Abstract

Background

Advances in Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) have expanded the treatment landscape for Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Guidelines recommend adding either conventional synthetic (cs), biologic (b), or targeted synthetic (ts) DMARDs to methotrexate (MTX) for managing RA. Limited evidence exists regarding the factors that contribute to adding a DMARD agent to the MTX regimen. This study examined the factors associated with adding the first DMARD in RA patients initiating MTX.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study utilized the MarketScan data (2012–2014) involving adults (aged ≥18) with RA initiating an MTX (index date) between Jul 1, 2012 and Dec 30, 2013, and with continuous enrollment for the 6-month pre-index period. The combination therapy users received the first treatment addition of DMARD starting from day 30 after the index MTX over one year period. The study focused on the addition of csDMARDs, Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors (TNFi) bDMARDs, non-TNFi bDMARDs, or tsDMARDs. Baseline covariates were measured in the 6-month pre-index and grouped into predisposing, enabling, and need factors, as per the Andersen Behavior Model. Multivariable logistic regression examined the factors associated with the addition of TNFi compared to adding a csDMARD. An additional regression model evaluated the factors associated with adding any biologic (combining TNFi and non-TNFi biologics).

Results

Among 8350 RA patients starting MTX, 31.92% (n = 2665) initiated any DMARD within the 1-year post-index period. Among RA patients initiating a DMARD prescription after starting MTX, 945 (11.32%) received combination therapy with treatment addition of a DMARD to MTX regimen; majority added TNFi (550, 58%), followed by csDMARD (352, 37%); non-TNF biologic (40, 4%), or tsDMARD (3, 0.3%). The tsDMARD group was limited and was not included for further analysis. The multivariable model found Preferred Provider Organization insurance coverage (odds ratio [OR], 1.43; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.06–1.93), chronic pulmonary disease (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.14–3.44), liver disease (OR, 5.24; 95% CI, 1.77–15.49), and Elixhauser score (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86–0.97) were significantly associated with the addition of TNF-α inhibitors. The separate multivariable model additionally found that patients from metropolitan areas (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.04–2.16) were positively associated with adding any biological agent.

Conclusions

TNFi are often added to MTX for managing RA. Enabling and need factors contribute to the prescribing of a TNFi add-on therapy in RA. Future research should examine the impact of these combination therapies on RA management.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, Tumor necrosis factor inhibitor biologics, Combination therapy, Methotrexate, Biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Highlights

-

•

Guidelines recommend adding Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) after starting Methotrexate (MTX) for Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA).

-

•

Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors (TNFi) are commonly added after MTX initiation, followed by another conventional synthetic (cs) DMARD.

-

•

The enabling f and need factors o were found to be associated with addition of a TNFi.

-

•

Findings demonstrate that potential variation in treatment utilization of MTX-based combination therapy in patients with RA.

1. Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune and inflammatory disease characterized by chronic inflammation in synovial joints, with typical clinical features such as joint stiffness, swelling, and pain.1 RA primarily affects joints, potentially leading to joint damage and permanent disability.2 In the US, approximately 1.36 million patients, or 0.55% of the population, are living with RA.3 Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), as the core of RA therapy, are classified as conventional synthetic (cs) DMARDs, biological (b) DMARDs, and targeted synthetic (ts) DMARDs.4,5 The csDMARDs, such as methotrexate (MTX), inhibit disease progression based on empiric observation.2 Biological DMARDs (i.e., tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapy or interleukin-6 receptors) target the molecules/cytokines of the inflammatory pathways underlying the RA pathogenesis and are becoming a new paradigm for RA treatment in the last two decades.5 TNFi such as adalimumab were the first biologic therapy, and over time, non-TNFi biologics such as abatacept, rituximab, and tocilizumab directing multiple molecular targets of the immune pathways (T-cell co-stimulation, and interleukin-6) also became available. The tsDMARDs, a small molecule targeting the Janus Kinase family, marked the most recent progress in the treatment portfolio for patients with RA and became an alternative DMARD option since 2012.6, 7, 8

The csDMARD, preferably MTX is often used as the first-line pharmacotherapy for RA. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines recommend treatment addition with either another csDMARD or b/tsDMARDs for the management of RA after MTX initiation.4,5 There exists a substantial patient population with the need for additional DMARDs beyond MTX, as 50% of patients with RA have persistent disease despite the use of MTX alone.6 However, there are no recommendations about the preference of b/tsDMARDs over csDMARDs as the add-on therapy, given limited clinical evidence of prognostic markers-based treatment principles.7,8 From the perspective of maximizing clinical improvement, the treatment addition of b/tsDMARDs was favored over another csDMARD, with evidence from real-world studies that support greater persistence of the combination regimen of b/tsDMARDs plus MTX than those added another csDMARD to MTX9, 10, 11 and randomized trials showing non-inferiority across both strategies of treatment addition.12,13 In contrast, studies suggest that alternative csDMARDs may be prioritized in certain patient groups with underlying comorbidities due to the the risk of adverse events (i.e., malignancy or infection to these biologics).14., 15, 16 Furthermore, selecting the first DMARD for treatment addition in RA is a decision with considerable cost implications as biologics cost much more than the csDMARDs.20

Studies have identified patient-, disease- and treatment-related factors are associated with the decreased likelihood of initiating biologics. These include older age,17, 18, 19 non-White19 or African Americans,17,20 multiple comorbidities18,19,21 and steroid use.17,18,21 Sociodemographic considerations may also negatively influence this decision, including Medicare/Medicaid enrollment,17,21 annual household income<$30,000,22,23 and living in a rural area.20,22 Previous studies mainly included a broader population of RA starting a biologic prescription, and none specifically studied patients on combination therapy with treatment addition of biologic therapy to MTX. Despite the evolving DMARD treatment landscape in RA, limited evidence exists regarding the factors that contribute to adding a DMARD agent to the MTX regimen. Identifying the factors associated with add-on DMARD prescription will help to understand the role of clinical and sociodemographic factors in the treatment selection involving MTX combination therapy with DMARDs for RA. The current study aimed to investigate the factors affecting the addition of a DMARD in patients with RA after receiving MTX therapy.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

This retrospective cohort study was conducted following the process guided by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for executing and reporting observational studies.24 This study utilized the data from the MarketScan database (2012–2014) to achieve the study objectives.25,26 The MarketScan database contains insurance claims made by millions of self-insured employers-covered and other private health plans-covered working adults and their dependents in the US, representing a nationwide commercial insured people. The MarketScan databases capture longitudinal medical and pharmacy claims, including inpatient admissions, emergency department visits, outpatient services, and outpatient prescriptions. Data from 2012 through 2014 were merged for analysis using a unique linked patient identifier. The study was approved by the University of Houston Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Study design and patient identification

The study design and key elements were developed using the International Society of Pharmacoepidemiology (ISPE) for implementing and reporting real-world studies and presented in Figure 1.27 Study population were adult patients (aged ≥18 years) receiving an initial MTX prescription between July 1, 2012, and Dec 31, 2013 (the earliest claim is the index date) and with a diagnosis for RA identified based on ≥1 outpatient or inpatient diagnosis claim (using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9-CM code]: 714.0) during the 6-month interval within the index date.18,21 The index date was the first MTX prescription, and the baseline period was the six months preceding the index date. Patients with no prescription fills for MTX during the 6-month pre-index period were selected to identify a cohort of new MTX users. All patients had continuous enrollment during the 6-month baseline period. Those with concomitant diagnosis of other inflammatory disorders (psoriatic arthritis, Crohn's disease, plaque psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or ulcerative colitis) during the 6-month interval within the index date that could necessitate treatment with csDMARD, TNFi or non-TNFi were excluded (see the supplementary eTable2 for a list of ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes).

Fig. 1.

Study design.

INCL = inclusion, EXCL = exclusion; RA = rheumatoid arthritis, DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

$ ISPE structured template for planning and reporting on the implementation of real-world evidence studies.

*NDC/HCPCS codes, ICD-9-CM codes ** Excludes psoriatic arthritis, Crohn's disease, ankylosing spondylitis, plaque psoriasis.

Given the study's focus on identifying the first add-on DMARD therapy, those who had been prescribed another csDMARD, TNFi, non-TNFi biologic, or tsDMARD during the 6-month pre-index period through 30 days after the index date were excluded (see the supplementary eTable1 for a list of National Drug Code (NDC)/Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes).19 To assess treatment addition with a DMARD prescription, RA patients on combination therapy of DMARDs and MTX was created. To contrast between addition with different types of a DMARD prescription, all included patients were required to receive another csDMARD, TNFi, non-TNFi, or tsdAMRDs during the follow-up. Further, to ensure that these patients were prescribed a DMARD add-on therapy to existing MTX, these patients were required to receive a prescription refill for MTX therapy during the follow-up because it improves the specificity of identifying RA patients staying on MTX with the treatment addition of a DMARD prescription.

2.3. Assessment of addition of a DMARD prescription

The operational definition for combination therapy initiating a DMARD with MTX was defined per prior studies.28,29 Eligible patients were required to have a prescription refill for MTX in the first 30 days from DMARD initiation. These patients were evaluated for the addition of DMARD prescriptions starting from day 30 after the index date till one year after the index date.19 The addition of a csDMARD (hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, leflunomide), TNFi (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab), non-TNFi bDMARDs (rituximab, anakinra, tocilizumab, abatacept), or tsDMARD (tofacitinib) was assessed during the 12-month post-index period starting from day 30 after the index date. The earliest prescription of these DMARDs added is considered the choice of add-on DMARD therapy. The prescriptions for DMARD medications were assessed based on pharmacy claims records for subcutaneously administered or oral medications and procedure claims (Current Procedure Terminology [CPT] and HCPCS) for intravenously administered drugs (see the supplementary eTable1 for a list of NDC/ HCPCS codes used).

2.4. Conceptual framework of study variables

Baseline variables associated with the treatment addition of a DMARD were measured during the 6-month pre-index period and grouped based on the Anderson Behavioral Model (ABM). According to the ABM, health service utilization is a function of predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors.30 Based on existing literature26,34, 35, 36 and data available in MarketScan,21,31, 32, 33 the following baseline factors affecting treatment addition were considered: (1) demographics, (2) composite index scores, including Elixhauser score34 and Claims-Based Severity Index for RA (CIRAS),35 (3) comorbidities,34,36 (4) co-medications, (5) healthcare utilization. Predisposing factors are characteristics that precede the diseases but may affect the tendency to use health services. Predisposing factors included age, gender, region, and metropolitan statistical area. Enabling factors describe one's ability to access health services and include employment status, the year of index MTX prescription, insurance plan, and physician specialty coding; the physician specialty coding was a binary variable that indicates if patients had prescription drug claims coded by specialty physicians. Need factors reflect one's actual health status that drives their need for seeking healthcare services and include Elixhauser score, CIRAS, comorbidities, co-medications, and health service utilization (number of primary care visits, pain management-related visits, any hospitalization, and emergency room visits).

Elixhauser Comorbidity index score, a composite score that summarizes the patient's comorbidity burden, was computed based on the presence of 31 comorbid conditions using published algorithms and was a continuous variable with a higher value indicating a higher comorbid burden.34 The CIRAS is a published severity index that informs the presence of lab test orders involving inflammatory markers, chemistry panels and platelet counts, rheumatoid factor, provider's visits involving rehabilitation and rheumatology visits, and diagnosis of Felty's syndrome.37 The CIRAS was a continuous variable with a higher value indicating a higher level of severity and was computed as per the above components during the 6-month baseline period using ICD-9 codes for diagnostic conditions, CPT codes, and HHCPCS codes for lab test orders from patients' administrative records. Elixhauser index-related comorbidities were identified based on the Elixhauser Comorbidity tool34; in addition, other comorbidities common in the RA cohort were considered based on published literature and included cardiovascular-related (cardiovascular diseases and hyperlipemia), musculoskeletal-related (fibromyalgia, osteoporosis, and osteoarthritis), and others (interstitial lung diseases, and hospitalized infection).36,38 All comorbid conditions were identified during the 6-month pre-index period using ICD-9-CM codes (see the supplementary eTable2 for a list of ICD-9 diagnosis codes used for the above covariate assessment involving comorbidities).

Furthermore, RA-related comedication included baseline MTX dosing and administration methods, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs), glucocorticoid injection, oral glucocorticoid, COX-2 inhibitor, and opioids. From the pharmacy claims, MTX dosage was calculated using methods described in a published study,33 and its routes of administration were captured as injectable or subcutaneous; both the dosing variables and administration method were measured before the date of the first add-on DMARD therapy. Oral glucocorticoid prescriptions included several individual medications (such as betamethasone, cortisone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, prednisone, or triamcinolone) operationalized based on the literature39 and were identified using NDC codes from pharmacy claims files. Glucocorticoid injections were captured using NDC codes (subcutaneous) and HCPCS codes (intravenous) from the pharmacy claims file. Other medications common for RA patients included NSAID, selective COX-2 inhibitors, and prescription opioids. These mentioned medications and glucocorticoid prescriptions were measured during a 6-month baseline period (see the supplementary eTable2 for a list of ICD-9 diagnosis codes used for covariate assessment).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographics and clinical characteristics of the cohort. Patient characteristics were compared by DMARD treatment addition categories using χ2 test or 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Due to the limited sample size, the addition of non-TNFi (n = 40) or tsDMARD (n = 3) was not further evaluated. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the factors influencing the prescription of a DMARD add-on prescription, adjusting for baseline covariates. The dependent variable in the model was a binary indicator for adding a TNFi as compared to adding a csDMARD. The independent variables were the predisposing, enabling, and need factors as per the ABM conceptual model. Multicollinearity was evaluated using the correlation matrix, and variables with correlation coefficients of 0.8 or higher were removed. The linearity of the continuous variables concerning the logit of the dependent variable was confirmed. Association between potential predictive factors and the choice of treatment addition were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs).

An additional analysis examining factors associated with adding a bDMARD versus a csDMARD was conducted. This involved evaluation of the factors associated with adding biologic therapy, with TNFi and non-TNFi combined, using aseparate multivariable logistic regression. All data analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).40 The significance level α was set at 0.05 with 2-tailed tests.

3. Results

3.1. Study cohort derivation

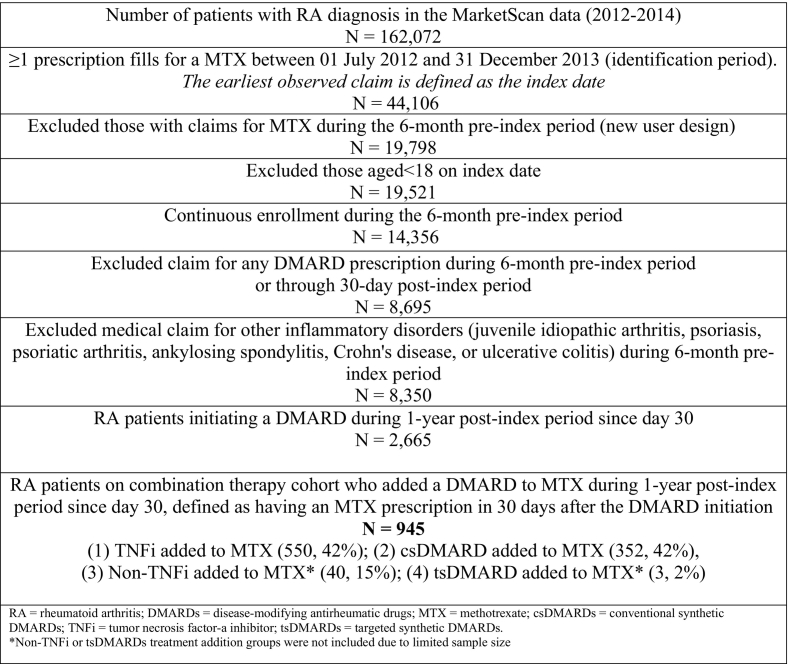

The flowchart of sample derivation is presented in Fig. 2. After all inclusion criteria, there was a total of 8350 eligible adult patients with RA and newly initiating an MTX prescription during the study identification period. Of them, 2665 (31.92%) patients initiated either another csDMARD, TNFi, non-TNFi biologic, or tsDMARD during the 1-year post-index period. Of those RA patients and initiators of any DMARD after MTX, a total of 945 (35.46%) were on the combination therapy involving the addition of a DMARD to MTX. The majority added a TNFi to MTX (n = 550, 58%), followed by the addition of a csDMARD to MTX (n = 352, 42%), and few added a non-TNFi biologic to MTX (n = 40, 4%), or a tsDMARD (n = 3, 2%). Due to the limited sample size, the addition of non-TNFi biologic was not considered for further analysis.

Fig. 2.

Study sample derivation.

3.2. Study cohort characteristics

The mean age of the entire cohort was 49 ± 10.13 years. The majority were female (78.86%), from a metropolitan statistical area (MSA) (82.91%), actively employed (82.27%), and with index MTX in 2013 (52.55%). Additionally, most of them were enrolled in a Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) (64.33%) and with a physician specialty coding flag (97.77%). Hypertension (26.86%), hyperlipidemia (20.70%), diabetes (14.76%), hypothyroidism (15.71%), depression (11.89%), chronic pulmonary diseases (12.90%), and osteoporosis (10.30%), were the most frequently occurring comorbidities. The mean Elixhauser score was 0.68 ± 3.95. The mean CIRAS was 6.84 ± 1.55. The characteristics of the entire cohort are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of RA patients Who added any DMARD to the MTX therapy, by type of add-on DMARD prescription.

| Characteristics | Overall sample (N = 942) |

First add-on DMARD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| csDMARD addition (n = 352) | TNFi addition (n = 550) | Non-TNFi addition (n = 40) | P value | ||

| No. (%) | |||||

| Predisposing factors | |||||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 49 ± 10.13 | 49.53 ± 9.78 | 48.53 ± 10.37 | 50.52 ± 9.90 | 0.22 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 218 (23.14) | 82 (23.30) | 126 (22.91) | 10 (25) | 0.95 |

| Female | 724 (78.86) | 270 (76.70) | 424 (77.09) | 30 (75) | |

| Region | |||||

| Northeast | 121 (12.85) | 47 (13.35) | 68 (12.36) | 6 (15) | 0.78 |

| North Central | 182 (18.32) | 76 (21.59) | 100,918.18) | 6 (15) | |

| South | 435 (46.18) | 158 (44.89) | 256 (48.55) | 21 (51.5) | |

| West | 204 (21.65) | 71 (20.17) | 126 (22.91) | 7 (17.50) | |

| Metropolitan statistical area | |||||

| Yes | 781 (82.91) | 281 (79.83) | 463 (84.18) | 37 (92.50) | 0.06 |

| No | 161 (17.73) | 71 (20.17) | 87 (15.82) | 3 (7.5) | |

| Enabling factors | |||||

| Employment status | |||||

| Active employed | 775 (82.27) | 288 (81.82) | 460 (83.64) | 27 (67.50) | 0.03 |

| Others1 | 167 (17.73) | 64 (18.18) | 90 (16.36) | 13 (32.50) | |

| Year of index MTX prescription | |||||

| 2012 | 447 (47.45) | 164 (46.59) | 282 (47.64) | 21 (52.50) | 0.77 |

| 2013 | 495 (52.55) | 188 (53.41) | 288 (52.36) | 19 (47.50) | |

| Plan indicator | |||||

| PPO | 606 (64.33) | 209 (59.38) | 374 (68) | 23 (57.5) | 0.02 |

| Non-PPO2 | 336 (35.67) | 143 (40.63) | 176 (32) | 17 (42.5) | |

| Physician specialty coding flag | |||||

| < 70% of outpatient physician records have specialty indicated | 21 (2.23) | 9 (2.56) | 10 (1.82) | 2 (5) | 0.37 |

| ≥ 70% of outpatient physician records have specialty indicated | 921 (97.77) | 343 (97.44) | 540 (98.18) | 38 (95) | |

| Need factors | |||||

| Elixhauser Score (mean ± SD) | 0.68 ± 3.95 | 0.74 ± 3.78 | 0.50 ± 3.87 | 2.45 ± 5.69 | 0.01 |

| Claims-based severity index for RA (CIRAS) (mean ± SD) | 6.84 ± 1.55) | 6.87 ± 1.48) | 7.04 ± 1.45) | 6.60 ± 1.71 | 0.0576 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | |||||

| Hypothyroidism | 148 (15.71) | 50 (14.20) | 94 (17.09) | 4 (10) | 0.3 |

| Diabetes | 139 (14.76) | 51 (14.49) | 83 (15.09) | 5 (12.50) | 0.89 |

| Depression | 112 (11.89) | 42 (11.39) | 64 (11.64) | 6 (15) | 0.82 |

| Anemia | |||||

| Chronic pulmonary diseases | 97 (10.30) | 30 (8.52) | 61 (11.09) | 6 (15) | 0.28 |

| Obesity | |||||

| Liver disease | 41 (4.35) | 10 (2.84) | 26 (4.73) | 5 (12.50) | 0.01 |

| RA-related comorbidities | |||||

| CV-related | |||||

| Cardiovascular diseases4 | 93 (9.87) | 35 (9.94) | 57 (10.36) | 1 (2.5) | 0.2733 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 249 (26.43) | 95 (26.99) | 147 (26.73) | 7 (17.5) | 0.4228 |

| Musculoskeletal-related | |||||

| Osteoarthritis | 323 (34.29) | 116 (32.95) | 190 (34.55) | 17 (42.5) | 0.4745 |

| Fibromyalgia | 137 (14.54) | 46 (13.07) | 80 (14.55) | 11 (27.5) | 0.0493 |

| Osteoporosis | 32 (3.4) | 13 (3.69) | 15 (2.73) | 4 (10) | 0.046 |

| Other comorbidities | |||||

| Hospitalized infection3 | 404 (42.89) | 255 (46) | 140 (39.77) | 11 (27.5) | 0.0243 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 37 (3.93) | 17 (4.83) | 14 (2.55) | 6 (15) | 0.0003 |

| Comedications | |||||

| Route of administration of last MTX prescription as oral taken method* | 883 (93.74) | 329 (93.47) | 518 (94.18) | 36 (90) | 0.55 |

| Dose of last MTX prescription of ≥25 mg/week* | 765 (81.21) | 266 (75.57) | 467 (84.91) | 32 (80) | 0.002 |

| Glucocorticoid injection | 259 (27.49) | 81 (23.01) | 166 (30.18) | 12 (30) | 0.06 |

| Oral glucocorticoid5 | 715 (75.9) | 274 (77.84) | 411 (74.73) | 30 (75) | 0.56 |

| NSAID6 | 493 (52.34) | 180 (51.14) | 296 (53.82) | 17 (42.5) | 0.33 |

| COX-2 inhibitors7 | 70 (7.43) | 19 (5.4) | 48 (8.73) | 3 (7.5) | 0.18 |

| Opioids8 | 547 (58.07) | 194 (55.11) | 326 (59.27) | 27 (67.5) | 0.22 |

| Healthcare utilization | |||||

| No of PCP visits (mean ± SD) | 10.41 ± 12.41 | 10. 86 ± 13.86 | 10.11 ± 10.90 | 10.45 ± 17.64 | 0.6782 |

| Number of Pain management-related9 (mean ± SD) | 7.93 ± 23.67 | 8.62 ± 26.33 | 7.08 ± 20.91 | 13.40 ± 32.79 | 0.21 |

| ≥1 ED visit | 175 (18.58) | 63 (17.90) | 106 (19.27) | 6 (15) | 0.73 |

| ≥1 Hospitalization | 105 (11.15) | 39 (11.08) | 59 (10.73) | 7 (17.5) | 0.42 |

RA = rheumatoid arthritis; DMARDs = disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; MTX = methotrexate; csDMARDs = conventional synthetic DMARDs; TNFi = tumor necrosis factor-a inhibitor; tsDMARDs = targeted synthetic DMARDs, SD = standard deviation; HMO = health maintenance organization; POS = point-of-service; PPO = preferred provider organization; EPO = exclusive provider organization; CDHP = consumer-directed health plan; HDHP = high deductible health plan; ED = emergency department.

Significant values at P < 0.05 are bolded.

Notes: 1 Other employment status include part-time/seasonal, early retiree, long-term disabled, etc. 2 Others plan type include HMO, POS, EPO, POS with capitation, CDHP, HDHP. 3 Hospitalized infections include bacterial, viral and opportunistic infections. 4 heart diseases include MI, stroke, heart failure, atrial filibriation, atherosclerosis. 5 Glucocorticoids include prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, or dexamethasone. 6 Non-selective NSAID include Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Celecoxib, Diclofenac, Indomethacin, Diflunisal, Salsalate, Etodolac, Sulindac, Flurbiprofen, Ketoprofen, Oxaprozin, Phenlbutazone, Piroxicam, Meloxicam, Nabumetone. 7 COX-2 inhibitors include celecoxib, rofecoxib, valdecoxib. 8 Opioids include narcotic analgesics (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, and tramadol, codeine, propoxyphene), and narcotic analgesic combinations (acetaminophen-codeine, acetaminophen-hydrocodone, acetaminophen-oxycodone, acetaminophen-propoxyphene, acetaminophen-tramadol). 9 Pain management related visits include chiropractor, pain management specialist, physical medicine &rehab, physical therapist, supportive therapist, alternative therapist, acupuncturist, and osteopathic medicine.

*Measured as the last prescription before the treatment addition of the DMARD prescription.

The comparative characteristics of patients across the addition of a csDMARD, TNFi, and non-TNFi biologics are also shown in Table 1. There were significant differences between the combination groups regarding predisposing factors (MSA) and enabling factors (employment status and insurance plan indicators). Among the need factors, significant differences in terms of Elixhauser score, RA-related comorbidities (fibromyalgia, osteoporosis, hospitalized infections, and interstitial lung diseases), and RA-related comedications (MTX dosing) between treatment addition groups were observed.

3.3. Predictors of adding the first TNFi

Table 2 shows the adjusted odds ratio of significant predictors in association with adding a TNFi vs. a csDMARD in RA. Among enabling factors, patients enrolled in a PPO were significantly associated with higher odds of adding a TNFi (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.43; 95% CI, 1.06–1.93; P = 0.0207). Of need factors, coexisting liver disease (aOR, 5.24; 95% CI, 1.77–15.49; P = 0.0027) and chronic pulmonary diseases (aOR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.14–3.44; P = 0.0159) were positively associated with prescribing a TNFi add-on therapy; conversely, one unit increase in Elixhauser comorbidity index score was significantly associated with lower odds of prescribing a TNFi add-on (aOR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86–0.97; P = 0.0028).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression of factors associated with adding a TNFi Vs. adding a csDMARD among RA patients initiating MTX.

| Characteristics | aOR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | ||

| Age, y | 0.994 (0.976–1.012) | 0.4787 |

| Sex, male vs female | 1.063 (0.756–1.494) | 0.7254 |

| Region | ||

| West | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Northeast | 0.868 (0.524–1.44) | 0.5844 |

| North Central | 0.761 (0.49–1.183) | 0.2249 |

| South | 0.854 (0.582–1.254) | 0.4219 |

| Metropolitan statistical area, yes vs no | 1.424 (0.981–2.069) | 0.0631 |

| Enabling factors | ||

| Year of index MTX prescription, 2013 vs 2012 | 0.928 (0.699–1.232) | 0.6065 |

| Physician specialty coding flag with <70% of outpatient physician records having specialty indicated, yes vs no | 1.058 (0.402–2.782) | 0.9088 |

| Employment status, active full-time vs others1 | 0.884 (0.59–1.323) | 0.5482 |

| Plan indicator: PPO vs others2 | 1.428 (1.056–1.932) | 0.0207* |

| Need factors | ||

| Elixhauser Score | 0.912 (0.858–0.969) | 0.0028* |

| CIRAS | 1.048 (0.934–1.175) | 0.4281 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 1.1 (0.774–1.563) | 0.5951 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.188 (0.798–1.769) | 0.3958 |

| Diabetes | 1.036 (0.673–1.596) | 0.8708 |

| Depression | 0.669 (0.414–1.082) | 0.1013 |

| Anemia | 1.051 (0.648–1.706) | 0.8397 |

| Chronic pulmonary diseases | 1.976 (1.136–3.437) | 0.0159* |

| Obesity | 0.676 (0.371–1.232) | 0.201 |

| Liver disease | 5.24 (1.772–15.491) | 0.0027* |

| RA-related comorbidities | ||

| CV-related | ||

| Cardiovascular diseases4 | 1.322 (0.782–2.236) | 0.2967 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.884 (0.625–1.251) | 0.4857 |

| Musculoskeletal-related | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 1.036 (0.755–1.423) | 0.8258 |

| Fibromyalgia | 1.014 (0.668–1.539) | 0.949 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.721 (0.321–1.618) | 0.4275 |

| Other comorbidities | ||

| Hospitalized infection3 | 1.317 (0.972–1.782) | 0.0752 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 0.492 (0.225–1.076) | 0.0756 |

| Comedications | ||

| Routes of administration of last MTX prescription before addition of DMARD: oral vs subcutaneous administration | 0.608 (0.158–2.339) | 0.469 |

| Dose of last MTX prescription before addition of DMARD of ≥25 mg/week vs <25 mg/week | 2.287 (0.595–8.795) | 0.2287 |

| Glucocorticoid injection, yes vs no | 1.362 (0.975–1.902) | 0.0702 |

| Oral glucocorticoid,5 yes vs no | 0.812 (0.58–1.138) | 0.2271 |

| NSAID,6 yes vs no | 1.025 (0.763–1.376) | 0.8718 |

| COX-2 inhibitor,7 yes vs no | 1.13 (0.65–1.964) | 0.6649 |

| Opioid,8 yes vs no | 1.237 (0.918–1.666) | 0.1617 |

| Healthcare utilizations | ||

| No. of PCP visits | 0.996 (0.987–1.005) | 0.416 |

| No. of pain management-related visits9 | 0.996 (0.99–1.002) | 0.2132 |

| Any ED visit, yes vs no | 0.966 (0.652–1.43) | 0.8614 |

| Any hospitalization, yes vs no | 0.891 90.539–1.473) | 0.6521 |

RA = rheumatoid arthritis; DMARD = disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug; SD = standard deviation; HMO = health maintenance organization; POS = point-of-service; PPO = preferred provider organization; EPO = exclusive provider organization; CDHP = consumer-directed health plan; HDHP = high deductible health plan; ED = emergency department.

Significant values at P < 0.05 are bolded.

Notes: 1 Other employment status include part-time/seasonal, early retiree, long-term disabled, etc. 2 Others plan type include HMO, POS, EPO, POS with capitation, CDHP, HDHP. 3 Hospitalized infections include bacterial, viral and opportunistic infections. 4 heart diseases include MI, stroke, heart failure, atrial filibriation, atherosclerosis. 5 Glucocorticoids include prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, or dexamethasone. 6 Non-selective NSAID include Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Celecoxib, Diclofenac, Indomethacin, Diflunisal, Salsalate, Etodolac, Sulindac, Flurbiprofen, Ketoprofen, Oxaprozin, Phenlbutazone, Piroxicam, Meloxicam, Nabumetone. 7 COX-2 inhibitors include celecoxib, rofecoxib, valdecoxib. 8 Opioids include narcotic analgesics (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, and tramadol, codeine, propoxyphene), and narcotic analgesic combinations (acetaminophen-codeine, acetaminophen-hydrocodone, acetaminophen-oxycodone, acetaminophen-propoxyphene, acetaminophen-tramadol). 9 Pain management related visits include chiropractor, pain management specialist, physical medicine &rehab, physical therapist, supportive therapist, alternative therapist, acupuncturist, and osteopathic medicine.

*Measured as the last prescription before the treatment addition of the DMARD prescription.

A forest plot depicting significant predictors associated with adding a biologic vs. a csDMARD in RA, presented with an adjusted odds ratio, is illustrated in Fig. 3. In the additional analysis, the findings were consistent with the primary analysis. However, it additionally found that among predisposing factors, patients located in the MSA area (aOR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.04–2.16; P = 0.031) had increased odds of being prescribed a bDMARD add-on therapy. The detailed results for additional analysis exploring factors associated with prescribing a bDMARD add-on therapy were presented in Supplementary eTable 2.

Fig. 3.

Multivariable logistic regression (additional analysis) showing significant predictors associated with adding a biologic vs adding a csDMARD among RA patients initiating MTX.

4. Discussion

Although guidelines support the combination therapy involving another DMARD added to MTX in RA,4,5 there is real-world data gap regarding treatment addition with a DMARD in RA. This study provides a real-world pattern involving the addition of different types of DMARDs following MTX initiation for RA. Importantly, it also adds knowledge about the predictors contributing to the treatment addition of a DMARD in RA. Using a commercially insured adult RA population, this study found that over one-third of RA patients initiating MTX were added to another DMARD. TNFi constitutes the most prominent option for add-on DMARD prescription among these DMARD-naïve patients with RA after MTX initiation. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the treatment addition in RA patients receiving the MTX by considering the available b/tsDMARDs and csDMARDs. Previous studies only examined the prescribing pattern of the common add-on TNFi in RA.41, 42, 43 Despite the other novel DMARD options,51, 52, 53 this study noted the low penetration rates of non-TNFi and/or tsDMARDs, which is in accordance with the previous studies,51, 52, 53 possibly due to providers' limited experience and decreased comfort towards these new alternatives.

The study also improved our understanding of contributory factors for treatment addition with a TNFi in RA. Overall, this study found that the variations in the first TNFi biologics treatment addition are driven by enabling (insurance type) and need characteristics (liver disease, chronic pulmonary disease diseases, and Elixhauser score) among new users of MTX for RA. These results provide insights into treatment addition with a TNFi biologic in RA and may have implications for improving access and quality of care for RA.

Among the enabling factors, patients enrolled in PPO health plans had higher odds of being prescribed TNFi add-on therapy. Similarly, Desai et al. found that those enrolled in health plans with better drug benefit generosity (e.g., broader coverage) were more likely to have TNFi either on monotherapy or combination therapy.21 These results potentially indicate that non-PPO insurance has less prescription coverage. In the analysis of the Medicare Part D plan's formulary, a study finds that prescription drug plans with high cost-sharing requirements for specialty drugs coverage resulted in high out-of-pocket costs for biologics and caused an excessive financial burden on patients with RA.44 Many Medicare studies suggested that there observed a delay in the treatment initiation or continuity with biologic treatment among patients with RA because of the greater cost sharing due to the high “specialty tier” of these vital therapies (i.e., biologics).45, 46, 47 To improve access to specialty pharmaceuticals, like biologics, policy options, such as out-of-pocket spending caps, value-based payment systems, and patient support programs, can be considered by stakeholders.48,49

Among the need factors, as expected, the Elixhauser comorbidity index, an indicator of comorbidity burden, was associated with lower odds of adding a TNFi. Prior observational studies also demonstrated reduced TNFi biologic utilization among real-world RA patients with multiple comorbidities.50,51 Several meta-analyses of RCT and observational studies highlighted a higher risk of adverse events in RA patients receiving TNFi, i.e., cancer or infection.14., 15, 16 For safety concerns, clinicians may avoid prescribing a TNFi biologic in these RA patients with multiple comorbidities. In addition, the EULAR guidelines reported that common comorbidities (infections, CVD, malignancy, gastrointestinal disease, osteoporosis, and depression) were seen in RA patients.38 As such, some RA patients may already be simultaneously exposed to more than one medication for underlying comorbidities, and therefore physicians are less likely to prescribe TNFi biologics as an add-on concerning the increased potential for drug-drug interactions between the use of the TNFi biologics and other medications.

Among the need factors, both liver disease and chronic pulmonary diseases were positively associated with adding a TNFi biologic. Trial data has confirmed that treatment with TNFi alone or combined with MTX, is efficacious in reducing the disease activity score and improving functional disability among RA patients with worsening hepatitis-C virus.52 Indeed, the biological mechanism behind the use of TNF-α in mediating liver inflammation is that the TNF-α pathway is believed to be involved in liver steatosis and hepatic inflammation underlying the development of HCV.53 Further, a previous observational study found no increased risk of adverse respiratory events with biologic DMARDs compared to csDMARD in RA and thus supporting the current findings regarding the higher utilization of TNFi in the RA population with chronic pulmonary diseases.54

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This large cohort study found that the variation in the treatment addition with the first TNFi biologic for RA population is mainly driven by the enabling factor of insurance type as well as certain clinically relevant need characteristics. There are several strengths of the current commercial claims-based study. First, this study used the MarketScan data involving a large cohort of commercially insured RA patients that is highly generalizable. Second, thisstudy improved our understanding regarding treatment addition of DMARDs following initiating MTX in RA. Another strength is using a conceptual framework in examining the factors associated with prescribing a DMARD add-on therapy. In addition, this study included a validated CIRAS as a surrogate marker to adjust for baseline RA severity measures; the CIRAS has the potential to be used for future observational pharmacoepidemiology studies related to RA. Overall, the current study provides real-world insights into DMARD treatment addition patterns in RA using multi-year nationwide administrative data

The study findings should be interpreted in consideration of some limitations. Most limitations are due to the nature of the claims data source. First, the MarketScan data is insurance claims data; using ICD-9-codes and other coding systems in claims data may cause some misclassification. However, this concern is minimized by involving an MTX prescription from pharmacy claims to augment coded information from claims data. Also, as claims data is used for billing purposes, some key clinical information like lab-related (rheumatoid factor (seronegative/seropositive)), procedure-related (imaging tests or ultrasound), or patient-reported measures (swollen joint counts) were lacking. The availability of these data could strengthen the current findings; however, this study used a validated severity index as a proxy for RA disease severity.37 Furthermore, MarketScan only includes data from employers in the US; thus, the results may not be generalizable to all RA patients(e.g., those with Medicaid or uninsured patients). In addition, race, education, income, nonprescription drug use, and patient preference were unavailable; therefore, this study cannot explain potential variation due to these factors. Lastly, the study evaluated factors associated with the addition of a DMARD in RA patients initiating MTX by considering all available DMARD options; however, the size of patients added non-TNF biologics or tsDMARDs made it difficult to consider the relevant patient groups. Future studies using more recent data are needed to evaluate various combinations involving the addition of tsDMARD or non-TNFi biologics.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in this large cohort of patients with RA starting MTX, the study found that the TNFi biologic is often added to MTX for managing RA. Besides clinically relevant need characteristics (liver disease, chronic pulmonary disease diseases, and Elixhauser score), the enabling factor of insurance plan type also drives the first TNFi biologic treatment addition in RA. Results provide insights into real-world patterns of treatment addition with a TNFi biologic in RA and potentially indicate variations in treatment addition with TNFi biologics compared with comparator csDMARD. Findings can have important implications for improving access and quality of RA care, with possible strategies addressing the variation in the use of TNFi. Future research should evaluate the impact of the variation in the use of TNFi biologics in RA on patients' health outcomes.

Ethics approval and consent to participant

The study was approved by the University of Houston Institutional Review Board.

Disclosures

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Dr. Rajender R. Aparasu reports grants from Astellas, Incyte, and Novartis, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no personal or financial conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

We have no founding support regarding this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr. Rajender R. Aparasu reports grants from Astellas, Incyte, Gilead, and Novartis, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no personal or financial conflicts of interest to report.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsop.2023.100296.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

: Supplementary eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Diagnosis Codes Used to Identify the Comorbidities Excluded in the Cohort Derivation or Covariate Assessment.

Supplementary eTable 2. Detailed Results for Additional Analysis of Multivariable Logistic Regression of Factors Associated With Adding a Biologic vs. a csDMARD.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Smolen J.S., Aletaha D., McInnes I.B. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2023–2038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aletaha D., Smolen J.S. Diagnosis and management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: a review. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1360–1372. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter T.M., Boytsov N.N., Zhang X., Schroeder K., Michaud K., Araujo A.B. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States adult population in healthcare claims databases, 2004–2014. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(9):1551–1557. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3726-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraenkel L., Bathon J.M., England B.R., et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021;73(7):924–939. doi: 10.1002/acr.24596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolen J.S., Landewé R.B.M., Bijlsma J.W.J., et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):S685–S699. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sergeant J.C., Hyrich K.L., Anderson J., et al. Prediction of primary non-response to methotrexate therapy using demographic, clinical and psychosocial variables: results from the UK rheumatoid arthritis medication study (RAMS) Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1645-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albrecht K., Zink A. Poor prognostic factors guiding treatment decisions in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a review of data from randomized clinical trials and cohort studies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baganz L., Richter A., Albrecht K., et al. Are prognostic factors adequately selected to guide treatment decisions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? A collaborative analysis from three observational cohorts. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48(6):976–982. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis J.R., Palmer J.L., Reed G.W., et al. Real-world outcomes associated with methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine triple therapy versus tumor necrosis factor inhibitor/methotrexate combination therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021;73(8):1114–1124. doi: 10.1002/acr.24253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sauer B.C., Teng C.C., Tang D., et al. Persistence with conventional triple therapy versus a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor and methotrexate in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69(3):313–322. doi: 10.1002/acr.22944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergstra S.A., Winchow L.L., Murphy E., et al. How to treat patients with rheumatoid arthritis when methotrexate has failed? The use of a multiple propensity score to adjust for confounding by indication in observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(1):25–30. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Dell J.R., Mikuls T.R., Taylor T.H., et al. Therapies for active rheumatoid arthritis after methotrexate failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(4):307–318. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1303006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bansback N., Phibbs C., Sun H., et al. Triple therapy versus biologic therapy for active rheumatoid arthritis a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):8–16. doi: 10.7326/M16-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez-Olivo M.A., Tayar J.H., Martinez-Lopez J.A., et al. Risk of malignancies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic therapy A meta-analysis. 2023. www.jama.com [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Singh J.A. Infections with biologics in rheumatoid arthritis and related conditions: a scoping review of serious or hospitalized infections in observational studies. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18(10) doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nannini C., Cantini F., Niccoli L., et al. Single-center series and systematic review of randomized controlled trials of malignancies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy: is there a need for more comprehensive screening procedures? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2009;61(6):801–812. doi: 10.1002/art.24506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Y., Desai R.J., Liu J., Choi N.K., Kim S.C. Factors associated with initial or subsequent choice of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim G., Barner J.C., Rascati K., Richards K. Factors associated with the initiation of biologic disease-modifying Antirheumatic drugs in Texas Medicaid patients with rheumatoid. Arthritis. 2015;21 doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.5.401. www.amcp.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George M.D., Sauer B.C., Teng C.C., et al. Biologic and glucocorticoid use after methotrexate initiation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(4):343–350. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu L.H., Portugal C., Kawatkar A.A., Stohl W., Nichol M.B. Racial/ethnic differences in the use of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs among California Medicaid rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65(2):299–303. doi: 10.1002/acr.21798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai R.J., Rao J.K., Hansen R.A., Maciejewski M.L., Farley J.F. Predictors of treatment initiation with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid. Arthritis. 2014;20 doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.11.1110. www.amcp.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yelin E., Tonner C., Kim S.C., et al. Sociodemographic, disease, health system, and contextual factors affecting the initiation of biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(7):980–989. doi: 10.1002/acr.22244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeWitt E.M., Lin L., Glick H.A., Anstrom K.J., Schulman K.A., Reed S.D. Pattern and predictors of the initiation of biologic agents for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States: an analysis using a large observational data bank. Clin Ther. 2009;31(8):1871–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.STROBE statement-checklist of items that should be included in reports of Cohort Studies. 2023. http://www.epidem.com/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.IBM MarketScan research databases for life sciences researchers. 2023. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-

- 26.Health Analytics T, IBM Company An . 2016. 2016 MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Users Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S.V., Pinheiro S., Hua W., et al. STaRT-RWE: structured template for planning and reporting on the implementation of real world evidence studies. BMJ. 2021:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonafede M., Johnson B.H., Tang D.H., Shah N., Harrison D.J., Collier D.H. Etanercept-methotrexate combination therapy initiators have greater adherence and persistence than triple therapy initiators with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67(12):1656–1663. doi: 10.1002/acr.22638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tkacz J., Gharaibeh M., Kathryn, et al. Vol. 26. 2020. Treatment patterns and costs in biologic DMARD-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis initiating etanercept or adalimumab with or without methotrexate.www.jmcp.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babitsch B., Gohl D., von Lengerke T. Vol 9. 2012. Re-revisiting Andersen’s behavioral model of health services use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011 Das Verhaltensmodell Der Inanspruchnahme Gesundheitsbezogener the retrieved articles for possible inclusion using a three-step selection process (1. Title/Author, 2. Abstract, 3. Full Text) with Pre-Defined Inclusion OPEN ACCESS. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandran U., Reps J., Stang P.E., Ryan P.B. Inferring disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis using predictive modeling in administrative claims databases. PloS One. 2019;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Best J.H., Kong A.M., Lenhart G.M., Sarsour K., Stott-Miller M., Hwang Y. Association between glucocorticoid exposure and healthcare expenditures for potential glucocorticoid-related adverse events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45(3):320–328. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng B., Chu A. Factors associated with methotrexate dosing and therapeutic decisions in veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33(1):21–30. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menendez M.E., Neuhaus V., van Dijk C.N., Ring D. The Elixhauser comorbidity method outperforms the Charlson index in predicting inpatient death after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(9):2878–2886. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3686-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ting G., Schneeweiss S., Scranton R., et al. Development of a health care utilisation data-based index for rheumatoid arthritis severity: a preliminary study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(4) doi: 10.1186/ar2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dougados M., Soubrier M., Antunez A., et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis and evaluation of their monitoring: results of an international, cross-sectional study (COMORA) Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):62–68. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ting G., Schneeweiss S., Scranton R., et al. Development of a health care utilisation data-based index for rheumatoid arthritis severity: a preliminary study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(4) doi: 10.1186/ar2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baillet A., Gossec L., Carmona L., et al. Points to consider for reporting, screening for and preventing selected comorbidities in chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases in daily practice: a EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):965–973. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jessica Gale, Jenny Wilson, Huong Chia, et al. Risk associated with cumulative oral glucocorticoid use in patients with giant cell arteritis in real-world Databases from the USA and UK. Rheumatol Ther. 2023;5 doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.6159410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.SAS ® 9.4 System Options: Reference, Fifth Edition SAS ® Documentation. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tkacz J., Gharaibeh M., Kathryn, et al. Vol. 26. 2020. Treatment patterns and costs in biologic DMARD-Naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis initiating Etanercept or Adalimumab with or without methotrexate.www.jmcp.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reed Robert A., Ying Gerber, Liza Shan, et al. 2023. Real-world comparative effectiveness of tofacitinib and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors as monotherapy and combination therapy for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J., Xie F., Delzell E., et al. Impact of biologic agents with and without concomitant methotrexate and at reduced doses in older rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67(5):624–632. doi: 10.1002/acr.22510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yazdany J., Dudley R.A., Chen R., Lin G.A., Tseng C.W. Coverage for high-cost specialty drugs for rheumatoid arthritis in medicare part D. Arthritis Rheum. 2015;67(6):1474–1480. doi: 10.1002/art.39079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doshi J.A., Hu T., Li P., Pettit A.R., Yu X., Blum M. Specialty tier-level cost sharing and biologic agent use in the Medicare part D initial coverage period among beneficiaries with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68(11):1624–1630. doi: 10.1002/acr.22880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li P., Hu T., Yu X., et al. Impact of cost-sharing increases on continuity of specialty drug use: a quasi-experimental study. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:2735–2757. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karaca-Mandic P., Joyce G.F., Goldman D.P., Laouri M. Cost sharing, family health care burden, and the use of specialty drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(5 PART 1):1227–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abbott K., Shao H., Shi L. Policy options for addressing the high cost of specialty pharmaceuticals. Glob Health J. 2019;3(4):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2019.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yeung K., Barthold D., Dusetzina S.B., Basu A. Patient and plan spending after state specialty-drug out-of-pocket spending caps. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):558–566. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa1910366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armagan B., Sari A., Erden A., et al. Starting of biological disease modifying antirheumatic drugs may be postponed in rheumatoid arthritis patients with multimorbidity. Medicine (United States) 2018;97(13) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radner H., Yoshida K., Hmamouchi I., Dougados M., Smolen J.S., Solomon D.H. Treatment patterns of multimorbid patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from an international cross-sectional study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(7):1099–1104. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iannone F., la Montagna G., Bagnato G., Gremese E., Giardina A., Lapadula G. Safety of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and hepatitis C virus infection: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(2):286–292. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wandrer F., Liebig S., Marhenke S., et al. TNF-Receptor-1 inhibition reduces liver steatosis, hepatocellular injury and fibrosis in NAFLD mice. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(3) doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2411-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hudson M., Dell’Aniello S., Shen S., Simon T.A., Ernst P., Suissa S. Comparative safety of biologic versus conventional synthetic DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis with COPD: a real-world population study. Rheumatology (United Kingdom) 2020;59(4):820–827. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

: Supplementary eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Diagnosis Codes Used to Identify the Comorbidities Excluded in the Cohort Derivation or Covariate Assessment.

Supplementary eTable 2. Detailed Results for Additional Analysis of Multivariable Logistic Regression of Factors Associated With Adding a Biologic vs. a csDMARD.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.