Abstract

Primary production underpins most ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration and fisheries. Artificial reefs (ARs) are widely used for fisheries management. Research has shown that a mechanism by which ARs in seagrass beds can support fisheries and carbon sequestration is through increasing primary production via fertilization from aggregating fish excretion. Seagrass beds are heavily affected by anthropogenic nutrient input and fishing that reduces nutrient input by consumers. The effect of these stressors is difficult to predict because impacts of simultaneous stressors are typically non-additive. We used a long-term experiment to identify the mechanisms by which simultaneous impacts of sewage enrichment and fishing alter seagrass production around ARs across non-orthogonal gradients in human-dominated and relatively unimpacted regions in Haiti and The Bahamas. Merging trait-based measures of seagrass and seagrass ecosystem processes, we found that ARs consistently enhanced per capita seagrass production and maintained ecosystem-scale production despite drastic shifts in controls on production from human stressors. Importantly, we also show that coupled human stressors on seagrass production around ARs were additive, contrasting expectations. These findings are encouraging for conservation because they indicate that seagrass ecosystems are highly resistant to coupled human stressors and that ARs promote ecosystem services even in human-dominated ecosystems.

Keywords: carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, production, fish, excretion

1. Introduction

Humans are altering the movement of nutrients within and among ecosystems with important consequences for the controls on primary production. This is a significant conservation issue given that primary production underpins important ecosystem services by (i) fixing carbon (C) from the atmosphere, which can lead to C sequestration and (ii) directly and indirectly supporting resources that can be harvested for human consumption, e.g. seaweed and fisheries. Among the most conspicuous stressors to primary producers are the large influxes of nutrients into ecosystems via municipal, industrial and agricultural waste products [1]—whereby the availability of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) has increased by approximately 100% and approximately 400% globally [2]. Less conspicuous is the alteration of consumer nutrient supply through exploitation and habitat degradation that change consumer communities, e.g. altered size structure and community composition [3,4]. These two stressors are ubiquitous and rarely occur in isolation, and it is well established that simultaneous stressors can interact in unpredictable ways [5]. Improving conservation and management strategies to better mitigate the effects of nutrient pollution and exploitation requires these stressors to be studied in conjunction under real-world conditions.

The concomitant alteration of consumer communities and nutrient enrichment is more pronounced in coastal marine ecosystems than possibly any other ecosystem type [6]. Anthropogenic fertilizer and waste inputs have vastly increased the availability of nutrients in nearly all coastal ecosystems [7]. Fishing pressure has drastically reduced consumer biomass, with critical implications for supply of nutrients to marine ecosystems [4,8,9]. For example, fishing has reduced fish nutrient supply to some coral reefs and mangrove ecosystems in the Caribbean by 40% [4] and 80% [10], respectively. Such changes to nutrient dynamics can be particularly pronounced in oligotrophic tropical coastal ecosystems. Experiments on independent effects of consumers [11] and anthropogenic nutrients [12] have been shown to alter the controls on primary production. Yet, if and how these simultaneous stressors interact to alter the controls of primary production remains poorly understood and is expected to be complex.

Understanding how anthropogenic stressors alter primary production requires (i) baseline knowledge of what factors control production in unimpacted conditions and (ii) sufficient a priori understanding of the ecosystem to generate hypotheses regarding how anthropogenic stressors could change these controls. Primary production in unimpacted tropical coastal ecosystems is often P limited [13]. In these systems, fish excretion is typically high in N relative to P [11,14], whereas anthropogenic nutrient inputs tend to be dominated by municipal sources, e.g. sewage, which is typically high in P relative to N [15]. A hypothesis from first principles would thus be that the loss of fish, and addition of anthropogenic nutrient supply should reduce P limitation, leading to additional factors that could otherwise control primary production, i.e. light, N, or C.

Artificial reefs (ARs) provide an ideal experimental unit to test this hypothesis under real-world conditions. ARs can promote high densities of fishes and are widely used for fisheries restoration in hard-bottom habitats [16–18]. When constructed in tropical seagrass beds, they have been shown to create biogeochemical hotspots (BGHs) via nutrient supply from aggregating fish [11,19–22]. The concentrated fish-mediated nutrient supply initiates nonlinear responses in seagrass production that have been identified as the key mechanism leading to ecosystem-level increases in primary production [23]. The implications of this are significant for the sequestration of C because seagrass beds are among the most important blue carbon ecosystem types globally [24]. It also has important implications for fisheries as the AR-associated BGHs promote increased invertebrate prey resources for fishes [25] and ultimately may fuel increased fish production via bottom-up [26] and top-down mechanisms [16]. Yet, the extent of the primary producer response is dependent on (i) the amount of fish-derived nutrients provided, and thus fishing pressure, and (ii) the level of anthropogenic nutrient enrichment in the surrounding seagrass bed.

In an experiment using ARs in a tropical seagrass bed in The Bahamas, simulated fishing pressure and nutrient pollution together shifted nutrient limitation of seagrass growth from P to N [19]. An additional finding was that the effects of the simulated stressors were largely additive—and thus had relatively predictable outcomes based on knowledge of the independent effects. In temperate seagrass beds, research has shown that increased nutrients leads to light limitation of seagrass production due to reduced water clarity from increased phytoplankton production [27]. Yet, an important limitation of the study by Allgeier et al. [19] was that because nutrient pollution was simulated only around the ARs (and not at the ecosystem scale), additional expected repercussions of eutrophication such as decreased light availability from water column algal growth could not be tested. Studying production around ARs along real-world gradients of anthropogenic stressors will provide more realistic tests of the implications of simultaneous stressors for the controls on primary production.

In this study, we used ARs to experimentally test how anthropogenic stressors in human-dominated and relatively unimpacted tropical coastal ecosystems alter the controls on primary production. We constructed ARs across non-orthogonal environmental gradients of fishing pressure and anthropogenic nutrient pollution in The Bahamas and Haiti. Our goal is not to determine per se which factor, fishing pressure or nutrient enrichment, has the strongest effect on production around ARs, but instead to understand how they alter the controls on seagrass production and how this affects the potential of ARs to promote seagrass production. Specifically, we asked three questions:

-

(1)

How do fish and anthropogenic nutrients influence seagrass production around ARs?

-

(2)

How are seagrass traits and seagrass ecosystem processes around ARs affected in human-dominated systems compared to less impacted systems?

-

(3)

How do the controls that underpin seagrass production around ARs change across a gradient of human impact?

We hypothesized that (i) anthropogenic nutrients would have an opposing non-additive effect with fish nutrient supply on primary production near the ARs, (ii) the spatial extent, effect size and absolute number of seagrass traits affected by the presence of the ARs would be reduced in human-dominated systems and (iii) the number of controls on seagrass production would increase with greater nutrient enrichment.

2. Methods

(a) . Study site

This study took place in two locations on Abaco island, The Bahamas: the Bight of Old Robinson (N 26 20.392 W 077 00.496), and Man-O-War Cay (N 26 36.372 W 077 01.176) and on the island of Ile A Vache, Haiti (IAV; N 18.12020 W 073.67102). Six and seven ARs (approx. 1 m wide × 2 m long × 1 m tall) were constructed in The Bahamas and Haiti, respectively (figure 1), in 2014 from 88 cinder blocks and glued together using Zspar Marine Epoxy. The ARs were deployed at similar depths of approximately 3.5–4 m in medium density (641.6 ± 156.4 shoots m−2) seagrass habitats dominated by turtle grass, Thalassia testudinum. The Bahamas and Haiti offer useful gradients of fishing pressure and anthropogenic nutrient pollution (figures 2 and 3). These gradients are non-orthogonal—fishing pressure can exist where anthropogenic nutrients are low, but high anthropogenic nutrients are also often associated with high fishing pressure. Our a priori expectations were (i) all ARs in Haiti would have low fish nutrient supply because of high fishing pressure relative to The Bahamas (J.E.A. and C.L., personal observations), (ii) ARs in Haiti would experience high levels of nutrient input from anthropogenic sewage, with some locations experiencing more than others depending on the proximity to human communities (H5, H8 are very close to the largest communities on IAV; figure 1 [22]) and (iii) ARs in The Bahamas would range from no (LH1–3) to low anthropogenic input (MOW1–3; all near a small human settlement).

Figure 1.

Map of research locations in (a) Abaco, The Bahamas—inset colours identify locations of (b) Man-O-War Cay (purple) and (c) Bight of Old Robinson (maroon). Map of research locations in (d) Haiti—inset colours identify locations of (e) Ile A Vache. AR in (f) Bight of Old Robinson and (g) Ile A Vache. Pink dots identify locations of ARs on (b) (MOW1–3), (c) (LH1–3) and (e) (H1–H8). White dot in (e) identifies AR that was destroyed (H7).

Figure 2.

Comparison among ARs and The Bahamas and Haiti. Histograms of fish total length in (a) The Bahamas (purple) and (b) Haiti (green)—each line indicates a given AR, filled distributions are for all ARs in each region. (c) Nitrogen (N) and (d) phosphorus (P) supply by fish communities on all ARs. Seagrass nutrients for (e) N and (f) P. In all cases, colours correspond to (a) and (b) for region. ‘**’ or ‘n.s.’ denote statistically significant differences (α = 0.05), or lack thereof, respectively, between regions. Sites within each island were ranked based on %P in ambient seagrass (Amb. SG) tissue (increasing darkness = increasing %P). Total phosphorus = TP; total nitrogen = TN.

Figure 3.

Comparison among ARs in The Bahamas (purple) and Haiti (green). Island-level means at 1 and 20 m are indicated by black and red dashed bars, respectively. ‘**’ or ‘n.s.’ denote statistical significance (α = 0.05), or lack thereof, respectively, between islands. Black and red values indicate differences at 1 m and 20 m, respectively. The darkness of the symbol indicates ARs in areas of greater human impacts for each respective region, based on %P in ambient seagrass. See electronic supplementary material, figure S3, for additional reef-level variables. SLA = specific leaf area; LAI = leaf area index.

(b) . Field sampling

Samples and measurements were taken in May and June 2018 at the AR level and plot level. AR-level measurements consisted of (i) sediment cores to quantify nutrient content and sediment characteristics, (ii) fish surveys to quantify fish biomass and nutrient supply and (iii) water nutrients. Plot-level measurements consisted of T. testudinum variables (e.g. growth rates and tissue nutrients) and were taken in a spatially explicit manner around each AR using three transects oriented approximately 120° apart. Each transect had eight distances (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12 and 20 m from the AR), yielding 24 sampling ‘plots’ per AR (3 transects × 8 distances; each plot was approximately 0.25 m2 centred at each distance). Measurements taken at 20 m were expected to be beyond the extent of the BGH based on previous research [19–21] and were used as a proxy variable representing the relative ambient nutrient conditions of each site [22,28]. ARs in figures are ranked by ambient seagrass %P as a visual representation of approximate anthropogenic impact. Both systems in The Bahamas and Haiti are strongly P limited, and previous studies show that using seagrass nutrient content is a useful proxy for anthropogenic impacts in these systems [10,22]. See electronic supplementary material for detailed descriptions of specific field and laboratory methods including methods used to estimate fish nutrient supply.

(c) . Statistical analyses

Two response variables were used, reflecting attributes of primary production at different scales: (i) T. testudinum Shoot Growth (mm2 day−1) and (ii) aboveground C Production (g C m−2 day−1 = shoot growth (g day−1) × tissue %C × shoot density m−2)—a per capita growth measure and an ecosystem-level measure, respectively. Five plant traits were used as representative proxies for factors that limit primary production [29]: (i) %N—N limitation, (ii) %P—P limitation, (iii) δ13C in seagrass tissue (dry weight)—C limitation, (iv) specific leaf area (SLA; shoot area (mm2)/shoot mass (mg))—combined nutrient and light limitation [30] and (v) leaf area index (LAI; shoot area (m2) × shoot density (m−2)) [31]—light limitation (figure 3). T-tests (α < 0.05) were used to test if these variables differed at the AR (1 m) and at the control locations 20 m from the BGH (figure 2). Three fish community variables were used to represent nutrient supply from the fish community (averaged across years for each AR): excretion of N and P (g m−2 day−1) based on a survey area of 16 m2 around and including the AR and their ratio N : P (molar; figure 2). Three sediment variables: %N and %P of dry weight and their N : P ratio were used as an additional representation of the local nutrient availability.

(i) . Question 1: How do fish and anthropogenic nutrients influence seagrass production around artificial reefs?

To test this question, we ran the following mixed-effect model:

| 2.1 |

where ‘RESP’ is either seagrass Shoot Growth (mm2 day−1) or aboveground C Production (g m−2 day−1), ‘DIST’ is the different distances at which each seagrass variable was measured (0.5–12 m), ‘CNS’ is consumer-mediated nutrient supply at the AR level (g N or P m−2 day−1, or N : P ratio) and ‘AMB’ is ambient nutrient enrichment expressed as a continuous measure of seagrass nutrient content (%P, %N or N : P molar) 20 m from the AR. ‘AR’ nested in ‘Island’ was specified as a random effect. The model was run three ways following Allgeier et al. [19] whereby all terms in each model were specified for either N, P or N : P to test which of the three best predicted the two response variables. Model parameters were logged to meet model assumptions of normality and heteroscedasticity. Predictors were standardized (values subtracted by the mean, divided by s.d.) to reduce multicollinearity caused by the interaction term and the variance inflation factors to less than 2, and allow direct comparison between predictors. Standardized regression coefficients and marginal and conditional R2 values for each component model were used to compare differences among models. The best-fit model was evaluated using AICc [32].

(ii) . Question 2: How are seagrass traits and seagrass ecosystem processes around artificial reefs affected in human-dominated systems compared to less impacted systems?

We addressed this question as a four-step process. (1) To understand which seagrass variables demonstrated a significant nonlinear response with distance from each AR (0.5 to 12 m) we ran generalized additive models (GAMs; mgcv package in R [33]) on the relationship between seven seagrass variables (Shoot Growth, C Production, Seagrass %N, Seagrass %P, Seagrass δ13C, SLA and LAI) and distance from AR (response–distance)—neither response nor predictor variables were transformed. We ran a separate model for each individual AR to test for: (i) statistical significance (α < 0.05) and (ii) if the GAM was better than a linear model using AIC, following Allgeier et al. [19] (see details in electronic supplementary material, table S1 and figure S1). (2) When a significant nonlinear curve was determined, we quantified the spatial extent to which seagrass response variables were affected by the AR. We performed a posterior simulation from the fitted GAM (using the mgcv package in R [33]) to predict 100 sets of response values at each distance, i.e. 100 values from 0.5 to 12 m. We used these values to generate 100 simulated response–distance curves. We performed a changepoint analysis on each curve (using the three-phase segmented model ‘M111’ from the R package chngpt [34]) to determine the distance that defined the spatial extent to which each variable of interest was affected around the AR following Layman et al. [20].

(3) For each AR, we quantified the effect size for each trait for which a threshold was identified. This effect size was estimated as the slope by which the trait changed from a distance of 0 (at the AR) to the threshold (estimated in step 2 above). To do this we ran a linear model on the predicted values from the GAM data using only data from the intercept to the threshold.

(4) We tested if ‘Island’ predicted the size or magnitude of the AR effects on seagrass. To do this, we performed t-tests to compare the mean thresholds and slopes of the two variables with the most identified thresholds (Shoot Growth, Seagrass %P and Seagrass δ13C—see Results). Linear models were run to test if the spatial extent (thresholds) and the effect sizes (slopes) of traits were correlated to environmental variables: fish nutrient supply (N, P, N : P), ambient nutrients (%N, %P, N : P molar of seagrass at 20 m) and sediment nutrients (%N, %P, N : P molar of dry weight).

(iii) . Question 3: How do the controls that underpin seagrass production around artificial reefs change across a gradient of human impact?

For this analysis, we ran separate structural equation models (SEMs) (using the piecewiseSEM package in R [35]) in four primary environmental conditions captured by our study. Specifically, we constructed ‘AR Models’ for each island using data from distances 1, 2, 3 m (n = 61, 54 datapoints for Haiti and The Bahamas, respectively) based on the threshold analysis indicating that the mean spatial extent of the seagrass effects was approximately 3 m from the AR. We also constructed ‘Ambient Models’ for each island using data from distances 4, 6, 12 and 20 m (n = 71, 79 data points for Haiti and The Bahamas, respectively). For each model, we tested hypothesized causal relationships, referred to as ‘pathways’, between seagrass nutrient content (%N and %P), δ13C, SLA, LAI, Shoot Growth and C Production. Each hypothesized SEM consisted of four component models (see full hypothesized model in electronic supplementary material, figure S2):

-

(1)

SLA ∼ Seagrass %N + Seagrass %P

-

(2)

LAI ∼ Seagrass %N + Seagrass %P

-

(3)

Shoot Growth ∼ %N + Seagrass %P + Seagrass δ13C + SLA

-

(4)

C Production ∼ Seagrass %N + Seagrass %P + Seagrass δ13C + LAI + SLA

From the hypothesized models, we iterated through a stepwise process to find the best-fit model following [36]: (i) the hypothesized SEM was run; (ii) non-significant relationships in each component model were iteratively removed until only significant relationships were remaining; and (iii) the goodness-of-fit (Fisher's C statistic) and AICc were used to assess the fit of the global SEM [35,37]. Model validity of each component model was assessed by plotting residuals against fitted values and assuring the variance inflation factor was less than 2. A mixed-effect structure was used to account for the nested design of our data by including random effects for ‘Distance’ nested within ‘AR’. We imputed 17 data points of a total of 268 data points in order to run complete datasets in the piecewiseSEM package [35] (imputation methods are explained in detail in the electronic supplementary material). Variables (except for Seagrass δ13C and SLA) were log or square root transformed to meet model assumptions of normality and heteroscedasticity. ‘Direct effects’ were quantified as the standardized model coefficients for each response variable. ‘Indirect effects’ were quantified as the product of these direct effects along the pathways in the SEM. ‘Total effects’ were calculated as the sum of all the direct and indirect effects of a predictor on a response variable. Standardized regression coefficients for each relationship and marginal and conditional R2 values for each component model were used to compare differences among models.

A second analysis tested the extent to which per capita seagrass production (Shoot Growth) influenced ecosystem-level seagrass production (C Production) in conditions that were relatively unimpacted by humans, and those that ranged from moderate to heavily impacted. The following mixed-effects model was used in two ways, one for unimpacted ARs (3 ARs; LH1–3, n = 72 all distances) and one for impacted ARs (10 ARs; MOW1–3 and all ARs in Haiti, n = 236 all distances):

| 2.2 |

where PRED represents one of the variables of interest: Seagrass %N, Seagrass %P, Seagrass δ13C, Epiphytes, Herbivory. We were interested in (i) if the slope of Shoot Growth changed in impacted relative to unimpacted ARs, (ii) the extent to which the model explained variation in the data, e.g. the R2, and (iii) if additional variables improved model fit.

3. Results

The Bahamas and Haiti are both carbonate seagrass systems, characterized by a high inorganic C content in the sediment (mean ± s.d., 11.83 ± 0.11% and 11.53 ± 0.6%, respectively). We found slightly higher organic C and total N content in the sediments in Haiti than in The Bahamas (electronic supplementary material, table S2) likely stemming from increased sedimentation from land-use practices—the island of IAV has steep grades with heavy agricultural use [38]. Similarly, water column nitrate was higher in Haiti (almost three times), and the more enriched sediment δ15N signature in Haiti indicates sedimentation with a higher proportion of 15N rich matter, such as human waste [39] (electronic supplementary material, table S2). In contrast with expectations, the water column in The Bahamas was significantly higher in total P than in Haiti. Total water column N did not differ between islands.

Fish communities on ARs in The Bahamas were more variable and on average fish were larger (total length) than those found in Haiti (figure 2). ARs in Haiti tended to have numerically more and smaller fish (rarely more than 20 cm long). There was greater variation in fish biomass and excretion rates (N and P) on ARs in Haiti with greater maximum biomass than in The Bahamas (electronic supplementary material, figures S2 and S3).

Seagrass shoots grew significantly faster but were sparser at both 1 m (at the BGH) and 20 m (i.e. not affected by the BGH) from the ARs in Haiti than in The Bahamas (figure 3). Aboveground C production, LAI and seagrass tissue %N did not differ between islands at either of the distances. There was, however, a significant difference of SLA, seagrass tissue %P, shoot density, seagrass tissue δ13C and epiphytes biomass at the 20 m distance between islands. Epiphyte DW : shoot DW across all sampling plots ranged between 0 and 1.6, with a mean (±s.d.) of 0.25 (±0.18) and corresponds well with previous studies on T. testudinum [40,41]. Seagrass leaf herbivory was slightly stronger in Haiti and significantly differed at ambient levels. Herbivory on seagrass in our study system tended to be largely from: small parrotfish which were quantified from bite marks on the seagrass blades; invertebrates that feed largely on the epiphytes on the seagrass; and turtles that are present in The Bahamas, but were never observed in Haiti (J.E.A. and C.L., personal observations).

(a) . Question 1: How do fish and anthropogenic nutrients influence seagrass production around artificial reefs?

A number of positive effects of ARs on seagrass production were identified by significant negative relationships between the two response measures of seagrass production (Shoot Growth and C Production) and distance from the AR (table 1). Fish nutrient supply enhanced the AR effect (negative interaction term with distance), and anthropogenic P reduced the AR effect (positive interaction term with distance). N : P ratio had the opposite effect, in that the higher N : P ratio of fish nutrients reduced the AR (positive interaction term with distance) while higher N : P ratio of anthropogenic nutrients enhanced it (negative interaction term with distance). The effects of fish excretion and ambient nutrients were additive, that is, anthropogenic inputs additively reduced the positive effect of fish-mediated nutrients around the AR (i.e. no three-way interaction term with distance).

Table 1.

Standardized coefficients of predictors of seagrass Shoot Growth and C Production to the BGHs around ARs. The null model has log(Distance) as the predictor variable. Additional predictors were added to the null model: phosphorus (P) content, nitrogen (N) content and N : P ratio of consumer-mediated nutrient supply (CNS) and ambient nutrients (AMB, seagrass tissue 20 m from the ARs). Model marginal R2, conditional R2 and AICc are reported. Colon (:) indicates an interaction between the variables on either side of the colon, and a colon before a term symbolizes an interaction with the term log(DIST). Significant (p ≤ 0.05) terms in italics.

| intercept | log(DIST) | :CNS | :AMB | :CNS:AMB | AICc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| shoot growth | ||||||||

| null | 4.38 | −0.21 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.06 | 0.87 | 300.6 |

| P | 4.41 | −0.25 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.87 | 245.4 |

| N | 4.42 | −0.26 | −0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.88 | 254.5 |

| N : P | 4.41 | −0.26 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.86 | 257.0 |

| C production | ||||||||

| null | −1.01 | −0.12 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.02 | 0.67 | 335.7 |

| P | −0.96 | −0.15 | −0.10 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.67 | 269.4 |

| N | −0.95 | −0.16 | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.69 | 279.2 |

| N : P | −0.96 | −0.16 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.68 | 278.7 |

All models explained substantial variation in the data (approx. 0.87 for Shoot Growth and approx 0.67 for C Production) but, this variation was primarily explained by the nested random effects of AR within island suggesting that greater variation in the data could be explained by differences among islands and among ARs within islands. For both Shoot Growth and C Production, the P models were favoured according to the AICc and explained the most variation in the data. The N : P ratio model explained slightly more variation than the N model for both response variables.

(b) . Question 2: How are seagrass traits and seagrass ecosystem processes around artificial reefs affected in human-dominated systems compared to less impacted systems?

We found numerically more variables were affected by the AR in less impacted sites of The Bahamas, than in Haiti. This was demonstrated by a significant nonlinear relationship between a response variable and distance from the AR (figure 4a). Across all traits and processes we found that 60% of the relationships with distance from ARs in The Bahamas were nonlinear, in contrast with 30% in Haiti (figure 4b; electronic supplementary material, figure S4). Shoot Growth and Seagrass %P were the two response variables that had numerically the most significant nonlinear relationships across ARs. The only two ARs (H5 and H8) for which Seagrass %P did not have a nonlinear relationship were in Haiti and both were heavily influenced by human sewage (e.g. sediment variables; H5, H8, figure 2).

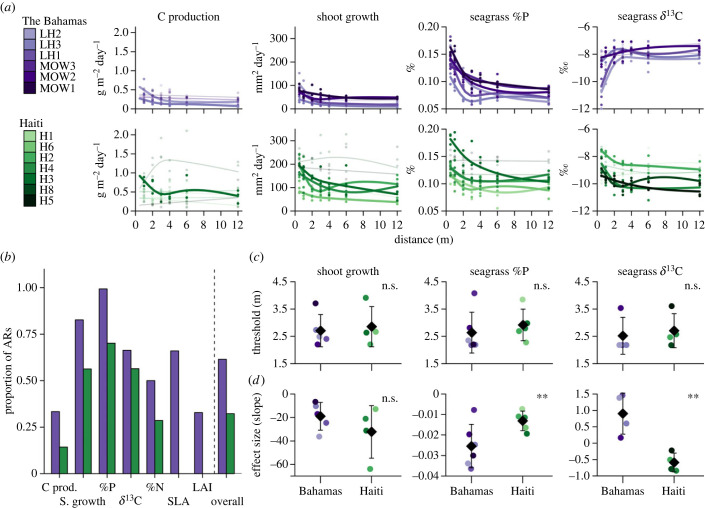

Figure 4.

(a) Functional responses of seagrass traits and processes with respect to distance in Haiti (green) and The Bahamas (purple). Each line represents an individual AR corresponding to datapoints of the same colour. (b) Proportion of ARs that showed a significant nonlinear relationship with distance for each trait/process and collectively (overall). (c) Mean thresholds by which ARs within each region affect specific traits and processes. SLA = specific leaf area; LAI = leaf area index. (d) Effect size (slope of line between intercept and threshold) for traits and processes. ‘n.s.’ and ‘*’ indicate not significant and significant (α = 0.05), respectively. Comparisons were only made for trait/processes with sufficient significant effect—see electronic supplementary material, figure S4, for results from the remaining seagrass traits.

The spatial extent to which ARs affect seagrass traits was on average between 2 and 3 m as determined by threshold analyses run on significant GAMs (figure 4c). Interestingly, mean threshold values for Seagrass Growth, Seagrass %P and Seagrass δ13C, the parameters of which we could compare the thresholds (greater than 2 thresholds per island), did not differ between islands. The effect size of ARs on Seagrass %P was greater (more negative) in The Bahamas than Haiti (figure 4d)—no differences between islands were found for Shoot Growth (figure 4d). The response of Seagrass δ13C was contrasting between the two islands, with δ13C increasing with increasing distance in The Bahamas, but decreasing with distance in Haiti.

The spatial extent (threshold) and effect size by which ARs affected Seagrass %P were positively related to Sediment %N (electronic supplementary material, table S3) and Sediment %P (electronic supplementary material, table S3). The effect size by which ARs affected Seagrass δ13C was negatively related to Ambient Seagrass %P and Sediment %P and positively related to Ambient Seagrass N : P. We found no effects of consumer-mediated nutrients nor ambient nutrients on Shoot Growth thresholds or slopes.

(c) . Question 3: How do the controls that underpin seagrass production around artificial reefs change across a gradient of human impact?

Four SEMs were used to test two hypotheses: (i) there are fewer overall pathways in The Bahamas due to strong P limitation of seagrass production [11] and (ii) there are more controls on production (increased number of pathways) with increasing enrichment from fish and humans indicating a shift away from strong nutrient limitation to other controls on production.

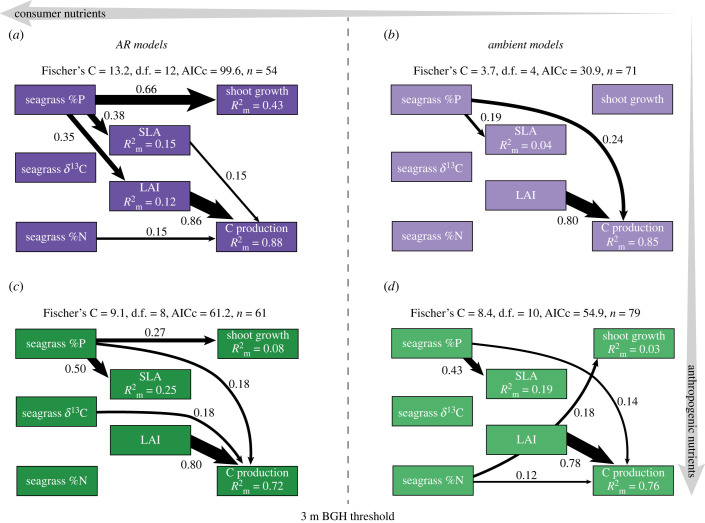

Consistent with our first hypothesis, the ambient seagrass production model (Ambient Model) in The Bahamas had the fewest significant pathways of all models (two total) (figure 5). These pathways included a strong relationship between LAI and C Production, and a weaker relationship between Seagrass %P and C Production indicating light and P, respectively, were important controls on seagrass production. In contrast with the first hypothesis, the AR Model in The Bahamas had more pathways than the AR Model in Haiti suggesting more potential indirect and direct controls on production around the ARs in The Bahamas.

Figure 5.

Significant pathways linking the response variables and predictors in separate SEMs. Models are separated into the BGH (AR models (a,c)) and outside of the BGH (ambient models (b,d)) in The Bahamas (purple) and Haiti (green). Number associated with each arrow and arrow size indicate relative effect size.

Consistent with the second hypothesis, there were four more significant pathways in the AR Model than the Ambient Model in The Bahamas. In the AR Model in The Bahamas, there was an indication of controls on production other than P. Specifically, Seagrass %P was strongly (total effect size = 0.36) but indirectly related to C production via LAI and SLA, and Seagrass %N significantly (but weakly) affected C Production. Seagrass %P was also strongly related to Shoot Growth indicating that per capita seagrass production around the AR was more controlled by P availability than in ambient conditions (figure 5).

Comparing the Ambient Model for Haiti to The Bahamas provides support for both hypotheses. First, the number of pathways increased with enrichment (more in the Haiti Ambient Model). Second, the Haiti Ambient Model demonstrated a shift away from strong P limitation in two ways: (i) the strength of the relationship between Seagrass %P and C Production was reduced in the Haiti Ambient Model and (ii) Seagrass %N was now positively related to both Shoot Growth and C Production in Haiti.

In contrast with our hypothesis, the number of significant pathways did not change from the Haiti Ambient Model to the AR Model. Additionally, the AR Model in Haiti, which has more anthropogenic nutrients than in The Bahamas, had fewer pathways than the AR Model in The Bahamas. However, we did see additional shifts in controls on Seagrass Growth and C Production with increased enrichment whereby in the most enriched model—the Haiti AR Model—C Production and Shoot Growth were controlled by Seagrass %P and Seagrass δ13C, indicating colimitation of P and C.

Across all models, LAI was by far the strongest predictor of C Production (figure 5). This highlights the importance of light interception for seagrass production across multiple environmental settings. Interestingly, comparing the conditional relative to marginal R2 indicates that more of the variation in Shoot Growth and C Production was explained by variation among ARs in Haiti than in The Bahamas, while most of the variation in SLA was explained by variation among ARs in The Bahamas (electronic supplementary material, table S4).

Directly testing the relationship between C Production and Seagrass Growth revealed three primary things. First, as expected there was a strong relationship between these variables, and the strength of this relationship was relatively stable across all ARs (standardized effect size: 0.75 and 0.73 in unimpacted and impacted ARs, respectively; electronic supplementary material, table S5). Second, there was more variation in this relationship among the impacted ARs than the unimpacted ARs as indicated by (i) the lack of a significant intercept in impacted models and (ii) the high conditional and low marginal R2 in impacted models. Third, no variable explained additional meaningful variation in this relationship on either impacted or unimpacted AR, highlighting that no single factor controlled ecosystem-level production across ARs.

4. Discussion

A strength of our study is that we took advantage of a widely applied restoration tool, ARs, as an experimental unit to achieve two overarching goals: (i) to understand how common, simultaneous anthropogenic stressors are affecting the functioning of seagrass ecosystems and (ii) to quantify the capacity of ARs to increase primary production, and thus better inform how they can promote ecosystem services in the face of these stressors. ARs are commonly used for fisheries restoration in coastal ecosystems [16–18,26] mostly associated with hard-bottom habitats (coral reefs and coastal shelfs). In tropical seagrass systems, ARs promote substantial increases in primary production at the local [11] and ecosystem scales [23] that can increase energy input to the ecosystem and thus may simultaneously enhance fisheries and C sequestration. Our study showed that even in highly impaired ecosystems ARs consistently promoted increased seagrass production, highlighting their potential as an effective restoration tool. Yet, no single factor controlled seagrass production across study sites. Instead, our study highlights the context-dependent way in which local stressors affect seagrass ecosystems, and that the underlying mechanisms can be cryptic. Thus, an additionally important outcome of our work is to underscore the need for system-specific knowledge to direct appropriate management for effective outcomes. Our findings are largely optimistic for the conservation of seagrass ecosystems because they show seagrass can maintain high rates of production in the face of even extreme stressors.

ARs consistently promoted increased seagrass production by releasing seagrass from nutrient limitation to the degree that under the highest level of enrichment seagrass production became C limited. We hypothesized that anthropogenic sewage input should reduce the effect of ARs on seagrass production, and that fishing pressure should be non-additive and further dampen this effect because of reduced fish-mediated nutrients around the AR. Surprisingly, we did not find any non-additive effects of fishing and anthropogenic nutrient enrichment on seagrass production [5]. Instead, we found that where fishing was highest (in IAV, Haiti) fish communities on ARs were high in biomass, at times higher than in relatively unfished locations in The Bahamas—leading to greater fish-mediated nutrient supply which was highly unexpected. We do not have data on fishing pressure around IAV, but the small mean fish body size and near absolute lack of predators on patch reefs around IAV and in the fish markets (J.E.A. and C.L., personal observations) are highly indicative of strong fishing pressure. Two possible factors could explain the unexpectedly high observed fish biomass on ARs in Haiti: (i) fishes on ARs in Haiti are generally difficult for fishers to catch with the large seine nets commonly used (J.E.A. and C.L., personal observations) and (ii) low predation due to the paucity of larger predatory fishes (barracuda, jacks and sharks; J.E.A. and C.L., personal observations). The emergent effect was that the high excretion rates of these communities functionally (and additively) counteracted the extent to which anthropogenic enrichment reduced the difference in production at the AR relative to the open seagrass beds (AMB term, table 1).

Production in seagrass beds is fundamentally governed by the availability of light, nutrients and in some systems herbivory [27,42,43]. In tropical seagrass ecosystems there are fewer large herbivores (e.g. dugongs and turtles) and high levels of omnivory, no widespread evidence of trophic cascades as in temperate systems (e.g. [43]), and previous research suggests the role of herbivory to be subsidiary to the primary effects of light and nutrients [22]. In this study, the only significant effect we found with respect to herbivory was a weak but positive effect on primary production around ARs in Haiti—possibly due to excretion from the high density of grazers that increased primary production (electronic supplementary material, figure S5). By contrast, we found strong support for the importance of light and nutrients (see below). Specifically, LAI—a measure of the ability of seagrass to intercept light—was the strongest predictor of C Production, an ecosystem-level measure of production (figure 4). Although seagrass shoot density per area was used to calculate LAI and C Production, neither of these attributes differed substantially across ARs, whereas shoot density did (figure 3). This indicates some level of ‘self-thinning’, whereby seagrass reduce shoot density to compensate for reduced light availability that occurs when nutrient enrichment increases blade size [44]. In temperate systems, epiphytes can also reduce light availability [45], but in our study, they had relatively weak and inconsistent effects on seagrass production. Including epiphyte biomass in the SEMs used for Question 3 showed that they had weak negative effects on Shoot Growth and C Production in open seagrass beds in Haiti (Ambient Model) and a weak indicating some support for potential light limitation. Yet, we also found a positive effect of epiphyte biomass on Shoot Growth in The Bahamas around the ARs (AR Model) (electronic supplementary material, figure S6) where epiphyte biomass levels were similar (see Haiti 20 m and Bahamas 1 m in figure 3). Taken as a whole, our findings, largely driven by the strong positive relationship between C Production and LAI found across all conditions (figure 5), provide substantial evidence that anthropogenic enrichment did not have profound effects on light limitation as is common in more temperate regions [42]—in fact the highest growth rates in this study were found in the two most impacted sites (H5 and H8) and represent the upper limit of previously estimated growth rates [46]. Instead, we identified the availability of key nutrients as a leading control on primary production in these systems.

Understanding which, and to what extent, seagrass traits changed as a function of distance from the AR enabled us to test the hypotheses that: (i) ambient seagrass production is primarily controlled by P limitation and (ii) seagrass production will shift controls to other factors with increases in nutrient enrichment. Seagrass C Production was relatively uniform across all ARs, but ambient seagrass per capita growth was roughly twice as fast in Haiti (figure 3). Despite this, the spatial distance by which nutrients provided by fishes affected seagrass traits around ARs, i.e. the threshold, was similar in both islands. However, the number of traits that indicated this spatial effect was substantially greater in The Bahamas than Haiti (figure 4). Of these traits, Seagrass %P was significant on more ARs than any other—notably being significant on fewer ARs in Haiti than The Bahamas. This supports strong P limitation of seagrass production in these ecosystems, and that this limitation is reduced in Haiti because of high levels of anthropogenic (P-rich) nutrient loading. Interestingly, we found that ARs in systems that are more affected by anthropogenic nutrients (as indicated by increased Sediment %N and %P; figure 4; electronic supplementary material, table S3) actually had a greater spatial effect on seagrasses around the AR, that is, the threshold at which they affected the surrounding seagrass was greater. By contrast, ARs in systems that are more affected by anthropogenic nutrients also tended to have smaller effect sizes, i.e. the difference in a trait between ambient seagrass and seagrass around the AR was smaller. What is particularly noteworthy is that despite these clear differences in traits across ARs, seagrass C Production was relatively constant across all conditions demonstrating production was maintained across a gradient of controlling factors.

Our SEM analysis identified potential mechanisms by which seagrass was able to maintain high production rates under differing conditions. Specifically, three findings supported our primary hypotheses. First, open seagrass in The Bahamas (the Ambient Model) showed the fewest pathways, indicating that C Production was strongly controlled by only a few factors as predicted, i.e. light and P (LAI and Seagrass %P, respectively). Second, the number of controls on seagrass production increased with fish nutrient input around the ARs in The Bahamas (AR Model relative to the Ambient Model) and showed that in addition to light and P, N (Seagrass %N) was also limiting C Production. Shifts between P and N limitation in T. testudinum are naturally widespread in this region [47], and in addition to P-rich fish excretion, respiration of the high sediment organic matter in Haiti (electronic supplementary material, table S2) can cause phosphorus dissolution, releasing phosphate for uptake [28]. Third, N limitation of seagrass production increased in open seagrass in Haiti where there are high levels of anthropogenic nutrients with presumably low N : P due to the relatively high amount of P in human sewage.

Seagrass production around the ARs in Haiti (AR Model) somewhat deviated from expectations, but still followed first principle expectations when considered in light of system-specific details. C Production around the ARs in Haiti relative to the ambient conditions in Haiti (Ambient Model) showed a shift from N limitation to colimitation by P and C, and per capita Shoot Growth shifted to exclusive P limitation. This result can be explained by the unexpectedly high loading rates of fish excretion around ARs in Haiti that is high in N relative to P in combination with high levels of nutrients from fishes and anthropogenic sources. Elevated primary production and thus demand for C, and high epiphyte biomass (figure 3) can induce C limitation in seagrass [48]. In this case, an increase in the heavy 13C isotope may indicate: (i) a shift in the source of inorganic C by seagrass—from a lighter 13C (e.g. CO2) to a heavier source (e.g. [49]), (ii) reallocation of C from rhizomes to leaves [46,50] or (iii) less discrimination against the 13C isotope [51]. The oscillation between limiting factors across model scenarios represents a novel component of our study and supports a proposed mechanism for nutrient colimitation of primary production [52].

One of the more unexpected findings from our study was that C Production, an ecosystem-level measure of production, was relatively uniform across ARs and open seagrass but Shoot Growth, a per capita measure of production, responded to the presence of ARs in highly variable ways. Yet, despite this, Shoot Growth was strongly and positively related (standardized effect size greater than 0.7) with C Production across all ARs. C Production is the product of Shoot Growth, shoot density and Seagrass %C, so this outcome is intuitive. Nonetheless, this relationship is informative because it shows that C Production was being maintained despite being regulated by different controls. For example, Shoot Growth explains more of the variation in C Production around ARs in environments with very little human impact than those that are impacted (marginal R2 = 0.89 versus 0.48, respectively; electronic supplementary material, table S5). However, no additional covariate explained the residual variation in the data in either model. This indicates that no single factor was responsible for variation in C Production across ARs, and instead AR-specific factors are likely more important (further supported by the fact that the AR random intercept in the C Production ∼ Shoot Growth model explained approximately 40% of the variation in the data on impacted ARs; electronic supplementary material, table S5). These findings support our SEMs, in that seagrass experience a range of limiting conditions while maintaining production. This is relevant for conservation because our findings show that ARs are providing surplus primary production that may be promoting C sequestration and could fuel higher trophic levels, even in highly impacted ecosystems.

Our study underscores both the challenges and the utility of conducting large studies that employ in situ gradients of human stressors as a central component of the experimental design. A key challenge is the need to rely on environmental variables as proxies for the human stressors. Our use of Seagrass %P 20 m from the AR has been previously used to document relative anthropogenic input in these systems (see also [22,28]) and we found substantial differences between the two islands that supported our expectations. By contrast, our proxy of fishing pressure (fish nutrient supply) only marginally reflected the true fishing pressure across our sites. Despite these challenges, we exploited real-world gradients in our experimental design and found that seagrass are exceptionally resistant to human perturbations and can adapt to a range of limiting and surplus conditions while maintaining production. Collectively, our findings provide a very clear message for the conservation of tropical seagrass ecosystems: predicting outcomes for seagrass production is feasible when taking into consideration (i) multiple potential controls for production [53] and (ii) system-specific dynamics. The unexpected nature of some of our findings underscores the importance of conducting research under real-world conditions to understand often cryptic consequences of global change on ecosystem processes if we are to effectively manage ecosystem services.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the residents of Ile A Vache, Haiti for allowing us to conduct this research in their local waters. This project would not have been accomplished without the direct support of local fishers who provided valuable insight with their knowledge of the local seascape, physical labour and boat use, and community leaders who helped engender support for the project. Mecì ampil. Specifically, we would like to thank Vital Jean Felix, Pierre Ulsned, Calise Bossla, Capitan, Damien Meany, and Alish O'Reilly. We would like to thank the country of The Bahamas for granting us access to conduct research in their amazing waters. We would also like to thank Matt McCoy for his critical logistical assistance and his love for bwafe, and Katrina Munsterman for field support and her love for Ostned. We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers and the editors for their valuable comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mona A. Andskog, Email: andskog.mona@gmail.com.

Jacob E. Allgeier, Email: jeallg@umich.edu.

Data accessibility

All data and code used in the analysis are online at Data Dryad: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.37pvmcvqn [54].

Additional information is provided in the electronic supplementary material [55].

Authors' contributions

M.A.A.: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; C.L.: conceptualization and funding acquisition; J.E.A.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

Funding was provided by a David and Lucille Packard Fellowship and National Science Foundation OCE grant no. 1948622 to J.E.A. and National Science Foundation OCE grant no. 0746164 to C.L.

References

- 1.Peñuelas J, Sardans J. 2022. The global nitrogen-phosphorus imbalance. Science 375, 266-267. ( 10.1126/science.abl4827) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elser JJ, et al. 2007. Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1135-1142. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01113.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntyre PB, Jones LE, Flecker AS, Vanni MJ. 2007. Fish extinctions alter nutrient recycling in tropical freshwaters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 4461-4466. ( 10.1073/pnas.0608148104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allgeier JE, Valdivia A, Cox C, Layman CA. 2016. Fishing down nutrients on coral reefs. Nat. Commun. 7, 12461. ( 10.1038/ncomms12461) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darling ES, Cote IM. 2008. Quantifying the evidence for ecological synergies. Ecol. Lett. 11, 1278-1286. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01243.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lotze HK, et al. 2006. Depletion, degradation, and recovery potential of estuaries and coastal seas. Science 312, 1806-1809. ( 10.1126/science.1128035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz RJ, Rosenberg R. 2008. Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science 321, 926-929. ( 10.1126/science.1156401) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maranger R, Caraco N, Duhamel J, Amyot M. 2008. Nitrogen transfer from sea to land via commercial fisheries. Nat. Geosci. 1, 111-113. ( 10.1038/ngeo108) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianchi D, Carozza DA, Galbraith ED, Guiet J, DeVries T. 2022. Estimating global biomass and biogeochemical cycling of marine fish with and without fishing. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd7554. ( 10.1126/sciadv.abd7554) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Layman CA, Allgeier JE, Rosemond AD, Dahlgren CP, Yeager LA. 2011. Marine fisheries declines viewed upside down: human impacts on consumer-driven nutrient recycling. Ecol. Appl. 21, 343-349. ( 10.1890/10-1339.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allgeier JE, Yeager LA, Layman CA. 2013. Consumers regulate nutrient limitation regimes and primary production in seagrass ecosystems. Ecology 94, 521-529. ( 10.1890/12-1122.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armitage AR, Frankovich TA, Fourqurean JW. 2011. Long-term effects of adding nutrients to an oligotrophic coastal environment. Ecosystems 14, 430-444. ( 10.1007/s10021-011-9421-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Short FT. 1987. Effects of sediment nutrients on seagrasses: literature review and mesocosm experiment. Aquat. Bot. 27, 41-57. ( 10.1016/0304-3770(87)90085-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allgeier JE, Layman CA, Mumby PJ, Rosemond AD. 2014. Consistent nutrient storage and supply mediated by diverse fish communities in coral reef ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 2459-2472. ( 10.1111/gcb.12566) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterner RW, Elser JJ. 2002. Ecological stoichiometry: the biology of elements from molecules to the biosphere, p. 429. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr MH, Hixon MA. 1997. Artificial reefs: the importance of comparisons with natural reefs. Fisheries 22, 28-33. () [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seaman W. 2007. Artificial habitats and the restoration of degraded marine ecosystems and fisheries. Hydrobiologia 580, 143-155. ( 10.1007/s10750-006-0457-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paxton AB, Shertzer KW, Bacheler NM, Kellison GT, Riley KL, Taylor JC. 2020. Meta-analysis reveals artificial reefs can be effective tools for fish community enhancement but are not one-size-fits-all. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 282. ( 10.3389/fmars.2020.00282) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allgeier JE, Layman CA, Montaña CG, Hensel E, Appaldo R, Rosemond AD. 2018. Anthropogenic versus fish-derived nutrient effects on seagrass community structure and function. Ecology 99, 1792-1801. ( 10.1002/ecy.2388) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Layman CA, Allgeier JE, Yeager LA, Stoner EW. 2013. Thresholds of ecosystem response to nutrient enrichment from fish aggregations. Ecology 94, 530-536. ( 10.1890/12-0705.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Layman CA, Allgeier JE, Montaña CG. 2016. Mechanistic evidence of enhanced production on artificial reefs: a case study in a Bahamian seagrass ecosystem. Ecol. Eng. 95, 574-579. ( 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.06.109) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brines EM, Andskog MA, Munsterman KS, Layman CA, McCoy M, Allgeier JE. 2022. Anthropogenic nutrients mitigate importance of fish-mediated nutrient supply for seagrass beds in Haiti. Mar. Biol. 169, 38. ( 10.1007/s00227-022-04020-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esquivel KE, Hesselbarth MHK, Allgeier JE. 2022. Mechanistic support for increased primary production around artificial reefs. Ecol. Appl. 32, e2617. ( 10.1002/eap.2617) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mcleod E, Chmura GL, Bouillon S, Salm R, Björk M, Duarte CM, Lovelock CE, Schlesinger WH, Silliman BR. 2011. A blueprint for blue carbon: toward an improved understanding of the role of vegetated coastal habitats in sequestering CO2. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 552-560. ( 10.1890/110004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeager LA, Acevedo CL, Layman CA. 2012. Effects of seagrass context on abudance, condition and secondary production of a coral reef fish, Haemulon plumierii. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 462, 231-240. ( 10.3354/meps09855) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Layman CA, Allgeier JE. 2020. An ecosystem ecology perspective on artificial reef production. J. Appl. Ecol. 57, 2139-2148. ( 10.1111/1365-2664.13748) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waycott M, et al. 2009. Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12 377-12 381. ( 10.1073/pnas.0905620106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen HS, McGlathery KJ, Marino R, Howarth RW. 1998. Forms and availability of sediment phosphorus in carbonate sand of Bermuda seagrass beds. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 799-810. ( 10.4319/lo.1998.43.5.0799) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Funk JL, et al. 2017. Revisiting the Holy Grail: using plant functional traits to understand ecological processes. Biol. Rev. Camb. Phil. Soc. 92, 1156-1173. ( 10.1111/brv.12275) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westoby M. 1998. A leaf-height-seed (LHS) plant ecology strategy scheme. Plant Soil 199, 213-227. ( 10.1023/A:1004327224729) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dierssen H, Zimmerman R, Drake L, Burdige D. 2010. Benthic ecology from space: optics and net primary production in seagrass and benthic algae across the Great Bahama Bank. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 411, 1-15. ( 10.3354/meps08665) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. 2002. Model selection and multimodel inference a practical information-theoretic approach. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood SN. 2017. Generalized additive models: an introduction with R, 2nd edn. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fong Y, Huang Y, Gilbert PB, Permar SR. 2017. chngpt: threshold regression model estimation and inference. BMC Bioinform. 18, 454. ( 10.1186/s12859-017-1863-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lefcheck JS. 2016. piecewiseSEM: piecewise structural equation modelling in R for ecology, evolution, and systematics. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 573-579. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.12512) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allgeier JE, Andskog MA, Hensel E, Appaldo R, Layman C, Kemp DW. 2020. Rewiring coral: anthropogenic nutrients shift diverse coral–symbiont nutrient and carbon interactions toward symbiotic algal dominance. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 5588-5601. ( 10.1111/gcb.15230) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grace JB, Schoolmaster DR, Guntenspergen GR, Little AM, Mitchell BR, Miller KM, Schweiger EW. 2012. Guidelines for a graph-theoretic implementation of structural equation modeling. Ecosphere 3, 44. ( 10.1890/ES12-00048.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Etienne A, Wesdyk K. 2021. Development constraints & opportunities: Île-à-Vache, Haiti. Framingham, MA: EDEM Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kendall C, Elliott EM, Wankel SD. 2007. Tracing anthropogenic inputs of nitrogen to ecosystems. In Stable isotopes in ecology and environmental science (eds Michener R, Lajtha K), pp. 375-449. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lapointe BE, Barile PJ, Matzie WR. 2004. Anthropogenic nutrient enrichment of seagrass and coral reef communities in the Lower Florida Keys: discrimination of local versus regional nitrogen sources. Ecology 308, 23-58. ( 10.1016/j.jembe.2004.01.019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heck KL, Pennock JR, Valentine JF, Coen LD, Sklenar SA. 2000. Effects of nutrient enrichment and small predator density on seagrass ecosystems: an experimental assessment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45, 1041-1057. ( 10.4319/lo.2000.45.5.1041) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Short FT, Wyllie-Echeverria S. 1996. Natural and human-induced disturbance of seagrasses. Environ. Conserv. 23, 17-27. ( 10.1017/S0376892900038212) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes BB, Eby R, Van Dyke E, Tinker MT, Marks CI, Johnson KS, Wasson K. 2013. Recovery of a top predator mediates negative eutrophic effects on seagrass. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15 313-15 318. ( 10.1073/pnas.1302805110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enríquez S, Olivé I, Cayabyab N, Hedley JD. 2019. Structural complexity governs seagrass acclimatization to depth with relevant consequences for meadow production, macrophyte diversity and habitat carbon storage capacity. Sci. Rep. 9, 14657. ( 10.1038/s41598-019-51248-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sand-Jensen K. 1977. Effect of epiphytes on eelgrass photosynthesis. Aquat. Bot. 3, 55-63. ( 10.1016/0304-3770(77)90004-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee KS, Dunton KH. 1999. Inorganic nitrogen acquisition in the seagrass Thalassia testudinum: development of a whole-plant nitrogen budget. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44, 1204-1215. ( 10.4319/lo.1999.44.5.1204) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fourqurean JW, Zieman JC. 2002. Nutrient content of the seagrass Thalassia testudinum reveals regional patterns of relative availability of nitrogen and phosphorus in the Florida Keys USA. Biogeochemistry 61, 229-245. ( 10.1023/A:1020293503405) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brodersen KE, Kühl M. 2022. Effects of epiphytes on the seagrass phyllosphere. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 821614. ( 10.3389/fmars.2022.821614) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hemminga MA, Mateo MA. 1996. Stable carbon isotopes in seagrasses: variability in ratios and use in ecological studies. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 140, 285-298. ( 10.3354/meps140285) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vizzini S, Sarà G, Mateo MA, Mazzola A. 2003. δ13C and δ15N variability in Posidonia oceanica associated with seasonality and plant fraction. Aquat. Bot. 76, 195-202. ( 10.1016/S0304-3770(03)00052-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maberly SC, Raven JA, Johnston AM. 1992. Discrimination between 12C and 13C by marine plants. Oecologia 91, 481-492. ( 10.1007/BF00650320) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidson EA, Howarth RW. 2007. Environmental science: nutrients in synergy. Nature 449, 1000-1001. ( 10.1038/4491000a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conley DJ, Paerl HW, Howarth RW, Boesch DF, Seitzinger SP, Havens KE, Lancelot C, Likens GE. 2009. Controlling eutrophication: nitrogen and phosphorus. Science 323, 1014-1015. ( 10.1126/science.1167755) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andskog MA, Layman C, Allgeier JE. 2023. Seagrass production around artificial reefs is resistant to human stressors. Dryad, Dataset. ( 10.5061/dryad.37pvmcvqn) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Andskog MA, Layman C, Allgeier JE. 2023. Seagrass production around artificial reefs is resistant to human stressors. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6724068) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Andskog MA, Layman C, Allgeier JE. 2023. Seagrass production around artificial reefs is resistant to human stressors. Dryad, Dataset. ( 10.5061/dryad.37pvmcvqn) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Andskog MA, Layman C, Allgeier JE. 2023. Seagrass production around artificial reefs is resistant to human stressors. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6724068) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

All data and code used in the analysis are online at Data Dryad: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.37pvmcvqn [54].

Additional information is provided in the electronic supplementary material [55].