Abstract

Photosensitizers that display “unusual” emission from upper electronically excited states offer possibilities for initiating higher-energy processes than what the governing Kasha’s rule postulates. Achieving conditions for dual fluorescence from multiple states of the same species requires molecular design and conditions that favorably tune the excited-state dynamics. Herein, we switch the position of the electron-donating NMe2 group around the core of benzo[g]coumarins (BgCoum) and tune the electronic coupling and the charge-transfer character of the fluorescent excited states. For solvents with intermediate polarity, three of the four regioisomers exhibit fluorescence from two different excited states with bands that are well separated in the visible and the near-infrared spectral regions. Computational analysis, employing ab initio methods, reveals that the orientation of an ester on the pyrone ring produces two conformers responsible for the observed dual fluorescence. Studies with solid solvating media, which restricts the conformational degrees of freedom, concur with the computational findings. These results demonstrate how “seemingly inconsequential” auxiliary substituents, such as the esters on the pyrone coumarin rings, can have profound effects leading to “anti-Kasha” photophysical behavior important for molecular photonics, materials engineering, and solar-energy science.

Keywords: charge transfer, benzo[g]coumarins, dual emission, coumarins, twisted intramolecular charge-transfer state

Introduction

For decades, Kasha’s rule, along with its subsequent Vavilov’s rule, have served as fundamental guidelines in molecular photonics.1 They are corollary of the inherently fast internal conversion (IC) between electronically excited states making the deactivation of the lowest excited states with the same multiplicity the rate-limiting step.2 This photophysical behavior prevents harvesting the full scale of optical excitation energy and accessing reaction pathways originating from upper excited states.3−5 Therefore, systems that do not follow Kasha’s rule and show, for example, two fluorescence bands from excited state with different energies, i.e., dual fluorescence, present important paradigms for areas such as solar-energy science, optical imaging, and biosensing.6−9

Azulene is the “poster child” of chromophores that violate Kasha’s rule.10 The rate of radiative deactivation of its S2 state is comparable to that of S2 → S1 IC, resulting in strong S2 → S0 fluorescence.11,12 Similarly, other chromophores, such as ketocyanine dyes and sub-porphyrins can exhibit fluorescence from their S2 and S3 states.13,14

Modulating the rates of excited-state charge transfer (CT), intersystem crossing (ISC) and proton-transfer (PT)-mediated tautomerization can also produce two emissive states with different energies that undergo radiative decay with equal efficacy. Chromophores with emissive (CT) and locally excited (LE) states display dual fluorescence when the rates of CT are comparable to the rates of deactivation of the LE state.15,16 In solids, ISC from upper states can provide a means for populating states with different multiplicity and attaining dual emission encompassing fluorescence and phosphorescence bands.17,18 Excited-state PT producing multiple tautomers can similarly lead to dual fluorescence from the populations with different energy gaps between their emissive and ground states.19 Tautomerization of free-base corroles allows picosecond access to higher energies than that of their lowest excited states. Overall, excited-state isomerization that populates two local minima of emissive structures with different energies above the Franck–Condon (FC) ground states provides a plausible means for attaining dual-fluorescence behavior.20

In the context of excited-state CT and conformational dynamics that may lead to dual fluorescence, we turn our attention to aminocoumarins. Developed as strongly fluorescent and photostable laser dyes, they have become popular photoprobes for biomedical imaging.21,22 The amine and the electron-deficient pyrone ring form a donor–acceptor pair efficiently mediating ICT in the excited state and producing broad CT fluorescence with a huge Stokes’ shift.23−25 Although studied for more than a century, coumarins and π-expanded coumarins are well-known to produce emission from their low-lying CT states with no traces of dual fluorescence from upper states.

Coumarin was first isolated in 1820 from the beans of Dipteryx odorata, which gave its name.26 The first π-expanded coumarin was synthesized by von Pechmann in 1887.27 Nevertheless, this field has only catapulted to prominence over the last decade. In this short time period, multiple classes of synthesized and characterized π-expanded coumarins, including conjoined and helical coumarins, have emerged.28−38

The fluorescence of 7-aminocoumarins is one of the most intensively studied and puzzling topics in the field of photophysics of organic chromophores.39 Important early contributions by Jones40−42 revealed that substituents on and in the proximity of the amino-nitrogen atom strongly affect their emission characteristics. These reports were followed by breakthrough analysis by numerous authors43−46 with critical contributions coming from Rettig47 and Cole.48 Recently two structural motifs that retain reasonably high fluorescence quantum yields of 7-aminocoumarins in very polar solvents emerged.49−51 At the same time the work by Cole, Maciejewski, and others revealed that shifting the position of the amino group to position 6 has a profound effect on the photophysics, typically enlarging the Stokes’ shift and decreasing the fluorescence quantum yield.25,52−55

The first example of benzocoumarin possessing NMe2 group was published by Cho and co-workers in 2007.56 This benzo[h]coumarin (Figure 1) displayed remarkably strong fluorescence in water and moderate bathochromic shift of emission. In the breakthrough discovery, Ahn was the first to recognize that linear expansion of coumarin into benzo[g]coumarin while maintaining the presence of the dialkylamino group (Figure 1) leads to superb photophysical properties (i.e., large fluorescence quantum yields, reasonable Stokes’ shift, and so forth) accompanied by a redshift of the emission band to ca. 600 nm.57 Indeed, the methyl ester of 8-dimethylaminobenzo[g]coumarin has very promising properties from the point of view of bioimaging, featuring strong emission even in polar solvents.58 The subsequent systematic study reveals that further modification toward benzo[f]coumarin series has a detrimental effect on emission intensity.59 The 8-dialkylaminobenzo[g]coumarin motive has been subsequently explored by Ahn and co-workers in numerous contributions addressing, e.g., autofluorescence in deep tissue imaging58,60 and discrepancy of fluorescence properties in solutions and in cells.61 The discovery of 8-dimethylamino-benzo[g]coumarin led to numerous papers exploring this dye as next generation fluorescent probes.61−64

Figure 1.

State-of-the art in strongly polarized benzocoumarins.

Considering this wealth of knowledge, the question at hand is, can altering the position of the amine in π-expanded coumarins tune its electronic coupling with the aromatic core in order to attain dual fluorescence from different electronic states?

Herein, we report a discovery of dual fluorescence from benzo[g]coumarin (BgCoum) derivatives (Figure 1). While methyl 8-dimethylaminobenzo[g]coumarin-3-carboxylate (8-BgCoum) shows a single broad fluorescence band exhibiting pronounced solvatochromism and a large Stokes’ shift consistent with radiative decay of a CT state,65 moving the amine substituent to positions 6, 7, and 9 induces the emergence of short-wavelength emission for solvents with intermediate polarity. As important as the amine position is, to our surprise, it is the rotation of an ester substituent on the pyrone ring that defines the emergence of the dual fluorescence, as ab initio computational studies reveal. This unexpected paradigm of photoinduced dynamics makes π-expanded coumarins promising candidates for exploring initiation of intermolecular processes from upper excited states.

Results and Discussion

Molecular Design and Synthesis

Introducing a dimethylamino group (NMe2) at positions 6, 7, 8, and 9 of a benzo[g]coumarin scaffold allows examining the effects of the position of strong electron-donating substituents on the photophysics of this class of π-expanded dyes. Such alterations of the position of NMe2 varies its electronic coupling with the coumarin core and, especially, with the electron-deficient pyrone ring modified with an ethoxycarbonyl group (CO2Et). As an electron withdrawing group with Hammett constants of 0.37 and 0.45, CO2Et enhances the propensity of the pyrone ring to act as an electron acceptor.66 Nevertheless, while the Swain–Lupton (SL) field constant of CO2Et is 0.34, consistent with its electron-withdrawing property, the SW resonance constant of ethoxycarbonyl is only 0.11,67 suggesting relatively weak mesomeric effects and perturbation of the coumarin electronic transitions involving frontier orbitals with a π-character.

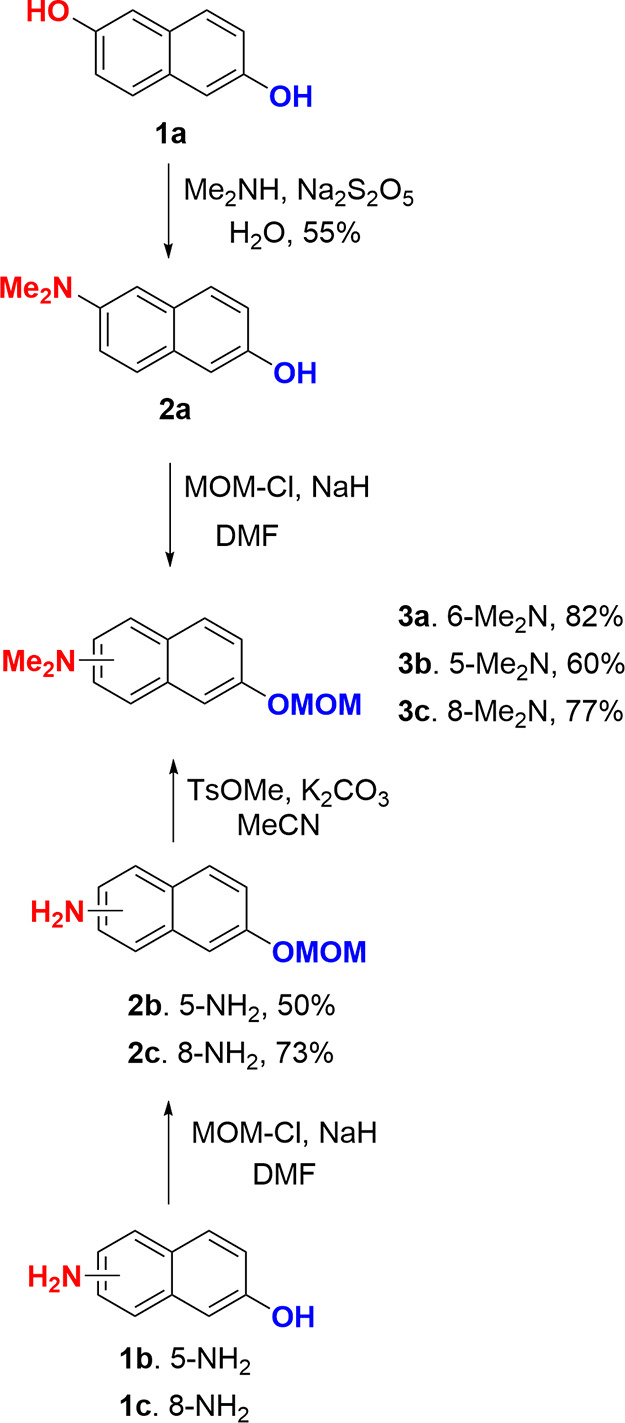

In addition to the 8-BgCoum derivative that we have already reported,65 we synthesize the new 6, 7, and 9 regioisomeric benzo[g]coumarins in four steps using a method analogous to that described in the literature.58 Monosubstitution of 2,6-dihydroxynaphthalene with dimethylamine under Bucherer reaction conditions yields compound 2a (Scheme 1). For coumarins 6-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum, we use the commercially available 5-amino-2-hydroxynaphthalene and 8-amino-2-hydroxynaphthalene as substrates (Scheme 1). Employing chloromethyl methyl ether (MOM-Cl) allows protecting the hydroxyl group to afford compounds 2b and 2c. Using the same method to protect the hydroxyl group of 2a, it is converted into the methoxymethyl ether 3a. Methylation of the amino group using methyl p-toluenesulfonate leads to compounds 3b and 3c with an overall efficiency of 50%. The use of other methylation reagents gives significantly lower yields.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 3a–c.

Ortho-formylation relative to the protected hydroxyl group of the dimethylaminonaphthalene derivatives leads to the next key intermediates 4a–c. Specifically, introducing methoxymethyl to the hydroxyl group allowed for the Snieckus-type lithiation of 3 (Scheme 2). Treating these lithioorganic derivatives with N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) as a formylation agent, and afterward with an aqueous solution of HCl, yields the aldehydes 4a–c directly, without the need to separately deprotect the hydroxyl group. The Knoevenagel condensation of diethyl malonate with 4 results in the formation of compounds 6-BgCoum, 7-BgCoum, and 9-BgCoum in yields of 59, 31, and 41%, respectively (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Dyes 6-BgCoum, 7-BgCoum, and 9-BgCoum from the Compounds 3a–c.

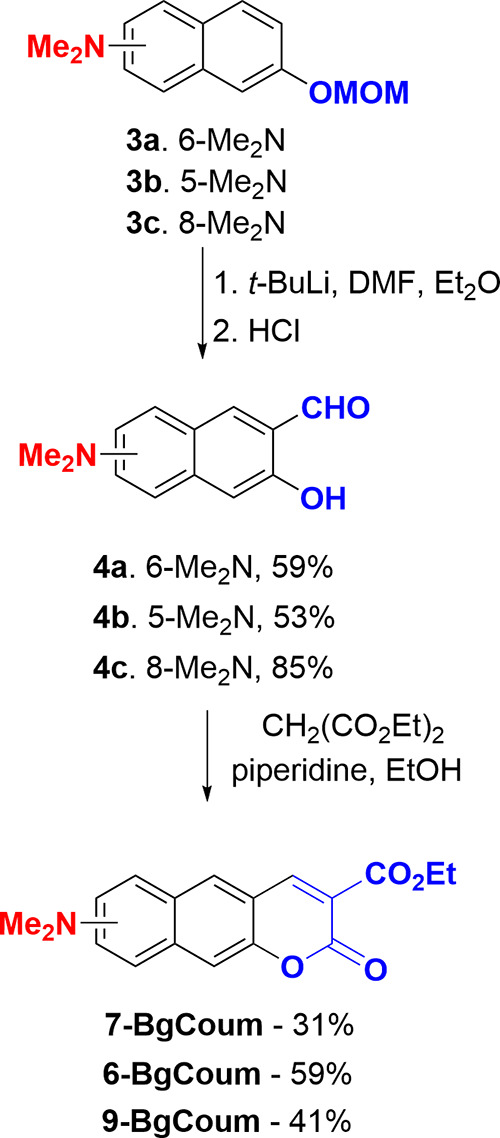

Photophysical Behavior: Unusual Dual Fluorescence

All four BgCoum NMe2 derivatives show a broad fluorescence band that manifests solvatochromic behavior (Figure 2). In addition to the bathochromic shifts of the emission, an increase in solvent polarity induces a decrease in the fluorescence quantum yields (Φf) of the BgCoum compounds (Table 1). The origin of the observed broad fluorescence band, therefore, is consistent with radiative deactivation of an excited state with a pronounced CT character, i.e., S1(CT) → S0. That is, an increase in solvent polarity stabilizes the emissive CT states of the aminocoumarins, bringing them closer to the conical intersection with the S0 state and drastically increasing the non-radiative-decay rate constants, knr (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Absorption (solid lines) and emission (dashed lines) spectra of (a) 6-BgCoum (excited at 345 nm), (b) 7-BgCoum (excited at 330 nm), (c) 8-BgCoum (excited at 340 nm),65 and (d) 9-BgCoum (excited at 317 nm).

Table 1. Photophysical Data of 6-BgCoum, 7-BgCoum, 8-BgCoum, and 9-BgCoum Measured in Solution and in Crystalline State.

| solventa | Φf (Φf SW, Φf LW) [%] | τ [ns] | kr·10–7 [s–1] | knr·10–7 [s–1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-BgCoum | ||||

| n-hexane | 50.5 | 13.4 | 3.76 | 3.69 |

| toluene | 26.1 | 6.0 | 4.33 | 12.3 |

| DCM | 3.5 | 0.9 | 12.2 | 96.7 |

| THF | 5.9 (0.2, 11.2) | 1.0 | 3.35 | 91.9 |

| ACN | 0.6 | 0.2 | 2.94 | 465.0 |

| DMSO | 0.7 | 0.19 | 3.67 | 519 |

| DMF | 0.7 | 0.24 | 2.92 | 415 |

| propyl butyrate | 0.1 (0.02, 0.91) | 2.4 | 0.38 | 41.3 |

| SOA | 5.6 (0.21, 5.8) | 7.16 | 0.81 | 13.2 |

| 7-BgCoum | ||||

| n-hexane | 14.4 | 13.1 | 1.10 | 6.54 |

| toluene | 8.9 | 9.9 | 0.82 | 9.27 |

| DCM | 0.62 (0.1, 3.9) | 1.5 | 1.38 | 63.3 |

| THF | 0.95 (0.02, 2.1) | 3.9 | 0.99 | 24.7 |

| DMSO | ||||

| DMF | ||||

| propyl butyrate | 0.54 (0.2, 0.13) | 5.27 | 0.02 | 19.0 |

| SOA | 2.1 (0.39, 0.61) | 12.8 | 0.05 | 7.8 |

| 8-BgCoum | ||||

| n-hexane | 11.0 | 0.76 | 14.0 | 118.0 |

| toluene | 98.0 | 4.2 | 23.0 | 0.3 |

| DCM | 99.9 | 4.65 | 21.5 | 0.02 |

| THF | 95.0 | 4.76 | 20.0 | 1.1 |

| ACN | 86.0 | 4.8 | 17.0 | 2.9 |

| DMSO | 73.2 | 4.18 | 17.5 | 6.4 |

| DMF | 72.9 | 4.28 | 17.0 | 6.33 |

| propyl butyrate | 34.0 | 4.38 | 7.8 | 15.1 |

| SOA | 49.2 | 4.24 | 11.6 | 12.0 |

| 9-BgCoum | ||||

| n-hexane | 8.3 | 6.3 | 1.31 | 14.5 |

| toluene | 0.90 | 1.6 | 0.55 | 62.6 |

| DCM | 0.09 (0.003, 0.11) | 2.8 | 0.27 | 35.0 |

| THF | 0.08 (0.006, 0.09) | 2.6 | 0.031 | 38.22 |

| DMSO | ||||

| DMF | ||||

| propyl butyrate | 0.03 (0.01, 0.01) | 0.70 | 0.02 | 142.8 |

| SOA | 0.80 (0.12, 1.2) | 5.85 | 0.21 | 16.9 |

Onsager polarity, fO(ε, n2), of the used solvents: hexane—0.00, toluene—0.03, sucrose octaacetate (SOA)—0.27, propyl butyrate—0.30, tetrahydrofuran (THF)—0.41, dichloromethane (DCM)—0.43, acetonitrile (ACN)—0.46, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)—0.53, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF)—0.55. fO(ε, n2) = fO(ε) – fO(n2), where fO(x) = 2(x – 1) (2x + 1)−1.

The absorption spectrum of 8-BgCoum shows a large-amplitude band around 420–450 nm, consistent with a S0 → S1(CT) transition, along with a weak ultraviolet (UV) signal originating from excitation to upper singlet state (Figure 2c). The solvatochromic response of the S0 → S1(CT) absorption, however, is not as pronounced as that of the S1(CT) → S0 emission, and the Stokes’ shift (Δν̃) increases with an increase in solvent polarity (Table 1). Enhancing the charge separation (CS), therefore, appears to follow the initial photoexcitation to the Franck–Condon (FC) CT state.

The UV transitions dominate the absorption spectra of 6-BgCoum, 7-BgCoum, and 9-BgCoum, and they do not show as strong CT bands in the 400 nm region as 8-BgCoum (Figure 2). The overlap between the natural transition orbitals (NTOs) for the S0 → S1(CT) excitation is, thus, smaller in 6-BgCoum than in 8-BgCoum, and it appears especially minute in 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum.

Most importantly, ultraviolet (UV) excitation of 6-BgCoum, 7-BgCoum, and 9-BgCoum in solvent with intermediate polarity, such as dichloromethane (DCM), tetrahydrofuran (THF), and propyl butyrate (PrBu), leads to the emergence of a new additional fluorescence band around 400 nm that is hypsochromically shifted in relevance to the CT absorption (Figure 2). In the emission spectra of the weakly fluorescent 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum, the amplitude of this newly emerged short-wavelength band is only about two-to-four times smaller than that of the broad CT band. Conversely, the 400 nm emission of 6-BgCoum in THF is barely visible on the background of the strong CT fluorescence. For 8-BgCoum, which generally exhibits the largest Φf among these four dyes, we do not observe dual fluorescence. It is noteworthy to emphasize that in polar solvents (MeOH, DMF, and DMSO), emission of 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum is below the detection limit. Fluorescence intensity of 6-BgCoum in DMF and DMSO is low but on the same level as that in ACN. On the other hand, 8-BgCoum in accordance to previous studies57,58 is strongly emissive across the solvents polarity scale (Table S1).

The photophysical properties of these novel benzo[g]coumarins ought to be compared with known benzo[f]coumarin and benzo[h]coumarin possessing NMe2 group (Figure 1).56,59 In analogy to methyl 9-(dimethylamino)-benzo[f]coumarin-2-carboxylate, 6-BgCoum has negligible emission in DMSO and in DMF, whereas its λabsmax = 360/427 nm (Tables 1, and S1). In the case of 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum, fluorescence in these solvents is below any detection limit. Also, methyl 8-(dimethylamino)-benzo[h]coumarin-3-carboxylate has similar absorption and emission data. The dual emission has not, however, been observed for these previously reported, π-expanded coumarins. Moreover, their emission in low-polarity solvents is less bathochromically shifted in comparison to that of 6-BgCoum, 7-BgCoum, and 9-BgCoum.

Overall, these π-expanded aminocoumarin fall into two subgroups based on their photophysical behavior: (1) type i dyes, which include 6- and 8-BgCoum, that show strong CT emission and high-amplitude CT-absorption bands with relatively week or completely undetected double fluorescence; and (2) type ii dyes, which include the weakly fluorescent 7- and 9-BgCoum, that show dual fluorescence with substantial contributions from the short-wavelength bands and CT absorption with quite small extinction coefficients (Figure 2).

The photostability of the four benzo[g]coumarins was studied in toluene using a xenon light source (Figure S5). All investigated dyes displayed superb stability as demonstrated by comparing with coumarin 153. In particular, 9-BgCoum displayed the highest photostability. Even prolonged exposure to a light source did not cause any noticeable changes in the absorption spectrum of 9-BgCoum.

Using UV–vis absorption allows estimating the solubility of benzo[g]coumarins in H2O. The results show that 6-BgCoum (3.5 μM) is the most water-soluble, followed by 9-BgCoum (2.5 μM), 7-BgCoum (2.5 μM), and 8-BgCoum (0.2 μM).

Electrochemical Properties and Redox Energy Gaps

Cyclic-voltammetry

(CV) analysis provides estimates of the reduction potentials of the

dyes and their oxidized forms, i.e.,  and

and  , respectively.68 For the four aminocoumarins in different solvents,

, respectively.68 For the four aminocoumarins in different solvents,  ranges between −1.6 and −1.2

V vs SCE and

ranges between −1.6 and −1.2

V vs SCE and  —between 0.8 and 1.2 V vs SCE, making

them moderately good electron acceptors and electron donors. Among

them, the type i8-BgCoum stands out

as the worst electron acceptor with

—between 0.8 and 1.2 V vs SCE, making

them moderately good electron acceptors and electron donors. Among

them, the type i8-BgCoum stands out

as the worst electron acceptor with  about 100 mV more negative than those of

the other three dyes. Similarly, the type ii7-BgCoum appears to be the best electron donor with the smallest

about 100 mV more negative than those of

the other three dyes. Similarly, the type ii7-BgCoum appears to be the best electron donor with the smallest  (see Table S3). At position 8, thus, the electron-donating amine has the strongest

effect on the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), and at position

7—on the highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO).

(see Table S3). At position 8, thus, the electron-donating amine has the strongest

effect on the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), and at position

7—on the highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO).

While it should be used with caution, Koopmans’ theorem correlates  and

and  with the LUMO and HOMO energy levels, respectively,

of the dyes.69 The redox, or electrochemical,

energy gaps, εEC = F

with the LUMO and HOMO energy levels, respectively,

of the dyes.69 The redox, or electrochemical,

energy gaps, εEC = F , of the four π-expanded aminocoumarins

range between 2.2 and 2.5 eV, corresponding to about 500 to 560 nm,

which is between the CT absorption and emission bands (see Figure S9 in the Supporting Information). That

is, εEC of the four aminocoumarins is similar to

their zero-to-zero energy, ε00, corresponding to

the optical HOMO–LUMO gaps. Therefore, the S0 →

S1(CT) and S1(CT) →

S0 radiative transitions involve predominantly the HOMOs

and the LUMOs of these dyes. Since ε00 is not much

smaller than εEC, the electron–hole electrostatic

interactions in the emissive CT do not provide significant stabilization,

which concurs with a large extent of CS.

, of the four π-expanded aminocoumarins

range between 2.2 and 2.5 eV, corresponding to about 500 to 560 nm,

which is between the CT absorption and emission bands (see Figure S9 in the Supporting Information). That

is, εEC of the four aminocoumarins is similar to

their zero-to-zero energy, ε00, corresponding to

the optical HOMO–LUMO gaps. Therefore, the S0 →

S1(CT) and S1(CT) →

S0 radiative transitions involve predominantly the HOMOs

and the LUMOs of these dyes. Since ε00 is not much

smaller than εEC, the electron–hole electrostatic

interactions in the emissive CT do not provide significant stabilization,

which concurs with a large extent of CS.

Computational Analysis: How Important is the Ester Group?

To elucidate the origin of the dual fluorescence and the nature of the excited states responsible for the short-wavelength emission bands, we resort to ab initio calculations of the four aminocoumarins, implemented at the MP2/ADC(2)/cc-pVDZ level of theory using the Turbomole 7.3 software package.70−75 It is advantageous for the computational studies to truncate the alkyl chain of the ester substituent to a methyl. In addition to the gas-phase studies, employing the conductor-like screening model (COSMO) allows us to introduce DCM as a solvating medium.76

Ground-state optimizations in the gas phase leads to the emergence of two distinct conformers of the BgCoum structures with different orientations of the esters attached to their pyrone rings in position 3 (Figure 1): (1) syn, with the C=O carbonyl bonds of the ester and the lactone pointing in the same direction, and (2) anti, with the ester and lactone C=O bonds oriented in the opposite directions (Figure 3). Electronic conjugation between the ester and the aromatic ring appears to warrant a preference for planar conformations.

Figure 3.

Ester-defined syn and anti conformers.

The syn conformers are overall more stable than the anti ones, precluding the latter from always providing detectable contributions to the ground-state optical absorption spectra. In the anti structures, the ester methyl crowds the carbonyl oxygen of the lactone. Since the methyl hydrogens are not acidic enough, this spatial proximity should not lead to hydrogen bonding but rather to steric hindrance that destabilizes the anti geometries. In the gas phase, the ground-state energy levels of the anti conformers are higher than those of the syn ones (Figure 4a,c,e,g). Introducing DCM as a solvating medium decreases this energy difference (Figure 4), which still leads to negligibly small equilibrium population of anti-6-BgCoum and anti-7-BgCoum in DCM, amounting to only about 0.003% at room temperature (Figure 4b,d). Conversely, the S0 populations of the syn and anti conformers of 8-BgCoum in DCM are practically equal (Figure 4f), and that of anti-9-BgCoum in DCM amounts to 12% (Figure 4h). These trends suggest that for 6-BgCoum and 7-BgCoum, showing dual fluorescence, the excited-state dynamics appears to originate from photoexcitation of only their anti conformers.77 Nevertheless, 7-BgCoum in DCM displays a short-wavelength fluorescence band (Figure 2b) that ought to originate from its syn conformer. A possible transition from the S2 state of the syn conformer to the S1 state of the anti one can account for the observation. Such estimates of conformer populations extracted from calculated energies of their ground-state structures, however, warrant caution because the inherent error of these computational methods can exceed 0.2 eV. This uncertainty offers an alternative explanation, i.e., the energy differences between the anti syn conformers of 7-BgCoum can very well be significantly smaller than 10kBT as the computational results show.

Figure 4.

Jablonski energy diagram for 6-BgCoum, 7-BgCoum, 8-BgCoum, and 9-BgCoum planar Cs structures and respective Sn–S0 density difference maps computed at MP2/ADC(2)/cc-pVDZ level of theory. Solid lines represent vertical excitation/emission energies of a given state computed at the respective ground/excited state minimum. The dashed black line represents vertical energy of the ground state computed at the optimized geometry of the respective compound. Numbers denote relevant energy in eV.

Implementing vertical excitations on 8-BgCoum structures in the gas phase and DCM reveals allowed S0 → S1(FC) transitions with oscillator strengths, f, exceeding 0.5 and similar energies for the two conformers (Figure 4e,f), which is consistent with the large single absorption band observed between 400 and 500 nm (Figure 2c). The relaxation of the S1(FC) state of the low-energy syn conformer leads to breaking of the C–O bond of the lactone and opening of the pyrone ring (Figure 4e,f). Coumarins are prone to such a ring-opening photoreaction, which provides a pathway for non-radiative decay competing with the radiative deactivation. The pyrone ring in unsubstituted coumarin is the most susceptible to this photoreaction according to calculations and spectroscopic evidence.78

Introducing DCM solvation medium does not prevent the ring opening of the excited-state syn-8-BgCoum. Nevertheless, the solvation substantially stabilizes the relaxed anti-8-BgCoum S1 structure which, with an electric dipole moment μ of 32 D, has a substantial CT character. This polarity-induced drop of the energy of the S1(CT) state of anti-8-BgCoum below that of syn-8-BgCoum S1 state opens pathways for preventing the ring-opening reaction by syn-to-anti rotation of the ester group in the S1 manifold.

These computational finding are in an excellent agreement with the spectroscopic results. For n-hexane, offering solvating conditions close to those of the “non-polar” gas phase, the relatively small Φf of 8-BgCoum (Φf ≈ 0.1, Table 1) is consistent with an efficient ring-opening pathway responsible for the fluorescence quenching. Even a slight increase in solvent polarity, decreases knr by 3 orders of magnitude resulting in quantitative Φf (Table 1). A further increase in medium polarity lowers the energy of the highly polarized S1(CT) state resulting in the observed bathochromic shifts in the fluorescence of 8-BgCoum. This polarity-induced drop of the S1(CT) energy brings it close to that of the ground state and opens efficient non-radiative IC pathways via back CT, which is consistent with the observed decrease in Φf for polar solvents. In order to evaluate if the replacement of methyl group with other substituents can alter ring-opening pathway responsible for fluorescence quenching, we computed analogs of 8-BgCoum possessing alternative ester groups (see Supporting Information). It turned out the same trend is also predicted for ethyl or benzyl esters for which only anti-8-BgCoum are expected to be emissive.

Computationally, the other type i dye, 6-BgCoum, shows similar behavior to that of 8-BgCoum. For the syn-6-BgCoum, the oscillator strength of the S0 → S1 transition is about two-to-four times smaller than that for the S0 → S2 one (Figure 4a,b). This finding is consistent with its absorption spectra of 6-BgCoum where the UV features dominate, showing larger amplitudes than the band at around 400 nm that extends into the visible region (Figure 2a). The transitions from the ground to the S1(FC) states for both conformers lead to doubling their dipoles, which further increase upon relaxation to the emissive S1(CT) structures. Upon relaxation of their S1(FC) states, however, neither of the 6-BgCoum conformers undergoes ring opening. Instead, the relaxed S1(CT) states of 6-BgCoum are prone to radiative deactivation to S0 with f > 0.1 and similar transition energies for the syn and anti conformers. Furthermore, the energies of the vertical S1(CT) → S0(FC) transitions substantially decrease with DCM solvation (Figure 4b). These computational results are consistent with the experimentally observed single-fluorescence band of 6-BgCoum that exhibits a pronounced solvatochromism (Figure 2a). Our computational findings, however, do not preclude the possibility of solvents, such as THF and PrBu, to induce different S1(CT) → S0(FC) transition energies for the syn and anti conformers, resulting in the observed dual fluorescence of 6-BgCoum in such media (Figure 2a).

The two type ii dyes, 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum, show quite weak S0 → S1(FC) vertical transitions with f between 0.01 and 0.05 (Figure 4c,d,g,h), which is consistent with the immensely small amplitudes observed for the 400 nm bands in their absorption spectra (Figure 2). That is, S0 → S2(FC) and S0 → S3(FC) transitions dominate the absorption spectra of 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum (Figures 2a,d and 4c,d,g,h). In the gas phase, each of these two dyes show only a single radiative transition, corresponding to a single fluorescence band for non-polar solvents: (1) from the S1(CT) → S0(FC) of syn-7-BgCoum, because the S1(CT) state of anti-7-BgCoum is energetically unaccusable; and (2) from the S1(CT) → S0(FC) of anti-9-BgCoum, because the S1 state of syn-9-BgCoum undergoes ring opening (Figure 4c,g).

Introducing DCM solvation to 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum stabilizes their S1(CT) states and makes the energies of the S1(CT) → S0(FC) transitions substantially different for the syn and anti structures. The energy gap between the S1(CT) and S0(FC) states of the syn-7-BgCoum is smaller than that of the anti-BgCoum (Figure 4d). Although the ground-state population of the anti-7-BgCoum appear to be negligibly small, excited-state syn–anti transformation allows access to the antiS1(CT) state from the syn manifold. For the 9-BgCoum, on the other hand, the S1(CT) → S0(FC) transition energy of the anti conformer is smaller than that of the syn. These computational results for the type ii dyes in DCM agree well with the observed double fluorescence that they produce.

Overall, the type ii dyes, 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum, are weakly fluorescent, as apparent from the small Φf and kf values obtained for them from steady-state and time-resolved spectroscopy studies (Table 1). Consistently, the calculated oscillator strengths for the radiative–deactivation transitions of 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum (with and without solvation) are relatively small, i.e., the values of f range between 0.03 and 0.07 (Figure 4c,d,g,h). Indeed, the rate of radiative deactivation of the higher energy conformer has to be comparable to the rate of transitions between the syn and anti structures for the double fluorescence to be detectable.

Examining the NTOs for the S1(CT) → S0(FC) transitions reveals that for the type i dyes the electron and the hole orbitals extend over the NMe2 substituent. For the type ii dyes, however, only the hole has distribution over NMe2 and the electron does not (Figures 5, and S14). Hence, enhancing the CS between the amine and the coumarin rings for the type iiBgCoum derivatives decreases f, kf, and Φf.

Figure 5.

Natural transition orbitals (NTOs) for the radiative S1→S0 deactivation of the anti and syn conformers of the four benzo[g]coumarins, obtained from the optimized S1 excited state computed at ADC(2)/cc-pVDZ level of theory.

Overall, the position of the amine, changing its electronic coupling with the coumarin rings, governs the fluorescence efficiency of the π-expanded aminocoumarins. Conversely, the conformational degrees of freedom of the ester substituent on the pyrone ring govern the formation of multiple populations of emissive CT excited states responsible for the observed dual fluorescence.

Even though the quantum yields of the short-wavelength fluorescence, ΦfSW, are small (Table 1), the detectable emission from the upper excited states implies that they live long enough to drive useful processes such as charge transfer and energy transfer. The estimated radiative-decay rate constants, kr, hardly exceeds 107 s–1 for the regioisomers that manifest dual emission. The oscillator strengths for the S1 → S0 transitions are relatively small and similar for the syn- and anti-conformers of each compound (Table 1, Figure 3). These considerations suggest sub-nanosecond non-radiative deactivation of the conformers with higher lying S1 states, rendering them feasible for driving picosecond reactions efficiently.

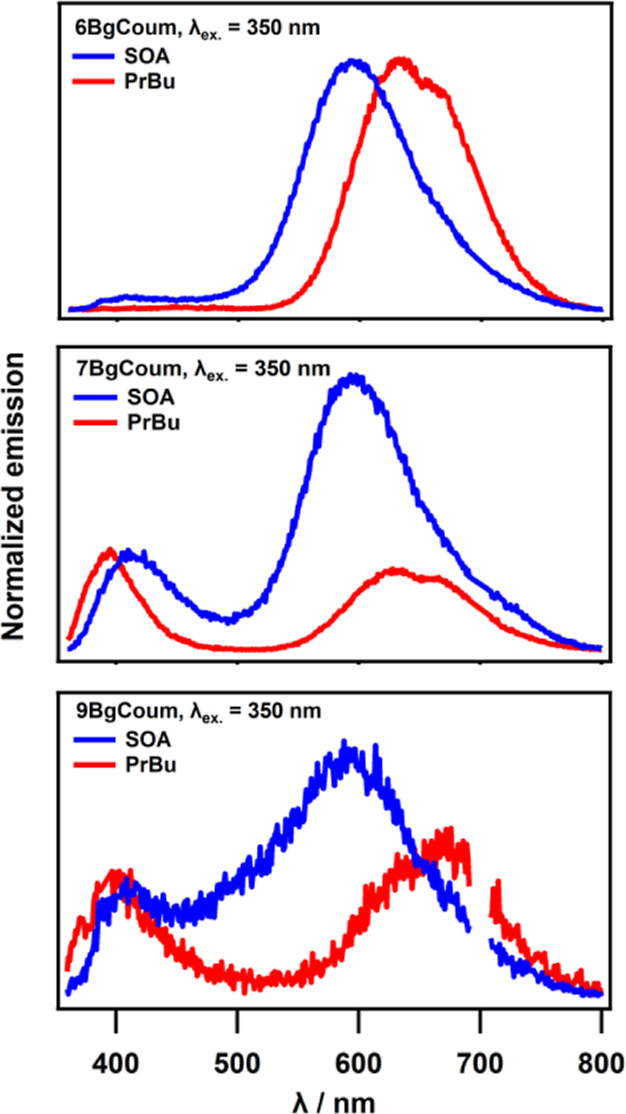

Effects of Rigidity of the Solvating Micro Environment

To elucidate which photoinduced transitions depend on large-ampliated conformational changes, we examine the effects of the rigidity of the solvating media on the dye photophysics. Sucrose octaacetate (SOA) forms transparent glass at room temperature making it a good choice as a solid solvent for optical spectroscopy tests.15,79 The polarity of SOA is similar to that of PrBu, which induces double fluorescence as a solvent of 6-, 7-, and 9-BgCoum (Figure 6, Table 1).

Figure 6.

Emission spectra for 6-BgCoum, 7 BgCoum, and 9-BgCoum in liquid propyl butyrate (PrBu) and solid sucrose octaacetate (SOA). Samples were excited at 350 nm in both media. A few crystals of compounds were dissolved in SOA while it was heating and then cooled down to obtain solid sample with appropriate isomer.

Transferring these dyes from the liquid PrBu to the solid SOA medium enhances the quantum yields not only of their principal long-wavelength fluorescence, ϕf(LW), but also of the short-wavelength emission, ϕf(SW). Twisting the dimethylamine substituents away from the plane of the aromatic ring decreases the NTO overlap and the rates of radiative deactivation. Therefore, the SOA-induced enhancement of ϕf(LW) and ϕf(SW) can originate from suppressing the NMe2 dihedral rotation around its bond with the aromatic ring. Suppressing the rotation of the ester substituent in the solid medium presents another cause for the observed increase in ϕf(SW), but not in ϕf(LW), because transitions between the anti and syn conformers provide a non-radiative pathway for the decay of the upper emissive CT state.

The photophysical characteristics 8-BgCoum, i.e., Φf, τ, kf, and knr, are quite similar for SOA and PrBu (Table 1). The SOA-induced suppression of the NMe2 twist should enhance kf. The prevention of the ester rotation and the syn-to-anti transition in the solid SOA, on the other hand, should leave the ring opening as the only pathway of deactivation resulting in substantial fluorescence quenching, which is not what the experimental results show. The rigid solvating medium, however, can also affect the efficiency of the ring opening and prevent the breaking of the lactone bond, which opens a pathway of radiative deactivation of the syn conformer responsible for the observed fluorescence of 8-BgCoum in SOA (Figure S4e).

For 6-BgCoum, on the other hand, SOA enhances ϕf(SW) by an order of magnitude and ϕf(LW) by a factor of 5 and decreases knr of the lower emissive CT state by a factor of 4 (Table 1). The effects of SOA on the photophysics of 7-BgCoum are comparable to those on 6-BgCoum (Table 1). Therefore, the dihedral rotation of NMe2 and the ester appear to play a key role in the excited-state dynamics of 6-BgCoum and 7-BgCoum.

The effects of the solid medium are the most pronounced for the weakly fluorescent 9-BgCoum where the enhancement of ϕf(SW) and ϕf(LW) exceed an order of magnitude (Table 1). That is, large-amplitude conformational changes contribute significantly to the non-radiative deactivation of 9-BgCoum in liquid solvents.

The observed short-wavelength fluorescence of 7-BgCoum for SOA appears to contradict the computational findings. The energy level of the anti conformer is more than 10kBT above that of the syn one for room temperature (Figure 4d). Therefore, the photophysical phenomena should originate from excitation of syn-7-BgCoum, which dominates the ground-state population. The solid SOA medium precludes any syn to anti conformational transitions within the short lifetimes of the excited states of 7-BgCoum. Indeed, the calculations are not for SOA solvent. Nevertheless, the results for the gas phase and for DCM are quite similar and SOA is less polar than DCM. Hence, it is safe to assume that the results for the S0 energies in SOA should be similar to those in DCM and in the gas phase. Another consideration involves the preparation of the SOA samples that require melting of the medium at about 90 °C, which increases kBT, but only by about 6 meV, which would hardly affect the change the populations with energy differences exceeding 0.2 eV. Based on these considerations, recalling that the inherent error of the employed ab initio methodology can exceed 0.2 eV, it is safe to assume that the calculated energy difference between the anti and syn ground states is considerably less than 0.26 eV.

Solid-State Photophysics

In addition to the restrictive nature of solid media, excitonic coupling plays an important role when the dyes are packed together in crystals. In the solid state, each of the four dyes shows a single fluorescence band with Φf comparable to that for toluene (Table 2, Figure 7). Specifically, 7-BgCoum exhibits the smallest Φf among the four dyes, and 6-BgCoum—the highest, which is similar to their behavior in liquid solvents (Table 1).

Table 2. Quantum Yield of Fluorescence of benzo[g]coumarin Isomers in Powder.

| cmpd | λemmax [nm] | Φf [%] |

|---|---|---|

| 6BgCoum | 625 | 26.0 |

| 7BgCoum | 668 | 4.0 |

| 8BgCoum | 676 | 16.0 |

| 9BgCoum | 668 | 0.83 |

Figure 7.

Emission spectra of all regioisomers of benzo[g]coumarins in solid-state. Powder samples were excited at 320 nm (except of 9BgCoum—λex = 400 nm).

The relatively large Φf values that we obtain for the powder samples are consistent with the rigidity of the crystal packing, along with the inherently low polarity of the solid media because of the elimination of the orientational polarization. This polarity decrease in the solid state is consistent with the hypsochromically shifted emission of the powder samples in comparison with their fluorescence in liquid solutions. For example, 6-BgCoum in acetonitrile shows an emission maximum at 755 nm, while in the solid-state, it is at 625 nm (Tables 1 and 2). The same is the case for 7-BgCoum, i.e., λem(max) = 700 nm for THF, and λem(max) = 668 nm for solid state.

It is important to keep in mind that the crystal packing does not necessarily represent the conformational-equilibrium preference in solution phase. While the crystals of 9-BgCoum contain its syn conformer reflecting the liquid-phase thermodynamics, the crystals of 6-BgCoum comprise its anti conformer (Figure 8). The ethyl substituent of the anti-6-BgCoum in the crystals, however, points away from the lactone carbonyl oxygen avoiding steric hindrance, which is different from what the computational results show for the gas phase and the DCM medium. Overall, the crystals of each of the compounds contain a single conformer, precluding the possibility for dual fluorescence from these solid-state samples, which concurs with the observed emission spectra. This finding further confirms that the observed dual fluorescence for solvents with intermediate polarity originates from populations of conformers with different S1(CT) → S0(FC) transition energies.

Figure 8.

Structures of (a) 6-BgCoum and (b) 9-BgCoum from single crystal X-ray diffraction measurement, representing conformation of CO2Et group and non-planarity of NMe2 group (CCDC 2253992–2253995).

In addition to the increased rigidity and the decreased polarity of the solvating media in solid state, along with the “conformational purity,” the crystalline packing provides conditions for intermolecular excitonic coupling that affects the observed spectral features. As previously reported for the parent compound 7-BgCoum, stacking these molecules in the head-to-tail arrangements produces aggregates with overall Ci symmetry.65 The excitonic-coupling (Davydov) splitting for dimer models of such aggregates is estimated from the S0 → S1 and S0 → S2 vibrationless bands. For 7-BgCoum and 9-BgCoum, the excitonic coupling is 0.5 and 0.3 eV, respectively, suggesting a larger stabilization of the 1Ag state for these compounds. This state has a vanishing transition dipole moment to the ground state due to symmetry rules. Thus, for these dimers the lowest absorbing/emitting state is the 1Au one, with low oscillator strength (less than 0.03). For 6-BgCoum, however, the excitonic coupling is estimated to be small, and the emission from S2 (1Au) is expected at about 2.0 eV (f ≈ 0.2). This finding may correlate to the intense emission band around 700 nm observed experimentally for this benzo[g]coumarin. In contrast to the type i dyes in crystalline state, therefore, the type iiBgCoum derivatives appear to show strong excitonic coupling.

Conclusions

With the recent increase in chromophores showing “anti-Kasha” behavior, we show that conformers involving auxiliary substituents, such as ester groups on the pyrone rings of π-expanded aminocoumarins, can play a defining role in producing long-lived populations of excited states with different energy levels. For the observed dual fluorescence, it is, indeed, crucially important for the rates of the transitions between the two emissive excited states to be comparable to the rates of radiative deactivation of the upper of these two states. Varying solvent polarity and viscosity allows achieving such conditions that set paradigms for the pursuit of photosensitizers that effectively drive reactions from high-energy electronically excited states.

Methods

Synthesis

All reported NMR spectra (1H NMR and 13C NMR) were recorded on Varian 500 or 600 MHz and Bruker 500 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ; ppm) were determined with TMS as the internal reference, J values are presented in Hz. Mass analyses in high resolution (HRMS) were obtained via electron ionization (EI) or electrospray ionization (ESI) source and a EBE double focusing geometry mass analyzer. Chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh) and thin layer chromatography was performed on TLC plates (Merck, silica gel 60 F254).

General Procedure for the Preparation of BgCoums from Aldehydes

Diethyl malonate (245 μL, 1.2 equiv, 1.56 mmol) was added dropwise via a syringe to a vigorously stirred solution of 4 (280 mg, 1.3 mmol) in EtOH (5 mL). To the resulting mixture was added a catalytic amount of piperidine (20 μL) and the reaction was stirred at reflux for 4 h. After cooling to an ambient temperature, the solid was filtrated and washed with cold EtOH to afford the corresponding product as a powder.

Steady State Optical Spectroscopy

Spectroscopic grade solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as obtained. For optical studies, solutions of molecules at low concentrations, about few micromoles per liter, were used to avoid dimerization or reabsorption effects. All absorption and fluorescence spectra were taken at room temperature. Steady-state absorption spectra are recorded in a transmission mode using Shimadzu UV-3600i Plus (Japan) and JASCO V-670 (Tokyo, Japan) spectrophotometers. Fluorescence spectra were recorded with the FS5 (Edinburgh Instruments, Edinburgh, UK), the FluoroLog-3 (Horiba-Jobin-Yvon, Edison, NJ, USA) spectrofluorometers, and the FLS 1000 Edinburgh Instruments (Edinburgh, UK) with integrating sphere and corrected for the spectral response sensitivity of the photodetector. The FluoroLog-3, which is equipped with a pulsed diode laser (λ = 406 nm, 200 ps pulse full width at half maximum, FWHM) and a TBX detector, was also employed for time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) measurements.

Computational Studies

Transition energy (ΔE), oscillator strength (f), dipole moment (μ), leading electronic configurations, relevant molecular orbitals of syn, and anti-conformations of 6-BgCoum to 9-BgCoum computed with ADC(2)/cc-pVDZ method at the ground state MP2 equilibrium. Solvent effects were considered within the COSMO approximation using dichloromethane (DCM) as solvent.

Remaining detailed methods are found in the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

The work was financially supported by the Polish National Science Center, Poland (HARMONIA 2018/30/M/ST5/00460 and OPUS 2016/23/B/ST5/03322), the Foundation for Polish Science (TEAM POIR.04.04.00-00-3CF4/16-00), the USA National Science Foundation (grant numbers CHE 1800602 and CHE 2154609), and the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (grant number 60651-ND4). This article is part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreements no. 101007804 (Micro4Nano) and no. 860762 (MSC ITN CHAIR). This research was supported in part by PL-Grid Infrastructure. We thank David C.Young for amending the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CT

charge transfer

- ISC

intersystem crossing

- FC

Franck–Condon

- SOA

sucrose octaacetate.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacsau.3c00169.

Synthetic procedures, 1H and 13C NMR spectra, photophysical, electrochemical, theoretical, and crystallographic data (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. CRediT: Kamil Szychta investigation, visualization, writing-original draft; Beata Koszarna supervision, writing-review & editing; Marzena Banasiewicz investigation, visualization, writing-original draft; Andrzej L. Sobolewski supervision, writing-review & editing; Omar O’Mari investigation; John A. Clark investigation; Valentine I. Vullev supervision, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing; Cristina Aparecida Barboza investigation, software, visualization, writing-original draft; Daniel T. Gryko conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kasha M. Characterization of Electronic Transitions in Complex Molecules. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1950, 9, 14–19. 10.1039/DF9500900014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz M. G. Modern Molecular Photochemistry of Organic Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8524. 10.1021/ja1036176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tykwinski R. R.; Guldi D. M. Singlet Fission. ChemPhotoChem 2021, 5, 392. 10.1002/cptc.202100053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich T.; Munz D.; Guldi D. M. Unconventional Singlet Fission Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3485–3518. 10.1039/d0cs01433h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldacchino A. J.; Collins M. I.; Nielsen M. P.; Schmidt T. W.; McCamey D. R.; Tayebjee M. J. Y. Singlet Fission Photovoltaics: Progress and Promising Pathways. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2022, 3, 021304. 10.1063/5.0080250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y.; An Z.; Liu H.; Yang B.; Zhang Y. Excitation-Dependent Multicolour Luminescence of Organic Materials: Internal Mechanism and Potential Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 62, e202214483 10.1002/anie.202214483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X.; Feng L.; Cao S.; Wang J.; Niu G. Donor-Acceptor-Acceptor-Conjugated Dual-State Emissive Acrylonitriles: Investigating the Effect of Acceptor Unit Order and Biological Imaging. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 8305–8309. 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c03274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F.; Zhu L.; Li M.; Song Y.; Sun M.; Zhao D.; Zhang J. Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Material: An Emerging Class of Metal-Free Luminophores for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2102970. 10.1002/advs.202102970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Kwon J. E.; Kim S. H.; Seo J.; Chung K.; Park S. Y.; Jang D. J.; Medina B. M.; Gierschner J.; Park S. Y. A White-Light-Emitting Molecule: Frustrated Energy Transfer between Constituent Emitting Centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14043–14049. 10.1021/ja902533f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prlj A.; Begušić T.; Zhang Z. T.; Fish G. C.; Wehrle M.; Zimmermann T.; Choi S.; Roulet J.; Moser J.-E.; Vaníček J. Semiclassical Approach to Photophysics Beyond Kasha’s Rule and Vibronic Spectroscopy Beyond the Condon Approximation. The Case of Azulene. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16, 2617–2626. 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binsch G.; Heilbronner E.; Jankow R.; Schmidt D. On the Fluorescence Anomaly of Azulene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1967, 1, 135–138. 10.1016/0009-2614(67)85008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klemp D.; Nickel B. Relative Quantum Yield of the S2 → S1 Fluorescence from Azulene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1986, 130, 493–497. 10.1016/0009-2614(86)80245-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal J. A.; Ghosh H. N.; Mukherjee T.; Palit D. K. S2 Fluorescence and Ultrafast Relaxation Dynamics of the S2 and S1 States of a Ketocyanine Dye. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 6836–6846. 10.1021/jp0508498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung J.; Kim P.; Saga S.; Hayashi S.; Osuka A.; Kim D. S2 Fluorescence Dynamics of Meso-Aryl-Substituted Subporphyrins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12632–12635. 10.1002/anie.201307566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G.; Yan D.; Hu J.; Wan J.; Xia B.; Vullev V. I. Photoinduced Electron Transfer in Arylacridinium Conjugates in a Solid Glass Matrix. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 6921–6929. 10.1021/jp072224a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.; Xia B.; Bao D.; Ferreira A.; Wan J.; Jones G. II; Vullev V. I. Long-Lived Photogenerated States of α-Oligothiophene–Acridinium Dyads Have Triplet Character. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 3096–3107. 10.1021/jp810909v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C.; Zhang S.; Gao Y.; Liu H.; Shan T.; Liang X.; Yang B.; Ma Y. Ternary Emission of Fluorescence and Dual Phosphorescence at Room Temperature: A Single-Molecule White Light Emitter Based on Pure Organic Aza-Aromatic Material. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1802407. 10.1002/adfm.201802407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. H.; Xiao H.; Chen B.; Weiss R. G.; Chen Y. Z.; Tung C. H.; Wu L. Z. Multiple-State Emissions from Neat, Single-Component Molecular Solids: Suppression of Kasha’s Rule. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10173–10178. 10.1002/anie.202000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng H. W.; Shen J. Y.; Kuo T. Y.; Tu T. S.; Chen Y. A.; Demchenko A. P.; Chou P. T. Excited-State Intramolecular Proton-Transfer Reaction Demonstrating Anti-Kasha Behavior. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 655–665. 10.1039/c5sc01945a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Wang R.-Z.; Zhao C.-H. Temperature-Dependent Dual Fluorescence from Small Organic Molecules. Org. Mater. 2022, 4, 204–215. 10.1055/a-1953-0322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sednev M. V.; Belov V. N.; Hell S. W. Fluorescent Dyes with Large Stokes Shifts for Super-Resolution Optical Microscopy of Biological Objects: A Review. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 2015, 3, 042004. 10.1088/2050-6120/3/4/042004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Zhang H.; Liu G.; Kong L.; Zhu X.; Tian X.; Zhang Z.; Zhang R.; Wu Z.; Tian Y.; Zhou H. Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probes for Super-Resolution and Dynamic Tracking of Lipid Droplets. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 977–982. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b04079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.; Begoyan V. V.; Tanasova M.; Waters K.; Seel M.; Pandey R. Coumarins: Spectroscopic measurements and first principles calculations of C4-substituted 7-aminocoumarins. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2018, 31, e3852 10.1002/poc.3852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.; Chen D.-G.; Wang C.-H.; Lan Y.-C.; Liu Y.-H.; Chou P.-T.; Chen C.-T. Tailoring C-6-Substituted Coumarin Scaffolds for Novel Photophysical Properties and Stimuli-Responsive Chromism. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 11557–11565. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c08133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Cole J. M.; Xu Z. Substantial Intramolecular Charge Transfer Induces Long Emission Wavelengths and Mega Stokes Shifts in 6-Aminocoumarins. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 13274–13279. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b04176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel A. Preparation of Benzoic Acid from Tonka Beans and from the Flowers of Melilot or Sweet Clover. Ann. Phys. 1820, 64, 161–166. 10.1002/andp.18200640205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pechmann H. v. Neue Bildungsweise Der Cumarine. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1884, 17, 929–936. 10.1002/cber.188401701248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Usui K.; Yamamoto K.; Ueno Y.; Igawa K.; Hagihara R.; Masuda T.; Ojida A.; Karasawa S.; Tomooka K.; Hirai G.; et al. Internal-Edge-Substituted Coumarin-Fused [6] Helicenes: Asymmetric Synthesis, Structural Features, and Control of Self-Assembly. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24, 14617–14621. 10.1002/chem.201803270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasior M.; Kim D.; Singha S.; Krzeszewski M.; Ahn K. H.; Gryko D. T. π-Expanded Coumarins: Synthesis, Optical Properties and Applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 1421–1446. 10.1039/c4tc02665a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tasior M.; Deperasińska I.; Morawska K.; Banasiewicz M.; Vakuliuk O.; Kozankiewicz B.; Gryko D. T. Vertically π-Expanded Coumarin–Synthesis via the Scholl Reaction and Photophysical Properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 18268–18275. 10.1039/c4cp02003k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasior M.; Poronik Y. M.; Vakuliuk O.; Sadowski B.; Karczewski M.; Gryko D. T. V-Shaped Bis-Coumarins: Synthesis and Optical Properties. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 8723–8732. 10.1021/jo501565r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Węcławski M. K.; Deperasińska I.; Banasiewicz M.; Young D. C.; Leniak A.; Gryko D. T. Building Molecular Complexity from Quinizarin: Conjoined Coumarins and Coronene Analogs. Chem.–Asian J. 2019, 14, 1763–1770. 10.1002/asia.201800757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Węcławski M. K.; Jakešová M.; Charyton M.; Demitri N.; Koszarna B.; Oppelt K.; Sariciftci S.; Gryko D. T.; Głowacki E. D. Biscoumarin-Containing Acenes as Stable Organic Semiconductors for Photocatalytic Oxygen Reduction to Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 20780–20788. 10.1039/c7ta05882a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Węcławski M. K.; Tasior M.; Hammann T.; Cywiński P. J.; Gryko D. T. From π-Expanded Coumarins to π-Expanded Pentacenes. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 9105–9108. 10.1039/c4cc03078h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazir R.; Stasyuk A. J.; Gryko D. T. Vertically π-Expanded Coumarins: The Synthesis and Optical Properties. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 11104–11114. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A.; Hossen T.; Ghosh I.; Koner A. L.; Nau W. M.; Sahu K.; Moorthy J. N. Helicity-Dependent Regiodifferentiation in the Excited-State Quenching and Chiroptical Properties of Inward/Outward Helical Coumarins. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 14797. 10.1002/chem.201701787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A.; Maka V. K.; Moorthy J. N. Remarkable Influence of ‘Phane Effect’on the Excited-State Properties of Cofacially Oriented Coumarins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 4758–4767. 10.1039/c6cp07720j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji M.; Hakoda Y.; Okamoto H.; Tani F. Photochemical Synthesis and Photophysical Properties of Coumarins Bearing Extended Polyaromatic Rings Studied by Emission and Transient Absorption Measurements. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 555–563. 10.1039/c6pp00399k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Arbeloa T.; Lopez Arbeloa F.; Tapia M. J.; Lopez Arbeloa I. Hydrogen-Bonding Effect on the Photophysical Properties of 7-Aminocoumarin Derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 4704–4707. 10.1021/j100120a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G.; Jackson W. R.; Choi C. Y.; Bergmark W. R. Solvent Effects on Emission Yield and Lifetime for Coumarin Laser Dyes. Requirements for a Rotatory Decay Mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. 1985, 89, 294–300. 10.1021/j100248a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G.; Jackson W. R.; Kanoktanaporn S.; Halpern A. M. Solvent Effects on Photophysical Parameters for Coumarin Laser Dyes. Opt. Commun. 1980, 33, 315–320. 10.1016/0030-4018(80)90252-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. II.; Jackson W. R.; Halpern A. M. Medium Effects on Fluorescence Quantum Yields and Lifetimes for Coumarin Laser Dyes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1980, 72, 391–395. 10.1016/0009-2614(80)80314-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gompel J. A.; Schuster G. B. Photophysical Behavior of Ester-Substituted Aminocoumarins: A New Twist. J. Phys. Chem. 1989, 93, 1292–1295. 10.1021/j100341a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bangar Raju B.; Costa S. M. B. Photophysical Properties of 7-Diethylaminocoumarin Dyes in Dioxane–Water Mixtures: Hydrogen Bonding, Dielectric Enrichment and Polarity Effects. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1999, 1, 3539–3547. 10.1039/a903549d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sulpizi M.; Carloni P.; Hutter J.; Rothlisberger U. A Hybrid TDDFT/MM Investigation of the Optical Properties of Aminocoumarins in Water and Acetonitrile Solution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 4798–4805. 10.1039/b305846h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma K.; Suzuki S.; Uchiyama S.; Kajiro T.; Santa T.; Imai K. A Study of the Relationship between the Chemical Structures and the Fluorescence Quantum Yields of Coumarins, Quinoxalinones and Benzoxazinones for the Development of Sensitive Fluorescent Derivatization Reagents. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2003, 2, 443–449. 10.1039/b300196b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kemary M.; Rettig W. Multiple Emission in Coumarins with Heterocyclic Substituents. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 5221–5228. 10.1039/b308712c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Xu Z.; Cole J. M. Molecular Design of UV–Vis Absorption and Emission Properties in Organic Fluorophores: Toward Larger Bathochromic Shifts, Enhanced Molar Extinction Coefficients, and Greater Stokes Shifts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 16584–16595. 10.1021/jp404170w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singha S.; Kim D.; Roy B.; Sambasivan S.; Moon H.; Rao A. S.; Kim J. Y.; Joo T.; Park J. W.; Rhee Y. M.; et al. A Structural Remedy toward Bright Dipolar Fluorophores in Aqueous Media. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 4335–4342. 10.1039/c5sc01076d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Lin X.; Ji X.; Xu S.; Liu C.; Dong X.; Zhao W. Azetidine-Containing Heterospirocycles Enhance the Performance of Fluorophores. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 4413–4417. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm J. B.; English B. P.; Chen J.; Slaughter J. P.; Zhang Z.; Revyakin A.; Patel R.; Macklin J. J.; Normanno D.; Singer R. H.; et al. A General Method to Improve Fluorophores for Live-Cell and Single-Molecule Microscopy. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 244–250. 10.1038/nmeth.3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Cole J. M.; Waddell P. G.; Lin T.-C.; Radia J.; Zeidler A. Molecular Origins of Optoelectronic Properties in Coumarin Dyes: Toward Designer Solar Cell and Laser Applications. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 727–737. 10.1021/jp209925y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystkowiak E.; Dobek K.; Burdziński G.; Maciejewski A. Radiationless Deactivation of 6-Aminocoumarin from the S 1-ICT State in Nonspecifically Interacting Solvents. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012, 11, 1322–1330. 10.1039/c2pp25065a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig W.; Klock A. Intramolecular Fluorescence Quenching in Aminocoumarines. Identification of an Excited State with Full Charge Separation. Can. J. Chem. 1985, 63, 1649–1653. 10.1139/v85-277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krystkowiak E.; Bachorz R. A.; Koput J. Ground and Excited State Hydrogen Bonding Effects of 6-Aminocoumarin in Water: An Ab Initio Study. Dyes Pigm. 2015, 112, 335–340. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2014.07.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. M.; Fang X. Z.; Yang P. R.; Yi J. S.; Ko Y. G.; Piao M. J.; Chung Y. D.; Park Y. W.; Jeon S. J.; Cho B. R. Design of Molecular Two-Photon Probes for in Vivo Imaging. 2H-Benzo[h]Chromene-2-One Derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 2791–2795. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.01.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.; Singha S.; Wang T.; Seo E.; Lee J. H.; Lee S.-J.; Kim K. H.; Ahn K. H. In vivo two-photon fluorescent imaging of fluoride with a desilylation-based reactive probe. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 10243–10245. 10.1039/c2cc35668f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I.; Kim D.; Sambasivan S.; Ahn K. H. Synthesis of Π-Extended Coumarins and Evaluation of Their Precursors as Reactive Fluorescent Probes for Mercury Ions. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2012, 1, 60–64. 10.1002/ajoc.201200034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.; Xuan Q. P.; Moon H.; Jun Y. W.; Ahn K. H. Synthesis of Benzocoumarins and Characterization of Their Photophysical Properties. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2014, 3, 1089–1096. 10.1002/ajoc.201402107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jun Y. W.; Kim H. R.; Reo Y. J.; Dai M.; Ahn K. H. Addressing the Autofluorescence Issue in Deep Tissue Imaging by Two-Photon Microscopy: The Significance of Far-Red Emitting Dyes. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 7696–7704. 10.1039/c7sc03362a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reo Y. J.; Jun Y. W.; Cho S. W.; Jeon J.; Roh H.; Singha S.; Dai M.; Sarkar S.; Kim H. R.; Kim S.; Jin Y.; Jung Y. L.; Yang Y. J.; Ban C.; Joo J.; Ahn K. H. A Systematic Study on the Discrepancy of Fluorescence Properties between in Solutions and in Cells: Super-Bright, Environment-Insensitive Benzocoumarin Dyes. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 10556–10559. 10.1039/d0cc03586f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y.; Park N. K.; Kang S.; Huh Y.; Jung J.; Hur J. K.; Kim D. Latent Turn-on Fluorescent Probe for the Detection of Toxic Malononitrile in Water and Its Practical Applications. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1095, 154–161. 10.1016/j.aca.2019.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X.-L.; Guo Z.-J.; Zhang C.; Ren A.-M. Excellent Benzocoumarin-Based Ratiometric Two-Photon Fluorescent Probe for H 2 O 2 Detection. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 281–291. 10.1039/c8cp06050a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y.; Jung J.; Huh Y.; Kim D. Benzo [] Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probes for Bioimaging Applications. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2018, 2018, 5249765. 10.1155/2018/5249765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielesiński Ł.; Gryko D. T.; Sobolewski A. L.; Morawski O. The Interplay between Solvation and Stacking of Aromatic Rings Governs Bright and Dark Sites of Benzo[g]Coumarins. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 15305–15314. 10.1002/chem.201903018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDANIEL D. H.; Brown H. C. An Extended Table of Hammett Substituents Constants Based on the Ionization of Substituted Benzoic Acids. J. Org. Chem. 1958, 23, 420–427. 10.1021/jo01097a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C.; Leo A.; Taft R. W. A Survey of Hammett Substituent Constants and Resonance and Field Parameters. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 165–195. 10.1021/cr00002a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza E. M.; Clark J. A.; Soliman J.; Derr J. B.; Morales M.; Vullev V. I. Practical Aspects of Cyclic Voltammetry: How to Estimate Reduction Potentials When Irreversibility Prevails. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, H3175–H3187. 10.1149/2.0241905jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mari O.; Vullev V. I. Electrochemical Analysis in Charge-Transfer Science: The Devil in the Details. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2022, 31, 100862. 10.1016/j.coelec.2021.100862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Häser M. RI-MP2: First Derivatives and Global Consistency. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1997, 97, 331–340. 10.1007/s002140050269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer J. Beyond the Random-Phase Approximation: A New Approximation Scheme for the Polarization Propagator. Phys. Rev. A 1982, 26, 2395–2416. 10.1103/PhysRevA.26.2395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trofimov A. B.; Schirmer J. An Efficient Polarization Propagator Approach to Valence Electron Excitation Spectra. J. Phys. B: At., Mol. Opt. Phys. 1995, 28, 2299–2324. 10.1088/0953-4075/28/12/003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hättig C.Structure Optimizations for Excited States with Correlated Second-Order Methods: CC2 and ADC(2). In Advances in Quantum Chemistry; Jensen H. J. Å., Ed.; Academic Press, 2005; Vol. 50, pp 37–60. 10.1016/S0065-3276(05)50003-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burow A. M.; Sierka M.; Mohamed F. Resolution of Identity Approximation for the Coulomb Term in Molecular and Periodic Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 214101. 10.1063/1.3267858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turbomole V7.4 2019, A Development of Univeristy of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1989-2007, Turbomole GmbH, since 2007; Available from http://www.turbomole.com.

- Klamt A.; Schüürmann G. COSMO: a new approach to dielectric screening in solvents with explicit expressions for the screening energy and its gradient. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 5, 799–805. 10.1039/P29930000799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafikov M. Z.; Brandl F.; Dick B.; Czerwieniec R. Can Coumarins Break Kasha’s Rule?. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 6468–6471. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b02292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock D.; Ingle R. A.; Sazanovich I. V.; Clark I. P.; Harabuchi Y.; Taketsugu T.; Maeda S.; Orr-Ewing A. J.; Ashfold M. N. R. Contrasting ring-opening propensities in UV-excited α-pyrone and coumarin. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 2629–2638. 10.1039/C5CP06597F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski B.; Kaliszewska M.; Poronik Y. M.; Czichy M.; Janasik P.; Banasiewicz M.; Mierzwa D.; Gadomski W.; Lohrey T. D.; Clark J. A.; Łapkowski M.; Kozankiewicz B.; Vullev V. I.; Sobolewski A. L.; Piatkowski P.; Gryko D. T. Potent Strategy towards Strongly Emissive Nitroaromatics through a Weakly Electron-Deficient Core. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 14039–14049. 10.1039/d1sc03670j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.