Study Design.

Controlled animal study.

Objective.

To assess the cellular contribution of autograft to spinal fusion and determine the effects of intraoperative storage conditions on fusion.

Summary of Background Data.

Autograft is considered the gold standard graft material in spinal fusion, purportedly due to its osteogenic properties. Autograft consists of adherent and non-adherent cellular components within a cancellous bone scaffold. However, neither the contribution of each component to bone healing is well understood nor are the effects of intraoperative storage of autograft.

Materials and Methods.

Posterolateral spinal fusion was performed in 48 rabbits. Autograft groups evaluated included: (1) Viable, (2) partially devitalized, (3) devitalized, (4) dried, and (5) hydrated iliac crest. Partially devitalized and devitalized grafts were rinsed with saline, removing nonadherent cells. Devitalized graft was, in addition, freeze/thawed, lysing adherent cells. For 90 minutes before implantation, air dried iliac crest was left on the back table whereas the hydrated iliac crest was immersed in saline. At 8 weeks, fusion was assessed through manual palpation, radiography, and microcomputed tomography. In addition, the cellular viability of cancellous bone was assayed over 4 hours.

Results.

Spinal fusion rates by manual palpation were not statistically different between viable (58%) and partially devitalized (86%) autografts (P = 0.19). Both rates were significantly higher than devitalized and dried autograft (both 0%, P < 0.001). In vitro bone cell viability was reduced by 37% after 1 hour and by 63% after 4 hours when the bone was left dry (P < 0.001). Bone cell viability and fusion performance (88%, P < 0.001 vs. dried autograft) were maintained when the graft was stored in saline.

Conclusions.

The cellular component of autograft is important for spinal fusion. Adherent graft cells seem to be the more important cellular component in the rabbit model. Autograft left dry on the back table showed a rapid decline in cell viability and fusion but was maintained with storage in saline.

Key words: adherent cells, autograft, bone graft, cell viability, cellular contribution, graft storage, iliac crest bone graft, nonadherent cells, posterolateral spinal fusion, spinal fusion

Autograft is often considered the gold standard graft material in spinal fusion, purportedly due to its osteogenic properties.1–4 This osteogenic potential has been documented in studies of the iliac crest, local bone, and even bone dust generated as a result of high-speed burring.5–7 While autograft harvest from the iliac crest is burdened by concerns surrounding donor-site morbidity and increased operating time, local bone is often freely available for use during spinal procedures.8–10 Recent studies have found similar radiographic fusion outcomes whether iliac crest or local bone was utilized,11,12 although Sengupta et al 13 found superior results in multilevel posterolateral fusion procedures when iliac crest autograft was used.

The bone-forming potential of autograft may derive from the cancellous/corticocancellous bone scaffold itself, or from the contributions of adherent cells and/or the nonadherent cellular milieu (i.e., bone marrow cells). These cellular components include osteoblasts, osteoclasts, osteocytes, osteogenic precursor cells, and hematopoietic bone marrow elements found within or surrounding the bone scaffold.14,15 Cellular components of autograft may be classified based on adherence to the bone scaffold; osteoblasts, osteoclasts, osteocytes, and osteogenic precursor cells are presumed to be adherent cells, whereas hematopoietic cells are presumed to be nonadherent.15 Noncellular components including exosomes, growth factors, extracellular matrix, and other proteins have also been implicated in bone formation.16,17 The contributions of each graft component to fusion, however, are not well understood. Previous studies have identified cells of the endosteum, which lines internal cavities of bone, as the main source of osteogenesis in graft, whereas osteocytes and free marrow cells were found to be minor or noncontributors.18,19 In addition, Gould et al 20 demonstrated that autograft bone contributes cells that directly form bone within a fusion mass and that this contribution to fusion occurs at all stages of fusion, not only during the early stages. There has also been recent discussion over the contribution, or lack thereof, of cells in allogeneic cell bone matrices,21,22 which begs additional questions regarding the role of cells in autograft as well as how their storage and handling during surgery can affect graft performance.

While keeping tissue specimens moist using saline or media to preserve cell viability is standard benchtop laboratory practice, similar practices are, surprisingly, not mandated for intraoperative storage of autografts. During surgery, autograft may be harvested and left out on the back table for prolonged periods of time, which can adversely affect osteogenic potential.23–25 Previous studies have also found decreased functional activity including cell metabolism and proliferation from bone grafts that have been left out dry relative to those stored in saline.25,26 However, these studies have primarily been limited to in vitro/ex vivo analyses and as such, questions remain surrounding how intraoperative storage conditions of autograft may influence spinal fusion in vivo. Here, we first systematically assess how autograft cellular components affect bone fusion performance. We test viable (untreated), partially devitalized (nonadherent cells removed), and devitalized (nonadherent cells removed and adherent cells lysed) autografts in a well-characterized rabbit posterolateral fusion model.27 We then evaluate ex vivo cell viability of bone left out dry or immersed in saline. Finally, we examine how these storage conditions affect fusion performance using autograft in the rabbit model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Posterolateral Fusion Studies

Forty-eight female New Zealand White rabbits (Western Oregon Rabbit Company, Philomath, OR) 6 months old were used. Autograft from iliac crests (2.5–3 cm3, ~1.7–1.8 g per side) was harvested and morselized using rongeurs to pieces 1 to 4 mm in size. Autograft groups evaluated were: (1) Viable, (2) partially devitalized, (3) devitalized, (4) dried, (5) hydrated, and (6) anesthesia control autograft (n = 8 rabbits/group, randomly assigned).

For these studies, a basic power analysis was performed to confirm statistical significance could be reached in the presence of relatively large differences; specifically, that significance would be reached if the control group was within the normal range and the test group dropped to 0% fusion. Based on this analysis, our current sample size was chosen, assuming a unilateral fusion rate difference of 8/16 (50%) versus 0/16 (0%) to reach statistical significance (P < 0.01).

In the first in vivo experiment, viable autograft was compared with partially devitalized and devitalized autograft to grossly determine if there is any effect of the cellular component on spinal fusion. For the viable autograft condition, morselized autograft was immediately loaded and deployed using open-barrel 3 mL syringes. For the partially devitalized and devitalized groups, morselized autograft was vigorously and repeatedly (2×) rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove the nonadherent cellular milieu. Rinse effluents were collected, and the removal of nucleated cells and red blood cells was confirmed using an automated cell counter (Logos Biosystems, Anyang, South Korea). For the devitalized group, the graft was, in addition, subjected to a freeze/thaw cycle (8 min in dry ice, 2 min in 37 °C water bath) to lyse the remaining adherent cells.

In the second in vivo experiment, dried autograft was compared with hydrated autograft to assess the effects of autograft storage conditions. For 90 minutes before implantation, dried autograft was left on the back table under ambient conditions to simulate plausible intraoperative storage conditions, while hydrated autograft was submerged in saline to prevent drying. For the anesthesia control group, rabbits were maintained under 90 additional minutes of anesthesia before implantation with freshly morselized autograft to match the anesthesia regimens of the dried and hydrated autograft groups to account for any possible influence of additional time under anesthesia on the fusion performance of viable autograft.

Single-level posterolateral fusion procedure was performed between the L4 and L5 vertebrae.27 Transverse processes (TPs) were gently decorticated with a motorized burr. 2.5 to 3 cm3 of autograft was placed bilaterally (5–6 cm3 total) in the intertransverse space. Graft placement was confirmed by posteroanterior radiograph (Figure 1). Radiographic images were acquired by MinXray HF 100/30 generator (MinXray, Northbrook) and DR imaging plate (Digital X-Ray P35i, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Figure 1.

Representative radiographs immediately after autograft implantation for viable (A), partially devitalized (B), devitalized (C), anesthesia control (D), hydrated (E), and dried (F) autograft groups.

Rabbits were euthanized 8 weeks postoperatively through intravenous injection of concentrated barbiturate solution. Explanted lumbar spines were manually tested for intersegmental motion by 2 independent trained observers who remained blinded to group designations. Any motion detected between the facets or TPs of L4 and 5 was considered a failure of fusion. The absence of motion was considered a successful fusion. Harvested spine segments were imaged by radiograph and microcomputed tomography (μCT; Quantum GX, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and assessed for fusion. For all endpoints, left and right fusion masses were analyzed individually and graded as fused when there was contiguous bone bridging the TPs.

Explanted spines were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and processed for routine decalcified paraffin histology. Sagittal histology sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histology was evaluated at the host decorticated TPs and in the middle of the fusion to determine how the different autograft preparations participated in the healing process. Local cell and tissue responses were also examined.

Ex Vivo Bone Viability Studies

Ex vivo bone cell viability was assessed to determine the effect of graft storage conditions on harvested bone. Sheep bone (Ibex Preclinical Research, Logan, UT) or cow bone (Sierra for Medical Science, Whittier, CA) were sourced from other studies from animals 2 to 3 years old at sacrifice. Bones from larger animals were utilized for this study due to the limited cancellous bone available from rabbits. Femurs were preserved on ice for 12 to 24 hours until tissue harvest. Cancellous bone was morselized using rongeurs into ~4 mm pieces and then left to dry under ambient conditions or immersed in PBS for defined time periods. Nonadherent cells were removed from the morselized bone by vigorous and repeated (2×) PBS rinses. Cell viability of the remaining adherent cells was assayed using Alamar Blue (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) fluorescence indicator dye per manufacturer’s instructions at baseline (T = 0), 1, 2, and 4 hours. Fluorescence measured at 1, 2, or 4 hours was normalized to the baseline fluorescence to calculate cell viability, with the baseline representing 100% cell viability.28,29

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Minitab software (State College, PA) using Fisher Exact Test for categorical data and 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey post hoc test for continuous data.

RESULTS

Cellular contribution to fusion was first investigated in the rabbit fusion model. Three rabbits died after postoperation complications (2 from the viable group and 1 from the partially devitalized group) and were not replaced. All other animals recovered well after surgery, and no other adverse reactions were noted. Manual palpation (MP) fusion assessment results at 8 weeks are presented in Table 1. Rabbits implanted with viable autograft demonstrated a 58% fusion rate, as expected for this model,30 compared with a 0% fusion rate for devitalized autograft. Partially devitalized autograft yielded an 86% fusion rate which was not statistically different (P = 0.19) from the viable autograft result. Both viable and partially devitalized autograft fusion rates were significantly higher (P < 0.001) than devitalized autograft.

TABLE 1.

Cellular Contribution to Fusion–Posterolateral Fusion Rates (Unilateral)

| Autograft Condition | Fusion by MP; N/n (%) | Fusion by Radiography; N/n (%) | Fusion by μCT; N/n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viable | 7/12 (58)† | 8/12 (67)* | 7/12 (58)† |

| Partially devitalized | 12/14 (86)† | 14/14 (100)† | 14/14(100)† |

| Devitalized | 0/16 (0) | 3/16 (19) | 0/16 (0) |

Statistical significance versus devitalized autograft denoted by:

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

μCT indicates microcomputed tomography; MP, manual palpation.

Fusion by radiographic and μCT assessment of bone bridging between the L4 and L5 TPs are also presented in Table 1. Radiographic and μCT assessments of fusion were statistically similar to MP results (P = 0.23). However, it is noted that radiographic fusion rates trended higher than that of MP for all groups.

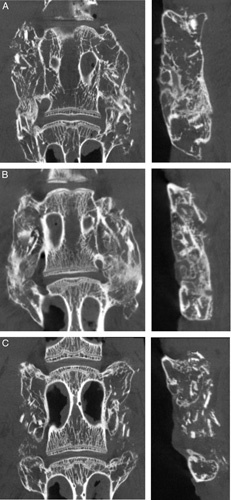

Representative μCTs from each group are presented in Figure 2. μCT reconstructions of the viable and partially devitalized groups (Figure 2A, B) displayed bilateral fusion with contiguous bone masses bridging between the L4 and L5 TPs in spines graded as fused. In contrast, the devitalized autograft group (Figure 2C) showed evidence of new bone formation localized at the TPs but lacked bridging bone. Instead, disparate islands of bone are noted between the TPs.

Figure 2.

Representative μCTs at 8 weeks in coronal and sagittal planes demonstrating differences in bone formation between viable (A), partially devitalized (B), and devitalized (C) autograft groups. Viable (A) and partially devitalized (B) autografts had bilateral fusions bridging the TPs in spines graded as fused. Devitalized (C) autograft lacked bone bridging between the TPs. μCT indicates microcomputed tomography; TP, transverse process.

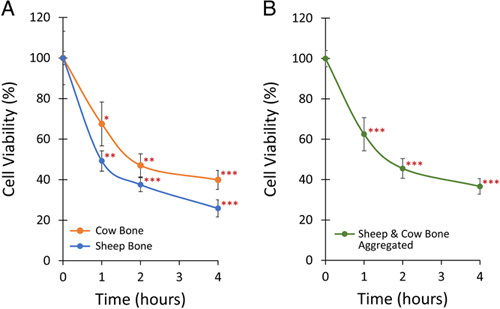

Next, we investigated how the storage of bone impacts adherent cell viability. Ex vivo cell viability results are presented in Figure 3 and Table 2, with results normalized to the baseline (T = 0) cell viability. Viability for both sheep and cow bone left out dry declined quickly with time and followed similar trends (Figure 3A). After 1 hour, viability dropped to 67% and 49% for cow and sheep bone, respectively. This viability decline continued, though less drastically, at 2 and 4 hours to 47% and 40% for cow bone, and 38% and 26% for sheep bone. Aggregated results (Figure 3B) showed highly significant decreases in viability relative to baseline at 1, 2, and 4 hours to 63%, 46%, and 37%, respectively (all P<0.001).

Figure 3.

Adherent bone cell viability after 1, 2, or 4 hours. A, Sheep (n ≥ 3) and cow bone (n ≥ 8) cell viability both decreased in a similar manner when left out to dry after harvest. B, Combined sheep and cow bone cell viability decreased to 63% after 1 hour, 46% after 2 hours, and 37% after 4 hours. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. * denotes P < 0.05, ** denotes P < 0.01, and *** denotes P < 0.001 relative to T = 0 hour cell viability.

TABLE 2.

Adherent Bone Cell Viability in Cow and Sheep Bone

| Time (h) | Viability (%) Mean ± SEM (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cow Bone | Sheep Bone | Aggregated (Cow and Sheep) | ||||

| 0 | 100±3.3 | 94, 107 | 100±13 | 74, 126 | 100±4.0‡ | 92, 108 |

| 1 | 67±11* | 46, 89 | 49±5.0† | 39, 59 | 63±8.2‡ | 47, 79 |

| 2 | 46±5.7† | 36, 58 | 38±3.5‡ | 31, 44 | 46±4.9‡ | 36, 55 |

| 4 | 37±4.7‡ | 31, 49 | 26±4.2‡ | 18, 34 | 37±3.9‡ | 29, 44 |

Statistical significance versus T = 0-hour cell viability denoted by:

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

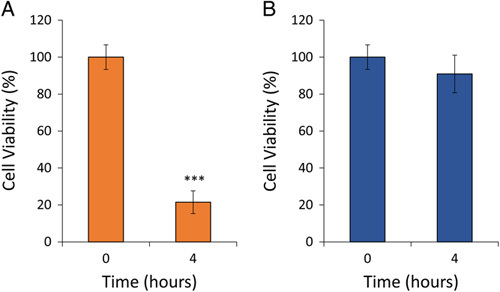

To determine whether losses in adherent cell viability can be prevented, sheep bone was either left out dry or immersed in saline for 4 hours; viability results are shown in Figure 4 and Table 3. Viability for dried samples dropped to 21% after a 4-hour drying period, which was significantly lower than the baseline viability (P < 0.001). Samples immersed in saline had statistically similar viability at both time points (P=0.71).

Figure 4.

Adherent sheep bone cell viability (n ≥ 3) after 4 hours. A, Bone cell viability decreased to 21% after being left out to dry for 4 hours. B, Bone cell viability remained comparable to T = 0-hour cell viability when a bone was immersed in saline. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. *** denotes P < 0.001 relative to T = 0 hour cell viability.

TABLE 3.

Adherent Bone Cell Viability Stored Dry or in Saline

| Time (h) | Storage Condition | Viability (%); Mean ± SEM (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | N/A | 100±6.7 | 87, 113 |

| 4 | Saline | 91±10 | 71, 111 |

| 4 | Dry | 21±2.5* | 9, 34 |

Statistical significance versus T = 0 hour cell viability by:

P < 0.001.

N/A indicates not applicable.

Ex vivo study results were then corroborated in the rabbit posterolateral fusion model; results are presented in Table 4. The anesthesia control group yielded a 69% fusion rate by MP, statistically similar to the viable (58%, P = 0.70) autograft group. Autografts left out to dry for 90 minutes yielded a 0% fusion rate by MP, whereas autografts immersed in saline resulted in an 88% fusion rate, significantly higher than dried autografts (P<0.001).

TABLE 4.

Intraoperative Storage of Autograft—Posterolateral Fusion Rates (Unilateral)

| Autograft Condition | Fusion by MP; N/n (%) | Fusion by Radiography; N/n (%) | Fusion by μCT; N/n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia control | 11/16 (69)‡ | 14/16 (88) | 11/16 (69)‡ |

| Dried | 0/16 (0) | 9/16 (56) | 0/16 (0) |

| Hydrated | 14/16 (88)‡ | 16/16 (100)† | 15/16 (94)‡ |

Statistical significance versus dried autograft denoted by:

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

μCT indicates microcomputed tomography; MP, manual palpation.

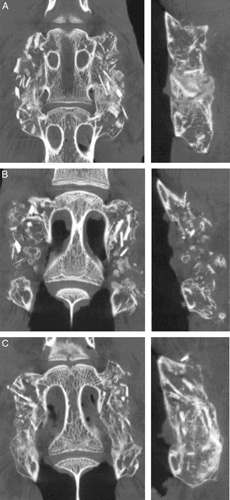

Fusion rates determined radiographically were again trending higher relative to those by MP. For the dried autograft condition, radiographic fusion was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than assessment by MP. Fusion rates by μCT were comparable to those by MP. Representative μCTs from each group are presented in Figure 5. μCT reconstructions of the anesthesia control and hydrated groups (Figure 5A, C) displayed bilateral fusion with contiguous bone masses bridging between the L4 and L5 TPs in spines graded as fused. In contrast, dried autograft (Figure 5B) lacked bone bridging between the TPs, and disparate islands of bone are noted between the TPs.

Figure 5.

Representative μCTs at 8 weeks in coronal and sagittal planes demonstrating differences in bone formation between anesthesia control (A), dried (B), and hydrated (C) autograft groups. Anesthesia control (A) and hydrated (B) autografts had bilateral fusions bridging the TPs in spines graded as fused. Dried autograft (C) lacked bone bridging between the TPs. μCT indicates microcomputed tomography; TP, transverse process.

Histologic evaluation (Figure 6) supported the observations from μCT in terms of bone bridging across the TPs in the sagittal plane in spines graded as fused in the viable (Figure 6A), partially devitalized (Figure 6B), anesthesia control (Figure 6D) and hydrated (Figure 6F) groups. An osteoconductive response was observed for autograft in all groups when placed directly on the host decorticated TPs, as the autograft facilitated the bone formation and remodeling over this biological bed. In the middle of the fusion mass, however, important histologic differences were noted between groups. Autografts in the viable, partially devitalized, anesthesia control, and hydrated groups were able to facilitate fusion between the TPs, and areas of osteoblastic and chondroblastic activity were noted for these 4 groups. Devitalized (Figure 6C) and dried autograft (Figure 6E) remained present and were associated with predominantly fibrous tissue and the lack of osteogenic or chondroblastic activity between the TPs. Interestingly, the residual graft pieces in all groups displayed empty osteocyte lacunae, even in the groups that were otherwise associated with robust bone formation.

Figure 6.

Representative H and E histology images of fusion masses for viable (A), partially devitalized (B), devitalized (C), anesthesia control (D), dried (E), and hydrated (F) autograft groups. Viable (A), partially devitalized (B), anesthesia control (D), and hydrated (F) autograft showed residual graft incorporated into new marrow-filled bridging bone. Devitalized (C) and dried (E) autografts showed residual grafts primarily surrounded by fibrous tissue with little bone remodeling. ▴indicates new bone, ★ indicates bone marrow, ✱ indicates residual graft, and ■ indicates fibrous tissue. Scale bar is 2 mm. H and E indicates hematoxylin and eosin.

DISCUSSION

Bone healing in spinal fusion is a complex physiological process influenced by cellular, biochemical, and mechanical mechanisms.15 Although autograft is frequently used to promote fusion, the contribution of its constitutive elements to fusion is poorly understood, as is how intraoperative graft storage affects fusion performance.

This study demonstrated that viable autograft yielded significantly higher fusion results compared with the devitalized graft, suggesting that the cellular component of autograft promotes fusion. In the devitalized group, removal or lysis of both the adherent and nonadherent graft cells (i.e., the total cell population) led to no fusion by MP, suggesting that graft cells are vital for fusion. This finding aligns with work by Gould et al,20 which utilized fluorescently labeled graft cells to conclusively demonstrate that cortical/cancellous bone grafts contribute cells that directly form bone in the fusion mass.

Next, we found that viable and partially devitalized autograft achieved comparable fusion results, suggesting that the non-adherent cellular component of autograft (i.e., bone marrow) is not essential for fusion, as strong fusion results were reached when this component was removed from the graft. Instead, the adherent cell population seems to be the more important cellular component for fusion. This finding aligns with previous studies that systematically investigated the constituents of bone grafts and found that marrow cells are minor or noncontributors to fusion.18,19

In the rabbit model, fusion results by MP and μCT were generally concordant, while radiographic fusion results were consistently higher. Assessment of fusion by radiography may have overpredicted fusion due to the radiopacity of the morselized autograft. In addition, radiographic fusion has been shown to overestimate the rate of spinal fusion relative to MP, which is considered a more reliable assessment method.27,31,32 Thus, radiographic fusion was not used as a definitive analysis of fusion in this study, although this metric remains valuable as it represents the standard clinical modality for fusion assessment.

Histologic results further corroborated the trends observed in the MP and μCT fusion rates between autograft groups. All graft materials were able to facilitate healing at the site of the decorticated TP, likely through an osteoconductive mechanism. In the middle of the fusion, however, only viable, partially devitalized, anesthesia control, and hydrated autograft facilitated TP to TP fusion and displayed areas of osteogenic cell activity. These results were juxtaposed with the devitalized and dried autograft groups, which were unable to facilitate TP-to-TP fusion and lacked osteogenic cell activity. These histologic findings emphasize the important interplay between graft quality and biological site and suggest a key role of osteogenic cells in promoting spinal fusion.

Results from the rabbit model led us to investigate how intraoperative storage of autograft affects adherent cell viability and fusion performance. During spinal procedures, a harvested autograft is often left on the back table under ambient conditions for a period of minutes to hours before graft placement, depending on the surgical workflow. Others have reported the loss of osteogenic potential and function of bone cells when left out dry, although these studies were generally limited to in vitro models.25,26,33–35 Laursen et al 25 found that the proliferation of cells from freshly harvested iliac crest graft or graft stored in saline for 2 hours was significantly higher compared with the bone left to dry. Maus et al 26 similarly found significantly lower cell metabolism in cells from bone left to dry relative to storage in saline. These studies and others have also investigated a variety of bone graft storage solutions including saline, dextrose, buffered sucrose, Lactated Ringer, blood, and cell culture mediums, among others.25,26,34,36 However, results from these studies have been mixed, with no clear answer as to an optimal bone graft storage solution beyond demonstrating that storing graft in solution is preferable to dry storage.25,26,34 Furthermore, these studies did not directly demonstrate the impact of storing graft dry or in solution on fusion outcomes, which the current study addresses.

In this study, we found that adherent cell viability significantly declined in ex vivo models when left out dry for as little as one hour. Though the magnitude of loss in cell viability differed between cow and sheep models, the trends in viability decline were similar for both models and this finding may extend to other models. Immersing harvested bone in saline, however, was sufficient to maintain adherent cell viability similar to freshly harvested bone. Fusion results in the rabbit model corroborated the ex vivo cell viability results; autograft left out dry for 90 minutes resulted in no fusion by MP, whereas graft stored in saline yielded fusion results comparable to viable autograft. Taken together, these findings suggest that harvested autograft drying during surgery is a clinically relevant problem that can be remediated by storing the graft in sterile saline until it is ready to be placed.

The present study has several limitations. A relatively small number of rabbits were tested for each group and thus may not have been able to detect significant differences between all groups (e.g., between viable and partially devitalized groups). In addition, all rabbits were tested at a single time point. Lastly, this study does not provide a mechanistic understanding of how spinal fusion is adversely affected by autograft left under ambient conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

The adherent cell component of autograft is essential for spinal fusion. When harvested bone is left out on the back table, cell viability rapidly declines, as does fusion performance. However, storing autografts in saline intraoperatively can maintain cell viability and fusion performance equivalent to the fresh bone. Thus, surgeons should protect graft viability by minimizing graft drying when possible during surgery.

Key Points

Adherent cells in autograft are more important to fusion than the nonadherent cellular milieu.

Autograft fusion performance rapidly declines when the graft is left out dry.

Fusion performance can be maintained by storing harvested autografts in saline.

Surgeons should minimize graft drying during surgery to protect fusion performance.

Footnotes

The animal study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use (IACUC) committee.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Jeremy A. Lombardo, Email: jeremy.lombardo@seaspine.com.

Nick Russell, Email: nick.russell@seaspine.com.

Jiawei He, Email: jiawei.he@seaspine.com.

Michael J. Larson, Email: mike@oiresearchlab.com.

William R. Walsh, Email: w.walsh@unsw.edu.au.

Frank Vizesi, Email: frank.vizesi@seaspine.com.

References

- 1.Vaz K, Verma K, Protopsaltis T, Schwab F, Lonner B, Errico T. Bone grafting options for lumbar spine surgery: a review examining clinical efficacy and complications. SAS J. 2010;4:75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Souza M, Macdonald NA, Gendreau JL, Duddleston PJ, Feng AY, Ho AL. Graft materials and biologics for spinal interbody fusion. Biomedicines. 2019;7:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grabowski G, Cornett CA. Bone graft and bone graft substitutes in spine surgery: Current concepts and controversies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mundis GM, Lombardo J, Russell N, He J, Vizesi F. 171. Bone on the back table: effects of autograft handling on spinal fusion. Spine J. 2022;22:S91. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao R, Street M, Tay ML, et al. Human spinal bone dust as a potential local autograft. Spine. 2018;43:E193–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Risbud MV, Shapiro IM, Guttapalli A, et al. Osteogenic potential of adult human stem cells of the lumbar vertebral body and the iliac crest. Spine. 2006;31:83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geurts J, Ramp D, Schären S, Netzer C. Georg-Schmorl-Prize Of The German Spine Society (DWG) 2016: comparison of in vitro osteogenic potential of iliac crest and degenerative facet joint bone autografts for intervertebral fusion in lumbar spinal stenosis. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:1408–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawin PD, Traynelis VC, Menezes AH. A comparative analysis of fusion rates and donor-site morbidity for autogeneic rib and iliac crest bone grafts in posterior cervical fusions. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:255–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Younger EM, Chapman MW. Morbidity at bone graft donor sites. J Orthop Trauma. 1989;3:192–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silber JS, Anderson DG, Daffner SD, et al. Donor site morbidity after anterior iliac crest bone harvest for single-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine. 2003;28:134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito Z, Matsuyama Y, Sakai Y, et al. Bone union rate with autologous iliac bone versus local bone graft in posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine. 2010;35:E1101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuchman A, Brodke DS, Youssef JA, et al. Iliac crest bone graft versus local autograft or allograft for lumbar spinal fusion: a systematic review. Glob Spine J. 2016;6:592–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sengupta DK, Truumees E, Patel CK, et al. Outcome of local bone versus autogenous iliac crest bone graft in the instrumented posterolateral fusion of the lumbar spine. Spine. 2006;31:985–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalfas IH. Principles of bone healing. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilitsis JG, Lucas DR, Rengachary SR. Bone healing and spinal fusion. J Neurosurg. 2002;13:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devescovi V, Leonardi E, Ciapetti G, Cenni E. Growth factors in bone repair. Chir Organi Mov. 2008;92:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Jiao G, Ren S, et al. Exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells enhance fracture healing through the promotion of osteogenesis and angiogenesis in a rat model of nonunion. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray JC, Elves MW. Donor cells’ contribution to osteogenesis in experimental cancellous bone grafts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;163:261–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craig Gray J, Elves MW. Early osteogenesis in compact bone isografts: a quantitative study of the contributions of the different graft cells. Calcif Tissue Int. 1979;29:225–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gould SE, Rhee JM, Tay BKB, Otsuka NY, Bradford DS. Cellular contribution of bone graft to fusion. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:920–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abedi A, Formanek B, Russell N, et al. Examination of the role of cells in commercially available cellular allografts in spine fusion: an in vivo animal study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102:e135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaz RR, Savardekar AR, Brougham JR, Terrell D, Sin A. Investigating the efficacy of allograft cellular bone matrix for spinal fusion: a systematic review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2021;50:E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puranen J. Reorganization of fresh and preserved bone transplants. An experimental study in rabbits using tetracycline labelling. Acta Orthop Scand. 1966;37:1–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohr H, Ravn HO, Werner H. The osteogenic effect of bone transplants in rabbits. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1968;50:866–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laursen M, Christensen FB, Bünger C, Lind M. Optimal handling of fresh cancellous bone graft: different peroperative storing techniques evaluated by in vitro osteoblast-like cell metabolism. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maus U, Andereya S, Gravius S, et al. How to store autologous bone graft perioperatively: an in vitro study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:1007–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boden SD, Schimandle JH, Hutton WC. An experimental lumbar intertransverse process spinal fusion model: radiographic, histologic, and biomechanical healing characteristics. Spine. 1995;20:412–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rampersad SN. Multiple applications of alamar blue as an indicator of metabolic function and cellular health in cell viability bioassays. Sensors (Switzerland). 2012;12:12347–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamiloglu S, Sari G, Ozdal T, Capanoglu E. Guidelines for cell viability assays. Food Frontiers. 2020;1:332–49. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghodasra JH, Daley EL, Hsu EL, Hsu WK. Factors influencing arthrodesis rates in a rabbit posterolateral spine model with iliac crest autograft. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:426–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yee AJM, Bae HW, Friess D, Robbin M, Johnstone B, Yoo JU. Accuracy and interobserver agreement for determinations of rabbit posterolateral spinal fusion. Spine. 2004;29:1308–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riordan AM, Rangarajan R, Balts JW, Hsu WK, Anderson PA. Reliability of the rabbit postero-lateral spinal fusion model: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:1261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner M, Ramp WK. Short-term storage of freshly harvested bone. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:868–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Q, Li Z, Liu B, Yuan X, Guo S, Helms JA. Improving intraoperative storage conditions for autologous bone grafts: an experimental investigation in mice. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;13:2169–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bassett CA. Clinical implications of cell function in bone grafting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1972;87:49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McAnulty JF. Effect of various short-term storage methods on viability of cancellous bone fragments. Am J Vet Res. 1999;60:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]