Abstract

Purpose

To predict ovulation in subfertile women using serial follicular growth (FG) and serum hormone measures (estradiol (E2), luteinizing hormone (LH), and progesterone (P) levels) in mathematical models.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study of 116 subfertile women aged between 18 and 40 years. FG was assessed by serial transvaginal ultrasonography starting from cycle days 8–12, depending on cycle length. Once the dominant follicle reached 15–16 mm, hormone levels were assessed daily. The primary outcome measure was ovulation (Ov), with a serum LH level ≥15 IU/l defining the start of the LH surge (the day prior to ovulation) and a serum P level >1 μg/ml concurrent with a drop in serum E2 levels indicating Ov. To determine Ov, mathematical models were generated using FG, LH, E2, and P measurements.

Results

A mathematical model was constructed using exponential regression to relate days until and after ovulation with P levels. The Ov(P) model was found to be superior to the Ov(LH) model in the prediction of Ov, with high R2 and low RMSE values of 0.9983 and 0.2454, respectively. In the range of [−2, 2] days, the net accuracy of the Ov(P) model was 63.0%, while with an allowed one-day error, the accuracy was 99.6%.

Conclusion

Serum P levels display a highly predictable linear curve in natural cycles, which enables the prediction of ovulation. The Ov(P) model can be independently used to schedule embryo transfer in natural frozen-thaw cycles and could therefore replace the Ov(LH) model in clinical practice.

Keywords: Ovulation time, Subfertile women, Progesterone, Estradiol, Luteinizing hormone

Introduction

Subfertility, defined as the inability to conceive after 1 year of unprotected regular intercourse, is reported among one in six couples planning pregnancy [1]. Ovulatory disorders are present in 50% of subfertile women; hence, confirming the occurrence of ovulation is critical for their evaluation [2]. Although it is thought that women with regular menstrual cycles have corresponding ovulatory cycles, nearly one-third of these women experience anovulation [3, 4]. Ovulation may be confirmed by various methods reported in the literature, such as ultrasonographic detection, determining a luteinizing hormone (LH) surge in peripheral blood or urine samples, or measuring the progesterone levels in peripheral blood samples taken in the mid-luteal phase [5–7]. Since no consensus exists on the definition of an LH surge, defined cutoff values differ, and ovulation detection may be imprecise [8].

In the last decade, natural frozen-thaw cycles (NC-FETs) have gained popularity due to greater patient friendliness as well as better maternal, obstetric and perinatal outcomes compared to programmed cycles [9]. In NC-FETs, the ovulation time is the critical parameter to improve implantation rates. Embryo-endometrial synchronicity on the day of embryo transfer is the determinant of pregnancy, so determining the time of embryo transfer by the ovulation time is crucial. The LH surge is the most commonly used indicator to define the ovulation time [10]. In clinical practice, imprecise results derived from patients’ LH surges cause ambiguity in clinical decisions, and plateaus in LH levels obscure the optimal timing of embryo transfer.

The synchronicity of a good-quality embryo and a receptive endometrium is essential to achieve pregnancy [11]. The progesterone secreted from the ovaries is required for the endometrium to be receptive. In patients with low progesterone levels and/or insufficient receptivity of the secretory endometrium, luteal phase defects arise, which may lead to decreased fertility rates and, ultimately, subfertility [12]. Therefore, to detect ovulatory disorders in patients, ovulation physiology must be well understood, and the cutoff values of reproductive hormone levels should be established.

Since such data are limited in the literature, identifying the optimal transfer time for NC-FETs and detecting ovulatory dysfunction in subfertile women should be guided by focusing on the hormone changes around the time of ovulation. In this study, we aimed to establish cutoff values of progesterone levels to detect ovulation in subfertile women by performing serial ultrasonography and blood sampling to observe changes in the serum levels of estradiol (E2), LH, and progesterone (P). Also, prediction of ovulation using serial hormone measurements may provide an opportunity to generate ovulatory prediction mathematical models that can be used in the prediction of ovulation in NC-FET.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a prospective, observational, single-center clinical trial. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Acibadem Mehmet Ali Aydinlar University (Institutional review board protocol no: 2021-23/04) and registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05211583 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05211583).

Study subjects

Subfertile women with regular menstrual cycles who had not conceived after 1 year of unprotected intercourse were included. Patients aged from 18 to 39 years were recruited from the population who presented to the In Vitro Fertilization Unit at the Acibadem Mehmet Ali Aydinlar University Atakent Hospital. Patients who had a menstrual cycle length between 24 and 38 days were not receiving any hormone therapy and would comply with the scheduled ultrasound visits and blood sampling for hormone analysis that were followed up. One hundred thirty-six women were initially included. Twenty women dropped out: 4 due to premature ovulation before hormone level evaluation, 5 due to a detected progesterone level >1 μg/l, 6 due to the absence of follicular development, and 5 due to noncompliance with the hospital visits. The data of 116 subfertile women were analyzed to model the progesterone, E2 and LH levels, and follicle size (FS) relative to the ovulation day (Ov).

Menstrual cycle monitoring

The participants were invited for the first evaluation on the second or third day of their menstrual cycle. Blood samples were obtained to detect baseline serum E2 and progesterone levels together with transvaginal ultrasound examinations to exclude ovarian cysts. Women with persistent ovarian cysts or progesterone levels > 1 μg/ml were excluded. Follicular development was examined on the 8th–12th days of the menstrual cycle via ultrasonography, considering the variance in menstrual cycle length among women. Once the dominant follicle had reached a diameter of 15–16 mm, blood samples were collected early in the morning each day. Serum E2, progesterone, and LH levels were measured at Acibadem Mehmet Ali Aydinlar University Atakent Hospital Biochemistry Laboratory using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Atellica IM Analyzer Estradiol, progesterone and LH, Siemens Healthineers, Germany). The assay for progesterone had a within-laboratory precision of ≤ 0.13 ng/ml SD for samples <1.0 ng/ml, a coefficient of variation (CV) ≤ 13% for samples from 1.0 to 6.50 ng/ml, a CV ≤ 6% for samples from 6.6 to 20 ng/ml, and a CV ≤ 6.5 for samples >20 ng/ml. The assay sensitivity for progesterone was ≤0.21 ng/ml.

Ovulation time was detected using serial ultrasonography and consecutive serum hormone analysis. To identify the time to ovulation, a serum LH level ≥15 IU/l was defined as “the day prior to ovulation” or the “LH surge.” A serum progesterone level >1 μg/ml and an observed concurrent drop in serum E2 levels were adopted to indicate the ovulation day. In cases not meeting the defined criteria, the ovulation time was identified by taking the serum hormone levels from 1 day prior or the day after into consideration. Five days after the defined ovulation day, serum progesterone levels were evaluated with reference to the day-5 blastocyst embryo transfer time in NC-FETs.

Data analysis

The data of 116 subfertile women were utilized to model P level, LH and E2 levels, and FS with respect to Ov.

The demographic data of the patients and the statistical information about the P level and LH, E2, and FS data are given in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Statistical information of the participants’ demographic data

| Mean | Std | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.75 | 4.19 |

| Menstrual cycle length (days) | 28.80 | 2.05 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.66 | 3.08 |

| Baseline estradiol (E2) (ng/l) | 47.88 | 19.16 |

| Baseline progesterone (PL) (μg/l) | 0.70 | 0.27 |

Data are presented as the mean (±SD)

Table 2.

Serial analysis of changes in hormone levels and follicle size with respect to the ovulation day (OV)

| OV = −4 | OV = −3 | OV = −2 | OV = −1 | OV = 0 | OV = 1 | OV = 2 | OV = 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone levels (μg/l) | N/A | 0.49 ∓ 0.22 | 0.61 ∓ 0.21 | 0.77 ∓ 0.19 | 1.34 ± 0.29 | 2.19 ± 0.52 | 4.28 ± 1.41 | 15.66 ± 5.66 |

| Estradiol levels (ng/l) | N/A | 262.23 ∓ 84.59 | 294.81 ∓ 122.21 | 353.97 ∓ 144.20 | 278.43 ∓ 151.2 | 134.49 ∓ 84.39 | 104.82 ∓ 35.88 | |

| Luteinizing hormone levels (mIU/mL) | N/A | 12.06 ∓ 4.2 | 36.96 ∓ 24.2 | 52.68 ∓ 28.57 | 23.28 ∓ 16.25 | 9.7 ∓ 1.62 | ||

| Follicle size (mm) | 13.5 ∓ 4.1 | 15.8 ∓ 1.8 | 17.6 ∓ 1.5 | 19. ∓ 1.3 | 18.9 ∓ 1.4 |

Data are presented as the mean (±SD). N/A, not applicable

Mathematical modeling

Nonlinear regression approaches were utilized to model P level and FS, LH, and E2 data as a function of Ov. When the data were examined, exponential and power functions, whose general forms are given in Eqs. 1 and 2, were determined to be the most suitable for P level and FS data, respectively. The LH and E2 data exhibited a Gaussian distribution; thus, the fit function was selected as the Gaussian function for these data, which is expressed in Eq. 3. Furthermore, LH and P level data were utilized together for the determination of Ov by using multinonlinear regression in the form given in Eq. 4.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

where a, b, c, and d are the arbitrary constants to be determined by regression, and t is the shifting constant that ensures that the term (x + t) is positive.

After function selection, the functions were fitted to the daily mean data of the patients by using the nonlinear least squares method with the trust-region algorithm [13]. The performance of the functions was evaluated by computing the R2 and root mean square error (RMSE) values [14], which are given in Eqs. 4 and 5, respectively. MATLAB R2022a (license number 40578168) was used to perform all calculations (Table 3).

| 5 |

| 6 |

Table 3.

Performance metrics of the fitted functions

| Model | R2 | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| P(Ov) | 0.9983 | 0.2454 |

| FS(Ov) | 0.9686 | 0.4772 |

| LH(Ov) | 0.9848 | 3.217 |

| E2(Ov) | 0.9308 | 33.05 |

Results

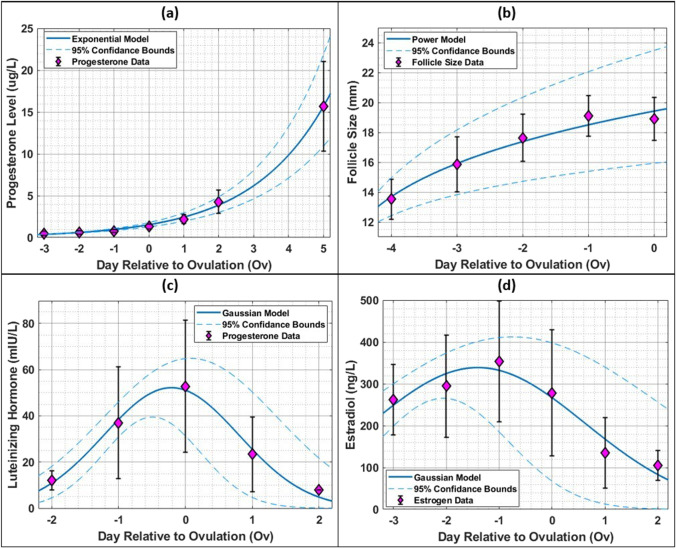

To determine Ov from the P level and FS, LH, and E2 data, the models were obtained as explained in the mathematical modeling section. The obtained models are illustrated in Fig. 1. Here, it is clearly shown that when the measured P level was >2 μg/l, ovulation likely occurred. When the P level was approximately 5 μg/l, the patients were highly likely to be between days 2 and 3 postovulation. The modeling with respect to FS yielded less reliable results, but when the FS was above 18 mm, Ov = −1 was reached. While the Gaussian fit was shown to be appropriate for the mean values of the LH and E2 data, the standard deviation was noticeably higher when compared to that of prior models. Here, it was also shown that the LH level peaked at the day of ovulation, as expected, while the E2 level peaked 1–1.5 days prior to the day of ovulation. Hence, the only period in which LH increased and E2 decreased was the interval between Ov =1.5 and Ov =0. Overall, it was shown that the most suitable model for the estimation of Ov was obtained from P data. The high R2 and low RMSE values clearly indicated that the constructed mathematical models accurately represented the data.

Fig. 1.

Changes in progesterone levels (a), follicular size (b), LH levels (c), and estradiol levels (d) according to the day of ovulation. PL, progesterone level; FS, follicular size; LH, luteinizing hormone; ES, estrogen; Ov, ovulation

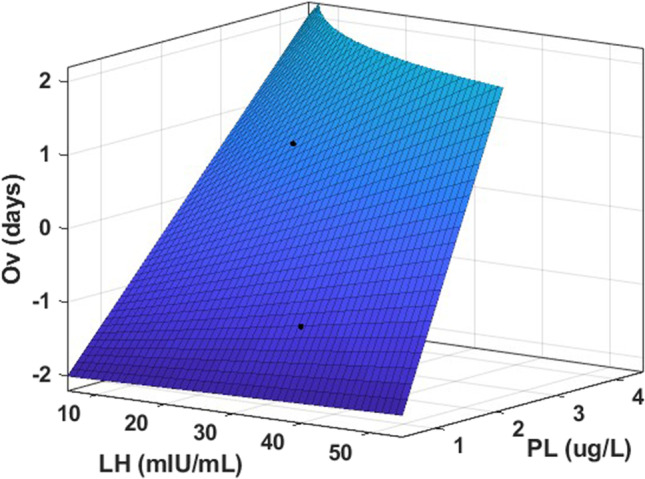

Furthermore, the multinonlinear relationship among Ov, the LH level, and the P level is shown in Eq. 7 and illustrated in Fig. 2. The R2 and RMSE values were 0.9711 and 0.5374, respectively, which proved the success of the regression:

| 7 |

where a = −0.01029, b = 0.8318, c = 0.02917, and d = −2.378. The outcome of the function is multiplied by 24 to obtain the result in hours.

Fig. 2.

Multinnonlinear modeling of Ov with respect to the PL and LH level. The effects of the PL and LH level on Ov are combined in this model. PL, progesterone level; LH, luteinizing hormone; Ov, ovulation

While Eq. 7 combines the effects of the P level and LH level on Ov, the claim of this paper is that P level data provide precise information about Ov, with a small RMSE value.

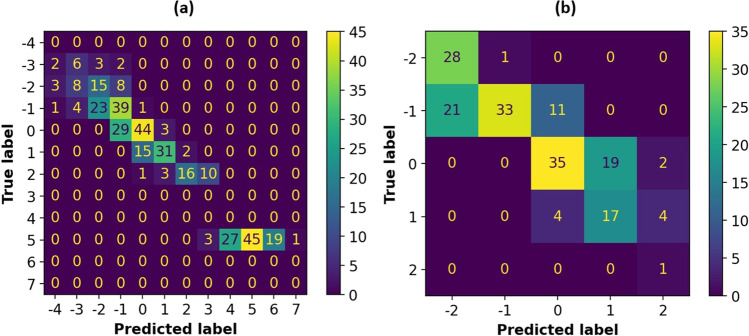

While high levels of LH could directly indicate the day of ovulation, the model could not be utilized by itself since it gave two outputs for the day relative to ovulation. Even if the correct output of the Ov(LH) model was selected, it was shown that the Ov(P level) model was superior, with lower RMSE and higher R2 values. To decisively validate this claim, 364 P level and 176 LH measurements obtained from the 116 patients were utilized for accurate estimation analysis. Figure 3 shows the confusion matrix of the models. Here, it is shown that the Ov(P level) model was accurate in most cases because the diagonal of the matrix was sufficiently brighter. While the net accuracy was 53.8%, if an error of 1 day was allowed, the accuracy became 95.9%. This shows that the model is highly accurate. The Ov(LH) model also performed sufficiently well, with a net accuracy of 64.8% and an allowed 1-day error accuracy of 98.9%. However, these results may be misleading since to determine if the day is −2 or +2 or −1 or +1, the Ov(P) or Ov(FS) models must be utilized for the patients. Furthermore, in the range of [−2, 2] days, the net accuracy of the Ov(P) model was 63.0%, while when a 1-day error was allowed, the accuracy was 99.6%. Thus, it was shown that the Ov(P) model was superior to the Ov(LH) model since it could be used independently, could yield accurate outputs in a wider range, and was more accurate than the Ov(LH) model in the same output range.

Fig. 3.

Confusion matrix for validation of the performance of the Ov(PL) (a) and Ov(LH) (b) models

Discussion

In this study, our goal was to identify ovulation in natural cycles by measuring serial FG and serum hormone LH, E2, and P levels in subfertile women. A mathematical model was constructed to determine the time of ovulation and elapsed time after ovulation. While it was shown that Ov could be satisfactorily determined by the P level and FS, in the literature, LH levels are utilized more commonly in Ov prediction. Hence, by using the collected data, we also developed a mathematical model combining the relationship of LH levels and P levels for Ov estimation. By using this mathematical model, the optimal time to transfer an embryo in NC-FETs can be determined specifically based on the P level.

NC-FET is increasing in popularity since it is associated with favorable obstetric and perinatal outcomes [15]. However, the challenge related to NC-FETs is the accurate measurement of the time to ovulation, which is essential to improve the cumulative live birth rates of natural cycle/frozen-thaw cycles. In the literature, the day relative to ovulation is generally determined by the LH level. However, in this study, it was shown that the P level can be more reliable in the determination of the day relative to ovulation. Although the LH surge is the most commonly used tool to identify ovulation in the literature, there are several definitions of the LH surge, with no consensus [16]. Since the time between the LH surge and ovulation differs among women, the time interval ranges from 22 to 56 h [8]. However, it is known that the configuration and amplitude of the LH surge may differ among women, even between an individual’s menstrual cycles. Moreover, another challenge is whether the LH level is obtained on the ascending or descending limb of the surge. In addition to these issues, approximately 25% of women have an LH surge after ovulation [6]. Correlatively, LH values at Ov = −1, Ov=0, and Ov = +1 LH, obtained from our data, were the same cutoff values as those from the literature, suggesting that the timing of embryo transfer as determined by LH levels may only lead to missed implantation windows. Therefore, with the help of a mathematical model utilizing levels of both LH and progesterone, it is possible to precisely determine the ideal time of embryo transfer.

Several studies of natural frozen-thaw cycles considered follicular collapse as a criterion for ovulation detection to determine the transfer time. However, the sensitivity and specificity of follicular collapse for ovulation detection are 84.3% and 89.2%, respectively [17]. Undetected follicular collapse in some women and the presence of luteinized unruptured follicles are limiting factors of follicle follow-up. In our study, increases in progesterone levels did not coincide with follicular collapse in some participants. Therefore, uncollapsed follicles may mislead practitioners in the detection of the ovulation time.

According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Committee Opinion, the evaluation of ovulatory function is a basic test to assess infertile couples [2]. P level analysis during the luteal phase represents objective and reliable evidence of ovulation. A serum P level >3 μg/ml measured a week prior to the expected start of menstruation confirms ovulation [5]. However, it remains unclear whether these values are sufficient to confirm adequate endometrial receptivity to form a functional secretory endometrium for implantation [12]. Therefore, in subfertile women, insufficient P levels in the luteal phase may be the reason for infertility. Midluteal P levels are <10 μg/ml in women diagnosed with luteal phase insufficiency [18], clinically defined as a luteal phase lasting <10 days. Similarly, higher cumulative live birth rates are associated with a P level >10 μg/l on the day of or 1 day prior to embryo transfer in frozen-thaw cycles.

P levels in the luteal phase are correlated with follicle stimulating hormone, E2, and LH levels in the follicular phase of the same cycle. Insufficient follicular hormone production may therefore result in progesterone deficiency during the luteal phase. In this sense, data not fitting the logarithmic curve suggested in this study may raise suspicion of luteal phase dysregulation in a patient. Low P levels after ovulation might be the cause of infertility and failed implantation, so monitoring the P level beyond that of ovulation is also important. Given that progesterone secretion is thought to be pulsatile and that, consequently, values measured in short periods may fluctuate between 5 and 40 ng/ml [19], we did not observe fluctuations in relation to the early days of ovulation, and the linear curve relating P levels to the ovulation day was consistent. In the literature, serum P levels are not commonly used to detect ovulation in NC-FETs. However, in the current study, serum P levels show a highly predictable linear curve that enabled the accurate prediction of ovulation. Therefore, P levels could be used to schedule embryo transfer in NC-FETs by accurately predicting the ovulation day and ensuring embryo-endometrial synchronicity on the day of transfer.

A strength of this study was the identification of changes in serum hormone levels to detect ovulation in subfertile women, with a proposed mathematical model to predict the time to ovulation. The study limitations include the exclusion of women aged >40 years from the study. Another limitation is that the sample was limited to volunteers and subfertile women. It would be interesting to validate this predictive model in fertile women with regular menstrual cycles and compare the differences related to hormonal changes.

Conclusions

Our proposed mathematical model may be used in clinical practice to detect the ovulation time, especially for NC-FETs, and enables the use of progesterone as a tracking biomarker alongside LH. This model and serum progesterone levels as an important indicator in NC-FETs suggest a potential space to investigate pregnancy outcomes of NC-FETs in future studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Dr. Inci Albayrak, PhD for her contributions in the design of the mathematical model that we suggest.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the findings of the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data will be made available to the editors of the journal for review or query upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Farquhar CM, Bhattacharya S, Repping S, Mastenbroek S, Kamath MS, Marjoribanks J, et al. Female subfertility. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):7. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Fertility evaluation of infertile women: a committee opinion. Fertility Sterility. 2021;116(5):1255–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malcolm CE, Cumming DC. Does anovulation exist in eumenorrheic women? Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(2):317–318. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00527-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prior JC, Naess M, Langhammer A, Forsmo S. Ovulation prevalence in women with spontaneous normal-length menstrual cycles - a population-based cohort from HUNT3, Norway. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wathen NC, Perry L, Lilford RJ, Chard T. Interpretation of single progesterone measurement in diagnosis of anovulation and defective luteal phase: observations on analysis of the normal range. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288(6410):7–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6410.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roos J, Johnson S, Weddell S, Godehardt E, Schiffner J, Freundl G, et al. Monitoring the menstrual cycle: comparison of urinary and serum reproductive hormones referenced to true ovulation. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;20(6):438–450. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2015.1048331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y, Sun Y, Hao C, Zhang H, Wei D, Zhang Y, et al. Transfer of fresh versus frozen embryos in ovulatory women. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):126–136. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erden M, Mumusoglu S, Polat M, Yarali Ozbek I, Esteves SC, Humaidan P, et al. The LH surge and ovulation re-visited: a systematic review and meta-analysis and implications for true natural cycle frozen thawed embryo transfer. Hum Reprod Update. 2022;28(5):717–732. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmac012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginstrom Ernstad E, Wennerholm UB, Khatibi A, Petzold M, Bergh C. Neonatal and maternal outcome after frozen embryo transfer: increased risks in programmed cycles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(2):126.e1–126e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mumusoglu S, Polat M, Ozbek IY, Bozdag G, Papanikolaou EG, Esteves SC, et al. Preparation of the endometrium for frozen embryo transfer: a systematic review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:688237. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.688237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(23):1796–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility Diagnosis and treatment of luteal phase deficiency: a committee opinion. Fertility Sterility. 2021;115(6):1416–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Least-Squares (Model Fitting) Algorithms - MATLAB & Simulink (mathworks.com) 2022.

- 14.Yaka H. A comparison of machine learning algorithms for estimation of higher heating values of biomass and fossil fuels from ultimate analysis. Fuel. 2022:320. 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.123971.

- 15.Lawrenz B, Coughlan C, Melado L, Fatemi HM. The ART of frozen embryo transfer: back to nature! Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020;36(6):479–483. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2020.1740918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godbert S, Miro F, Shreeves C, Gnoth C, Johnson S. Comparison between the different methods developed for determining the onset of the LH surge in urine during the human menstrual cycle. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292(5):1153–1161. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3732-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ecochard R, Marret H, Rabilloud M, Bradai R, Boehringer H, Girotto S, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound indices of ovulation in spontaneous cycles. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;91(1):59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(99)00249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schliep KC, Mumford SL, Hammoud AO, Stanford JB, Kissell KA, Sjaarda LA, et al. Luteal phase deficiency in regularly menstruating women: prevalence and overlap in identification based on clinical and biochemical diagnostic criteria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(6):E1007–E1014. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filicori M, Butler JP, Crowley WF., Jr Neuroendocrine regulation of the corpus luteum in the human. Evidence for pulsatile progesterone secretion. J Clin Invest. 1984;73(6):1638–1647. doi: 10.1172/JCI111370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the findings of the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data will be made available to the editors of the journal for review or query upon request.