Abstract

This study focuses on the intricate process of discerning productive layers within reservoir formations, taking the Sarvak Formation as a primary case. The employed methodology combines geology, comprehensive log interpretations, and petrophysical analyses to facilitate the evaluation of these productive layers. Initially, routine well logs are interpreted to determine key petrophysical parameters such as shale content, porosity, and water saturation. Subsequently, core measurement results are utilized for calibrating these log interpretations. The study further determines cut-off values through a calculated method of 5% cumulative hydrocarbon volume against porosity, shale content, and water saturation. These cut-off values are then applied to the petrophysical results to enhance their reliability. To resolve any inconsistencies or uncertainties in petrophysical evaluation, petrographical analyses, including scanning electron microscope imaging and thin section studies, are employed. The Sarvak Formation is categorized into seven distinct subzones, each thoroughly investigated to ascertain their respective productivity potential. The final results illustrate a substantial heterogeneity within the Sarvak Formation, revealing a range of diagenetic processes including compaction, dissolution, and cementation. Despite this complexity, three subzones are identified as the most productive layers with the maximum net pay, demonstrating the efficacy of the integrated approach.

Keywords: Net pay, Reservoir quality, Sarvak formation, Petrophysical evaluation, Petrographical study, Integrative approach

1. Introduction

The realm of hydrocarbon exploration has unequivocally recognized the importance of an integrated approach, with its pivotal aim to enhance field productivity while judiciously managing the costs involved [[1], [2], [3]]. Central to this comprehensive approach in reservoir studies is the pursuit of a precise and all-encompassing perspective on field development, as emphasized by numerous academic studies and industry practices [4,5]. This integrated perspective amalgamates insights from various disciplines, facilitating the determination of the spatial distribution of essential petrophysical properties such as porosity, permeability, and water saturation. These characteristics form the foundation for the quality evaluation of oil and gas reservoirs, significantly influencing the success of hydrocarbon exploitation and strategic field development [[6], [7], [8], [9]].

Unraveling the factors that impact reservoir quality forms the cornerstone of appraising the longevity of production operations [3,[10], [11], [12]]. Therefore, the identification of productive reservoir layers has become an essential focus amidst the array of objectives defined by integrated studies. These productive layers, denoted as the reservoir thickness harboring significant producible hydrocarbons, have been a critical aspect of reservoir studies [[13], [14], [15], [16]].

Historically, numerous studies have engaged in understanding the concept and properties of productive layers through two primary methodologies. The direct method employs instruments such as gas meters, fluorimetry, well tests, and geochemical analyses of sidewall cores [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. The indirect method contrasts this by assimilating geological, petrophysical, and geophysical data to infer productive layers using an assortment of tools and techniques [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25]].

Despite these strides, there is a distinct gap in contemporary literature concerning the exploration of productive layers in carbonate reservoirs, inherently characterized by their heterogeneity [26,27]. Most research has predominantly centered on sandstone reservoirs, thus leaving the unique complexities of carbonate reservoirs underexplored [[28], [29], [30], [31]].

This gap is addressed by our study which delves into the productive layers within the Sarvak Formation in the west Karun of South Iran. An integrative approach is adopted, leveraging core analysis data, conventional logs, and geological characteristics. Our work, which builds on recent advancements in productive zone determination using conventional logs [[32], [33], [34], [35], [36]], presents an innovative method for integrating diverse datasets to assess the quality of productive reservoir sections in carbonate reservoirs. The study's limitations due to the absence of advanced log data, such as DSI and NMR, and production tests like PLT and flowmeter, are acknowledged. Nevertheless, a significant contribution to understanding productive layers in complex carbonate formations is made by the proposed methodology, thereby bridging a notable gap in the existing literature.

2. Geological setting

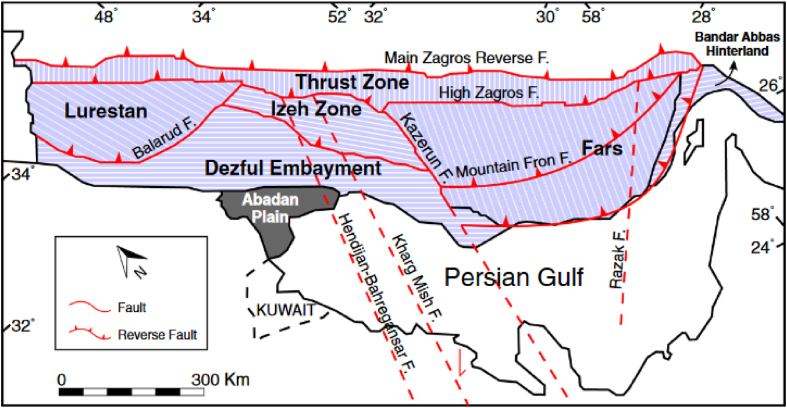

The southwestern region of Iran (SW) is home to the majority of the country's hydrocarbon fields. These fields follow two predominant geological trends: the Zagros trend, extending in a northwest to southeast direction, and the Arabian trend, which runs from north to south and northeast to southwest [37]. The oilfield under investigation in this study is situated to the west of the Karun River, within the Abadan Plain. This region forms a tectonic zone on the western periphery of the Zagros Fold Thrust Belt [38]. As shown in Fig. 1, the research oilfield is nestled within the Abadan Plain.

Fig. 1.

Geographic positioning of the Abadan Plain within the Zagros Embayment [42].

This particular geographical location exposes the Abadan Plain to the geological and structural influences of the Arabian Shield to the southwest and the Zagros Fold Thrust Belt to the northeast. However, the imprint of the Arabian Shield's characteristics is more discernible within the Abadan Plain [39]. The region’s geological complexity is further enhanced by faults and tectonic salt movements, which have orchestrated the formation of a north-south trending anticline with a moderate slope [37].

The Arabian Plateau and the Zagros Basin harbor enormous oil reservoirs that are hosted within chalk-thick carbonate deposits. Within these deposits, the Bangestan Group, comprising the Ilam and Sarvak Formations, represents a typical reservoir formation in the region. The Sarvak Formation's upper interface is often linked to the Ilam Formation in most Iranian fields [40].

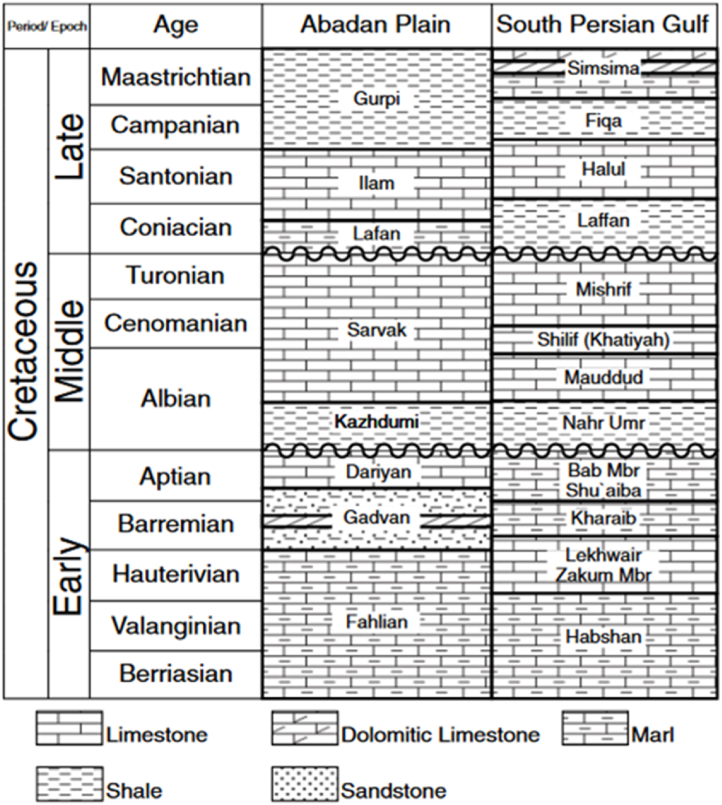

Fig. 2 illustrates a simplified stratigraphic sequence of the Cretaceous period in the Abadan Plain, contrasting it with the geological column of the Southern Persian Gulf. The type section here presents three sedimentary units with a cumulative thickness of 822 m [38]. The Sarvak Formation, predominantly deposited in shallow marine environments during the Cenomanian period, gradually transitioned into low-energy environments towards the Persian Gulf. The discovery of unconformable conglomerates, breccias, and ferruginous sediments in the upper segment of the Sarvak Formation point towards local uplift during the Late Turonian [38].

Fig. 2.

Comparison of Cretaceous stratigraphy in the Abadan Plain (southwestern Iran) and the southern Persian Gulf (United Arab Emirates and Qatar) (modified from Refs. [37,38]).

A discernible characteristic of the boundary between the Sarvak and Kazhdumi formations is the alternation of limestone (Sarvak Formation) with the underlying Kazhdumi Formation [41]. The Sarvak Formation, along with the overlying Ilam Formation, represents expansive limestone units that were deposited in shallow marine environments, as interpreted in the Dezful Embayment. Although erosive inconsistencies exist between these subsurface and outcropping units, differentiating them can often be challenging.

In parts of the Abadan Plain, including the study field, shale units overlay the Sarvak Formation; this shale unit is referred to as the Laffan Shale Formation. In terms of stratigraphic equivalence, the Sarvak Formation aligns with the Mauddud, Khatiya, and Mishrif sequences in the Southern Persian Gulf. The thickness of the Sarvak Formation in the study area fluctuates between 590 and 670 m, corresponding to the Ahmadi Shale Formation in Fars, Kuwait, and southern Iraq, and the Mauddud Limestone Formation in southern Iraq and Kuwait. The upper segment of the Sarvak Formation, akin to the Mishrif Formation in Iraq, comprises similar fossil-rich limestone with an abundance of rudists, corals, algae, and stromatopoloids [[38], [39], [40]].

3. Material and methods

This research utilizes a set of conventional logs, core measurements, and petrographical analysis from an extensively studied oilfield. The specific stratigraphy under investigation is the Sarvak Formation, a substantial structure exceeding 600 m in thickness.

The study adopts a systematic approach beginning with the plotting of all available conventional logs. These logs are meticulously interpreted to calculate the well's reservoir rock properties. Following this initial interpretation, core measurements are undertaken as a second step to calibrate the derived petrophysical results. This process ensures the validity and accuracy of the interpreted logs, facilitating a more precise understanding of the reservoir's characteristics.

The third phase involves determining the cut-off values for the petrophysical parameters, a critical step for identifying net pay zones. These cut-offs act as quantitative thresholds that aid in differentiating between productive and non-productive intervals within the reservoir.

The final step encompasses petrographical analysis, which serves to qualify the productive layer and elucidate the variation in reservoir properties throughout the well. This in-depth analysis, which includes the examination of rock sample characteristics and features under a microscope, provides invaluable insights into the mineral composition, texture, and other physical attributes of the reservoir. These insights can further inform the understanding of the reservoir's diagenetic history and its impacts on reservoir quality.

Fig. 3 offers a detailed illustration of the research workflow, visually articulating each step of the methodology. By adopting this structured approach, the study aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the productive layers within the Sarvak Formation, addressing their intricate characteristics and contributing to the broader understanding of carbonate reservoirs.

Fig. 3.

Workflow of the research.

3.1. Data gathering and preparation

Standardized protocols were followed for sample preparation and the measurement of fundamental rock properties in the laboratory setting. Core samples utilized in this study were extracted from the Sarvak Formation, and several core plugs with dimensions of 1.5-inch diameter and 3–4-inch length were prepared.

Initially, the samples underwent thorough washing with various solvents to eradicate any traces of oil, saltwater, and potential contaminants, followed by drying in an oven. Laboratory measurements were subsequently performed under ambient conditions, which included evaluating bulk density, porosity, and permeability.

In addition, several electrical measurements, specifically Formation Resistivity Factor (FRF) and Formation Resistivity Index (FRI), were carried out. Overburden tests were also conducted to evaluate the impact of pressure and stress on rock properties.

Table 1 enumerates the distinct measurements made during the study, offering a comprehensive overview of the laboratory analysis process. Further, Table 2 presents the basic rock properties assessed, namely, porosity, permeability, and grain density. These properties offer key insights into the reservoir's performance potential and overall quality.

Table 1.

Core data available from surveyed well.

| Well Name | Test | Number of samples |

|---|---|---|

| A | Porosity, permeability and grain density | 313 |

| FRF and FRI | 10 | |

| Overburden | 15 |

Table 2.

Core plug porosity, permeability and grain density in the investigated borehole.

| Formation | Porosity (%) |

Permeability (mD) |

Grain density (g/cm3) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | Mean | |

| Sarvak | 3.64 | 26.42 | 9.77 | 0.01 | 22.08 | 0.66 | 2.67 | 2.74 | 2.70 |

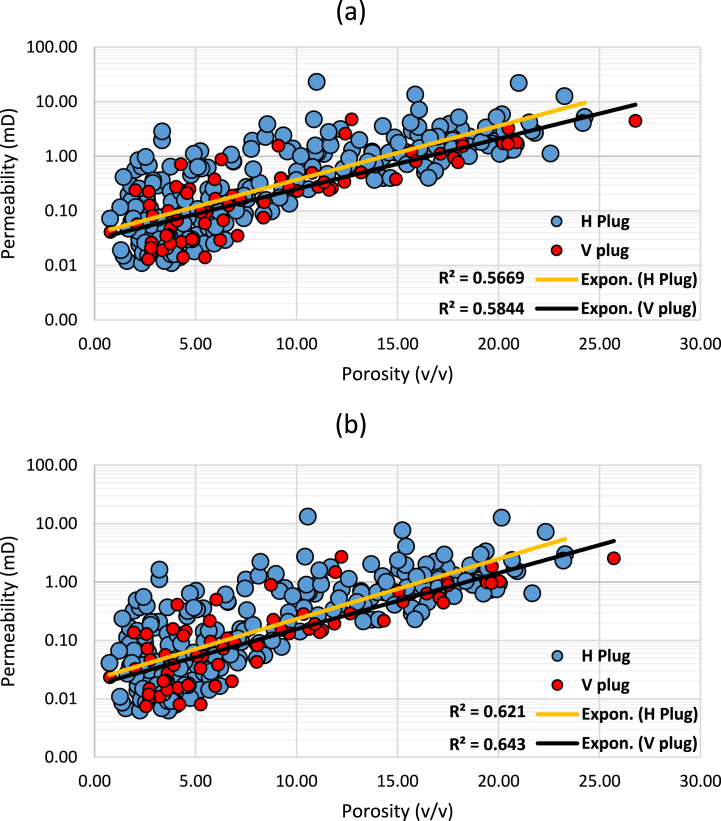

Fig. 4 presents a graphical representation of variations in basic rock properties within the Sarvak Formation. The grain density results in particular suggest a relatively low carbonate formation characterized by average petrophysical properties. This nuanced understanding of the Sarvak Formation contributes to our broader comprehension of the reservoir's complexity and its prospective productivity.

Fig. 4.

Core analysis results of the Sarvak Formation, illustrated across three panels. (a) Displays the variation in porosity, with values corresponding to both horizontal (H) and vertical (V) plugs. (b) Demonstrates permeability differences, again comparing the horizontal and vertical plugs. (c) Presents the grain density values for each plug orientation. The horizontal and vertical plug orientations are denoted as ‘H Plug’ and ‘V Plug’ respectively in each panel.

A comprehensive understanding of the reservoir rock's pore structures was aimed to be achieved through several petrographical analyses. Twenty-seven thin sections stained with Alizarin Red-S were prepared to differentiate between calcite and dolomite lithologies, following the method proposed by Dickson (1965) [43].

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) analysis was performed on forty-six samples, facilitating the identification of various rock components, matrix, microporosity, and microstructures. Detailed examinations were conducted on key features of the reservoir rocks, such as pore spaces and fractures. The SEM analysis was executed using a scanning electron microscope in the Core Analysis Laboratory at Amirkabir University.

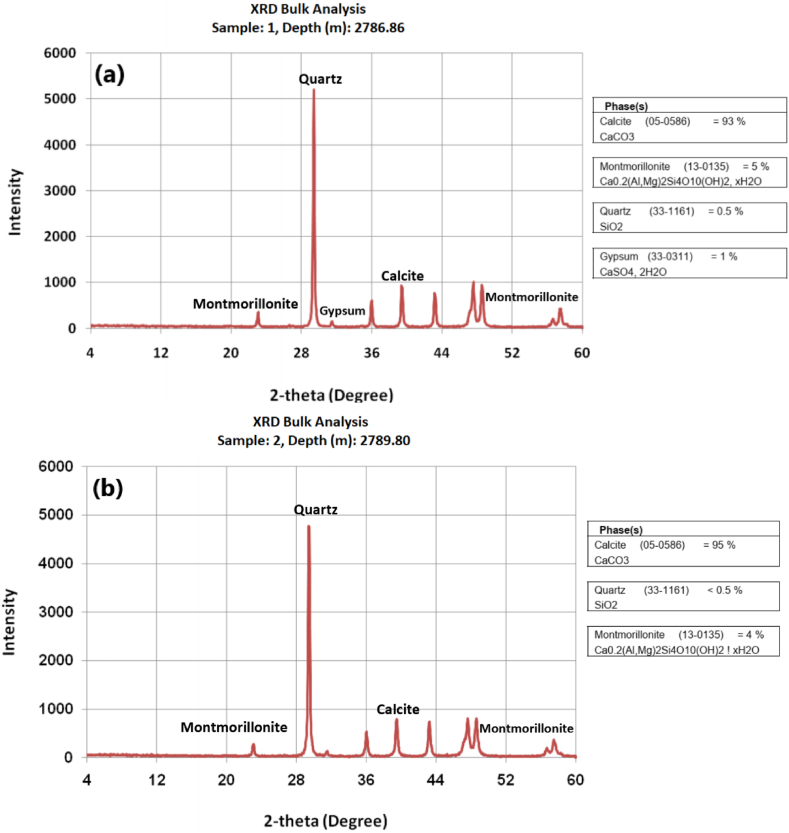

Thirty-seven bulk X-ray diffraction (XRD) samples were analyzed to identify the primary minerals within the investigated samples. Calcite was found to be the dominant mineral in the samples through the bulk XRD analysis, with dolomite being the second most abundant. Traces of other minerals, such as montmorillonite and quartz, were also detected. The XRD analysis was conducted at the Amirkabir University Core Analysis Laboratory on a Philips PW 1800 X-ray diffractometer, operating at 40 kV and 30 mA using Cu-Kα radiation.

In addition to the petrographical analysis, the full suite logs, including gamma, density, acoustic, neutron, and resistivity logs, was utilized from the surveyed wells. Table 3 details the specific logs made available for this study. This multi-faceted approach ensured a thorough understanding of the Sarvak Formation's productive potential was achieved.

Table 3.

Available logs.

| Well Name | Logs |

|---|---|

| A | BS, CALI, SGR, CGR, NPHI, RHOB, PEF, DRHO, DT, RT10, RT30, RT90, RXO, RT, VDL |

The quality of well logs is intrinsically tied to the well's condition. Generally, when the borehole integrity is maintained, as indicated by the caliper log, the reliability and quality of log measurements are considerably enhanced. The quality of logs is likely compromised in areas where the borehole wall exhibits washouts, especially in clayey and dense limestone sections. For instance, density logs in such areas often present unrealistic values and deteriorated quality.

In response to such challenges, alternative methods are employed; the sonic (acoustic) log, for instance, is used to estimate porosity across the affected intervals. The photoelectric factor (PEF) log, however, is particularly susceptible to interference from barite present in drilling muds. Hence, it was excluded from the petrophysical formation analysis in this study.

To enhance data quality, all available logs underwent rudimentary processing, including noise filtering and interpolation, to eliminate data aberrations such as gaps and spikes.

Certain intervals in well A demonstrated washouts, and the corresponding uncertainty associated with the well log data during the petrophysical evaluation of these intervals was acknowledged as high. Upon close inspection of the well logs' quality, it was concluded that, with the exception of the PEF log, all other logs offered satisfactory quality and were deemed fit for the study.

3.2. Zonation

The process of reservoir zonation in this study was underpinned by a broad spectrum of available data, including lithological characteristics, core and thin-section studies, sequence stratigraphy, and log interpretation.

Historically, the distribution of facies within the reservoir was assumed to be random. However, subsequent research revealed that the variability in facies within the formation is linked to sea-level fluctuations during the Cretaceous period. Thus, our studies on core samples led to the stratigraphic sequencing of the Sarvak Formation into seven distinct zones.

This method proved to be effective for the zonation of the Sarvak Formation, with each zone representing a unique sequence of strata and carrying its own set of lithological and petrophysical properties. The specifics of the Sarvak Formation's zonation, including the thickness of each zone, are tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4.

The zonation of Sarvak Formation for well A.

| Zone name | Interval (m) | Thickness (m) |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | 2722.8–2746.8 | 24 |

| S2 | 2746.8–2853.4 | 106.6 |

| S3 | 2853.4–2888.3 | 34.9 |

| S4 | 2888.3–2955.5 | 67.2 |

| S5 | 2955.5–3044.2 | 88.7 |

| S6 | 3044.2–3176.6 | 132.4 |

| S7 | 3176.6–3392.4 | 215.8 |

3.3. Lithology identification

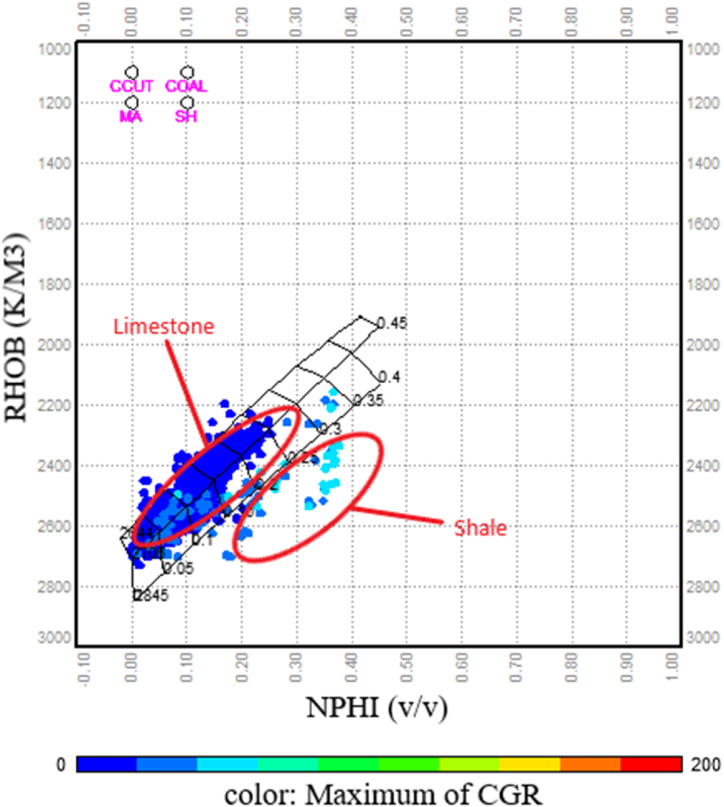

The identification of petrological types and clay minerals in the Sarvak Formation was accomplished through neutron and density cross-plotting and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) testing. As depicted in Fig. 5, the cross-plot results indicate limestone as the prevailing lithofacies in the formation, albeit with minor inclusions of shale and dolomite.

Fig. 5.

Neutron - density cross plot.

This lithological characterization is further corroborated by the results of 77 XRD analyses, demonstrating calcite to be the most abundant mineral present in the Sarvak Formation. Moreover, trace minerals such as dolomite, montmorillonite, quartz, and gypsum were discerned through these XRD examinations. Fig. 6 presents the XRD analysis of two representative samples, further highlighting the mineralogical composition of the Sarvak Formation.

Fig. 6.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) test results for two distinct samples taken from well A. (a) The sample contains 93% Calcite, 5% Montmorillonite, 0.5% Quartz, and 1% Gypsum. (b) This sample comprises 95% Calcite, 4% Montmorillonite, 0.5% Quartz, and 1% Gypsum.

3.4. Petrophysical evaluation

Petrophysical evaluation plays a crucial role in determining various reservoir rock properties such as porosity, shale volume, and water saturation [[44], [45], [46]]. This process often necessitates the use of dedicated petrophysical software, like Geolog, for proper data management and quality control. Raw data from various sources are loaded into the software, where they undergo an environmental correction for accuracy and reliability. The processed data is subsequently used to calculate vital rock properties, with the Multimin method employed to facilitate multi-mineral analysis [47]. The results from this sophisticated algorithm help ascertain the exact proportions of minerals in mixed lithologies and identify potential pay zones in complex reservoirs [45].

This method's efficacy is particularly pronounced in the case of unconventional reservoirs, where conventional log interpretation methods might be insufficient [44]. Once the computations are complete, the results are calibrated against core measurements for validation. Fig. 7, Fig. 8 exemplify the practical procedure of petrophysical evaluation for a studied well and provide an overview of the resulting data. Detailed parameters for each zone are discussed in subsequent sections.

Fig. 7.

The procedure of petrophysical evaluation.

Fig. 8.

An overview of the petrophysical evaluation results.

3.4.1. Shale volume assessment

The volume of shale is a vital parameter in petrophysical evaluations and reservoir quality studies as it represents the clay mineral content in the reservoir. The accuracy of several parameters such as porosity, fluid saturation, lithology, and permeability hinges on the accurate determination of shale volume.

Table 5 presents the calculated shale volume for the Sarvak Formation. The arithmetic average of the overall shale volume in the Sarvak Formation is 0.07, suggesting a predominantly clean formation. According to the results, the highest average volumes of shale are found in zones S1 and S6, while zones S7 and S4 contain the lowest average shale volume.

Table 5.

Shale volume, effective porosity, permeability and water saturation for different zones in Sarvak Formation.

| Zone | Shale volume (v/v) |

Effective porosity (v/v) |

Permeability (md) |

Water saturation (v/v) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | Mean | |

| S1 | 0.03 | 0.66 | 0.19 | 0.005 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.99 | 0.70 |

| S2 | 0 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 21.0 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.45 |

| S3 | 0 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 4.60 | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.85 | 0.40 |

| S4 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 17.4 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.64 | 0.29 |

| S5 | 0 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 8.40 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.58 |

| S6 | 0 | 0.90 | 0.08 | 0.006 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 44.8 | 4.38 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.72 |

| S7 | 0 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 105 | 4.98 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.77 |

| Total | 0 | 0.90 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 105 | 2.66 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.61 |

3.4.2. Porosity evaluation

Porosity, defined as the ratio of pore volume to total rock volume, is a critical property of reservoirs. The effective porosity, specifically associated with interconnected pores, facilitates fluid movement through pore throats. This effective porosity was computed using neutron, sonic, and density logs in accordance with the Multimin method. It's noteworthy that in intervals affected by washouts or breakouts, where high uncertainty in neutron and density logs is observed, the sonic log is preferred for porosity calculation.

Following these evaluations, porosity was determined across the well, and the results are presented in Table 5. Notably, zones S7 and S4 exhibit the highest arithmetic mean effective porosity, with average values of 0.13 and 0.11, respectively. Conversely, zones S1 and S2 feature the lowest mean effective porosity values.

3.4.3. Permeability assessment

Permeability is a crucial factor in the evaluation of hydrocarbon reservoirs as it denotes the potential of fluid flow through porous media. Traditionally, permeability is assessed through core experiments, well tests, or NMR logs. However, an alternative approach involves employing artificial neural networks (ANNs) trained on conventional logs and core data [48].

Inspired by biological neural networks, ANNs are a class of numerical optimization algorithms functioning as non-linear dynamic systems. ANNs learn to recognize patterns through a training process, which involves providing a set of input values and the corresponding desired output values. Throughout this process, ANNs implicitly formulate their own complex prediction function. Once trained, they can be applied to novel input data to predict output values.

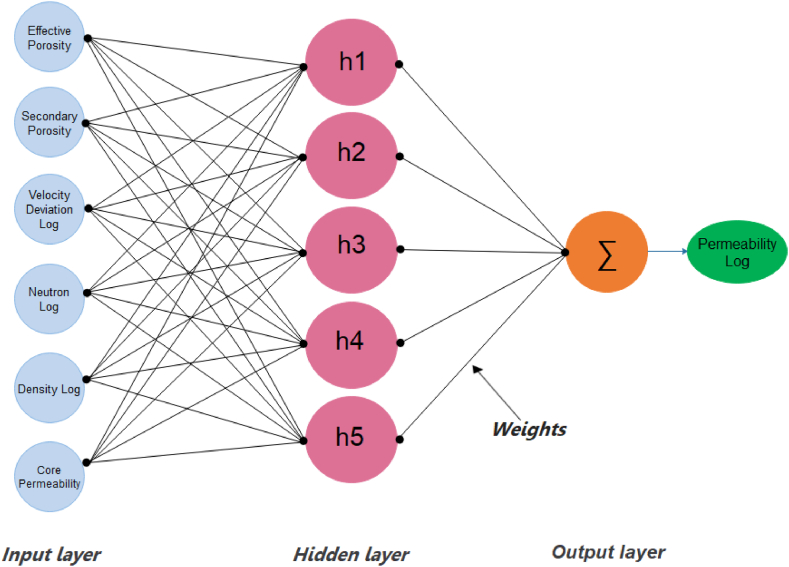

Among various types of ANNs, Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP) are widely used to model diverse reservoir properties. An MLP contains several layers, namely the input layer, output layer, and one or more hidden layers. The number of neurons in the input layer corresponds to the number of input variables, while the output layer often contains a single neuron.

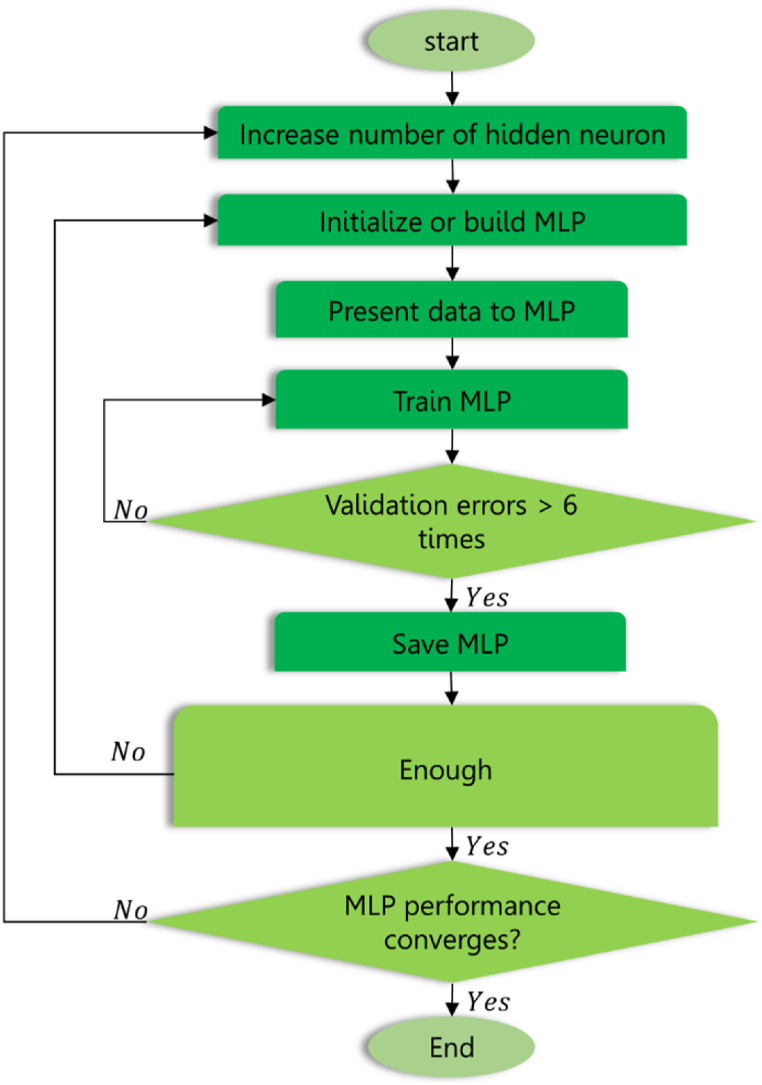

The hidden layer(s), residing between the input and output layers, require optimization in terms of their number and neurons to establish an effective connection between the inputs and the model output. To compute the value of each neuron in the output and hidden layers, the value of each neuron in the preceding layer is multiplied by a certain weight. A bias term is added to this sum, and the resulting values are passed through a nonlinear activation function [49,50]. The MLP flowchart is depicted in Fig. 9, while Table 6 presents the characteristics of the MLP network utilized in this study, featuring two hidden layers and the optimal parameter values obtained from the hyperparameter optimization process.

Fig. 9.

Schematic of MLP workflow.

Table 6.

Architecture parameters of MLP network.

| Network type | Multilayer perceptron |

|---|---|

| Training function | Levenberg-Marquardt backpropagation |

| Number of layers | 3 |

| Number of 1st hidden layer neuron | 3 |

| Transfer function of 1st hidden layer | TANSIG |

| Number of 2nd hidden layer neuron | 5 |

| Transfer function of 2nd hidden layer | TANSIG |

| Number of output layer neuron | 1 |

| Transfer function of output layer | PURELIN |

| Performance function | MSE |

| Other parameters | Default |

In the current study, a multilayer perceptron (MLP) has been employed for predicting the permeability log. The inputs used for this prediction included logs of effective porosity, secondary porosity, velocity deviation log (VDL), neutron, density, and core permeability data.

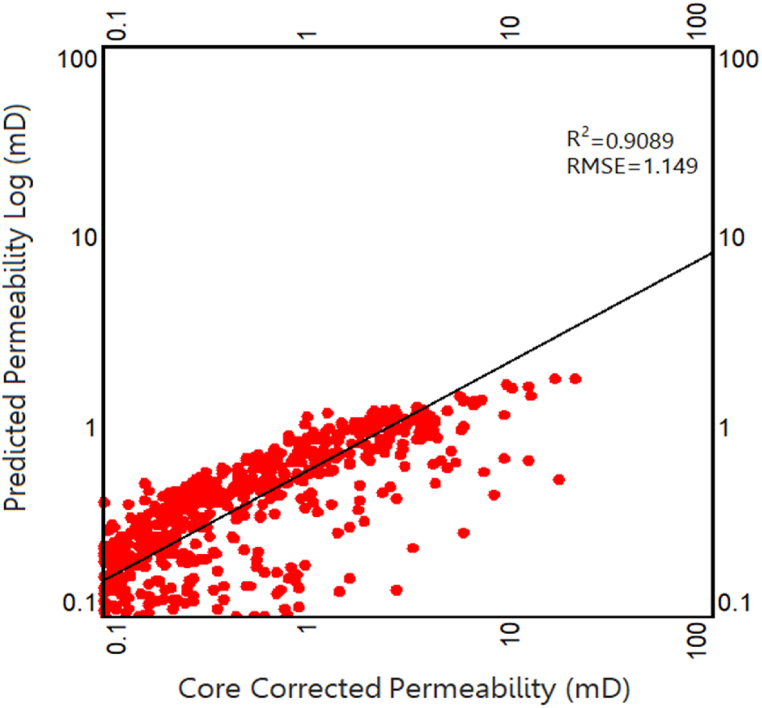

Through iterative analysis of various configurations, it was determined that a structure with one hidden layer and five neurons within it yielded optimal results. This optimized structure of the MLP network is depicted in Fig. 10. The resulting predicted permeability log correlated with the core-corrected permeability data with a correlation coefficient of 0.9089, and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 1.149, denoting a high level of prediction accuracy.

Fig. 10.

Schematic form of MLP network structure.

The relationship between the predicted permeability log and core-corrected permeability is shown in Fig. 11. This correlation substantiates the reliability of the MLP network's permeability log prediction, further validating the use of such a model in the evaluation of reservoir properties.

Fig. 11.

Correlation between predicted permeability log and core corrected permeability.

The permeability log was estimated using the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and the results are detailed in Table 9. To ensure the accuracy and validity of the estimated results, these were compared with core permeability measurements.

Table 9.

Water saturaion from FRI experiments and Indonesia Model.

| Depth (m) | Final water saturation of FRI (v/v) | Water saturation of petrophysical evaluation (v/v) |

|---|---|---|

| 2838.26 | 0.25 | 0.26 |

| 2885.06 | 0.49 | 0.56 |

| 2894.54 | 0.26 | 0.22 |

| 2903.10 | 0.28 | 0.25 |

| 2907.45 | 0.33 | 0.29 |

| 2916.54 | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| 2918.08 | 0.45 | 0.34 |

| 2921.74 | 0.36 | 0.30 |

| 2936.15 | 0.31 | 0.26 |

| 2939.40 | 0.29 | 0.24 |

Upon analyzing the estimated results in Table 9, it was observed that zones S7 and S6 exhibited the highest arithmetic average permeability values, with average permeabilities of 4.98 and 4.38 millidarcies (mD) respectively. Conversely, zones S1 and S3 presented the lowest arithmetic average permeability values. This evaluation of the permeability across various zones provides crucial insights into the variable properties of the reservoir across different stratigraphic sections.

3.4.4. Core porosity and permeability validation

The porosity and permeability logs deduced from the study were validated using the plot of porosity and permeability derived from core experiments. To ensure accuracy in this comparative analysis, the data were converted from ambient to reservoir conditions.

A total of fifteen measurements of porosity and permeability were conducted under overburden conditions. These results were then juxtaposed with the measurements obtained under ambient conditions. From this comparison, correction coefficients of 0.96 and 0.57 were determined for porosity and permeability, respectively.

These correction coefficients were applied across all data collected under ambient conditions, specifically for porosity and permeability, to ascertain the basic properties of the reservoir under reservoir conditions. The porosity and permeability values under both ambient and reservoir conditions are tabulated in Table 7, Table 8, respectively.

Table 7.

Values of porosity in ambient and reservoir conditions.

| Plug ID | Core depth (m) | Ambient porosity (%) | Net confining pressure (psi) | Reservoir porosity (%) | Fraction of origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2829.87 | 10.63 | 5817 | 10.10 | 0.95 |

| 2 | 2844.90 | 9.90 | 5875 | 9.41 | 0.95 |

| 3 | 2866.50 | 7.28 | 5957 | 6.85 | 0.94 |

| 4 | 2889.66 | 7.03 | 6046 | 6.61 | 0.94 |

| 5 | 2895.10 | 16.28 | 6066 | 15.63 | 0.96 |

| 6 | 2899.88 | 16.25 | 6085 | 15.60 | 0.96 |

| 7 | 2905.37 | 8.38 | 6106 | 8.04 | 0.96 |

| 8 | 2909.63 | 15.82 | 6122 | 15.19 | 0.96 |

| 9 | 2917.37 | 16.05 | 6152 | 15.41 | 0.96 |

| 10 | 2919.91 | 13.80 | 6161 | 13.25 | 0.96 |

| 11 | 2921.13 | 13.67 | 6166 | 13.13 | 0.96 |

| 12 | 2922.93 | 24.26 | 6173 | 23.54 | 0.97 |

| 13 | 2931.93 | 16.45 | 6207 | 15.96 | 0.97 |

| 14 | 2936.54 | 15.95 | 6225 | 15.48 | 0.97 |

| 15 | 2938.85 | 12.48 | 6234 | 12.11 | 0.97 |

| Average: | 0.96 |

Table 8.

Values of permeability in ambient and reservoir conditions.

| Plug ID | Core depth (m) | Ambient permeability (mD) | Net confining pressure (psi) | Reservoir permeability (mD) | Fraction of origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2829.87 | 0.58 | 5817 | 0.29 | 0.50 |

| 2 | 2844.90 | 0.30 | 5875 | 0.15 | 0.50 |

| 3 | 2866.50 | 0.66 | 5957 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| 4 | 2889.66 | 0.10 | 6046 | 0.02 | 0.19 |

| 5 | 2895.10 | 1.48 | 6066 | 1.11 | 0.75 |

| 6 | 2899.88 | 0.81 | 6085 | 0.60 | 0.74 |

| 7 | 2905.37 | 0.05 | 6106 | 0.03 | 0.55 |

| 8 | 2909.63 | 0.96 | 6122 | 0.60 | 0.62 |

| 9 | 2917.37 | 0.35 | 6152 | 0.19 | 0.53 |

| 10 | 2919.91 | 0.20 | 6161 | 0.15 | 0.75 |

| 11 | 2921.13 | 0.62 | 6166 | 0.40 | 0.64 |

| 12 | 2922.93 | 4.24 | 6173 | 3.65 | 0.86 |

| 13 | 2931.93 | 0.35 | 6207 | 0.22 | 0.62 |

| 14 | 2936.54 | 0.26 | 6225 | 0.17 | 0.65 |

| 15 | 2938.85 | 0.36 | 6234 | 0.19 | 0.52 |

| Average: | 0.57 |

Fig. 12(a)–(b) demonstrate the correlation between core porosity and core permeability, both before and after the application of the correction factor. Fig. 12(a) shows the initial relationship between core porosity and core permeability, while Fig. 12(b) presents the same relationship but after the correction factors have been applied. This representation enables a direct comparison between core measurements of porosity and permeability with those determined from log data.

Fig. 12.

Relationship between core porosity and core permeability, before (a) and after (b) the application of correction factors.

Fig. 13 presents the core porosity and permeability values under both ambient and reservoir conditions. These are contrasted against the effective porosity and permeability logs. Observably, the porosity and permeability values under reservoir conditions exhibit a more favorable congruence with the effective porosity and permeability as inferred from logs. This trend affirms the importance of the correction factor in ensuring the accuracy and relevance of log-derived data under actual reservoir conditions.

Fig. 13.

Comparison of core porosity and permeability in ambient and reservoir conditions with effective porosity and permeability logs.

3.4.5. Water saturation evaluation

The Indonesian method, as developed by Poupon and Leveaux in 1971 [51], is implemented in this study for the calculation of water saturation within the hydrocarbon reservoirs in the context of shaly sand formations. Traditional approaches, such as Archie's, Simandoux's, Dual Water Model, or Waxman-Smits' equations, albeit valuable, may fail to yield accurate results when deployed in more complex rock matrices [51,52].

The Indonesian method introduces modifications to Archie's equation, thereby accounting for conductivity effects associated with clay-bound water and other conductive components in the reservoir rock [13]. In simpler terms, it corrects the distortions in resistivity measurements brought about by the presence of shales, thereby improving the accuracy of water saturation calculations [53].

The choice of the Indonesian method for this study is likely due to its suitability for reservoirs characterized by substantial shale layers. It can provide a more precise estimation of water saturation, given that it factors in the influence of shale or clay content within the reservoir rock matrix [52,53].

However, the accuracy of the Indonesian method, like any other model, depends heavily on the selection of the correct parameters. Therefore, precise measurements of variables such as formation water resistivity and shale volume in the reservoir are critical for the effective application of this method. The mathematical representation of this concept is illustrated in Equation (1) [54].

| (1) |

where Sw is water saturation, Vsh is shale volume, Rsh is shale resistivity in ohmm, φ is porosity, m is cementation coefficient, n is saturation exponent, Rw is the formation water resistivity in ohmm. Rt is the uninvaded formation resistivity in ohmm.

The cementation coefficient (m) and the saturation exponent (n) were derived from core analysis tests, specifically from the results of the formation resistivity factor (FRF) and the formation resistivity index (FRI) experiments. These values are crucial parameters in the Indonesian method employed for calculating water saturation in the reservoir. In this study, m and n values of 1.98 and 2.38, respectively, were used. The resistivity of the formation water (Rw) was established as 0.037.

Calculations were subsequently performed to ascertain water saturation in various zones within the reservoir. The outcomes, as detailed in Table 5, indicate that zones S4 and S3 exhibit the lowest arithmetic average water saturation, while zones S7 and S6 display the highest levels. These variations in saturation highlight the heterogeneity of reservoir conditions, reinforcing the importance of detailed petrophysical evaluations in characterizing reservoir properties [13,54].

The water saturation results are compared with the water saturation measured from core tests, e.g., FRI experiments. Table 9 lists the water saturation obtained from the FRI experiment and Indonesia model. As seen, there is a relatively good correlation between the results.

Fig. 14 presents the water saturation log determined by the Indonesia model and calibrated with the results measured from FRI experiments.

Fig. 14.

Comparison of water saturation determined from FRI tests and Indonesia model.

3.5. Cut-off of petrophysical parameters

A cumulative frequency plot against reservoir properties is employed in this study to ascertain the cut-off values of petrophysical parameters. This approach allows for the calculation of the initial in-situ hydrocarbon content, drawing on parameters such as porosity, shale content, and water saturation. The equation used to calculate the volume of hydrocarbon reserves, referred to here as Equation (2), is as follows [55]:

| (2) |

where HIPi represents the amount of in-place hydrocarbon volume, i indicates the depth point, φi represents the porosity, Swi represents the reservoir water saturation, hi indicates the layer thickness is determined from the well log, and Ai is the reservoir area. The value of A is set to one due to the relative frequency and cumulative frequency of the reserve volume.

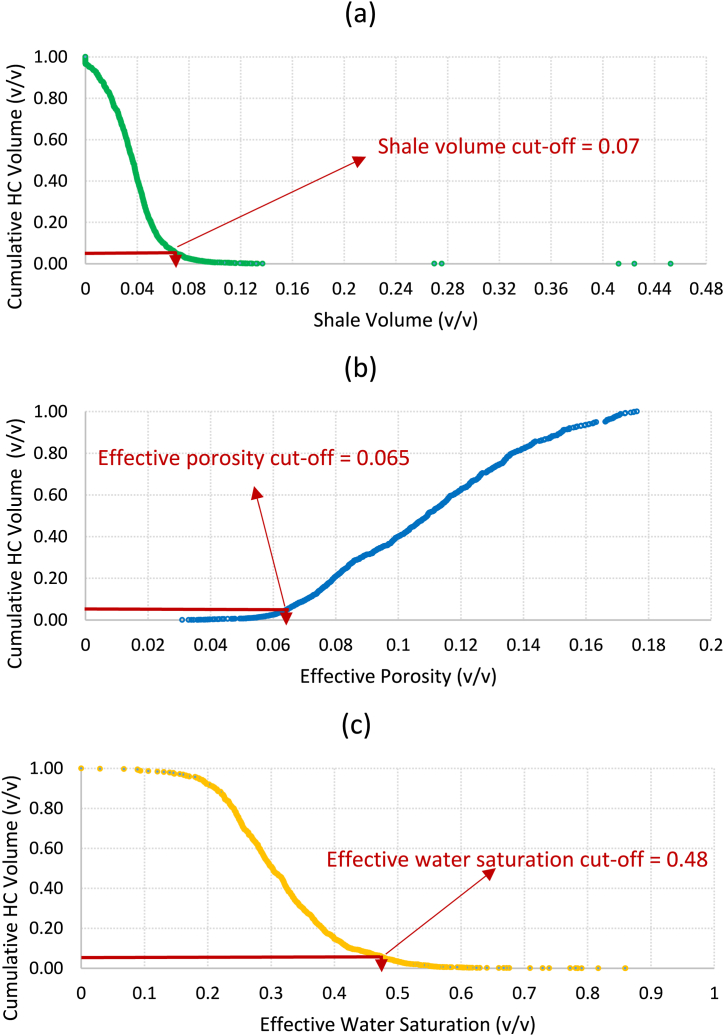

In the subsequent step, a cumulative frequency plot of reserve volume is generated against each determined parameter, such as shale volume, effective porosity, and water saturation. A cut-off criterion of 5% cumulative hydrocarbon volume is adopted for this analysis. However, specific values of 0.07 for shale volume, 0.065 for effective porosity, and 0.48 for effective water saturation are obtained, corresponding to the 5% cumulative hydrocarbon volume threshold. It is worth noting that a permeability value of 1 millidarcy (mD) was considered based on the standards for oil reservoirs [14].

Fig. 15 visually presents the cut-off calculations for shale volume (Fig. 15(a)), effective porosity (Fig. 15(b)), and water saturation (Fig. 15(c)), specifically at the 5% cumulative hydrocarbon threshold. This plot highlights the critical values at which the hydrocarbon volume exceeds 5% of the total cumulative volume, aiding in the determination of productive reservoir zones.

Fig. 15.

Cut-off calculations for (a) shale volume, (b) effective porosity, and (c) water saturation.

4. Results and discussion

The calculation of net pay is a methodical process that takes into account several key variables such as shale volume, porosity, and water saturation cut-off. Commencing with the calculation of shaleless carbonate layers, the minimum shale volume is set at 0.07. Consequently, the total net carbonate thickness is determined to be approximately 73% of the gross thickness.

The second stage of the calculation implements cut-offs for porosity and permeability, set at 6.5% and 1 mD respectively. These cut-offs aid in the calculation of the net reservoir layer across various zones.

Subsequently, the third stage requires a water saturation cut-off of 48%, which is utilized to compute the net pay for different zones. For a more detailed understanding, refer to Table 10, which catalogues the values of net carbonate, reservoir, and production thicknesses for different zones within the Sarvak Formation.

Table 10.

Values of net carbonate, reservoir and production thicknesses and the ratio of these thicknesses to the total thickness for each zone.

| Zone | Zone thickness (m) | Net carbonate thickness (m) | Net reservoir thickness (m) | Net pay thickness (m) | Carbonate N/G | Reservoir N/G | Pay N/G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 24 | 3.35 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 | 0 | 0 |

| S2 | 106.6 | 69.28 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 0.65 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| S3 | 34.9 | 29.41 | 0 | 0 | 0.84 | 0 | 0 |

| S4 | 67.2 | 65.82 | 14.47 | 14.47 | 0.98 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| S5 | 88.7 | 60.96 | 5.33 | 2.89 | 0.68 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| S6 | 132.4 | 84.58 | 56.38 | 0 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0 |

| S7 | 215.8 | 176.22 | 111.25 | 0 | 0.81 | 0.51 | 0 |

| Total | 669.6 | 489.6 | 189.89 | 19.81 | 0.73 | 0.29 | 0.03 |

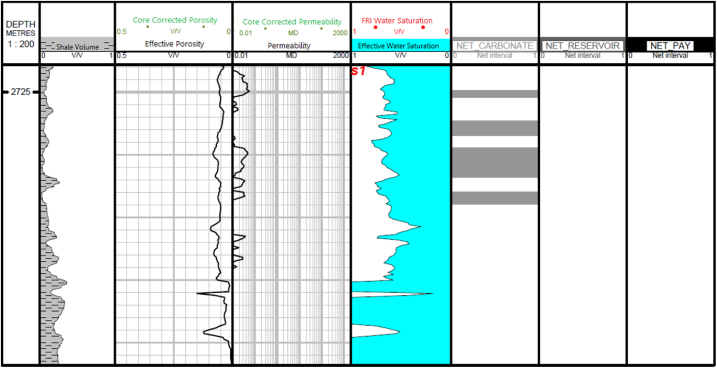

Fig. 16 presents a visual depiction of the net carbonate, reservoir, and productive layers, as shown in the logs. Upon examination, it is observed that only zones S2, S4, and S5 qualify as productive zones, whereas zones S1, S3, S6, and S7 are identified as non-reservoir or net pay layers. Furthermore, Fig. 17 indicates the frequency of net carbonate, net reservoir, and net pay layers for various zones within the Sarvak Formation.

Fig. 16.

An overview of the petrophysical evaluation for different zones in Sarvak formation.

Fig. 17.

Frequency of net carbonate, net reservoir, and net pay layers for different zones in Sarvak formation.

In the following sections, we provide a more exhaustive description and discussion of the individual characteristics pertaining to each zone in the Sarvak Formation.

4.1. Zone S1

Encompassing 24 m of the Sarvak Formation, Zone S1 exhibits a net carbonate thickness of 3.35 m. However, this zone does not qualify as a net reservoir or a productive layer, owing to its low porosity and high water saturation levels. The average effective porosity for Zone S1 stands at a mere 0.05, while the water saturation averages a significantly higher value of 0.70. In addition, the zone displays an average shale volume of 0.19, coupled with a relatively low average permeability of 0.01 mD.

An overview of the petrophysical evaluation for Zone S1, including parameters such as shale volume, porosity, water saturation, and permeability, can be viewed in Fig. 18. Although Zone S1 is a part of the Sarvak Formation, its petrophysical characteristics limit its potential as a productive layer. Further studies may be warranted to fully understand the underlying causes of its low porosity and high water saturation, and to potentially improve its productivity in the future.

Fig. 18.

An overview of the petrophysical evaluation for Zone S1.

4.2. Zone S2

Comprising 106.6 m of the Sarvak Formation, Zone S2 presents net carbonate, reservoir, and productive thicknesses of 69.28 m, 2.43 m, and 2.43 m, respectively. The average effective porosity in this zone is 0.06, with an average effective water saturation of 0.45, an average shale volume of 0.06, and an average permeability of 0.26 mD. Notably, while the water saturation is considerably low, the porosity is also relatively low, indicating specific challenges in this zone.

Results from thin sections reveal diagenetic phenomena such as cementation, compaction, and the presence of organic matter in the pore space, all of which have contributed to a reduction in effective porosity and permeability. This, in turn, results in a lower net pay reservoir in Zone S2. Fig. 19 provides an interpretation of the thin sections.

Fig. 19.

An overview of the final petrophysical evaluation for Zone S2. The thin section with a milliolid fossil (Packstone) (a), and with pore filled by organic matter and isopachous calcite cement (Packstone) (b).

A particular point of interest is the identification of a milliolid fossil at a depth of 2793.36 m, as shown in Fig. 19(a). This fossil appears deformed due to overburden and compaction, indicating a reduction in permeability at that depth. In Fig. 19(b), we observe that intergranular pores are filled with residual organic matter and isopachous calcite cement, resulting in a reduction of permeability and a lower quality of reservoir and production at that depth. The porosity here is 0.04, and the permeability is less than 0.01 mD. Both samples conform to the packstone category in the Dunham classification [56].

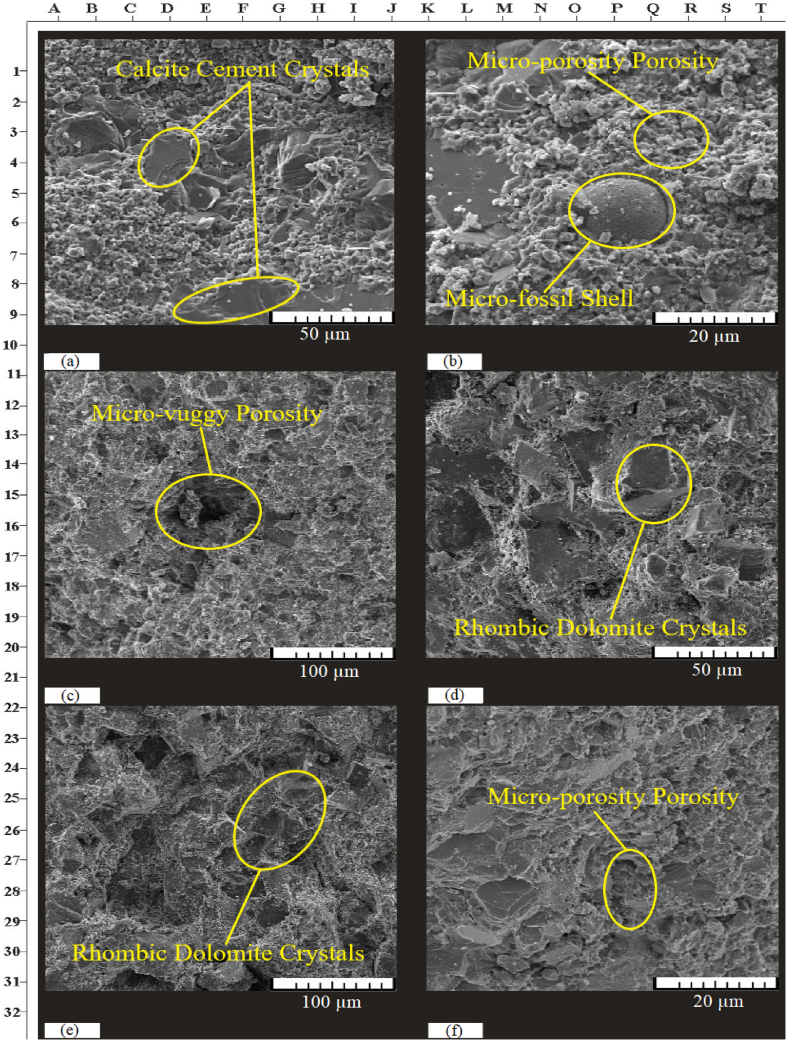

A more detailed SEM study, as shown in Fig. 20, was conducted at depths of 2807.6 m (Fig. 20(a)–(b)) and 2811.27 m (Fig. 20(c)–(f)). This analysis reveals the presence of calcite cement crystals (D4, G9), micro-porosity (R3, E2, F1), microfossil shell (Q7), micro‐vuggy porosity (F16, C28), and micro-porosity between micrite crystals (B23, Q29) in Fig. 20(a)–(f). Furthermore, rhombic dolomite crystals with no intercrystalline porosity (Q16, F27) are also observed in Fig. 20. These features contribute to a reduction in pore space, resulting in low permeability and compromised reservoir quality for Zone S2.

Fig. 20.

SEM photomicrographs for Zone S2, with observations taken at depths of (a) and (b) 2807.6 m and (c) to (f) 2811.27 m.

4.3. Zone S3

Zone S3 constitutes 34.9 m of the Sarvak Formation and has a total net carbonate thickness of 29.41 m. This zone's average effective porosity stands at 0.07, with an average effective water saturation of 0.40, average shale volume of 0.05, and average permeability of 0.12 mD. However, the permeability is low, preventing the identification of a net pay using the established cut-off of 1 mD.

Thin section studies were conducted to understand the reasons behind the poor quality of the pay zone in this area. Fig. 21 provides thin sections at specific depths (2864.51 m and 2882.05 m). Fig. 21(a) reveals a thin section with horsetail solution seams, while Fig. 21(b) displays the presence of radiaxial coarse calcite cement due to compaction from overburden pressure. These features contribute to a reduction in porosity and permeability, classifying Zone S3 as a low-quality pay zone. Both samples, as seen in Fig. 21(a)–(b), are classified as packstone according to the Dunham classification [56].

Fig. 21.

Petrophysical evaluation of Zone S3. Thin sections at specific depths depict (a) a horsetail solution seam (wackestone) and (b) radiaxial coarse calcite cement (packstone).

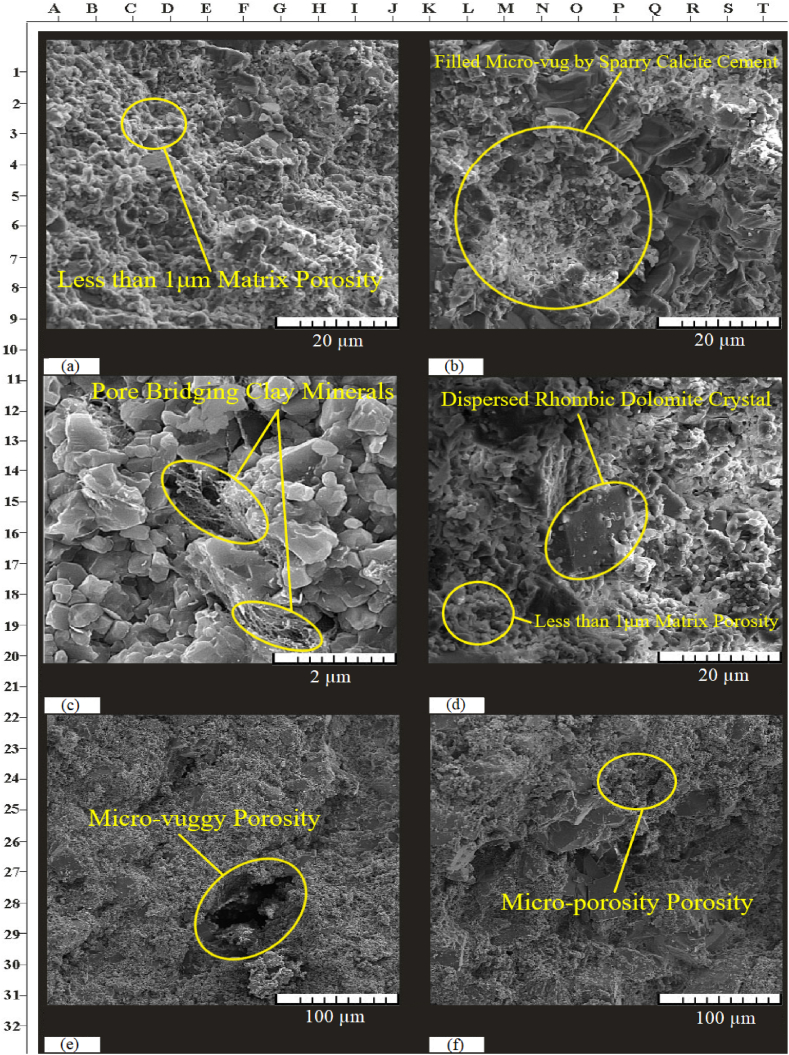

Additional SEM studies, represented in Fig. 22, were carried out at the stated depths. This analysis, as shown in panels 22(a) to 22(d) for the depth of 2857.08 m and panels 22(e) and 22(f) for the depth of 2860.09 m, reveals features including less than 1 μm matrix porosity (D3, L20), micro‐vugs filled with sparry calcite cement (O7, O3), pore-bridging clay minerals (Illite) (E15, G19), dispersed rhombic dolomite crystals (O16), dolomite crystals (O28), micro‐porosity (E27, O24), and micro-vuggy porosity (F29). These characteristics collectively contribute to the low reservoir quality of Zone S3, impacting its overall productivity.

Fig. 22.

SEM photomicrographs for the S3 zone at specified depths. Panels (a) to (d) correspond to a depth of 2857.08 m, while panels (e) and (f) illustrate the features at a depth of 2860.09 m.

4.4. Zone S4

Spanning 67.2 m of the Sarvak Formation, Zone S4 presents a total net carbonate thickness of 65.82 m and a net pay of 14.47 m. This zone showcases an average effective porosity of 0.11, an effective water saturation of 0.29, a shale volume of 0.04, and a permeability of 1 mD. Given that these values are all above the prescribed cut-offs, Zone S4 can be regarded as possessing relatively high quality.

Fig. 23 presents the results of a thin section study at specific depths (2898.71 m and 2936.67 m). Fig. 23(a) highlights intraparticle, intercrystalline, moldic, and vuggy porosities formed by the dissolution of skeletal packstone. Meanwhile, Fig. 23(b) showcases channel, matrix, and fracture porosities. Both samples, as illustrated in Fig. 23(a) and (b), are classified as crystalline according to the Dunham classification [56].

Fig. 23.

Petrophysical evaluation of Zone S4 through thin section analysis. Panel (a) displays intraparticle, intercrystalline, moldic, and vuggy porosities (crystalline), while panel (b) reveals channel, matrix, and fracture porosities (crystalline).

Fig. 24 showcases SEM studies conducted at the relevant depths. Panels 24(a) and 24(b) at the depth of 2931.23 m reveal features including moldic porosity (E5), micro‐vuggy porosity (K8, N6), and micro‐porosity in the matrix (G2, R5). Panels 24(c) to 24(f) at the depth of 2935.18 m display additional characteristics, such as micro‐vuggy porosity (B13, G27), moldic porosity with oil staining (P16), matrix porosity (O28, D24), and dispersed quartz crystals (O31). Collectively, these features revealed in Fig. 24 enhance the reservoir quality and productivity of Zone S4, indicating it as a promising zone for exploration and extraction activities.

Fig. 24.

SEM photomicrographs for the S4 zone at specified depths. Panels (a) and (b) correspond to a depth of 2931.23 m, while panels (c) to (f) illustrate the features at a depth of 2935.18 m.

4.5. Zones S5, S6, and S7

Zone S5 spans 88.7 m of the Sarvak Formation with net carbonate, reservoir, and pay layers measuring 60.96 m, 33.5 m, and 2.89 m, respectively. Despite exhibiting an average effective porosity of 0.08 and an average shale volume of 0.05, both of which point towards satisfactory quality, Zone S5 grapples with high effective water saturation and low permeability (0.3 mD). These factors negatively impact its net productive thickness, rendering it less than ideal in terms of overall quality.

Zone S6, on the other hand, comprises 132.4 m of the Sarvak Formation, with net carbonate and reservoir layers of 84.58 m and 56.38 m respectively. It lacks any net pay layer. Despite presenting robust figures for porosity (0.11) and permeability (4.34 mD), and a low shale content (0.08), Zone S6 faces the hurdle of high effective water saturation. Consequently, this zone lacks any significant oil accumulation.

Lastly, Zone S7 incorporates 215.8 m of the Sarvak Formation, with net carbonate and reservoir layers measuring 176.22 m and 111.25 m, respectively, but lacks any net pay. While it exhibits an average effective porosity of 0.09, a low average shale volume of 0.03, and an impressive average permeability of 4.98 mD, it is hampered by high effective water saturation, meaning that it contains no economically viable oil.

Fig. 25 offers a comprehensive view of the final petrophysical evaluation for Zones S5, S6, and S7. In summary, despite some promising parameters, these zones exhibit certain challenges, primarily related to water saturation, that limit their oil yield potential.

Fig. 25.

An overview of the final petrophysical evaluation for zones S5, S6, and S7.

5. Conclusions

In this detailed study, the reservoir quality and the productive layers of the Sarvak Formation were examined, and critical insights were uncovered, which hold significant implications for future research and field operations.

The Sarvak Formation, primarily composed of limestone with minor proportions of shale and thin layers of dolomite, is displayed as having a complex and heterogeneous geological structure. Seven distinct zones within the formation were identified through a thorough stratigraphic sequence analysis and study of varying diagenetic phenomena. Evidence of clean lithology is provided by this heterogeneity, along with the relatively low shale volume across the formation. Moreover, the accuracy and reliability of this formation evaluation are underscored by the strong correlation between petrographic and petrophysical findings.

A generally high reservoir quality in the Sarvak Formation was revealed through the examination of thin sections. However, layers of complexity are added due to the presence of micro-porosities and diagenetic events such as cementation and compaction, resulting in a heterogeneous permeability distribution. This effect is observed with notably poor permeability being displayed in certain intervals in the Sarvak Formation.

The identification of net carbonate, reservoir, and pay zones was facilitated by the establishment of cut-off criteria for shale content, porosity, permeability, and water saturation. Net pay layers were discovered in Zones S4, S5, and S2, suggesting their potential profitability. Conversely, despite some favorable parameters, Zones S1, S3, S6, and S7 were found not to be economically viable for hydrocarbon accumulation, primarily due to high effective water saturation.

Substantial implications for future research are presented by these findings. The incorporation of geochemical studies to further explore potential barriers within the reservoir and understand their impact on identifying productive zones would benefit future investigations. Furthermore, if data on reservoir fluid viscosity are available, it is recommended that this parameter be included in the determination of cut-off points. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the reservoir's potential and pave the way for improved strategies in hydrocarbon exploration and extraction.

Author contribution statement

Ahmad Azadivash: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper. Mehdi Shabani: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data. Vali Mehdipour: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. Ahmad Reza Rabbani: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Data availability statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acronyms

- ANN

Artificial Neural Network

- BS

Bit Size

- CALI

Caliper

- CGR

Computed Gamma Ray

- DRHO

Density Correction

- DST

Drill Stem Test

- DT

Sonic

- FRF

Formation Resistivity Factor

- FRI

Formation Resistivity Index

- H Plug

Horizontal Plug

- HIP

In-place Hydrocarbon Volume

- MLP

Multilayer Perceptron

- NPHI

Neutron Porosity

- PEF

Photoelectric Factor

- RHOB

Bulk Density

- RT

Deep Resistivity

- Rw

Water Resistivity

- RXO

Shallow Resistivity

- SEM

Scanning Electron Microscope

- SGR

Spectral Gamma Ray

- Sw

Water Saturation

- V Plug

Vertical Plug

- VDL

Variable Density Log

- XRD

X‐Ray Diffraction

Nomenclatures

- A

Reservoir area m2

- h

Layer thickness m

- K

Permeability md

- m

Cementation coefficient -

- n

Saturation exponent -

- Rsh

Shale resistivity ohmm

- Vsh

Shale volume v/v

- φ

Porosity v/v

References

- 1.Lucia F.J. Rock-fabric/petrophysical classification of carbonate pore space for reservoir characterization. Am. Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Bull. 1995;79(9):1275–1300. doi: 10.1306/7834D4A4-1721-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jahn F., Cook M., Graham M. Elsevier; 2008. Hydrocarbon Exploration and Production. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiab D., Donaldson E.C. Gulf professional Publishing; 2015. Petrophysics: Theory and Practice of Measuring Reservoir Rock and Fluid Transport Properties. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worthington P.F., Cosentino L. The role of cutoffs in integrated reservoir studies. SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 2005;8(4):276–290. doi: 10.2118/84387-PA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun H., Belhaj H., Tao G., Vega S., Liu L. Rock properties evaluation for carbonate reservoir characterization with multi-scale digital rock images. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019;175:654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2018.12.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rui Z., Metz P.A., Reynolds D.B., Chen G., Zhou X. Historical pipeline construction cost analysis. Int. J. Oil Gas Coal Technol. 2011;4(3):244–263. doi: 10.1504/IJOGCT.2011.040838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suyun H., Wenzhi Z., Lianhua H., Zhi Y., Rukai Z., Songtao W.…Xu J. Development potential and technical strategy of continental shale oil in China. Petrol. Explor. Dev. 2020;47(4):877–887. doi: 10.1016/S1876-3804(20)60103-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin F., Gao Y., Zhang H., Sun B., Chen Y., Gao D., Zhao X. Comprehensive evaluation of gas production efficiency and reservoir stability of horizontal well with different depressurization methods in low permeability hydrate reservoir. Energy. 2022;239 doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2021.122422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y., Zhang X., Shi J., Guo W., Kang L., Yu R.…Pan M. A reservoir quality evaluation approach for tight sandstone reservoirs based on the gray correlation algorithm: a case study of the Chang 6 layer in the W area of the as oilfield, Ordos Basin. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2021;39(4):1027–1056. doi: 10.1177/0144598721998510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gier S., Worden R.H., Johns W.D., Kurzweil H. Diagenesis and reservoir quality of Miocene sandstones in the Vienna basin, Austria. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2008;25(8):681–695. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2008.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakimi M.H., Shalaby M.R., Abdullah W.H. Diagenetic characteristics and reservoir quality of the Lower Cretaceous Biyadh sandstones at Kharir oilfield in the western central Masila Basin, Yemen. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012;51:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Sharawy M.S., Nabawy B.S. Integration of electrofacies and hydraulic flow units to delineate reservoir quality in uncored reservoirs: a case study, Nubia Sandstone Reservoir, Gulf of Suez, Egypt. Nat. Resour. Res. 2019;28:1587–1608. doi: 10.1007/s11053-018-9447-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asquith G., Gibson C. American Association of Petroleum Geologists; 1982. Basic Well Log Analysis for Geologists. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Worthington P.F. Net pay—what is it? What does it do? How do we quantify it? How do we use it? SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 2010;13(5):812–822. doi: 10.2118/123561-PA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davarpanah A., Mirshekari B., Jafari Behbahani T., Hemmati M. Integrated production logging tools approach for convenient experimental individual layer permeability measurements in a multi-layered fractured reservoir. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2018;8:743–751. doi: 10.1007/s13202-017-0422-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riazi Z. Application of integrated rock typing and flow units identification methods for an Iranian carbonate reservoir. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018;160:483–497. doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2017.10.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millikan C.V. Use of gas meters for determination of pay strata in oil sands. Trans. AIME. 1925;(1):183–195. doi: 10.2118/925183-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connell D.L., Coates J.A., Frost D.A. Development of a fluorimetric method for detection of pay zones during drilling with invert muds. SPE Form. Eval. 1986;1(6):595–602. doi: 10.2118/13005-PA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews C.S., Russell D.G. vol. 1. Henry L. Doherty Memorial Fund of AIME; New York: 1967. Pressure Buildup and Flow Tests in Wells; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathur N., Raju S.V., Kulkarni T.G. Improved identification of pay zones through integration of geochemical and log data: a case study from Upper Assam basin, India. Am. Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Bull. 2001;85(2):309–323. doi: 10.1306/8626C7CB-173B-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flower J.G. Use of sonic-shear-wave/resistivity overlay as a quick-look method for identifying potential pay zones in the Ohio (Devonian) Shale. J. Petrol. Technol. 1983;35(3):638–642. doi: 10.2118/10368-PA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snyder R.H. Fall Meeting of the Society of Petroleum Engineers of AIME. OnePetro; 1971. A review of the concepts and methodology of determining net pay. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deakin M., Manan W. SPE Asia Pacific Conference on Integrated Modelling for Asset Management. OnePetro; 1998. The integration of petrophysical data for the evaluation of low contrast pay. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gautama A., Grivot P., Gunawan S., Larrouquet F. 2003. Horizontal Wells as a Solution to Produce Gas Bearing Low Permeability Sands in the G Zone Reservoirs of the Tambora Gas Field, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korolev E.A., Eskin A.A., Khuzina A.F., Barieva E.R., Ilaeva A.A. IOP Conference Series: Environ. Earth Sci. (Vol. 808, No. 1, P. 012026) IOP Publishing; 2021. Assessment of the geological factors influence on the oil-productive of terrigenous reservoirs of the Vereyian horizon of the Melekess depression. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choquette P.W., Pray L.C. Geologic nomenclature and classification of porosity in sedimentary carbonates. AAPG Bull. 1970;54(2):207–250. doi: 10.1306/5D25C98B-16C1-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucia F.J. Petrophysical parameters estimated from visual descriptions of carbonate rocks: a field classification of carbonate pore space. J. Petrol. Technol. 1983;35(3):629–637. doi: 10.2118/10073-PA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucia F.J., Kerans C., Jennings J.W., Jr. Carbonate reservoir characterization. J. Petrol. Technol. 2003;55(6):70–72. doi: 10.2118/82071-JPT. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivanova A., Mitiurev N., Cheremisin A., Orekhov A., Kamyshinsky R., Vasiliev A. Characterization of organic layer in oil carbonate reservoir rocks and its effect on microscale wetting properties. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47139-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radwan A.E., Trippetta F., Kassem A.A., Kania M. Multi-scale characterization of unconventional tight carbonate reservoir: insights from October oil filed, Gulf of Suez rift basin, Egypt. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021;197 doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2020.107968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y., Zhang L., He J., Zhang H., Zhang X., Liu X. Fracability evaluation method of a fractured-vuggy carbonate reservoir in the shunbei block. ACS Omega. 2023 doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c02000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi X., Cui Y., Xu S., Wang R., Zhang H. Offshore Technology Conference Asia. OnePetro; 2022. Determination of fluid properties and reservoir net pay cutoffs by production logging and conventional logs in exploration wells: a case study of the granite fractured reservoir in JZ oilfiled in Bohai sea. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alatefi S., Abdel Azim R., Alkouh A., Hamada G. Integration of multiple bayesian optimized machine learning techniques and conventional well logs for accurate prediction of porosity in carbonate reservoirs. Processes. 2023;11(5):1339. doi: 10.3390/pr11051339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang T., Cao Y., Wang Y., Liu K., He C., Zhang S. Determining permeability cut-off values for net pay study of a low-permeability clastic reservoir: a case study of the Dongying Sag, eastern China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019;178:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2019.03.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senosy A.H., Ewida H.F., Soliman H.A., Ebraheem M.O. Petrophysical analysis of well logs data for identification and characterization of the main reservoir of Al Baraka Oil Field, Komombo Basin, Upper Egypt. SN Appl. Sci. 2020;2:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s42452-020-3100-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al Jawad M.S., Tariq B.Z. Estimation of cutoff values by using regression lines method in Mishrif reservoir/Missan oil fields. J. Eng. 2019;25(2):82–95. doi: 10.31026/j.eng.2019.02.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdollahie-Fard I., Braathen A., Mokhtari M., Alavi S.A. Interaction of the Zagros fold–thrust belt and the arabian-type, deep-seated folds in the Abadan Plain and the dezful embayment, SW Iran. Petrol. Geol. 2006;12(4):347–362. doi: 10.1144/1354-079305-706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alavi M. Regional stratigraphy of the Zagros fold-thrust belt of Iran and its proforeland evolution. Am. J. Sci. 2004;304(1):1–20. doi: 10.2475/ajs.304.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Assadi A., Honarmand J., Moallemi S.A., Abdollahie-Fard I. Depositional environments and sequence stratigraphy of the Sarvak Formation in an oilfield in the Abadan Plain, SW Iran. Facies. 2016;62:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s10347-016-0477-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beiranvand B., Ahmadi A., Sharafodin M. Mapping and classifying flow units in the upper part of the mid‐cretaceous Sarvak formation (Western dezful embayment, sw Iran) based on a determination of reservoir rock types. J. Petrol. Geol. 2007;30(4):357–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-5457.2007.00357.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.James G.A., Wynd J.G. Stratigraphic nomenclature of Iranian oil consortium agreement area. Am. Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Bull. 1965;49(12):2182–2245. doi: 10.1306/A663388A-16C0-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masoudi P., Tokhmechi B., Bashari A., Jafari M.A. Identifying productive zones of the Sarvak formation by integrating outputs of different classification methods. J. Geophys. Eng. 2012;9(3):282–290. doi: 10.1088/1742-2132/9/3/282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dickson J.A.D. A modified staining technique for carbonates in thin section. Nature. 1965;205(4971):587. doi: 10.1038/205587a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawson I.D., Balogun A.O. Reservoir characterization using petrophysical evaluation of W-field, onshore Niger delta. Asian J. Chem. Sci. 2023;11(2):9–23. doi: 10.9734/ajopacs/2023/v11i2197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thota S.T., Islam M.A., Shalaby M.R. Reservoir quality evaluation using sedimentological and petrophysical characterization of deep-water turbidites: a case study of Tariki Sandstone Member, Taranaki Basin, New Zealand. Energy Geoscience. 2023;4(1):13–32. doi: 10.1016/j.engeos.2022.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Azadivash A., Shaabani M., Mehdipour V. Determining hydraulic flow units by using the flow zone indicator method and comparing them with electrofacies and microscopic sections in Sarvak formation in one of the fields of Abadan plain. Adv. Appl. Geol. 2021;11(3):473–492. doi: 10.22055/aag.2020.34529.2147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdolahi A., Chehrazi A., Kadkhodaie A., Babasafari A.A. Seismic inversion as a reliable technique to anticipating of porosity and facies delineation, a case study on Asmari formation in Hendijan field, southwest part of Iran. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2022;12(11):3091–3104. doi: 10.1007/s13202-022-01497-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matinkia M., Hashami R., Mehrad M., Hajsaeedi M.R., Velayati A. Prediction of permeability from well logs using a new hybrid machine learning algorithm. Petroleum. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.petlm.2022.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohaghegh S. Virtual-intelligence applications in petroleum engineering: part 1—artificial neural networks. J. Petrol. Technol. 2000;52(9):64–73. doi: 10.2118/58046-JPT. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohagheghian E., Zafarian-Rigaki H., Motamedi-Ghahfarrokhi Y., Hemmati-Sarapardeh A. Using an artificial neural network to predict carbon dioxide compressibility factor at high pressure and temperature. Kor. J. Chem. Eng. 2015;32:2087–2096. doi: 10.1007/s11814-015-0025-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poupon A., Leveaux J.A.C.Q.U. SPWLA 12th Annual Logging Symposium. OnePetro; 1971. Evaluation of water saturation in shaly formations. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elkhateeb A., Rezaee R., Kadkhodaie A. A new integrated approach to resolve the saturation profile using high-resolution facies in heterogenous reservoirs. Petroleum. 2022;8(3):318–331. doi: 10.1016/j.petlm.2021.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shedid S.A., Saad M.A. Comparison and sensitivity analysis of water saturation models in shaly sandstone reservoirs using well logging data. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017;156:536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2017.06.005. Doveton, J.H., 2014. Principles of Mathematical Petrophysics. Oxford University Press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amiri M., Yunan M.H., Zahedi G., Jaafar M.Z., Oyinloye E.O. Introducing new method to improve log derived saturation estimation in tight shaly sandstones—a case study from Mesaverde tight gas reservoir. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012;92:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2012.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith P.J., Buckee J.W. SPE Hydrocarbon Economics and Evaluation Symposium. OnePetro; 1985. Calculating in-place and recoverable hydrocarbons: a comparison of alternative methods. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dunham R.J. 1962. Classification of Carbonate Rocks According to Depositional Textures. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.