Abstract

We explore opportunities as well as challenges associated with conducting a mixed methods needs assessment using a transformative paradigm. The transformative paradigm is a research framework that centers the experiences of marginalized communities, includes analysis of power differentials that have led to marginalization, and links research findings to actions intended to mitigate disparities. We argue that a community needs assessment is a natural fit for the use of a transformative framework, serving as an entry-point for the development of responsive programmatic and funding decisions. Based on a case study of efforts initiated by a local community health foundation to document disparities in their city, we show how an evaluation team used principles aligned with the transformative framework to guide the design and implementation of a community needs assessment. The needs assessment provided a better understanding of the power of community relationships, demonstrated how lack of trust can continue to constrain community voices, and revealed why agencies must actively support a social justice framework beyond the end of an assessment to ensure transformative change.

Keywords: Transformative, Needs assessment, Marginalized community, Mixed methods, Funding agency

1. Introduction

The transformative paradigm has been championed by Mertens (1999, 2007, 2009) as a viable and compelling framework for research that incorporates a social justice orientation and advocacy for marginalized community voices. It influences how research is done by seeking to include voices that have not been heard before and requiring a researcher who “analyzes asymmetric power relationships, seeks ways to link the results of social inquiry to action, and links the results of the inquiry to wider questions of social inequity and social justice” (Mertens, 1999, p. 4). While Mertens discusses the value of the transformative framework for evaluation research in general, in this paper we argue that community needs assessment is a natural fit for the use of a transformative framework and can serve as an entry-point for the development of responsive programmatic and funding decisions.

We describe the development and implementation of a needs assessment of a predominantly Latino community located in a small city experiencing important demographic shifts. The overarching aim of the evaluators conducting the assessment was to identify key social determinants of health and well-being in the community. To the extent that social determinants involve disparities in social, political, and economic conditions that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks, the evaluation agenda became intertwined with a political agenda, and thus concerned with generating greater equity in the community (Segone, 2012). The context of the needs assessment and the historical involvement of the funding foundation in the community set the stage for the implementation of an action-oriented approach and the adoption of a transformative paradigm. The paradigm informed the methodology of the needs assessment, including staffing and reporting decisions, as well as the adoption of a mixed-methods design that incorporated the voices of residents, service providers, and other stakeholders. We discuss lessons learned by both the evaluation team and the funding agency regarding the successes and limitations in the implementation of a mixed methods needs assessment using the transformative framework. We include suggestions for future applications of the framework to needs assessment research. As this paper is a collaboration of both the evaluation team and the funding agency, findings or actions that relate specifically to either entity are identified as such.

1.1. Transformative theory in evaluation

Compared to other paradigms, such as post-positivist or constructivist, the transformative paradigm assumes that while there may be different cultural norms guiding ethical behavior, research should strive to examine aspects of power and privilege and to promote social justice (Mertens, 2009). A transformative paradigm emphasizes the use of qualitative and mixed methods to outline the ecological complexity of a situation and to access the voices of those who have historically been marginalized. Within this framework unique knowledge may be obtained through building relationships of trust with participants and that this knowledge might not be accessible through other methods.

The use of a transformative framework in evaluation studies is in alignment with the growth of evaluation methods that focus on cultural competency (SenGupta, Hopson, & Thompson-Robinson, 2004), cultural responsiveness (Hood, Hopson, & Frierson, 2005; Hood, Hopson, & Frierson, 2015; Hopson, 2009), and cultural humility (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998). These additions to the evaluation toolbox all emphasize an understanding of context, participant’s lived experiences, and the use of stakeholder input. They also require evaluators to take off the mantle of an expert, and enter spaces as a learner with an awareness of the contextual dependencies of power and knowledge, including a recognition of historical contexts that contribute to continuing disparities in social services. Transformative theory shares with these evaluation strategies an awareness of power differences within communities and a burden on evaluators to take thoughtful steps to counteract these differences.

1.2. Needs assessment as a place for transformative theory

Needs assessments are usually designed to evaluate gaps between current situations and desired outcomes, along with possible solutions to the gaps (Altschuld & Watkins, 2014). Though notions of gaps were historically framed in deficit perspectives, there has been a trend to move away from this lens to concentrate on studies of community assets instead (Altschuld, Hung, & Lee, 2014; Patton, 2003). They can differ from other types of evaluation in that the attention is on forward planning and the well-being of a community, rather than the specific workings and outcomes of a program (Altschuld & Watkins, 2014; Petersen & Alexander, 2001). As with all types of evaluations, however, organizational and community politics can shape a needs assessment (Abma & Widdershoven, 2008; House, 1980; Morris, 2015). Evaluators, policy makers, and institutional stakeholders are often the ones who choose indicators, sources of statistics, geographic outlines of a study area, timing of a project, and final prioritization of needs. There is potential for subjectivity given these choices, with research objectivity as a veil for decisions made by those in powerful positions. No matter how well-meaning the evaluators’ aims are, their decisions are shaped by their perception of the context.

The transformative tradition advocates for an understanding of who has been previously left out of assessments, as well as documenting unequal power systems as a necessary step for an accurate understanding of program impacts (Mertens, 2009). A needs assessment that has a transformative approach then becomes a way to communicate the views of marginalized groups to those in power. The evaluator takes on the role of a mediator through a process of “assisted claims making” (Morris, 2015) where marginalized groups communicate their needs and the evaluators lend assistance through research techniques to support these needs. The evaluator may also translate the community claims into calls for action that empower the community and motivate policy makers to undertake specific actions. This type of broad assessment is similar to what Kaufman and Guerra-Lopez (2013) call a “megalevel” assessment that focuses on societal value and “creating the world we want for future generations” (p. 30).

Needs assessments may be particularly challenging for culturally competent evaluation as needs are often associated with deficits in the community, rather than a strength-based approach. However, a needs assessment that uses a transformative approach could include a critical component that examines how needs within communities are constructed through systematic and institutional barriers and discrimination. Evaluators could move from regarding needs as problems within communities to problems that are enacted upon communities. In this framework evaluators can document the agency of individuals to counter barriers (SenGupta et al., 2004). For example, by documenting ways community members navigate through discriminatory policies, evaluators can identify assets within the community and use these strengths as the basis for amending existing programs or building new ones (Altschuld et al., 2014).

Undertaking a needs assessments from within the transformative framework can guide not just where the origin of needs are located, but also the methodological approaches that are used to document these origins. In parallel to Watkins and Altschuld’s (2014) recommendation that needs assessments use a mix of measurement methods to enhance validation of findings, Mertens (2009) underscores the necessity of including multiple methods within a transformative research study. Mertens, however, also adds an emphasis on using participatory and collaborative research methodologies. Community participation in needs assessments can range from simple outreach and consultation to shared leadership (Bledsoe & Donaldson, 2015; Cousins & Whitmore,1998). The most extensive community inclusion methodologies are usually undertaken in community based participatory research that include iterative processes of collaboration with community groups, along with shared control of the research process (Cousins & Whitmore, 1998; Teufel-Shone & Williams,2010; Woodyard, Przybyla, & Hallam, 2015). These methods require evaluators to actively engage with the community over long periods of time to gather sufficient information, as well as develop relationships and establish trust with the community.

Depending on the evaluation constraints, however, using both best practices of community based participatory methods and multiple data collection methods may not always be practical for the evaluation team (Bamberger, Rugh, Church, & Fort, 2004). In these cases, the transformative framework can help guide decisions about how to ensure quality and validity in the needs assessment by prioritizing choices that provide community perspectives with credibility (Mertens, 2009). The following section describes one such needs assessment, that while bounded by practical constraints, also sought to enact an evaluation informed with a social justice and transformative grounding.

2. The context of the needs assessment

2.1. About the city and recent demographic changes

To illustrate the applications of the transformative framework to needs assessment design, our case study focuses on a needs assessment of the southeast section of Greenfield, a small city located in Texas. According to the U. S. Census Bureau (2015), the city almost doubled in size between 2000 and 2010 and now has a population just under 60,000 people. Projections for future growth estimate that the population will be over 100,000 within the next 15 to 20 years (Texas Water Development Board, 2015). The city’s population growth is mostly attributable to migration into the city by non-Hispanic whites but also migration and births in the Latino population. The Latino population growth has been largely clustered in the southcentral and southeast of the city, with the white, non-Hispanic population growth largely occurring in the northwest. Much of the white population growth in the northwest can be attributed to a large, active retirement community built in the early 2000’s. The Latino population growth in the southeast quadrant of the city continues to expand the section of the city that has been home to the Latino population for generations.

Overall, the city has high income, high employment, and high education levels, but these overall numbers hide differences among areas of the city (U. S. Census Bureau, 2015). The zip code that corresponds to the central and southeast portion of the city has the lowest median income, the greatest number of children under 18 living in poverty, and the highest percentage of families that access public assistance programs. A fifth of the population in the zip code lacked health insurance. A portion of the southeast quadrant of the city is also an urban food desert (U. S. Department of Agriculture, 2010), meaning that the low-income population in this area has insufficient access to quality food sources. Over 45% of the population in the zip code identifies as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black or other, compared to less than a third across the city and less than a tenth in the northwest zip code (U. S. Census Bureau, 2015).

The southeast quadrant also includes the historic downtown area, which was established more than a century ago. Families have resided in the area for generations and have established trusted networks among each other. There is a very strong sense of community and community members turn to leaders within their network, often from local churches, for support, guidance, and camaraderie.

2.2. The funding foundation

The study was commissioned by the Greenfield Health Foundation (GHF), a foundation that supports nonprofit organizations offering a range of safety net services. Against the backdrop of record growth, GHF leaders, citizens, and city leaders were increasingly aware of disparities in access to public services and health care among the low-income population and communities of color, concentrated in the southeast corner of the city. These disparities were of particular concern for GHF whose mission is to support community health promotion in greater Greenfield and whose target population is low-income residents.

GHF began operation in 2007 as an intentional by-product of the sale of the local community hospital to a regional hospital network. The foundation’s mission, to generate and accelerate positive change in the community’s health, was defined as part of the sale and has remained unchanged. Original GHF staff, three of whom are still with the foundation, were employees of the hospital with training and experience in hospital administration. Leading up to the decision to commission the needs assessment, GHF was concentrating on organizational capacity building, as well as building financial capacity. Original grant making was relatively small and the process was closed, with non-profit organizations sought out by GHF staff for funding. In 2012, three years prior to this needs assessment, GHF added a staff member and opened the grant making process to applicants for the first time.

At the time Greenfield Health Foundation commissioned the study, its grant making was focused on improving the health and human service infrastructure. Grants were given to local nonprofit organizations that responded to a variety of needs, spanning access to primary and mental/behavioral health care to emergency financial assistance and affordable housing. As the city experienced unprecedented population growth, however, its nonprofit sector was challenged to scale alongside the increased demand for services and resources. Additionally, GHF had noted that interventions for families facing short- and long-term crisis required assistance from multiple agencies, resulting in disjointed, diffuse, and duplicative service delivery.

Despite the fact that the foundation was the largest private funder of nonprofit organizations in the community, the staff and board agreed that they needed to adjust their strategy if they genuinely expected the organization’s dollars to impact residents’ lives in meaningful ways. A change in strategy both explicitly and implicitly pointed to systems change, which the foundation knew it could not achieve on its own. A new strategic direction had to involve additional partners, including both public and private support. Additionally, collective impact strategies were viewed increasingly as a best practice. Indeed, according to Kania and Kramer (2011, p.38), “large-scale social change comes from better cross-sector coordination rather than from the isolated intervention of individual organizations.” Past strategic initiatives had been identified by analyzing data that were collected both within and outside the community, from funding partners to the Census Bureau. While these data pointed to infrastructural gaps, the existing narrative had yet to compel community decision makers to move toward decisive action.

Hoping that a different approach to data collection would guide GHF toward new strategies and motivate community leaders to work toward strengthening the city’s systems for the benefit of its low-income residents, the GHF community director proposed a voluntary needs assessment study that accessed the voices of low-income residents. GHF staff and board members had a sense of what the needs were, but that sense was grounded in anecdotal feedback and some limited review of demographic and institutional statistics, not from a systematic collection of voiced needs. Asserting that “better understanding the needs of the community from the community” was critical to priority-setting, the community director won support for a comprehensive needs assessment of Southeast Greenfield from the foundation’s board and put out a call for proposals.

3. The needs assessment methodology

The evaluation team that was selected to conduct the needs assessment proposed a multi-stage, mixed method project that would include interviews, focus groups, a community survey, and collection of census demographic data. The format was similar to the community health needs assessment methodology for rural communities described by Becker (2015). Becker’s rural community groups model employed a mixed methods design that included a bottom-up decision making process, with an awareness of the unique challenges posed by small, rural communities where “trust is the currency” (p. 17). The evaluation team defined “need” within this study as a lack of access to the social determinants of health, including economic stability, education, health and health care, and the built environment (Centers for Disease Control, 2015).

When designing the study, the evaluation team tried to balance social justice concerns with the relatively short nine-month timeline of the foundation call that was a product of the foundation’s desire to have data in hand when assessing their next round of grant applications. Adequate time to conduct an evaluation is a concern for both validity of the evaluation, as well as its dependability and utilization (Bamberger et al., 2004; Kirkhart, 1995). For example, a full community based participatory research design would not be feasible as these studies often run for over a year to build trust and collaboration between the assessment and the community teams and to allow for the iterative feedback process (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Teufel-Shone & Williams, 2010; Woodyard et al., 2015). Rather, deciding to build on one of the strengths of small towns—well-known community relationships—the evaluation team included a community expert and hired community liaisons to assist with the data collection and provide consultation.

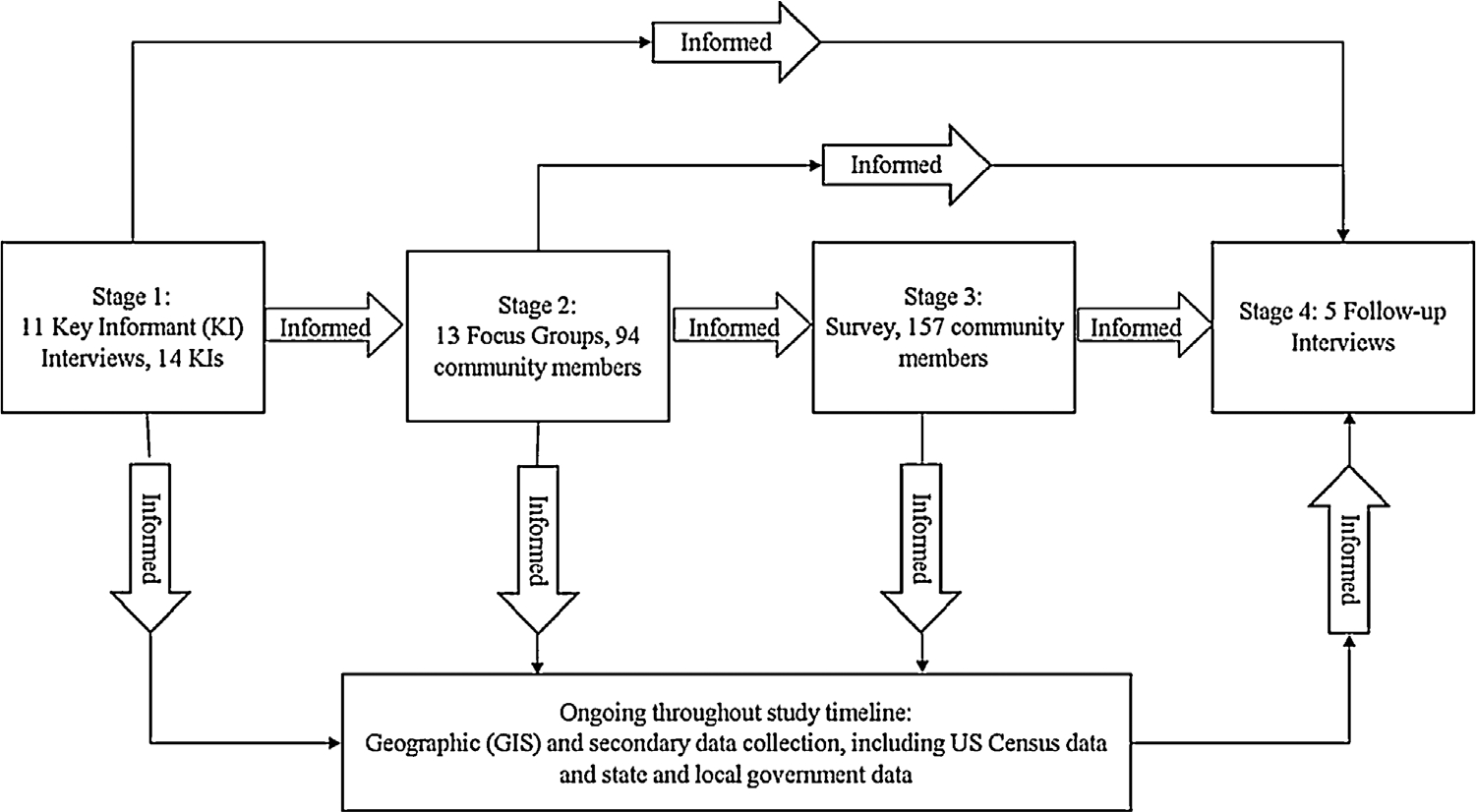

An overview of the mixed methods design of the study is shown in Fig. 1. Under the mixed methods taxonomy outlined by Creswell and Plano Clark (2007), the research framework was transformative and the design was a variant of sequential, exploratory mixed methods, which started with qualitative data collection and analysis (Stages 1 and 2), followed by quantitative data collection (Stage 3), and ended with another round of qualitative data collection (Stage 4). The research followed guidelines for human research participants established by the Institutional Review Board of the evaluation team’s host university. Focusing on the goal to access the voices of community members who had not previously been included in policy and community decision making, the team centered its approach in voiced research (Smyth & Hattam, 2001) with subsequent stages in data collection based on information gleaned from community voices in previous stages.

Fig. 1.

Stages of the mixed methods needs assessment conducted for the Greenfield Health Foundation. Following a sequential design, earlier stages of primary data collection influenced data collection and analysis decisions of subsequent phases and the ongoing geographic and secondary data collection and analysis.

To orient the team to the southeast community at the start of the project, the evaluators participated in a driving tour of the area led by the GHF community director and one of the community liaisons. The tour allowed the evaluation team to spatially place important local landmarks, such as schools, churches, and nonprofit organizations. It also allowed the evaluators to hear the histories of these landmarks. The tour revealed the varying conditions and existence of streets, sidewalks, grocery stores as well as the numbers and levels of repair and disrepair of houses, apartments, trailer parks, and RV parks – all of which are undetectable in census, socio-demographic, and GIS data. Over the course of the study, the team spent time visiting and interviewing participants at local schools, the library, a local bank, a local senior center, an afterschool community center, a RV park community center, an African American historic home, the local clinic, a nonprofit social service agency, and some government service offices.

The first stage of data collection consisted of interviews with key informants who worked directly with the community in public and social services. The first informants were chosen through consultation with the community director, the community liaisons, and a team member who worked in the town previously and through snowball sampling. Keeping in mind the small population of the town, the key people who worked with the target population were relatively well-known to each other and the community at large. A total of 14 interviews took place over the course of the study.

In the next stage, the evaluation team conducted 13 focus groups, four in Spanish, with a total of 94 community members. Focus group participants were recruited through snowball sampling and networking by the community liaisons, including social media use and paper flyers. The focus group protocol was based in part on the ongoing thematic analysis of the key informant interviews, as well as group debriefings and pilot testing with the community liaisons. We analyzed focus group and interview data thematically to identify community wants and needs. We also identified from the focus groups existing institutions and programs that the community saw as strengths, as well as barriers and challenges. Themes were checked through an iterative process that included debriefings with community liaisons, as well as discussions of themes raised in earlier focus groups with participants in later groups.

Based upon focus groups findings, the team created a paper/online survey that was pilot tested with assistance from the community liaisons. Using multiple-choice and short answer formats, respondents were asked about their access to current health services, their needs in specific areas identified by the focus groups, and demographic information. Some questions were created specifically for this study based on information gathered from previous stages, while other questions were part of accepted and validated social service questionnaires. Participants for the surveys were recruited through snowball sampling, flyers distributed through the local schools, and participation in local events (i.e. back to school events, community block nights, etc.) Participants in the surveys and focus groups had to be over the age of 18 and consider themselves residents of Georgetown, with members of the focus groups limited to living in or having lived a significant portion of their lives in the focal area of the study. Table 1 lists demographic information on study participants. Descriptive data analysis with computer statistical software was used to analyze surveys.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.a (N = 251).

| Participants | 94 participants in focus groupsb 157 participants in survey |

| Gender | 80% female, 20% male |

| Race/ethnicity | 48% Hispanic or Latino 12% Black or African American 33% White 3% Native American 3% more than one race/ethnicity |

| Age | 39% 18 to 34 years old 33% 35 to 54 years old 28% 55 years old and older |

| Education | 24% less than high school education 25% high school graduate 30% had some college or an associate’s degree/trade certificate 21% had a college degree |

| Children | 68% had children living at home |

Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Focus group demographics are based on 75 participants who completed an optional, anonymous demographic survey.

At the final stage, the team also met and interviewed five additional key informants who worked within an administrative capacity serving the community. These informants were chosen based on themes that emerged from the study. For example, as medical care and access to affordable housing emerged as areas of concerns in focus groups, the team reached out to administrators in these areas for interviews.

Focus groups and surveys were conducted and available in both English and Spanish, with recruitment material, such as flyers, also available in both languages. All key informant interviews were in English and approximately 11 percent of surveys were completed in Spanish. Within the focus groups and survey recruitment process, the team remained aware of mitigating micro-aggressions, and worked on enhancing the use of micro-affirmations, small gestures and actions that serve to welcome and include participants, rather than isolate and other them (Rowe, 2008). For example, the community expert created a “script” for explaining terms such as “de-identification” and “consent form” that was used in the focus groups. Following guidelines for site visits described by Becker (2015), all interviews and focus groups took place in the community, with the use of multiple informants at different stages of the project as an attempt to validate the findings (Kirkhart, 2005).

All of the primary data collection was supported by a parallel stage of secondary data analysis of U.S. Census and socio-demographic data from other sources, such as the CDC and the state’s department of education. The focus groups, interviews, and surveys influenced decisions about variables to examine in the datasets, beyond common demographic markers. For example, access to transportation was a recurring concern in all of the primary data collection, so the evaluation team collected information from the most recent 5-year American Community Survey on the mean number of cars by household and created a map to visualize the differences in means by census tracts.

3.1. Integrating the community into the evaluation team

The transformative paradigm emphasizes that researchers need to engage in critical self-reflection and to actively work to counter their own biases and assumptions, while establishing respectful partnerships within the community (Mertens, 2009). The evaluation team met regularly to reflect on their interactions with the community, debriefing after focus groups and interviews. The core evaluation team of four women shared ties to a local university either as professors, students, or researchers and did not live or work in the study area, but in neighboring cities. The core team included the primary investigator (PI), a project manager, a co-principal investigator (co-PI), and a community consultant. The core team was formed in response to the foundation’s call for proposals, with members invited by the primary investigator. After obtaining the grant, three students of the local university were also recruited to join the team by the PI and the co-PI.

The co-PI and two students were Spanish speakers and ran the Spanish language focus groups and provided translation for Spanish language materials. The PI, co-PI, and one student were associated with the social work department of the university, one student was majoring in the natural sciences, and other team members were associated with the education department. The community consultant held dual roles as a graduate student and staff at the university, and had previously worked in Greenfield with a college outreach program. In terms of race/ethnicity, the PI identifies as South Asian, the community consultant as Filipina American, the co-principal investigator and two students as Latina/Hispanic, one student as Black/Jamaican, and the project manager as White. All team members, excluding one student and the project manager, also identify as an immigrant or child of immigrants.

Coming from outside the study area and from a university, the team sought to prioritize community voices as a way to counter preconceptions in several ways. First, the core evaluation team included one member who had previously worked in Greenfield with an educational program and had community connections. In her capacity on the team, she worked to fine-tune aspects of the methodology, offered suggestions for data collection, and used her network to engage the community in the study. Her position was not a simple addendum to the evaluation team, but was integral within the initial proposal design, data collection, analysis, and dissemination phases of the project, especially for translating research for community understanding and giving others on the evaluation team an understanding of community history.

One of the benefits of including a community expert on the research team is the network that individual had within the target community. Given the critical importance of hiring community liaisons that were trusted members of the community, the community expert recruited and the core team interviewed two women who were active parent participants in the program the expert previously directed. The women were known to have broad, yet separate, networks within the southeast community and they also had previous professional experience in providing educational and social services. The liaisons positions were paid through the GHF grant to the evaluation team and some informal training on focus group procedures, participant recruitment techniques, and the use of a tablet for survey data collection was provided by members of the core team.

Both of the hired community liaisons, one who identifies as Hispanic/Latina and one as Hispanic and Native American, were current residents of the southeast community, were born and raised in the city, had graduated from the local high school, and raised children who attended the city schools. The liaisons provided instrumental help by participating in and providing feedback on a pilot focus group, piloting the paper and online surveys, providing critical feedback on research activities, and leading focus group and survey recruitment. The community liaisons provided invaluable background knowledge of their own lived experience as residents of southeast Greenfield and provided access to the voices of many other southeast Greenfield community members. According to Becker (2015), this type of access is especially necessary in small towns, where similarly to rural areas, there are often clear distinctions between native residents and new arrivals.

While not considered part of the evaluation team, the GHF community director was available for advice and consultation. Her initial recommendations for key informants provided the first steps in the evaluation process, and she was able to work within her networks to set up interviews with other key personnel that the evaluation team wished to interview. Throughout the process, the GHF community director and the evaluation team’s principle investigator were in contact with each other, communicating so as to increase the likelihood of utilization of findings (Greene, 1998).

3.2. Compiling the study findings and preparing the final report

The evaluation team documented both community assets and community needs. Starting with the assets, the evaluation team found that the southeast community appreciated the safety and neighborliness of the small town. The parks and schools were also viewed positively for the most part. However, participants in the focus groups and surveys suggested critical needs for public transportation, affordable and quality housing, access to healthy foods and nutrition programs, Spanish language access in schools, bullying programs and mental health care for children and adolescents, service provider training in cultural competency, and access to dentists. In addition, study participants felt there was a disconnection between the city’s decision makers and residents of the southeast community related to historical and geographic divisions.

As advocated for by the transformative framework (Mertens, 2009), the evaluation team intended the evaluation to potentially persuade decision makers, particularly the foundation board and community players, to enact policy and programmatic changes to alleviate disparities within the city. Thus, using strategies of communication for maximum effect on decision makers (Hall & Hood, 2005), the written report contained quotes from individuals along with survey and demographic data. This mixture of qualitative and quantitative findings was included in the report as a way for the team to both privilege community voices in the telling of their own story, while supporting these stories with quantitative data that are valued sources of information within the policy-making community (Hall & Hood, 2005). In the last section of the written report, the project team offered recommendations for action, including examples of successful model programs from other communities, often based on specific recommendations from the community. For example, a concern raised in focus groups was for more college access programming. The report discussed this concern and included information on a program that had been implemented in a nearby city that could serve as a model for Greenfield. The team supplied a range of policy and program recommendations, from programs that required long-term planning and extensive political buy-in, such as school-based health clinics, to smaller changes such as the addition of a community feedback mechanism for programs funded by GHF.

3.3. Getting the word out about the study findings

Study results were disseminated in several ways. The team presented findings twice: first to the board of the health foundation and a second time at a public conference that was open to anyone interested in attending. It was important to the foundation to bring the findings forward via a large-scale public presentation that invited the entire Greenfield community for two reasons: first, so that all community members had the opportunity to hear the findings at the same moment; and second, so that community members, including every sector of the Greenfield community, could see, listen, question, and learn together. It was equally important for GHF that the findings be presented by the evaluation team as it reinforced the objectivity of findings.

The public presentation was coordinated by the GHF community director and an administrator at the neighborhood high school. All focus group participants and key informants were sent personal invitations when possible. While the presentation was open to all, GHF’s community director and CEO also extended personal invitations to a list of approximately 250 community leaders and other individuals that they believed needed to be in attendance. Additionally, the GHF community director worked to get out word to the general public about the presentation through local media connections. Due to these efforts, the public presentation was attended by over 200 community members from government, business, nonprofit, faith, and education segments including the chief of police, juvenile justice personnel, a city council member and the city manager, chamber of commerce members, ministers and clergy, school board trustees, local nonprofit funders, and residents of southeast Greenfield. This level of turnout amplified the voices of study participants to reach community members and leaders who may not read the final report.

Following the evaluation maxim that there is no single best way to present data (Greene, 1998), the evaluation team carefully considered context and audience. The public presentation consisted of an introduction by the foundation to the project, followed by a PowerPoint presentation of the study findings, and concluded with a question and answer session. Different team members presented the findings in both English and Spanish in separate rooms, but questions were answered in one group meeting so that all public questions, asked both in English and Spanish, could be heard by the entire audience. The presentation was structured to emphasize participant voice with liberal use of quotes, reinforced with maps and survey findings, and limiting the use of academic jargon. A brief review of suggested possible future actions concluded the presentation before the question and answer session. The evaluation team also stayed after the presentation to answer questions and interact with community members who wanted to voice their concerns.

In the months following the public presentation, the study continued to be presented in many different venues by the GHF community director, including the local university, the chamber of commerce, city and county government boards, and coalitions involving nonprofit organizations and civic groups. The mayor, city manager, and all city council members received a copy of the study with an accompanying letter from the foundation that invited continued dialogue and discussion. The study and its executive summary are featured on the foundation’s website and have been shared each time the foundation has convened its funding partners. Copies of the executive summary in English and Spanish have been widely distributed throughout the community not only by the foundation, but by organizations that connect the findings and recommendations to their own work.

4. Lessons learned: key principles & approaches

The lessons derived from this needs assessment case study are divided into two main areas. We first discuss methodological concerns that came up as the evaluation team sought to incorporate a transformative paradigm into the needs assessment. We follow this with a discussion of how the funding agency’s organizational culture, expectations, and policies drove the evaluative process from the proposal call to community action. We try and draw particular attention to aspects of relationships and trust as they relate to the implementation of a needs assessment conducted under practical constraints of time, but with a transformative framework.

4.1. Flexible mixed methods allow for culturally responsive decisions

A needs assessment, as a form of applied social research, is concerned with describing complex social phenomena, but must do so using imperfect social science methods that are subject to measurement error and biases. As Greene, Benjamin, and Goodyear (2001) point out, however, mixed methods allows for a reduction in the uncertainty surrounding subjective measures, as well as the opportunity to understand a greater diversity of values and perspectives. The use of a sequential, mixed methods approach in this needs assessment had both advantages and disadvantages. On the positive side, the sequential mixed methods approach allowed for flexibility in data collection which is important in adding depth to the project (SenGupta et al., 2004). For example, the evaluation team was able to add more focus groups than originally planned after obtaining foundation approval. One of these later groups took place at a local trailer park that was initially difficult to contact, but which provided rich information about immigrants. While increasing the information gathered, the additional focus groups also extended Stage 2 of the project past its original timeline, delaying subsequent data collection, and extending the analysis time. The evaluation team had to request an extension of the deadline by a month and at least one more month would have been helpful to gather more survey responses. The timelines of a study attempting to be more responsive to hard-to-reach populations, then, might need to be extended beyond more traditional study components.

Another way the mixed methods approach influenced the research was in the creation of a more culturally relevant survey instrument. The evaluation team’s initial intent was for part of the survey to include questions in a traditional needs assessment format. This type of question format is based on the definition of need as a gap between “what is” and “what should be” and is common to many needs assessments (Lee, Altschuld, & White, 2007). The format includes a double-scaled prompt for participants to note their rating of importance and rating of current satisfaction regarding a particular need. However, the community liaisons and some of the core evaluation team members were concerned about the length of the survey and the ease and accessibility of that particular format. Therefore, the prompt was changed to only ask about the participants’ perceived need as “met” or “unmet,” limiting the measure to a rating of current need and not including the aspect of “importance.” This decision moved the survey away from a previously validated, but generic, form to a more community-sensitive measure of need.

Besides ease of understanding, another factor in the evaluation team’s decision to change the scale format was that the survey data were not the focus of the project, but rather served as support for qualitative data. The survey was envisioned as an aid to validate the needs identified through the focus groups and start to create a rough prioritization of the previously identified needs. Hopson (2009) notes that evaluations are traditionally concerned with methodology and instrument reliability and validity, but have neglected concerns of power, privilege, and racism which inform measures of multicultural validity (Kirkhart, 2005, 2010). However, having a sequential, mixed methods framework is helpful in this regard as the instrument was developed in combination with community voices from focus groups, written by academic researchers who are familiar with instrument development, and then pilot tested with the community liaisons. Thus items listed for the perceived need prompts were generated through the focus group discussions and were already vetted as potential areas of importance.

4.2. Diversity in team membership is key

One of the challenges facing community based research is the time-consuming process of establishing and building trusting relationships with community members (Chouinard & Cousins, 2009; Israel et al., 1998; Mertens, 2009). In some ways, including someone who had previously worked in the community as part of the evaluation team circumvented this problem. Additionally, the immigrant background of two Spanish speaking team members and the social service experience of others allowed some team members to serve as “boundary spanning” personnel (Chouinard & Cousins, 2009), able to negotiate meaning between the evaluation team, the community, and the funding agency. The project was thus able to build on some existing community networks and shared cultural ties through language. While not all projects will have the opportunity to have evaluation team members with these skills and community knowledge, this example does point to the need for and value of more inclusive development of evaluation teams and recruitment from diverse communities. Practical time constraints of program management and funding do not always make community based participatory research or other cyclical approaches with intensive time commitments possible. Therefore, the more diverse the evaluation teams, the more likely they are to have the skills to establish partnerships and community connections.

The most important tactic that the team used to address the concern with building community relationships, which is essential to the transformative framework, however, was hiring community liaisons. These team members did more than participant recruitment. They were empowered to suggest and direct data collection, and their input on focus group protocol and survey questions improved the authenticity of the evaluation, work that was in-line with recommendations by Israel et al. for community based research (1998). However, the community liaison’s project time was limited and they were not included in other aspects of the study, such as demographic data analysis and report writing, including the selection of quotes and finalizing the list of recommendations. This exclusion of community feedback from aspects of the study is not aligned with the transformative framework, but rather represented the core evaluation team’s estimate of how to best employ the limited time available, both in terms of hours the community liaisons had to give, as well as considerations for the study’s overall nine month timeline.

4.3. Relationships matter

Learning about the community through the use of social relations is a crucial step in the evaluation process (Abma & Widdershoven, 2008); social relations and networks within the community are a natural point of interest especially in the context of a broad community needs assessment. As the study was framed with a social justice persepctive, the evaluation team was empowered to critically examine the social relations and structures between the study community and service agencies (Mertens, 2009). By having the GHF community director access her networks to establish the first key contacts, the evaluation team utilized these relationships, as well as the networks of the team’s community expert and liaisons. However, the team also reached outside these networks, knowing that recruitment needed to extend beyond direct connections with members of the team or GHF staff. For example, team members cold called a local church that managed a community center at a RV park and arranged to hold a focus group there, as well as distribute surveys.

In the focus groups, discussions of power imbalances within the city between different neighborhoods and their influence with government, educational, and social service administrators, generated intense conversations with the participants, attesting to the importance of the perception of inequality in these community relationships. Following the evaluation, the funding agency continued to place relationships at the forefront of their work by requiring feedback whereby all stakeholders, including and especially the target population administered a given intervention, would have opportunities to weigh in on the efficacy of that intervention. The foundation is also venturing into financial support for political advocacy. GHF agreed to fund and support a local organization who approached GHF after the public presentation of study findings. The organization proposed to mobilize the southeast Greenfield primarily Latino and African American residents and grow the community’s leadership capabilities. Finally, the study’s emphasis on the importance of relationships and trust reminded the foundation to prioritize its relationships with funding partners through more frequent, intentional requests for feedback and input on their own grant making and reporting processes. This feedback from community programs on GHF’s new funding strategy is seen as a start of an iterative process to evaluate their own work.

While studying relations within the context of the needs assessment did lead to some positive outcomes, the social connections were not always easy to make or maintain. For example, while the city’s African American population is small in numbers, it has a long local history marked by segregation and neglect. Previously a segregated section of the city, the African American neighborhood is close to the city center, an area which is currently undergoing revitalization, displacing many of the local families out or away from family homesteads. Reaching the African American population was a special concern for the funding agency. One key informant was a prominent member of the African American community and helped organize a focus group at a historic house in the African American neighborhood that was attended by African American community members. However, despite spirited attempts by the evaluation team, particularly the work of the community liaisons, establishing relations with this community was more challenging than outreach to the Latino community. Whether the lack of participation was due to lack of trust or lack of relationship building, there remained a clear need to consider how connections with this community could be strengthened.

4.4. The culture of the funding agency significantly influences the evaluation

SenGupta et al. (2004) have noted that the culture of the funding agency can influence the evaluation and this was true for this needs assessment. The funder was a small, local organization of professional administrators who have worked together and in the community for several years. Most of the organization’s personnel, including the organization leadership, share a common social justice ethic. In addition to shared values and a common interest in understanding the experience of low-income Greenfield residents, the staff and board had well-established trusting relationships that were reinforced year over year by staff’s transparency with its work and decision making, the GHF community director’s history of using data to set the organization’s grant making agenda and her known connections in the community, the CEO’s confidence in the GHF community director, and the board’s willingness to engage constructively in difficult conversations. These characteristics match to a large degree the characteristics outlined by Greene (1998) for social service agencies that effectively utilize information from evaluations. Greene described these agencies as democratic, open, lacking office politics, and having a willingness to be critical, characteristics that were fostered and encouraged within the GHF by the CEO and board.

The need to identify an external organization to engage southeast Greenfield residents was motivated by the foundation recognizing its limits in collecting this information on its own. GHF staff knew that community leaders were more likely to support the findings of a study that were done by a neutral entity, outside Greenfield, that would be perceived as removed from the partisan pressures sometimes present in small communities. The board understood that they, too, needed impartial information to guide the strategic direction of the organization which they knew needed to change. As the evaluation team came from a highly regarded university that is located close to, but not in, the community, this is in line with work on research utilization that finds leaders are more likely to utilize research that is judged to offer viable reforms and to be truthful and of high quality (Weiss & Bucuvalas, 1980). The findings prioritized challenges that the organization was already working to address. For example, GHF staff members were aware of the need for health education, but did not know the community specifically was interested in education on nutrition.

4.5. Utilize the findings to move the community to action

While the information from the study continues to be disseminated, it has already made an impact on the work of the foundation. Internally, the foundation converted its primary funding program to its most basic level of giving, introducing two additional levels. Up to that point, the foundation had generally given grants to health and human service providers across the community. These investments responded to the needs of the agencies providing the services and supported their respective missions and strategies, but this funding was not serving as a catalyst for social change. Therefore, a responsive grant making program became the foundation’s first tier in its new funding structure. The second and third tiers, strategic philanthropy and collective impact, create space for more strategic goal-setting and new opportunities for GHF to solicit multi-pronged partnerships, which are leading to the development of scaled interventions benefitting GHF’s target population. This three-tiered approach gives the foundation the ability to continue to listen, learn from, and respond to health and human service nonprofit agencies, and simultaneously affords the flexibility to leverage dollars to nurture cross-sector partnerships that address the critical community needs identified in the study.

Approval of these additional levels of funding have opened the door for conversations about four different initiatives in partnership with the city, the local school district, and the founding of a grassroots organization that is working to engage southeast Greenfield’s primarily Latino and African American populations in local political advocacy. All of these initiatives are focused on systemic change: public transportation, mental health, improved systems to access health and human services, and engagement of marginalized voices in the political process. The foundation also altered its mission to address social determinants of health as a way to affirm its commitment to systemic change.

The study has in turn catalyzed community-wide projects in a relatively short period of time. A local agency official used the study findings to substantiate a grant funding request for an agency-based social worker. The funding was approved and the hiring of the city’s first social worker is underway. A non-profit also referenced the study in a grant application to justify bilingual counseling services. Another organization that provides after-school services has used the study to guide their strategic planning. These various outcomes demonstrate the value of using a transformative methodology with its focus on the utilization of findings for social change and social justice (Mertens, 2009).

5. Concluding remarks

The funding foundation’s goal in commissioning the needs assessment described here was not to develop or examine the workings of a particular program, but rather to assess where future funds could be directed to have a greater impact. This mega-level approach to the societal value an organization provides differs from the approaches of more traditional needs assessment that can have a specific programmatic evaluation focus (Kaufman & Guerra-Lopez, 2013). Utilizing a social justice perspective in line with a transformative framework, the evaluation team was able to help the funding agency hear the voices of community members, leading it to make institutional changes that are having wider impacts on other community organizations through their grant making process, amplifying the change (Mertens, 2009; Morris, 2015). There is an understanding in the foundation that sustainable change comes from engaging the whole community and that more community-driven interventions are needed to improve health and reduce disparities in racial and ethnic minority populations (Anderson et al., 2015). By relying on time to build trust and relationships with community groups, the foundation continues to work with data gathered from this needs assessment in efforts to address inequalities in their city.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend deep gratitude and appreciation to all the individuals who shared their expertise, time, and insights into their lives. We especially want to thank K. Mendoza and L. Nava without whose knowledge and passion for the evaluation, this project would not have garnered community support. We also thank the community leaders who gave us access to community members and community spaces so that we could hear as many voices as possible. Finally, we thank the Greenfield Health Foundation and its board for valuing the voice of the southeast community.

This research was supported by a grant from the Georgetown Health Foundation.

Biographies

Karen Moran Jackson is an Assistant Professor of Educational Psychology and Assessment at Soka University of American after working as the research associate at the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis at The University of Texas at Austin. She received her MA and PhD in Educational Psychology from The University of Texas at Austin. Her research interests include adolescent development, mixed methods, and the use of data.

Suzy Pukys is the Vice President of Strategic Philanthropy at the Georgetown Health Foundation.

Andrene Castro is a PhD student in the Educational Leadership and Policy program at The University of Texas at Austin. Her research primarily explores local teacher labor markets and teacher preparation programs. She is also interested in the intersections between schools and communities.

Lorna Hermosura is a PhD student in the Educational Leadership and Policy program at The University of Texas at Austin. Additionally, after over a decade of service as an educational administrator of college access programs for low-income students, including those residing in southeast Georgetown, Lorna has recently joined the Georgetown Health Foundation staff to assist in strategic advocacy and implementation of systemic and community-based solutions to the findings of this needs assessment.

Joanna Mendez is a Licensed Master Social Worker who received her Master’s degree in Social Work from The University of Texas at Austin in 2016. She works with Latino populations and those affected by trauma, including domestic violence and sexual abuse/assault, and provides bilingual counseling services.

Shetal Vohra-Gupta is the Associate Director of the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis and Adjunct Assistant Professor for the School of Social Work at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research areas include birth outcomes for low-income women of color and economic and labor policy as it related to women and families of ethnic minority groups.

Yolanda C. Padilla is the Clara Pope Willoughby Centennial Professor in Child Welfare at the University of Texas at Austin School of Social Work. She directs the Center for Diversity and Social & Economic Justice, a center of the Council on Social Work Education. Her research interests are in social disparities related to race and ethnicity with a focus on Latino and Latino immigrant communities.

Gabriela Morales received her Bachelor’s degree in biology from The University of Texas at Austin in May of 2016. She is continuing her education in medicine at the Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla starting in August of 2017.

APPENDIX A. Focus group protocol

Introduction activity:

You should have three blue and three pink stickers. Around the room are posters titled with different areas of concerns or services. Please, place a blue sticker under areas that you think are going well in your life and a pink sticker under areas that are most difficult.

[Poster headings: Health care; Mental/behavioral health; Food and nutrition; Housing; Transportation; Education; Youth; Child care/out of school programs; Senior services/Elderly concerns; Employment; Neighborhood safety/Crime; Parks/Recreation; Immigration concerns/services; Legal concerns/services; Other].

Questions: When everyone is back in their seats, ask the following.

Tell us about one of your green stickers? Why do you see that as a positive for Greenfield?

-

What do you want for yourself and your family?

Do you have it and what would help you to get it?

(If heath is not mentioned: Thinking about you and your family, how is your health and wellbeing? What would help your health and wellbeing?)

Who or where do you go to for help or support? Can you describe that experience?

What services (programs, resources) have not been helpful? Why?

Do you feel like the people who make decisions in Greenfield know what you go through? When have you felt like that? If you could tell people who make decisions in Greenfield one thing, what would like them to know?

If you had all the money and resources, what would your ideal vision be for the southeast Greenfield community?

References

- Abma TA, & Widdershoven GAM (2008). Evaluation and/as social relation. Evaluation, 14, 209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Altschuld JW, & Watkins R (2014). A primer on needs assessment: More than 40 years of research and practice. New Directions for Evaluation, 2014(144), 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Altschuld JW, Hung HLS, & Lee YF (2014). Needs assessment and asset/capacity building: A promising development in practice. New Directions for Evaluation, 2014(144), 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LM, Adeney KL, Shinn C, Safranek S, Buckner-Brown J, & Krause LK (2015). Community coalition-driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6. 10.1002/14651858.CD009905.pub2 Art. No.: CD009905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger M, Rugh J, Church M, & Fort L (2004). Shoestring evaluation: Designing impact evaluations under budget, time and data constraints. American Journal of Evaluation, 25(1), 5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Becker KL (2015). Conducting community health needs assessments in rural communities: Lessons learned. Health Promotion Practice, 16(1), 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe K, & Donaldson SI (2015). Culturally responsive theory-driven evaluation. In Hood S, Hopson R, & Frierson H (Eds.). Continuing the journey to reposition culture and cultural context in evaluation theory and practice (pp. 3–27). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (2015). Social determinants of health: Know what affects health. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/faqs/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Chouinard JA, & Cousins JB (2009). A review and synthesis of current research on cross-cultural evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 30, 457–494. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins JB, & Whitmore E (1998). Framing participatory evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 1998(80), 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Plano Clark VL (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Greene JC (1998). Communication of results and utilization in participatory program evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 11(4), 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Greene JC, Benjamin L, & Goodyear L (2001). The merits of mixing methods in evaluation. Evaluation, 7(1), 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, & Hood DW (2005). Persuasive language, responsive design. In Hood S, Hopson R, & Frierson H (Eds.). The role of cultural and cultural context: A mandate for inclusion, the discovery of truth, and understanding in evaluative theory and practice (pp. 41–60). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hood S, Hopson R, & Frierson T (2005). The role of culture and cultural context in evaluation: A mandate for inclusion, the discovery of truth and understanding. New York, NY: Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- Hood S, Hopson R, & Frierson H (2015). Continuing the journey to reposition culture and cultural context in evaluation theory and practice. Charlotte, NC: Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- Hopson RK (2009). Reclaiming knowledge at the margins: Culturally responsive evaluation in the current evaluation moment. The Sage international handbook of educational evaluation 429–446. [Google Scholar]

- House ER (1980). Evaluating with validity. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, Reissued by Information Age Publications, NC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kania J, & Kramer M (2011). Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9(1), 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman R, & Guerra-Lopez I (2013). Needs assessment for organizational success. Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkhart KE (1995). 1994 Conference theme: Evaluation and social justice seeking multicultural validity: A postcard from the road. Evaluation Practice, 16(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkhart KE (2005). Through a cultural lens: Reflections on validity and theory in evaluation. In Hood S, Hopson R, & Frierson H (Eds.). The role of cultural and cultural context: A mandate for inclusion, the discovery of truth, and understanding in evaluative theory and practice (pp. 21–39). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkhart KE (2010). Eyes on the prize: Multicultural validity and evaluation theory. American Journal of Evaluation, 31(3), 400–413. [Google Scholar]

- Lee YF, Altschuld JW, & White JL (2007). Problems in needs assessment data: Discrepancy analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning, 30(3), 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens DM (1999). Inclusive evaluation: Implications of transformative theory for evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 20(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens DM (2007). Transformative paradigm mixed methods and social justice. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(3), 212–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens DM (2009). Transformative research and evaluation. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Morris M (2015). Linking social-problem models to needs-assessment methodology in the teaching of evaluation. The American Sociologist, 46(4), 505–510. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2003). Inquiry into appreciative evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 2003(100), 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen DJ, & Alexander GR (2001). Needs assessment in public health: A practical guide for students and professionals. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe M (2008). Micro-affirmations and micro-inequities. Journal of the International Ombudsman Association, 1(1), 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Segone M (2012). Evaluation to accelerate progress towards equity, social justice and human rights. In Segone M (Ed.). Evaluation for equitable development results (pp. 2–12). New York, NY: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- SenGupta S, Hopson R, & Thompson-Robinson M (2004). Cultural competence in evaluation: An overview. New Directions for Evaluation, 102, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J, & Hattam R (2001). ‘Voiced’ research as a sociology for understanding ‘dropping out’ of school. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 22(3), 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, & Murray-Garcia J (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel-Shone NI, & Williams S (2010). Focus groups in small communities. Preventing Chronic Disease, 7(3), 1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) (2015). City population projections in texas [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.twdb.texas.gov/waterplanning/data/projections/2015/popproj.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US (2015). Selected area estimates, 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Retrieved from: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (2010). USDA—Food Access Research Atlas: 2010. Retrieved from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins R, & Altschuld JW (2014). A final note about improving needs assessment research and practice. New Directions for Evaluation, 2014(144), 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss CH, & Bucuvalas MJ (1980). Truth tests and utility tests: Decision-makers’ frames of reference for social science research. American Sociological Review, 45(2), 302–313. [Google Scholar]

- Woodyard CD, Przybyla S, & Hallam JS (2015). A community health needs assessment using principles of community-based participatory research in a Mississippi Delta community: A novel methodological approach. Community Development, 46(2), 84–99. [Google Scholar]