Abstract

This study estimates changes in geographic access and drive times to gender clinics following legislation enacted to restrict puberty-suppressing medications and hormones for those younger than 18 years.

As of May 2023, a total of 20 states have enacted legislation, executive actions, or other policies restricting health care for transgender youths, with more than 100 bills under consideration. Access to developmentally appropriate medical and social services for transgender youths is associated with mental health benefits and decreased suicidality.1,2 As more states restrict evidence-based gender-affirming care, the distances youths and their families will need to travel are unknown. We estimated changes in geographic access and drive times to gender clinics following restrictions.

Methods

In March 2023, we conducted online searches and reviewed public directories, resource lists, news articles, and archived clinical websites to identify clinics advertising gender-affirming care for patients younger than 18 years in the contiguous 48 US states and Washington, DC. Clinics were included if they provided medical gender-affirming care, including puberty-suppressing medications and hormones. We excluded locations providing gender-affirming surgery only. Provision of gender-affirming care was verified by cross-referencing of multiple publicly available resources or by phone call. Supplement 1 details search methodology. We identified restriction states based on the presence of enacted legislation, executive actions, funding provisions, or other policies that limited access to puberty-suppressing medications and hormones for patients younger than 18 years as of May 22, 2023.

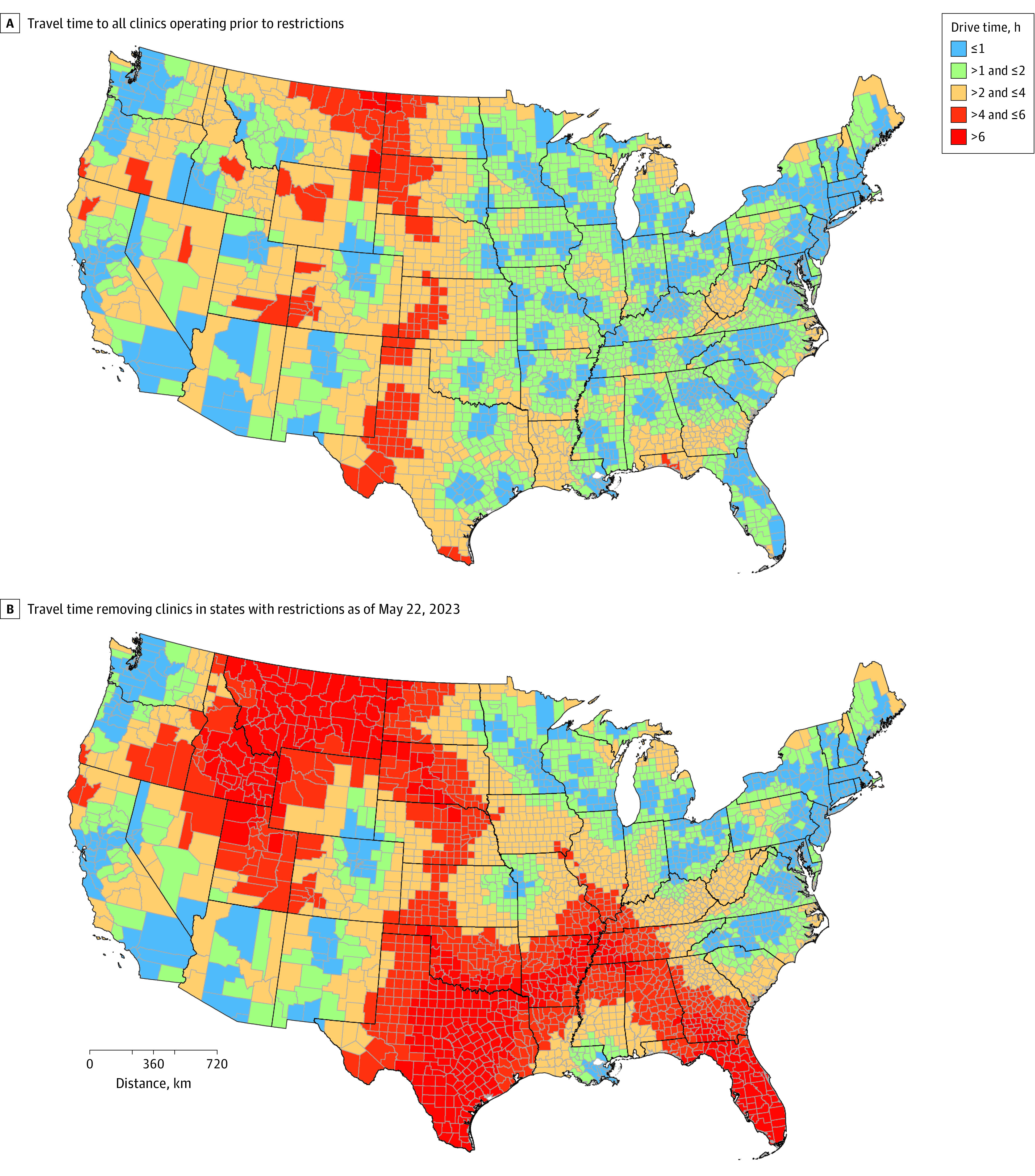

Drive times were calculated from US Census Bureau population-weighted county centroids to the nearest clinic under optimal conditions (no traffic). A repeated cross-sectional analysis3 compared drive times prior to state restrictions, during which all clinics providing gender-affirming care were considered active, and following state restrictions, removing all clinics in states with restrictions as of May 22, 2023. We calculated state-specific geographic access by weighting counties by the population of youths aged 10 to 17 years from American Community Survey data from 2016-2020. The percentage of youths living more than 1 hour and more than 4 hours away was determined prior to and after restrictions were enacted. State-specific estimates of transgender populations aged 13 to 17 years from the Williams Institute4 were used to calculate the percentage of youths affected by restrictions. Statistical testing was performed using Wilcoxon signed rank and χ2 testing. Analysis was completed in ArcGIS Pro 3.0 and SAS OnDemand; a 2-sided P < .01 defined statistical significance. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt.

Results

Of 271 gender clinics, 70 (25.8%) were considered inactive under restrictions in 20 states. An estimated 89 100 transgender youths aged 13 to 17 years lived in states that restricted gender-affirming medical care, representing 30% of US transgender youths (Table). The national median drive time to the nearest clinic was 0.51 (IQR, 0.19-1.08) hours prior to restrictions, compared with 0.99 (IQR, 0.28-4.02) hours under restrictions (P < .001) (Figure).

Table. Change in Drive Time to Nearest Clinic Before and After Gender-Affirming Care Restrictions and Population of Transgender Youthsa.

| Location | Drive time, median (IQR), h | Transgender youths aged 13-17 y, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to restrictions | Under restrictions | ||

| States without restrictions | 0.4 (0.2-0.9) | 0.4 (0.2-0.9) | 208 500 (70.1) |

| States with restrictions | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | 5.3 (3.2-7.6) | 89 100 (29.9) |

| Alabama | 1.5 (1.0-1.7) | 5.1 (4.6-5.3) | 3400 (1.1) |

| Arkansas | 0.9 (0.4-1.3) | 6.2 (4.6-6.5) | 1800 (0.6) |

| Florida | 0.5 (0.2-1.1) | 9.0 (8.0-10.5) | 16 200 (5.4) |

| Georgia | 0.6 (0.4-1.4) | 3.8 (3.3-4.3) | 8500 (2.9) |

| Idaho | 1.9 (0.1-2.8) | 5.4 (5.2-7.4) | 1000 (0.3) |

| Indiana | 0.7 (0.5-1.2) | 1.8 (1.6-2.2) | 4100 (1.4) |

| Iowa | 1.0 (0.4-1.3) | 3.1 (2.7-3.2) | 2100 (0.7) |

| Kentucky | 0.7 (0.3-1.4) | 2.1 (1.7-3.2) | 2000 (0.7) |

| Mississippi | 1.1 (0.4-1.5) | 3.0 (2.2-5.1) | 2400 (0.8) |

| Missouri | 0.3 (0.2-0.6) | 0.3 (0.2-0.6) | 2900 (1.0) |

| Montana | 2.1 (0.8-2.7) | 6.7 (6.3-8.2) | 500 (0.2) |

| Nebraska | 0.9 (0.1-1.7) | 3.1 (3.0-3.9) | 1200 (0.4) |

| North Dakota | 2.7 (0.9-4.0) | 3.5 (1.7-4.8) | 500 (0.2) |

| Oklahoma | 1.4 (0.4-1.6) | 4.8 (4.0-5.1) | 2600 (0.9) |

| South Carolina | 1.0 (0.5-1.4) | 1.8 (1.3-3.1) | 3700 (1.2) |

| South Dakota | 1.6 (0.3-4.1) | 4.1 (3.6-4.7) | 500 (0.2) |

| Tennessee | 0.7 (0.2-1.3) | 4.4 (2.9-5.6) | 3100 (1.0) |

| Texas | 0.9 (0.4-1.7) | 7.6 (5.5-8.0) | 29 800 (10.0) |

| Utah | 0.7 (0.4-0.8) | 5.7 (5.3-6.1) | 2100 (0.7) |

| West Virginia | 2.0 (1.3-2.4) | 2.2 (1.8-2.7) | 700 (0.2) |

State-specific estimates were calculated by weighting county drive times by the population of youths aged 10 to 17 years from American Community Survey data, 2016-2020. The population of transgender youths aged 13 to 17 years was determined from the Williams Institute. Restrictions include enacted legislation, executive actions, or funding provisions that limit access to puberty-suppressing medications and hormones for youths younger than 18 years as of May 22, 2023.

Figure. Drive Time to Nearest Clinic Before and After Gender-Affirming Care Restrictions.

Clinic locations were identified through online searches of publicly advertising gender-affirming care for patients younger than 18 years across 3107 US counties and Washington, DC. Drive times were calculated from population-weighted county centroids to the nearest clinic under optimal conditions (no traffic). Restrictions included enacted legislation, executive actions, or funding provisions to limit puberty-suppressing medications and hormones for youths younger than 18 years.

Compared with 27.2% prior to restrictions, an estimated 50.0% of US youths aged 10 to 17 years lived more than 1 hour from a clinic under restrictions (P < .001). Prior to restrictions, 1.4% of US youths lived more than a 1-day drive (8 hours of total drive time; 4 hours 1 way) from a clinic, increasing to 25.3% under restrictions (P < .001). The largest absolute increases in median drive times were in Florida (+8.5 hours), Texas (+6.7 hours), and Utah (+5.0 hours) (Table).

Discussion

In this study, state restrictions were associated with significantly increased estimated drive times for youths seeking gender-affirming care. With more than 1 in 4 gender clinics located in states with restrictions, it is unknown whether existing clinics may have capacity to meet the increased need of out-of-state patients. Several states continue to advance legislation that would further exacerbate geographic access, notably Louisiana and Ohio, which represent the closest clinic for neighboring states with restrictions. Increased costs and time burdens of travel may further contribute to delayed treatment, inability to access care, and worse mental health for transgender youths.5

Study limitations include the use of county-level estimates of all youths rather than transgender-specific populations and the inability to identify nonadvertising clinicians and all clinics operating prior to restrictions. Drive times to the nearest clinic may underestimate actual travel times because families may not choose the closest clinic considering other factors such as clinic capacity and waiting times. This study assumed no traffic and did not incorporate other modes of transportation. Additional barriers faced by transgender youths, including familial support, insurance coverage, financial resources, and discrimination,6 were not considered.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editor.

eMethods

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Chen D, Berona J, Chan YM, et al. Psychosocial functioning in transgender youth after 2 years of hormones. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(3):240-250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, Stepney C, Inwards-Breland DJ, Ahrens K. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rader B, Upadhyay UD, Sehgal NKR, Reis BY, Brownstein JS, Hswen Y. Estimated travel time and spatial access to abortion facilities in the US before and after the Dobbs v Jackson women’s health decision. JAMA. 2022;328(20):2041-2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.20424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herman JL, Flores AR, O’Neill KK. How Many Adults and Youth Identify as Transgender in the United States? Williams Institute; 2022. Accessed March 14, 2023. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Trans-Pop-Update-Jun-2022.pdf

- 5.Turban JL, King D, Kobe J, Reisner SL, Keuroghlian AS. Access to gender-affirming hormones during adolescence and mental health outcomes among transgender adults. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0261039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chong LSH, Kerklaan J, Clarke S, et al. Experiences and perspectives of transgender youths in accessing health care: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1159-1173. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Data Sharing Statement