Abstract

Despite increased recognition of disparities in youth mental health, racial/ethnic disparities in mental health burden and in mental health service use persist. This phenomenon suggests that research documenting disparities alone has not led to extensive action in practice settings in order to significantly reduce disparities. In this commentary, we present a framework to actively target this research-to-practice gap by describing the development of a resource titled, “Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Racial and Ethnic Minority Youth—A Guide for Practitioners.” We begin by presenting social justice as the impetus for eliminating disparities and then reviewing current knowledge and efforts aimed at reducing disparities. Subsequently, we describe knowledge transfer frameworks and goals guiding our work. Finally, we detail the steps taken in our approach to translation and implications for subsequent dissemination of this guide. Translation focused on evidence-based information on (a) mechanisms that contribute to disparities, and (b) strategies for providers to address disparities in their work. We reflect on the framework guiding our translation to offer future directions for others interested in bridging research and action.

Keywords: mental health disparities, knowledge translation, racial/ethnic minority youth

There has been a significant increase in research describing disparities in children’s mental health since the 2001 seminal Surgeon General’s report, Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2001), that documented striking racial/ethnic disparities in mental health services. Health disparities are generally defined as differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and burden of diseases that are disproportionately observed among racial/ethnic minorities, in comparison with European Americans/Whites (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2000). According to the Office of Minority Health (2011), resultant poorer outcomes are significantly associated with historically and structurally shaped socioeconomic and environmental disadvantages (Office of Minority Health, 2011). Youth from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds, specifically African American, Native American, Asian American, and Hispanic/Latinx American, not only experience disproportionate rates of mental health burden, they also experience persistent and troubling disparities at every level of mental health care, including service utilization, diagnostic practices, and treatment engagement and outcomes (Eaton et al., 2008; Holden et al., 2014; President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003). In this commentary, we briefly present the research evidence on mental health burden and limited access to mental health services that are disproportionate among racial/ethnic minority youth, as a foundation for our translation of knowledge to reach mental health practitioners providing services to these youth.

Ongoing disparities in burden include high rates of major depression and externalizing behaviors along with greater rates of school failure, poorer peer relationships, and more family challenges among racial/ethnic minority youth with mental health conditions (Ezpeleta, Keeler, Erkanli, Costello, & Angold, 2001; Hinojosa et al., 2012). Further, the persistent disparities in mental health care consist of poorer access to mental health services for racial/ethnic minority youth, as well as inferior services when care is received (Alegría, Vallas, & Pumariega, 2010). Shortages of accessible community-based mental health services and racial/ethnic minority providers, insufficient insurance coverage,; and provider and organizational barriers, such as a lack of cultural competence have been postulated as factors that contribute to and maintain these disparities (American Psychological Association [APA], n.d.; Hoge et al., 2007; Holden et al., 2014; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices, 2016). Limited cultural competence and unconscious racial/ethnic biases among the field’s mostly European American/White health providers has profoundly tragic and disparate consequences (Hoge et al., 2007). According to the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (2003), mental health providers’ frequent tendency to “misunderstand and misinterpret” the behaviors of racial/ethnic minorities results in high rates of misdiagnosis and undertreatment of mental health conditions. Consequently, increased socioemotional challenges, and interpersonal and academic failures contribute to racial/ethnic minorities’ overinvolvement in the criminal and juvenile justice systems. In line with the negative influence of these structural, provider, and organizational barriers on disparities, several federal agencies have implemented policies and programs to address them.

Social Justice and the Elimination of Racial/Ethnic Disparities

The elimination of racial/ethnic minority youth mental health disparities aligns closely with the goals of social justice, which include the equitable distribution of resources, physical and psychological safety and security of all members of society, and empowerment of individuals and communities (Bell, 1997; Ratts & Hutchins, 2009). Within the context of mental health services, a social justice approach specifically aims to eliminate disparities and encourages providers to consider multiple levels of influence (e.g., individual, family, systemic) when working with clients (Sue & Sue, 2012). Additionally, a social justice approach to services expands the role of providers beyond direct service delivery to individuals and encourages actions that can effect social change. Some of these actions include advocacy, prevention, activism, and community collaboration (Sue & Sue, 2012).

A catalyst for efforts aimed at eliminating disparities is the central value of social justice within psychology. For example, within the APA the mission, values, goals, and strategic plan highlight the importance of psychologists addressing social issues (Vasquez, 2012), and various initiatives within the organization are guided by this commitment. One such initiative is the Working Group on Health Disparities in Boys and Men, which was launched in 2013 by the Public Interest Directorate and the National Steering Committee on Health Disparities of APA. The Working Group has advocated for social issues affecting marginalized boys and men, such as trauma and violence, addiction and substance use, and stress (APA, 2016). Similarly, APA divisions, such as the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, have infused social justice into advocacy and policy, research, teaching, and practice. These actions codify the central role that social justice can play within psychology. More importantly, such movement toward a social justice perspective encourages psychologists not to “blame the victim” with a myopic emphasis on individual responsibility and control, but to take an action-oriented approach to eliminating disparities. Thus, a social justice framework coupled with a focus on translation and dissemination of knowledge may prove useful in turning existing research into actions designed to eliminate disparities (Sue & Sue, 2012).

Existing Efforts to Reduce Mental Health Disparities

In addition to psychology’s commitment to social justice through its mission, organizational initiatives, and divisional advocacy, a number of recent national efforts with potential to reduce the alarming disparities in mental health burden and services have been implemented. For example, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; 2010) allows opportunities for improved mental health care access by providing expanded insurance coverage for mental health conditions, and supporting the integration of mental health with physical health services (Holden et al., 2014; SAMHSA, 2016). To further support the ACA, SAMHSA created the Office of Behavioral Health Equity to ensure that reducing disparities in health and improving the quality of health care services was a goal in the implementation of the ACA (Wahowiak, 2015).

Another approach implemented by federal agencies to address health disparities has been to enhance the skills of the clinical workforce. For example, SAMHSA funded the APA Minority Fellowship Program to train mental health practitioners to reduce disparities in mental health care by increasing the number of culturally competent providers who deliver services (Wahowiak, 2015). In another example, the National Network to Eliminate Disparities in Behavioral Health partnered with the National Alliance of Multi-Ethnic Behavioral Health Associations to disseminate evidence-based science and deliver training to community-based organizations that work with racial/ethnic minority populations. Moreover, the APA has published guidelines for psychology and mental health counseling graduate programs to deliver training in multicultural competency (Sue, Zane, Nagayama Hall, & Berger, 2009).

Unfortunately, despite the vast research on disparities and the strategies employed to promote mental health equity, disparities in mental health care and burden remain for racial/ethnic minority youth. Reasons for the ongoing disparities are complex and multidimensional, and include social and structural barriers to wellbeing, including policies that place undue burden and limit access to quality services. Yet one important reason is the focus of research on producing knowledge, and less attention focused on the translation of knowledge. In a review by Brownson, Kreuter, Arrington, and True (2006), only 20% of research focuses on translating knowledge to community practice, where that knowledge would be beneficial. Furthermore, research translation has lagged, with only 14% of original research making an impact on practice, and with a time lag of 17 years. Bridging research and practice as they relate to racial/ethnic disparities and speeding up the translation of knowledge are critical steps to achieving health equity.

Reducing Disparities in Mental Health via Knowledge Translation

This commentary describes the development of a practitioner guide to address disparities in the utilization of child and adolescent mental health services. Although our social justice foundation gives meaning and purpose to reducing disparities in mental health, our direction comes from the scientific evidence that comprises the effective translation of knowledge. While defined and discussed separately, for the purpose of this commentary, the constructs are perceived as having an interactive nature—social justice emphasizing intent and action, and knowledge transfer frameworks emphasizing a specific approach to action. Ultimately, our goal is to demonstrate how such interaction can result in the successful development of resources that can assist providers in eliminating disparities.

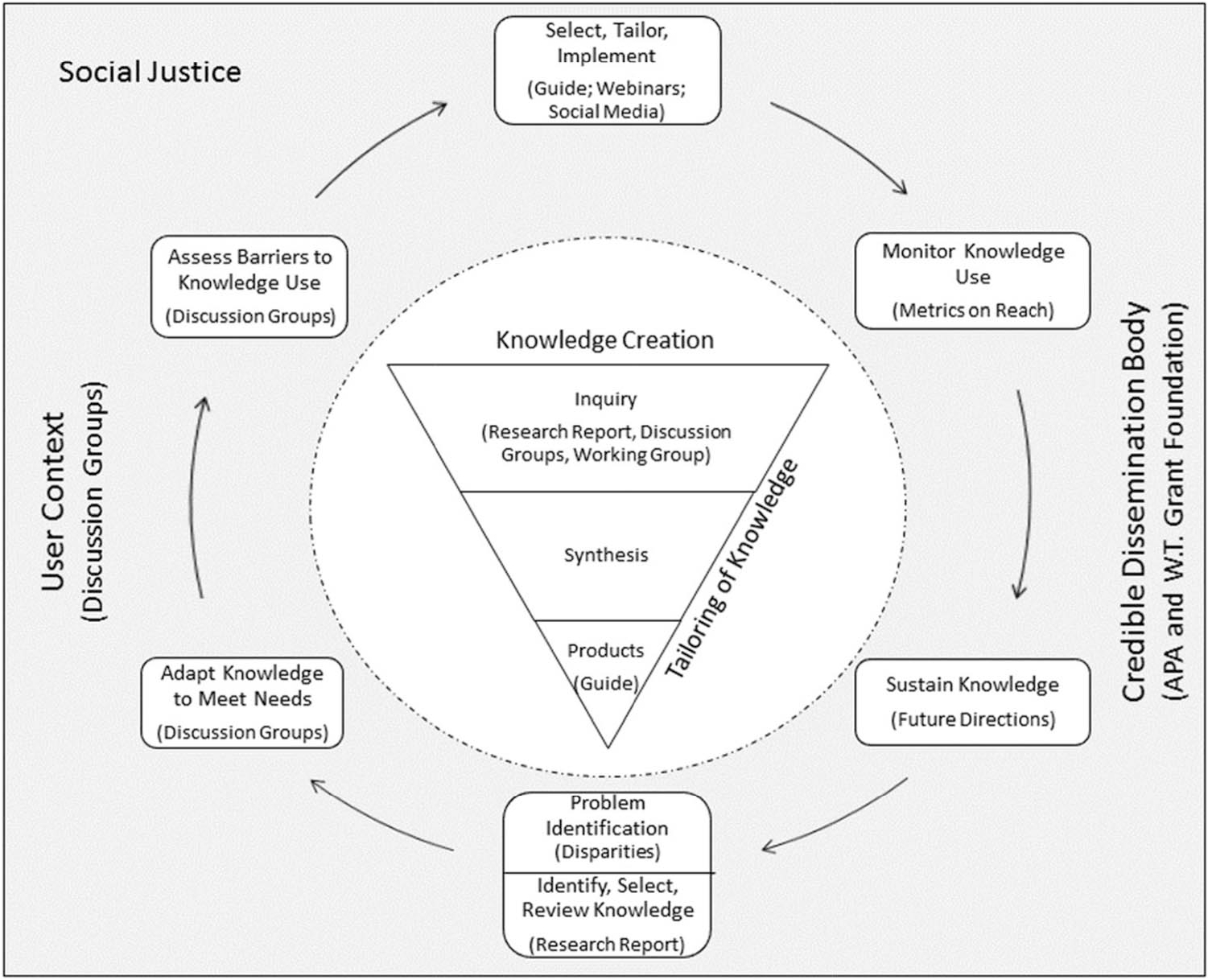

Knowledge translation is defined as the “synthesis, exchange, and application of knowledge by relevant stakeholders” (World Health Organization, 2005), with an emphasis on accelerating our ability to improve health and health systems. In this manner, models for the dissemination of knowledge explicitly focus on ways of maximizing the public health impact of efforts by attending to its eventual dissemination even at the stage of knowledge creation. The approach to knowledge translation described in this commentary is consistent with the knowledge-to-action process framework (KTA; Graham et al., 2006), which highlights interactive relationships between two relevant phases: (a) knowledge creation, and (b) an action cycle (Figure 1). Within the knowledge creation phase, knowledge producers (e.g., researchers, content experts) and knowledge users (e.g., practitioners) collaborate on creating and tailoring relevant knowledge by building a knowledge base (knowledge inquiry), synthesizing relevant knowledge, and then creating tools and products emerging directly from this knowledge creation process. Working in parallel, the action phase involves a series of reciprocal activities needed for knowledge application. As seen in Figure 1, action may begin with the identification and clarification of the problem, the adaptation of knowledge to a specific context, an assessment and understanding of barriers to the utilization of knowledge, and the tailoring and implementation of specific interventions, followed by efforts to monitor use and evaluate outcomes in order to sustain use of knowledge. In describing our knowledge translation efforts, we specifically focus on our process for knowledge creation in this commentary.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model informing the development and dissemination of the Practitioner Guide. From “Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map?,” by I. D. Graham, J. Logan, M. B. Harrison, S. E. Straus, J. Tetroe, W. Caswell, and N. Robinson, 2006, The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26, p. 19. Copyright 2006 by Wiley; Now by Wolters Kluwer. Adapted with permission.

While the KTA framework served as the primary model for knowledge translation, we also incorporated the understanding-user-context framework (UUC; Jacobson, Butterill, & Goering, 2003), given our strong desire to understand and consider the context of the intended users (e.g., providers). Consideration of the UUC framework ensured that we gathered information about the needs and context of users so the knowledge translation goals and methods fit within the individual and organizational context of providers. Furthermore, given our collaboration with the APA and the William T. Grant Foundation, we also considered the broad framework proposed by the coordinated implementation model (CIM; Lomas, 1993). Specifically, the CIM framework highlights the potential role of credible dissemination bodies, like our collaborators, in creating an environment that supports the coordinated translation of knowledge by relevant stakeholder groups. Thus, KTA provided a model to guide knowledge translation activities while the UUC and the CIM frameworks ensured a focus on the local context of users and the broader professional context, respectively.

Development of a Practitioner Guide

Guided by a social justice foundation and the models of knowledge translation described above, we developed a guide for psychologists and other mental health providers titled, “Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Racial and Ethnic Minority Youth—A Guide for Practitioners.” In this commentary, we describe the process we used to translate evidence-based information from a research report on (a) mechanisms that contribute to disparities, and (b) strategies for providers to address disparities in their clinical work. Through these efforts, we hope to increase practitioner awareness about mental health disparities in children and adolescents and to highlight environmental factors contributing to these disparities. We also aim to inform the development of user-friendly resources designed to bridge science and practice while supporting practitioner competence and confidence in taking concrete action to address disparities for the benefit of their young racial/ethnic minority clients. It is our hope that our process for translating evidence-based information on racial/ethnic disparities in child mental health can serve as a model for others who are interested in conducting similar work.

Initiation of the Project

The project was initiated by members of the APA Committee on Children, Youth and Families (CYF) under the leadership of the first author, who was the chair of the committee in 2015. The CYF is a standing committee in the Office of Public Interest at the APA and interacts with and makes recommendations to the various parts of the APA’s governing structure, to the APA’s membership, and to relevant APA divisions and other groups. During a CYF meeting, the first author proposed a new initiative to translate and disseminate for mental health practitioners, information from a research report on children’s mental health disparities titled “Disparities in Child and Adolescent Mental Health and Mental Health Services” (Alegría, Green, McLaughlin, & Loder,2015). This report, published by the William T. Grant Foundation, provided an updated overview of mental health disparities among racial/ethnic minority youth, mechanisms underlying such disparities, and recommendations for future research. The report was published to kick-start a new initiative of the William T. Grant Foundation that focused on programs, policies, and practices to reduced is parities among under served youth. The report can be found at http://wtgrantfoundation.org/resource/disparities-in-child-and-adolescent-mentalhealth-and-mentalhealth-services-in-the-u-s

The CYF committee reviewed sample practitioner guides that had been previously published by the APA and agreed to consult with the president of the William T. Grant Foundation and first author of the research report published by the foundation to determine their level of support, interest, and involvement in the project. Additionally, a subcommittee of four CYF members was formed to pursue the project. Guided by the CIM (Lomas, 1993) mentioned above, involving these key stakeholders, including the funding organization, researchers, and national practice/research organizations, not only increased the resources available to plan and carry out our translation efforts, it also maximized the intended product’s credibility and visibility, which is valued by practitioners looking for professional resources to inform their practice.

After receiving support and interest from these key players, we submitted a plan to the William T. Grant Foundation to obtain funding for the project. Specifically, we requested the William T. Grant Foundation provide funding for the purposes of: (a) translating the research information on disparities in children’s mental health into a practitioner guide using information obtained from discussion groups conducted with psychologists and the expertise of a workgroup of psychologists, and (b) disseminating information on disparities via multiple channels, including online and print resources, social media, professional webinars, and short video clips. We estimated that one third of the costs would support the first purpose of translation, and the focus of this commentary (e.g., time of a working group and a graduate assistant to write the guide for practitioners), while the largest portion of funds would support the second purpose of dissemination of the guide (e.g., print products, webinars, and short video clips). The project received funding from the foundation, and the funds were awarded to the APA’s Office on Children, Youth and Families. Below we detail the translation of the research report into a practitioner guide.

Translation of Research Information on Disparities in Children’s Mental Health

As previously mentioned, the KTA (Graham et al., 2006) framework was helpful in guiding the overall process of translation, while the UUC (Jacobson et al., 2003) framework was helpful in defining specific considerations in the knowledge creation phase of the guide (i.e., translation). In the KTA’s first phase of knowledge creation we followed three steps: (a) hosting discussion groups with psychologists to understand our intended user group and its perspective on disparities, as well as to inform the content to be included from the research report and format of the practitioner guide; (b) assembling a working group made up of psychologists with expertise in mental health disparities to solidify content for the practitioner guide; and (c) designing the guide.

Conducting discussion groups with psychologists.

For the purpose of understanding the user group (i.e., psychologists) and defining the content and format of the practitioner guide from the perspective of its potential users, we conducted two discussion groups with over 25 psychologists. Consistent with the UUC framework (Jacobson et al., 2003), we structured questions (Table 1) to answer who the user group is, how the user group understands mental health disparities among racial/ethnic minority youth, and how aware the user group is of disparities in their work. These questions provided valuable information about (a) what psychologists want to know about mental health disparities; (b) the types of disparities facing their racial/ethnic minority youth clients; (c) their use of scientific knowledge about mental health disparities, and access to this knowledge; and (d) how psychologists deal with these disparities in their practice. Importantly, this type of information gathering allowed us to condense the literature on mental health disparities among racial/ethnic minority youth published in the research report so the information included in the guide would meet the needs of practicing psychologists (Graham et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Discussion Group Questions

| 1. How do clinical practitioners understand mental health disparities (e.g., inequality vs. disparities)? (a) What concepts come to mind when they hear the term “mental health disparities”? 2. How relevant are mental health disparities to practitioners’ work with racial/ethnic minority children, youth, and families? (a) How do disparities affect practitioners’ work with these clients? (b) What challenges do they face when working with these clients? 3. What are some strategies that have worked for practitioners in addressing mental health disparities? 4. What are major gaps in general knowledge related to child mental health disparities? (a) What would practitioners want to know? 5. What are major gaps in practice related to addressing child mental health disparities? (a) What would help practitioners better address disparities? 6. What should be the format of the “Reference Guide for Practitioners?” (a) Length? (b) Use of infographics (c) Use of vignettes (d) Use of bullet points vs. narrative 7. What channels should be used to disseminate the information for wide reach? (a) What would be the most convenient way to access the information from the guide? 8. How can the guide be used to expand practitioners’ role in addressing mental health disparities? That is, how can it be used for advocacy, collaboration, and policy? |

In our discussion groups, we were also interested in understanding psychologists’ preferences for the format and dissemination of the guide. Specifically, we asked questions about the format and dissemination to enhance uptake and adoption: (a) ideal length of the guide, (b) supplemental products (e.g., webinar, video clips), and (c) framing of the information. For example, the original William T. Grant Foundation research report highlighted that racial/ethnic minority youth experience disproportionate rates of risks for poor mental health relative to their European American/White peers. However, policy think tanks suggest that message framing avoid focusing on disparities in health for a specific group because this strategy can risk reinforcing “otherism.” That is, rather than calling attention to the disadvantages of a particular racial/ethnic minority group in a specific area, think tanks suggest using communication framing that captures values, experiences, and characteristics, such as justice, safety, and resilience, that all community members can relate to.1 Our goal, consistent with user domains of the UUC (Jacobson et al., 2003) and with knowledge inquiry of the KTA (Graham et al., 2006) frameworks, was to explore users’ acceptability and preferences for various forms of message framing and dissemination strategies for the guide.

We used various sampling strategies and venues for both discussion groups. The first group took place with a purposive sample of psychologists at the 2015 annual convention of the APA in Toronto, Canada. The purpose of this sample was to reach practicing psychologists who represented geographic regions across the country and who worked in different practice settings. Psychologists were recruited via e-mail advertisements sent by the CYF Office to APA division and committee listservs (Figure 2). This discussion group took place in a private hotel suite intended for APA events, and refreshments were served. For the second discussion group, we recruited a convenience sample of psychologists in the fall of 2015 during the APA governance consolidated meeting in Washington, DC. These psychologists were recruited through internal advertisement to all APA practice committees attending the consolidated meeting. The forum took place over the lunch hour in one of the meeting rooms of the consolidated meetings hotel. Psychologists in these contexts were targeted because they constituted a ready audience of predominantly practitioners with interests in public service. The first and the last author facilitated the group discussions.

Figure 2.

Invitation to participate in the discussion group. See the online article for the color version of this figure.

Information obtained from discussion groups.

Participants ranged from psychologists who were dedicated solely to practice, to those who were involved in a combination of research and practice. Most participants across the two groups worked in urban areas across the country although a small number in the second discussion group practiced in rural areas.

Consistent with the KTA framework, the CYF subcommittee members produced written notes of the perspectives that were shared during the discussion groups, discussed the perspectives, and arrived at a final list of themes related to content (2 themes) and framing (5 themes) of the guide. Content themes overall highlighted that psychologists are aware of disparities but often experience barriers to address these in their work. First, psychologists discussed the service system-level barriers that negatively affect their work with racial/ethnic minority youth, namely restrictive organizational policies regarding no-shows/termination, lack of routine or required assessment of social determinants of health, and limited collaboration with various agencies that can address social determinants of health (e.g., nutrition programs). Psychologists offered strategies that could address system-level barriers, including providing mental health services within schools, implementing routine assessment of social determinants of health, and careful attention to determining whether social determinants, health behaviors, or both contribute to client outcomes.

Second, psychologists in the discussion groups indicated barriers at the level of the provider, most notably gaps in knowledge about the severity of mental health disparities and the range of potential solutions for addressing them. They requested the guide include information about how to address disparities through multiple roles, including the clinical encounter (e.g., sensitivity to clients’ background) but extending to other contexts (e.g., advocacy, prevention, community collaboration).

With respect to framing, psychologists first suggested that the guide balance a focus on disparities among racial/ethnic minority youth with discussion of the social determinants that affect these youth. This balance was deemed important to prevent the guide from blaming or placing the burden of change on youth. Second, discussion group participants acknowledged that although calling attention to the needs, values, and experiences of all community members may be effective, that messaging in such general terms runs the risk of ignoring underserved communities and of skirting around social justice issues. Third, they also discussed the importance of acknowledging that other aspects of an individual’s identity and their environment (e.g., sexual identity and disability status) may interact with race/ethnicity to influence outcomes for youth. Fourth, the discussion group participants recommended that the guide be disseminated through a variety of channels, including print and accessibility through the Internet. Finally, they also noted the need to expand the reach of the guide beyond psychologists to other mental health providers, including social work and psychiatry.

Establishment of a working group of psychologists.

After receiving direction from psychologists on how to frame and format the guide through discussion groups, the CYF subcommittee moved to the action cycle phase in the KTA framework, to assemble a working group of psychologist researchers and practitioners with extensive experience conducting research with (as evidenced by grant funding or publication record) or providing psychological services to racial/ethnic minority children, youth, and families. The working group was formed by soliciting nominations (a letter of interest and their CV) through a call for nominations that was disseminated via e-mail among divisions of APA that address minorities, youth, children, and families. We received 19 nominations, of which two were students and, therefore, ineligible, given they were not likely to have extensive experience engaging in independent research or practice. The CYF subcommittee reviewed and ranked nominees based on a balance of research and/or practice experience with racial/ethnic minority youth, and interests in the area of disparities. The final working group was composed of four members and the CYF subcommittee to represent expertise across specific racial/ethnic minority groups, including African American/Black and Hispanic American/Latinx. With the collective expertise of the working group, we developed the reference guide for practitioners.

Development of reference guide for practitioners.

The working group held four telephone meetings to discuss the content and format of the new practitioner guide. The first author led these meetings and requested input from the working group about the best strategy to translate and disseminate the guide with the research evidence contained in the report published by the William T. Grant Foundation. After identifying and selecting the knowledge for the guide (see bottom of action phase in Figure 1), the first author then worked with an assistant from the Office of Children, Youth and Families to summarize the information from the William T. Grant Foundation research report for the practitioner guide. Adapting the guide to the preferences stated in discussion groups, the working group developed new content for addressing mental health disparities in practice. This new content provided recommendations for addressing disparities in their clinical encounters with children and youth, improving access to and quality of care, and expanding practitioner roles to include advocacy, collaboration, and consultation. This new section underwent an iterative process of revisions based on the input from the working group. Consistent with the action cycle of the KTA framework, specific recommendations centered around which knowledge to prioritize and adapt, how to simplify uptake of knowledge, and which interventions to include in the guide, which were not part of the original research report and that needed to be pulled from the literature (Table 2). The final guide included a summary of knowledge on disparities contained in the research report, but had a new section on interventions, and excluded knowledge from the research report that proposed implications for future research.

Table 2.

Summary of Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Racial and Ethnic Minority Youth—A Guide for Practitioners

| 1. Mechanisms underlying disparities in mental health outcomes among racial and ethnic minority youth | ||

| Socioeconomic status Exposure to childhood adversities |

Neighborhood-level stressors Family structure |

Practitioners’ implicit bias Practitioners’ limited cultural competence |

|

| ||

| 2. Protective mechanisms underlying youths’ mental health outcomes | ||

| Positive home and school environments Stable parental mental health |

High levels of social support and religious and community involvement | Positive racial and ethnic identity |

|

| ||

| 3. Determinants of mental health care use for racial and ethnic minority youth | ||

| Individual factors Practical barriers |

Attitudes and beliefs Systemic barriers |

Type of mental health problem Role of adult gatekeepers |

|

| ||

| 4. Role of practitioners within clinical encounter | ||

| Culturally grounded clinical practice Cultural humility Reflection on worldview Multicultural clinical guidelines Cultural competence Reflection on worldview Multicultural clinical guidelines Cultural competence |

Consideration of individual’s context Ecomaps Culturagram Consideration of intersecting identities Client engagement Establishing a receptive environment Encouraging participation school/community forums |

Practice motivational interviewing Assessing barriers to treatment Fostering a strong, culturally sensitive alliance Explanation and education about treatment processes |

|

| ||

| 5. Role of practitioners outside of the clinical encounter | ||

| Organizational self-assessment and change | Outreach, collaboration, and engagement with the community | |

Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Racial and Ethnic Minority Youth-A Guide for Practitioners

“Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Racial and Ethnic Minority Youth” (American Psychological Association, Working Group for Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Youth Mental Health, 2017) is a 20-page guide for practitioners that aims to increase understanding of the mental health needs of racial/ethnic minority youth and strategies to address them. The guide can be found on the Children Youth and Families page of the APA website (http://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/mental-health-needs.pdf). The guide is structured around five major sections that pertain to recognizing and addressing mental health disparities among racial/ethnic minority youth (see Table 2). The sections consist of mechanisms leading to disparities in mental health outcomes among racial/ethnic minority youth, factors that protect against negative mental health outcomes, determinants of mental health care use, strategies that practitioners can use within their clinical practice, and potential roles of practitioners to address disparities outside of the clinical encounter.

Five primary mechanisms that underlie disparities in mental health outcomes are outlined in the first section of the guide: (a) socioeconomic status, (b) exposure to childhood adversities, (c) neighborhood-level stressors, (d) family structure, and (e) practitioner’s implicit biases and limited cultural competencies. Each mechanism is briefly defined and then the role that each contributes to disparities in mental health among racial and ethnic minorities is described. The second section describes factors that promote positive mental health for minority youth, including (a) positive home and school environments, (b) stable parental mental health, (c) high levels of social support and religious and community involvement, and (d) positive racial and ethnic identity. The identification and elucidation of these risk and protective factors highlights the social-ecological context of many racial/ethnic minority youth, while considering the interplay of individual, family, community, social, cultural, and political factors in shaping mental health outcomes.

The third section on mental health care utilization briefly reviews the multiple factors that lead to relatively lower service use among racial/ethnic minority youth. These factors included individual-, practical-, attitudinal-, and systemic-level barriers that interact with each other to influence utilization. For example, the section identified a lack of insurance coverage and difficulties with transportation as practical barriers to service use. Further, a lack of linguistically appropriate services in many communities was listed as a systemic barrier for racial/ethnic minority families.

The fourth section, focused on the role of practitioners within the clinical encounter, outlines practical steps for understanding and addressing the multiple barriers that contribute to disparities in mental health services and outcomes for racial/ethnic minority youth. The strategies include addressing one’s own attitudes and beliefs, promoting engagement in treatment by addressing families’ practical and attitudinal barriers, and adopting a social ecological framework. Finally, the section on the role of practitioners outside of the clinical encounter identifies ways for addressing organizational barriers and promoting access to treatment by collaborating with other community organizations. Such strategies included conducting an organizational assessment to identify organizational-level barriers, as well as educating, training, and establishing long-term relationships with community members.

Implications and Future Directions

As in the last two steps within the action cycle of the KTA framework (Graham et al., 2006), we are currently moving toward disseminating the practitioner guide and are monitoring its use. First, dissemination is intended to (a) raise awareness of racial/ethnic minority youth mental health disparities among a diverse group of service stakeholders, (b) increase access to evidence-based knowledge and reach more practitioners, and (c) model and reinforce culturally competent skills. The comprehensive dissemination plan included online and print resources, social media communication, and professional webinars and short video clips. Second, we want to reach researchers interested in the translation of research to practice. We hope to disseminate to researchers by speaking at professional conferences and by writing the present commentary. An evaluation is also planned to determine effectiveness in translating research to practice. Some promising outcomes as of August of 2018 include over 6,000 downloads of the guide since publication in the spring of 2017, and two webinars that attracted over 500 participants (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dissemination of the guide through webinars. See the online article for the color version of this figure.

Despite increased research that describes disparities in mental health care and burden among racial/ethnic minority youth, as well as implementation of policies and programs to reduce them, disparate care and outcomes remain. In this commentary, we describe a process for translating evidence-based information for mental health practitioners as an additional strategy that has largely been underutilized to target reduction of disparities. We contend that an emphasis on social justice and an increased focus on knowledge translation may provide a new opportunity for eliminating mental health disparities. We believe our work provides an example of efforts that go beyond publishing research findings in academic journals and professional presentations at national meetings to increase the availability of evidence-based knowledge and strategies for mental health practitioners in the field. In our approach, we sought to overcome some existing challenges in translation but also focused specifically on the deliberate and targeted process for translating knowledge in the service of practitioners. We based our efforts on evidence-based models for knowledge translation, including the KTA (Graham et al., 2006), the CIM (Lomas, 1993), and the UUC (Jacobson et al., 2003). By applying these models, we aimed to maximize the effectiveness of our subsequent dissemination efforts by ensuring that the initial content, products developed, and eventual dissemination were grounded in scientific evidence and a thorough understanding of the needs and contexts of users.

Of primary importance, we made knowledge translation a deliberate task and developed a product that distills research. We engaged in a process of knowledge creation and adaptation to the local context of users. To this end, we sought stakeholder input prior to and during the development of the guide and focused on the explicit task of connecting research to practice in a guide for practitioners. This was an important need identified by users, who sought guidance on action they can take in order to have direct impact on addressing racial/ethnic minority disparities in mental health. Future efforts can benefit from a focus on understanding the user context and the specific needs of stakeholders and subsequently developing products designed to bridge research and practice using stakeholder input.

We actively sought stakeholder input through our discussion groups and working group, and encountered some challenges in that process. First, we assembled a working group with psychologists who had considerable expertise in mental health disparities, but most had academic backgrounds and/or affiliations. We advertised broadly through various APA division listserves, including those practice-focused, but no full-time, practicing-only, clinicians self-nominated to serve on the working group. It may have been helpful to reach out to practicing clinicians through state-level practice-focused organizations. As efforts to translate research to practice increase, having practicing psychologists’ voices “at the table” should be a priority. Concerted outreach to clinicians can ensure that their experiences with racial/ethnic minority youth, and within diverse practice settings, can drive such efforts. Second, the majority of nominations were of psychologists whose expertise was with African American/Black, Hispanic American/Latinx, and to a lesser degree, American Indian youth. Thus, we had limited expertise representing other racial/ethnic minority youth, such as Asian Americans. This challenge is concerning because the literature on Asian American youth is also relatively scant, leaving many practitioners with only a handful of resources to serve this population. Third, psychologists commonly work alongside various mental health practitioners, including social workers, psychiatrists, and counselors. Conducting discussion groups and opening the workgroup to practitioners across mental health fields would have been a logistical challenge but would have enriched our efforts and underscored the need for collaboration and a multidisciplinary approach to addressing racial/ethnic disparities in youth mental health. We leveraged our relationship and connections with national organizations (APA and William T. Grant) consistent with the CIM (Lomas, 1993). Reviewing the missions of nonprofit organizations and professional organizations/societies to identify those who have a focus on improving mental health care and outcomes for racial/ethnic minority youth can greatly improve and amplify the impact of work to translate information to reduce disparities. Psychologists can seek partnerships with compatible organizations to form working groups with the necessary expertise to translate evidence-based information, seek stakeholder input to best identify how information on disparities should be framed for the target audience, obtain and manage project funding, and/or maximize the reach and credibility of subsequent dissemination efforts.

Social justice has become a more commonly accepted goal in counseling, psychology, and related fields. In the process, it has been necessary to recognize the complexities and challenges in pursuit of this goal. In other words, it has been necessary to shift from merely focusing on outcomes and goals to that of understanding the processes and the actions necessary to reach such goals. At present, to fully grasp the essence of social justice, it is necessary to approach the construct from both an applied commitment and a developmental perspective (the focus of our work with the guide; Toporek, Sapigao, & Rojas-Arauz, 2017).

As the United States has become more racially and ethnically diverse, social justice, as action or outcome, has become a richer and more complex construct that must be treated as such if desired outcomes or products are to be attained. To put it another way, to effectively and efficiently attain desired social justice goals there is a great need for refinement and clarity of the term in relationship to projects, such as ours, that directly and carefully need to consider the cultural context in which the construct is embedded. You cannot use a “cookie-cutter” approach in setting social justice goals and actions. On the contrary, in line with our project, they must be culturally grounded and effective in all aspects of the project (e.g., selecting theories, methods).

As the pursuit of social justice has become a more comprehensive, tangible, and inseparable part of research and applied counseling ventures, counselors have accepted the need to diversify and/or expand the repertoire of theories, methods, skills, and roles which they need to utilize in order to attain desired social justice goals. With respect to roles, these would include: researcher, advisor, advocate, facilitator of indigenous support and healing systems, consultant, change agent, counselor, and psychotherapist (Atkinson, Morten, & Sue, 1993). Interestingly, these roles are the heart of the work described in this project. As federal initiatives change from one administration to the next, it is critical that psychologists use these roles to sustain and increase federal efforts to eliminate disparities.

Future directions for eliminating racial/ethnic disparities in child and adolescent mental health should also focus on developing and refining approaches for intentionally bridging the generation and dissemination of knowledge with an eye toward supporting changes in practice. Practitioners and researchers are equal partners with shared responsibility for eliminating disparities. Thus, practitioners and researchers can both engage in the translation process by working together to refine what is disseminated and how it is disseminated. Overall, psychologists’ engagement in translation activities and translation research can successfully expand the body of work that has been conducted to describe disparities and implement programs in order to eliminate the troubling and persistent disparate outcomes in mental health among racial/ethnic minority children.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the William T. Grant Foundation (Grant 185884)/and the American Psychological Association (APA).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the William T. Grant Foundation or the APA. The authors were part of the APA Working Group for Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Youth Mental Health and the APA Committee on Children, Youth and Families. Many thanks to Lauren Caldwell for reading a draft of this article, and to Alissa Forman-Alberti, Amani Chatman, Michael Sullivan, and Kishan R. Desai for their contributions to the project.

Footnotes

This view was expressed by Davey Strategies and FSG at a meeting at the Centers for Disease Control for the Essentials for Childhood Framework, for which the first author and the Director of the APA Office on Children, Youth and Families were in attendance in May of 2015.

Contributor Information

Carmen R. Valdez, Department of Population Health and Steve Hicks School of Social Work, University of Texas at Austin

Omar G. Gudiño, Department of Psychology, University of Denver

Natalie A. Cort, Clinical Psychology Department, William James College

Caryn R. R. Rodgers, Department of Pediatrics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Patricia Isaac, School of Graduate Studies, State University of New York Empire State College.

Manuel Casas, Department of Counseling, Clinical and School Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara.

Ashley M. Butler, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine

References

- Alegría M, Green JG, McLaughlin KA, & Loder S (2015). Disparities in child and adolescent mental health and mental health services in the U.S. Retrieved from https://wtgrantfoundation.org/library/uploads/2015/09/Disparities-in-Child-and-Adolescent-Mental-Health.pdf

- Alegría M, Vallas M, & Pumariega AJ (2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19, 759–774. 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2016). Eliminating health disparities among boys and men. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (APA). (n.d.). Health care reform: Disparities in mental health status and mental health care. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/about/gr/issues/health-care/disparities.aspx

- American Psychological Association. Working Group for Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Youth Mental Health. (2017). Addressing the mental health needs of racial and ethnic minority youth: A guide for practitioners. Retrieved from www.apa.org/pi/families/resoruces/mental-health-needs.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson DR, Morten G, & Sue DW (1993). Counseling American minorities: A cross-cultural perspective (4th ed.). Madison, WI: Brown and Benchmark. [Google Scholar]

- Bell LA (1997). Theoretical foundations for social justice education. In Adams M & Bell LA (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice: A sourcebook (pp. 3–26). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Kreuter MW, Arrington BA, & True WR (2006). Translating scientific discoveries into public health action: How can schools of public health move us forward? Public Health Reports, 121, 97–103. 10.1177/003335490612100118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J, … Lim C. (2008). Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance summaries, 57, 1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L, Keeler G, Erkanli A, Costello EJ, & Angold A (2001). Epidemiology of psychiatric disability in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 901–914. 10.1111/1469-7610.00786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, & Robinson N (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26, 13–24. 10.1002/chp.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resources Health and Administration Services. (2000). Eliminating health disparities in the United States. (HRSA Workgroup for the Elimination of Health Disparities report) Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa MS, Hinojosa R, Fernandez-Baca D, Knapp C, Thompson LA, & Christou A (2012). Racial and ethnic variation in ADHD, comorbid illnesses, and parental strain. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23, 273–289. 10.1353/hpu.2012.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge MA, Morris JA, Daniels AS, Stuart GW, Huey LY, & Adams N (2007). An action plan on behavioral health workforce development. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Holden K, McGregor B, Thandi P, Fresh E, Sheats K, Belton A, … Satcher D. (2014). Toward culturally centered integrative care for addressing mental health disparities among ethnic minorities. Psychological Services, 11, 357–368. 10.1037/a0038122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Butterill D, & Goering P (2003). Development of a framework for knowledge translation: Understanding user context. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 8, 94–99. 10.1258/135581903321466067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J (1993). Retailing research: Increasing the role of evidence in clinical services for childbirth. The Milbank Quarterly, 71, 439–475. 10.2307/3350410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Minority Health. (2011). HHS action plan to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. A nation free of disparities in health and health care.Retrieved from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/npa/files/Plans/HHS/HHS_Plan_complete.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001; (2010). [Google Scholar]

- President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. (2003). Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America: Final report (Pub. No. SMA-03–3832). Rockville, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Ratts MJ, & Hutchins AM (2009). ACA Advocacy Competencies: Social justice advocacy at the client/student level. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87, 269–275. 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00106.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (NREPP). (2016). Learning center literature review: Mental health disparities. Washington DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, & Sue D (2012). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N, Nagayama Hall GC, & Berger LK (2009). The case for cultural competency in psychotherapeutic interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 525–548. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toporek RL, Sapigao W, & Rojas-Arauz BO (2017), Fostering the development of a social justice perspective and action: Finding a social justice voice. In Casas JM, Suzuki LA, Alexander CM, & Jackson MA (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 17–30). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2001). Mental health: Culture, race and ethnicity—A supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez MJT (2012). Psychology and social justice: Why we do what we do. American Psychologist, 67, 337–346. 10.1037/a0029232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahowiak L (2015). Addressing stigma, disparities in minority mental health: Access to care among barriers. The Nation’s Health, 45, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2005). Bridging the “know–do” gap: Meeting on knowledge translation in global health. Retrieved from https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/training/capacity-building-resources/high-impact-research-training-curricula/bridging-the-know-do-gap.pdf