Not surprisingly, given its lack of impact on biofilm formation, deletion of hahK also exerted no impact on syp transcription (Fig. 4). These data suggest that the HahK regulator is not important under these conditions, unlike its key requirement under the conditions previously assayed (19).

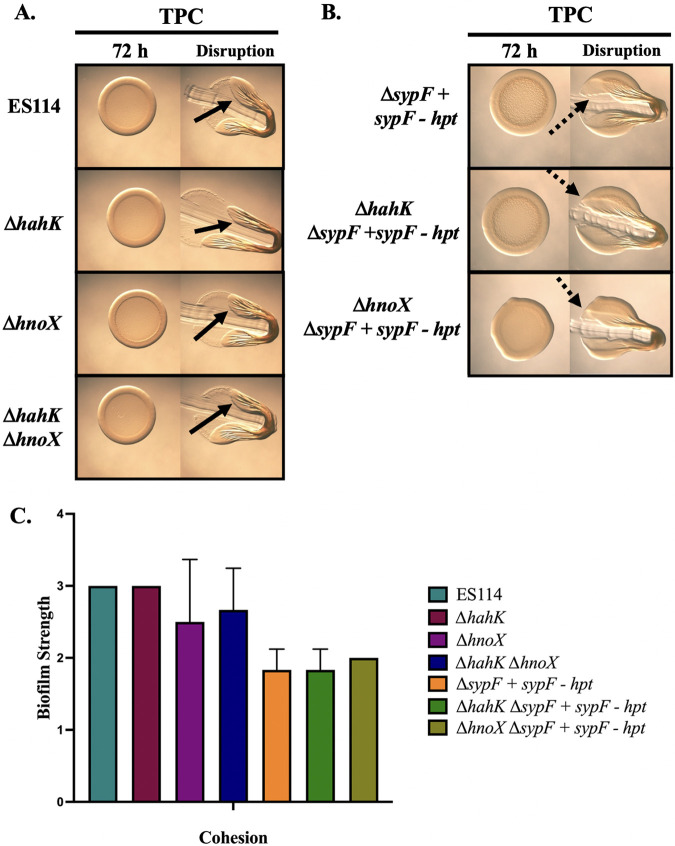

FIG 3.

HahK and HnoX are not required for pABA/calcium induced biofilms. (A) Colony biofilm formation was evaluated following growth on TPC of the following strains: WT (ES114), ΔhahK (KV7964), ΔhnoX (KV8025), and ΔhahK ΔhnoX (KV8484) strains. (B) Colony biofilm formation was evaluated following growth on TPC of the following strains: ΔsypF+sypF-hpt (KV7226) (same image as Fig. 2A), ΔhahK ΔsypF+sypF-hpt (KV9968), and ΔhnoX ΔsypF+sypF-hpt (KV10226). The data in this panel were obtained at the same time as those in Fig. 2A, and the ΔsypF+sypF-hpt is repeated here to facilitate comparisons across figures. Pictures were taken using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope (×6.5 magnification) at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of three separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. Dotted arrows represent where “pulling” was observed but to a lesser extent, with portions of the colony breaking off during disruption. (C) Biofilm cohesion was quantified from images as described in Materials and Methods with scores of 1 assigned to a null phenotype and 4 to the most/strongest. Statistics for panel C were performed via a one-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where biofilm strength was the dependent variable. No significance was reached.

FIG 4.

RscS is required for the induction of syp transcription. sypA promoter activity (Miller units) was measured using a PsypA-lacZ reporter fusion in the parent strain (KV8079) or ΔrscS or ΔhahK derivatives (KV9653 and KV10304, respectively) following subculture for 22 h in tTBS (T), TC, TP, and TPC. Statistics were performed via a two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where Miller unit(s) was the dependent variable. ****, P < 0.0001.

In the strain discussed above, SypF is fully intact and thus its activity may diminish the need for HahK. We, therefore, evaluated biofilm formation by a ΔsypF sypF-hpt mutant containing the ΔhahK deletion. However, under TPC conditions, neither the ΔhahK nor the ΔhnoX mutation disrupted the slight biofilm formation of the ΔsypF sypF-hpt strain (Fig. 3B and C). Together, these data indicate that HahK is not critical for biofilms induced under TPC conditions.

RscS is critical for pABA/calcium-stimulated ES114 biofilms.

Because hahK was not required for biofilm formation under pABA/calcium conditions, we focused our attention on the only other known positive regulator, RscS (Fig. 1). Given the lack of in vitro phenotypes for an rscS mutant under other conditions (19), we were surprised to see that deletion of rscS abrogated biofilm formation on TPC (Fig. 5A and C). This was true both in the context of the wild-type strain and in the ΔsypF mutant that expresses only SypF-HPT (Fig. 5A and C). We confirmed the importance of RscS by complementing the deletion mutant with rscS expressed from its own promoter in single copy at a nonnative site in the chromosome. In contrast to other described rscS alleles that can promote biofilm formation on a variety of media not typically permissive for biofilm formation by the WT strain (e.g., rscS1 expressed from pKG11 [12, 19, 31]), this allele of rscS complemented without overcomplementing. In other words, it restored the wild-type phenotype rather than causing a hyper-biofilm forming phenotype and did not promote biofilm formation on other media types such as the tryptone-containing medium tTBS (T) (29) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These data thus reveal, for the first time, conditions (TPC) under which RscS plays a key and active role in inducing biofilm formation.

FIG 5.

RscS is critical for pABA-stimulated ES114 biofilms. (A) Colony biofilm formation was evaluated following growth on TPC of the following strains: WT (ES114), ΔrscS (KV10130), ΔrscS+rscS (KV10166), ΔsypF+sypF-hpt (KV7226), and ΔrscS ΔsypF+sypF-hpt (KV9953). Pictures were taken using a Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope with ×6.5 magnification at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of three separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. Dotted arrows represent where “pulling” was observed but to a lesser extent, with portions of the colony breaking off during disruption. (B) Colony biofilm formation was evaluated following growth on TPC of the following strains: sypG-D53E (sypG*; KV6527), ΔrscS+sypG* (KV10391), ΔsypE+sypG* (KV10444), and ΔrscS ΔsypE+sypG* (KV10442). Pictures were taken using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope with ×6.5 magnification at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of 3 separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. Dotted arrows represent where “pulling” was observed but to a lesser extent, with portions of the colony breaking off during disruption. For both sypG* ΔsypE derivatives (with or without an intact rscS), the colony biofilms were adherent to the plate and were not perturbable using the toothpick assay. (C) Biofilm cohesion was quantified from images as described in Materials and Methods with scores of 1 assigned to a null phenotype and 4 to the most/strongest. Statistics for panel C were performed via a one-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where biofilm strength was the dependent variable. **, P < 0.0094; ***, P = 0.0003; ****, P < 0.0001.

RscS is required for induction of both syp transcription and posttranscriptional events.

RscS, when overproduced from multicopy plasmid pKG11, indirectly promotes biofilm formation both by activating SypG and thus syp transcription and by inhibiting the negative activity of SypE (14) (Fig. 1). To investigate the mechanism(s) underlying the requirement for RscS in TPC-induced biofilm formation, we first probed syp transcription. Deletion of rscS abrogated syp transcription under all conditions, including pABA/calcium (Fig. 4). Given that RscS is important for syp transcription, we wondered whether the expression of a constitutively active version of SypG (SypG-D53E or SypG* [20]) would override the need for RscS for biofilm formation under TPC conditions. We found that, even when the strain expresses SypG*, an rscS deletion abrogates biofilm formation on TPC (Fig. 5B and C). The requirement for RscS even when syp transcription is constitutively activated suggests that this regulator also functions at another level to control biofilm formation.

We thus explored the possibility that, under pABA/Ca conditions, RscS is also involved posttranscriptionally via phosphorylation of SypE, which inhibits the positive regulator SypA (Fig. 1) (14, 25, 26). Indeed, deleting sypE from the ΔrscS sypG* mutant rescued biofilm formation and largely phenocopied the ΔsypE sypG* mutant (Fig. 5B and C); minor differences in colony appearance indicate that RscS may play another as-yet unknown role. Altogether, these data support the conclusion that RscS is crucial for upregulating syp transcription as well as posttranscriptional events and thus biofilm formation under pABA/calcium conditions.

pABA/calcium does not induce rscS transcription.

We hypothesized that the relative importance of RscS under TPC conditions could stem from either (i) an upregulation of rscS transcription, resulting in increased RscS protein and thus a greater ability for RscS to contribute to the signal transduction cascade, akin to the RscS overexpression constructs previously used (see, for example, reference 12), and/or (ii) the addition/generation of a signal(s) to which RscS responds. To test the first hypothesis, we evaluated rscS transcription under T, tTBS+calcium (TC), tTBS+pABA (TP), and tTBS+pABA/calcium (TPC) conditions and found that rscS transcription was not upregulated under any circumstance (see Fig. S2). These data demonstrate that the pABA/calcium condition does not exert its effects at the level of rscS transcription. Instead, it might be signaling through RscS to upregulate syp transcription and posttranscriptional events necessary for SYP-dependent biofilms.

Periplasmic loop sequences and the conserved site of autophosphorylation are crucial for RscS function.

We hypothesized that RscS might sense pABA and/or calcium to induce the biofilm phenotypes observed under pABA/calcium conditions. RscS has two sensory domains, a cytoplasmic PAS domain that is vital for function and a periplasmic loop that plays a negative role under certain conditions: overproduction of either of two periplasmic loop deletion mutants promoted phenotypes similar to those induced by overproduction of WT RscS (e.g., wrinkled colony and pellicle formation), but relative to the control caused increased aggregate formation in shaking liquid and enhanced attachment as measured by a crystal violet assay (32). However, that work made use of alleles derived from the multicopy plasmid pKG11; in the context of this plasmid, RscS is overproduced, both by virtue of two promoters (lac and native promoters) activating transcription and by the presence of two regulatory mutations that appear to increase protein production to levels sufficient to promote robust biofilm formation by ES114 (12, 32). To avoid the complications inherent in that overexpression approach (such as the ability to bypass the need for an inducing signal) and to specifically test the requirement of the periplasmic loop region in pABA/calcium signaling, we developed the same large periplasmic loop deletion mutant (Δpp-loop) but in the context of the single copy rscS allele expressed from its native promoter in the chromosome used above. In contrast to what was previously observed for overexpression, we found that the Δpp-loop allele failed to complement the ΔrscS mutant (see Fig. S3).

We also tested a role for H412, the predicted site of autophosphorylation (32), by analyzing an ΔrscS mutant carrying rscS-H412Q. This strain failed to produce biofilms on TPC (see Fig. S3), indicating that the histidine within the HATPase domain is necessary for RscS to induce biofilm formation on pABA/calcium conditions. Overall, these data demonstrate the requirement for key sensory and signal transduction elements in RscS, consistent with the possibility that RscS may be responsible for responding to pABA and/or calcium, potentially through signaling from the external/periplasmic space, and relaying a positive signal to promote biofilm formation.

Multicopy rscS induces biofilm formation and syp transcription under pABA/calcium conditions.

We hypothesized that RscS might respond to pABA and/or calcium. To test this possibility, we expressed extra copies of RscS using multicopy plasmid pLMS33, predicting that this might allow for greater signal input and transmission. This rscS expression plasmid differs from pKG11 described above in that it lacks the regulatory region mutations present in pKG11. As a result, pLMS33 fails to induce sticky biofilm formation when carried by wild-type strain ES114 grown on LBS (12) (see Fig. S4). In contrast, when the same strain was grown on T, TC, TP, or TPC media, which lack the yeast extract known to be inhibitory (29), biofilms formed to various extents. Whereas the vector control strain only displayed biofilm formation on TPC, the pLMS33-containing strain formed colonies that trended toward increased biofilm formation on unsupplemented T and TP plates and those that were significantly more robust on TC (Fig. 6). The finding that visually, partial biofilms could form under pABA-only (TP) conditions was notable, as this condition was not permissive to biofilm formation for other strains (e.g., the ΔbinK mutant [29]). Moreover, and most strikingly, the presence of both signals, pABA and calcium, caused a substantial increase in biofilm formation, with the colonies gaining substantial architecture and becoming adherent to the agar surface (Fig. 6). Together, our data suggest that the addition of these two cues causes a synergistic effect dependent on the presence of RscS.

FIG 6.

Multicopy expression of rscS induces biofilm formation on medium containing pABA/calcium. (A) Colony biofilm formation was assessed following growth on tTBS (T), TC, TP, and TPC of the following strains: ES114/pKV69 (vector control) and ES114/pLMS33 (wild-type rscS on a plasmid; pRscS). Pictures were taken using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope (×6.5 magnification) at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of three separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. Dotted arrows represent where “pulling” was observed but to a lesser extent, with portions of the colony breaking off during disruption. (B) Biofilm cohesion was quantified from images as described in Materials and Methods with scores of 1 assigned to a null phenotype and 4 to the most/strongest. Statistics for panel C were performed via a two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where biofilm strength was the dependent variable. *, P = 0.0170; **, P < 0.0071; ****, P < 0.0001.

We saw the same trends when we evaluated syp transcription under these conditions. The vector control strain exhibited increased syp transcription under TC and TPC conditions (Fig. 7). Conversely, the pLMS33-containing strain exhibited increased transcription under both TC and TP conditions and a substantial increase under the TPC condition (Fig. 7). These results support the notion that RscS might be responsible for sensing and responding to pABA and calcium or pABA/calcium-induced changes.

FIG 7.

Multicopy expression of rscS induces syp transcription in response to pABA and calcium. sypA promoter activity (Miller units) was measured following a 22-h subculture in tTBS (T), TC, TP, and TPC of the PsypA-lacZ reporter strain KV8079 that contained either pKV69 (vector control [VC]) or pLMS33 (pRscS). Statistics were performed via a two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where Miller unit(s) was the dependent variable. ****, P < 0.0001.

Due to the known requirement for SypF’s HPT domain in RscS-induced biofilm formation (20), we reasoned that the increase in biofilm formation due to rscS overexpression would also rely on an intact SypF or, at least, an intact HPT domain. Indeed, when pLMS33 was introduced into a ΔsypF mutant, no biofilm formation occurred (Fig. 8A, B, and E). In contrast, when pLMS33 was introduced into the ΔsypF sypF-hpt strain, robust, sticky biofilms formed under all conditions except T (Fig. 8C to E). Altogether, these data indicate that RscS is critical for pABA and calcium signaling, dependent on the HPT domain of SypF.

FIG 8.

Multicopy expression of rscS induces biofilm formation dependent on SypF’s HPT domain. Colony biofilm formation was assessed following growth on tTBS (T), TC, TP, and TPC of the following strains: ΔsypF (KV5267) with either pKV69 (vector control) (A) or pLMS33 (wild-type rscS; pRscS) (B), ΔsypF + sypF-hpt (KV7226) with either pKV69 (vector control) (C) or pLMS33 (pRscS) (D). Pictures were taken using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope (×6.5 magnification) at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of three separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. Dotted arrows represent where “pulling” was observed but to a lesser extent, with portions of the colony breaking off during disruption. (E) Biofilm cohesion was quantified from images as described in Materials and Methods with scores of 1 assigned to a null phenotype and 4 to the most/strongest. Statistics were performed via a two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where biofilm strength was the dependent variable. **, P = 0.0073; ****, P < 0.0001.

We wondered whether we would obtain similar results if we overexpressed another sensor kinase in the pathway, SypF. However, a plasmid that expresses wild-type sypF failed to induce a biofilm on pABA alone (Fig. 9). Furthermore, this strain did not exhibit increased biofilm formation in the TPC condition; rather, it trended toward decreased biofilm formation (Fig. 9). Taken together, these data suggest that it is specifically RscS that is key for pABA/calcium-induced biofilm formation.

FIG 9.

Multicopy expression of sypF does not induce biofilm formation on tTBS+pABA medium. Colony biofilm formation was assessed following growth on TP and TPC of ES114 carrying either (A) pKV69 (vector control) or (B) pCLD54 (pSypF). Pictures were taken using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope (×6.5 magnification) at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of three separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. Dotted arrows represent where “pulling” was observed but to a lesser extent, with portions of the colony breaking off during disruption. (C) Biofilm cohesion was quantified from images as described in Materials and Methods with scores of 1 assigned to a null phenotype and 4 to the most/strongest. Statistics were performed via a two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where biofilm strength was the dependent variable. *, P = 0.0121; ***, P = 0.0005.

An RscS-SypF chimera is able to relay the pABA/calcium signal to promote biofilm formation.

To further test the possibility that RscS can respond to the pABA/calcium conditions, we generated an RscS-SypF chimera (20) (Fig. 1) in which RscS’s HPT domain was replaced with that of SypF’s and expressed it from the chromosome at a nonnative site under the control of the rscS promoter. In this set-up, RscS is forced to relay its signaling through the SypF HPT domain to donate phosphoryl groups to downstream response regulators such as SypG. We first tested whether this chimera was functional by complementing the individual ΔrscS and ΔsypF mutants. The chimera complemented both single deletion mutants, indicating that the chimera is functional and that RscS’s HPT domain is not necessary under these conditions to relay its signal(s) to control biofilm formation (Fig. 10A, B, and E). Of note, the chimera not only complements the ΔsypF mutant but also promotes biofilm formation by that strain on pABA alone and more substantially on pABA/Ca (Fig. 10B and E). These data indicate four things: (i) full-length SypF inhibits biofilm formation under pABA conditions in the absence of calcium, (ii) expression from two copies of rscS is sufficient to induce biofilm formation on pABA alone when only the HPT domain of SypF is present; (iii) the data obtained via rscS overexpression by pLMS33 were not an artifact of overexpressing rscS since, even in single copy, we obtain similar results for pABA and pABA/Ca in the absence of sypF; and (iv) it is the coordinate signaling between pABA and calcium that induces significant biofilm formation.

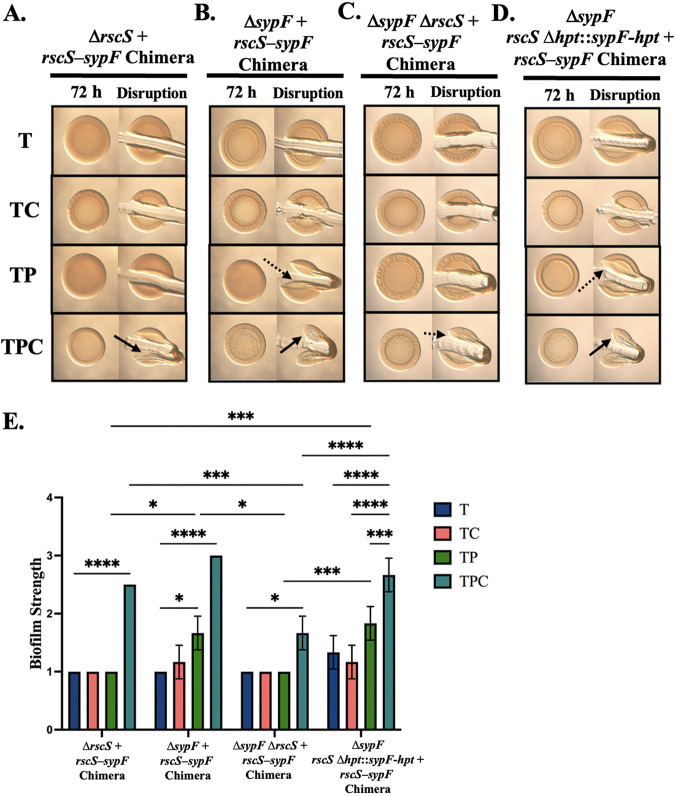

FIG 10.

The RscS-SypF chimera can complement rscS and sypF deletions. Colony biofilm formation was evaluated following growth on tTBS (T), TC, TP, and TPC of the following strains: ΔrscS+rscS-sypF chimera (KV10302) (A), ΔsypF+rscS-sypF chimera (KV10355) (B), ΔsypF ΔrscS+rscS-sypF chimera (KV10351) (C), and ΔsypF rscS Δhpt::sypF-hpt+rscS-sypF chimera (KV10397) (D). Pictures were taken using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope with ×6.5 magnification at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of three separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. Dotted arrows represent where “pulling” was observed but to a lesser extent, with portions of the colony breaking off during disruption. (E) Biofilm cohesion was quantified from images as described in Materials and Methods with scores of 1 assigned to a null phenotype and 4 to the most/strongest. Statistics were performed via a two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where biofilm strength was the dependent variable. *, P = 0.0122; ***, P = 0.0007; ****, P < 0.0001.

When we assessed the ability of the chimera to complement the ΔrscS ΔsypF double mutant, we observed only relatively weak biofilm formation indicated by the dashed line (Fig. 10C and E). We hypothesized that biofilm formation on TPC relies on coordinate signaling, presumably through the use of two sensor kinases; in the double mutant strain containing the chimera, there is only one sensory input. Therefore, we constructed a strain that contains the chimera both at the nonnative position as well as at rscS’s native site in the chromosome by replacing the HPT domain of rscS with that of sypF (rscS Δhpt::sypF-hpt). The presence of two copies of the chimera not only fully complements the double mutant on TPC but also modestly promotes biofilm formation on pABA alone, similar to the ΔsypF+chimera mutant (Fig. 10D and E). These data further demonstrate the importance of RscS in recognizing the pABA/calcium cues and also indicate that there may be a need for two sensors to elicit biofilm formation in ES114.

RscS responds to pABA, calcium, and pABA/calcium in a heterologous system.

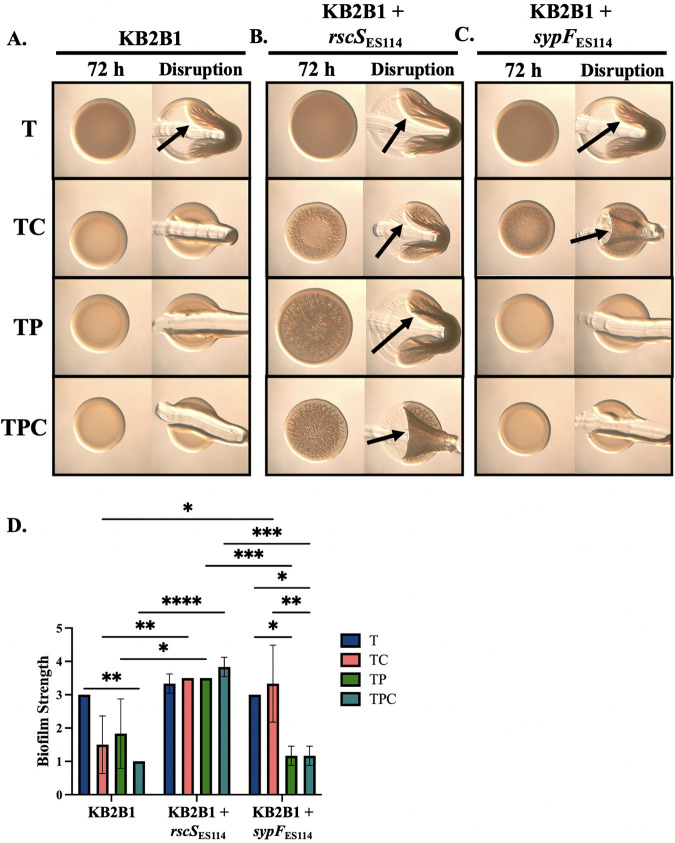

To further explore the possibility that RscS responds to pABA and/or calcium, we used V. fischeri strain KB2B1 as a heterologous system. KB2B1 is another WT strain isolated from E. scolopes and has been termed “dominant” due to its ability to dominate in colonization relative to ES114 (33). KB2B1 also contains a degenerate rscS (34). It readily forms a biofilm under LBS (34) and tTBS conditions but fails to consistently do so when either pABA or calcium is added to tTBS. Importantly, the addition of both pABA and calcium to tTBS completely disrupts biofilm formation by KB2B1 (Fig. 11). Therefore, we reasoned that if the RscS from ES114 can promote biofilm formation in response to pABA/calcium, then inserting the rscS gene into the KB2B1 chromosome might permit KB2B1 to form a biofilm in response to both additives. Strikingly, we saw a significant increase in biofilm formation when KB2B1 expressing RscSES114 was grown on plates that contained pABA or calcium alone. Furthermore, consistent with the ES114 experiments, KB2B1 expressing RscSES114 also formed strong sticky biofilms on TPC plates (Fig. 12). These effects did not depend on the remnant of rscS present in the genome, since deleting the degenerate gene did not impact the biofilm phenotypes (see Fig. S5). Finally, pABA-induced biofilm formation was not due just to the presence of an extra sensor kinase as expression of sypFES114 at the same nonnative site in KB2B1 did not permit biofilm formation on pABA or pABA/calcium conditions (Fig. 12C and D). Of note, SypFES114 did promote biofilm formation upon calcium supplementation; further investigation will be needed to dissect SypF’s role with respect to calcium and whether SypF and RscS contribute additively to calcium-induced biofilms. The rscSES114-dependent increase in biofilm formation under conditions that normally do not permit KB2B1 to form a biofilm supports the conclusion that RscS is responsible for responding to pABA/calcium.

FIG 11.

KB2B1 readily forms a biofilm on all LBS media but not all tTBS media. (A) Colony biofilm formation was evaluated following growth on LBS (L), LBS+calcium (LC), LBS+pABA (LP), LBS+pABA/calcium (LPC), tTBS (T), TC, TP, and TPC of WT KB2B1. Pictures were taken using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope (×6.5 magnification) at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of three separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. (B) Biofilm cohesion was quantified from images as described in Materials and Methods with scores of 1 assigned to a null phenotype and 4 to the most/strongest. Statistics were performed via a one-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where biofilm strength was the dependent variable. **, P = 0.0025.

FIG 12.

RscS responds to pABA and calcium in a heterologous system. Colony biofilm formation was evaluated following growth on tTBS (T), TC, TP, and TPC of the following strains: WT KB2B1 (A), KB2B1+rscSES114 (KV10409) (B), and KB2B1+sypFES114 (KV10389) (C). Pictures were taken using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope (×6.5 magnification) at 72 h before and after disruption using a toothpick. Pictures are representative of three separate experiments. Arrows indicate where “pulling,” indicating cohesion, was observed. (D) Biofilm cohesion was quantified from images as described in Materials and Methods with scores of 1 assigned to a null phenotype and 4 to the most/strongest. Statistics were performed via a one-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, where biofilm strength was the dependent variable. *, P < 0.0342; **, P < 0.006; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

V. fischeri strain ES114 uses a complex regulatory network to control biofilm formation (Fig. 1). This regulation was uncovered using in vitro analyses that relied on the use of overexpression of putative regulators and/or genetically convoluted strain backgrounds. These experiments were grounded in and/or confirmed by squid colonization experiments (12, 15–21). For example, the sensor kinase RscS was first identified as critical for squid colonization, then subsequently shown by overexpression studies to be an important positive regulator of biofilm formation both in vitro and during colonization (12, 19, 24). However, the impact on biofilm formation of an rscS deletion in any strain background was negligible, while other regulators, such as HahK, played more substantial roles, calling into question the significance of the contribution made by RscS (19). Here, we show that, under pABA/calcium growth conditions, RscS is a critical regulator. This study not only lends support to the regulatory scheme uncovered in the past but also validates the continued exploration of the syp signal transduction network under these conditions that appear to be more biologically relevant.

Historically, LBS, not tTBS, was used as the base medium for biofilm studies of ES114. The two media differ only by the presence of yeast extract in the former. The substantial biofilms formed by a ΔbinK mutant grown in LBS with calcium rely predominantly on HahK, not RscS (19). In contrast, when wild-type strain ES114 is grown in tTBS with pABA/calcium, HahK is dispensable for biofilm formation (Fig. 3). There are many differences between those two sets of experiments, including strain background and growth media, making it difficult to explain why the balance of control shifts. However, one possible explanation could be that the relative amount of nitric oxide differs under the two conditions. HahK is negatively regulated by the nitric oxide (NO)-binding protein HnoX (19, 30); therefore, it is possible that BinK and/or yeast extract could alter the amounts of intrinsically produced NO, which in turn would impact the ability of HahK to make a contribution to biofilm induction. In any event, it is clear from recent studies that yeast extract turns off multiple pathways important for the host environment, and the use of tTBS, particularly with supplements such as pABA and calcium, will likely continue to provide insights into biofilm formation and potentially other symbiosis-relevant traits of V. fischeri (29, 35).

Our working model is that RscS functions by sensing and/or responding to pABA and calcium, potentially as external cues (Fig. 1). However, our current data cannot distinguish that possibility from the alternative model that RscS responds to downstream consequences of the pABA/calcium environment to upregulate biofilm formation. For example, RscS may instead respond to the second messenger c-di-GMP (36), which is known to be increased in pABA/calcium conditions and under high calcium conditions (29, 37). Other scenarios are also possible, such as direct recognition of one of these two molecules, and indirect recognition of the other, or recognition of other metabolic changes induced by one or both of these cues within the cell. Kennedy et al. showed that calcium could bind to the HPT domain of Ypd1 from Cryptococcus neoformans (38). Therefore, it is possible that, while RscS senses a pABA signal, SypF’s cytoplasmic HPT domain binds to calcium, triggering the phosphorelay that ultimately results in activation of SypG and SypE to promote syp transcription and the posttranscriptional events necessary for biofilm formation (Fig. 1). Regardless of the exact scenario, signal transduction by RscS is necessary, as loss of its site of autophosphorylation, H412, disrupts the ability of RscS to promote biofilm formation (see Fig. S3).

Although a vitamin (pABA) seems like an unlikely signaling molecule, it can induce biofilm formation by Porphyromonas gingivalis in a multispecies biofilm in the oral cavity. Streptococcus gordonii-produced and -secreted pABA leads to increased expression and production of adhesins necessary for colonization and biofilm formation in P. gingivalis (39). Ultimately, pABA treatment results in increased colonization and virulence of P. gingivalis in a mouse model of infection (39).

The P. gingivalis/S. gordonii model is not the only example of a vitamin, acid, or benzene substituted ring acting as a signaling molecule in bacteria. For example, 4-hydroxycinnamic acid acts as a ligand for the PAS domain in Halorhodospira halophila and Rhodospirillum centenum (40). In bacteria that contain a PAS 4 domain, such as Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas mendocina, differently substituted aromatic hydrocarbons act as ligands, and in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, different dodecanoic acids are the ligands for the PAS 4 domain (41–46). Riboflavin, in Erythrobacter litoralis, has been shown to bind and activate PAS 9, resulting in signal transduction (47). Lastly, Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, which encodes a transmembrane SK with an N-terminal segment in the periplasm with sensory function, akin to the periplasmic loop of RscS, has been shown to bind to a diffusible signal factor (namely, a medium-chain fatty acid) similar to pABA (48). Throughout taxonomies, pABA-like compounds are biologically relevant signaling molecules. These examples support the possibility that pABA could be the ligand for the periplasmic loop of RscS. However, given that the RscS-bypass strain sypG* ΔsypE exhibits substantially more robust biofilms on TPC than are observed even for a strain that carries rscS on the multicopy plasmid pLMS33 (Fig. 5 and 6), it seems unlikely that pABA itself is the preferred ligand.

With respect to the ligands mentioned above, one of those signals was sufficient to elicit a response in a wide variety of bacteria. In V. fischeri, however, it seems instead that two signals are needed to induce ES114 biofilm formation. Many bacteria encode SKs with multiple sensing regions (49). In Caulobacter crescentus, the histidine kinase, CckA, has two PAS domains, each sensing different stimuli to effectively regulate its cell cycle (50). The E. coli SK EvgS has a periplasmic sensor domain and a PAS domain, similar to RscS. EvgS can respond to mildly acidic pH via its periplasmic sensor domain while also sensing oxidized ubiquinone through its PAS domain (51). Since RscS also has a periplasmic loop and PAS domain, it may sense both pABA and calcium—or their downstream consequences—through these domains. Additional work will be necessary to determine whether RscS can directly bind either of these molecules and if so, via which domain. It will also be of interest to determine whether calcium, in particular, signals through multiple regulators and/or exerts control at multiple levels, as is suggested by some of the current data.

In summary, our work here demonstrates a role for RscS under pABA/calcium conditions. While previous work had relied on plasmid-based overproduction of RscS protein, which could have led to artifacts and certainly by-passed the need for signaling, we identify here for the first time a substantive role for RscS using a deletion mutant and confirm the proposed position of this sensor kinase in the syp regulatory pathway. Moreover, using a heterologous system, we have discovered that the combination of pABA and calcium cues are inhibitory to V. fischeri strain KB2B1, which may indicate evolutionary divergence of these isolates; however, more work will be necessary to uncover the regulatory network in KB2B1. The data gathered here thus increase our understanding of the signal transduction mechanisms underlying biofilm induction by identifying RscS as critical for the response to the pABA and calcium cues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

V. fischeri strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. Plasmids and primers used in the study are shown in Tables 2 and 3. WT ES114 (52) was the primary parent strain used in this study; wild-type strain K2B1 was also used. E. coli strains were grown in LB (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract and 1% sodium chloride) (53). V. fischeri strains were cultured in either LBS medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 2% sodium chloride, and 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5]), tTBS (1% tryptone, 2% sodium chloride, and 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5]), or tTBS ± 10 mM calcium chloride and/or 9.7 mM pABA where noted (29, 54). For transformations, Tris-minimal medium (TMM) was used (53). Antibiotics were included as appropriate at the following final concentration: for V. fischeri, tetracycline (Tet), 2.5 μg/mL; kanamycin (Kan), 100 μg/mL; and chloramphenicol (Cm), 5 μg/mL and for E. coli, Cm, 12.5 μg/mL, and Kan, 50 μg/mL. For growth of E. coli thymidine auxotroph strain π3813 (55), which carries conjugal plasmid pEVS104 that was used to facilitate conjugations, thymidine (Thy) was added to a final concentration of 0.3 mM.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this studya

| Strain | Genotypeb | Construction | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES114 | Wild type | NA | 52 |

| KB2B1 | Wild type | NA | 62, 63 |

| KV1787 | ΔsypG | NA | 8 |

| KV3378 | ΔrscS | NA | 32 |

| KV5367 | ΔsypF | NA | 20 |

| KV6475 | ΔsypG attTn7::sypG-FLAG | NA | 61 |

| KV6527 | attTn7::sypG-D53E-FLAG | NA | 20 |

| KV6659 | ΔsypF attTn7::sypF-FLAG | NA | 20 |

| KV7226 | ΔsypF attTn7::sypF-HPT-FLAG | NA | 20 |

| KV7371 | IG::PsypA-lacZ | NA | 20 |

| KV7964 | ΔhahK:: FRT-Cm | NA | 19 |

| KV8025 | ΔhnoX:: FRT-Erm | NA | 23 |

| KV8079 | ΔsypQ::FRT-Cm IG::PsypA lacZ attTn7::Erm | NA | 19 |

| KV8232 | IG::Ermr-trunc Trimr | NA | 57 |

| KV8484 | ΔhnoX-hahK::FRT-Erm | NA | 23 |

| KV9191 | ΔsypG::FRT-Spec | TT ES114 with SOE product amplified with primers 1223 and 1221 (ES114), primers 2089 and 2090 (pKV521), and primers 2437 and 427 (ES114) | This study |

| KV9501 | ΔrscS::FRT-Spec | TT ES114 with SOE product amplified with primers 2918 and 2919 (ES114), primers 2089 and 2090 (pKV521), and primers 2920 and 2921 (ES114) | This study |

| KV9571 | ΔrscS-PP::FRT-Erm | TT ES114 with SOE product amplified with primers 2918 and 2938 (ES114), primers 2089 and 2090 (pKV494), and primers 2939 and 241 (ES114) | This study |

| KV9622 | IG::PrscS-lacZ | TT KV7371 with SOE product amplified with primers 2185 and 2090 (pKV502), primers 2965 and 2966 (ES114), and primers 2822 and 2876 (KV7371) | This study |

| KV9624 | IG::FRT-Erm | TT ES114 with SOE product amplified with primers 1500 and 2967 (ES114), primers 2089 and 2090 (pKV494), and primers 2968 and 663 (ES114) | This study |

| KV9653 | ΔrscS ΔsypQ::FRT-Cm IG::PsypA lacZ attTn7::Erm | TT KV8079 with gKV9501 | This study |

| KV9782 | rscS-FLAG-FRT-Erm | TT ES114 with SOE product amplified with primers 40 and 3138 (ES114), primers 2354 and 2090 (pKV494), and primers 3139 and 2921 (ES114) | This study |

| KV9942 | ΔrscS::FRT-Spec ΔsypF attTn7::sypF-HPT-FLAG | Derived from KV7226 using KV9501 | This study |

| KV9953 | ΔrscS::FRT ΔsypF attTn7::sypF-HPT-FLAG | Derived from KV9942 | This study |

| KV9968 | ΔhahK::FRT ΔsypF attTn7::sypF-HPT-FLAG | Derived from KV7226 using KV7964 | This study |

| KV10004 | IG::PnrdR-sypA-HA | TT KV8232 with SOE product amplified with primers 2290 and 2090 (pKV506), primers 3083 and 3297 (ES114), and primers 2331 and 1487 (pKV503) | This study |

| KV10019 | IG::PnrdR-sypF-HA | TT KV8232 with SOE product amplified with primers 2290 and 2090 (pKV506), primers 2264 and 2348 (ES114), and primers 2331 and 1487 (pKV503) | This study |

| KV10020 | ΔsypE::FRT-Erm | TT ES114 with SOE product amplified with primers 460 and 2263 (ES114), primers 2089 and 2090 (pKV494), primers 2264 and 425 (ES114) | This study |

| KV10083 | IG::rscS-3′ end-HA | TT KV8232 with SOE products amplified with primers 2331 and 1487 (gKV10004) and primers 2290 and 3292 (gKV9571) | This study |

| KV10101 | IG::PrscS rscS-HA | TT KV10083 with SOE products amplified with primers 2290 and 85 (gKV9624) and primers 2185 and 2090 (pKV502) | This study |

| KV10130 | ΔrscS::FRT | Derived from KV9501 | This study |

| KV10154 | IG::rscS-3′ end-FLAG | TT KV8232 with SOE products amplified with primers 2290 and 3138 (gKV10083) and primers 2354 and 1487 (gKV10083) | This study |

| KV10162 | IG::PrscS-rscS-FLAG | TT KV10154 with SOE product amplified with primers 2185 and 85 (gKV10101) | This study |

| KV10163 | ΔsypE::FRT | Derived from KV10020 | This study |

| KV10165 | ΔrscS IG::PrscS-rscS-FLAG-FRT-erm | TT KV3378 with gKV10162 | This study |

| KV10166 | ΔrscS::FRT IG::PrscS-rscS-FLAG | TT KV10130 with gKV10162 | This study |

| KV10181 | ΔrscS::FRT ΔsypE::FRT-Erm | NT10130 with gKV10020 | This study |

| KV10185 | ΔhnoX::FRT-Spec | TT ES114 with SOE product amplified with primers 2155 and 2156 (ES114), primers 2089 and 2090 (pKV521), and primers 2157 and 2158 (ES114) | This study |

| KV10186 | ΔsypF::FRT-Spec | TT ES114 with SOE product amplified with primers 1194 and 1160 (ES114), primers 2089 and 2090 (pKV521), and primers 2297 and 271 (ES114) | This study |

| KV10226 | ΔhnoX::FRT-Spec ΔsypF attTn7::sypF-HPT-FLAG | Derived from KV7226 using KV10185 | This study |

| KV10255 | IG::PnrdR-sypF-FLAG | TT KV8232 with SOE product amplified with primers 2290 and 4067 (gKV10019) and primers 2354 and 1487 (pKV503) | This study |

| KV10255 | IG::PnrdR-sypF-FLAG | TT KV8232 with SOE product amplified with primers 2290 and 4067 (gKV10019) and primers 2354 and 1487 (pKV503) | This study |

| KV10298 | IG::PrscS-rscS/sypF chimera2 | TT KV8232 with SOE product amplified with primers 2290 and 3350 (KV10162) and primers 3351 and 1487 (KV10255) | This study |

| KV10299 | IG::PrscS-rscS-Δperiplasmic loop | TT KV8232 with SOE product amplified with primers 2290 and 4111 (KV10165) and primers 4112 and 1487 (KV10165) | This study |

| KV10301 | ΔsypF::FRT IG::PrscS-rscS/sypF chimera | TT KV5367 with gKV10298 | This study |

| KV10302 | ΔrscS::FRT IG::PrscS-rscS/sypF chimera | TT 10130 with gKV10298 | This study |

| KV10303 | ΔrscS::FRT IG::PrscS-rscS-Δperiplasmic loop | TT KV10130 with gKV10299 | This study |

| KV10304 | ΔhahK ΔsypQ::FRT-Cm IG::PsypA lacZ attTn7::Erm | TT KV8079 with gKV7964 | This study |

| KV10305 | ΔsypF::FRT-Spec ΔrscS::FRT | TT10130 with gKV10186 | This study |

| KV10307 | ΔsypG ΔsypQ::FRT-Cm IG::PsypA lacZ attTn7::Erm | TT KV8079 with PCR-amplified DNA from KV9191 | This study |

| KV10312 | ΔsypF::FRT-Spec ΔrscS::FRT IG::PrscS-rscS/sypF chimera2 | TT 10305 with gKV10298 | This study |

| KV10317 | ΔsypF ΔsypQ::FRT-Cm IG::PsypA lacZ attTn7::Erm | TT KV8079 with PCR-amplified DNA from KV10186 | This study |

| KV10351 | ΔsypF::FRT ΔrscS::FRT IG::PrscS-rscS/sypF chimera | Derived from KV10312 | This study |

| KV10355 | ΔsypF::FRT IG::PrscS-rscS/sypF chimera | Derived from KV10301 | This study |

| KV10388 | KB2B1 ΔrscS::FRT-Spec IG::PrscS-rscS-FLAG (ES114) | TT KV10409 with gKV9501 | This study |

| KV10389 | KB2B1 IG::PnrdR-sypF-FLAG (ES114) | TT KB2B1with gKV10255 | This study |

| KV10390 | PrscS-rscS/sypF chimera (rscS native site) IG (rscS-glpK)::FRT-Erm | TT ES114 with SOE product amplified with primers 40 and 3141 (gKV10302) and primers 2354 and 2921 (gKV9782) | This study |

| KV10391 | attTn7::sypG-D53E-FLAG ΔrscS::FRT-Spec | TT KV6527 with gKV9501 | This study |

| KV10397 | ΔsypF::FRT IG::PrscS-rscS/sypF chimera + PrscS-rscS/sypF chimera (rscS native site) IG (rscS-glpK)::FRT-Erm | TT KV10351 with gKV10390 | This study |

| KV10409 | KB2B1 IG::PrscS-rscS-FLAG (ES114) | TT KB2B1 with gKV10162 | This study |

| KV10439 | ΔrscS::FRT IG::PrscS-rscS-H412Q-FLAG | TT KV10130 with SOE product amplified with primers 2290 and 4239 (gKV10165) and primers 4238 and 1487 (gKV10165) | This study |

| KV10440 | ΔrscS::FRT ΔsypE::FRT | Derived from KV10181 | This study |

| KV10442 | attTn7::sypG-D53E-FLAG ΔrscS::FRT ΔsypE::FRT | TT KV10440 with gKV6527 | This study |

| KV10444 | attTn7::sypG-D53E-FLAG ΔsypE::FRT | TT KV10163 with gKV6527 | This study |

HA, HA epitope tagged; flag, FLAG epitope tagged; IG, intergenic between yeiR and glmS (adjacent to the Tn7 site) unless otherwise noted; FRT, the antibiotic cassette was resolved using Flp recombinase, leaving a single FRT sequence; TT, TfoX-mediated transformation of a tfoX-overexpressing version of the indicated strain with the indicated genomic DNA (gDNA) or with a PCR-SOE product generated using the indicated primers and templates.

The rscS/sypF chimera substituted the HPT domain of rscS with that of sypF. It was positioned either at the nonnative site between yeiR and glmS (“IG”) under the control of PrscS or at the native rscS location in the ΔsypF ΔrscS background (with the chimera repairing the rscS deletion).

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pCLD54 | Wild-type sypF on pKV69 | 22 |

| pEVS104 | Conjugal helper plasmid (Kanr) | 64 |

| pJFB9 | pLosTfox+Kanr | 58 |

| pJJC4 | tfoX++Cmr | 59 |

| pKV69 | Vector control | 24 |

| pKV494 | pJET+FRT-Ermr | 57 |

| pKV496 | flp++Kanr | 57 |

| pKV502 | pJET+yeiR-FRT-Ermr | 57 |

| pKV503 | pJET+glmS | 57 |

| pKV506 | pJET+yeiR-FRT-Ermr-PnrdR | 57 |

| pKV521 | pJET+FRT-Specr | 57 |

| pLMS33 | Wild type rscS on pKV69 | 24 |

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|

| 27 | AGGTGATGAAGCCGCTCGA |

| 40 | GTCAACGACTAGGACATAAG |

| 85 | GATAGATAAGTATTAGTGATAGG |

| 241 | TTTTTCTGCAGGTAGATTTAGCTCTATTTGAAAC |

| 271 | CTCGGCGCATACTTCTTTAC |

| 425 | AGGGGTTCGTATTTCGTGACTC |

| 427 | TAATACCGTTGTTTTGCT TGG |

| 460 | GCCTTGATAGGAGCATTATAATG |

| 663 | ACGACGATTATACAAAAATGAAGC |

| 1160 | taggcggccgcacttagtatgGATGCACTGAATAATTGAGATACC |

| 1194 | TTATGTGCGAGGCCTAATGC |

| 1221 | taggcggccgcacttagtatgGTCTTCGACTAATAATACTTTCTG |

| 1223 | GAATGTCTTGCTAAGTACCTG |

| 1487 | GGTCGTGGGGAGTTTTATCC |

| 1500 | CCACCATCACGATTACGAAC |

| 2089 | CCATACTTAGTGCGGCCGCCTA |

| 2090 | CCATGGCCTTCTAGGCCTATCC |

| 2155 | ATCTCTTGAGCACTTGTTTGAG |

| 2156 | taggcggccgcactaagtatggAATAATCCCTTTCATAAACACTCC |

| 2157 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggAAATCATAAACGATTAAGGCGGG |

| 2158 | TCGCGCCACATTGTATTTGG |

| 2185 | CTTGATTTATACAGCGAAGGAG |

| 2263 | taggcggccgcactaagtatggATTCATGATTACACCACTGTTG |

| 2264 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggCCCAATGACGATGCATTATTGC |

| 2264 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggCCCAATGACGATGCATTATTGC |

| 2289 | AATTGCTGTTGAAGCATCTCTG |

| 2290 | AAGAAACCGATACCGTTTACG |

| 2291 | CAGGTAAAGGGCATTTAACG |

| 2297 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggAAACAAGGTTTCTCAAAATAAAAG |

| 2331 | tatccatatgatgttccagattatgcataaCCATACTTAGTGCGGCCGCCTA |

| 2348 | taggcggccgcactaagtatggaTTATGCATAATCTGGAACATCATATGGATAttttgagaaaccttgtttatttc |

| 2354 | gattataaagatgatgatgataaataaCCATACTTAGTGCGGCCGCCTA |

| 2437 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggGAAGCCTATGAAGAATCGGAATGATG |

| 2822 | catggtcatagctgtttcctGCTTATCTAATCCAAATAATTTAAC |

| 2918 | TGCTTCACGAATTACTCCCC |

| 2919 | taggcggccgcactaagtatggAATGATTGTGATAAGGCTATAACG |

| 2920 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggAAGTATGAAACACAATAAACTTCG |

| 2921 | GTACGATTGTAGGCTTAACTCG |

| 2938 | taggcggccgcactaagtatggATATTGTTTTACAGGATGGTTCCTCG |

| 2965 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggCGAATTACTCCCCTAATTACGAAC |

| 2966 | catggtcatagctgtttcctTGCATTAGCTCCTATAAAATAGTC |

| 2967 | taggcggccgcactaagtatggATTAAGCGTATTCAAGAACATTCG |

| 2968 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggCGAGCATTTTCTACAACATGTG |

| 3083 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggAGCTTCTTCCTTATAGTTATGATG |

| 3138 | ttatttatcatcatcatctttataatcTTGTGTTTCATACTTCTCTAATAATC |

| 3139 | ggataggcctagaaggccatggACTTCGTCATAAAAAAAGGAGCAC |

| 3141 | taggcggccgcactaagtatgga |

| 3292 | ttatgcataatctggaacatcatatggataTTGTGTTTCATACTTCTCTAATAATC |

| 3297 | ttatgcataatctggaacatcatatggataATGCGTTGTTTTATTAACAGGAATTG |

| 3350 | aataatagctcattatccatTGCATCATCTGAAAGTTTATATTTAG |

| 3351 | taaactttcagatgatgcaATGGATAATGAGCTATTATTAGTAG |

| 4067 | ttatttatcatcatcatctttataatcTTTTGAGAAACCTTGTTTATTTC |

| 4111 | gagtttttatcgtttcagattgggtATATTGTTTTACAGGATGGTTCCTCG |

| 4112 | cgaggaaccatcctgtaaaacaatatACCCAATCTGAAACGATAAAAACTC |

| 4238 | CAACTATGAGCCAgGAGTTAAGGACACCTCTTAATG |

| 4239 | GTCCTTAACTCcTGGCTCATAGTTGCTAAAAACG |

Lowercase letters denote nonnative or tail sequences.

Molecular techniques and strain construction.

Mutations in ES114 were generated through TfoX-mediated transformation (54). Briefly, ~500-bp segments upstream and downstream of genes of interest were PCR amplified using high-fidelity KOD polymerase (Novagen, EMD Millipore), and PCR slicing by overlap extension (SOE [56]) was used to fuse segments to an antibiotic cassette as previously described (57). The fused product was amplified and transformed into the recipient V. fischeri strain (ES114 or its derivative) carrying a TfoX-overproducing plasmid (plostfoX-Kan [58] or pJJC4 [59]) and recombinant cells were selected for using media containing the appropriate antibiotic. Allelic replacement was confirmed via PCR with outside primers using Promega Taq polymerase. After generation of the initial deletion, genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from a given recombinant strain using the Quick-DNA Miniprep plus kit (Zymo Research) and was used to introduce the mutation into other desired strain backgrounds. Insertions were introduced at the intergenic (IG) region between yeiR and glmS as described previously (57). These insertions were made using PCR amplification and the SOE method described above. Genes of interest were fused to an upstream Erm cassette for selection, driven by the native promoter or a constitutive pndrR promoter. In cases where Ermr, or another antibiotic cassette, needed to be removed, Flp recombinase was used, which acts on the Flp recombination target (FRT) sequences to delete the intervening sequences as previously shown (60). Bacterial conjugation was used to transfer the plasmids of interest into the strains noted as described previously (54). Briefly, the recipient V. fischeri strains were inoculated into 5 mL of LBS and grown overnight at 28°C. Donor E. coli strains (carrying the plasmid of interest) were inoculated into LB with the appropriate antibiotic and the helper E. coli strain was inoculated into LB with the appropriate supplements (Thy and Kan) and grown overnight at 37°C. The strains were then subcultured, in the same growth conditions, and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ~0.2. Then, the V. fischeri recipient, and the E. coli strains were added to microcentrifuge tubes and concentrated. Separately, as a negative control, each V. fischeri recipient culture was also concentrated alone by centrifugation as described above. Supernatants were decanted and the remaining liquid was used to resuspend the pellets at the bottom of the tube. An aliquot (~15 μL) was then spotted onto LBS without antibiotics and placed into the 28°C incubator for a minimum of 3 h or overnight. The colonies were then streaked onto media with the appropriate antibiotics and grown overnight at 28°C. The resultant colonies were then restreaked onto the appropriate media, and the individual colonies were grown in liquid cultures and saved.

Colony biofilm assays.

One day prior to experimentation, tTBS plates (+Ca, +pABA, and +Ca+pABA) were made by pipetting 25 mL of the appropriate medium into petri dishes and left to dry overnight. Cultures were inoculated from frozen and grown overnight in 5 mL of tTBS with shaking at 28°C. The strains were then subcultured (150 μL into 5 mL of tTBS) and grown with shaking at 28°C for 1 to 2 h. Next, the cultures were normalized to an OD600 of 0.2 in tTBS. The normalized cultures were then spotted onto the tTBS plates with or without additives at 10 μL per spot and left to dry completely before inverting and incubating at 24°C. After 72 and/or 96 h, the spots were assessed using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-C microscope at a magnification of 6.5× and photographed before and after being disrupted with a toothpick; this “toothpick” assay permits an assessment of the relative stickiness of the colony biofilm (61).

Biofilm quantification.

Images of disrupted colony biofilms were deidentified and numerically coded, then assessed for cohesion by a blinded coauthor. Biofilm cohesion was given a number from 1 to 4, with 1 representing no stickiness (null phenotype), 2 representing partial stickiness, 3 representing full cohesion/stickiness (entire colony drags with toothpick), and 4 representing the strongest cohesion and adhesion (colony is adherent to agar).

β-Galactosidase assays.

Reporter strains were streaked onto tTBS plates and grown at 24°C overnight (~16 h). A single colony was then picked and used to inoculate 5 mL of tTBS in 18 × 150-mm tubes. Three different colonies were used for three different replicates, and these tubes were grown at 24°C with shaking overnight. In the morning, all three replicates of the reporter strain were subcultured in 125 mL baffled flasks with 20 mL of the 4 different media types (tTBS, tTBS+calcium, tTBS+pABA, and tTBS+calcium+pABA). Strains were grown for 22 h. The final concentrations of calcium and pABA were 10 and 9.7 mM, respectively. After the indicated growth period, an aliquot (6 mL) of each culture was concentrated by centrifugation and a β-galactosidase assay (Miller assay) was performed as previously described (19). The OD420 and OD550 were then measured using a 96-well plate reader and Miller units were calculated as previously described (19). The data show standard errors of the mean from three independent experiments performed with three biological replicates in each experiment.

Statistics.

All error bars shown represent standard deviations. Prism 9 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) was used to generate graphs and perform statistical analyses. One-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze data for each graph, as noted. For ANOVA, P values were adjusted using either Tukey’s multiple-comparison test or Šídák’s multiple-comparison test, where the independent variable was on the x axis, and the dependent variable was on the y axis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steven Eichinger for help with the construction of the PrscS-lacZ reporter, Prerana Shrestha and Gio Duca for help with the construction of the rscS complementation cassette, Xijin Lin for help with construction of ΔrscS+rscS-H412Q, and members of the Visick and Stabb labs for valuable feedback.

We declare there are no conflicts of interest.

C.N.D. and K.L.V. conceived the work. C.N.D., B.L.F., and K.L.V. collected, analyzed, and interpreted data. C.N.D., B.L.F., and K.L.V. drafted the article and approved the final version prior to manuscript submission.

This study was supported by funding from NIGMS grant R35 GM130355 awarded to K.L.V.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Karen L. Visick, Email: kvisick@luc.edu.

George O’Toole, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu C, Sun D, Zhu J, Liu W. 2018. Two-component signal transduction systems: a major strategy for connecting input stimuli to biofilm formation. Front Microbiol 9:3279. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szurmant H, White RA, Hoch JA. 2007. Sensor complexes regulating two-component signal transduction. Curr Opin Struct Biol 17:706–715. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zschiedrich CP, Keidel V, Szurmant H. 2016. Molecular mechanisms of two-component signal transduction. J Mol Biol 428:3752–3775. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mascher T, Helmann JD, Unden G. 2006. Stimulus perception in bacterial signal-transducing histidine kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70:910–938. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhate MP, Molnar KS, Goulian M, DeGrado WF. 2015. Signal transduction in histidine kinases: insights from new structures. Structure 23:981–994. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buschiazzo A, Trajtenberg F. 2019. Two-component sensing and regulation: how do histidine kinases talk with response regulators at the molecular level? Annu Rev Microbiol 73:507–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091018-054627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao R, Stock AM. 2009. Biological insights from structures of two-component proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol 63:133–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussa EA, O’Shea TM, Darnell CL, Ruby EG, Visick KL. 2007. Two-component response regulators of Vibrio fischeri: identification, mutagenesis, and characterization. J Bacteriol 189:5825–5838. doi: 10.1128/JB.00242-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyholm SV, McFall-Ngai MJ. 2021. A lasting symbiosis: how the Hawaiian bobtail squid finds and keeps its bioluminescent bacterial partner. Nat Rev Microbiol 19:666–679. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00567-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Visick KL, Stabb EV, Ruby EG. 2021. A lasting symbiosis: how Vibrio fischeri finds a squid partner and persists within its natural host. Nat Rev Microbiol 19:654–665. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00557-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibata S, Yip ES, Quirke KP, Ondrey JM, Visick KL. 2012. Roles of the structural symbiosis polysaccharide (syp) genes in host colonization, biofilm formation, and polysaccharide biosynthesis in Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 194:6736–6747. doi: 10.1128/JB.00707-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yip ES, Geszvain K, DeLoney-Marino CR, Visick KL. 2006. The symbiosis regulator rscS controls the syp gene locus, biofilm formation, and symbiotic aggregation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 62:1586–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yip ES, Grublesky BT, Hussa EA, Visick KL. 2005. A novel, conserved cluster of genes promotes symbiotic colonization and sigma-dependent biofilm formation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 57:1485–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris AR, Darnell CL, Visick KL. 2011. Inactivation of a novel response regulator is necessary for biofilm formation and host colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 82:114–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks JF, II, Mandel MJ. 2016. The histidine kinase BinK is a negative regulator of biofilm formation and squid colonization. J Bacteriol 198:2596–2607. doi: 10.1128/JB.00037-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussa EA, Darnell CL, Visick KL. 2008. RscS functions upstream of SypG to control the syp locus and biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 190:4576–4583. doi: 10.1128/JB.00130-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandel MJ, Wollenberg MS, Stabb EV, Visick KL, Ruby EG. 2009. A single regulatory gene is sufficient to alter bacterial host range. Nature 458:215–218. doi: 10.1038/nature07660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray VA, Eddy JL, Hussa EA, Misale M, Visick KL. 2013. The syp enhancer sequence plays a key role in transcriptional activation by the σ54-dependent response regulator SypG and in biofilm formation and host colonization by Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 195:5402–5412. doi: 10.1128/JB.00689-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tischler AH, Lie L, Thompson CM, Visick KL. 2018. Discovery of calcium as a biofilm-promoting signal for Vibrio fischeri reveals new phenotypes and underlying regulatory complexity. J Bacteriol 200:e00016-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00016-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norsworthy AN, Visick KL. 2015. Signaling between two interacting sensor kinases promotes biofilms and colonization by a bacterial symbiont. Mol Microbiol 96:233–248. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson CM, Marsden AE, Tischler AH, Koo J, Visick KL. 2018. Vibrio fischeri biofilm formation prevented by a trio of regulators. Appl Environ Microbiol 84. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01257-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darnell CL, Hussa EA, Visick KL. 2008. The putative hybrid sensor kinase SypF coordinates biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri by acting upstream of two response regulators, SypG and VpsR. J Bacteriol 190:4941–4950. doi: 10.1128/JB.00197-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson CM, Tischler AH, Tarnowski DA, Mandel MJ, Visick KL. 2019. Nitric oxide inhibits biofilm formation by Vibrio fischeri via the nitric oxide sensor HnoX. Mol Microbiol 111:187–203. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visick KL, Skoufos LM. 2001. Two-component sensor required for normal symbiotic colonization of Euprymna scolopes by Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 183:835–842. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.835-842.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris AR, Visick KL. 2013. Inhibition of SypG-induced biofilms and host colonization by the negative regulator SypE in Vibrio fischeri. PLoS One 8:e60076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris AR, Visick KL. 2013. The response regulator SypE controls biofilm formation and colonization through phosphorylation of the syp-encoded regulator SypA in Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 87:509–525. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pankey SM, Foxall RL, Ster IM, Perry LA, Schuster BM, Donner RA, Coyle M, Cooper VS, Whistler CA. 2017. Host-selected mutations converging on a global regulator drive an adaptive leap towards symbiosis in bacteria. Elife 6:e24414. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludvik DA, Bultman KM, Mandel MJ. 2021. Hybrid histidine kinase BinK represses Vibrio fischeri biofilm signaling at multiple developmental stages. J Bacteriol 203:e0015521. doi: 10.1128/JB.00155-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dial CN, Speare L, Sharpe GC, Gifford SM, Septer AN, Visick KL. 2021. para-Aminobenzoic acid, calcium, and c-di-GMP induce formation of cohesive, Syp-polysaccharide-dependent biofilms in Vibrio fischeri. mBio 12:e02034-21. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02034-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Dufour YS, Carlson HK, Donohue TJ, Marletta MA, Ruby EG. 2010. H-NOX-mediated nitric oxide sensing modulates symbiotic colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:8375–8380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003571107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsden AE, Grudzinski K, Ondrey JM, DeLoney-Marino CR, Visick KL. 2017. Impact of salt and nutrient content on biofilm formation by Vibrio fischeri. PLoS One 12:e0169521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geszvain K, Visick KL. 2008. The hybrid sensor kinase RscS integrates positive and negative signals to modulate biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 190:4437–4446. doi: 10.1128/JB.00055-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bongrand C, Koch EJ, Moriano-Gutierrez S, Cordero OX, McFall-Ngai M, Polz MF, Ruby EG. 2016. A genomic comparison of 13 symbiotic Vibrio fischeri isolates from the perspective of their host source and colonization behavior. ISME J 10:2907–2917. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rotman ER, Bultman KM, Brooks JF, Gyllborg MC, Burgos HL, Wollenberg MS, Mandel MJ. 2019. Natural strain variation reveals diverse biofilm regulation in squid-colonizing Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 201:e00033-19. doi: 10.1128/JB.00033-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Speare L, Smith S, Salvato F, Kleiner M, Septer AN. 2020. Environmental viscosity modulates interbacterial killing during habitat transition. mBio 11:e03060-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03060-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. 2013. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tischler AH, Vanek ME, Peterson N, Visick KL. 2021. Calcium-responsive diguanylate cyclase CasA drives cellulose-dependent biofilm formation and inhibits motility in Vibrio fischeri. mBio 12:e02573-21. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02573-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kennedy EN, Menon SK, West AH. 2016. Extended N-terminal region of the essential phosphorelay signaling protein Ypd1 from Cryptococcus neoformans contributes to structural stability, phosphostability, and binding of calcium ions. FEMS Yeast Res 16:fow068. doi: 10.1093/femsyr/fow068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuboniwa M, Houser JR, Hendrickson EL, Wang Q, Alghamdi SA, Sakanaka A, Miller DP, Hutcherson JA, Wang T, Beck DAC, Whiteley M, Amano A, Wang H, Marcotte EM, Hackett M, Lamont RJ. 2017. Metabolic crosstalk regulates Porphyromonas gingivalis colonization and virulence during oral polymicrobial infection. Nat Microbiol 2:1493–1499. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0021-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]