Abstract

The pathogenic fungus Candida albicans harbors three histidine kinase genes called CaSLN1, CaNIK1, and CaHK1. The disruption of any one of these three genes impaired the hyphal formation and attenuated the virulence of C. albicans in a mouse systemic candidiasis model. The effects of the disruption on hyphal formation and virulence were most severe in the cahk1Δ null mutants. Although the double disruption of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1 was impossible, further deletion of CaSLN1 or CaNIK1 in the cahk1Δ null mutants partially restored the serum-induced hypha-forming ability and virulence. When incubated with radiolabelled ATP, the recombinant CaSln1 and CaNik1 proteins, which contained their own kinase and response regulator domains, were autophosphorylated, whereas CaHk1p was not. These results imply that in C. albicans, CaSLN1 and CaNIK1 function upstream of CaHK1 but are in distinct signal transmission pathways.

As in bacteria, eukaryotic cells harbor a histidine kinase osmosensing mechanism to adapt to osmotic changes. Sln1p of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is one of a family of two-component regulators and carries both histidine kinase and response regulator domains (14, 18). Under normal conditions (low osmolarity), Sln1p autophosphorylates a specific histidine in the kinase domain. The phosphate moiety on this histidine is transferred to a certain aspartic acid in the response regulator domain, then to Ypd1p, and further to Ssk1p to keep Hog1p mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activity turned off (4, 14, 19). Under high-osmolarity conditions, the autokinase activity of ScSln1p is turned off, which leads to the activation of Hog1p MAP kinase and the transcription of a family of osmoresponse genes, including that of glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD1) (1, 4, 14, 19). Besides affecting the MAP kinase cascade, the activity of Sln7p, which mediates oxidative stress and is required for MCM1-dependent gene expression, is also regulated by a phosphorelay from Ypd1p (13). Because a mutation of either the phosphorylating histidine or the receiver aspartic acid of Sln1p is lethal, the phosphorelay from Sln1p is essential for the growth of S. cerevisiae at low osmolarity (14).

Unlike S. cerevisiae, the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans harbors three putative histidine kinase genes called CaSLN1, CaNIK1, and CaHK1 (3, 6, 16, 22). Although CaSLN1 functionally complements an S. cerevisiae sln1Δ mutation, disruption of SLN1 in C. albicans does not alter viability and only slightly affects the tolerance of osmotic stresses (16). CaNIK1 is the C. albicans homolog of the Neurospora crassa NIK1 gene, which has been shown to be required for osmotolerance (2). The deletion of NIK1 in C. albicans, however, caused a defect in hyphal formation (3) and reduced the efficiency of high-frequency phenotypic switching (22). Recently, Calera et al. demonstrated that a null mutation of CaHK1 induced flocculation under certain conditions and affected the virulence, and they suggested that CaHK1 modulates the expression of cell surface components (5, 7).

In this study, we generated single and double disruptants of the C. albicans histidine kinase genes and showed that every histidine kinase is involved in hyphal formation and virulence. In addition, we hypothesize that CaSLN1 and CaNIK1 function upstream of CaHK1 but are located in distinct signal transmission pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Screening of the C. albicans HK1 gene.

The CaHK1 gene was cloned by screening a C. albicans genomic DNA library with the 1.5-kb XbaI-XbaI fragment of CaHK1 as a probe, which was amplified by PCR. Hybridization was carried out under low-stringency conditions in a buffer containing 0.25 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.2), 2× SSC (1× SSC contains 150 mM NaCl and 15 mM sodium citrate), 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 25% (vol/vol) formamide at 37°C. Radiolabelling of DNA with [α-32P]dCTP and DNA sequencing were carried out by a random priming method as previously described (20). Construction of the C. albicans genomic DNA library and cloning of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1 were reported previously (16, 24).

Disruption of CaNIK1 and CaHK1.

Disruption of the histidine kinase genes was performed according to the ura-blaster protocol (9). The entire open reading frames of CaSLN1, CaNIK1, and CaHK1 were cloned into pUC19. Then, the 0.6-kb SnaBI-BalI region of CaSLN1 (16), the 1.4-kb BalI-BalI region of CaNIK1, and the 3.5-kb HpaI-BstPI region of CaHK1 were excised and ligated with a 3.8-kb BamHI-XbaI fragment carrying the hisG-URA3-hisG module (9), generating pCASLN1U, pCANIK1U, and pCAHK1U. After the three constructs were linearized by digestion with an appropriate endonuclease, 10 μg of each was transformed into C. albicans CAI4 (ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434) cells by the lithium acetate method (21), and the integration of the hisG-URA3-hisG module into the targeting alleles was confirmed by PCR and Southern blotting. After the URA3 gene was excised by 5-fluoroortic acid (5-FOA), the heterozygous mutants were again transformed with the same disruption constructs and selected by ura auxotrophs. Double disruptants were created by further disrupting the CaNIK1 or CaHK1 alleles in the casln1Δ null mutants. All the mutants used for the experiments contained one copy of URA3 at a disrupted histidine kinase locus (Table 1). Unless otherwise specified, C. albicans cells were cultured in YPD (1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 2% [wt/vol] peptone, 2% [wt/vol] dextrose). Hyphal formation was induced by culturing the C. albicans cells on agar plates containing 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C for 3 days.

TABLE 1.

Histidine kinase mutants of C. albicans used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| CAI4 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 | 9 |

| CAF2-1 | ura3Δ::imm434/URA3 | 9 |

| S | casln1Δ::hisG/casln1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | 16 |

| N | canik1Δ::hisG/canik1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

| H | cahk1Δ::hisG/cahk1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

| SN | casln1Δ::hisG/casln1Δ::hisG CaNIK1/canik1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

| SH | casln1Δ::hisG/casln1Δ::hisG cahk1Δ::hisG/cahk1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

| NH | canik1Δ::hisG/canik1Δ::hisG cahk1Δ::hisG/cahk1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

Determination of virulence.

Four-week-old male CD-1 mice were purchased from Charles River Japan (Tokyo, Japan) and were intravenously injected with 107 cells of C. albicans strains as indicated below. The number of surviving mice was scored.

Expression of the recombinant CaSln1, CaNik1, and CaHk1 proteins.

The entire coding region of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene was cloned between the BamHI and HindIII sites (downstream of the polyhedrin promoter) of pFASTBAC1 with the BamHI and HindIII linkers to generate pFASTBAC1-GST. The DNA fragments encoding amino acids 417 to 1378 of CaSln1p, 421 to 1082 of CaNik1p, and 1930 to 2472 of CaHk1p were amplified by PCR and ligated at the HindIII site of pFASTBAC1-GST. Thus, CaSln1p(417–1378), CaNik1p(421–1082), and CaHk1p(1930–2472) were expressed in insect cells as fusions with GST. Insect cells (Sf-9) were infected with baculoviruses bearing CaSLN1, CaNIK1, or CaHK1 at a multiplicity of infection of 10 and further cultured for 72 h (15). The GST fusion proteins, designated GST-CaSln1p, GST-CaNik1p, and GST-CaHk1p, respectively, were extracted from the infected cells and purified by affinity column chromatography with glutathione-Sepharose as previously described (24). For Western blotting, approximately 0.1-μg quantities of the proteins were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, hybridized with anti-GST antibody (Pharmacia), and detected with the ECL-plus kit (Amersham).

Assays for autophosphorylation activities of the recombinant CaSln1, CaNik1, and CaHk1 proteins.

Autophosphorylation activities of the C. albicans histidine kinases were determined by incubating approximately 10 μg of the purified proteins that were bound to glutathione-conjugated agarose beads in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 20 μM [α-32P]ATP (specific activity, 100 Ci/mmol) at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the proteins were separated on SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography (19).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

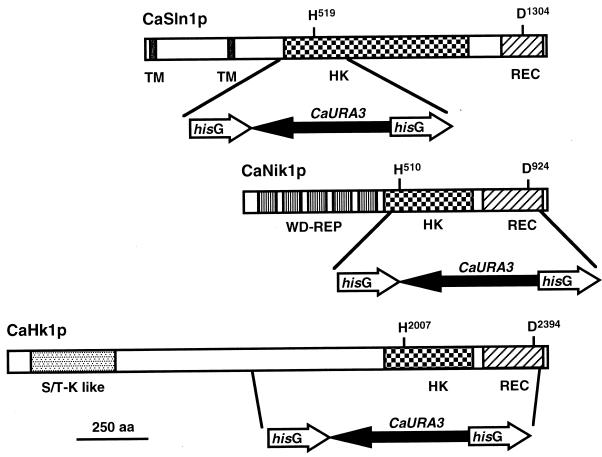

To gain more insight into the physiological roles of the C. albicans histidine kinases, we generated and characterized a series of mutant strains in which one or two histidine kinase genes were disrupted. Disruption constructs were designed to eliminate the autokinase domains of CaSln1p (16) and the autokinase and receiver domains of CaNik1p and CaHk1p (Fig. 1). All the mutants used for the experiments contained one copy of URA3 (Table 1) and exhibited similar doubling times (ranging from 1.5 to 2 h) when cultured in YPD medium.

FIG. 1.

Disruption of CaSLN1, CaNIK1, and CaHK1 in C. albicans. The strategy for disrupting each histidine kinase gene is illustrated with the expected structure of each product. The entire open reading frames of CaSLN1, CaNIK1, and CaHK1 were cloned into pUC19. Then, the 0.6-kb SnaBI-BalI region of CaSLN1 (16), the 1.4-kb BalI-BalI region of CaNIK1, and the 3.5-kb HpaI-BstPI region of CaHK1 were replaced by the hisG-URA3-hisG module (9). H519 and D1304 of CaSln1p, H510 and D924 of CaNik1P, and H2007 and D2394 of CaHk1p are the predicted phosphorylating histidines and aspartic acids, respectively, of their products. TM, transmembrane domain; HK, histidine kinase domain; REC, response receiver domain; WD-REP, repeats of an approximately 90-amino-acid motif; S/T-K like, serine/threonine kinase-like domain; aa, amino acids.

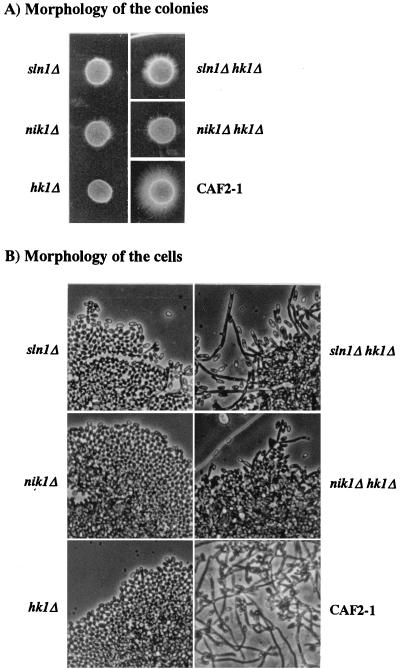

Because a null mutation of CaNIK1 was shown to cause a severe defect in hyphal formation in spider medium (3), these disruptants were first tested for the ability to develop hyphae. We used serum to induce hyphal growth because, among tested substances, serum was the most effective inducer of hyphal growth of CAF2-1 and its histidine kinase mutants. Consistent with the previous report by Alex et al. (3), hyphal formation was significantly deteriorated in the canik1Δ null mutants, even when hyphal development was induced by serum (Fig. 2). Disruption of CaSLN1 or CaHK1 also impaired hyphal formation compared with that of the wild type, CAF2-1 (Fig. 2). Effects of the disruption of a histidine kinase gene on hyphal formation were more prominent in cahk1Δ null mutants. The hypha-forming ability was nearly completely abolished in the cahk1Δ null mutants, whereas the casln1Δ and canik1Δ null mutants inefficiently generated hyphae on the periphery of the colonies when they were cultured in the presence of serum (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Effects of disruption of CaSLN1, CaNIK1, and CaHK1 on the hypha development of C. albicans. Ten million cells of the parental strain, CAF2-1, and the casln1Δ, canik1Δ, cahk1Δ, casln1Δ cahk1Δ, and canik1Δ cahk1Δ null mutant strains were seeded on agar plates containing 10% fetal bovine serum and were incubated at 37°C for 3 days.

CaSln1p is predicted to be a cell surface protein with an extracellular sensor domain, whereas both CaNik1p and CaHk1p are supposed to be cytosolic proteins (Fig. 1) (3, 6, 16, 22). Therefore, we asked if CaSln1p functions upstream of CaNik1p and CaHk1p. To address this possibility, we created mutants in which more than one histidine kinase gene was disrupted. Double disruption of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1 was impossible, suggesting that a simultaneous disruption of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1 is lethal. The disruption of CaSLN1 or CaNIK1 in the cahk1Δ null mutants partially restored hypha-forming ability in the presence of serum. Both casln1Δ cahk1Δ null mutants and canik1Δ cahk1Δ null mutants developed hyphae more efficiently than did cahk1Δ null mutants (Fig. 2). These results suggest that CaSLN1 and CaNIK1 are located upstream of CaHK1 but function in distinct signal transmission pathways. Furthermore, because both CaSLN1 and CaNIK1 are required for hyphal formation, there may be a negative regulator between CaHk1p and the other two histidine kinases.

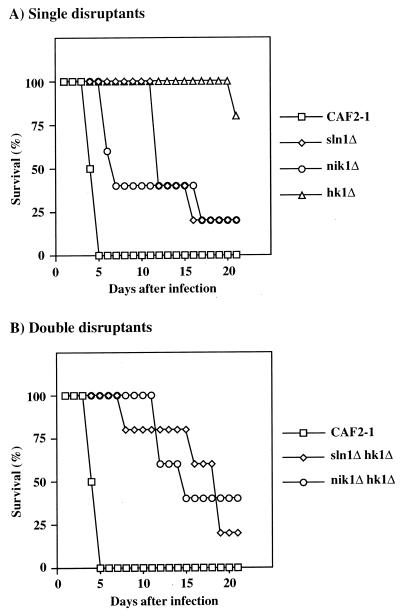

The hypha-forming ability of C. albicans has been thought to be related to virulence (17). This prompted us to examine the effects that a deletion of the histidine kinase genes would have on virulence in a mouse systemic candidiasis model. Immunocompetent CD-1 mice were intravenously injected with 107 cells of each mutant, and their survival was monitored. As shown in Fig. 3, all mice that were injected with wild-type CAF2-1 cells died within 5 days. The virulence of the cahk1Δ null mutants was markedly reduced, whereas that of the casln1Δ null mutants and canik1Δ null mutants was only slightly attenuated compared with that of CAF2-1 (Fig. 3). In addition, the deletion of CaSLN1 or CaNIK1 in the cahk1Δ null mutants partially restored the virulence. The restoration of the virulence by the deletion of CaSLN1 or CaNIK1 in the cahk1Δ background also coincided with the reappearance of hypha-forming ability in the presence of serum. These results also support our hypothesis that CaSln1p and CaNik1p are located upstream of CaHk1p, regulating negative effectors of CaHk1p. Although Lay et al. reported the positional effects of URA3 on orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase activity (12) and virulence, we did not see a clear correlation between the orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase activities of the histidine kinase mutants and their virulence.

FIG. 3.

Effects of the disruption of CaSLN1, CaNIK1, and CaHK1 on the virulence of C. albicans. Male CD-1 mice were infected with 107 cells of the parental strain, CAF2-1, and the casln1Δ, canik1Δ, cahk1Δ, casln1Δ cahk1Δ, and canik1Δ cahk1Δ null mutant strains. In each experiment, 10 mice were used for each strain.

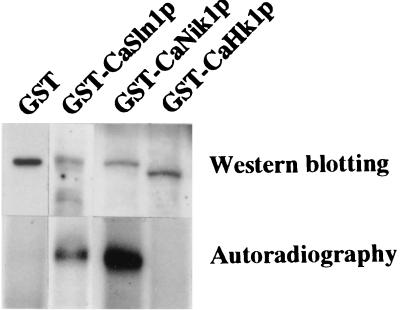

CaSln1p, CaNik1p, and CaHk1p all possess histidine kinase domains, but their enzyme activities remain to be established. To confirm the kinase activities of these proteins, we expressed the truncated forms of CaSln1p, CaNik1p, and CaHk1p, which contain their own putative autokinase and response receiver domains. The recombinant proteins were expressed as GST fusion proteins in insect cells and purified by affinity chromatography with glutathione–Sepharose CL-4B (Fig. 4). Upon incubation with [α-32P]ATP, both GST-CaSln1p and GST-CaNik1p were strongly labelled with 32P, whereas no radioactivity was detected on GST or GST-CaHk1p (Fig. 4). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that GST-CaHk1p was not expressed in a correct conformation to sustain the activity, the above result suggests that at least CaSln1p and CaNik1p utilize their autokinase activities to initiate the phosphorelay in vivo.

FIG. 4.

Autophosphorylation of CaSln1p, CaNik1p, and CaHk1p. GST-CaSln1p, GST-CaNik1p, and GST-CaHk1p, which encompass the amino acid positions between 417 and 1378 of CaSln1p, 421 and 1082 of CaNik1p, and 1930 and 2472 of CaHk1p, respectively, were expressed in insect cells as fusion proteins with GST. Insect cells (Sf-9) were infected with recombinant baculoviruses bearing each histidine kinase gene at a multiplicity of infection of 10 and were further cultured for 72 h (15). Approximately 0.1 μg of each indicated purified protein was separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, hybridized with the anti-GST antibody (Pharmacia), and detected by Western blotting with an ECL-plus kit (Amersham). Autophosphorylation of the indicated proteins was determined by incubating approximately 10 μg of each of the purified proteins complexed with glutathione-agarose beads with [α-32P]ATP. The radiolabelled proteins were separated on SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography.

Several histidine kinase genes in eukaryotes were identified, and they are presumably involved in signal transmission, e.g., sensing and adapting to changes of osmolarity in S. cerevisiae (14) and N. crassa (2) and ethylene sensing in plants (8, 10, 23). In this study, we have shown that the histidine kinases are involved in serum-induced hyphal development and virulence in C. albicans, but the real inducer for signal transmission remains to be identified. As mentioned above, Hog1p and Skn7p sense the signal from Sln1p and control the expression of the downstream genes (13, 14). In addition, it has been demonstrated that the activation of Hog1p is associated with the tyrosine phosphorylation of the protein (4, 14). We also created an anti-Hog1p antibody to see whether the tyrosine phosphorylation on Hog1p is induced during hyphal induction and whether it is altered in the mutants with disruptions of the histidine kinase genes. Detection of the tyrosine phosphorylation of Hog1p upon hyphal induction and increased osmolarity, however, was unsuccessful, presumably due to strong phosphatase activities within the C. albicans cells. In addition, the hypha-forming ability and virulence of the hog1Δ null mutants were not affected by the further disruption of any histidine kinase gene in the hog1Δ null mutants. Furthermore, whereas the hog1Δ null mutants displayed increased susceptibilities to a wide variety of stresses, such as hyperosmolarity (11), higher temperature, anisomycin, and arsenite, none of the histidine kinase mutants showed retarded growth under these conditions compared with the growth of the wild type, CAF2-1. Thus, it seems that CaSLN1, CaNIK1, and CaHK1 are all independent of HOG1 in C. albicans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. B. Miwa for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan, to T.Y.-O.

T.Y.-O. and T.M. contributed equally to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertyn J, Hohmann S, Thevelein J M, Prior B A. GPD1, which encodes glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, is essential for growth under osmotic stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and its expression is regulated by the high-osmolarity glycerol response pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4135–4144. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alex L A, Borkovich K A, Simon M I. Hyphal development in Neurospora crassa: involvement of a two-component histidine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3416–3421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alex L A, Korch C, Selitrennikoff C P, Simon M I. COS1, a two component histidine kinase that is involved in hyphal development in the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7069–7073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewster J L, de Valoir T, Dwyer D, Winter E, Gustin M C. An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science. 1993;259:1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.7681220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calera J A, Calderone R. Flocculation of hyphae is associated with a deletion in the putative CaHK1 two-component histidine kinase gene from Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1999;145:1431–1442. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calera J A, Choi G H, Calderone R A. Identification of a putative histidine kinase two-component phosphorelay gene (CaHK1) in Candida albicans. Yeast. 1998;14:665–674. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199805)14:7<665::AID-YEA246>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calera J A, Zhao X-J, De Bernardis F, Sheridan M, Calderone R. Avirulence of Candida albicans CaHK1 mutants in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4280–4284. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4280-4284.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang C, Kwok S F, Bleecker A B, Meyerowitz E M. Arabidopsis ethylene-response gene ETR1: similarity of product to two component regulators. Science. 1993;262:539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.8211181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonzi W A, Irwin M Y. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hua J, Chang C, Sun Q, Meyerowitz E M. Ethylene insensitivity conferred by Arabidopsis ERS gene. Science. 1995;269:1712. doi: 10.1126/science.7569898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jose C S, Monge R A, Perez-Diaz R, Pla J, Nombela C. The mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog HOG1 gene controls glycerol accumulation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5850–5852. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5850-5852.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lay J, Henry L K, Clifford J, Koltin Y, Bulawa C E, Becker J M. Altered expression of selectable marker URA3 in gene-disrupted Candida albicans strains complicates interpretation of virulence studies. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5301–5306. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5301-5306.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S, Ault A, Malone C L, Raitt D, Dean S, Johnston L H, Deschenes R J, Fassler J S. The yeast histidine protein kinase, Sln1p, mediates phosphotransfer to two response regulators, Ssk1p and Skn7p. EMBO J. 1998;17:6952–6962. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda T, Wurgler-Murphy S M, Saito H. A two component system that regulates an osmosensing MAP kinase cascade in yeast. Nature. 1994;369:242–245. doi: 10.1038/369242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy C I, Piwnica-Worms H, Grunwald S, Romanow W G. Expression of proteins in insect cells using baculovirus vectors. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1997. pp. 16.9.1–16.11.12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagahashi S, Mio T, Ono N, Yamada-Okabe T, Arisawa M, Bussey H, Yamada-Okabe H. Isolation of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1, the genes for osmosensing histidine kinase homologues, from the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1998;144:425–432. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odds F C. Candida infections: an overview. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1987;15:1–5. doi: 10.3109/10408418709104444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ota I M, Varshavsky A. A yeast protein similar to bacterial two component regulators. Science. 1993;262:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.8211183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Posas F, Wurgler-Murphy S M, Maeda T, Witten E, Thai T C, Saito H. Yeast HOG1 MAP kinase cascade is regulated by a multiple phosphorylating mechanism in the SLN1-TPD1-SSK1 “two-component” osmosensor. Cell. 1996;86:865–875. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanglard M, Ischer F, Monod M, Bille J. Cloning of Candida albicans genes conferring resistance to azole antifungal agents: characterization of CDR2, a new multidrug ABC transporter gene. Microbiology. 1997;143:405–416. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srikantha T, Tsai L, Daniels K, Enger L, Highley K, Soll D R. The two-component hybrid kinase regulator CaNIK1 of Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1998;144:2715–2729. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-10-2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson J Q, Lanahan M B, Yen H-C, Giovannoni J J, Klee H J. An ethylene-inducible component of signal transduction encoded by Never-ripe. Science. 1995;270:1807–1809. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada-Okabe T, Shimmi O, Doi R, Mizumoto K, Arisawa M, Yamada-Okabe H. Isolation of the mRNA-capping enzyme and ferric reductase related genes from Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1996;142:2515–2523. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-9-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]