Abstract

The lives and livelihoods of farming and fishing communities in rural Tanzania are highly susceptible to extractive investment operations. Livelihood diversification in communities beyond agriculture and fishing can be an effective way to cope with the adverse impacts of extractive investment operations. Gas extraction operations (GEOs) are expected to change and diversify communities’ livelihoods. Tanzania has new GEOs; thus, it is necessary to investigate how they have diversified livelihoods in Mtwara Rural District. This article addresses the associations between GEOs and diversifying livelihoods. The paper explores (i) livelihood diversification before and during GEOs, (ii) associations between GEOs and villagers' livelihoods diversification, and (iii) communities' perspectives on GEOs and livelihood diversification. Proportionate stratified sampling was used to obtain 260 respondents. A questionnaire-based survey, four (4) Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), and fifteen (15) Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) were used to collect data. IBM-SPSS version 25 was used to analyse quantitative data. The Chi-square test was employed to analyse livelihood diversification concerning GEOs. Content analysis was used for qualitative data. Near and distant communities saw farming decline by 81.5% and 83.5%, respectively. Also, fishing declined by 85.2% and 83.7%. On the other hand, GEOs enhanced motorbike transport by 160.0% and 300.0%, food vending improved by 166.7% and 236.4%, and seashell collection increased by 816.0% and 462.5%, respectively. GEOs diversified farming (p = 0.001), fishing (p = 0.008), agricultural wage labour (p = 0.000), and crop business (p = 0.036) with moderate strength of association. GEOs have diversified livelihoods in the study area. The study demonstrates that communities surrounding GEOs are highly socioeconomically vulnerable due to GEOs which caused declining agricultural and fish catches, thus negatively affecting their livelihoods. It is recommended that long-term programmes such as the building of diverse agro-based enterprises for job creation, training on income-generating occupations, agribusiness and technical training are required to increase earnings and enhance living standards. Both public and private entities should conduct a targeted and context-specific initiative to increase livelihood diversification among nearby and distant households, which can improve livelihood resilience.

Keywords: Livelihoods, Livelihood diversification, Gas extraction operations, Rhetoric and reality, Mtwara rural district

1. Introduction

1.1. Background information

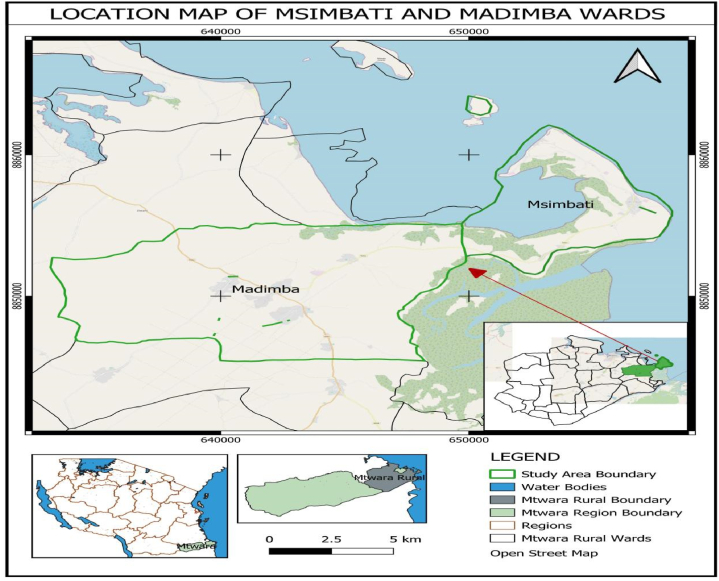

In emerging nations, livelihood diversification (LD) is essential for fostering economic development and eradicating rural poverty [1]. To survive and raise living standards, it is necessary to merge agricultural and non-agricultural industries [2,3]. Households around the developing world are attempting to diversify their sources of income to protect themselves from dangers and adapt to environmental and economic shocks [4,5]. LD is essential to the eradication of rural poverty and sustainable ecological development by offering non-farm job options [6] (see Fig. 1).

Figure (1).

A Map showing the study area location.

[7] reported that Russia, India, China, and South Africa had high levels of extractive investment. Enhanced resource extraction at the community level has had numerous and complicated social, political, and economic implications for global and local actors. In Africa, resource-rich nations face difficulty managing their natural resources because of persistent poverty and material squalor. As a result, their natural resources can be called a burden [8,9]. Poor governance structures and mechanisms are cited as the key reason for the problems in developing extractive resources [[10], [11], [12]].

Operations for extracting gas have started to endanger natural life and livelihood systems [[13], [14], [15]]. Local communities in the south-eastern regions are implementing both on-farm (planting crops that can withstand drought and selling crops like cashew nuts) and off-farm (selling household assets and land, relocating entire households, and reducing food consumption or changing diets) diversification strategies to deal with the changing situation. Likewise, livelihood diversification helps communities to control risk and improve their quality of life [4,16,17]. Theoretically, using natural resources like gas should encourage development by expanding employment, economic growth, and public services, improving the quality of life in nearby areas [13]. Gas production is a worthwhile investment because it expands possible livelihoods and lowers energy costs. However, this depends on several reasons, including government difficulties [9]. Others worry about the implications of a rapid economic expansion on community livelihood habits [15,17]. The livelihoods of the locals in the vicinity of large gas extraction projects are expected to be affected in a complex and wide-ranging manner. Extractive investment operations can damage a community's livelihood, according to Ref. [18].

In addition to the perceived vulnerability of indigenous people, their livelihoods, and their land, GEOs are a global concern [19]. Overall, society has high expectations for extractive operations, whether they are rhetorical or real. Corporate and government policies on resource extraction have evolved in reaction to criticism of prior techniques and the impact of environmental and indigenous movements [20]. However, gas extraction investments severely disadvantage local communities’ livelihoods [21]. This horrifying reality served as the motivation for this empirical study to ascertain how gas extraction operations affect the livelihoods of local residents.

Livelihood diversification is defined as a process by which household members construct a diverse portfolio of activities and social support capabilities in their struggle for survival and to improve their standards of living [22]. Therefore, in this study, “livelihood diversification” refers to households' efforts to discover new revenue streams and lessen their vulnerability to a variety of livelihood shocks. Agriculture-related diversification's, such as growing multiple crops or high-value crops, as well as non-agricultural diversification's, such as starting small businesses, depending on migration, or using temporary workers, are all examples of ways to diversify livelihoods.

Despite contributing minimally to global emissions, Tanzania is predicted to experience the negative effects of an extractive investment in terms of the changing environment [23]. Communities in the country's southeast are compelled to change or diversify their farming and fishing practices to counter risks from gas extraction projects [24]. However, a number of extraction processes, including hydraulic fracturing, horizontal drilling, and vertical drilling, pose serious risks to their lives and way of life [[25], [26], [27], [28]]. Their livelihoods are threatened by the tremendous loss of arable land and harm to other natural resources, such as freshwater estuaries, grasslands, woods, and fishing grounds, which they encounter every year [29]. To lessen loss from farming and fishing activities, they have been using both non-farm adaptation strategies (wage employment, short-term migration, tertiary occupations, [30].

According to Ref. [13], social, economic, and government policy differences cause livelihood uncertainty. These changes influence livelihood diversification based on seasons and regions, resulting in a combination of many household professions [31]. Diversifying livelihoods involves managing many assets [32]. In addition, environmental and socio-economic conditions affect household livelihood [33]. For better or worse, gas development and extraction could change local communities' livelihoods [15]. Gas extraction in rural areas is a significant source of income and livelihood for low-income rural people [[34], [35], [36]]. A household's subsistence capital is usually considered when selecting the appropriate subsistence pattern and risk. Local communities must diversify their livelihoods to succeed. These households' livelihoods determine their well-being [37]. In recent years, studies of the link between household subsistence activities and extractive investments have gained traction [[38], [39], [40], [41]]. Diversifying local communities' livelihoods helps them adjust to outside disturbances, eradicates poverty, and enhances livelihood results [20,[42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. The responses of rural farmers and fishermen to the risks associated with extractive investment were the focus of some studies [17], but the connections between rural households' efforts in changing their livelihood strategies under the immediate impacts of gas extraction operations have largely gone unappreciated.

Tanzania is experiencing new petroleum extraction operations in Mtwara and Lindi; it is essential to understand how they have affected rural communities in the Mtwara Rural District. Since gas exploration was first introduced into the United Republic of Tanzania in 1952, the first natural gas discovery was made in 1974 at Songosongo Island in the Lindi region of Tanzania, followed by the second discovery at Mnazi Bay in the Mtwara region in 1982 [47]. Evidence on record shows that commercial production of natural gas at Songosongo started in 2004, followed by Mnazi Bay in 2006 [48]. Both offshore and onshore gas extracted at Songosongo Island is transported to the Dar es Salaam Region through a pipeline [47,[49], [50], [51], [52]]. These discoveries affected the livelihoods of adjacent gas-producing settlements immediately. Residents are agents of the gas infrastructure [47,53] and are exposed to the gas project's consequences on health, safety, the environment, livelihoods, and social ties [[54], [55], [56]]. Despite continued GEOs, there is an opportunity for livelihood and diversification, but the extent of this must be empirically determined. Residents of Mtwara Rural District rely on natural resources, notably land for agriculture and the Indian Ocean for fishing. Given the new GEOs in the area, how their livelihood has diversified is an essential research topic.

Some studies that have been conducted in Tanzania argue that there are discrepancies between rhetoric and reality regarding the sharing of the benefits of GEOs on communities' development [56,57]. Given the erratic participation of the government and gas companies in the local communities, it is important that they set realistic expectations [57]. explored natural gas extraction and community development in Tanzania [58]. investigated the extraction of natural gas and the gendered distribution of benefits among host communities in Tanzania's Kilwa District [48]. explored the local content requirements in the petroleum sector in Tanzania: a thorny road from inception to implementation. Gas development operations have contradicted policy, local community expectations, and household perceptions in many ways. These investigations could not link gas extraction to livelihood diversification. Given the local content policy challenges (such as whether control or adaptation-oriented policies should be used), investigating the proactive diversification of rural farmers' and fishers' livelihoods is crucial for the long-term development of Mtwara's rural communities [59].

Though a number of studies have been found on the gas extraction investments of Mtwara Rural District in Tanzania (for example [56,57,[60], [61], [62]], issues related to the association between GEOs and livelihood diversification among communities in near and distant villages to GEOs are still overlooked. Since the livelihood diversification of nearby villages changes with gas extraction operations, it is important for policy intervention in order to enhance the community's livelihood resilience. Therefore, the main goal of this study is to explore how communities in Tanzania's Mtwara Rural District have altered and varied their means of subsistence to cope with ongoing GEOs and to offer helpful insight into sustainable extractive risk reduction techniques. This study examined the association between gas extraction operations and livelihood diversification's among communities residing in nearby and distant villages.

1.2. Theoretical framework

The study takes into account two theories (i) the household economic theory [63] and (ii) the Diversification theory that helps with livelihood diversification.

1.2.1. The household economic theory [63]

Farm households are the most productive production units, according to the main tenet of the household economic theory applied in this study. This is predicated on the notion that using time and other inputs might result in outputs that are subject to resource and budgetary constraints. The theory supports judgement involving the study of domestic production and the division of labour off-farm [[64], [65], [66]]. This theory served as the basis for the study's research of the diversification of sources of income in rural Tanzania, specifically in relation to gas extraction operations (GEOs). The theory was applied to examine the relationships between GEOs and villagers' diversification of livelihoods as well as the diversification of livelihoods in the research area. A further assumption made by the study's application of the livelihood approach theory is that a person's or a household's capacity to earn a living depends on their access to, and capacity for, the use of, their resources. The idea was employed to define livelihood diversification and investigate its advantages in reducing risks, stabilising income flow, and promoting wealth accumulation and food security. In general, the study objectives, data collecting, and data analysis were guided by the assumptions of the theories employed in this study to investigate the relationships between GEOs and livelihood diversification in rural Tanzania. As a result, in this study, “livelihood diversification” refers to people's efforts to increase their incomes and lessen their exposure to various livelihood shocks resulting from gas extraction operations on an individual and household level.

1.2.2. The diversification theory

Economist Albert O. Hirschman created the diversification theory in the 1950s. The diversification theory seeks to explain how rural households deal with environmental hazards and uncertainties by engaging in a variety of extracurricular activities and income-generating tactics. According to this idea, household well-being can be increased by reducing their sensitivity to shocks like crop failures, price changes, and natural disasters by diversifying their sources of income. According to the diversification principle, households with a variety of income sources are better equipped to weather shocks and gradually build up their overall wealth and net worth. According to this hypothesis, diversification can increase household welfare and food security since households will have more access to resources and income from a wider range of sources. The diversification theory was utilised in this study to investigate the degree to which households close to gas extraction activities areas diversified their income sources and how diversification affected the outcomes of their means of subsistence. According to the study, those that engaged in diversification experienced greater income levels and better livelihood outcomes than households that did not. The survey also discovered that households engaged in a range of non-farm activities like; seashell collections, motorbike transport, food vending and small-scale trading in addition to farming and fishing to diversify their sources of income. Overall, the study employed the idea of diversification to comprehend the significance of diversification as a means of subsistence for households located close to locations where gas extraction operations are conducted. The theory was helpful in highlighting the advantages of diversity for the welfare of households and in identifying the numerous income-generating activities that households engaged in to diversify their income.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study area

A study was conducted in the Mtwara Rural District, one of southeast Tanzania's seven districts that make up the Mtwara Region. The district is between 10° 00′ and 10° 07′ south of the equator and between 39° 00′ and 40° 27′ east of Greenwich. The Indian Ocean, Lindi Region, and Ruvuma Region are all about it on its eastern, northern, and western edges, respectively. Mtwara District, which includes Nanyamba Town Council, has a total area of 3597 square kilometers [67,68]. Gas reserves in the Mtwara Region and Mtwara Rural District at MnaziBay are significantly larger, totaling more than 5 trillion cubic feet (TCF), compared to other areas such as the Mkuranga district, which have 0.2 TCF; Kiliwani, 0.07 TCF; Ntorya, 0.178 TCF); Songosongo, 2.5 TCF; and deep sea, with 42.28 TCF, in Tanzania [69,70]. Additionally, gas extraction operations are continuing [47,71]. The reason for choosing the study area is the presence of a large gas reservoir compared to other parts of Tanzania discovered so far. The villages of Msimbati, Mtandi, Namindondi, and Mngoji were included in the study (see Fig. 1).

2.2. Data collection

A cross-sectional research design was used for the study, which was carried out between July and December 2020. The unit of analysis was a household, and the survey asked the heads of households to take part. The houses in Msimbati, Mtandi, Namindondi, and Mngoji villages were chosen based on their closeness to the gas extraction processing plant and gas fields. To determine all the parameters, the International Oil and Gas Companies (IOC) built the distance cut-off points based on Hazop or the operability of the ground or the plant [72]. This investigation used a multi-stage sampling method, with several phases leading up to stratified proportionate sampling. As such, a proportional random sampling technique yielded 120 households in the nearby villages of Namindondi and Mngoji and 140 households in the distant villages of Msimbati and Mtandi in the Mtwara Rural District. After collecting the whole sample from each ward, the village proportion was computed using a proportionate sampling approach, as detailed in Ref. [73].

2.2.1. Population and sampling procedure

This study chose four (4) villages from the two-ward based on their proximity to GEOs at the point in time when data was gathered. The number of households in total in the research areas was 802. The multistage sampling approach was used to determine the study's samples. The study sample was calculated using the formula below.

where n is the sample size, N is the number of households from the four villages totaling 802, e = 5% (0.05) precision, p = sample proportion, q = 1-p, and z = the value of a specified confidence level.

The study then used proportionate stratified random sampling:

(N)

Where:

nh = Sample size for hth stratum.

Nh = Population size for hth stratum.

N = Size of the entire population

n = Size of the entire sample.

In addition, 15 key informant interviews (KIIs) comprising 2 Ward Executive Officers (WEOs), 4 Villages Executive Officers (VEOs), 1 District Planning Officer (DPLO), 1 District Statistician, 2 Community Development Officers (CDOs), 2 Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) and 3 Gas Investors; were chosen purposively due to their positions, knowledge and experience in GEOs and livelihood transformation and diversification pattern in the study area using a checklist of topics for discussion.

The study used a questionnaire to survey households. Semi-structured interviews with village leaders and authorities supplemented the primary data. In the four villages with gas infrastructure (gas wells and gas processing plants), key informant interviews with 15 people with knowledge of local communities' livelihoods, livelihood dynamics, and transition were conducted in addition to four gender-specific focus group discussions (one FGD per village) with 8 participants. Elderly and young FGD participants explained how GEOs had transformed and diversified their lives. Using a purposeful sampling technique, respondent households were chosen who reported engaging in formal employment, farming, fishing, selling crop products, petty trade, and other activities. FGDs tested patterns and drivers of livelihood diversification near gas extraction operations by finding (a) significant changes in livelihood before and after GEOs, (b) associations between gas extraction operations, and (c) residents' perceptions of gas extraction operations in the area. After getting participants' consent, KIIs and FGDs were recorded on digital audio recorders.

2.3. Data analysis

The study used frequency and percentages to test independence. Villages around gas fields and processing plants have different lifestyle patterns before and after gas extraction began. The significance of the link was tested using the chi-square test, and the primary livelihood pattern and association strength were estimated using phi-statistics in IBM-SPSS version 25. The distance from home to gas extraction operations and significant livelihood patterns approved the independence T-test. Data that was qualitative and categorical was analyzed using content analysis. Key phrases and segments were retrieved, translated, and analyzed based on patterns discovered while reading FGD and KII transcripts frequently. After being translated into Kiswahili, the transcripts were linked with field information to uncover relevant trends. Transcripts were coded by their topics and themes. These techniques were provided by Ref. [74] to connect and analyse the major themes of the study (see Table A1).

Table (A.1).

Sample distribution for the study among villages in the study area.

| Ward Msimbati |

Village names Distant Village |

Total Households | Sampled households | Per cent (%) |

| Msimbati | 225 | 73 | 28.2 | |

| Mtandi | 206 | 67 | 25.7 | |

| Madimba | Near villages | |||

| Namindondi | 197 | 64 | 24.5 | |

| Mngoji | 172 | 56 | 21.6 | |

| Total | Four villages | 802 | 260 | 100.0 |

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Characteristics of surveyed households

Table (A2) presents the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics. The average household size was 6.2, which is higher than the national average in Tanzania, which is 4.8 [75]. Results in Table (A2) revealed that the highest group, 33.8% (95% CI: 0.102,0.100), was between 31 and 40 years old, and the lowest group, which formed 5.0% (95% CI: 0.343,0.344), was above 60 years old. The average age was 44.4 years, ranging from 19 to 72, with 19 being the youngest and 72 being the oldest. This suggests that most respondents were middle-aged and active in diversifying their livelihood activities. This implies that the majority of the population is middle-aged, and they are capable of engaging themselves in other livelihood activities to cope with the shocks brought by GEOs compared to those aged above 60 years old.

Table (A.2).

Characteristics of respondents in Mtwara rural district (n = 260).

| Household characteristics | Total | Per cent (%) | 95.0% Confidence Interval for near and distant villages |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| (Constant) | −.430 | .453 | ||

| Sex of the household head | ||||

| Male | 148 | 56.9 | .116 | .274 |

| Female | 112 | 43.1 | .580 | 1.028 |

| Age of the household head | ||||

| 19–31 | 26 | 10 | −.343 | .345 |

| 31–40 | 88 | 33.8 | −.102 | .100 |

| 41–50 | 72 | 27.7 | −.155 | .160 |

| 51–60 | 61 | 23.5 | −.334 | .331 |

| Above 60 | 13 | 5 | −.343 | .344 |

| Average Household size | 6.2 | −.009 | .009 | |

| The average age of household heads | 44.4 | |||

| Level of education of the household head | ||||

| Non-formal education | 60 | 23.1 | −.311 | .317 |

| Primary | 174 | 66.9 | −.312 | .314 |

| Secondary | 20 | 7.7 | −.384 | .370 |

| Vocational | 4 | 1.5 | −.427 | .447 |

| University | 2 | 0.8 | −.376 | .376 |

| Marital status of the household head | ||||

| Single | 22 | 8.5 | −.263 | .274 |

| Married | 175 | 67.3 | −.311 | .307 |

| Divorced | 19 | 7.3 | −.372 | .382 |

| Separated | 14 | 5.4 | −.435 | .435 |

| Widow/Widower | 30 | 11.5 | −.186 | .187 |

Table (A2) shows that 56.9% (95% CI: 0.116, 0.274) of respondents were male and 43.1% (95% CI: 0.580, 1.028) of households were female. Regarding marital status, 67.3% of 95% (CI: 0.311, 0.307) of Table (A2) shows the married household heads and the rest of the household members' marital statuses. About one-fourth, 23.1% (95% CI: 0.311, 0.317) of the household heads had no formal education, whereas 66.9% (95% CI: 0.312, 0.314) had primary education, and 7.7% (95% CI: 0.384, 0.370) had secondary education. The result revealed that the mean years of schooling were 5.6 years (95% CI: 0.007, 004).

3.2. Livelihood diversification before and during gas extraction operations

Table (A3) presents the livelihood and diversification before and during GEOs by categorizing them into those previously done and whose undertaking was diversified and those previously not there but emerged after the gas extraction operations. Table (A3) shows that farming and fishing were the primary financial activities for households in the study area before gas extraction operations. The findings in Table (A3) prove that the household heads' occupation at 42.3% (95% CI: 0.226, 0.231) was farming, followed by crop selling at 25.8% as observed at 95% CI: 0.189, 0.184) and seashell collection at 10.4% (95% CI: 0.358, 0.352). Other occupations involved a few household heads, as seen in Table (A3).

Table (A.3).

Livelihood diversification before and during gas extraction operations in Mtwara Rural District (n = 260).

|

Livelihood Strategy |

Near Villages |

95.0% Confidence Interval for %change of Near |

Distant Villages |

95.0% Confidence Interval for % change of distant |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | During | Change (±) (%) |

Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Before | During | Change (±) (%) |

Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Farming | 97 | 18 | −79 | −81.4 | .144 | .492 | 123 | 22 | −111 | −83.5 | .092 | .431 |

| Fishing | 81 | 12 | −69 | −85.2 | .074 | .345 | 116 | 19 | −97 | −83.7 | .100 | .364 |

| Salaried work | 9 | 8 | −1 | −11.1 | −.044 | .347 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0.0 | −.071 | .309 |

| Investor farm wage | 9 | 6 | −3 | −33.3 | −.097 | .330 | 12 | 11 | −1 | −8.3 | −.031 | .385 |

| Farm wage | 11 | 7 | −4 | −36.4 | .213 | .500 | 40 | 17 | −23 | −57.5 | .241 | .520 |

| Carpentry | 4 | 6 | 2 | 50.0 | −.079 | .403 | 12 | 25 | 13 | 108.3 | −.080 | .389 |

| Making bricks | 4 | 7 | 3 | 75.0 | .055 | .513 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 0.0 | .008 | .454 |

| Bicycle repair | 7 | 8 | 1 | 14.3 | −.114 | .311 | 14 | 26 | 12 | 85.8 | −.040 | .374 |

| Motor-bike | 5 | 13 | 8 | 160.0 | −.183 | .323 | 9 | 36 | 27 | 300.0 | −.132 | .360 |

| Sea-shell collection | 6 | 55 | 49 | 816.7 | −.118 | .392 | 16 | 90 | 74 | 462.5 | −.149 | .347 |

| Charcoaling | 7 | 12 | 5 | 71.4 | −.065 | .352 | 14 | 15 | 1 | 7.1 | −.034 | .372 |

| Dishwashing | 7 | 5 | −2 | −28.6 | −.066 | .347 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 77.8 | −.024 | .377 |

| Mechanical | 4 | 9 | 5 | 125.0 | −.243 | .308 | 8 | 22 | 14 | 175.0 | −.148 | .388 |

| Housekeeping | 6 | 7 | 1 | 16.7 | −.103 | .437 | 10 | 28 | 18 | 180.0 | −.059 | .466 |

| Machine Operator | 4 | 5 | 1 | 25.0 | −.098 | .376 | 8 | 19 | 11 | 137.5 | −.092 | .369 |

| Boat driving | 10 | 5 | −5 | −50.0 | −.184 | .446 | 30 | 11 | −19 | −63.3 | −.177 | .435 |

| Food vending | 6 | 16 | 10 | 166.7 | .122 | .438 | 11 | 37 | 26 | 236.4 | .176 | .483 |

| Petty business | 8 | 12 | 4 | 50.0 | −.206 | .269 | 16 | 33 | 17 | 106.3 | −.169 | .292 |

| Brewing local beer | 4 | 7 | 3 | 75.0 | −.139 | .264 | 10 | 13 | 3 | 33.7 | −.231 | .161 |

| Crop business | 25 | 8 | −17 | −68 | .017 | .276 | 46 | 14 | −32 | −1.6 | .044 | .296 |

| Security Guard | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0.0 | −.133 | .317 | 12 | 14 | 2 | 30.0 | −.170 | .268 |

Table (A3) demonstrates that following gas extraction, farming activities dropped by 81.5% (95% CI: 0.144, 0.492) for nearby villages and by 83.5% (95% CI: 0.92, 0.431) for distant villages. GEOs severely impacted farming in nearby and distant villages. GEOs significantly impacted fishing by 85.2% (95% CI: 0.074, 0.345) for nearby and distant villages, respectively. GEOs impacted crop business by 68% (95% C.I.:.017,0.276) for nearby villages and 1.6% (95% C.I.:.044,0.296) for distant villages. The GEOs positively promoted petty business by 166.9% for nearby villages and 236.4% for remote villages. The GEO unaffected other livelihood vocations, including boat driving, fishing gear repair, security guarding, and motorcycle transport in near and distant areas. According to this, the GEOs notably caused a huge fall in farming and fishing, which had previously been the main sources of income. The study found that the GEOs had a favourable impact on the emergence of small enterprises as an alternate source of income. The results imply that actions are required to help households in the study area adjust to the changes brought on by the GEOs. This may entail locating alternate sources of income, granting access to financial and educational resources, and encouraging the growth of new firms.

Since gas extraction operations started in the study area, most people from nearby and farther away villages have found other ways to make a living, mostly by doing things other than farming and fishing. However, regulations and rules ban residents from farming and fishing near gas fields and processing plants. For example [56,58,76], came to the conclusion that the 2015 Petroleum Act and other rules don't allow some fish catchment zones. This is also evident in studies by Refs. [15,77,78], who examined the effects of oil and gas extraction on Nigerian fisher men's livelihoods and found that oil and gas extraction imposed great harm to their livelihood diversification (loss of access to fishing grounds) but had insignificant effects on fisher men's and fish traders' livelihoods.

GEOs increased food vending by 166.7% by 95% (CI: 0.122, 0.438) for nearby villages and by 236.4% by 95% (CI: 0.176, 0.483) for distant villages. Emerging populations chasing gas extraction jobs promoted food vending in the study area. The results also suggest that some households had to purchase food, beverages, and other necessities from stores and kiosks since GEOs had a detrimental effect on fishing and farming. This suggests that through increasing demand for goods and services, GEOs may have indirect effects on the local economy. According to Ref. [79], the majority of locals maintain their families through small businesses and other non-farm activities. It is important to keep in mind that the beneficial effects of GEOs on small enterprises and other non-farm endeavour might not last in the long run, particularly if the gas reserves are exhausted or if gas prices change. Local communities must therefore diversify their sources of income and get ready for potential changes in the future.

GEOs positively enhanced seashell collection activities by 816.7% for nearby communities and 462.5% in remote villages. The seashells were sold to Chinese enterprises in Mtwara Municipality for TZS 800 per kilogramme [67]. This made the seashell collection became the second source of income for rural populations in the study area. Natural gas extraction has revolutionized and diversified livelihood alternatives beyond farming and fishing. These findings are similar to the study done by Ref. [58] in the Kilwa district of Lindi on factors influencing extractive companies benefit sharing with host communities in Kilwa district, Tanzania, and they found that natural gas development has created new opportunities and shifted women's traditional roles from domestic to paid labour. It also shows that rural households react to gas extraction opportunities and demands. Diversifying livelihoods is a process of participation and adaptability, not a quick shift [6]. The primary data suggest that gas extraction operations have contributed to some diversity in residents' livelihood patterns. This is evidenced by the following quotation:

Before gas extraction, most of us were subsistence farmers and fishermen; restrictions and policy limited our ability to fish near onshore gas fields and processing plants during gas extraction." 18.10.2020, FGD No.1, Mngoji Village)

Some people at the KII talked about the need for more ways to make money before gas development in the research area. A woman in her 70s who participated in KII said:

“We know climate change has always been there, but gas extraction operations have made our lives worse. We cannot afford farm inputs." During the Kangomba (deceitful container to measure crop products) saga, our commodity prices are unstable." (KII, 70-year-old female, Msimbati Village, 18:10:2020)

Another KII male, aged 62, had this to say:

“The absence of work in our villages makes us all miserable," said another KII participant, who added: "Without farming in outside villages or collecting seashells, this community has little to offer." (A 62-year-old female, KII in Namindondi Village, 20:09:2020)

Shrinking cropland has reduced the number of farmers. As a result, the number of people working in farming and fishing has declined over time. The results indicate that the major sources of income for rural villagers have significantly changed as a result of the establishment of gas extraction operations in the study region. The majority of rural villagers relied on farming as their main source of income before gas extraction operations became common, while residents of surrounding villages also relied heavily on fishing as a source of income. However, the number of households involved in farming and fishing activities substantially decreased during the time of gas extraction operations, while non-farm economic activity rose in parallel. Less households are now relying on farming as their main source of income, which has had a detrimental impact on the economic value of the farming sector. Additionally, the loss of farming and fishing has created problems and raised food prices, making it difficult for some people to make ends meet. Due to continuous GEOs in the study area, people have abandoned land-based (farming and fishing) subsistence activities. Despite farming being one of the core economic sectors in the study area, fewer households use it as their primary source of income full-time, which hurts the sector's economic value. Conflicting needs for land for various uses as an old woman, based on the study area projection that:

“There will be no land for future use," making it likely that farmers' shares will shrink. The displacement of farming and fishing in the study region has generated challenges and boosted food prices. An older woman stated on GEOs and living costs, "

“Making a living is difficult because you can only eat with money." The gas location was once farmland. Since I no longer farm, I buy practically everything, including pepper. We are in pain." (72-year-old KII female in Msimbati, 17 October 2020)

Since the emergence of GEOs, most people in the study area have resorted to cash-only jobs. As fishing and farming activities are restricted and GEOs do not provide alternative jobs, non-fishing and off-farming income-generating activities have increased in communities. Despite the loss of agriculture, GEO's investments have been a curse in some villages. An analysis of the sorts of jobs in the community found that households earn money through miniature trading, seashell gathering, and food vending. These jobs absorb indigenous people who lose sustenance owing to GEO investments. Some characterize GEOs by shifting regional economic and employment trends from agriculture to industry [15].

3.3. Association between gas extraction operations and livelihood diversification

The livelihood activities of the rural villages under study have undergone considerable changes as a result of the existence of GEOs. Previously the main sources of income for many households, farming and fishing have mostly been replaced by non-farm activities. The decline of farming and fishing has lowered the economic value of these industries and brought to problems like rising food prices. According to the findings, the GEOs have helped the study area's households diversify their sources of income by encouraging them to partake in non-farming pursuits like food selling and seashell collecting. Table (A4) shows a significant (p = 0.000) association between farm wage work and gas extraction operations. The majority of households leave their neighborhood during the growing season in search of farm income opportunities despite natural gas regulations and rules that forbid farming close to gas fields and facilities. Due to constraints and rules that forbid farming close to gas fields and plants, the association between agricultural wage labour and gas extraction operations shows that many households are obliged to look for alternative sources of income during the growing season.

Table (A.4).

Association between GEOs and livelihood diversification (n = 260).

| Livelihood diversification | Nearby villages (120) |

95% C. I (Near) |

Distant Villages (140) |

95% C. I (Distant) |

Chi-square | P-value | Phi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| (%) | (%) | ||||||||

| Farming | 81.5 | .141 | .489 | 87.2 | −.489 | −.141 | 10.381*** | .001 | .200 |

| Fishing | 68.1 | .068 | .340 | 82.3 | −.340 | −.068 | 7.090*** | .008 | .165 |

| Salaried employment | 7.6 | −.043 | .349 | 11.3 | −.349 | .043 | 1.064 | .302 | .064 |

| Investor farm wage labour | 7.6 | −.099 | .330 | 8.5 | −.330 | .099 | .078 | .780 | .017 |

| Farm wage labour | 9.2 | .215 | .502 | 28.4 | −.502 | −.215 | 14.970*** | .000 | .240 |

| Carpentry and welding | 3.4 | −.081 | .402 | 8.5 | −.402 | .081 | 2.963* | .085 | .107 |

| Making bricks | 3.4 | .023 | .468 | 9.9 | −.468 | −.023 | 4.320** | .038 | .129 |

| Bicycle/motorbike repair | 5.9 | −.106 | .320 | 9.9 | −.320 | .106 | 1.423 | .233 | .074 |

| Motor-bike transport | 4.2 | −.179 | .328 | 6.4 | −.328 | .179 | .603 | .438 | .048 |

| Sea-shells collection | 5.0 | −.116 | .394 | 11.3 | −.394 | .116 | 3.313* | .069 | .113 |

| Charcoaling | 5.9 | −.060 | .357 | 9.9 | −.357 | .060 | 1.423 | .233 | .074 |

| Dishwashing | 5.9 | −.060 | .353 | 6.4 | −.353 | .060 | .028 | .867 | .010 |

| Mechanical and driving | 3.4 | −.236 | .315 | 5.7 | −.315 | .236 | .784 | .376 | .055 |

| Housekeeping | 5.0 | −.100 | .440 | 7.1 | −.440 | .100 | .470 | .493 | .043 |

| Machine Operator | 3.4 | −.096 | .378 | 5.7 | −.378 | .096 | .784 | .376 | .055 |

| Boat driving | 8.4 | −.184 | .446 | 21.3 | −.446 | .184 | 8.215*** | .004 | .178 |

| Food vendor | 5.0 | .127 | .443 | 7.8 | −.443 | −.127 | .804 | .370 | .056 |

| Petty business | 6.7 | −.205 | .270 | 11.3 | −.270 | .205 | 1.647 | .199 | .080 |

| Brewing local beer | 3.4 | −.131 | .272 | 7.1 | −.272 | .131 | 1.763 | .184 | .082 |

| Crop business | 21.0 | .021 | .280 | 32.6 | −.280 | −.021 | 4.386** | .036 | .130 |

| Security Guide | 5.0 | −.122 | .327 | .5 | −.327 | .122 | .205 | .272 | .068 |

*Phi-statistics are interpreted as follows: 0 to 0.11 indicates a weak association, 0.11 to 0.30 indicates a moderate association, and 0.31 and higher indicates a significant association (Healey, 2013). Statistically significant values are indicated by the symbols *, **, and ***, respectively, at p 0.05, p 0.01 and p 0.001 respectively.

GEOs and farming were also linked (p = 0.001). This means gas extraction operations were linked to farming due to rules and policies. GEOs and fishing were correlated (p = 0.008). GEOs and boat driving were significantly linked (p = 0.004). GEOs limit fishing near gas fields and wells along the coast and in the dipping sea.

Table (A4) shows a link between GEOs and seashell collection (p = 0.036). After natural gas rules and policies restricted farming and fishing near the coast, households shifted to collecting seashells. GEOs and crop businesses were also linked (p = 0.036). Fire from gas tanks shrank and killed plant leaves. Communities surrounding gas fields and processing factories claimed the investment limited their ability to gather crops. This was agreed upon by the participants of the FGD:

Nowadays, doing farming and fishing activities is harder than before gas extraction because of access restrictions to farmlands and fishing grounds near gas fields and plants (FGD No. 3, in Namindondi Village, 11.09.2020).

In “Phi-statistics,” Table (A4) shows that farm-wage labour, fishing, boat driving, crop business, seashell gathering, brick making, carpentry, and welding were moderately associated with gas extraction. This implies that GEOs have influenced various livelihood diversification; this is consistent with [41], who found that extractive investments are vital for changing local communities’ means of subsistence. This research argues that exposure to GEOs in the surveyed area shifted livelihood activities and had variable, multidimensional effects on local populations' efforts to diversify their sources of income. A 52-year-old KII participant said:

“GEOs have made farming expensive in our village. During farming season, I do wage work in faraway communities to buy food for my family. Isn't this better than nothing? We need the gas investors' guidance, not how they treat our community" (a 52-year-old KII in Mngoji village, October 17, 2010).

Based on GEOs and livelihood diversification, economic prospects among residents have not improved. Inhabitants lacked access to formal jobs such as driving, housekeeping, security, and other professions at gas investment companies. However, GEOs have enhanced the diversification of other activities such as seashell gathering, petty business, welding, motorcycle transport services, and food vending. This happens when gas extraction investors and the Tanzania Petroleum Development Cooperative (TPDC) put regulations in place to control communities’ free access to fish-catch areas and farming lands where there are gas fields and processing plants [70,76].

3.4. Perceived livelihood diversification in Mtwara Rural District

Table (A5) shows how communities feel GEOs have diversified livelihoods in nearby and distant areas. The results imply that the livelihoods of adjacent and far-off people have been impacted differently by gas extraction activities. Farm wage labour has increased by 58% (95% CI:.034, 215) and by 38% (95% CI:.042, 222) in communities near and distant to gas fields and processing plants, respectively. Carpentry has also improved in both nearby and distant communities. However, some activities, such as fishing, have decreased by 92.4% (CI:.047,0.398) and by 83.0% (CI:.017,0.330) for near and distant villages. The report contends that both close-by and far-off towns now have lessened access to formal economic possibilities including salaried labour and security guard jobs. Additionally, the Tanzania Petroleum Development Cooperative and gas investors' restrictions and regulations have restricted farming and fishing operations close to gas fields and processing facilities, which has caused a shift in the local economy towards seashell collecting, small-scale business operations, welding, motorcycle transport services and food vending. The study comes to the conclusion that residents' economic prospects have not necessarily increased and that exposure to GEOs has encouraged a variety of livelihood diversification.

Table (A.5).

Perceived livelihood diversified in Mtwara Rural District (n = 260).

|

Livelihood diversification |

Responses | Near Villages (n = 120) |

95% (CI) for Near Villages |

Distant Villages (140) |

95% (CI) for Distant Villages |

Chi-square | P-value | Phi* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||||

| (%) | (%) | |||||||||

| Farming | High | 84.9 | −.026 | .331 | 83.0 | −.105 | .247 | 3.351* | .067 | .114 |

| Moderate Low |

9.2 | 17.0 | ||||||||

| Fishing | High | 92.4 | .047 | .398 | 83.0 | −.017 | .330 | 5.210* | .022 | .142 |

| Moderate Low |

7.6 | 17.0 | ||||||||

| Salaried employment | High | 34.5 | −.094 | .166 | 30.5 | −.209 | .048 | .462 | .497 | .042 |

| Moderate Low |

65.5 | 69.5 | ||||||||

| Investor farm wage labour | High | 23.5 | −.091 | .116 | 24.8 | −.108 | .096 | .923 | .630 | .060 |

| Moderate | 76.5 | 74.5 | ||||||||

| Low | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||||||||

| Farm wage labour | High | 58.0 | .034 | .215 | 35.5 | .042 | .221 | 16.537*** | .000 | .552 |

| Moderate | 31.1 | 56.0 | ||||||||

| Low | 10.9 | 8.5 | ||||||||

| Carpentry and welding | High | 31.1 | .023 | .170 | 17.0 | .022 | .168 | 9.179* | .027 | .188 |

| Moderate | 32.8 | 33.3 | ||||||||

| Low | 36.2 | 49.6 | ||||||||

| Making bricks | High | 70.6 | −.219 | .029 | 75.2 | −.210 | .035 | 7.613* | .022 | .171 |

| Moderate | 19.3 | 22.7 | ||||||||

| Low | 10.1 | 2.1 | ||||||||

| Bicycle/motorcycle repair | High | 10.9 | −.240 | .036 | 22.0 | −.168 | .105 | 10.296** | .006 | .199 |

| Moderate | 79.0 | 75.2 | ||||||||

| Low | 10.1 | 2.8 | ||||||||

| Motor-bike transport | High | 9.2 | −.240 | .036 | 9.2 | −.100 | .185 | 14.530** | .002 | .236 |

| Moderate | 35.3 | 21.3 | ||||||||

| Low | 55.5 | 68.5 | ||||||||

| Brewing | High | 8.4 | −.059 | .230 | 7.8 | −.100 | .185 | .031 | .859 | .011 |

| Moderate Low |

91.6 | 92.2 | ||||||||

| Charcoaling | High | 24.4 | −.141 | .074 | 31.2 | −.109 | .103 | 4.520 | .104 | .132 |

| Moderate | 72.3 | 61.0 | ||||||||

| Low | 3.4 | 7.8 | ||||||||

| Dishwashing | High | 26.9 | −.113 | .070 | 26.2 | −.088 | .092 | .143 | .931 | .023 |

| Moderate | 57.1 | 56.0 | ||||||||

| Low | 16.0 | 17.7 | ||||||||

| Mechanical | High | 21.0 | −.162 | .019 | 27.7 | −.185 | −.006 | 7.527* | .023 | .170 |

| Moderate | 51.3 | 58.2 | ||||||||

| Low | 27.7 | 14.2 | ||||||||

| Housekeeping | High | 18.5 | −.169 | .023 | 25.5 | −.184 | .005 | 7.920* | .019 | .175 |

| Moderate | 68.1 | 70.2 | ||||||||

| Low | 13.4 | 4.3 | ||||||||

| Machine Operator | High | 16.0 | −.183 | .015 | 24.1 | −.197 | −.002 | 7.339* | .025 | .168 |

| Moderate | 62.2 | 65.2 | ||||||||

| Low | 21.8 | 10.6 | ||||||||

| Boat driving | High | 84.9 | −.139 | .224 | 83.0 | −.159 | .199 | 2.934 | .231 | .106 |

| Moderate | 13.4 | 17.0 | ||||||||

| Low | 1.7 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Food vendor | High | 15.1 | −.012 | .170 | 10.6 | .041 | .220 | 6.519 | .089 | .158 |

| Moderate | 43.7 | 36.2 | ||||||||

| Low | 38.6 | 53.2 | ||||||||

| Security Guide | High | 11.8 | −.204 | .090 | 22.0 | −.202 | .088 | 4.725 | .094 | .135 |

| Moderate | 79.8 | 70.2 | ||||||||

| Low | 8.4 | 7.8 | ||||||||

| Petty Business | High | 9.2 | −.117 | .061 | 9.2 | −.173 | .003 | 14.530** | .002 | .236 |

| Moderate | 35.3 | 21.3 | ||||||||

| Low | 55.5 | 69.5 | ||||||||

Note: * Phi-statistics was interpreted as follows: 0–0.11 is weak strength of association, 0.11–0.30 is moderate strength of association, and 0.31 - above is strong strength of association (Healey, 2013). *, ** and *** represent statistically significant levels at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.001 respectively.

The results from Table (A5) show that the diversification of livelihood activities in local and far-off villages has been positively impacted by GEOs. Both close-by and far-off villages have seen a major rise in small business and food vending. This shows that GEOs have enhanced chances for small companies and entrepreneurship in the studied region, which may ultimately result in better economic prospects for locals. The findings also suggest that local people have discovered new sources of income generating and have adapted to the presence of GEOs. It should be highlighted, too, that the rises in petty trade and food vending were quite modest and might not be sufficient to counteract the detrimental effects of GEOs on traditional subsistence activities like farming and fishing. To better understand the long-term repercussions of GEOs on local livelihoods and to develop mitigation techniques that maximize good results, more research is required [58].'s investigation, which found that the 2015 Petroleum Act and its regulations forbid specific fish catchment areas, is proof of this.

Table (A5) shows that GEOs have increased various livelihood activities. Petty business increased by 55.5% (95% CI: 0.117, 0.061) for near villages and by 69.5% (95% CI: 0.173, 0.003) for distant villages with p = 0.002 significance, while food vending increased by 38.6% (95% CI: 0.012, 0.170) for near villages and by 53.3% (95% CI: 0.041, 0.220) for distant villages with p = 0.089 significance. This implies that during GEOs, communities tend to engage in non-professional livelihood activities. This contributed to the provision of get-up-and-go, which aided communities in adjacent and distant areas to look for other livelihood activities in order to survive. This is consistent with the studies done by Refs. [60,70,80,81] in the Mtwara Rural district of Tanzania, where they explore that the availability of gas did not encourage the development of manufacturing and processing firms in the research area, forcing neighborhood households to diversify their income sources. Some livelihood activities were favourable connected with gas extraction, such as petty business, food vending, and motorcycling, whereas others, such as seashells, farm wage labour and carpentry, were not. Local communities should have diversified their income sources as expected from gas extraction investors.

However, in “phi-statistics,” farm-wage labor had significant associates at (0.552). Likewise, farming (0.114); fishing (0.142); carpentry (0.188); bicycle/motorbike repair (0.199); motorbike transport (0.171); brick making (0.236); machine operator (0.168); food vendor (0.158); mechanical (0.170); and petty business (0.236) showed moderate associations with GEOs. Livelihood activities strengthened respondents' attitudes toward local communities and GEOs before and during gas extraction. This is consistent with studies done in the Mtwara Rural District of Tanzania by Ref. [60] on gas extraction operations and changes in livelihood activities that explored that there is an increase in other non-farm activities like carpentry, brickmaking, motorbike transport, and bicycle repair in closer villages. Also, other studies done in Azad Jammu and Kashmir by Ref. [43] on the impact of micro hydropower (MHP) projects on household income, expenditure, and diversification of livelihood strategies. They found that MHP—micro hydro-power—has a positive and significant effect on households’ adoption of non-farm and diversified livelihood strategies. Likewise, this study also is in line with the study done in Ghana by Ref. [82], which examines how fishermen livelihoods have been affected by the extraction and production of oil. The study shows that fisher folk in the Western Region of Ghana are under high socio-economic susceptibility because of decreased fish catches and declining coastal livelihoods. This was agreed upon by the participants of the FGD:

We can say with certainty that gas extraction has changed our lives and the lives of our children. We don't have jobs, and gas investors aren't putting money into infrastructure or social services in our area. We cannot sell our goods near gas fields or processing units (FGD No. 1, Msimbati Village, 8:10:2020).

Other FGDs said,

No child has ever been offered a scholarship since gas extraction began in our village, while in Songo-Songo, Lindi, at least four pupils get them annually. Why Mngoji? (FGD No. 3, Mngoji Village, 02.10.2020).

These results are consistent with the [61] study on the Mtwara gas project dispute: its causes and potential solutions, which revealed unmet community expectations such as the availability of employment opportunities among nearby community members, the sale of goods from nearby villages to gas investors, and education opportunities as stipulated in the local content policy. The local content policy insists on about 80% of the villagers being employed in gas investment through various positions, but the study reveals that less than 1% are employed in gas investment, mainly in the position of security guard. Results are consistent with the study done in Kilwa district, Lindi region, Tanzania, by Ref. [56] on the reality of local community participation in the natural gas sector in Southeastern Tanzania and [58] on factors influencing extractive companies sharing benefits with host communities in Kilwa District, Tanzania. They found that the stakeholder had a higher expectation of benefit sharing, but they perceived a low level of benefit sharing from extractive companies. They discovered that the Petroleum Act of 1980, as amended by the Petroleum Act of 2015, Section 118 (2), forbids access to some fish catchment areas by requiring contractors and license holders of any extractive company to ring-fence or restrict explorations, pipelines, or gas wells for safety reasons.

The reasons given in the FGD go against Tanzania's local content strategy and the law that went into effect in 2015. Citizens will benefit in a variety of ways from this resource, including the provision of services in the fields of gas extraction investments and employment as technical specialists in projects related to gas extraction [47,83,84]. In addition, Tanzania's natural gas is considered the property of the Tanzanian people and must be put to use for the betterment of the entire nation, as stated in the natural gas policy [47].

3.5. Policy implications

First, the results imply that gas extraction operations can affect the way of life in adjacent communities in both positive and bad ways. Policymakers should be aware of these effects and take action to lessen negative effects while enhancing good ones. The study also emphasizes the necessity of livelihood diversification in areas close to gas production operations. To lessen reliance on traditional livelihoods like farming and fishing that can be adversely impacted by gas extraction activities, policymakers should encourage and support the growth of alternative livelihoods, such as tiny businesses and food vending. Thirdly, the results imply that measures should be taken to safeguard the environment and the way of life in the adjacent communities. To prevent the destruction of fish-rich areas and an increase in agricultural demand, limits on farming and fishing may be imposed in areas close to gas fields and processing factories. Finally, community involvement and participation in decision-making processes regarding gas extraction operations and their possible effects on livelihoods should be given priority by policymakers. This can ensure that local populations' concerns and interests are taken into consideration and that the advantages of gas extraction are distributed equally among all stakeholders.

4. Conclusions and recommendations

On the livelihoods of nearby and far-off communities, gas extraction operations have had both positive and bad effects, it can be said. On the plus side, gas extraction operations have increased the number of income-generating ventures like food vending and petty business. On the downside, because of limits and laws, they have caused a reduction in traditional subsistence activities like farming and fishing.

As a result, rules and laws that guarantee the preservation of the environment and the way of life of the local inhabitants are required. While promoting the growth of alternative income-generating activities, these policies should place a priority on the sustainability of traditional livelihoods. Additionally, it is crucial to make sure that the communities impacted by gas extraction activities participate actively in the decision-making process and are fairly compensated for any harm to their way of life.

In addition, further investigation is required to completely comprehend how gas extraction operations affect the environment, public health, and the way of life in local towns. A multidisciplinary approach should be used to conduct this research and include a range of stakeholders, such as local people, the government, and gas extraction firms.

Author contribution statement

Beston Musa Musoma: Conceived and designed the analysis; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Suzana Samson Nyanda: Conceived and designed the analysis; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Mikidadi Idd Muhanga: Conceived and designed the analysis; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed analysis tools or data.

Fatihiya Ally Massawe: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial intersts or personal relationships that could have appeared to influnce the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Mtwara Local Government Officers, Sokoine University of Agriculture (MOROGORO-TANZANIA), and the Institute for Rural Development Planning (DODOMA-TANZANIA).

Contributor Information

Beston Musa Musoma, Email: bmusoma@irdp.ac.tz.

Suzana Samson Nyanda, Email: suzy_nyanda@sua.ac.tz.

Mikidadi Idd Muhanga, Email: mikidadi@suac.tz.

Fatihiya Ally Massawe, Email: mnkya74@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Loison Household livelihood diversification and gender: panel evidence from rural Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 2019;69:156–172. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martins P.M. Structural change: pace, patterns and determinants. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2019;23(1):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin S.M., Lorenzen K. Livelihood diversification in rural Laos. World Dev. 2016;83:231–243. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baird T.D., Hartter J. Livelihood diversification, mobile phones and information diversity in Northern Tanzania. Land Use Pol. 2017;67:460–471. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gautam Y., Andersen P. Rural livelihood diversification and household well-being: insights from Humla, Nepal. J. Rural Stud. 2016;44:239–249. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Z., Lan J. World Dev. 2015;vol. 70:147–161. The Sloping Land Conversion Program in China: Effect on the Livelihood Diversification of Rural Households. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins G. Mining FDI and urban economies in sub-Saharan Africa: exploring the possible linkages. Local Econ. 2013;28(2):158–169. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elbra A., Elbra A. 2017. A History of Gold Mining in South Africa, Ghana and Tanzania. Governing African Gold Mining: Private Governance and the Resource Curse; pp. 67–103. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muhanga M. 2007. Corporate Social Responsibilities Among Oil Extracting Multinational Companies' in Least Developing Countries: Helping but Not Developing or Helping and Developing? Available at: SSRN 2700613. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epizitone A., Moyane S.P., Agbehadji I.E. Healthcare. MDPI; 2023. A systematic literature review of health information systems for healthcare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Besada H., Lisk F., Martin P. Regulating extraction in Africa: towards a framework for accountability in the global south. Govern. Afr. 2015;2(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diamond L., Mosbacher J. Petroleum to the people: Africa's coming resource curse-and how to avoid it. Foreign Aff. 2013;92:86. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budiono R., Nugroho B., Nurrochmat D.R. The village forest as a counter teritorialization by village communities in Kampar peninsula Riau. Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika. 2018;24(3):115. 115. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahman H.T., et al. Livelihood exposure to climatic stresses in the north-eastern floodplains of Bangladesh. Land Use Pol. 2018;79:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowokpor V. The University of Bergen; 2015. Impacts of the Oil and Gas Industry on the Livelihoods of Men and Women Working in the Fisheries: a Study of Shama, Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aniah P., Kaunza-Nu-Dem M.K., Ayembilla J.A. Smallholder farmers' livelihood adaptation to climate variability and ecological changes in the savanna agro ecological zone of Ghana. Heliyon. 2019;5(4) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acheampong M. University of South Florida; 2018. Assessing the Impacts of Ghana's Oil and Gas Industry on Ecosystem Services and Smallholder Livelihoods. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilson G. Corporate Social Responsibility in the extractive industries: experiences from developing countries. Resour. Pol. 2012;37(2):131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Faircheallaigh C. Extractive industries and Indigenous peoples: a changing dynamic? J. Rural Stud. 2013;30:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khosla S., Jena P.R. Switch in livelihood strategies and social capital have a role to play in deciding rural poverty dynamics: evidence from panel data analysis from eastern India. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2020;55(1):76–94. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bozigar M., Gray C.L., Bilsborrow R.E. Oil extraction and indigenous livelihoods in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon. World Dev. 2016;78:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis F. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. J. Dev. Stud. 1998;35(1):1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins J. A Rising Tide in Bangladesh: livelihood adaptation to climate stress. Aust. Geogr. 2014;45(3):289–307. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burchfield E.K., de la Poterie A.T. Determinants of crop diversification in rice-dominated Sri Lankan agricultural systems. J. Rural Stud. 2018;61:206–215. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasan M.K., Kumar L. Perceived farm-level climatic impacts on coastal agricultural productivity in Bangladesh. Climatic Change. 2020;161(4):617–636. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy A., Basu S. Determinants of livelihood diversification under environmental change in coastal community of Bangladesh. Asia Pac. J. Rural Dev. 2020;30(1–2):7–26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kazeem A.A., et al. Attitudes of farmers to extension trainings in Nigeria: implications for adoption of improved agricultural technologies in Ogun state southwest region. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, Belgrade. 2017;62(4):423–443. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernier Q., et al. Water management and livelihood choices in southwestern Bangladesh. J. Rural Stud. 2016;45:134–145. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alam G.M., et al. Vulnerability to climatic change in riparian char and river-bank households in Bangladesh: implication for policy, livelihoods and social development. Ecol. Indicat. 2017;72:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabir M.J., Alauddin M., Crimp S. Farm-level adaptation to climate change in Western Bangladesh: an analysis of adaptation dynamics, profitability and risks. Land Use Pol. 2017;64:212–224. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amevenku F., Asravor R., Kuwornu J.K. Determinants of livelihood strategies of fishing households in the volta Basin, Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance. 2019;7(1) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rui Z., et al. Investigation into the performance of oil and gas projects. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017;38:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buur L. JSTOR; 2014. The Development of Natural Resource Linkages in Mozambique: the Ruling Elite Capture of New Economic Opportunities. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Danquah J.A., Roberts C.O., Appiah M. Effects of decline in fish landings on the livelihoods of coastal communities in Central Region of Ghana. Coast. Manag. 2021;49(6):617–635. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abukari H., Mwalyosi R.B. Comparing conservation attitudes of park-adjacent communities: the case of mole national park in Ghana and tarangire national park in Tanzania. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2018;11 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaafsma M., Utila H., Hirons M.A. Understanding trade-offs in upscaling and integrating climate-smart agriculture and sustainable river basin management in Malawi. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2018;80:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen B., et al. Experimental investigation of natural gas hydrate production characteristics via novel combination modes of depressurization with water flow erosion. Fuel. 2019;252:295–303. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimengsi J.N., Mukong A.K., Balgah R.A. Livelihood diversification and household well-being: insights and policy implications for forest-based communities in Cameroon. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020;33(7):876–895. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shao J.a., Huang Z., Deng H. Characteristics of nonpoint source pollution load from crop farming in the context of livelihood diversification. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018;28:459–476. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao X., et al. The influence of farmers' livelihood strategies on household energy consumption in the eastern qinghai–tibet plateau, China. Sustainability. 2018;10(6):1780. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walelign S.Z., et al. Combining household income and asset data to identify livelihood strategies and their dynamics. J. Dev. Stud. 2017;53(6):769–787. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helmy I. GLO Discussion Paper; 2020. Livelihood Diversification Strategies: Resisting Vulnerability in Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siraj M., Khan H. Impact of micro hydropower projects on household income, expenditure and diversification of livelihood strategies in Azad Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistan Dev. Rev. 2019;58(1):45–63. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gani B.S., Olayemi J.K., Inoni O.E. Livelihood diversification strategies and food insecurity status of rural farming households in North-Eastern Nigeria. Економика пољопривреде. 2019;66(1):281–295. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paudel Khatiwada S., et al. Household livelihood strategies and implication for poverty reduction in rural areas of central Nepal. Sustainability. 2017;9(4):612. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robaa B., Tolossa D. Rural livelihood diversification and its effects on household food security: a case study at Damota Gale Woreda, Wolayta, Southern Ethiopia. E. Afr. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. 2016;32(1):93–118. [Google Scholar]

- 47.URT . In: The National Natural Gas Policy of Tanzania. Energy M.o., editor. Government Printer: Dar es Salaam; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinyondo A., Villanger E. Local content requirements in the petroleum sector in Tanzania: a thorny road from inception to implementation? Extr. Ind. Soc. 2017;4(2):371–384. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Byaro M., Msafiri D. The uncertainty of natural gas consumption in Tanzania to support economic development. Evidence from Bayesian estimates. African Journal of Economic Review. 2021;9(4):168–182. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Worthington B. United States Energy Association, Inc; 2019. Promoting Domestic and International Consensus on Fossil Energy Technologies-Program Area 2: International Oil and Natural Gas. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henstridge M. Mining for Change; 2018. Understanding the Boom. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bishoge O.K., et al. An overview of the natural gas sector in Tanzania-Achievements and challenges. Journal of Applied and Advanced Research. 2018;3(4):108–118. [Google Scholar]

- 53.URT, Population and Housing Census General Report, N.B.o.S. (NBS) Gvernment Printer, Dar es salaam: Dar es salaam; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ogwang T., Vanclay F. Cut-off and forgotten?: livelihood disruption, social impacts and food insecurity arising from the East African Crude Oil Pipeline. Energy Res. Social Sci. 2021;74 [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Zeeuw J., Kuschminder J. Building Flourishing Communities; Cordaid: 2016. When Oil, Gas or Mining Arrives in Your Area: Practical Guide for Communities, Civil Society and Local Government on the Social Aspects of Oil, Gas and Mining. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mwanyoka I., Mdemu M., Wernstedt K. The reality of local community participation in the natural gas sector in Southeastern Tanzania. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021;8(1):303–315. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamat V.R., et al. Natural gas extraction and community development in Tanzania: documenting the gaps between rhetoric and reality. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019;6(3):968–976. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mwakyambiki S.E., Sikira A.N., Massawe F.A. Factors influencing extractive companies benefits sharing with host communities in Kilwa district, Tanzania. Int. J. Res. Soc. Sci. 2018;8(5):375–395. [Google Scholar]

- 59.URT . In: Tanzania Demographic Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey 2015/16. Statistics N.B.o., editor. Government Printer: Dar es Salaam; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Musoma B.M., Nyanda S.S., Massawe F.A. Gas extraction operations and changes in livelihood activities: experience from Mtwara Rural District in Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2022;21(1):235–251. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thobias M., Kseniia M. Mtwara gas project conflict: causes of arising and ways of stabilization (Part 2) Soc. Sci. 2017;6(3):73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Polus A., Tycholiz W. Extractive sector in a SUB-saharan functional state. The case of natural resource sector in Tanzania. Politeja. 2018;56:151–168. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh J.V. Performance, slack, and risk taking in organizational decision making. Acad. Manag. J. 1986;29(3):562–585. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ally M. Mobile learning anytime everywhere; 2005. Using Learning Theories to Design Instruction for Mobile Learning Devices; pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chambers R., Conway G. Institute of Development; Studies (UK): 1992. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kollmair M., Gamper S. Input Paper for the Integrated Training Course of NCCR North-South Aeschiried; Switzerland: 2002. The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 67.URT . In: Mtwara District Council Socio-Economic Profile (MDC) Council M.D., editor. 2016. (Government printer: Mtwara Tanzania) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wright A., et al. Natural gas in Tanzania. CMI BRIEF. 2016;15(4) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roe A. WIDER Working Paper; 2016. Tanzania: from Mining to Oil and Gas. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bofin P., Pedersen R.H. JSTOR; 2017. Tanzania's Oil and Gas Contract Regime, Investments and Markets. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Duyverman H.J., Msaky E. SPE/AAPG Africa Energy and Technology Conference. 2016. Shale oil and gas in East Africa (Esp. Tanzania) with new ideas on reserves and possible synergies with renewables. (OnePetro) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Foussard C., Denis-Remis C. Risk assessment: methods on purpose? Int. J. Process Syst. Eng. 2014;2(4):337–352. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kothari C.R. Research methodology: methods and techniques. New Age International; 2004. pp. 74–1. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Patton M.Q. 2005. Qualitative Research. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rugeiyamu R. The Tanzania housing and population census 2022: a panacea for local service delivery and development drawbacks. Local Administration Journal. 2022;15(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kweka O.L., Pedersen R.H. 2023. Community Participation in Tanzania's Petroleum Sector. Land, Rights and the Politics of Investments in Africa: Ruling Elites, Investors and Populations in Natural Resource Investments; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Choumert-Nkolo J. Developing a socially inclusive and sustainable natural gas sector in Tanzania. Energy Pol. 2018;118:356–371. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adusah-Karikari A. Black gold in Ghana: changing livelihoods for women in communities affected by oil production. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2015;2(1):24–32. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aragón F., Chuhan-Pole P., Land B. The World Bank; 2015. The Local Economic Impacts of Resource Abundance: what Have We Learned? [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nuhu S., et al. Regulatory framework and natural gas activities: a curse or boon to host communities in Southern Tanzania? Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020;7(3):982–993. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barlow A. Piping away development: the material evolution of resource nationalism in Mtwara, Tanzania. J. South Afr. Stud. 2022:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Owusu V. Impacts of the petroleum industry on the livelihoods of fisherfolk in Ghana: a case study of the Western Region. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019;6(4):1256–1264. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Herr D., et al. An analysis of the potential positive and negative livelihood impacts of coastal carbon offset projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2019;235:463–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Anderson E.P., et al. Energy development reveals blind spots for ecosystem conservation in the Amazon Basin. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019;17(9):521–529. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.