Background:

Mechanical stretching of the skin (ie, tissue expansion) could generate additional skin, but it is limited by the intrinsic growth capacity. The authors conducted a study of autologous concentrated growth factor (CGF) to promote skin regeneration by increasing skin thickness and area during tissue expansion.

Methods:

A single-center randomized controlled trial was conducted from 2016 to 2019. Participants undergoing skin expansion received either CGF or saline by means of intradermal injection on the expanded skin (0.02 mL/cm2), for a total of three treatments at 4-week intervals. The primary endpoint was the expanded skin thickness at 12 weeks, which was measured by ultrasound. The secondary endpoints included skin thickness at 4 and 8 weeks and surface area, expansion index, and skin texture score of the expanded skin at 12 weeks. Safety assessments, for infection symptoms and nodule formation, were assessed at 24 weeks.

Results:

In total, 26 patients were enrolled and assigned to the CGF or control group. Compared with the control group, the CGF group had significantly increased skin thickness at 8 (control, 1.1 ± 0.1 mm; CGF, 1.4 ± 0.1 mm; −0.6 to 0.0 mm; P = 0.047) and 12 weeks (control, 1.0 ± 0.1 mm; CGF, 1.3 ± 0.1 mm; −0.6 to 0.0 mm; P = 0.047). Compared with the baseline thickness (control, 1.6 ± 0.1 mm; CGF, 1.5 ± 0.1 mm; −0.3 to 0.5 mm; P = 0.987), skin thickness was sustained in the CGF group at 8 weeks after treatment (−0.1 to 0.3 mm; P = 0.711) but decreased in the control group (0.3 to 0.7 mm; P < 0.001). At 12 weeks, the CGF group showed greater increases in surface area (control, 77.7 ± 18.5 cm2; CGF, 135.0 ± 15.7 cm2; 7.2 cm2 to 107.4 cm2; P = 0.027) and expansion index (control, 0.9 ± 0.1; CGF, 1.4 ± 0.2; 0.0 to 0.8; P = 0.030) than the control group. In addition, CGF-treated skin showed an improvement in texture [CGF: grade 3, n = 2 (15.8%), grade 2, n = 4 (30.7%); control: grade 3, n = 0 (0.0%), grade 2, n = 3 (23.0%)]. No severe adverse events occurred.

Conclusion:

CGF treatment increases skin thickness and area during tissue expansion, and represents a safe and effective strategy for managing skin expansion.

Clinical Relevance Statement:

The findings of this study indicate that it is practically feasible to improve skin regeneration by applying autologous platelet concentrate therapy for skin expansion management.

CLINICAL QUESTION/LEVEL OF EVIDENCE:

Therapeutic, II.

Tissue expansion is a reliable method to provide additional skin for repairing skin defects.1 During the course of expansion, an excess of skin was regenerated through the growth-promoting effect induced by mechanical stretching,2,3 but the regeneration was limited to the intrinsic growth capacity.4 Although drugs, such as anticontractile agents, papaverine, and dimethyl sulfoxide, have been studied for promoting the expansion course, these have caused additional complications.5–7 We previously reported that stem cell therapies could effectively promote stretching-induced skin regeneration8,9; however, harvesting stem cells caused additional damage to the body.

Platelet concentrate, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and concentrated growth factor (CGF), has been known as a source of autologous high-concentration growth factor that stimulates cell proliferation and differentiation.10 Wang et al. have reported that PRP treatment promotes vascularization and skin growth during the expansion course.11 CGF, a modified form of platelet concentrate, was debuted by Clark and Sacco in 2006.12 CGF could promote the proliferation and activation of fibroblasts, thus increasing the deposition of new collagen.13 Also, CGF is beneficial for the proliferation and differentiation of endothelial cells, resulting in tissue neovascularization.14,15 These growth-promoting effects of CGF can improve the skin regeneration during the expansion course,4,16 and we hypothesized that CGF treatment could facilitate skin thickening and expanding, in turn leading to promotion of skin expansion. This clinical trial aimed to determine the efficiency and safety of the intradermal injection of autologous CGF for promoting skin regeneration in the management of skin expansion.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Oversight

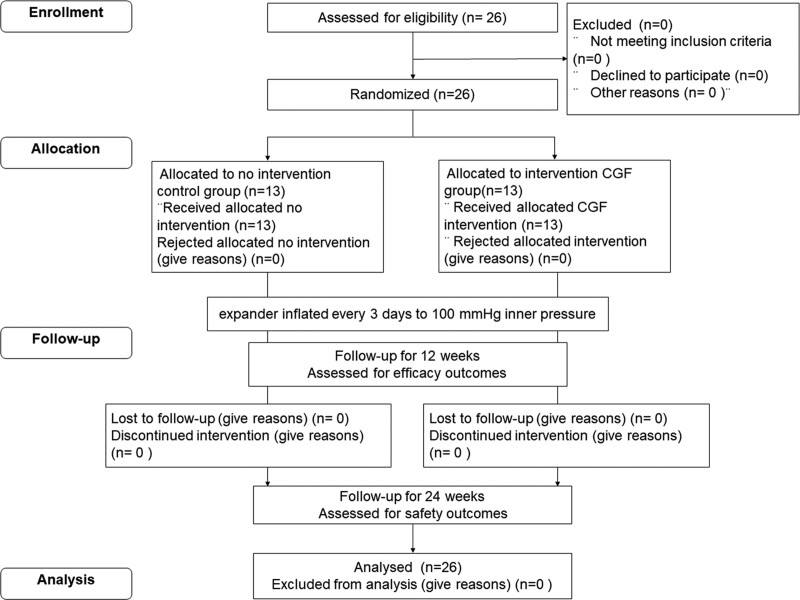

This single-center, prospective, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial was conducted at Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital. The intervention was conducted on expanded skin, which was injected intradermally with CGF or placebo (sterilized saline). The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram showing patient recruitment is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram of the participant recruitment and study flow.

Ethical approval was granted by the institutional ethics committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital and the trial was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient signed a written informed consent form before enrollment.

Subject Selection

Recruitment was performed from September of 2016 to September of 2018. Eligible patients were male or female patients aged 14 to 65 years, who underwent surgical implantation of an expander and required further expansion to complete reconstruction. Tissue expanders were implanted in all subjects by the same team of senior surgeons. The expander’s implanted site, size, and shape were designed according to the principles of tissue expansion.17 Expanded skin with infection, scarring, ulceration, or necrosis was excluded. Patients who had an expander implanted under the scalp, had severe illnesses or hematologic or infectious diseases, and smoked within than 3 months were also excluded.

Sample Size Determination

The probability of a type I error was α = 0.05 on one-sided testing, with 80% (1 − β = 0.8) power for comparisons between the CGF group and the control group. Based on our previous studies,8,9 assuming a 20% loss to follow-up, the final sample size was calculated as 13 patients per group, and we enrolled 26 patients in total.

Randomization and Blinding

Assignment to the CGF and control groups was determined by a simple randomization method, according to a computer-generated randomization schedule at a 1:1 ratio. The recruiting team randomized participants, and the conduct team performed the treatment. The investigator and participants were blinded during the trial.

Intervention

The CGF was prepared as according to our previously established method.18 Briefly, 9 mL of whole blood was collected into a heparin Vacutainer tube (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria). A Medifuge centrifugation device (Silfradent, Santa Sofia, Italy) was used to prepare the CGF using matching centrifugation with the following settings: 30 seconds of acceleration to 2700 rpm; 2700 rpm for 2 minutes; 2400 rpm for 4 minutes; 2700 rpm for 4 minutes; 3000 rpm for 3 minutes; and 36 seconds deceleration and rotation to stop.19 The blood was separated into platelet-containing plasma at the top and the erythrocyte layer and buffy coat at the bottom after centrifugation. [See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows photographs of the CGF treatment. (Left) Whole blood was separated through centrifugation, and 1.8 mL of CGF was harvested above the erythrocyte layer and buffy coat. (Right) CGF was injected intradermally into the pinched-up expanded skin area, http://links.lww.com/PRS/F962.] The supernatant plasma was discarded, and the residual plasma just above the buffy coat was collected to obtain 1.8 mL of CGF per tube.

Before treatment, a 10% volume of the total inflation was extracted. CGF was injected intradermally into the pinched-up skin (0.02 mL/cm2) (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, right, http://links.lww.com/PRS/F962), and the control group was injected in the same manner with saline. The treatments were repeated at 4 weeks and 8 weeks after the first treatment. All the procedures were performed by the same surgeon.

Inflation resumed 3 days after each treatment and was repeated every 3 days. Each inflation was stopped when the inner pressure reached 100 mmHg, which was measured by the inner pressure meter as reported previously,20 and the total inflation volume was recorded.

All participants underwent an efficacy assessment, including a measurement of skin thickness, total surface area, expansion index (EI), and subjective scores of the expanded skin texture, at baseline and 4 weeks, 8 weeks, and 12 weeks after the first treatment, and a safety assessment at 24 weeks after the first treatment.

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the change in skin thickness at 12 weeks after the first treatment. The secondary endpoints were the change in skin thickness (including the dermis and epidermis) at 4 and 8 weeks, the increments of surface area and EI of the expanded skin at 12 weeks, and subjective scores of the expanded skin texture after the first treatment. The safety assessment was performed at 24 weeks after the first treatment.

Efficacy Assessment

Expanded Skin Thickness

B-mode ultrasonography (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) with an 8- to 12-MHz linear-array probe was performed to measure the thicknesses of the expanded skin without invasion, as reported previously.8,9 Ultrasonographic images of the skin were measured using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) as follows: (1) epidermal thickness was defined as the distance between the air-epidermis echo band and the epidermis-dermis echo band, and (2) dermal thickness was defined as the distance between the epidermis-dermis echo band and the dermis-hypodermis echo band. The measurements were performed by an independent operator at eight equal intervals along the longitudinal axis of the expanded skin.

Expanded Skin Surface Area

The surface area of expanded skin was measured as the inflated area from the body surface using a three-dimensional scanner (Konica Minolta, Sakai Osaka, Japan) with RapidForm 2006 software (INUS Technology, Seoul, Republic of Korea), as reported previously.8

Expansion Index

The inflated volume at each visit was recorded. Because of the different maximum capacities of the patient expanders, we used the EI to measure the inflation efficiency of the expansion process, as reported previously.8,9 The EI was defined as the ratio of the total inflated volume (in milliliters) to the designed volume of the expander (in milliliters).

Subjective Scores of Expanded Skin Texture

A trained, blinded investigator evaluated the photographs of expanded skin at baseline and 12 weeks after the first treatment. Poorly regenerated skin was papery and pale, with stretch striae and telangiectasia.9 The improvement was assessed in skin texture at 12 weeks using the subjective scores scale that we previously reported,9 as were detailed. (See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows subjective scoring scale for evaluating expanded skin texture, http://links.lww.com/PRS/F963.)

Histologic Examination

Expanded skin specimens were harvested during flap transfer surgery and fixed with formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 6 μm. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) (G1120; Solarbio, Beijing, People’s Republic of China) staining and Masson trichrome (MT) (G1340; Solarbio) staining were performed for histologic examination. Differences in skin thickness were observed with HE staining in both groups, and collagen synthesis was evaluated using the collagen volume fraction (CVF) based on MT staining. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (BM0104; Boster, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China) staining was performed to evaluate cell proliferation and CD31 (BA2966; Boster) staining for vascularization in skin sections of both groups.

The stained images were captured using a light microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and Nikon DS-Ri2 digital camera with NIS Elements software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The mean values of the thickness of epidermis and dermis, and CVF, count of PCNA-positive proliferating cells and CD31-positive blood vessels, were calculated independently in five random high-power fields (HPFs).

Safety

Adverse events, including symptoms of erythema, pain, infection, and subcutaneous protuberance or nodule formation at the injection site that occurred during the follow-up period were recorded for the safety assessment.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The data were analyzed by D’Agostino-Pearson normality test. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM or median and interquartile range, depending on normality of data distribution, with 95% confidence intervals. Group differences were tested by repeated measures analysis or t test or Mann-Whitney nonparametric test. The differences between the baseline visit and each subsequent visit were tested by paired t test or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, and histology analysis result was tested by t test. Statistical significance was considered for values of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

From September of 2016 to February of 2019, a total of 26 patients were enrolled and assigned to either the control group or the CGF group. All patients underwent follow-up, and none were lost to follow-up. The subjects included 18 men and eight women, with an average age of 26.8 ± 1.7 years in the control group and 23.2 ± 1.7 years in the CGF group (–8.0 to 1.9 years; P = 0.112). The average duration of expander implantation was 2.1 ± 0.2 months in the control group and 2.4 ± 0.2 months in the CGF group (–0.6 to 7.2 months; P = 0.879). A summary of participant characteristics is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

| Control Group | CGF Group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 13 | 13 | |

| Mean age ± SEM, yr | 26.8 ± 1.7 | 23.2 ± 1.7 | 0.112 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 10 | 8 | — |

| Female | 3 | 5 | — |

| Mean BMI ± SEM, kg/m2 | 23.2 ± 1.1 | 22.5 ± 1.1 | 0.344 |

| Expander implantation site | |||

| Cervical | 7 | 5 | — |

| Chest | 2 | 3 | — |

| Dorsal | 2 | 3 | — |

| Facial | 2 | 2 | — |

| Mean expander implantation duration ± SD, mo | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 0.879 |

| Mean expansion index ± SEM | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.107 |

| Expanded surface area | |||

| Median | 193.8 | 149.5 | |

| IQR | 59.5–578.6 | 48.6–268.7 | 0.281 |

BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

Primary Outcome

Expanded Skin Thickness at 12 weeks

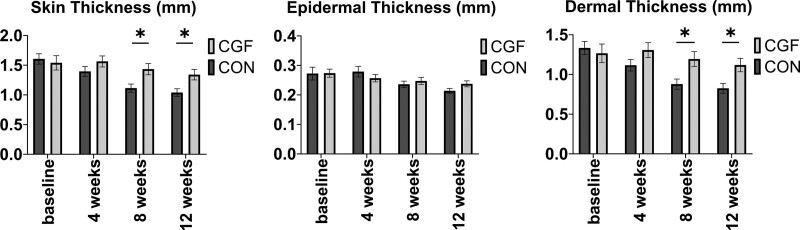

Both groups had similar baseline characteristics in terms of skin thickness (control group, 1.6 ± 0.1 mm; CGF group, 1.5 ± 0.1 mm; –0.3 to 0.5 mm; P = 0.987). At 12 weeks, patients in the CGF group (1.3 ± 0.1 mm) showed significantly thicker skin than those in the control group (1.0 ± 0.1 mm; −0.6 to 0.0 mm; P = 0.047) (Fig. 2, left, and Table 2). [See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which shows B-mode ultrasonography performed to measure the thickness of the expanded skin in control groups (above) and CGF group (below) at baseline and 12 weeks (yellow area, epidermis; red area, dermis). Scale bar = 2 mm, http://links.lww.com/PRS/F964.]

Fig. 2.

Comparison of (left) skin thickness, including (center) epidermis thickness and (right) dermis thickness, in the CGF group and control group. The results showed that the CGF group had significantly increased the skin thickness and dermal thickness at 8 weeks and 12 weeks compared with the control group. *P < 0.05.

Table 2.

Skin Thickness, Surface Area, and EI Parameters at Baseline and after 4, 8, and 12 Weeks

| Group | Control Group (n = 13) | CGF Group (n = 13) | P (CON vs. CGF) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/Median | SEM/IQR | P (Visit vs. V1) | Mean/Median | SEM/IQR | P (Visit vs. V1) | |||||

| Skin thickness, mm | ||||||||||

| V1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | — | — | 1.5 | 0.1 | — | — | 0.987 | ns |

| V2 | 1.4 | 0.1 | <0.001 | b | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.711 | ns | 0.569 | ns |

| V3 | 1.1 | 0.1 | <0.001 | b | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.167 | Ns | 0.047 | a |

| V4 | 1.0 | 0.1 | <0.001 | b | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.023 | a | 0.047 | a |

| Epidermal thickness, mm | ||||||||||

| V1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | — | — | 0.3 | 0.0 | — | — | >0.999 | ns |

| V2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.716 | ns | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.069 | ns | 0.792 | ns |

| V3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.129 | ns | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.035 | a | 0.935 | ns |

| V4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.016 | a | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.047 | a | 0.287 | ns |

| Dermal thickness, mm | ||||||||||

| V1 | 1.3 | 0.1 | — | — | 1.3 | 0.1 | — | — | 0.984 | ns |

| V2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | <0.001 | b | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.497 | ns | 0.400 | ns |

| V3 | 0.9 | 0.1 | <0.001 | b | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.294 | ns | 0.045 | a |

| V4 | 0.8 | 0.1 | <0.001 | b | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.079 | ns | 0.041 | a |

| Surface area | ||||||||||

| V1 | 198.0 | 59.5–578.6 | — | — | 149.5 | 48.6–268.7 | — | — | 0.281 | ns |

| V4 | 280.3 | 111.4–670.5 | 0.001 | b | 258.0 | 187.7–465.7 | <0.001 | b | 0.614 | ns |

| Increment of surface area | ||||||||||

| V4–V1 | 77.7 | 18.5 | — | — | 135.0 | 15.7 | — | — | 0.027 | a |

| EI | ||||||||||

| V1 | 1.5 | 0.2 | — | — | 1.2 | 0.1 | — | — | 0.107 | ns |

| V4 | 2.4 | 0.1 | <0.001 | b | 2.6 | 0.1 | <0.001 | b | 0.449 | ns |

| Increment of EI | ||||||||||

| V4–V1 | 0.9 | 0.1 | — | — | 1.4 | 0.2 | — | — | 0.030 | a |

IQR, interquartile range; V1, visit 1 (baseline); V2, visit 2 (4 weeks); ns, not significant (P > 0.05); V3, visit 3 (8 weeks); V4, visit 4 (12 weeks).

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

Secondary Outcomes

Expanded Skin Thickness at 4 and 8 Weeks

After 8 weeks, the CGF group (1.4 ± 0.1 mm) showed a significant increase in skin thickness compared with the control group (1.1 ± 0.1 mm; –0.6 to 0.0 mm; P = 0.047). Compared with the baseline, the skin thickness was sustained after CGF treatment at 4 weeks (1.6 ± 0.1 mm; −0.2 to 0.1 mm; P = 0. 711), 8 weeks (−0.1 to 0.3 mm; P = 0. 167), and 12 weeks (−0.0 to 0.4 mm; P = 0.023). However, the skin thickness decreased constantly over time in the control group at 4 weeks (1.4 ± 0.1 mm; 0.1 to 0.3 mm; P < 0.001), 8 weeks (0.3 to 0.7 mm; P < 0.001), and 12 weeks (0.4 to 0.8 mm; P < 0.001) (Table 2). [See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4, which shows comparison of the (above) epidermis, (center) dermis, and (below) skin thickness in the control group and CGF group throughout the follow-up period. The CGF group maintained skin thickness, whereas the thickness was constantly decreased in the control groups. Bar graph measurements are shown as mean with range. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, http://links.lww.com/PRS/F965.]

Notably, the dermis contributed to the increase in skin thickness, as there was no significant difference in the thickness of the epidermis (Fig. 2, center) based on ultrasonography measurements. The dermal thickness was increased in the CGF group compared with the control group (Fig. 2, right) (8 weeks, control group: 0.9 ± 0.1 mm; CGF group: 1.2 ± 0.1 mm; −0.6 to −0.0 mm; P = 0.045) (12 weeks: control group: 0.8 ± 0.1 mm; CGF group: 1.1 ± 0.1 mm; −0.6 to −0.0 mm; P = 0.041), which was consistent with the change in skin thickness (Table 2).

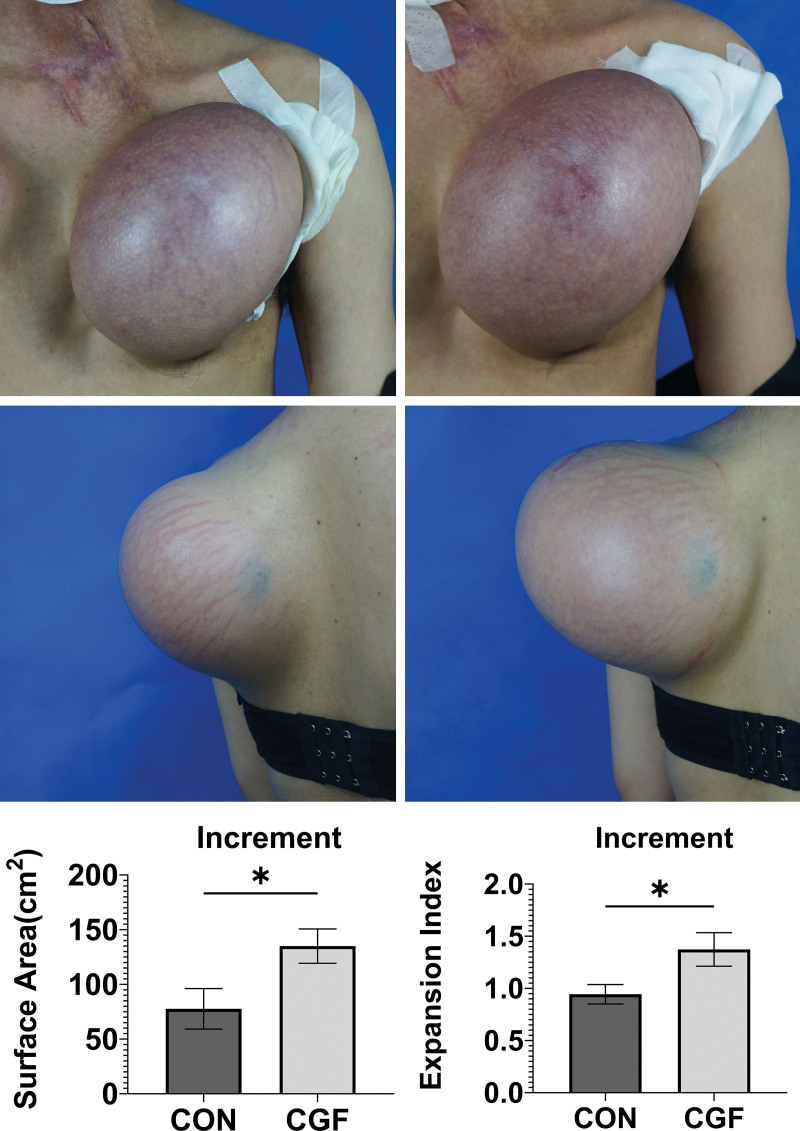

Surface Area of Expanded Skin

The increment in the expanded skin surface area was greater in the CGF group than in the control group at 12 weeks (CGF group, 135.0 ± 15.7 cm2; control group, 77.7 ± 18.5 cm2; 7.2 to 107.4 cm2; P = 0.027). Compared with the baseline, the surface area of expanded skin in the CGF group was significantly increased at 12 weeks [baseline, 149.5 cm2 (interquartile range, 48.6 to 268.7 cm2);12 weeks, 258.0 cm2 (interquartile range, 187.7 to 465.7 cm2); 62.6 cm2 to 187.7 cm2; P < 0.001] (Fig. 3, above, center, and below, left, and Table 2).

Fig. 3.

(Below) At 12 weeks, the increases in surface area and expansion index were greater in the CGF group (center) than in the control group (above). In addition, a case from the CGF group (center) showed that the stretch striae in the expanded skin were significantly improved at 12 weeks after treatment. *P < 0.05.

Expansion Index

At 12 weeks, the EI increment was greater in the CGF group than in the control group (CGF group, 1.4 ± 0.2; control group, 0.9 ± 0.1; 0.0 to 0.8; P = 0.030) (Fig. 3, below, left, and Table 2).

Skin Texture Evaluation

A greater improvement in skin texture was observed in the CGF group than in the control group (Fig. 4), including an increase in pale expanded skin (Fig. 4), center) and a reduction in the stretch striae of expanded skin (Fig. 3, center). There were more scores of “significantly improved” and “better than before” in the CGF group [grade 3, n = 2 (15.8%); grade 2, n = 4 (30.7%)] than in the control group [grade 3, n = 0 (0.0%); grade 2, n = 3 (23.0%)] (Fig. 4, below).

Fig. 4.

(Below) At 12 weeks, patients in the CGF group (center) showed better improvement than those in the control group (above) with regard to skin textures and color. A case from the CGF group (center) showed that the expanded skin had a reduced pale pattern and an increased ruddy pattern at 12 weeks after treatment.

Histologic Examination

HE staining showed that the epidermal and dermal layers were thicker in the CGF group than in the control group (epidermis: control, 49.5 ± 6.5 μm; CGF: 77.1 ± 9.7 μm; 3.51 to 51.9 μm; P = 0.027) (dermis: control, 2.4 ± 0.2 mm; CGF: 3.2 ± 0.3 mm; 0.22 to 1.48 mm; P = 0.010). [See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5, which shows representative HE-, MT-, CD31-, and PCNA-stained images of expanded skin in both groups. (Above) Compared with the control group, the CGF group had thicker skin with increasing epidermis and dermis layers. (Second row) The deposition of collagen fibers was increased in the CGF group with an organized distribution but decreased in the control group with a loose arrangement. The collagen volume fraction (CVF) results were consistent with the histologic images. (Third row) CD31-stained blood vessels and (below) PCNA-positive proliferating cells were increased in the CGF group. Scale bar (above) = 300 μm; second and third rows and below, scale bar = 100 μm. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, http://links.lww.com/PRS/F966.]

MT staining showed the presence of greater collagen deposition in the dermal layer in the CGF group, with organized collagen distribution, whereas the collagen fibers in the control group were loosely organized. The CVF results were consistent with the histologic images (control, 50.4 ± 4.7%/HPF; CGF, 62.4 ± 3.5%/HPF; 0.0% to 26.8%/HPF; P = 0.049).

Compared with the control group, the CGF group exhibited increased PCNA-positive proliferating cells (control, 32.5 ± 6.0/HPF; CGF, 58.7 ± 8.0/HPF; 5.3/HPF to 47.0/HPF; P = 0.016) and more CD31+ blood vessels (control, 14.3 ± 2.0/HPF; CGF, 25.8 ± 2.7/HPF; 4.5 to 18.5/HPF; P = 0.003) throughout the dermis.

Safety

After the injection, six participants (23%) showed temporary ecchymosis in the injection area; however, the symptoms disappeared within 1 week without sequelae. None of the participants experienced infectious or severe adverse events during the 24-week follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

This prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial demonstrated that combining mechanical stretching and autologous growth factor could promote skin growth in vivo. Compared with stem cell transplantation in promoting skin regeneration, as we previously reported,8,9 CGF, which was harvested by blood extraction, prevented invasive liposuction surgery and the risks of cell transplantation, and thus possessed better potential for future clinical use. Our results raise further questions regarding the application of CGF in skin regeneration under mechanical stretching, as addressed below.

Effect

CGF been administered as a clinical therapeutic agent in tissue repair and regeneration. Chronic wounds treated with CGF displayed significantly expedited wound closure, with fastened reepithelialization and a large area of granulation tissue in the wounds.19,21 CGF can improve the skin appearance and texture in aging skin by increasing the skin thickness.22,23 Moreover, CGF can promote the vascularization of transplanted tissue.24 No side effects of the application of CGF have been reported in these studies.

Our study showed that CGF can promote epithelialization and collagen deposition and increase capillary density, which favors vascularization, and skin thickening and expanding, in turn facilitating skin regeneration. CGF treatment improved the deterioration of skin texture during expansion. These results indicate that CGF treatment could be beneficial in managing tissue expansion.

CGF Preparation

Although PRP has been widely used in regenerative medicine, the application of PRP is controversial because of its unstable therapeutic efficacy. The lack of a standard preparation, including a single- or double-spinning approach, different activation methods, and even different centrifugation settings, yields different growth factor concentrations in the product of PRP.25,26

CGF preparation is a one-step harvesting protocol using a matching centrifugation device without additional manipulations.10 Therefore, CGF is a stable product that can be reliably reproduced for clinical applications.27 CGF is prepared with a variable-speed centrifugation process that switches between acceleration and deceleration. Alternate centrifugation provided more opportunities for platelet collisions with the centrifuge tube to release a greater amount of growth factor.28 Compared with PRP, CGF contains higher concentrations of transforming growth factor-beta type 1 (TGF-β1), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).29

Potential Mechanism

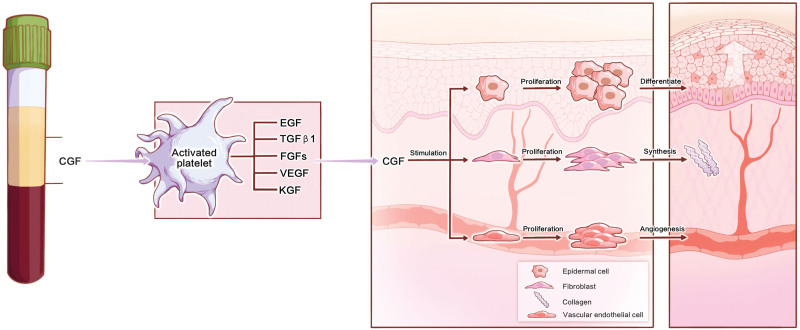

Studies reported that the expression of growth factors,30 such as VEGF, epidermal growth factor, bFGF, and TGF-β, and keratinocyte growth factor, was increased during expanded course.4,31 Both bFGF and VEGF contribute to enhance new vessel formation and maintain angiogenic signaling,32,33 whereas TGF-β1 is a potent profibrotic cytokine through which dermal fibroblasts regulate the extracellular matrix.34 Keratinocyte growth factor and epidermal growth factor can induce the proliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes.35,36 These growth factors have great potential in wound healing by promoting epithelialization, angiogenesis, and the synthesis of new extracellular matrix,20,31,37 which may be the mechanism of CGF treatment that promotes skin regeneration under stretching (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism of CGF treatment that promotes skin regeneration during the expansion course. CGF treatment could be delivered using multiple growth factors to increase epithelialization, collagen deposition, and neovascularization, leading to increase skin thickness and area, and in turn promoting skin regeneration.

Treatment with a single growth factor cannot be sufficiently effective.38 The simultaneous delivery of growth factors may mimic the natural course of skin regeneration under stretching, but the compatibility of multiple growth factors needs further investigation.38 As CGF is an autologous growth factor with a physiologic combination, it would seem reasonable to use CGF treatment in managing tissue expansion.

Limitations

The safety assessment demonstrated that CGF treatment facilitated the outcome of tissue expansion without increasing adverse events. However, there are some limitations related to CGF treatment in managing tissue expansion. In patients with poor general conditions, including those with chronic diseases and older patients, platelet quality hardly achieves the expected therapeutic effect.39,40 Repeated treatments are needed to meet the expected therapeutic effect of CGF. Further randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up durations are recommended.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates that CGF treatment can promote skin regeneration, such as increased thickness and area, during the expansion course. This study indicates that CGF treatment could be an adjuvant treatment for promoting skin regeneration in the management of skin expansion.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with regard to the publication of this article.

PATIENT CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This clinical trial was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81701917; 81971848), the Shanghai Pujiang Program (2019PJD024), the Two-hundred Talent (20191916), and the Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty (shslczdzk00901). The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution to this work by Drs. Kai Liu, Feng Xie, Tao Zan, Dong Han, and Bin Gu, who referred their patients for participation in this study. The authors also appreciate the technological support from the Core Facility of Basic Medical Sciences, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, and thank the American Journal Experts for editing the English language of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The first three authors contributed equally to this work and are co–first authors of this article.

This trial is registered under the name “Evaluation of the Effect of CGF in Promoting Mechaical Stretch-induced In Vivo Skin Regeneration,” ClinicalTrials.gov identification no. NCT03406143 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03406143).

Disclosure statements are at the end of this article, following the correspondence information.

Related digital media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSJournal.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neumann CG. The expansion of an area of skin by progressive distention of a subcutaneous balloon; use of the method for securing skin for subtotal reconstruction of the ear. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946) 1957;19:124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zollner AM, Holland MA, Honda KS, Gosain AK, Kuhl E. Growth on demand: reviewing the mechanobiology of stretched skin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2013;28:495–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeGoff L, Lecuit T. Mechanical forces and growth in animal tissues. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;8:a019232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Razzak MA, Hossain MS, Radzi ZB, Yahya NA, Czernuszka J, Rahman MT. Cellular and molecular responses to mechanical expansion of tissue. Front Physiol. 2016;7:540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang Y, Luan J, Zhang X. Accelerating tissue expansion by application of topical papaverine cream. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1166–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raposio E, Santi PL. Topical application of DMSO as an adjunct to tissue expansion for breast reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee P, Squier CA, Bardach J. Enhancement of tissue expansion by anticontractile agents. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:604–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou SB, Zhang GY, Xie Y, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation promotes mechanical stretch induced skin regeneration: a randomized phase I/II clinical trial. EBioMedicine 2016;13:356–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan PC, Chao PC, Cheng C, et al. A randomized, controlled clinical trial of autologous stromal vascular fraction cells transplantation to promote mechanical stretch-induced skin regeneration. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal AA. Evolution, current status and advances in application of platelet concentrate in periodontics and implantology. World J Clin Cases 2017;5:159–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Liu C, Wu B, et al. Effects of platelet-rich plasma on tissue expansion in rabbits. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacco L. Lecture. Presented at: International Academy of Implant Prosthesis and Osteoconnection. Sersale, Italy: April 12, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabatabaei F, Aghamohammadi Z, Tayebi L. In vitro and in vivo effects of concentrated growth factor on cells and tissues. J Biomed Mater Res A 2020;108:1338–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi L, Liu L, Hu Y, et al. Concentrated growth factor promotes gingival regeneration through the AKT/Wnt/beta-catenin and YAP signaling pathways. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2020;48:920–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchetti E, Mancini L, Bernardi S, et al. Evaluation of different autologous platelet concentrate biomaterials: morphological and biological comparisons and considerations. Materials (Basel) 2020;13:2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang YM, Huang XL, Chen G, Sheng LL, Li QF. Activated hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha pathway modulates early events in stretch-induced skin neovascularization via stromal cell-derived factor-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:996–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikkhah D, Bulstrode NW. Tissue expansion. In: Farhadieh RD, Bulstrode NW, Mehrara BJ, Cugno S, eds. Plastic Surgery: Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2022:56–67. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan PC, Zhang PQ, Xie Y, et al. Autologous concentrated growth factors combined with topical minoxidil for the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2021;23:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao QM, Gao J, Huang XX, Chen XP, Wang X. Concentrated growth factors extracted from blood plasma used to repair nasal septal mucosal defect after rhinoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020;44:511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheng L, Yang M, Du Z, Yang Y, Li Q. Transplantation of stromal vascular fraction as an alternative for accelerating tissue expansion. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kao CH. Use of concentrate growth factors gel or membrane in chronic wound healing: description of 18 cases. Int Wound J. 2020;17:158–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Chen X, Zhao Q, et al. Clinical observation of concentrated growth factor (CGF) improving periorbital wrinkles. Chin J Aesthet Plast Surg. 2018;29:402–405. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pamela RD. Topical growth factors for the treatment of facial photoaging: a clinical experience of eight cases. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:28–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Y, Jiang Y, Wang M, Tian W, Wang H. Concentrated growth factor enhanced fat graft survival: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:976–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chamata ES, Bartlett EL, Weir D, Rohrich RJ. Platelet-rich plasma: evolving role in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147:219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentile P, Cervelli V. Autologous platelet-rich plasma: guidelines in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:269e–270e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Wan Y, Lin Y, Jiang H. Considerations for clinical use of concentrated growth factor in maxillofacial regenerative medicine. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32:1316–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J, Jiang H. A comprehensive review of concentrated growth factors and their novel applications in facial reconstructive and regenerative medicine. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020;44:1047–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou R, Wang M, Zhang X, et al. Therapeutic effect of concentrated growth factor preparation on skin photoaging in a mouse model. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520962946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romani P, Valcarcel-Jimenez L, Frezza C, Dupont S. Crosstalk between mechanotransduction and metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:22–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding J, Lei L, Liu S, et al. Macrophages are necessary for skin regeneration during tissue expansion. J Transl Med. 2019;17:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veith AP, Henderson K, Spencer A, Sligar AD, Baker AB. Therapeutic strategies for enhancing angiogenesis in wound healing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;146:97–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melincovici CS, Bosca AB, Susman S, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF): key factor in normal and pathological angiogenesis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2018;59:455–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Batlle E, Massague J. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in immunity and cancer. Immunity 2019;50:924–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Werner S. Keratinocyte growth factor: a unique player in epithelial repair processes. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998;9:153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andasari V, Lu D, Swat M, et al. Computational model of wound healing: EGF secreted by fibroblasts promotes delayed re-epithelialization of epithelial keratinocytes. Integr Biol (Camb.) 2018;10:605–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng X, Yu Z, Song Y, et al. Hair follicle bulge-derived stem cells promote tissue regeneration during skin expansion. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;132:110805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonchar IV, Lipunov AR, Afanasov IM, Larina V, Faller AP, Kibardin AV. Platelet rich plasma and growth factors cocktails for diabetic foot ulcers treatment: state of art developments and future prospects. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian J, Cheng LH, Cui X, Lei XX, Tang JB, Cheng B. Application of standardized platelet-rich plasma in elderly patients with complex wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2019;27:268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anitua E, Prado R, Orive G. Allogeneic platelet-rich plasma: at the dawn of an off-the-shelf therapy? Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35:91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.