Abstract

Consciousness is comprised of arousal (i.e., wakefulness) and awareness. Substantial progress has been made in mapping the cortical networks that modulate awareness in the human brain, but knowledge about the subcortical networks that sustain arousal is lacking. We integrated data from ex vivo diffusion MRI, immunohistochemistry, and in vivo 7 Tesla functional MRI to map the connectivity of a subcortical arousal network that we postulate sustains wakefulness in the resting, conscious human brain, analogous to the cortical default mode network (DMN) that is believed to sustain self-awareness. We identified nodes of the proposed default ascending arousal network (dAAN) in the brainstem, hypothalamus, thalamus, and basal forebrain by correlating ex vivo diffusion MRI with immunohistochemistry in three human brain specimens from neurologically normal individuals scanned at 600–750 μm resolution. We performed deterministic and probabilistic tractography analyses of the diffusion MRI data to map dAAN intra-network connections and dAAN-DMN internetwork connections. Using a newly developed network-based autopsy of the human brain that integrates ex vivo MRI and histopathology, we identified projection, association, and commissural pathways linking dAAN nodes with one another and with cortical DMN nodes, providing a structural architecture for the integration of arousal and awareness in human consciousness. We release the ex vivo diffusion MRI data, corresponding immunohistochemistry data, network-based autopsy methods, and a new brainstem dAAN atlas to support efforts to map the connectivity of human consciousness.

One sentence summary:

We performed ex vivo diffusion MRI, immunohistochemistry, and in vivo 7 Tesla functional MRI to map brainstem connections that sustain wakefulness in human consciousness.

INTRODUCTION

To treat disorders of human consciousness, such as coma, vegetative state, and minimally conscious state, it is essential to understand the neuroanatomic determinants and interconnectivity of arousal and awareness, two foundational components of consciousness (1). The goal of this multimodal brain mapping study is to advance knowledge of the connectivity of human consciousness by crystalizing the concept of a subcortical default arousal network that sustains wakefulness in the resting, conscious human brain, analogous to the cortical default mode network (DMN) that is believed to sustain self-awareness (2). We additionally provide a conceptual framework, imaging methods, and atlas-based reference tools that can be used to elucidate subcortical contributions to human consciousness.

Arousal refers to physiologic activation of the brain to a state of wakefulness (3), whereas awareness refers to the content of consciousness (4). These two components of consciousness – arousal and awareness – can be dissociated, as observed in patients in the vegetative state (5), who demonstrate alternating cycles of wakefulness but absent awareness (5). Such clinical observations, bolstered by experimental data in animals (6–8), support the concept that the anatomic pathways of awareness and arousal are anatomically dissociated from one another in the brain.

Current concepts of consciousness propose that the cerebral cortex is the primary anatomic site of the neural correlates of awareness (4), whereas ascending subcortical pathways from the brainstem, hypothalamus, thalamus, and basal forebrain are the neural correlates of arousal (9, 10). Over the past two decades, there has been substantial progress in mapping the cortical brain networks that mediate human awareness (4, 11, 12). In contrast, connectivity maps of subcortical networks that mediate human arousal are far less complete. This gap in knowledge is partly attributable to inadequate spatial resolution of standard neuroimaging techniques, which cannot discriminate individual arousal nuclei within the brainstem or delineate complex trajectories of axonal connections that link the brainstem to the diencephalon, basal forebrain, and cerebral cortex. In the absence of adequate imaging techniques for detecting brainstem arousal nuclei and their axonal connections, subcortical arousal network mapping has stalled while cortical awareness network mapping has accelerated.

The few human studies of brainstem arousal nuclei generally support Moruzzi and Magoun’s seminal observations in cats regarding the key role of the brainstem reticular formation in activating the cerebral cortex (13). Positron emission tomography (PET) studies have identified an increase in metabolic activity within the brainstem reticular formation when humans wake from sleep (14). Similarly, PET studies have revealed altered metabolism within the reticular formation in patients with disorders of consciousness caused by severe brain injuries (15).

Beyond the reticular formation, animal and human studies have revealed that extrareticular nuclei in the brainstem (6, 16–19), as well as nuclei in the hypothalamus (7, 20, 21), thalamus (22, 23), and basal forebrain (6, 24, 25), also contribute to arousal (6, 26, 27). Collectively, these observations suggest that the human ascending arousal network (AAN) is a synchronized, multi-transmitter brain network comprised of reticular and extrareticular nuclei that generate activated states of alertness in response to multiple external stimuli, including noxious, tactile, vestibular, olfactory, auditory, thermal, and homeostatic stimuli (e.g., hypoxia and hypercarbia). Our goal here is to identify the anatomic substrate of the AAN that modulates the default state of resting wakefulness, which we refer to as the default ascending arousal network (dAAN).

Default modes of brain activity involve neuronal ensembles that create distinct oscillatory modes of firing patterns during different brain states (28). In the awake state, the brain toggles between a default mode of wakefulness (i.e., resting wakefulness) and a non-default mode of wakefulness (i.e., active attention or task performance) (2, 29). In this conceptual framework, a default network is one whose nodes demonstrate temporally correlated activity during a default mode of brain activity (30). Maintenance of the resting wakeful state requires input from the dAAN. This view of a default state of arousal is consistent with that expressed by Steriade and Buzsaki, who wrote that “operationally, arousal may be defined as a stand-by mode of the neurons for efficient processing and transformation of afferent information” (31). In the “stand-by mode” of resting wakefulness, the human brain is not performing an externally or internally directed (i.e., introspective) task. Instead, the mind wanders and stimulus-independent thoughts may emerge (32). Behaviorally, the eyes may be open or closed. Electrophysiologically, subcortical arousal neurons fire tonically (33) and the cerebral cortex generates desynchronized, high frequency, low voltage waves on EEG (3). The dAAN thus sustains cortical activation to enable awareness, without requiring sensory input or externally directed cognition.

To advance knowledge about the connectivity of this subcortical default brain network critical to human consciousness, we performed a multimodal brain imaging study, integrating data from ex vivo diffusion MRI tractography and in vivo 7 Tesla functional MRI. We used histology and immunohistochemistry guidance to identify the anatomic location of dAAN nodes on ex vivo MRI scans of three human brain specimens, then mapped the structural connections of the dAAN using diffusion MRI tractography at submillimeter spatial resolution. We then performed resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) analyses of 7 Tesla imaging data from the Human Connectome Project (34) to investigate the functional correlates of these structural connections. The complementary structural-functional connectivity analyses aimed to identify the neuroanatomic basis for the integration of arousal and awareness in the resting, conscious human brain. We release all network-based autopsy methods and data, and we propose a neuroanatomic taxonomy for projection, association, and commissural pathways of the human dAAN to guide future investigations into the connectivity of human consciousness and its disorders.

RESULTS

Candidate dAAN nodes

Based on evidence from previously published electrophysiological, gene expression, lesion, and stimulation studies, we identified 18 candidate dAAN nodes: 10 brainstem, 3 thalamus, 3 hypothalamus, and 2 basal forebrain (Table 1). All 18 candidate nodes were located at the level of, or rostral to, the mid-pons. For the 13 nodes with available electrophysiological data (all except periaqueductal grey [PAG], pontis oralis [PnO], parabrachial complex [PBC], paraventricular nucleus [PaV], and supramammillary nucleus [SuM]), the electrophysiological evidence indicated active tonic firing of neurons during wakefulness and state-dependent changes in neuronal firing during wakefulness as compared to slow-wave sleep (Table 1).

Table 1.

Candidate default ascending arousal network (dAAN) nodes.

| Candidate dAAN node | Supporting Literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study author, year | Animal model | Type of Evidence | |

| Brainstem | |||

| Midbrain reticular formation (mRt) | Steriade, 1982 (35) | cat | electrophysiology |

| Ventral tegmental area (VTA) | Eban-Rothschild, 2016 (19) | mouse | electrophysiology |

| Periacqueductal grey (PAG) | Lu, 2006 (36) | rat | gene expression |

| Pedunculotegmental nucleus (PTg) | Steriade, 1990 (33) | cat | electrophysiology |

| Dorsal raphe (DR) | McGinty, 1976 (37) Trulson, 1979 (27) | cat | electrophysiology |

| Pontis oralis (PnO) | Xi, 2004 (38) | cat | Agonist/antagonist injection |

| Parabrachial complex (PBC) | Fuller, 2011 (6) Qiu 2016 (39) | rat | Lesion (Fuller) Stimulation (Qiu) |

| Median raphe (MnR) | Trulson, 1984 (40) | cat | electrophysiology |

| Locus coeruleus (LC) | Hobson, 1975 (26) Aston-Jones, 1981 (41) | rat (Aston-Jones), cat (Hobson) | electrophysiology |

| Laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDTg) | Steriade, 1990 (33) | cat | electrophysiology |

| Hypothalamus | |||

| Tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) | Takahashi, 2006 (42) | mouse | electrophysiology |

| Lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) | Alam, 2002 (43) | rat | electrophysiology |

| Supramammillary nucleus (SUM) | Pedersen, 2017 (7) | mouse | chemogenetics |

| Thalamus | |||

| Intralaminar nuclei (IL) | Glenn, 1982 (22) | cat | electrophysiology |

| Reticular nucleus (Ret) | Steriade, 1986 (44) | cat | electrophysiology |

| Paraventricular nucleus (PaV) | Novak, 1998 (45) | rat | gene expression |

| Basal Forebrain | |||

| Nucleus basalis of Meynert/substantia innominata (BNM/SI) | Szymusiak, 1986 (46) | cat | electrophysiology |

| Diagonal band of Broca (DBB) | Szymusiak, 1986 (46) | cat | electrophysiology |

We identified 18 nodes that met the a priori criteria for inclusion in the human dAAN. The criteria were based on previous animal studies demonstrating nodal involvement in arousal from electrophysiological recording, Fos expression, lesioning, or stimulation. Given that decades of experiments in multiple animal species have tested the functional properties of subcortical arousal nuclei, we do not intend for the references in this table to be exhaustive. Rather, we list studies that are representative of the body of literature pertaining to each subcortical arousal nucleus.

We identified 18 nodes that met the a priori criteria for inclusion in the human dAAN. The criteria were based on previous animal studies demonstrating nodal involvement in arousal from electrophysiological recording, Fos expression, lesioning, or stimulation. Given that decades of experiments in multiple animal species have tested the functional properties of subcortical arousal nuclei, we do not intend for the references in this table to be exhaustive. Rather, we list studies that are representative of the body of literature pertaining to each subcortical arousal nucleus.

dAAN structural connectivity

Human brain specimens

Once the 18 candidate dAAN nodes were identified, we investigated their structural connectivity using ex vivo diffusion MRI tractography in three human brain specimens from neurologically normal individuals. The three brain specimens were from women who died at ages 53, 60, and 61 years (Fig. S1–S3). Demographic and clinical data, including cause of death, are provided in Table S1. At autopsy, all three brain specimens had a normal fresh brain weight. Time from death until fixation in 10% formaldehyde ranged from 24 hours to 72 hours, a time window that is associated with preservation of directional water diffusion within formaldehyde-fixed brain tissue (47).

For specimen 1, candidate dAAN nodes were traced on the diffusion-weighted images using guidance from serial histologic sections (hematoxylin and eosin counterstained with Luxol fast blue) and selected immunohistochemistry sections (tyrosine hydroxylase for dopaminergic neurons and tryptophan hydroxylase for serotonergic neurons). Each set of diffusion images (diffusion-weighted images [DWI], apparent diffusion coefficient [ADC] map, fractional anisotropy [FA] map, color FA map, and non-diffusion weighted images [b=0]) was compared to its corresponding stained sections to ensure that radiologic dAAN nodes shared the same location and morphology as the dAAN nuclei identified by histology and immunohistochemistry (Figs. 1, S4, S5). For specimens 2 and 3, the brainstem dAAN nuclei were traced manually on each diffusion MRI dataset with reference to selected histologic and immunohistochemistry sections and canonical atlases (48, 49). All histology and immunostaining data are available at https://histopath.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu.

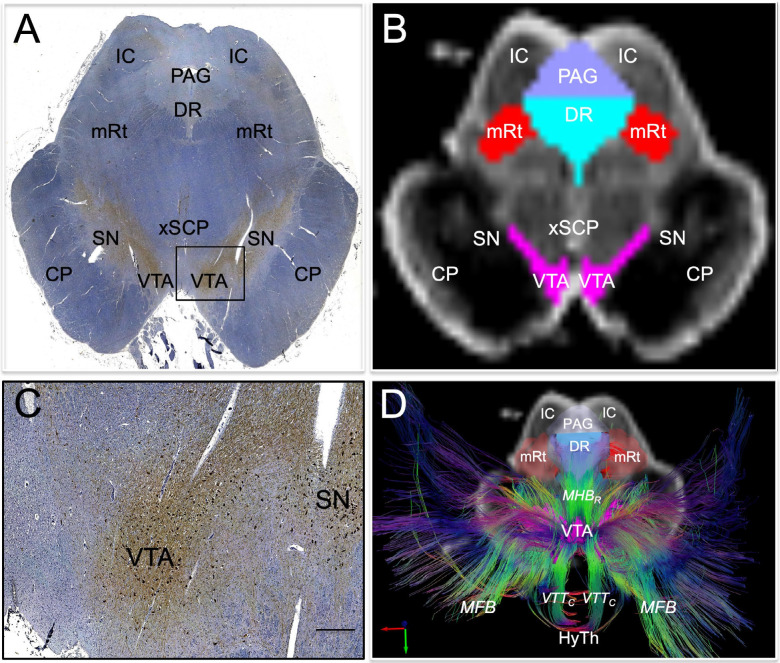

Fig. 1. Histological guidance of node localization and tract construction.

(A) A transverse section through the caudal midbrain of specimen 1 is shown, stained with tyrosine hydroxylase and counterstained with hematoxylin. The tyrosine hydroxylase stain identifies dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA). A zoomed view of VTA neurons located within the rectangle in (A) are shown in (C; scale bar = 100 μm). The corresponding non-diffusion-weighted (b=0) axial image from the same specimen is shown in (B). VTA neurons are manually traced in pink, based upon the tyrosine hydroxylase staining results, and additional arousal nuclei are traced based on the hematoxylin and eosin/Luxol fast blue stain results: DR = dorsal raphe; mRt = mesencephalic reticular formation; PAG = periaqueductal grey. Deterministic fiber tracts emanating from the VTA node are shown in (D) from the same superior view as panel (B). The tracts are color-coded by direction (inset, bottom left) and the DR and mRt nodes are semi-transparent so that VTA tracts can be seen passing through them via the mesencephalic homeostatic bundle, rostral division (MHBR). VTA tracts also connect with the hypothalamus (HyTh), thalamus, basal forebrain, and cerebral cortex via multiple bundles: MFB = medial forebrain bundle; VTTC = ventral tegmental tract, caudal division. Additional abbreviations: CP = cerebral peduncle; IC = inferior colliculus; SN = substantia nigra; xSCP = decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncles.

To facilitate reproduction of our methods, we detail the neuroanatomic boundaries of all candidate dAAN nodes in Tables S2-S6. In addition, we provide a comprehensive summary of our anatomic approach in the Supplementary Methods, including a discussion of how the neuroanatomic borders of our candidate dAAN nodes relate to those defined in canonical atlases (50–52) and how they differ from those of the nodes distributed in version 1.0 of the Harvard Ascending Arousal Network Atlas (9). Based on the updated neuroanatomic nomenclature and nodal anatomic characteristics reported here, we release version 2.0 of the Harvard Ascending Arousal Network Atlas (Video S1) as a tool for the academic community (doi:10.5061/dryad.zw3r228d2; download link: https://datadryad.org/stash/share/aJ713eXY12ND56bzOBejVG2jmOFCD2CKxdSJsYWEHkw)

Specimen 1 was scanned at 600 μm resolution as a dissected specimen, consisting of the rostral pons, midbrain, hypothalamus, thalamus, basal forebrain, and part of the basal ganglia (9). Specimens 2 and 3 were scanned at 750 μm resolution as whole brains. Diffusion data from all three specimens were processed for deterministic fiber tracking for qualitative assessment of tract trajectories, and diffusion data from specimens 2 and 3 were processed for probabilistic fiber tracking for quantitative assessment of connectivity. Probabilistic data for Specimen 1 were not analyzed because differences in scanning parameters and specimen composition – (i.e., dissected versus whole brain) precluded quantitative comparison. We performed deterministic tractography to assess qualitative anatomic relationships of dAAN tracts, and probabilistic tractography to measure quantitative dAAN connectivity properties.

Criteria for structural connectivity and anatomic classification of dAAN pathways

Structural connectivity was defined using a two-step process that incorporated the quantitative probabilistic data and qualitative deterministic data. First, we performed a quantitative assessment for the presence of a connection linking each node-node pair using the probabilistic data for specimens 2 and 3 (see statistical analysis section of the Materials and Methods). A significant quantitative connection requires a connectivity probability measure that exceeds the 95% confidence interval of connectivity with two control regions that are unlikely to have connectivity with dAAN nodes based on prior animal labeling studies (e.g., (53)): basis pontis and red nucleus. If this a priori criterion was met in the probabilistic analysis, we then qualitatively assessed the deterministic tractography data for all three specimens for visual confirmation of tracts connecting each pair of candidate nodes. Node-node pairs that met both the probabilistic and deterministic criteria were considered to have inferential evidence for a structural connection, while node-node pairs that met one, but not both, criteria were considered to have uncertain connectivity.

We then classified the structural connectivity between all candidate node-node pairs based on the anatomic trajectories and nomenclature of subcortical bundles previously defined in humans and animals (9, 54): DTTL = dorsal tegmental tract, lateral division; DTTM = dorsal tegmental tract, medial division; LFB = lateral forebrain bundle; MFB = medial forebrain bundle; VTTC = ventral tegmental tract, caudal division; VTTR = ventral tegmental tract, rostral division (Fig. 2). Next, we classified all dAAN pathways as projection, association, or commissural, providing a neuroanatomic taxonomy for the subcortical dAAN, akin to that of cortical networks whose connections are classified in these terms (55). Using the brainstem as the frame of reference for classifying dAAN pathways, we defined projection fibers as those that project from brainstem nuclei to rostral diencephalic nuclei, basal forebrain nuclei, and/or cortical regions that mediate consciousness (i.e., DMN nodes). Association fibers connect brainstem nuclei to ipsilateral brainstem nuclei, and commissural fibers cross the midline to connect with contralateral brainstem nuclei.

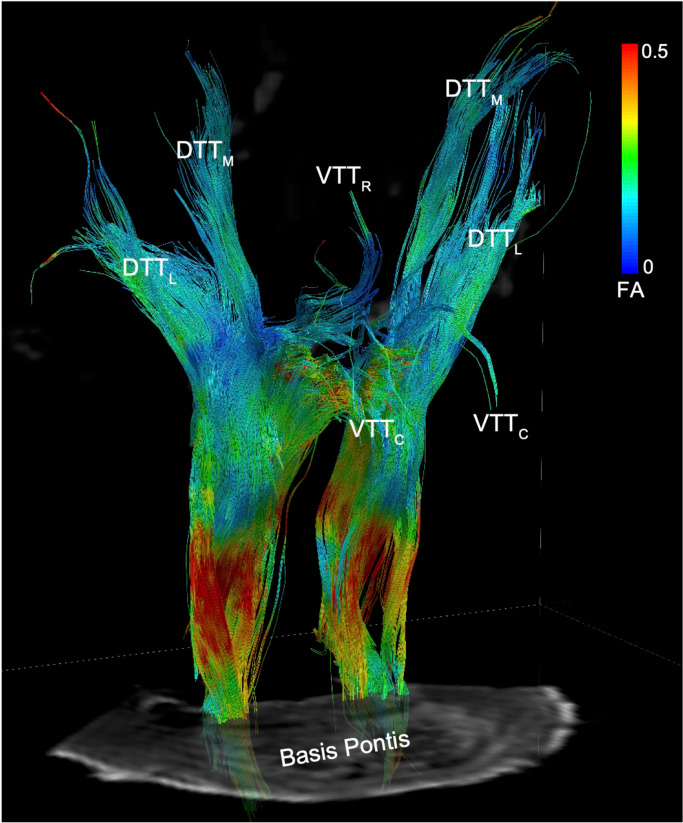

Fig. 2. Reticular pathways of the human default ascending arousal network.

Deterministic tractography results from a seed region in the mesencephalic reticular formation (mRt), the brainstem region stimulated by Moruzzi and Magoun in their seminal investigations of the reticular activating system (13), are shown from a right ventro-lateral perspective in Specimen 1. Tracts are color-coded by the fractional anisotropy (FA) along each segment (inset color bar). Tracts are superimposed upon a non-diffusion-weighted (b=0) axial image at the level of the mid-pons. The fiber tracts emanating from mRt travel in the ponto-mesencephalic tegmentum and connect with the thalamus, hypothalamus, and basal forebrain via the following bundles: DTTL = dorsal tegmental tract, lateral division; DTTM = dorsal tegmental tract, medial division; VTTC = ventral tegmental tract, caudal division; VTTR = ventral tegmental tract, rostral division.

Projection pathways of the dAAN

Deterministic tractography analysis of the three specimens revealed that tracts emanating from all dAAN candidate brainstem nuclei formed well-defined projection pathways that coursed through the rostral brainstem, diencephalon, and forebrain. Each pathway contained intermingled tracts from reticular nuclei (i.e., pontine and mesencephalic reticular formations) and extrareticular nuclei (e.g., monoaminergic, cholinergic, and glutamatergic nuclei), though the distributions of reticular and extrareticular tracts within each pathway differed (Fig. 3).

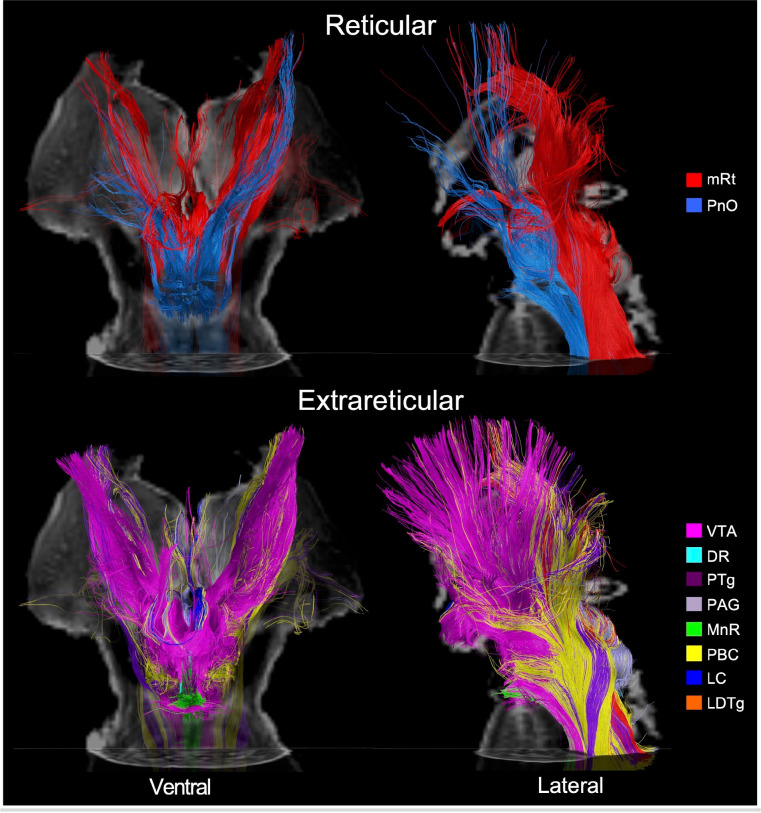

Fig. 3. Reticular and extrareticular tracts of the default ascending arousal network.

Deterministic fiber tracts emanating from the reticular arousal nuclei are shown in the top panels. Fiber tracts emanating from extrareticular arousal nuclei are shown in the bottom panels. All tracts are from specimen 1 and superimposed on an axial non-diffusion-weighted (b=0) image at the level of the mid-pons. Additionally, the tracts in the ventral perspective (left column) are superimposed on a coronal b=0 image at the level of the mid-thalamus, and the tracts in the left lateral perspective (right column) are superimposed on a sagittal b=0 image located at the midline. All tracts are color-coded according to their nucleus of origin (inset, right). Abbreviations are described in Table 1.

All candidate brainstem nodes connected with at least one candidate hypothalamic, thalamic, or basal forebrain node based on confidence interval testing (Table 2). Quantitative connectivity data are provided in Tables S7-S10 for all projection pathways. The projection pathways that connected candidate brainstem dAAN nodes with thalamic, hypothalamic, and basal forebrain dAAN nodes are shown in Fig. 3. The projection pathways connecting candidate brainstem dAAN nodes with cortical DMN nodes are shown in Fig. 4. A projection fiber connectogram with averaged CP values for specimens 2 and 3 is shown in Fig. 5.

Table 2. Projection pathways connecting brainstem dAAN nodes with thalamic, hypothalamic, and basal forebrain dAAN nodes, as well as cortical DMN nodes.

For connections that met both the probabilistic and deterministic criteria for a structural connection, we assessed the deterministic fiber tracts linking each pair of nodes for their anatomic trajectories and classified them using previously defined nomenclature (9, 54): DTTL = dorsal tegmental tract, lateral division; DTTM = dorsal tegmental tract, medial division; LFB = lateral

| Brainstem Node | Thalamus | Hypothalamus | Basal Forebrain | Default Mode Network | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL | Ret* | PaV | TMN | LHA | SUM | BNM/SI | DBB | PMC | MPFC | IPL | LT | MT | |

| mRt | DTTM | DTTL DTTM | VTTR | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | LFB | MFB | LFB | UC | LFB |

| VTA | DTTM | UC | VTTR | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | UC | LFB | MFB | LFB | LFB | LFB |

| PAG | DTTM | DTTL DTTM | VTTR | --- | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | LFB | UC | LFB | LFB | LFB |

| PTg | DTTM | DTTL DTTM | VTTR | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | LFB | MFB | UC | LFB | LFB |

| DR | DTTM | DTTL | VTTR | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | LFB | UC | UC | UC | LFB |

| PnO | DTTM | DTTL DTTM | --- | --- | VTTC | --- | VTTC | --- | LFB | MFB | UC | UC | --- |

| PBC | DTTM | DTTL DTTM | UC | VTTC | VTTC | --- | VTTC | UC | LFB | MFB | LFB | UC | UC |

| MnR | --- | --- | --- | --- | VTTC | --- | VTTC | --- | LFB | MFB | LFB | UC | --- |

| LC | UC | UC | UC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | VTTC | UC | LFB | UC | UC | UC | UC |

| LDTg | UC | UC | --- | VTTc | VTTc | VTTc | UC | VTTc | UC | UC | UC | UC | UC |

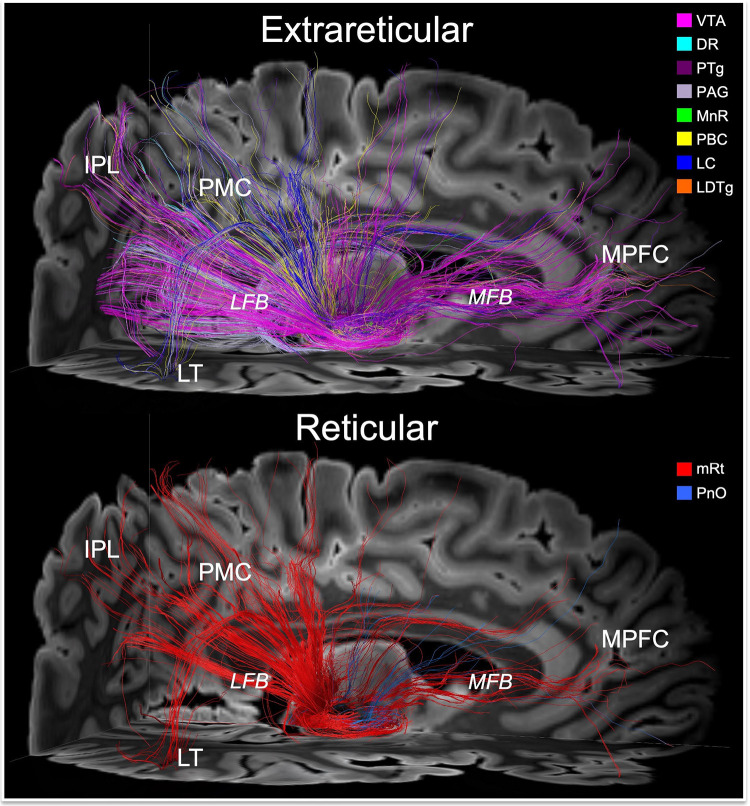

Fig. 4. Connections linking brainstem nodes of the default ascending arousal network with cortical nodes of the default mode network.

Deterministic fiber tracts emanating from the extrareticular and reticular arousal nuclei are shown in the top and bottom panels, respectively. All tracts are shown from a right lateral perspective and superimposed upon an axial non-diffusion-weighted (b=0) image at the level of the rostral midbrain and a sagittal b=0 image to the right of the midline. Tract colors and abbreviations are the same as in Fig. 3. Both the extrareticular and reticular brainstem arousal nuclei connect extensively with cortical nodes of the default mode network, including the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), posteromedial complex (PMC; i.e., posterior cingulate and precuneus), inferior parietal lobule (IPL), and lateral temporal lobe (LT). The primary pathway that connects the brainstem arousal nuclei to MPFC is the medial forebrain bundle (MFB). The primary pathway that connects the brainstem arousal nuclei to the PMC, IPL and LT is the lateral forebrain bundle (LFB).

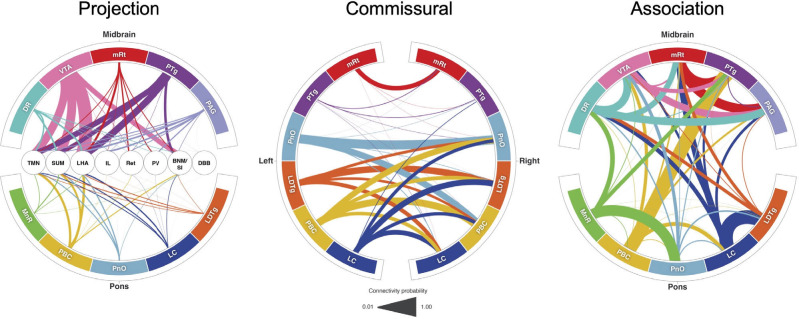

Fig. 5. Default ascending arousal network connectograms.

Projection pathways (left) connect brainstem nodes to hypothalamic, thalamic, and basal forebrain nodes. Commissural pathways (middle) connect contralateral brainstem nodes. Association pathways (right) connect ipsilateral and/or midline brainstem nodes. Brainstem dAAN nodes are shown in the outer ring of all connectograms. In the projection connectogram, the hypothalamic, thalamic and basal forebrain nodes are shown in the center: TMN = tuberomammillary nucleus; LHA = lateral hypothalamic area; IL = intralaminar nuclei; Ret = reticular nuclei; PaV = paraventricular nuclei; BNM/SI = nucleus basalis of Meynert/substantia innominata; DBB = diagonal band of Broca. Line thicknesses in each connectogram is proportional to the connectivity probability (CP) value derived from probabilistic tractography analysis. For clarity of visualization, interspecimen mean in CP measurements is shown in the connectograms. In the commissural connectogram, we show the connections from left-to-right and omit the right-to-left connections for ease of visualization. In the association connectogram, we take a mean of left- and right-sided connectivity for bilaterally represented nodes. We do not show a connectogram for projection pathways to the DMN nodes because the connectivity probability values are lower than for diencephalic and forebrain projection pathways (Table S10), such that connections would not be visualizable at this scale.

The qualitative trajectories of projection pathways connecting these nodes, as assessed by deterministic tractography, were consistent in all three specimens. All midbrain candidate nodes connected with IL via DTTM and with PaV via VTTR. All midbrain nodes except VTA (which showed uncertain connectivity) connected with Ret via DTTL. Connectivity between pontine candidate nodes and the thalamic candidate nodes was more limited, with only PnO and PBC connecting with IL and Ret, and with MnR, LC, and LDTg showing either absent or uncertain connectivity with thalamic nodes (see Discussion for potential explanations of the latter finding).

Structural connectivity with all three candidate hypothalamic nodes (TMN, LHA, and SUM) via VTTC was observed for mRt, VTA, PTg, DR, LC, and LDTg, whereas other brainstem nuclei connected with one (PnO, MnR) or two (PAG, PBC) candidate hypothalamic nodes. All midbrain and pontine candidate nodes connected with the LHA node of the hypothalamus via VTTC. Structural connectivity with the NBM/SI node of the basal forebrain was observed for all midbrain and pontine candidate nodes except LDTg via VTTC. All brainstem nodes except VTA, PnO, PBC, MnR, and LC connected with the DBB node of the basal forebrain via VTTC.

All cortical DMN nodes showed structural connectivity with at least 3 of the 10 candidate brainstem dAAN nodes. The PMC (i.e., posterior cingulate and precuneus) was the DMN node with the most extensive connections to brainstem dAAN nodes (all except LDTg), via the LFB. The MPFC node of the DMN was connected with all brainstem dAAN nodes except PAG, DR, LC and LDTg, via the MFB. The IPL node of the DMN connected with mRt, VTA, PAG, PBC, and MnR via LFB. The MT node of the DMN was connected with all midbrain nodes via a temporal branch of the LFB, and the LT node of the DMN was connected with all midbrain nodes except mRt. There were no connections between LT or MT and the pontine candidate dAAN nodes. We observed a large contribution of extrareticular connections, dominated by VTA tracts, to the MPFC via the MFB (Fig. 4). Brainstem connections with IPL and PMC traveled in a parietal branch of the LFB, with similar connectivity contributions from VTA, PAG and mRt (Fig. 4).

Association pathways of the dAAN

Deterministic and probabilistic tractography analyses revealed connections linking all candidate brainstem nodes with at least one ipsilateral or midline brainstem node (Fig. 5). As with the projection fiber pathways, the association fiber pathways were similar between specimens. Extensive connectivity between midline, left-sided, and right-sided brainstem candidate dAAN nodes (both reticular and extrareticular) was observed (Fig. 6 and Video S2). Quantitative connectivity data from the probabilistic tractography analyses of association pathways are provided in Tables S11, S12, and S13.

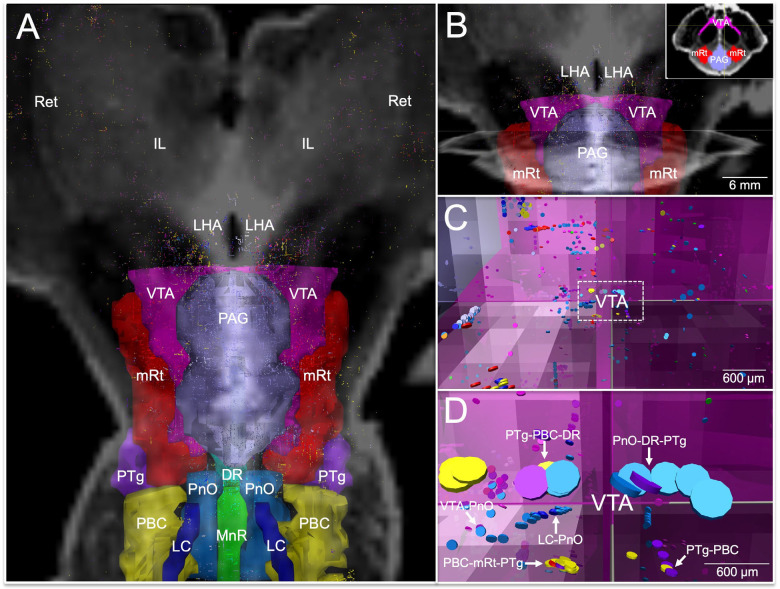

Fig. 6. Connections linking association pathways of the default arousal network.

All candidate brainstem dAAN nodes and their tract end-points are shown from a dorsal perspective in (A), superimposed upon a coronal non-diffusion-weighted (b=0) image at the level of the mid-thalamus. Tract end-points represent the start-points and termination-points of each tract (i.e., there are two end-points per tract). All tract end-points are color-coded by the node from which they originate, and the nodes are rendered semi-transparent so that end-points can be seen within them. In (A), tract end-points are seen within each brainstem candidate node, as well as in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), intralaminar nuclei of the thalamus (IL), and reticular nuclei of the thalamus (Ret). A zoomed-in view of the tract end-points within the ventral tegmental area (VTA), periaqueductal grey (PAG), and mesencephalic reticular formation (mRt) is shown in (B), superimposed upon the same coronal b=0 image as in (A), as well as an axial b=0 image at the intercollicular level of the midbrain. Low-zoom and high-zoom views of tract end-points (appearing as discs) within VTA are shown in (C) and (D), respectively; the axes shown in (B, C, and D) are identical and are located at the dorsomedial border of the VTA node, as shown in the Panel B inset. In (C and D), the perspective is now ventral to the PAG, just at the dorsomedial border of the VTA, as indicated by the axes. Tract end-points from multiple candidate brainstem dAAN nodes are seen overlapping within the VTA and along its dorsal border (arrows): pedunculotegmental, parabrachial complex, and dorsal raphe (PTg-PBC-DR); pontis oralis, DR, and PTg (PnO-DR-PTg); VTA-PnO; PBC-mRt-PTg; locus coeruleus and PnO (LC-PnO); and PTg-PBC. Tract end-point overlap implies that that the beginning and/or endpoints of two tracts are in very close proximity, suggesting extensive connectivity via association pathways between ipsilateral and midline dAAN nodes with the VTA.

Commissural pathways of the dAAN

We observed fewer connections in the commissural analyses as compared to the projection or association analyses. Whereas projection and association tracts were distributed in multiple discreet pathways (e.g., DTTM, DTTL, VTTR, VTTC), the commissural tracts were mostly seen within a single pathway traveling across the posterior commissure in the midbrain (Fig. 7). Additional commissural tracts outside the posterior commissure, particularly those in the pons, did not coalesce into discrete bundles of tracts. Quantitative connectivity data from the probabilistic tractography analyses of commissural pathways are provided in Table S14.

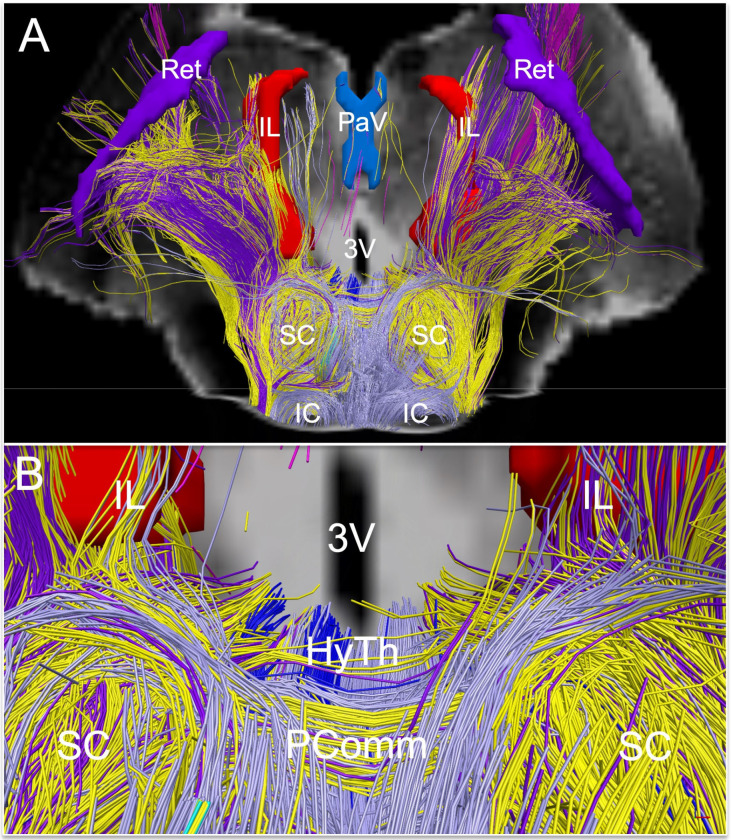

Fig. 7. Extrareticular commissural and projection pathways of the default ascending arousal network.

Deterministic fiber tracts emanating from extrareticular arousal nuclei are shown from a dorsal perspective in (A) and a zoomed dorsal perspective in (B), superimposed on a coronal non-diffusion-weighted (b=0) image at the level of the mid-thalamus. Tract color-coding is identical to that in Fig. 3. Projection fibers are seen connecting with the hypothalamus (HyTh; individual hypothalamic nuclei not shown for clarity), and thalamic arousal nuclei: intralaminar nuclei (IL), paraventricular nuclei (PaV), and reticular nuclei (Ret). Commissural fibers cross the midline via the posterior commissure, with a high contribution of commissural fibers from the parabrachial complex (yellow), pedunculotegmental nucleus (dark purple), and periaqueductal grey (light purple).

Functional connectivity between the dAAN and DMN

We used 7 Tesla resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) data from 84 healthy control subjects scanned in the Human Connectome Project (HCP) (56) to investigate the functional connectivity of the DMN with subcortical dAAN nodes. To map the DMN functional connectivity profile for each dAAN node, we used version 2.0 of the Harvard ascending arousal network (AAN) atlas (9) for brainstem nuclei. We used a previously published probabilistic segmentation atlas (57) for thalamic nodes, and an atlas proposed by Neudorfer et al. (58) for basal forebrain and hypothalamus nodes.

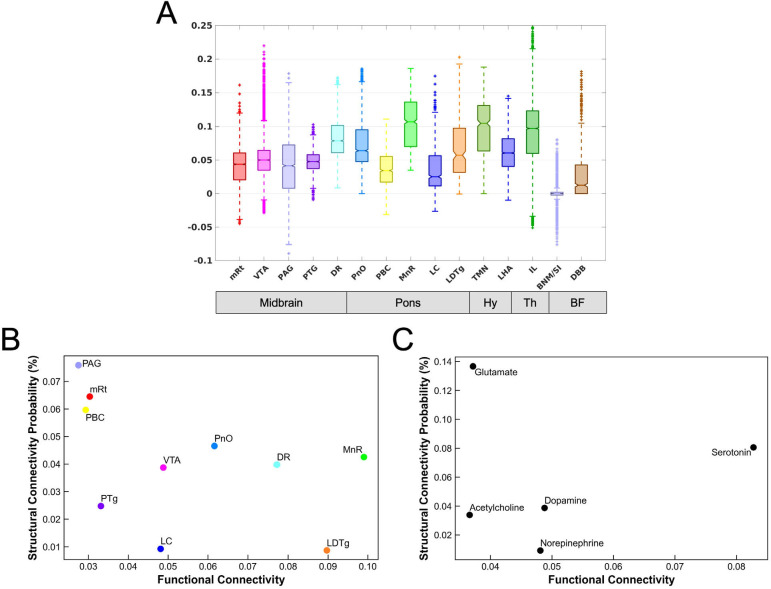

For each candidate brainstem, hypothalamic, thalamic, and basal forebrain node of the dAAN, we plotted the distributions of the DMN connectivity, as shown in Figure 8A. These analyses revealed a broad range of DMN connectivity within each candidate dAAN node. Several dAAN nodes contained voxels with positive correlations and negative correlations (i.e., anti-correlations) with the DMN. Within the brainstem, the VTA demonstrated the highest level of maximal DMN connectivity, while MnR showed the highest median level of DMN connectivity. Within the hypothalamus, thalamus and basal forebrain, the IL nucleus in the central thalamus demonstrated the highest level of maximal DMN connectivity, while the TMN nucleus in the hypothalamus showed the highest median level of DMN connectivity.

Fig. 8. Functional connectivity between subcortical nodes of the default ascending arousal network and cortical nodes of the default mode network and their relationship to structural connectivity.

(A) Boxplots of the DMN functional connectivity for each dAAN node. Y-axis represents the strength of functional connectivity (unitless) relative to the cortical DMN connectivity measured by the NASCAR method. VTA voxels showed the highest level of maximal functional connectivity with the DMN, while MnR had the highest level of median connectivity with the DMN. (B) Scatter plot between the mean of functional connectivity (x-axis) and the structural connectivity probability (y-axis) for each brainstem nucleus. (C) The counterpart grouped by the predominant type of neurotransmitter for each node: cholinergic = PTg and LDTg; dopaminergic = VTA; glutamatergic = PBC, mRt, and PnO; noradrenergic = LC; serotonergic = MnR and DR.

Given the complex relationship between structural and functional connectivity in cortical networks (59, 60), and the lack of data regarding structural-functional connectivity associations in subcortical networks, we plotted the relationship between functional connectivity mapped with in vivo 7 Tesla fMRI and structural connectivity mapped with ex vivo diffusion MRI (Figure 8B, C) for connections between brainstem dAAN nodes and the cortical DM. In these analyses, the DMN was analyzed as a single target ROI. These structural-functional correlation plots revealed that several dAAN nodes, such as LDTg, MnR, and DR, had a high ratio of functional to structural connectivity, whereas other dAAN nodes, such as PAG, mRt, and PBC, had a high ratio of structural to functional connectivity. When grouping dAAN nodes by neurotransmitter system, serotonin and norepinephrine had high ratios of functional to structural connectivity, whereas glutamate had a high ratio of structural to functional connectivity.

DISCUSSION

In this multimodal brain imaging study, we map the connections of a proposed subcortical network that sustains resting wakefulness in human consciousness. We provide evidence for a human default ascending arousal network (dAAN) comprised of interconnected nodes linking brainstem, hypothalamic, thalamic, and basal forebrain nuclei that are known from prior animal and human studies to sustain resting wakefulness. Further, we identified patterns of extensive structural and functional interconnectivity between subcortical dAAN nodes and cortical DMN nodes, providing a putative architecture for the integration of arousal and awareness in human consciousness. Consistent with prior human (61) and animal (16, 18, 19, 62) studies, convergent structural connectivity data from ex vivo diffusion MRI tractography and functional connectivity data from in vivo 7 Tesla resting-state fMRI revealed that a midbrain dAAN node – the dopaminergic VTA – is a widely connected hub node at the nexus of subcortical arousal and cortical awareness networks. Yet connectivity maps also revealed variable relationships between structural and functional connectivity of dAAN nodes, with serotonergic and noradrenergic nodes showing higher levels of functional connectivity with the DMN than would be expected based on their structural connectivity. These observations provide a basis for further investigation of the structural and functional brainstem properties that modulate the human DMN. We release all imaging data, immunohistochemistry data and network-based autopsy methods, including an updated atlas of dAAN brainstem nodes, to support efforts to map the connectivity of human consciousness.

The VTA is a widely connected dAAN node

The VTA displayed extensive connectivity with other subcortical dAAN nodes and with cortical DMN nodes via multiple projection, association, and commissural pathways. Historically, the VTA was believed to mainly modulate behavior and cognition (62), but recent evidence from pharmacologic (63, 64), electrophysiologic (16), optogenetic (18, 19), and chemogenetic (65) methods, as well as behavioral experiments in dopamine knock-out mice (66), indicate that the VTA also modulates wakefulness. Functional connectivity studies from humans with disorders of consciousness further support the idea that the VTA modulates states of arousal, specifically via interactions with cortical DMN nodes (17). Our ex vivo diffusion MRI findings provide a structural basis for these functional observations in animals and humans, and our in vivo rs-fMRI findings provide further evidence for VTA-DMN connectivity, as VTA voxels showed the highest level of maximal functional connectivity of any brainstem dAAN node. These synergistic structural-functional connectivity findings solidify the role of dopaminergic VTA neurons in modulation of wakefulness, and hence consciousness (67).

Our observations supporting the role of the VTA as a potential dAAN hub node also reinforce ongoing efforts to target the dopaminergic VTA in therapeutic trials for patients with disorders of consciousness. Dopamine agonists and reuptake inhibitors are amongst the most commonly used pharmacologic therapies for patients with disorders of consciousness (68), and there is growing interest in using dopaminergic neuroimaging biomarkers to select patients for targeted therapies in clinical trials (69–71). The dAAN connectivity map and neuroimaging tools released here can thus be used to inform the design of future therapeutic trials and to expand the therapeutic landscape for patients with disorders of consciousness.

Interconnectivity of the subcortical dAAN and cortical DMN in human consciousness

Connections between brainstem arousal nuclei have been demonstrated using a variety of tract-tracing and electrophysiological techniques in multiple animal species (53, 72–76), but prior evidence of such interconnectivity is limited in the human brain (54, 77). Here, we provide structural and functional connectivity evidence for multiple dAAN association pathways (i.e., connections between ipsilateral brainstem nuclei) and commissural pathways (i.e., connections between contralateral brainstem nuclei) that to our knowledge have not been previously visualized in the human brain. Moreover, we expand upon prior observations pertaining to projection pathways of human brainstem arousal nuclei (i.e., connections between brainstem nuclei and the thalamus, hypothalamus, basal forebrain, and cerebral cortex) (9, 78–80).

We identified four projection pathways that connect the human brainstem to the diencephalon and forebrain: the ventral tegmental tract, caudal division (VTTC); ventral tegmental tract, rostral division (VTTR); dorsal tegmental tract, medial division (DTTM); and the dorsal tegmental tract, lateral division (DTTL). The anatomic trajectories and connectivity patterns of these dAAN projection pathways are consistent with prior studies of human brainstem connectivity (9, 54, 81, 82) and are similar to their rodent (53, 83), feline (76, 84), and primate (75) homologues.

Our observation of direct connections between brainstem arousal nuclei and the cerebral cortex in the human brain are also consistent with extensive evidence in animal species (74, 75, 85–90). We found that the MFB and LFB are the primary pathways by which the human brainstem and cerebral cortex are connected, building upon prior observations about the human MFB (54, 78, 91, 92) and LFB (54). The human MFB travels through the hypothalamus and basal forebrain, carrying short-range tracts that connect with hypothalamic and basal forebrain nuclei via the VTTC. Long-range MFB fibers continue on to the cerebral cortex, connecting with DMN nodes within the frontal lobes. Although elucidation of the functional subspecialization of MFB and VTTC pathways in the human brain awaits future investigation, these structural connectivity results are consistent with wake-promoting brainstem-hypothalamus-basal forebrain circuits in animals (10).

We also observed tracts diverging from the MFB within the hypothalamus and basal forebrain, then entering the anterior limb of the internal capsule and appearing to connect with the frontal cortex. Though these capsular tracts have been observed in prior human tractography studies (78, 93), their anatomic accuracy has been called into question by primate tract-tracing and immunostaining studies that show MFB capsular axons terminating in the basal ganglia, not the frontal cortex (94). Given the possibility that these capsular tracts connecting with the frontal cortex are “false positives” (i.e., anatomically implausible tracts), we do not assign them as being part of the MFB. Rather, all MFB connectivity results (Table 2) and anatomic labels (Figure 4) reported here are based on tracts that pass through the hypothalamus and basal forebrain before connecting with frontal DMN nodes.

We found that the LFB is the primary pathway by which human dAAN nodes connect with the temporo-parietal DMN nodes, including the PMC (i.e., posterior cingulate and precuneus), a hub node within the DMN whose connectivity is believed to be essential for conscious awareness (11). Functional connectivity between the VTA and the PMC was recently shown to modulate consciousness in patients with severe brain injuries and healthy volunteers receiving propofol sedation (61), observations that are supported by our VTA-PMC connectivity findings. Yet we also identified extensive DMN connectivity between multiple brainstem dAAN nodes beyond the VTA, with particularly strong connectivity in the PMC and MPFC nodes. Interestingly, midbrain dAAN nuclei showed more extensive connectivity with DMN nodes than did pontine dAAN nuclei. While a distance effect may partially account for this observation (i.e., the midbrain nodes are located in closer anatomic proximity to the DMN nodes), it is notable that three pontine nodes – PnO, PBC, and MnR – showed the highest connectivity with the MT node of the DMN in specimen 3. The functional significance of differential DMN connectivity patterns between midbrain and pontine dAAN nodes is unknown and requires future studies to evaluate the relative contributions of brainstem dAAN nuclei to modulating the DMN in the resting, conscious human brain.

Anatomic location and neurotransmitter profiles of dAAN nodes

The 10 candidate brainstem dAAN nuclei that we identified from prior animal and human studies of arousal are all localized to the rostral pons and midbrain. The relationship between consciousness and brainstem nuclei in the rostral to mid-pons was demonstrated in Bremer’s classical cerveau isole experiments in cats (95) and subsequently confirmed in brainstem transection studies by Moruzzi (96), Steriade (97) and others. Similarly, lesions in the mid-pons, rostral pons, and midbrain have been observed to cause coma in humans (98–102), whereas lesions in the caudal pons and medulla do not. Although there is evidence for medullary modulation of arousal in animals (103, 104) and medullary connectivity with rostral brainstem arousal nuclei in humans (54), we did not find a definitive brainstem arousal nucleus caudal to the mid-pons that satisfied the a priori criteria for consideration as a candidate dAAN node. The analysis of medullary contributions to wakefulness and consciousness is beyond the scope of this paper and the subject of ongoing work.

Multiple candidate dAAN nodes contain GABAergic neurons, which modulate wakefulness via a variety of electrophysiological mechanisms. Amongst the glutamatergic neurons of the mesencephalic and pontine reticular formations (mRt and PnO), GABAergic neurons exert local inhibitory control upon the larger population of ascending stimulatory neurons (105). These GABAergic neurons may be responsible for the wake-promoting behavioral effects of PnO via local inhibition (i.e., “gating”) of REM sleep-promoting cholinergic neurons (38). Moreover, GABAergic neurons of the thalamic reticular nucleus (Ret) transition from intermittent burst-firing to tonic firing during the transition from slow-wave sleep to wakefulness (106). We found extensive connectivity between Ret and other dAAN nodes, consistent with prior electrophysiologic studies showing that Ret neurons synapse widely with ascending brainstem arousal inputs and receive inputs from arousal neurons of the basal forebrain (107, 108). Our connectivity findings thus reinforce the key role of GABAergic modulation of arousal in the human brain.

Applications of dAAN connectivity maps for patients with disorders of consciousness

We expect that the network-based autopsy methods and connectivity data generated here will advance the study of coma pathogenesis and recovery (1). Classification of projection, association, and commissural pathways within the human dAAN will allow categorization of different combinations of preserved pathways in patients who recover from coma. This effort may ultimately enable identification of the minimum ensemble of nodes and connections that are sufficient for sustaining wakefulness in human consciousness. In addition, the dAAN connectivity measures have the potential to inform prognostication and patient selection for therapeutic trials aimed at stimulating the dAAN and promoting recovery of consciousness (69).

Reemergence of consciousness after severe brain injury does not require the entire set of grey matter nodes and white matter connections that sustain wakefulness in the healthy human brain. Detailed clinico-anatomic studies of patients with focal brainstem lesions and brainstem axonal disconnections who recovered wakefulness after a period of coma convincingly illustrate this point (82, 98, 102, 109, 110), as do a multitude of animal studies showing that recovery of wakefulness is possible after experimental lesioning of brainstem or diencephalic arousal nuclei (111). Even in the classical cerveau isole experiments, in which cats are initially comatose due to transverse transection of the brainstem at the intercollicular level of the midbrain (112), some cats ultimately recover behavioral and electrophysiological evidence of wakefulness after several weeks (113). Similarly, prolonged coma (i.e., ≥ 4 weeks) in human survivors of severe brain injury is extremely rare (114). Thus, identification of ensembles of dAAN connections that are compatible with recovery and receptive to therapeutic stimulation has potential to improve outcomes for patients with severe brain injuries (115).

The precise mechanisms by which residual connections enable reemergence of wakefulness after coma are unknown, but observational and therapeutic studies are beginning to identify specific subcortical circuits that mediate recovery of wakefulness after severe brain injury (1, 82, 116). Complementary evidence from neurophysiologic and cell culture studies suggests that neuronal networks can adapt to perturbations and reestablish normal function (117–119). These plasticity mechanisms provide a basis for functional reorganization of subsets of dAAN nodes in response to structural injury, suggesting that consciousness can be reestablished by variable combinations of network components (1).

These potential mechanisms of dAAN plasticity in humans recovering from coma are also consistent with theoretical models of the resilience and adaptability of neural systems. Modeling experiments suggest that neural systems with high complexity have high measures of degeneracy and redundancy, meaning that different elements within the system can perform the same function (120). These model-based observations are supported by human therapeutic studies in patients with disorders of consciousness (115), which suggest that there are multiple targets for pharmacologic or electrophysiologic reactivation of arousal circuits (17, 23, 121–125). Considering animal evidence for electrical coupling of arousal nuclei (126), one interpretation of these human therapeutic trials is that stimulation of different network nodes may lead to a final common pathway of increased functional coupling within the entire arousal network.

Limitations and methodological considerations

In deterministic and probabilistic tractography, a fiber tract represents an inferential model of axonal pathways based upon measurements of directional water diffusion along these pathways. The number of axons that corresponds to a tract depends partly on the spatial resolution (i.e., voxel size) of the diffusion data. In the experiments reported here, the voxel size was almost 1,000 times larger in dimension than the diameter of a single axon (~600–750 microns versus ~1 micron). Hence, the tractography results reported here do not represent “ground truth” axonal anatomy. All tractography results should be considered inferential and are subject to the inherent methodological limitations of diffusion MRI tractography, which have been well characterized (127–131).

Given these methodological limitations, our tractography-based definition of anatomic connectivity does not prove synaptic connectivity, which will require confirmation in future studies that move from the mesoscale connectome (i.e., ~600 to 750 μm resolution) to the microscale synaptome (i.e., ~1–10 μm), a major area of ongoing study in neuroscience (132). However, there are currently no available methods to integrate our mesoscale human connectome map with prior microscale animal synaptome wiring diagrams (73). Innovations such as CLARITY (133) and polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography (134) provide hope for this endeavor, but an integrated connectome-synaptome map of the dAAN is currently out of reach.

Another limitation is that diffusion tractography cannot determine the direction of electrical signaling within a tract. There is extensive electrophysiological evidence for “top-down” modulation of arousal (135, 136) and cognition (137), and the MFB is known to carry descending fibers alongside its ascending fibers (138). In addition, multiple types of neurons within the arousal network may have bifurcating axons with ascending and descending projections (89). Thus, our use of the term “ascending” is not intended to suggest that arousal is mediated solely by ascending pathways from the brainstem to rostral sites. Rather, homeostatic functions such as arousal are modulated by bi-directional “bottom-up” and “top-down” signaling between the brainstem, diencephalon, basal forebrain, and cerebral cortex.

It is also important to consider that false positive tracts can be generated by a “highway-effect” whereby tracts that run alongside one another can merge into anatomically implausible pathways. Conversely, false negative findings can occur due a variety of factors, including increased distance between nodes and tractography’s low sensitivity for identifying axons with multidirectional branching patterns (139, 140), small diameters (75), and/or lack of myelination (75). These latter anatomic features are known characteristics of the rostral serotonergic, noradrenergic, and cholinergic axonal projections, which may explain the absent or uncertain connectivity findings for MnR, LC, and LDTg (see Table 2). We attempted to mitigate these problems by performing dMRI with a spatial resolution of 600–750 μm and an angular resolution of 60–90 diffusion-encoding directions. Further, we tested for connectivity between each candidate dAAN node and an anatomically implausible control node to empirically derive a “noise window”, and we only considered connections that exceeded this statistical threshold. Yet even with high-resolution data and strict statistical thresholds, the possibility of false positive and false negative structural connectivity remains.

We also acknowledge that the present study does not address functional subspecialization, or fractionation, of different circuits within the dAAN. Given that dAAN nodes contain neurons utilizing multiple neurotransmitters (7), there is substantial intra-nodal functional complexity that is not accounted for in our structural connectivity methods, which treat each node as a singular entity. For example, the PnO contains neurons involved in activation of REM sleep (141), generation of the hippocampal theta rhythm (142), and active movement during waking (143), but here we considered the PnO solely as an arousal nucleus because of its population of wake-promoting GABAergic neurons (38). Similarly, the PTg contains diverse populations of cholinergic, glutamatergic, and GABAergic neurons with different roles in modulation of wakefulness (144). Nodal parcellation of the PnO, PTg and other multi-function nodes will require future dAAN fractionation studies, just as fractionation of DMN nodes was performed in the years following the DMN’s discovery (145, 146).

Conclusions and future directions

We provide insights into the connectivity of a subcortical arousal network that sustains resting wakefulness in the conscious human brain. We found that subcortical dAAN nodes interconnect with cortical DMN nodes, providing a neuroanatomic basis for integration of arousal and awareness in human consciousness. The dAAN connectivity map and neuroanatomic taxonomy proposed here aims to facilitate further study into the role of subcortical arousal pathways in human consciousness and its disorders. The small size and neuroanatomic complexity of the human brainstem renders it inherently difficult to study, but as new neuroimaging tools are developed to investigate human brainstem connectivity (147–152), we expect that it will be possible to refine this dAAN connectivity map and definitively identify the networks that sustain human consciousness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of candidate dAAN nodes

We identified candidate dAAN nodes via four lines of previously published evidence: electrophysiological, gene expression, lesion, and stimulation. Specifically, we identified subcortical nuclei for which prior studies demonstrated any one of the following: 1) tonic activity during resting wakefulness (28, 153); 2) increased Fos staining after periods of arousal (154); 3) lesion-induced loss of resting wakefulness (95); or 4) stimulation-induced arousal (13) (see Table 1). Animal electrophysiology, gene expression, lesion, and stimulation studies were identified using reference lists from text books (28, 111, 155–158), review articles (10, 106, 159–162), and from the authors’ reference libraries.

These a priori criteria do not stipulate that dAAN nodes must release excitatory neurotransmitters. Although the overall influence of the dAAN on the cerebral cortex is activating, multiple lines of theoretical and experimental evidence indicate that inhibitory circuits are essential for the modulation and stability of activating networks (158, 163–165). At a circuit level, GABAergic neurons exert multiple types of inhibition, including feedback, feed-forward and lateral inhibition. These inhibitory mechanisms enhance the nonlinearity and complexity of neural networks, and hence their resiliency and stability during perturbations (28). Of particular relevance to wakefulness, in vivo and in vitro animal studies suggest that GABAergic neurons coordinate the synchronous fast activity of subcortical arousal neurons (7, 135, 162). We therefore consider nodes containing GABAergic inhibitory neurons as candidate dAAN nodes.

Of note, the nodes and connections of the dAAN need not be the same as those that facilitate state changes. For example, the hypothalamic and brainstem nodes of the subcortical “flip-flop switch” that mediates transitions between sleep and wake (161) are not necessarily the same nodes that sustain wakefulness once it is established. Rather, the flip-flop switch may activate a distinct or overlapping set of dAAN nodes once the transition from sleep to wakefulness has occurred. Here, we focus exclusively on the nodes and connections of the dAAN that sustains the resting mode of the wakeful state.

Brain specimen acquisition and processing

Written informed consent for brain donation was obtained postmortem from family surrogate decision–makers, in accordance with a research protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Mass General Brigham. Criteria for brain specimens being included in the study were: 1) no history of neurological illness; 2) no abnormal in vivo brain scan; 3) normal neurological examination documented by a clinician in the medical record prior to death; and 4) normal postmortem gross examination of the brain by a neuropathologist. All specimens were fixed in 10% formaldehyde.

Ex vivo MRI data acquisition

For Specimen 1, we dissected the hemispheres from the diencephalon and basal forebrain, and dissected the cerebellum from the brainstem to fit the specimen into the small bore of a 4.7 Tesla MRI scanner, as previously described (9). The dissected specimen consisted of the rostral pons, midbrain, hypothalamus, thalamus, basal forebrain, and part of the basal ganglia. Specimens 2 and 3 were scanned as whole brains on a large-bore 3 Tesla MRI scanner. Immediately prior to scanning, the specimens were transferred from 10% formaldehyde to Fomblin (perfluropolyether, Ausimont USA Inc., Thorofare, NJ), which reduces magnetic susceptibility artifacts (166).

Diffusion MRI of dissected specimen

Specimen 1 was scanned in a small horizontal-bore 4.7 Tesla MRI scanner (Bruker Biospec), as previously described (9). We utilized a 3-dimensional diffusion-weighted spin-echo echo-planar imaging (DW-SE-EPI) sequence, with 60 different diffusion-weighted measurements at b = 4057 s/mm2. One dataset of 3D DW-SE-EPI data with b = 0 s/mm2 was also acquired to calculate quantitative diffusion properties in each voxel. Additional sequence parameters were: gradient strength = 12.4 G/cm, duration ∂ = 13.4 msec, intertemporal pulse offset Δ = 25 msec, repetition time (TR) = 1000 msec, echo time (TE) = 72.5 msec, and spatial resolution = 562 × 609 × 641 μm. Total diffusion scan time was 2 hours and 10 minutes.

Diffusion MRI of whole brain specimens

Specimens 2 and 3 were scanned as whole brains on a 3 Tesla Tim Trio MRI scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using a 32-channel head coil. To increase diffusion sensitivity on the large-bore 3 Tesla MRI clinical scanner that was required to scan a whole brain specimen, diffusion data were acquired using a 3D diffusion-weighted steady-state free-precession (DW-SSFP) sequence (47, 167). DW-SSFP is an SNR efficient approach that can achieve diffusion weighting without requiring long TE, making it well suited for ex vivo samples characterized by short T2 (168). We acquired 90 diffusion-weighted volumes and 12 b=0 volumes at 750 μm isotropic spatial resolution. Total diffusion scan time was 30 hours and 31 minutes per specimen. In contrast to the classic DW-SE-EPI sequence utilized for specimen 1, the diffusion-weighting for a DW-SSFP sequence is not defined by a single global b value, as it depends on other tissue and imaging properties, such as the T1 relaxation time, the T2 relaxation time, the TR, and the flip angle (167). Using the formulation in (168) and previously reported ex vivo estimates of T1, T2, and diffusivity (D) (T1= 400 ms, T2=45 ms, D=0.08×10−3 mm2/s) we computed an “effective” b-value of 3773 s/mm2 (169).

Cortical surface parcellation of whole brain specimens

We parcellated the cortical nodes of the DMN in whole brain specimens 2 and 3 for the dAAN-DMN connectivity analysis. DMN nodes were parcellated according to the canonical Yeo 7-network atlas (170), as instantiated in the 1000-node Schaefer version of the atlas (171) available at https://github.com/ThomasYeoLab/CBIG/tree/master/stable_projects/brain_parcellation/Schaefer2018_LocalGlobal/Parcellations/project_to_individual.

First, to generate cortical surfaces for identification of DMN nodes, we acquired multi-echo flash (MEF) data at 1 mm isotropic resolution on the 3 Tesla Tim Trio MRI scanner during the same scanning session during which the diffusion data were acquired. Key MEF sequence parameters were TR = 23.00 msec, TE = 2.64 msec, and 6 flip angles of 5° to 30° were collected at 5° increments. Synthetic T1 and proton density (PD) maps were estimated directly from the MEF acquisitions using the DESPOT1 algorithm (172), available through the FreeSurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) utility “mri_ms_fitparms” (173).

Cortical surface generation and neuroanatomic localization of DMN nodes

To generate the cortical surface model, the synthesized PD volume was processed to remove extraneous background noise by thresholding the PD volume to create a mask containing hyperintense voxels. The mask was then subtracted from the initial PD volume to achieve a more homogenous image. Using the intensity-corrected PD volume, we then generated white and grey matter segmentations using the modified Sequence Adaptive Multimodal Segmentation (SAMSEG) pipeline (174). The SAMSEG white and grey matter segmentations were then used to generate the pial and white matter surfaces.

Once the surfaces were generated, we performed surface-based atlas registrations to create labels corresponding to the DMN nodes in the canonical Yeo atlas: posteromedial complex (PMC; i.e., posterior cingulate cortex and precuneus), medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), inferior parietal lobule (IPL), lateral temporal lobe (LT), and medial temporal lobe (MT). To translate the surface-based MEF labels into volumetric diffusion space we used the boundary-based registration (175) method available through FreeSurfer. Using the transformation matrix obtained through coregistration, we then translated our atlas labels from MEF surface space to volumetric diffusion space for further analysis. We then projected the Yeo atlas labels onto those surfaces using a fixed 2 mm distance into the surface via a nonlinear spherical transform (176).

Detailed processing parameters are provided in our code, which we release at https://github.com/ComaRecoveryLab/Network-based_Autopsy. All data were processed using a standard release of FreeSurfer 7.1.2 available at https://github.com/freesurfer/freesurfer and FSL 6.0.3 available at https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki.

Sectioning and staining for histologic-radiologic correlations

Upon completion of ex vivo MRI data acquisition, specimen 1 was divided into seven blocks, which were embedded in paraffin. We then cut serial transverse sections of the rostral pons and midbrain, and coronal sections of the hypothalamus, thalamus, and basal forebrain at 10 μm thickness (LEICA RM2255 microtome, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Every 50th section was stained with hematoxylin-and-eosin for nuclei and counterstained with Luxol fast blue for myelin, yielding a stained section every 500 μm. The purpose of these stains was to define the neuroanatomic location, borders, and morphology of all candidate dAAN nodes. Additionally, 10 μm sections from the midbrain were prepared using tyrosine hydroxylase (Pel-Freez Biologicals; rabbit polyclonal P40101) counterstained with hematoxylin, and 10 μm sections from the pons were prepared using tryptophan hydroxylase (Sigma-Aldrich; mouse monoclonal AMAB91108) counterstained with hematoxylin. Tyrosine hydroxylase more precisely characterizes the location, borders and morphology of the dopaminergic ventral tegmental area (VTA), as detailed in the Supplementary Material. Tryptophan hydroxylase characterized the location, borders and morphology of the serotonergic median raphe (MnR) and dorsal raphe (DR).

Histology-guided neuroanatomic localization of brainstem dAAN nodes

For specimen 1, candidate dAAN nodes (i.e., nodes selected based on the a priori criteria) were traced on the diffusion-weighted images using histological guidance. Each diffusion image was compared to its corresponding histological section to ensure that radiologic dAAN nodes shared the same location and morphology as the histological dAAN nuclei (Figs. S4, S5). Histological nuclei were delineated by visual inspection of their cytoarchitecture with a light microscope and with digitized slides. We then cross-referenced with the Paxinos atlas of human brainstem neuroanatomy for brainstem dAAN nodes (51) and with the Allen Institute atlas of the human brain for thalamic, hypothalamic, and basal forebrain dAAN nodes (52). Since brainstem nuclei change shape, size and contour along the rostro-caudal axis, histological guidance of dAAN node tracing was performed for every axial diffusion image using its corresponding histological section, yielding a 3-dimensional model of brainstem arousal nuclei.

For specimens 2 and 3 the brainstem dAAN nuclei were also traced manually on each diffusion MRI dataset, but with reference to canonical atlases and selected immunostains, not serial immunostains or comprehensive histological data. Specifically, the neuroanatomic boundaries of brainstem nodes were visually confirmed with respect to two reference templates: 1) the ex vivo template of histologically guided nodes generated for specimen 1, which we release here as part of the Harvard Disorders of Consciousness Histopathology Collection (http://histopath.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu); and 2) the Paxinos human brainstem atlas (51).

Histology-guided neuroanatomic localization of diencephalic and forebrain dAAN nodes

Similar to the brainstem nucleus segmentation, we used histological guidance via coronal sections through the diencephalon and basal forebrain to identify the borders of thalamic, hypothalamic, and basal forebrain dAAN nodes on the diffusion MRI dataset for Specimen 1. To segment the thalamic, hypothalamic, and basal forebrain nuclei for specimens 2 and 3, we manually traced each node based on the Allen Institute human brain atlas (52).

Overview of ex vivo diffusion MRI diffusion data processing for tractography

We processed the ex vivo diffusion datasets for deterministic and probabilistic tractography analyses to generate insights into both qualitative anatomic relationships of dAAN tracts and quantitative dAAN connectivity properties. Deterministic tractography yields more visually informative qualitative data about the neuroanatomic relationships between tracts (e.g., sites of tract branching and crossing) (54, 151), whereas probabilistic tractography provides a more reliable quantitative measure of connectivity between nodes because it accounts for uncertainty in tract trajectories and can detect tracts on and past grey matter boundaries (177).

Diffusion data from all three specimens were processed for deterministic fiber tracking, and diffusion data from specimens 2 and 3 were processed for probabilistic fiber tracking. Specimen 1 was excluded from the probabilistic tractography analysis because it was scanned using different acquisition parameters, which precludes comparison of quantitative probabilistic data with Specimens 2 and 3 without complex modelling that falls outside of the scope of these experiments. To optimize consistency across methods, we standardized the deterministic and probabilistic processing parameters wherever possible. For example, we did not apply an FA threshold to the deterministic or probabilistic analyses because low FA has been observed in the rostral brainstem tegmentum (9, 178), and thalamus (179) in the human brain. We confirmed this observation in an FA analysis of tracts emanating from the mRt in specimen 1, which showed low FA in multiple segments of mRt tracts passing through the brainstem tegmentum (Fig. 2. These low FA measurements may be attributable to the complex meshwork of crossing fibers within the brainstem tegmentum (84), varying degrees of myelination within brainstem axons (75), and/or nuclei that are interspersed amongst the axons (51). Additional details regarding deterministic and probabilistic processing parameters, such as the selection of angle thresholds and the rationale for not applying a distance correction, are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Deterministic tractography analysis of dAAN connectivity

For deterministic tractography, diffusion data for all three specimens were processed in Diffusion Toolkit 6.3 (180). Orientation distribution functions (ODFs) for each voxel were obtained utilizing a spherical harmonic q-ball reconstruction approach (181) and whole brain tractograms were generated using the FACT algorithm and the ODF’s principle diffusion directions (182). Q-ball reconstruction accounts for the possibility of multiple diffusion directions within each voxel, thus enhancing detection of crossing, splaying, and/or “kissing” fibers within complex neuronal networks (183, 184). DAAN tracts were isolated manually in TrackVis, version 6.1 (180), using each candidate dAAN nucleus as an inclusion region of interest. Tracts were visually analyzed to determine the trajectories, branching patterns, and anatomic relationships between bundles connecting the candidate dAAN nodes as well as dAAN-DMN connections.

Probabilistic tractography analysis of dAAN connectivity

For probabilistic tractography, diffusion data for the two whole-brain specimens (specimens 2 and 3) were processed using FMRIB’s Diffusion Toolbox, version 6.0.6. Estimates of principle diffusion orientation in each voxel were obtained using the ball-and-stick model (177, 185) in bedpostx with two stick compartments. Tractography was performed using probtrackx with default parameters. Connectivity was analyzed between all candidate dAAN nodes using the “network” flag. For each pair of nodes, 5,000 tracts (i.e., streamlines) were propagated from each voxel within the seed node, and the target node was treated as both a “termination mask” and a “waypoint mask” (54, 151).

Statistical Analysis of Connectivity

We computed an undirected connectivity probability for each pair of nodes (i.e., node A and node B) by performing two analyses: 1) node A was treated as a seed and node B as a target; and 2) node B was treated as a seed and node A as a target. Using this symmetric connectivity model (186), we computed , and :

hence represents the probability of a tract connecting node A and node B, weighted by the number of voxels within each node and invariant to direction (81, 82). Importantly, the symmetric model reduces a potential statistical bias in probabilistic tractography: the probability of a connection between node A and node B being underestimated if node A has widely distributed connectivity. The probability of a tract connecting with node B would therefore decrease as the probability of that tract connecting with other nodes increases. The symmetric model mitigates, though does not eliminate, this potential bias.

Although complete elimination of false-positive tracts (i.e., anatomically implausible connections) is not possible with either probabilistic or deterministic tractography, we attempted to account for the possibility of false-positive tracts by comparing values for each candidate brainstem dAAN node with two control nodes: the basis pontis (BP) and the red nucleus (RN). Based on prior anatomic labeling studies in animal models, BP and RN are not expected to have significant connectivity with the candidate brainstem dAAN nodes (e.g., (53)), as they mainly contain cortico-ponto-cerebellar fibers that connect the cerebellum to the primary motor cortex (and vice versa), the primary function of which is motor activity (187). We established two a priori criteria, both of which must be met, for operationally defining a structural connection between a pair of candidate dAAN nodes (nodes A and B): 1) ; and 2) the 95% confidence interval (CI) for must not overlap with the 95% CI for any of the following-, and .

The 95% CI for each measurement was calculated by modeling as a binomial distribution:

where .

The binomial statistical model depends upon the assumption that the success of each trial (i.e., the likelihood that a tract from the seed will connect with the target) is independent from prior trials. This assumption may not always be valid, because there is a possibility of intra-voxel dependence (i.e., the success of tract 1 launched from voxel 1 may be dependent on the success of tract 2 launched from voxel 1) and inter-voxel dependence (i.e., the success of tract 1 launched from voxel 1 may be dependent on the success of tract 1 launched from voxel 2). Nevertheless, deriving a quantitative model of these dependencies would require accounting for multiple anatomic factors that likely vary from node to node, or even from voxel to voxel, and is therefore beyond the scope of the present study. Crucially, the binomial model likely overestimates variance because it does not account for the aforementioned dependencies. Hence, we believe that the binomial model implemented here is a conservative approach for estimating variance and the 95% CI.

Proposed neuroanatomic taxonomy for the human dAAN

We classified dAAN connections as projection, association, or commissural. This classification system is intended for use as a neuroanatomic taxonomy for the subcortical dAAN, akin to that of cortical networks whose connections are classified in these terms (55). In the cortical classification system, the cortex is the frame of reference for defining fiber pathways. Projection fibers project from the cortex to subcortical regions. Association fibers connect ipsilateral cortical regions, and commissural fibers cross the midline to connect contralateral cortical regions.

Here, we propose that the brainstem is the frame of reference for classifying fiber pathways of the dAAN. As such, projection fibers are defined as those that project from brainstem nuclei to rostral diencephalic nuclei, basal forebrain nuclei, and/or cortical regions that mediate consciousness (i.e., DMN nodes). Association fibers connect brainstem nuclei to ipsilateral brainstem nuclei, and commissural fibers cross the midline to connect with contralateral brainstem nuclei.

7 Tesla resting-state functional MRI of dAAN-DMN connectivity

7 Tesla resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) scans from 84 healthy controls in the Human Connectome Project (HCP) (56) were used in this study. The rs-fMRI data were minimally preprocessed, resampled, and co-registered to the MNI template by the HCP pipeline (188). Grayordinate representations of the data were used for joint analysis of cortical and subcortical connectivity, where cortical data were sampled onto the subject surface, and subcortical data were represented in volumetric space (188). We did not apply any further spatial smoothing to the minimally preprocessed data because typical Gaussian smoothing would mix signals across different functional regions (189), which may cause a significant issue when resolving relationships between nuclei in dAAN (190). Instead, the improved SNR was obtained using a tensor-based group analysis, as described below.

Using our previously developed pipeline (191), we estimated the functional connectivity from dAAN to the canonical DMN. Specifically, we first temporally synchronized the rs-fMRI data of each subject to a group average using the group BrainSync algorithm (192, 193). We further arrange the synchronized data from all subjects along the third dimension (the first dimension is space, and the second dimension is time), forming a 3D data tensor. We then applied the NASCAR tensor decomposition method (194, 195) to discover the whole-brain DMN. The subcortical section was separated from the grayordinate structure and converted to a volumetric NIFTI file.

To extract the connectivity profile for each nucleus in dAAN, we used version 2.0 of the Harvard Ascending Arousal Network (AAN) Atlas (9) for brainstem nuclei, the probabilistic segmentation atlas (57) for thalamic nuclei, and an atlas proposed by Neudorfer et al. (58) for basal forebrain and hypothalamus nuclei to define the regions of interest (ROI). We then, for each ROI, plot the distributions of the DMN connectivity values using box plots. Of note, three candidate diencephalic dAAN nodes – the supramammillary nucleus of the hypothalamus (SUM), the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PaV), and the reticular nucleus of the thalamus (Ret), were not included in the MRI atlases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements: