Abstract

The gene celF of the cryptic cel operon of Escherichia coli has been cloned, and the encoded 6-phospho-β-glucosidase (cellobiose-6-phosphate [6P] hydrolase; CelF [EC 3.2.1.86]) has been expressed and purified in a catalytically active state. Among phospho-β-glycosidases, CelF exhibits unique requirements for a divalent metal ion and NAD+ for activity and, by sequence alignment, is assigned to family 4 of the glycosylhydrolase superfamily. CelF hydrolyzed a variety of P-β-glucosides, including cellobiose-6P, salicin-6P, arbutin-6P, gentiobiose-6P, methyl-β-glucoside-6P, and the chromogenic analog, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside-6P. In the absence of a metal ion and NAD+, purified CelF was rapidly and irreversibly inactivated. The functional roles of the cofactors have not been established, but NAD+ appears not to be a reactant and there is no evidence for reduction of the nucleotide during substrate cleavage. In solution, native CelF exists as a homotetramer (Mw, ∼200,000) composed of noncovalently linked subunits, and this oligomeric structure is maintained independently of the presence or absence of a metal ion. The molecular weight of the CelF monomer (Mr, ∼50,000), estimated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, is in agreement with that calculated from the amino acid sequence of the polypeptide (450 residues; Mr = 50,512). Comparative sequence alignments provide tentative identification of the NAD+-binding domain (residues 7 to 40) and catalytically important glutamyl residues (Glu112 and Glu356) of CelF.

The cel operon is one of three cryptic operons designated bgl (19, 28, 35), asc (11, 24), and cel (10, 16) that, when suitably activated (2, 31, 34), allow growth of Escherichia coli on β-glucosides. The cel operon maps to the 39.1- to 39.2-min region of the bacterial chromosome and contains six genes (celABCDFG) whose products promote the accumulation and dissimilation of cellobiose, salicin, and arbutin by the organism (10, 25). In sequential order, the genes celABC encode the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar-phosphotransferase components IIBcel, IICcel, and IIAcel (15, 25, 30) that catalyze the phosphorylation and simultaneous translocation of β-glucosides across the cytoplasmic membrane. (For a discussion of phosphotransferase functions and nomenclature, see references 21, 27, and 32). The next gene in the operon (celD) encodes a repressor, and celF encodes a phospho (P)-β-glucosidase (CelF) that hydrolyzes O-β-linked phosphorylated derivatives to generate glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) and appropriate aglycone (26). The product of celG has not been characterized. Activation of the cel operon can occur either via insertion of IS1, IS2, or IS5 into a region 72 to 180 bp upstream of the transcription start site or by base substitutions in celD such that the repressor is able to recognize cellobiose, arbutin, and salicin as inducers (26). In a recent report, Keyhani and Roseman suggest that the cel operon may also allow growth of E. coli on the chitin disaccharide N,N′-diacetylchitobiose without requirement for mutational activation (15).

Hall and coworkers (17, 26) obtained evidence for the CelF-catalyzed hydrolysis of P-β-glucosides by extracts prepared from cellobiose-grown cells of E. coli. However, despite repeated attempts, purification of CelF was never achieved because of the instability of the enzyme. That difficulty should be encountered in purification of CelF from E. coli was surprising, because the purification of two other P-β-glucosidases (BglA and BglB) from this organism had been relatively straightforward (28, 29, 46, 49). Additionally, hydrolysis of the chromogenic substrate p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside-6P (pNPβG6P) by BglA, BglB, and extracts containing CelF suggested catalytic similarity among the three P-β-glucosidases. Differences between CelF and the other P-β-glucosidases were evident at the molecular level, and comparative alignment of amino acid sequences revealed little homology between the sequence deduced for the polypeptide encoded by celF and those deduced for BglA and BglB. Furthermore, when classified by the amino acid sequence-based method of Henrissat and Bairoch (12, 13), BglA and BlgB were included in family 1 whereas CelF was assigned to family 4 of the glycosylhydrolase superfamily (5, 8, 12, 40).

From microbial-genome-sequencing projects of the past decade, 16 bacterial glycosylhydrolases (some putative) can now be assigned to family 4 (see Fig. 2). However, it was only recently that the first two enzymes (both P-α-glucosidases) from this family were purified in active form. Both enzymes (MalH from Fusobacterium mortiferum [39] and GlvA from Bacillus subtilis [40]) are unstable, and both exhibit unique requirements for divalent metal ions (Mn2+, Ni2+, Co2+, or Fe2+) and nucleotide (NAD+) for activity. Realizing that other members of family 4 might also require these (or additional) cofactors, we renewed our attempts to purify CelF from E. coli in a catalytically active state. Success in this collaborative effort required (i) high expression of CelF in a strain of E. coli devoid of all other P-β-glucosidases, (ii) synthesis of both natural and artificial substrates of CelF, and (iii) inclusion of Mn2+ and NAD+ in chromatography buffers during purification of the enzyme.

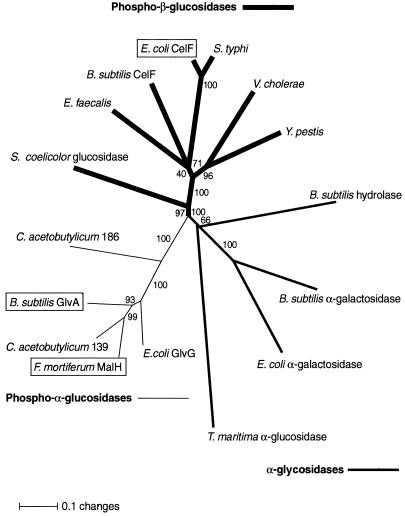

FIG. 2.

Unrooted neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of family 4 glycosylhydrolases. The 16 protein sequences were aligned by the program CLUSTAL X (41, 42). For pairwise alignments, a gap-opening penalty of 35 and a gap extension penalty of 0.75 were used. For multiple alignments, a gap-opening penalty of 15 and a gap extension penalty of 0.3 were used. The alignment was used to construct the neighbor-joining tree (33) as implemented by PAUP (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony) version 4.0b1a (37, 38). The numbers are bootstrap values, and branch lengths indicate the fraction of amino acid substitutions, as indicated on the scale. Proteins that have been purified to homogeneity and characterized are boxed. Entries without gene or protein names (E. faecalis, V. cholerae, etc.) are derived from sequences of unfinished genomes.

In this communication, we describe the purification, substrate specificity, and physicochemical properties of CelF from E. coli. By its intrinsic instability, unusual functional requirements (a divalent metal ion plus NAD+), and oligomeric structure, CelF exhibits properties that have not previously been described for other β- or P-β-glycosylhydrolases. Inclusion of CelF in family 4 of the glycosylhydrolase superfamily raises questions concerning the predictability of enzyme specificity, and the catalytic mechanism, for proteins based solely upon sequence-based alignment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Isoelectric focusing standards, Ampholine PAG plates (pH 3.5 to 9.5), and phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Ultrogel AcA-44 and Blue Tris-Acryl were from BioSepra. Enzymes, nucleotides, nitrophenyl glycosides, and DEAE Tris-Acryl M were supplied by Sigma Chemical Co. High-purity sugars were obtained from Pfanstiehl Laboratories. Reagents for chemical syntheses, including trimethylphosphate, phosphorus oxychloride, and cyclohexylamine, were purchased from Aldrich.

E. coli K-12 strains.

Strain MK91 is ΔlacZ4680 celR1::IS2 Δ(bgl-pho) rpsL ara-14 leuB6 ΔlacZ4680 lacY trpE38 his-208 argG77 metA160 galK2(Oc) (16). Strain LP100 is ΔlacZ4680 celR1::IS2 ΔcelBCDF Δ(bgl-pho) rpsL ara-14 leuB6 ΔlacZ4680 lacY trpE38 his-208 argG77 metA160 galK2(Oc) (24). Strain PEP0 is dTn10cam ebgA5100 ebgR+L532 rpsL ΔlacZ4680 (Hall Laboratory collection). Strain FCY2007arb11 is IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 trpA46 Δ(bgl-pho)201 Δtna arbT dTn10kan::bglA1000 (Hall Laboratory collection). Strain PEP24 is celR1::IS2 ΔcelBCDF Δ(bgl-pho) rpsL ara-14 leuB6 ΔlacZ4680 lacY his-208 metA160 galK2(Oc) dTn10cam::ebgA5100 ebgR+L532 dTn10kan::bglA1000. Strain PEP24 was constructed as follows. LP100:dTn10cam::ebgA5100 ebgR+L532 was transduced by bacteriophage P1vir from strain PEP0 into strain LP100 to create strain PEP21. A spontaneous Trp+ revertant of PEP21 was selected to create PEP22. A spontaneous Arg+ revertant of PEP22 was selected to create PEP23. dTn10kan::bglA1000 was transduced from strain FCY2007arb11 into strain PEP23 to create strain PEP24. Phenotypically, strain PEP24 exhibits no detectable P-β-glucosidase activity when assayed with pNPβG6P because the cel and bglGFB operons are deleted, bglA is disrupted by dTn10kan, and the asc operon is cryptic (silent). Strain PEP14 is celR1::IS2 Δ(bgl-pho) rpsL ara-14 leuB6 ΔlacZ4680 lacY his-208 metA160 galK2(Oc) dTn10cam ebgA5100 ebgR+L5322 dTn10kan bglA and was constructed as follows. dTn10cam::ebgA5100 ebgR+L532 was transduced by bacteriophage P1vir from strain PEP0 into strain MK91 to create strain PEP11. Trp+ was transduced from strain PEP23 into strain PEP11 to create strain PEP12. Arg+ was transduced from strain PEP23 into strain PEP12 to create strain PEP13. dTn10kan::bglA1000 was transduced from strain FCY2007arb11 into strain PEP13 to create strain PEP14. Phenotypically, strain PEP14 expresses the cel operon constitutively but expresses no other P-β-glucosidases because the bglGFB operon is deleted, bglA is disrupted by dTn10, and the asc operon is cryptic.

Construction of pUF4000.

Genomic DNA was prepared from strain PEP14 by the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method (3). The celF gene was amplified by the high-fidelity Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with primers corresponding to bp 1816760 to 1816784 and bp 1815080 to 1815105 of the E. coli genome (4). The left primer also included an EcoRI site, while the right primer included a BamHI site. The resulting 1.7-kb fragment was purified with a Qiagen PCR spin kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions, digested with EcoRI and BamHI, and ligated into similarly digested plasmid pSE380 (Invitrogen). The resulting construct, designated pUF4000, expresses celF under the control of the powerful pTAC promoter, which is controlled by the lacI-encoded Lac repressor. Because the plasmid also carries lacI, expression of celF is strongly repressed in the absence of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and is fully induced in the presence of 1 mM IPTG.

The celF sequence that was originally reported (25) (GenBank accession no. M64438) included errors that resulted in reporting CelF as a 378-amino-acid protein. The complete sequence of E. coli K-12 reported by Blattner et al. (4) showed that CelF is 78 amino acids longer than originally reported (GenBank accession no. AE000268). We have confirmed that the nucleotide sequence of celF in strain PEP14 is identical to that reported by Blattner et al. To determine whether any mutations had occurred during amplification of celF, both strands of the insert in pUF4000 were sequenced on an Applied Biosystems model 377 automated DNA sequencer and found to correspond exactly to the sequence reported by Blattner et al. (4). In pUF4000, translation proceeds from the strong ribosome binding site at bp 260 to 270 to generate an out-of-frame fusion with a C-terminal portion of the CelD protein that terminates at bp 365. It is likely that translation reinitiates to generate an in-frame C-terminal fragment of CelD that terminates at the normal stop codon of celD at bp 573. Translation of celF then initiates at bp 576 to yield an authentic CelF protein, as determined by sequencing the N-terminal 30 amino acids of the purified protein.

Growth of cells and preparation of cell extract.

E. coli PEP24(pUF4000) was grown at 37°C in a Tris-HCl–phosphate-buffered Casamino Acids–salts medium (pH 7.2) containing ampicillin (200 μg/ml). When the culture had reached an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.1, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM and growth was continued until the optical density at 600 nm was ∼1.0. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (13,000 × g for 10 min at 5°C) and washed by resuspension and centrifugation in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM MnSO4, and 50 μM NAD+ (designated TDMN buffer). The washed cells (55 g [wet weight]) were resuspended in 100 ml of TDMN buffer, and the organisms were disrupted at 0°C by two 1.5-min periods of sonic oscillation in a Branson sonifier operating at ∼75% maximum power. The cell extract was clarified by ultracentrifugation (180,000 × g for 2 h at 5°C).

Purification of CelF.

The enzyme was purified by conventional low-pressure chromatography in four stages: (i) DEAE Tris-Acryl M (anion exchange), (ii) phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B (hydrophobic interaction), (iii) Ultrogel AcA-44 (gel filtration), and (iv) Blue Tris-Acryl (affinity chromatography). All procedures were performed in the cold room.

Assay of CelF activity.

During purification, the specific activity of the enzyme was determined in a discontinuous assay with chromogenic pNPβG6P as a substrate. The 2-ml reaction mixture (at 37°C) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mM pNPβG6P, 1 mM MnSO4, and 0.1 mM NAD+. After addition of the enzyme preparation, samples (0.25 ml) were removed at intervals (usually over a 2- to 3-min period) and immediately injected into 0.75 ml of 0.5 M Na2CO3 containing 0.1 M EDTA to stop the reaction. The A400 was measured, and the amount of pNP was calculated from the molar extinction coefficient of the (yellow) p-nitrophenolate anion (ɛ = 18,300 M−1 cm−1). One unit of CelF activity is the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the formation of 1 μmol of pNP per min at 37°C. A continuous spectrophotometric assay was employed for substrate specificity studies and determination of kinetic parameters for CelF. In this assay, hydrolysis of P-β-glucoside (G6P formation) was monitored by the NAD+–plus–glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) (EC 1.1.1.49) coupled reaction. The standard 500-μl assay mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mM MnSO4, 1 mM NAD+, a 0.5 to 4 mM concentration range of the desired P-β-glucoside, and 2 U of G6PDH (from Leuconostoc mesenteroides). Reactions were initiated by the addition of 5 μl of purified CelF (188 μg of protein), and the increase in the A340 was recorded in a Beckman DU-70 spectrophotometer. A molar extinction coefficient (ɛ = 6,220 M−1 cm−1) for NADH was assumed for calculation of initial rates of substrate hydrolysis. Kinetic parameters were determined from Hofstee plots with an Enzyme Kinetics program (version 1.0c) (dogStar software). The products of cellobiose-6P cleavage were also determined by spectrophotometric assay with the further addition of ATP (5 mM) and 2 U of hexokinase (EC. 2.7.1.1) for glucose estimation.

Preparation of P-β-glycosides.

All P-β-glycosides were prepared in our laboratory. Chemical syntheses of pNPβG6P, pNPαG6P, pNPα-galactopyranoside-6P, pNPα-mannopyranoside-6P, and 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-glucopyranoside-6P (4MUβG6P) were initiated with the nonphosphorylated glycosides by the method of Wilson and Fox (46). Selective phosphorylation at the C-6 OH moiety of the glycopyranose was achieved by the use of a mixture of phosphorus oxychloride in trimethylphosphate containing small amounts of water. The phosphorylated derivatives were obtained as white, crystalline cyclohexylamine salts in 25 to 30% yield. Cellobiose-6P and other disaccharide and arylglycoside phosphates were prepared by enzymatic phosphorylation with the ATP-dependent β-glucoside kinase prepared from cellobiose-grown cells of Klebsiella pneumoniae (23). The P-β-glucosides were purified by a combination of Ba2+-ethanol precipitation, ion exchange, and paper chromatography.

Analytical procedures.

Native gel electrophoresis and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) were performed with the Novex XCell minicell system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Novex Tris-glycine (4 to 20%) gels were used for electrophoresis of CelF preparations under nonreducing conditions, and the Tris-glycine running buffer (pH 8.3) contained 0.1 mM NAD+ and 1 mM MnSO4. Novex NuPage (4 to 12%) Bis-Tris gels, MES (2-[N-morpholino]ethanesulfonic acid)-SDS running buffer (pH 7.3), and Novex Mark 12 wide-range molecular weight protein standards were used for SDS-PAGE experiments. A Multiphor flat-bed electrophoresis unit (Pharmacia) and precast Ampholine PAG plates (pH range, 3.5 to 9.5) were used for electrofocusing experiments. Protein concentrations were routinely determined by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent (Pierce). Microsequencing and electrospray mass spectrometry procedures have been described previously (40). Approximate Mr values for CelF were determined by fast protein liquid chromatography gel filtration with a Pharmacia Superose 6 HR 10/30 prepacked column and a Hewlett-Packard 1090 liquid chromatography system. The column was preequilibrated (flow rate, 0.4 ml/min; temperature, ∼23°C) with 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.1 M NaCl and calibrated with protein molecular weight standards. Protein samples (100 μg in 0.1 ml) were loaded onto the column, and elution was monitored at 280 nm.

Analytical ultracentrifugation.

Experiments were performed in the Beckman Optima model XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge by previously described procedures (40). Data analysis was performed with the software package installed by Beckman, together with software provided by Allen P. Minton (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health). The latter program can be downloaded from the World Wide Web (30a). The densities of dialysis buffers were determined at 20°C with an Anton Paar model DMA 58 densitometer. The partial specific volume for CelF (Vbar = 0.729 ml/g) was calculated from the deduced amino acid composition of the protein together with the values of Zamyatnin (50).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of E. coli PEP24.

The activity of CelF is easily monitored by the formation of the yellow p-nitrophenolate ion generated by hydrolysis of the chromogenic substrate, pNPβG6P. Unfortunately, the constitutively expressed BglA of E. coli also hydrolyzes this compound, and CelF activity is virtually undetectable against the BglA background. To circumvent this problem, E. coli PEP24 was constructed, in which bglA is disrupted by mini-Tn10kan insertion, the asc operon is cryptic, and both bgl and cel operons are deleted. Extracts of strain PEP24 contain no P-β-glucosidase activity.

Expression of CelF in E. coli PEP24(pUF4000).

Cells of E. coli PEP24 when transformed with pUF4000 produced high levels of an IPTG-inducible protein whose estimated molecular weight (Mr, ∼50,000) was that expected for the full-length polypeptide encoded by celF. The polypeptide was not present in a similarly prepared extract of the plasmid-free PEP24 parental strain. Native gel electrophoresis and subsequent in situ staining for CelF activity with 4MUβG6P as a substrate revealed a single zone of enzymatic activity (4MU fluorescence) only in the extract prepared from PEP24(pUF4000).

Purification and properties of CelF.

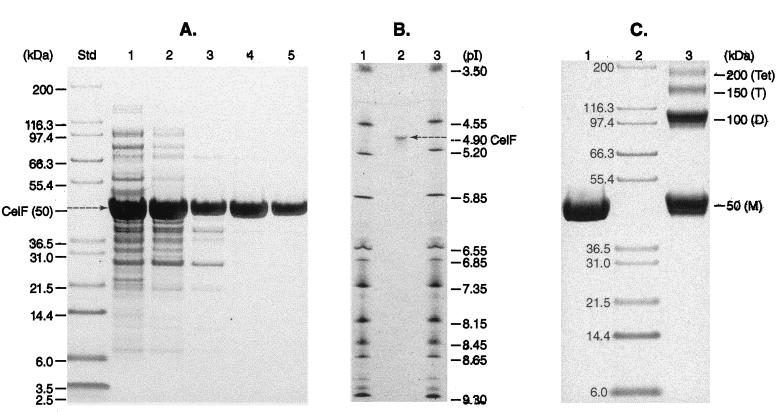

Purification of CelF was achieved by conventional low-pressure chromatography, using 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) supplemented with 1 mM Mn2+ and 0.1 mM NAD+. The five-stage procedure yielded approximately 135 mg of purified enzyme from 55 g (wet weight) of cells, but disturbingly, the specific activity of the final preparation (∼1.8 U/mg) was only twofold greater than that of the original high-speed supernatant (∼0.9 U/mg). Although purified in active form, CelF is clearly (and progressively) inactivated during purification. Analysis of the purified enzyme by SDS-PAGE revealed a single polypeptide of ∼50,000 Mr (Fig. 1A, lane 5). Analytical electrofocusing of CelF also revealed a single diffuse polypeptide (Fig. 1B, lane 2), but the experimentally determined pI of ∼4.9 was considerably lower than the theoretical pI (6.34) calculated from the amino acid composition. The results of cross-linking experiments provided evidence of the oligomeric structure of CelF (Fig. 1C, lane 3), and a single high-molecular-weight tetrameric species (Mr, ∼210,000) was detected by fast protein liquid chromatography gel filtration (data not shown). Microsequencing provided evidence of enzyme homogeneity, and (except for the terminal methionine residue) the unambiguous sequence of the first 30 amino acids from the N terminus agreed precisely with that expected from translation of celF: SQKLKVVTIGGGSSYTPELLEGFIKRYHEL. The Mr of 50,386 for CelF obtained by electrospray-mass spectrometry was less than the calculated molecular weight of the full-length polypeptide (50,512) by the mass equivalence of one methionine residue.

FIG. 1.

Determination of the Mr, pI, and structural composition of purified CelF by analytical PAGE. (A) Samples from each of the five stages of enzyme purification were denatured, resolved by SDS-PAGE (4 to 12% acrylamide; Bis-Tris gel), and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lane 1, high-speed supernatant; lane 2, DEAE Tris-Acryl M; lane 3, phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B; lane 4, Ultrogel AcA-44; and lane 5, purified CelF (Mr, ∼50,000; ∼8 μg) from Blue Tris-Acryl. Also shown are Novex Mark 12 molecular weight markers (Std). (B) Determination of the pI of CelF (∼4.9) by analytical electrofocusing. Approximately 1 μg of enzyme was applied directly to the surface of the isoelectric focusing gel in lane 2 and protein standards (pI range, 3.5 to 9.3; Pharmacia) in lanes 1 and 3. (C) Cross-linking of the subunits of native CelF by dimethyl adipimidate (DMA). A mixture containing ∼40 μg of CelF and ∼200 μg of DMA was prepared in 20 μl of 0.1 M triethanolamine buffer (pH 8). After 2 h of incubation at room temperature, 10 μl of the sample was denatured and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (lane 3). M, D, T, and Tet, monomer, dimer, trimer, and tetrameric species, respectively. Denatured monomer (control; no DMA) and molecular weight markers are shown in lanes 1 and 2, respectively.

Assay of CelF activity in vitro.

Addition of either the ultracentrifugal cell extract of E. coli PEP24(pUF4000) or purified CelF to assays containing both Mn2+ ion and NAD+ elicited immediate hydrolysis of pNPβG6P (ca. 1 to 2 μmol of pNP formed min−1 mg−1). Omission of the nucleotide markedly reduced the rate of enzyme activity, and in an Mn2+-free system pNPβG6P hydrolysis ceased within ∼2 min. Preincubation in an assay lacking both a metal ion and nucleotide resulted in complete loss of CelF activity. Properties similar to those we report for CelF of E. coli have also been described for other family 4 glycosylhydrolases, including maltose 6-phosphate hydrolases from F. mortiferum (MalH [39]) and B. subtilis (GlvA [40]), respectively, α-galactosidase from E. coli (6), and α-glucosidase from Thermotoga maritima (17a). In the case of GlvA, loss of activity in the absence of a metal ion was in part attributable to dissociation of the Mn2+-stabilized active tetramer to a metal-free, inactive dimeric state (40). Accordingly, ultracentrifugal sedimentation velocity analysis was used to further characterize the apo and Mn2+ forms of CelF. In the presence of Mn2+ ion, a single monodisperse sedimenting boundary of solute was observed, but in solutions lacking Mn2+ ion a minor component comprising up to 13% of total solute (sedimentation coefficients [s20,w], ∼2 to 4 S) was also detected. This lower-molecular-weight fraction may represent a degradation product of the less conformationally stable apoenzyme. The major fraction of the enzyme existed as a single species of 8.7 ± 0.2 S for the metal-free form and 8.9 ± 0.2 S for the Mn2+-containing form. The tetrameric structure of CelF was confirmed by sedimentation equilibrium experiments conducted at three protein concentrations. A single component (Mr = 202,000 ± 5%) was found for both metal-free and Mn2+-associated forms of CelF. The rapid loss of activity of CelF upon dilution in the Mn2+-free assay mixture cannot simply be attributed to tetramer dissociation but may result from conformational changes within the oligomeric structure (or active site) of the enzyme. In their studies of the instability of α-galactosidase from E. coli, Burstein and Kepes in 1971 proposed that dilution played a role in enzyme inactivation (6). In this context (see below), activity of a concentrated preparation of CelF was maintained after dialysis against Mn2+-free 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5).

Metal ion and nucleotide specificity.

In the standard assay, the activity of CelF was greatest within the temperature range of 34 to 38°C. CelF activity was not significantly affected by the buffer species, and within a pH range of 7.0 to 8.0, comparable rates of pNPβG6P hydrolysis were measured in BES {2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]ethanesulfonic acid}-, TES [N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid]-, HEPES-, or Tricine-buffered assays. To determine the specificity with respect to metal and nucleotide requirements, a concentrated preparation of CelF (35 mg ml−1) was first dialyzed against 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5). Enzyme activity was then determined in assays containing different metal ions in combination with NAD+ (Table 1). Mn2+, Co2+, and Ni2+ enhanced the activity of CelF, and for these ions, the presence of NAD+ increased the rate of pNPβG6P hydrolysis by 2- to 20-fold. Other divalent metals, including Mg2+, Ca2+, Sr2+, and Zn2+, had little effect upon the activity of CelF either singly or in combination with the nucleotide. The concentrations of Me2+ and NAD+ required for optimum activity of CelF were determined to be 1 and 0.1 mM, respectively (data not shown). Of a variety of nucleotides tested, including NAD+, 3-acetylpyridine adenine dinucleotide, nicotinamide mononucleotide, NADP+, NADPH, NADPH (deamino), NAD+ (deamido), and NAD+ (bis dialdehyde), only NAD+ activated CelF.

TABLE 1.

Metal ion specificity and NAD+ requirement for activity of CelF

| Addition to assaya | Specific activityb |

|---|---|

| Control (no addition) | 0.017 |

| Mn2+ | 0.249 |

| Mn2+ + NAD+ | 1.155 |

| Ni2+ | 0.042 |

| Ni2+ + NAD+ | 0.880 |

| Co2+ | 0.197 |

| Co2+ + NAD+ | 0.292 |

| Mg2+ | NDc |

| Mg2+ + NAD+ | 0.065 |

| Sr2+ | ND |

| Sr2+ + NAD+ | 0.061 |

| Ca2+ | ND |

| Ca2+ + NAD+ | 0.048 |

The 2-ml assay mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and, when required, 1 mM appropriate divalent metal ion, 1 mM NAD+, and 0.38 mg of dialyzed CelF. After 5 min of preincubation at 37°C, the substrate (pNPβG6P) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM.

Expressed as micromoles of pNPβG6P hydrolyzed minute−1 milligram of enzyme−1.

ND, no detectable activity.

Substrate specificity of CelF.

Substrates hydrolyzed by CelF, and the relevant kinetic parameters, are presented in Table 2. In the presence of Mn2+ ion and NAD+, the enzyme hydrolyzed all P-β-glucosides tested. There was no detectable cleavage of the corresponding nonphosphorylated compounds (data not shown). Although exacting with respect to the presence of the glucopyranosyl-6P moiety and O-β glycosidic linkage, CelF enzyme is tolerant of wide variation in the structure and composition of the aglycone substituent of its substrates. The importance of the equatorial position of the C-4 OH group for pNPαG6P cleavage is evident from the fact that epimeric pNPβGal6P (axial -OH at C-4) was not hydrolyzed by the enzyme. Spectrophotometric analyses showed that CelF catalyzed the hydrolysis of 0.05 μmol of cellobiose-6P to yield 0.05 μmol each of G6P and glucose. No evidence was obtained for reduction of NAD+ during cellobiose-6P cleavage.

TABLE 2.

Substrate specificity and kinetic parameters of purified CelF

| P-β-glucoside | Km (mM) | Vmax (μmol min−1 mg−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 4MUβG6P | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 3.35 ± 0.08 |

| Arbutin-6Pa | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 2.13 ± 0.08 |

| pNPβG6P | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 1.33 ± 0.05 |

| Salicin-6Pb | 0.44 ± 0.09 | 1.38 ± 0.09 |

| Cellobiose-6P | 1.30 ± 0.09 | 1.74 ± 0.05 |

| MethylβG6P | 2.22 ± 0.21 | 0.56 ± 0.03 |

| Gentiobiose-6Pc | 12.50 ± 1.26 | 1.11 ± 0.11 |

4-hydroxyphenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside-6P.

O-hydroxy-methylphenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside-6P.

6-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-d-glucopyranose-6P.

Relationship of CelF to other family 4 members.

The amino acid sequence of CelF (P17411) was used as a probe to search the nonredundant protein sequence database with the Gapped BLAST programs (1). Nine homologs were identified: CelF of B. subtilis (P46320; a putative 6-phospho-β-glucosidase), a putative glucosidase of Streptomyces coelicolor (AL031107), MalH of F. mortiferum (O06901; 6-phospho-α-glucosidase), GlvA of B. subtilis (P54716; 6-phospho-α-glucosidase), GlvG of E. coli (P31450; truncated 6-phospho-α-glucosidase), a putative α-galactosidase of B. subtilis (O34645), MelA of E. coli (P06720; α-galactosidase), a putative hydrolase of B. subtilis (Z99107), and AglA of T. maritima (O33830; α-glucosidase). CelF was also used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information database of the unpublished sequences of incomplete microbial genomes, and six additional protein homologs were identified: one from Salmonella typhi contig 679 (Sanger Centre), one from Yersinia pestis contig 792 (Sanger Centre), one from Enterococcus faecalis gef 6229 (The Institute for Genomic Research), one from Vibrio cholerae serotype O1 (The Institute for Genomic Research), and two from Clostridium acetobutylicum (contigs 139I and 186I [Genome Therapeutics Corp.]). The 16 protein sequences were first aligned by the program CLUSTAL X (41, 42), and the resulting alignment was used to construct a neighbor-joining (distance) tree (Fig. 2). Family 4 comprises three subgroups of glycosylhydrolases (all of bacterial origin), including (I) phospho-β-glucosidases, (II) phospho-α-glucosidases, and (III) α-glycosidases. At least one enzyme from each group has been purified in active form.

Stereospecificity of family 4 glycosylhydrolases.

More than 60 sequence-based families of glycosylhydrolases have been established (13, 14), and this information is accessible from the World Wide Web (36a). A fundamental property of sequence-based classification of glycosylhydrolases is the predictability of stereochemical specificity (α or β linkage in substrates) and molecular mechanism (inversion or retention) for all members of a particular family (7, 14, 20). Prior to the purification and characterization of CelF, only α-glycosidase activities had been described for members of family 4, including α-galactosidase (6, 18, 22), α-glucosidase (17a), and the two P-α-glucosidases (5, 40). With the addition of CelF, family 4 now contains both α- and β-glycoside-specific enzymes. In this context, family 4 is the exception among the glycosylhydrolase families, whose members invariably display either α or β specificity (see Tables 1 in references 14 and 20).

Catalytic mechanism(s) of family 4 glycosylhydrolases.

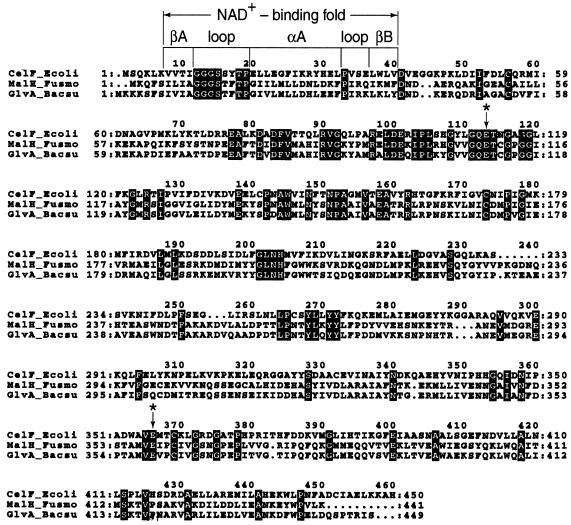

Substrate cleavage by glycosylhydrolases occurs via one of two catalytic mechanisms that proceed with either inversion or retention of configuration at the anomeric center (7, 20, 36, 44, 47, 48). It is believed that the same mechanism is used by all members of a given family. The catalytic mechanism for members of family 4 has not yet been determined, but results obtained by site-directed mutagenesis of GlvA from B. subtilis identify Glu111 and Glu359 as the probable proton donor and nucleophile or base, respectively (40). Comparative alignment of amino acid sequences (Fig. 3) shows that the two catalytic residues and the putative NAD+-binding domain of GlvA (P-α-glucosidase) are also positionally conserved in CelF (P-β-glucosidase) and MalH (P-α-glucosidase). Crystallographic data obtained from other glycosylhydrolases suggests that for “retaining” enzymes, the average distance between the carboxylate moieties of the two catalytic residues is 4.8 to 5.3 Å. For those enzymes in which hydrolysis proceeds with “inversion,” the carboxylate groups are usually 9.0 to 9.5 Å apart (20, 45). We have recently reported the crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of GlvA (43), and crystallization trials for CelF are in progress (43a). Solution of the structures of GlvA and CelF will confirm (or refute) the active-site location for the two glutamyl residues, and their distance of separation may establish the catalytic mechanism(s) for the two P-glycosylhydrolases. It will be of interest to learn if CelF and GlvA use the same mechanism or whether family 4 of the glycosylhydrolase superfamily is exceptional in containing both inverting and retaining enzymes.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the three enzymes from family 4 that have been purified and characterized: CelF (P-β-glucosidase from E. coli [this study]), MalH (P-α-glucosidase; F. mortiferum [5]), and GlvA (P-α-glucosidase; B. subtilis [40]). Identical residues are highlighted, and putative catalytic residues are marked by asterisks. The numbers to the left and right denote residue positions, and the numbers above the residues refer to alignment positions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Saul Roseman, Nemat Keyhani, Edith Wolff, and Jack London for their interest and helpful discussions. We thank Nga Nguyen and Lewis Pannell for providing microsequence and mass spectrometry data, respectively. We acknowledge the assistance of Ann Ginsburg in analysis and interpretation of sedimentation data and thank Jack Folk for the synthesis of chromogenic and fluorogenic substrates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amster-Choder O, Houman F, Wright A. Protein phosphorylation regulates transcription of the β-glucoside utilization operon in E. coli. Cell. 1989;58:847–855. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Short protocols in molecular biology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouma C L, Reizer J, Reizer A, Robrish S A, Thompson J. 6-Phospho-α-d-glucosidase from Fusobacterium mortiferum: cloning, expression, and assignment to family 4 of the glycosylhydrolases. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4129–4137. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4129-4137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burstein C, Kepes A. The α-galactosidase from Escherichia coli K12. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;230:52–63. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(71)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies G, Henrissat B. Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. Structure. 1995;3:853–859. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Hassouni M, Henrissat B, Chippaux M, Barras F. Nucleotide sequences of the arb genes, which control β-glucoside utilization in Erwinia crysanthemi: comparison with the Escherichia coli bgl operon and evidence for a new β-glycosylhydrolase family including enzymes from eubacteria, archeabacteria, and humans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:765–777. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.765-777.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox C F, Wilson G. The role of a phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent kinase system in β-glucoside catabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;59:988–995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.3.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall B G, Betts P W, Kricker M. Maintenance of the cellobiose utilization genes of Escherichia coli in a cryptic state. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:389–402. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall B G, Xu L. Nucleotide sequence, function, activation, and evolution of the cryptic asc operon of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:688–706. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrissat B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1991;280:309–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1993;293:781–788. doi: 10.1042/bj2930781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henrissat B, Davies G. Structural and sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:637–644. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keyhani N O, Roseman S. Wild-type Escherichia coli grows on the chitin disaccharide, N,N′-diacetylchitobiose, by expressing the cel operon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14367–14371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kricker M, Hall B G. Directed evolution of cellobiose utilization in Escherichia coli K12. Mol Biol Evol. 1984;1:171–182. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kricker M, Hall B G. Biochemical genetics of the cryptic gene system for cellobiose utilization in Escherichia coli K12. Genetics. 1987;115:419–429. doi: 10.1093/genetics/115.3.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Liebl, W., et al. Personal communication.

- 18.Liljeström P L, Liljeström P. Nucleotide sequence of the melA gene, coding for α-galactosidase in Escherichia coli K12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;5:2213–2220. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahadevan S, Reynolds A E, Wright A. Positive and negative regulation of the bgl operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2570–2578. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2570-2578.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarter J D, Withers S G. Mechanisms of enzymatic glycoside hydrolysis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1994;4:885–892. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(94)90271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meadow N D, Fox D K, Roseman S. The bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate: glycose phosphotransferase system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:497–542. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.002433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagao Y, Nakada T, Imoto M, Shimamoto T, Sakai S, Tsuchiya T. Purification and analysis of the structure of α-galactosidase from Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;151:236–241. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmer R E, Anderson R A. Cellobiose metabolism in Aerobacter aerogenes. II. Phosphorylation of cellobiose with adenosine 5′-triphosphate by a β-glucoside kinase. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:3415–3419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker L L, Hall B G. A fourth Escherichia coli gene system with the potential to evolve β-glucoside utilization. Genetics. 1988;119:485–490. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.3.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker L L, Hall B G. Characterization and nucleotide sequence of the cryptic cel operon of Escherichia coli K12. Genetics. 1990;124:455–471. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.3.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker L L, Hall B G. Mechanisms of activation of the cryptic cel operon of Escherichia coli K12. Genetics. 1990;124:473–482. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Postma P W, Lengeler J W, Jacobson G R. Phosphoenolpyruvate: carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:543–594. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.543-594.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad I, Schaefler S. Regulation of the β-glucoside system in Escherichia coli K12. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:638–650. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.2.638-650.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prasad I, Young B, Schaefler S. Genetic determination of the constitutive biosynthesis of phospho-β-glucosidase A in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1973;114:909–915. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.3.909-915.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reizer J, Reizer A, Saier M H., Jr The cellobiose permease of Escherichia coli consists of three proteins and is homologous to the lactose permease of Staphylococcus aureus. Res Microbiol. 1990;141:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(90)90079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Reversible Associations in Structural and Molecular Biology RASNB Website. 6 November 1996. [Online.] http://www.bbri.org/RASMB/rasmb.html. [20 September 1999, last date accessed.]

- 31.Reynolds A E, Felton J, Wright A. Insertion of DNA activates the cryptic bgl operon in E. coli K12. Nature. 1981;293:625–629. doi: 10.1038/293625a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saier M H, Jr, Reizer J. Proposed uniform nomenclature for the proteins and protein domains of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1433–1438. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1433-1438.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnetz K, Rak B. Regulation of the bgl operon of Escherichia coli by transcriptional antitermination. EMBO J. 1988;7:3271–3277. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnetz K, Toloczyki C, Rak B. β-Glucoside (bgl) operon of Escherichia coli K-12: nucleotide sequence, genetic organization, and possible evolutionary relationship to regulatory components of two Bacillus subtilis genes. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2579–2590. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2579-2590.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinnott M L. Catalytic mechanisms of enzymic glycosyl transfer. Chem Rev. 1990;90:1171–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 36a.SWISS-PROT Protein Sequence Data Bank Website. Release 38.0, July 1999. [Online.] http://www.expasy.ch/cgi-bin/lists?glycosid.txt. [20 September 1999, last date accessed.]

- 37.Swofford D L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 3.1. Champaign, Ill: Illinois Natural History Survey; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swofford D L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 4.0. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson J, Gentry-Weeks C R, Nguyen N Y, Folk J E, Robrish S A. Purification from Fusobacterium mortiferum ATCC 25557 of a 6-phosphoryl-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl:6-phosphoglucohydrolase that hydrolyzes maltose-6-phosphate and related phospho-α-d-glucosides. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2505–2512. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2505-2512.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson J, Pikis A, Ruvinov S B, Henrissat B, Yamamoto H, Sekiguchi J. The gene glvA of Bacillus subtilis 168 encodes a metal-requiring, NAD(H)-dependent 6-phospho-α-glucosidase: assignment to Family 4 of the glycosylhydrolase superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27347–27356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The CLUSTAL-X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varrot A, Yamamoto H, Sekiguchi J, Thompson J, Davies G J. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of the 6-phospho-α-glucosidase from Bacillus subtilis. Acta Crystallogr. 1999;D55:1212–1214. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999003790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43a.Varrot, A., et al. Unpublished data.

- 44.White A, Rose D R. Mechanism of catalysis by retaining β-glycosyl hydrolases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:645–651. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiesmann C, Hengstenberg W, Schulz G E. Crystal structures and mechanism of 6-phospho-β-galactosidase from Lactococcus lactis. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:851–860. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson G, Fox C F. The β-glucosidase system of Escherichia coli. IV. Purification and properties of phospho-β-glucosidases A and B. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:5586–5598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Withers S G, Aebersold R. Approaches to labelling and identification of active site residues in glycosidases. Protein Sci. 1995;4:361–372. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Withers S G, Warren R A J, Street I P, Rupitz K, Kempton J B, Aebersold R. Unequivocal demonstration of the involvement of a glutamate residue as a nucleophile in the mechanism of a “retaining” glycosidase. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5887–5889. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witt E, Frank R, Hengstenberg W. 6-Phospho-β-galactosidases of Gram-positive and 6-phospho-β-glucosidase B of Gram-negative bacteria: comparison of structure and function by kinetic and immunological methods and mutagenesis of the lacG gene of Staphylococcus aureus. Protein Eng. 1993;6:913–920. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.8.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zamyatnin A A. Amino acid, peptide and protein volume in solution. Annu Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1984;13:145–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.13.060184.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]