Abstract

The oxidation resistance of TiC/Ni composites is crucial for its application in high-temperature oxidation environment. The in-situ TiC/Ni composites are fabricated by reactive sintering method, and the influence of TiC particle size on oxidation resistance of composite is studied. The particle size of TiC increases from 1.54 μm to 2.40 μm as the sintering holding time prolongs from 2 h to 6 h, due to the dissolution-reprecipitation mechanism. The oxidation kinetics of in-situ TiC/Ni composite with different TiC particle size oxidized at 800 °C for 100 h obeys parabolic kinetics. The oxidation mass gain of composite increases from 7.471 mg•cm−2 to 8.454 mg•cm−2, and the oxide scale on composites becomes thicker, as the particle size of TiC increases from 1.54 μm to 2.40 μm. The reduction of TiC particle size facilitates the formation of a dense and continuous oxide scale on composite, helpful to restrict the diffusion of O, Ti and Ni atoms during oxidation. Therefore, the reduction of TiC particle size is contributed to the optimization of oxidation resistance of in-situ TiC/Ni composites.

Keywords: TiC/Ni composite, Oxidation resistance, TiC particle size

1. Introduction

As an important part of the solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) battery pack, the interconnects mainly play the role of transferring electrons between adjacent single cells and separating fuel and oxidizer [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. The interconnects materials require high electrical conductivity, proper thermal expansion coefficient, and good oxidation resistance [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. TiC/Ni composites have both of metallic properties and ceramic characteristics, and are wildly applied in a diverse array of fields, such as aerospace, transportation vehicles, interconnects, electronic components and ceramic cutting tools [2,4,8,[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]]. Especially, TiC/Ni composites have been proposed as promising candidates for interconnect materials in intermediate temperature SOFC (IT-SOFC) owing to their suitable coefficient of thermal expansion and good electrical conductivity [11,13,[16], [17], [18], [19]]. The oxidation resistance is one important factor for the operation life of interconnects, and the key investigation is to improve the oxidation resistance of TiC/Ni composites.

The grain size exerts a crucial effect on the oxidation resistance of composites. Guo-Jian Cao et al. [20] prepared the (TiB2+TiC)/Ni3Al composite by SPS method and indicated that the reduction of grain size contributed to the enhancement of oxidation resistance, resulted from the formation of an inner layer of Al2O3 and a continuous outer layer composed of TiO2 on the surface of composite. Yeong-Hwan Lee et al. [21] investigated the impact of particle size of TiC on the high-temperature oxidation resistance of TiC reinforced stainless steel and demonstrated that a decrease of particle size of TiC from 3 μm to 1 μm yields a remarkable reduction of approximately 90% in the mass gain of composites. This remarkable reduction can be attributed to the thin layer of thermally stable titanium oxides on the composite. Besides, the oxidation resistance of TiC/hastelloy (Ni–Cr–Mo alloy) composites could also be improved by reducing the particle size of TiC, which accelerated the formation of a continuous and dense oxide scale consisted of TiO2 and Cr2O3 [22]. Hence, the oxidation resistance of in-situ TiC/Ni composites is also probably influenced by the particle size of TiC (dTiC), which is seldom investigated at present.

The grain size of composites fabricated by sintering is affected by many factors, including heating temperature, holding time, heating speed, and other external factors [[23], [24], [25]]. Randall M et al. [26] stated that the grain size exhibited an increase with the extension of sintering time, according to the “Ostwald ripening” model, in which the smaller grains underwent dissolution, diffusion through the liquid medium, and subsequent precipitation onto the larger grains. Zhuo Tian et al. [23] prepared the boron nitride matrix textured ceramics by a combination of hot-pressing sintering and grain rearrangement facilitated by Digital Light Processing (DLP) technology, and explored the effect of holding time on the grain size of the boron nitride matrix textured ceramics. It is found that the grain size increases nonlinearly with the extension of sintering time. Li-Xia Cheng et al. [27] also found that the holding time acted a crucial role in influencing the grain growth and densification of TiC fabricated by SPS. Matsubara H et al. [28] found a linear relationship between the cube of mean particle size and sintering time in TiC–Ni and TiC–Mo2C–Ni alloys. N.J. Lóh et al. [29] have also found that the size of alumina particles in alumina ceramics fabricated by two-step sintering increases with the extension of holding time at the same temperature. Therefore, the TiC particle size of TiC/Ni composites prepared by reactive sintering method can also be adjusted by changing the sintering holding time.

In this work, the reactive sintering method was adopted to fabricate TiC/Ni composite, and the dTiC was altered by changing the sintering holding time. The mass gain, phase composition and microstructure of oxide scale formed on composites with different dTiC were investigated to comprehensively understand the effect of dTiC on oxidation resistance of TiC/Ni composite.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Materials preparation

Ti, Ni, Ta, and graphite particles (particle size 1 μm, 99.9% purity, BoWei Applied Materials Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai) were homogeneously blended with 3 wt% polyvinyl butyral (as a binder) in ethanol through a ball milling process for 240 min. The ball milling was conducted in a planetary mill (model QM-3SP4) at a rotational speed of 300 rpm. Subsequently, the resulting mixture was subjected to drying, crushing, and sieving operations. Simultaneously, TiC media balls were employed at a ball-to-powder ratio of 3:1, as elaborated in our previous research [30]. Additionally, the composition of TiC/Ni composites was outlined in Table 1. Subsequently, the elemental powders were pressed into small cubic with 10 × 10 × 3 mm3 under a pressure of 4 MPa, which was then isostatic pressed at 200 MPa. Afterwards, the green body was sintered at 1360 °C in argon atmosphere (99.9%) and holding for 2, 4, and 6 h, respectively. As we all know, one of the crucial aspects of sintering is the density. Further, the relative density of composites sintered for 2, 4, and 6 h are higher than 96%. In our original research process, we conducted a detailed study on the relative density of composite materials [30].

Table 1.

The composition of green body.

| Titanium | Nickel | Graphite | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green body | 36.00 wt% | 55.00 wt% | 9.00 wt% |

2.2. Characterization

XRD (Rigaku Ultima IV, λ = 1.54178) was used to examine the phase composition of TiC/Ni composite before and after oxidation. The microstructure analysis of composites was conducted using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Apreo S HiVac, Thermo Fay, USA) in combination with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS). Besides, the mean particle size was determined by calculating the mean value of the intercept length (using Nano Measurer software) across approximately 500 particles. The oxidation resistance of composites was evaluated by the cyclic oxidation method. Moreover, the tested samples were cut into 8 × 8 × 3 mm3. The samples polished and cleaned. Oxidation mass gain of samples was measured through intermittent exposure of the specimens to static air at 800 °C for 100 h using a high-precision electronic microbalance (AUW-120D) with an accuracy of 10−4 g. In particular, the mass gain was the average value of three specimens, which were simultaneous heated. Consequently, the oxidation rate constants () at various temperatures were fitted to Eq. (1) [31] using the following equation:

| (1) |

In which represents weight gain per unit area (mg cm−2), means the oxidation rate constant (mg2•cm−4•h−1) and represents the oxidation time (h).

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Phase and microstructure of in-situ TiC/Ni composites

As shown in Fig. 1, the XRD patterns of green body and TiC/Ni composites after reactive sintering are compared. Based on Fig. 1(a), the green body is composed of Ti, Ni, and graphite. After sintering, the composites are consisted of TiC and Ni phases, proved by Fig. 1(b). Therefore, the TiC/Ni composites are successfully obtained by reactive sintering, and the reaction mechanism has been explained detailly in our previous study [30].

Fig. 1.

XRD patterns of (a) green body and (b) TiC/Ni composites after sintering.

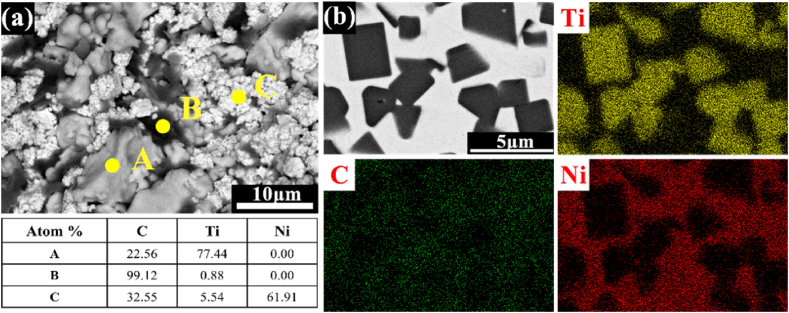

Fig. 2 shows the microstructure characteristics of green body and TiC/Ni composites after sintering. Based on the EDS analysis conducted at points A, B, and C in Fig. 2(a), the bright white flower cluster particles are corresponding to Ni, the large irregular polygonal gray particles are Ti, and the black region exhibits a flake-like structure is consistent with graphite. Those particles are homogeneously distributed in the green body and mutually contact. By contrast, according to the EDS mapping of Ni, Ti, and C elements in Fig. 2(b), TiC particles with distinctive black cubic structure are uniformly distributed in Ni matrix in TiC/Ni composites.

Fig. 2.

SEM-EDS results of (a) green body and (b) in-situ TiC/Ni composites.

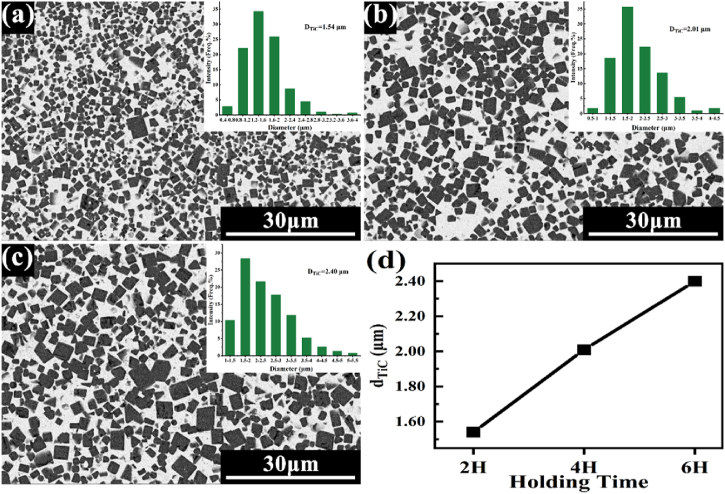

Fig. 3 presents the microstructure characterization and dTiC of TiC/Ni composites with different sintering holding time. Thereinto, the dTiC was determined through calculating the mean value of the intercept length (using Nano Measurer software) across approximately 500 particles. Besides, the particle size distribution was shown in Fig. 3 (a) ∼(c). As presented in Fig. 3 (d), dTiC exhibits an increase from 1.54 μm to 2.40 μm with an extension of the holding time from 2 h to 6 h. The evolution of the microstructure in in-situ TiC/Ni composites is governed by the phenomenon of “Ostwald ripening.” [32]. The fine grains dissolve, diffuse through liquid phase and then reprecipitate on large grains [33]. The “Ostwald ripening” process is prolonged by increasing the sintering holding time, which is resulted in the rise of TiC particle size.

Fig. 3.

SEM images of in-situ TiC/Ni composites with different sintering holding time: (a) 2 h, (b) 4 h, (c) 6 h and (d) TiC particle size of composites with different sintering holding time.

3.2. The oxidation resistance of TiC/Ni composites with different dTiC

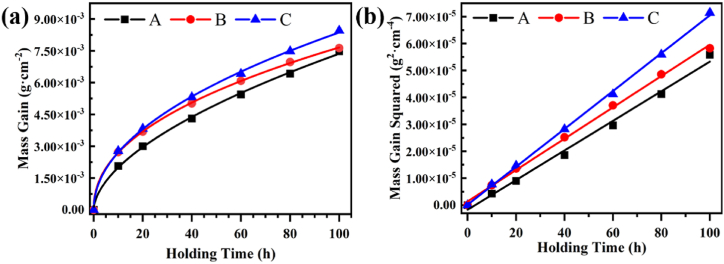

Fig. 4(a) presents that the mass gain evolution at 800 °C as a function of holding time of TiC/Ni composite with different dTiC obeys parabolic kinetics law, which implies that atoms diffusion play a crucial role in the oxidation mechanism [34,35]. The oxidation mass gain increases from 7.47 mg cm−2 to 8.45 mg cm−2 with the increase of dTiC from 1.54 μm to 2.40 μm. The goodness of fit for the linear relationship between the square of mass gain of composite with oxidation time is exhibited in Fig. 4(b). Besides, the goodness of fit of each curve is higher than 0.9 (Curves A, B and C are 0.93, 0.95 and 0.91, respectively), which calculated by matching with the function. As shown in Fig. 4(b), the square of mass gain of composite with different dTiC has a good linear relationship with oxidation time, and the slope of corresponding lines represents the parabolic rate constant of composites. Table 2 displays the holding time, dTiC, mass gain and oxidation rate. It is obvious that dTiC rises with the extension of holding time, resulting in the increase of mass gain and oxidation rate.

Fig. 4.

(a) Mass gain curves and (b) the squared mass gain curves of samples oxidized at 800 °C for 100 h. The samples with sintering holding time of 2 h, 4 h, and 6 h are labeled as A, B, and C, respectively.).

Table 2.

The mass gain and oxidation kinetics data of samples with different sintering holding time.

| Holding Time(h) | dTiC(μm) | Mass Gain (mg•cm−2) | (mg2•cm−4•h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1.54 | 7.47 | 5.49 × 10−1 |

| 4 | 2.01 | 7.63 | 5.83 × 10−1 |

| 6 | 2.40 | 8.45 | 7.02 × 10−1 |

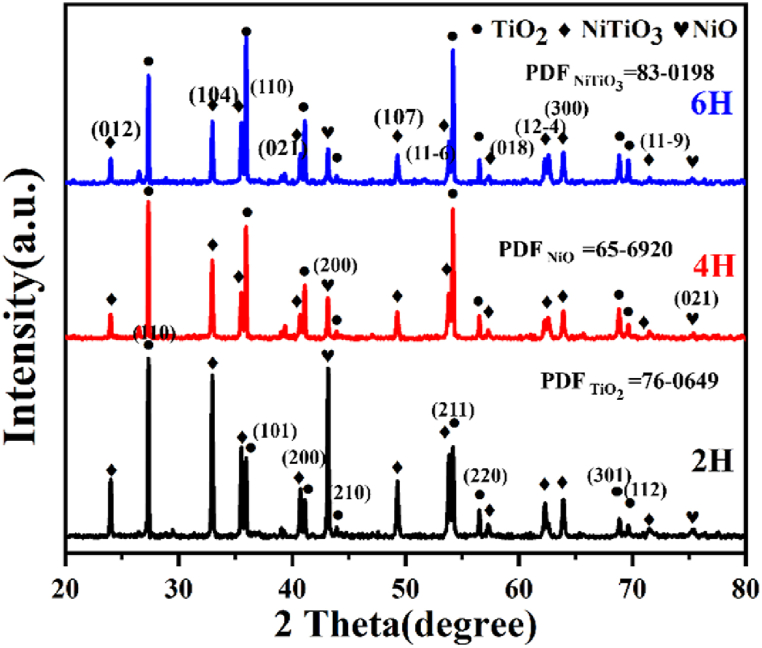

Fig. 5 presents the phase composition of composite with different dTiC after oxidation, which is mainly consisted of NiO, TiO2, and NiTiO3. Nevertheless, a gradual decline is observed in the relative intensity of TiO2 peaks, and relative intensity of NiO and NiTiO3 peaks strengthen, as the dTiC of composites decreases.

Fig. 5.

Phase composition of in-situ TiC/Ni composites after 100 h of oxidation with different dTiC.

3.3. The morphology of oxide scales on samples with different dTiC

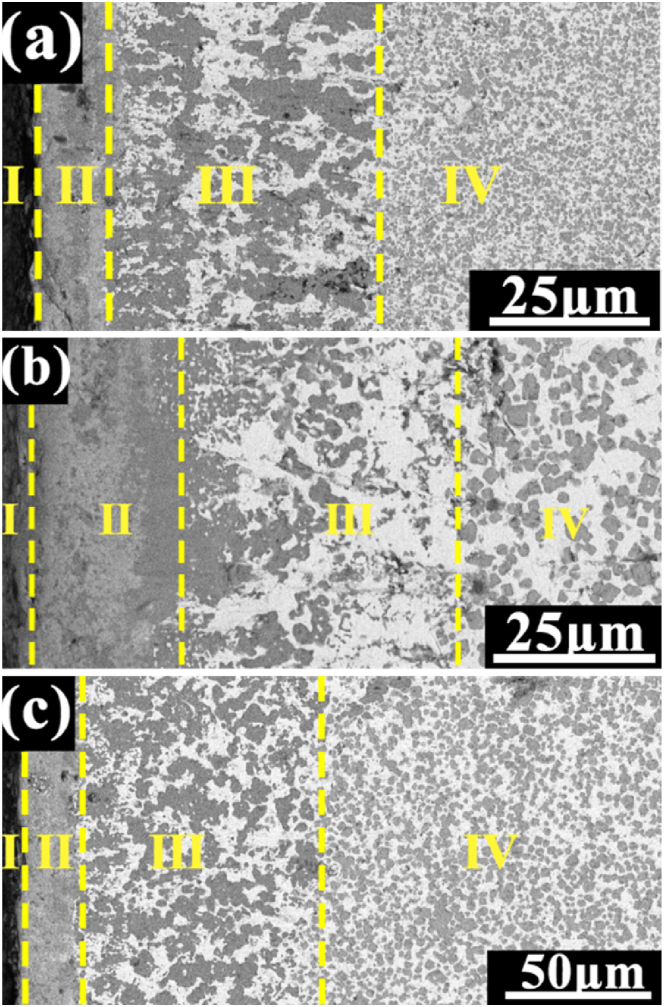

The morphology of oxide scale on TiC/Ni composites with different dTiC presented in Fig. 6 illustrates that the two-layered structure of oxide scales is formed. Obviously, both the inner and outer oxide layer gradually increase as the dTiC increases from 1.54 μm to 2.40 μm. Correspondingly, the thickness of oxide scale is listed in Table 3.

Fig. 6.

The scanning electron microscopy images of the cross-section of the oxide scale formed on the in-situ TiC/Ni composite with different sintering holding times following an oxidation test conducted at 800 °C for 100 h: (a) 2 h, (b) 4 h, and (c) 6 h (Ⅰ: surface; Ⅱ: the outer oxide layer; Ⅲ: the inner oxide layer; Ⅳ: substrate.)

Table 3.

The thickness of oxide scale on samples with different dTiC.

| Holding Time(h) | dTiC(μm) | Outer Oxide Layer Thickness (μm) | Inner Oxide Layer Thickness (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1.54 | 11.42 | 41.98 |

| 4 | 2.01 | 22.17 | 45.11 |

| 6 | 2.40 | 24.46 | 76.68 |

In our previous research, the oxidation mechanism of in-situ TiC/Ni composites has been studied in detail [36]. The oxide scale on composite is revealed to be distinct layered structure, which is consisted of two distinct layers. The outer layer is composed of an upper section consisting of TiO2, NiTiO3, and NiO, while the lower section primarily containing TiO2. TiO2 islands dispersed in Ni matrix forms the inner layer. The oxidation mechanism is governed by the inward diffusion of O atom and the outward diffusion of Ti and Ni atoms. Notably, the predominant factor is the inward diffusion of O atom. As is known, the limited factor for TiO2 formation is the number of potential nucleation sites [20]. In addition, the smaller dTiC generates larger grain boundary, which can provide more nucleation sites [37]. Therefore, there are more nucleation sites on the surface of in-situ TiC composite with 1.54 μm dTiC, which is benefit to the horizontal extension of TiO2 to form continuous and dense oxide scale to inhibit the diffusion of O, Ti and Ni atoms, resulting in the thinner outer and inner oxide scale and better oxidation resistance. In addition, larger grain boundary between TiC and Ni also accelerates the reaction of TiO2 and NiO to form NiTiO3, which results in the higher relative peak intensity of NiTiO3 and lower relative peak intensity of TiO2 in TiC/Ni composites with smaller dTiC. By contrast, the rise of dTiC leads to a reduction of nucleation sites number, which leads to the inhibition of lateral growth of TiO2 and promotion of vertical growth of TiO2. Consequently, the TiC/Ni composites exhibits better oxidation resistance as the dTiC decreases.

4. Conclusions

The in-situ TiC/Ni composite was prepared by reactive sintering, and the influence of dTiC on the oxidation resistance of composites was investigated. The TiC particle size can be altered by changing the sintering holding time, and the dTiC increases from 1.54 μm to 2.40 μm as the sintering holding time increases from 2 h to 6 h. The oxidation process of composite with different dTiC conforms to the law of parabolic dynamics. In addition, the oxidation weight gain and oxidation rate increase with the increase of dTiC. besides, the dTiC show no obvious effect on the phase composition of oxide scale on composite. The decrease of dTiC promoted the formation of dense and continuous oxide scale to inhibits the diffusion of O, Ti, and Ni atoms during oxidation, leading to the thinner oxide scale and better oxidation resistance.

Author contribution statement

Ziyan Zhao: Performed the experiments; analyzed and interpreted the data; wrote the paper. Qian Qi: Conceived and designed the experiments; contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. Lujie Wang: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. Kaiyue Zheng, Xianghui Yu, and Shuyu Yao: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.52101177) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2020QE003).

Contributor Information

Ziyan Zhao, Email: zhaoziyanzhe@163.com.

Qian Qi, Email: qiqian717@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Stambouli, et al. Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs): a review of an environmentally clean and efficient source of energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2002;6(5):433–455. doi: 10.1016/S1364-0321(02)00014-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Z., et al. Selection and evaluation of heat-resistant alloys for SOFC interconnect applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003;150(9):A1118–A1201. doi: 10.1149/1.1595659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qi Q., Liu Y., Huang Z. Promising metal matrix composites (TiC/Ni–Cr) for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) interconnect applications. Scripta Mater. 2015;109:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2015.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar V., et al. Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Elsevier; 2020. Stacking designs and sealing principles for IT-solid oxide fuel cell; pp. 379–410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasudevan N., et al. Effect of Ni addition on the densification of TiC: a comparative study of conventional and microwave sintering. Int. J. Refract. Metals Hard Mater. 2020;87:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.105165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahato N., et al. Progress in material selection for solid oxide fuel cell technology: a review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015;72:141–337. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2015.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu W., et al. Optimizing the microstructure and mechanical behaviors of in-situ TiC-γ′/Ni composites by subsequent thermal treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2019;774:739–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.10.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Z.-d., et al. Microstructure and mechanical behaviors of in situ TiC particulates reinforced Ni matrix composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2010;527(16–17):3898–3903. doi: 10.1016/j.msea.2010.02.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao M., et al. Microstructure and Oxidation Mechanism of Multiphase Mo–Ti–Si–B Alloys at 800 °C. Corrosion Sci. 2021;vol. 187 doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang Y., Xie Hua, Koc R. Investigation of electrical conductivity and oxidation behavior of TiC and TiN based cermets for SOFC interconnect application. ECS Trans. 2007;7(2427):2427–2435. doi: 10.1149/1.2729365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajabi A., et al. Development and application of tool wear: a review of the characterization of TiC-based cermets with different binders. Chem. Eng. J. 2014;255:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2014.06.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolton J.D., Gant A.J. Microstructural development and sintering kinetics in ceramic reinforced high speed steel metal matrix composites. Powder Metall. 2013;40(2):143–151. doi: 10.1179/pom.1997.40.2.143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi Q., et al. The formation mechanism of TiC particles in TiC/Ni composites fabricated by in situ reactive infiltration. J. Mater. Sci. 2016;51(14):7038–7045. doi: 10.1007/s10853-016-9994-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon H., Suh C.-Y. Effects of Ni content and sintering temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of TiC-Ni composites fabricated by selective carburization of Ti-Ni alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2020;834 doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.155000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian W., et al. New numerical algorithm for the periodic boundary condition for predicting the coefficients of thermal expansion of composites. Mech. Mater. 2021;154 doi: 10.1016/j.mechmat.2020.103737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fergus J.W. Metallic interconnects for solid oxide fuel cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2005;397(1–2):271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.msea.2005.02.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu W.Z., Deevi S.C. Development of interconnect materials for solid oxide fuel cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2003;348(1–2):227–243. doi: 10.1016/s0921-5093(02)00736-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pang Y., H.X.a.R.K. Investigation of electrical conductivity and oxidation behavior of TiC and TiN based cermets for SOFC interconnect application. ECS Trans. 2007;7:2427–2435. doi: 10.1149/1.2729365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boutefnouchet H., et al. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis mechanisms within the Ti–C–Ni system: a time resolved X-ray diffraction study. Powder Technol. 2012;217:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2011.10.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao G.-j., et al. Grain size effect on cyclic oxidation of (TiB2+ TiC)/Ni3Al composites. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China. 2012;22(7):1588–1593. doi: 10.1016/S1003-6326(11)61360-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee Y.-H., et al. Effect of TiC particle size on high temperature oxidation behavior of TiC reinforced stainless steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019;480:951–955. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.02.138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi Q., et al. The oxidation resistance optimization of titanium carbide/hastelloy (Ni-based alloy) composites applied for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cell interconnects. J. Power Sources. 2017;359:626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.05.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian Z., et al. The effects of holding time on grain size, orientation degree and properties of h-BN matrix textured ceramics. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020;248 doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.122916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volkova N.M., Dudorova T.A., Gurevich Y.G. Influence of hold time on carbidegrain growth in TiC-Ni alloys. Sov. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 1989;28(8):613–617. doi: 10.1007/BF00794576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuhara M., Mitani H. Mechanisms of grain growth in Ti(C,N)–Ni sintered alloys. Powder Metall. 2013;25(2):62–68. doi: 10.1179/pom.1982.25.2.62. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.M., R. Suri P., Park S.J. Review: liquid phase sintering. J. Mater. Sci. 2009;44(1):1–39. doi: 10.1007/s10853-008-3008-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng L., et al. Densification and mechanical properties of TiC by SPS-effects of holding time, sintering temperature and pressure condition. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2012;32(12):3399–3406. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2012.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Growth of Carbide Particles in TiC–Ni and TiC–Mo2C–Ni Cermets during Liquid Phase Sintering. 1991. pp. 951–956. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loh N.J., et al. Effect of temperature and holding time on the densification of alumina obtained by two-step sintering. Ceram. Int. 2017;43(11):8269–8275. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.03.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Z., et al. The formation mechanism of TiC/Ni composites fabricated by pressureless reactive sintering. Int. J. Refract. Metals Hard Mater. 2021;97 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2021.105524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang L.J., et al. Oxidation behavior of in situ TiCp/Ti6Al4V composite with self-assembled network microstructure fabricated by reaction hot pressing. Corrosion Sci. 2013;69:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2012.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi Q., et al. Effect of TiC particles size on the oxidation resistance of TiC/hastelloy composites applied for intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cell interconnects. J. Alloys Compd. 2019;778:811–817. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.11.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meredith B., Milner D.R. The liquid–phase sintering of titanium carbide. Powder Metall. 2013;19(3):162–170. doi: 10.1179/pom.1976.19.3.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang C., Lee D., Kim D. Oxidation behaviour of an Alloy 617 in very high-temperature air and helium environments. Int. J. Pres. Ves. Pip. 2008;85(6):368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpvp.2007.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chu C.L., S.K.W. Yen Y.C. Oxidation behavior of equit atomic TiNi alloy in high temperature in air environment. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1996;A216:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0921-5093(96)10409-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Z., et al. Oxidation Mechanism of In-Situ TiC/Ni Composites at 1073 K. Corrosion Scie. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Y., Peng X., Wang F. Size effect of Al particles on the oxidation of electrodeposited Ni–Al composite coatings. Oxid. Metals. 2005;64(3):169–183. doi: 10.1007/s11085-005-6557-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.