Abstract

Objective

Rapid eye movement (REM) obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by apnea and hypopnea events due to airway collapse occurring predominantly or exclusively during REM sleep. OSA is a potential risk factor for metabolic dysfunction. However, the association between REM OSA and risk of adverse health outcomes remains unclear. The present study investigated the association between REM OSA and metabolic syndrome (MetS), including the MetS components of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, in the Japanese population.

Methods

In total, 836 Japanese patients with mild to moderate OSA were enrolled in this study. We compared the prevalence of MetS, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, between REM OSA and non-REM OSA via univariate analyses of descriptive statistics and logistic regression analyses.

Results

The prevalence of hypertension was 68.3% in the REM OSA group and 56.6% in the non-REM OSA group (p<0.05). In addition, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was significantly higher (37.0%) in the REM OSA group than in the non-REM-OSA group (25.2%). Logistic regression analyses showed that the prevalence of hypertension and MetS was significantly greater in the REM OSA group than in the non-REM-OSA group.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that patients with REM OSA, regardless of age, sex, and body mass index, are at a higher risk of developing hypertension and MetS than patients with non-REM OSA.

Keywords: rapid eye movement obstructive sleep apnea, metabolic syndrome, hypertension

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disorder characterized by repetitive apnea and hypopnea due to complete or partial collapse of the upper airway during sleep despite ongoing breathing effort, resulting in oxygen desaturation, increased arousal from sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness (1). The prevalence of OSA is high, afflicting approximately 2-4% of the adult population (2). Furthermore, a recent review estimated that OSA affects approximately 5% of adults (3). OSA is strongly associated with cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, heart failure, and stroke, as well as with cardiovascular disease-associated mortality (4-7). In addition, several studies have reported that OSA is a potential risk factor for metabolic dysfunction, including obesity and diabetes (8-10).

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which typically accounts for 20-25% of total sleep time, is associated with distinct physiological alterations that influence upper airway function. In addition, OSA events during REM sleep are typically longer, more frequent, and are associated with greater oxyhemoglobin desaturation than OSA events occurring during non-REM sleep (11-13). Of note, REM sleep is associated with marked hemodynamic variability as well as increased sympathetic activity and myocardial demand compared with other sleep phases (4-6).

REM sleep deprivation can raise blood pressure in animals (14). However, there is currently limited data as to whether OSA occurring predominantly during REM sleep is associated with health outcomes. REM OSA is characterized by apnea and hypopnea events due to airway collapse occurring predominantly or exclusively during REM sleep (15). Previous studies have reported that REM OSA is more common in younger individuals and women than in others (16,17), and the prevalence of REM OSA varies widely, accounting for 11.1% to 36.7% of all OSA cases, due to inconsistent definitions of REM OSA (16,18-22). However, Mano et al. reported that REM OSA is more prevalent in women than men, regardless of age, and a postmenopausal status has been shown to influence associations with REM OSA in the Japanese population (18).

Therefore, REM OSA in the Japanese population is considered to have different characteristics from that occurring in non-Asians. Previous studies have reported that OSA during REM sleep is both cross-sectionally and longitudinally associated with hypertension. However, there are few reports on the association between metabolic syndrome, including its components of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, and REM OSA in a Japanese population.

The present study therefore investigated the association between REM OSA in the Japanese population and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

This study is in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of Aichi Medical University Hospital, and the Ethical Committee of Aichi Medical University Hospital approved the study protocol before the collection and analysis of the patient data (permission: 5/2019, approval number: 19-H038). Written informed consent was not obtained due to the retrospective nature of this study. Therefore, we disclosed the protocol of the study on the website, and subjects were offered the opportunity to opt out of the study.

Patients

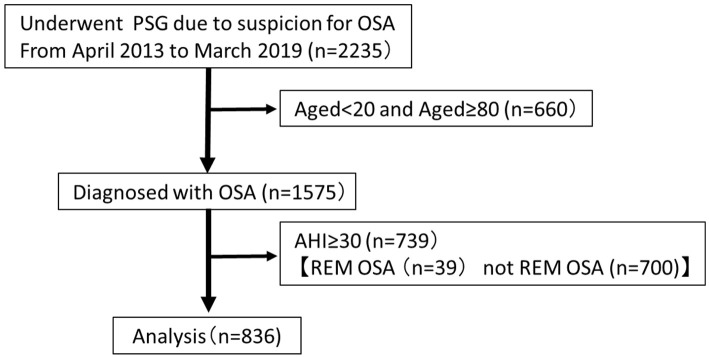

We assessed the medical records of patients who were primarily diagnosed with OSA using nocturnal polysomnography (PSG) from May 2013 to March 2019. None of the patients had undergone surgical procedures, had been treated using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, or were using an oral appliance. Patients <20 or >80 years old were excluded from this study. Patients with severe OSA with an apnea hypopnea index (AHI) ≥30/h were excluded, as REM OSA is widely distributed from mild to moderate (21). Finally, 836 patients were enrolled in this study. The study enrollment process is depicted in Figure.

Figure.

Flowchart of the study enrollment process for patients who underwent polysomnography (n=2,235). REM OSA, AHI ≥5; REM-AHI/NREM-AHI ≥2; NREM-AHI<15. AHI: apnea-hypopnea index, REM: rapid eye movement, OSA: obstructive sleep apnea, PSG: polysomnography

At the first visit, all patients were administered three questionnaires: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) questionnaires. Before the start of PSG, we measured the height, weight, body mass index (BMI), neck circumference, abdominal circumference at the level of the umbilicus, and buttock circumference.

Polysomnography

Nocturnal PSG was performed using the Alice 5 or 6 System (Respironics, Murrysville, USA), and PSG-1100 (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan). The following examinations were performed to continuously monitor biological variables: electroencephalography, bilateral electro-oculography, chin and anterior tibial electromyography, electrocardiography, airflow measurement using a nasal thermistor, measurement of respiratory effort based on thoracic and abdominal movements, body position, snoring sound, and arterial oxygen saturation. Apnea, hypopnea, and other PSG parameters were scored manually by sleep technicians according to the Rechtshaffen and Kales criteria (23). Apnea was defined as the cessation of air flow for at least 10 s. Hypopnea was defined as a 50% reduction in air flow and/or respiratory effort accompanied by oxygen desaturation of more than 3% or arousal. The AHI was defined as the average number of apnea and hypopnea events per hour of sleep, and OSA was defined in cases with an AHI ≥5. The AHI was divided into the AHI during REM sleep (REM-AHI) and during non-REM sleep (NREM-AHI), and REM OSA was defined in cases with a total AHI ≥5, REM-AHI/NREM-AHI >2, and NREM-AHI <15, which is the most commonly used definition (16,18).

Blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured between 2 and 4 PM with the subject in the supine position after a 5-min rest.

Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or any patient receiving antihypertensive treatment.

Laboratory test

In the early morning, after undergoing PSG, all patients underwent general blood sampling for the assessment of dyslipidemia and diabetes. Dyslipidemia was defined as low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol ≥140 mg/dL and/or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) <40 mg/dL or the use of medications for dyslipidemia, while diabetes was defined as hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥6.5% or the use of medications for diabetes.

Diagnosis of metabolic syndrome (MetS)

MetS was determined according to the Japanese Committee of the Criteria for MetS (JCCMS). In brief, MetS was defined in men and women with a waist circumference of ≥85 cm and ≥90 cm, respectively, and ≥2 of the following risk factors: triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL or HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL; systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg; fasting plasma glucose ≥110 mg/dL. Patients who had previously been diagnosed with dyslipidemia, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus and were receiving medications for any of these conditions were also included in the relevant category (24).

Statistical analyses

Comparisons between REM OSA and non-REM OSA in terms of baseline characteristics and PSG parameters were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test. Fisher's exact test was conducted for categorical variables. Logistic regression analyses were used to estimate the association between REM OSA and hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and MetS, after adjusting for the age, BMI, sex, AHI, and REM-AHI. The covariates were selected based on their established clinical relationships with difference between REM OSA and non-REM OSA. Odds ratios (ORs) are presented, along with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All comparisons were two-tailed, and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All data were analyzed using the SAS software program (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the comparison between the clinical characteristics in patients with REM OSA and in patients with non-REM OSA. The prevalence of women with REM OSA was significantly higher (38.8%) than that of women with non-REM OSA (20.9%). In addition, the REM OSA group had a higher BMI than the non-REM OSA group (26.2±13.4 vs. 24.4±7.6, p<0.001). Furthermore, the average PSQI score was significantly higher in the REM OSA group than in the non-REM OSA group (8.5±4.2 vs. 7.3±4.0, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Enrolled REM and Non-REM OSA Patients.

| Mild-moderate OSA (n=836) |

REM OSA (n=338) |

Non-REM OSA (n=498) |

p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (%) | 28.1 | 38.8 | 20.9 | <0.001* | ||||

| Age (years) | 57.6±14.0 | 57.2±13.2 | 57.9±14.3 | <0.001* | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.1±10.3 | 26.2±13.4 | 24.4±7.6 | <0.001* | ||||

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 88.5±11.4 | 90.2±12.5 | 87.4±10.6 | <0.001* | ||||

| Neck circumference (cm) | 37.1±5.5 | 36.9±5.9 | 37.2±5.2 | 0.29 | ||||

| ESS | 8.3±4.8 | 8.0±4.6 | 8.5±5.0 | 0.38 | ||||

| PSQI | 7.8±4.2 | 8.5±4.2 | 7.3±4.0 | <0.001* | ||||

| SDS | 40.0±9.6 | 39.5±9.5 | 40.7±9.7 | 0.14 |

Continuous variables are expressed as means±standard deviations, and categorical variables are expressed as numbers (proportions).

*p<0.05. BMI: body mass index, ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale, OSA: obstructive sleep apnea, PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, REM: rapid eye movement, SDS: Self-rating Depression Scale

Table 2 shows the detailed PSG findings compared between REM OSA and non-REM OSA groups. With regard to the evaluated PSG parameters, we found significant differences between REM OSA and non-REM OSA in the AHI (14.7±6.5 vs. 16.5±7.2, p<0.001), NREM-AHI (10.5±5.8 vs. 16.8±7.3, p<0.001), REM-AHI (36.7±15.0 vs. 14.8±11.3, p<0.001), AHI in the supine position (SUP-AHI) (20.3±14.5 vs.28.2±16.8, p<0.001), SpO2 low (83.6±6.7 vs. 86.7±5.6, p<0.001), and mean respiratory event duration (24.3±6.3 vs. 25.3±6.1, p=0.005).

Table 2.

Polysomnographic Parameters for REM and Non-REM OSA Patients.

| Mild-moderate OSA (n=836) |

REM OSA (n=338) |

Non-REM OSA (n=498) |

p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST (min) | 375.1±72.6 | 380.0±72.4 | 369±72.1 | 0.002* | ||||

| REM sleep time/TST (%) | 16.9±6.6 | 16.8±6.3 | 17.1±6.8 | 0.50 | ||||

| Stage 1 sleep time/TST (%) | 36.2±18.1 | 31.3±16.6 | 35.9±18.0 | <0.001* | ||||

| Stage 2 sleep time/TST (%) | 45.5±16.9 | 50.6±16.1 | 42.1±16.6 | <0.001* | ||||

| Stage 3+4 sleep time/TST (%) | 1.3±3.2 | 1.4±3.5 | 1.3±2.9 | 0.25 | ||||

| Sleep latency (min) | 13.3±21.9 | 12.8±20.1 | 13.8±24.3 | 0.44 | ||||

| REM latency (min) | 127.0±78.4 | 123.1±73.8 | 129.7±81.5 | 0.13 | ||||

| AHI (events/h) | 15.7±7.0 | 14.7±6.5 | 16.5±7.2 | <0.001* | ||||

| NREM-AHI (events/h) | 14.3±7.4 | 10.5±5.8 | 16.8±7.3 | <0.001* | ||||

| REM-AHI (events/h) | 23.8±16.8 | 36.7±15.0 | 14.8±11.3 | <0.001* | ||||

| REM-AHI/NREM-AHI (events/h) | 2.4±2.9 | 4.6±3.5 | 0.9±0.6 | <0.001* | ||||

| SUP-AHI (events/h) | 25.0±16.3 | 20.3±14.5 | 28.2±16.8 | <0.001* | ||||

| NSUP-AHI (events/h) | 6.6±6.9 | 7.3±8.3 | 6.1±5.7 | 0.64 | ||||

| AI (events/h) | 4.2±4.5 | 4.0±4.1 | 4.3±4.8 | 0.42 | ||||

| HI (events/h) | 11.5±5.8 | 10.6±5.6 | 12.2±5.9 | <0.001* | ||||

| SpO2 mean (%) | 96.2±1.5 | 96.0±1.6 | 96.5±1.4 | 0.002* | ||||

| SpO2 lowest value (%) | 85.4±6.3 | 83.6±6.7 | 86.7±5.6 | <0.001* | ||||

| Mean respiratory event duration (s) | 24.9±6.2 | 24.3±6.3 | 25.3±6.1 | 0.005* | ||||

| 3% ODI (events/h) | 12.2±7.8 | 12.4±8.2 | 12.1±7.6 | 0.78 | ||||

| Arousal index (events/h) | 22.4±10.7 | 22.7±10.8 | 22.3±6.1 | 0.063 | ||||

| Periodic limb movement index (events/h) | 12.2±23.1 | 11.3±22.8 | 12.8±23.3 | 0.097 |

Continuous variables are expressed as means±standard deviations, and categorical variables are expressed as numbers (proportions).

*p<0.05. AHI: apnea and hypopnea index, NREM: non-rapid eye movement, NREM-AHI: AHI during NREM sleep, OSA: obstructive sleep apnea, REM: rapid eye movement, REM-AHI: AHI during REM sleep, SUP-AHI: AHI in supine positions, NSUP-AHI: AHI in non-supine positions, SpO2: peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, TST: total sleep time

Table 3 shows the prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and metabolic syndrome in patients with OSA. The prevalence of hypertension in REM OSA and non-REM OSA was 68.3% and 56.6%, respectively, showing a significant difference. In addition, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was significantly higher in the REM OSA group (37.0%) than in the non-REM OSA group (25.2%).

Table 3.

Prevalence of Hypertension, Dyslipidemia, Hyperglycemia, Metabolic Syndrome in OSA Patients.

| Mild-moderate OSA (n=836) |

REM OSA (n=338) |

Non-REM OSA (n=498) |

p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 61.36 | 68.34 | 56.60 | <0.001* | ||||

| Dyslipidemia | 45.93 | 47.93 | 44.40 | 0.36 | ||||

| Hyperglycemia | 16.03 | 18.05 | 14.60 | 0.21 | ||||

| Metabolic syndrome | 30.02 | 36.98 | 25.20 | <0.001* |

* p<0.05. REM: rapid eye movement, OSA: obstructive sleep apnea

Table 4 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis for the association between REM OSA and hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and metabolic syndrome. The presence of REM OSA was significantly associated with an increased prevalence of hypertension in the unadjusted model (OR=1.640, 95% CI=1.227-2.191, p<0.001), in the model adjusted for age and sex (Model 1) (OR=1.871, 95% CI=1.370-2.555, p<0.001), in the model adjusted for the variables in Model 1 and the BMI (Model 2) (OR=1.588, 95% CI=1.140-2.211, p=0.0062), in the model adjusted for the variables in Model 2 and the AHI (Model 3) (OR=1.859, 95% CI=1.343-2.575, p<0.001), and in the model adjusted for the variables in Model 3 and the REM-AHI (Model 4) (OR=1.839, 95% CI=1.109-3.049, p=0.018). No significant differences existed between the REM OSA and non-REM OSA groups in the prevalence of dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia. The presence of REM OSA was significantly associated with an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the unadjusted model (OR=1.733, 95% CI=1.284-2.337, p<0.001), in Model 1 (adjusted for age and sex; OR=2.073, 95% CI=1.515-2.838, p<0.001), in Model 2 (adjusted for the variables in Model 1 and the BMI; OR=1.705, 95% CI=1.204-2.414, p=0.0027), in Model 3 (adjusted for the variables in Model 2 and the AHI; OR=2.130, 95% CI=1.528-2.970, p<0.001), and Model 4 (adjusted for the variables in Model 3 and the REM-AHI; OR=1.973, 95% CI=1.173-3.319, p=0.018).

Table 4.

Association of REM OSA with Hypertension, Dyslipidemia, Hyperglycemia and Metabolic Syndrome.

| REM OSA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | ||||||

| Hypertension | Unadjusted | 1.640 | 1.227-2.191 | <0.001* | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.871 | 1.370-2.555 | <0.001* | |||||

| Model 2 | 1.588 | 1.140-2.211 | 0.0062* | |||||

| Model 3 | 1.859 | 1.343-2.575 | <0.001* | |||||

| Model 4 | 1.839 | 1.109-3.049 | 0.018* | |||||

| Dyslipidemia | Unadjusted | 1.144 | 0.867-1.510 | 0.34 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.159 | 0.873-1.539 | 0.31 | |||||

| Model 2 | 1.027 | 0.766-1.378 | 0.86 | |||||

| Model 3 | 1.182 | 0.833-1.582 | 0.26 | |||||

| Model 4 | 1.044 | 0.658-1.655 | 0.85 | |||||

| Hyperglycemia | Unadjusted | 1.282 | 0.884-1.860 | 0.19 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.349 | 0.918-1.982 | 0.13 | |||||

| Model 2 | 1.137 | 0.763-1.694 | 0.53 | |||||

| Model 3 | 1.390 | 0.941-2.055 | 0.098 | |||||

| Model 4 | 1.576 | 0.084-2.959 | 0.157 | |||||

| Metabolic syndrome | Unadjusted | 1.733 | 1.284-2.337 | <0.001* | ||||

| Model 1 | 2.073 | 1.515-2.838 | <0.001* | |||||

| Model 2 | 1.705 | 1.204-2.414 | 0.0027* | |||||

| Model 3 | 2.130 | 1.528-2.970 | <0.001* | |||||

| Model 4 | 1.973 | 1.173-3.319 | 0.01* | |||||

Model 1: adjusted for age and sex. Model 2: adjusted for the parameters in Model 1+BMI. Model 3: adjusted for the parameters in Model 2+AHI. Model 4: adjusted for the parameters in Model 3+REM-AHI.

BMI: body mass index, CI: confidence interval, OR: odds ratio, REM: rapid eye movement, OSA: obstructive sleep apnea. AHI: apnea hypopnea index. *p<0.05.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between REM OSA and metabolic syndrome, including with regard to the MetS components of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, in mild to moderate OSA patients within a large-scale Japanese population. Our study was highly powered and rigorous. Our findings indicate that REM OSA may present with different clinical characteristics in Asian and non-Asian populations (19,25,26).

In this study, we confirmed that patients with REM OSA tended to have mild to moderate OSA (Figure), and REM OSA accounted for over 40% of mild to moderate OSA cases in the Japanese population. In addition, we found that the REM OSA group had a higher proportion of women than the non-REM OSA group in our study (38.8% vs. 20.9%, p<0.001). The ESS showed no marked difference between the REM OSA and non-REM OSA groups (8.0±4.6 vs. 8.5±5.0, p=0.38). However, the PSQI was significantly higher in the REM OSA group than in the non-REM OSA group (8.5±4.2 vs. 7.3±4.0, p<0.001). Furthermore, the BMI was higher in the REM OSA group than in the non-REM OSA group.

Our results were similar to those of previous reports indicating that REM OSA is more common in patients with mild to moderate OSA, as well as in women, younger patients, those with a high BMI (15), and patients with insomnia rather than drowsiness (27). In addition, a recent study reported that REM OSA is a relatively stable condition and does not progress in the majority of individuals (28). Therefore, it is important to recognize the associations between REM OSA and its adverse health effects compared with those seen in non-REM OSA.

MetS is common in patients with OSA because obesity is a common risk factor for this condition. Previous studies have clearly indicated that OSA and metabolic syndrome frequently accompany each other (29), thus further aggravating the risk of cardiovascular disease due to sclerosis of the arterial walls as well as vasculitis. However, whether or not the risks associated with these adverse outcomes depend on the stage of sleep in which apnea events occur is unclear.

A reduced adherence to CPAP therapy has been reported in patients with REM OSA (30). REM sleep accounts for about 20-25% of total sleep in adults and is typically concentrated in the second half of sleep time, with the longest REM period occurring at the end of the night's sleep. REM sleep is more strongly associated with marked fluctuations in sympathetic balance and cardiovascular instability than non-REM sleep. Therefore, it is very important to consider the significance of treatment for REM OSA, which is relatively mild.

Previous studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between the AHI during REM sleep and the prevalence of hypertension (31). However, the association between REM OSA, which concentrates on respiratory events occurring during REM sleep, and MetS, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, has not been clearly shown.

Therefore, in the present logistic regression analysis, we selected the age, sex, BMI, AHI and REM-AHI as the model covariates, as these characteristics have established differential clinical relationships with REM OSA and non-REM OSA in Japanese patients with mild to moderate OSA. After adjusting for these covariates, compared to non-REM OSA, multivariable ORs of hypertension ranged from 1.588 to 1.871 for REM OSA. In a previous study, there was an increased risk of upper airway collapse, elevated sympathetic activity, and an increased tendency toward a blood pressure increase during REM sleep compared with non-REM sleep, and a 2-fold increase in the REM-AHI was associated with a 24% higher odds of prevalent hypertension (31). Therefore, we confirmed that REM OSA is a more important risk factor for hypertension than non-REM OSA.

The rates of dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia in REM OSA were also not significantly different from those in non-REM OSA in this study. Our results are similar to those of a previous study, which found that patients with REM OSA had lower HbA1c levels than patients with non-REM OSA (5.5±0.9 vs. 5.9±2.6; p=0.018) (19).

Finally, compared to non-REM OSA, the multivariable odds rate of MetS ranged from 1.705 to 2.130 for REM OSA. The prevalence of MetS in patients with REM OSA significantly differed from its prevalence in patients with non-REM OSA, after adjusting for the age, sex, BMI, AHI and REM-AHI. In a previous study, nocturnal intermittent hypoxia was associated with the accumulation of metabolic risk factors. In addition, women with nocturnal intermittent hypoxia were at a higher risk of MetS than healthy women, and this finding was more prominent than in men (32). Furthermore, in sleep apnea patients, the duration of apnea was shown to be longer and hypoxemia more severe during REM sleep than during non-REM sleep (33). In the present study, the mean respiratory event duration in the total sleep time was shorter in the REM OSA group than in the non-REM OSA group, but the lowest SpO2 value was lower in the REM OSA group than in the non-REM OSA group. Therefore, REM OSA may cause more severe hypoxemia than non-REM OSA.

REM OSA, which is female-dominated compared to non-REM OSA and concentrates on respiratory events occurring during REM sleep, is considered to increase the risk of MetS. In the present study, we clarified that patients with REM OSA, regardless of their age, sex, BMI, AHI, and REM-AHI, are at a higher risk of hypertension and MetS than patients with non-REM OSA.

Limitations

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. First, a selection bias may have been introduced by the fact that this study was conducted in a single setting in Japan. Second, this study did not include patients with suspected asymptomatic OSA because of observational studies, and bias may exist in the population. Third, the effects of unknown confounding factors, including the use of medication affecting REM sleep could not be excluded because of the retrospective nature of this study. Further prospective observational studies are therefore necessary to clarify this point.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this study is the first report of indicating the association between REM OSA and metabolic syndrome, including MetS components of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, within a large sample of Japanese OSA patients. REM OSA is relatively mild to moderate OSA. In cases of mild to moderate OSA, we found that the prevalence of both metabolic syndrome and hypertension was significantly greater in REM OSA than in non-REM OSA patients. No significant differences were noted between the two groups in the proportion of patients with dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia. Our findings will hopefully guide future research directions and directly inform medical guidelines with regard to screening and preventive medicine efforts.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the patients with OSA who participated in this study and the sleep technicians who manually scored the PSG data, including Momona Arii, Takehiro Yamaguchi, Chihiro Kato, Aki Arita, and Masato Imai.

References

- 1. Franklin KA, Lindberg E. Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population - a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis 7: 1311-1322, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med 328: 1230-1235, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 1217-1239, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol 52: 686-717, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li L, Kayukawa Y, Imai M, Okada T, Ando A, Ohta T. Association of sleep-disorder breathing with hypertension in Japanese industrial workers. Sleep Biol Rhythm 1: 221-227, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campos-Rodriguez F, Martinez-Garcia MA, Reyes-Nuñez N, Caballero-Martinez I, Catalan-Serra P, Almeida-Gonzalez CV. Role of sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure therapy in the incidence of stroke or coronary heart disease in women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189: 1544-1550, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marshall NS, Wong KK, Cullen SR, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Sleep apnea and 20-year follow-up for all-cause mortality, stroke, and cancer incidence and mortality in the Busselton Health Study Cohort. J Clin Sleep Med 10: 355-362, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Otake K, Sasanabe R, Hasegawa R, et al. Glucose intolerance in Japanese patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Intern Med 48: 1863-1868, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mesarwi OA, Sharma EV, Jun JC, Polotsky VY. Metabolic dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea: a critical examination of underlying mechanisms. Sleep Biol Rhythm 13: 2-17, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jehan S, Myers AK, Zizi F, Pandi-Perumal SR, Jean-Louis G, McFarlane SI. Obesity, obstructive sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes mellitus: epidemiology and pathophysiologic insights. Sleep Med Disord 2: 52-58, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Penzel T, Kantelhardt JW, Bartsch RP, Riedl M, Kraemer JF, Wessel N, et al. Modulations of heart rate, ECG, and cardio-respiratory coupling observed in polysomnography. Front Physiol 7: 460, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Somers VK, Dyken ME, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Sympathetic-nerve activity during sleep in normal subjects. N Engl J Med 328: 303-307, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Somers VK, Dyken ME, Clary MP, Abboud FM. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest 96: 1897-1904, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiang J, Gan Z, Li Y. REM sleep deprivation induces endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in middle-aged rats. PLoS One 15: 12, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mokhlesi B, Punjabi NM. “REM-related” obstructive sleep apnea: an epiphenomenon or a clinically important entity? Sleep 35: 5-7, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Conwell W, Patel B, Doeing D, et al. Prevalence, clinical features, and CPAP adherence in REM-related sleep-disordered breathing: a cross-sectional analysis of a large clinical population. Sleep Breath 17: 519-526, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haba-Rubio J, Janssens JP, Rochat T, Sforza E. Rapid eye movement related disordered breathing: clinical and polysomnographic features. Chest 128: 3350-3357, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mano M, Hosino T, Sasanabe R, et al. Impact of gender and age on rapid eye movement-related obstructive sleep apnea: a clinical study of 3234 Japanese OSA patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16: 1068, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sakao S, Sakurai T, Yahaba M, et al. Features of REM-related sleep disorder breathing in the Japanese population. Intern Med 54: 1481-1487, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koo BB, Dostal J, Ioachimescu O, Budur K. The effects of gender and age on REM-related sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath 12: 259-264, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pamidi S, Knutson KL, Farbod G. Depressive symptom and obesity as predictors of sleepiness and quality of life in patients with REM-related obstructive sleep apnea: cross-sectional analysis of a large clinical population. Sleep Med 129: 827-831, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haba-Rubio J, Janssens JP, Rochat T, et al. Rapid eye movement-related disordered breathing: clinical and polysomnographic features. Chest 128: 3350-3357, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rechtshaffen A, Kales A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. version2.5. UCLA Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Committee on the Evaluation of Diagnostic Standards for Metabolic Syndrome . Definition and diagnostic standards for metabolic syndrome. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi (J Jpn Soc Intern Med) 94: 794-809, 2005(in Japanese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sasai-Sakuma T, Kayaba M, Inoue Y, Nakayama H. Prevalence, clinical symptoms and polysomnographic findings of REM-related sleep disordered breathing in Japanese population. Sleep Med 80: 52-56, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koo DL, Kim HR, Nam H. Moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea during REM sleep as a predictor of metabolic syndrome in a Korean population. Sleep Breath 24: 1751-1758, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoshino T, Sasanabe R, Murotani K, et al. Insomnia as a symptom of rapid eye movement-related obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Med 9: 1821, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aurora RN, McGuffey EJ, Punjabi NM. Natural history of sleep-disordered breathing during rapid eye movement sleep. Relevance for incident cardiovascular disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 17: 614-620, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Parish JM, Adam T, Facchiano L. Relationship of metabolic syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 3: 467-472, 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hoshino T, Sasanabe R, Tanigawa T, et al. Effect of rapid eye movement-related obstructive sleep apnea on adherence to continuous positive airway pressure. J Int Med Res 46: 2238-2248, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Babak M, Laurel A Fi, Erika WH, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea during REM sleep and hypertension results of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190: 1158-1167, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Isao M, Takeshi T, Kazumasa Y, et al. ; the CIRCS Investigators . Nocturnal intermittent hypoxia and metabolic syndrome; the effect of being overweight: the CIRCS study. J Atheroscler Thromb 17: 369-377, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Findley LJ, Wilhoit SC, Suratt PM. Apnea duration and hypoxemia during REM sleep in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 87: 432-436, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]