Summary

Meningiomas are the most common primary intracranial tumors1–3. Treatments for patients with meningiomas are limited to surgery and radiotherapy, and systemic therapies remain ineffective or experimental4,5. Resistance to radiotherapy is common in high-grade meningiomas6, and the cell types and signaling mechanisms driving meningioma tumorigenesis or resistance to radiotherapy are incompletely understood. Here we report NOTCH3 drives meningioma tumorigenesis and resistance to radiotherapy and find NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells are conserved across meningiomas from humans, dogs, and mice. NOTCH3+ cells are restricted to the perivascular niche during meningeal development and homeostasis and in low-grade meningiomas but are expressed throughout high-grade meningiomas that are resistant to radiotherapy. Integrating single-cell transcriptomics with lineage tracing and imaging approaches across mouse genetic and xenograft models, we show NOTCH3 drives tumor initiating capacity, cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and resistance to radiotherapy to increase meningioma growth and reduce survival. An antibody stabilizing the extracellular negative regulatory region of NOTCH37,8 blocks meningioma tumorigenesis and sensitizes meningiomas to radiotherapy, reducing tumor growth and improving survival in preclinical models. In summary, our results identify a conserved cell type and signaling mechanism that underlie meningioma tumorigenesis and resistance to radiotherapy, revealing a new therapeutic vulnerability to treat meningiomas that are resistant to standard interventions.

Meningiomas arising from the meningothelial lining of the central nervous system comprise more than 40% of primary intracranial tumors1–3, and approximately 1% of humans will develop a meningioma in their lifetime9. The World Health Organization (WHO) grades meningiomas according to histological features such as mitotic count and rare molecular alterations that are associated with poor outcomes3. Surgery and radiotherapy are the mainstays of meningioma treatment10, and most WHO grade 1 meningiomas can be effectively treated, but many grade 2 or grade 3 meningiomas are resistant to treatment and cause neurological morbidity and mortality4. All clinical trials of systemic therapy have failed to block meningioma growth or improve patient survival4,5, and conserved mechanisms underlying aggressive meningiomas remain elusive.

Recent bioinformatic investigations have shed light on meningioma biology, revealing molecular groups of tumors with distinct clinical outcomes that provide a framework for investigating meningioma resistance to treatment11–18. Merlin-intact meningiomas encoding the tumor suppressor NF2 on chromosome 22q are often low-grade, have favorable clinical outcomes, and are sensitive to cytotoxic treatments such as radiotherapy11. Meningiomas with biallelic inactivation of NF2 are often high-grade, have poor clinical outcomes, and can be resistant to radiotherapy13. Cancer stem cells can mediate resistance to radiotherapy19, but the cell types and signaling mechanisms driving tumorigenesis or resistance to treatment across molecular groups of meningiomas are unknown. Morphologic correlates between meningioma cells and arachnoid cap cells found on meningeal invaginations of dural venous sinuses have fueled a longstanding hypothesis that meningiomas may arise from arachnoid cap cells20,21. However, the WHO recognizes 15 histological variants of meningiomas3, some of which do not resemble arachnoid cap cells, or which may develop far from dural venous sinuses, including cases of primary intraparenchymal, intraventricular, or pulmonary meningiomas22–24. These data suggest additional cell types may contribute to meningioma tumorigenesis, and that understanding cell types and signaling mechanisms underlying meningioma tumorigenesis or resistance to radiotherapy may reveal new targets for systemic therapies to treat patients with meningiomas.

NOTCH3 is enriched in meningioma mural cells and is expressed throughout high-grade meningiomas

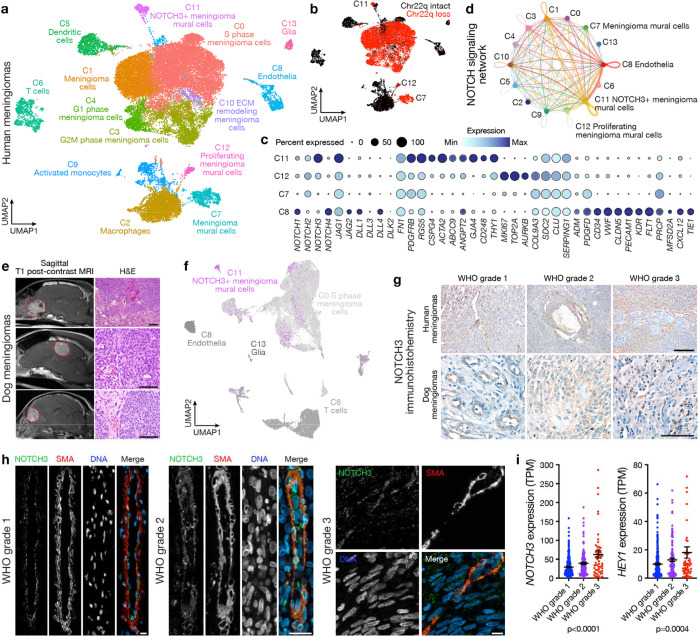

To elucidate the cellular architecture of meningiomas with poor clinical outcomes, single-cell RNA sequencing was performed on 30,934 cells from 6 human meningioma samples with biallelic inactivation of NF2, including loss of at least 1 copy of chromosome 22q (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Datasets were integrated and corrected for batch effects using Harmony25 (Extended Data Fig. 1b), and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) revealed a total of 13 cell clusters that were defined using automated cell type classification26, cell signature gene sets27, cell cycle analysis, and differentially expressed cluster marker genes (Supplementary Table 1). Reduced dimensionality clusters of meningioma tumor cells with loss of chromosome 22q were distinguished from microenvironment cells using CONICS28 (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1c). Meningioma cell clusters expressing markers of cell cycle progression (C0, C3, C4), signal transduction (C1), or extracellular matrix remodeling (C10) grouped together in UMAP space (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1d–g, and Supplementary Table 1). Three meningioma cell clusters with loss of chromosome 22q were distinguished from other meningioma cell types by expression of mural cell markers (C7, C11, C12), including genes associated with pericytes (CD248, ABCC9, CSPG4, GJA4), fibroblasts (SERPING1, CLU), smooth muscle cells (SDC2, ACTA2), and multiple mural cell lineages (PDGRFB, RGS5)29–31 (Fig. 1a–c, Extended Data Fig. 1f, and Supplementary Table 1). The cluster of cells expressing endothelial markers (C8), including genes associated with tip cells (ADM, ANGPT2, COL9A3), capillary cells (MFSD2A), arterial cells (CXCL12), and multiple endothelial cell lineages (CD34, VWF, CLDN5, PECAM1, PDGFD, KDR, FLT, FLT1, TIE1)29–31, did not show loss of chromosome 22q (Fig. 1a–c, Extended Data Fig. 1f, and Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1. NOTCH3 is enriched in meningioma mural cells and is expressed throughout high-grade meningiomas.

a, Single-cell RNA sequencing UMAP of 30,934 transcriptomes from human meningioma samples with loss of chromosome 22q showing tumor cell states and microenvironment cell types. b, UMAP showing single-cell RNA sequencing of human meningiomas shaded by chromosome 22q status. c, Dot plot showing expression of NOTCH receptors (NOTCH1, NOTCH2, NOTCH3, NOTCH3), NOTCH ligands (JAG1, JAG2, DLL1, DLL3, DLL4, DLK2, FN1), mural cell markers (PDGFRB, RGS5, CSPG4, ACTA2, ABCC9, ANGPT2, GJA4, CD248, COL9A3, SDC2, CLU, SERPING1), cancer stem-cell marker (NOTCH3, THY1), cell proliferation markers (MKI67, TOP2A, AURKB), and endothelial cells markers (ADM, PDGFD, CD34, VWF, CLDN5, PECAM1, KDR, FLT1, PRCP, MFSD2A, CXCL12, TIE1) across meningioma mural (C7, C11, C12) or endothelial cells (C8) from a. d, Inference of NOTCH signaling network in human meningiomas using single-cell RNA sequencing cell-cell communication analysis. e, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, left) or H&E images (right) of spontaneous dog meningiomas. Scale bars, 100μm. f, Transcriptomic concordance of human meningioma single-cell cluster identities from a projected on single-cell RNA sequencing UMAP of 40,525 transcriptomes from dog meningioma samples showing NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells and proliferating meningioma cells are conserved across human and dog meningiomas. g, IHC for NOTCH3 across histological grades of human (top) or dog (bottom) meningiomas. Representative of n=3–10 meningiomas per grade. Scale bars, 100μm. h, IF for NOTCH3 and the mural cell marker SMA across histological grades of human meningiomas. DAPI marks DNA. Representative of n=10 meningiomas per grade. Scale bars, 10μm. i, Quantification of NOTCH3 or the NOTCH3 target gene HEY1 across meningioma grades using RNA sequencing of n=502 human meningiomas. TPM, transcripts per million. Lines represent means and error bars represent standard error of means. ANOVA.

Meningioma mural cell clusters were distinguished from one another by expression of markers of cell cycle progression (MKI67, TOP2A, AURKB) or markers of cancer stem cells (NOTCH3, THY1)32–34 (Fig. 1c). The cluster of meningioma mural cells that was enriched in NOTCH3 and THY1 (C11), and the endothelial cell cluster (C8), also expressed NOTCH ligands (JAG1, JAG2, DLL1, DLL4, FN1) (Fig. 1c). Cell-cell communication analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data using CellChat35 suggested the NOTCH signaling network was active in meningiomas with loss of chromosome 22q, particularly among and between NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells and endothelia (Fig. 1d). Moreover, NOTCH3 was expressed in meningioma cell clusters marked by the meningioma gene SSTR2A36 (Extended Data Fig. 1h) but other NOTCH receptors were not enriched in meningioma cell types (Supplementary Table 1).

The evolutionarily conserved NOTCH family of transmembrane proteins enable intercellular communication to regulate mammalian cell fate and growth37–39. Similar to humans, the most common primary intracranial tumors in dogs are meningiomas40. Thus, to determine if NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells were conserved in meningiomas from other mammals, single-cell RNA sequencing was performed on 40,525 cells from 5 samples from dog meningiomas (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 2a). Datasets were integrated and corrected for batch effects using Harmony25 (Extended Data Fig. 2b), and UMAP revealed a total of 14 cell clusters that were defined using automated cell type classification26, cell signature gene sets27, cell cycle analysis (Extended Data Fig. 2c), and differentially expressed cluster marker genes (Extended Data Fig. 2d–f and Supplementary Table 2). Human meningioma single-cell cluster identities were projected onto reduced dimensionality clusters of dog meningioma cells using transcriptional correlation and expression of conserved marker genes across species, revealing conservation of endothelia, glia, and immune cell types (Fig. 1f). NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells from human meningiomas were found in a unique dog meningioma cluster of mural cells and a mixed cluster that was also comprised of cycling meningioma cells from human meningiomas (Fig. 1f). These data suggest NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells are conserved in mammalian meningiomas. In support of this hypothesis, immunohistochemistry (IHC) for NOTCH3 across all grades of human or dog meningiomas showed NOTCH3 was heterogeneous and predominantly restricted to the perivascular niche in low-grade meningiomas but was expressed throughout high-grade meningiomas from both species (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 3). Immunofluorescence (IF) across all grades of human meningiomas demonstrated that NOTCH3 was expressed by mural cells marked by SMA and was enriched throughout high-grade meningiomas but was not expressed by endothelial cells marked by VWF (Fig. 1h and Extended Data Fig. 4–9). RNA sequencing of 502 human meningiomas11,13 showed that expression of NOTCH3 and the NOTCH3 target gene HEY1 increased from WHO grade 1 (n=329) to grade 2 (n=117) to grade 3 (n=56) meningiomas.

NOTCH3+ mural cells underlie meningeal tumorigenesis

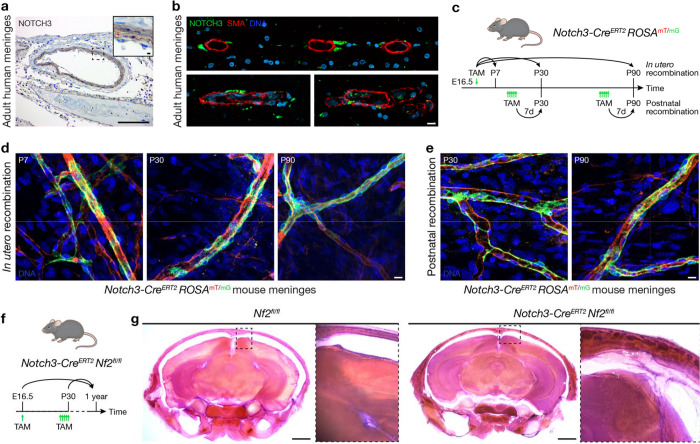

NOTCH3 mutations in humans cause CADASIL41, a hereditary adult-onset cerebral arteriopathy associated with sub-cortical ischemic events and alterations in brain vascular smooth muscle cells42. The functional relevance of NOTCH3 for meningeal development, homeostasis, or tumorigenesis is unknown. IF of the developing human cortex from gestational week 17 showed NOTCH3 was expressed by mural cells marked by PDGFRβ in the cortical plate and margin zone (Extended Data Fig. 10a), both of which contribute to meningeal development43–46. Re-analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data from perinatal human brain vasculature (139,134 cells from gestational weeks 15, 17, 18, 20, 22, and 23)29 or adult human brain vasculature (84,138 cells or 52,023 cells from 2 studies)30,31 demonstrated NOTCH3 was enriched in mural cells marked by PDGFRβ or ACTA2 (SMA) (Extended Data Fig. 10b–d). In contrast to NOTCH3 expression in brain vasculature and meningioma mural cells (Fig. 1c), IHC and IF of adult human meninges showed NOTCH3 expression was restricted to mural cells that were adjacent abut non-overlapping with vascular smooth muscle cells expressing SMA (Fig. 2a, b). Thus, NOTCH3+ mural cells in the brain (Extended Data Fig. 10a–d), meninges (Fig. 2a, b), and meningiomas (Fig. 1 and Extended Data 1–9) have partially overlapping gene and protein expression programs, suggesting these cell types may fulfill different functions during development, homeostasis, or tumorigenesis.

Fig. 2. NOTCH3+ mural cells underly meningeal tumorigenesis.

a, IHC for NOTCH3 in the adult human meninges showing expression is restricted to mural cells. Representative of n=3 biological replicates. Scale bars, 100μm and 10μm (insert). b, IF for NOTCH3 and the mural cell marker SMA in 3 adult human meningeal samples showing NOTCH3 is expressed in mural cells adjacent to smooth muscle cells in the meninges. DAPI marks DNA. Scale bar, 10μm. c, Experimental design for in vivo lineage tracing of NOTCH3+ mural cells during meningeal development (in utero recombination) or homeostasis (postnatal recombination). TAM, tamoxifen. d, Confocal microscopy of whole mount mouse convexity meningeal samples at P7, P30, or P90 after in utero recombination of the ROSAmT/mG allele showing NOTCH3 cells (green) are restricted to the perivascular niche during meningeal development. Representative of n=3 biological replicates per timepoint. DAPI marks DNA. Scale bar, 10μm. e, Confocal microscopy of whole mount mouse convexity meningeal samples at P30 or P90 after postnatal recombination of the ROSAmT/mG allele showing NOTCH3+ cells (green) are restricted to the perivascular niche during meningeal homeostasis. Representative of n=3 biological replicates per timepoint. DAPI marks DNA. Scale bar, 10μm. f, Experimental design for in vivo biallelic inactivation of Nf2 in NOTCH3+ cells during meningeal development (E16.5) or homeostasis (P30). Mice were monitored for 1 year after Nf2 inactivation. g, Coronal H&E images of 300μm decalcified mouse skull sections 1 year after treatment of mice with TAM. No gross tumors were identified, but insets show Nf2 inactivation in NOTCH3+ cells is associated with meningeal hyperproliferation after either in utero (E16.5) or postnatal (P30) treatment with TAM. Representative of n=5–8 biological replicates per condition. Scale bars 1mm.

To determine if NOTCH3+ cells give rise to other cell types during meningeal development or homeostasis, a tamoxifen-inducible Notch3-CreERT2 allele47 was combined with the global double-fluorescent ROSAmT/mG Cre reporter allele48 (Fig. 2c). Fluorophore recombination was induced during meningeal development (E16.5) or homeostasis (P30, P90) and confocal microscopy of whole mount mouse meningeal samples revealed NOTCH3+ cells were restricted to the perivascular niche across all contexts (Fig. 2d, e). To determine if NOTCH3+ cells underlie meningeal tumorigenesis, the Notch3-CreERT2 allele was combined with Nf2fl/fl alleles for conditional biallelic inactivation of the Nf2 tumor suppressor in mice49. Nf2 was inactivated in NOTCH3+ cells in utero (E16.5) or in adulthood (P30), and mice were monitored without evidence of neurological symptoms or other phenotypes for 1 year (Fig. 2f). Morphologic examination of the central nervous system revealed meningeal hyperproliferation after biallelic inactivation of Nf2 in NOTCH3+ cells compared to mice with intact Nf2 (Fig. 2g). These data support the hypothesis that NOTCH3+ mural cells underlie meningeal tumorigenesis but do not contribute to meningeal self-renewal (Fig. 2d, e), suggesting that beyond being a marker of meningioma initiation, NOTCH3 may represent a therapeutic vulnerability to treat meningiomas that are resistant to standard interventions.

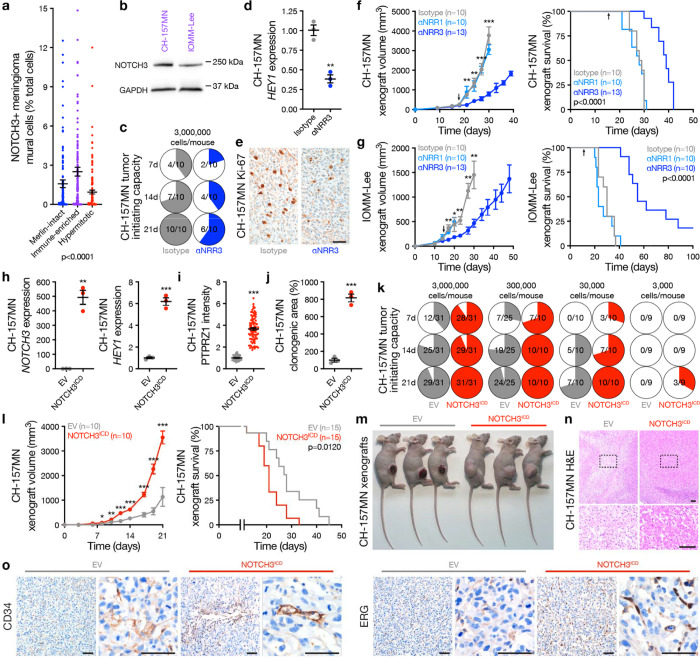

NOTCH3 signaling drives meningioma tumor initiating capacity, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis

To identify reagents for mechanistic and functional interrogation of NOTCH3 signaling in the context of meningioma tumorigenesis, reference transcriptomic signatures of human meningioma single-cell clusters (Fig. 1a) were used to estimate the proportion of NOTCH3 meningioma mural cells across 502 human meningiomas with matched RNA sequencing and DNA methylation profiling11,13. DNA methylation profiling reveals meningiomas are comprised of Merlin-intact, Immune-enriched, and Hypermitotic molecular groups, and can identify meningioma cell lines that are representative of each group11. Immune-enriched meningiomas are distinguished from other molecular groups by hypomethylation of genes involved in vasculature development11. Cell type deconvolution across meningioma DNA methylation groups showed Immune-enriched meningiomas (n=180) were enriched in NOTCH3 meningioma mural cells compared to Merlin-intact (n=176) or Hypermitotic meningiomas (n=146) (Fig. 3a) and immunoblots demonstrated NOTCH3 was expressed in CH-157MN50 and IOMM-Lee51 Immune-enriched meningioma cell lines (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. NOTCH3 signaling drives meningioma tumor initiating capacity, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis.

a, Deconvolution of NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells from Fig. 1a using human meningiomas with paired RNA sequencing and DNA methylation profiling (n=502). ANOVA. b, Immunoblots showing NOTCH3 is expressed in CH-157MN and IOMM-Lee Immune-enriched meningioma cell lines. c, In vivo tumor initiating capacity of CH-157MN meningioma cells in NU/NU mice ± αNRR3 IP injection 2 times per week. Denominators indicate number of mice at each time point. Numerators indicate number of mice with tumors at each time point. d, QPCR for the NOTCH3 target gene HEY1 from meningioma xenografts ± αNRR3 treatment for 2 weeks. Student’s t test. e, IHC for Ki-67 in meningioma xenografts showing αNRR3 blocks meningioma cell proliferation. Representative of n=3 xenografts per condition. Scale bar, 100μm. f, CH-157MN meningioma xenograft growth (left, student’s t tests) or survival (log-rank test). Arrows indicate initiation of bi-weekly treatment with the indicated therapy, which continued until death. g, IOMM-Lee meningioma xenograft growth (left, student’s t tests) or survival (log-rank test). Arrows as in f. h, QPCR for NOTCH3 or HEY1 in CH-157MN meningioma cells ± stable expression of empty vector (EV) or NOTCH3ICD. Student’s t tests. i, IF quantification of the stem cell marker PTPRZ1 in CH-157MN meningioma cells. Student’s t test. j, Clonogenic in vitro growth of CH-157MN meningioma cells after 2 weeks. Student’s t test. k, In vivo tumor initiating capacity of CH-157MN meningioma cells ± EV or NOTCH3ICD over limiting dilutions. Numerator and denominator as in c. l, CH-157MN meningioma xenograft growth (left, student’s t tests) or survival (log-rank test). m, Images of heterotopic meningioma xenografts showing macroscopic necrosis and ulceration in EV meningiomas. Representative of n=7–9 xenografts per condition. n, H&E low and high (box) magnification images of meningioma xenografts showing microscopic necrosis in EV meningiomas. Representative of n=3 xenografts per condition. Scale bars, 100μm. o, IHC for endothelia markers in meningioma xenografts showing NOTCH3ICD induces meningioma angiogenesis. Representative of n=3 xenografts per condition. Scale bars, 100μm. Lines represent means and error bars represent standard error of means. **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.0001.

NOTCH receptor activation requires ADAM protease cleavage of the extracellular negative regulatory region (NRR), intramembrane proteolysis by the γ-secretase complex, and release of the NOTCH intracellular domain (ICD) that regulates mammalian cell fate and growth37–39. Small molecule inhibitors of ADAM or γ-secretase do not distinguish between individual NOTCH receptors and have not been adopted in routine clinical practice due to toxicity, but antibody stabilization of the NRR allows for selective inhibition of individual NOTCH receptors in preclinical models7. An antibody selectively stabilizing the NRR of NOTCH3 (αNRR3)8 attenuated in vivo tumor initiating capacity (Fig. 3c), blocked expression of HEY1 (Fig. 3d), and reduced cell proliferation of CH-157MN xenografts (Fig. 3e). Moreover, αNRR3 blocked tumor growth and improved survival of CH-157MN (Fig. 3f) and IOMM-Lee xenografts (Fig. 3g) compared to isotype control treatment or treatment with αNRR1. Overexpression of the NOTCH3 ICD (NOTCH3ICD) increased expression of HEY1 and PTPRZ1, a marker of meningioma self-renewal52, and increased clonogenic growth of CH-157MN cells in vitro compared to CH-175MN cells expressing empty vector (EV) control (Fig. 3h–j). NOTCH3ICD increased the tumor initiating capacity of CH-157MN cells using in vivo limiting dilution assays (Fig. 3k), and increased tumor growth and reduced survival of CH-157MN xenografts compared to EV (Fig. 3l). Meningiomas are not protected by the blood brain barrier53, and heterotopic CH-157MN EV xenografts developed ulceration and necrosis that was not detected with overexpression of NOTCH3ICD (Fig. 3m, n), suggesting NOTCH3 may contribute to meningioma angiogenesis. In support of this hypothesis, immunostaining for endothelial cell markers (CD34, ERG) was increased in CH-157MN meningioma xenografts with overexpression of NOTCH3ICD compared to EV (Fig. 3o).

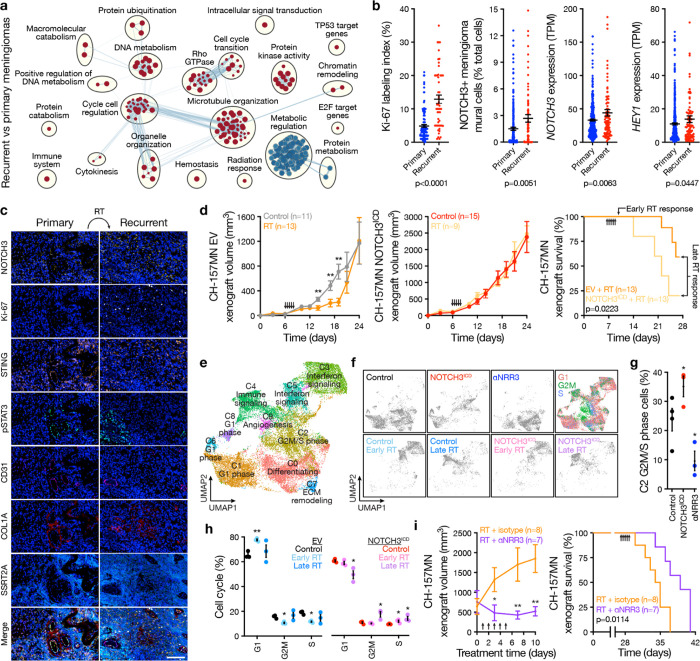

NOTCH3 signaling drives meningioma resistance to radiotherapy

To determine if NOTCH3 underlies meningioma recurrence after standard interventions, differential expression (Supplementary Table 3) and gene ontology analyses (Fig. 4a) were performed on RNA sequencing data from primary (n=403) compared to recurrent human meningiomas after treatment with surgery and radiotherapy (n=99)11,13. Recurrent meningiomas were distinguished by gene expression programs controlling DNA metabolism, radiotherapy response, cell signaling, and cell proliferation (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 3). Immunostaining for the cell proliferation marker Ki-67, deconvolved NOTCH3 meningioma mural cells from RNA sequencing, and expression of NOTCH3 and HEY1 were enriched in recurrent compared to primary meningiomas (Fig. 4b). Multiplexed sequential IF (seqIF) on 4 pairs of patient-matched meningiomas that were treated with radiotherapy between initial and salvage resections showed NOTCH3 and Ki-67 were enriched in recurrent compared to primary tumors (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 4). In preclinical models, radiotherapy attenuated the growth of CH-157MN EV xenografts but did not attenuate the growth of CH-157MN NOTCH3ICD xenografts, which had worse survival than CH-157MN EV xenografts despite treatment of both models with ionizing radiation (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4. NOTCH3 signaling drives meningioma resistance to radiotherapy.

a, Network of gene circuits distinguishing recurrent (n=99) from primary (n=403) human meningiomas using RNA sequencing. Nodes represent pathways and edges represent shared genes between pathways (p≤0.01, FDR≤0.01). Red nodes are enriched and blue nodes are suppressed in recurrent versus primary meningiomas. b, IHC for Ki-67 in recurrent (n=53) versus primary (n=123) meningiomas, or RNA sequencing of recurrent (n=99) versus primary (n=403) meningiomas for deconvolution of NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells from Fig. 1a or quantification of NOTCH3 or HEY1 expression. TPM, transcripts per million. ANOVA. c, Multiplexed seqIF microscopy showing human meningioma recurrence after radiotherapy (RT) is associated with increased NOTCH3 and Ki-67. Many NOTCH3+ cells also express the interferon and innate immune regulators STING and pSTAT3. CD31 marks pericytes, COL1A marks fibroblasts, SSTR2A marks meningioma cells, and DAPI marks DNA. Representative of n=4 pairs of patient-matched primary and recurrent meningiomas. Scale bar, 100μm. d, CH-157MN meningioma xenograft growth (left and middle, student’s t tests) or survival (log-rank test) after expression of empty vector (EV) or NOTCH3ICD ± RT showing NOTCH3 drives resistance to RT. Arrows indicate RT treatments (2Gy × 5 daily fractions). Xenografts from all arms were isolated for single-cell RNA-sequencing 1 day after completing RT (early) or once median survival was reached in the EV + RT arm (late). e, Single-cell RNA sequencing UMAP of 152,464 meningioma xenograft human cell transcriptomes showing tumor cell states ± αNRR3 treatment for 2 weeks as in Fig. 3f or ± NOTCH3ICD ± RT as in d. f, UMAP showing single-cell RNA sequencing of meningioma xenograft human cells shaded by experimental condition or phase of the cell cycle. g, Analysis of C2 G2M/S phase meningioma xenograft human cells in control versus NOTCH3ICD versus αNRR3 conditions showing NOTCH3 drives meningioma cell proliferation. Colors as in f. Student’s t tests. h, Cell cycle analysis across all clusters of meningioma xenograft human cells ± NOTCH3ICD ± RT showing NOTCH3 sustains cell proliferation through G2M and S phase despite RT. Student’s t test. i, Meningioma xenograft growth (left, student’s t tests) or survival (log-rank test) after treatment with RT as in d ± αNRR3 as in Fig. 3f. αNRR3 treatment was initiated on the first day of radiotherapy and continued until death. Lines represent means and error bars represent standard error of means. *p<0.05, **p≤0.01.

Single-cell RNA sequencing was performed on CH-157MN xenografts after αNRR3 compared to isotype control treatment (Fig. 3f), or after radiotherapy compared to control treatment with EV or NOTCH3ICD overexpression (Fig. 4d). Xenografts were isolated for single-cell RNA sequencing the day after completing radiotherapy (i.e. early) or once median survival was reached in the control arm (i.e. late) to interrogate early versus late effects of ionizing radiation on meningioma cell types (Fig. 4d). Single-cell transcriptomes were mapped to the human and mouse genomes, revealing 152,464 human meningioma cells and 35,230 mouse microenvironment cells across 8 conditions and 23 biological replicates (Extended Data Fig. 11a–e). Reduced dimensionality cell clusters were defined using automated cell type classification26, cell signature gene sets27, cell cycle analysis (Extended Data Fig. 11b), and differentially expressed cluster marker genes (Extended Data Fig. 12a–e and Supplementary Table 5, 6). Genetic activation (NOTCH3ICD) or pharmacologic inhibition (αNRR3) of NOTCH3 influenced the neutrophil, fibroblast, Langerhans cell, conventional dendritic cell, NK cell, and mural cell composition of meningioma xenografts (Extended Data Fig. 12c–e), and NOTCH3+ cells in human meningiomas analyzed using multiplexed seqIF expressed regulators of interferon signaling and innate immune responses (STING, pSTAT3) (Fig. 4c). Radiotherapy induced early monocyte infiltration (Extended Data Fig. 12c–e) and increased interferon and innate immune gene expression from meningioma cells that diminished over time but was conserved across NOTCH3ICD and EV conditions (Fig. 4e, f and Extended Data Fig. 12a, b). Cell cycle analysis across single-cell clusters revealed meningioma cell proliferation was increased by NOTCH3ICD and inhibited by αNRR3 (Fig. 4g). Moreover, radiotherapy inhibited meningioma cell cycle progression in EV xenografts, but NOTCH3ICD sustained the cell cycle through G2M and S phase and increased cell cycle progression in meningioma xenograft samples from late timepoints (Fig. 4h). These data suggest NOTCH3 drives meningioma resistance to radiotherapy through cell cycle progression. In support of this hypothesis, radiotherapy in combination with αNRR3 was more effective than radiotherapy alone at blocking the growth and improving survival from CH-157MN xenografts (Fig. 4i).

Discussion

Here we report NOTCH3 drives meningioma tumorigenesis and resistance to radiotherapy in cell types that are conserved across meningiomas from humans, dogs, and mice. Our results reveal a new therapeutic vulnerability to treat meningiomas that are resistant to standard interventions, and more broadly suggest that meningioma mural cells may be an effective target to treat the most common primary intracranial tumor.

Our data suggest meningioma vasculature is comprised of endothelia from the microenvironment and tumor cells that may fulfill mural cell functions (Fig. 1a–c). NOTCH3 signaling between meningioma mural cells and endothelia (Fig. 1d) and NOTCH3 mediated intratumor angiogenesis (Fig. 3o) may contribute to meningioma migration into surrounding tissues. In support of this hypothesis, meningiomas without evidence of direct brain parenchyma invasion can nevertheless migrate into Virchow-Robin perivascular cavities that surround perforating arteries and veins in the brain (Extended Data Fig. 13a–c). This unique pattern of migration suggests microscopic positive margins along brain vasculature may contribute to meningioma recurrence after standard interventions.

NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells demonstrate several hallmarks of cancer stem cells19, such as driving meningeal (Fig. 2g) or meningioma cell proliferation (Fig. 3e, 4g, 4h), clonogenic growth (Fig. 3j) or tumor initiating capacity (Fig. 3c, k), angiogenesis (Fig. 3m–o), and resistance to treatment (Fig. 4d, i). NOTCH3 marks cancer stem cells in lung, colon, and breast cancers32,54–56, and despite broad NOTCH3 expression in meningiomas, only NOTCH3 meningioma mural cells express other cancer stem cell markers, such as THY133,34 (Extended Data Fig. 1h). Our study focuses on meningiomas with loss of NF2, and considering the histological3 and anatomical diversity of meningiomas22–24, it is likely that other stem or progenitor cells contribute to meningioma tumorigenesis, particularly for Merlin-intact meningiomas. PTGDS has been proposed as a marker of meningioma progenitor cells57, and while PTGDS was only expressed in a subset of single-cells from our study (Extended Data Fig. 1h), PTGDS is more broadly expressed throughout Merlin-intact meningioma single-cell clusters58. Fluorescent lineage tracing using a Ptgds-Cre allele57 shows PTGDS cells are not restricted to the perivascular stem cell nice in the meninges of mice (Extended Data Fig. 14). Thus, if meningiomas from different molecular or histological groups or from different anatomic locations can arise from different stem or progenitor cells, it is possible that the vascular phenotypes we report may be unique to NOTCH3 meningioma mural cells.

NOTCH3 and NOTCH3 target genes are enriched in high-grade (Fig. 1i) and recurrent meningiomas (Fig. 4b), and NOTCH3+ meningioma mural cells are enriched in meningiomas from the Immune-enriched meningioma DNA methylation group (Fig. 3a), but we identify NOTCH3 signaling and NOTCH3+ cells across all grades and molecular groups of meningiomas. Meningiomas from the Hypermitotic DNA methylation groups have the worst clinical outcomes, highest rate of recurrence, and are distinguished by convergent genetic and epigenetic mechanisms that misactivate the cell cycle11. RNAScope shows enriched and diffuse NOTCH3 expression in recurrent Hypermitotic meningiomas (Extended Data Fig. 15). Thus, it is possible that meningiomas from multiple WHO grades or DNA methylation groups with poor clinical outcomes may benefit from treatment with αNRR3 depending on clinical presentation and prior therapy.

The safety and efficacy of selective NOTCH3 inhibition has not been defined in humans, but Notch3 knockout mice are viable and fertile59, and we found that diphtheria toxin ablation of NOTCH3+ cells in utero or in adulthood using the Notch3-CreERT2 and ROSAiDTR alleles60 was not associated with neurological symptoms or other phenotypes. In contrast to αNRR3, αNRR1 did not block the growth of meningioma xenografts (Fig. 3f, g) and was associated with skin rash and diarrhea leading to weight loss (Extended Data Fig. 16a). A small molecule inhibitor of the γ-secretase complex blocked meningioma xenograft growth, but also caused skin rash, diarrhea, and weight loss in mice (Extended Data Fig. 16b, c). In sum, these data suggest αNRR3 may be a safe and effective systemic therapy to treat meningiomas that are resistant to standard interventions.

Methods

Inclusion and ethics

This study complied with all relevant ethical regulations and was approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board (13-12587, 17-22324, 17-23196, and 18-24633). As part of routine clinical practice at UCSF, all human patients who were included in this study signed a written waiver of informed consent to contribute deidentified data to research projects. As part of routine clinical practice at the University of California Davis, all owners of dog meningioma patients who were included in this study signed a written waiver of informed consent to contribute deidentified data to research projects. This study was approved by the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (AN191840), and all experiments complied with relevant ethical regulations.

Single-cell RNA sequencing

Single cells were isolated from fresh tumor or tumor-adjacent dura samples from human or dog meningiomas, or from meningioma xenografts, as previously described11. Single-cell suspensions were processed for single-cell RNA sequencing using the Chromium Single Cell 3’ GEM, Library & Gel Bead Kit v3.1 (1000121, 10x Genomics) and a 10x Chromium controller, using the manufacturer recommended default protocol and settings at a target cell recovery of 5,000 cells per sample. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000, targeting >50,000 reads per cell, at the UCSF Center for Advanced Technology. Library demultiplexing, read alignment, identification of empty droplets, and UMI quantification were performed using CellRanger (https://github.com/10xGenomics/cellranger). Cells were filtered based on the number of unique genes and single-cell UMI count data were preprocessed in R with the Seurat61,62 package (v4.3.0) using the sctransform workflow63. Dimensionality reduction was performed using PC analysis. Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) and Louvain clustering were performed on the reduction data, followed by marker identification and differential gene expression.

Clusters were defined using a combination of automated cell type classification26, cell signature gene sets27, cell cycle analysis, and differentially expressed cluster marker genes. The ScType R package was used for automated cell type classification, with default parameters and package-provided marker genes specific to each cell type26. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed on clusters using cell type signature gene sets from MSigDB (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb) with the fgsea R package (Bioconductor v3.16). Cell cycle phases of individual cells were assigned with the ‘CellCycleScoring’ function in Seurat, using single-cell cell cycle marker genes64.

Human meningioma single-cell samples were aligned to the GRCh38 human reference genome; filtered to cells with greater than 250 unique genes, less than 7,500 unique genes, and less than 25% of reads attributed to mitochondrial transcripts; scaled based on regression of UMI count and percentage of reads attributed to mitochondrial genes per cell; and corrected for batch effects using Harmony25. Parameters for downstream analysis were a minimum distance metric of 0.4 for UMAP, resolution of 0.2 for Louvain clustering, and a minimum difference in fraction of detection of 0.4 and a minimum log-fold change of 0.5 for marker identification. All human meningiomas analyzed using single-cell RNA sequencing in this study had DNA methylation profiles classifying as Immune-enriched or Hypermitotic11, or had biallelic inactivation of NF2 including loss of at least 1 copy of chromosome 22q from targeted next-generation DNA sequencing65.

Dog meningioma single-cell samples were aligned to the ROSCfam1.0 canine reference genome; filtered to cells with greater than 1,000 unique genes and less than 6,500 unique genes; scaled based on regression of UMI count; and corrected for batch effects using Harmony25. Parameters for downstream analysis were a minimum distance metric of 0.2 for UMAP, resolution of 0.2 for Louvain clustering, and a minimum difference in fraction of detection of 0.25 and a minimum log-fold change of 0.8 for marker identification.

Meningioma xenograft single-cell samples were aligned to a multi-species reference genome comprised of the GRCh37 human reference genome and the GRCm38 mouse reference genome. Cells were classified as human or mouse cells based on the percentage of UMIs aligning to each genome and the distribution of those percentages. Cells with >97% of UMIs aligning to the human genome were classified as human cells, while cells with >75% of UMIs aligning to the mouse genome were classified as mouse cells. Human and mouse cells were analyzed independently after alignment.

Meningioma xenograft human tumor cells were filtered to cells with greater than 200 unique genes, less than 9,000 unique genes, and less than 20% of reads attributed to mitochondrial transcripts; and scaled based on regression of UMI count and percentage of reads attributed to mitochondrial genes per cell. Parameters for downstream analysis were a minimum distance metric of 0.1 for UMAP, resolution of 0.2 for Louvain clustering, and a minimum difference in fraction of detection of 0.3 and a minimum log-fold change of 0.25 for marker identification.

Meningioma xenograft mouse microenvironment cells were filtered to cells with greater than 250 unique genes, less than 7,500 unique genes, and less than 5% of reads attributed to mitochondrial transcripts; and scaled based on regression of UMI count and percentage of reads attributed to mitochondrial genes per cell. Parameters for downstream analysis were a minimum distance metric of 0.2 for UMAP, resolution of 0.2 for Louvain clustering, and a minimum difference in fraction of detection of 0.5 and a minimum log-fold change of 0.5 for marker identification.

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis

Single human meningioma cells were classified as tumor or non-tumor cells based on copy number loss of chromosome 22q. All human meningiomas analyzed using single-cell RNA sequencing in this study had copy number loss of chromosome 22q from DNA methylation profiling or targeted next-generation DNA sequencing65. The presence or absence of copy number variants in individual cells was assessed using the CONICSmat R package (v1.0)28. Briefly, a two-component Gaussian mixture model was fit to the average expression values of genes on chromosome 22q across all cells assessed. The command ‘plotAll’ from CONICSmat was run with the parameters ‘repetitions=100, postProb=0.8’. Cells with a posterior probability less than 0.2 were identified as tumor, while cells with a posterior probability greater than 0.8 were identified as normal.

The cell-cell communication network for the Notch signaling pathway was inferred and visualized using the CellChat R package (v1.5.0)35. Briefly, differentially expressed signaling genes were identified, noise was mitigated by calculating the ensemble average expression, intercellular communication probability was calculated by modeling ligand-receptor interactions using the law of mass action, and statistically significant communications were identified. The command ‘computeCommunProb’ from CellChat was run with the parameters ‘raw.use=FALSE, nboot=20’. All other commands were run with default parameters.

Human meningioma single-cell cluster identities were projected onto reduced dimensionality clusters of dog meningioma cells using the commands ‘FindTransferAnchors’ and ‘TransferData’ from Seurat. The parameter ‘normalization.method = ”SCT”’ was used for ‘FindTransferAnchors’ and defaults were used for all other parameters for both commands.

Bulk RNA-sequencing analysis

Human meningioma bulk RNA sequencing data were generated and analyzed as previously described11,13. In brief, RNA was extracted from frozen meningiomas, and library preparation was performed using the TruSeq Standard mRNA Kit (20020595, Illumina) 50 bp single-end or 150 bp paired-end reads that were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 to a mean of 20 million reads per sample. Analysis was performed using a pipeline comprised of FastQC for quality control, and Kallisto for reading pseudoalignment and transcript abundance quantification using the default settings (v0.46.2).

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA v4.3.2) was performed to identify differentially expressed pathways distinguishing recurrent from primary meningiomas. Gene rank scores were calculated using the formula sign(log2 fold-change) × −log10(p-value). Pathways were defined using the gene set file Human_GOBP_AllPathways_no_GO_iea_December_01_2022_symbol.gmt, which is maintained by the Bader laboratory. Gene set size was limited to range between 15 and 500, and positive and negative enrichment files were generated using 2000 permutations. The EnrichmentMap App (v3.3.4) in Cytoscape (v3.7.2) was used to visualize the results of pathway analysis. Nodes with p≤0.01 and FDR≤0.01, and nodes sharing gene overlaps with Jaccard + Overlap Combined (JOC) threshold of 0.375 were connected by blue lines (edges) to generate network maps. Clusters of related pathways were identified and annotated using the AutoAnnotate app (v1.3.5) in Cytoscape that uses a Markov Cluster algorithm to connect pathways by shared keywords in the description of each pathway. The resulting groups of pathways were designated as the consensus pathways in each circle.

Histology, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and microscopy

For adult human tissue samples, deparaffinization and rehydration of 5μm formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections and H&E staining were performed using standard procedures. Immunostaining was performed on an automated Ventana Discovery Ultra staining system and detection was performed with Multimer HRP (Ventana Medical Systems) followed by fluorescent detection (DISCOVERY Rhodamine and CY5) or DAB. Immunostaining for NOTCH3 was performed using mouse monoclonal NOTCH3/N3ECD primary antibody (MABC594, Millipore Sigma, 1:25–1:100) with incubation for 32min following CC1 antigen retrieval for 32min. For dual staining, primary antibody incubations were carried out serially with inclusion of positive, negative, and single antibody controls. Following staining for NOTCH3/N3ECD, tissue sections were stained with primary antibodies recognizing CD34 (CBL496, Millipore Sigma, mouse monoclonal, 1:300) for 2h, SMA (ab7817, Abcam, mouse polyclonal, 1:30,000) for 32min, or VWF (A0082, Dako, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000) for 20min. All IF experiments were imaged on a LSM 800 confocal laser scanning microscope with Airyscan (Zeiss) and analyzed using ImageJ.

For meningioma xenograft samples, deparaffinization and rehydration of 5μm FFPE tissue sections and H&E staining were performed using standard procedures. IHC was performed on an automated Ventana Discovery Ultra staining system using primary antibodies recognizing Ki-67 (M7240, DAKO, mouse monoclonal, clone MIB1, 1:50) for 30min, CD34 (NCL-L-END, LEICA, mouse monoclonal, clone QBEnd/10, undiluted) for 15min, or ERG (790-4576, Ventana, rabbit monoclonal, clone EPR3864, undiluted) for 32min. All histological and IHC experiments were imaged on a BX43 light microscope (Olympus) and analyzed using the Olympus cellSens Standard Imaging Software package.

For IF of the developing human brain, de-identified tissue samples were collected with previous patient consent in strict observance of legal and institutional ethical regulations. Autopsy consent and all protocols were approved by the UCSF Human Gamete, Embryo, and Stem Cell Research Committee. All cases were determined by chromosomal analysis, physical examination, and/or pathological analysis to be control tissues, which indicates that they were absent of neurological disease. Brains were cut into ~1.5cm coronal or sagittal blocks, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 days, and then cryoprotected in a 30% sucrose solution. Blocks were cut into 30μm sections on a cryostat, mounted on glass slides for IF, and stored at −80°C. Frozen slides were moved from −80°C to 4°C the night prior to staining and then to the lab bench for 2h before beginning the immunostaining protocol. Slides were washed once with 1X PBS for 5 minutes, then once with 1X TBS for 5min before blocking with TBS++++ (goat serum, BSA, albumin, glycine, and triton X in TBS) for 1h. Primary antibodies recognizing PDGFRB (AF385, R&D Systems, 1:200), CD34 (AF7227, R&D Systems, 1:200), or NOTCH3/N3ECD as described above were used with overnight incubation at room temperature at 1:200 dilutions in TBS++++. The following day, three 1x TBS washes were performed before incubating with secondary antibodies in TBS++++ for 2h. After three additional TBS washes, DAPI (62248, ThermoFisher Scientific) was added, and the slides were mounted.

Immunofluorescence of meningioma cell lines were performed on cover glass slips in culture. Cells were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 8min, washed in PBS, blocked for 30min in 5% donkey serum and 0.1% TritonX100 in PBS. Cells were staining with PTPRZ1 (sc-33664, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000) overnight at 4°C and subsequently labeled with rabbit Alexa Fluor secondary antibody (A21206, ThermoFischer Scientific, 1:1000) and Hoechst 33342 to mark DNA for 1h at room temperature prior to mounting and imaging. Meningioma cells were imaged on a LSM 800 confocal laser scanning microscope with Airyscan (Zeiss) and analyzed using ImageJ.

RNAScope and microscopy

The RNAScope Multiplex Fluorescent V2 assay (32310, ACDBio) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 5μm FFPE meningioma sections were incubated with hydrogen peroxide to inhibit endogenous peroxidase, followed by processing for target retrieval and treatment with ProteasePlus. Meningioma sections were subsequently incubated with RNA probes for NOTCH3 (558991-C2, Hs-NOTCH3-C2) and NF2 (1037481-C, Hs-NF2-C1), followed by revelation and amplification steps. Meningioma sections were blocked (5% normal donkey serum, 1X Animal Free blocking, 0.3% Triton X-100) for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with primary antibody against VE-cadherin (AF938, R&D Systems, 1:100) overnight at 4°C. The next day, meningioma sections were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature and counterstained with DAPI (62248, ThermoFisher Scientific). Meningioma sections were imaged on a LSM 800 confocal laser scanning microscope with Airyscan (Zeiss) and analyzed using ImageJ.

Multiplexed sequential immunofluorescence (seqIF) and microscopy

Automated multiplexed seqIF staining and imaging was performed on FFPE sections at Northwestern University using the COMET platform (Lunaphore Technologies). The multiplexed panel was comprised of 29 antibodies (Supplementary Table 4). The 29-plex protocol was generated using the COMET Control Software, and reagents were loaded onto the COMET device to perform seqIF. All antibodies were validated using conventional IHC and/or IF staining in conjunction with corresponding fluorophores and DAPI (62248, ThermoFisher Scientific). For optimal concentration and best signal-to-noise ratio, all antibodies were tested at 3 different dilutions: starting with the manufacturer-recommended dilution (MRD), MRD/2, and MRD/4. Secondary Alexa fluorophore 555 (A32727, ThermoFisher Scientific) and Alexa fluorophore 647 (A32733, ThermoFisher Scientific) were used at 1:200 or 1:400 dilutions, respectively. The optimizations and full runs of the multiplexed panel were executed using the seqIF technology integrated in the Lunaphore COMET platform (characterization 2 and 3 protocols, and seqIF protocols, respectively). The seqIF workflow was parallelized on a maximum of 4 slides, with automated cycles of iterative staining of 2 antibodies at a time, followed by imaging, and elution of the primary and secondary antibodies, with no sample manipulation during the entire workflow. All reagents were diluted in Multistaining Buffer (BU06, Lunaphore Technologies). The elution step lasted 2min for each cycle and was performed with Elution Buffer (BU07-L, Lunaphore Technologies) at 37°C. Quenching lasted for 30sec and was performed with Quenching Buffer (BU08-L, Lunaphore Technologies). Incubation time was set at 4min for all primary antibodies, except for the p16 antibody at 8min, and secondary antibodies at 2min. Imaging was performed with Imaging Buffer (BU09, Lunaphore Technologies) with exposure times set for 400 ms for the TRITC channel, 200ms for the Cy5 channel, and 80ms for the DAPI channel. Imaging was performed with Imaging Buffer (BU09, Lunaphore Technologies) with exposure times set at 4min for all primary antibodies, except P16 antibody at 8min, and secondary antibodies at 2min. Imaging was performed with an integrated epifluorescent microscope at 20x magnification. Image registration was performed immediately after concluding the staining and imaging procedures by COMET Control Software. Each seqIF protocol resulted in a multi-stack OME-TIFF file where the imaging outputs from each cycle were stitched and aligned. COMET OME-TIFF files contain a DAPI image, intrinsic tissue autofluorescence in TRITC and Cy5 channels, and a single fluorescent layer per marker. Markers were subsequently pseudocolored for visualization of multiplexed antibodies.

Mouse genetic models

Notch3tm1.1(cre/ERT2)Sat (Notch3-CreERT2) mice were obtained from the Sweet-Cordero Lab at UCSF. Ptgdstm1.1(cre)Gvn (Ptgds-Cre) mice were obtained from Riken. Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo (ROSAmT/mG) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(HBEGF)Awai/J (ROSAiDTR) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. FVB.129P2-Nf2tm2Gth (Nf2fl/fl) mice were obtained from Riken. All mouse genetic experiments were performed on the C57BL/6J background. Mice were intercrossed to generate Notch3-CreERT2(+/WT) ROSAmT/mG mice, Ptgds-Cre+/WT ROSAmT/mG mice, Notch3-CreERT2(+/WT) Nf2fl/fl mice, and Notch3-CreERT2(+/WT) ROSAiDTR mice. Recombination of either the Nf2 or ROSA locus was induced using intraperitoneal injection of 75mg/kg of tamoxifen (T5648, Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in corn oil. For in utero recombination, pregnant dams were injected with tamoxifen once at E16.5 and their subsequent litters were genotyped and euthanized at the indicated timepoints. For postnatal recombination, mice were injected daily 5 times with tamoxifen and euthanized at the indicated timepoints.

Mouse skullcaps for meningeal lineage tracing experiments and intact skulls for tumorigenesis experiments were processed as previously described66. In brief, mice were perfused with 4°C 4% paraformaldehyde in 80nM Pipes, pH 6.8, 5mM EGTA, and 2mM MgCl2. Muscle was dissected and removed, and samples were rotated overnight at 4°C in perfusion solution. Samples were washed three times for 5min in PBS and decalcified for 3 days rotating at 4°C in 20% EDTA, pH 7.4, in PBS. For meningioma tumorigenesis experiments, whole skulls were subsequently embedded in 5% low-melt agarose (Precisionary) and cut into 300μm sections on a Vibratome (VT1000S, Leica). Sections were stained for 15s in Mayer’s Hematoxylin solution (MHS16, Sigma-Aldrich), washed three times for 5min in distilled water, incubated for 1min in PBS to blue nuclei, washed for 5min in distilled water, stained for 30s in 0.5% Eosin Y (1099884, Sigma-Aldrich), washed two times for 5min in 70% ethanol, and mounted on slides using Vectashield Antifade Mounting Media (H-1000-10, Vector Laboratories).

Mouse xenograft models and treatments

Xenograft experiments were performed by implanting CH-157MN or IOMM-Lee cells into the flank of 5- to 6-week-old female NU/NU mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley) as previously described11. Tumor initiating capacity was defined by the development of sustained, iteratively increasing subcutaneous growth at injection sites. Radiotherapy treatments were performed using a Precision X-RAD 320 Cabinet Irradiator with normal operating settings to deliver 2Gy of ionizing radiation on each of 5 consecutive days. NOTCH3 negative regulatory region neutralizing antibody treatments (αNRR3) and NOTCH1 negative regulatory region neutralizing antibody (αNRR1) treatments using murine antibodies from Genentech were performed as previously described7,8, with bi-weekly IP injection of 20mg/kg αNRR3, 10mg/kg αNRR1 (dose-reduced due to gastrointestinal and cutaneous toxicity leading to weight loss), or 20mg/kg IgG2a isotype control (BE0085, Bio X-cell). γ-secretase inhibitor treatments were performed using LY-411575 (SML0649, Millipore Sigma) as previously described47, with daily 20μM/kg IP injections in 0.5% methylcellulose and 0.1% Tween 80 in 1xPBS. For Kaplan-Meier survival analyses, events were recorded when tumors reached the protocol-defined size of 2000 mm3, mice developed mobility or physiological impairment from tumor burden, or mice lost >15% of body weight due to treatment-associated toxicity.

Cell culture

HEK293T (CRL-3216, ATCC), IOMM-Lee51, or CH157-MN50 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (11960069, Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1x GlutaMAX (35050-061, ThermoFischer Scientific) and 1x Penicillin/Streptomycin (15140122, Life Technologies).

To generate cell lines overexpressing NOTCH3 ICD, pLVX-Puro plasmid containing pCMV6-NOTCH3ICD was generated. Lentiviral particles were produced by transfecting HEK293T cells with standard packaging vectors using the TransIT-Lenti Trasfection Reagent (6605, Mirus). CH157-MN cells were stably transduced with lentiviral particles to generate CH-157MN NOTCH3ICD or empty pLVX vector (EV) cells. Successfully transduced cells were isolated using Puromycin selection, and NOTCH3 overexpression was confirmed using QPCR.

For clonogenic assays, 250 cells were seeded in triplicate for each condition in a 6-well plate and grown for 10 days in standard culture media. Cells were fixed in methanol for 30min, washed and stained in 0.01% crystal violet (C6158, Sigma-Aldrich) for 3hours, washed 3 times in distilled water, and dried overnight. Cells were imaged on a Stemi 508 stereo microscope (Zeiss) and clonogenic area was quantified in ImageJ.

Immunoblotting

Meningioma cells for immunoblotting were lysed in 1% SDS in 100mM pH 6.8 Tris-HCL containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor (A32961, Thermo Scientific), vortexed at maximum speed for 1min, rocked at 4°C for 5min, and centrifuged at 4°C for 15min at 15000×g. Supernatant protein quantification was performed using BCA assays (23225, Pierce). 20μg of lysate from each cell line was boiled for 15 min in Laemmli reducing buffer. Proteins were separated on 4–15% TGX precast gels (5671084, Bio-Rad), and transferred onto ImmunBlot PVDF membrane (1620177, Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked in 5% TBST-milk, incubated in primary antibodies, washed, and incubated in secondary antibodies. Membranes were subjected to immunoblot analysis using Pierce ECL substrate (32209, Thermo Fischer Scientific). Primary antibodies recognizing NOTCH3 (5276, Cell Signaling, 1:1000) or GAPDH (8245, Abcam, 1:5000) and secondary antibodies recognizing mouse (7076, Cell Signaling, 1:2000) or rabbit (7074, Cell Signaling, 1:2000) epitope were used.

Quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

RNA was extracted from cultured meningioma cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (74106, QIAGEN) according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from extracted RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (1708891, Bio-Rad). Real-time QPCR was performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (A25918, Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a QuantStudio 6 Flex Real Time PCR system (Life Technologies) using forward and reverse primers (NOTCH3-F CGTGGCTTCTTTCTACTGTGC, NOTCH3-R CGTTCACCGGATTTGTGTCAC, HEY1-F GTTCGGCTCTAGGTTCCATGT, HEY1-R CGTCGGCGCTTCTCAATTATT, GAPDH-F GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG, GAPDH-R ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA). QPCR data were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method relative to GAPDH expression.

Statistics

All experiments were performed with independent biological replicates and repeated, and statistics were derived from biological replicates. Biological replicates are indicated in each figure panel or figure legend. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but sample sizes in this study are similar or larger to those reported in previous publications. Data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. Investigators were blinded to conditions during clinical data collection and analysis of mechanistic or functional studies. Bioinformatic analyses were performed blind to clinical features, outcomes, or molecular characteristics. The clinical samples used in this study were retrospective and nonrandomized with no intervention, and all samples were interrogated equally. Thus, controlling for covariates among clinical samples was not relevant. Cells and animals were randomized to experimental conditions. No clinical, molecular, or cellular data points were excluded from the analyses. Lines represent means, and error bars represent standard error of the means. Results were compared using Student’s t-tests and ANOVA, which are indicated in figure panels or figure legends alongside approaches used to adjust for multiple comparisons. In general, statistical significance is shown using asterisks (*p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.0001), but exact p-values are provided in figure panels or figure legends when possible.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mark Youngblood, Julie Siegenthaler, Sten Linnarsson, Elin Vinsland, Chris Siebel, Fred De Sauvage, Alejandro Sweet-Cordero, Kieren Marini, Kyla Foster, and members of the Raleigh lab for reagents, guidance, and edits, Beverly Sturges and Chai Fei Li for providing dog meningioma samples, Shai and the staff of the UCSF Brain Tumor Center Biorepository and Pathology Core, Eric Chow and the staff of the UCSF Center for Advanced Technology, and Ken Probst and Noel Sirivansanti for Illustrations. Lunaphore COMET multiplexed seqIF was enabled by a gift from the Stephen M. Coffman trust to the Northwestern University Malnati Brain Tumor Institute of the Lurie Cancer Center. This study was supported by the UCSF Wolfe Meningioma Program Project and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants F30 CA246808 and T32 GM007618 to AC; NIH grants T32 CA15102 and P50 CA097257 to C-HGL; NIH grant P50 CA097257 to JJP; NIH grant P50 CA097257 to WCC; the UCSF Wolfe Meningioma Program Project and P50 CA097257 to NAOB; NIH grants R01 NS117104, R01 NS118039, and P50 CA221747 to CMH; the UCSF Wolfe Meningioma Program Project, NIH grant F32 CA213944, and the Northwestern Medicine Malnati Brain Institute of the Lurie Cancer Center to STM; NIH grants R01 CA120813, R01 NS120547, and P50 CA221747 to ABH; and NIH grants R01 CA262311 and P50 CA097257, and the UCSF Wolfe Meningioma Program Project to DRR.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

AA is a co-founder of Tango Therapeutics, Azkarra Therapeutics, Ovibio Corporation, and Kytarro; a member of the board of Cytomx and Cambridge Science Corporation; a member of the scientific advisory board of Genentech, GLAdiator, Circle, Bluestar, Earli, Ambagon, Phoenix Molecular Designs, Yingli, ProRavel, Oric, Hap10, and Trial Library; a consultant for SPARC, ProLynx, Novartis, and GSK; receives research support from SPARC; and holds patents on the use of PARP inhibitors held jointly with AstraZeneca.

Code availability

The open-source software, tools, and packages used for data analysis in this study, as well as the version of each program, were ImageJ (v2.1.0), CellRanger (v6.1.2 and v7.1.0), kallisto (v0.46.2), GSEA (v4.3.2), EnrichmentMap (v3.3.4), Cytoscape (v3.7.2), AutoAnnotate (v1.3.5), R (v4.2.3), Seurat R package (v4.3.0), Harmony R package (v0.1.1), ScType R package (v1), CONICSmat R package (v1.0), CellChat R package (v1.5.0), fgsea (Bioconductor v3.16), and DESeq2 (Bioconductor v3.16). No software was used for data collection. No custom algorithms or code were used.

Data availability

Single-cell RNA sequencing data of new samples (n=1 human meningioma sample, n=3 canine meningioma samples, n=2 canine dura samples, n=23 meningioma xenograft samples) that are reported in this manuscript will be deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus upon provisional acceptance and are available during the review process upon request. Additional single-cell RNA sequencing data from previously reported human meningiomas (n=4 meningioma samples, n=1 dura sample) are available under the accession GSE183655 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE183655). RNA sequencing and DNA methylation profiling data of human meningioma samples (n=502) are available under the accessions GSE183656 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE183656), GSE212666 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE212666), GSE183653 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE183653), and GSE101638 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi). The publicly available GRCh38 (hg38, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000001405.39/), GRCh37 (hg19, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000001405.25/), GRCm38 (mm10, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000001635.20/), and ROS_Cfam_1.0 datasets (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_014441545.1/) were used in this study. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

- 1.Goldbrunner R. et al. EANO guideline on the diagnosis and management of meningiomas. Neuro-oncology 23, 1821–1834 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrom Q. T. et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2015–2019. Neuro-oncology 24, v1–v95 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis D. N. et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol 23, 1231–1251 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brastianos P. K. et al. Advances in multidisciplinary therapy for meningiomas. Neuro-oncology 21, i18–i31 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen P. Y., Quant E., Drappatz J., Beroukhim R. & Norden A. D. Medical therapies for meningiomas. J. Neurooncol. 99, 365–378 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W. C. et al. Radiotherapy for meningiomas. J Neuro-oncol 160, 505–515 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Y. et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting of individual Notch receptors. Nature 464, 1052–1057 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei K. et al. Notch signalling drives synovial fibroblast identity and arthritis pathology. Nature 582, 259–264 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin D. et al. Trends in intracranial meningioma incidence in the United States, 2004–2015. Cancer Med-us 8, 6458–6467 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson D. The Recurrence of Intracranial Meningiomas After Surgical Treatment. (1957). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Choudhury A. et al. Meningioma DNA methylation groups identify biological drivers and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Nat. Genet. 54, 649–659 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driver J. et al. A Molecularly Integrated Grade for Meningioma. Neuro Oncol (2021) doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choudhury A. et al. Hypermitotic meningiomas harbor DNA methylation subgroups with distinct biological and clinical features. Neuro-oncology (2022) doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maas S. L. N. et al. Integrated Molecular-Morphologic Meningioma Classification: A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis, Retrospectively and Prospectively Validated. J. Clin. Oncol. JCO2100784 (2021) doi: 10.1200/jco.21.00784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahm F. et al. DNA methylation-based classification and grading system for meningioma: a multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. (2017) doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel A. J. et al. Molecular profiling predicts meningioma recurrence and reveals loss of DREAM complex repression in aggressive tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 21715–21726 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nassiri F. et al. A clinically applicable integrative molecular classification of meningiomas. Nature 597, 119–125 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Youngblood M. W. et al. Correlations between genomic subgroup and clinical features in a cohort of more than 3000 meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. 1, 1–10 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanahan D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 12, 31–46 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tohma Y., Yamashima T. & Yamashita J. Immunohistochemical localization of cell adhesion molecule epithelial cadherin in human arachnoid villi and meningiomas. Cancer Research 52, 1981–1987 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashima T., Kida S. & Yamamoto S. Ultrastructural comparison of arachnoid villi and meningiomas in man. Mod Pathology Official J United States Can Acad Pathology Inc 1, 224–34 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Incarbone M. et al. Primary pulmonary meningioma Report of a case and review of the literature. Lung Cancer 62, 401–407 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jadik S., Stan A. C., Dietrich U., Pietilä T. A. & Elsharkawy A. E. Intraparenchymal meningioma mimicking cavernous malformation: a case report and review of the literature. J Medical Case Reports 8, 467 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura M., Roser F., Bundschuh O., Vorkapic P. & Samii M. Intraventricular meningiomas: a review of 16 cases with reference to the literature. Surg Neurol 59, 490–503 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korsunsky I. et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat Methods 16, 1289–1296 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ianevski A., Giri A. K. & Aittokallio T. Fully-automated and ultra-fast cell-type identification using specific marker combinations from single-cell transcriptomic data. Nat Commun 13, 1246 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc National Acad Sci 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller S., Cho A., Liu S. J., Lim D. A. & Diaz A. CONICS integrates scRNA-seq with DNA sequencing to map gene expression to tumor sub-clones. Bioinformatics 34, 3217–3219 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crouch E. E. et al. Ensembles of endothelial and mural cells promote angiogenesis in prenatal human brain. Cell 185, 3753–3769.e18 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winkler E. A. et al. A single-cell atlas of the normal and malformed human brain vasculature. Science 375, eabi7377 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang A. C. et al. A human brain vascular atlas reveals diverse mediators of Alzheimer’s risk. Nature 603, 885–892 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng Y. et al. A rare population of CD24(+)ITGB4(+)Notch(hi) cells drives tumor propagation in NSCLC and requires Notch3 for self-renewal. Cancer Cell 24, 59–74 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Z. F. et al. Significance of CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell 13, 153–166 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang K. H. et al. A CD90+ Tumor-Initiating Cell Population with an Aggressive Signature and Metastatic Capacity in Esophageal Cancer. Cancer Res 73, 2322–2332 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun 12, 1088 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menke J. R. et al. Somatostatin receptor 2a is a more sensitive diagnostic marker of meningioma than epithelial membrane antigen. Acta Neuropathol 130, 441–443 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kopan R. & Ilagan, Ma X. G. The Canonical Notch Signaling Pathway: Unfolding the Activation Mechanism. Cell 137, 216–233 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bray S. J. Notch signalling in context. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 17, 722–735 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bray S. J. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 678–689 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snyder J. M., Shofer F. S., Winkle T. J. & Massicotte C. Canine Intracranial Primary Neoplasia: 173 Cases (1986–2003). J Vet Intern Med 20, 669–675 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joutel A. et al. Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature 383, 707–710 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tournier-Lasserve E. et al. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy maps to chromosome 19q12. Nat Genet 3, 256–259 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegenthaler J. A. et al. Retinoic acid from the meninges regulates cortical neuron generation. Cell 139, 597–609 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siegenthaler J. A. et al. Foxc1 is required by pericytes during fetal brain angiogenesis. Biology Open 2, BIO20135009–659 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zarbalis K. et al. Cortical dysplasia and skull defects in mice with a Foxc1 allele reveal the role of meningeal differentiation in regulating cortical development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14002–14007 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choe Y., Siegenthaler J. A. & Pleasure S. J. A cascade of morphogenic signaling initiated by the meninges controls corpus callosum formation. Neuron 73, 698–712 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fre S. et al. Notch Lineages and Activity in Intestinal Stem Cells Determined by a New Set of Knock-In Mice. PLoS ONE 6, e25785 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muzumdar M. D., Tasic B., Miyamichi K., Li L. & Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45, 593–605 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giovannini M. et al. Conditional biallelic Nf2 mutation in the mouse promotes manifestations of human neurofibromatosis type 2. Genes Dev. 14, 1617–1630 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsai J. C., Goldman C. K. & Gillespie G. Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor in human glioma cell lines: induced secretion by EGF, PDGF-BB, and bFGF. J. Neurosurg. 82, 864–873 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee W. H. Characterization of a newly established malignant meningioma cell line of the human brain: IOMM-Lee. Neurosurgery 27, 389-95-discussion 396 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magill S. T. et al. Multiplatform genomic profiling and magnetic resonance imaging identify mechanisms underlying intratumor heterogeneity in meningioma. Nat Comms 11, 1–15 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Long D. M. Vascular ultrastructure in human meningiomas and schwannomas. J Neurosurg 38, 409–419 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mur E. B. et al. Notch inhibition overcomes resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR-driven lung adenocarcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 130, 612–624 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varga J. et al. AKT-dependent NOTCH3 activation drives tumor progression in a model of mesenchymal colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Med. 217, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Choy L. et al. Constitutive NOTCH3 Signaling Promotes the Growth of Basal Breast Cancers. Cancer Research 77, 1439–1452 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalamarides M. et al. Identification of a progenitor cell of origin capable of generating diverse meningioma histological subtypes. Oncogene 30, 2333–2344 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen M. P. et al. A case (report) for mechanistic validation of meningioma molecular therapies. Neuro-oncology Adv 4, vdac162 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krebs L. T. et al. Characterization of Notch3-deficient mice: Normal embryonic development and absence of genetic interactions with a Notch1 mutation. Genesis 37, 139–143 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buch T. et al. A Cre-inducible diphtheria toxin receptor mediates cell lineage ablation after toxin administration. Nat Methods 2, 419–426 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Butler A., Hoffman P., Smibert P., Papalexi E. & Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 411–420 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stuart T. et al. Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e21 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hafemeister C. & Satija R. Normalization and variance stabilization of single-cell RNA-seq data using regularized negative binomial regression. Genome Biol 20, 296 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tirosh I. et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 352, 189–196 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kline C. N. et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of pediatric neuro-oncology patients improves diagnosis, identifies pathogenic germline mutations, and directs targeted therapy. Neuro-oncology now254 (2016) doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Louveau A., Filiano A. J. & Kipnis J. Meningeal Whole Mount Preparation and Characterization of Neural Cells by Flow Cytometry. Curr Protoc Immunol 121, e50 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Single-cell RNA sequencing data of new samples (n=1 human meningioma sample, n=3 canine meningioma samples, n=2 canine dura samples, n=23 meningioma xenograft samples) that are reported in this manuscript will be deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus upon provisional acceptance and are available during the review process upon request. Additional single-cell RNA sequencing data from previously reported human meningiomas (n=4 meningioma samples, n=1 dura sample) are available under the accession GSE183655 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE183655). RNA sequencing and DNA methylation profiling data of human meningioma samples (n=502) are available under the accessions GSE183656 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE183656), GSE212666 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE212666), GSE183653 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE183653), and GSE101638 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi). The publicly available GRCh38 (hg38, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000001405.39/), GRCh37 (hg19, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000001405.25/), GRCm38 (mm10, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000001635.20/), and ROS_Cfam_1.0 datasets (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_014441545.1/) were used in this study. Source data are provided with this paper.