Abstract

This present paper is an investigation of a framework for Safety-Critical Maritime Infrastructure (SCMI) evaluation. The framework contains three Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) tools, namely: fuzzy Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA), Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) and Weighted Aggregates Sum Product Assessment (WASPAS). It also contains five safety practice criteria: people's safety, property safety and monitoring capabilities, response to regular and irregular threats in a robust yet flexible manner, and breaches in physical security. The framework has four safety culture criteria: learning from experience and inter-element collaboration, lack of facility maintenance, and anticipating risk events and opportunities. Through the framework, an evaluation of the safety practices and safety culture of six Nigerian seaports is done. Then, data obtained from the ports in regard to their safety practices and culture were analysed in line with the framework identified and adopted. The results revealed that the safety of people's life is the most important safety practice and contributed about 47.90% to evaluate the SCMI. Results equally showed that the most significant safety culture is learning from experience, and accounted for approximately 53.20% in assessing the SCMI. Similarly, the TOPSIS method ranked Warri (A5) and Tin Can Island A1 as the best and worst safety practices performance, respectively. Results of analyses on the TOPSIS showed that Apapa port (A2) and Onne port (A6) had the best and worst performances correspondingly. WASPAS was also analysed. The results indicated that A6 performed the best safety practice performance, while A2 had the worst safety practice performance. Analysis of the WASPAS method was equally done. It showed that A1 had the worst safety culture performance, while A5 had the best safety culture performance. Therefore, the proposed framework could serve as a veritable tool for analysing SCMI by using safety practice and safety culture criteria.

Keywords: Decision support framework, Maritime industry, Multi-criteria, Safety-critical infrastructure, Safety practice and culture

1. Introduction

The maritime industry is a multi-billion-dollar business that affects the economies of nations participating in international trade [1]. This trade depends on the volume of activities in seaports - the main channels for import and export activities. Hence, stakeholders, government, port authorities, and public and private investors are keen to ensure the safety of lives and properties to make seaports attractive to clients and investors. This has stimulated interest in investment in Safety-Critical Maritime Infrastructure (SCMI) in order to reduce compensation costs associated with accidents and security breaches [2]. In most seaports worldwide, SCMI management is under the supervision of port authorities. They are responsible for the safety of lives and properties within a port’s environment because of the huge investment in SCMI.

The safety of lives and properties is critical to port management because it affects operations and profit of a port. For instance, port authorities must provide adequate logistics against maritime terrorism [3] because of the need to improve lives and property safety. Also, port authorities must provide the necessary logistics to safeguard ports' investments [4] because of the need to improve investment sustainability. In addition, they are necessary to prevent the dumping of refuse and non-degradable wastes into seaports because of the need to enhance environmental sustainability. These responsibilities make port safety management an essential activity among maritime industry stakeholders [5]. Hence, stakeholders are required to conduct periodic evaluations of SCMI.

SCMI evaluation is crucial to seaports' security and economy and affects their effectiveness and productivity [6]. This evaluation aids the analysis of SCMI performance. It gives port authorities a thorough understanding of the port's safety. It also allows a port authority to evaluate its performance by comparing it with the industry’s standards. This evaluation serves as an essential tool for setting up benchmarks. Studies have shown that this benchmarking is complex because different safety and security ratings are required for port facilities [7]. This has limited the implementation of external benchmarking in the maritime industry, especially in developing countries.

External benchmarking can be seen from two perspectives: safety practice and safety culture. Safety practice evaluates safety issues that concern human lives, property and monitoring capabilities. It also considers a system's potential to respond to regular and irregular threats and breaches in physical and information security. On the other hand, the latter Safety culture, on its part, covers issues that relate to learning from experience, lack of facility maintenance, anticipating risk events and opportunities and inter-element collaboration. To conduct external benchmarking using these perspectives, stakeholders require a Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) approach.

Studies have utilised MCDM approaches to address safety issues in the maritime industry. However, no investigation has been conducted into benchmarking ports' SCMI using MCDM. Therefore, the paper presents a framework for SCMI evaluation using selected safety practices and safety culture criteria. The framework contains three MCDM approaches, namely: fuzzy Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA), Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) and Weighted Aggregates Sum Product Assessment (WASPAS). The fuzzy SWARA method was used to determine the importance of safety practice and safety culture criteria. Similarly, the TOPSIS and WASAPAS methods were applied to rank the performance of ports' safety practices and culture criteria.

There are other sections in the paper. There is a review of relevant literature on risk management using Multi-Criteria. The next is a presentation of detail on the approach used to fill the identified research gap. This is followed by an analysis of data in which presentation of results and discussion is done. The last section sums up what has been done.

2. Literature review

Several studies have documented the importance of MCDM techniques in addressing issues in the maritime industry [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]]. Risk management in seaports is one field where MCDM techniques have been used to generate information to improve decision-making. For instance, Ref. [8] reported the necessity of studying risk management from a multi-criteria point of view. They classified risks in dry seaports to produce accurate information on dangers in seaports. They also identified the three significant dangers in a seaport under several risk categories. Discussion how the maritime industry could analyse safety issues using a Multi-criteria approach is another subject in the maritime literature [9]. Scholars equally considered the influence of technological, environmental, and social parameters on failure modes during risk analysis at seaports. They have used MCDM techniques to aid their investigations to manage the relationship between these parameters. For example, Ref. [9] used TOPSIS-based methodology to provided insights into the essential failure modes regarding loading and unloading port operations. In another study, Ref. [10] used a TOPSIS framework to investigate the congestion risks based on a cost-benefit ratio. They provided vital information on managing inland waterway congestions safely under dynamic risk situations. For instance, they justified risk control options desirability and undesirability.

Researchers relied on a fuzzy-based MCDM framework due to the imprecision of risk information during the seaport risk study. For instance, Ref. [11] proposed a transportation risk map using a fuzzy-based methodology containing five linguistic variables: very high, high, medium, low, and very low. Their study used fuzzy triangular numbers to evaluate hazards, including operational, security, technical, natural, and organisational concerns. Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP) was also used to hazard, vulnerability and exposure, and mitigation capacity. The outcome of their study showed that a risk map could be used to improve navigational safety. Ref. [12] used a fuzzy VIKOR method to evaluate risks in container ports. The significance of the risk management criteria was evaluated using a FAHP. A z-number total utility idea was deployed to deal with uncertainty in experts’ judgment. Similarly, they justified the applicability of using linguistic-based values to enhance safety assessment. In another study, Ref. [13] reported an evidential reasoning approach for risk assessment in ports. They used fuzzy sets to deal with risk assessment data that are ambiguous and imprecise. To increase the approach's applicability, they classify operational risks into multiple classes: human, environmental, and technical hazards [13]. Further, they demonstrated the suitability of using fuzzy belief rules and Bayesian networks to evaluate risks' impact on marine supply chains. Compared to conventional risk analysis techniques, their approach improved the uncertainty evaluation in risk data. They went on to note the importance of using subjective information to support decision-making, especially when prioritising maritime risk factors.

Stakeholders in the maritime sector are also interested in the sustainability of seaports. One of the reasons stakeholders are looking for methods to sustain seaport activities is environmental protection. Other reasons include economic development, social responsibility, and resilience. For instance, Ref. [14] presented a study that used sustainability indicators to classify seaport actors: private, state and others. They observed that the relationship among seaports’ sustainability indicators is actor-dependent. Also, they noted that the major forces behind ports' efficiency and competitiveness are state actors. Ref. [15] examined the significant seaport practices that contribute to sustainable seaport development in the context of the major Indian seaports through stakeholder cooperation and internal sustainable management decision framework. They used theoretical paradigm to develop a conceptual model for seaport sustainability analysis. The model was used to process information obtained from 23 seaport authority. They observed that Indian seaport managers perceive the economic component as being the most significant, while the social dimension is seen as being of less importance. Scholarly reports have showned that there is a need to include green practices in port operations, especially in dry ports. For example, Ref. [16] analysed studies on sustainable development and environmental problems that are related to ports and sea trade. They observed that there was no coordination between the various studies and systemic discussions on the environmental aspects of dry ports.

Scholars working in the area of container management have also resported the usefulness of MCDM tools for port management. For example, Ref. [17] presented a study on choosing the best container seaport in the Black Sea area. The selection procedure used entropy, OCRA, and EATWIOS techniques. Based on a spearman correlation report, they noticed that the findings from the OCRA and EATWIOS methods were comparable. Their key result is that growing outputs rationally can improve a container seaport's performance rather than attempting to reduce source utilisation by concentrating on input factors. Ref. [18] proposed a combined fuzzy LBWA (Level Based Weight Assessment) and fuzzy CoCoSo'B (CoCoSo with Bonferroni) method to deal with container port selection in the maritime industry. The method was used to evaluate selected container ports in Europe. They observed that port expenses influenced the evaluation process the most. The best and worst ports among those considered were the ports of Antwerp and Barcelona, respectively. They concluded that the highly complex decision-making issues encountered in the maritime industry could be resolved using the fuzzy-based method.

Studies have support the use of MCDM approach for maritime operations. This is due to the fact that the approach can deal with the intricacy and uncertainty that are common in this sector. Furthermore, it promotes accountability and transparency, enabling stakeholders to participate in the marine industry's decision-making process. For example, Ref. [19] used information from stakeholders to analyse operational measures for the maritime business: hinterland traffic diversion, congestion pricing, off-dock container yards, fast rail shuttles, and expanded rail connections. They used framework that considers nine factors and fuzzy VIKOR (VIsekriterijumska optimizacija I KOmpromisno Resenje) and fuzzy Shannon entropy for the analysis. The fuzzy VIKOR method identified hinterland traffic diversion and fast rail shuttles as the most and least suitable operational measures for Tin Can port, Nigeria. Ref. [20] presented a Multi-criteria methodology for risk assessment in seaports. Their methodology was used to evaluate mishaps that might happen in a seaport. They used a goal programming approach to determine the ship's accident rate.

From the article reviewed, MCDM methods are useful in the maritime industry. However, there needs to be a report on applying SWARA as a tool for dealing with safety practices and culture in the maritime industry. This study observed that TOPSIS has yet to be used to evaluate safety practice and culture in the maritime industry. WASPAS application in the maritime industry has yet to cover the issue of safety practice and culture. These knowledge gaps are the motivation for the current study.

3. Methodology

A fuzzy-based MCDM method has been used in the paper to establish a framework for SCMI evaluation. The method has been selected because of the ambiguity in seaports’ safety data. Fig. 1 presents the proposed framework. It has been designed using fuzzy SWARA, fuzzy WASPAS, and TOPSIS methods. The reason for selecting these MCDM methods are presented in appropriate sections.

Fig. 1.

Proposed framework for SCMI evaluation.

3.1. Fuzzy SWARA

Fuzzy SWARA has been identified as a useful tool for decision-making at the highest levels of business and enterprises [21]. It is used to handle the uncertainty about criteria importance. Its main advantage is that the weight of the criteria can be determined appropriately in accordance with each expert's criteria individually or jointly defined [20]. Other benefits of SWARA are highlighted in Ref. [22]. The following are the steps required to implement SWARA:

-

Step1

Determination of important criteria using linguistic terms

In this step, decision-makers are required to select the most crucial criterion. Once the most crucial criterion has been identified, it is eliminated from a decision matrix. This iterative process is continued until one criterion is left in the decision matrix.

-

Step 2

Determination of criteria relative importance

In this step, experts determine the relative importance of the criteria relative to the most significant criterion in a decision matrix. This process is iterative.

-

Step 3

Determination of criteria coefficients

In this step, Equation (1) is used to determine co-efficient for criteria in a decision matrix.

| (1) |

where denotes criterion j's co-efficient and denotes criterion j's relative importance.

-

Step 4

Estimation of criteria initial weights

This step uses Equation (2) to determine a criterion's starting weights. The most crucial criterion in this process is the initial weight, which is taken as one.

| (2) |

where qj denotes the initial weights for criterion j.

-

Step 5

Determination of criteria normalised weights

This step uses initial weights for criterion to generate their normalised weight (Equation (3)).

| (3) |

where wj denotes the criterion's j importance.

3.2. Fuzzy TOPSIS

TOPSIS is among the leading MCDM methods for decision-making processes in engineering and science. It has been accepted because it has a very straightforward mathematical form. Its procedure has a clear and intelligible logic. In comparison to other methods, its computation procedure is fairly straightforward [23]. TOPSIS supports the analysis of linguistic variables for criteria evaluation. Hence, scholarly works have reported different TOPSIS variants [24]. The application of TOPSIS variants is based on the data type for a decision-making problem.

During the application of TOPSIS, data are pre-processed to reduce the overbearing effects of criteria with large values on a decision-making process: data normalisation. Studies have shown that this pre-processing requires classifying criteria as benefit-oriented or cost-oriented. In some cases, data conversion is among the pre-processing phase of a TOPSIS variant, especially when dealing with linguistic values to facilitate data normalisation. This processing might require converting linguistic values to fuzzy-based values.

Once data are normalised, they generate a weighted normalised decision matrix (Equation (4)). This operation entails using MCDM methods to determine the criteria's importance. This matrix is used to determine the ideal and non-ideal solutions for the criteria in a decision matrix.

| (4) |

For a triangular fuzzy number, the weighted normalised values are used to generate three pieces of information about the ideal solutions for the criteria. The first is to provide information about the criteria for ideal optimistic solutions (Equation (5)). The second is to provide information about the criteria ideal most likely solutions (Equation (6)). And the third is to give information about the criteria for ideal pessimistic solutions (Equation (7)).

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

where denotes an ideal value for criterion j regarding an optimistic value, an ideal value for criterion j regarding a most likely value, and an ideal value for criterion j regarding a pessimistic value.

Also, the weighted normalised values are used to provide three major pieces of information about the non-ideal solutions for the criteria. The first has to do with providing information about the criteria non-ideal optimistic solutions (Equation (8)). The second concerns providing information about the criteria non-ideal most likely solutions (Equation (9)). And the third provides information about criteria non-ideal pessimistic solutions (Equation (10)).

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

where denotes a non-ideal value for criterion j regarding an optimistic value, a non-ideal value for criterion j regarding a most likely value, and a non-ideal value for criterion j regarding a pessimistic value.

Once these solutions have been determined, the alternatives’ distance from the ideal and non-ideal solutions could be determined. Equation (11) represents the mathematical expression for an alternative’s distance from ideal solutions, while Equation (12) represents the mathematical expression for an alternative’s distance from non-ideal solutions

| (11) |

| (12) |

where denotes the ideal solution for alternative i, and denotes the non-ideal solution for alternative i.

These distances are used to generate the alternatives’ closeness coefficient (Equation (13)). The co-efficient is used to make a decision based on a higher-the-better concept.

| (13) |

where Ci denotes the closeness coefficients for alternative i.

3.3. WASPAS method

This uses two MCDM methods to proffer a solution to a decision-making problem. The first method, which is a Weighted Additive Method (WAM), uses the concept of higher-the-better principle to support a decision-making process. Weighted Product Method (WPM), which is the second method, uses a lower-the-better principle supports a decision-making process. WASPAS method aggregates the results from these methods to proffer solutions to a MCDM problems. An aggregating co-efficient is used to facilitate the aggregation process. This co-efficient also provides a means of generating sensitivity analysis results for MCDM problems.

The application of the WASAPS method for linguistic information processing involves converting linguistic information into fuzzy numbers. This conversion is achieved by partitioning linguistic responses into membership functions (Fig. 2). Once fuzzy values are generated, experts' judgments aggregation can be implemented [25]. Equations (14), (15), (16) present the aggregation expressions for fuzzy triangular numbers (TFN) [26].where e denotes an expert, the alternative i value for criterion j regarding an optimistic value, denotes the alternative i value for criterion j regarding a most likely value, and the alternative i value for criterion j regarding a pessimistic value.

Fig. 2.

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

The fuzzy numbers need to be normalised, before they are defuzzified (Equations (17), (18), (19)). Equation (17) gives the expression for normalising the first number (optimistic value) in a TFN set, while the middle value (most likely value) in a TFN set is normalised using Equation (18). Lastly, Equation (19) is used to normalise the last value (pessimistic value) in a TFN set [27].

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

where denotes alternative i normalised value for criterion j regarding an optimistic value, denotes alternative i normalised value for criterion j regarding a most likely value and denotes alternative i normalised value for criterion j regarding a pessimistic value.

After the normalisation process, Equation (20) is used to generate a single index for the alternation regarding the criteria. This process is known as defuzzification.

| (20) |

where denotes the actual values for alternative i for criterion j.

The defuzzified values are used to generate WAM and WAP values for the alternatives. Equation (21) gives the mathematical expression for alternative i weighted sum value, while this alternative’s weighted sum value is expressed as Equation (22).

| (21) |

| (22) |

where denotes the weighted sum value for alternative i, and denotes the weighted product value for alternative i.

The results from Equations (21), (22) are used to generate an alternative’s WASPAS value (Equation (23)). Technically, the aggregating co-efficient could be expressed as Equation (24) [28].

| (23) |

| (24) |

where denotes the WASPAS value for alternative i,

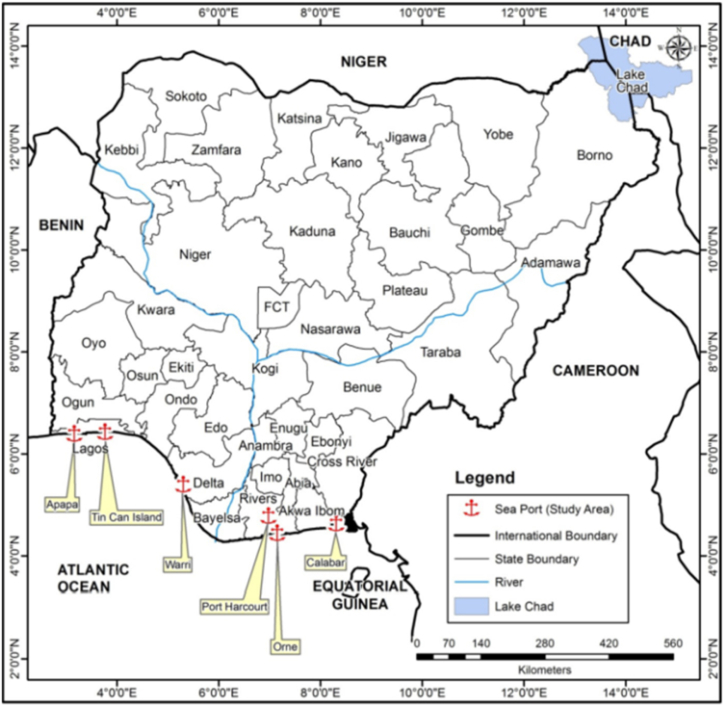

3.4. Case study

Seaports in Nigeria are used in the paper to evaluate the proposed framework's applicability (Fig. 3). In Nigeria, seaports cluster along the coastal lines in the Southern parts of the country. In 2006, the Federal Government of Nigeria concessioned six seaports in Nigeria, because of poor performance [29]. The concessioned ports are: Tin can island Port: A1; Apapa port: A2; Calabar port: A3; Port Harcourt: A4; Warri port: A5; and Onne port: A6 – Table 1 contains information about these ports. These ports experienced an increase in productivity [29] after their concession in 2006 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Major seaports in Nigeria [29].

Table 1.

Selected seaports.

| Port | Description |

|---|---|

| A1 | Tin Can Island Port, which has a bearing of Latitude 62°N Longitude 30* 23°E, is situated Northwest of Lagos Port Complex. It can accommodate 10 to 16 vessels at once. Its pre-concession period began in 1975 when the nation's economic activity increased due to the oil boom and post-civil war rehabilitation. Due to the considerable volume of imports and exports that followed, the port experienced severe congestion. It was vital for the government to take action to decongest the port as a result of the knock-on effect, which was why a new port was built on Tin Can Island. Its development began in 1976 and was completed in 1977. |

| A2 | Nigeria's oldest and biggest port is the Lagos Port Complex, popularly known as Premiere Port (Apapa Quays). It is located in Apapa, the commercial hub of Nigeria's Lagos State. The port was founded in 1913, and the first four deep-water berths were built in 1921. The Apapa Port is cost-effective and user-friendly thanks to its modern cargo handling equipment and human support facilities. It benefits from rail, water, and multimodal road connections. It boasts an 8-m-long four-wheel gate for huge cargoes, giving the port an advantage over other ports in handling oversized commodities. |

| A3 | In the South-Southern area of Nigeria, in Calabar, Cross River State, estuaries, is where this Calabar Port is located. The Federal Government assumed control of the port in December 1969, replacing the prior private managers, most of whom were shipping firms. The Nigerian Port Authority was given control of the port by the government (NPA). The Third National Development Plan of 1975–1980 set out to improve, modernise, and expand the port of Calabar. This was done to modernise the port infrastructure to meet the nation of Nigeria's rising needs. On June 9, 1979, the new Calabar Port complex was commissioned. It is located 84 km (45 nautical miles) upstream of Fairway Buoy. |

| A4 | The port, also known as Rivers Port Complex, is located in the Gulf of Guinea. It had a modest beginning, growing from one berth for coal export to four berths to handle a cargo mix of import/export goods. The port's 1,259-foot-long dock can accommodate eight contemporary seagoing boats loading and unloading simultaneously. The port also has 16 bulk oil installations with a 3,048-ton capacity. There are four (4) Arcon sheds with a storage capacity of 12,486.15 square meters, seven stacking areas measuring 27,407.15 square meters, a conveyor belt, and a pier holding the structure. |

| A5 | Delta Ports is exceptional and has a vast potential longing for growth. The port is considered to be the port of the future because of the enormous potential that it offers. It offers benefits that set it apart and put it in a class of its own. These selling features include shorter freight hauling distances compared to other operating ports. As the port has long relied on captive cargoes to keep it afloat, it is capable of producing its cargo. Its short vessel turnaround time is an excellent advancement over previous years. The concessionaires guarantee cargo security and provide sufficient, cutting-edge facilities to handle all goods. |

| A6 | The first port of its sort in Nigeria to use the Landlord Port Model, designed to promote private sector involvement in the port industry, is located on the Bonny River Estuary beside Ogu Creek. One of the world's largest oil and gas-free zones, the port supports Nigerian activities in exploration and production. The Free Zone offers an onshore and offshore logistical centre for the Nigerian oil and gas industry. The entire West African and Sub-Saharan oil fields are accessible through it. Over 65% of the port's export cargo passing through the Nigerian Sea Port is accounted for. In addition to Oil and Gas operations, the port also conducts several other businesses. |

Fig. 4.

Metric tonnage throughputs for cargo in Nigerian ports (before and after concession) [30].

The framework's applicability evaluation is based on information during seaports’ post-concession. Four experts in the Nigerian maritime industry were contacted. The experts provide information on safety practices and safety culture criteria. Table 2 presents information about the safety practice and safety culture criteria. The experts have a minimum of ten years of experience and professional maritime safety certifications, such as Standards of Training Certification and Watch-keeping. The experts were selected because of their knowledge of International Safety Management Code. The experts have also been selected because they have a deep understanding of maritime risk management. Table 3 presents information on the educational qualification of experts.

Table 2.

Safety practice and safety culture criteria.

| Safety practice | Safety culture |

|---|---|

| C11: People's safety [31,32] | C21: Learning from experience [33,34] |

| C12: Property's safety [32] | C22: Lack of facility maintenance [33,34] |

| C13: Monitoring capabilities [34] | C23: Anticipate risk events and opportunities [33,34] |

| C14: Respond to regular and irregular threats in a robust yet flexible manner [33] | C24: Inter-element collaboration [33,34] |

| C15: Breaches in physical security [32] |

Table 3.

Experts’ bio-data.

| Expert | Qualifications |

|---|---|

| E1 | Mechanical engineering (B.Eng) and Transport management (M.Sc) |

| E2 | Business administration (B.Sc) and MBA |

| E3 | Operations research (B.Sc) and Transport management (M.Sc) |

| E4 | Electrical and electronics engineering (B.Eng) and Transport management (M.Sc) |

A questionnaire was used to collect information from the experts (Appendix 1). In the questionnaire, a section was created for the criteria importance using the information in Table 4 [35]. The information in Table 5 was used to rate the ports in terms of the criteria in Table 2 [36].

Table 4.

Linguistic terms for the criteria evaluation.

| Linguistic variable | FTN |

|---|---|

| Equally important | (1, 1, 1) |

| Moderately less important | (2/3, 1, 3/2) |

| Less important | (2/5, 1/2, 2/3) |

| Very less important | (2/7, 1/3, 2/5) |

| Much less important | (2/9, 1/4, 2/7) |

Table 5.

Linguistic terms for the seaports rating.

| Linguistic variable | FTN |

|---|---|

| Very Low (VL) | (0, 0, 0.25) |

| Low (L) | (0, 0.25, 0.5) |

| Medium (M) | (0.25, 0.5, 0.75) |

| High (H) | (0.5, 0.75, 1.0) |

| Very High (VH) | (0.75, 1.0, 1.0) |

4. Results and discussion

Information regarding the significance of the selected criteria is presented in this section. This section also contains results of TOPSIS and WASPAS methods. Finally, it discusses the managerial implications of the generated results.

4.1. SWARA results

The SWARA method was implemented using the information presented in Table 6. The implementation began with the conversion of linguistic values to TFN. Using Equations (1), (2), (3), the information in Table 7 was generated. First, Equation (1) was used to generate the criteria coefficients. Second, Equation (2) was used to generate the criteria's initial weights. Equation (3) was equally used to generate the criteria’s final weights.

Table 6.

Linguistic and triangular rating of the criteria.

| DM1 | DM2 | DM3 | DM4 | DM1 | DM2 | DM3 | DM4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12 | MI | MI | MI | LI | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (2/5, 1/2, 2/3) |

| C13 | EI | LI | U | EI | (1, 1, 1) | (2/5, 1/2, 2/3) | (2/7, 1/3, 2/5) | (1, 1, 1) |

| C14 | MI | MI | MI | LI | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (2/5, 1/2, 2/3) |

| C15 | EI | LI | EI | LI | (1, 1, 1) | (2/5, 1/2, 2/3) | (1, 1, 1) | (2/5, 1/2, 2/3) |

| C22 | MI | EI | MI | MI | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (1, 1, 1) | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (2/3, 1, 3/2) |

| C23 | MI | EI | EI | EI | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1, 1) |

| C24 | MI | VLI | EI | MI | (2/3, 1, 3/2) | (2/7, 1/3, 2/5) | (1, 1, 1) | (2/3, 1, 3/2) |

Table 7.

Safety practice criteria importance.

| Criterion | Sj | Kj | qj | wj | Crisp value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.424 | 0.477 | 0.541 | 0.479 | |||

| C12 | 0.600 | 0.880 | 1.290 | 1.600 | 1.880 | 2.290 | 0.625 | 0.532 | 0.437 | 0.265 | 0.254 | 0.236 | 0.253 |

| C13 | 0.670 | 0.710 | 0.770 | 1.670 | 1.710 | 1.770 | 0.374 | 0.311 | 0.247 | 0.159 | 0.148 | 0.134 | 0.148 |

| C14 | 0.600 | 0.880 | 1.290 | 1.600 | 1.880 | 2.290 | 0.234 | 0.165 | 0.108 | 0.099 | 0.079 | 0.058 | 0.079 |

| C15 | 0.850 | 0.880 | 0.920 | 1.850 | 1.880 | 1.920 | 0.126 | 0.088 | 0.056 | 0.054 | 0.042 | 0.030 | 0.042 |

From Table 7, the most crucial safety practice criterion, people's life (C11), contributed roughly 47.90% to evaluating the seaports' SCMI. From a safety practice perspective, the least significant criterion, i.e., breaches in physical security (C15), contributes 4.20% to evaluating the SCMI. The summary of these results showed that the first three criteria contributed about 88% to the analysis of safety practices for the case study.

Table 8 presents results for the safety culture importance. The most crucial criterion for safety culture, learning from experience (C21), contributed roughly 53.20% to assessing the SCMI from a safety culture perspective. The contribution of inter-element collaboration (C24), the least significant criterion from the perspective of safety culture, to evaluating the SCMI is 7.20%. The results showed that the first two criteria contributed about 79.6% to the analysis of safety culture for the case study.

Table 8.

Safety culture criteria importance.

| Criterion | Sj | Kj | qj | wj | Crisp value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C21 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.479 | 0.530 | 0.593 | 0.532 | |||

| C22 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.38 | 1.750 | 2.000 | 2.380 | 0.571 | 0.500 | 0.420 | 0.274 | 0.265 | 0.249 | 0.264 |

| C23 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.38 | 1.750 | 2.000 | 2.380 | 0.327 | 0.250 | 0.177 | 0.157 | 0.133 | 0.105 | 0.132 |

| C24 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 1.740 | 1.830 | 1.980 | 0.188 | 0.137 | 0.089 | 0.090 | 0.072 | 0.053 | 0.072 |

4.2. Fuzzy TOPSIS results

Table 9 presents the aggregated ports’ ratings for the safety practice criteria. The table was normalised to facilitate the creation of the weighted normalised values. Equations (17), (18), (19) were used to normalise the aggregated values (Table 10).

Table 9.

Aggregated TFN for the ports’ safety practice.

| Criterion | A1 | A2 | A3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.188 | 0.438 | 0.625 |

| C12 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 0.313 | 0.500 | 0.688 |

| C13 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.125 | 0.313 | 0.563 |

| C14 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.188 | 0.375 | 0.563 | 0.188 | 0.375 | 0.563 |

| C15 |

0.438 |

0.688 |

0.875 |

0.563 |

0.813 |

1.000 |

0.375 |

0.625 |

0.750 |

| A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

|||||||

| C11 | 0.313 | 0.563 | 0.875 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 0.875 | 0.688 | 0.938 | 1.000 |

| C12 | 0.313 | 0.500 | 0.688 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 1.000 |

| C13 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.125 | 0.313 | 0.563 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 1.000 |

| C14 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.125 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.875 |

| C15 | 0.750 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.313 | 0.500 | 0.688 | 0.563 | 0.813 | 0.875 |

Table 10.

Normalised TFN for the ports’ safety practice.

| Criterion | A1 | A2 | A3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | 0.259 | 0.327 | 0.381 | 0.129 | 0.245 | 0.318 | 0.194 | 0.286 | 0.318 |

| C12 | 0.327 | 0.383 | 0.403 | 0.327 | 0.383 | 0.403 | 0.408 | 0.383 | 0.370 |

| C13 | 0.218 | 0.345 | 0.373 | 0.218 | 0.345 | 0.373 | 0.218 | 0.288 | 0.336 |

| C14 | 0.246 | 0.372 | 0.401 | 0.369 | 0.372 | 0.361 | 0.369 | 0.372 | 0.361 |

| C15 |

0.343 |

0.371 |

0.409 |

0.441 |

0.438 |

0.468 |

0.294 |

0.337 |

0.351 |

| A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

|||||||

| C11 | 0.323 | 0.368 | 0.445 | 0.517 | 0.490 | 0.445 | 0.712 | 0.613 | 0.508 |

| C12 | 0.408 | 0.383 | 0.370 | 0.163 | 0.287 | 0.336 | 0.653 | 0.575 | 0.538 |

| C13 | 0.218 | 0.345 | 0.373 | 0.218 | 0.288 | 0.336 | 0.873 | 0.691 | 0.597 |

| C14 | 0.246 | 0.372 | 0.401 | 0.246 | 0.248 | 0.321 | 0.739 | 0.620 | 0.561 |

| C15 | 0.588 | 0.540 | 0.468 | 0.245 | 0.270 | 0.322 | 0.441 | 0.438 | 0.409 |

Based on the information in Table 8, Table 10, the weighted normalised decision matrixes for the safety practice criteria were generated. The results obtained are presented in Table 11. Using an ideal solution of (1, 0, 0) and a non-ideal solution of (0, 0, 1), the alternatives' distances from the ideal and non-ideal solutions were generated.

Table 11.

Weighted normalised values for the ports’ safety practice criteria.

| Criterion | A1 | A2 | A3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | 0.110 | 0.156 | 0.206 | 0.055 | 0.117 | 0.172 | 0.082 | 0.136 | 0.172 |

| C12 | 0.087 | 0.097 | 0.095 | 0.087 | 0.097 | 0.095 | 0.108 | 0.097 | 0.087 |

| C13 | 0.035 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.035 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.035 | 0.043 | 0.045 |

| C14 | 0.024 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.037 | 0.029 | 0.021 | 0.037 | 0.029 | 0.021 |

| C15 |

0.019 |

0.016 |

0.012 |

0.024 |

0.018 |

0.014 |

0.016 |

0.014 |

0.011 |

| A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

|||||||

| C11 | 0.154 | 0.199 | 0.115 | 0.219 | 0.234 | 0.240 | 0.302 | 0.292 | 0.275 |

| C12 | 0.104 | 0.090 | 0.121 | 0.043 | 0.073 | 0.079 | 0.173 | 0.146 | 0.127 |

| C13 | 0.032 | 0.046 | 0.081 | 0.035 | 0.043 | 0.045 | 0.139 | 0.102 | 0.080 |

| C14 | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.099 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.019 | 0.073 | 0.049 | 0.033 |

| C15 | 0.025 | 0.016 | 0.161 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.024 | 0.018 | 0.012 |

Table 12 shows the ideal and non-ideal distances of the alternatives. The information here was used to generate the alternatives' closeness coefficients (Table 12).

Table 12.

Summary of the fuzzy TOPSIS results for the ports’ safety practice.

| Alternative | Alternative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 1.51 | 1.47 | 0.49 | A4 | 0.69 | 1.42 | 0.67 |

| A2 | 0.87 | 1.48 | 0.63 | A5 | 0.69 | 1.48 | 0.68 |

| A3 | 0.87 | 1.49 | 0.63 | A6 | 1.40 | 1.47 | 0.51 |

TOPSIS steps were utilised to generate closeness co-efficient values for the ports in terms of the safety culture criteria. Table 13 presents the aggregated TFN for the ports’ safety culture. Using Equations (17), (18), (19), the values in Table 13 were presented as well. Table 14 presents information about the normalised values for the safety culture criteria.

Table 13.

Aggregated TFN for the ports’ safety culture.

| Criterion | A1 | A2 | A3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C21 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.375 |

| C22 | 0.313 | 0.563 | 0.750 | 0.375 | 0.625 | 0.875 | 0.563 | 0.750 | 0.813 |

| C23 | 0.375 | 0.563 | 0.813 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 0.375 | 0.375 | 0.625 |

| C24 |

0.125 |

0.313 |

0.563 |

0.125 |

0.313 |

0.563 |

0.000 |

0.188 |

0.438 |

| A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

|||||||

| C21 | 0.000 | 0.063 | 0.313 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.000 | 0.250 | 0.500 |

| C22 | 0.500 | 0.688 | 0.813 | 0.188 | 0.438 | 0.625 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 1.000 |

| C23 | 0.250 | 0.438 | 0.688 | 0.250 | 0.438 | 0.688 | 0.438 | 0.688 | 0.875 |

| C24 | 0.125 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 0.125 | 0.188 | 0.438 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.625 |

Table 14.

Normalised TFN for the ports’ safety culture.

| Criterion | A1 | A2 | A3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C21 | 1.000 | 0.744 | 0.580 | 0.000 | 0.248 | 0.348 | 0.000 | 0.248 | 0.348 |

| C22 | 0.299 | 0.356 | 0.373 | 0.359 | 0.396 | 0.435 | 0.539 | 0.475 | 0.404 |

| C23 | 0.462 | 0.450 | 0.446 | 0.308 | 0.400 | 0.411 | 0.462 | 0.300 | 0.343 |

| C24 |

0.447 |

0.456 |

0.437 |

0.447 |

0.456 |

0.437 |

0.000 |

0.274 |

0.340 |

| A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

|||||||

| C21 | 0.000 | 0.124 | 0.290 | 0.000 | 0.248 | 0.348 | 0.000 | 0.496 | 0.464 |

| C22 | 0.479 | 0.435 | 0.404 | 0.180 | 0.277 | 0.311 | 0.479 | 0.475 | 0.498 |

| C23 | 0.308 | 0.350 | 0.377 | 0.308 | 0.350 | 0.377 | 0.538 | 0.550 | 0.480 |

| C24 | 0.447 | 0.365 | 0.389 | 0.447 | 0.274 | 0.340 | 0.447 | 0.548 | 0.486 |

Based on the information in Table 7, Table 14, the weighted normalised decision matrixes for the safety culture criteria were generated. Table 15 below contains the weighted normalised values for the ports’ safety culture.

Table 15.

Weighted normalised values for the ports’ safety culture.

| Criterion | A1 | A2 | A3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C21 | 0.479 | 0.394 | 0.344 | 0.000 | 0.131 | 0.206 | 0.000 | 0.131 | 0.206 |

| C22 | 0.082 | 0.094 | 0.093 | 0.098 | 0.105 | 0.108 | 0.148 | 0.126 | 0.101 |

| C23 | 0.072 | 0.060 | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.053 | 0.043 | 0.072 | 0.040 | 0.036 |

| C24 |

0.040 |

0.033 |

0.023 |

0.040 |

0.033 |

0.023 |

0.000 |

0.020 |

0.018 |

| A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

|||||||

| C21 | 0.000 | 0.074 | 0.290 | 0.000 | 0.131 | 0.206 | 0.000 | 0.263 | 0.275 |

| C22 | 0.127 | 0.108 | 0.121 | 0.049 | 0.073 | 0.077 | 0.131 | 0.126 | 0.124 |

| C23 | 0.041 | 0.037 | 0.174 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.040 | 0.085 | 0.073 | 0.050 |

| C24 | 0.032 | 0.019 | 0.174 | 0.040 | 0.020 | 0.018 | 0.040 | 0.039 | 0.026 |

The summarised values for the ports’ safety culture are presented in Table 16. In this table, the alternatives' distance from the ideal solutions was generated by using (1, 0, 0) as the ideal solutions for the safety culture criteria. (0, 0, 1) was used as the non-ideal solution for the safety culture criteria to obtain the alternatives' distance from the non-ideal solutions. The relationship between these distances was used to generate the alternatives’ closeness coefficient (Equation (23)).

Table 16.

Summary of the fuzzy TOPSIS results for the ports’ safety culture.

| Alternative | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 1.26 | 1.33 | 0.51 | A4 | 0.79 | 1.16 | 0.60 |

| A2 | 0.77 | 1.29 | 0.63 | A5 | 0.79 | 1.30 | 0.62 |

| A3 | 1.15 | 1.30 | 0.53 | A6 | 1.36 | 1.28 | 0.48 |

Using the closeness coefficients in Table 12, Table 16, information was generated in Fig. 5. From this figure, A5 had the best performance in terms of safety practices, while A1 had the worst performance. The overall ranking of the ports with respect to safety practice is: . Fig. 5 also showed that A2 had the best performance in terms of the safety culture, while A6 had the worst performance. The overall ranking of the ports with respect to safety culture is: .

Fig. 5.

Ranking of the alternatives with safety policy and culture.

Pearson correlation was utilised to evaluate whether or not there is a significant difference between safety practice and safety culture results. The closeness co-efficient values for safety practices and safety culture values were used as input parameters. The analysis generated a Pearson correlation value of 0.834. This result showed no significant difference between the closeness co-efficients for safety practices and safety cultures because the table value for df = 4 at a 10% confidence interval is 0.959.

4.3. Fuzzy WASPAS results

Ports’ normalised values (Table 10, Table 14) were used. The criteria importance (Table 7, Table 8) also served to generate the ports’ WASPAS values. Equation (20) was used to convert the normalised values for the safety practice and safety culture to single values. The alternatives’ weighted sum values were obtained using Equation (21), while Equation (22) generated the weighted product values for the alternatives. Table 17 contains the alternatives’ weighted sum and weighted product values. These values were used to determine the aggregating co-efficient for the decision making problem (Equation (24)). This co-efficient was used to calculate the alternatives’ WASPAS values (Table 17).

Table 17.

Summary of the fuzzy WASPAS results.

| Safety practice | Safety culture | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port | WAS | WAP | WASPAS | Port | WAS | WAP | WASPAS |

| A1 | 0.168 | 0.174 | 0.342 | A1 | 0.269 | 0.297 | 0.566 |

| A2 | 0.150 | 0.152 | 0.302 | A2 | 0.142 | 0.147 | 0.289 |

| A3 | 0.155 | 0.159 | 0.313 | A3 | 0.142 | 0.142 | 0.284 |

| A4 | 0.196 | 0.190 | 0.386 | A4 | 0.147 | 0.107 | 0.253 |

| A5 | 0.184 | 0.183 | 0.366 | A5 | 0.120 | 0.128 | 0.248 |

| A6 | 0.300 | 0.310 | 0.610 | A6 | 0.210 | 0.223 | 0.433 |

Based on the WASPAS values in Table 17, the ports were ranked (Fig. 6). The A6 performed the best in terms of safety practice, while A2 performed the worst. The overall ranking of the ports in regard to safety practice is: . A1 had the worst performance in terms of safety culture, according to Fig. 6. Same way, A5 had the highest performance overall. According to the safety culture, the ports ranking is: .

Fig. 6.

WASPAS ranking for the alternatives.

4.4. Managerial implications

Some of the managerial implications of the information generated in the paper are highlighted as follows.

The outcomes of the framework will make it possible for stakeholders to comprehend how the selected criteria would affect the safety of a seaport. They will be able to direct additional resources, for instance, toward resolving issues considered crucial to safety practice and culture. Hence, the following steps are recommended for the framework implementation:

-

•

Step 1: Select the safety practice and culture criteria for the decision making process. This would involve determining the objectives of the decision making process and the criteria that would be used to evaluate the SMCI.

-

•

Step 2: Gather the necessary data and information to evaluate the criteria from industry experts.

-

•

Step 3: Calculate the weights for each of the criteria. This can be done through a SWARA (Simple Weight Assessment and Rating Technique) process.

-

•

Step 4: Generate numeric values for the ports using the selected criteria. This can be done through a TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution) process.

-

•

Step 5: Using the criteria weights and the TOPSIS results, rank the ports to decide which is the best.

Stakeholders will have the chance to describe each port's advantages using the proposed framework. The suggested framework will help stakeholders address safety improvement areas in this connection. An internal and external benchmarking system might be created using the knowledge of each port's strengths and weaknesses.

5. Conclusions

Seaports in developing countries are restructuring to meet the demand for improved SCMI management. Considering the multiplicity of criteria for SCMI management, MCDM framework is best suited for this problem. Hence, presented in the paper is a framework containing three MCDM methods: SWARA, TOPSIS, and WASPAS methods for SCMI management. It contains five safety practice criteria, such as people's safety, property's safety and monitoring capabilities. It equally contains four safety culture criteria, which include: learning from experience and inter-element collaboration. The proposed framework’s performance was evaluated using qualitative information drawn from experts in the Nigerian maritime industry. Using a questionnaire, the experts provided qualitative information on six ports in Nigeria: Tin can island port: A1; Lagos port complex: A2; Calabar port: A3; Port Harcourt: A4; Delta port: A5; and Onne port. The following conclusions are, therefore, arrived at:

-

•

People's lives, the most important safety practice criterion, accounted for about 47.90% of the evaluation of the critical SCMI for seaports. Learning from experience, the most important safety culture criterion made up approximately 53.20% of how the SCMI was evaluated in terms of safety culture.

-

•

In terms of safety practice, the TOPSIS method ranked the ports as: , while the WASPAS method ranked the ports as: .

-

•

In terms of the safety culture, the TOPSIS method ranked the ports as , while the WASPAS ranked the ports as: .

The paper did not include the impact of institutional bureaucracy on the administration of SCMI. However, it could form the basis for further research. The opinions of experts were considered vital to the discussion in the paper. A follow-up paper can extend the discussion and compare its findings with those here. Creating a machining learning system for SCMI management automation is another area for future research, which might involve using sustainability factors for SCMI.

Funding statement

This research is supported by the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Author contribution statement

Desmond Eseoghene Ighravwe: Conceived and designed the analysis; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper. Daniel Mashao: Conceived and designed the analysis; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their appreciation to key stakeholders in the Nigerian port authority who contributed, by way of giving expert opinions, to the paper. Also, reviewers’ comments are appreciated. They really improved the paper’s quality. The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Appendix 1. A sample Questionnaire survey

Based on your team’s experience in safety-critical maritime infrastructure, I seek your assistance in filling out the questionnaire below. All information provided will be used for academic purposes only.

Q1. How important are the following factors regarding safety-critical infrastructure in the maritime industry?

| S/N | Factor | Extremely important | Highly important | Moderately important | Unimportant | Highly Unimportant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | People’s safety | |||||

| 2 | Lack of facility maintenance | |||||

| 3 | Property’s safety | |||||

| 4 | Breaches in physical security/information security | |||||

| 5 | Inter-element collaboration | |||||

| 6 | Anticipate risk events and opportunities | |||||

| 7 | Respond to regular and irregular threats in a robust yet flexible manner | |||||

| 8 | Monitoring capabilities | |||||

| 9 | Learning from experience |

Q2. How would you rate safety critical maritime infrastructure in Tin Can Island port with respect to the following factors?

| S/N | Factor | Extremely high | Very high | High | Low | Very low |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | People’s safety | |||||

| 2 | Lack of facility maintenance | |||||

| 3 | Property’s safety | |||||

| 4 | Breaches in physical security/information security | |||||

| 5 | Inter-element collaboration | |||||

| 6 | Anticipate risk events and opportunities | |||||

| 7 | Respond to regular and irregular threats in a robust yet flexible manner | |||||

| 8 | Monitoring capabilities | |||||

| 9 | Learning from experience |

References

- 1.Wan C., Yan X., Zhang D., Qu Z., Yang Z. An advanced fuzzy Bayesian-based FMEA approach for assessing maritime supply chain risks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019;125:222–240. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang B., Shen Y., Saravanan V., Luhach A.K. Workplace safety and risk analysis using additive heterogeneous hybridized computational model. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zelenkov M., Laamarti Y., Charaeva M., Rogova T., Novoselova O., Mongush A. Maritime terrorism as a threat to confidence in water transport and logistics systems. Transp. Res. Procedia. 2022;63:2259–2267. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carafano J.J., Andersen M.E. Trade security at sea: setting national priorities for safeguarding America’s economic lifeline. Backgrounder. 2006;1930:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keshk A.M. Maritime Security of the Arab Gulf States. Springer; 2022. Mechanisms of the arabian gulf countries to safeguard maritime security; pp. 81–116. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ighravwe D., Anyaeche C. A comparison of ARIMA and ANN techniques in predicting port productivity and berth effectiveness. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2019;3(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Peña Zarzuelo I., Soeane M.J.F., Bermúdez B.L. Industry 4.0 in the port and maritime industry: a literature review. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2020;20 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentaleb F., Mabrouki C., Semma A. ‘A multi-criteria approach for risk assessment of dry port-seaport system’, presented at the. Supply Chain Forum Int. J. 2015;16(4):32–49. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Şenel M., Şenel B., Havle C.A. presented at the ITM Web of Conferences. Vol. 22. 2018. Risk analysis of ports in Maritime Industry in Turkey using FMEA based intuitionistic Fuzzy TOPSIS Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan X., Wan C., Zhang D., Yang Z. Safety management of waterway congestions under dynamic risk conditions—a case study of the Yangtze River. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017;59:115–128. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou X., Cheng L., Li M. Assessing and mapping maritime transportation risk based on spatial fuzzy multi-criteria decision making: a case study in the South China sea. Ocean Eng. 2020;208 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khorram S. A novel approach for ports’ container terminals’ risk management based on formal safety assessment: FAHP-entropy measure—VIKOR model. Nat. Hazards. 2020;103(2):1671–1707. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mokhtari K., Ren J., Roberts C., Wang J. Decision support framework for risk management on sea ports and terminals using fuzzy set theory and evidential reasoning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012;39(5):5087–5103. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duran C.A., Palominos F., Cordova F.M. Applying multi-criteria analysis in a port system. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017;122:478–485. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narasimha P.T., Jena P.R., Majhi R. Sustainability performance assessment framework for major seaports in India. Environment. 2022;4(15):20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varese E., Bux C., Amicarelli V., Lombardi M. Assessing dry ports’ environmental sustainability. Environments. 2022;9(9):117. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Görçün Ö.F. Efficiency analysis of Black sea container seaports: application of an integrated MCDM approach. Marit. Pol. Manag. 2021;48(5):672–699. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pamucar D., Faruk Görçün Ö. Evaluation of the European container ports using a new hybrid fuzzy LBWA-CoCoSo’B techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022;203 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ighravwe D., Aikhuele D., Fayomi O., Basil A. Adoption of a multi-criteria approach for the selection of operational measures in a maritime environment. J. Proj. Manag. 2022;7(1):53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim D., Kim S. Multi criteria decision on selecting optimal ship accident rate for port risk mitigation. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2009;25(1):7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 21.HashemkhaniZolfani S., Yazdani M., Zavadskas E.K. An extended step-wise weight assessment ratio analysis (SWARA) method for improving criteria prioritisation process. Soft Comput. 2018;22(22):7399–7405. doi: 10.1007/s00500-018-3092-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tripathi D., Nigam S.K., Mishra A.R., Shah A.R. A novel intuitionistic fuzzy distance measure-SWARA-COPRAS method for multi-criteria food waste treatment technology selection. Oper. Res. Eng. Sci. Theory Appl. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siksnelyte-Butkiene I., Zavadskas E.K., Streimikiene D. Multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) for the assessment of renewable energy technologies in a household: a review. Energies. 2020;13(5):1164. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ighravwe D.E., Oke S.A. A multi-attribute framework for determining the competitive advantages of products using grey-TOPSIS cum fuzzy-logic approach. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2018;29(7–8):762–785. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ighravwe D.E., Oke S.A. A fuzzy-grey-weighted aggregate sum product assessment methodical approach for multi-criteria analysis of maintenance performance systems. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2017;8(2):961–973. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang T.-C., Lee H.-D. Developing a fuzzy TOPSIS approach based on subjective weights and objective weights. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009;36(5):8980–8985. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarbakhshnia N., Soleimani H., Ghaderi H. Sustainable third-party reverse logistics provider evaluation and selection using fuzzy SWARA and developed fuzzy COPRAS in the presence of risk criteria. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018;65:307–319. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turskis Z., Zavadskas E.K., Antucheviciene J., Kosareva N. A hybrid model based on fuzzy AHP and fuzzy WASPAS for construction site selection. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control. 2015;10(6):113–128. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nwanosike F.O., Tipi N.S., Warnock-Smith D. Productivity change in Nigerian seaports after reform: a Malmquist productivity index decomposition approach. Marit. Pol. Manag. 2016;43(7):798–811. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onwuegbuchunam D. Assessing port governance, devolution and terminal performance in Nigeria. Logistics. 2018;2(1):6. doi: 10.3390/logistics2010006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filipiak – Kowszyk D., Kamiński W. The application of kalman filtering to predict vertical rail Axis displacements of the overhead crane being a component of seaport transport structure. Pol. Marit. Res. 2016;23(2):64–70. doi: 10.1515/pomr-2016-0022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou X., et al. Integrating island spatial information and integer optimisation for locating maritime search and rescue bases: a case study in the South China sea. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019;8(2):88. doi: 10.3390/ijgi8020088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.John A., Nwaoha T.C. Safety critical maritime infrastructure systems resilience: a critical review. Int. J. Marit. Eng. 2016;158:209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollnagel E., Woods D.D., Leveson N., editors. Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts. Ashgate; Aldershot, England ; Burlington, VT: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zarbakhshnia N., Soleimani H., Ghaderi H. Sustainable third-party reverse logistics provider evaluation and selection using fuzzy SWARA and developed fuzzy COPRAS in the presence of risk criteria. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018;65:307–319. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrović Goran J.M.Ž., Marinković D. Comparison of three fuzzy MCDM methods for solving the supplier selection problem. Facta Univ. – Ser. Mech. Eng. 2019;17(3):455–469. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.