Abstract

Introduction:

Video-based review of surgical procedures has proven to be useful in training by enabling efficiency in the qualitative assessment of surgical skill and intraoperative decision-making. Current video segmentation protocols focus largely on procedural steps. Although some operations are more complex than others, many of the steps in any given procedure involve an intricate choreography of basic maneuvers such as suturing, knot tying, and cutting. The use of these maneuvers at certain procedural steps can convey information that aids in the assessment of the complexity of the procedure, surgical preference, and skill. Our study aims to develop and evaluate an algorithm to identify these maneuvers.

Methods:

A standard deep learning architecture was used to differentiate between suture throws, knot ties, and suture cutting on a data set comprised of videos from practicing clinicians (N = 52) who participated in a simulated enterotomy repair. Perception of the added value to traditional artificial intelligence segmentation was explored by qualitatively examining the utility of identifying maneuvers in a subset of steps for an open colon resection.

Results:

An accuracy of 84% was reached in differentiating maneuvers. The precision in detecting the basic maneuvers was 87.9%, 60%, and 90.9% for suture throws, knot ties, and suture cutting, respectively. The qualitative concept mapping confirmed realistic scenarios that could benefit from basic maneuver identification.

Conclusions:

Basic maneuvers can indicate error management activity or safety measures and allow for the assessment of skill. Our deep learning algorithm identified basic maneuvers with reasonable accuracy. Such models can aid in artificial intelligence-assisted video review by providing additional information that can complement traditional video segmentation protocols.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Computer vision, Surgical data science, Video-based assessment

Introduction

Video-based review

Video-based review has proven to be a scalable and efficient way in assessing surgeon skill, providing feedback, and exploring correlation with patient outcomes.1 The use of video-based review has been shown to improve the learning curve for surgeons and reduce patient harm.2 The American Board of Surgery, the national certifying body for general surgeons2 and related specialists, launched a video-based assessment pilot program where 150 surgeons were recruited to upload videos of their own operations and review videos uploaded by their peers. Using existing video review platforms, reviewers are able to remotely and asynchronously review the videos and provide feedback to their fellow surgeons. This program is motivated by the desire to explore the feasibility of video-based assessment as a mode of formative skill assessment and establishing a platform for coaching.3

Segmentation

Given that some portions of a video may be more relevant to reviewers than others, focusing on key operative moments can increase efficiency in video-based review. In a study by Dath et al.,4 it was shown that authors were able to review videos 80% faster when they were allowed to scrub through the video at their discretion. Recently developed autosegmentation tools have been adopted to increase the productivity of reviewers by dividing a given video according to procedural steps.5 For example, in a study by Jin et al.,6 the authors describe a deep learning method to segment a laparoscopic cholecystectomy video, based on seven procedural steps: preparation, calot triangle dissection, clipping and cutting, gallbladder dissection, gallbladder packaging, cleaning and coagulation, and gallbladder retraction. Such segmentation tools can make video review even more efficient. In a study by Pugh et al.,7 the authors note that artificial intelligence (AI)-segmented videos were reviewed at a rate of 50 videos an hour.

Motivation for detection of basic maneuvers

Segmentation of videos according to procedural steps improves efficiency; however, it has its limitations. Some operations are more complex than others due to both patient and surgeon factors, including complications that arise during the course of surgery that may require surgeons to deviate from normal protocol.8 Hence, portions of the video may not fall under any one procedural step, and it is of benefit to the reviewer to have the ability to directly skip to the time points where these complications occur without having to search under a given procedural step. Given that basic maneuvers such as suture throwing, tying, and cutting at certain contexts can indicate complications, the added feature of basic maneuver detection provides an extra layer of information and can aid in evaluating a surgeon’s approach to critical decision-making points in a procedure. Moreover, basic maneuver detection can introduce additional tracking of safety measures such as reinforcement of tissue through suturing. These points may quickly reveal the surgeon’s advanced technical decision-making ability and understanding of the anatomy. In the correct context, these critical points provide additional information to reviewers about the overall skill of the surgeon and the complexity of the case. In a study by Mohamadipanah et al.,9 the authors show that performance measured while placing the initial anchoring suture in a simulated laparoscopic ventral hernia repair is a good indicator of overall performance.

Summary

Video segmentation algorithms make video reviewers more productive by allowing them to easily navigate portions of the video that are relevant to skill assessment. However, these tools focus heavily on procedural steps based on ideal protocols. Because surgical procedures may be complicated by the various surgeon and patient factors, the surgeon may deviate from this protocol. Information surrounding such deviations, such as basic maneuvers, is useful to assess skill.

Hypothesis

In this work, we hypothesized that a standard AI methodology could be trained and tested to identify basic maneuvers in videos with reasonable accuracy.

Methods

Settings and participants

Video data were collected at the 2019 American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress in San Francisco, where attending and retired surgeons were asked to perform a simulated bowel enterotomy repair.10 Participants were presented with a pre-injured segment of porcine bowel and were not privy to the locations of the injuries. The surgeons ran the bowel and repaired any injuries they were able to locate. This study was approved by the Stanford Internal Review Board.

Data

Video data were collected from a close-up camera as well as an overhead camera. The feed from the close-up camera was used in our experiment. The videos were captured at approximately 30 frames per sec at 1080 × 1920 resolution.

Each video was reviewed and annotated by the research team. Annotations included the start and stop time for every suture throw, knot tie, and thread cut performed by the participants during the course of the enterotomy repair. The start of the suture throw was defined as the point at which the participant first touched the suture needle to the bowel tissue with the intent to pass. The endpoint was marked when the suture needle passed through the tissue, and participants stopped their motion after the final pull of the thread tail. Similarly, the start point of the knot tie was noted when the participant grasped both the tails of the suture with the intent to perform a knot tie. The endpoint was noted when the thread was pulled taut. Finally, the thread cut start point was defined as the point at which the blades are open and moving toward the suture, and the endpoint is noted when the blades are closed and the thread is cut.

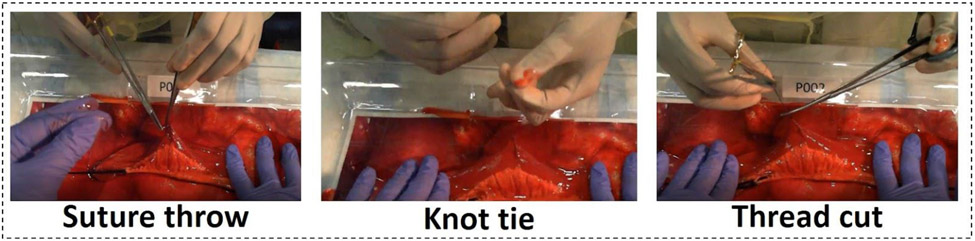

The clips corresponding to the basic maneuvers were extracted from the videos. Each of these clips was further sliced into 2- to 3-s clips and scaled to a 250 × 250 resolution. This was done to increase the number of data points available for training and testing. During the training process, the video clips were further downsampled to choose three equally spaced frames. A window stride of one was used over each clip. Hence, each input is comprised of three frames representing a 2-s time window. Figure 1 shows a representative image for each of the three classes.

Figure 1:

Figure shows The basic maneuvers of suture throw, knot tie and thread cut being performed by a participant performing a simulated enterotomy repair at the ACS 2019 conference

Model architecture and hardware

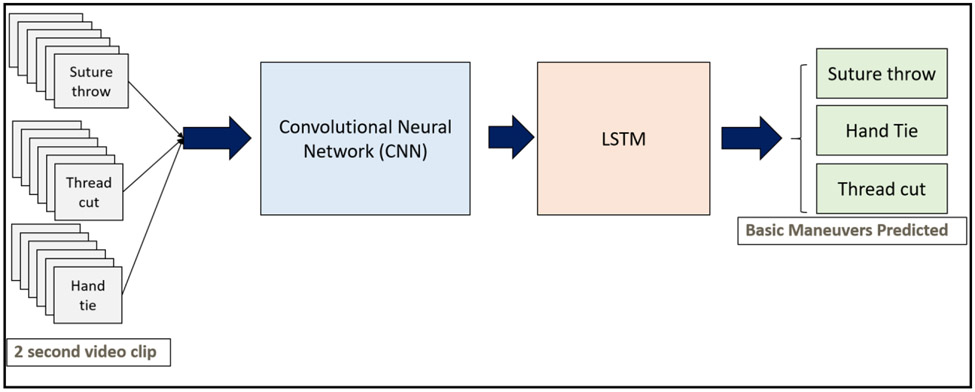

The deep learning model that was chosen included sequential architecture consisting of a ResNet-5011 and a Long-Short Term Memory Unit (LSTM).12 The ResNet-50 is a type of convolutional neural network that is able to process images and extract visual information or features from them to perform various classification tasks.11 The LSTM units are generally used to capture information in sequences of inputs. They are used in natural language processing applications and activity recognition applications.12 This architecture was adopted from the work described in a study by Jin et al.6 for phase segmentation of laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedures.

We conjectured that the information needed to distinguish the maneuvers is present at two levels: (1) Intraframe information: Information contained in the individual frames relating to the type of instruments used (needle driver, needle, scissors), (2) Interframe information: Information contained in the hand motion of the surgeon as they perform the maneuver (hand twisting motion for needle driving versus clasping motion for suture cutting). The dual-model architecture is strategically chosen to extract both intraframe and interframe information from the input sequences.

To capture intraframe information, a version of the ResNet-50 model, which was trained to recognize images from the ImageNet data set, was used.13 The final, fully connected layers of the ResNet model, which are used for classification, are omitted, and the 2048 feature values from the prior layer are used as input to the LSTM.

To capture the interframe information, an LSTM system was used with the outputs of the ResNet-50 as inputs.

The algorithm was trained using an NVIDIA RTX-3090 graphics card and an i9 CPU and an internal RAM of 64 GB. PyTorch library version 1.9.1 was used to develop the code for this project.

Figure 2 shows a block diagram of the architecture. Each 2-s input clip is downsampled and fed into a ResNet-50 algorithm followed by an LSTM. The LSTM gives a prediction, which is one of the three basic maneuver classes.

Figure 2:

Figure shows the workflow architecture of the deep learning network. Frames from the video clips for each of the basic maneuvers are extracted and fed into a convolutional neural network and an LSTM. The architecture is then trained to predict the maneuver based on an input video clip.

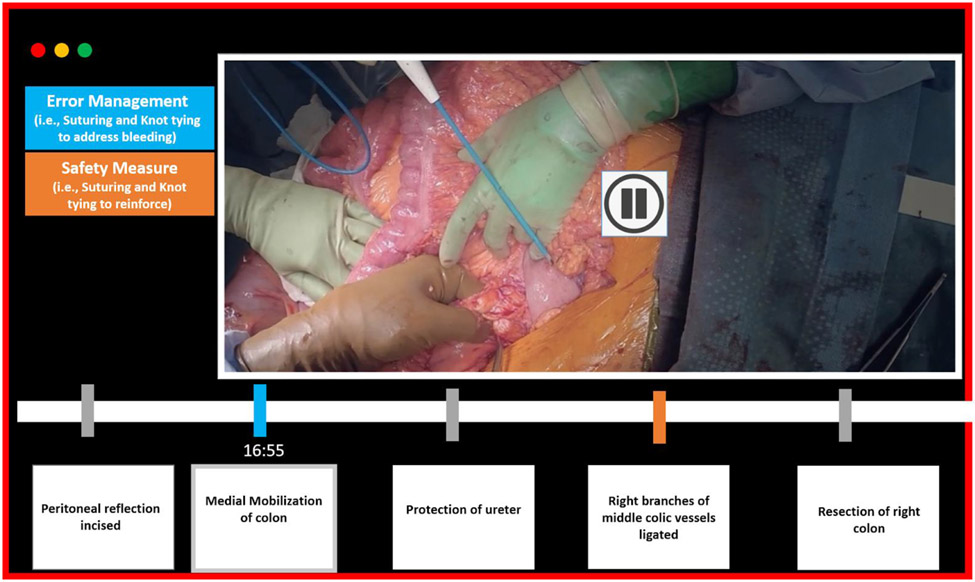

To evaluate the application of this algorithm to a real-life procedure, we chose the colon resection steps for an open colectomy procedure and studied the procedural steps in detail using a procedure-specific checklist.14-16 The source of our videos was YouTube. We reviewed the video with a goal of conceptually evaluating the application of the algorithm to an open procedure and verifying that there exist certain steps where the presence of basic surgical maneuvers indicates noteworthy diversions taken by the surgeon.

A total of five procedural steps were chosen as representative steps. We focused on steps where the presence of suturing activity would be an atypical event and could indicate error management or safety measures taken by the surgeon.

Informed consent was obtained for each participant. It was managed as follows. The consent forms were approved by the Internal Review Board at Stanford University. Volunteers presented and described details of a consent form to the participants at the venue before participation. The participants were then asked to sign the form if they wished to proceed with the procedure. The forms were then collected and filed.

Results

The total number of inputs was equal to 7538, of which 4382 inputs corresponded to suture throw, 1898 clips corresponded to knot tie, and 1258 inputs corresponded to suture cutting. A total of 3965 suture throw inputs, 1062 knot tie inputs, and 1676 suture cutting inputs were used to train the algorithm to ensure that all classes were represented equally. The algorithm ran for 20 epochs.

The accuracy was observed to be 84%. As shown in Table 1, the precision for suture throws, knot ties, and suture cutting was observed to be 87.9%, 60%, and 90.9%, respectively. The test samples size for suture throws, knot ties, and suture cutting were 417, 222, and 196 inputs, respectively.

Table 1 –

The performance of the algorithm.

| Precision (%) |

Train samples |

Test samples |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Suture throws | 84 | 3965 | 417 |

| Knot ties | 87.9 | 1062 | 222 |

| Suture cutting | 90.9 | 1676 | 196 |

Per-class precision is shown along with the number of video samples available for each of three basic maneuvers.

Implication

The current options for video-based review in the case of open colectomy procedures are listed in Table 2. The first column shows the first option—to review the 2-h video and fast forward to important time points with residents. The second option involves applying traditional machine learning (ML) segmentation methods, which will give the steps of the procedure. Instead of watching a 2-h video, you can click on a procedure step, and the video will play that step only. This is the most common use of ML for video analysis.

Table 2 –

Comparison of different video review methods for an open colonoscopy procedure (chosen as an example), estimated time commitment required, and workflow.

| Full review of colon resection procedure |

Procedural steps | Basic maneuvers | Basic maneuvers + procedural steps |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated amount of time | 2 h | 15-30 min | 5-20 min | 5-20 min |

| Work flow and benefits | Manual exploration of key findings based on human observation | Automated labeling of procedural steps. Allows more efficient manual exploration of specific procedure steps | Allows automated labeling of surgical actions, and this allows efficient review of errors and technical approaches | Maximum efficiency in review of errors and technical approaches per procedure step |

The third column shows the video review of basic maneuvers, which is made possible through the algorithm described in this work. The fourth column shows a future vision where the algorithm could be incorporated into currently used procedure step detection algorithms.

In the third column, we include our approach—A dashboard summary of the number of times that suturing took place. You can choose to review specific suturing events, and you can also compare if the procedure you are observing has more or less suturing than is expected based on national averages. The fourth column shows a further option where the time points at which the basic maneuvers occurred and the procedure steps are combined and identified. Basic maneuvers also provide additional information about the technical approaches relating to error management and safety strategies. There are additional benefits when combining basic maneuvers and procedure step segmentation, as this allows observation of basic maneuvers in the context of each procedure step. Overall, the main impact of the combined approach relates to the efficiency of video review.

Figure 3 is a conceptual diagram illustrating the application of basic surgical maneuver detection by showing a representation of a video segmentation tool with our algorithm incorporated. A video of an open colectomy procedure can be segmented according to standard procedural steps. Using our algorithm, additional information regarding error management and safety measures can be added. The algorithm can detect points at which suturing, tying, and cutting are observed in addition to segmentation by procedural steps. By using both streams of information, we are able to highlight points where basic maneuvers are not expected. In this case, the blue timestamp at the point of medial mobilization step indicates that some suturing activity is performed. On clicking this time point, the reviewer may see that the ureter has been inadvertently injured and sutures were placed as an error management strategy. During the ligation of the colic vessels, the orange time point indicates that some safety measures have been undertaken since suturing activity is detected. The reviewer may click on this to view that suturing and knot tying were performed to reinforce the ligation to prevent bleeding. The reviewer may use this additional information to view deviations to typical protocol, understand the context of these deviations, and assess the skill of the surgeon. The example of a colon surgery was picked due to the anatomy, but this concept can be applied to a wide variety of procedures.

Figure 3:

Figure shows a concept diagram of a video segmentation tool that is incorporated with our algorithm. The algorithm is able to identify basic maneuvers and based on the procedure step is able to provide information about any error management or safety measures undertaken from the surgeon.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and evaluated an AI algorithm to automatically identify three basic maneuvers from a simulated enterotomy repair: suture throw, knot tie, and suture cut. As the literature states,7 more work needs to be done to improve the accuracy and efficiency of AI-driven video analysis, and this work serves to advance these goals by enabling accurate and meaningful video segmentation.

Precision

The precision metric is a common way to measure the per-class accuracy of a ML algorithm. The precision of each class is the proportion of correctly classified inputs divided by the total number of predicted inputs.17

Precision = number of true positives/(number of true positives + number of false positives)

The precision for knot ties was 60%. We suspect that the precision was low due to the lack of data for this class compared with the suture throws and suture cuts, where there was more data (hence the higher precision). In the future, training the model with more annotated knot tying videos could improve the precision.

Basic maneuvers can indicate performance and can be linked to outcomes

Prior studies of basic maneuvers have shown links to skill level and outcomes.18-25 In a study by Vedula et al.,18 it was shown that experts perform fewer gestures than residents and have fewer errors. In Hung et al.,26 the authors reviewed videos of Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy procedures and showed that random or unconventional gestures used for needle driving were linked to bleeding and incontinence. They subsequently used a deep learning model to detect surgical gestures from Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy videos. An accuracy of 62% was reported in detecting five different gestures.27 In a study by Bromley et al.,28 it is shown that an optimal number of progressive tension sutures can decrease complications in abdominoplasties.

Understanding basic maneuvers can help to identify safety measures and interventions for error management in open procedures, as previously described for a colectomy. In addition, these maneuvers are also translatable to minimally invasive procedures. For example, in the case of a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, detecting suturing may indicate a safety measure or an error management intervention. Staple line reinforcement to prevent postoperative bleeding and leaks can be seen as a safety measure, whereas suturing after witnessing staple line bleeding can be viewed as error management. In addition, the presence of suturing during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy may demonstrate error management as a result of bile duct or bowel injury.

Limitations

We know that error management and safety measures can be undertaken in different ways depending on the type of surgery and other factors. For example, in minimally invasive surgery, cautery may be performed to achieve hemostasis. Although the trained model that has been described and presented in this work may not be useful in identifying error management and safety measures in certain other use cases (such as in the case of use of bipolar instruments), the video collection protocol, annotation, and model architecture that was chosen in our work can be leveraged in these cases.

Future work

This algorithm is a foundational step in improving the ease and speed of review and analysis of surgical videos. The algorithm can be useful as a tool to aid researchers in further understanding the impact of basic maneuvers on skill, performance, and outcomes across multiple surgical specialties. It can also be used as a tool for training. In the example of the colectomy procedure shown in Figure 3, points of error can be filtered and reviewed in videos by identifying basic surgical maneuvers in certain procedural steps. The causes for the errors can then be identified, and error correction strategies can be taught to trainees.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we note that surgeons’ bandwidth is limited, and reviewing videos of full-length procedures may take up a significant amount of time. AI-enabled video segmentation tools aim to facilitate quick and focused reviews by segmenting the videos according to standard procedural steps. However, real-life surgeries are complex. Procedural steps, which are based on ideal protocols, may not shed light on case complexity and decision-making. We have demonstrated that a reasonably accurate AI-enabled method to automatically detect basic maneuvers can be developed and tested on a data set of simulated enterotomy repair videos. A qualitative concept mapping was demonstrated to show that real-life scenarios can benefit from the identification of basic maneuvers.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH 5R01DK12344502).

Footnotes

Disclosure

None declared.

Meeting Presentation

This work was originally presented at the Academic Surgical Congress, 2022.

REFERENCES

- 1.Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O’Reilly A, et al. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1434–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrahim AM, Varban OA, Dimick JB. Novel uses of video to accelerate the surgical learning curve. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2016;26:240–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ABS to explore video-based assessment in pilot program launching june 2021 ∣ American board of surgery. Available at: https://www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?news_vba04.21. Accessed April 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dath D, Regehr G, Birch D, et al. Toward reliable operative assessment: the reliability and feasibility of videotaped assessment of laparoscopic technical skills. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1800–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrow CR, Kowalewski KF, Li L, et al. Machine learning for surgical phase recognition: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2020;273:684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin Y, Dou Q, Chen H, et al. SV-RCNet: workflow recognition from surgical videos using recurrent convolutional network. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2018;37:1114–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korndorffer JR, Hawn MT, Spain DA, et al. Situating artificial intelligence in surgery: a focus on disease severity. Ann Surg. 2020;272:523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto DA, Axelsson GC, Jones CB, et al. Surgical procedural map scoring for decision-making in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2018;217:356–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamadipanah H, Nathwani J, Peterson K, et al. Shortcut assessment: can residents’ operative performance be determined in the first five minutes of an operative task? Surgery. 2018;163:1207–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basiev K, Goldbraikh A, Pugh CM, Laufer S. Open surgery tool classification and hand utilization using a multi-camera system. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2021;17:1497–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. 2015. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1512.03385. Accessed April 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9:1735–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li L, Li K, Fei-Fei L. ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. In: 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. IEEE; 2009:248–255. Available at: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/conhome/1000147/all-proceedings. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miskovic D, Ni M, Wyles S, et al. Is competency assessment at the specialist level achievable? A study for the national training programme in laparoscopic colorectal surgery in England. Ann Surg. 2013;257:476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schumpelick V, Kasperk R, Stumpf M. Atlas of General Surgery. New York, NY: Thieme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellison EC, Zollinger RM. Colectomy, right. In: Zollinger’s Atlas of Surgical Operations, 10e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gehanno JF, Rollin L, Le Jean T, Louvel A, Darmoni S, Shaw W. Precision and recall of search strategies for identifying studies on return-to-work in medline. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vedula SS, Malpani AO, Tao L, et al. Analysis of the structure of surgical activity for a suturing and knot-tying task. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmidi N, Gao Y, Béjar B, et al. String motif-based description of tool motion for detecting skill and gestures in robotic surgery. In: Salinesi C, Norrie MC, Pastor Ó, eds. Advanced Information Systems Engineering. Vol 7908. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2013:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmidi N, Poddar P, Jones JD, et al. Automated objective surgical skill assessment in the operating room from unstructured tool motion in septoplasty. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2015;10:981–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKenzie L, Ibbotson JA, Cao CGL, Lomax AJ. Hierarchical decomposition of laparoscopic surgery: a human factors approach to investigating the operating room environment. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2001;10:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin HC, Shafran I, Murphy TE, Okamura AM, Yuh DD, Hager GD. Automatic detection and segmentation of robot-assisted surgical motions. In: Duncan JS, Gerig G, eds. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2005. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2005:802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen J, Solazzo M, Hannaford B, Sinanan M. Task decomposition of laparoscopic surgery for objective evaluation of surgical residents’ learning curve using hidden markov model. Comput Aided Surg. 2002;7:49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiley CE, Lin HC, Varadarajan B, et al. Automatic recognition of surgical motions using statistical modeling for capturing variability. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2008;132:396–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reiley CE, Hager GD. Task versus subtask surgical skill evaluation of robotic minimally invasive surgery. In: Yang GZ, Hawkes D, Rueckert D, Noble A, Taylor C, eds. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2009. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2009:435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J, Oh PJ, Cheng N, et al. Use of automated performance metrics to measure surgeon performance during robotic vesicourethral anastomosis and methodical development of a training tutorial. J Urol. 2018;200:895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luongo F, Hakim R, Nguyen JH, Anandkumar A, Hung AJ. Deep learning-based computer vision to recognize and classify suturing gestures in robot-assisted surgery. Surgery. 2020;169:1240–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bromley M, Marrou W, Charles-de-Sa L. Evaluation of the number of progressive tension sutures needed to prevent seroma in abdominoplasty with drains: a single-blind, prospective, comparative, randomized clinical trial. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2018;42:1600–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]