Abstract

Objective

A patient with a ruptured distal medial lenticulostriate artery (mLSA) aneurysm presenting with intraventricular hemorrhage was successfully treated using endovascular treatment.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old woman presented with impaired consciousness. Radiological examination revealed intraventricular hemorrhage caused by a rupture of a distal mLSA aneurysm. Using endovascular technique, approaching contralaterally through the anterior communicating artery (AComA), complete occlusion of the aneurysm was achieved by N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) injection. The postoperative course was uneventful.

Conclusion

Intraventricular aneurysms at a distal site of the perforating arteries are rare. Although there have been reports on patients with distal mLSA aneurysms treated by open surgery or conservative therapy, endovascular therapy should also be considered as a treatment option.

Keywords: intraventricular hemorrhage, intraventricular aneurysm, medial lenticulostriate artery, endovascular therapy, N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate

Introduction

Distal perforating artery aneurysms are rare and sometimes exhibit “pure” primary intraventricular hemorrhage (PIVH) not accompanied by intracerebral hemorrhage or subarachnoid hemorrhage.1)

We report a patient with a distal medial lenticulostriate artery (mLSA) aneurysm who presented with intraventricular hemorrhage and was successfully treated by embolization with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA).

Case Presentation

Patient: A 60-year-old female

Chief complaint: Impaired consciousness

Past medical history: She had a history of atrial fibrillation and dilated cardiomyopathy, and was receiving oral warfarin after implantation of a biventricular pacing implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

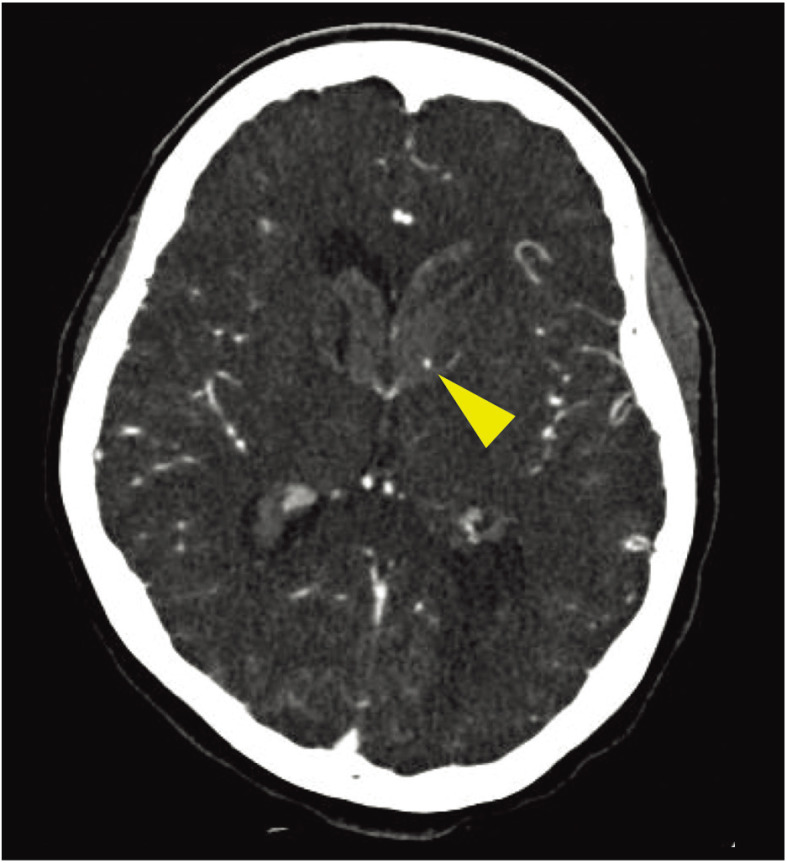

History of present illness: She was found lying at home with her family and transported to our hospital by ambulance. When she arrived at the hospital, the Japan Coma Scale (JCS) score was II-10 and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 14 (E3V5M6), and no clear neurological deficits were observed. Non-contrast head CT revealed hemorrhage in the third and fourth ventricles, and bilateral lateral ventricles with left dominance (Fig. 1). Hemorrhage was confined within the ventricles. To find the source of bleeding, brain 3D-CTA was performed. In the arterial phase, the source of bleeding was unclear. In the venous phase, there was spot enhancement on the lateral wall of the anterior horn of the left lateral ventricle, suggesting the source of bleeding (Fig. 2). After admission, as there was no progression of impaired consciousness, ventricular drainage was not performed and blood pressure control was initiated in the intensive care unit.

Fig. 1. Plain head CT images at onset. There are high-density hematomas in the bilateral lateral ventricles with left dominance. Hematomas are also present in the third and fourth ventricles, and mild ventricular dilatation can be observed.

Fig. 2. Cerebral 3D-CTA source image. A lump of contrast is observed as spot enhancement in the anterior horn of the left lateral ventricle (arrowhead).

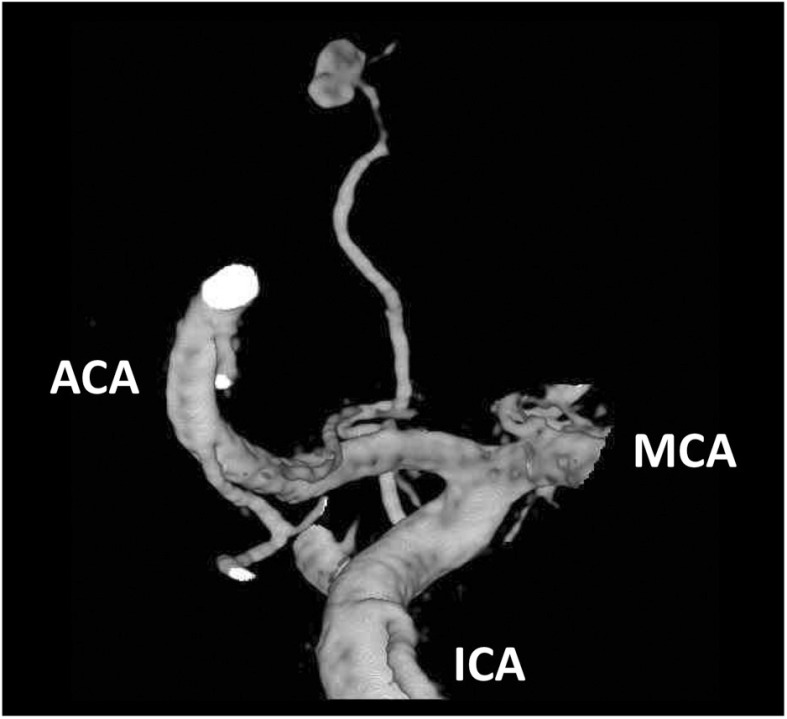

On the third day of admission, cerebral angiograph revealed an aneurysm (3.8 mm in size) at the distal site of the mLSA arising from the proximal A1 segment of the left anterior cerebral artery (ACA), and was considered to be a ruptured aneurysm (Figs. 3 and 4). To prevent re-bleeding, aneurysm embolization was performed.

Fig. 3. Cerebral angiograms of the left internal carotid artery (a, frontal image; b, lateral image). A saccular aneurysm is observed adjacent to the lateral ventricle (arrowheads).

Fig. 4. 3D rotation angiography of the left internal carotid artery. An aneurysm (3.8 mm in size) is present at a distal site of the mLSA arising from the A1 segment of the left ACA. ACA: anterior cerebral artery; ICA: internal carotid artery; MCA: middle cerebral artery; mLSA: medial lenticulostriate artery.

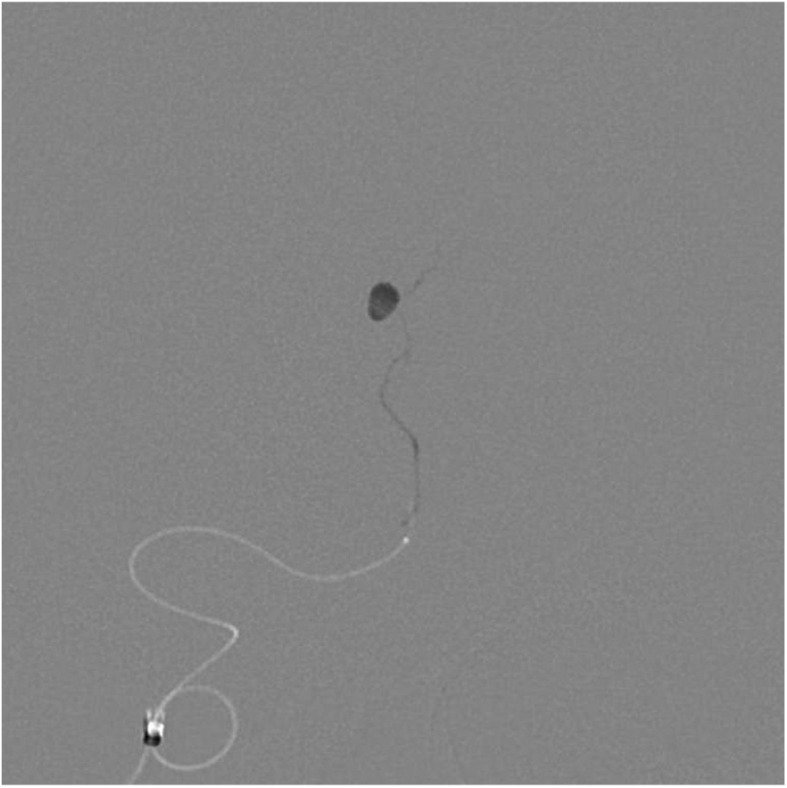

Endovascular treatment: Under general anesthesia, the right femoral introducer was replaced by a 4Fr 80-cm ASAHI FUBUKI Dilator Kit (Asahi Intecc, Aichi, Japan). After systemic heparinization, a guiding sheath was navigated into the petrous portion of the left internal carotid artery. A 4.2Fr ASAHI FUBUKI (Asahi Intecc) was used as a distal access catheter. Using a Mirage (Medtronic Irvine, CA, USA) guide wire, a Marathon (Medtronic) catheter was advanced to the left A1. However, due to the mLSA arising in a direction reverse to the path of the left A1, catheterization was difficult. Compression study of the right common carotid artery confirmed the anterior communicating artery (AComA), and a contralateral approach was attempted. The guiding sheath was introduced into the petrous portion of the right internal carotid artery, and the Marathon was advanced through the AComA into the mLSA origin, but was unable to be advanced to a site near the aneurysm. After changing to a combination of a DeFrictor nano catheter (Medico’s Hirata, Osaka, Japan) and TENROU S10 (Kaneka Medix, Osaka, Japan) guide wire, mLSA cannulation was possible. Selective angiography from the DeFrictor confirmed the location of the catheter tip proximal to the aneurysm, and a 33% NBCA-Lipiodol mixture was slowly injected from the DeFrictor. After the perforating artery distal and proximal to the aneurysm were confirmed to be filled with NBCA, the DeFrictor was removed (Fig. 5). Angiography after NBCA injection demonstrated disappearance of the aneurysm.

Fig. 5. Imaging after NBCA injection. The inside of the aneurysm was filled with NBCA, showing complete embolization. Slight reflux of NBCA was observed in the proximal artery. NBCA: N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate.

Course: There were no signs of hemorrhagic complications or cerebral infarction on the postoperative head CT. Neither impaired consciousness nor paralysis developed. Lipiodol remained as a high-density spot on the lateral ventricular wall of the anterior horn of the left lateral ventricle. Subsequently, sepsis triggered by pneumonia developed and a decrease in muscle strength associated with disuse remained. However, after 6-month rehabilitation, she was discharged to home with a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) of 1.

Discussion

The majority of intraventricular hemorrhage is secondary to intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage. PIVH accounts for 2%–3.3% of all intracranial hemorrhage.2–4) The causes of PIVH include hypertension, arteriovenous malformation (AVM), aneurysms, trauma, Moyamoya disease, cavernous malformation, and coagulation abnormalities.5,6) Intraventricular aneurysms can also cause PIVH.1,2,5,6) Intraventricular aneurysms occurring at the distal site of the perforating arteries are rare, and there has been no established consensus on their natural history or treatment principles.

The present case had an intraventricular aneurysm developing at a distal site of the mLSA arising from the A1 segment of the ACA. Spot enhancement inside of an intracerebral hematoma (or “spot sign”) is a sign of intracerebral hemorrhage indicating extravasation of the contrast medium into the hematoma, and is a risk factor for an enlargement of the hematoma. The “spot sign” reflects bleeding in the cerebral parenchyma, and whether it indicates primary or secondary vascular injury is unknown, and whether or not related to aneurysms is also unclear.7) In intraventricular hemorrhage, unlike intracerebral hemorrhage, there is no brain parenchyma or vascular structures that can be secondarily injured around the hematoma. The bleeding is considered to be due to primary vascular injury, and secondary injuries of the blood vessels are unlikely. Therefore, when spot enhancement is observed on the lateral side of PIVH, a distal perforating artery aneurysm should be considered, although differentiation between a true aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm is difficult. This case was a case of PIVH not accompanied by cerebral parenchymal hemorrhage. Considering the possibility of an intraventricular aneurysm based on a previous study,8) cerebral angiography was performed, which led to the diagnosis. When similar enhancement is observed within the hematoma of PIVH, cerebral angiography should be considered.

To our knowledge, seven patients with distal mLSA aneurysms, including the present patient, have been reported (Table 1).8–13) Their ages varied from 5 to 81 years. Of the seven patients, five presented with PIVH, and most of them had idiopathic aneurysms without underlying disease. In patients on whom pathological examination was performed, a true aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm were observed in one each. Conservative treatment was performed for three patients and radical treatment by direct surgery for three patients. In the three patients who underwent conservative treatment, the duration from onset to treatment varied from 3 days to around 1 month. All reported patients had favorable outcomes, and the present patient was the first to undergo endovascular treatment. In this patient, no pathological diagnosis was made due to the endovascular treatment. Whether the aneurysm is a true aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm is difficult to determine only by morphological evaluation on angiography.

Table 1. Previous reports on distal mLSA aneurysms.

| Author, year | Age/sex | Location | Associateddiseases | Treatment | Pathology | GOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hagihara et al., 2006 | 55/F | Caudate nucleus Intraventricular | None | Craniotomy | Not performed | GR |

| Matushita et al., 2007 | 5/M | Intraventricular | None | Craniotomy | True aneurysm | GR |

| Ellis et al., 2011 | 71/F | Intraventricular | FD | Conservation | Not performed | GR |

| Kim et al., 2013 | 28/M | Intraventricular | None | Craniotomy | Pseudo aneurysm | GR |

| Srivastava et al., 2013 | 45/F | Intraventricular | None | Conservation | Not performed | GR |

| Nomura et al., 2018 | 81/F | Caudate nucleus Intraventricular | None | Conservation | Not performed | GR |

| Present case | 60/F | Intraventricular | None | Endovasculartherapy | Not performed | GR |

FD: fibromuscular dysplasia; GOS: Glasgow outcome scale; GR: good recovery; mLSA: medial lenticulostriate artery

Intraventricular aneurysms are treated by conservative treatment, direct surgery, or endovascular treatment. Conservative treatment for cerebral aneurysms is performed when their spontaneous regression is expected. Previous reports described some patients with distal perforating artery aneurysms associated with Moyamoya disease in whom spontaneous aneurysm regression was observed on cerebral angiograms.14,15) Radical surgery indicated only for patients not exhibiting spontaneous regression was also reported. However, there have been no reported patients with AVM-associated or idiopathic aneurysms who exhibited spontaneous regression. In such patients, treatment to prevent re-rupture may be necessary. Some AVM-associated or idiopathic aneurysms were reported to be true aneurysms.16,17) Thus, regarding pathology, there is not only pseudoaneurysm formation accompanied by hemorrhage but also intracerebral hemorrhage associated with rupture of a cerebral aneurysm that had been present before the onset. In addition, although spontaneous regression of cerebral aneurysms is considered to occur due to spontaneous thrombosis in the aneurysm, aneurysm regression on angiography can also be transient and does not always mean re-rupture was prevented.18) Pathological evaluation of distal mLSA aneurysms in previous studies was insufficient; however, six (85%) of the seven reported patients had idiopathic intraventricular aneurysms. The prognosis of intraventricular aneurysms after re-rupture may be markedly poor, and early radical surgery can be a treatment option.

In direct surgery, the ventricle must be reached via the cerebral parenchyma using a trans-cortical or trans-callosal approach. In either approach, when the approach site is appropriate, surgical invasion can be minimized. However, when surgery for the dominant hemisphere is necessary, there is a risk of cortical injury or postoperative development of epilepsy. When only part of the aneurysm is exposed to the intraventricular space, the parent artery should be confirmed by sacrificing a part of the parenchyma in the ventricular wall for complete aneurysm occlusion.

There are several recent studies on endovascular treatment for distal perforating artery aneurysms19–22) in which endovascular treatment was performed for aneurysms developing in the distal lateral lenticulostriate artery (lLSA) as the perforating artery of the middle cerebral artery (MCA). However, there have been no studies on endovascular treatment for aneurysms at a distal site of the mLSA arising from the ACA. This may be partly due to the small number of cases, but there have been cases, such as that reported by Matushita et al.,10) in which endovascular treatment was abandoned due to difficulty in approach. Although the mLSA arose from the ACA in this patient, it arises in an acute angle to the course of the ACA and the ipsilateral approach was difficult. In patients such as ours demonstrating well-developed AComA, the contralateral approach may enable catheter insertion into the mLSA.

In endovascular treatment, choices of embolization using coils or liquid embolic material such as NBCA. To insert the catheter to the distal site of the perforating artery, embolization with a liquid embolic material using a flow directed catheter is rational.19–21) Although the mLSA territory differs among individuals, cerebral infarction in the perfusion area of a well-developed mLSA has a risk of apathy and changes in personality.23,24) As this patient had undergone implantation of a biventricular pacing implantable cardioverter defibrillator, MRI evaluation was not possible, but no development of clear cerebral infarction was noted on postoperative CT. In patients such as ours in whom catheterization close to the aneurysm is impossible, proximal perforating artery embolization is performed, which increases the risk of cerebral infarction in the perforating artery perfusion area; therefore, careful selection between embolization and direct surgery is necessary.

Conclusion

Embolization with NBCA was performed in a patient with a distal mLSA aneurysm presenting with PIVH, and a favorable outcome was obtained. When CTA demonstrates spot enhancement on the lateral side of PIVH, there is a possibility of a distal perforating artery aneurysm, and cerebral angiography and radical surgery to prevent re-bleeding should be considered. In the future, additional cases are necessary, but endovascular treatment for this condition may be a safe and effective treatment option.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Alexander Zaboronok, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Tsukuba, for manuscript revision.

Disclosure Statement

We declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1).Miyake H, Ohta T, Kajimoto Y, et al. : Intraventricular aneurysms--three case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2000; 40: 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Flint AC, Roebken A, Singh V: Primary intraventricular hemorrhage: yield of diagnostic angiography and clinical outcome. Neurocrit Care 2008; 8: 330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Arboix A, García-Eroles L, Vicens A, et al. : Spontaneous primary intraventricular hemorrhage: clinical features and early outcome. ISRN Neurol 2012; 2012: 498303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Hameed B, Khealani BA, Mozzafar T, et al. : Prognostic indicators in patients with primary intraventricular haemorrhage. J Pak Med Assoc 2005; 55: 315–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Barnaure I, Liberato AC, Gonzalez RG, et al. : Isolated intraventricular haemorrhage in adults. Br J Radiol 2017; 90: 20160779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Lee SH, Park KJ, Park DH, et al. : Factors associated with clinical outcomes in patients with primary intraventricular hemorrhage. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23: 1401–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Wada R, Aviv RI, Fox AJ, et al. : CT angiography “spot sign” predicts hematoma expansion in acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2007; 38: 1257–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Ellis JA, D’Amico R, Altschul D, et al. : Medial lenticulostriate artery aneurysm presenting with isolated intraventricular hemorrhage. Surg Neurol Int 2011; 2: 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Hagihara Y, Ninomiya K, Mizushima Y, et al. : Distal A1 perforating artery aneurysm presenting with intraventricular hemorrhage: a case report. Jpn J Neurosurg 2006; 15: 463–467. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 10).Matushita H, Amorim RL, Paiva WS, et al. : Idiopathic distal lenticulostriate artery aneurysm in a child. J Neurosurg 2007; 107: 419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Kim T, Bang JS, Hwang G, et al. : Idiopathic lenticulostriate artery pseudoaneurysm protruding into the lateral ventricle: a case report. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg 2013; 15: 246–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Srivastava T, Sannegowda RB, Sharma B, et al. : Lenticulostriate artery aneurysm presenting as primary intraventricular haemorrhage. BMJ Case Rep 2013; 2013: bcr2013009968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Nomura M, Baba E, Shirokane K, et al. : Aneurysm of lenticulostriate artery in a patient presenting with hemorrhage in the caudate nucleus and lateral ventricle-delayed appearance and spontaneous resolution. Surg Neurol Int 2018; 9: 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Arai Y, Matsuda K, Isozaki M, et al. : Ruptured intracranial aneurysms associated with moyamoya disease: three case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2011; 51: 774–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Kawai K, Narita K, Nakayama H, et al. : Ventricular hemorrhage at an early stage of moyamoya disease–case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1997; 37: 184–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Yanaka K, Tsuboi K, Fujita K, et al. : Distal anterior choroidal artery aneurysm associated with an arteriovenous malformation. Intraoperative localization and treatment. Surg Neurol 2000; 53: 546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Nishihara J, Kumon Y, Matsuo Y, et al. : A case of distal anterior choroidal artery aneurysm: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1993; 32: 834–837; discussion 837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Ishikawa T, Nakayama N, Yoshimoto T, et al. : How does spontaneous hemostasis occur in ruptured cerebral aneurysms? Preliminary investigation on 247 clipping surgeries. Surg Neurol 2006; 66: 269–275; discussion 275–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Larrazabal R, Pelz D, Findlay JM: Endovascular treatment of a lenticulostriate artery aneurysm with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. Can J Neurol Sci 2001; 28: 256–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Harreld JH, Zomorodi AR: Embolization of an unruptured distal lenticulostriate aneurysm associated with moyamoya disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: E42–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Hwang K, Hwang G, Kwon OK: Endovascular embolization of a ruptured distal lenticulostriate artery aneurysm in patients with moyamoya disease. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2014; 56: 492–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Ishikawa E, Yanaka K, Meguro K, et al. : Treatment of peripheral aneurysms of the posterior circulation. No Shinkei Geka 2000; 28: 337–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Dunker RO, Harris AB: Surgical anatomy of the proximal anterior cerebral artery. J Neurosurg 1976; 44: 359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Phillips S, Sangalang V, Sterns G: Basal forebrain infarction. A clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Neurol 1987; 44: 1134–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]