Abstract

Background

As the incidence of COVID-19 is increasing, the Bangladesh government has announced a countrywide shutdown instead of a lockdown. Consequently, front-line healthcare workers, particularly nurses, are confronting more challenging situations at work.

Objective

This study aimed to explore front-line nurses’ experiences caring for patients with COVID-19 in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Methods

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted among front-line nurses caring for patients with COVID-19. Twenty nurses were purposively chosen from January to March 2021 to participate in semi-structured online interviews. Interviews on audio and video were collected, analyzed, interpreted, transcribed verbatim, and verified by experts. Thematic analysis was used.

Results

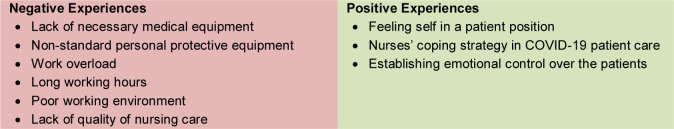

Nine themes emerged and were grouped into negative and positive experiences. The themes of negative experiences include lack of necessary medical equipment, use of non-standard personal protective equipment, work overload, long working hours, poor working environment, and lack of quality of nursing care. The positive experiences include feeling self in a patient position, nurses’ coping strategy in COVID-19 patient care, and establishing emotional control.

Conclusion

The study results encourage national and international health care professionals to cope with adverse working environments. Also, the findings provide nurses with techniques for dealing with any critical situation, controlling patients’ emotions, and how empathy increases self-confidence and patient care. The research should also be used to enhance government policy, nursing council policy, ministry of health policy, and other healthcare agencies.

Keywords: COVID-19, nurses, workplace, patient care, health personnel, experience, healthcare, Bangladesh

The third wave of COVID-19 is currently underway in Bangladesh (Huq, 2021). In March 2020, the virus was discovered to have transmitted to Bangladesh. The country’s epidemiology institute identified the first three confirmed cases on 8 March 2020 (Reuters., 2020). Since then, the outbreak has spread throughout the entire country, with the number of individuals infected steadily increasing. There have been 954,881 reported cases of COVID-19 in Bangladesh, with 15,229 deaths, from 3 January 2020 to 5 July 2021 (Worldometer, 2021). Common symptoms of COVID-19 are shortness of breath, fever, dry cough, fatigue, headache, body aches, sore throat, etc. (Mamun et al., 2021). To safeguard the public, the government proclaimed a “shutdown” rather than a lockdown across the country from 1 July to 14 July 2021 and planned some required procedures to raise awareness and prevent this syndrome from affecting them (Aljazeera, 2021).

COVID-19 outbreak highlights the inept healthcare systems of many developing countries, including Bangladesh, covered by incompetence and negligence. Bangladesh has recently struggled to cope with coronavirus (COVID-19) patients due to a lack of oxygen deficit and difficulties in providing equipment to government and private healthcare facilities across the country (Jamuna TV, 2021). With a shortage of roughly 50,000 physicians, nurses, medical technicians, ward boys, and health workers in the country (Dhaka Tribune, 2020), Bangladesh is combating the devastating coronavirus.

Nursing is an independent profession. Nurses play a vital role in ensuring patient safety (Marzilli, 2021). As the need for health care in hospitals, society, and communities grows, the nurse’s function evolves. All across the healthcare sector, nurses perform critical services. During the COVID-19 epidemic, nurses have significant roles and responsibilities (Abuhammad et al., 2021). Infectious illness prevention procedures are implemented by nurses to keep the coronavirus from spreading (Lu et al., 2020). The quality of service depends on the healthcare facilities and the opportunities available to nurses (Dawson et al., 2014). Because the satisfaction of nurses and the quality of healthcare are interlinked (Aungsuroch et al., 2020). There is no research in Bangladesh on the experience of nurses during this epidemic. This study will shed light on the direct experience of nurses and their perceptions in managing COVID-19 situations.

Methods

Study Design

From January to March 2021, a qualitative descriptive study was conducted to explore the experiences of front-line nurses caring for patients with COVID-19.

Participants

Twenty nurses were purposively selected from various private and government hospitals in Dhaka city to explore the actual experience and perceptions of the nurses in managing the COVID-19 situation. Criteria for the inclusion of respondents were bedside nurses directly involved in the care of patients with COVID-19.

Data Collection

The hospital authorities provided respondents’ email addresses and phone numbers. The participants were sent an invitation email. If they accepted, every participant in this study took part in an online semi-structured audio-video interview scheduled for 30 to 40 minutes. The interviews were conducted entirely in Bengali. A single interview session was held for each participant, and all interviewees were interviewed via the Google Meet platform. Before data collection, questionnaire guidelines were developed.

Data Analysis

Data were translated from Bengali to English. Thematic analysis was utilized to analyze the data in this study. Thematic analysis is a process by which emerging themes are drawn from data to describe a specific aspect of the experience. Thematic analysis is a simple, adaptable, and effective tool for determining qualitative data (Brooks et al., 2015).

Ethical Consideration

This study received ethical approval from Bangladesh Public Health Research Association. (Approval number: GOV-PHRCB-098621-2021). Before doing the interview, online consent was obtained from the participants, and the information obtained was kept confidential.

Trustworthiness

Data were recorded by an electronic device to achieve the study’s credibility. All researchers repeatedly checked the data for validation. A qualitative research expert conducted an audit trail to ensure confirmation and transferability of the study. Finally, member checking was done to ensure the original results and dependability of the study.

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

A total of twenty respondents participated in this study. Participants ranged in age from 25 to 45 years (Mean= 30.95 years; SD= 5.87). Majority of the participants were females (n=13; 65%), married (n=14; 70%), working in government hospitals (n=11; 55%), having more than six years of working experience (n=9; 45%), and working in more than 300 bedded hospitals (n=12; 60%). Most of the nurses have a master’s degree in public health (n=15; 75%), followed by a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (n=4; 20%) and a Diploma in Nursing Science and Midwifery (n=1; 15%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants (N=20)

| Participants | Age (year) | Marital status | Gender | Educational qualification | Experience (year) | Job type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 25 | No | F | BSN, RN | 1.5 | Private |

| P2 | 30 | yes | M | BSN, MPH, RN | 7 | Government |

| P3 | 27 | No | F | BSN, RN | 3.5 | Private |

| P4 | 28 | No | M | BSN, MPH, RN | 3 | Government |

| P5 | 32 | yes | F | BSN, MPH, RN | 8.5 | Government |

| P6 | 28 | yes | M | BSN, MPH, RN | 4 | Government |

| P7 | 27 | No | M | BSN, MPH, RN | 2.5 | Private |

| P8 | 40 | yes | F | BSN, MPH, RN | 15.5 | Government |

| P9 | 25.5 | No | M | Diploma, RN | 1.6 | Private |

| P10 | 36 | yes | F | BSN, MPH, RN | 12 | Government |

| P11 | 30 | yes | F | BSN, MPH, RN | 6.5 | Government |

| P12 | 27 | yes | F | BSN, MPH, RN | 2.6 | Private |

| P13 | 26 | No | F | BSN, RN | 1.5 | Private |

| P14 | 45 | yes | M | BSN, MPH, RN | 20.5 | Government |

| P15 | 42 | yes | F | BSN, MPH, RN | 18 | Government |

| P16 | 37 | yes | F | BSN, MPH, RN | 13.5 | Government |

| P17 | 33 | yes | M | BSN, MPH, RN | 7.5 | Government |

| P18 | 26 | yes | F | BSN, RN | 1.5 | Private |

| P19 | 28 | yes | F | BSN, MPH, RN | 3.5 | Private |

| P20 | 26.5 | yes | F | BSN, MPH, RN | 1.8 | Private |

Thematic Findings

The study revealed nine themes categorized into two groups: negative and positive experiences (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Thematic findings

Negative experiences

Lack of necessary medical equipment

The majority of the respondents claimed that there is a lack of necessary medical equipment in the hospital. Such as a BP machine, pulse oximeter, thermometer, syringe pump, etc. Also, a shortage of stainless-steel premium instruments. participants described the following statements:

A thermometer for more than forty COVID-19 patients. Sometimes we only feel by hand whether the patient has a high temperature or not. (P7)

The nurses take one serial after another to get the BP machine and pulse oximeter to check the patient’s vital signs. (P2)

Delay in some patient’s morning care due to lack of kidney tray, artery forces, and other equipment. (P10)

We have no enough ventilator support to save the COVID-19 patient as per patient quantity. (P1)

Non-standard personal protective equipment

Most participants agreed that their hospital had Non-standard personal protective equipment (PPE). Respondents also expressed concern about becoming sick since they lack proper PPE. Such as masks, gloves, and gowns. Sometimes infected patients could come into the hospital at any moment. Respondents narrated the following statement:

My hospital gave me a pair of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) that were of low quality, so my husband got me two pairs that were of good quality. (P8)

Our Surgical mask belts sometimes break within hours of use. And some mask belts break while wearing the mask. (P17)

Surgical glove tears while working. (P20)

Surgical gowns are thick and uncomfortable, and nurses always sweat. (P14)

Hospitals do not provide face shields but sometimes provide surgical caps. (P6)

A large number of nurses are affected. Despite receiving the first dose, I was affected twice. My father and husband are now positive. (P12)

Work overload

Most of the respondents described that the work overload of nurses is common in every hospital. Nurses are working longer hours than ever before due to a shortage of nursing staff, an increase in the number of patients, and an increase in working hours. Workload results in nursing burnout, and nurses are more likely to quit their jobs. Participants narrated the following statement:

Like dying while working. The verbatim was in Bangla -“kam korte korte mori” (P3)

A nurse is responsible for more than 40 patients per shift. (P19)

We forget to check the vitals of the patients because of my busy schedule. Duty time is utilized only to execute nursing procedures and administer medications to patients. Because a nurse in a government hospital typically deals with more than 70 patients. (P15)

We can’t take a break during my workday, and we don’t always have the opportunity to use the washroom due to a heavy workload. (P11)

One of our physicians misbehaved with us last month. This is why I arrived five minutes late on his visit. However, I was late because I was dealing with another patient. (P6)

Long working hours

The majority of participants stated that nurses work long shifts. As a response to institutional demands, nurses have to work extra hard to satisfy particular standards. The following information was reported by the respondents:

Our working hours are 48 hours per week. However, we have to devote an additional two hours each day. (P9)

In a month, we get four days off in phases, and two days of night duty leave are deducted from the overall four-day leave. (P17)

Even though I’m pregnant, I work the night shift once a month for more than seven days. (P12)

Poor working environment

The majority of interviewees stated that the working environment in Bangladeshi hospitals is very unfavorable. The biggest hurdles to ensuring a healthy and patient-friendly atmosphere in practically all public and private hospitals in the country are inadequate department design, a lack of space, a defective waste management system, and irregularities by the authorities concerned. The following statement was narrated by the participants:

Due to a limited area in the ward, we take up space that bothers other patients during nursing procedures. (P18)

There is no extra dirty room, and the waste bin is adjacent to the patient’s bed. (P2)

At any time, patient attendants are allowed to visit the ward, and multiple attendants crowded the patient’s bedside. (P10)

Physicians utilize the nurses’ restroom. (P19)

The working environment is excessively noisy, and the patients are displeased. (P5)

Lack of quality of nursing care

The participants in the study believed that the quality of nursing care in Bangladesh isn’t up to standard. The following comments have been given by the participants about healthcare organizations:

You’d imagine, “What will the quality of care be if I have to deal with more than 40 patients?” (P14)

Due to a shortage of time, we are unable to provide enough mental support to the patient. (P8)

The patient must wait for nursing intervention because of a lack of hospital resources and nursing staff. (P11)

We utilize the same gloves for different patients due to a lack of gloves and excessive work pressure. (P3)

Positive experiences

Feeling self in a patient position

Nurses are not just caregivers, but they also have empathy for their patients to deliver the best possible care. Nurses imagine themselves in the position of their patients to determine whatever kind of care they want. The participants recounted the following responses:

I imagine myself in the position of a patient. If I were a patient, what kind of care would I like to receive? (P4)

Whenever I look after a patient, I wonder what kind of care I would provide if the patient was my brother or sister. (P16)

As a nurse, we never have the impression that our patient is a stranger. (P13)

Nurses’ coping strategy in COVID-19 patient care

It was challenging for nurses to cope with COVID-19 patient care during the start of the pandemic. However, after a year of COVID-19 patient care, nurses have adapted to the pandemic situation and are adopting the following coping strategies.

I battled with work-life balance when I first started working with patients with COVID-19. But after starting to pray regularly, I am now more confident in performing my responsibilities as a nurse. (P9)

I occasionally meditate, which helps me stay mentally strong so that I can balance my work life and personal life. (P5)

I’m no longer worried about caring for patients with COVID-19. In this epidemic, I understood that nurses are always on the front lines of patient care, whether patients are life-threatening or not. (P15)

We interact with patients in a playful manner, and they are really satisfied with us. (P4)

Patients’ reliance on us makes me more confident. (P1)

Establishing emotional control over the patients

Nurses foster positive relationships with patients in order to understand their feelings and provide adequate interventions. Among the responses of participants, we found the following comments:

I try to understand my patients’ emotions, which aids in both controlling and caring for them. (P16)

In order to better understand patients and manage their attendants, I make an effort to form strong bonds with patients. It aids me in providing adequate professional care. (P13)

To overcome the fear of COVID-19. I strive to comprehend the variables that contribute to my patients’ stress to control my patient’s worry. (P7)

Discussion

This study aimed to explore front-line nurses’ experiences in caring for patients with COVID-19 in Dhaka, Bangladesh. We discovered the negative and positive experiences, which are discussed in the following:

Front-line nurses’ negative experiences

Firstly, nurses said that their clinical setting lacked the appropriate medical equipment, making it impossible to provide adequate nursing care. It is in line with The Daily Star (2019) that seven out of ten healthcare facilities in Bangladesh lack all necessary equipment. Al-Zaman (2020) also mentioned that most hospitals in Bangladesh have a medical equipment scarcity that harms patients and attendants and is a life-threatening condition.

Secondly, participants stated that the highest number of hospitals offered substandard personal protective equipment to nurses causing them to suffer. To protect nurses first, it is necessary to provide high-quality personal protective equipment (Bala et al., 2021). How can a patient be treated when nurses fail to protect themselves from virus transmission (Gunawan et al., 2021)?

Thirdly, nurses face challenges due to an obscure job and the burden of excessive and inappropriate nursing. The lack of equitable work pressure among nurses reduces the quality of patient care and the nurse’s motivation. Nursing is high-work stress, according to Umansky and Rantanen (2016). And it has been proven that too much work harms patient care (Myny et al., 2011). Moreover, the risk of infection in the healthcare sector due to increased workload is considerable.

Fourthly, the majority of the responders worked with patients with COVID-19 for extended periods. Vacations were particularly infrequent in this pandemic circumstance, which caused nurses to be depressed. Hospital nurses who work long shifts are more likely to experience burnout and patient dissatisfaction (Stimpfel et al., 2012). In addition, long-shift nurses face physical and psychological strain and the risk of injury and illness (Zhan et al., 2020).

Fifthly, the patients have very inadequate access to healthcare. The majority of healthcare facilities are unsuitable for treating patients with COVID-19 (Anwar et al., 2020). When care for patients, the quality of the hospital environment is crucial (Morawska et al., 2020). Controlling viral infections and diseases must be ensured. Adequate ward space, a proper waste management system (Lai et al., 2020), nurse and physician isolation rooms, and a separate nursing station are all necessary concerns for dealing with patients with COVID-19 (Phan et al., 2019).

Sixthly, most healthcare organizations do not deliver high-quality nursing care. Patients want to get high-quality nursing care (Rony, 2021). As a result, thousands of Bangladeshi patients move to other nations for better nursing care. Quality of nursing care has a significant impact on patient outcomes and safety.

As a result of the healthcare organization’s shortcomings and limited opportunities for nurses, we noticed some nurses’ burnout during the pandemic, and some nurses had a work-life imbalance. But, no one quit their job as front-line fighters, and nurses made the ultimate sacrifice in the fight against COVID-19.

Front-line nurses’ positive experiences

Because COVID is a relatively new disease, many patients are depressed, and their complete reliance on nursing makes nurses more accountable. Even though COVID-19 patient care is challenging, nurses were able to cope with direct care circumstances by imagining themselves in the patients’ position. This finding is supported by Barello and Graffigna (2020) that one of the most important aspects of dealing with patients with COVID-19 is empathy. Also, Hofmeyer and Taylor (2021) revealed that nurses should lead with empathy and caution to recognize and resolve sources of anxiety among nurses practicing in the COVID19 era.

In the theme “nurses’ coping strategy in COVID-19 patient care”, we found that front-line nurses use different techniques to deal with challenging situations while caring for patients with COVID-19. For example, we discovered that prayer and meditation help nurses refresh and adapt to the COVID-19 caring situation. Tosepu et al. (2021) said that praying for nurses to cope with COVID-19 situations is effective. On the other hand, Sun et al. (2020) noted that meditation is also a useful coping technique for adjusting to COVID-19 caregiving environments. Furthermore, nurses understood and adapted to the reality that, as a nurse, they must constantly be on the front lines to supervise patient care when dealing with an emergency, right from the beginning of the COVID-19 situation. Supporting our research, Al Thobaity and Alshammari (2020) said that nurses are first-line fighters who always provide direct patient care.

In addition, the theme “establish emotional control over the patient” indicated that nurses in the third wave of the pandemic were well prepared emotionally and confidently to handle the situation. Even today’s nurses have acquired their ability to manage patients’ emotions, allowing them to achieve better patient outcomes. Teng et al. (2009) described that understanding patients’ emotional responses substantially impact patient safety because it encourages good communication between nurses and patients, resulting in high-quality nursing care in the healthcare setting. This study is also supported by Moreno-Poyato et al. (2021) revealed that nurses should understand patients’ behavior to develop effective therapeutic communications.

The implication of this study

The findings of this study show that nursing competence is crucial in dealing with COVID-19 cases. We found that nurses were able to deal with emergencies by avoiding negative experiences. In addition, nurses were able to control their own emotions and understand the feelings of their patients. This assists the nurse in improving patient outcomes. We also found that nurses were using various coping mechanisms (meditation, prayer) to manage any stressful situation. Furthermore, we revealed how nurses feel about patients who are completely reliant on them.

For the safety of nurses and patients, our findings provide encouragement to healthcare organizations about the necessity of enough hospital resources, adequate medical equipment, and quality personal safety equipment. In addition, nurses must have a consistent work schedule and a healthy work environment in order to provide high-quality nursing care.

Our findings also provide encouragement to national and international nurses on how to cope with any critical situation, control patients’ emotions, and how empathy improves one’s self-assurance and patient care. Also, the results of this study reveal nurses’ experience and perception with patients with COVID-19. As a result, the results may not replicate across all Bangladeshi healthcare organizations. To acquire more about nurses’ coping strategies, more research is needed in diverse medical settings in Bangladesh.

Limitation of the study

With the qualitative design, the results of this study might not represent the whole context of Bangladesh. Quantitative research to confirm the findings is recommended for generalization.

Conclusion

Nurses are well-versed with the needs of patients, as well as organizational problems and actual working conditions. Nurses have strategies for dealing with crises and must be involved in policy and decision-making to provide high-quality health care. However, nurses’ demands should be fulfilled to motivate them in maintaining high performance and quality of nursing care.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Mst. Rina Parvin (Captain of Bangladesh Army, Combined Military Hospital, Sylhet, Bangladesh); Nancy Stephens (Visiting Faculty, IUBAT); Hasnat M Alamgir (Professor, IUBAT); and to all participants during the data collection process for their time and effort.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors have no competing interests in this study.

Funding

There was no external fund taken for this current research.

Authors’ Contribution

MKKR, SDB, MMR, AJD, MTI, IJT, IK, EHS, SR, MRP are involved in substantial contributions to the conception and design or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data for the work. MKKR, SDB, MMR, AJD, MTI, IJT, IK, EHS, SR are involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. MKKR, SDB, MMR, AJD, MTI, IJT, IK, EHS, SR, MRP are involved in the final approval of the version to be published, and each author participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content. MKKR, SDB, MMR, AJD, MTI, IJT, IK, EHS, SR are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Authors’ Biographies

Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, BSN, MSS, MPH, RN is working as a Faculty member at the International University of Business Agriculture and Technology (IUBAT), Dhaka, Bangladesh. Before joining the University, he was the first Bangladeshi Helicopter Emergency Medical Services Specialist / (HEMS Specialist) at Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport. He is also a Gerontologist. He studied Master in Gerontology and Geriatrics at the University of Dhaka. He is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Public Health (MPH) in public University at the School of Science and Technology, BOU. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree from Shahjalal University of Science and Technology. His research interests are in public health and the social sciences.

Shuvashish Das Bala, BSN, MPH, RN has been working as an Assistant Professor in the College of Nursing at the International University of Business Agriculture and Technology (IUBAT) since August 2015. For his excellent teaching ability and leadership skills, he was promoted as a Program Coordinator in March 2018. He has completed his graduation with BSc in Nursing from the same university he is working at now, and then he accomplished his Master in Public Health degree from ASA University of Bangladesh. Before joining IUBAT, he has served two nationals (Universal Medical College and Hospital as a Senior Staff Nurse and Ispahani Islami Eye Hospital and Institute as a Quality Assurance Officer) and one international (Médecins Sans Frontières–Holland, Dhaka as a Nurse) organization for about five years.

Md. Moshiur Rahman, BSN, MPH, MSN, RN is working as a Nursing Instructor at Nursing Institute Chapainawabganj, Bangladesh.

Afrin Jahan Dola, BSN, MSS, MPH, RN is working as a Nursing Instructor at Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Ibne Kayesh, BSN, MSS, MPH, RN is working as a Principal at MRM Hospital & Nursing Institute, Bancharampur, Brahmmanbaria, Bangladesh.

Md. Tawhidul Islam, BSN, MSc, RN is working as a Lecturer at North East Nursing College, Sylhet, Bangladesh.

Israth Jahan Tama, BSN, MPH, RN is working as a Lecturer at Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing, Dhaka.

Emdadul Haque, BSN, MSc, RN is working as Lecturer at North East Nursing College, Sylhet, Bangladesh.

Shamima Rahman, BSN, MSS, RN is working as Senior Staff Nurse at 300 bedded Hospital, Narayanganj, Bangladesh.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Abuhammad, S., AlAzzam, M., & Mukattash, T. (2021). The perception of nurses towards their roles during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 75(4), e13919. 10.1111/ijcp.13919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Thobaity, A., & Alshammari, F. (2020). Nurses on the front-line against the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. Dubai Medical Journal, 3(3), 87-92. 10.1159/000509361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zaman, M. S. (2020). Healthcare crisis in Bangladesh during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(4), 1357-1359. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aljazeera . (2021). Migrant workers flee Dhaka ahead of Bangladesh COVID lockdown. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/6/27/migrant-workers-flee-capital-as-bangladesh-tightens-lockdown

- Anwar, S., Nasrullah, M., & Hosen, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and Bangladesh: Challenges and how to address them. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 154. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aungsuroch, Y., Juanamasta, I. G., & Gunawan, J. (2020). Experiences of patients with coronavirus in the COVID-19 pandemic era in Indonesia. Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research, 8(3), 377-392. 10.15206/ajpor.2020.8.3.377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bala, S. D., Rony, M. K. K., Sharmi, P. D., Rahman, I., Parvin, M. R., & Akther, T. (2021). How inadequacies in the nursing field deteriorate the quality of health care in a developing nation. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 25(6), 3467-3475. [Google Scholar]

- Barello, S., & Graffigna, G. (2020). Caring for health professionals in the COVID-19 pandemic emergency: Toward an “epidemic of empathy” in healthcare. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1431. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, J., McCluskey, S., Turley, E., & King, N. (2015). The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(2), 202-222. 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, A. J., Stasa, H., Roche, M. A., Homer, C. S. E., & Duffield, C. (2014). Nursing churn and turnover in Australian hospitals: Nurses perceptions and suggestions for supportive strategies. BMC Nursing, 13(1), 1-10. 10.1186/1472-6955-13-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaka Tribune . (2020). COVID-19: Health professional shortage remains a challenge in Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.dhakatribune.com/health/coronavirus/2020/11/18/bangladesh-fighting-COVID-19-with-a-shortage-of-50-000-doctors-nurses-employees

- Gunawan, J., Aungsuroch, Y., Marzilli, C., Fisher, M. L., & Sukarna, A. (2021). A phenomenological study of the lived experience of nurses in the battle of COVID-19. Nursing Outlook, 69(4), 652-659. 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeyer, A., & Taylor, R. (2021). Strategies and resources for nurse leaders to use to lead with empathy and prudence so they understand and address sources of anxiety among nurses practising in the era of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(1-2), 298-305. 10.1111/jocn.15520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq, Z. K. (2021). Factors determining the 3rd wave of COVID-19 in Bangladesh. The Daily Star. Retrieved from https://www.thedailystar.net/health/news/factors-determining-the-3rd-wave-COVID-19-bangladesh-2118741

- Jamuna TV . (2021). Manpower crisis [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/bdjaIPh4sC8

- Lai, X., Wang, M., Qin, C., Tan, L., Ran, L., Chen, D., … Wang, S. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) infection among health care workers and implications for prevention measures in a tertiary hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Network Open, 3(5), e209666-e209666. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D., Wang, H., Yu, R., Yang, H., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Integrated infection control strategy to minimize nosocomial infection of coronavirus disease 2019 among ENT healthcare workers. The Journal of Hospital Infection, 104(4), 454-455. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M. A., Sakib, N., Gozal, D., Bhuiyan, A. K. M. I., Hossain, S., Bodrud-Doza, M., … Abdullah, A. H. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and serious psychological consequences in Bangladesh: A population-based nationwide study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 462-472. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzilli, C. (2021). A year later: Life after the Year of the Nurse. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(2), 59-61. 10.33546/bnj.1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska, L., Tang, J. W., Bahnfleth, W., Bluyssen, P. M., Boerstra, A., Buonanno, G., … Franchimon, F. (2020). How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised? Environment International, 142, 105832. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myny, D., Van Goubergen, D., Gobert, M., Vanderwee, K., Van Hecke, A., & Defloor, T. (2011). Non-direct patient care factors influencing nursing workload: A review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(10), 2109-2129. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan, L. T., Maita, D., Mortiz, D. C., Weber, R., Fritzen-Pedicini, C., Bleasdale, S. C., … Program, C. D. C. P. E. (2019). Personal protective equipment doffing practices of healthcare workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 16(8), 575-581. 10.1080/15459624.2019.1628350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuters . (2020). Bangladesh confirms its first three cases of coronavirus. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-bangladesh-idUSKBN20V0FS

- Rony, M. K. K. (2021). Diploma in Nursing or Bachelor of Science in Nursing: Contradictory issues among nurses in Bangladesh. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(1), 57-58. 10.33546/bnj.1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpfel, A. W., Sloane, D. M., & Aiken, L. H. (2012). The longer the shifts for hospital nurses, the higher the levels of burnout and patient dissatisfaction. Health Affairs, 31(11), 2501-2509. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N., Wei, L., Shi, S., Jiao, D., Song, R., Ma, L., … You, Y. (2020). A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control, 48(6), 592-598. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng, C. I., Chang, S. S., & Hsu, K. H. (2009). Emotional stability of nurses: Impact on patient safety. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(10), 2088-2096. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05072.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Daily Star . (2019). Govt Hospital: Most lacking even basic equipment. Retrieved from https://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/news/govt-hospital-most-lacking-even-basic-equipment-1764328

- Tosepu, R., Gunawan, J., Effendy, D. S., Hn, M. R., Muchtar, F., Sakka, A., & Indriastuti, D. (2021). Experience of healthcare workers in combatting COVID-19 in Indonesia: A descriptive qualitative study. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(1), 37-42. 10.33546/bnj.1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umansky, J., & Rantanen, E. (2016). Workload in nursing. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 60(1), 551-555. 10.1177/1541931213601127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worldometer . (2021). Coronavirus cases. Retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- Zhan, Y.-x., Zhao, S.-y., Yuan, J., Liu, H., Liu, Y.-f., Gui, L.-l., … Chen, J.-h. (2020). Prevalence and influencing factors on fatigue of first-line nurses combating with COVID-19 in China: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Current Medical Science, 40(4), 625-635. 10.1007/s11596-020-2226-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.