Abstract

Objective:

To examine the relationship between stigma and mental health help-seeking among Asian American and Asian international college students.

Participants:

Asian American college students (401 men, 858 women) and Asian international college students (384 men, 428 women).

Methods:

Data from the 2018–2019 Healthy Minds Study were used to assess perceived stigma, personal stigma, and help-seeking behaviors of college students.

Results:

Personal stigma mediated the relationship between perceived stigma and professional help-seeking intentions. The relationship between perceived stigma and personal stigma differed by international status, such that the relationship between perceived stigma and personal stigma was stronger for Asian international students. The indirect effect between perceived stigma and professional help-seeking via personal stigma also differed by international status.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that, consistent with prior work, stigma impacts help-seeking among Asian college students and international student status affects the strength of the key relationship between perceived stigma and personal stigma.

Keywords: Asian, gender, help seeking, international, stigma

Introduction

International student populations in United States (US) colleges have risen steadily for the past few decades.1 Colleges prioritize increasing international student enrollment, however, the infrastructure for support services for growing numbers of international students has not grown commensurately.2 Asian international students (i.e., students from Asian countries who are not US citizens or permanent residents) make up the greatest percentage (70.1%) of international students, with over 750,000 Asian international students attending US colleges.1 This statistic brings attention to the need for US colleges to ensure that they are serving this large and growing part of their student body. Asian international students join a national student body that includes American citizens of Asian ancestry. In 2017, 65% of Asian Americans 18- to 24-year olds enrolled in a US college in comparison to 41% of White Americans, 36% of Black Americans, and 36% of Hispanic Americans.3 Thus, there is a clear need for US colleges to attend to cultural factors that may influence the well-being of Asian international and Asian American students. College counseling centers in particular may be important, but stigmatized, resources.

There are salient differences between Asian international students and Asian American students. In addition to the typical struggles of adapting to college, international students face obstacles including acclimating to a foreign culture, facing language barriers and discrimination, coping with isolation, and encountering mistreatment from academic faculty, among other challenges.4,5 This process of adjustment to the dominant social culture is called acculturation, and stress induced by acculturation is called acculturative stress.6 Asian American students may face challenges due to the influence of cultural-familial attitudes toward help-seeking.7 Stress can result in mental health problems that college students may be able to address through college counseling services. Campus counseling center services can have lower barriers to access, such as not requiring insurance coverage or travel to professional mental health service offices. Therefore, it is important to understand obstacles to help-seeking among international and American Asian students, so that campus counseling centers may fulfill their missions to support these students.

Asian help-seeking attitudes

Asian Americans have significantly lower rates of help-seeking compared to other US racial groups.8–10 Asian Americans are exposed to cultural values related to help-seeking through their family members, whereas Asian international students may be immersed in these cultural values when raised in their home culture that established these norms.7,11 Based on a study examining the etiological beliefs surrounding mental illness in American and Chinese cultures, Western beliefs (i.e., psychological problems are caused by environmental/hereditary factors) had a positive association with mental health help-seeking behaviors while Asian beliefs (i.e., psychological problems are caused by social–personal factors) had a negative association with mental health help-seeking behaviors.11 Asian cultural values stress the importance of restraining emotions, avoiding shame, and saving face. These values may conflict with self-disclosure and emotional expression, which are encouraged in traditional forms of counseling in America.7 Due to stigma toward professional mental health help-seeking in Asian cultures, seeking mental health services can be a source of shame in the family system.7,11 In a study examining the relationship between adherence to Asian cultural values, stigma, and mental health help-seeking in a sample of Asian American college students, adherence to Asian values was associated negatively with help-seeking attitudes, as was mental health help-seeking stigma.7 Because of these differences, it is possible that stigma toward help-seeking may be more salient for Asian international students in comparison to Asian Americans and may play a significant role in inhibiting mental health help-seeking behaviors.

Despite the need for support away from home, Asian international students may be reluctant to seek help. Asian international students report greater discomfort with counseling, and less openness to counseling in comparison to European Americans.12 These negative attitudes toward counseling align with evidence that people from Asian countries have significantly greater resistance to seeking professional help than European Americans.13 It is likely that Asian international students bring their hesitation to counseling with them when they move from their home country to enter US colleges.

Perceived and personal stigma

Mental health help-seeking is stigmatized.14–16 Such stigma can be experienced at both the social level (i.e., perceived stigma, also known as public stigma, that help-seeking is for “crazy people” who are unable to handle their problems) and the personal level (i.e., internalized stigma that other people’s help-seeking would mean that they are unable to handle their own life).

Previous studies have examined the relationships between perceived stigma, personal stigma, and mental health help-seeking with the purpose of analyzing the underpinnings of help-seeking behaviors. Stigma is consistently a strong predictor of help-seeking behaviors.15,17–20 The relationship between stigma and help-seeking has also been upheld in international samples; in samples from Australia, Brazil, Canada, Hong Kong, Portugal, Romania, Taiwan, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates, self-stigma mediated the relationship between perceived stigma and help-seeking attitudes.20 At the same time, there were important differences in the strengths of these relationships that indicate that this relationship may be more prevalent in certain cultures.

Asian people have much lower rates of help-seeking in comparison to the general population in the US. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication found that 17.9% of the general population utilizes any health services, yet only 8.6% of Asian Americans seek out health services.8 Additionally, rates of mental health service usage changed depending on generational status for Asian Americans, with 2.17% of first generation Asian Americans, 3.51% of second generation Asian Americans, and 10.10% of third generation or later Asian Americans seeking out specialty mental health services.8 Other work has also demonstrated that being Asian, international, and male was associated with higher personal stigma,18 and personal stigma was significantly negatively related to mental health help-seeking, consistent with evidence that men are more reluctant to seek mental health help than women.21

Gender and help-seeking

Across myriad studies, men have lower rates of mental health help-seeking behaviors in comparison to women.22,23 A possible explanation for this difference is gender role socialization. Traditional masculine ideologies that promote self-reliance, power, and emotional control can be potential obstacles to help-seeking behaviors.21 Therefore, men may be more reluctant to seek help due to masculine gender role norms that stigmatize help-seeking.18

Studies have examined the relationship between race/ethnicity and help-seeking behaviors in men.24 However, limited studies have focused on help-seeking in the Asian population. For example, Parent et al.’s24 study was limited to White, Black, and Hispanic men in a national sample. Yet, in comparison to other races/ethnicities, Asian students have the highest rates of personal stigma for help-seeking,18 demonstrating the need to extend this body of work to include Asian American and Asian international individuals.

The present study

College mental health centers have an obligation to serve the entire student population. However, systemic and cultural barriers to help-seeking may reduce the number of individuals of Asian ancestry, especially Asian international students, who feel able to seek help. Thus, understanding how stigma impacts help-seeking among this large contingent of US college students is essential to actively reaching out to and encouraging such students to seek mental health counseling.

It is important to recognize that there are significant sociocultural differences between Asian Americans and Asian international students that affect their mental well-being. In the present study, we examine the relationships among perceived stigma, personal stigma, and help-seeking among Asian US (international and American) college students. We differentiate Asian Americans and Asian international students to test whether there is a significant difference in the relationship between stigma and help-seeking in these populations. Informed by the model used in the study by Vogel et al.,20 we hypothesized that (H1) perceived stigma will be associated positively with personal stigma. Additionally, we hypothesized that (H1a) the relationship between perceived stigma and personal stigma would be stronger for Asian international students in comparison to Asian American students. We also hypothesized that (H2) personal stigma will be associated negatively with professional help-seeking intentions for both Asian American students and Asian international students. We further hypothesized that (H3) personal stigma will mediate the relationship between perceived stigma and help-seeking. We also sought to assess whether gender was related to the variables in the study, such that identifying as a man would be associated with higher perceived and personal stigma, and lower help-seeking (H4).

Methods

Participants

The Healthy Minds Study (HMS) collects data annually from college students across the US.25 The 2018–2019 dataset contained responses from 62,025 college students, 2,071 identified as Asian and provided responses to the items for the present study. The analytic sample contained responses from Asian American college students (401 men, 858 women) and Asian international college students (384 men, 428 women). Participants in the analytic sample ranged from 18 to 65 years of age (M = 22.93, SD = 5.51). We conducted an F test on age by gender and international status; age did not differ by gender, F (1, 2067) = 0.16, p = .69. Age did differ by international status, F (1, 2067) = 815.14, p < .001, though this effect size was small; Minternational = 23.74, SDinternational = 5.16; Mdomestic = 22.43, SDdomestic = 5.67; Cohen’s d = 0.24.

The majority of domestic and international students were identified as heterosexual (88.1% and 87.8%, respectively). Most domestic students were enrolled in bachelor’s (64%) programs, followed by PhD (8.4%), associate’s degree (8.1%), medical doctor (7.1%), and masters (6.7%) programs. The majority of international students were enrolled in bachelor’s (44.8%) programs, followed by masters (24.6%), PhD (21.6%), and associate’s (7.1%) programs. The most common areas of study for domestic students were natural sciences or math (16.1%), engineering (13.8%), social sciences (11.1%), and business (11.0%). The most common areas of study for international students were engineering (27.8%), natural sciences and math (21.1%), social sciences (16.3%), and business (15.9%).

Measures

Race/ethnicity

Race was measured with the item, “How do you usually describe your race?” Multiple options could be selected. The responses included (1) White or Caucasian, (2) Black or African American, (3) Asian or Asian American, (4) American Indian, Native American, or Alaskan native, (5) Middle Eastern, Arab, or Arab American, (6) Pacific Islander, (7) Hawaiian Native, (8) Other. Respondents were included in the present analysis if they indicated that they were only Asian or Asian American, excluding participants if they also selected another option.

International status

International status was measured with the item, “Are you an international student?” The response options were yes or no.

Prior therapy

Prior therapy was measured using the item, “In the past 12 months have you received counseling or therapy for your mental or emotional health from a health professional (such as psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or primary care doctor)?” The response options were 1 = yes or 0 = no.

Perceived stigma

Perceived stigma was measured with the item, “Most people think less of a person who has received mental health treatment.” Responses to the item were made on a 6-point scale, from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). The response scale was reversed so that higher scores reflect greater perceived stigma. Prior studies using the HMS data have found this item to be associated negatively with evaluation of campus climate and associated negatively with mental health first aid intention (i.e., providing psychological intervention if someone was experiencing a mental health crisis).26,27

Personal stigma

Personal stigma was measured using the item, “I would think less of a person who has received mental health treatment.” Responses to the item were made on a 6-point scale, from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). The response scale was reversed so that higher scores reflect greater personal stigma. Prior studies using the HMS data have found this item to be associated negatively with feelings of safety for students with PTSD and associated negatively with intention to seek professional help among students in general.26,28

Help-seeking

Help-seeking was measured using the item, “If you were experiencing serious emotional distress, whom would you talk to about this?” A set of options (e.g., friend, family) was available. For the purpose of the present study, we used responses to whether a respondent would talk to a professional clinician (e.g., psychologist, counselor, or psychiatrist), coded as 0 = no, 1 = yes. Prior studies using the HMS data have found this item to be associated positively with self-compassion and positive perceptions of institutions of higher education.28,29

Procedures

The HMS is a Web-based annual survey used to collect data on the mental health of college student populations in the US. The HMS is conducted by the University of Michigan and affiliated universities. In the present study, we used the 2018–2019 dataset which included 79 colleges. The students, which include both undergraduate and graduate students, were randomly selected and contacted via email. Ethical review was approved by the Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Michigan and confidentiality of the responses were ensured by the Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Results

Data were analyzed using Mplus version 8 using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR). As the HMS includes complex sample data, the weighting variable was designated as a sampling weight, and observations included in the analyses were limited to participants who identified as Asian only. International student status was used as a grouping variable. Self-report of ever having been to therapy was used as a control variable. Within the final analytic sample, 0.01% of the data were missing; full information likelihood estimation in Mplus was used to handle the missing data. Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among the variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for variables in the study.

| Asian American |

Asian Int. |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD | M | SD | |

|

| |||||||||

| 1. Gender | 0.178* | 0.012 | 0.107* | 0.015 | 1.680 | 0.466 | 1.530 | 0.500 | |

| 2. Prior therapy | 0.158* | −0.023 | 0.112* | 0.402* | 0.307 | 0.462 | 0.214 | 0.411 | |

| 3. Perceived stigma | 0.028 | −0.046 | 0.310* | −0.032 | 3.260 | 1.375 | 3.200 | 1.337 | |

| 4. Personal stigma | 0.108* | 0.041 | 0.428* | 0.104* | 1.960 | 1.260 | 2.170 | 1.270 | |

| 5. Prof. help-seeking | 0.047 | 0.374* | −0.016 | 0.117* | 0.290 | 0.455 | 0.240 | 0.427 | |

Note. Data for Asian American participants are presented above the diagonal. Data for Asian international participants are presented below the diagonal. Gender is coded such that 1 = Men, 2 = Women. Prior therapy is coded such that 0 = no prior therapy, 1 = prior therapy. Professional help-seeking is coded such that 0 = no and 1 = yes.

p < .01.

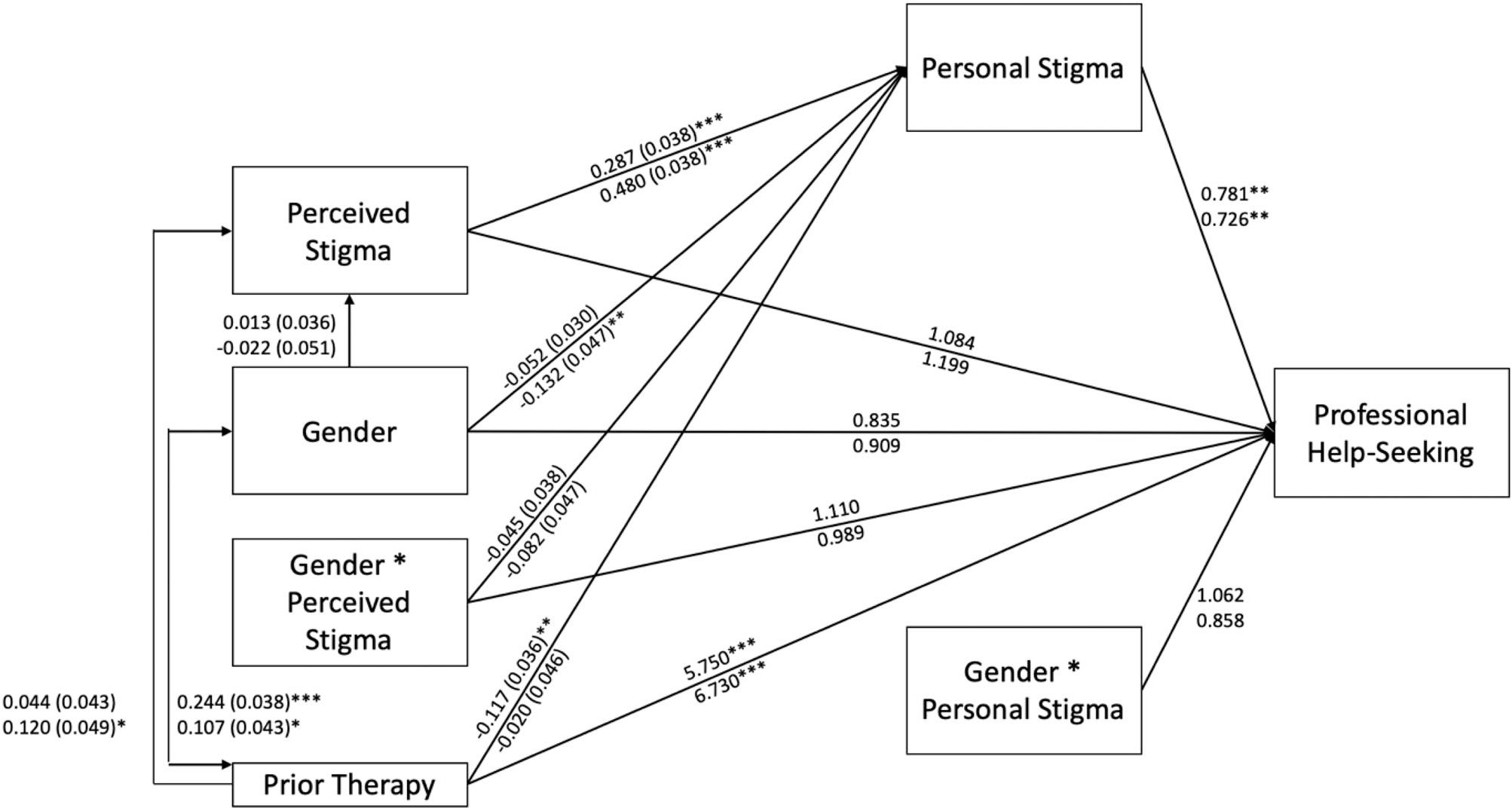

The model was programmed as displayed in Figure 1. Standardized path coefficients are presented in Table 2. In terms of the basic hypothesized relations among perceived stigma, personal stigma, and professional help-seeking attitudes, all paths were significant for both international and domestic students.

Figure 1.

Path model. Confidence intervals are presented in Table 2. Path coefficients for Asian American students are presented on the first row and for Asian International students on the second row. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 2.

Model path results.

| Path | Group | B (SE) | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Perceived stigma | −> | Personal stigma | Domestic | 0.287 (0.038) | (0.213, 0.361) |

| International | 0.480 (0.038) | (0.406, 0.555) | |||

| Gender | −> | Personal stigma | Domestic | −0.052 (0.030) | (−0.111, −0.002) |

| International | −0.132 (0.047) | (−0.224, −0.041) | |||

| Gender | −> | Perceived stigma | Domestic | 0.013 (0.036) | (−0.057, 0.084) |

| International | −0.022 (0.051) | (−0.123, 0.079) | |||

| Gender × Perceived stigma | −> | Personal stigma | Domestic | −0.045 (0.038) | (−0.119, 0.028) |

| International | −0.082 (0.047) | (−0.174, 0.010) | |||

| Prior therapy | −> | Perceived Stigma | Domestic | 0.044 (0.043) | (−0.040, 0.128) |

| International | 0.120 (0.049) | (0.024, 0.216) | |||

| Prior therapy | −> | Personal stigma | Domestic | −0.117 (0.036) | (−0.187, −0.046) |

| International | −0.020 (0.046) | (−0.111, 0.071) | |||

| Prior therapy | <−> | Gender | Domestic | 0.244 (0.038) | (0.170, 0.317) |

| International | 0.107 (0.043) | (0.023, 0.192) | |||

|

| |||||

| Path | Group | Odds ratio | 95% CI | ||

|

| |||||

| Perceived stigma | −> | Prof. Help-seeking | Domestic | 1.084 | (0.926, 1.269) |

| International | 1.199 | (0.983, 1.462) | |||

| Personal stigma | −> | Prof. Help-seeking | Domestic | 0.781 | (0.662, 0.921) |

| International | 0.726 | (0.568, 0.928) | |||

| Gender × Personal stigma | −> | Prof. Help-seeking | Domestic | 1.062 | (0.808, 1.396) |

| International | 0.858 | (0.533, 1.382) | |||

| Gender × Perceived stigma | −> | Prof. Help-seeking | Domestic | 1.110 | (0.860, 1.432) |

| International | 0.989 | (0.669, 1.462) | |||

| Gender | −> | Prof. Help-seeking | Domestic | 0.835 | (0.615, 1.134) |

| International | 0.909 | (0.572, 1.444) | |||

| Prior therapy | −> | Prof. Help-seeking | Domestic | 5.750 | (3.927, 8.418) |

| International | 6.730 | (3.979, 11.388) | |||

Note. Gender was coded such that 1 = Men, 2 = Women. Values are significant at p < .05 if the confidence interval does not cross 1, for odds ratios, and 0, for B coefficients.

In terms of gender, interactions involving gender were not significant. In terms of international status, differences emerged by international status for the relationship between perceived stigma and personal stigma. The relationship was positive for both groups, but much stronger for international students. One other group difference also emerged as significant; prior therapy and gender were more strongly associated for domestic than international students.

Hypothesis 1, that perceived stigma will be associated positively with personal stigma, was supported for Asian American and Asian international students. That is, among both groups, higher perceived stigma was associated with higher personal stigma about mental health help-seeking. Consistent with hypothesis H1a, there was also a significant difference between the strength of the relationships; Wald (1) = 12.722, p < .001; the relationship between perceived stigma and personal stigma was stronger for Asian international students, B = 0.48, SE = 0.04, than for Asian American students, B = 0.29, SE = 0.04.

Hypothesis 2, that personal stigma will be associated negatively with professional help-seeking intentions for both Asian American students and Asian international students, was also supported. That is, higher personal stigma was associated with lower odds of seeking a professional counselor for mental health issues. For Asian American students, for every one-unit increase in personal stigma, odds of seeing a psychologist dropped by 1.28 times, and for Asian international students, for every one-unit increase in personal stigma, odds of seeing a psychologist dropped by 1.38 times. The difference in strengths of the relationship was not significant, Wald (1) = 0.23, p = 0.63.

Hypothesis 3, that personal stigma will mediate the relationship between perceived stigma and help-seeking, was supported. Indirect effects were tested using 5,000 bootstrapped samples to build 95% confidence intervals. For Asian international students, the indirect effect was B = −0.043, SE = 0.015, 95% CI = −0.073, −0.012. For Asian American students, the indirect effect was B = −0.101, strength was significant different, Wald (1)SE = −0.038, 95% CI = −0.176, −0.027. The indirect effect = 7.46, p < .01, and was stronger in the Asian American group.

Hypothesis 4, that gender would be associated with perceived stigma, personal stigma, and help-seeking, was partially supported. Men reported higher personal stigma, but not perceived stigma, compared to women in both the domestic and international groups. After controlling for the influence of the other variables, gender was also not associated with professional help-seeking. Finally, we include exploratory assessment of differences in other paths in the model, by international status.

Discussion

With the increasing number of Asian American and Asian international students attending US colleges, there are multicultural considerations that need to be addressed for colleges to support these student populations. Stigma against mental health is prevalent in Asian cultures,18,20 and this stigma is associated with lower rates of mental health help-seeking in comparison to other ethnic groups.8–10,13 It is vital to understand the variables that influence help-seeking in Asian populations so that their mental health needs can be met in the context of college counseling centers.

Consistent with the hypotheses, the present study indicated that perceived stigma was positively associated with personal stigma and personal stigma was negatively associated with professional mental health help-seeking intentions for Asian American and Asian international students. These results replicated previous findings that supported the relationship between stigma and help-seeking in Asian communities.18,20 In these models, perceived stigma is internalized as personal stigma which is then associated with lower rates of help-seeking.18,20 That is, the perception of public attitudes toward mental health help-seeking influences an individual’s attitudes toward mental health help-seeking which then impacts their behavior.

The strength of the relationship between perceived stigma and personal stigma differed by international status, such that the relationship was stronger for international students. Further, the indirect effect, or mediation, differed in strength by international status. These results suggest that perceived and personal stigma are important to understanding propensity for professional help-seeking among Asian American and Asian international students, and that these stigmas may be particular barriers for Asian international students in seeking psychological help.

The relationship between international status and lower rates of help-seeking was also consistent with previous findings.8,18,20 This relationship may reflect different cultural attitudes in seeking professional mental health services. Asian Americans may be more likely to have acculturated to American values which may lead to more accepting attitudes toward mental health help-seeking compared to Asian international students. Thus, international status may play a prominent role in the relationship between mental health stigma and professional help-seeking in the Asian population. These findings demonstrate the need to address the Asian international student population, who may experience more barriers to mental health help-seeking.

Implications

With an increasing number of Asian international students attending US colleges, it is pertinent that the mental health needs of this group are being met. The need to meet mental health concerns of Asian international students has become a more pressing concern with the coronavirus pandemic, as international students may face additional stressors that can negatively impact their mental well-being. Thousands of international students, most of them from Asian countries are residing in the US with uncertainty regarding their residency status.30 Colleges have a responsibility to take care of international students who pay fees for student services. Services for Asian international students are especially relevant while international students face challenges such as modifications to the US immigration system that leave international students with anxiety and uncertainty regarding their ability to finish their education in the US or to stay in the US on temporary work visas following graduation.30–32 Colleges should be aware that with these additional concerns, there are unique needs for Asian American students and international Asian students. Outreach to international Asian students that provides resources to support the challenges that they are facing may be a crucial step in ensuring that this segment of the college counseling center stakeholders is being supported. In order to accomplish the goal of serving the mental health of all students, colleges need to be aware of potential obstacles to professional help-seeking in international Asian student populations that this study has addressed.

Counseling centers need to implement direct outreach to ensure that they are working to serve the entire student body. This would involve efforts to reduce barriers to help-seeking in the Asian student population. Some of these barriers may involve Asian cultural values. There is an inverse relationship between adherence to Asian values and attitudes toward professional mental health help-seeking.7 Asian populations may be more reluctant to seek counseling services due to the learned social implications of professional help-seeking that could harm their relationships and social standing.13 Due to this avoidance, outreach may involve developing ties with Asian communities on campus such as Asian student associations and international student groups. Receiving culturally sensitive information about counseling services within their community may serve to reduce perceived stigma against help-seeking. Also, primary health care services can serve as a less stigmatized referral source for mental health services that are provided on campus.

Mental health marketing that is sensitive to ethnicity can also be used to improve attitudes toward help-seeking. Counseling brochures that were developed with an understanding of the psychology of men and masculinity resulted in improved attitudes and reduced self-stigma for men with depression.33 Brochures that are sensitive to Asian values may result in more positive attitudes toward counseling. These brochures could include photos of Asian people in the counseling setting and incorporate language and facts that are more targeted to appealing to the Asian population (e.g., solution focused methods of treatment, confidentiality, facts and figures of the effectiveness of counseling, destigmatizing mental health help-seeking). These brochures could be distributed to Asian student organizations to provide outreach within their community. Future research should be conducted to examine whether culture-sensitive mental health marketing can be utilized as an effective intervention to increase help-seeking intentions in the Asian population.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting these results. First, the cross-sectional data collected in this study cannot be used to establish a causal relationship between stigma and help-seeking. Second, the data did not distinguish between country of origin. There may be important nuances in the relationship between stigma and help-seeking and between Asian populations due to differences in cultural values. Third, there was no assessment of generational status which may influence help-seeking in Asian populations.8 Additionally, the measures for perceived stigma, personal stigma, and mental health help-seeking were single item measures that may be limited in their ability to capture the scope of these variables.

In summary, this study found that international status was associated with differences in the relationship between perceived stigma and personal stigma. Consistent with previous findings, perceived stigma was positively associated with personal stigma for both Asian international students and Asian American students, with the relationship being stronger for international students. Personal stigma was negatively associated with mental health help-seeking for both Asian international students and Asian American students. Personal stigma mediated the role between perceived stigma and help-seeking. These results speak to the need for outreach efforts on college campuses to reduce the stigma surrounding mental health as well as promote college counseling services and resources to meet the mental health needs of their Asian student population. More research needs to be completed to understand the effective methods of intervention and outreach to better serve Asian students.

Funding

No funding was used to support this research and/or the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The authors confirm that the research presented from the Healthy Minds Study (HMS) in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of the United States of America and received approval from the Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Michigan.

References

- 1.Institute of International Education. All places of origin. 2019. Available at: https://opendoorsdata.org/data/international-students/all-places-of-origin/. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- 2.Briggs P, Ammigan R. A collaborative programming and outreach model for international student support offices. J Int Students. 2017;7(4):1080–1095. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1035969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFarland J, Hussar B, Zhang J. The Condition of Education 2019. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chavajay P, Skowronek J. Aspects of acculturation stress among international students attending a university in the USA. Psychol Rep. 2008;103(3):827–835. doi: 10.2466/PR0.103.7.827-835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice KG, Choi CC, Zhang Y, et al. International student perspectives on graduate advising relationships. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(3):376–391. doi: 10.1037/a0015905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry JW, Kim U, Minde T, et al. Comparative studies of acculturative stress. Int Migr Rev. 1987;21(3):491–511. doi: 10.2307/2546607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shea M, Yeh C. Asian American students’ cultural values, stigma, and relational self-construal: correlates of attitudes toward professional help seeking. J Ment Health Couns. 2008;30(2):157–172. doi: 10.17744/mehc.30.2.g662g5l2r1352198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, et al. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung FK, Snowden LR. Community mental health and ethnic minority populations. Community Ment Health J. 1990;26(3):277–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00752778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David EJR. Cultural mistrust and mental health help-seeking attitudes among Filipino Americans. Asian Am J Psychol. 2010;1(1):57–66. doi: 10.1037/a0018814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SX, Mak WW. Seeking professional help: Etiology beliefs about mental illness across cultures. J Couns Psychol. 2008;55(4):442–450. doi: 10.1037/a0012898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon E, Jepsen DA. Expectations of and attitudes toward counseling: a comparison of Asian international and U.S. graduate students. Int J Adv Counselling. 2008;30(2):116–127. doi: 10.1007/s10447-008-9050-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mojaverian T, Hashimoto T, Kim HS. Cultural differences in professional help seeking: a comparison of Japan and the U.S. Front Psychol. 2013;3:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrigan PW, Druss BG, Perlick DA. The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2014;15(2):37–70. doi: 10.1177/1529100614531398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper A, Corrigan P, Watson A. Mental illness stigma and care seeking. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191(5):339–341. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200305000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):522–541. doi: 10.1177/1077558709335173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogel DL, Wade NG, Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53(3):325–337. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogel DL, Strass HA, Heath PJ, et al. Stigma of seeking psychological services: examining college students across ten countries/regions. Couns Psychol. 2017;45(2):170–192. doi: 10.1177/0011000016671411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am Psychol. 2003;58(1):5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrews G, Issakidis C, Carter G. Shortfall in mental health service utilisation. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179(5):417–425. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Möller-Leimkühler AM. Barriers to help-seeking by men: a review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. J Affect Disord. 2002;71(1–3):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parent MC, Hammer JH, Bradstreet TC, Schwartz EN, Jobe T. Men’s mental health help-seeking behaviors: an intersectional analysis. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(1):64–73. doi: 10.1177/1557988315625776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healthy Minds Network. The healthy minds study. 2019. Available at: www.healthymindsnetwork.org/research/hms. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- 26.Shalka TR, Leal CC. Sense of belonging for college students with PTSD: the role of safety, stigma, and campus climate. J Am Coll Health. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2020.1762608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiker DA, Hammer JH. A model of intention to provide mental health first aid in college students. J Ment Health. In press. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2019.1644493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dschaak ZA, Spiker DA, Berney EC, Miller ME, Hammer JH. Collegian help seeking: the role of self-compassion and self-coldness. J Ment Health. In press. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2019.1677873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mushonga DR, Fedina L, Bessaha ML. College student perceptions of institutional responses to sexual assault reporting and general help-seeking intentions. J Am Coll Health. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1705827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alvarez P, Shoichet C. International students may need to leave US if their universities transition to online-only learning. Cable News Network. July 7, 2020. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/06/politics/international-college-students-ice-online-learning/index.html. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 31.Dickerson C. ‘My world is shattering’: Foreign students stranded by coronavirus. New York Times. April 25, 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/25/us/coronavirus-international-foreign-students-universities.html. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 32.Daiya K. The current plight of international students. Inside Higher Ed. June 16, 2020. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/06/16/colleges-need-help-international-students-now-opinion. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 33.Hammer JH, Vogel DL. Men’s help seeking for depression: the efficacy of a male-sensitive brochure about counseling. Couns Psychol. 2010;38(2):296–313. doi: 10.1177/0011000009351937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]