Abstract

Polymerization and depolymerization of actin play an essential role in eukaryotic cells. Actin exists in cells in both monomeric (G-actin) and filamentous (polymer, F-actin) forms. Actin binding proteins (ABPs) facilitate the transition between these two states, and their interactions with these two states of actin are critical for actin-based cellular processes. Rapid depolymerization of actin is assisted in the brain and/or other cells by its oxidation by the enzyme Mical (yielding Mox-actin), and/or by the binding of Inverted Formin 2 (INF2) – which can also accelerate filaments formation. At their stoichiometric molar ratio INF2 and actin yield the 8S complex (consisting of 4 actin monomers: 2 INF2 dimer molecules). Using biochemical and biophysical methods, we investigate the structural arrangement of actin in the 8S particles and the interaction of INF2 with actin and Mox-actin. To that end, we show 2D class averages of 8S particles obtained by negative staining electron microscopy. We also show that: (i) 8S particles can seed rapid actin assembly; (ii) Mox-actin and INF2 form 8S particles at proteins ratios similar to those of unoxidized actin; (iii) chemical crosslinkings suggest that actin monomers are in a parallel orientation in the 8S particles of both actin and Mox-actin; and (iv) INF2 accelerates the disassembly of Mox-F-actin. Our results provide better understanding of actin's arrangement in the 8S particles formed during actin depolymerization and in the early polymerization stages of both actin and Mox-actin.

Keywords: Actin, RSA, rabbit skeletal actin, Mical-oxidized actin (Mox-actin), inverted formin 2 (INF2), 8S (8 Svedberg sedimentation coefficient units), actin-INF2 8S particles, protein crosslinking, analytical ultracentrifugation, fluorescence assays

Introduction

Actin is a vital protein in eukaryotic cells and it participates in many important cellular processes. In cells, it exits as monomeric G-actin and filamentous F-actin. Actin polymerization involves a step of nucleation followed by the elongation process. Nucleation kinetics is mainly limited by the formation and stability of actin dimers and trimers [1]. This step is facilitated by several actin binding proteins (ABPs) that regulate the actin cytoskeleton [2].

Formin is one of the actin-binding proteins that can accelerate actin’s polymerization processes. Formin has two domains: formin homology 1 (FH1) and formin homology 2 (FH2). The acceleration of actin polymerization is facilitated by FH2 domains [3], which interact with the barbed ends of filaments [4]. Inverted formin 2 (INF2) is a formin isoform that can interact directly with actin through a region C-terminal to the FH2 [5]. In addition to FH2, INF2 contains also FH1, a C-terminal diaphanous auto-regulatory domain (DAD), N-terminal diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID), and a dimerization domain (DD). INF2 accelerates G-actin polymerization but can also accelerate F-actin depolymerization. INF2 depolymerizes actin filaments to 8S particles when the ratio of actin to INF2-FFC (containing the FH1, FH2, and C-terminal regions) is 2:1. It has been suggested that the 8S particle comprises 4 actin monomers and 2 INF2 dimers [6]. Upon their crosslinking with 1,4-phenylenebismaleimide (1,4-PBM), two possible actin dimers (“upper” and “lower” [7]) have been observed in SDS electrophoresis assays. It has been suggested that the “upper dimer” is in a parallel arrangement, while the “lower dimer” has anti-parallel arrangement [17]. However, the in vivo existence and dominance of parallel vs anti-parallel dimer needs further clarification.

The MICAL family of proteins, composed of invertebrate Mical and three vertebrate MICALs (MICAL-1, MICAL-2, and MICAL-3), are ABPs that oxidize actin to cause filaments disassembly [8,9,10]. The actin regulatory properties of MICALs are critical for actin filament remodeling and organization-related processes, such as axon guidance, dendritic pruning, cytokinesis, cardiac physiology, and muscle morphology [11,12,13,14]. Mox-actin is more susceptible to depolymerization due to its destabilized D-loop interactions, as compared to those of non-oxidized actin [15]. However, whether Mox-actin can form 8S particles with INF2 and the structural arrangement of actin dimers in this complex is unknown.

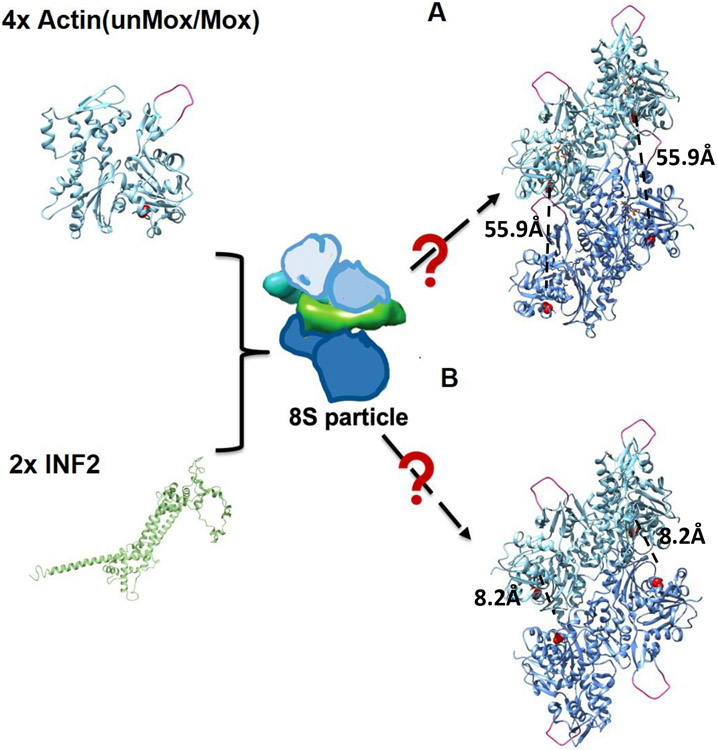

In this study we explore 8S particles formation and their structural organization for both actin and Mox-actin by utilizing biochemical, biophysical and structural biology approaches. There are two possible structural organizations of actin in the 8S particles. Actin monomers can form tetramers and retain their parallel arrangement (Figure 1), similar to that found in F-actin. The other possibility, albeit less likely, is that actin monomers are in an anti-parallel arrangement in the tetramer (Figure 1B). To check which arrangement is favored in the 8S particles, we utilized chemical crosslinkings and spectroscopic methods. Our analytical ultracentrifugation data reveal the formation of 8S particles by both actin and Mox-actin. Our spectroscopic, fluorescence, and chemical crosslinking results suggest that actin monomers are oriented in parallel in the 8S particles of both Mox-actin and actin. We also demonstrate that the 8S particles accelerate the polymerization of G-actin. Interestingly, fluorescence assays focused on the dynamics of Mox-actin reveal that INF2 accelerates the disassembly of Mox-actin at a faster rate than that of actin. In conclusion, our study: (i) shows actin organization in the 8S particles, (ii) provides novel insight into Mox-actin assembly, and (iii) demonstrates the role of 8S particles as nucleating the assembly of Mox-actin and actin. Taken together these findings pave the way for future exploration of the role of 8S particles and actin dynamics in Mical-mediated oxidation and assembly of actin.

Figure 1: Models of actin orientation in the actin:INF2 8S complex.

Model of actin monomers arrangement in the 8S complex are based on [6, 26]. The D-loop (deep pink) of actin and amino acid 374C (red) are highlighted to provide easy distinction between parallel (A) and antiparallel (B) orientations of the 4 actin subunits. The size of the particles is approximately 45nM. The distance between 374C residues in the models of parallel and anti-parallel dimers is 55.9Å [27] and 8.2Å [28], respectively. Actin structure was obtained from PBD (6DJN). Our data suggest that parallel arrangement of actins is favored in the 8S particles. INF2 is not included in A and B for image clarity.

Results

FH2 domains of formins are highly conserved

The structures of formins FMNL3 and Bni1p, which have been solved by X-ray crystallography to near atomic resolution [16, 29], share similar domain arrangements and phylogenetic lineage with INF2 (Figure 2A, B). Sequence alignment of FH2 domains of the three proteins shows their >60% similarity (Figure 2C). Structural information on INF2 was insufficient, so we obtained a homology model of INF2 and compared it to the available two formin structures (Figure 2D). The superposition of the three structures shows their similar domain arrangements and little deviation (the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between INF2 and BN1P (1Y64) is 1.134 Å, between INF2 and FMNL3 (4EAH) it is 1.2 Å. The RMSD between all 3 structures is 1.1 Å), suggesting their similar interactions with actin.

Figure 2: FH2 domains of formins are highly conserved.

(A) Schematic representation of domains arrangement in formins: INF2, FMNL3 and Bni1P. (B) Multiple sequences alignment of the FH2 domain of the three proteins using MUSCLE [23]. Residues with 90% identity are shown in blue in (C). (C) Phylogenetic tree (Neighbor-joining) of FH2 domains and their relationship to each other. (D) The isoforms of FH2 domain are illustrated structurally in (i), (ii), and (iii); (iv) shows the superimposed FH2 domains. The structural models of Bni1p (1Y64) and FMNL3 (4EAH) were obtained from PDB. The structural model of INF2 was generated by homology modelling using PHYRE-2 [24]. To confirm the model generated by Phyre2 we used Swiss Model [33] and DTU server [34] to generate additional models (data not shown) and those were similar to the one generated by PHYRE-2.

Electron microscopy data support the formation of 8S particles

Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) studies have shown that Inverted formins form the 8S particles when combined at a 1:2 molar ratio with actin [6]. We used negative stain electron microscopy to obtain images of these particles (Figure 3A). Representative images of micrographs and the picked particles are shown in Figure 3B. We then performed image analysis using EMAN2 and obtained 2D class averages of the 8S particles (Figure 3C). A 3D model generated from the 2D classes (Figure 3D) reveals a globular shape of these 8S particles .Additionally, the 3D model projections matches well with the 2D class averages which were used to for model generation (Figure 3E). This is a first low-resolution imaging of the 8S particles.

Figure 3: Negative stain electron microscopy shows the 8S particles.

(A) A representative negative stain image showing the 8S particles. The boxed inset is shown in an enlarged form on the right side. (B) Representative images of selected particles. (C) 2D class averages of 8S particles generated by EMAN2 [22]. The approximate size of the particles is ~40nM. (D) A 3D model generated from the 2D class averages shown in different orientations along the X,Y axis. (E) Examples of class averages matching the model projections.

8S particles aid in rapid assembly of actin filaments

A critical role of 8S particles in actin polymerization is in overcoming its nucleation barrier. 8S particles were formed by incubating G-actin, INF2, and Latrunculin A (LatA) at a 2:1:4 RSA:INF2:LatA molar ratio, at room temperature, to ensure that actin was in its monomeric form when interacting with INF2. Actin was polymerized at a critical concentration of 1μM, at which the rate of its assembly is very slow because of the nucleation barrier. When the 8S particles were added to this actin as polymerization seeds, they accounted for 5% of the final actin concentration. The presence of such seeds allowed actin monomers to bypass the nucleation barrier and polymerize rapidly (Figure 4A, B). This data confirms that the 8S particles are crucial for surpassing the nucleation barrier, and that their presence (in vitro) as seeds can accelerate actin polymerization.

Figure 4: The 8S particles aid in a rapid assembly of actin filaments.

(A) 10% pyrene labeled actin and Mox-actin were polymerized at a critical concentration of 1 μM, with and without the 8S seeds, n=3. 8S seeds accounted for 5% of total actin.

Key, 1: Buffer only; 2: Actin+8S seeds; 3: Actin (no 8S seeds added); 4: 8S seeds; 5: Mox-actin (no 8S seeds added); 6: Mox-actin+8S seeds. (B) EM images of actin samples collected from A after completion of the assay, i) Actin + 8S seeds, ii) 8S seeds alone. Scale bar represents 100nM.

Fluorescence excimer assay does not support antiparallel actin arrangement in the 8S particles

Pyrene excimer fluorescence is used to observe structural changes in actin dimers by revealing the proximity of its pyrene-tagged cysteine 374 residues (Figure 5A). The polymerization of G-actin is induced by the addition of polymerizing salts in G-buffer. If G-actin assembles as antiparallel dimers we should observe excimer formation in the form of high fluorescence values [31]. However, we did not detect any excimer, indicating the absence of antiparallel organization of actin in the dimer (Figure 5B).

Figure 5: Actin protomers do not have antiparallel arrangement in the 8S particles.

(A) A model of actin antiparallel tetramer shows the locations of Cys374 residues (red) and the D-loop (deep pink). (B) Fluorescence assay to detect/measure excimer formation between pyrene labeled C374 residues during 8S particles formation, n=3. Key, 1: Actin; 2: Actin+INF2. No excimer is detected. (C) SDS gel showing products of actin crosslinkings using Cu2+, MTS1, and MTS8. Lane 1-4 are for samples without INF2, and crosslinked by Cu2+ (lane 2), MTS1 (lane 3), and MTS8 (lane 4). Lane 1 is for the actin only control. Lanes 5-8 are for samples with INF2 added to actin and then crosslinked by copper (lane 6), MTS1 (lane 7), and MTS8 (lane 8). Lane 5 is for actin with INF2 without a crosslinking agent (control), n=3. (D) Quantification of actin bands in MTS crosslinking gels (in C). The blue bars represent samples without INF2, the orange bars represent samples with INF2. No change in the amount of uncrosslinked actin is detected. Lane numbers are the same as in C. Stain intensity is in arbitrary units.

Cys374-Cys374 chemical crosslinkings do not occur in the 8S particles

To investigate the nature of actin dimer in the 8S particles and to map the interactions between specific actin residues in them, chemical cross-linkings were carried out. To this end, Cys374 in the C-terminus of actin was targeted for the crosslinking. Cys374-Cys374 crosslinking experiments were carried out to check whether actins in the 8S structure were anti-parallel. In such a case the two Cys residues could be linked with various length span cross-linkers: Cu (oxidation to form a disulfide bond), 1,1-Methanediyl Bismethanethiosulfonate (MTS1, ~6 Angstrom) and 1,8-Octadiyl Bismethanethiosulfonate (MTS8, ~13 Angstrom). Previous studies have shown that a cross-linked anti-parallel dimer, also known as a “lower dimer”, migrates around 75kD on SDS-PAGE gels [7]. No crosslinked anti-parallel lower dimer appeared in our assays when the 8S particles were crosslinked with Cu, MTS1, and MTS8 (Figure 5C). Moreover, the intensity of the actin monomer band in the crosslinked actin and in the 8S particles was close to its intensity in uncrosslinked actin and in 8S particles (Figure 5D). This indicated the absence of any chemical crosslinking between two Cys374 residues. Thus, our crosslinking and fluorescence assays demonstrate that these two Cys residues are distant, do not come into close proximity, and thus are not in an antiparallel conformation.

Mical-oxidized actin (Mox-actin) can form the 8S particles

Next, we sought to determine whether actin oxidized by the F-actin disassembly enzyme Mical (i.e., Mox-actin), could form 8S particles. We first confirmed by sedimentation velocity experiments that a 2:1 molar ratio of (unmodified) actin:INF2-FFC resulted predominantly in 8S particles (Figure 6Ai). Thus, we also used a 2:1 ratio of Mox-actin:INF2-FFC in sedimentation velocity experiments. We found that Mox-actin also formed 8S particles (Figure 6Aii).

Figure 6: Features of Mical-oxidized actin (Mox-actin).

(A) Analytical ultracentrifugation data showing the formation of 8S complex for (i) un-oxidixed actin and (ii) Mical-oxidized actin. (B) Crosslinking assays using copper, MTS1 and MTS8 analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Lanes 1-4 are Mox-actin samples without INF2 and crosslinked by copper (lane 2), MTS1 (lane 3), and MTS8 (lane 4). Lane 1 is Mox-actin alone. Lanes 5-8 are Mox-actin with INF2 and crosslinked by copper (lane 6), MTS1 (lane 7), and MTS8 (lane 8). Lane 5 is the Mox-actin with INF2 control (no crosslinking agent), n=3. (C) Analysis of MTS crosslinking gels. Blue bars are for samples without INF2, orange bars represent samples with INF2. Lane numbers are the same as in B. (D) Pyrene fluorescence assays to test for excimer formation, n=3. No excimer is detected. The two superimposed fluorescence intensity lines (gray and orange) show no effect of INF2 on pyrenyl actin fluorescence. Key, 1: Mox-actin; 2: Mox-actin+INF2. (E) Fluorescence assays of F-actin and Mox-F-actin and kinetic measurements of their depolymerization induced by the addition of 2 μM INF2 to actin that was polymerized overnight in polymerizing salts. Purple arrow indicates the addition of buffer and green arrow indicates the addition of INF2 (n=3). Key, 1: Actin; 2: Actin+INF2; 3: Mox-actin; 4: Mox-actin+INF2.

Similar properties of 8S particles of actin and Mox-actin

Similar to MTS crosslinkings carried out with unmodified actin, different cross-linkers (Cu, MTS1, and MTS8) were used to test the possibility of antiparallel Cys374-Cys374 arrangement of actin in Mox-actin 8S particles. No cross-linked anti-parallel (lower) dimer was detected in these reactions (Figure 6B). Also, the intensity of Mox-actin monomer on SDS gels (Figures 6B and 6C) was unchanged by cross-linking reactions with the 8S particles (Figure 6C).

We also tested for a transient presence of antiparallel actin dimer confirmation in 8S particles under conditions of actin filaments assembly. This was done by using Cys374 pyrene labeled actin in the 8S particles and checking for any excimer formation during actin polymerization. As shown in Figure 6D there was no fluorescence increase (excimer formation) in the reactions containing Mox-actin and INF2 compared to Mox-actin alone.

Mox-actin behaves similarly to wild type actin when provided as an 8S seed particle, such that Mox-actin elongation is accelerated in the presence of these seeds. Notably, our 8S particles were formed by incubating monomeric Mox-actin, INF2, and Latrunculin A at a 2:1:4 Mox-actin:INF2:LatA molar ratio (at room temperature for thirty minutes) to ensure that Mox-actin was retained in its monomeric form when interacting with INF2 to form the 8S particles. Mox-actin was polymerized at a critical concentration of 1 μM, and the presence of 8S seeds allowed actin monomers to bypass the nucleation barrier and polymerize rapidly (Figure 4A). Clearly, the action of small amounts of 8S particles as seeds demonstrates their ability to induce actin assembly.

Mox-actin filaments disassemble more rapidly in the presence of INF2 than actin filaments

Fluorescence assays of actin filaments depolymerization (Figures 6E and S1) show that INF2 can interact with Mox-actin filaments and depolymerize them much faster than non-oxidized actin filaments. More specifically, in these experiments the polymerization of 4 μM pyrene-labeled G-actin and 4 μM pyrene-labeled Mox-actin was monitored, and upon its completion INF2 was added to the reaction mixture. The observed fluorescence changes documented that the rate of Mox-actin filaments formation was considerably slower than that of actin filaments (Figure S1). With that, the disassembly of Mox-actin filaments was much faster than that of actin filaments (Figures 6E and S1). Pelleting assays have a limited value here since Mox-actin alone does not yield filaments that can be pelleted (Figure S2) under our conditions. Such pelleting experiments document well the binding of INF2 to F-actin and reveal only a small amount of INF2 and Mox-F-actin present in the pellets (Figure S2).

Discussion

Actin monomers are arranged in parallel in the 8S complexes of actin and Mox-actin with INF2

Interactions of INF2 with actin are important for cellular control and regulation of actin filaments structure and function. Consequently, these interactions have been studied quite extensively and we gained good understanding of the role of INF2 in the nucleation and severing of actin filaments. [5, 6, 19] The area that received less attention is the interaction of INF2 with monomeric G-actin, despite its constant presence in the cells. Thus, it has been important to look in some detail at that interaction. This work addresses that task. Because INF2 has two binding sites for actin it has been expected that it would form a complex with two actin monomers, leading to a question of what is the form of the resulting actin dimer in a complex with INF2.

An antiparallel actin dimer has been regarded as a key intermediate during the nucleation stage of actin polymerization [30, 31]. While it was previously shown that polylysine arrests actin in the antiparallel dimer conformation, whether INF2 exhibits similar properties was unknown [17]. In this study, we tested for a hypothetical antiparallel actin arrangement in the actin-INF2 8S complex.

Our polymerization results (Figure 4) showed that the 8S particles aid in the rapid assembly of actin filaments. This result suggested a likely parallel arrangement of actins in the 8S complex since such an arrangement is more favorable to elongation of actin filaments than the anti-parallel one. In a test of actin arrangement in the 8S complex, an excimer assay was conducted using Cys-374 pyrene labeled actin, but no excimer was found in this complex (Figure 5B). This result is consistent with a parallel arrangement of actin monomers in the model of 8S particles (Figure 1A) and inconsistent with their anti-parallel arrangement. In the anti-parallel 8S particles model structure the distance between two 374C residues would have been 8.2Å (as taken from the previously solved structure of anti-parallel actin dimer [28]). Thus, in the case of antiparallel arrangement of actin monomers (Figure 1B), with pyrene labels positioned within 16Å from each other, an excimer would have been detected. To support the conclusion on the absence of antiparallel actin arrangement in the 8S complex, crosslinking of actin Cys374 residues was attempted with reagents of different length span, but none was observed (Figure 5C, D). This confirms the result of our excimer experiments that actin monomers are not arranged in an antiparallel fashion in the 8S particles. A parallel arrangement of actins in these particles is consistent with their ability to nucleate actin filaments assembly and to be incorporated in them.

Little was known about the interaction of Mox-actin with INF2, and whether Mox-actin can form the 8S complex was unknown. In this study, the formation of Mox-actin:INF2 8S complex was confirmed by our sedimentation velocity experiments (Figure 6A).

In analogy to the actin-INF2 complex, Mox-actin-INF2 also did not show any excimer formation when using pyrene labeled actin. This result, and the cross-linking tests carried out in the same way as with the actin-INF2 8S complex, confirmed that Mox-actin monomers, similar to (unoxidized) actin, were arranged in a parallel way in the 8S particles (Figure 1A). Thus, the structural arrangement of the 8S particles of actin-INF2 and Mox-actin-INF2 is the same, or very similar.

Rapid disassembly of Mox-actin filaments by INF2

MICALs and their ability to oxidize and disassemble F-actin have emerged as an important means to disassemble F-actin in cells [11,12,13,14]. MICALs trigger disassembly of F-actin and also generate Mox-actin that has a reduced ability to polymerize [8,9,10,18]. We now add to these results by uncovering the rapid disassembly of Mox-actin filaments by INF2 (Figure 6E). In particular, under identical conditions in the presence of INF2, Mox-actin filaments disassemble much faster than actin filaments. Interestingly, work in vivo also supports a role of INF2-type formins in working with Mical – such that regulation of INF levels in vivo generates defects that resemble similar changes to Mical [19]. Our results therefore also add to our recent observation that Mox-F-actin is disassembled by profilin (and at lower profilin concentrations than F-actin) [19]. Thus, in conclusion, these results also add to an important emerging theme that Mical and its interaction with other ABPs (e.g., [18,19]) target actin filaments for rapid disassembly.

Experimental Procedures

DNA constructs

The INF2-(FH1-FH2-C) DNA construct was provided by Dr. Higgs lab [5].

Protein preparation and purification

Rosetta 2 DE3 Escherichia coli were used for the expression of INF2-FFC. After breaking the cells and getting the supernatant, a GST (glutathione S-transferase) column was first used to purify INF2. ProTEV was used after that for cleavage of GST. A gel filtration column was then used to purify INF2. The purified protein was dialyzed vs Hepes buffer (10mM Hepes pH=7.4, 50mM KCl, 1mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA) and was stored at −81°C for further use. Rabbit skeletal muscle actin (RSA) was purified from acetone powder of muscles [20] and Mical oxidized actin (Mox-Actin) was generated as described by [18] N-(1-pyrene)-maleimide was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) or AnaSpec Inc. (San Jose, CA). RSA labeling with pyrene maleimide was carried out in thiol-free GB2 supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM KCl, at 1:2.5 (actin:dye) molar ratio, for 1 h on ice. The resulting pyrene-labeled F-actin was pelleted, depolymerized (GB2), and gel-filtered on Superdex S200 16/60 column [32]. Mical-oxidized RSA (Mox-actin) was prepared and purified according to the published protocol [18].

Negative stain electron microscopy

Protein samples were applied to 400-mesh carbon-coated copper grids coated with formvar films (EM Sciences). After 60 seconds of adsorption, the grids were blotted dry and treated with 1% uranyl acetate for 45 seconds. The grids were examined in a Technai T12 electron microscope operated at 120 kV. The collected images were analyzed using IMAGE J software [21]. Image processing and 2D class averages were done with EMAN2 [22]. Around 5397 particles that were picked manually were used to generate 2D class averages with EMAN2, and each class average consisted of >200 particle images. Individual classes were evaluated, and an initial 3D model was generated from the relevant class averages. Each model was then evaluated by inspection of the class vs projection images to select the final model.

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Stoichiometric mixtures of unlabeled G-actin, Mox G-actin and INF2 that are known to form 8S particles were mixed under polymerization conditions. Sedimentation velocity experiments were carried out at 20°C in a Beckman Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge equipped with a photoelectric scanning system. Sedimentation boundaries of actin recorded at the beginning of the run, at 3000 rpm, provided the information on a total 8S concentration in the solution. The plateau regions of the boundaries were recorded at the top run speeds (45,000 rpm). Sedimentation coefficients distributions were determined from g(s) plots using the Beckman Origin-based software (Version 3.01).

Fluorescence excimer assays

The time course of pyrene-labeled G-actin polymerization was recorded using fluorescence signal detection in a TECAN instrument (with 365 nm excitation and 385 nm emission). The polymerization of 4μM pyrene-labeled G-actin was induced with the addition of polymerizing salts. Excimer formation during actin polymerization was monitored using 360 nm excitation and 407 nm emission wavelengths in the TECAN instrument [31].

Fluorescence based actin nucleation assay

To stabilize the monomeric form of actin prior to filaments assembly, 2μM actin was mixed with Latrunculin A (at 1:2 molar ratio of G-actin:LatA) (Sigma). After addition of MgCl2 (to replace Ca in G-actin) and a 3 min incubation period, the F-actin buffer was added as a polymerization salt and INF2 was added to the reaction well at the molar ratio of 2:4 (INF2:actin). 8S complex seeds were formed by incubating G-actin, INF2, and Latrunculin A (LatA) at a 2:1:4 RSA:INF2:LatA molar ratio, in the dark, for 30 minutes. The seeds were diluted prior to their addition to yield 5% of 1μM pyrene-labeled G-actin. This procedure was repeated with Mox-actin [18,23].

Crosslinking experiments

Cys374-Cys374 crosslinking: G-actin was dialyzed overnight vs buffer containing 10mM Hepes pH=7.4, 50mM KCl, 1mM MgCl2, and 1mM EGTA. After the dialysis, actin (at a concentration of 3 μM) was incubated for 20 minutes with 1X KMEH and 1.5M INF2 to form 8S particles. After the 8S particles were formed, crosslinkings with were done for 30 minutes, with Cu (oxidation to form a disulfide bond), MTS1 (crosslinking distance of ~6 Å) and MTS8 (crosslinking distance of ~13 Å). These reactions were stopped by using 2-mercaptoethanol. Samples were then analyzed by SDS PAGE and the intensity of SDS gel bands was quantified by ImageJ [21]. All crosslinking regents were obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals Inc., North York (Ontario, Canada).

High-speed pelleting assays

For high-speed pelleting assays, Mg-ATP F-actin (10μM) was prepared by incubating Ca-ATP-G-actin for 3 min in a polymerization ME exchange buffer (0.05mM MgCl2 and 0.2mM ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N, N, N’, N’-tetraacetic acid [EGTA]). Actin stock was then diluted to 2μM with 1xKMEH 7.4 buffer (50mM KCl, 1mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA, 10mM HEPES, 0.2mM ATP, 1mM DTT, pH 7.4) in the presence of 1μM INF2, followed by its incubation at room temperature for 1 hour. These reactions samples were then subjected to high-speed centrifugation (TLA100 rotor, 80,000 rpm, 4°C, 20 min). High speed supernatants and pellets were analyzed by SDS–PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie Blue and quantified with ImageJ.

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments were repeated at least three separate independent times. At least three independent protein purifications and multiple independent actin biochemical experiments were performed with similar results. Figure legends list the sample size for each experiment. To the best of our knowledge the statistical tests are justified as appropriate. No cell lines were used in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wong Hoi Hui and Dr. Peng Ge from the EM facility for their assistance with electron microscopy experiments. Supported by grants from the NIH (NS073968) and the Welch Foundation (I-1749) to JRT and NIH (GM077190) to ER.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

References

- 1.Sept D, Elcock AH, and McCammon JA (1999) Computer simulations of actin polymerization can explain the barbed-pointed end asymmetry. J. Mol. Biol 294, 1181–1189, doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotty JD, and Bear JE (2014) Competition and collaboration between different actin assembly pathways allows for homeostatic control of the actin cytoskeleton. Bioarchitecture. 5, 27–34, doi: 10.1080/19490992.2015.1090670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker JL, Courtemanche N, Parton DL, Mccullagh M, Pollard TD and Voth GA (2015). Actin Filament Nucleation is Influenced by Electrostatic Interactions with the Bni1p Formin FH2 Domain. Biophysical Journal 108, issue 2, supplement 1, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moseley JB, Sagot I, Manning AL, Xu Y, Eck MJ, Pellman D, and Goode BL (2004) A Conserved Mechanism for Bni1- and mDia1-induced Actin Assembly and Dual Regulation of Bni1 by Bud6 and Profilin. MBoC. 15, 896–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhabra Ekta Seth and Higgs Henry N.. (2006) INF2 is a WASP Homology 2 Motif-containing Formin That Severs Actin Filaments and Accelerates Both Polymerization and Depolymerization. J Biol Chem 281(36), 26754–67, DOI 10.1074/jbc.M604666200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurel PS, A M, Guo B, Shu R, Mierke DF and Higgs HN (2015). Assembly and Turnover of Short Actin Filaments by the Formin INF2 and Profilin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 290, 22494–22506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silván U, Boiteux C, Sütterlin R, Schroeder U, Mannherz HG, Jockusch BM, Bernèche S, Aebi U, and Schoenenberger C-A (2012) An antiparallel actin dimer is associated with the endocytic pathway in mammalian cells. Journal of Structural Biology 177, 70–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung RJ, Pak CW, and Terman JR (2011). Direct redox regulation of F-actin assembly and disassembly by Mical. Science 334, 1710–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hung RJ, Yazdani U, Yoon J, Wu H, Yang T, Gupta N, Huang Z, van Berkel WJ, and Terman JR (2010). Mical links semaphorins to F-actin disassembly. Nature 463, 823–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu H, Yesilyurt HG, Yoon J, and Terman JR (2018). The MICALs are a Family of F-actin Dismantling Oxidoreductases Conserved from Drosophila to Humans. Sci Rep 8, 937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alto LT, and Terman JR (2018). MICALs. Curr Biol 28, R538–R541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fremont S, Romet-Lemonne G, Houdusse A, and Echard A (2017). Emerging roles of MICAL family proteins - from actin oxidation to membrane trafficking during cytokinesis. J Cell Sci 130, 1509–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manta B, and Gladyshev VN (2017). Regulated methionine oxidation by monooxygenases. Free Radic Biol Med 109, 141–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanoni MA (2017). Structure-function studies of MICAL, the unusual multidomain flavoenzyme involved in actin cytoskeleton dynamics. Arch Biochem Biophys 632, 118–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grintsevich EE, Ge P, Sawaya MR, Yesilyurt HG, Terman JR, Zhou ZH and Reisler E (2017). Catastrophic disassembly of actin filaments via Mical-mediated oxidation. Nature communications 8(1):2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson ME, Heimsath EG, Gauvin TJ, Higgs HN, and Kull FJ. (2013) FMNL3 FH2-actin structure gives insight into formin-mediated actin nucleation and elongation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 20(1):111–118. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bubb MR, Govindasamy L, Yarmola EG, Vorobiev SM, Almo SC, Somasundaram T, Chapman MS, Agbandje-McKenna M, and McKenna R. (2002) Polylysine induces an antiparallel actin dimer that nucleates filament assembly: crystal structure at 3.5-A resolution. J Biol Chem. 277(23):20999–1006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201371200. Epub 2002 Apr 3. Erratum in: J Biol Chem 2002 Sep 6;277(36):33529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grintsevich EE, Yesilyurt HG, Rich SK, Hung RJ, Terman JR, and Reisler E (2016). F-actin dismantling through a redox-driven synergy between Mical and cofilin. Nat Cell Biol 18, 876–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grintsevich EE, Giassddin A, Ginosyan AA, Wu H, Rich SK, Reisler E, Terman JR (2021) Profilin and Mical combine to impair F-actin assembly and promote disassembly and remodeling. Nature Commun. 2021 Sep 20;12(1):5542. Doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25781-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spudich JA, and Watt S. (1971) The regulation of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction. I. Biochemical studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin and the proteolytic fragments of myosin. J Biol Chem. 246(15):4866–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, and Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9, 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang G, Peng L, Baldwin PR, Mann DS, Jiang W, Rees I and Ludtke SJ (2007). EMAN2: an extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. Journal of structural biology. 157(1), pp. 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wioland H, Fremont S, Guichard B, Echard A, Jegou A, and Romet-Lemonne G (2021). Actin filament oxidation by MICAL1 suppresses protections from cofilin-induced disassembly. Rep 22, e50965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edgar RC. (2004). MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. Aug 19; 5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelley L, Mezulis S, Yates C et al. (2015). The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10, 845–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gurel PS, Ge P, Grintsevich EE, Shu R, Blanchoin L, Zhou ZH, Reisler E, Higgs HN. (2014). INF2-mediated severing through actin filament encirclement and disruption.. 2014 Jan 20;24(2):156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.018. Epub 2014 Jan 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reutzel R, Yoshioka C, Govindasamy L, Yarmola EG, Agbandje-McKenna M, Bubb MR, McKenna R. (2004). Actin crystal dynamics: structural implications for F-actin nucleation, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Merino F, Pospich S, Funk J, Wagner T, Küllmer F, Arndt HD, Bieling P, Raunser S. (2018). Structural transitions of F-actin upon ATP hydrolysis at near-atomic resolution revealed by cryo-EM. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018 Jun;25(6):528–537. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0074-0. Epub 2018 Jun 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reutzel R, Yoshioka C, Govindasamy L, Yarmola EG, Agbandje-McKenna M, Bubb MR, McKenna R. (2004). Actin crystal dynamics: structural implications for F-actin nucleation, polymerization, and branching mediated by the anti-parallel dimer. J Struct Biol. 2004 Jun;146(3):291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otomo T, Tomchick DR, Otomo C, Panchal SC, Machius M, Rosen MK. (2005). Structural basis of actin filament nucleation and processive capping by a formin homology 2 domain.. Nature, 2005 Feb 3;433(7025):488–94. Doi: 10.1038/nature03251. Epub 2005 Jan 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinmetz MO, Goldie KN, Aebi U. (1997). A correlative analysis of actin filament assembly, structure, and dynamics.. 1997;138(3):559–574. Doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grintsevich EE, Phillips M, Pavlov D, Phan M, Reisler E, Muhlrad A. (2010). Antiparallel dimer and actin assembly. Biochemistry. 2010;49(18):3919–3927. Doi: 10.1021/bi1002663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kouyama T, Mihashi K. (1981). Fluorimetry study of N-(1-pyrenyl)iodoacetamide-labelled F-actin. Local structural change of actin protomer both on polymerization and on binding of heavy meromyosin. Eur J Biochem. 1981;114(1):33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R, Heer FT, de Beer TAP, Rempfer C, Bordoli L, Lepore R, Schwede T (2018). SWISS-MODEL: homology modeling of protein structures and complexes.. 2018;46, W296–W303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Lund O, Petersen TN (2010). CPHmodels-3.0 - Remote homology modeling using structure guided sequence profiles. Nucleic Acids Research, 2010, Vol. 38, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.