Abstract

Objective

Little is known about the hospital outcomes of moderately preterm (MPT; 29 0/7–33 6/7 weeks gestational age) infants born to insulin-dependent diabetic mothers (IDDMs). We evaluated characteristics and outcomes of MPT infants born to IDDMs compared with those without IDDM (non-IDDM).

Study Design

Cohort study of infants from 18 centers included in the MPT infant database from 2012 to 2013. We compared characteristics and outcomes of infants born to IDDMs and non-IDDMs.

Results

Of 7,036 infants, 527 (7.5%) were born to IDDMs. Infants of IDDMs were larger at birth, more often received continuous positive pressure ventilation in the delivery room, and had higher risk of patent ductus arteriosus (adjusted relative risk or aRR: 1.49, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.20–1.85) and continued hospitalization at 40 weeks postmenstrual age (aRR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.18–2.05).

Conclusion

MPT infants of IDDM received more respiratory support and prolonged hospitalizations, providing further evidence of the important neonatal health consequences of maternal diabetes.

Keywords: moderate preterm, infants, diabetes, insulin

Diabetes mellitus has been estimated to affect over 18 million pregnancies worldwide each year.1–3 In 2017, an estimated 16% of women worldwide had gestational diabetes.3 The reported U.S. prevalence of hyperglycemia during pregnancy, a proxy for gestational diabetes, rose from 5.8% in 2008–2010 to 10.8% in 2017; 86% of cases represent gestational diabetes, while the remaining 14% include pregestational type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus.2,4 When dietary modifications and oral medications fail to improve glycemic control in pregnant mothers with diabetes mellitus, insulin therapy is utilized. Fifteen percent of insulin-dependent women deliver preterm (less than 37 weeks’ gestation).2,5,6 Term infants born to diabetic mothers are more often large for gestational age (LGA) and at higher risk for hypoglycemia, congenital anomalies, and hyperbilirubinemia; risks increase with worse glycemic control.7,8

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network (NRN) has reported that extremely preterm (EPT; 22–28 6/7 weeks’ gestational age) infants born to mothers using insulin that was started before pregnancy experience higher risk of sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) compared with infants of non-insulin-dependent diabetic mothers (non-IDDMs).9 While a higher risk of adverse outcomes appears clear in term and EPT infants, the impact of maternal diabetes mellitus on moderately preterm (MPT) infants (born between 29 0/7 and 33 6/7 weeks) is less known. In the United States., approximately 100,000 MPT infants are born each year (2.8% of births in 2013, ~3 times the number of infants born <29 weeks) and are at higher risk for respiratory support and prolonged hospital stays compared with term infants.10 These infants are increasing in the population of a variety of settings including level 2 nurseries. The MPT group was hospitalized for a median proportion of 27% of initial neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) hospital days as reported by the Vermont Oxford Network.11 The objective of our study was to use a multicenter, MPT infant registry to examine the maternal characteristics and infant outcomes of MPT infants born to IDDMs compared with non-IDDMs. In addition, we compared in-hospital outcomes and length of stay for infants born to mothers with insulin started before pregnancy (IBP) with infants born to mothers with insulin started during pregnancy (IDP).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

We performed a retrospective multicenter cohort study of infants included in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD NRN’s Moderate Preterm Registry. Infants 29–33 6/7 weeks’ gestation born at or admitted within the first 72 postnatal hours to one of the 18 NICHD NRN centers from January 2012 to November 2013 were included in the registry. The institutional review board at each center approved participation in the registry.10 We excluded infants missing IDDM information or transferred to another hospital prior to 36 weeks postmenstrual age. We extracted maternal and infant demographics and in-hospital outcomes for each infant until 40 weeks postmenstrual age or death, discharge, or transfer if occurring first.

Definitions

IDDMs included mothers starting insulin before or during pregnancy as recorded in the registry. Non-IDDMs included diabetic and nondiabetic mothers who did not require insulin prior to or during the pregnancy. The diabetic mothers of this group included those who were controlled by diet or oral agents. The registry did not provide information concerning oral agents or dietary methods used for glycemic control. The timing of insulin use referred to when the mother started insulin, insulin use before pregnancy, or insulin use that began during pregnancy as recorded in the registry. Prolonged rupture of membranes (PROM) was defined as rupture for >18 hours prior to delivery and maternal chorioamnionitis as documented in the maternal record. Resuscitation was defined as use of oxygen, continuous positive pressure ventilation (CPAP), positive pressure ventilation, chest compressions, or epinephrine at the time of delivery.

For in-hospital outcomes, we included major morbidities associated with prematurity including respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), NEC, sepsis, intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).10 We used surfactant administration as a marker for RDS. A PDA diagnosis included the physician’s clinical and echocardio-graphic diagnosis and/or receipt of medical or surgical treatment for PDA management. Medical treatment included Tylenol or Ibuprofen. Morbidities for specific diagnoses included: NEC (modified Bell’s stage ≥IIA), early-onset sepsis ≤72 hours of age, and late-onset sepsis (LOS; >72 hours of age) with a positive blood culture for a bacterial or fungal organism with intent to treat with antibiotics for >5 days.12 Severe IVH was defined as grade 3 or 4 by the Papile criteria.13 Cystic PVL included infants diagnosed by cranial ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging. ROP ≥ stage 3 was diagnosed by ophthalmic exam.14

Statistical Analyses

We compared demographic and clinical characteristics of infants born to IDDMs and those born to non-IDDMs using chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. Maternal demographics included age, education, race/ethnicity, number of prenatal visits, multiple births, maternal hypertension existing prior to or during pregnancy, PROM, diagnosis of chorioamnionitis (histologic and/or clinical diagnosis), and the use of antenatal steroids (completed course). Infant demographics included gestational age, growth parameters at birth including z-scores, sex, and major birth defects.15 Small gestational age (SMA) and LGA status were determined by Olsen definitions.16

For our primary analyses of IDDM infants compared with non-IDDMs, we evaluated inpatient status at 36 and 40 weeks postmenstrual age and in-hospital morbidities using robust Poisson regression models with adjustment for demographic and clinical factors (infant sex, gestational age, antenatal steroids, maternal age, maternal race/ethnicity, prenatal care, multiple births, chorioamnionitis, cesarean delivery, outborn, ponderal index at birth, and delivery room interventions) and study center as a fixed effect. Due to the similarities in gestational age distribution and anthropometrics of the infants born to mother with IBP and IDP, the two groups were combined and compared with those born to mothers without IDDM in the primary analysis. In a secondary analysis assessing variations among IBP, IDP, and non-IDDM groups, we compared categorical variables across the three groups IBP, IDP, and no IDDM, using chi-square tests and for comparing continuous variables across the three groups IBP, IDP, and no IDDM, we used the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test. If the overall p-values for comparing the three groups were significant, then pairwise comparisons were made, comparing IBP versus No IDDM, IDP versus No IDDM, and IBP versus IDP. The chi-square test was used for categorical variables and t-test was used for continuous outcomes for pairwise comparisons.

For pairwise comparisons using t-test, first we tested the equality of variances of the two groups using the F-test. If the variances were found to be significantly different, then Satterthwaite method was used and the pooled method was used for equal variances for computing the p-values from t-test.

We also evaluated composite outcomes, surfactant use at birth, sepsis, severe IVH, PVL, ROP, NEC, and PDA, each in combination with death, among each group by insulin use (IDDM and no IDDM) and within the IDDM group (IBP and IDP). p-Values <0.05 were considered significant. Our analysis was mostly exploratory, and we did not adjust for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Study Population

The MPT registry included 7,057 infants born between January 1, 2012 and November 30, 2013 (Supplementary Fig. S1). We excluded 21 infants who were either discharged before 36 weeks or were missing IDDM data. None were transferred. The IDDM group included 527 (7.5%) infants. Among the IDDM group, 56% (294/527) were born to IBP mothers and 44% (212/527) were born to IDP mothers.

Maternal Characteristics by Insulin Use

The mean (standard deviation) maternal age for IDDMs was 31 years (±5.9), compared with 28 years (±6.5, p < 0.001) for non-IDDMs. Mothers with IDDM more often had hypertension existing prior to pregnancy or chronic hypertension (31 vs. 10%, p < 0.001; Table 1). They were also more likely to have a diagnosis of chorioamnionitis (10 vs. 7%, p = 0.003) and cesarean sections compared with non-IDDMs (75 vs. 62%, p < 0.001, Table 1). Neither maternal education, PROMs, nor antenatal steroid use differed significantly between the groups (Table 1). Death within 12 postnatal hours was similar among both groups.

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics of infants born at 29 to 33 weeks’ GA in NRN centers from 2012 to 2013 by maternal receipt of insulina maternal

| Characteristics | Mother received insulin (IDDM) N = 527 | Mother did not receive insulin (no IDDM) N = 6,509 | p-Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | – | ||

| Mean (SD) | |||

| < 25 | 67/527 (13) | 21,11/6,507 (32) | <0.001 |

| 25–29 | 127/527 (24) | 1,659/6,507 (26) | 0.48 |

| 30–34 | 184/527 (35) | 1,608/6,507 (25) | <0.001 |

| 35–39 | 108/527 (21) | 825/6,507 (13) | <0.001 |

| ≥ 40 | 41/527 (8) | 304/6,507 (5) | 0.002 |

| Maternal education | – | ||

| Less than high school degree | 74/523 (14) | 966/6,474 (15) | 0.63 |

| High school - degree/partial college | 200/523 (38) | 2347/6474 (36) | 0.36 |

| College degree or more | 94/523 (18) | 1,343/6,474 (21) | 0.13 |

| Unknown education status | 155/523 (30) | 1,818/6,474 (28) | 0.45 |

| Maternal race | |||

| Black | 169 (32) | 2,059 (32) | 0.84 |

| White | 276 (52) | 3738 (57) | 0.02 |

| Other | 56 (11) | 407 (6) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 26 (5) | 3,059 (5) | 0.80 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 89/527 (17) | 914/6,503 (14) | 0.07 |

| ≥1 prenatal visit | 518/526 (99) | 6,298/6,501 (97) | 0.04 |

| Multiple birth | 125/527 (24) | 1,931/6,509 (30) | 0.004 |

| Maternal hypertension | 281/525 (54) | 2,090/6,507 (32) | <0.001 |

| Maternal hypertension existing before pregnancy or chronic hypertension | 156/510 (31) | 643/6,402 (10) | <0.001 |

| Maternal hypertension not existing before pregnancyc | 110/510 (22) | 1,342/6,402 (21) | 0.75 |

| PROM (>18 h) | 108/504 (21) | 1,159/6,089 (19) | 0.19 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 54/524 (10) | 443/6,450 (7) | 0.003 |

| Maternal antenatal steroids | 450/520 (87) | 5,506/6,455 (85) | 0.44 |

| Cesarean delivery | 397/527 (75) | 4,056/6,508 (62) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; GA, gestational age; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetic mellitus mothers; No IDDM, no insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PROM, prolonged rupture of membranes.

All data presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Comparisons by chi square, Fisher’s exact, or Student’s t-test where appropriate.

New diagnosis of hypertension while pregnant without history of disease prior to pregnancy.

When comparing maternal characteristics by timing of insulin use, IBP mothers more often had a diagnosis of hypertension (60 vs. 44%, p < 0.001), chronic hypertension (38 vs. 20%, p < 0.001), and cesarean deliveries (79 vs. 71%, p = 0.03) compared with IDP mothers (Supplementary Table S1). The IDP mothers more often had PROM (26 versus 18%, p = 0.03) and antenatal steroid use (92 vs. 83%, p = 0.004) compared with IBP mothers (Supplementary Table S1). The rate of chorioamnionitis was higher among both IBP and IDP groups (10 and 11%, respectively) when compared with non-IDDMs (7%) (Supplementary Table S1).

Infant Characteristics by Maternal Insulin Use

Most infants in the MPT cohort were >30 weeks’ gestation (Table 2). Infants born to IDDMs more often were larger in birth weight, length, and head circumference (Table 2). Infants of IDDMs were also more likely to be LGA (21 vs. 9%, p < 0.001) and receive CPAP (59 vs. 51, p < 0.001) at delivery compared with infants of non-IDDMs (Table 2). There were no significant differences in gestational age distribution, Apgar scores, ventilator support, or surfactant therapy at birth. There were slightly more infants born to IDDMs with major birth defects (11 vs. 9%, p = 0.05).

Table 2.

Infant characteristics of infants born at 29 to 33 weeks’ GA in NRN centers from 2012 to 2013 by 2 maternal receipts of insulina

| Infant characteristics | Mother received insulin (IDDM) N = 527 | Mother did not receive insulin (no IDDM) N = 6,509 | p-Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death within 12 hours | 3/527 (0.6) | 47/6,509 (0.7) | 1.00 |

| Outborn | 31/527 (6) | 589/6,509 (9) | 0.01 |

| GA (wk) | |||

| 29 | 61 (12) | 751 (12) | 0.98 |

| 30 | 78 (15) | 987 (15) | 0.82 |

| 31 | 97 (18) | 1,156 (18) | 0.71 |

| 32 | 123 (23) | 1,582 (24) | 0.62 |

| 33 | 168 (32) | 2,033 (31) | 0.76 |

| Birth weight, g | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1,824 (530) | 1,685 (410) | < 0.001 |

| < 1,000 | 19 (4) | 271 (4) | 0.54 |

| 1,000–1,500 | 131 (25) | 1,929 (30) | 0.02 |

| 1,500–2,000 | 197 (38) | 2,916 (45) | 0.001 |

| 2,000–2,500 | 130 (25) | 1,206 (19) | < 0.001 |

| > 2,500 | 49 (9) | 185 (3) | < 0.001 |

| Birth weight z-score, mean (SD) | 0.41 (1.43) | −0.05 (1.09) | < 0.001 |

| Length at birth, cm | N = 521 | N = 6,437 | |

| Mean (SD) | 42.3 (3.7) | 41.7 (3.4) | < 0.001 |

| Length z-score | 0.18 (1.16) | −0.06 (1.04) | < 0.001 |

| Head circumference at birth, cm | N = 522 | N = 6,420 | |

| Mean (SD) | 29.3 (2.3) | 29.0 (2.1) | 0.03 |

| Head circumference z-score | 0.12 (1.25) | −0.03 (1.12) | 0.008 |

| Small for GA | 52/525 (10) | 785/6,504 (12) | 0.14 |

| Large for GA | 110/525 (21) | 604/6,504 (9) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 266/526 (51) | 3,402/6,506 (52) | 0.45 |

| Apgar at 1 minute ≤3 | 100/526 (19) | 1,101/6,460 (17) | 0.25 |

| Apgar at 5 minutes ≤3 | 13/525 (3) | 203/6,464 (3) | 0.40 |

| Delivery room interventions | N = 525 | N = 6,502 | |

| Oxygen | 381/525 (73) | 4,506/6,502 (69) | 0.12 |

| Bagging and mask | 218/525 (42) | 2,686/6,500 (41) | 0.93 |

| CPAP | 312/527 (59) | 3,338/6,501 (51) | < 0.001 |

| Intubation | 82/527 (16) | 1,105/6,504 (17) | 0.40 |

| Chest compression | 6/527 (1) | 169/6,503 (3) | 0.04 |

| Epinephrine | 5/527 (1) | 77/6,503 (1) | 0.63 |

| Ventilator support | 12/495 (2) | 122/6,074 (2) | 0.53 |

| Surfactant therapy | 132/527 (25) | 1,693/6,507 (26) | 0.63 |

| Major birth defect | 59/527 (11) | 561/6,506 (9) | 0.045 |

Abbreviations: CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; GA, gestational age; IDDM, insulin–dependent diabetic mellitus mothers; No IDDM, no insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PROM, prolonged rupture of membranes.

All data presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Comparisons by chi square, Fisher’s exact, or Student’s t-test where appropriate.

Infants born to IBP mothers were more often LGA compared with those born to IDP mothers (24 vs. 16%, p = 0.03; Supplementary Table S1). There were no statistically significant differences in IBP and IDP infants for Apgar scores, delivery room interventions and major birth defects, and gestational age distribution was similar among IBP and IDP infants (Supplementary Table S1).

In-Hospital Morbidities and Growth Outcomes at 36 Weeks Postmenstrual Age

Infants born to IDDMs had a higher risk of having more than one morbidity compared with those born to mothers without IDDM (26 vs. 20%, adjusted relative risk [aRR]: 1.35, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.08–1.68, Table 3). Compared with non-IDDM infants, IDDM infants had a higher risk of a hemodynamically significant PDA (15 vs. 10%, aRR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.20–1.85), larger weights and lengths at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (p < 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively), and greater rate of being hospitalized at 40 weeks postmenstrual age (10 vs. 7%, aRR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.18–2.05, Table 3). There were no differences in medical or surgical treatment when comparing infants born to IDDM and non-IDDMs. Infants born to IDDMs had higher risk for PDA or death within 28 days (aRR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.18–1.80) compared with those born to non-IDDMs (Table 4).

Table 3.

In-hospital mortality and morbidities among infants born at 29 to 33 weeks’ GA by maternal insulin usea

| Outcome, N (%) | Mother received insulin (IDDM) N = 527 | Mother did not receive insulin (no IDDM) N = 6,509 | Adjusted RR (95% CI) for outcome IDDM vs. no IDDM |

|---|---|---|---|

| In hospital at 36 weeks | 303/486 (62) | 3,464/6,074 (57) | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) |

| Died before discharge | 12/527 (2) | 169/6,509 (3) | 0.72 (0.37–1.41) |

| Died ≤12 hoursb | 3/527 (0.6) | 47/6,509 (0.7) | 0.38 (0.05–2.76) |

| Infants who survived >12 hours | N = 524 | N = 6,462 | |

| Number of infants without morbidityc | 67/264 (25) | 831/3,130 (27) | 0.92 (0.75–1.12) |

| Number of infants with >1 morbidityc | 69/264 (26) | 634/3,131 (20) | 1.35 (1.08–1.68) |

| Respiratory | – | ||

| Received surfactant | 132/524 (25) | 1,680/6,461 (26) | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) |

| Respiratory support at 28 days of life | 83/503 (16) | 878/6,167 (14) | 1.19 (0.98–1.44) |

| Cardiovascular | – | ||

| PDA | 81/524 (15) | 668/6,458 (10) | 1.49 (1.20–1.85) |

| PDA treated medically only | 12/81(15) | 137/667(21) | 0.65 (0.40–1.04) |

| Surgery for PDAb | 5/81(6) | 32/667(5) | 1.46 (0.55–3.86) |

| PDA not treated | 64/81(79) | 498/667(67) | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) |

| Infection | |||

| NEC | 19/524 (4) | 150/6,455 (2) | 1.37 (0.82–2.28) |

| EOSb | 3/524 (0.6) | 47/6,460 (0.7) | 0.58 (0.15–2.27) |

| LOS | 13/520 (3) | 206/6,446 (3) | 0.60 (0.31–1.16) |

| Neurology | – | ||

| Early cranial sonogramd | 291/513 (57) | 3,760/6,379 (59) | – |

| Severe IVH | 7/289 (3) | 62/3728 (2) | 1.73 (0.79–3.76) |

| Late cranial sonograme | N = 304 | N = 3,867 | |

| PVL (at 28 days or 36 weeks)b | 10/303 (3) | 80/3,867 (2) | 1.74 (0.92–3.28) |

| Ophthalmology | – | ||

| ROP examinationf | 168/319 (53) | 2,125/3,502 (61) | – |

| ROP stage ≥ 3g | 0/167 (0) | 4/2121 (0.2) | – |

| Nutrition/growth | – | ||

| Measurements at 36 weeks | N = 432 | N = 5,342 | – |

| z-Score, mean (SD) | |||

| Weight, grams | N = 430 −0.59 (1.03) | N = 5,336 – 0.91 (0.77) | p-value < 0.001 |

| Length, cm | N = 396 −0.76 (1.07) | N = 5,015 – 0.88 (0.94) | p-value 0.001 |

| Head circumference, cm | N = 408 −0.59 (1.02) | N = 5,178 – 0.66 (0.90) | p-value 0.23 |

| Discharged at 36 weeks PMA | 176/522 (34) | 2,506/6,074 (41) | 0.92 (0.82–1.04) |

| Still in hospital at 40 weeks PMA | 50/481 (10) | 412/6,022 (7) | 1.55 (1.18–2.05) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EOS, early-onset sepsis; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; LOS, late-onset sepsis; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; No IDDM, no insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PMA, postmenstrual age; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; RR, relative risk.

Note: All models adjusted for study center, infant gender, gestational age at birth, antenatal steroid use, maternal age, maternal race, prenatal care, multiple births, chorioamnionitis, cesarean delivery, outborn, ponderal index at birth, and delivery room interventions (CPAP vs. other), unless mentioned otherwise.

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Model not adjusted for center because of convergence issues.

Morbidities included RDS, PDA, NEC, sepsis, severe IVH, PVL, and ROP. Infants without an ROP exam or head ultrasound were not included in the denominator.

Early cranial sonogram included infants with ultrasounds within 28 days.

Late cranial sonogram included infants with cranial sonogram within 28 days and/or closest to 36 week PMA and after 28 days.

Includes number of infants in the hospital who received ROP exam at 28 days of life.

Adjusted analysis not performed because of no data in one of the study groups.

Table 4.

In-hospital mortality and morbidities (composite outcomes) among infants born at 29 to 33 weeks’ GA by maternal IDDM

| Outcome, N (%) | IDDM, N = 527 | No IDDM, N = 6,509 | Adjusted RR (95% CI) for outcomea IDDM vs. no IDDM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surfactant or death within 3 days | 136/527 (26) | 1733/6,508 (27) | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) |

| EOS or LOS or death before discharge | 28/523 (5) | 393/6,496 (6) | 0.75 (0.48–1.16) |

| Severe IVH or death within 28 days | 18/296 (6) | 206/3,803 (5) | 1.17 (0.70–1.94) |

| PVL (at 28 days or 36 weeks) or death within 28 days | 21/310 (7) | 229/3,939 (6) | 1.16 (0.72–1.86) |

| ROP or death within 28 days | 29/183 (16) | 344/2,370 (15) | 1.23 (0.85–1.78) |

| NEC or death within 28 days | 30/527 (6) | 288/6,504 (4) | 1.18 (0.78–1.79) |

| PDA or death within 28 days | 87/527 (17) | 763/6,505 (12) | 1.46 (1.18–1.80) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EOS, early-onset sepsis; GA, gestational age; IBP, insulin before pregnancy; IDP, insulin during pregnancy; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; LOS, late-onset sepsis; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; No IDDM, no insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; RR, relative risk.

Note: All models were adjusted for study center, infant gender, gestational age at birth, antenatal steroid use, maternal age, maternal race, prenatal care, multiple births, chorioamnionitis, cesarean delivery, outborn, ponderal index at birth, and delivery room interventions (CPAP vs. other), unless mentioned otherwise.

Poisson regression models with robust variance estimators were used for adjusted analysis of categorical outcomes.

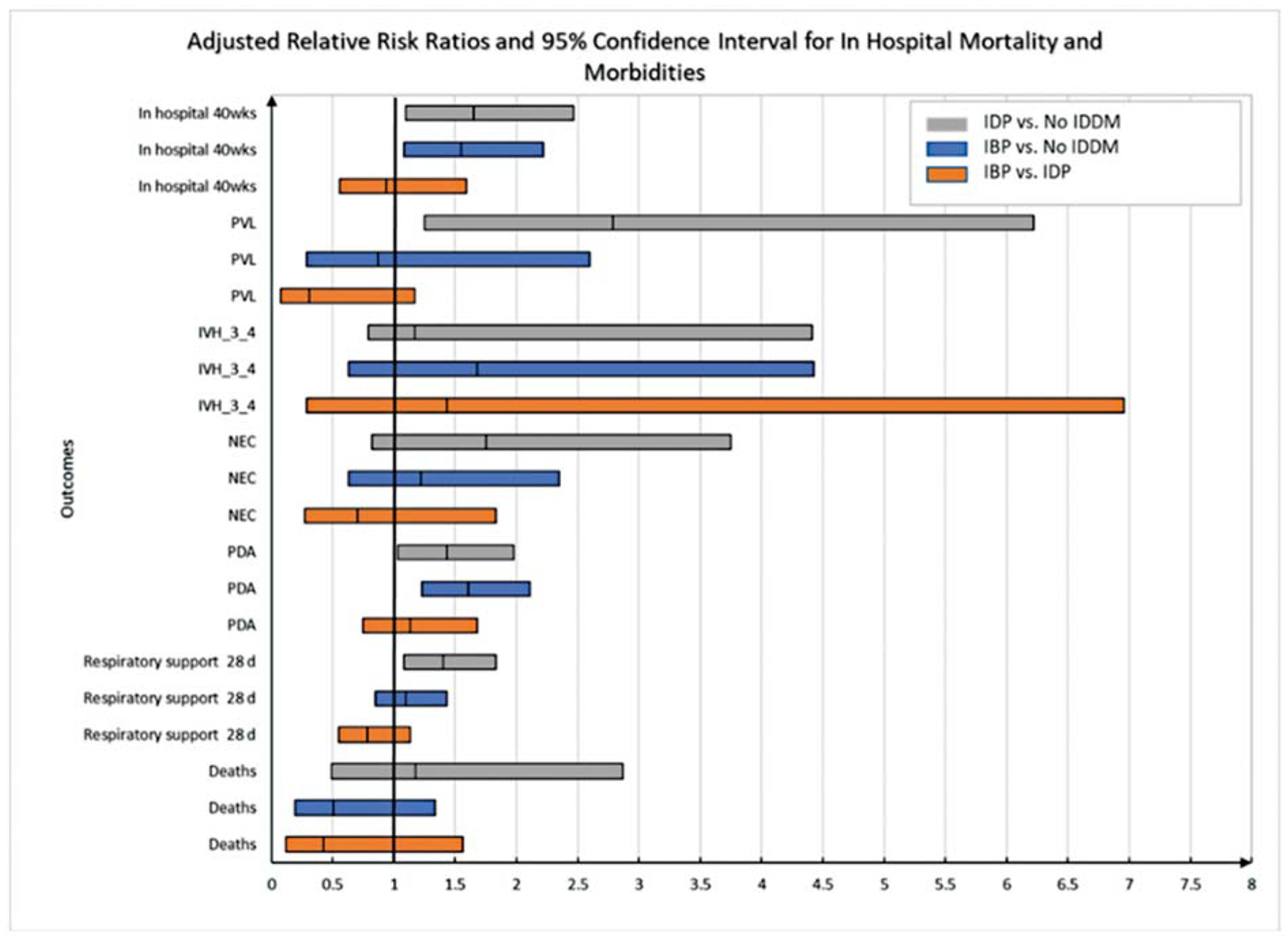

When comparing outcomes by timing of insulin use, there were no statistically significant differences in outcomes among infants born to IBP and IDP mothers (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S2). Both IBP and IDP infants had larger weights compared with non-IDDM infants (Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Adjusted relative risk of in-hospital mortality and morbidities among MPT infants by maternal insulin receipt and timing of maternal insulin use*. *Generalized linear regression models were used for adjusted analysis of continuous outcomes. Poisson regression models with robust variance estimators were used for adjusted analysis of categorical outcomes. All models were adjusted for study center, infant gender, gestational age at birth, antenatal steroid use, maternal age, and maternal race/ethnicity, unless mentioned otherwise. Model for PVL not adjusted for center because of convergence issue. IBP, insulin before pregnancy; IDP, insulin during pregnancy; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; No IDDM, no insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PMA, postmenstrual age; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia.

Differences existed when comparing each group to infants born to non-IDDMs. Infants born to IBP mothers were more likely to have PDAs (aRR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.23–2.11, Supplementary Table S2) and larger weights at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (z scores: −0.59 vs. 0.91, p < 0.001, Supplementary Table S2) compared with infants born to non-IDDMs. IDP infants had higher risk of needing respiratory support at 28 days (aRR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.08–1.83) and PVL (aRR: 2.79, 95% CI: 1.25–6.22) compared with non-IDDM infants (Supplementary Table S2). There were no significant differences among the three groups concerning risk for NEC, sepsis, or severe IVH (Supplementary Table S2). Discharge by 36 weeks postmenstrual age was similar among the IBP (34%), IDP (33%). and non-IDDM (39%) groups. At 40 weeks postmenstrual age, the percentage of infants remaining in the hospital was higher for IBP (11%) and IDP (10%) infants compared with non-IDDM infants (7%; Supplementary Table S2). There was no difference in continued hospitalization at 40 weeks between IBP and IDP infants.

For combined outcomes, infants of IBP mothers had a lower risk of the outcome of PVL or death compared with infants of IDP mothers (aRR: 0.27, 95% CI: 0.10–0.70, Supplementary Table S3), and those born to IDP mothers had higher risk than infants of non-IDDMs (aRR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.19–4.00). Infants of IBP and IDP mothers each had a higher risk of PDA or death within 28 days compared with infants of non-IDDMs (aRR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.17–2.00 and aRR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.08–2.00, respectively, Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

We found that 7.5% of MPT infants were born to IDDMs, quantifying a population that has not been well studied to this point. IDDMs experienced more morbidities and higher cesarean delivery rates than non-IDDMs. Infants born to IDDMs differed in size at birth, need for respiratory support, and length of stay compared with non-IDDM infants. We also found differences in morbidities among our cohort between IDP and IBP infants when each group was compared non-IDDM infants. More interestingly, NEC and sepsis did not significantly differ among the MPT infants when comparing infants by maternal diabetic status or timing of insulin use as previously seen in the EPT group. With a better understanding of this population size and associated morbidities, we can provide better prenatal and antenatal counsel to mothers and education to providers.

This study reviews the complications experienced by infants born to diabetic mothers by insulin use. Previous studies have reported increased complications among diabetic mothers in pregnancy including preterm birth, still births, and congenital malformations.17 Those studies did not distinguish between insulin use and other management options such as dietary modifications and oral medications. Our data provide more information concerning the risk for infant morbidity in the infants born to insulin-dependent mothers.

In the past, lack of a consistent definition of the MPT population and greater attention to the high-risk EPT population has limited understanding of the maternal and infant morbidities associated with this group. Defining our cohort by insulin use alone, to which the available study data were limited, precluded an accurate count of diabetic mothers who were treated by diet or oral hypoglycemic agents. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 20% of all births <37 weeks were MPT in 2017, and 11.8% were affected by diabetes.18 Our study included infants from the NRN’s MPT registry previously reported in 2017 by Walsh et al that included infants 29–33 6/7 weeks’ gestational age.10 Other studies have used a variety of gestational age limits to define MPT, starting as low as 28 week gestation and up to 34 6/7 week infants.11,19–21 The lack of consensus definition of MPT limits our ability to make comparisons on a consistent maternal and infant population.

Maternal Morbidities by Insulin Use and Timing

We found that chronic hypertension was more common among IDDMs and more likely among IBP mothers compared with non-IDDMs. The recent study of EPT outcomes by maternal insulin use showed similar results. In that cohort, 41% of IBP mothers had chronic hypertension prior to pregnancy compared with 9% of non-IDDMs.9 Chronic hypertension is not a rare co-morbidity among women with diabetes in pregnancy, occurring in 2 to 18% of women with pregestational diabetes.22–24 Moreover, in a study of mothers with chronic hypertension and no pregestational diabetes, 17% of those women developed gestational diabetes.23

IDDMs had higher rates of chorioamnionitis compared with non-IDDMs, suggesting increased inflammatory states among IDDMs. The associations of chorioamnionitis and other pathogens leading to sepsis in infants born to mothers with diabetes in pregnancy have been previously documented.25,26 A prospective observational study of 368 women found an association between diabetes in pregnancy and both chorioamnionitis and PROM.25 Another study that evaluated maternal colonization with Group B Streptococcus (GBS) found an association of this colonization with preexisting diabetes (aRR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.01–1.23) and increased risk of developing gestational diabetes (aRR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.11–1.32).26 The study did not review the use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications among the diabetic mothers with GBS colonization.26 Additional studies have suggested that the presence of chorioamnionitis and/or other infectious pathogens such as GBS can lead to increased inflammation that injures developing fetal organ systems.27,28 The increased risk of chorioamnionitis was observed irrespective of the timing of insulin use.

MPT Demographics and Outcomes Differed from EPT Outcomes

There was a similar distribution of SGA infants among IBP and IDP groups in our study. Our findings concerning higher rates of LGA infants may be specific to the MPT cohort versus the EPT cohort. Macrosomia is a known complication of infants born to diabetic mothers, and there is an association of in utero fetal macrosomia beyond 26 weeks in women with pregestational diabetes predicted by maternal Hgb A1C, gestational weight gain, and obesity.29 A study reviewing infants born after 28 weeks found higher rates of macrosomia in women with gestational diabetes (insulin dependent 18.5%, odds ratio [OR]: 2.1, 95% CI: 2.1–2.2 and noninsulin dependent 14.5%, OR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.6–1.7) when compared with nondiabetic mothers.30 But when comparing the use of insulin to oral medications among gestational diabetics, a Cochrane review showed using insulin did not significantly increase the risk of LGA or neonatal adiposity.8 However, the Cochrane review was limited to diabetic mothers and did not compare infant outcomes by timing of maternal insulin use. Possibly, the infants most impacted by the vascular pathologies associated with IBP were delivered early out of an abundance of caution. Vascular pathologies leading to intrauterine growth restriction are associated with higher risk of intrauterine death, as well as neonatal death and morbidity.31

Our population of MPT infants born to insulin-dependent mothers experienced similar rates of most major morbidities compared with infants of non-IDDMs. These findings are similar to the association of morbidities with maternal diabetes status observed in infants less than 1,500 g by maternal diabetes status.32 Those authors noted that insulin-dependent mothers were more likely to have more frequent antenatal care, which may be the case in our population as well, but those data were not available.

The EPT cohort, unlike the MPT infants, experienced similar rates of PDAs regardless of maternal insulin status or timing of insulin use.9 Similarly, in a cohort of 24 to 31 week infants, there were no differences in the number of treated PDAs when adjusting for maternal age, maternal hypertension, sex, birth weight, antenatal steroids, mode of delivery, and outborn status among infants of diabetic and nondiabetic mothers.32 Previous work has shown that infants of diabetic mothers are more likely to have delayed closure of the PDA among a group of term and preterm infants, but there has not been specific information on the gestational ages most at risk for this morbidity.33 Another study of LGA infants born to diabetic and nondiabetic mothers reported a delay in the fall of pulmonary arterial pressure leading to delays in the closure of the ductus.34 PDA treatments were not increased among infants of IDDMs. Similar rates of medical and surgical interventions could indicate infants of IDDM were not more clinically symptomatic than infants of non-IDDMs.

We found increased PVL on cranial imaging and longer respiratory support in infants born to mothers with IDP versus no IDDM. The potential association with higher respiratory support requirement at 28 postnatal days in those with abnormal cranial imaging was first reported in the original MPT cohort.35 Abnormal cranial imaging was associated with chorioamnionitis and lower gestational age among MPT infants, while those who received antenatal steroids and delivered via cesarean section were at lower risk.35 In our study, chorioamnionitis is unlikely to explain the association between IDP and PVL given that the rate of chorioamnionitis was similar for mothers with IDP and IBP.

NEC and sepsis did not significantly differ among the MPT infants when comparing infants by maternal diabetic status or timing of insulin use as seen in the EPT group.9,32 In the EPT cohort, there was an increased risk of NEC and LOS among infants of IBP mothers versus the non-IDDM group.9 This could be because gestational age is among the strongest associated factors with risk of NEC and postnatal sepsis, and the prevalence of each morbidity is quite low relative to the prevalence in the EPT cohort.

In-Hospital Status at 36 Weeks and 40 Weeks Postmenstrual Age

Our results suggest IDDM infants experience longer lengths of hospital stay compared with those born to non-IDDMs regardless of the timing of insulin use. Infants of mothers with IBP and IDP both remain in hospital at 40 weeks at higher rates than non-IDDM infants of similar gestational age but hospitalization rate at 40 weeks postmenstrual does not differ between IBP and IDP infants. Prolonged stay for MPT infants likely leads to higher costs. A study of 559,532 infants born in Australia reported the median (interquartile range) length of stay for the birth hospitalization among infants 28–31 and 32–33 week infants was 47 (23) and 25 (12) days, respectively, with median costs ranging from $23,455 to 62,450 USD.36 The costs estimates for U.S. born MPT infants have not yet been reported, but our results indicating longer stays for infants affected by maternal diabetes have a significant impact on NICU costs and resource utilization.

Strengths and Weaknesses

There were several strengths of our study. This was a multicenter cohort, based on previously defined gestational ages for the MPT cohort.10 The MPT cohort comprises a substantial portion of the NICU population. This is the first study to report on MPT infants by maternal diabetic status with timing of insulin use.

There were a few limitations of our study. We did not have information on the type of maternal diabetes (i.e., type 1, type 2, or gestational), obesity/body mass index status, and the method of glycemic control for diabetic mothers who were not insulin dependent such as diet controlled or oral medications. The registry did not include information about glycemic control or measures such as hemoglobin A1C. The database was not specifically designed to comprehensively describe infants of diabetic mothers; however, the information gained from this study could inform future studies concerning infants of diabetic mothers in the MPT population. The study may have been underpowered to examine the less common outcomes in MPT infants and the p-values presented did not include adjustments for multiple comparisons. Our study explored many differences between groups, but we did not make corrections for multiple comparisons, including maternal chronic hypertension, leaving the possibility of some statistical differences occurring by chance rather than true clinical differences. We also did not have follow-up data for neuro-developmental outcomes.

Conclusions

MPT infants born to IDDMs in our cohort were more likely to experience morbidities based on timing of maternal insulin use compared with non-IDDM infants. These infants also experience longer lengths of stay compared with infants born to non-insulin-dependent mothers. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effects of glycemic control both before and during pregnancy on duration of hospitalization and in-hospital morbidities in MPT infants.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Little data are available on moderate preterm infants of IDDMs.

MPT infants of IDDMs need more respiratory support.

Longer neonatal intensive care unit stays among MPT infants of IDDMs.

Disclosures

Dr. Cotten receives grant funding from the NIH (5U10 HD040492-16), is a co-investigator for SBIR NICHD, Baebies, Inc. Comprehensive, Near Patient Assessment of Severe Hypoglycemia in Newborns Using Low Blood Volume; Phase II (grant 4R44HD092154-02), and co-inventor for Cryo-Cell International, Inc. (A-013279). Ms. Saha is an employee of RTI, and a recipient of a NICHD Neonatal Research Network Grant. Dr. Walsh receives grant funding from the NICHD.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Erjavec K, Poljičanin T, Matijević R Impact of the implementation of new WHO diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus on prevalence and perinatal outcomes: a population-based study. J Pregnancy 2016;2016:2670912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSisto CL, Kim SY, Sharma AJ. Prevalence estimates of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2007–2010. Prev Chronic Dis 2014; 11:E104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federation ID. IDF Diabetes Atlas. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation;2017 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavery JA, Friedman AM, Keyes KM, Wright JD, Ananth CV. Gestational diabetes in the United States: temporal changes in prevalence rates between 1979 and 2010. BJOG 2017;124(05):804–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitanchez D, Yzydorczyk C, Simeoni U. What neonatal complications should the pediatrician be aware of in case of maternal gestational diabetes? World J Diabetes 2015;6(05):734–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsushita E, Matsuda Y, Makino Y, Sanaka M, Ohta H. Risk factors associated with preterm delivery in women with pregestational diabetes. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2008;34(05):851–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, et al. ; HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008;358(19):1991–2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown J, Grzeskowiak L, Williamson K, Downie MR, Crowther CA. Insulin for the treatment of women with gestational diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;11(11):CD012037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boghossian NS, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Outcomes of extremely preterm infants born to insulin-dependent diabetic mothers. Pediatrics 2016;137(06):e20153424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh MC, Bell EF, Kandefer S, et al. Neonatal outcomes of moderately preterm infants compared to extremely preterm infants. Pediatr Res 2017;82(02):297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards EM, Horbar JD. Variation in use by NICU types in the United States. Pediatrics 2018;142(05):e20180457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am 1986;33(01): 179–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr 1978;92 (04):529–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity revisited. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123(07): 991–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen IE, Harris CL, Lawson ML, Berseth CL. Higher protein intake improves length, not weight, z scores in preterm infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;58(04):409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics 2010;125(02):e214–e224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metzger BE, Buchanan TA. Gestational Diabetes. In: Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Menke A, Cissell MA, Eberhardt MS, Meigs JB, et al. , editors. Diabetes in America. 3rd edition. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US); 2018. Aug. CHAPTER 4. Available from: HYPERLINK “https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568009/__;!!OToaGQ!-Ap5KQZosF3c3mmFY5N-mAyOV02jsK1tRhV3ditlhRr4G6HkAUfxkgZn5pwxoPvwqn-tKvQ$”https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568009/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CDC. Natality public-use data 2007–2017. Published 2018. Accessed March 28, 2022 at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/natality-current.html

- 19.Nair J, Longendyke R, Lakshminrusimha S. Necrotizing enterocolitis in moderate preterm infants. BioMed Res Int 2018; 2018:4126245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Escobar GJMM, McCormick MC, Zupancic JA, et al. Unstudied infants: outcomes of moderately premature infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006;91 (04):F238–F244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Profit J, Zupancic JA, McCormick MC, et al. Moderately premature infants at Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program in California are discharged home earlier than their peers in Massachusetts and the United Kingdom. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006; 91(04):F245–F250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leon MG, Moussa HN, Longo M, et al. Rate of gestational diabetes mellitus and pregnancy outcomes in patients with chronic hypertension. Am J Perinatol 2016;33(08):745–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanit KE, Snowden JM, Cheng YW, Caughey AB. The impact of chronic hypertension and pregestational diabetes on pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207(04):333.e1–333.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugrue R, Zera C. Pregestational diabetes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2018;45(02):315–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Liao Q, Wang F, Li D. Association of gestational diabetes mellitus and abnormal vaginal flora with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(34):e11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards JM, Watson N, Focht C, et al. Group B Streptococcus (GBS) colonization and disease among pregnant women: a historical cohort study. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2019;2019:5430493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watterberg KL, Demers LM, Scott SM, Murphy S. Chorioamnionitis and early lung inflammation in infants in whom bronchopulmonary dysplasia develops. Pediatrics 1996;97(02): 210–215 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dammann O, Leviton A, Bartels DB, Dammann CE. Lung and brain damage in preterm newborns. Are they related? How? Why?. Biol Neonate 2004;85(04):305–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Menke A, et al. , eds. Diabetes in America. Bethesda, MD:: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US);; 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billionnet C, Mitanchez D, Weill A, et al. Gestational diabetes and adverse perinatal outcomes from 716,152 births in France in 2012. Diabetologia 2017;60(04):636–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics and the Society forMaternal-FetalMedicin. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 204: fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133(02):e97–e109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Persson M, Shah PS, Rusconi F, et al. ; International Network for Evaluating Outcomes of Neonates. Association of maternal diabetes with neonatal outcomes of very preterm and very low-birth-weight infants: an international cohort study. JAMA Pediatr 2018; 172(09):867–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seppänen MP, Ojanperä OS, Kääpä PO, Kero PO. Delayed postnatal adaptation of pulmonary hemodynamics in infants of diabetic mothers. J Pediatr 1997;131(04):545–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vela-Huerta M, Aguilera-López A, Alarcón-Santos S, Amador N, Aldana-Valenzuela C, Heredia A. Cardiopulmonary adaptation in large for gestational age infants of diabetic and nondiabetic mothers. Acta Paediatr 2007;96(09):1303–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Natarajan G, Shankaran S, Saha S, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Antecedents and outcomes of abnormal cranial imaging in moderately preterm infants. J Pediatr 2018;195:66–72.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stephens AS, Lain SJ, Roberts CL, Bowen JR, Nassar N. Survival, hospitalization, and acute-care costs of very and moderate preterm infants in the first 6 years of life: a population-based study. J Pediatr 2016;169:61.e3–68.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.