Background:

Preterm birth is a significant contributor to neonatal morbidity and mortality. Despite legislative efforts to increase pediatric drug development, neonatal clinical trials continue to be infrequent. The International Neonatal Consortium (INC) includes nurses as key stakeholders in their mission to accelerate safe and effective therapies for neonates.

Purpose:

INC developed a survey for nurses, physicians, and parents to explore communication practices and stakeholders' perceptions and knowledge regarding clinical trials in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs).

Methods:

A stepwise consensus approach was used to solicit responses to an online survey. The convenience sample was drawn from INC organizations representing the stakeholder groups. Representatives from the National Association of Neonatal Nurses and the Council of International Neonatal Nurses, Inc, participated in all stages of the survey development process, results analysis, and publication of results.

Results:

Participants included 188 nurses or nurse practitioners, mainly from the United States, Canada, the European Union, and Japan; 68% indicated some level of research involvement. Nurses expressed a lack of effective education to prepare them for participation in research. Results indicated a lack of a central information source for staff and systematic approaches to inform families of studies. The majority of nurses indicated they were not asked to provide input into clinical trials. Nurses were uncertain about research consent and result disclosure processes.

Implications for Practice and Research:

This study indicates the need to educate nurses in research, improve NICU research communication through standardized, systematic pathways, and leverage nurse involvement to enhance research communication.

Keywords: clinical trials, informed consent, neonatal intensive care unit, neonates, newborn, nurses, research design, results disclosure

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Preterm birth is a leading cause of infant mortality and morbidity.1 Medications are an important aspect of the care of preterm infants. However, despite legislative efforts to increase pediatric drug development in the United States and Europe, clinical trials focused on neonatal drug development have been infrequent. As most drugs used in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) are used in an off-label capacity, it is important that drug studies are conducted in neonates to address gaps in labeling information.2 History shows that implementing care without adequate research has led to unintended adverse consequences. Examples include gray baby syndrome related to chloramphenicol use, gasping syndrome from use of benzyl alcohol as a bacteriostatic agent, intravenous injections of vitamin E leading to deaths, and long-term side effects of dexamethasone used to treat chronic lung disease.3

The International Neonatal Consortium (INC) is a multi-stakeholder consortium (nurses, neonatologists, parents, regulators, and industry representatives) that addresses barriers to the development of drugs and therapies for neonates.4 The National Association of Neonatal Nurses (NANN) and the Council of International Neonatal Nurses, Inc (COINN), are the 2 nursing organizations actively participating in INC since its inception in 2015. The INC Communications Workgroup developed a multi-stakeholder survey to explore communication practices and stakeholders' perceptions and knowledge regarding the conduct of clinical trials in the NICU. The survey was created to address 3 stakeholder groups simultaneously (physicians, nurses, and parent advocates) with a set of questions specifically designed for each group. Nurse representatives participated in all stages of the survey development process, as well as data acquisition and analysis, and coauthored the primary article.5 The article5 provided perspectives of all stakeholder groups on research-related education and communication practices in the NICU. Differences were noted with respect to the unmet needs of sick neonates, research mission of the NICU, education/training of the research team, and research communication provided to parents. Authors concluded that engagement of nurses and parents at all stages of NICU research is currently suboptimal.5 Silberstein,6 in an editorial on the article,5 discussed the differences in those perspectives despite the unanimity across the groups, in support of the principle that research should be an important component of an NICU's work. This article contains unpublished nursing results and discusses potential opportunities to prepare nurses for engagement in NICU research. It includes data on the demographics of the nurse respondents, a nursing-targeted literature review that focuses on survey development, and neonatal nurse perspectives on research education and training, research communication practices, research consent, and dissemination of research results.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Nurse stakeholders conducted a targeted review of the literature prior to survey development for years 2005-2017 to assess research communication practices in NICUs. Key words were “family-centered care,” “informed consent,” “culture of research,” “clinical trials,” “research disclosure,” “communication,” “NICU,” “newborn,” “neonate,” “family,” “education,” “organizational structure,” “interprofessional relations,” “results reporting,” and “clinical trials coordinator.” The search was conducted for English language and in peer-reviewed journals. The goal of the literature review was to identify gaps in knowledge related to research communication strategies in the NICU to inform the development of the multi-stakeholder survey. An additional limited search relevant to research communication findings was conducted specific to this article and included up to 2020.

Table 1 illustrates articles identified and evaluated as part of the literature review, along with relevant research communication findings. While the literature search found studies on the informed consent process and principles of family-centered care, it exposed a paucity of available information on communication practices regarding research disclosure, flow of communication in the NICU, strategies to communicate essential information across care teams, and training of neonatal personnel specific to the conduct of clinical trials. It was rare that nurses were participants in the included studies. These findings led the research team to identify 5 domains for further evaluation. The survey was developed to evaluate these domains: (1) role of research in the NICU; (2) education and training; (3) current NICU communication flow; (4) research consent processes; and (5) research results disclosure.

TABLE 1. Findings of Literature Review Conducted to Identify Gaps in Research Communication Strategies.

| Topic | Citation | Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Role of Nurse in Research | Reid et al10 Browning et al12 |

Nurse is viewed as closest ally for infants/families. Nurses' perceptions toward clinical trials may impact the families' decision to participate. Nurses who felt more positive about the research question, the training received, and the study team were more likely to have positive perceptions of trial. When nurses held negative perceptions (unnecessary or too dangerous), attitudes may negatively impact success. Nurses often complete research-related tasks, serve as a liaison to the study team, and can identify eligible study patients. |

| Health Literacy | Burks and Keim-Malpass13 | Health literacy and anxiety may impact ability to process information about clinical trial or research. Suggest nurses can support families with limited health literacy. |

| Family-Centered Care | COINN14 Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- And Family-Centered Care15 NANN16 |

Advocates that parents be included in various activities within a unit, not only in providing care for their own infant but also in advising on clinical study design or as partners in educational programming within an institution. |

| Education | March of Dimes17 | Provided general education for parents on clinical trials for infants. |

| Neonatal Research | Bucci-Rechtweg and Ward11 Lussky et al3 |

Outlines factors influencing the current predicament where >90% of neonates in the NICU are exposed to medications that are off-label. Implementing care without adequate research led to unintended adverse consequences. |

| Informed Consent | Megone et al18 Wilman et al19 Guillot et al20 |

Parents understand their role in consent but desire the input of others, including clinicians, caring for their infants. Neither of the systematic reviews included the nurse community within their discussion of the role of the “clinician” during the informed consent process. Families may prefer to hear about clinical trial directly from the physician. Lack of knowledge was a barrier to participating in clinical trials. Absence of nursing members in research communication was noted as a key limitation. |

| Research Results Disclosure | Elzinga et al21 Long et al22 Augustine et al23 |

Adult studies surveyed potential research participants for preference for reporting study results. Preferred modes of reporting differed between these studies; however, receiving letters, information via e-mail, or having results available on a designated Web site was preferred. If patient outcomes were negative, result disclosure in person were preferred. Adult clinical trial that used teleconferences (multiple time options) to receive study updates. The majority of research participants found this useful and were satisfied with study communication. |

Abbreviation: NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

What This Study Adds

Provide information on research communication practices in the NICU.

The highest need for additional nursing education is specifically in the design and conduct of academic studies, drug development, and special protections to protect the rights of neonatal study participants.

There is a recognized need for research as a central core component to the mission of the NICU.

METHODS

Design

The questionnaire was developed using a stepwise consensus approach with input from relevant stakeholders (neonatologists, nurses, regulators, parents, and pharmaceutical industry representatives) to assess global research-related communication practices in the NICU. The survey used cloud-based software (SurveyMonkey), provided from a link on the Critical Path Institute INC Web landing page. The survey was conducted in English. Detailed methods and overall findings were previously published.5

Sample

Dissemination of the survey to nursing stakeholders was done by NANN and COINN members through Listserv or key members of their network. Both nursing organizations took active steps to recruit nurse participation. The convenience sample provided voluntary, anonymous responses. Compensation for participation was not provided.

Statistical Analyses

As in the previous publication,5 survey results in this article include only descriptive statistics. The authors reviewed and analyzed results in a series of meetings designed to identify key findings for nurses within each domain.

IRB Approval

The protocol “The Culture of Research Communication in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Key Stakeholder Perspectives” received an Internal Review Board (IRB) exemption by the University of Utah IRB (IRB_00143250).

RESULTS

Sample Demographics

Of the survey respondents, 188 self-identified as nurses or nurse practitioners. A predominant number of nurses were from the United States (78%; n = 147), and all geographic regions within the United States were well represented (see Supplemental Digital Content Table 1A, available at: http://links.lww.com/ANC/A193). Respondents from outside the United States (see Supplemental Digital Content Table 1B, available at: http://links.lww.com/ANC/A194) included Canada (3%), the European Union (10%), Japan (3%), and others (5%).

Current nursing position and research involvement are shown in Supplemental Digital Content Figures 1A and 1B (available at: http://links.lww.com/ANC/A195 and http://links.lww.com/ANC/A196, respectively). The majority of respondents identified as neonatal nurses. More than two-thirds (68%) of the nursing respondents indicated some level of research involvement—formal (member of a designated research team) (8%), both patient care and research responsibilities (17%), or informal (43%). Of the nurse respondents, more than 60% were educated at the master's degree level or higher. Most nurses' work settings were in either level 3 or level 4 neonatal units.

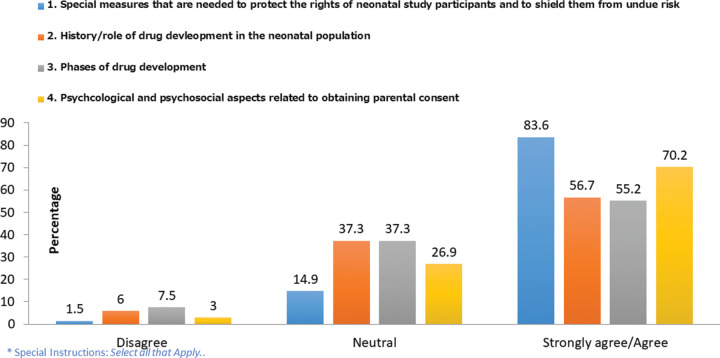

Education and Training of Neonatal Personnel in the Role of Neonatal Research

The respondents were asked whether their hospital or NICU trained personnel in the role of clinical studies and study consent processes. Of the 129 nurses who responded, more than half (57%) indicated that their institution provided such training for staff. Nurses who indicated that their institution provided training were further asked a series of questions as to whom the training was provided and how this was done. Only 67 responded to the additional questions. More than half (58%) indicated that training was provided to all staff members who cared for patients enrolled in research studies. The most frequently offered methods of training by employers were informal coaching (46%), online teaching (40%), and reading materials (40%). Training was most frequently noted as being led by the research nurse or coordinators (52%), followed by research physicians (37%) and neonatologists (36%). The respondents who indicated that their institution provided research training were asked their level of agreement with the research concepts included in the institutional training they received as illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Level of agreement that these concepts are included in institutional training for nurses (n = 67).*

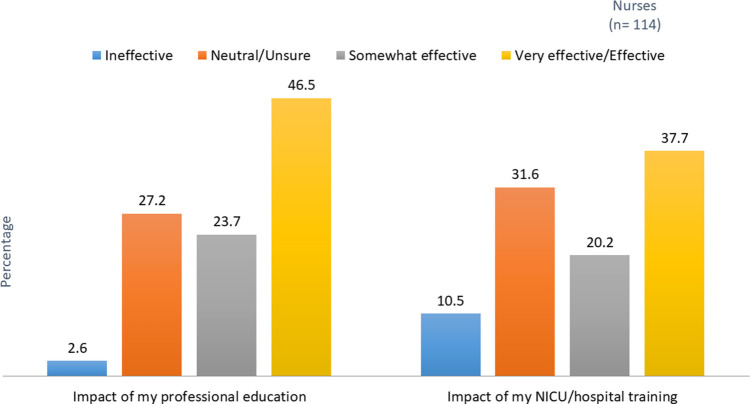

In addition, nurses were asked whether topics related to pediatric or neonatal research were included in their professional education in an academic setting (Figure 2). Eight topics were assessed in the survey as well as an option to indicate no professional training was provided, an option selected by more than a quarter of the nurse respondents. Figure 3 reports nurses' assessment of the effectiveness of both hospital and professional education they received about research/clinical trials.

FIGURE 2.

Pediatric/neonatal topics included in your academic education (n = 114).*

FIGURE 3.

Effectiveness of the education or training received in professional education and in the NICU/hospital. NICU indicates neonatal intensive care unit.

Nurses identified multiple areas of further education related to pediatric/neonatal research needed to support them in research activities in their NICU. The top 3 areas were design and conduct of academic studies, drug development, and the special protections to protect the rights of neonatal study participants. Supplemental Digital Content Figure 2 (available at: http://links.lww.com/ANC/A197) provides the complete listing of needs identified for professional education or institutional training.

Current NICU Communication Flow

Nurses' perceptions of their institution's current communication practices regarding research involving neonates are shown in Figure 4. The majority of respondents either noted an absence of a central source of information or were “Unsure.” Similarly, the majority of respondents noted either an absence of a system to inform families or were “Unsure.”

FIGURE 4.

Institutions' current methods of communication regarding research involving neonates (n = 130). NICU indicates neonatal intensive care unit.

Nurses were asked their perception of the effectiveness of current methods of communication regarding research involving neonates. Only 27 respondents indicated that their institution had a system in place. Of these systems, specific research meetings were rated as most effective for both upcoming (56%) and ongoing (67%) research studies.

Whether nurses are asked to provide input into study conduct within their institution was explored. A total of 114 nurses responded. Of the respondents, 17% agreed that they were asked to provide input, whereas 46% reported they were not. The remaining 38% indicated either “Neutral” or “Unsure.”

Research Consent Process

Nurses' perspectives on their institution's clinical and research consent approach were then explored. A total of 112 nurses responded. When asked whether an admission or blanket consent was required for routine care, 67% indicated that this was required. When asked at what time consent for routine clinical care and study participation was obtained, 69% indicated that the consent was obtained at different times.

A small proportion of nurses noted that consent for study participation is “Usually” (11%) or “Always” (3%) sought from families before the birth of a potentially sick neonate or in advance of an anticipated event in the NICU (15% vs 6%, respectively). More respondents were “Unsure” about consent before birth (32%) and in advance of anticipated events (40%). A large segment of respondents were “Unsure” about whether continuous consent (50%) and affirmation of research consent (46%) were offered in their NICU.

Results Disclosure

Ninety-three nurses provided perceptions of the communication practices of results disclosure (see Supplemental Digital Content Figure 3, available at: http://links.lww.com/ANC/A198). The majority (84%) of the nurse respondents agreed that families that consent to their infant's study participation should have study results made available to them, and the majority also held the belief that results from both pharmaceutical studies and academic studies are required to be made public (71% and 69%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

This study is believed to be the first survey that specifically reports nurses' perceptions regarding the culture of communication about research in the NICU. Nurses played a key role in the development, analyses of results, and coauthorship of the primary publication5 of the culture of research survey. Although conducted as a multi-stakeholder survey, nurses represented the largest cohort of respondents. The respondents represented nurses from around the world, at all levels of care, and in various NICU roles. Responding nurses were highly educated, with more than 60% having attained master's degrees and higher. It is of concern that this highly educated participant group indicated that more research training was needed. Given the high educational attainment of the respondents, the generalizability of these results should be viewed with caution but might suggest that the need for research education in nurses with lower educational attainment or less formal research training, who were less represented in the sample, is even greater.

The literature acknowledges the potential value of nurses in the research process but does not provide sufficient evidence to optimize nurse support for research. The survey indicates that nurses support their improved engagement to meet the unique challenges of neonatal research.

Education and Training of NICU Personnel on the Role of Research

The survey results suggest a gap in the understanding of research fundamentals and processes specific to the unique requirements for neonatal drug development. There was a notable perception gap for the nurse respondents regarding the availability of adequate education and training about neonatal research. Nurses expressed a lack of effective education to prepare them for competent participation in neonatal research.

Only slightly more than half of respondents indicated that training about research was available within their institution before approaching parents for consent. This may be a concern, as it is accepted practice in some institutions for nurses to obtain parental consent for clinical trials. General education about research and the research process may be obtained outside of a nurse's NICU or hospital. In this survey, a question was specifically asked about the perception of their institutions' training opportunities and therefore the results may not reflect all sources of education. Nevertheless, nurses are likely to benefit from more access to research training and education.

As for professional training about research and perceived effectiveness, the results should be interpreted with caution as the nursing respondents had a wide range of educational preparation. Most of the nurses who responded did not receive training in their professional education programs in the areas of the drug development process, as well as design and conduct of drug development research. There were only 3 areas where more than half of the nurses responded that they received training as part of their professional education programs. These were the role of research in improving care and establishing new and effective treatments, evaluating clinical study design, and critiquing research results. These survey results highlight an opportunity to fill an educational gap. We acknowledge multiple factors that influence academic curriculum including time, finances, and available expertise, which may make the addition of more rigorous research education untenable. The inclusion of research competencies in basic or advanced-level nursing programs, as well as provision of research-focused education through professional organizations, may serve to bridge this gap.

In addition, nurses are well positioned to engage with parents and create a favorable perspective about research. In this way, nurses knowledgeable about the role of research and the research process can be leveraged to speak comfortably with parents about the importance of research in improving outcomes in the NICU despite potential risks. Nurses' comfort level in research communication with parents may potentially impact parents' level of comfort and confidence when approached to consider a study for their infant.

Current NICU Communication Flow

A key message from the survey results was that there is no central source of information for nursing staff, nor a systematic approach to inform families about ongoing or upcoming studies. A small group of nurses identified that a system was in place to communicate information to nursing staff about ongoing research studies. These nurses indicated a preference for direct face-to-face encounters, such as direct contact with research staff, staff meetings, or a specific meeting to discuss the research. Although generalizability is limited because of the sample size, nurses' preferences in how to receive information deserve attention.

In addition, the majority of nurses were not asked to provide input into a study, which may reflect the lack of a system to communicate research information to nurses. These survey results highlight a research communication gap specific to nurses who represent an important stakeholder group within the NICU before, during, and after the research. Addressing this gap and sharing best communication practice should be undertaken, as it is essential to increase the involvement of NICU nurses and parents in all stages of research.

Research Consent Process

Several questions were asked of respondents to determine the relationship between obtaining clinical consent for care and procedures versus consent for research. Within our survey, respondents reported that when consent is obtained for clinical care, this consent is typically obtained by a different person and at a different time than the consent for enrollment in a research study.

Many nurses were unsure about the research consent process within their institutions. This may suggest the minimal involvement respondents had in obtaining consent. It is also consistent with the survey finding indicating a lack of training on the research consent process. However, nurses who are knowledgeable about the research consent process will be better prepared to support parents in their decision-making process when they are invited to provide consent for the infant's participation. In addition, nurses who are aware of upcoming or ongoing research may be better suited to identify patients eligible for study participation and to alert the appropriate team member for an initial interaction with families about a specific research study.

Results Disclosure

Nurses strongly agreed that families of study participants should receive study results and were knowledgeable that sponsors of research studies are required to make results publicly available.7–9 While there are regulatory requirements to ensure public disclosure of research results, providing results directly to parents by the research investigator is difficult to implement and has not been standardized. The results disclosure process must be planned and implemented according to approval by the IRB governing the study and regional requirements.

In previous reporting of the results of this survey,5 nurses did not perceive that there is a consistent or a standard approach to how institutions provide results to parents of study participants, retain or update information to ensure results are reported to parents, or assess how parents would prefer to receive results. This gap is another opportunity for nurses to be engaged to support and improve research processes. Identifying parental preferences is critical in designing a standard process for how to deliver neonatal trial results upon study completion. Parents have a high level of trust in the nurses caring for their infant.10 Nurses are also in a unique position to hear and identify parental preferences. Nurses can use their unique knowledge of parents' needs and preferences to inform the institutional processes to ensure relevant research communication for parents and a process to effectively contact parents when information becomes available. Nurses and nurse practitioners may be involved in the clinical follow-up of these patients and know of potential avenues of communication.

Role of Research in the NICU

Nurse perspectives on the role of research in the NICU have been reported previously5 but deserve further discussion considering the additional survey results on education and training reported in this article. It is encouraging that the majority of the nurse respondents embrace the concept of research as an essential core component to the NICU mission. However, there were disparate perspectives on whether research is a central core mission within the current work of individual nurses. These disparate perspectives could undermine the success of research in the unit if nurses do not perceive their participation as serving an important function.

Nurses are the members of the care team who administer medicines in the NICU to sick infants and monitor their effect. Yet, previously reported5 survey results revealed that only half of the nurse respondents perceive a need for additional neonatal drug therapies, despite the widespread use of off-label medications.11 Nurses may have little experience with regulatory processes and product approvals, as relatively few new medications have been approved for neonates in the last decade. The common off-label medication practices in the NICU also remind us of the need to conduct drug studies that provide adequate information for safety, dosing, and efficacy of our currently used medications.

Our findings suggest that many nurses are unfamiliar with the role of neonatal research in informing how to use therapies and improve neonatal care. While a significant number of respondents agree that pharmaceutical studies are needed, a proportion of nurses either do not see or are unsure about a role for pharmaceutical studies to guide medication use in the NICU. It is possible that their perceptions stem from general differences across stakeholders in the background education regarding clinical research or drug development, as well as less experience in regulated pharmaceutical research. More targeted education for nurses could be beneficial, not only to promote research surrounding medication use in neonates but also to increase recognition that infants may be at unknown risk from medications (alone or in combination) commonly used in the NICU that have been inadequately studied. Nurses who are knowledgeable about the role of research are essential advocates to leverage in facilitating a broader understanding of why research is needed in the NICU and to engage in building research communication strategies.

Nursing research knowledge and participation gathered through this survey were made possible because of the INC decision to include nurses as key stakeholders in efforts to eliminate barriers to neonatal research. Nurses are essential members of the neonatal care team and also have a unique perspective on clinical trials, and this survey afforded them the opportunity to describe their role in neonatal research. A multi-stakeholder team is needed at the bedside where research is ongoing so that nurses, along with the entire team, clearly understand the safeguards in place for vulnerable populations, the function of safety monitoring groups, the role of research study personnel, and the specific study protocol. Nurses are critical to the success of a clinical trial, either in following a treatment protocol or in being an educated study team member to support parents and help them better understand the study. Nurses can also be the liaison with the research team to identify any changes including adverse events in patients enrolled in interventional studies. When nurses embrace the essential role of research in the NICU mission, they can become a powerful and meaningful partner in educating the broader NICU community and leading the culture change related to research.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE AND FUTURE RESEARCH

There are gaps in knowledge about the roles of nurses in research, within their professional role, and within the multidisciplinary team. The findings of the survey provide a foundational step toward filling these gaps. Many opportunities were identified for the nursing profession related to how we communicate about the role for, conduct of, and processes related to research. Nurses reported a lack of familiarity with the foundational aspects of research and the role that different types of research may play in informing neonatal care; this can be reinforced by education. Some results, such as knowledge about off-label medication use and whether pharmaceutical studies are needed, indicate misconceptions. Neonatal nurses will benefit by being informed or reminded of the historical misfortunes related to the lack of research prior to broad use of a drug or intervention.

Further use of this survey or a similarly constructed survey focused on adding to our understanding of nursing perspectives from regions underrepresented within our cohort may be helpful. A survey designed to capture more input from those actively involved in research trials and with a larger number of respondents would aid in making results more generalizable, at least to a specific region, country, or setting. Additional survey information may be helpful to further investigate trends seen in this survey, such as the impact of specific educational levels, previous involvement in research, specific role in nursing, years of experience, and the impact of clinical research team support on beliefs and knowledge around neonatal research studies.

Future research could explore various types of educational design and delivery pathways for nurses and the methods' effectiveness. Other areas of exploration should include determination of education that is effective in preparing nurses who can inform and better support families contemplating participation in clinical trials. The effect of nurse involvement in clinical trials on consent rates would also be beneficial.

Silberstein6 presents a vision of a culture of care that strives for more collaborative and inclusive relationships, both in caregiving and in research. Toward that aim, we hope that sharing the additional findings of nurse perceptions from this global survey on the culture of research communication leads to opportunities to leverage the unique and important role of neonatal nurses as key stakeholders to enhance the conduct of neonatal clinical research and improve care for premature and sick neonates.

Summary of Recommendations for Practice and Research.

| What we know: |

|

| What needs to be studied: |

|

| What can we do today: |

|

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Alicia West, Laura Butte, Sarah Spieth, Lynn Hudson (C-Path); Bob Ward, Kelly Wade, Christina Bucci-Rechtweg; INC Communications Workgroup; and the nurses who contributed to the survey.

Critical Path Institute is supported by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and is 54.2% funded by the FDA/HHS, totaling $13,239,950, and 45.8% funded by nongovernment source(s), totaling $11,196,634. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, FDA/HHS or the US government.

Competing Interests: Authors 1, 3, 4 declare no competing interests. Author 2, Wakako M. Eklund, is currently serving on the editorial board at ANC.

Ethical Approval: The original multi-stakeholder study protocol, “The Culture of Research Communication in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Key Stakeholder Perspectives,” received an Internal Review Board (IRB) Exemption from the University of Utah IRB (IRB_00143250). The agreement to participate in the survey constituted as the individual consent for participation.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.advancesinneonatalcare.org).

Contributor Information

Sandra Sundquist Beauman, Email: cnsconsultingneo@gmail.com.

Wakako M. Eklund, Email: wakako.eklund@pediatrix.com.

Mary A. Short, Email: maryashort1026@gmail.com.

Carole Kenner, Email: kennerc@tcnj.edu.

References

- 1.Stewart DL, Barfield WD; Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Updates on an at-risk population: late-preterm and early-term infants. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192760. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCune SK, Mulugeta YA. Regulatory science needs for neonates: a call for neonatal community collaboration and innovation. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:135. doi:10.3389/fped.2014.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lussky RC, Cifuentes RF, Siddappa AM. A history of neonatal medicine—past accomplishments, lessons learned, and future challenges. Part 1—the first century. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2005;10(2):76–89. doi:10.5863/1551-6776-10.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner MA, Davis JM, McCune S, Bax R, Portman RJ, Hudson LD. The International Neonatal Consortium: collaborating to advance regulatory science for neonates. Pediatr Res. 2016;80(4):462–464. doi:10.1038/pr.2016.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Degl J, Ariagno R, Aschner J, et al. The culture of research communication in neonatal intensive care units: key stakeholder perspectives. J Perinatol. 2021;41(12):2826–2833. doi:10.1038/s41372-021-01220-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silberstein D. Not an exclusive club anymore. NIDCAP Dev Observer. 2022;15(2):15–17. doi:10.14434/do.v15i1.33787. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ85/pdf/PLAW-110publ85.pdf. Published September 27, 2007. Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 8.Commission guideline—guidance on posting and publication of result-related information on clinical trials in relation to the implementation of Article 57(2) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 and Article 41(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006. Off J Eur Union. 2012;55:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical trials registration and results information submission. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2016;81(183):64981–65157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid S, Bredemeyer S, Chirarella M. Integrative review of parents' perspectives of the nursing role in neonatal family-centered care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2019;48(4):408–417. doi:10.1016/j.jogn.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bucci-Rechtweg CM, Ward RM. Tiny and forgotten: a call for focused neonatal policy reform. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2019;53(5):615–617. doi:10.1177/2168479018821922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browning B, Page KE, Kuhn RL, et al. Nurses' attitudes toward clinical research: experience of the therapeutic hypothermia after pediatric cardiac arrest trials. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(3):e121–e129. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burks AC, Keim-Malpass J. Health literacy and informed consent for clinical trials: a systematic review and implications for nurses. Nurs Res Rev. 2019;9:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.COINN. Home page. http://coinnurses.org. Published 2016. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 15.Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394–404. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NANN. Home page. http://nann.org. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 17.March of Dimes. Clinical trials for your baby. https://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/clinical-trials-for-your-baby.aspx. Published 2017. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- 18.Megone C, Wilman E, Oliver S, Duley L, Gyte G, Wright J. The ethical issues regarding consent to clinical trials with pre-term or sick neonates: a systematic review (framework synthesis) of the analytical (theoretical/philosophical) research. Trials. 2016;17(1):443. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1562-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilman E, Megone C, Oliver S, Duley L, Gyte G, Wright JM. The ethical issues regarding consent to clinical trials with pre-term or sick neonates: a systematic review (framework synthesis) of the empirical research. Trials. 2015;16:502. doi:10.1186/s13063-015-0957-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillot M, Asad S, Lalu MM, et al. So you want to give stem cells to babies? Neonatologists and parents' views to optimize clinical trials. J Pediatr. 2019;210:41–47.e41. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elzinga KE, Khan OF, Tang AR, et al. Adult patient perspectives on clinical trial result reporting: a survey of cancer patients. Clin Trials. 2016;13(6):574–581. doi:10.1177/1740774516665597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long CR, Stewart MK, Cunningham TV, Warmack TS, McElfish PA. Health research participants' preferences for receiving research results. Clin Trials. 2016;13(6):582–591. doi:10.1177/1740774516665598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Augustine EF, Dorsey ER, Hauser RA, Elm JJ, Tilley BC, Kieburtz KK. Communicating with participants during the conduct of multi-center clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2016;13(6):592–596. doi:10.1177/1740774516665596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]