Abstract

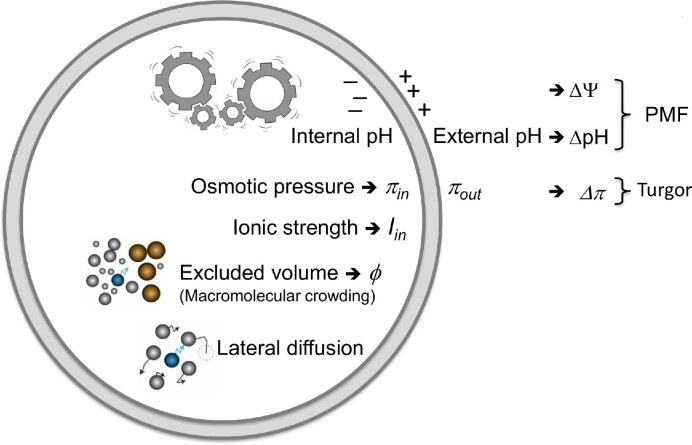

In living cells, the biochemical processes such as energy provision, molecule synthesis, gene expression, and cell division take place in a confined space where the internal chemical and physical conditions are different from those in dilute solutions. The concentrations of specific molecules and the specific reactions and interactions vary for different types of cells, but a number of factors are universal and kept within limits, which we refer to as physicochemical homeostasis. For instance, the internal pH of many cell types is kept within the range of 7.0 to 7.5, the fraction of macromolecules occupies 15%–20% of the cell volume (also known as macromolecular crowding) and the ionic strength is kept within limits to prevent salting-in or salting-out effects. In this article we summarize the generic physicochemical properties of the cytoplasm of bacteria, how they are connected to the energy status of the cell, and how they affect biological processes (Fig. 1). We describe how the internal pH and proton motive force are regulated, how the internal ionic strength is kept within limits, what the impact of macromolecular crowding is on the function of enzymes and the interaction between molecules, how cells regulate their volume (and turgor), and how the cytoplasm is structured. Physicochemical homeostasis is best understood in Escherichia coli, but pioneering studies have also been performed in lactic acid bacteria.

Keywords: physicochemical homeostasis, internal pH, ionic strength, excluded volume, macromolecular crowding, volume regulation, lateral diffusion, structure of cytoplasm

Physicochemical properties of the bacterial cytoplasm and their connection to the energy status of the cell.

Internal pH and proton motive force

Protons participate in numerous reactions and serve as a source of electrochemical energy (proton motive force, PMF, expressed in units of volt) to drive the synthesis of ATP and the transport of solutes across the cytoplasmic membrane. The proton motive force is composed of the membrane potential (ΔΨ, typically inside negative relative to the outside of the cell) and the pH gradient (ΔpH, typically inside alkaline relative to the outside). In equation:

|

(1) |

where 2.3RT/F equals 58 mV (at T = 298 K) and is abbreviated as Z; F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature. Since cells maintain their cytoplasmic pH around neutral, the magnitude of the pH gradient is largely determined by the external pH (Krulwich et al. 2011). Hence, at acidic pH, the ΔpH makes a larger contribution to the proton motive force than at neutral pH; the opposite pH dependence is generally observed for the ΔΨ, such that the proton motive force of neutralophilic bacteria is kept relatively constant in the pH range from 5 to 8. In addition, the internal pH changes when the PMF is used as an energy source to drive endergonic reactions. Cells use different transport mechanisms to interconvert the ΔΨ and ΔpH to simultaneously maintain a relatively constant PMF and internal pH. Key regulators of bacterial pH homeostasis are Na+/H+ and K+/H+ antiporters, the proton pumping enzymes (electron transport components in respiratory bacteria, F0F1-ATPase in lactic acid bacteria), and metabolite decarboxylation pathways (Fig. 2).

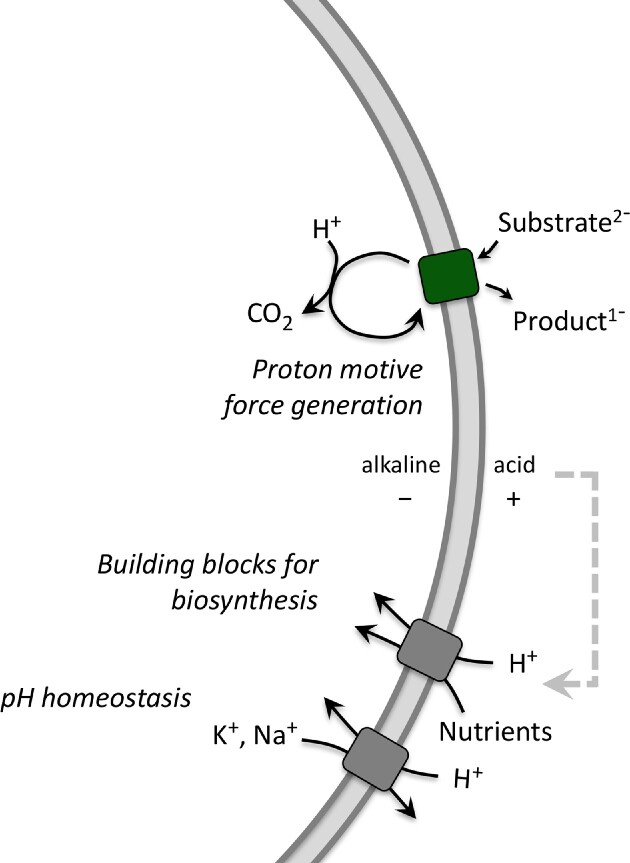

Figure 2.

Proton motive force generation by substrate decarboxylation, and utilization of the PMF for nutrient uptake (building blocks for biosynthesis) and pH homeostasis.

Figure 1.

Inter-connectedness of energy status and physicochemical parameters of bacterial cell.

The buffering capacity of the cytoplasm is important in absorbing pH fluctuations. Bacteria like Escherichia coli and Lactococcus lactis have a cytoplasmic volume of ∼1 fL, and the number of free protons at pH 7.2 is only about 10. A few protons entering or leaving the cell would have a large impact on the internal pH if there would not be sufficient buffering capacity (e.g. inorganic and organic phosphates), which in the case of L. lactis is in the range of 100 mM of (organic) phosphates (Levering et al. 2012). Proton-sensing ion/H+ antiporters acidify the cytoplasm by exporting K+ or Na+ in exchange for protons when the internal pH gets too high (Krulwich et al. 2011). Upregulation and or activation of the components of proton-pumping respiratory chains (respiratory bacteria), the F0F1-ATPase (fermentative bacteria), or decarboxylation pathways (next paragraph) prevent the internal pH from becoming too low (Krulwich et al. 2011). Bacteria typically have multiple transport systems with different pH sensitivities to regulate the internal pH (Masrati et al. 2018, Winkelmann et al. 2022).

The free energy released in the decarboxylation of metabolites is around 20 kJ/mol (Dimroth and Schink 1998), which is too little to directly synthesize ATP from ADP plus inorganic phosphate by substrate-level phosphorylation. For comparison, the Gibbs free energy change for ATP synthesis under standard conditions (ΔGo′) is around 31 kJ/mol (or ∼12 kBT; kB is the Boltzmann constant; T is the absolute temperature). Importantly, the free energy change from decarboxylation reactions can be stored in the form of a proton motive force, which subsequently can be used by F0F1-ATP synthase to make ATP. Depending on the species, the F0F1-ATP synthase uses three to five protons to synthesize one molecule of ATP (Ferguson 2010). The PMF for ATP synthesis can be smaller for enzymes with a larger H+/ATP stoichiometry (n). In equation:

|

(2) |

where ΔGATP is the phosphorylation potential and F is the Faraday constant. The proton motive force can also be used to drive the transport of nutrients and ions in and out of the cell as shown in Fig. 2.

How does a decarboxylation reaction lead to the generation of a proton motive force? By definition, the substrate and decarboxylation product carry a different net charge, and a ΔΨ is generated when an antiporter exchanges these molecules (Anantharam et al. 1989; Poolman et al. 1991 ; Salema et al. 1994, Romano et al. 2013). Moreover, the chemistry of the decarboxylation reaction requires a proton, and thus the internal pH is increased (and a ΔpH is formed) (Fig. 2). Thus, the equivalent of 1 proton is pumped per molecule decarboxylated, which corresponds to ⅓ to ⅕ of ATP (see Eq. 2). Bacterial amino acid decarboxylases have remarkably low pH optima (Gale 1946, Sa et al. 2015), and their activity increases when the internal pH drops due to enhanced proton influx. Hence, the enzymes have a built-in self-regulatory mechanism to deal with lower pH values and thus directly (pH-dependent decarboxylation) contribute to pH homeostasis (Fig. 2). An overview of demonstrated decarboxylation pathways is given in Sikkema et al. 2019; they are found in both respiratory and fermentative bacteria and play a prominent role in the physiology of lactic acid bacteria (e.g. acid stress response, production of biogenic amines).

Ionic strength

The ionic strength of a cell is the effective (and not total) ion concentration of the cytoplasm, expressed in molar unit (M). In equation:

|

(3) |

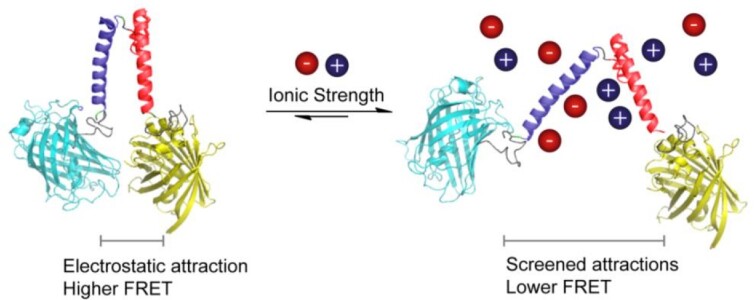

where i is the ion identification number, z is the charge of the ion, and c is the concentration (mol/l) of free ion. The ionic strength screens electrostatic interactions of (macro)molecules and is used to tune enzyme activity and gate membrane functions (vide infra). The actual ionic strength of the cell is typically not known because a large fraction of the ions are bound to macromolecules. The vast majority of prokaryotes have an overall anionic proteome (Schavemaker et al. 2017), and together with the nucleic acids, they bind a large fraction of the cations of the cell; the fraction of bound and free ions is difficult to discriminate. The most abundant cations are K+ and Mg2+, but halophiles can also have a high concentration of Na+. The ionic strength determines the structure of intrinsically disordered proteins (Konig et al. 2015), the activity of enzymes (Norby and Esmann 1997), protein aggregation (Marek et al. 2012), phase separations (Elbaum-Garfinkle et al. 2015), protein binding to (poly)nucleic acids (Record et al. 1978), and many other processes. Hence, a given cell maintains the ionic strength within limits, but the actual amounts of ions vary a lot when individual organisms are compared. For instance, the reported concentrations of K+ in E. coli, L. lactis, and Haloferax volcanii are ∼0.2, 0.8, and 2.1 M, respectively (Schavemaker et al. 2017). In recent years, we have developed fluorescence-based sensors to determine the actual ionic strength of bacteria and mammalian cells (Liu et al. 2017b) (Fig. 3). These probes allow observation of spatiotemporal changes in the ionic strength in the hundreds of millimolar range at the single-cell level, and they have been used to determine how the internal ionic strength of cells adjusts in response to osmotic challenges (Liu et al. 2019).

Figure 3.

Design of ionic strength sensors and sensing concept. An increase in ionic strength screens the electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged α-helices (“+” and “−” helix, respectively), which lowers the FRET signal. Taken from Liu et al. 2017b.

The ionic strength governs the cell volume by activating specific ion channels and solute transporters (Biemans-Oldehinkel et al. 2006, Syeda et al. 2016). The internal ionic strength can increase or decrease due to, for example, abrupt changes in medium osmolarity, and fluctuations with intracellular events such as metabolite synthesis. Osmoregulatory transporters are activated by an increase in internal ionic strength or specific ion concentration when cells are exposed to an osmotic upshift (Biemans-Oldehinkel et al. 2006, Perez et al. 2011, Wood 2011, Culham et al. 2016, Sikkema et al. 2020). These transporters prevent cells from plasmolyzing by accumulating large amounts of compatible solutes, such as glycine betaine, when they are confronted with an osmotic upshift (vide infra). Excessive internal ionic strength is mitigated in bacteria like E. coli by replacing ions (mostly K+) by neutral or zwitterionic compatible solutes such as trehalose, proline, or glycine betaine, thereby maintaining the osmotic pressure and ability to regulate the cytoplasmic volume (Dinnbier et al. 1988, Buda et al. 2016, Pliotas et al. 2017).

Macromolecular crowding

In bacteria, proteins make up the majority of the cell’s macromolecules (∼55% w/w) and together with ribosomal RNA (∼15% w/w) they are the most space-consuming molecules (Milo and Philips 2015). They occupy macromolecular volume fractions (Φ) in the range of 0.13 to 0.24, depending on the growth conditions (Zimmerman and Trach 1991; Cayley and Record 2004, Konopka et al. 2009, Boersma et al. 2015, Liu et al. 2019). The high macromolecular crowding of a cell makes the kinetics of reactions and equilibria of interactions different from those in dilute aqueous media.

What is macromolecular crowding? A macromolecule experiences a reduced available volume when it is present in a highly crowded environment, that is, when compared to, for instance, a dilute buffer in which biochemical reactions are typically analyzed. The reduced volume due to the presence of other “crowders” is known as the excluded volume (Minton 1981). Because the macromolecule and the surrounding crowding macromolecules cannot interpenetrate, this gives rise to steric repulsion and reduced translational degrees of freedom. Placing an extra macromolecule in such an environment gives rise to a configurational entropic penalty. Hence, any reduction in volume of such a macromolecule (e.g. upon folding) would increase the entropy and thus decrease its free energy (Minton 1981, Zimmerman and Minton 1993). And thus, a high excluded volume can enhance the folding of a molecule, the oligomerization of proteins, and the condensing of DNA (De Vries 2010; Kim et al. 2011, van den Berg et al. 2017). The impact of the configurational entropic effects on the conformation of proteins has been used to design fluorescence-based crowding sensors (Fig. 4). When the crowding (excluded volume) increases, the sensor takes on a more compact shape, which leads to increased resonance energy transfer (higher FRET) from cerulean (CFP) to citrine (YFP).

Figure 4.

Design of crowding sensor and sensing concept. A reduction in volume of the sensor by increased macromolecular crowding increases the entropy and thus decreases its free energy, which is observed as increased FRET between the fluorescent proteins CFP and YFP. Taken from Boersma et al. 2015.

The (hard-core) steric repulsions between macromolecules in the crowded cytoplasm are universal, nonspecific interactions that occur in any cell. They are not the only type of interaction a macromolecule experiences, which can either be repulsive or attractive. These so-called soft interactions will not be discussed here, but obviously they also play a role in the activity of an enzyme or macromolecule in the cytoplasm (Schavemaker et al. 2017, van den Berg et al. 2017, Speer et al. 2022). The soft interactions can enhance or attenuate the effect of excluded volume.

Why is the crowding in the cytoplasm universally very high? A high crowding (high enzyme concentrations) speeds up reactions rates, and allows processes to occur fast, and, for instance, enables bacteria to grow with doubling times below one hour. But there is an optimum to the crowding, because too high volume fractions slow down diffusion-limited reactions (Schavemaker et al. 2018). Pang and Lercher 2023 have found by computational modeling that protein synthesis, involving the interaction of large macromolecules (e.g. tRNA and mRNA with ribosomes), is more hindered by a high crowding than metabolism (diffusion of small molecules to active site of enzymes). (Micro)organisms, studied to date, have macromolecular volumes in the range of 0.15–0.20, which apparently is the optimum to achieve maximal reaction rates without diffusion becoming a limiting factor.

Turgor and volume regulation

Cell turgor (ΔΠ) is the hydrostatic pressure difference that balances the difference in internal and external osmolyte concentration (Fig. 5, left). In equation:

Figure 5.

Osmotic challenges and changes in the physicochemistry of the cell. Hypertonicity leads to cell shrinkage and a lowering of the turgor (Δπ); cells plasmolyze when Δπ is zero. During plasmolysis, the cell membrane shrinks away from the cell wall, leading to the collapse of the cytoplasm. The effect of hypertonicity on other physicochemical parameters is indicated in the top right of the figure. Hypotonicity leads to water uptake and swelling of cells, which increases Δπ and ultimately leads to cell lyses. Bottom right: Cryo-EM map of the ABC transporter OpuA at high salt in the presence of cyclic-di-AMP; taken from Sikkema et al. 2020. OpuA accumulates the compatible solute glycine betaine to (sub)molar levels, which counteracts the effect of hypertonic stress.

|

(4) |

in which Vw is the partial molal volume of water, “a” is the water activity, “c” is the total osmolyte concentration, and the subscripts “in” and “out” refer to inside and outside of the cell, respectively (Poolman et al. 2002). A cell plasmolyzes when ΔΠ becomes zero (Fig. 5). Although cell turgor is required for the expansion of the cell wall, there is little information on what the lower limit of turgor should be before cell growth ceases. Depending upon the species, a bacterial cell may develop several to a few tens of atmospheres of pressure across the cell envelope. For a given organism, cell turgor will vary in response to changes in external osmolality. In E. coli, the turgor decreases from ∼3 to 0.5 atm when the osmolality of the growth medium is increased from 0.03 to >0.5 osm/kg (Cayley et al. 2000). Although a turgor of 0.5 atm may be sufficient to sustain growth of E. coli, it is possible that the lower limit of turgor of Gram-positive bacteria, with their generally thicker cell wall, is much higher. The turgor of Lactococcus lactis and Listeria monocytogenes can be as high as 20 atm (Mika et al. 2010, 2014, Schavemaker et al. 2018, Tran et al. 2021).

The turgor decreases when cells are confronted with hypertonic conditions (or an osmotic upshift). Under these conditions, the cytoplasmic volume decreases, the ionic strength and crowding increase, and the internal pH decreases (Fig. 5, top right). Cells restore the internal physicochemical conditions by activating (gating) specific transport proteins that accumulate large amounts of compatible solutes, which are small organic molecules that are accumulated or synthesized by (micro)organisms to counteract the detrimental effects of osmotic stress; examples are glycine betaine, carnitine, proline, and trehalose (for reviews: Poolman et al. 2002; Wood 2011). Various osmoregulatory mechanisms have been described; below we focus on the sensing and response mechanism of the ATP-binding cassette transporter OpuA of L. lactis (Fig. 5, bottom right), which is one of the best-understood osmoregulatory transport proteins.

OpuA is gated by ionic strength. Upon osmotic upshift, the volume of the cell decreases and the ionic strength increases, which activates OpuA, and large amounts of glycine betaine are taken up (Biemans-Oldehinkel et al. 2006). Passive influx of water follows the accumulation of glycine betaine, and consequently, the volume of the cell increases and the ionic strength decreases. When the volume has been restored, the transporter is switched off. For long it was thought that ionic strength gating was the only mechanism by which the activity of OpuA is controlled, but recently we showed that the 2nd messenger cyclic-di-AMP acts as a backstop of the protein to prevent rampant accumulation of glycine betaine (Sikkema et al. 2020).

Molecule diffusion and structure of cytoplasm

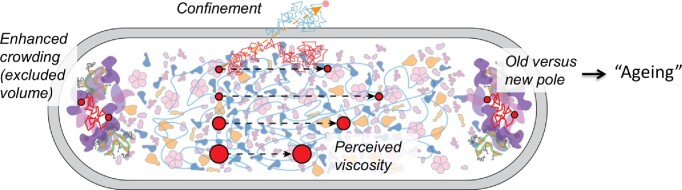

The cytoplasm is highly crowded and diverse in molecular composition, and many components are not uniformly distributed throughout the cell (Fig. 6). For instance, the chromosome and nucleoid-binding proteins localize in the cell center (Chai et al. 2014, Wu et al. 2019), the polysomes localize at the poles and cytoplasmic periphery (Bakshi et al. 2012, 2015, Chai et al. 2014), and aggregated or misfolded proteins localize at the cell poles (Winkler et al. 2010, Coguel et al. 2013; Schramm et al. 2020). The physical state (fluidity, viscosity) of the cytoplasm is dependent on metabolic activity, such as the availability of ATP (Parry et al. 2014). Natively disordered proteins and RNA molecules can undergo phase separation to form condensates, which are membraneless organelles involved in a wide range of cellular processes (Wei et al. 2020, Alberti and Hyman 2021). Phase-separated liquid droplets or biomolecular condensates have been pioneered in mammalian cells, but they are also found in the cytoplasm of microorganisms (van Gijtenbeek et al. 2016, Guilhas et al. 2020, Jin et al. 2021, Babl et al. 2022). They are metastable structures, where certain macromolecules partition and others are excluded.

Figure 6.

Structure of E. coli cytoplasm and impact of perceived viscosity on the lateral diffusion of proteins (red particles). The schematic also shows enhanced crowding at the poles, the impact of confinement on molecule diffusion, and the fluidization of the cytoplasm by metabolic activity, which are determining factors of the structure and dynamics of the cytoplasm. Modified after Smigiel et al. 2022.

Despite the apparent organization of the cytoplasm, individual molecules move around (diffuse laterally), which allows proteins and nucleic acids to sample different states. The lateral diffusion of molecules does not require work but plays a crucial role in the functioning of biochemical processes and provides meaning to the concept of entropy (Schavemaker et al. 2018). The mobility of molecules is expressed in the diffusion coefficient (D). For molecules in dilute solution we can get an estimate of D from the Stokes–Einstein equation:

|

(5) |

Here D is the diffusion coefficient, kB is the Boltzmann constant, R is the Stokes radius of the molecule, T is the absolute temperature, and η(T) is the viscosity at temperature T. Importantly, the macromolecular crowding experienced by a protein and thus the diffusion coefficient are dependent on its own molecular weight (Smigiel et al. 2022). Hence, smaller molecules are hindered less by the crowdedness than bigger ones. This so-called perceived macromolecular viscosity is not spatially uniform, and proteins diffuse faster in the cell center than in the pole regions of E. coli (Mantovanelli et al. 2023). Furthermore, diffusion in the old pole is slower than in the new pole, which may relate to the aging of bacteria (Fig. 6). Similar but less extensive observations have been made in L. monocytogenes (Tran et al. 2023). That diffusion is important for the proper functioning of bacteria is without question. However, the relation between reaction rates, diffusion coefficients, and protein concentrations is complex, and the relation between diffusion coefficient, excluded volume, and the physical state of the cytoplasm is poorly understood (Schavemaker et al. 2018, Aberg and Poolman 2021).

In conclusion

We have summarized the main physicochemical parameters that are important for the functioning of any microorganism, and these should be taken into account when redesigning a cell or exploiting a bacterium for productivity. The physicochemical parameters are interconnected, as can be seen, for example, when a cell’s volume decreases with osmotic upshift (Fig. 5). Cells have evolved regulatory mechanisms to enable physicochemical homeostasis.

Conflicts of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

The research was funded by an ERC Advanced grant “ABCVolume” (grant number 670578) and the NWO National Science Program “The limits to growth” (grant number NWA.1292.19.170).

References

- Aberg C, Poolman B. Glass-like characteristics of intracellular motion in human cells. Biophys J. 2021;120:2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert S, Hyman AA. Biomolecular condensates at the nexus of cellular stress, protein aggregation disease and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam V, Allison MJ, Maloney PC. Oxalate:formate exchange. The basis for energy coupling in Oxalobacter. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babl L, Giacomelli G, Ramm Bet al. CTP-controlled liquid–liquid phase separation of ParB. J Mol Biol. 2022;434:167401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi S, Choi H, Weisshaar JC. The spatial biology of transcription and translation in rapidly growing Escherichia coli. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6:636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi S, Siryaporn A, Goulian Met al. Superresolution imaging of ribosomes and RNA polymerase in live Escherichia coli cells. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemans-Oldehinkel E, Mahmood NA, Poolman B. A sensor for intracellular ionic strength. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma AJ, Zuhorn I, Poolman B. A sensor for quantification of macromolecular crowding in living cells. Nature Meth. 2015;12:227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buda R, Liu Y, Yang Jet al. Dynamics of Escherichia coli’s passive response to a sudden decrease in external osmolarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayley DS, Guttman HJ, Record MT. Biophysical characterization of changes in amounts and activity of Escherichia coli cell and compartment water and turgor pressure in response to osmotic stress. Biophys J. 2000;78:1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayley S, Record MT. Large changes in cytoplasmic biopolymer concentration with osmolality indicate that macromolecular crowding may regulate protein–DNA interactions and growth rate in osmotically stressed Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Recognit. 2004;17:488–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Q, Singh B, Peisker Ket al. Organization of ribosomes and nucleoids in Escherichia coli cells during growth and in quiescence. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:11342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquel AS, Jacob JP, Primet Met al. Localization of protein aggregation in Escherichia coli is governed by diffusion and nucleoid macromolecular crowding effect. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1003038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culham DE, Shkel IA, Record MTet al. Contributions of coulombic and Hofmeister effects to the osmotic activation of Escherichia coli transporter ProP. Biochem. 2016;55:1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries R. DNA condensation in bacteria: interplay between macromolecular crowding and nucleoid proteins. Biochimie. 2010;92:1715–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth P, Schink B. Energy conservation in the decarboxylation of dicarboxylic acids by fermenting bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1998;170:69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnbier U, Limpinsel E, Schmid Ret al. Transient accumulation of potassium-glutamate and its replacement by trehalose during adapatation of growing Escherichia coli K-12 to elevated sodium chloride concentrations. Arch Microbiol. 1988;150:348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Kim Y, Szczepaniak Ket al. The disordered P granule protein LAF-1 drives phase separation into droplets with tunable viscosity and dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:7189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SJ. ATP synthase: from sequence to ring size to the P/O ratio. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale EF. The bacterial amino acid decarboxylases. Adv Enzymol. 1946;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- Guilhas B, Walter JC, Rech Jet al. ATP-driven separation of liquid phase condensates in bacteria. Mol Cell. 2020;79:293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Lee JE, Schaefer Cet al. Membraneless organelles formed by liquid-liquid phase separation increase bacterial fitness. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabh2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Backman V, Szleifer I. Crowding-induced structural alterations of random-loop chromosome model. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;106:168102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig I, Zarrine-Afsar A, Aznauryan Met al. Single-molecule spectroscopy of protein conformational dynamics in live eukaryotic cells. Nat Meth. 2015;12:773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka MC, Sochacki KA, Bratton BPet al. Cytoplasmic protein mobility in osmotically stressed Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krulwich TA, Sachs G, Padan E. Molecular aspects of bacterial pH sensing and homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levering J, Musters MW, Bekker Met al. Role of phosphate in the central metabolism of two lactic acid bacteria—a comparative systems biology approach. FEBS J. 2012;229:1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Åberg C, van Eerden FJet al. Design and properties of genetically encoded probes for sensing macromolecular crowding. Biophys J. 2017a;112:1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Poolman B, Boersma AJ. Ionic strength sensing in living cells. ACS Chem Biol. 2017b;12:2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Hasrat Z, Poolman Bet al. Decreased effective macromolecular crowding in Escherichia coli adapted to hyperosmotic stress. J Bacteriol. 2019;201:e00708–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovanelli L, Linnik DS, Punter Met al. Simulation-based Reconstructed Diffusion unveils the effect of aging on protein diffusion in Escherichia coli (preprint). Biophysics. 2023. 10.1101/2023.04.10.536329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek PJ, Patsalo V, Green DFet al. Ionic strength effects on amyloid formation by amylin are a complicated interplay among Debye screening, ion selectivity, and Hofmeister effects. Biochemistry. 2012;51:8478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masrati G, Dwivedi M, Rimon Aet al. Broad phylogenetic analysis of cation/proton antiporters reveals transport determinants. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mika JT, Schavemaker PE, Krasnikov Vet al. Impact of osmotic stress on protein diffusion in Lactococcus lactis.Mol Microbiol. 2014;94:857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mika JT, van den Bogaart G, Veenhoff Let al. Molecular sieving properties of the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli and consequences of osmotic stress. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milo R, Phillips R. Cell Biology by the Numbers. New York: Garland Science, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Minton AP. Excluded volume as a determinant of macromolecular structure and reactivity. Biopolymers. 1981;20:2093. [Google Scholar]

- Norby JG, Esmann M. The effect of ionic strength and specific anions on substrate binding and hydrolytic activities of Na,K-ATPase. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang TY, Lercher MJ. Optimal density of bacterial cells. PLOS Comput Biol. 2023;19:e1011177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry BR, Surovtsev IV, Cabeen MTet al. The bacterial cytoplasm has glass-like properties and Is fluidized by metabolic activity. Cell. 2014;156:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C, Khafizov K, Forrest LRet al. The role of trimerization in the osmoregulated betaine transporter BetP. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliotas C, Grayer SC, Ekkerman Set al. Adenosine monophosphate binding stabilizes the KTN domain of the Shewanella denitrificans Kef potassium efflux system. Biochem. 2017;56:4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poolman B, Blount P, Folgering Jet al. How do membrane proteins sense water stress?. Molec Microbiol. 2002;44:889–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poolman B, Molenaar D, Smid EJet al. Malolactic fermentation: electrogenic malate uptake and malate/lactate antiport generate metabolic energy. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Record MT, Anderson CF, Lohman TM. Thermodynamic analysis of ion effects on the binding and conformational equilibria of proteins and nucleic acids: the roles of ion association or release, screening, and ion effects on water activity. Q Rev Biophys. 1978;11:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano A, Trip H, Lolkema JSet al. Three-component lysine/ornithine decarboxylation system in Lactobacillus saerimneri. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa HD, Park JY, Jeong SJet al. Characterization of glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) from lactobacillus sakei A156 isolated from Jeot-gal. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;25:696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salema M, Poolman B, Lolkema JSet al. Uniport of monoanionic L-malate in membrane vesicles from Leuconostoc oenos. Eur J Biochem. 1994;225:289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schavemaker PE, Boersma AJ, Poolman B. How important is protein diffusion in prokaryotes?. Front Mol Biosci. 2018;5:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schavemaker PE, Śmigiel WM, Poolman B. Ribosome surface properties may impose limits on the nature of the cytoplasmic proteome. Elife. 2017;6:e30084. 10.7554/eLife.30084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm FD, Schroeder K, Jonas K. Protein aggregation in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2020;44:54–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema HR, Gaastra BF, Pols Tet al. Cell fueling and metabolic energy conservation in synthetic cells. ChemBioChem. 2019;20:2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema HR, Rheinberger J, de Boer Met al. Gating by ionic strength and safety check by cyclic-di-AMP in the ABC transporter OpuA. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabd7697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smigiel WM, Lefrancois P, Poolman B. Physicochemical considerations for bottom-up synthetic biology. Emerg Top Life Sci. 2019;3:445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Śmigiel WM, Mantovanelli L, Linnik DSet al. Protein diffusion in Escherichia coli cytoplasm scales with the mass of the complexes and is location dependent. Science Adv. 2022;8:eabo5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer SL, Stewart CJ, Sapir Let al. Macromolecular crowding is more than hard-core repulsions. Annu Rev Biophys. 2022;51:267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer J, Pielak G, Poolman B. Emergence of life: physical chemistry changes the paradigm. Biol Direct. 2015;10:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syeda R, Qiu Z, Dubin AEet al. LRRC8 proteins form volume-regulated anion channels that sense ionic strength. Cell. 2016;164:499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran BM, Linnik D, Punter CMet al. Super-resolving microscopy reveals the localizations and movement dynamics of stressosome proteins in Listeria monocytogenes.Commun Biol. 2023;6:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran M, Prabha H, Iyer Aet al. Protein diffusion in the cytoplasm of Listeria monocytogenes is maintained during osmotic stress. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:640149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg J, Boersma AJ, Poolman B. Microorganisms maintain crowding homeostasis. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gijtenbeek LA, Robinson A, van Oijen AMet al. On the spatial organization of mRNA, plasmids and ribosomes in a bacterial host overexpressing membrane proteins. PLos Genet. 2016;12:e1006523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei SP, Qian ZG, Hu CFet al. Formation and functionalization of membraneless compartments in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16:1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann I, Uzdavinys P, Kenney IMet al. Crystal structure of the Na+/H+ antiporter NhaA at active pH reveals the mechanistic basis for pH sensing. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler J, Seybert A, König Let al. Quantitative and spatio-temporal features of protein aggregation in Escherichia coli and consequences on protein quality control and cellular ageing. EMBO J. 2010;29:910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J. Bacterial osmoregulation: a paradigm for the study of cellular homeostasis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Swain P, Kuijpers Let al. Cell boundary confinement sets the size and position of the E. coli chromosome. Curr Biol. 2019;29:2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman SB, Minton AP. Macromolecular crowding: biochemical, biophysical, and physiological consequences. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1993;22:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman SB, Trach SO. Estimation of macromolecule concentrations and excluded volume effects for the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]