Abstract

The adhE gene of Escherichia coli encodes a multifunctional ethanol oxidoreductase whose expression is 10-fold higher under anaerobic than aerobic conditions. Transcription of the gene is under the negative control of the Cra (catabolite repressor-activator) protein, whereas translation of the adhE mRNA requires processing by RNase III. In this report, we show that the expression of adhE also depends on the Fis (factor for inversion stimulation) protein. A strain bearing a fis::kan null allele failed to grow anaerobically on glucose solely because of inadequate adhE transcription. However, fis expression itself is not under redox control. Sequence inspection of the adhE promoter revealed three potential Fis binding sites. Electrophoretic mobility shift analysis, using purified Fis protein and adhE promoter DNA, showed three different complexes.

During anaerobic sugar utilization, Escherichia coli carries out mixed-acid fermentation (33). The products include ethanol (7, 33), which is formed from acetyl coenzyme A by two consecutive NADH-dependent reductions. These are catalyzed by the adhE-encoded multifunctional protein which is also a deactivase of pyruvate formate-lyase (9, 13, 16, 20, 29, 30). The adhE gene is under complex transcriptional, as well as translational, control. The anaerobic expressions of adhE-lacZ fusions are about 10-fold higher than the aerobic expressions (5, 19). It has been suggested that the gene expression responds to a signal such as the NAD/NADH ratio (5, 19, 23). Recently, the cra (catabolite repressor-activator at min 2) gene product, a global transcription regulator of carbon flow (29), was found to repress adhE expression in the absence of the effector (24). In addition, translation of the adhE mRNA depends on cleavage by RNase III, for an unknown physiological reason (1). Here we report another global regulator that controls adhE transcription.

Fis is essential for anaerobic expression of adhE.

In a search for trans-acting regulators responsible for the redox control of adhE expression, we found by chance that strain ECL4001 (Table 1), bearing a fis::kan mutation (min 73.4), lost the ability to grow anaerobically on glucose but not on glucuronate, a phenotype expected of adhE-defective mutants (6). Fis (factor for inversion stimulation) is known to play a global role in gene expression (11, 15, 17). Mutations in adhR (min 72) were also reported to prevent adhE expression (6). However, the DNA sequence of fis in an adhR mutant allele was found to be normal (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and phages used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or phage | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| ECL3999 | MC4100 but adhE::kan | This study |

| ECL4000 | MC4100 Φ(adhE-lacZ) adhE+ | λADH13 × MC4100 |

| ECL4001 | ECL4000 but fis::kan | P1(RJ708) × ECL4000 |

| ECL4002 | ECL4000 but adhE::kan | P1(ECL3999) × MC4100 |

| ECL4003 | ECL4000 but cra::Tn10 | P1(LJ2805) × ECL4000 |

| ECL4004 | ECL4000 but cra::Tn10 fis::kan | P1(LJ2805) × ECL4001 |

| ECL4008 | JC7623 adhE::kan | This study |

| ECL4009 | ECL4000/pADH11 | This study |

| ECL4010 | ECL4001/pADH11 | This study |

| JC7623 | recB21 recC22 sbcB15 sbcC201 | 18 |

| LJ2805 | cra::Tn10 Δ(codB-lac)3 xylA7 Δcya854 glp-8306 | 8 |

| MC4100 | F−araD139 ΔlacU169 rpsL150 relA1 flb-5301 deoC1 ptsF25 | 5 |

| RJ1835 | Φ(fis-lacZ)fis+ operon fusion | Reid Johnson |

| RJ1839 | Φ(fis-lacZ)fis+ protein fusion | Reid Johnson |

| RJ708 | fis::kan | Reid Johnson |

| Plasmids | ||

| pADH11 | Apr ptrc adhE+ | This study |

| pRS415 | AprlacZYA+ | 32 |

| pOK1 | adhE::kan Apr | This study |

| pSE280 | Apr ptrc | Invitrogen |

| Phages | ||

| λRS45 | lacZ′ lacYA+ bla′ | 32 |

| λADHOK1 | Φ(adhE-lacZ)lacYA+ bla′ | This study |

A comparison of the activity levels of ethanol oxidoreductase and β-galactosidase in strain ECL4000 [adhE+ Φ(adhE-lacZ) fis+] and its isogenic derivative ECL4001 [adhE+ Φ(adhE-lacZ) fis::kan] showed that anaerobic growth failed to raise the activity levels of both enzymes in the fis::kan mutant (Table 2). It therefore appears that Fis is required for the anaerobic response of adhE expression.

TABLE 2.

Aerobic and anaerobic expression of adhE in cells grown in LB mediuma

| Strain | Genotype | Relative activity (%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol dehydrogenaseb

|

β-Galactosidasec

|

||||||

| −O2 | +O2 | −O2/+O2 ratio | −O2 | +O2 | −O2/+O2 ratio | ||

| ECL4000 | adhE+ fis+ | 100 | 11 | 9.1 | 100 | 9.7 | 10 |

| ECL4001 | adhE+ fis::kan | 14 | 11 | 1.3 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 1.0 |

LB medium contained 0.1 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) at pH 7.4. Incubation of aerobic and anaerobic cultures and preparation of cell extracts were carried out as described previously (23). Potassium phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 8.2) was used for suspension of the cells.

Ethanol dehydrogenase activity was assayed by spectrophotometrically determining the rate of NADH formation at 340 nm. A value of 100% represent 324 ± 36 nmol/min/mg of protein. The assay mixture (1 ml) comprised 1.6 M ethanol, 0.3 M potassium carbonate (pH 10.0), and 0.66 mM NAD (24). All of the values given are averages of three experiments.

β-Galactosidase activity was assayed as described by Miller (25). A value of 100% represent 9,200 ± 330 U. Each culture was assayed in triplicate; typically, these values gave a coefficient of variation (mean divided by the standard deviation) of <5%. All results were confirmed in at least three independent cultures. Averages of three experiments are shown.

Fis dependence of adhE expression in the presence or absence of Cra.

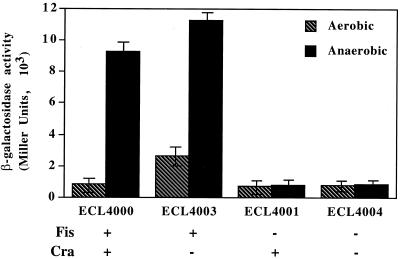

In view of the repression of adhE expression by Cra (24), it is possible that in the absence of this global regulator, Fis is no longer required for adhE transcription. We therefore introduced a cra::Tn10 allele into strains ECL4000 and ECL4001. The resulting strains, ECL4003 [λatt::Φ(adhE-lacZ) fis+ cra::Tn10] and ECL4004 [λatt::Φ(adhE-lacZ) cra::Tn10 fis::kan], were grown aerobically or anaerobically, and their levels of β-galactosidase activity were assayed. In agreement with a previous study (24), expression of Φ(adhE-lacZ) in strain ECL4003 lacking Cra was elevated 2 to 3-fold aerobically and 1.5-fold anaerobically (Fig. 1). The double mutant ECL4004, lacking both Cra and Fis, expressed Φ(adhE-lacZ) at very low levels either aerobically or anaerobically. Thus, Fis is required for adhE expression independently of Cra.

FIG. 1.

β-Galactosidase activity levels of aerobically or anaerobically grown cells of different merodiploid strains [adhE+ Φ(adhE-lacZ)]. Strains ECL4000 (fis+ cra+), ECL4003 (fis+ cra::Tn10), ECL4001 (fis::kan cra+), and ECL4004 (fis::kan cra::Tn10) were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing glucose. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed in exponentially growing cultures as described before (25). Bars indicate the standard deviation of four independent experiments.

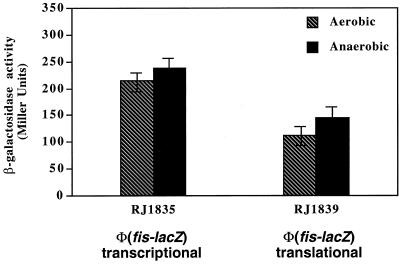

Expression of Φ(fis-lacZ) transcriptional and translational fusions under aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

The cellular levels of Fis are known to vary greatly with growth phase and environmental conditions (3). However, it is not known whether the level of Fis depends on the cellular redox state and whether the low aerobic expression of adhE is due to Fis limitation. To address these questions, we analyzed strains RJ1835 and RJ1839 bearing, respectively, a transcriptional and a translational Φ(fis-lacZ) fusion (3). The expressions of both fusions were similar in aerobically and anaerobically grown cells (Fig. 2). These results suggest that an element(s) other than Fis is responsible for the redox control of adhE expression.

FIG. 2.

Aerobic and anaerobic expression of a Φ(fis-lacZ) fusion. Strains RJ1835 [Φ(fis-lacZ) operon fusion] and RJ1839 [Φ(fis-lacZ) protein fusion] were grown aerobically or anaerobically at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing glucose. Cell samples were taken at exponential growth phase, and β-galactosidase activity was determined. Bars indicate the standard deviation of four different experiments.

Expression of adhE under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter.

To test whether Fis specifically acts on the adhE promoter, we cloned the adhE gene into plasmid pSE280 (Invitrogen) under the control of the trc promoter (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG] inducible). When this plasmid (pADH11) was transformed into strain ECL4001 (fis::kan), normal anaerobic growth on glucose occurred only in the presence of IPTG (200 μM). When assayed for ethanol oxidoreductase activity, anaerobically grown cells showed fourfold induction of AdhE (Table 2). Thus, the growth failure of strain ECL4001 (fis::kan) solely reflects inadequate AdhE activity.

Physical evidence of interaction of Fis with the adhE promoter.

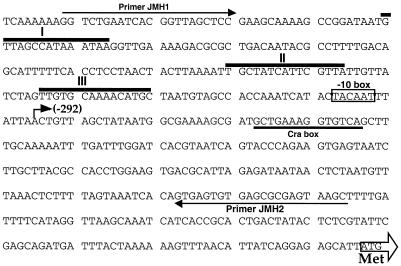

The adhE promoter region (Fig. 3) contains three perfect matches to the Fis consensus sequence (35), resembling other promoters known to be under Fis control (27, 28). When a 388-bp DNA fragment (extending from position −198 to position +172) was used in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay, the presence of Fis retarded the migration of the DNA (Fig. 4). The first detectable complex was formed at a Fis concentration that is expected for an apparent Kd of 3 × 10−9, which is typical of other established Fis regulatory binding sites (35). As the Fis concentration was increased, two additional complexes with lower migration rates were formed. Such a phenomenon was also previously observed, but its physiological significance is unknown (34, 35).

FIG. 3.

The promoter region of adhE. The locations of the transcriptional start sites are shown in parentheses (24). Putative Fis consensus sequences I, II, and III are indicated by thick lines above the sequences. Primers JMH1 and JMH2 (used for Fig. 4) are denoted by arrows. The proposed Cra binding box is underlined, and the putative −10 box is shown by a square. The translational start site of adhE is indicated by an open arrow.

FIG. 4.

Electrophoretic mobility shift of adhE promoter DNA by Fis. The 388-bp fragment containing the adhE promoter region (from position −198 to position +172; Fig. 3) was 32P end labeled. The DNA fragment was gel purified and then incubated with various amounts of Fis protein (a generous gift from Reid Johnson) in a 20-μl reaction mixture consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 80 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 2 μg of sonicated herring sperm DNA per ml. The binding reaction was performed at 37°C for 30 min. At the end of the incubation, 5 μl of gel loading buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM EDTA, 80 mM NaCl, 100 μg of sonicated herring sperm DNA per ml, 7.5% Ficoll, 0.1% bromophenol blue) was added to each mixture. Samples of 20 μl were then subjected to electrophoresis in a 1× Tris-borate-EDTA–5% polyacrylamide gel (21, 35). Free DNA and Fis-bound DNA complexes after autoradiography are indicated. Lanes 1 through 4 contained reaction mixtures containing, respectively, 0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 ng of Fis.

Role of Fis in adhE gene expression.

Fis is known to be implicated in many different cellular processes (2, 3, 10, 12, 26, 31; for a review, see reference 11), among which is the regulation of gene expression. It is possible that Fis facilitates adhE expression by directly interacting with the RNA polymerase, as previously shown for other Fis-dependent promoters (4, 14). Alternatively, Fis may act directly on the promoter DNA of adhE, thereby stabilizing an open complex. Such a mechanism is consistent with our observation that novobiocin, a specific gyrase inhibitor, lowered the anaerobic expression of adhE by about 75% at a concentration of 20 μg/ml without appreciable growth inhibition (data not shown). In any event, it is a mystery why Fis was recruited evolutionarily for adhE expression, since the level of the pleiotropic regulatory protein does not seem to vary with respiratory growth conditions. The activity of Fis as a regulatory element has generally been associated with additional regulatory proteins (11, 22), but in the case of adhE expression, Cra is not the likely partner of Fis.

This is the first report of a gene with an anaerobic function under Fis control. We have recently isolated suppressor mutants of strains bearing a fis::kan mutation that regained the ability to grow anaerobically on glucose as the sole carbon and energy source. Characterization of these mutants may help to discover the specific element that actually is responsible for the redox regulation of adhE.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants GM40993 and GM39693. P.D.W. is a postdoctoral D. Collen Fellow of the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

We thank Reid Johnson for the generous gift of purified Fis protein and fis fusion and mutant strains and Roberto Kolter for useful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aristarkhov A, Mikulskis A, Belasco J G, Lin E C C. Translation of the adhE transcript to produce ethanol dehydrogenase requires RNase III cleavage in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4327–4332. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4327-4332.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balke V L, Gralla J D. Changes in the linking number of supercoiled DNA accompany growth transitions in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4499–4506. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.10.4499-4506.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball C A, Osuna R, Ferguson K C, Johnson R C. Dramatic changes in Fis levels upon nutrient upshift in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8043–8056. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8043-8056.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bokal A J, IV, Ross W, Gaal T, Johnson R C. Molecular anatomy of a transcription activation patch: Fis-RNA polymerase interactions at the Escherichia coli rrnB P1 promoter. EMBO J. 1995;16:154–162. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y-M, Lin E C C. Regulation of the adhE gene, which encodes ethanol dehydrogenase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:8009–8013. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.8009-8013.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark D P, Cronan J E. Escherichia coli mutants with altered control of alcohol dehydrogenase and nitrate reductase. J Bacteriol. 1980;141:177–183. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.1.177-183.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark D P. The fermentation pathways of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;63:223–234. doi: 10.1016/0168-6445(89)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crasnier-Mednansky M, Park M C, Studley W K, Saier M H., Jr Cra-mediated regulation of Escherichia coli adenylate cyclase. Microbiology. 1997;143:785–792. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham P R, Clark D P. The use of suicide substrates to select mutants of Escherichia coli lacking enzymes of alcohol fermentation. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;205:487–493. doi: 10.1007/BF00338087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drlica K. Control of bacterial DNA supercoiling. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkel S E, Johnson R C. The Fis protein: it’s not just for DNA inversion anymore. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3257–3265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.González-Gil G, Bringmann P, Kahmann R. Fis is a regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:21–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodlove P E, Cunningham P R, Parker J, Clark D P. Cloning and sequence analysis of the fermentative alcohol dehydrogenase-encoding gene of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1989;85:209–214. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gosink K K, Gaal T, Bokal IV A J, Gourse R L. A positive control mutant of the transcription activator protein Fis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5182–5187. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5182-5187.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson R C, Bruist M F, Simon M I. Host protein requirements for in vitro site-specific DNA inversion. Cell. 1986;46:531–539. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90878-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler D, Leibrecht I, Knappe J. Pyruvate formate-lyase deactivase and acetyl-CoA reductase activities of Escherichia coli reside on a polymeric protein particle encoded by adhE. FEBS Lett. 1991;281:59–63. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80358-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch C, Ninnemann O, Fuss H, Kahmann R. Purification and properties of the Escherichia coli host factor required for inversion of the G segment in bacteriophage Mu. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15673–15678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kushner S R, Nagaishi H, Templin A, Clark A J. Genetic recombination in Escherichia coli: the role of exonuclease I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:824–827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonardo M R, Cunningham P R, Clark D P. Anaerobic regulation of the adhE gene encoding the fermentative alcohol dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:870–878. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.870-878.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorowitz W, Clark D P. Escherichia coli mutants with a temperature-sensitive alcohol dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:935–938. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.2.935-938.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch A S, Lin E C C. Transcriptional control mediated by the ArcA two-component response regulator protein of Escherichia coli: characterization of DNA binding at target promoters. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6238–6249. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6238-6249.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin R G, Rosner J L. Fis, an accessorial factor for transcriptional activation of the mar (multiple antibiotic resistance) promoter of Escherichia coli in the presence of the activator MarA, SoxS, or Rob. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7410–7419. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7410-7419.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McPhedran P, Sommer B, Lin E C C. Control of ethanol dehydrogenase levels in Aerobacter aerogenes. J Bacteriol. 1961;81:852–857. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.6.852-857.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikulskis A, Aristarkhov A, Lin E C C. Regulation of expression of the ethanol dehydrogenase gene (adhE) in Escherichia coli by the catabolite repressor activator protein Cra. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7129–7134. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7129-7134.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muskhelishvili G, Buckle M, Heumann H, Kahmann R, Travers A A. Fis activates sequential steps during transcription initiation at a stable RNA promoter. EMBO J. 1997;16:3655–3665. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsson L, Vanet A, Vijgenboom E, Bosch L. The role of Fis in trans activation of stable RNA operons of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1990;9:727–734. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross W, Thompson J F, Newlands J T, Gourse R L. Escherichia coli Fis protein activates ribosomal RNA transcription in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J. 1990;9:3733–3742. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saier M H, Jr, Ramseier T M. The catabolite repressor/activator (Cra) protein of enteric bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3411–3417. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3411-3417.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitt B. Aldehyde dehydrogenase activity of a complex particle from Escherichia coli. Biochimie. 1975;57:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(75)80355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider R, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. Fis modulates growth phase-dependent topological transitions of DNA in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:519–530. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5951971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood W A. Fermentation of carbohydrates and related compounds. In: Gunsalus I C, Stainer R Y, editors. The bacteria. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1961. p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu J, Johnson R C. Identification of genes negatively regulated by Fis: Fis and RpoS comodulate growth-phase-dependent gene expression in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:938–947. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.938-947.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, Johnson R C. aldB, an RpoS-dependent gene in Escherichia coli encoding an aldehyde dehydrogenase that is repressed by Fis and activated by Crp. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3166–3175. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3166-3175.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]