Abstract

The crude Solanum tuberdsm polysaccharides (STP) were extracted with hot water. In the process of extraction, proteins, pigments, small molecules and salts in the mixture were removed by Sevage reagent, diatomite and distilled water dialysis, respectively. In addition, the process conditions of protein removal by response surface methodology (RSM) were optimized, and the optimum process conditions of Sevage method were established as follows: ultrasound power 350 W, ultrasound time 20 min, deproteinization twice, volume ratio of polysaccharide solution to Sevage reagent 1:1 (mL/mL). Under these conditions, the protein removal rate was 93.14%.

Keywords: Ultrasonic-assisted extraction, Analysis, Polysaccharide from Solanum tuberdsm

1. Introduction

Polysaccharides have important biological activities, such as antioxidant activity, antitumor activity, immunomodulatory activity and so on [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Chemical modification of polysaccharide is beneficial to study the relationship between its structure and activity, and provides experimental and theoretical basis for its application [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. However, efficient preparation of a certain amount of polysaccharides is an important prerequisite for the above work [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27].

The efficiency of extraction, separation and purification of polysaccharides will be affected by many factors. When there are multiple independent variables that affect the response factors, an optimization method that can determine all the factors is often used. In addition, in order to determine the best experimental scheme, the possibility of interaction between independent variables should be considered [28], [29], [30], [31]. Response surface methodology (RSM) is an effective tool to optimize the independent variables of the process to have a common influence, that is, the expected response. RSM is considered as a statistical and mathematical method suitable for problem modeling and evaluation, in which meaningful responses are affected by different independent (or input) parameters. RSM promotes the intelligent design of experiments, in which the required data can be determined in the minimum number of iterations, thereby saving time, space and raw materials, and has been successfully used to develop, improve and optimize these processes [32].

In recent years, it has been found that Solanum tuberdsm is rich in nutrients, which has attracted people's attention, but there are few reports on the efficient preparation of Solanum tuberdsm polysaccharides (STP). Herein, STP were obtained by ultrasonic-assisted extraction, then deproteinized by Sevage reagent, decolorized by diatomite and dialyzed with distilled water in turn to obtain crude STP. Meanwhile, the deproteinization process was optimized by RSM.

2. Experimental part

2.1. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of crude polysaccharide from Solanum tuberdsm

Fresh Solanum tuberdsm was peeled, cleaned, sliced, dried and ground into powder. Then 50 g dried Solanum tuberdsm powder was condensed and refluxed and degreased with 300 mL anhydrous ethanol (1:6, W/V) for 2 h each time. After centrifugation, the clear liquid was discarded, and then 1000 mL distilled water (1:20, W/V) was added to the defatted Solanum tuberdsm powder and extracted twice (2 h/time) at 80 ℃ under ultrasonic-assisted condition. After centrifugation, the collected supernatant was decompressed and concentrated to 1/10 (about 200 mL) of the original volume. Four times the volume of anhydrous ethanol was added to the concentrate, placed at 4 ℃, and precipitated overnight. Then, the precipitate was washed with ethanol and acetone for 2 ∼ 3 times and then freeze-dried, and then the dried product was re-dissolved with a small amount of distilled water, deproteinized twice with Sevage reagent (polysaccharide solution: Sevage reagent = 2:1), then 2% diatomite powder was added to the polysaccharide solution for decolorization treatment, stirring for 30 min and centrifugation to remove diatomite, the operation was repeated twice. The supernatant after centrifugation was put into a 3500 Da dialysis bag and dialyzed with distilled water for 72 h. After freeze-drying, the crude STP were obtained. It was worth noting that RSM was used to optimize the conditions of the deproteinization process [33].

2.2. Determination of total sugar, protein and uronic acid content

The contents of total sugar, protein and uronic acid in Solanum tuberdsm polysaccharides were determined by phenol–sulfuric acid method [34], Coomassie brilliant blue method [35] and sulfuric acid-carbazole method [36] respectively. Firstly, the standard curves of glucose, protein and uronic acid were made with standard glucose (Glc), bovine serum albumin (BSA) and galacturonic acid (GalUA) as control, and then the contents of total sugar, protein and uronic acid were calculated according to the linear regression equation of the standard curve.

2.3. Single factor experimental design

The single factor experiment of Sevage deproteinization was designed by the way of controlling variables, that is, the three main factors affecting the protein removal rate (oscillation time (A, min), protein removal times (B, times), polysaccharide solution-Sevage reagent volume ratio (C, mL/mL) were designed, and their effects on protein removal rate and polysaccharide loss rate were investigated respectively. Except for the single variable experimental factors, the other experimental factors remained unchanged. After pre-experimental analysis, factor A was designed as 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 min;, factor B was designed as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 times, and factor C was designed as 1:2, 1:1, 1.5, 2:1, 2.5 respectively.

2.4. Experimental design of RSM

On the basis of single factor experiment, a response surface analysis experiment with 3 factors (A, B, C) 3 levels (- 1, 0, 1) was designed by using Design Expert software (Table 1). Then the three factors and protein removal rate were used as independent variables and response values, namely Box-Behnken central combinatorial experimental design (BBD).

Table 1.

The BBD factor and level of deproteinization by Sevage method.

| Level | Factor |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| A (min) | B (time) | C (mL/mL) | |

| −1 | 15 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 0 | 20 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 25 | 3 | 1.5 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Analysis of the results of single factor test of deproteinization by Sevage method

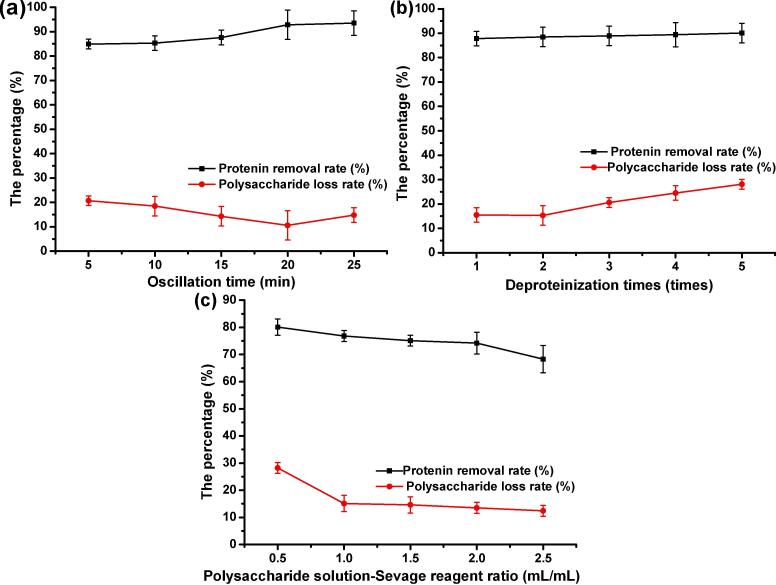

The effects of oscillation time (A, min), deproteinization times (B, times) and volume ratio of polysaccharide solution to Sevage reagent (C, mL/mL) on protein removal rate and polysaccharide loss rate are shown in Fig. 1. It can be seen from Fig. 1 (a) and (b) that the protein removal rate increases with the increase of oscillation time and deproteinization times, but considering that Sevage reagent may destroy the structure of polysaccharides, resulting in partial loss of polysaccharides [37]. When the oscillation time is 20 min and the number of protein removal is 2 times, the protein removal effect is almost the best, and the protein removal rate is 92.8% and 88.5% respectively, and the polysaccharide loss under this condition is the lowest. Similarly, the effect of the volume ratio of polysaccharide solution to Sevage reagent on the protein removal rate and polysaccharide loss rate is analyzed (Fig. 1 (c)). It is not difficult to analyze that when the volume ratio of polysaccharide solution to Sevage reagent is 1: 1, the protein removal rate is higher and the polysaccharide loss rate is lower. Therefore, according to the comprehensive analysis, the shaking time of 20 min, the number of protein removal twice and the volume ratio of polysaccharide solution to Sevage reagent at 1:1 were taken as the best conditions for the single factor experiment, and the single factor test results were used to design the response surface analysis experiment (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

The effects of shaking time (a), times of protein removal (b) and volume ratio of polysaccharide solution to Sevage reagent (c) on protein removal rate and polysaccharide loss rate.

3.2. BBD and experimental results

On the basis of the previous single-factor experiments, according to the principle of BBD experiment, taking A, B, C as 3 factors and-1, 0, 1 as 3 levels, a total of 17 groups of response surface analysis experiments were designed by Design Expert software. The scheme and results were shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Box-Behnken center combination experiment design and results.

| No | Factor |

Protein removal rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (min) | B (time) | C (mL/mL) | ||

| 1 | 0.000 | −1.000 | −1.000 | 72.35 |

| 2 | 0.000 | 1.000 | −1.000 | 83.48 |

| 3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 92.35 |

| 4 | −1.000 | 0.000 | −1.000 | 72.26 |

| 5 | −1.000 | −1.000 | 0.000 | 72.21 |

| 6 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 72.88 |

| 7 | −1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 83.83 |

| 8 | 0.000 | −1.000 | 1.000 | 83.25 |

| 9 | 1.000 | −1.000 | 0.000 | 83.14 |

| 10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 93.33 |

| 11 | 1.000 | 0.000 | −1.000 | 83.62 |

| 12 | −1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 83.73 |

| 13 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 93.32 |

| 14 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 93.34 |

| 15 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 71.93 |

| 16 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 71.32 |

| 17 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 93.35 |

3.3. Establishment of regression model and significance analysis

The regression analysis of BBD results was carried out by Design Expert software, and the protein removal rate was taken as the response value (Y). The regression model equation was established as follows:

| Y=+4.53–3.320 × 103A + 7.401 × 104B + 1.596 × 104C-0.076AB-0.074AC-0.069BC-0.093A2-0.092B2-0.088C2 |

The significance of the regression model was further analyzed, and the analysis of variance was shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Analysis of variance of regression model.

| Item | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F value | p value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.18 | 9 | 0.020 | 939.55 | <0.0001 | ** |

| A | 8.817 × 10-5 | 1 | 8.817 × 10-5 | 4.11 | 0.0832 | – |

| B | 4.382 × 10-6 | 1 | 4.382 × 10-6 | 0.20 | 0.6650 | – |

| C | 2.039 × 10-7 | 1 | 2.039 × 10-7 | 9.503 × 10-3 | 0.9251 | – |

| AB | 0.023 | 1 | 0.023 | 1066.67 | <0.0001 | ** |

| AC | 0.022 | 1 | 0.022 | 1034.16 | <0.0001 | ** |

| BC | 0.019 | 1 | 0.019 | 888.41 | <0.0001 | ** |

| A2 | 0.023 | 1 | 0.037 | 1711.78 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B2 | 0.035 | 1 | 0.035 | 1648.76 | <0.0001 | ** |

| C2 | 0.033 | 1 | 0.033 | 1527.23 | <0.0001 | ** |

| Residual error | 1.502 × 10-4 | 7 | 2.416 × 10-5 | |||

| Misfit term | 6.008 × 10-5 | 3 | 2.003 × 10-5 | 0.89 | 0.5193 | – |

| Pure error | 9.011 × 10-5 | 4 | 2.253 × 10-5 | |||

| Total error | 0.18 | 16 |

* *: The difference is extremely significant (p < 0.0001); *: The difference is significant (0.0001 < p < 0.05); -: The difference is not significant (p > 0.05).

It can be seen from Table 3 that the p value of the model is less than 0.0001 and the larger F value (939.55) indicates that the regression model is extremely significant, while the misfit p (0.5193) > 0.05 and the smaller F value (0.89) indicates that the difference is not significant.

The above results show that the fitting degree between the regression equation model and the experimental data is good, and the experimental error is small. Secondly, the lower coefficient of variation C.V. (0.11%) shows that the experimental value has high accuracy and reliability [38].

In addition, the determination coefficient R2 (0.9992) and the adjustment determination coefficient R2Adj (0.9981) are very close to 1, suggesting that the correlation between the experimental value and the predicted value is very high. The results also showed that the quadratic terms of oscillation time (A), protein removal times (B) and polysaccharide solution-Sevage reagent volume ratio (C) all reached a very significant level, and the interaction between any of them was also extremely significant.

3.4. Response surface optimization analysis

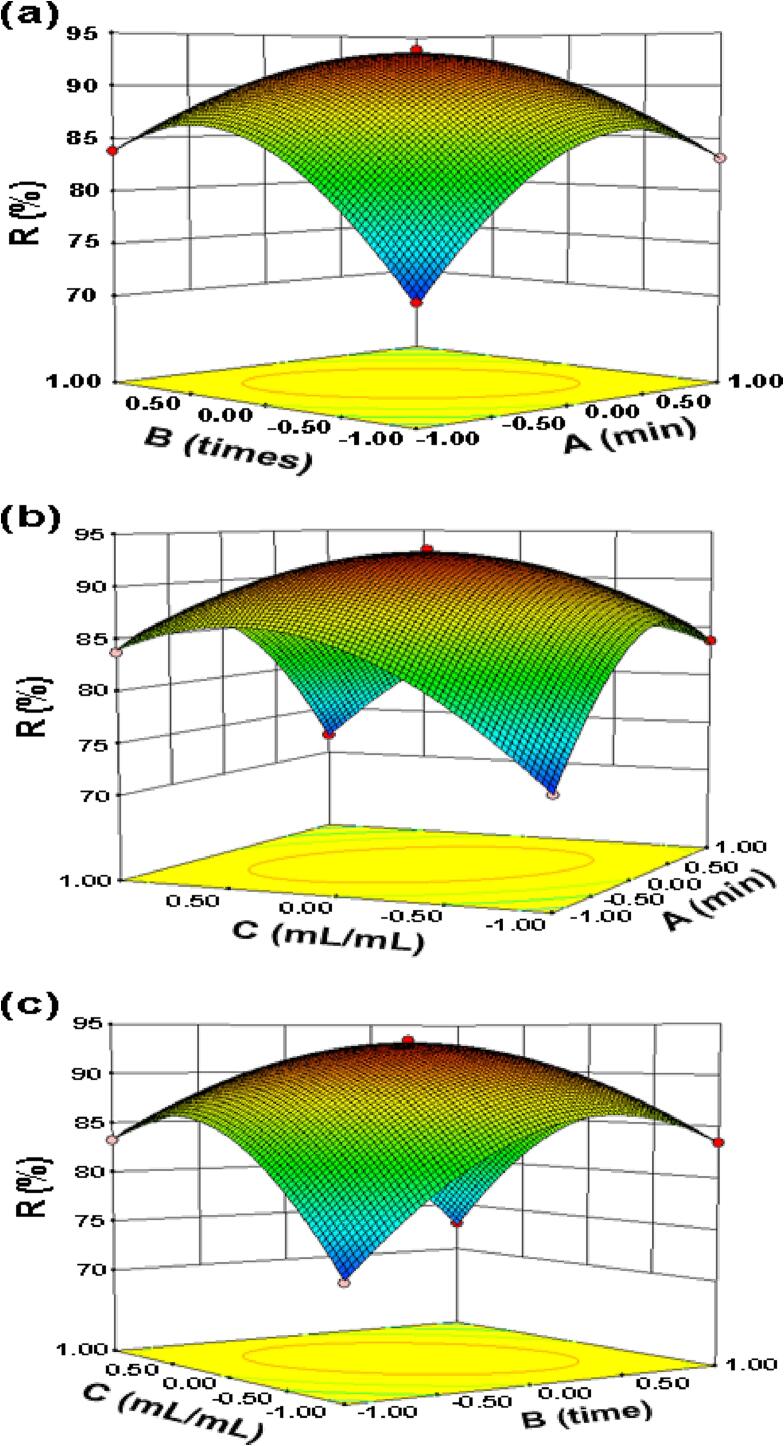

According to the experimental results of BBD, the 3D response surface map and 2D response surface contour map are drawn by Design-Expert software, as shown in Fig. 2. In the 3D response surface diagram, the significance of the response value to its experimental factors can be judged according to the slope of the surface [39]. In the 2D response surface contour map, the shape of the contour can reflect the interaction between the two factors, the closer the shape is, the stronger the interaction is, and the experimental results of all the experimental schemes on the same contour are the same. In addition, the speed of color change (from blue to red) of 2D contour map can also reflect the significance of the response value to its experimental factors. Therefore, compared with the 2D contour map, it can more directly reflect the influence of various factors on the response value. It is not difficult to see from Fig. 2 that the three experimental factors analyzed have a common trend, that is, with the strengthening of the conditions, the protein removal rate will increase at first and then decrease, and there is a maximum protein removal rate. Secondly, the contours of the three 2D response surfaces are oval, suggesting that any two of the three factors affecting the protein removal rate have a very significant effect on the protein removal rate, which is consistent with the results of the previous regression model analysis of variance. By further analyzing the slope of the 3D response surface and the color change of the 2D contour map, and combining with the results of the previous regression model analysis of variance, it is not difficult to find that the significant order of the influence of the three experimental factors on the protein removal rate is as follows: oscillation time > times of protein removal > volume ratio of polysaccharide solution-Sevage reagent. This suggests that we should focus on the oscillation time of the mixed solution in the process of deproteinization of Solanum tuberdsm polysaccharides.

Fig. 2.

The pairwise interaction effects under ultrasonic-assisted condition of oscillation time (A), times of protein removal (B) and volume ratio of polysaccharide solution to Sevage reagent (C) on protein removal rate.

3.5. Proper inspection of the model

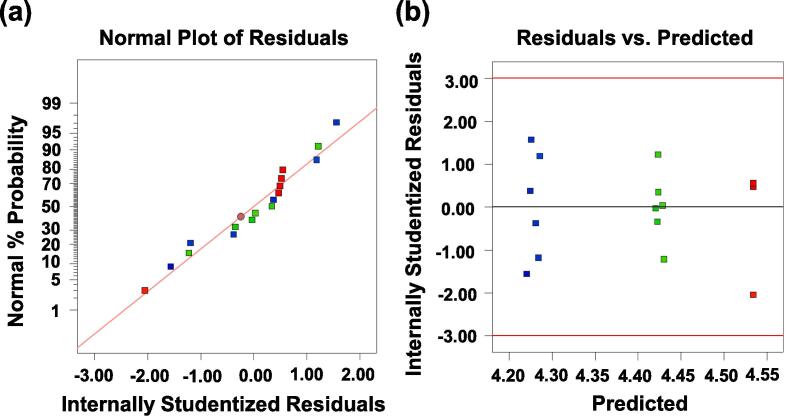

If the fitting degree of the model is not high enough and the response surface optimization experiment continues, it may lead to poor experimental results or misleading results [40]. In order to ensure the approximation between the fitted model and the real system, it is generally necessary to check the model properly, and the residual of least square fitting plays an important role in judging the adequacy of the model [41]. Therefore, our first task is to test the normal hypothesis, and the strategy given in this paper is to construct the normal probability graph of the residual as shown in Fig. 3 (a). It is obvious that the residual curve is approximately along a straight line, indicating that the residual result satisfies the normality hypothesis. Our next step is to map the relationship between the residual and the predicted response (Fig. 3 (b)). Surprisingly, the residual is randomly distributed on the diagram, which shows that the original variance is constant for all Y values [42]. Based on the above analysis, it shows that the experimental model has a high degree of fit and can be used to describe the protein removal rate of Solanum tuberdsm polysaccharides by response surface methodology.

Fig. 3.

The normal probability of internal research residual (a) and the relationship between internal research residual and predicted response (b).

3.6. Model prediction and verification of optimal process conditions

Based on the regression model analysis of the Sevage deproteinization process of Solanum tuberdsm polysaccharides, the Design Expert software was used to predict the best process of Sevage deproteinization. The predicted results showed that the theoretical value of protein removal rate (93.14%) reached the maximum when the oscillation time was 19.857 min, the times of protein removal was 2.01 times, and the volume ratio of polysaccharide solution to Sevage reagent was 1:1 (mL/mL). Considering the feasibility of practical operation, we adjusted the process parameters to 20 min, deproteinization twice, polysaccharide solution-Sevage reagent volume ratio 1:1, and carried out three parallel verification experiments under these conditions. The average result of the three experiments was 92.28%, which was only 0.86% different from the predicted results. Based on the analysis of the above results, it can be seen that the experimental results are in good agreement with the prediction results of the model, which shows that the regression equation model (formula 1) is accurate and effective. Therefore, the Sevage deproteinization process of Solanum tuberdsm polysaccharides optimized by RSM has good reliability and practicability.

4. Conclusion

Using fresh Solanum tuberdsm as the initial material, the dried Solanum tuberdsm powder was obtained after a series of pretreatment. Then crude STP were prepared under ultrasonic-assisted condition from dried Solanum tuberdsm powder by refluxing and degreasing with ethanol, water extraction and alcohol precipitation, protein removal with Sevage reagent, decolorization of diatomite, dialysis and freeze-drying. On the basis of single factor experiment, RSM was used to optimize the process conditions of protein removal. The optimum process conditions of Sevage method were as follows: shaking time 20 min, deproteinization 2 times, volume ratio of polysaccharide solution to Sevage reagent 1:1 (mL/mL). Under this condition, the protein removal rate was 93.14%. Through the model prediction and verification of the best process conditions, in fact, the difference between the measured results and the predicted results was only 0.86%. The verification results showed that there was no significant difference between the experimental value and the predicted value, indicating that the response model could fully reflect the expected optimization.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wenjian Yang: Wrote the manuscript. Gangliang Huang: Reviewed & edited the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Song Z., Xiong X., Huang G. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and characteristics of maize polysaccharides from different sites. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;95:106416. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong X., Yang W., Huang G., Huang H. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction, characteristics and activity of Ipomoea batatas polysaccharide. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;96:106420. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y., Xiong X., Huang G. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and analysis of maidenhairtree polysaccharides. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;95:106395. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou S., Huang G. Extraction, structure characterization and biological activity of polysaccharide from coconut peel. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023;10(1):15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou S., Huang G. Extraction, structural analysis and antioxidant activity of aloe polysaccharide. J. Mol. Struct. 2023;1273:134379. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang W., Duan W., Huang G., Huang H. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction, analysis and properties of mung bean peel polysaccharide. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;98:106487. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang Z., Wang Y., Huang G., Huang H. Ultrasound-assisted extraction, analysis and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from the rinds of Garcinia mangostana L. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;97:106474. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y., Huang G. Extraction and derivatisation of active polysaccharides. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019;34(1):1690–1696. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2019.1660654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan Y., Huang G. Preparation, structural analysis and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides and their derivatives from Pueraria lobata. Chem. Biodivers. 2023;20:e202201253. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.202201253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mei X., Tang Q., Huang G., Long R., Huang H. Preparation, structural analysis and antioxidant activities of phosphorylated (1→3)-β-D-glucan. Food Chem. 2020;309 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen F., Huang G., Huang H. Preparation, analysis, antioxidant activities in vivo of phosphorylated polysaccharide from Momordica charantia. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;252:117179. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang W., Huang G. Chemical modification and structural analysis of polysaccharide from Solanum tuberdsm. J. Mol. Struct. 2023;1285:135480. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W., Huang G. Preparation, structural characteristics, and application of taro polysaccharides in food. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022;102(14):6193–6201. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J., Fan Y., Huang G., Huang H. Extraction, structural characteristics and activities of Zizylphus vulgaris polysaccharides. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022;178:114675. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin B., Huang G. An important polysaccharide from fermentum. Food Chemistry: X. 2022;15:100388. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang Z., Huang G. Extraction, structure, and activity of polysaccharide from Radix astragali. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022;150:113015. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin B., Huang G. Extraction, isolation, purification, derivatization, bioactivity, structure-activity relationship, and application of polysaccharides from White jellyfungus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022;119(6):1359–1379. doi: 10.1002/bit.28064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou S., Huang G., Huang H. Extraction, derivatization and antioxidant activities of onion polysaccharide. Food Chem. 2022;388:133000. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang W., Huang G. Extraction methods and activities of natural glucans. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;112:50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang G., Chen F., Yang W., Huang H. Preparation, deproteinization and comparison of bioactive polysaccharides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;109:564–568. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang W., Huang G., Chen F., Huang H. Extraction/synthesis and biological activities of selenopolysaccharide. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;109:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benchamas G., Huang G., Huang S., Huang H. Preparation and biological activities of chitosan oligosaccharides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;107:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang Q., Huang G. Improving method, properties and application of polysaccharide as emulsifier. Food Chem. 2022;376:131937. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li B., Huang G. Preparation, structure-function relationship and application of Grifola umbellate polysaccharides. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022;186:115282. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu B., Lin B., Huang G. Preparation of acetylated grapefruit peel polysaccharide. Chem. Biodivers. 2023:e202300167. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.202300167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan Y., Huang G. Preparation and analysis of Pueraria lobata polysaccharides. ACS Biomater Sci. Eng. 2023;9(5):2329–2334. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c01479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin B., Wang S., Zhou A., Hu Q., Huang G. Ultrasound-assisted enzyme extraction and properties of Shatian pomelo peel polysaccharide. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;98:106507. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui W., Mazza G., Oomah B.D., Biliaderis C.G. Optimization of an aqueous extraction process for flaxseed gum by response surface methodology. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 1994;27(4):363–369. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koocheki A., Mortazavi S.A., Shahidi F., et al. Optimization of mucilage extraction from Qodumeshirazi seed (Alyssum homolocarpum) using response surface methodology. J. Food Process Eng. 2010;33(5):861–882. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y., Cui S.W., Tang J., Gu X. Optimization of extraction process of crude polysaccharides from boat-fruited sterculia seeds by response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2007;105(4):1599–1605. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye C.L., Jiang C.J. Optimization of extraction process of crude polysaccharides fromPlantagoasiaticaL. by response surface methodology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011;84(1):495–502. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin Y.J., Jia J.R., Wang T., et al. Optimization of natural anthocyanin efficient extracting from Solanum tuberdsm for silk fabric dyeing. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;149:673–679. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin Y.Q., Li Y., Kong L.Y. Pentasaccharide glycosides from the tubers of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56(7):2363–2368. doi: 10.1021/jf0733463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xianqing Y., Mingqiu L., Bo Q.i., et al. Comparative study on determination methods of polysaccharides in asparagus.Food Industry. Sci. Technol. 2013;34(22):54–57. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zor T., Selinger Z. Linearization of the Bradford protein assay increases its sensitivity: theoretical and experimental studies. Anal. Biochem. 1996;236(2):302–308. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hongli Z., Shijuan L., Dan C. Determination of uronic acid in corn whisker polysaccharide. Food Industry. 2014;35(10):262,264. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yue C., Zhenkang S., Haiyue Z. Optimization of protein removal from Solanumnigrum polysaccharides by trichloroacetic acid. Food and fermentation Industry. 2020;46(24):198,203. [Google Scholar]

- 38.He Yinju, Yang Zaibo, PengXinmei, et al. Study on optimization of extraction technology and antioxidant activity of passionflower polysaccharides by response surface method. Food Res. Dev., 2020, 41 (4): 38-44.

- 39.Yang Hua, ZhuangChenfeng. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of asparagus polysaccharides by response surface method and its antioxidant activity. Food Sci., 2011, 32 (20): 79-83.

- 40.Li W., Cui S.W., Kakuda Y. Extraction, fractionation, structural and physical characterization of wheat β-D-glucans. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006;63(3):408–416. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen W.A. Response surface methodology: process and product optimization using designed experiments. J. Qual. Technol. 2017;49(2):186–187. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samavati V. Polysaccharide extraction from Abelmoschus esculentus: Optimization by response surface methodology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;95(1):588–597. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]