Abstract

Background:

Laparoscopic appendectomy is one of the most common emergency general surgery procedures in the United States. Little is known about its postoperative outcomes for older adults because appendicitis typically occurs in younger patients. The purpose of this study was to examine the association between age and postoperative complications after appendectomy. We hypothesized that age would have a significant and nonlinear association with morbidity.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of individuals whose laparoscopic appendectomies were recorded in the Veterans Affairs (VA) Surgical Quality Improvement Program (from 2000–2018; n = 14,619) and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (2005–2019; n = 349,909) databases. The primary outcome was 30-day morbidity. We used logistic regression with fractional polynomials to model nonlinear relationships between age and outcomes.

Results:

The median age (interquartile range) of the nonveteran cohort was 36 years (26–51; 8.4% of patients were 65 or older) versus 51 years among veterans (35–63; 21% were 65 or older). For veterans and nonveterans, there was a significant and nonlinear relationship between age and risk of complications. In the nonveteran cohort, the predicted probability (with 95% confidence interval) of postoperative complications was 9.8% (9.7–10.1) at age 65, 11.9% (11.7–12.3) at age 75, and 14.5% (14.1–14.9) at age 85. Among veterans, the risk was 7.5% (6.9–8.1) at age 65, 8.3% (7.6–9.1) at age 75, and 9.1% (8.1–10.1) at age 85.

Conclusion:

For both veterans and nonveterans, older age was associated with a significantly increased risk of postoperative complications. Notably, morbidity within the VA was lower for older adults than in non-VA hospitals.

Introduction

Appendicitis is one of the most common general surgery emergencies, with a global incidence of approximately 100 per 100,000 individuals.1 Although acute appendicitis has traditionally been managed surgically, several recent randomized trials have shown that nonoperative management is a viable strategy for many patients.2,3 When choosing between operative and nonoperative management of appendicitis, it is important for patients to have an accurate estimate of how each treatment option affects morbidity, mortality, and other outcomes. This is particularly important for older adults, who face an increased risk of short- and long-term complications from exposure to surgery and general anesthesia.4–6

Most data on the surgical treatment of acute appendicitis are derived from younger adults because the incidence of appendicitis is higher in those aged <65 years.4 If current demographic trends persist, however, older adults will soon comprise 20%–30% of the U.S. population.7 Therefore, it is critical to understand how the risks of operative management in older adults may differ from risks in younger patients.

A few previous studies have attempted to analyze the relationship between age and outcomes after appendectomy. However, these studies typically model age-related effects by treating age as a dichotomous categorical variable (<65 vs. 65+ years old, for example). This approach is flawed because it provides an overly simplistic view of the age-outcome relationship by assuming that all adults older than 65 are the same. Additionally, the statistical literature has clearly demonstrated that categorizing continuous variables yields biased and inaccurate estimates.8 A more accurate approach requires modeling age as a continuous variable in a fashion that accounts for potentially nonlinear relationships (ie, not every 1-year increase in age carries the same increase in risk of morbidity). Being able to estimate the age-associated risk of postoperative outcomes precisely and accurately will greatly facilitate discussions with patients about their unique operative risk. Consequently, there is an urgent need to better model the relationship between age and outcomes after appendectomy.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between age and postoperative outcomes while accounting for potential nonlinear relationships. We hypothesized that increasing age would be associated with a higher risk of complications after laparoscopic appendectomy, and that nonlinear approaches to modeling would be beneficial in understanding the age–outcome relationship. We believe that this will provide more accurate and useful information that surgeons can employ when discussing risks with their patients.

Methods

Patient selection and data sources

After approval from the institutional review board of the Veterans Affairs (VA) North Texas Health Care System, we obtained records from: (1) the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database from 2005–2019; and (2) the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program (VASQIP) database from 2000–2018. Patients in the VASQIP and NSQIP databases were selected based on the common procedural terminology (CPT) code 44970 for laparoscopic appendectomy. ICD-9 (540, 540.0, 540.9, 541, 542, 543, 543.0, 543.9) and ICD-10 (K35, K35.2, K35.20, K35.3, K35.8, K35.80, K35.89, K35.890, K35.891, K36, K37, K38, K38.1, K38.2, K38.8, K38.9) codes were used to select only patients with non-perforated appendicitis-related diagnoses. NSQIP and VASQIP databases were chosen to get a nationally representative sample of patients with appendicitis. Both datasets provide comprehensive data on both comorbidities and complications across a wide age range of patients with appendicitis. Dates were chosen to reflect the most recently available years from both datasets to represent current practice management of appendicitis.

Exposure

The primary exposure/independent variable of interest was the age of the patient having the appendectomy, modeled as a continuous variable as described herein.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the development of any postoperative or posthospitalization complication within 30 days after surgery. Postoperative complications were identified as defined within in the NSQIP and VASQIP databases as a composite variable, which included the incidence of any wound infection, dehiscence, pneumonia, re-intubation, pulmonary embolus (PE), failure to wean from the ventilator, renal insufficiency/failure, urinary tract infection, stroke, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction (MI), postoperative bleeding that required transfusion, deep venous thrombosis, sepsis/septic shock, and reoperation. We also looked at the association between age and severity of complications, categorized as major or minor based on previously published frameworks.9–11 Major complications were defined as MI, PE, stroke, sepsis/septic shock, organ space infection, deep surgical site infection, failure to wean from ventilator, re-intubation, renal failure, cardiac arrest, wound dehiscence, pneumonia, bleeding, return to the operating room. Minor complications were defined as urinary tract infection, superficial surgical site infection, deep venous thrombosis, and renal insufficiency. Secondary outcomes included mortality, length of stay (LOS), operative time, and failure to rescue (death within 30 days of a complication).

Complicated appendicitis

Our primary analysis only included only uncomplicated appendicitis. However, we completed an additional analysis looking at complicated appendicitis. We included all patients that had undergone laparoscopic appendectomy and used diagnosis codes within NSQIP and VASQIP to define patients with diagnoses consistent with complicated appendicitis. We used ICD-9 code 540.1 ad ICD-10 codes K35.33, K35.32, and K35.21. We then looked at the same primary and secondary outcomes and performed the same analysis as our original cohort.Statistical analysis

We used logistic regression to predict the likelihood of a postoperative complication based on patient age. Because VASQIP (but not NSQIP) provides a variable indicating which hospital performed the operation, we used robust standard errors to account for clustering in the VASQIP data.

Because we hypothesized that the relationship between age and postoperative complications was likely to be nonlinear (ie, not all 1-year increases in age would be associated with the same change in complication rates) we generated 1,000 bootstrap samples to test the association and functional form of the relationship between age and outcomes. Bootstrapping essentially uses the existing dataset to create multiple “different” samples that are populated by drawing observations with replacement from the original dataset. In each bootstrap sample, an observation from the original dataset may appear once, multiple times, or not at all, depending on the probability distribution. Bootstrapping allows us to evaluate whether age is a significant predictor of outcomes in multiple samples instead of only the original sample (ie, we can see how many times out of the 1,000 bootstrap samples that age was significantly associated with outcomes). Consequently, bootstrapping reduces the chances of identifying a false association between the exposure (age) and the outcomes based on chance alone.

Bootstrapping also allows us to see if the relationship between age and postoperative outcomes is best modeled as linear or nonlinear. In each bootstrap sample, we tested the full range of fractional polynomials recommended by Royston and Sauerbrei.12,13 Fractional polynomials facilitate modeling of nonlinear relationships by transforming continuous variables to a family of exponential powers, allowing predicted relationships to follow curvilinear patterns. This often allows for more accurate prediction than a simple linear model when modeling continuous variables across a broad range of values.

To identify the optimal form for modeling, we counted which form/polynomial was selected most frequently across the 1,000 bootstrap samples and compared this with a linear modeling of age. Thus, we were able to determine: (1) whether age was a significant predictor of postoperative complications (P < .05); and (2) which fractional polynomial transformation of age offered the best model fit. After confirming that age was significantly associated with the outcome and identifying the optimal functional form for modeling, we estimated the average marginal effect/probability of the outcome for specific age values of interest (55, 65, 75, and 85+). This represented the averaged predicted probability for a patient at each age to experience a postoperative complication. We then applied these same tactics to our secondary outcomes of mortality, operative time, and length of hospital stay (though we used linear regression for operative time and a Poisson model for LOS). All analysis was done using Stata version 16.1.

Results

Patient characteristics

We assessed a total of 349,909 patients in the NSQIP cohort who underwent laparoscopic appendectomy. Males comprised 51.1% of the NSQIP cohort with a median age of 36 years. In the VASQIP cohort, there were 14,619 patients who underwent laparoscopic appendectomy; 89.1% were males and their median age was 51 years. Differences in demographic characteristics, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, and preoperative comorbidities for both NSQIP and VASQIP patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study patients from the NSQIP and VASQIP databases

| NSQIP, No. (%)* | VASQIP, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Total patients | 349,909 | 14,619 |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 36 (26—51) | 51 (35—63) |

| Male sex | 178,828 (51.1) | 13,026 (89.1) |

| Risk analysis index | 9(4—15) | 17 (9—22) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 26.5 (22.5—31.0) | 28.9 (25.6—32.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 225,299 (64.4) | 9,305 (63.7) |

| Black | 23,349 (6.7) | 1,716(11.7) |

| Hispanic | 52,167 (14.9) | 1,038 (7.1) |

| Other | 18,275 (5.2) | 312 (2.1) |

| Unknown | 30,819 (8.8) | 2,248 (15.4) |

| Albumin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 4.2 (3.9—4.5) | 4.1 (3.8—4.4) |

| White blood cell (cells/mm3), median (IQR) | 12.7 (9.7—15.7) | 12.0 (8.7—15.2) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.83 (0.70—1.00) | 1 (0.86—1.12) |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists class | ||

| 1 | 111,285 (31.8) | 1,492 (10.2) |

| 2 | 189,928 (54.3) | 6,632 (45.4) |

| 3+ | 48,162 (13.8) | 6,494 (44.4) |

| Preoperative ascites | 550 (0.2) | 81 (0.6) |

| Bleeding disorder | 5,821 (1.7) | 663 (4.5) |

| Preoperative diabetes | ||

| None | 333,217 (95.2) | 12,707 (86.9) |

| Oral medications | 9,901 (2.8) | 992 (6.8) |

| Insulin | 6,791 (1.9) | 920 (6.3) |

| Preoperative dialysis | 653 (0.2) | 63 (0.4) |

| Disseminated cancer | 676 (0.2) | 49 (0.3) |

| Preoperative dyspnea | ||

| None | 346,284 (99.0) | 13,830 (94.7) |

| Exertion | 3,280 (0.9) | 713 (4.9) |

| At rest | 345 (0.1) | 63 (0.4) |

| Functional status | ||

| Independent | 348,051 (98.9) | 14,141 (96.7) |

| Partially/totally dependent | 1,858 (1.1) | 476 (3.3) |

| Congestive heart failure | 476 (0.1) | 486 (3.4) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3,168 (0.9) | 1,027 (7.0) |

| Hypertension | 54,948 (15.7) | 5,829 (42.4) |

| Preoperative renal failure | 285 (0.1) | 38 (0.3) |

| Smoking history | 62,490(17.9) | 4,444 (30.4) |

| Steroid use | 4,015 (1.1) | 136 (0.9) |

| Wound classification | ||

| Clean | 6,184(1.8) | 1,247 (8.5) |

| Clean/contaminated | 100,100 (28.6) | 8175 (55.9) |

| Contaminated | 180,558 (51.6) | 2,826 (19.3) |

| Infected | 63,067 (18.0) | 2,371 (16.2) |

| Preoperative wound infection | 537 (0.2) | 87 (0.6) |

| Preoperative weight loss | 494 (0.1) | 113 (0.8) |

| Preoperative sepsis | 28,054 (8.0) | 752 (5.1) |

| Any complication | 21,651 (6.2) | 859 (5.9) |

IQR, interquartile range; NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; VASQIP, Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

All values represent N (%) unless otherwise specified.

Increasing age was associated with a significant increase in postoperative complications

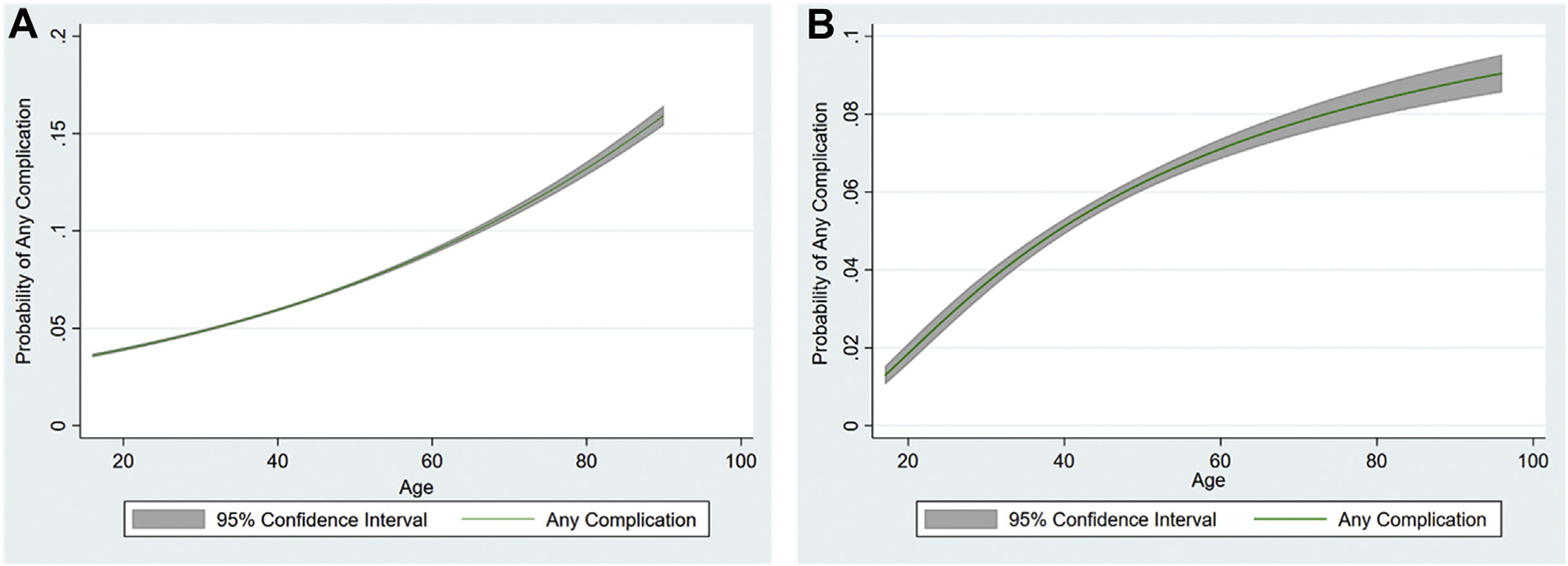

For NSQIP patients, age was found to be a significant predictor of postoperative complications in 100% of the 1,000 bootstrap samples. This indicated an extremely high likelihood that the association between age and complication risk was not due to chance alone, as would be expected in at least 5% of analyses with the traditionally accepted value of P < .05 indicating a likelihood of association. The relationship between age and increasing risk of postoperative complications can be seen in Figure 1, A. At age 55, the average predicted probability (with 95% confidence interval [CI]) of having a postoperative complication was 8.1% (7.9–8.2). At age 65, the probability was 9.8% (9.7–10.1); at age 75, the probability was 11.9% (11.7–12.3); and at age 85, the probability was 14.5% (14.1–14.9).

Figure 1.

Increasing age was significantly and nonlinearly associated with higher risk of postoperative complications for the (A) NSQIP, and (B) VASQIP cohorts. NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; VASQIP, Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

For the VASQIP cohort, age was also shown to be a significant predictor of postoperative complications in all bootstrap samples. As seen in Figure 1, B, the predicted probability (with 95% CI) of a postoperative complication was 6.6% (6.2–7.0) at age 55, 7.5% (6.9–8.1) at age 65, 8.3% (7.6–9.1) at age 75, and 9.1% (8.1–10.0) at age 85. Overall morbidity for VASQIP patients was lower than for NSQIP patients at each age value evaluated.

We also looked at severity of postoperative complications. For the NSQIP cohort, 18,283 (5.3%) patients had a major complication and 5,438 (1.5%) had a minor complication. Similar to the analysis of all complications, we found that the age-outcome relationship was best described using nonlinear associations. For the VASQIP cohort, there were 839 (5.7%) patients that had a major complication and 314 (2.1%) of patients that had a minor complication. Once again, we found a nonlinear association of age with outcomes.

Age was associated with increased mortality after laparoscopic appendectomy

Age was a significant and nonlinear predictor of mortality after laparoscopic appendectomy for both NSQIP and VASQIP patients. For NSQIP patients, as seen in Figure 2, A, the probability (with 95% CI) of death within 30 days of surgery increased with age, and was 0.04% (0.03–0.05) at age 55, 0.12% (0.10–0.14) at age 65, 0.41% (0.35–0.47) at age 75, and 1.7% (1.4–2.0) at age 85. Mortality also increased with age for the VASQIP patients and was slightly higher than for NSQIP patients. As seen in Figure 2, B, the predicted mortality (with 95% CI) was 0.14% (0.06–0.21) at age 55, 0.38% (0.25–0.51) at age 65, 0.95% (0.61–1.30) at age 75, and 2.17% (1.11–3.23) at age 85.

Figure 2.

Age was associated with an increased probability of death in both (A) NSQIP and (B) VASQIP patients. NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; VASQIP, Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Failure to rescue rates were higher for VASQIP compared with NSQIP patients

To investigate potential reasons that VASQIP patients experienced fewer complications but higher mortality than NSQIP patients, we evaluated failure to rescue rates (the incidence of death within 30 days of a postoperative complication) for each cohort. Failure to rescue rates were low for both NSQIP (1.0%) and VASQIP (3.1%) patients, although fewer NSQIP patients died after complications. For the VASQIP patients, we assessed hospital-level variation in failure to rescue rates across the different VA hospitals. Of the 103 hospitals assessed, 77 had a rate of 0%. The remaining 26 hospitals had rates that varied from 3.7%–50%, though VA hospitals with higher failure rates tended to have very few deaths, which makes it difficult to establish stable estimates.

Age was associated with prolonged operative time for laparoscopic appendectomy

For both VASQIP and NSQIP patients, there was a slight increase in operative time associated with greater patient age. In general, operative time was lower in the NSQIP patients compared with VASQIP patients. As seen in Figure 3, A, operative time (with 95% CI) for NSQIP patients was 50.6 minutes (50.5–50.8) at age 55, 51.8 minutes (51.5–51.9) at age 65, 52.8 minutes (52.6–53.1) at age 75, and 53.8 minutes (53.5–54.1) at age 85. The times for VASQIP patients can be seen in Figure 3, B and are as follows: 72.0 minutes (71.2–72. 9) at age 55, 73.5 minutes (72.5–74.6) at age 65, 74.7 minutes (73.5–75.9) at age 75, and 75.7 minutes (74.4–77.0) at age 85. This difference is slightly more pronounced when compared for higher values of patient age. At age 25 the predicted operative time was 46.3 (46.2–46.5) minutes for NSQIP patients and 62.9 (61.4–64.5) minutes for VASQIP patients.

Figure 3.

Age was associated with an increased operative time in (A) NSQIP and (B) VASQIP patients. NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; VASQIP, Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Age was associated with prolonged LOS after laparoscopic appendectomy

Age was associated with an increase in length of hospital stay after surgery for both NSQIP and VASQIP patients. VA patients had longer stays compared with non-VA patients. For NSQIP, as seen in Figure 4, A, the LOS (with 95% CI) was 1.53 days (1.52–1.54) at age 55, 1.89 days (1.87–1.90) at age 65, 2.41 days (2.39–2.43) at age 75, and 3.18 days (3.14–3.22) at age 85. For VASQIP patients, as seen in Figure 4, B, the LOS was 2.72 days (2.67–2.77) at age 55, 3.46 days (3.38–3.53) at age 65, 4.39 days (4.26–4.53) at age 75, and 5.58 days (5.35–5.80) at age 85.

Figure 4.

Age was associated with an increased length of hospital stay in both (A) NSQIP and (B) VASQIP patients. LOS, length of stay; NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; VASQIP, Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Complicated appendicitis

For the VASQIP cohort, there were only 480 patients with a diagnosis consistent with complicated appendicitis. Of those, 48 (10%) patients had a postoperative complication. Given the low effective sample size, we did not complete any further analysis on this cohort.

For the NSQIP cohort, there were 18,876 patients with a diagnosis consistent with complicated appendicitis. Significant nonlinear relationships were found between age and postoperative complications, mortality, and LOS. There was no significant relationship with operative time. As seen in Supplemental Figure 1, the predicted complication rate was 19.0% (95% CI 17.8–20.2) at age 55, 20.1% (95% CI 18.6–21.5) at age 65, and 21.5% (95% CI 19.1–23.9%) at age 75, and 23.6% (95% CI 19.5 0 26.7%). As seen in Supplemental Figure 2, the predicted mortality rate was 0.6% (95% CI 0.4–0.9%) at age 55, 1.2% (95% CI 0.8–1.7%) at age 65, 2.2% (95% CI 1.4–3.1%) at age 75, and 3.8% (95% CI 1.9–5.6%) at age 85. As seen in Supplemental Figure 3, the predicted LOS was 5.2 days (95% CI 5.1–5.3) at age 55, 5.8 days (95% CI 5.6–5.9) at age 65, 6.6 days (95% CI 6.3–6.9) at age 75, and 7.9 days (95% CI 7.3–8.5) at age 85.

Discussion

Our study showed that older age is significantly associated with worse postoperative morbidity after laparoscopic appendectomy. We also noted a strong age-related association with mortality, operative time, and LOS for this common operation. Our findings are significant for any surgeon who seeks to obtain a truly informed consent before performing laparoscopic appendectomy for older adults. Additionally, when contemplating operative versus nonoperative management of appendicitis in older adults, our study offers useful information for choosing the optimal treatment approach. A more direct comparison of operative versus nonoperative treatment of appendicitis would be indicated moving forward. While we can discuss the increased morbidity and mortality with patients, it is prudent to determine if these are acceptable risks when compared with those of nonoperative management of older adults.

Another interesting finding from our study is that morbidity rates at VA and NSQIP hospitals differed and that the overall relationship (shape of the curve) between age and outcomes was also different. Overall, VA hospitals had lower age-related morbidity than NSQIP hospitals, but mortality rates at VA hospitals were slightly higher. Non-VA hospitals did have lower failure to rescue rates after complications, and this may explain the difference in mortality. When looking at rescue rates at individual VA hospitals, however, the majority of hospitals (74.7%) had a rate of 0%. While the rates varied at the remaining hospitals up to 50%, hospitals with higher failure rates had lower case numbers and complication numbers. Most hospitals that had failures had only 1 recorded death after a complication, with 2 hospitals having 2 deaths. Consequently, the data do not offer a stable enough estimate of rescue rates for comparison.

Our findings are generally in line with the relatively small number of previous studies that evaluated outcomes of appendectomy in older adults. One previous study by Rentena et al (2018) looked at those outcomes in veterans aged ≥60 years.14 They did not find any significant difference in complication rates between older and younger patients and also did not find age to be an independent predictor of complications. However, they treated age as a binary variable (60+ vs <60 years), an approach that is known to be suboptimal for modeling complex relationships with continuous variables13,15 Their definition of age also does not reflect the modern understanding of what constitutes “old” versus “young” age. Another study by Kirshtein et al (2009) employed a similar approach of comparing patients aged >60 years versus those who were younger and also did not find a significant difference in complications between older (11.2%) and younger (6.4%; P = .850) patients. However, given the small sample size of this study, it was greatly underpowered to detect differences. A larger sample might have found statistically significant differences even with dichotomized variables.16 These results differ from the findings of Weinandt et al (2020), who looked at 20 years of appendectomies at their hospital (2,060 appendectomies) and found that patients aged >75 years old had a complication rate of 46% compared with a rate of 8% in patients aged <75 years old.17 Additionally, Massarweh et al (2009) looked at over 100,000 elderly patients undergoing abdominal operations and found a steady rise in complication rates with increasing age. For appendectomies, the complication rate at ages 65–69 was 11.2%, and this increased to 18.4% in patients aged >90.18 The differences between these studies and our results highlight the potential flaws in treating complex continuous variables as dichotomous predictors. Although it is certainly easier to model age as a categorical or binary variable, this approach misses the rich relationship between age and key outcomes. Converting continuous variables to categorical variables also significantly decreases statistical power to detect meaningful differences and is subject to arbitrary manipulation by changing the cutoffs used to create each category. It also treats all “old” patients as a block with similar characteristics and risks, ignoring potential changes in risk as age increases or decreases. Our approach, using fractional polynomials, allows for a much richer and more accurate estimation of risk across the age spectrum, and this distinguishes our work from prior studies evaluating outcomes after appendectomy. We are also able to evaluate the overall trend of the age-outcome relationship, which enables surgeons to easily use our figures to see where their particular patients sit on that relationship curve.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. It was a retrospective study and thus likely to be affected by selection and omitted-variable bias. Since VASQIP and NSQIP only contain information on patients who elected to have surgery for appendicitis, it is possible that a differential use of nonoperative management might have affected outcomes. However, there is no particular reason to assume that VA and non-VA hospitals use different criteria for nonoperative management of acute appendicitis. We only looked at laparoscopic appendectomies in this study, and the age–outcome relationship for open appendectomy may be different. We elected to focus on laparoscopic surgery since the vast majority of appendectomies are done using the laparoscopic approach.19 In conclusion, for both VA and non-VA patients, increasing age was associated with significantly increased risk of postoperative complications, mortality, LOS, and operative time. The relationship between age and outcomes was also frequently nonlinear, which means that simple linear models or categorizing age into binary categories represents an oversimplification that is unlikely to reflect the true age–outcome relationship. Our next studies will directly compare outcomes of operative versus nonoperative management of appendicitis on the national level, and will use qualitative techniques to explore potential reasons for differences in VA versus non-VA hospitals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dave Primm of the UT Southwestern Department of Surgery for help in editing this article.

Funding/Support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest/Disclosure

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2022.04.008.

References

- 1.Ferris M, Quan S, Kaplan BS, et al. The global incidence of appendicitis: a systematic review of population-based studies. Ann Surg. 2017;266:237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Saverio S, Sibilio A, Giorgini E, et al. The NOTA Study (Non Operative Treatment for Acute Appendicitis): prospective study on the efficacy and safety of antibiotics (amoxicillin and clavulanic acid) for treating patients with right lower quadrant abdominal pain and long-term follow-up of conservatively treated suspected appendicitis. Ann Surg. 2014;260:109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sippola S, Haijenen J, Grönroos J, et al. Effect of oral moxifloxacin vs intravenous ertapenem plus oral levofloxacin for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: the APPAC II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow W, Clifford YI, Rosenthal RA, Esnaola NF. ACS NSQIP/AGS Best Practice Guidelines: Optimal Preoperative Assessment of the Geriactric Surgical Patient. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/nsqip/acsnsqipagsgeriatric2012guidelines.ashx. Accessed October 20, 2021.

- 6.Mohanty SRR, Russell MM, Neuman MD, Ko CY, Esnaola NF. Optimal Perioperative Management of the Geriatric Patient: Best Practices Guideline from ACS NSQIP/American Geriatrics Society. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/geriatric/acs%20nsqip%20geriatric%202016%20guidelines.ashx. Accessed October 20, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Klopfenstein CE, Herrmann FR, Michel JP, Clergue F, Forster A. The influence of an aging surgical population on the anesthesia workload: a ten-year survey. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:1165–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royston P, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W. Dichotomizing continuous predictors in multiple regression: a bad idea. Stat Med. 2006;25:127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MJ, Fleming FJ, Gunzler DD, Messing S, Salloum RM, Monson JRT. Laparoscopic appendectomy is safe and efficacious for the elderly: an analysis using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project database. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1802–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee Y, Fleming FJ, Deeb AP, Gunzler D, Messing S, Monson JRT. A laparoscopic approach reduces short-term complications and length of stay following ileocolic resection in Crohn’s disease: an analysis of outcomes from the NSQIP database. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmila MR, Jakubus JL, Maggio PM, et al. Real money: complications and hospital costs in trauma patients. Surgery. 2008;144:307–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Bootstrap assessment of the stability of multivariable models. Stata Journal. 2009;9:547–570. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Multivariable Model-Building: A Pragmatic Approach to Regression Analysis Based on Fractional Polynomials for Modelling Continuous Variables. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renteria O, Shahid Z, Huerta S. Outcomes of appendectomy in elderly veteran patients. Surgery. 2018;164:460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies with Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirshtein B, Perry AH, Mizrahi S, Lantsberg L. Value of laparoscopic appendectomy in the elderly patient. World J Surg. 2009;33:918–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinandt M, Godiris-Petit G, Menegauz F, Chereau N, Lupinacci RM. Appendicitis is a severe disease in elderly patients: a twenty-year audit. JSLS. 2020;24,e2020.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massarweh NN, Legner VJ, Symons RG, McCormick WC, Flum DR. Impact of advancing age on abdominal surgical outcomes. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1108–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masoomi H, Nguyen NT, Dolich MO, Mills S, Carmichael C, Stamos MJ. Laparoscopic appendectomy trends and outcomes in the United States: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2004e2011. Am Surg. 2014;80:1074–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.