Abstract

The temperate phage mv4 integrates its genome into the chromosome of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus by site-specific recombination within the 3′ end of a tRNASer gene. Recombination is catalyzed by the phage-encoded integrase and occurs between the phage attP site and the bacterial attB site. In this study, we show that the mv4 integrase functions in vivo in Escherichia coli and we characterize the bacterial attB site with a site-specific recombination test involving compatible plasmids carrying the recombination sites. The importance of particular nucleotides within the attB sequence was determined by site-directed mutagenesis. The structure of the attB site was found to be simple but rather unusual. A 16-bp DNA fragment was sufficient for function. Unlike most genetic elements that integrate their DNA into tRNA genes, none of the dyad symmetry elements of the tRNASer gene were present within the minimal attB site. No inverted repeats were detected within this site either, in contrast to the lambda site-specific recombination model.

The integrases form a diverse family of recombinases that mediate DNA rearrangements by means of conservative site-specific recombination reactions (1, 3). To date, more than 100 members of the integrase family, including the well-studied lambda integrase protein (14), have been identified. A comparison of their sequences reveals extended areas of similarity and several types of structural difference (10, 17). Integrase-mediated recombination reactions have been studied extensively. Their complexity varies considerably both in their requirement for accessory proteins and in the size of the DNA sites involved (27). To obtain more information about site-specific recombination in gram-positive bacteria, we investigated the site-specific integration system of the bacteriophage mv4. This temperate phage infects the gram-positive bacterium Lactobacillus delbrueckii and during lysogenization, the mv4 integrase catalyzes site-specific recombination between the phage attP site and the bacterial attB site. Recombination occurs within a 17-bp core sequence, common to attP and attB. At the attB site, the core overlaps the 3′ end of a tRNASer gene and the integrity of the tRNA gene is preserved after recombination (9). The integration vector pMC1, which contains the mv4 elements int and attP, integrates into the chromosome in a wide variety of gram-positive bacteria (5). The highly conserved nucleotides of the pMC1 chromosomal insertion sites in these various hosts form a 20-bp consensus sequence and are thought to be essential for attB function. We have shown elsewhere that the attP site has a complex structure with a minimal size of 234 bp (4).

In this study, an attP × attB recombination assay was developed in Escherichia coli to determine the minimal functional size of the attB site and to analyze the nucleotide requirements of this sequence.

The phage mv4 site-specific recombination elements are functional in E. coli.

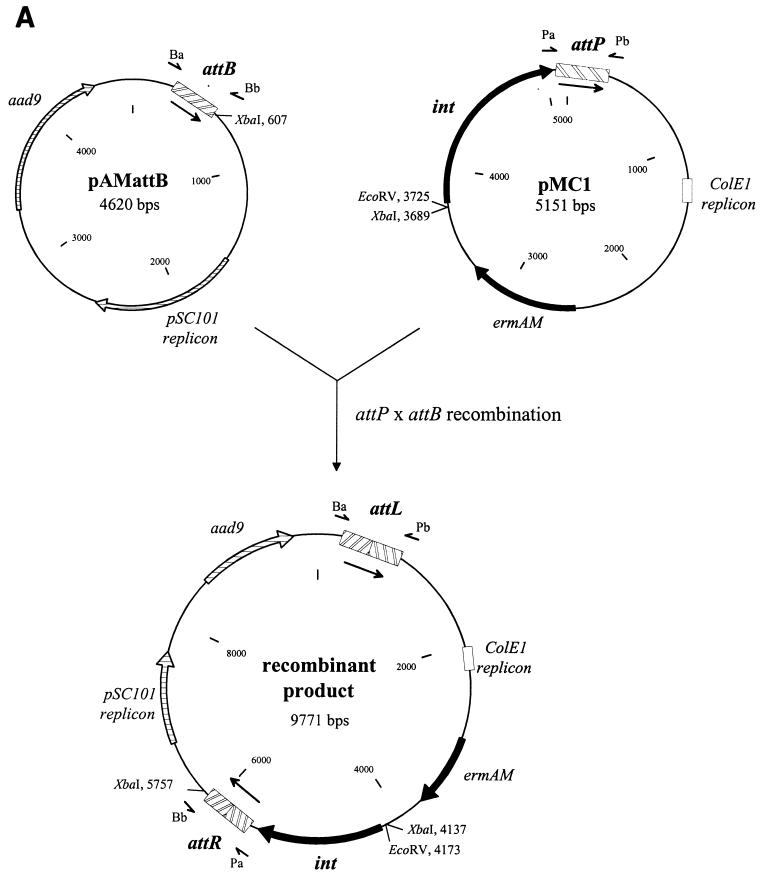

The integrase of phage mv4 promotes recombination in a wide variety of gram-positive bacteria (5). We therefore investigated whether this recombinase was also active in a gram-negative bacterium. A plasmid recombination assay was performed with E. coli (Fig. 1A). The L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus attB site and the mv4 integrative elements int and attP were inserted, respectively, into two compatible plasmids, pAM239 and pRC1 (Table 1), which have no sequences in common. The recombinant plasmids, pAMattB and pMC1 (Table 1; Fig. 1A), were introduced into recombination-deficient E. coli TG2 (Table 1). Cells resistant to erythromycin (100 μg/ml) and spectinomycin (70 μg/ml) were grown for approximately 25 generations. Plasmids were then extracted, subjected to restriction digestion, and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining. Recombination between attP and attB was detected based on the formation of a cointegrate between the two plasmids, pMC1 (5.1 kb) and pAMattB (4.6 kb). In bacteria transformed with these two plasmids, a 9.7-kb DNA molecule was detected with a restriction pattern consistent with the map of the expected cointegrate (Fig. 1A): XbaI digestion generated two fragments of 1.6 and 8.1 kb (Fig. 1B, lane 5), and the cointegrate was linearized by EcoRV digestion (Fig. 2, lane 3). The low-copy-number plasmid pAMattB was not detected in these transformants, whereas the high-copy-number plasmid pMC1 was. This suggests that almost all the pAMattB molecules had recombined with the pMC1 molecules which were in excess. The formation of the cointegrate resulted from Int-mediated recombination because no recombinant product was detected if there was no attB site present in the test (Fig. 1B, lane 6) or if the int gene was defective (Fig. 1B, lane 7). The attL and attR sites were detected in the cointegrate molecule by PCR amplification with the primer sets Ba-Pb for attL and Pa-Bb for attR (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). Amplified products of the expected length (211 and 276 bp, respectively) were obtained. If the template used in the PCR reaction was plasmid DNA from strains containing the defective int gene or lacking the attB site or a mixture of the individually purified plasmids pAMattB and pMC1, no amplification was observed, demonstrating that the amplification of attL and attR was not an artifact of the PCR experiment.

FIG. 1.

attP × attB site-specific recombination test in E. coli. (A) Schematic representation of cointegrate formation between pMC1 and pAMattB. Restriction maps of the plasmids used in the test are shown. Pa and Bb, PCR primers for attR amplification; Ba and Pb, PCR primers for attL amplification. The arrows beside the attachment sites indicate the orientation of the homologous core sequences. (B) Electrophoresis in a 0.5% agarose gel (ethidium bromide stained) of XbaI-digested plasmid DNA isolated from E. coli TG2 transformed with pMC1 (int+ attP) (lane 1), pMC2 (int− attP) (lane 2), pAM239 (lane 3), pAMattB (lane 4), pMC1 and pAMattB (lane 5), pMC1 and pAM239 (lane 6), and pMC2 and pAMattB (lane 7). L, 1-kb DNA ladder (Bethesda Research Laboratories). The photograph is a negative image. Arrows indicate the 1.6- and 8.1-kb XbaI fragments of the cointegrate.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strain, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Material | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strain | ||

| E. coli TG2 | supE hsdΔ5 thi Δ(lac-proAB) Δ(srl recA)306::Tn10 (Tetr) F′ [proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15] | 5 |

| Plasmid | ||

| pRC1 | ermAM+ ori colE1; 3.5 kb | 15 |

| pMC1 | pRC1::1.6-kb EcoRV-PvuII φmv4 int+ attP | 9 |

| pMC2 | pMC1 4-bp deletion; int− derivative | 9 |

| pAM239 | aad9 ori pSC101; 4.3 kb | J. P. Bouché |

| pAMattB | pAM239::L. delbrueckii attB (284 bp); 4.6 kb | 4 |

| pAMattB1 to -10 | pAM239::L. delbrueckii containing resected or mutated attB site | This study |

| Primer | ||

| Ba | 5′-AAGCTTCACCATCTTAAAAAATA-3′ | 9 |

| Bb | 5′-CATTTGATTTAGATGTCCTT-3′ | 9 |

| Pa | 5′-AAGAGTTCTAAATCAACTAG-3′ | This study |

| Pb | 5′-TAAAAACAAAAATAATCCCC-3′ | This study |

FIG. 2.

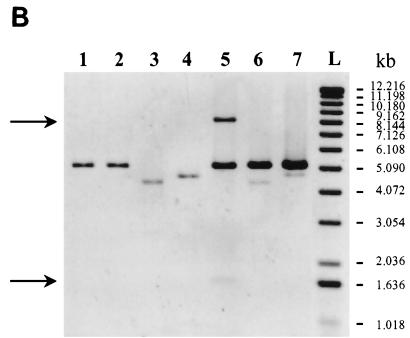

Site-specific recombination in E. coli between the attP site and truncated or mutated attB sites. The attB sequences are presented in Table 2. Electrophoresis in a 0.5% agarose gel (ethidium bromide stained) of EcoRV-digested plasmid DNA isolated from E. coli TG2 transformed with pMC1 (int+ attP) (lane 1), pAM239 (lane 2), pMC1 and pAMattB (lane 3), pMC1 and pAMattB1 (lane 4), pMC1 and pAMattB2 (lane 5), pMC1 and pAMattB3 (lane 6), and pMC1 and pAMattB4 (lane 7) is shown. Plasmids pAM239, pAMattB, and pAMattB1 to -4 have no EcoRV site. Plasmid pMC1 and the cointegrate each contain one EcoRV site. L, 1-kb DNA ladder (Bethesda Research Laboratories). The photograph is a negative image. Arrows indicate the linear cointegrate (a), linear pMC1 (b), open circular form (c), and supercoiled circular form of pAMattB (d).

Determination of the minimal sequence required for attB function.

To determine the minimum functional size of the attB site, synthetic attB sites of various lengths with either cohesive or blunt ends were produced by annealing two complementary oligonucleotides (Eurogentec). The DNA duplexes obtained were then inserted into pAM239 at a unique restriction site (EcoRI, BamHI, SalI, or SmaI). Insertion was checked by restriction digestion and DNA sequencing. The deletion derivatives of the attB site were then tested for their ability to recombine in vivo with the attP site located on plasmid pMC1 (int+ attP) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Similar amounts of recombinant product were obtained with attB sites containing at least those residues between positions −10 and +5 (pAMattB, pAMattB1, and pAMattB2) (Table 2; Fig. 2, lanes 3 to 5). Removal of the nucleotide at position −10 resulted in significantly smaller amounts of cointegrate (pAMattB3) (Table 2; Fig. 2, lane 6) and no cointegrate was detected if further deletions were made, removing the nucleotides at positions −9 or +5 (pAMattB4 and pAMattB5) (Table 2; Fig. 2, lane 7). The minimal attB fragment required for maximal activity was a 16-bp sequence (pAMattB2) (Table 2). This minimal site is included within the consensus sequence deduced from the pMC1 chromosomal insertion sites present in various hosts (5) (Table 2, bottom row) and overlaps the 5′ end of the core.

TABLE 2.

Recombination activities observed with resected and mutated attB sitesa

| Plasmid | attB sequence | Detection of the cointegrate |

|---|---|---|

| −20 −10 0 +10 | ||

| · · · · | ||

| pAMattB | CGCAGGTTCAAATCCTGTACTCTCCTTAATAAGGTCA | ++ |

| → | ||

| pAMattB1 | agtgaaTTCAAATCCTGTACTCTCCTTAATAgaattc | ++ |

| pAMattB2 (minimal attB) | gactctagaggATCCTGTACTCTCCTTggatccccgg | ++ |

| pAMattB3 | cggtacccggggTCCTGTACTCTCCTTcccggggatc | + |

| pAMattB4 | gcctgcaggtcgaCCTGTACTCTCCTTAATAgtcgac | − |

| pAMattB5 | ggtacccggggATCCTGTACTCTCCTgggatcctcta | − |

| pAMattB6 | gactctagaggATCCTGTACTCTCaTTggatccccgg | − |

| pAMattB7 | gactctagaggATCCTGTACTCaCCTTggatccccgg | − |

| pAMattB8 | ggtacccggggATCCcGTACTCTCCTTggatcctcta | − |

| pAMattB9 | ggatcctctagATaCTGTACTCTCCTTctagagtcga | − |

| pAMattB10 | ggtacccggggATCCTGTACTCTCCaTggatcctcta | ++ |

| pMC1 insertion site consensus sequence | rAATCCTGnnnwyTyCnTww | |

| attP sequence | ATGGTTGAAAGAACCTGTACTCTCCTTAATCAAAGCA |

The nucleotide sequences shown in boldface, uppercase letters are the attB sequences inserted into pAM239 (for pAMattB, only part of the sequence is shown). The vector sequences flanking the minimal attB sites are shown in lowercase. The core sequence is boxed. The 3′ end of the tRNASer gene is indicated by the arrow. The center of the core sequence has been defined arbitrarily as position 0. Negative and positive numbers correspond to nucleotide positions on the 5′ and 3′ sides of the core center, respectively. Nucleotides within the 16-bp minimal attB site that were mutated are underlined. The consensus sequence of the pMC1 insertion sites in various bacterial hosts and the sequence of the attP site in the core region are indicated in the last two rows of the table.

Mutational analysis of the minimal attB site.

Conserved nucleotides in the pMC1 insertion sites’ consensus sequence (5) were mutated within the 16-bp minimal attB sequence. In the case of genetic elements carrying sequences homologous to the 3′ ends of genes into which they insert, the Campbell model predicts that the strand exchange reaction occurs in the 5′ portion of the core (7). Concerning the phage mv4, this prediction is consistent with previous results indicating that the first three nucleotides at the 5′ extremity of the core, CCT, are important for the strand exchange reaction (5). Independent changes of two of these three nucleotides, at positions −8 and −6 (pAMattB9 and pAMattB8, respectively) (Table 2), abolished attB activity, confirming the predicted involvement of these nucleotides in attB function. Changes of other conserved nucleotides, at positions +1 and +3 (pAMattB7 and pAMattB6, respectively) (Table 2), also abolished recombination activity. These nucleotides may be involved in the recognition of the attB site by the integrase. In contrast, mutation of a nonconserved nucleotide at position +4 (pAMattB10) (Table 2) did not affect recombination.

Comparison of the mv4 attB site with other well-characterized attB sites.

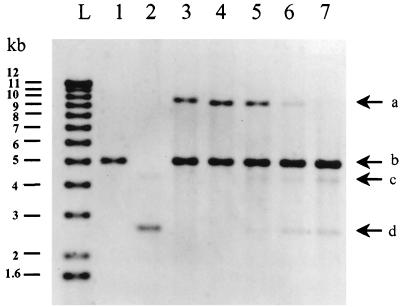

In all integrative recombination systems characterized, the attP and attB target sites differ greatly in length and structure (12–14, 16, 18, 19, 26). The attB site is a short DNA sequence (less than 30 bp) corresponding to the crossover region at which strand exchange takes place (7). Two imperfect inverted repeats that bind to the integrase surround a 7-bp overlap region delimited by the scattered cuts made by the recombinase. The attP site is longer (more than 200 bp) and has a more complex structure. The crossover region of attP is flanked by two arms containing additional integrase-binding sites. A higher-order structure, called the intasome, is formed on attP and is required for synapsis with the naked attB site (23). As in other site-specific integration systems, the mv4 recombination target sites are dissimilar. The attP site consists of a 234-bp DNA fragment containing five scattered putative Int-binding sites (4) whereas the attB site requires only a 16-bp sequence to be functional. The mv4 minimal attB site is the shortest attB sequence described to date. It extends beyond the 5′ boundary of the core (Table 2, top row). This property is shared by four other elements that insert their DNA into a tRNA gene (12, 19, 21, 26) (Fig. 3A). It has been suggested that the frequent use of tRNA genes as insertion sites is due to the presence of dyad symmetry elements and that mobile genetic elements may use the symmetry of the anticodon stem-loop structure to form the appropriately spaced inverted integrase binding sites in attB (7, 13, 22). In phages HP1 (13), P22 (26), and L5 (19), the core sequence includes the anticodon loop sequence, which coincides with the overlap region, and this is also presumably the case for the pSAM2 integrative element (21) (Fig. 3A). This model does not apply to phage mv4 and several other elements (2, 6, 11, 20, 22, 25, 28) because the core sequence does not overlap either the anticodon loop or the TΨC loop (Fig. 3B). For these elements, it is unclear why the integration target is a tRNA gene.

FIG. 3.

DNA sequences of tRNA genes used as insertion sites by genetic elements. (A) Insertion sites for which the core sequence overlaps the anticodon loop sequence. The names of the genetic elements and tRNA genes into which they integrate are indicated on the left. The tRNA sequences and their 3′ flanking regions are shown in uppercase and lowercase letters, respectively. The core sequences are boxed and the boundaries of the minimal sequences required for attB function are indicated by brackets. The overlap regions, when determined experimentally, are shown in boldface type. (B) Insertion sites for which the core sequence is located downstream from the anticodon loop sequence.

Another intriguing aspect of the mv4 attB site is the absence of obvious inverted repeats. The same observation was made for the attP site. No inverted repeats were detected either inside or close to the core region of the mv4 attP site. These findings suggest that the mv4 integrase core-binding sites may correspond to divergent sequences recognized differently by the recombinase. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that the lambda core-binding sites have similar but nonidentical sequences and have different affinities for λInt (24) and that integrases do not recognize each set of the core sites in the same way (8).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the mv4 integration region has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. U15564.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues in the laboratory (M. Lautier, P. Le Bourgeois, M. L. Daveran-Mingot, and N. Campo) for advice and helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by grants from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (UPR 9007), from the Biotech program (BIO2-CT94-3055), and from the Région Midi-Pyrénées (RECH/9507854).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abremski K, Hoess R. Evidence for a second conserved arginine residue in the integrase family of recombination proteins. Protein Eng. 1992;5:87–91. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez M A, Herrero M, Suarez J E. The site-specific recombination system of the Lactobacillus species bacteriophage A2 integrates in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Virology. 1998;250:185–193. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argos P, Landy A, Abremski K, Egan J B, Haggard-Ljungquist E, Hess R H, Kahn M L, Kalionis B, Narayana S V L, Pierson III L S, Sternberg N, Leong J M. The integrase family of site-specific recombinases: regional similarities and global diversity. EMBO J. 1986;5:433–440. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auvray F, Coddeville M, Espagno G, Ritzenthaler P. Integrative recombination of Lactobacillus delbrueckii bacteriophage mv4: functional analysis of the reaction and structure of the attP site. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;262:355–366. doi: 10.1007/s004380051094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auvray F, Coddeville M, Ritzenthaler P, Dupont L. Plasmid integration in a wide range of bacteria mediated by the integrase of Lactobacillus delbrueckii bacteriophage mv4. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1837–1845. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1837-1845.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruttin A, Foley S, Brüssow H. The site-specific integration system of the temperate Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophage phiSfi21. Virology. 1997;237:148–158. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell A. Chromosomal insertion sites for phages and plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7495–7499. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7495-7499.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorgai L, Sloan S, Weisberg R A. Recognition of core binding sites by bacteriophage integrases. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:1059–1070. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupont L, Boizet-Bonhoure B, Coddeville M, Auvray F, Ritzenthaler P. Characterization of genetic elements required for site-specific integration of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus bacteriophage mv4 and construction of an integration-proficient vector for Lactobacillus plantarum. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:586–595. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.586-595.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito D, Scocca J. The integrase family of tyrosine recombinases: evolution of a conserved active site domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3605–3614. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.18.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gindreau E, Torlois S, Lonvaud-Funel A. Identification and sequence analysis of the region encoding the site-specific integration system from Leuconostoc oenos (Oenococcus oeni) temperate bacteriophage phi10MC. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;147:279–285. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(96)00540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauser M, Scocca J. Site-specific integration of the Haemophilus influenzae bacteriophage HP1. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6859–6864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser M, Scocca J. Site-specific integration of the Haemophilus influenzae bacteriophage HP1: location of the boundaries of the phage attachment site. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6674–6677. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6674-6677.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landy A. Dynamic, structural, and regulatory aspects of lambda site-specific recombination. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:913–949. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.004405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Bourgeois P, Lautier M, Mata M, Ritzenthaler P. New tools for the physical and genetic mapping of Lactococcus strains. Gene. 1992;111:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee C Y, Buranen S L. Extent of the DNA sequence required in integration of staphylococcal bacteriophage L54a. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1652–1657. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1652-1657.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nunes-Düby S E, Kwon H J, Tirumalai R S, Ellenberg T, Landy A. Similarities and differences among 105 members of the Int family of site-specific recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:391–406. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peña C E A, Lee M H, Pedulla M L, Hatfull G F. Characterization of the mycobacteriophage L5 attachment site, attP. J Mol Biol. 1997;266:76–92. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peña C E A, Stoner J E, Hatfull G F. Positions of strand exchange in mycobacteriophage L5 integration and characterization of the attB site. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5533–5536. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5533-5536.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierson L S, III, Kahn M L. Integration of satellite bacteriophage P4 in Escherichia coli. DNA sequences of the phage and host regions involved in site-specific recombination. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:487–496. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raynal A, Tuphile K, Gerbaud C, Luther T, Guérineau M, Pernodet J L. Structure of the chromosomal insertion site for pSAM2: functional analysis in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:333–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiter W D, Palm P, Yeats S. Transfer RNA genes frequently serve as integration sites for prokaryotic genetic elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:1907–1914. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.5.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richet E, Abcarian P, Nash H. Synapsis of attachment sites during lambda integrative recombination involves capture of a naked DNA by a protein-DNA complex. Cell. 1988;52:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90526-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross W, Landy A. Patterns of lambda Int recognition in the regions of strand exchange. Cell. 1983;33:261–272. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90355-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shoemaker N B, Wang G-R, Salyers A A. The Bacteroides mobilizable insertion element, NBU1, integrates into the 3′ end of a leu-tRNA gene and has an integrase that is a member of the lambda integrase family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3594–3600. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3594-3600.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith-Mungo L, Chan I T, Landy A. Structure of the P22 att site. Conservation and divergence in the lambda motif of recombinogenic complexes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20798–20805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stark W M, Boocock M R, Sherratt D J. Catalysis by site-specific recombinases. Trends Genet. 1992;8:432–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun J, Inouye M, Inouye S. Association of a retroelement with a P4-like cryptic prophage (retronphage phiR73) integrated into the selenocystyl tRNA gene of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4171–4181. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4171-4181.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]