Abstract

Background:

The current study tested whether oral Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC: 0-, 10-, and 20-mg) pretreatment would attenuate polysensory cue-induced craving for marijuana.

Methods:

Cannabis dependent participants (7 males and 7 females, who smoked on average 5.4 ± 1.1 blunts daily) completed 3 experimental sessions (oral THC pretreatment dose; counterbalanced order) using a placebo-controlled within-subject crossover design. During each session, participants completed a baseline evaluation and were first exposed to neutral cues then marijuana cues while physiological measures and subjective ratings of mood, craving, and drug effect were recorded.

Results:

Following placebo oral THC pretreatment, marijuana (vs. neutral) cues significantly increased ratings of marijuana craving (desire and urge to use, Marijuana Craving Questionnaire (MCQ)-Compulsivity scale), anxious mood and feeling hungry. Males also reported feeling more “Down” during marijuana cues relative to females. Pretreatment with oral THC (10-mg and/or 20-mg vs. placebo) significantly attenuated marijuana cue-induced increases in craving and anxiety but not hunger. Oral THC attenuation of the cue-induced increase in MCQ-Compulsivity ratings was observed in females only. Oral THC produced statistically (but not clinically) significant increases in heart rate and decreases in diastolic blood pressure, independent of cues.

Conclusions:

These marijuana-cue findings replicate earlier results and further demonstrate that oral THC can attenuate selected effects during marijuana multi-cue exposure, and that some of these effects may be sex-related. Results of this study suggest oral THC may be effective for reducing marijuana cue-elicited (conditioned) effects. Further study is needed to determine whether females may selectively benefit from oral THC for this purpose.

Keywords: Marijuana, Craving, Cues, THC, Dronabinol, Cannabis dependence

1. Introduction

Marijuana is the most common illegal drug reported as the primary problem among substance abuse treatment seekers (SAMHSA, 2014). Psychosocial interventions are somewhat efficacious, but most cannabis dependent patients in treatment do not achieve abstinence (Copeland et al., 2001; Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004). Currently there are no FDA-approved medications for treating cannabis use disorder (CUD; Nordstrom and Levin, 2007; Vandrey and Haney, 2009). Use of agonist or partial agonist medications is generally safe and effective for treating other drug use disorders, specifically nicotine replacement products and varenicline for tobacco use disorders (Jorenby et al., 2006), and methadone and buprenorphine for opioid use disorders (Stotts et al., 2009). The psychoactive constituent of marijuana, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; Elsohly, 2005), is an agonist at the cannabinoid type 1 receptor. Data suggest that an orally bioavailable formulation of THC, dronabinol, has low abuse liability (Calhoun et al., 1998) and alleviates some signs and symptoms of cannabis withdrawal, with few subjective effects of its own when assessed in cannabis-experienced volunteers (Haney et al., 2004; Budney et al., 2007). However, its effect on cue-induced marijuana craving has not been investigated.

Despite controversy regarding the validity of craving as a construct (Witkiewitz and Marlatt, 2004) and imprecision with which it has been conceptualized, defined, and assessed (Pickens and Johanson, 1992; Sayette et al., 2000), craving remains a central feature associated with drug use (O’Brien et al., 1998; Wolfling et al., 2008; Epstein et al., 2009; Preston et al., 2009) and relapse (Childress et al., 1988; Lowman et al., 2000; Oslin et al., 2009). Previously we demonstrated that a marijuana cue-reactivity paradigm reliably induced craving among daily marijuana smokers (Lundahl and Johanson, 2011). Cannabis-dependent individuals responded to marijuana-related tactile, olfactory, and visual cues with significantly increased self-reported craving and compulsivity to use marijuana, relative to neutral cues. Moreover, marijuana-cue craving was population-, cue-, and drug specific: only marijuana smokers (not controls) reported increased craving for marijuana (but not neutral) cues, but not for nicotine or alcohol. Others have shown that marijuana craving can be elicited using visual cues (Wolfling et al., 2008; Charboneau et al., 2013) as well as verbal imagery, visual, tactile, and olfactory cues (Haughey et al., 2008; McRae-Clark et al., 2011). Adolescents exposed to marijuana cues also report increased craving (Nickerson et al., 2011) and exhibit skin conductance responses (Gray et al., 2008, 2011). Craving is a symptom of CUD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and cannabis withdrawal (Budney et al., 2004, 2008; Haney, 2005; Vandrey et al., 2008), and can be considered a target in studies of medication efficacy.

Because marijuana cue-exposure reliably elicits marijuana craving, the cue reactivity model may afford an initial screen of medication efficacy for CUD treatment. Pharmacologic agents that reduce cue reactivity in the laboratory may produce similar effects in the natural environment, potentially decreasing relapse risk. The cue reactivity paradigm has been used to test promising anti-craving medications for cocaine (Kranzler and Bauer, 1992; Robbins et al., 1992; Hersh et al., 1995; Berger et al., 1996; Ehrman et al., 1996; LaRowe et al., 2007; Reid and Thakkar, 2009), nicotine (Reid et al., 2007; Rohsenow et al., 2008; Franklin et al., 2011; Ditre et al., 2012) and alcohol (Rohsenow et al., 2000; Hutchison et al., 2001). Across studies, cue-elicited craving was observed despite variable efficacy of medications tested. Authors concluded that drug cue-elicited responses provide a valuable set of outcomes for use in medication trials of anti-craving agents, and that screening medications with cue reactivity procedures may identify mechanisms relevant to pharmacotherapy even if not supporting efficacy of the medication itself (Berger et al., 1996). To our knowledge, the current study is the first to use this approach in marijuana treatment research.

Few drug cue reactivity studies have analyzed gender effects, but those that have yielded inconsistent results. Although females reported greater cocaine craving in response to cocaine cues more than males in one study (Robbins et al., 1999), other studies found greater reactivity in males (Sterling et al., 2004) or no gender differences (Avants et al., 1995; Fox et al., 2006). Similarly, some have reported stronger cue-elicited nicotine craving responses in females than males (Field and Duka, 2004) whereas others failed to find gender differences (Franklin et al., 2004; Niaura et al., 1988). Few studies have investigated gender differences in response to heroin-related cues, although Yu et al. (2007) found greater craving among females. In the only published study that examined gender differences in marijuana cue reactivity, males and females did not differ in marijuana-cue elicited craving (Lundahl and Johanson, 2011). Thus, it is unclear whether there are gender differences in drug cue-elicited craving generally (all substances) or specifically for marijuana.

The current study evaluated whether acute oral THC (dronabinol: 0-, 10-, and 20-mg) pretreatment could attenuate polysensory cue-induced craving for marijuana in non-treatment seeking, cannabis dependent participants. We hypothesized marijuana cue exposure would increase craving relative to neutral cues, and oral THC would dose-dependently attenuate craving. We explored sex differences in cue reactivity and evaluated whether oral THC differentially altered cue reactivity and craving.

2. Method

2.1. Participant selection

The local IRB approved all procedures. Participants were recruited through local newspaper advertisements and word of mouth referrals. Candidates underwent an initial structured telephone screening and those without major contraindications (e.g., chronic medical or psychiatric problems) were invited to the laboratory for additional screening.

Participants provided a breath sample to assess expired alcohol levels (Alco-Sensor Model III Intoximeters; St. Louis, MO; positive breath alcohol concentration cutoff >0.002%) and a urine sample to assess recent use of cannabinoids (positive cutoff ≥50 ng/ml), amphetamines (positive cutoff ≥1000 ng/ml), cocaine metabolites, opioids, and benzodiazepines (positive cutoffs ≥300 ng/ml), and barbiturates (positive cutoff ≥200 ng/ml). The Structured Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., 1996) was administered to evaluate Axis I psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders. Participants also completed questionnaires regarding their drug and alcohol use. Volunteers were paid for their participation.

Eligible participants were between the ages of 18 and 44 yr, met DSM-IV criteria for Cannabis Dependence but no other psychiatric or substance use disorder (except Nicotine Dependence), and were in good health. Females could not be pregnant (based on urine HCG test) and self-reported they were not lactating and were using medically effective contraception. Potential participants could not have major neurological, cardiovascular, pulmonary, or systemic diseases. All participants had to provide sober (BAC < 0.002%) informed consent and demonstrate adequate cognitive functioning (i.e., estimated IQ > 85; Zachary, 1986). Based on screening results, those who were not excluded were invited to participate in the study.

2.2. Design and procedure

2.2.1. Protocol timeline.

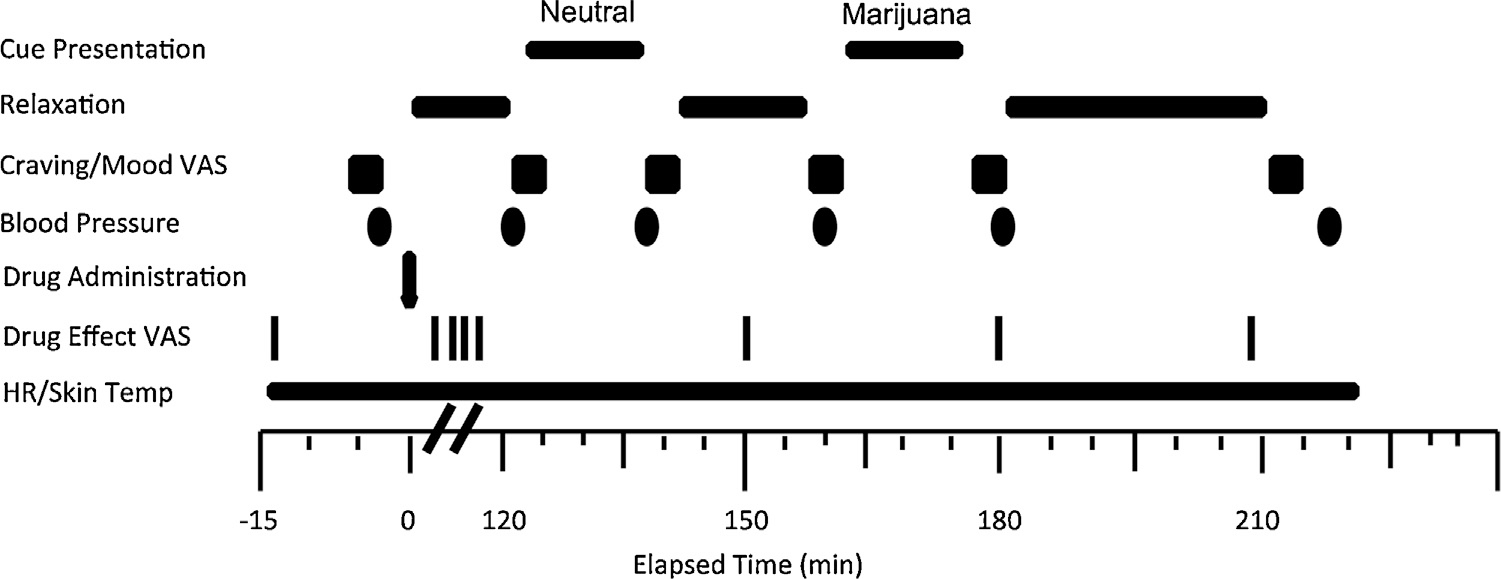

During three sessions, each separated by at least 7 days, each participant was pretreated with oral THC (0-mg, 10-mg, and 20-mg) and underwent the marijuana cue exposure procedure illustrated in Fig. 1 and described below. The cue exposure session began 120-min after pretreatment so that cue reactivity assessments occurred during peak oral THC effect (120–240 min after administration). Thus, marijuana cue reactivity was assessed following pre-treatment with placebo and two doses of oral THC in the same subjects.

Fig. 1.

Cue session timeline.

Participants spent the evening before each experimental session on an inpatient research unit to restrict alcohol and drug use during the 12-h preceding the session. Participants were admitted to the residential unit at 9 PM, slept there, and ate breakfast about 7:30 AM the next morning. They were transported to the laboratory via taxicab with a staff escort. Upon arrival, participants provided breath and urine samples for toxicology screening. Participants sat in a reclining chair in a light- and sound-attenuated private testing room for pre-drug baseline collection of craving and mood visual analog scale (VAS) ratings, subjective drug effect VAS ratings, and physiologic data. For 2-h following oral drug administration, participants could read or watch television in a recreation room, before returning to the private testing room for the entire cue exposure session. Subjective drug effect VAS ratings were recorded 15-min before oral THC administration, then at 30-min intervals for the duration of the session; post-drug data collection was timed so as not to interrupt cue exposure.

2.2.2. Drug preparation and administration.

Dronabinol (oral THC) was obtained from Unimed Pharmaceuticals (Somerville, NJ) in 10-mg capsules. Each dose was encapsulated in opaque, similarly colored, size 00 capsules; lactose was used for placebo. Dose order was counterbalanced and double blinded.

2.2.3. Experimental session.

Each participant was fitted with a blood pressure (BP) cuff and telemetric physiologic recording device (Mini-Mitter Co., Inc., St. Louis, MO) that collected skin temperature and heart rate. The session consisted of three 10-min phases (baseline, neutral cue and marijuana cue exposure) followed by a 120-min recovery period. Order of neutral and marijuana-related cues was fixed to avoid carry-over effects of drug cue-related reactivity (e.g., Monti et al., 1987). All instructions to participants were delivered over a speaker in the chamber to minimize disturbance during cue exposure.

Baseline:

Participants were instructed to “relax” for 10 min while physiological data were recorded (skin temperature, heart rate and BP), then participants completed questionnaires (≈5 min; described below). The neutral-cue phase followed immediately afterward.

Neutral-cue phase:

During the 10-min neutral-cue exposure phase, participants were instructed to remove the inverted opaque cover from the “A” container that revealed pencils, erasers, a ruler, and scented floral potpourri in a small bowl. Participants were asked to handle and smell these items while they viewed a videotaped film clip depicting nature scenes set to classical music. After this phase, participants were instructed to return these items to the table and replace the opaque cover. Physiological data were recorded, participants were prompted to complete the next questionnaire set, then to “sit back and relax” until the next phase began.

Marijuana-cue phase:

During the 10-min marijuana-cue exposure phase, participants were instructed to remove the opaque cover from the “B” container that revealed marijuana-related paraphernalia, including a recently used bong, pipe, rolling papers, hollowed-out blunts, and “roach clip”. Participants were instructed to handle and smell these items while viewing a film clip of young adults smoking marijuana. Scenes depicted preparing marijuana for smoking (rolling blunts, joints), and smoking marijuana (joint, bong, blunt, pipe) in different settings (party, bedroom, on a date). Video scenes were set to slow dance music. After this phase, participants were prompted to return the items to the table and replace the cover. Physiological data were recorded and participants completed the next questionnaire set. Marijuana was never available to the participants.

Recovery period:

Following the marijuana-related cue phase participants were escorted to the recreation room where they watched television or read for 120 min or until subjective drug effects and vital signs returned to baseline levels. Participants were debriefed and allowed to leave the laboratory.

2.2.4. Physiological responses.

Heart rate and skin temperature were monitored continuously and recorded at 1-min intervals throughout the session. BP was measured at baseline, immediately after neutral and marijuana cue exposure, and every 30-min until discharge (i.e., recovery period). Physiologic data collected during the recovery period were excluded from analyses.

2.2.5. Subjective responses.

Participants were presented with computerized VAS mood ratings and instructed to place a vertical mark on a 100-mm line anchored on the left by the words not at all and on the right by the word extremely that corresponded with their responses to the following mood-related items: “How (“Anxious”, “Upset“, “Content”, “Happy”, “Confused”, “Tired”, and “Hungry”) do you feel right now?”.

Four VAS marijuana craving items included the phrase, “How strong is your…” followed by “desire to smoke marijuana right now?”, “desire not to smoke marijuana right now?”, “urge to smoke marijuana right now?”, and “craving for marijuana right now?” Responses were recorded in the same way as the mood items described above.

Marijuana craving also was assessed using the Marijuana Craving Questionnaire–Brief Form (MCQ-BF; Singleton et al., 2002). This 17-item instrument represents four domains of marijuana craving from the original 47-item MCQ (Heishman et al., 2001): (1) Compulsivity, inability to control marijuana use; (2) Emotionality, marijuana use for relief from withdrawal or negative affect; (3) Expectancy, anticipation of positive consequences from smoking marijuana; and (4) Purposefulness, intention and planning of marijuana use for positive consequences.

Nicotine craving was measured using the 10-item Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU) Brief Form (Cox et al., 2001). Items represent two factors from the original 32-item QSU (Tiffany and Drobes, 1991): desire and intention to smoke cigarettes (Factor 1), and anticipation of relief from negative affect with an urgent desire to smoke cigarettes (Factor 2). Four drug-effect VAS items addressed oral dronabinol effects, with the phrase, “How much do you…” followed by “feel any effects?”, “like the effects?”, “feel high?”, and “want more?” Responses were recorded similarly as the mood and craving items.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 22 for Mac (IBM, 2013). One-way ANOVAs and non-parametric tests were used to examine gender differences in the screening measures. The ten 1-min samples immediately preceding the first cue phase were averaged to yield baseline heart rate and skin temperature values. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) failed to reveal significant baseline differences across sessions, so raw data were used in all subsequent analyses. Heart rate and skin temperature data were averaged over each 10-min cue-exposure period to yield a mean value for each condition. Due to movement artifact during the first minute of each cue condition (when participants sat forward and opened the box containing the tactile cues), the 1-min data point was excluded from both the heart rate and skin temperature data average. Subjective and physiological data were analyzed using 2 (gender) × 3 (dronabinol dose) × 2 (cue: neutral/marijuana) mixed model ANOVAs, with dronabinol dose and cue as the repeated factors. Subjective effects of dronabinol (in the absence of cues) were tested using repeated measures ANOVA. Simple contrasts were used to examine significant interactions. Significant main effects were examined using Tukey post hoc tests. All effects were tested at the 0.05 level of significance.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

The 14 (7 male) participants (mean ± 1 SD) were 28.2 ± 5.2 yr old, reported their age at first marijuana use was 14.4 ± 3.3 yr, and estimated their mean lifetime marijuana use as 11,378 ± 6501 episodes. Participants reported smoking 5.4 ± 1.1 blunts per day and all provided cannabinoid-positive urine samples. All participants reported currently smoking tobacco cigarettes and 12 reported regular use (defined as 3×/week or more). All participants reported past-month alcohol use, and two reported regular use (i.e., 3×/week). One participant reported one lifetime use of MDMA and none reported lifetime cocaine or non-prescription opioid use. All participants were African American.

Males and females did not significantly differ in age, years of education, alcohol, nicotine, or marijuana use (Table 1). They also did not differ in age at first use of marijuana, current daily use, duration of daily use, or estimated lifetime episodes of marijuana use.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and drug use variables.

| Males (n = 7) mean (SD) | Females (n = 7) mean (SD) | Contrasts | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age at study (yr) | 26.29 (4.11) | 30.14 (5.67) | ns |

| Years of education | 12.43 (0.79) | 12.29 (1.38) | ns |

| Age at first use of marijuana (yr) | 13.57 (1.99) | 15.29 (4.15) | ns |

| No. times smoke per day | 5.00 (1.63) | 3.57 (1.99) | ns |

| Duration of daily marijuana use (mo) | 96.00 (62.36) | 130.29 (50.16) | ns |

| Estimated lifetime episodes of marijuana use | 11,905.00 (6391.81) | 10,852.43 (7076.84) | ns |

| Episodes of MDMA use | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.14 (0.38) | ns |

| Regular alcohol use | 28% | 14% | ns |

| Regular tobacco use | 85% | 85% | ns |

note: Gender contrasts were tested using one-way ANOVAs and Chi-square analysis for categorical variables.

3.2. Physiological responses

Main effects for drug pretreatment were found on diastolic BP, F(2, 26) = 3.99, p < .03, Cohen’s d = 0.83, and heart rate, F(2, 26) = 10.46, p < 0.001, d = 1.34. Post hoc comparisons indicated that both active (10 and 20 mg) doses of oral THC significantly lowered diastolic BP and elevated heart rate relative to placebo, independent of cue type. There were no significant gender, drug pretreatment or cue-exposure effects on systolic BP or skin temperature, and no significant interactions.

3.2.1. Subjective responses.

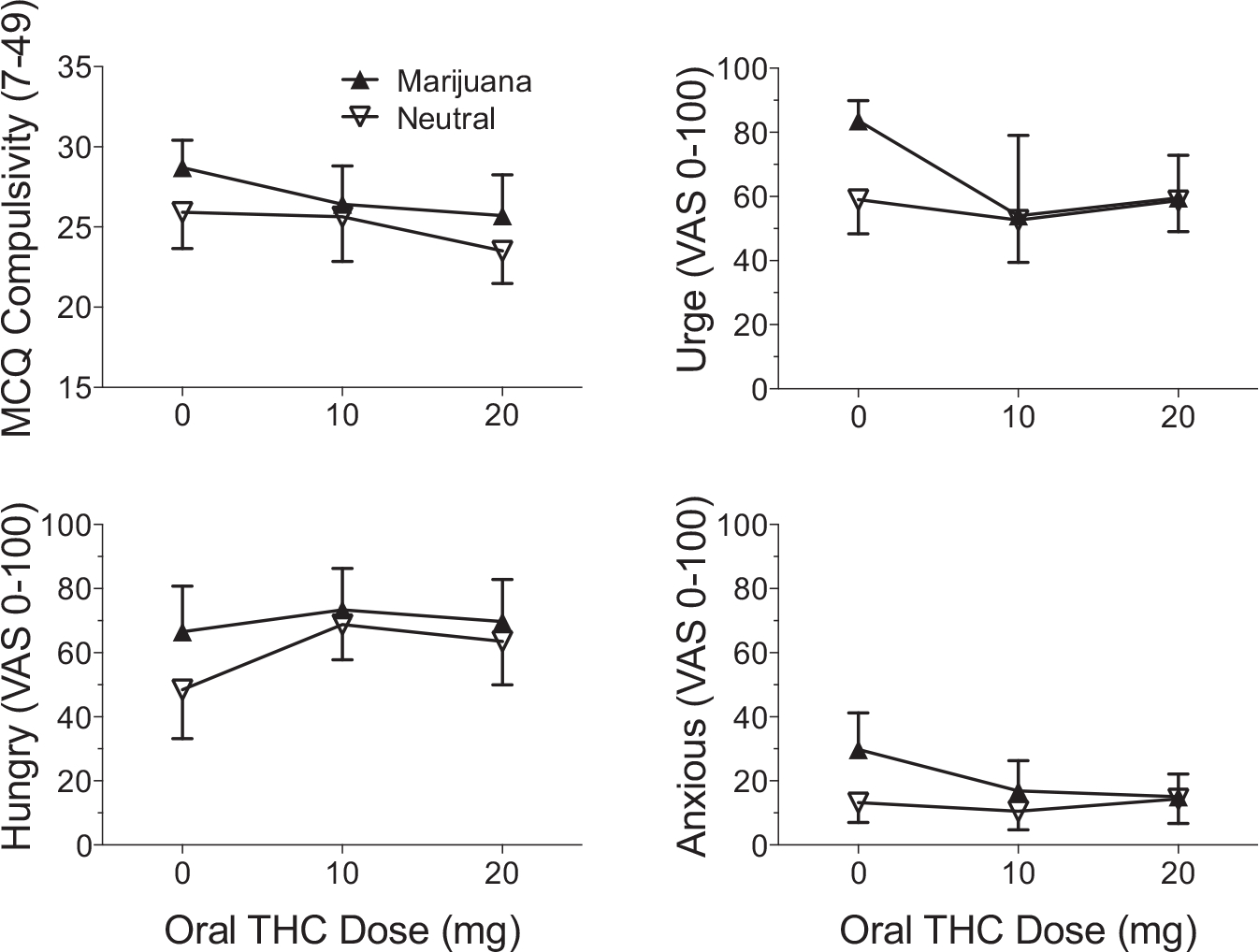

Effects of dronabinol on cue-elicited responses. Drug pretreatment × cue type interactions revealed that both active oral THC doses attenuated cue-elicited increases in “urge to smoke marijuana”, F(2, 24) = 7.28, p = 0.003, d = 0.56 (Fig. 2), “desire to use marijuana”, F(2, 24) = 6.32, p = 0.013, d = 0.55, and “anxious”, F(2, 24) = 4.01, p = 0.032, d = 0.49 (Fig. 2). Oral THC pretreatment and marijuana cue exposure did not alter tobacco cigarette craving (QSU).

Fig. 2.

Scores on MCQ Compulsivity scale and ratings on VAS item “Hungry” (left panel) and “Urge to Smoke Marijuana” and “Anxious” (right panel) for each condition. Standard errors of the mean are shown. In both panels, scores and ratings are significantly greater during marijuana cue exposure relative to neutral cue exposure. Right panel illustrates drug × cue type interaction; both 10 mg and 20 mg oral THC significantly attenuated the cue-related increases observed during marijuana cue exposure in placebo oral THC condition.

3.2.2. Effects of cue type.

A main effect for cue type indicated that marijuana (vs. neutral) cue exposure significantly increased MCQ Compulsivity scale scores, F(1, 12) = 14.86, p = 0.002, d = 0.50 (Fig. 2). Scores on other MCQ scales did not differ as a function of cue exposure (emotionality, F(1, 12) = 0.15, p = 0.71; expectancy, F(1, 12) = 0.99, p = 0.34; purposeful, F(1, 12) = 0.16, p = 0.70). Marijuana cue-induced increases were observed for VAS ratings of “urge to smoke marijuana”, F(1, 12) = 6.55, p < 0.03, d = 0.45 (Fig. 2); “desire to use marijuana”, F(1, 12) = 10.91, p < 0.01, d = 0.44; “craving for marijuana”, F(1, 12) = 19.71, p < 0.001, d = 0.62; “hungry”, F(1, 12) = 9.64, p < 0.01, d = 0.54 (Fig. 2); and “anxious”, F(1, 12) = 17.78, p < 0.001, d = 0.59 (Fig. 2). There were no other significant effects of cue type.

3.2.3. Effects of dronabinol.

There were no significant subjective effects of dronabinol independent of cue exposure.

3.2.4. Gender analyses.

Secondary analyses revealed a gender × drug × cue type interaction on the MCQ Compulsivity scale F(2, 11) = 4.00, p < 0.05, d = 0.37. Simple contrasts indicated that the marijuana cue-related increase in MCQ Compulsivity was attenuated by both active oral THC doses, but only among females, Finally, there was a gender × cue interaction on the VAS item “Down”, F(2, 11) = 5.44, p < 0.05, d = 0.24, where males reported feeling more “Down” during marijuana cue exposure relative to neutral cue exposure.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the ability of dronabinol (oral THC) to alter marijuana cue reactivity. Both active dronabinol doses significantly attenuated marijuana cue-induced increases in marijuana craving and anxiety ratings without producing notable subjective effects of their own. These findings extend previous research that supports the potential use of dronabinol as a pharmacotherapy for CUD (Levin et al., 2011; Vandrey et al., 2013).

In contrast to earlier studies in which high dronabinol doses (40–120 mg/day) were needed to attenuate cannabis withdrawal symptoms, relatively low (10 and 20 mg) doses of dronabinol were effective in blocking cue-induced marijuana craving in these cannabis dependent individuals. Both active doses also decreased anxiety during marijuana cue exposure, but only in females. Taken together, this suggests dronabinol may be more potent for reducing marijuana cue-elicited (conditioned) effects than withdrawal symptom (unconditioned) effects and that females, who have been shown in some studies to be more drug cue-responsive than males, may selectively benefit from dronabinol for this purpose.

Dronabinol alleviates some signs and symptoms of cannabis withdrawal (Budney et al., 2007; Haney et al., 2004, 2008; Vandrey et al., 2013) and reduces some subjective effects of smoked cannabis (Hart et al., 2002a), though not consistently (Vandrey et al., 2013). Dronabinol alone has not been shown to reduce cannabis self-administration in laboratory studies (Hart et al., 2002b; Haney et al., 2008) or a placebo-controlled clinical trial that investigated dronabinol (20-mg BID) maintenance (Levin et al., 2011). Vandrey et al. (2013) reported that short-term stabilization on high daily doses of dronabinol (up to 120 mg/day) suppressed cannabis withdrawal symptoms, but not subjective effects of smoked cannabis after a supervised abstinence period. The authors concluded that dronabinol treatment might help individuals whose cannabis withdrawal is severe and a barrier to abstinence. Thus, dronabinol displays only some characteristics of an effective agonist replacement treatment, suggesting it would be preferable to combine dronabinol with medications that possess complementary mechanisms of action (Haney et al., 2008), including those that block both the unconditioned and conditioned reinforcing effects of marijuana.

Results from this study mirror previous studies demonstrating that exposure to drug-related cues elicits craving. Cannabis-dependent individuals in this study responded to marijuana cues with increased urge and desire to smoke marijuana, craving for marijuana, and feelings of hunger and anxiety, but no urge to use tobacco. Others have similarly reported that marijuana cue exposure increases marijuana craving in regular cannabis users (Haughey et al., 2008; Wolfling et al., 2008; Gray et al., 2008; Bordnick et al., 2009), but not craving for other psychoactive substances (Lundahl and Johanson, 2011). The cue reactivity paradigm thus provided a valid and reliable signal against which the effects of dronabinol could be assessed.

In contrast to Gray et al. (2008), who found that MCQ Expectancy and Purposefulness scale scores increased after marijuana cue exposure, in the current study marijuana cue-elicited increases were observed only on MCQ Compulsivity scale scores. This discrepancy may be due to between-study differences in sample characteristics, marijuana use patterns and length of marijuana cue exposure. Specifically, the two studies (Gray et al., 2008 vs. present study, respectively) differed in (1) testing adolescents vs. adults, (2) lighter vs. heavier patterns of marijuana use (2 joints daily vs. 5.4 blunts daily), and (3) length of marijuana cue exposure (4.5 min [three 90-s segments] vs. 10 min). The longer lifetime history of our adult participants, their heavier use, and the longer experimental cue exposure could potentially explain why we found that only the Compulsivity subscale was sensitive.

The cue-induced increase in anxiety in this study differs from our earlier study (Lundahl and Johanson, 2011), in which anxiety was not altered by marijuana cue exposure. Given identical methods in the two studies, this inconsistency may be due to differences in marijuana use in the two participant samples: the current sample reported smoking about twice as much marijuana daily as the previous sample (5.4 vs. 2.1 blunts/day). Magnitude of marijuana cue-induced craving was similar across studies, suggesting that more severe cannabis dependence may be associated with greater anxiety in response to marijuana cues. However, the current results echo those of McRae-Clark et al. (2011), who found that self-reported anxiety correlated with marijuana craving measures in both their stress-exposed and non-stress control groups.

The finding that marijuana-related cues increased self-ratings of “hungry” is novel. A common side effect of THC use is appetite stimulation. Thus, marijuana-related cues may act as conditioned stimuli to increase appetite. This interesting finding confirms the ability of the cue paradigm to elicit a robust, drug-appetitive response.

Consistent with prior studies (Gray et al., 2008, 2011; Lundahl and Johanson, 2011; Nickerson et al., 2011) we did not observe marijuana cue-induced changes in BP, heart rate and skin temperature. In their meta-analysis of 41 cue reactivity studies, Carter and Tiffany (1999) concluded that while cue-exposure resulted in robust craving responses for alcohol, nicotine, cocaine, and opiates, cue-elicited physiological changes were far less reliable.

Finally, studies on cue-induced craving for substances other than marijuana suggest females crave cocaine in response to cocaine cues (Robbins et al., 1999), report greater cigarette craving during smoking cues (Field and Duka, 2004), and stronger cue-elicited craving responses for heroin (Yu et al., 2007) relative to males, although other studies found stronger craving responses in males (Sterling et al., 2004) or no gender differences (Fox et al., 2006; Lundahl and Johanson, 2011). Most drug cue reactivity studies have not analyzed sex differences. The present study is the first to observe sex differences in marijuana cue reactivity, but these preliminary findings require replication in a larger sample.

Several limitations must be considered. First, generalizability of the findings is decreased by the relatively small and exclusively African American sample. Second, consistent with prior research, cues were presented in fixed order: neutral cues always preceded marijuana cues to prevent possible carryover effects of the marijuana cues (Monti et al., 1987; Rohsenow et al., 2000, 2001). This fixed order introduces potential time-dependent confounds. Future studies should examine possible order effects and investigate whether carry-over effects exist. Third, measuring a broader array of outcomes (e.g., skin conductance, pupil diameter) might reveal further effects of dronabinol on marijuana cue reactivity. Fourth, participants did not have access to marijuana following cue exposure, a behavioral set that may have increased certain responses (e.g., anxiety) while dampening others (e.g., heart rate) (Jones, 1971). Finally, because of small sample size the study may have been underpowered to detect gender differences. Thus interpretations of gender differences must be viewed as exploratory.

In conclusion, this laboratory investigation demonstrated that low-dose dronabinol blocked increases in marijuana cue-induced craving and anxiety in daily, heavy marijuana users. Craving is associated with use during daily life (Preston et al., 2009) and predicts attrition and drug use during treatment for cocaine and heroin dependence (Heinz et al., 2006) and time to relapse in cocaine users (Paliwal et al., 2008). Thus, craving is a reasonable target for medication development efforts. Marijuana-using individuals confront olfactory, tactile, and visual drug-related cues in their natural environments, and for those who report cue-induced craving as a factor in their continued use or relapse, dronabinol combined with other medications may present a viable treatment option. Results support using cue reactivity procedures to screen medications for treatment of CUD that may warrant further investigation in controlled clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Chris-Ellyn Johanson, PhD, Cheryl Aubie, PhD, Kelty Berardi, PhD Robert Kender, PhD, Heather Durdle, PhD, Manny Tancer, MD, Michael Eadie, MD, Ken Bates, Deborah Kish, and staff at the Psychiatric and Addiction Research Center.

Role of funding source

NIH grant R21 DA019236 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (to LHL), research funds (Joe Young, Sr,/Helene Lycaki) from the State of Michigan, and the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority, supported this research. The study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and decision to submit the paper for publication were all completed at the sole discretion of the authors. This study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00218504.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders, fifth ed. APA, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Avants SK, Margolin A, Kosten TR, Cooney NL, 1995. Differences between responders and nonresponders to cocaine cues in the laboratory. Addict. Behav. 20, 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SP, Hall S, Mickalian JD, Reid MS, Crawford CA, Delucchi K, Carr K, Hall S, 1996. Haloperidol antagonism of cue-elicited cocaine craving. Lancet 347, 504–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordnick PS, Copp HL, Traylor A, Graap KM, Carter BL, Walton A, Ferrer M, 2009. Reactivity to cannabis cues in virtual reality environments. J. Psychoactive Drugs 41, 105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, Vandrey R, 2004. Review of the validity and significance of cannabis withdrawal syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 1967–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Vandrey RG, Hughes JR, Moore BA, Bahrenburg B, 2007. Oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol suppresses cannabis withdrawal symptoms. Drug Alcohol Depend. 86, 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Vandrey RG, Hughes JR, Thostenson JD, Bursac Z, 2008. Comparison of cannabis and tobacco withdrawal: severity, and contribution to relapse. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 35, 362–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun SR, Galloway GP, Smith DE, 1998. Abuse potential of dronabinol (Marinol). J. Psychoactive Drugs 30, 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Tiffany ST, 1999. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction 94, 327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charboneau EJ, Dietrich MS, Park S, Cao A, Watkins TJ, Blackford JU, Benningfield MM, Martin PR, Buchowski MS, Cowan RL, 2013. Cannabis cue-induced brain activation correlates with drug craving in limbic and visual salience regions: preliminary results. Psychiatry Res. 214, 122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, McLellan AT, Ehrman R, O’Brien CP, 1988. Classically Conditioned Responses in Opioid and Cocaine Dependence: A Role in Relapse? Learning Factors in Substance Abuse. NIDA Res. Monogr, 94. U.S. Gov. Printing Office, Washington, DC, pp. 25–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J, Swift W, Rees V, 2001. Clinical profile of participants in a brief intervention program for cannabis use disorder. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 20, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG, 2001. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings [comment]. Nic. Tob. Res. 3, 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Oliver JA, Myrick H, Henderson S, Saladin ME, Drobes DJ, 2012. Effects of divalproex on smoking cue reactivity and cessation outcomes among smokers achieving initial abstinence. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 20, 293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, Cornish JW, Childress AR, O’Brien CP, 1996. Failure of ritanserin to block cocaine cue reactivity in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 42, 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsohly, 2005. Chemical constituents of marijuana: the complex mixture of natural cannabinoids. Life Sci. 78, 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Willner-Reid J, Vahabzadeh M, Mezghanni M, Lin JL, Preston KL, 2009. Real-time electronic diary reports of cue exposure and mood in the hours before cocaine and heroin craving and use. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Duka T, 2004. Cue reactivity in smokers: the effects of perceived cigarette availability and gender. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 78, 647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, 1996. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). APA, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Garcia M Jr., Kemp K, Milivojevic V, Kreek MJ, Sinha R, 2006. Gender differences in cardiovascular and corticoadrenal response to stress and drug cues in cocaine dependence individuals. Psychopharmacology 185, 348–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TR, Napier K, Ehrman R, Gariti P, O’Brien CP, Childress AR, 2004. Retrospective study: influence of menstrual cycle on cue-induced cigarette craving. Nic. Tob. Res. 6, 171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin T, Wang Z, Suh JJ, Hazan R, Cruz J, Li Y, Goldman M, Detre JA, O’Brien CP, Childress AR, 2011. Effects of varenicline on smoking cue-triggered neural and craving responses. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 516–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray KM, LaRowe SD, Upadhyaya HP, 2008. Cue reactivity in young marijuana smokers: a preliminary investigation. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 22, 582–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray KM, LaRowe SD, Watson NL, Carpenter MJ, 2011. Reactivity to in vivo marijuana cues among cannabis-dependent adolescents. Addict. Behav. 36, 140–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, 2005. The marijuana withdrawal syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Psychiatric Rep. 7, 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Hart CL, Vosburg SK, Nasser J, Bennert A, Zubaran C, Foltin RW, 2004. Marijuana withdrawal in humans: effects of oral THC or divalproex. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 158–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Hart CL, Vosburg SK, Comer SD, Reed SC, Foltin RW, 2008. Effects of THC and lofexidine in a human laboratory model of marijuana withdrawal and relapse. Psychopharmacology 197, 157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Ward AS, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, 2002a. Effects of oral THC maintenance on smoked marijuana self-administration. Drug Alcohol Depend. 67, 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Ward AS, Haney M, Comer SD, Foltin RW, Fischman MW, 2002b. Comparison of smoked marijuana and oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in humans. Psychopharmacology 164, 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughey HM, Marshall E, Schacht JP, Louis A, Hutchison KE, 2008. Marijuana withdrawal and craving: influence of the cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) genes. Addiction 103, 1678–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz AJ, Epstein DH, Schroeder JR, Singleton EG, Heishman SJ, Preston KL, 2006. Heroin and cocaine craving and use during treatment: measurement validation and potential relationships. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 31, 355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heishman SJ, Singleton EG, Liguori A, 2001. Marijuana Craving Questionnaire: development and initial validation of a self-report instrument. Addiction 96, 1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh D, Bauer LO, Kranzler HR, 1995. Carbamazepine and cocaine-cue reactivity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 39, 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KE, Swift R, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Davidson D, Almeida A, 2001. Olanzapine reduces urge to drink after drinking cues and a priming dose of alcohol. Psychopharmacology 155, 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM, 2013. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. Version 22.0 for Mac OS X. IBM Inc., Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RT, 1971. Marihuana-induced high: influence of expectation, setting and previous drug experience. Pharmacol. Rev. 33, 359–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR, 2006. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs. placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 296, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Bauer LO, 1992. Bromocriptine and cocaine cue reactivity in cocaine-dependent patients. Br. J. Addict. 87, 1537–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRowe SD, Myrick H, Hedden S, Mardikian P, Saladin M, McRae A, Brady K, Kalivas PW, Malcolm R, 2007. Is cocaine desire reduced by N-acetylcysteine? Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 1115–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin FR, Mariani JJ, Brooks DJ, Pavlicova M, Cheng W, Nunes EV, 2011. Dronabinol for the treatment of cannabis dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 116, 142–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowman C, Hunt WA, Litten RZ, Drummond DC, 2000. Research perspectives on alcohol craving: an overview. Addiction 95 (Suppl. 2), S45–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl LH, Johanson CE, 2011. Cue-induced craving for marijuana in cannabis-dependent adults. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 19, 223–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004. Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: findings from a randomized multisite trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 72, 455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae-Clark AL, Carter RE, Price KL, Baker NL, Thomas S, Saladin ME, Giarla K, Nicholas K, Brady KT, 2011. Stress and cue-elicited craving and reactivity in marijuana-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology 218, 49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Binkoff JA, Abrams DB, Zwick WR, Nirenberg TD, Liepman MR, 1987. Reactivity of alcoholics and nonalcoholics to drinking cues. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 96, 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura RS, Rohsenow DJ, Binkoff JA, Monti PM, Pedraza M, Abrams DB, 1988. Relevance of cue reactivity to understanding alcohol and smoking relapse. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 97, 133–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson LD, Ravichandran C, Lundahl LH, Rodolico J, Dunlap S, Trksak GH, Lukas SE, 2011. Cue-reactivity in cannabis-dependent adolescents. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 25, 168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom BR, Levin FR, 2007. Treatment of cannabis use disorders: a review of the literature. Am. J. Addict. 16, 331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ, 1998. Conditioning factors in drug use: can they explain compulsion? J. Psychopharmacol. 12, 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Cary M, Slaymaker V, Colleran C, Blow FC, 2009. Daily rating measures of alcohol craving during an inpatient stay define subtypes of alcohol addiction that predict subsequent risk for resumption of drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 103, 131–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal P, Hyman SM, Sinha R, 2008. Craving predicts time to cocaine relapse: further validation of the Now and Brief versions of the cocaine craving questionnaire. Drug Alcohol Depend. 93, 252–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens RW, Johanson CE, 1992. Craving: consensus of status and agenda for future research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 30, 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Vahabzadeh M, Schmittner J, Lin JL, Gorelick DA, Epstein DH, 2009. Cocaine craving and use during daily life. Psychopharmacology 207, 291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MS, Thakkar V, 2009. Valproate treatment and cocaine cue reactivity in cocaine dependent individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 102, 144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MS, Palamar J, Raghavan S, Flammino F, 2007. Effects of topiramate on cue-induced cigarette craving and the response to a smoked cigarette in briefly abstinent smokers. Psychopharmacology 192, 147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins SJ, Ehrman RN, Childress AR, O’Brien CP, 1992. Using cue reactivity to screen medications for cocaine abuse: a test of amantadine hydrochloride. Addict. Behav. 17, 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins SJ, Ehrman RN, Childress AR, O’Brien CP, 1999. Comparing levels of cocaine cue reactivity in male and female outpatients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 53, 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Hutchison KE, Swift RM, Colby SM, Kaplan GB, 2000. Naltrexone’s effects on reactivity to alcohol cues among alcoholic men. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 109, 738–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Rubonis AV, Gulliver SB, Colby SM, Binkoff JA, Abrams DB, 2001. Cue exposure with coping skills training and communication skills training for alcohol dependence: 6- and 12-month outcomes. Addiction 96, 1161–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Tidey JW, Miranda R, McGeary JE, Swift RM, Hutchison KE, Sirota AD, Monti PM, 2008. Olanzapine reduces urge to smoke and nicotine withdrawal symptoms in community smokers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 16, 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, Niaura RS, Martin CS, Shadel WG, 2000. The measurement of drug craving. Addiction 95 (Suppl. 2), S189–S210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton EG, Trotman AJ, Zavahir M, Taylor RC, Heishman SJ, 2002. Determination of the reliability and validity of the Marijuana Craving Questionnaire using imagery scripts. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 10, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling RC, Dean J, Weinstein SP, Murphy J, Gottheil E, 2004. Gender differences in cue exposure reactivity and 9-month outcome. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 27, 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotts AL, Dodrill CL, Kosten TR, 2009. Opioid dependence treatment: options in pharmacotherapy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 10, 1727–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2014. Center for behavioral health statistics and quality. Treatment episode data set (TEDS): 2002–2012. In: National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. BHSIS Series S-71, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4850, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ, 1991. The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. Br. J. Addict. 86, 1467–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandrey RG, Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Liguori A, 2008. A within-subject comparison of withdrawal symptoms during abstinence from cannabis, tobacco, and both substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 92, 48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandrey R, Haney M, 2009. Pharmacotherapy for cannabis dependence: how close are we? CNS Drugs 23, 543–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandrey R, Stitzer ML, Mintzer MZ, Huestis MA, Murray JA, Lee D, 2013. The dose effects of short-term dronabinol (oral THC) maintenance in daily cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 128, 64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA, 2004. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: that was zen, this is tao. Am. Psychol. 59, 224–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfling K, Flor H, Grusser SM, 2008. Psychophysiological responses to drug-associated stimuli in chronic heavy cannabis use. Eur. J. Neurosci. 27, 976–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Zhang S, Epstein DH, Fang Y, Shi J, Qin H, Yao S, Le Foll B, Lu L, 2007. Gender and stimulus effects in cue-induced responses in abstinent heroin users. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 86, 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachary RA, 1986. Shipley Institute of Living Scale: Revised Manual. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]