Abstract

Jellyfish are aquatic animals of the phylum Cnidaria found in seas all over the world. They are characterized by the presence of cnidocytes, cells that contain a secretory organelle, the cnidocyst, mainly used for predation and defense purposes. An adult female patient presented to our Unit of Dermatology, for a 10 days-old history of macular-erythematous lesions in her right upper limb, due to a sting by a mauve stinger Pelagia noctiluca. Dermoscopy showed a general pinkish background surmounted by numerous brown dots and lines, distributed along the surface of the skin. Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) showed the presence of multiple partially hyperreflective, highly coiled, hollow, and harpoonlike structures through the epidermis but without the barbed tubes found in a previous RCM report, likely due to a greater time elapsed between the sting and the dermatological visit. This case highlights how dermoscopy and RCM may help clinicians for the diagnosis of jellyfish stings.

Keywords: Cnidaria, Confocal microscopy, Envenomation, Mauve stinger, Reflectance confocal microscopy

Introduction

Jellyfish are the free-swimming medusa stages of aquatic animals belonging to the clade Medusozoa (phylum: Cnidaria). They are mostly found in saltwater, in seas all over the world, and are currently divided in four classes (i.e., Cubozoa – “box jellyfish,” Hydrozoa – “hydroids,” Scyphozoa – “true jellyfish,” and Staurozoa – “stalked jellyfish”), and over 4,000 species [1, 2].

Cnidarian are characterized by the presence of cnidocytes (also known as nematocytes), ectodermal-derived cells that contain a single secretory organelle called cnidocyst or nematocyst, mainly used for predation and defense purposes. Cnidocysts consist of a capsule containing a coiled threadlike tube; the external site of the cnidocyte has a trigger that, if activated (by a chemical or a mechanic stimulus), it causes expulsion of the tubule. Different types of cnidocysts exist and the tubule of the penetrant ones (named stenoteles) penetrates the target organism and ejects toxins [3, 4].

Among the jellyfishes in Mediterranean Sea, the Schypozoan mauve stinger, Pelagia noctiluca (Forsskål, 1775) is the most involved species in the cases of sting of medical importance because of its widespread distribution, ecological role, and accidental interactions with humans [5–9]. This species is characterized by a pink, mauve, or light brown color and an umbrella of 3–12 cm in diameter, with sixteen marginal lobes, eight marginal sense organs, and eight marginal tentacles [5–10]. In this species, the cnidocysts are present in the tentacles, in the oral arms, and in the upper surface of the bell [5]. The P. noctiluca venom shows mainly hemolytic and cytolytic activities; specifically, venom-induced NaCl influx followed by water and consequent cell swelling most likely underlie the hemolytic and cytolytic activity of this venom [8]. However, P. noctiluca sting is often mild (differently from the more dangerous one caused by various Cubozoa and Hydrozoa species), inducing usually only local symptoms [6–9]. In the last years, several scientific proofs highlight how noninvasive diagnostic methods, such as dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM), can play a role in the diagnosis of animal stings and bites and the relative management [6].

Case Report

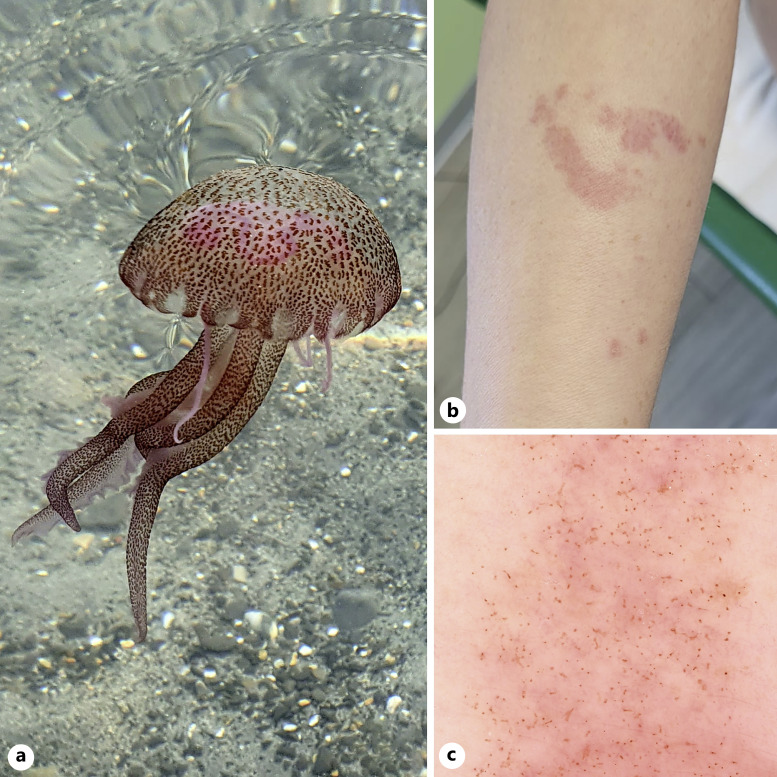

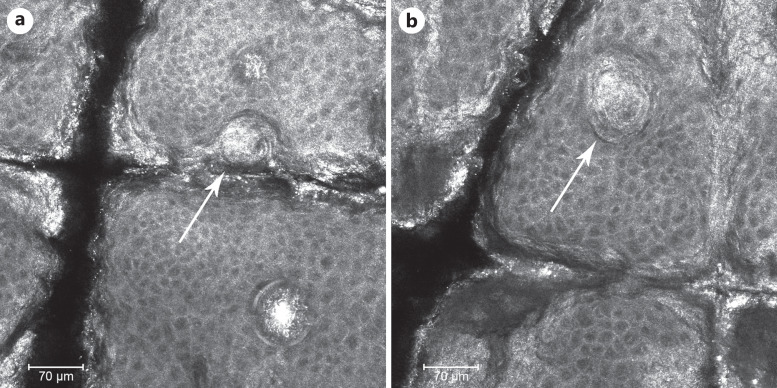

A 54-year-old Caucasian female patient presented to our Unit of Dermatology, for a 10 days-old history of macular-erythematous lesions in her right upper limb (Fig. 1b). The patient referred that the lesion arose 10 days before, while she was swimming in northwestern Italy (Liguria region), when she accidentally bumped into a jellyfish P. noctiluca (Fig. 1a). After the contact with the jellyfish, the patient experienced burning and pain; once reached the beach, she tried to wash the area with fresh water but without performing a scrub of the skin. The dermoscopy of the lesion showed a general pinkish background surmounted by numerous brown dots and lines, distributed along the surface of the skin (Fig. 1c). RCM showed the presence of multiple and diffuse partially hyperreflective, highly coiled, hollow, and harpoonlike structures through the epidermis (Fig. 2a, b). The patient was treated with momethasone furoate and urea 30% cream, twice a day for 15 days with an improvement of the cutaneous lesions and symptoms.

Fig. 1.

a Mauve stinger P. noctiluca photographed in the Ligurian Sea, northwestern Italy. b Clinical figure of the P. noctiluca sting, characterized by an erythematous plaque on the forearm. c Dermoscopy showed an erythematous pinkish background with numerous brown dots and lines, distributed along the surface of the skin.

Fig. 2.

a Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) revealed multiple hyperreflective, highly coiled, hollow, and harpoonlike structures through the epidermis (arrow), corresponding to cnidocysts. b Another RCM section (en face view of the epidermis) showed the presence of harpoonlike structures (cnidocysts) through the epidermis (arrow).

Discussion

Diagnosis of jellyfish sting is always clinical, based on the patient’s history and the appearance of the cutaneous lesions. However, doubtful cases may arise (patients who have not seen the jellyfish sting or who only notice the lesions at a later time), and in this regard, noninvasive diagnostic methods (such as dermoscopy and RCM) may help clinicians to reach a diagnosis, as well as to monitor any prescribed treatment. Regarding dermoscopy, as reported by del Pozo et al. [6] and by Di Stefani et al. [7], we found multiple brown dots (corresponding to the entry point of the nematocyst into the skin), brown dots connected by brown lines (disposed in “Chinese characters”), and some pinpoint brown crusts (deeper dermal penetration of the nematocysts), in a pinkish inflamed background, with multiple milky-red areas (Fig. 1b). Regarding RCM, our case is only the second reported in literature (the first with the certain identification of the species thanks to the photography of one of the individuals present in water at that moment), after a first report published in 2020 [6]; however, compared to Di Stefani et al. [6], in RCM analysis we found only multiple and diffuse partially hyperreflective, hollow, and harpoonlike structures, in absence of the detection of barbed tubes. Most likely, this difference is due to the fact that our patient presented to visit after 10 days (while, in the other case report, the patient presented 3 days after the puncture [6]) and therefore it is possible that over time the tubules were no longer present. This highlights how RCM makes it possible to diagnose, monitor the treatment but also to understand the time elapsed from the puncture.

Regarding the treatment, it is important to remove the patient from the water (to prevent other stinging and drowning) and stabilize [9]. Subsequently, it is important to prevent cnidocysts discharge. In this regard, a preliminary action is washing with salt water; visible tentacles can be also removed carefully with fine tweezers and the affected area should be immersed in hot water (40°C–45°C) as the jellyfish venom is thermolabile and the heat alters its structure. If required, lidocaine may reduce pain and discharge of nematocysts [11], as well as vinegar, although with conflicting opinions [4]. Astringent gels with aluminum chloride may also reduce the itching, blocking the spread of toxins. Finally, tetanus prophylaxis must also be considered in lesions with minor wounds. Concluding that, the symptoms of true jellyfish stings are usually mild and require only local treatments (with topical lidocaine or steroids).

Conclusion

This case highlights how dermoscopy and RCM may help clinicians for the diagnosis of jellyfish stings, their management, and time since the sting. Among Mediterranean jellyfish, P. noctiluca is the species most involved in cases of sting of medical importance because of its widespread distribution, ecological role, and accidental interactions with humans. Luckily, P. noctiluca stings are usually mild, requiring only local treatments. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material at https://doi.org/10.1159/000529049.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the participant for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images. Study approval statement was not required for this study in accordance with local/national guidelines.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing – original draft preparation: Giovanni Paolino and Matteo Riccardo Di Nicola. Writing – review and editing: Giovanni Paolino, Matteo Riccardo Di Nicola, Riccardo Pampena, Vittoria Giulia Bianchi, and Santo Raffaele Mercuri. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The authors have no funding sources.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Santander MD, Maronna MM, Ryan JF, Andrade S. The state of Medusozoa genomics: current evidence and future challenges. GigaScience. 2022;11:giac036. 10.1093/gigascience/giac036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Novosolov M, Yahalomi D, Chang ES, Fiala I, Cartwright P, Huchon D. The phylogenetic position of the enigmatic, Polypodium hydriforme (Cnidaria, Polypodiozoa): insights from mitochondrial genomes. Genome Biol Evol. 2022;14(8):evac112. 10.1093/gbe/evac112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slobodkin LB, Bossert PE. Cnidaria. In Ecology and classification of North American freshwater invertebrates. Academic Press; 2010. pp.125–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kass-Simon GSAA, Scappaticci Jr AA. The behavioral and developmental physiology of nematocysts. Can J Zool. 2002;80(10):1772–94. 10.1139/z02-135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mariottini GL, Giacco E, Pane L. The mauve stinger Pelagia noctiluca (Forsskål, 1775). Distribution, ecology, toxicity and epidemiology of stings. A review. Mar Drugs. 2008;6(3):496–513. 10.3390/md20080025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Di Stefani A, Cappilli S, Peris K. Jellyfish sting-in vivo imaging for diagnosis and treatment monitoring. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(3):348–50. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Del Pozo LJ, Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Escudero-Góngora MM, Saus C, Izquierdo-Herce N, et al. Dermoscopic findings of jellyfish stings caused by Pelagia noctiluca. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107(6):509–15. 10.1016/j.ad.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morabito R, Costa R, Rizzo V, Remigante A, Nofziger C, La Spada G, et al. Crude venom from nematocysts of Pelagia noctiluca (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa) elicits a sodium conductance in the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41065. 10.1038/srep41065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cunha SA, Dinis-Oliveira RJ. Raising awareness on the clinical and forensic aspects of jellyfish stings: a worldwide increasing threat. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abushaala N, Elfituri A, Abdullah AB, Shtewi H. Morphological feature of Pelagia noctiluca (forskål, 1775) (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa) in western Libyan coast, tripoli. J Pure Appl Sci. 2022;21:24–7. 10.3390/ijerph19148430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morabito R, Marino A, Dossena S, La Spada G. Nematocyst discharge in Pelagia noctiluca (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa) oral arms can be affected by lidocaine, ethanol, ammonia and acetic acid. Toxicon. 2014;83:52–8. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.