Abstract

Introduction

Tumors of the uterine tube are rare pathologies representing less than 1 % of all gynecologic cancers; they are dominated by adenocarcinomas. Secondary metastatic forms are the most frequent, whereas primary tumors are very rare and represent only 10 %, which suggests that the fallopian tube is an organ with low oncogenic potential.

Report of two cases

We report the two cases of a patients followed in the gynecology department C of the CHU IBN ROCHD CASA for a primary tubal adenocarcinoma.

Discussion

The diagnosis of its origin is difficult preoperatively, the treatment and staging are the same as for ovarian cancer.

Conclusion

The treatment is also identical to the management of ovarian cancer, but their prognosis is better because they are most often diagnosed at an earlier stage.

Keywords: Trump, cancer, Diagnosis, Treatment

Highlights

-

•

Tumors of the uterine tube are rare pathologies representing less than 1% of all gynecologic cancers; they are dominated by adenocarcinomas .

-

•

Primary fallopian tube cancers are rare, representing 0.3 to 1.1% of gynaecological cancers.

-

•

They are frequently confused with ovarian cancers in case of locally advanced disease and are clearly underestimated

-

•

The treatment is also identical to the management of ovarian cancer, but their prognosis is better because they are most often diagnosed at an earlier stage.

1. Introduction

Primary tubal cancer is rare, often affecting postmenopausal women of unknown etiology, but it often occurs in the context of infertility, impoverishment, chronic tubal infection or on a genetic background (BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation) [1]. It was first described in 1847 by Renaud [2]. Its frequency does not exceed 1 %, the clinical signs are often dissociated, the preoperative diagnosis is difficult, with a prognosis that depends on the stage of the disease.

We report the case of a patient with a history of breast cancer and followed for primary adenocarcinoma of the tube that recurred 5 years after the initial totalization, through this case and a review of the literature we will try to support the risk factors and symptomatology as well as the management of these tumors.

1.1. Observation 1

This is a 62 year old female patient, IGIP, postmenopausal, never had oral contraception, no notion of recurrent genital infection, She had undergone a subtotal hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy in 2015 for a 10 cm right latero uterine mass. Anatomopathological study showed a right intra tubal serous adenocarcinoma, grade III, without ovarian involvement or epiplon invasion. The patient received 6 courses of HTC, CA 125 was 192, a trachelectomy was performed 1 year later with non-specific fibrous remodeling with chronic exocervicitis, without signs of malignancy. 4 years later the patient consulted for chronic pelvic pain for 6 months, of increasing intensity, without signs of urinary or digestive compression. The clinical examination found a patient in good general condition, with good vitals, a supple abdomen, no clinically palpable mass, the vaginal slice was clean without lesions, the senological examination and the rest of the somatic examination were unremarkable.

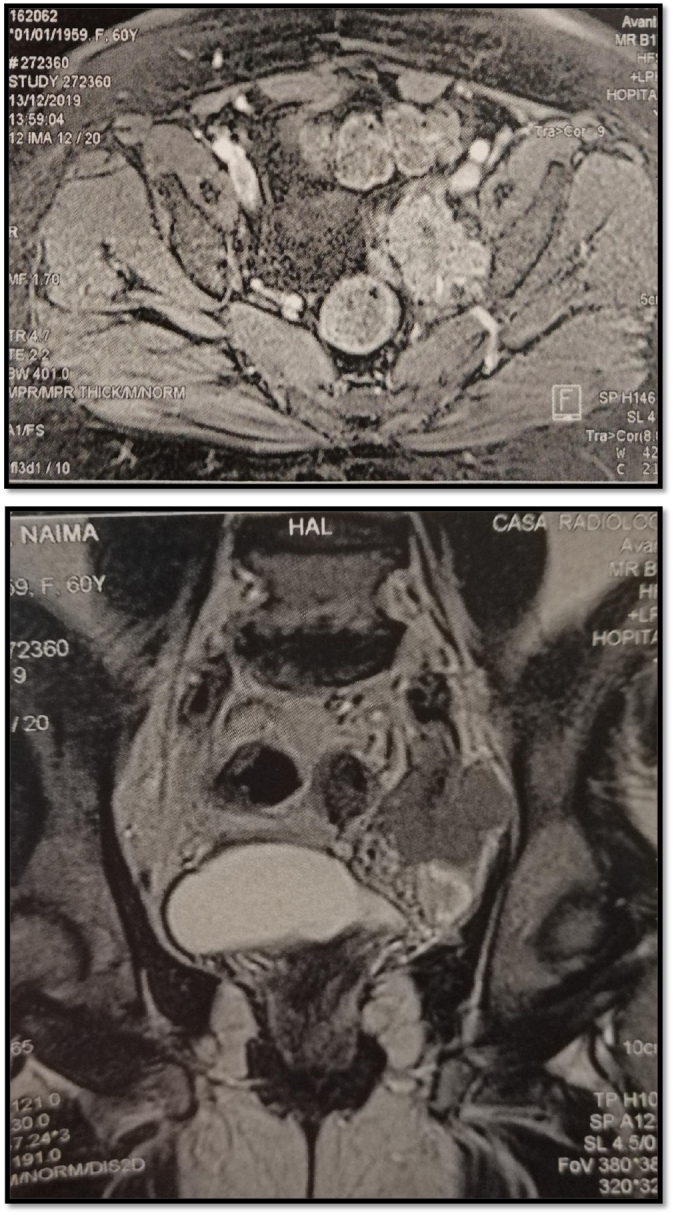

A pelvic MRI was performed showing a solid cystic mass measuring 52 mm in width, 42 mm in anteroposterior diameter, 64 mm in height, in contact with the bowel and bladder with no signs of infiltration and no associated adenopathy (Figs. 1 and 2), CA 125: 321.6 IU/l.

Figs. 1 and 2.

MRI appearance of recurrent tubal adenocarcinoma.

Exploration revealed a mass adherent to the right iliac vein without invading it, an excision was performed with anatomopathological examination: tubal adenocarcinoma grade III, then the patient was referred for adjuvant chemotherapy.

1.2. Observation 2

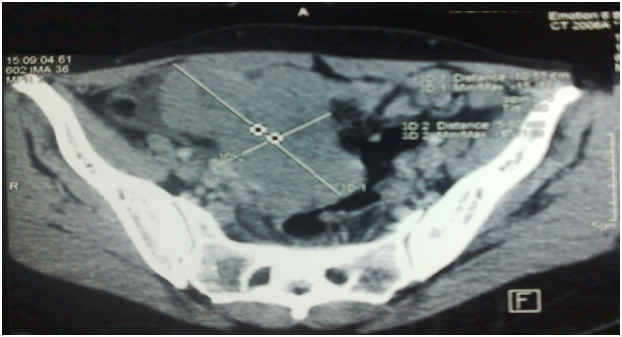

Patient aged 42 years, single, with no personal or family history. She consulted for pelvic pain with a one-month-old pelvic mass. Examination revealed a hard abdominal-pelvic mass, measuring eight centimeters, which could not be displaced from the uterus. Ultrasound showed a solid, Doppler-vascularized mass measuring 112 × 85 mm. Abdominal-pelvic CT scan showed a patchy necrotic pelvic-abdominal tissue lesion, poorly enhanced by contrast injection, measuring 100 × 70 × 60 mm (Fig. 3). There were multiple peritoneal nodules with mesenteric fat over density as well as pelvic, lumbo-aortic, and inter-aortic-caval adenopathies. The liver and spleen were homogeneous and without focal lesions. Classification according to TNM 4 C [3], CA 125 was increased to 708 IU/ml.

Fig. 3.

Abdominopelvic scan showing a pelvic-abdominal injury, tissue necrosis in places, slightly hand colored by the injection of contrast.

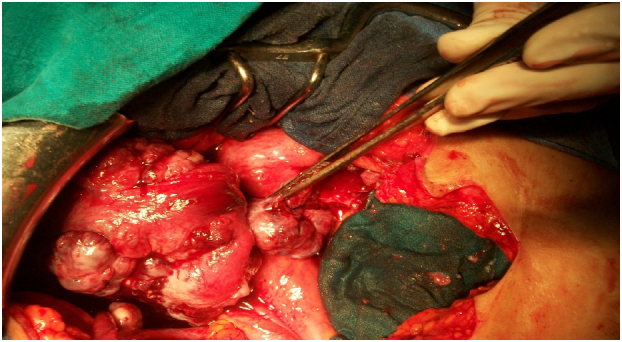

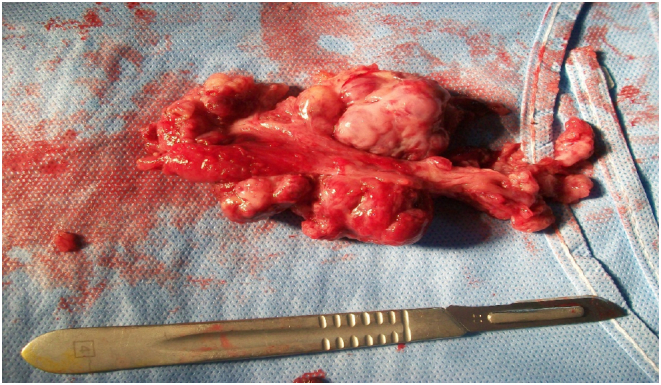

An exploratory laparotomy showed a solid vegetative tumor, measuring 100 × 80 mm, of the right tube. Both ovaries and the contralateral tube were free of lesions (Fig. 3). The tumor invaded the bladder and vermicular appendage. An ascites of 150 ml was aspirated. A biopsy of the tumor measuring 80 × 70 × 20 mm was sent for extemporaneous examination (Fig. 4). The result of this biopsy showed a poorly differentiated and invasive malignant tumor proliferation whose origin could only be defined after fixation and kerosene inclusion. A total hysterectomy with ovariectomy, appendectomy, omentectomy, peritoneal biopsies, and partial bladder resection were performed (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). The postoperative course was straightforward. The patient was discharged on the 15th day. The pathological diagnosis showed a solid, whitish tumor proliferation infiltrating the right tube, extending to the mesotubal area, adhering to the right lateral aspect of the uterine body and measuring 12 cm in diameter. It was consistent with a serous adenocarcinoma. The left adnexa, uterine body, cervix and omentum were free of tumor. A chest X-ray was normal. After a six-month follow-up, no recurrence was found (see Fig. 7).

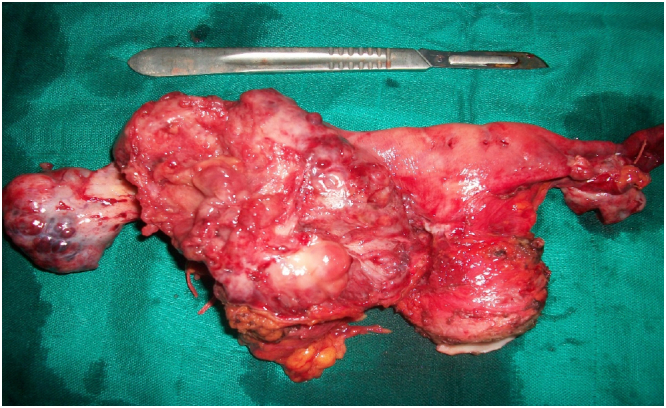

Fig. 4.

Preoperative view showing a solid tumor vegetating, measuring 100/80 mm of the right tube. Both ovaries and the contralateral horn were free of any macroscopic lesion.

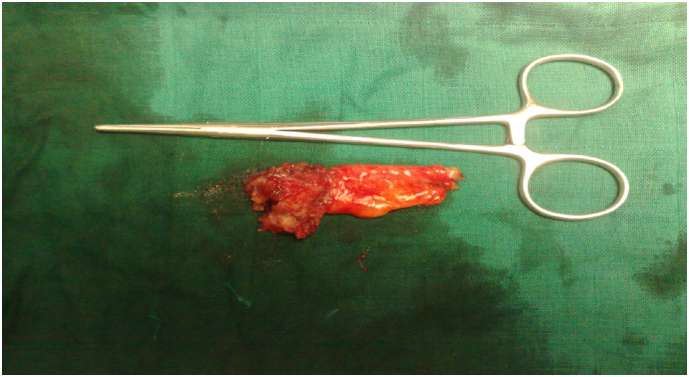

Fig. 5.

A tumor biopsy with the right tube tumor, sent in frozen section.

Fig. 6.

Surgical specimen of hysterectomy without conservation adnexal tumor showing tubal right. The two ovaries are macroscopically intact.

Fig. 7.

Room appendectomy showing the invasion of it by the tubal tumor.

2. Discussion

Tubal cancer is the rarest cancer of the genital tract representing 0.1 to 1.98 % of all gynecologic cancers [1]. It is a pathology that affects patients in the 5th decade with extreme ages of 18 and 87 years. Our patient is 62 years old and primiparous with a history of invasive breast carcinoma. Several authors have noted the association of tubal adenocarcinoma with impoverishment, infertility and chronic or genetic salpingitis, prompting a search for a deleterious BRCA1/2 chromosomal mutation, in our patient this association could not be sought due to lack of means [1].

The symptoms are not specific, often associating a pelvic mass, bleeding, and pain, but the pathognomonic triad is hydropstubaeprofluens associating abundant fluid loss, pelvic colic, and a mass is described in only 10 to 15 % of cases [4].

The first paraclinical examination to be requested is ultrasonography, which often shows the same aspect of epithelial carcinomas of the ovary in the form of a mixed adnexal mass, solid and cystic, hypervascularized on Doppler [[5], [6]]. Pelvic MRI is used for staging; the typical appearance of a tubal carcinoma is manifested by a hyperintense T2-weighted signal and a hypointense T1-weighted signal with a solid appearance. The tumor markers, mainly Ca125, are sensitive but not specific and are often elevated [[7], [8]].

Staging is based on ovarian cancer [4].

The treatment is also identical to the management of ovarian cancer, but their prognosis is better because they are most often diagnosed at an earlier stage. 9] The reference surgery is total hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, omentectomy, pelvic and lomboaortic curage. Chemotherapy combining cisplatin and paclitaxel has the same indications as for ovarian cancer. Radiotherapy is abandoned because of its low efficacy [[10], [11]].

The prognosis depends on tumor size [4], stage [12], invasion [13], and the existence of a macroscopic postoperative residue [4]. The prognostic role of gene alteration of p53, Kras, c-erb-2 and immunolabeling of the tumor with CA125 is being evaluated [4].

The 5-year overall survival of tubal malignancies is estimated to be 44 % according to major series [[9], [10], [11]].

3. Conclusion

Tubal adenocarcinoma is a rare entity, of unknown etiology, underestimated or often confused with ovarian pathology with which it shares the same treatment and staging, the positive diagnosis is difficult because the clinical picture is polymorphic, MRI brings a great diagnostic interest, the prognosis depends on the FIGO stage.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

I declare on my honor that the ethical approval has been exempted by my establishment.

Consent

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from the patient.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Watik Fedoua: Corresponding author.

Mouna harrad: writing the paper.

Hasnaa said: writing the paper.

Boufettal Houssin: correction of the paper.

Mahdaoui Sakher: correction of the paper.

Samouh Naima: correction of the paper.

Guarantor

Dr Fedoua Watik.

Registration of research studies

researchregistry2464.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare having no conflicts of interest for this article.

References

- 1.-Tumeurs primitives de la trompe de Fallope, L. Dion a, K. Nyangoh-Timoh a, S. Henno b, H. Sardain a, c, F. Foucher a, c, J. Levêque a, c, V. Lavoué a, c, Service de gynécologie, CHU Anne-de-Bretagne, Site Hôpital Sud, 16, boulevard de Bulgarie, BP 90347, 35203 Rennes cedex 2, France, 2020.

- 2.-Sur le Carcinome Primaire Dans la Trompe De FallopeAvec Exposé D'un Cas Alfred Zacho, 1993.

- 3.ADÉNOCARCINOME tubaire primitif: A propos de 02 cas et revue de la littératureTazi charki M. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikuri N., Duska L.R. Fallopian tube carcinomaSurg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 1998;7(2):363–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko M.L., Jeng C.J., Chen S.C., Tzeng C.R. Sonographicappearance of fallopian tube carcinoma. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2005;33:372–374. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patlas M., Rosen B., Chapman W., Wilson S.R. Sonographicdiagnosis of primarymalignanttumors of the fallopiantubeUltrasound Q. 2004;20:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies A.P., Fish A., Woolas R., Oram D. Raisedserum CA 125 preceding the diagnosis of carcinoma of the fallopian tube: two case reports Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1991;98:602–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb10381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casey M.J., Synder C., Bewtra C., Narod S.A., Watson P., Lynch H.T. Intra-abdominal carcinomatosisafterprophylacticoophorectomy in women of hereditarybreastovarian cancer syndrome kindredsassociatedwith BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations Gynecol. Oncol. 2005;97:457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wethington S.L., Herzog T.J., Seshan V.E., Bansal N., Schiff P.B., Burke W.M., et al. Improvedsurvival for fallopian tube cancer: a comparison of clinicalcharacteristics and outcome for primaryfallopian tube and ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:3298–3306. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.-Querleu D, Bonnier P, Morice P, Narducci F. Prise en charge initiale des cancers gynécologiques: référentiels de la Société Française d'Oncologie Gynécologique. Référentiel de traitement des tumeurs frontières et des cancers épithéliaux de l'ovaire. http://asfog.free.fr. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Heintz A.P., Odicino F., Maisonneuve P., Quinn M.A., Benedet J.L., Creasman W.T., et al. Carcinoma of the fallopian tube. FIGO 6th annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2006;95(suppl1):S145–S160. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.-M c M U R R AY E., JACOBS A., PEREZ C., CAMEL M., KAO M., GALAKATOS A. Carcinoma of fallopian tube: manag.

- 13.-DI RE E., GROSSO G., RASPAGLIESI F., BAIOCCHI G. Fallopian tube cancer: incidence and role of lymphaticspread. Gynecol. Oncol. 1996; 62: 199–202. [DOI] [PubMed]