Abstract

We have previously observed that while native Treponema pallidum rare outer membrane protein 1 (Tromp1) is hydrophobic and has porin activity, recombinant forms of Tromp1 do not possess these properties. In this study we show that these properties are determined by conformation and can be replicated by proper renaturation of recombinant Tromp1. Native Tromp1, but not the 47-kDa lipoprotein, extracted from whole organisms by using Triton X-114, was found to lose hydrophobicity after treatment in 8 M urea, indicating that Tromp1’s hydrophobicity is conformation dependent. Native Tromp1 was purified from 0.1% Triton X-100 extracts of whole organisms by fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) and shown to have porin activity in planar lipid bilayers. Cross-linking studies of purified native Tromp1 with an 11 Å cross-linking agent showed oligomeric forms consistent with dimers and trimers. For renaturation studies of recombinant Tromp1 (rTromp1), a 31,109-Da signal-less construct was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by FPLC. FPLC-purified rTromp1 was denatured in 8 M urea and then renatured in the presence of 0.5% Zwittergent 3,14 during dialysis to remove the urea. Renatured rTromp1 was passed through a Sephacryl S-300 gel exclusion column previously calibrated with known molecular weight standards. While all nonrenatured rTromp1 eluted from the column at approximately the position of the carbonic anhydrase protein standard (29 kDa), all renatured rTromp1 eluted at the position of the phosphorylase b protein standard (97 kDa), suggesting a trimeric conformation. Trimerization was confirmed by using an 11 Å cross-linking agent which showed both dimers and trimers similar to that of native Tromp1. Triton X-114 phase separations showed that all of renatured rTromp1, but none of nonrenatured rTromp1, phase separated exclusively into the hydrophobic detergent phase, similar to native Tromp1. Circular dichroism of nonrenatured and renatured rTromp1 showed a marked loss in alpha-helical secondary structure of renatured rTromp1 compared to the nonrenatured form. Finally, renatured rTromp1, but not the nonrenatured form, showed porin activity in planar liquid bilayers. These results demonstrate that proper folding of rTromp1 results in a trimeric, hydrophobic, and porin-active conformation similar to that of the native protein.

The syphilis spirochete, Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum, possesses a unique outer membrane containing 100-fold-less membrane-spanning outer membrane protein than typical gram-negative bacterial outer membranes (30, 38). The identification of these T. pallidum rare outer membrane proteins, collectively termed TROMPs (9), has been a major focus of syphilis research because they are surface exposed proteins of likely significance to both pathogenesis and immunity.

We previously reported a method to isolate the T. pallidum outer membrane (8) that resulted in the identification of two proteins markedly enriched in these preparations. One of these proteins, termed Tromp1, was found to have properties consistent with an outer membrane origin, including amphiphilicity and porin activity measured in planar lipid bilayers (6). We also found that recombinant Tromp1, expressed and exported in Escherichia coli, in part localized to the E. coli outer membrane, where porin activity similar to that of native Tromp1 was again demonstrated (7).

While our past findings have been consistent with Tromp1 being an outer membrane protein, two recent reports have challenged this conclusion. Hardham et al. (18) have found that the tromp1 gene, referred to as troA in their studies, is part of an operon with similarities to ABC transporter systems, and that TroA has 26 to 28% sequence identity to the periplasmic binding protein component of these operons. This observation has resulted in the alternative view that Tromp1 is a periplasmic binding protein (18). Akins et al. (1) reported that native Tromp1 has an uncleaved signal peptide which anchors Tromp1 to the cytoplasmic membrane and accounts for its demonstrated hydrophobicity. These investigators also reported that recombinant Tromp1, made without a signal peptide, lacked hydrophobic properties and porin activity, findings used to support their conclusion that Tromp1 is an inner membrane anchored periplasmic binding protein. Thus, whether Tromp1 is a bona fide outer membrane protein or periplasmic binding protein has been a topic of current debate.

To address the controversy surrounding Tromp1, we have recently engaged in a structural analysis of the native protein. We have conclusively demonstrated, by use of mass spectrometry, that native Tromp1 has a cleaved signal peptide (10) in contrast to the report by Akins et al. (1). Implicit from this finding is that the observed hydrophobicity of native Tromp1 is not due to an uncleaved signal peptide as reported but is rather a property of its conformation.

In the present study, we show that denaturation of native Tromp1 eliminates its hydrophobicity, a finding consistent with the conformation of Tromp1 being responsible for this property. In addition, we show that purified native Tromp1, which has porin activity, exists in a trimeric conformation. These properties of native Tromp1 are successfully recreated by using a signal-peptide-lacking form of recombinant Tromp1 which was renatured into a trimeric, hydrophobic, and porin-active conformation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of T. pallidum.

T. pallidum subsp. pallidum, Nichols strain, was maintained by testicular passage in New Zealand White rabbits as previously described (24). T. pallidum used for all experiments was extracted from infected rabbit testicles in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS), centrifuged two times at 400 × g to pellet gross tissue debris, and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g to pellet the organisms. The treponemal pellet was washed once in PBS, recentrifuged to again pellet the organisms, and then resuspended in PBS to yield a final concentration of 1010 organisms/ml.

FPLC purification of native Tromp1.

A total of 2 × 1011 T. pallidum, extracted from 20 infected rabbits, was incubated in 40 ml of ice-cold 0.1% Triton X-100 (TX-100; Calbiochem) for 2 h in order to solubilize the outer membrane and completely release Tromp1 (approximately 5 μg) (6). The suspension was then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 40 min at 4°C in order to pellet the protoplasmic cylinders. The supernatant, containing all of the Tromp1 and other detergent-extracted proteins, was subjected to anion-exchange chromatography by using a fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) system (Pharmacia Co., Alameda, Calif.). The anion-exchange buffer consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) with 0.2% hydrogenated Triton X-100, and the proteins were eluted by using a salt gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl. Fractions enriched with Tromp1, determined by immunoblot analysis with monospecific anti-recombinant Tromp1 (rTromp1) serum generated as previously described (7), were collected, pooled, and rechromatographed under these conditions. The second round of Tromp1-enriched fractions was then subjected to chromatofocusing chromatography by using a MonoP column (Pharmacia). The starting buffer contained of 25 mM bis-Tris (pH 6.7) with 0.1% hydrogenated Triton X-100, and the elution buffer contained 10% Polybuffer, pH 5.0 (Pharmacia), containing 0.1% hydrogenated Triton X-100. After chromatofocusing, Tromp1 purity was demonstrated by silver stain (see Fig. 2) and immunoblot analysis by using syphilitic infection-derived immune rabbit serum (data not shown). The total amount of recovered native Tromp1 from 2 × 1011 organisms was estimated by gel analysis to be 500 ng (10% recovery). A total of 10 isolations, each using 2 × 1011 organisms (a total of 200 infected rabbits), were performed which resulted in the isolation of 5 μg of purified native Tromp1.

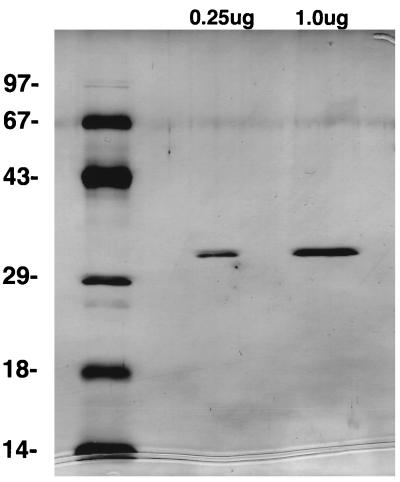

FIG. 2.

Purity of FPLC-isolated native Tromp1. Samples containing 0.25 and 1.0 μg of FPLC-purified native Tromp1 were separated by SDS-PAGE and silver stained. Numbers on the left indicate the molecular weights (in thousands) of the standards separated.

Expression of a signal-less form of rTromp1.

A signal-less form of recombinant Tromp1 (rTromp1), having a calculated molecular mass of 31,109 Da, was generated as follows. An N-terminal primer of 5′-CGCCATATGAGCAAGGATGCCGCAGCAGAC-3′ (underlined region indicates the tromp1 gene sequence) corresponding to signal peptide cleavage after alanine-phenylalanine-glycine (AFG) was generated containing an NdeI restriction endonuclease site at the 5′ end (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). This construct results in a single methonine residue placed ahead of the site of signal peptide cleavage for the purpose of translation. A C-terminal primer consisting of 5′-CGCGGATCCCTAGCGAGCCAACGCAGCAA-3′ and corresponding to the end of the tromp1 gene was generated containing a BamHI restriction endonuclease site at the 5′ end. PCR was performed by using these primers as described previously (7). The tromp1 PCR product was ligated into pET17b (Novagen, Inc.), previously digested with NdeI and BamHI. The resulting construct was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysE) (Novagen, Inc.) by using cells made competent by CaCl2. Expression and FPLC purification of rTromp1 was performed as described previously (7).

Renaturation of rTromp1.

The protocol described by Qi et al. (27) for the renaturation of recombinant neisserial porin proteins was used for the renaturation of signal-less rTromp1 as follows. Solid urea was added to 1 ml of FPLC-purified rTromp1 (2 mg/ml) in 50 mM Tris–100 mM NaCl–0.05% Zwittergent-3,14 (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp., La Jolla, Calif.) at pH 8.0 to give a final concentration of 8 M urea. The suspension was then boiled for 15 min in order to completely denature rTromp1. After denaturation, the suspension was added to an equal volume of 1% Zwittergent-3,14 (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp.) and then dialyzed overnight at 4°C against a buffer containing 100 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.02% sodium azide at pH 8.0 in order to remove the urea and renature rTromp1. The renatured rTromp1 suspension was then applied to a Sephacryl S-300 column (1.5 by 75 cm; Pharmacia Biotech, Inc.), which was equilibrated in the same buffer used for dialysis and which had been previously calibrated with known molecular mass standards (gel filtration molecular weight markers; Sigma Chemical Co.). In some experiments, FPLC-purified rTromp1 was added directly to the column without prior denaturation and renaturation treatment. Fractions containing rTromp1 were identified by spectrophotometry (optical density at 280 nm) and by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblot analysis. Renatured rTromp1 samples were stored at −70°C.

Cross-linking experiments.

Renatured and nonrenatured rTromp1 and native Tromp1 were dialyzed against PBS. Twenty-five microliters of each of the Tromp1 preparations containing 1 μg of protein was mixed with an equal volume of bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate (BS3) (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) at various concentrations. BS3 is a homobifunctional N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (NHS-ester) which can form noncleavable covalent bonds between N-terminal α-amine groups and/or side chains of amino acids of peptides and proteins that are separated by less than 11 Å; ɛ-amine of lysine is the principle side chain target for this NHS-ester (25). After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, 1 M Tris (pH 7.5) was added to give a final concentration of 40 mM in the reaction mixture, which was then incubated for an additional 15 min at room temperature. The mixtures were then dried by using a speed vacuum, and the dried contents were resuspended in sample buffer containing 8 M urea. Samples were boiled for 10 min prior to SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) immunoblotting membranes. Immunoblotting for the detection of Tromp1 was conducted as described below.

TX-114 treatments.

Triton X-114 (TX-114; Calbiochem) detergent extraction of T. pallidum and separation of the extracted material into detergent (hydrophobic) and aqueous (hydrophilic) phases was performed as follows. Ten microliters of treponemal suspension (108 T. pallidum) was added to 500 μl of ice-cold 0.1% TX-114 in PBS. The suspension was incubated at 4°C for 2 h to selectively solubilize the outer membrane, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g to pellet the treponemal protoplasmic cylinders. This procedure, using 2% TX-114, has been shown not to solubilize the inner membrane of T. pallidum (12, 29). The protoplasmic cylinders were washed once in PBS and then recentrifuged prior to resuspension in SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 2% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 15% glycerol in 100 mM Tris (pH 6.8). To the extracted supernatant, 100 μl of 10% TX-114 was added (final concentration of 2.1% detergent) prior to warming at 37°C for 5 min to induce cloud formation. The suspension was then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature in order to separate aqueous (top) and detergent (bottom) phases. Both aqueous and detergent phases were recovered and reextracted three times as described above with cold 2% Triton X-114 and PBS, respectively. In some experiments, urea treatment of T. pallidum was performed prior to TX-114 extraction and phase separation as follows. Ten microliters of treponemal suspension (108 T. pallidum) was combined with 70 μl of 8 M urea (final concentration of 7 M urea), followed by heating at 90°C for 10 min. The suspension was then cooled and added to 500 μl of 0.1% TX-114. Extraction and phase separation was performed as described above.

TX-114 phase separations with rTromp1 were performed as follows. Two micrograms of nonrenatured or renatured rTromp1 was added to 500 μl of 2% TX-114 in PBS. Phase separations were then conducted as described above.

All final aqueous and detergent phases from TX-114 phase separating experiments were combined with 10 volumes of ice-cold acetone, and the resulting precipitate was recovered by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min. Pellets were solubilized in sample buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE by using 12% acrylamide slab gels, and then transferred to PVDF blotting membranes as previously described (35). For immunoblotting, PVDF membranes were probed with anti-rTromp1 serum, generated as previously described (7), which was diluted 1:1,000 in 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS. Antigen-antibody binding was detected using the Amersham enhanced chemiluminescence system.

Porin assays.

The pore-forming ability of native and recombinant Tromp1 was examined by using planar lipid bilayers (5). Lipid bilayers made from 1.5% (wt/vol) oxidized cholesterol in n-decane were formed across a 0.2-mm2 hole separating two compartments of a Teflon chamber containing a 1 M KCl bathing solution. Bilayer formation was recognized by the fact that the membrane appeared black when viewed by incident light. Calomel electrodes were implanted in each compartment, with one connected to a voltage source and one connected to a current amplifier. Conductance data were recorded on a strip chart recorder for further analysis. Native and rTromp1 samples were diluted in 1 M KCl containing 0.1% Triton X-100 to yield a final concentration of approximately 1 μg of Tromp1 protein per ml of solution. Ten microliters of diluted sample, containing approximately 10 ng of Tromp1 protein, was added to the 1 M KCl bathing solution. Pore-forming ability was then assessed by applying a voltage of 50 mV across the lipid bilayer and measuring the increases in conductance.

CD analysis.

Circular dichroism (CD) analysis was performed on a JASCO J-600 spectropolarimeter by using a scan speed of 5 nm/min, a time constant of 8 s, and a bandwidth of 1.0 nm. Four scans were averaged for each spectrum. The baseline correction option was used to subtract a buffer baseline. Spectra were recorded from 240 to 190 nm in 1-mm pathlength cells with protein concentrations of 0.1 to 0.2 mg/ml. Spectra were analyzed for secondary structure by using a neural network algorithm (2, 23).

RESULTS

The hydrophobicity of native Tromp1 is conformation dependent.

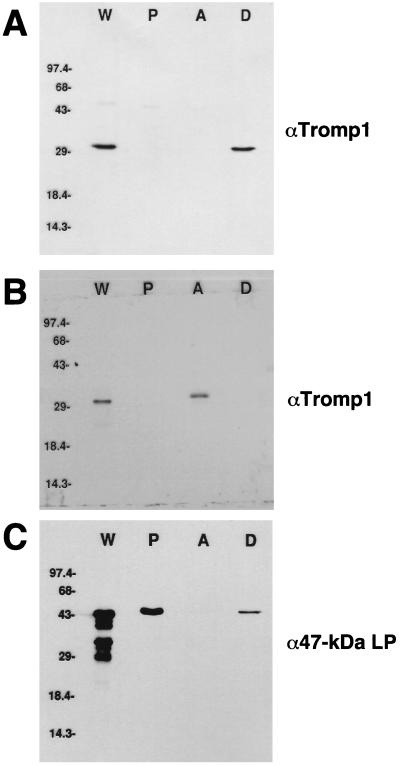

In order to investigate the basis of Tromp1’s hydrophobicity, urea treatment was utilized to test whether denaturing conditions have an effect upon this property. As previously reported (6) and again shown in Fig. 1A, 0.1% TX-114 detergent extraction of whole organisms, known to completely solubilize the T. pallidum outer membrane (12, 29), resulted in the complete release of Tromp1 with no detection present in the protoplasmic cylinders (lane P). Upon phase separation of the released material, all of the Tromp1 was present in the detergent phase (lane D), once again demonstrating the hydrophobicity of native Tromp1. However, when whole organisms were first treated with 8 M urea at 90°C prior to TX-114 extraction and phase separation, all of the Tromp1 now phase separated into the hydrophilic aqueous phase (Fig. 1B, lane A), indicating the complete loss of its hydrophobic nature. By comparison, when this same immunoblot was reprobed with a monoclonal antibody against the hydrophobic 47-kDa lipoprotein (Fig. 1C), this protein was found to remain in the detergent phase, and no detection in the aqueous phase was observed. In addition, a significant amount of 47-kDa lipoprotein remained associated with the protoplasmic cylinders (lane P), in contrast to Tromp1 and consistent with the current belief that the 47-kDa lipoprotein is inner membrane anchored (28).

FIG. 1.

Hydrophobicity of native Tromp1 is conformation dependent. A total of 108 T. pallidum organisms were extracted in 0.1% TX-114 in the presence or absence of urea prior to phase separation and SDS-PAGE. Transferred immunoblots contain whole organisms (W), protoplasmic cylinders (P), aqueous-phase proteins (A), and detergent-phase (D) proteins. Panels: A, urea-untreated fractions probed with anti-Tromp1 serum (αTromp1); B, urea-treated fractions probed with αTromp1; C, the same blot as in panel B reprobed with a monoclonal antibody against the 47-kDa lipoprotein (α47-kDa LP). Numbers on the left indicate the positions of the molecular weight standards in thousands.

Porin activity and trimer conformation of native Tromp1.

To confirm the pore-forming activity of native Tromp1, isolated previously by isoelectric focusing (6), and to analyze Tromp1’s structural characteristics, the native protein was purified from 0.1% TX-100 detergent extracts of whole organisms by FPLC. The small amount of Tromp1 present in T. pallidum and a 10% efficiency of recovery by using multiple steps of FPLC purification resulted in the isolation of only 5 μg of purified native Tromp1 from 2 × 1012 organisms. The purity of the isolated material was confirmed by silver staining after separation by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 2, single stained bands in amounts of 0.25 and 1.0 μg of electrophoresed Tromp1 were the only proteins detected. These proteins reacted specifically with anti-Tromp1 antiserum by immunoblot analysis (data not shown).

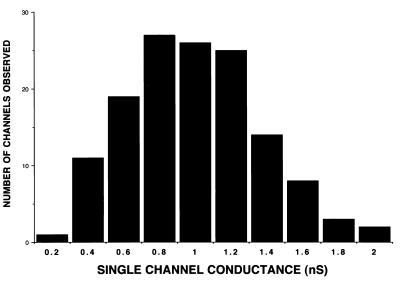

FPLC-purified native Tromp1 was next tested for porin activity by using the black lipid bilayer assay (5, 6). The addition of purified Tromp1 to the model membrane system resulted in channel formation, which was demonstrated by stepwise conductance increases across a lipid bilayer. As shown in Fig. 3, more than 136 membrane insertion events were observed with the measurement of conductance increases showing a distinct distribution about the mean of 0.96 ± 0.33 nS (± the standard deviation). This measurement was not significantly different from that of native Tromp1 isolated previously by isoelectric focusing, where the average measurement of conductance was 0.7 ± 0.21 nS (6). Interestingly, the smaller conductance measurement of 0.14 nS also observed in the previous study was not observed with FPLC-purified native Tromp1. One possible explanation for the presence of a more typical unimodal distribution of porin activity in this study is the method of purification, which did not employ electrophoresis. Regardless of these subtle differences in porin activities, these findings confirm the pore-forming activity of native Tromp1 as previously reported (6).

FIG. 3.

Porin activity of native Tromp1. FPLC-purified native Tromp1 was added to the aqueous-phase (1 M KCl) bathing a lipid bilayer membrane. Histogram of single-channel conductance increases for over 136 membrane insertion events. Conductance increases showed a mean distribution ca. 0.96 ± 0.33 nS (± the standard deviation).

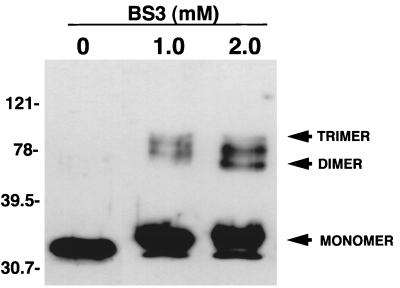

Because porin proteins of gram-negative bacteria exist in trimeric conformations, we incubated purified native Tromp1 with an 11-Å cross-linking agent to determine whether Tromp1 also exists in an oligomeric form. As shown in Fig. 4, samples of cross-linked Tromp1 (1.0 and 2.0 mM BS3 cross-linker) treated with urea containing sample buffer prior to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis showed oligomeric forms of the protein consistent with dimers and trimers. Native Tromp1 not treated with the cross-linking agent showed no oligomeric forms. These results are identical to reported studies with cross-linking agents with the porins PhoE from E. coli (3), OprP from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (34), and OmpL1 from Leptospira kirschneri (31). Thus, these results indicate that native Tromp1, like that for other porin proteins, exists in a trimeric conformation.

FIG. 4.

Molecular cross-linking of FPLC-purified native Tromp1. Samples containing 1 μg of native Tromp1 were incubated in the cross-linker BS3 at the concentrations indicated. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted, and probed with anti-Tromp1 serum. Arrows indicated the molecular mass position of monomeric Tromp1 and positions of putative dimeric and trimeric forms of Tromp1. Numbers on the left indicate the positions of the molecular weight standards (in thousands).

Renaturation of a signal-less form of rTromp1 into a trimeric, hydrophobic, and porin-active conformation.

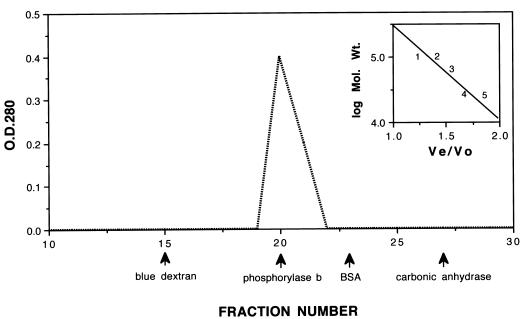

In an attempt to recreate the functional and structural properties observed for native Tromp1, a 31,109-Da signal-peptide-lacking form of rTromp1 was expressed, purified, and subjected to a renaturation procedure previously reported for recombinant neisserial porins (27, 32). As shown in Fig. 5, all renatured rTromp1 loaded onto a Sephacryl gel exclusion column, previously calibrated with known molecular mass standards, eluted at the position of the phosphorylase b standard, which is 97 kDa. By comparison, all nonrenatured rTromp1, loaded onto the same column, eluted at the position of the carbonic anhydrase standard, which is 29 kDa (Fig. 5, inset). This finding suggested that renaturation resulted in the complete trimerization of all rTromp1.

FIG. 5.

Sephacryl S-300 column elution profile of renatured rTromp1. Renatured rTromp1 was loaded onto an S-300 column previously calibrated with the following molecular mass standards: blue dextran (200 kDa), phosphorylase b (97 kDa), bovine serum albumin (BSA; 67 kDa), and carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa). The inset shows the elution profile as a function of the log molecular mass versus the eluted volume. Numbers in the inset indicate the following: 1, phosphorylase b; 2, renatured rTromp1; 3, bovine serum albumin; 4, nonrenatured rTromp1; and 5, carbonic anhydrase.

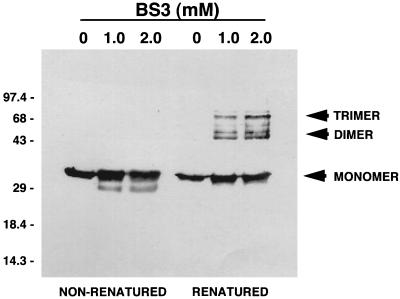

In order to confirm that renatured rTromp1 was in a trimeric conformation, renatured and nonrenatured rTromp1 were both treated with the 11-Å cross-linking agent BS3. As shown in Fig. 6, cross-linking treatment of nonrenatured rTromp1 showed no oligomeric forms. A slightly smaller form was detected, possibly reflecting altered mobility due to intramolecular cross-linking. By comparison, renatured rTromp1 treated with the cross-linking agent resulted in the detection of oligomeric forms consistent with dimers and trimers that were, again, similar to those detected for native Tromp1.

FIG. 6.

Molecular cross-linking of nonrenatured and renatured rTromp1. Samples containing 1 μg of nonrenatured and renatured Tromp1 were incubated in the cross-linker BS3 at the concentrations indicated. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted, and probed with anti-Tromp1 serum. Arrows indicate the molecular mass positions of monomeric rTromp1 and the positions of putative dimeric and trimeric forms of rTromp1. Numbers on the left indicate the positions of the molecular weight standards (in thousands).

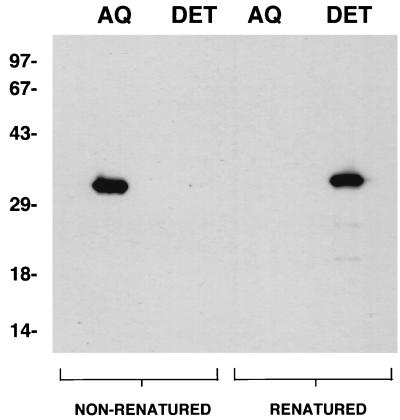

In view of the demonstrated hydrophobicity of native Tromp1, we tested whether renatured rTromp1 had also attained hydrophobic properties. As shown in Fig. 7, TX-114 treatment of nonrenatured rTromp1 resulted in the complete phase separation of this material into the aqueous phase. This same finding was also recently reported by Akins et al. (1) for a signal peptide lacking form of rTromp1. In contrast, all of the renatured rTromp1 was shown to phase separate exclusively into the detergent phase, indicating that renaturation resulted in a conformation with hydrophobic properties that were, again, similar to those of native Tromp1.

FIG. 7.

Renatured rTromp1 is hydrophobic. Samples containing nonrenatured and renatured rTromp1 were combined with TX-114 and phase separated into aqueous (AQ) and detergent (DET) phases prior to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. The blot was probed with anti-Tromp1 serum. Numbers on the left indicate the positions of the molecular weight standards (in thousands).

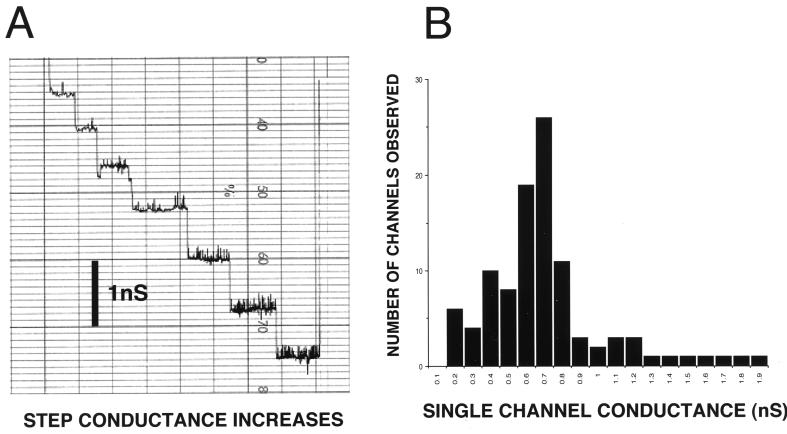

Finally, renatured rTromp1 was tested for porin activity. As shown in Fig. 8, the addition of renatured rTromp1 to the model membrane system resulted in channel formation, which was demonstrated by stepwise conductance increases across a lipid bilayer (Fig. 8A). More than 104 membrane insertion events were observed (Fig. 8B), and the measurement of conductance increases showed a distinct distribution about the mean of 0.65 ± 0.24 nS (± the standard deviation). This measurement was also not significantly different from that measured previously for rTromp1 localized to the E. coli outer membrane after expression with its native signal peptide (7). In the previous study, however, a bimodal distribution was observed resulting in activities of 0.76 ± 0.10 nS, a result again similar to that observed in this study, and 0.4 ± 0.20 nS. The observation in this study of a more typical unimodal distribution in porin activity may be the result of using purified rTromp1 in contrast to the previous study where exported and outer membrane-targeted rTromp1 that was used also contained some E. coli proteins. In contrast, no channel activity was observed after the addition to the model membrane system of nonrenatured rTromp1 (data not shown). Thus, the results of this study indicate that the demonstrated porin activity of Tromp1 is dependent upon its conformation.

FIG. 8.

Porin activity of renatured rTromp1. Renatured rTromp1 was added to the aqueous phase (1 M KCl) bathing a lipid bilayer membrane. (A) Step increases in conductance after the addition of renatured rTromp1. (B) Histogram of single-channel conductance increases for more than 104 membrane insertion events. Conductance increases showed a mean distribution about 0.65 ± 0.24 nS (± the standard deviation). No conductance activity was observed for nonrenatured rTromp1 added to the lipid bilayer membrane (data not shown).

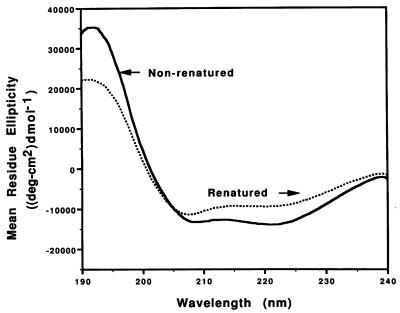

Comparison of nonrenatured and renatured rTromp1 by CD spectroscopy.

In order to determine whether renaturation had resulted in a measurable change in the secondary structure of rTromp1, both nonrenatured and renatured rTromp1 were analyzed by CD spectroscopy. The CD spectrum of nonrenatured rTromp1 displayed prominent double minima (negative peaks) at 208 and 222 nm (Fig. 9), findings typical for a protein with considerable alpha-helical secondary structure. By using a neural network algorithm (2, 23) nonrenatured rTromp1 was calculated to possess 48% alpha-helix, 18% beta-sheet, and 34% random coil. Similar findings have been reported by Akins et al. (1) for their signal-peptide-lacking form of recombinant Tromp1. In contrast, the CD spectrum of renatured rTromp1 reflected a loss of alpha-helical structure, with the magnitude of the 222- and 208-nm peaks reduced relative to nonrenatured rTromp1 and the 222-nm peak reduced relative to the 208-nm peak. Renatured rTromp1 was calculated to contain 26% alpha-helix, 17% beta-sheet, and 57% random coil. These findings provide quantitative evidence that renaturation of rTromp1 leads to changes in the secondary structure of the molecule, with the renatured form having less alpha-helix than the nonrenatured form.

FIG. 9.

Secondary structure analysis of nonrenatured and renatured rTromp1 by CD spectroscopy. The double minimum absorbances displayed by nonrenatured rTromp1 (solid line) is typical of proteins with a high percentage of alpha-helix. By comparison, renatured rTromp1 (dotted line) showed a distinct loss in absorbance at 222 nm, indicating a loss in alpha-helical secondary structure.

DISCUSSION

Protein conformation has been recognized for gram-negative membrane-spanning outer membrane porins to be a key factor to their structural and functional properties (11). Immunologically relevant epitopes involved in bactericidal activity have been attributed to porin conformation (14, 34, 39). Structural analysis of porins, including X-ray crystallography studies, has only been performed with purified native porins because native conformation of these proteins has not been faithfully replicated with recombinant forms. However, there has been progress in this area since it has been shown recently that recombinant forms of the gonococcal, meningococcal, and Haemophilus influenzae porins can be renatured into conformations which have several properties in common with their respective native proteins, including trimerization and porin function (26, 27, 32), suggesting that native conformation is attainable with a recombinant.

The importance of renaturation of a recombinant porin protein has particular significance to the study of porins of T. pallidum, an organism which can only be acquired in limited numbers from infected animals and whose membrane-spanning outer membrane protein content is 100-fold less than that of typical gram-negative bacteria (30, 38). These limitations have all but eliminated the use of native T. pallidum porin for structural studies which require milligram quantities of material, such as for X-ray crystallography, which will undoubtedly rely in the future on a renatured recombinant.

In this study, the ability to renature a signal-peptide-lacking form of recombinant Tromp1 into a hydrophobic, trimeric, and porin-functional conformation, properties which we also show for native Tromp1, provides strong evidence that the conformation of Tromp1 is a central issue to the native biological properties of this protein. Indeed, denaturation of native Tromp1 with the chaotropic agent urea abrogates the hydrophobicity of the native protein, a property which is consistent with Tromp1 being located in the outer membrane.

The significance of these findings has important implications in view of recent reports pertaining to Tromp1. Akins et al. reported that a signal-peptide-lacking construct of recombinant Tromp1 was not hydrophobic and showed no porin activity as demonstrated by the liposome swelling assay (1). These findings were used to support the conclusion by these investigators that Tromp1 is not an outer membrane protein. In a recent further study with recombinant Tromp1 (TroA) constructs containing and lacking a signal peptide, these investigators have again concluded that the hydrophobicity of native Tromp1 is the result of its hydrophobic signal peptide (13). However, our recent mass spectrometry analysis of the hydrophobic form of native Tromp1 has now clearly demonstrated that the signal peptide is cleaved (10). Recently, a crystal structure of a nonrenatured monomeric form of recombinant Tromp1 (TroA) has been reported and used to conclude that Tromp1 (TroA) is a periplasmic zinc-binding protein (13, 21). While the finding that recombinant Tromp1 monomers can bind zinc may have important implications in regard to its structure and function, our findings that native Tromp1 and renatured recombinant Tromp1 are trimeric in conformation have provided structural data which is inconsistent with Tromp1 being a typical metal-binding periplasmic protein, since these proteins have been shown to be single polypeptide chain monomers in their functional state (19, 37). In addition, the hydrophobicity and porin activity of both native and renatured recombinant Tromp1 are also inconsistent with its being a typical periplasmic binding protein.

One possible explanation for this paradox is that divergent evolution has enabled pathogenic bacteria to use homologues of ABC transporter operons for diverse purposes related, perhaps, to biological function and pathogenesis. Consistent with this possibility is the finding that a related ABC operon system is also found with the surface adhesin proteins of streptococci. Here the periplasmic binding protein homologue is replaced by a surface adhesin (20, 22), which interestingly, also shares 23 to 28% sequence identity to Tromp1 (6). Yet another example where a gene encoding a surface layer protein occupies the position analogous to that of tromp1 in an ABC transporter operon is found in Caulobacter crescentis (4). Thus, the observation that Tromp1 has biological properties consistent with an outer membrane porin protein but has genetic homology to ABC transporter components from gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria may not be inconsistent in the context of a divergent evolutionary process of genes from this spirochete.

Although Tromp1 has physical properties consistent with outer membrane porin proteins from gram-negative bacteria, including hydrophobicity and trimer conformation, it does not appear to share secondary structure characteristics with these proteins. Porins of gram-negative bacteria are known to possess significant amounts of beta-sheet secondary structure, usually greater than 50%, and very little alpha-helical secondary structure, usually less than 15% (36). This has also been found to be the case for the pathogenic spirochete L. kirschneri, whose porin protein OmpL1 has 61% beta-sheet and 19% alpha-helical secondary structure (17). By comparison, computer analysis of the amino acid sequence of Tromp1 has revealed only 34% beta-sheet secondary structure and 56% alpha-helix secondary structure. While CD analysis of renatured recombinant Tromp1 showed a significant loss of alpha-helical secondary structure compared to the nonrenatured recombinant, no corresponding increase in beta-sheet secondary structure was observed. One possible explanation for this finding is that renatured recombinant Tromp1 may not have faithfully replicated native conformation. An alternative explanation for these observations is that membrane-spanning outer membrane proteins of T. pallidum may utilize a secondary structure conformation other than the beta-sheet to span the outer membrane. It is pertinent to note that the T. pallidum outer membrane, unlike that of gram-negative bacteria or other spirochetes with the exception of Borrelia burgdorferi, does not contain lipopolysaccharide. It is also pertinent to note that analysis of the recently released genome sequences of T. pallidum and B. burgdorferi (15, 16) have not revealed any protein with typical gram negative porin protein secondary structure characteristics. Thus, the outer membrane-spanning proteins of these two spirochetes, while having functional properties similar to those of gram-negative outer membrane proteins, may have quite different membrane-spanning structural properties.

The renaturation of recombinant Tromp1 into a conformation which parallels that of the native protein has now provided for sufficient amounts of material to be used in studies designed to address issues of pathogenesis and host immunity. To date, no T. pallidum recombinant protein used for immunization has elicited complete protective immunity in experimental animals comparable to that achieved by infection-derived immunity.

In summary, the results presented in this study demonstrate that the properties of native Tromp1, an outer-membrane-associated protein that is hydrophobic, trimeric in structure, and porin active, can be successfully recreated by renaturation of purified recombinant Tromp1. We believe that native conformation of T. pallidum outer membrane proteins will be found to be a critical issue in determining the role of these proteins in syphilis pathogenesis and immunity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Xiao-Yang Wu for his excellent technical assistance in this study.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants AI-21352 and AI-12601 (to M.A. Lovett) and AI-37312 (to J.N. Miller).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins D R, Robinson E, Shevchenko D, Elkins C, Cox D L, Radolf J D. Tromp1, a putative rare outer membrane protein, is anchored by an uncleaved signal sequence to the Treponema pallidum cytoplasmic membrane. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5076–5086. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5076-5086.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade M A, Chacon P, Merelo J J, Moran F. Evaluation of secondary structure of proteins from UV circular dichroism using an unsupervised learning neural network. Prot Eng. 1993;6:383–390. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus B L, Hancock R E W. Outer membrane porin proteins F, P, and D1 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and PhoE of Escherichia coli: chemical cross-linking to reveal native oligomers. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:1042–1051. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1042-1051.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awram P, Smit J. The Caulobacter crescentus paracrystalline S-layer protein is secreted by an ABC transporter (type I) secretion apparatus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3062–3069. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3062-3069.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benz R, Hancock R E W. Properties of the large ion-permeable pores formed from protein F of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in lipid bilayer membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;646:298–308. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco D R, Champion C I, Exner M M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Hancock R E W, Tempst P, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Porin activity and sequence analysis of a 31-kilodalton Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum rare outer membrane protein (Tromp1) J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3556–3562. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3556-3562.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco D R, Champion C I, Exner M M, Shang E S, Skare J T, Hancock R E W, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Recombinant Treponema pallidum rare outer membrane protein 1 (Tromp1) expressed in Escherichia coli has porin activity and surface antigenic exposure. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6685–6692. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6685-6692.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanco D R, Reimann K, Skare J, Champion C I, Foley D, Exner M M, Hancock R E W, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Isolation of the outer membranes from Treponema pallidum and Treponema vincentii. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6088–6099. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6088-6099.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco D R, Walker E M, Haake D A, Champion C I, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Complement activation limits the rate of in vitro treponemicidal activity and correlates with antibody-mediated aggregation of Treponema pallidum rare outer membrane protein (TROMP) J Immunol. 1990;144:1914–1921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanco D R, Whitelegge J P, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Demonstration by mass spectrometry that purified native Treponema pallidum rare outer membrane protein 1 (Tromp1) has a cleaved signal peptide. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5094–5098. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.5094-5098.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowan S W, Schirmer T, Rummel G, Steiert M, Ghosh R, Pauptit R A, Jansonius J N, Rosenbusch J P. Crystal structures explain functional properties of two Escherichia coli porins. Nature. 1992;358:727–733. doi: 10.1038/358727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham T M, Walker E M, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Selective release of the Treponema pallidum outer membrane and associated polypeptides with Triton X-114. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5789–5796. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5789-5796.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deka R K, Lee Y, Hagman K E, Shevchenko D, Lingwood C A, Hasemann C A, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Physiochemical evidence that Treponema pallidum TroA is a zinc-containing metalloprotein that lacks porin-like structure. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4420–4423. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.14.4420-4423.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elkins C, Barkley K B, Carbonetti N H, Coimbre A J, Sparling P F. Immunobiology of purified recombinant outer membrane porin protein I of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:1059–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser C M, Norris S J, Weinstock G M, White O, Sutton G G, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Clayton R, Ketchum K A, et al. Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science. 1998;281:375–388. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haake D A, Champion C I, Martinich C, Shang E S, Blanco D R, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding OmpL1, a transmembrane outer membrane protein of pathogenic Leptospira spp. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4225–4234. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4225-4234.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardham J M, Stamm L V, Porcella S F, Frye J G, Barnes N Y, Howell J K, Mueller S L, Radolf J D, Weinstock G M, Norris S J. Identification and transcriptional analysis of a Treponema pallidum operon encoding a putative ABC transport system, an iron-activated repressor protein homolog, and a glycolytic pathway enzyme homolog. Gene. 1997;197:47–64. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins C F. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolenbrander P E, Andersen R N, Baker R A, Jenkinson H F. The adhesion-associated sca operon in Streptococcus gordonii encodes an inducible high-affinity ABC transporter for Mn2+ uptake. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:290–295. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.290-295.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee Y, Deka R K, Norgard M V, Radolf J D, Hasemann C A. Treponema pallidum TroA is a periplasmic zinc-binding protein with a helical backbone. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:628–633. doi: 10.1038/10677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe A M, Lambert P A, Smith A W. Cloning of an Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis antigen: homology with adhesins from some oral streptococci. Infect Immun. 1995;63:703–706. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.703-706.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merelo J J, Andrade M A, Prieto A, Moran F. Proteinotopic feature maps. Neurocomputing. 1994;6:443–454. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller J N, Whang S J, Fazzan F P. Studies on immunity in experimental syphilis. II. Treponema pallidum immobilization (TPI) antibody and the immune response. Br J Vener Dis. 1963;39:199–203. doi: 10.1136/sti.39.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Partis M D, Griffiths D G, Roberts G C, Beechey R B. Cross-linking of protein by ω-maleimido alkanoyl N-hydroxysuccinimido esters. J Prot Chem. 1983;2:263–277. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pullen J K, Liang S M, Blake M S, Mates S, Tai J Y. Production of Haemophilus influenzae type-b porin in Escherichia coli and its folding into the trimeric form. Gene. 1995;152:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00706-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi H L, Tai J Y, Blake M S. Expression of large amounts of neisserial porin proteins in Escherichia coli and refolding of the proteins into native trimers. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2432–2439. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2432-2439.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radolf J D. Treponema pallidum and the quest for outer membrane proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1995;6:1067–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radolf J D, Chamberlain N R, Clausell A, Norgard M V. Identification and localization of integral membrane proteins of virulent Treponema pallidum by phase partitioning with the nonionic detergent Triton X-114. Infect Immun. 1988;56:490–498. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.490-498.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radolf J D, Norgard M V, Shulz W W. Outer membrane ultrastructure explains the limited antigenicity of virulent Treponema pallidum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2051–2055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shang E S, Exner M M, Summers T A, Martinich C, Champion C I, Hancock R E W, Haake D A. The rare outer membrane protein, OmpL1, of pathogenic Leptospira species is a heat-modifiable porin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3174–3181. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3174-3181.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song J, Minetti C A, Blake M S, Colombini M. Successful recovery of the normal electrophysiological properties of PorB (class 3) porin from Neisseria meningitidis after expression in Escherichia coli and renaturation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1370:289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srikumar R, Dahan D, Gras M F, Saarinen L, Kayhty H, Sarvas M, Vogel L, Coulton J W. Immunological properties of recombinant porin of Haemophilus influenzae type b expressed in Bacillus subtilis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3334–3341. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3334-3341.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sukhan A, Hancock R E W. Insertion mutagenesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa phophate-specific porin OprP. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4914–4920. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4914-4920.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of protein from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogel H, Jahnig F. Models for the structure of outer-membrane proteins of Escherichia coli derived from Raman spectroscopy and prediction methods. J Mol Biol. 1986;190:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vyas N K, Vyas M N, Quiocho F A. Comparison of the periplasmic receptors of l-arabinase, d-glucose/d-galactose and d-ribose. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5226–5237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker E M, Zamphigi G A, Blanco D R, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Demonstration of rare protein in the outer membrane of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum by freeze-fracture analysis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5005–5011. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5005-5011.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward S J, Scopes D, Christodoulides M, Clarke I N, Heckels J E. Expression of Neisseria meningitidis class 1 porin as a fusion protein in Escherichia coli: the influence of liposomes and adjuvants on the production of a bactericidal immune response. Microb Pathog. 1996;21:499–512. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]