Abstract

In Streptomyces coelicolor, transcription of the sodF genes, encoding Fe-containing superoxide dismutases, is negatively regulated by nickel. Gel mobility shift assays with sodF1 promoter fragments and cell extracts from the A3(2) strain indicate the presence of a nickel-responsive DNA-binding protein, most likely a transcriptional repressor. The boundary for the Ni-responsive cis-acting region was identified both in vitro and vivo. Ni does not regulate the level of the putative repressor but only the binding competence of this protein.

All aerobically growing organisms encounter toxic derivatives of molecular oxygen and thus are equipped with defense systems against oxidative stress (5, 8). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is an important component of this protective system, disproportionating superoxide anion into dioxygen and hydrogen peroxide (6). Based on the metal ions present in active sites, four groups of SODs have been distinguished; CuZnSOD, MnSOD, FeSOD, and NiSOD (6, 13, 20). Many organisms possess more than one type of SOD. For example, aerobically grown Escherichia coli contains MnSOD and FeSOD in the cytosol and CuZnSOD in the periplasm (1, 17). The regulation of sod gene expression has been best demonstrated for the MnSOD gene (sodA), which is under the control of a number of transcription factors, including SoxRS, Fur, ArcA, Fnr, and IHF (3, 17).

Streptomyces coelicolor Müller contains two types of SOD: NiSOD, encoded by the sodN gene, and FeSOD, encoded by the sodF gene (11, 12). In S. coelicolor A3(2), two FeSOD polypeptides are produced from two separate genes: sodF1, which is identical to the sodF gene of the Müller strain, and sodF2, which differs from sodF1 by about 12% of its nucleotide sequence (2). Expression of these sod genes is differentially regulated by nickel, which increases the expression of the sodN gene at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels and represses the transcription of the sodF genes (2, 11, 12). The details of the regulation of SOD gene transcription by various metals have been studied primarily in E. coli (regulation by manganese and iron) and in yeasts (regulation by copper) (7, 16). However, the antagonistic regulation of two sod genes by a single metal is most pronounced in S. coelicolor.

Ni-dependent transcriptional regulation has been reported in the expression of the hydrogenase gene (hup) in Bradyrhizobium japonicum (14, 15), and a nickel-specific transport system (encoded by nikABCDE) in E. coli (4), in which the nikA operon has been suggested to be repressed by a nickel-responsive regulator, NikR (4). In this study, we investigated the metal specificity of the sodF1 gene regulation in S. coelicolor A3(2) and report the involvement of a nickel-responsive DNA-binding protein, most likely a repressor, in the regulation of sodF1 gene expression.

Effects of various transition metals on sodF1 gene expression.

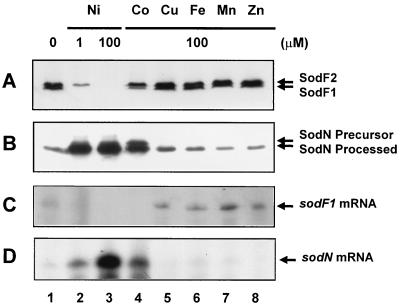

To examine whether transition metals other than nickel regulate SOD expression, the amount of FeSODs in S. coelicolor A3(2) cells grown on a nutrient agar (NA) plate supplemented with various metals was analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig. 1A). Nickel effectively repressed the production of SodF1 even at 1 μM and that of SodF2 at 100 μM (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 3). Cobalt suppressed SodF1 production partially at 100 μM and SodF2 production only marginally (Fig. 1A, lane 4). Other transition metals did not affect the production of either SodF1 or SodF2. In all cases, the level of FeSOD activity correlated well with the amount of SodF polypeptides (data not shown). In contrast, production of NiSOD was increased at 1 μM NiCl2 and 100 μM CoCl2 but was not affected by other metals (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Effects of various transition metals on the expression of FeSODs. S. coelicolor A3(2) M145 cells were grown for 4 days on NA plates containing various transition metals (NiCl2, CoCl2, FeCl2, MnCl2, and ZnCl2) at the indicated concentrations. (A) Cell extract containing 20 μg of proteins was analyzed for the amount of SodF1 and SodF2 proteins by Western blotting using antibodies against the SodF protein of the Müller strain as described previously (2). (B) The amount of SodN proteins was analyzed in parallel by using antibodies against the SodN protein of the Müller strain (12). (C) RNAs prepared from the above-described cells were analyzed for sodF1 mRNA by S1 nuclease mapping using a sodF probe labeled at the 5′ position of the BglII end at position +479 relative to the transcription start point (11). (D) The sodN mRNA was analyzed in parallel by using a sodN probe labeled at the 5′ position of the BglII end at position +402 relative to the transcription start point (12).

The change in levels of sodF1 transcripts in these cells was analyzed by S1 nuclease mapping (Fig. 1C), and the effects of various metals on transcription correlated reasonably well with those on polypeptide production. Therefore, we suggest that sodF1 transcription is very sensitive to inhibition by nickel and less sensitive to inhibition by cobalt. As a comparison, changes in sodN mRNA were analyzed in parallel, and this gene exhibited regulation by nickel and cobalt opposite to that of the sodF genes (Fig. 1D). Comparison of the concentrations of these two metals required for regulation indicated that the minimum concentrations at which SodF1 started to decrease and SodN started to increase were 10 nM NiCl2 and 1 μM CoCl2 (data not shown). The total amount of SodF1 and SodN polypeptides from cells grown at 100 μM CoCl2 was comparable to that at 100 nM NiCl2, implying that nickel is more effective than cobalt by at least 2 orders of magnitude in regulating sodF1 and sodN gene expression.

Ni-responsive protein binding to sodF1 promoter.

To search for the presence of transcriptional regulators responsive to nickel, gel mobility shift assays were performed with cell extracts and sodF1 promoter fragments. Cell extracts were prepared from A3(2) cultures grown with or without added NiCl2 in YEME medium (9). Two different sodF1 promoter fragments of different lengths were generated by PCR using two sets of primers: SODF1N1 (5′-GCG GCA CCA AGC TTT CCG AAC AAC-3′ [the HindIII site at position −130 relative to the transcription start site is underlined]) and SODF1Bam (5′-CAT GGC GGA TCC CTC CGG-3′ [the BamHI site at position +30 is underlined]) were used to generate the longer fragment (−130 to +30), and SODF1N2 (5′-CCG TGC GGG GAA GCT TCG TGT GCG-3′ [the HindIII site at position −60 relative to the transcription start site is underlined]) and SODF1Bam were used to generate the shorter fragment (−60 to +30).

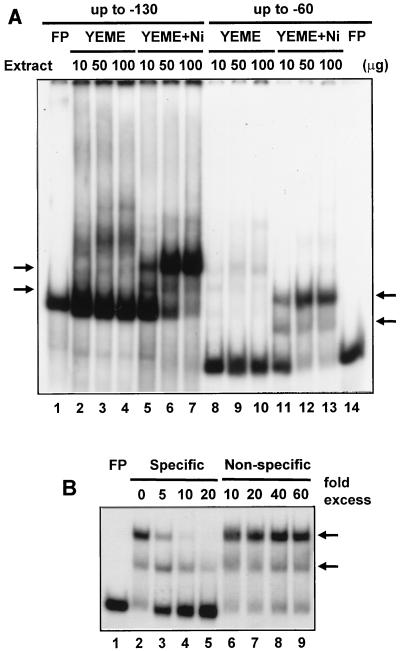

Using the two sodF1 promoter fragments, two distinct complexes were formed by extracts from an Ni-supplemented culture (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 to 7 and 11 to 13). The proportion of the slower-migrating complex increased with greater amounts of cell extract, suggesting that the bound protein is the multimeric form of that in the faster-migrating complex. The binding patterns of the longer and shorter DNA fragments were almost the same, indicating that the binding site is located within the boundary of the shorter fragment. Given that Ni represses sodF1 gene transcription, the Ni-sensitive binding pattern suggests that the bound factor functions as a repressor for the sodF1 promoter. The sodF1 complexes were strong enough to resist 60-fold molar excess of nonspecific competitors, while they began to be competed out by a 5-fold molar excess of unlabeled sodF1 promoter fragments (Fig. 2B). The slower-migrating complex was competed out more easily, consistent with the proposal that it is a multimeric form of the faster-migrating complex.

FIG. 2.

Binding of Ni-responsive protein to sodF1 promoter region. (A) Gel mobility shift assays used cell extracts prepared from S. coelicolor A3(2) M145 cells grown for 2 days in YEME with (lanes 5 to 7 and 11 to 13) or without (lanes 2 to 4 and 8 to 10) 100 μM NiCl2. The indicated amount of cell extract was incubated with the sodF1 DNA probe spanning the region between nt −130 (lanes 1 to 7) or −60 (lanes 8 to 14) and nt +30 relative to the transcription start point. Each binding reaction mixture contained about 10 fmol (0.6 to 1.0 ng) of 32P-labeled DNA fragment (about 104 cpm) in 4 mM Tris · HCl (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA–4 mM dithiothreitol–5 mM MgCl2–20 mM KCl–bovine serum albumin at 0.3 μg/μl–10% (vol/vol) glycerol–1 μg of poly(dI-dC). FP denotes free probe DNA, and arrows indicate retarded bands sensitive to nickel. (B) Specificity of binding to sodF1. The shorter promoter probe was incubated with 50 μg of protein from M145 cells grown in the presence of 100 μM NiCl2 as for panel A. The binding reaction was challenged with a 5- to 60-fold molar excess of either unlabeled promoter fragments (Specific; lanes 3 to 5) or HpaII restriction fragments of pGEM-3Zf DNA (Non-specific; lanes 7 to 9) in the binding buffer.

Presence of Ni-responsive regulatory site as monitored by a sodF1-xylE fusion in vivo.

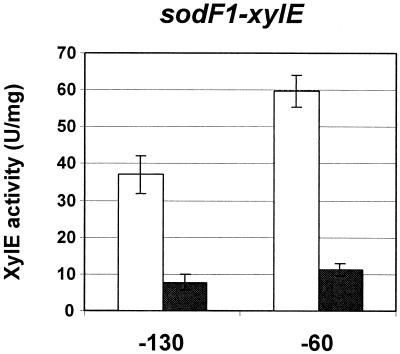

The promoter fragments used in the gel mobility shift assays were also tested for the presence of a functional Ni-sensitive regulatory region in vivo. Each fragment was fused with the xylE reporter gene in low-copy plasmid pXE4 (10), generating pXEF130 and pXEF60, containing 130 and 60 nucleotides (nt) upstream of the sodF1 transcription start site. Cells harboring each plasmid were grown for 20 h on NA plates with or without supplementation with 100 μM NiCl2 and assayed for catechol dioxygenase activity as described previously (10). The level of sodF1 promoter-driven XylE activity decreased about fivefold in the presence of 100 μM NiCl2 (Fig. 3). The repression of sodF1-xylE by 100 μM NiCl2 was elevated up to 10-fold when cells were grown for 2 days instead of 20 h (data not shown). This observation confirms that the critical Ni-responsive negative regulatory site resides between nt −60 and +30 in the sodF1 gene, consistent with the results of the gel mobility shift assay.

FIG. 3.

Negative regulation of sodF1-xylE expression by nickel. The same sodF1 promoter fragments used in Fig. 2 were cloned into plasmid pXE4 upstream of the xylE coding region, generating pXEF130 (−130) and pXEF60 (−60). Recombinant plasmids were introduced into S. lividans TK24; this was followed by selection on R5 plates with thiostrepton at 10 μg/ml. Cell extracts were prepared from transformants grown for 20 h on NA plates with (solid bars) or without (open bars) 100 μM NiCl2 and assayed for catechol dioxygenase activity as described by Ingram et al. (10).

Regulation of sodF1 promoter-binding activity by nickel.

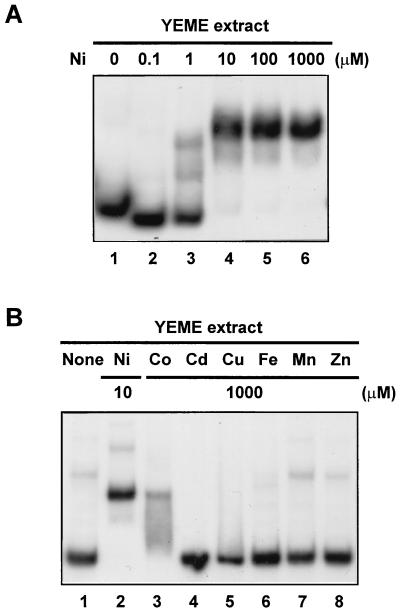

We next examined whether nickel enhances the synthesis or activity of the sodF1 promoter-binding protein. A cell extract from a nickel-deficient culture was incubated with a sodF1 fragment in the absence or presence of nickel in the binding buffer. Retarded complexes appeared when more than 1 μM NiCl2 was added in the buffer (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 to 6). This suggests that the putative sodF1-binding repressor is synthesized and present as an inactive form in Ni-deficient cells and turns into the active binding form in the presence of Ni. Whether Ni exerts its role by direct binding or via a mediator remains to be studied. The effect of other transition metals was also examined, and consistent with the results in Fig. 1, only cobalt allowed in vitro activation of the sodF1-binding protein, although much less efficiently than did nickel (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Activation of the sodF1 promoter-binding activity by nickel in vitro. Extracts (50 μg of protein) of A3(2) M145 cells from a nickel-deficient culture in YEME medium were incubated with the shorter sodF1 promoter fragment (from nt −60 to nt +30) as described in the legend to Fig. 2 in the absence or presence of NiCl2 at the indicated concentrations in the binding buffer (A). The same extract was incubated with the sodF1 promoter in the presence of various transition metals as chloride salts at the indicated concentrations (B).

Our results demonstrate the presence of a sodF1 promoter-binding protein, most likely a transcriptional repressor, whose binding activity was enhanced greatly in response to low levels of nickel and also in response to much higher levels of cobalt. The cis-acting negative regulatory site located between nt −60 and +30 of the sodF1 promoter and the nickel-sensitive binding of a trans-acting factor to this region constitute the nickel-dependent negative regulatory system of sodF1 gene transcription. Various reports suggest that not only the deficiency but also the overexpression of SOD is toxic to cells (18, 19). The antagonistic production of FeSOD and NiSOD regulated by nickel could therefore be a kind of homeostatic regulatory mechanism to maintain the total SOD activity in S. coelicolor within an optimal range. The modulation of the DNA-binding activity of a pre-existing regulator by Ni ensures a rapid response, keeping the total SOD activity relatively constant.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. S. Hahn for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation to the Research Center for Molecular Microbiology, Seoul National University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benov L T, Fridovich I. Escherichia coli expresses a copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25310–25314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung H-J, Kim E-J, Suh B, Choi J-H, Roe J-H. Duplicate genes for Fe-containing superoxide dismutase in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Gene. 1999;231:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compan I, Touati D. Interaction of six global transcription regulators in expression of manganese superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1687–1696. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1687-1696.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Pina K, Desjardin V, Mandrand-Berthelot M-A, Giordano G, Wu L-F. Isolation and characterization of the nikR gene encoding a nickel-responsive regulator in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:670–674. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.670-674.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farr S B, Kogoma T. Oxidative stress responses in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:561–585. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.561-585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fridovich I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:97–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gralla E B, Kosman D J. Molecular genetics of superoxide dismutases in yeast and related fungi. Adv Genet. 1992;30:251–319. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60322-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halliwell B, Gutteridge J M C. Free radicals in biology and medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, United Kingdom: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingram C, Brawner M, Youngman P, Westpheling J. xylE functions as an efficient reporter gene in Streptomyces spp.: use for the study of galP1, a catabolite-controlled promoter. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6617–6624. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6617-6624.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim E-J, Chung H-J, Suh B, Hah Y C, Roe J H. Expression and regulation of the sodF gene encoding iron- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase from Streptomyces coelicolor Müller. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2014–2020. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2014-2020.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim E-J, Chung H-J, Suh B, Hah Y C, Roe J-H. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation by nickel of sodN gene encoding nickel-containing superoxide dismutase from Streptomyces coelicolor Müller. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:187–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim E-J, Kim H-P, Hah Y C, Roe J-H. Differential expression of superoxide dismutases containing Ni and Fe/Zn in Streptomyces coelicolor. Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:178–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0178t.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Maier R J. Transcriptional regulation of hydrogenase synthesis by nickel in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18729–18732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson J W, Fu C, Maier R J. The HypB protein from Bradyrhizobium japonicum can store nickel and is required for the nickel-dependent transcriptional regulation of hydrogenase. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:119–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3251690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Privalle C T, Fridovich I. Transcriptional and maturational effects of manganese and iron on the biosynthesis of manganese-superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9140–9145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Touati D. Regulation and protective role of the microbial superoxide dismutases. In: Scandalios J, editor. Molecular biology of free radical scavenging systems. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 231–261. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weidau-Pazos M, Goto J J, Rabizadeh S, Gralla E B, Roe J A, Lee M K, Valentine J S, Bredensen D E. Altered reactivity of superoxide dismutase in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 1996;271:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yim M B, Kang J H, Yim H S, Kwak H S, Chock P B, Stadtman E R. A gain-of function of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase mutant: an enhancement of free radical formation due to a decrease in Km for hydrogen peroxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5709–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youn H-D, Kim E-J, Roe J-H, Hah Y C, Kang S-O. A novel nickel-containing superoxide dismutase from Streptomyces spp. Biochem J. 1996;318:889–896. doi: 10.1042/bj3180889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]