Abstract

The high mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2, which has led to the emergence of a number of virus variants, creates risks of transmission from humans to animal species and the emergence of new animal reservoirs of COVID-19. This study aimed to identify animal species among livestock susceptible to infection and develop an approach that would be possible to use for assessing the hazards caused by new SARS-CoV-2 variants for animals. Bioinformatic analysis was used to evaluate the ability of receptor-binding domains (RBDs) of different SARS-CoV-2 variants to interact with ACE2 receptors of livestock species. The results indicated that the stability of RBD-ACE2 complexes depends on both amino acid residues in the ACE2 sequences of animal species and on mutations in the RBDs of SARS-CoV-2 variants, with the residues in the interface of the RBD-ACE2 complex being the most important. All studied SARS-CoV-2 variants had high affinity for ferret and American mink receptors, while the affinity for horse, donkey, and bird species’ receptors significantly increased in the highly mutated Omicron variant. Hazards that future SARS-CoV-2 variants may acquire specificity to new animal species remain high given the mutability of the virus. The continued use and expansion of the bioinformatic approach presented in this study may be relevant for monitoring transmission risks and preventing the emergence of new reservoirs of COVID-19 among animals.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Bioinformatic analysis, Receptor binding, Mutation, Binding free energy

1. Introduction

Due to the frequent interactions between humans and various animal species, particularly livestock, animals serve as carriers of pathogens of human diseases and act as sources of zoonotic infections, which have repeatedly become the causes of epidemics (Rahman et al., 2020; Weiss & Sankaran, 2022). At the end of 2019, a previously unknown severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged, which caused the COVID-19 pandemic (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020) and significant negative consequences (Saladino et al., 2020; Pak et al., 2020). The scientific community has repeatedly raised questions regarding the potential role of animals as the primary source of SARS-CoV-2 origin and its transmission to humans (Mahdy et al., 2020; Lytras et al., 2021). Furthermore, concerns exist regarding the transmission of the virus from humans to animal species, potentially establishing new natural reservoirs and facilitating further spread in the environment (Valencak et al., 2021; WHO, 2022).

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the Coronaviridae family, which includes viruses causing respiratory, intestinal, and neurological diseases in animals, including birds and mammals (Synowiec et al., 2021; Decaro & Lorusso, 2020). Phylogenetic analysis indicates that SARS-CoV-2 is very close to bat coronaviruses detected in China (Bat-SL-CoVZC45, Bat-SL-CoVZXC21, and Bat-CoV RaTG13), as well as some human coronaviruses (SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV). The last two viruses have already been the cause of epidemics of human respiratory diseases before (Lv et al., 2020), although have been originated from animals: SARS-CoV probably occurred from bats and transmitted to humans via civets (Wang & Eaton, 2007), while the reservoir of MERS-CoV were dromedaries (Goldstein & Weiss, 2017). Consequently, this makes the task of investigating animals as a possible reservoir of COVID-19 and trying to answer the question of whether SARS-CoV-2 is of animal or artificial origin Holmes et al. (2021).

SARS-CoV-2 uses a trimeric spike glycoprotein (S-protein) to penetrate the host cell. Each S-protein consists of two subunits (S1 and S2), preceded by a short signal peptide (Xia et al., 2020). The S1 subunit includes the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and is responsible for binding to the receptor on the surface of the host cell, and the S2 subunit facilitates the fusion between the virus membrane and the cytoplasmic membrane of the host cell (Huang et al., 2020). It has been experimentally confirmed that both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV use angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a receptor for cellular entry (Wang et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020), which under physiological conditions is as part of the renin-angiotensin system. ACE2 is a type I transmembrane protein consisting of an extracellular N-glycosylated N-terminal domain containing a carboxypeptidase site and a short intracellular C-terminal cytoplasmic tail (Xiao et al., 2020). Crystallographic analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 S-protein complex with human ACE2 demonstrates the involvement of the N-terminal peptidase domain in the interaction with the virus (Lan et al., 2020).

The stability of the RBD-ACE2 complex formed during the interaction of the virus with the cell, which is ensured by chemical bonds between the amino acid residues of the S-protein RBD and ACE2 N-terminal peptidase domain, is of great importance for the penetration of SARS-CoV-2 into the cell (Borkotoky et al., 2023). Interface amino acid residues of ACE2 thus play the role of “hot spots” (Lim et al., 2020), and their variability in the corresponding positions of animal ACE2 sequences may be decisive for whether SARS-CoV-2 can interact with the ACE2 receptor and infect animal cells.

A number of experimental studies in vitro and using model animals were conducted to investigate potential interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and various animal species at the level of the ACE2 receptor, the penetration of the virus into the cell, and the development of the infectious process with characteristic manifestations (Meekins et al., 2021). There is evidence that the virus can interact with ACE2 receptors and enter cells in different animal species (Zhou et al., 2020; Conceicao et al., 2020). Moreover, experimental infection attempts indicate the presence of both susceptible and resistant biological species to SARS-CoV-2 (Meekins et al., 2021). At the same time, SARS-CoV-2 has shown a significant ability to mutate, thus many virus variants have emerged (WHO, n.d.). Mutations accumulated in the SARS-CoV-2 have enhanced its infectious properties; in particular, mutations in the S-protein have increased its ACE2 affinity and ability to infect human cells (Gobeil et al., 2021; Barton et al., 2021). Thus, the possibility of new variants with the potential to interact more effectively with animal cells cannot be excluded, even in species previously considered resistant to infection (Bashor et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2022; Saied & Metwally, 2022). Therefore, there is a need to monitor the properties of new SARS-CoV-2 variants and their potential for transmission to animals. These measures should prevent the emergence of animal reservoirs of COVID-19, as well as the further spread of the infection.

The aim of this study was to identify animal species susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 using bioinformatic methods. Additionally, the study aimed to develop an approach that would be possible to use for further assessment of transmission risks to animals of the new SARS-CoV-2 variants appearing because of the virus evolution.

2. Materials and methods

The ACE2 reference coding sequences (CDSs) and amino acid sequences (AASs) of human and livestock species (15 mammalian and 6 avian species) deposited in the NCBI database were used for analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

ACE2 reference coding sequences and amino acid sequences (NCBI database).

| Species | ACE2 coding sequences | ACE2 amino acid sequences |

|---|---|---|

| Human (Homo sapiens) |

NM_001371415.1 | NP_001358344.1 |

| Domestic pig (Sus scrofa domesticus) |

KX756982.1 | ASK12083.1 |

| Taurine cattle (Bos taurus) |

XM_005228429.4 | XP_005228486.1 |

| Zebu cattle (Bos indicus) |

XM_019956161.1 | XP_019811720.1 |

| Water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) |

XM_006041540.3 | XP_006041602.1 |

| Sheep (Ovis aries) |

XM_012106267.4 | XP_011961657.1 |

| Goat (Capra hircus) |

XM_005701072.3 | XP_005701129.2 |

| Dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius) |

XM_031445857.1 | XP_031301717.1 |

| Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) |

XM_010968001.2 | XP_010966303.1 |

| Llama (Lama glama) |

MW863647.1 | QWM88990.1 |

| Alpaca (Vicugna pacos) |

XM_006212647.3 | XP_006212709.1 |

| Horse (Equus caballus) |

XM_001490191.5 | XP_001490241.1 |

| Donkey (Equus asinus) |

XM_044764461.1 | XP_044620396.1 |

| European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) |

XM_002719845.4 | XP_002719891.1 |

| Ferret (Mustela putorius furo) |

NM_001310190.1 | NP_001297119.1 |

| American mink (Neovison vison) |

XM_044236017.1 | XP_044091952.1 |

| Chicken (Gallus gallus) |

XM_416822.7 | XP_416822.3 |

| Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) |

XM_013094461.4 | XP_012949915.3 |

| Helmeted guineafowl (Numida meleagris) |

XM_021385056.1 | XP_021240731.1 |

| Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) |

XM_015886577.2 | XP_015742063.1 |

| Common pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) |

XM_031596059.1 | XP_031451919.1 |

| South African ostrich (Struthio camelus australis) |

XM_009669200.1 | XP_009667495.1 |

For the human and livestock ACE2 AASs, the degree of the identity and the degree of the similarity were determined, and for CDSs, only the degree of the identity was determined. For evaluation, the pairwise alignments were performed between the human ACE2 AAS and CDS with the corresponding sequences of animals using the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm (Needleman & Wunsch, 1970) in EMBOSS Needle (Madeira et al., 2022). The BLOSUM62 substitution matrix (Henikoff & Henikoff, 1992) was used for alignments of AASs, and the EDNAFULL matrix was used for alignments of CDSs. In the case of the AAS alignments, the same amino acids in two sequences (no substitutions) were considered “identical”; amino acid pairs with a score > 0 according to the BLOSUM62 substitution matrix were considered “similar”.

Multiple alignment of CDSs was performed according to the ClustalW algorithm (Thompson et al., 1994) in the Mega11 software (Version 11 64-bit; Tamura et al., 2021) to determine the conservatism of ACE2 receptors across different animal species and to conduct phylogenetic analysis. The distance matrix was built using the Maximum Composite Likelihood model (Tamura et al., 2004); the phylogenetic tree was built using the Maximum Likelihood method and the JTT matrix-based model (Jones et al., 1992) in the Mega11 software.

Amino acid residues located in the interface of the RBD-ACE2 complex were considered “hot spots”. Grantham’s distances (Grantham, 1974; Li et al., 1984), which take into account such properties as composition, polarity, and molecular volume, were used to assess the similarity of each “hot spot” amino acid pair where the livestock species have substitutions compared to the human AAS (according to multiple sequence alignment).

The X-ray structure (PDB ID: 6LZG) of the novel coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with its ACE2 receptor (Wang et al., 2020) from the RCSB PDB was used as a reference to model the three-dimensional structures of the human and livestock RBD-ACE2 complexes. This reference structure of the human RBD-ACE2 complex was considered a complex of the human ACE2 with the RBD of wild-type (WT) SARS-CoV-2. The reference structure was prepared for further analysis: solvent was deleted, and H atoms were added. Then RBD mutations were added to obtain structures of human ACE2 complexed with RBDs of other SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron BA.1). All structures (both for WT virus and SARS-CoV-2 variants) were minimized in the GROMOS96 force field (Van Gunsteren et al., 1996). The steepest descent minimization was performed after each point mutation introduction in order to resolve possible clashes. After introducing all mutations, a two-stage minimization using the steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms was carried out. All procedures were performed using the Swiss-PdbViewer (Version 4.1; Guex & Peitsch, 1997).

Homology modeling on the Swiss-Model Server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org; Waterhouse et al., 2018) was performed using the reference PDB 6LZG structure as a template to obtain three-dimensional structures of the RBD-ACE2 complexes for human and livestock species. Based on phylogenetic clustering, those animal species were identified for which RBD-ACE2 complexes were modeled. Fragments of the human and livestock ACE2 sequences, as well as, S-protein sequences of several SARS-CoV-2 variants (WT virus, Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron BA.1) were used as input for modeling. These sequences were aligned with chain A and chain B sequences of the PDB 6LZG structure accordingly. Output livestock structures were also minimized in the GROMOS96 force field using the Swiss-PdbViewer to equilibrate them with the corresponding human RBD-ACE2 structures before energy calculations.

Thus, for comparison and reduction of errors associated with computer modeling, complexes of human ACE2 with SARS-CoV-2 variants were constructed using two different methods: 1) by point mutagenesis of the reference structure (introducing point RBD mutations into the structure of the original complex, which was intended to prevent relative displacements in the space of the parts of amino acid chains that were not subject to mutagenesis); 2) by homology modeling, similar to what was done for animal complexes. At the same time, only the homology modeling method was suitable for obtaining the structures of complexes with ACE2s of animal species due to the interspecies differences in ACE2 AASs.

Predictive tools that calculate changes in the binding free energy (ΔΔG) were used to evaluate the effect of “hot spot” amino acid substitutions in animal ACE2s on the RBD binding compared to human ACE2. For a comprehensive assessment, several tools with different algorithms were used at once: BeAtMuSiC is based on the use of a set of statistical potentials (http://babylone.ulb.ac.be/beatmusic; Dehouck et al., 2013); BindProfX takes into account statistical and physics-based potentials (https://zhanggroup.org/BindProfX; Xiong et al., 2017); mCSM-PPI2 is a machine-learning method which uses graph-based signatures integrated with other indicators of structure stability (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/mcsm_ppi2; Rodrigues et al., 2019); MutaBind2 is based on an accounting of changes in physicochemical features and evolutionary conservation (https://lilab.jysw.suda.edu.cn/research/mutabind2; Zhang et al., 2020); SAAMBE-3D is a machine-learning method based on features of the physical environment of the mutation site (http://compbio.clemson.edu/saambe_webserver; Pahari et al., 2020). As input data, the minimized structure of the human ACE2 complexed with the RBD of WT virus was used for predictions. The approach based on the calculation of the ΔΔG takes into account only the influence of individual amino acid substitutions, leaving other interspecies differences in AAS outside the estimate. As the effect of amino acid substitutions is more complex due to the interaction of amino acids with each other, the application of this approach has certain limitations. In this study, it was used as a primary evaluation to get an idea of whether specific interspecies substitutions contribute to enhanced interactions with the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 or not.

On the contrary, when calculating the total level of the binding free energy (ΔG) of human and livestock RDB-ACE2 complexes, the contribution of each amino acid to the formation of the chemical interactions was taken into account. The ΔG calculations were performed through molecular dynamics simulations using the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) method (Gohlke & Case, 2004) on the HawkDock server (http://cadd.zju.edu.cn/hawkdock; Weng et al., 2019). For calculating the ΔG, it was necessary to perform multiple simulations (Likic et al., 2005) for each model of RBD-ACE2 complexes to ensure accurate results. Subsequently, the ΔG values were examined for outliers using the interquartile range method, followed by calculating the average values and standard deviations.

Visualization of three-dimensional structures of the human and livestock RBD-ACE2 complexes and assessment of existing chemical bonds between ACE2 and RBD were performed using open-source PyMOL software (Version 2.0; Schrödinger, LLC, 2022).

3. Results

3.1. Comparative and phylogenetic analysis of ACE2 receptors

A comparative analysis was conducted to assess the similarities between ACE2 receptors in humans and different animal species. Table 2 presents the degrees of the identity for CDSs, degrees of the identity and similarity for AASs, and alignment scores for the respective pairwise alignments. The degrees of the identity of CDSs ranged from 85.1 to 89.4% for the studied mammalian species and from 66.5 to 68.1% for bird species; the degrees of the identity for AASs ranged from 80.9 to 87.0% for mammals and from 64.5 to 66.5% for birds; the degrees of the similarity for AASs ranged from 90.4 to 93.4% for mammals and from 78.6 to 79.4% for birds when compared to the corresponding human sequences. Notably, the degrees of the identity obtained for CDSs were consistently higher for all animals than the corresponding values of the degrees of the identity for AASs.

Table 2.

Comparison of livestock ACE2 coding and amino acid sequences with corresponding ones of human ACE2.

| Human sequence comparison to… | CDS alignment | AAS alignment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (bp) | Alignment score | Identity (%) | Length (aa) | Alignment score ↓ | Identity (%) | Similarity (%) | |

| Human | 2418 | 12,090.0 | 100.0 | 805 | 4291.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Donkey | 2418 | 9756.0 | 89.4 | 805 | 3795.0 | 87.0 | 93.4 |

| Horse | 2418 | 9738.0 | 89.3 | 805 | 3791.0 | 86.8 | 93.4 |

| European rabbit | 2418 | 9545.0 | 88.3 | 805 | 3722.0 | 85.2 | 92.8 |

| Dromedary camel | 2418 | 9225.0 | 86.9 | 805 | 3666.0 | 83.2 | 92.4 |

| Bactrian camel | 2418 | 9225.0 | 86.9 | 805 | 3666.0 | 83.2 | 92.4 |

| Alpaca | 2418 | 9259.0 | 87.1 | 805 | 3653.0 | 83.4 | 91.9 |

| Llama | 2418 | 9250.0 | 87.0 | 805 | 3652.0 | 83.4 | 91.9 |

| American mink | 2418 | 9056.0 | 86.1 | 805 | 3648.0 | 83.0 | 91.9 |

| Ferret | 2418 | 9022.0 | 85.9 | 805 | 3628.0 | 82.6 | 91.6 |

| Domestic pig | 2418 | 8802.0 | 85.0 | 805 | 3587.0 | 81.7 | 91.1 |

| Sheep | 2415 | 9010.0 | 85.8 | 804 | 3579.0 | 81.7 | 90.8 |

| Goat | 2415 | 8947.0 | 85.5 | 804 | 3572.0 | 81.6 | 90.6 |

| Taurine cattle | 2415 | 8873.0 | 85.1 | 804 | 3568.0 | 81.1 | 90.7 |

| Zebu cattle | 2415 | 8873.0 | 85.1 | 804 | 3563.0 | 81.1 | 90.4 |

| Water buffalo | 2412 | 8890.0 | 85.2 | 803 | 3555.0 | 80.9 | 90.6 |

| Japanese quail | 2424 | 5727.0 | 67.9 | 807 | 2926.5 | 66.5 | 79.4 |

| Common pheasant | 2427 | 5733.0 | 67.9 | 808 | 2920.5 | 65.7 | 79.3 |

| Chicken | 2427 | 5671.5 | 67.9 | 808 | 2919.5 | 65.4 | 79.3 |

| Helmeted guineafowl | 2433 | 5660.0 | 66.9 | 810 | 2888.5 | 64.8 | 78.8 |

| South African ostrich | 2427 | 5692.0 | 68.1 | 808 | 2860.0 | 64.5 | 79.1 |

| Mallard | 2418 | 5528.0 | 66.5 | 805 | 2847.0 | 64.7 | 78.6 |

Note: the down arrow (↓) indicates the column by which the sort was performed. CDS - coding sequence; AAS - amino acid sequence.

Phylogenetic analysis based on ACE2 was carried out to establish links not only between human and other animal species but also utilizing the “all with all” approach. A phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1) and a distance matrix (Table 3) were constructed based on the multiple alignment of CDSs. Among the studied species, the closest mammalian species to humans were donkeys, horses, and rabbits, while the most distant mammals were pigs and cattle species. When comparing animals within the same systematic groups of the zoological classification, as expected, closer phylogenetic relationships were also observed.

Fig 1.

Phylogenetic tree of human and livestock species built based on the alignment of ACE2 coding sequences. Phylogenetic tree was built using the Maximum Likelihood method and the JTT matrix-based model based on the results of multiple alignment of ACE2 coding sequences performed according to the ClustalW algorithm.

Table 3.

Distances between ACE2 coding sequences in humans and livestock species.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Human | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Donkey | 0.1163 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Horse | 0.1172 | 0.0021 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | European rabbit | 0.1268 | 0.1187 | 0.1188 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Dromedary camel | 0.1453 | 0.0902 | 0.0902 | 0.1349 | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Bactrian camel | 0.1453 | 0.0916 | 0.0916 | 0.1359 | 0.0012 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Alpaca | 0.1435 | 0.0949 | 0.0949 | 0.1375 | 0.0108 | 0.0104 | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | Lama | 0.1439 | 0.0958 | 0.0959 | 0.1380 | 0.0142 | 0.0138 | 0.0041 | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | American mink | 0.1545 | 0.1072 | 0.1077 | 0.1422 | 0.1242 | 0.1257 | 0.1272 | 0.1282 | |||||||||||||

| 10 | Ferret | 0.1565 | 0.1086 | 0.1091 | 0.1456 | 0.1252 | 0.1267 | 0.1287 | 0.1297 | 0.0108 | ||||||||||||

| 11 | Domestic pig | 0.1690 | 0.1179 | 0.1185 | 0.1518 | 0.1049 | 0.1064 | 0.1031 | 0.1055 | 0.1497 | 0.1506 | |||||||||||

| 12 | Sheep | 0.1563 | 0.1147 | 0.1147 | 0.1510 | 0.1008 | 0.1022 | 0.1028 | 0.1042 | 0.1516 | 0.1535 | 0.1178 | ||||||||||

| 13 | Goat | 0.1599 | 0.1146 | 0.1147 | 0.1495 | 0.1007 | 0.1022 | 0.1032 | 0.1046 | 0.1515 | 0.1535 | 0.1163 | 0.0054 | |||||||||

| 14 | Taurine cattle | 0.1639 | 0.1171 | 0.1171 | 0.1501 | 0.1027 | 0.1041 | 0.1070 | 0.1084 | 0.1496 | 0.1516 | 0.1197 | 0.0244 | 0.0235 | ||||||||

| 15 | Zebu cattle | 0.1639 | 0.1171 | 0.1171 | 0.1501 | 0.1027 | 0.1041 | 0.1061 | 0.1075 | 0.1517 | 0.1531 | 0.1188 | 0.0252 | 0.0244 | 0.0025 | |||||||

| 16 | Water buffalo | 0.1616 | 0.1196 | 0.1196 | 0.1512 | 0.1047 | 0.1061 | 0.1081 | 0.1105 | 0.1528 | 0.1547 | 0.1203 | 0.0248 | 0.0239 | 0.0117 | 0.0134 | ||||||

| 17 | Japanese quail | 0.4204 | 0.4199 | 0.4213 | 0.4232 | 0.4156 | 0.4161 | 0.4216 | 0.4229 | 0.4069 | 0.4077 | 0.4352 | 0.4266 | 0.4254 | 0.4252 | 0.4252 | 0.4213 | |||||

| 18 | Common pheasant | 0.4231 | 0.4221 | 0.4223 | 0.4266 | 0.4200 | 0.4205 | 0.4261 | 0.4287 | 0.4125 | 0.4140 | 0.4370 | 0.4279 | 0.4267 | 0.4280 | 0.4281 | 0.4222 | 0.0445 | ||||

| 19 | Chicken | 0.4279 | 0.4272 | 0.4287 | 0.4427 | 0.4258 | 0.4263 | 0.4333 | 0.4345 | 0.4168 | 0.4177 | 0.4410 | 0.4370 | 0.4372 | 0.4379 | 0.4379 | 0.4348 | 0.0510 | 0.0375 | |||

| 20 | Helmeted quineafowl | 0.4271 | 0.4281 | 0.4296 | 0.4385 | 0.4261 | 0.4267 | 0.4330 | 0.4343 | 0.4152 | 0.4167 | 0.4415 | 0.4359 | 0.4347 | 0.4323 | 0.4324 | 0.4292 | 0.0546 | 0.0444 | 0.0462 | ||

| 21 | South African ostrich | 0.4301 | 0.4240 | 0.4241 | 0.4307 | 0.4319 | 0.4325 | 0.4326 | 0.4355 | 0.4245 | 0.4224 | 0.4328 | 0.4358 | 0.4345 | 0.4336 | 0.4336 | 0.4333 | 0.1628 | 0.1655 | 0.1711 | 0.1634 | |

| 22 | Mallard | 0.4333 | 0.4260 | 0.4268 | 0.4314 | 0.4311 | 0.4303 | 0.4339 | 0.4382 | 0.4183 | 0.4169 | 0.4386 | 0.4385 | 0.4387 | 0.4406 | 0.4398 | 0.4381 | 0.1221 | 0.1190 | 0.1263 | 0.1170 | 0.1620 |

Note: a distance matrix was built using the Maximum Composite Likelihood model based on the results of multiple alignment of ACE2 coding sequences performed according to the ClustalW algorithm.

3.2. Assessment of the amino acid residue variability in ACE2 “hot spots”

The “hot spots” refer to amino acid residues involved in the formation of chemical bonds between the RBD and ACE2, which are crucial for the high affinity of the virus S-protein for ACE2. Table 4 illustrates that mammalian species have different numbers of substitutions in the “hot spots”. American mink and ferret have 7 substitutions in the “hot spots”, while donkey and horse have 6 substitutions, including one moderately radical Q24L substitution in each of these species. Alpaca, llama, and pig have 5 substitutions each, with llama and alpaca having two moderately radical substitutions (Q24L and D30K), and the pig ACE2 having one radical substitution (Q24L) and one conservative substitution (D30E). Rabbit and camel species each have 4 substitutions in “hot spots”. Ruminantia species (Taurine and Zebu cattle, sheep, goat, water buffalo) have the fewest amino acid substitutions (3 substitutions) compared to human ACE2, with two conservative substitutions (D30E, L79M) and one moderately conservative substitution (M82T).

Table 4.

Amino acid substitutions in the “hot spots” of ACE2 receptors of livestock species compared to human ACE2.

| Position | 19 | 24 | 27 | 28 | 30 | 31 | 34 | 35 | 37 | 38 | 41 | 42 | 45 | 79 | 82 | 83 | 330 | 353 | 354 | 355 | 357 | 393 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | S | Q | T | F | D | K | H | E | E | D | Y | Q | L | L | M | Y | N | K | G | D | R | R |

| Donkey | L (113) | E (45) | S (89) | E (45) | H (83) | T (81) | ||||||||||||||||

| Horse | L (113) | E (45) | S (89) | E (45) | H (83) | T (81) | ||||||||||||||||

| European rabbit | L (113) | E (45) | Q (24) | T (81) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dromedary camel | L (113) | E (45) | E (56) | T (81) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bactrian camel | L (113) | E (45) | E (56) | T (81) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alpaca | L (113) | K (101) | E (56) | A (96) | I (10) | |||||||||||||||||

| Llama | L (113) | K (101) | E (56) | A (96) | I (10) | |||||||||||||||||

| American mink | L (113) | E (45) | Y (83) | E (45) | H (99) | T (81) | H (98) | |||||||||||||||

| Ferret | L (113) | E (45) | Y (83) | E (45) | H (99) | T (81) | R (125) | |||||||||||||||

| Domestic pig | L (113) | E (45) | L (99) | I (5) | T (81) | |||||||||||||||||

| Sheep | E (45) | M (15) | T (81) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Goat | E (45) | M (15) | T (81) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Taurine cattle | E (45) | M (15) | T (81) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zebu cattle | E (45) | M (15) | T (81) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Water buffalo | E (45) | M (15) | T (81) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese quail | D (65) | Gap | K (78) | A (126) | E (56) | V (84) | R (54) | E (29) | N (153) | R (91) | F (22) | N (80) | ||||||||||

| Common pheasant | D (65) | Gap | A (126) | E (56) | A (86) | R (54) | E (29) | N (153) | R (91) | F (22) | N (80) | |||||||||||

| Chicken | D (65) | Gap | A (126) | E (56) | V (84) | R (54) | E (29) | N (153) | R (91) | F (22) | N (80) | |||||||||||

| Helmeted guineafowl | D (65) | Gap | I (89) | A (126) | E (56) | V (84) | R (54) | E (29) | N (153) | R (91) | F (22) | N (80) | ||||||||||

| South African ostrich | D (65) | Gap | M (81) | T (85) | E (56) | V (84) | R (54) | E (29) | N (153) | N (142) | F (22) | K (127) | ||||||||||

| Mallard | D (65) | Gap | M (81) | A (126) | E (56) | V (84) | R (54) | E (29) | N (153) | N (142) | F (22) | N (80) |

Note: Grantham’s distances for the corresponding (by multiple alignment) pairs of amino acids are given in parentheses. Distances 0–50 are considered as conservative substitutions, 51–100 as moderately conservative, 101–150 as moderately radical, or ≥151 as radical according to the described classification (Li et al., 1984). The positions of “hot spot” residues are indicated according to human ACE2 AAS, in livestock species the position number for the corresponding amino acid may differ depending on the number of indels.

The studied bird species have significantly more substitutions in the “hot spots” compared to mammalian species. Approximately half of the “hot spot” amino acid residues differ in the studied bird species compared to humans. The nature of the substitutions varies from conservative to moderately radical, as well as one radical substitution (L79N).

Among the “hot spot” amino acids in ACE2, there are both those that are not subject to substitution across all studied species (F28, E37, L45, N330, K353, D355, R357, R393) and those that differ in all species compared to the corresponding amino acids of human ACE2 (D30, M82).

3.3. Modeling and stability evaluation of the structures of RBD-ACE2 complexes

To draw conclusions regarding the implications of the “hot spot” amino acid substitutions, as well as other interspecies differences in AASs of livestock ACE2s compared to humans, it was imperative to assess the stability of the formed RBD-ACE2 complexes. To accomplish this, the study performed calculations of the level of the Gibbs binding free energy (ΔG) of the RBD-ACE2 complexes and its changes due to individual amino acid substitutions (ΔΔG). A decrease of the ΔG indicates higher stability of the complex, whereas an increase of the ΔG signifies lower stability (Owoloye et al., 2022).

Table 5 shows the prediction of ΔΔG of the RBD-ACE2 complex under the influence of individual “hot spot” amino acid substitutions in ACE2. Most of the numerical estimates indicate a destabilizing effect of amino acid substitutions in livestock ACE2s compared to the human receptor. The bioinformatic tool BindProfX identifies all the investigated substitutions as increasing the binding free energy and, accordingly, destabilizing the RBD-ACE2 complex. However, other predictors such as BeAtMuSiC, mCSM-PPI-2, MutaBind2, and SAAMBE-3D define some amino acid substitutions that reduce the binding free energy and, therefore, stabilize the RBD-ACE2 complex, increasing the probability of successful virus interaction with host cells. Among the amino acid substitutions identified as stabilizing the complex by at least one predictive tool are S19D, Q24L/E, D30E/K, K31E, Q42E, L79H/M/N, M82R, Y83F, G354H/N/K. All bioinformatic tools unanimously identified the remaining amino acid substitutions as destabilizing the RBD-ACE2 complex.

Table 5.

Impact of amino acid substitutions in ACE2 receptor on changes in the binding free energy (ΔΔG) of the RBD-ACE2 complex (kcal/mol).

| Position | Mutation | Bionformatic tools | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BeAtMuSiC | BindProfX | mCSM-PPI2 | MutaBind2 | SAAMBE-3D | ||

| S19 | D | 0.22 | 1.577 | −0.042 | 0.36 | 0.42 |

| Q24 | L | −0.18 | 0.863 | 0.707 | 1.47 | 0.71 |

| Q24 | E | 1.15 | 0.736 | −0.245 | 0.92 | 0.69 |

| T27 | K | 0.98 | 1.385 | 0.214 | 0.51 | 0.88 |

| I | 0.54 | 1.364 | −0.109 | 0.11 | 0.50 | |

| M | 0.11 | 1.511 | 0.476 | 0.90 | 0.45 | |

| D30 | E | 0.74 | 1.569 | −0.464 | −0.68 | 0.92 |

| K | 0.66 | 1.912 | 0.680 | −0.02 | 0.03 | |

| A | 1.38 | 1.993 | 0.401 | 0.72 | 0.45 | |

| T | 0.53 | 1.997 | 0.439 | 0.58 | 0.74 | |

| K31 | E | 1.55 | 0.750 | −0.822 | 0.91 | 0.96 |

| H34 | S | 2.01 | 2.010 | 0.468 | 0.51 | 0.43 |

| Q | 1.04 | 1.958 | 0.091 | 0.80 | 0.45 | |

| Y | 0.90 | 1.950 | 0.081 | 0.80 | 0.23 | |

| L | 1.20 | 1.801 | 0.658 | 0.75 | 0.80 | |

| V | 1.39 | 1.979 | 0.615 | 0.63 | 0.64 | |

| A | 2.16 | 1.923 | 0.439 | 0.88 | 0.48 | |

| E35 | R | 0.10 | 0.552 | 0.305 | 0.61 | 0.41 |

| D38 | E | 0.94 | 1.569 | 0.373 | 0.27 | 0.55 |

| Y41 | H | 1.43 | 2.034 | 1.889 | 2.86 | 0.52 |

| Q42 | E | 0.58 | 0.736 | −0.78 | 0.50 | 0.23 |

| L79 | A | 1.34 | 2.044 | 0.739 | 0.44 | 0.87 |

| H | 1.06 | 2.210 | 0.662 | −0.81 | 0.96 | |

| M | 0.44 | 2.102 | 0.027 | −0.01 | 0.34 | |

| I | 0.35 | 1.869 | 0.450 | 0.62 | 0.65 | |

| N | 1.54 | 2.087 | 0.813 | −0.83 | 0.68 | |

| M82 | T | 0.41 | 0.971 | 0.294 | 0.64 | 0.54 |

| I | 0.36 | 0.714 | 0.478 | 0.55 | 0.42 | |

| R | −0.02 | 0.991 | −0.031 | −0.07 | 0.59 | |

| N | 0.37 | 1.003 | 0.442 | 0.47 | 0.76 | |

| Y83 | F | 0.61 | 1.656 | −0.680 | −0.27 | 0.14 |

| G354 | H | 0.62 | 2.933 | 0.785 | 0.99 | −0.15 |

| R | 1.14 | 2.921 | 1.139 | 0.64 | 0.97 | |

| N | 1.23 | 2.876 | −0.253 | 0.64 | 0.37 | |

| K | 2.09 | 2.919 | 0.657 | −0.42 | 0.38 | |

Note: Stabilizing mutations are marked in bold, and destabilizing ones are in standard font. For mmCSM-PPI, all ΔΔG values are written with the opposite sign to match them with other tools.

The results of the ΔG calculations are shown in Table 6. The calculated ΔG values for human ACE2 complexed with the same SARS-CoV-2 variants, are presented for structures obtained using two methods (point mutagenesis and homology modeling). Differences in the obtained values can be attributed to the higher accuracy of the point mutagenesis method. Thus, the ΔG values obtained using the point mutagenesis method for complexes involving human ACE2 will be considered the base ones in further in this study for comparison with complexes involving ACE2s of livestock species. In many cases, the ΔG levels characterizing the stability of RBD-ACE2 complexes involving certain animal receptors and SARS-CoV-2 variants are close to the corresponding values of complexes involving human ACE2. However, in some cases, the ΔG for animal complexes is lower, indicating greater stability and more efficient interactions with the virus RBD.

Table 6.

Binding free energy (ΔG) of complexes formed by ACE2s of human and livestock species with RBDs of different SARS-CoV-2 variants (kcal/mol).

|

Note:point. mut. corresponds to structures including human ACE2 and obtained using point mutagenesis approach, hom. mod. corresponds to structures including human ACE2 and obtained using homology modeling. All structures including ACE2s of animal species were obtained using homology modeling. More stable RBD-ACE2 complexes with ΔG lower than the base value –61.89 kcal/mol are marked in blue, and less stable complexes with ΔG higher than the base value in pink.

Based on the data in Table 6, graphs were built (Fig. 2, a-b), to illustrate the distribution of the ΔG for all constructed RBD-ACE2 complexes and demonstrate the dynamics of changes in the virus affinity for ACE2 resulting from mutations occurring in the virus RBD. In addition, the graphs clearly show in which cases ACE2 of mammalian and bird species form more stable complexes with RBD of the virus than human ACE2. The ΔG value of –61.89 kcal/mol, corresponding to the complex between the WT virus and human ACE2, was taken as the base value (baselines on graphs), since it is primary for the occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 specificity in infecting human cells. It should be noted that the ΔG values for complexes involving ACE2s of ferrets and American minks with all SARS-CoV-2 variants, as well as complexes involving ACE2s of horses, donkeys, chickens, and helmeted guineafowls with the RBD of the Omicron variant, are below the baseline. This suggests that these complexes are more stable than the primary complex between the RBD of the WT SARS-CoV-2 and human ACE2, indicating high risks of successful virus interactions with these animals.

Fig. 2.

Dynamics of the binding free energy (ΔG, kcal/mol) of the RBD-ACE2 complexes for different biological species during the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Graphs are build based on the calculations of the ΔG obtained for complexes involving ACE2 receptors of various biological species and RBDs of different SARS-CoV-2 variants using the MM/GBSA method. a - graph comparing the ΔG values of complexes involving ACE2s of mammalian species with human; b - graph comparing the ΔG values of complexes involving ACE2s of bird species with human. The baseline, representing the ΔG value for complex of the WT virus with human ACE2 (−61.89 kcal/mol), is indicated by a dotted line.

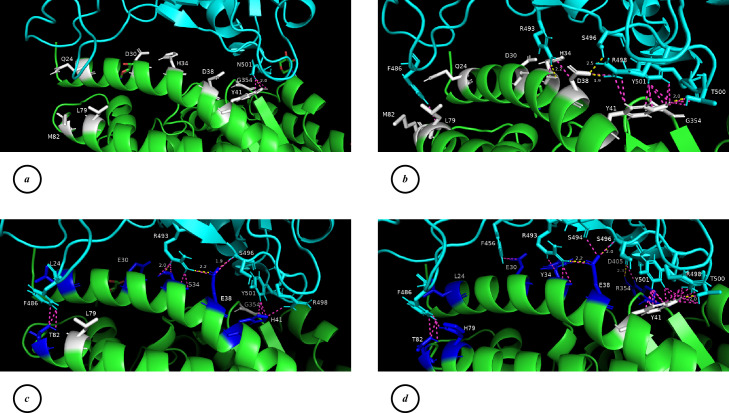

The visualization of the most stable RBD-ACE2 complexes was performed (Fig. 3, a–d) to assess the chemical bonds formed between ACE2 and RBD. The RBD-ACE2 complex formed by the Omicron variant with the human receptor (Fig. 3, b) is the most stable among those studied, as indicated by the calculated ΔG values. It clearly outperforms the complex formed by the WT virus with the human receptor (Fig. 3, a). This enhanced stability can be attributed to the formation of a significantly larger number of H-bonds and other favorable contacts in the interface of the complex, mainly resulting from the presence of Q493R, G496S, Q498R, and N501Y mutations in the RBD of the virus.

Fig. 3.

Visualization of the chemical bonds forming between interface amino acid residues of the RBD-ACE2 complexes. a – WT virus RBD / human ACE2, b – Omicron RBD / human ACE2, c – Omicron RBD / horse ACE2, d – Omicron RBD / ferret ACE2. ACE2 is shown in green; RBD is shown in cyan; variable “hot spot” amino acids of human ACE2 are shown in white; those amino acids that are substituted in horse and mink ACE2s compared to human are shown in blue; H-bonds are shown in yellow; other interchain contacts with a distance of fewer than 3.0 Å are shown in light mangenta. The distances between the atoms are indicated only for H-bonds.

The RBD-ACE2 complex formed between the Omicron variant and the horse receptor (Fig. 3, c) is relatively less stable than the corresponding complex with the human receptor, but still significantly more stable than most of those studied, including the complex of the WT virus with human ACE2. This stability is facilitated by the formation of new contacts between ACE2 residue T82 and RBD residue F486, rearrangement of contacts involving ACE2 residues S34 and E38, and contacts formed by the aromatic ring of ACE2 residue H41 (for comparison, the aromatic ring of Y41 in human ACE2 contributed more stability).

The RBD-ACE2 complex formed between the Omicron variant and the ferret receptor (Fig. 3, d) is nearly as stable as the complex with the human receptor. This is due to several favorable interactions between the “hot spot” amino acid residues in the complex interface. ACE2 residues H79 and T82 form additional contacts with RBD residue F486, ACE2 residue E30 forms a contact with RBD residue F456, ACE2 residues Y34 and E38 create a distinct set of contacts compared to those in the human ACE2, and amino acid Y41, crucial for interaction, remains unchanged in the ferret receptor. Furthermore, ACE2 residue R354 forms an H-bond with RBD residue D405, which is absent in the complex involving human receptor. Thus, the horse and ferret ACE2 receptors can successfully interact with the RBD of the Omicron variant, despite having substitutions in the “hot spots” compared to the human ACE2 receptor. Similar patterns can be observed for complexes with ACE2s of donkeys and American minks.

4. Discussion

This study examined the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to interact with ACE2 receptors of various livestock species using a comprehensive bioinformatic approach. The assessment involved comparative and phylogenetic analyses, modeling of three-dimensional structures of RBD-ACE2 complexes, and evaluation of their energy stability.

In this study, CDSs and AASs of ACE2 from a wide range of animal species, belonging to two biological classes (Aves and Mammalia), were compared. In addition, a phylogenetic tree and a distance matrix were constructed, which together allowed both clustering biological species based on data of the primary sequences of their ACE2s and evaluating the similarity between ACE2 receptors in animals with human ACE2. Assessing the degrees of the identity and similarity of ACE2s of livestock species, along with determining phylogenetic relationships, can help form initial hypotheses about the likelihood of interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and the ACE2 receptors of specific species. This is because ACE2 receptors with sequences similar to that of humans are more likely to form stable RBD-ACE2 complexes compared to ACE2 receptors of phylogenetically distant species with a low degree of similarity to human ACE2. Additionally, it cannot be excluded that animal species with a slightly different ACE2 sequence may exhibit higher susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 compared to humans, thanks to several amino acid substitutions that stabilize the interaction with the RBD of the virus. The results of the in vitro study (Conceicao et al., 2020) indicated that SARS-CoV-2 receptor usage for some mammalian species may be even higher compared to humans. Conversely, receptor usage for bird species is rather lower (Conceicao et al., 2020), as well as degrees of the identity of their ACE2s to humans. Therefore, existing experimental data support the use of estimates of the ACE2 degrees of the identity and similarity to approximate potential interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and receptors in specific animal species.

Analyzing the distribution of amino acid substitutions in the “hot spots” revealed that species with higher degrees of the similarity of the ACE2 AASs to human ACE2 do not consistently exhibit greater similarities in the “hot spots”. For example, donkey and horse ACE2 receptors, while highly similar to humans, have relatively more “hot spot” substitutions than some other mammalian species. In addition, surprisingly, American minks and ferrets have 7 “hot spot” substitutions compared to human ACE2, and experimental data indicate the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect these animals (Meekins et al., 2021). Comparative sequence analyses obtained in this study is generally in good agreement with some other studies devoted to the topic of interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and animal species (Damas et al., 2020; Low-Gan et al., 2021).

Assessing the ΔΔG under the influence of “hot spot” amino acid substitutions present in ACE2s of livestock species compared to human ACE2 indicates that most of these substitutions destabilize the RBD-ACE2 complex, thereby decreasing the virus’s potential to interact successfully with ACE2 receptors of these species. This showed that at least the WT virus had greater specificity for human ACE2. However, it is important to note that the ΔΔG calculations were conducted based on the complex involving the WT virus, and it should be considered that mutations of the latter variants can counterbalance the decrease in ACE2 receptor affinity for livestock species. At the same time, it is worth paying attention to those amino acid substitutions for which some of the used bioinformatic tools predicted a stabilizing effect on the formed RBD-ACE2 complexes. Among them is the conservative substitution D30E, which occurs in many livestock species. The data presented in (Li et al., 2020) and (Chan et al., 2020) also indicate that the directed mutation D30E in ACE2 improves the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 S-protein and ACE2 due to the enhancement of the salt-bridge interaction between the residue E30 of the ACE2 and residue K417 of SARS-CoV-2 S-protein. Among other potentially stabilizing mutations, L79M, present in Ruminantia (Taurine and Zebu cattle, sheep, goat, water buffalo), as well as M82R and Y83F, present in bird species, should be noted. Nevertheless, if in Ruminantia species two of the three substitutions in “hot spots” (D30E, L79M) are potentially stabilizing, then for bird species, the possible stabilizing effect of M82R and Y83F is neutralized by a numerous of other destabilizing substitutions. Thus, the results obtained in this study based on the “hot spot” analysis and the ΔΔG calculations for Ruminantia species indicate relatively greater risks that the virus will successfully interact with their ACE2 receptors: only three “hot spot” amino acids differ from those in humans, while two of the three substitutions can potentially stabilize the RBD-ACE2 complex. There are data from other studies that have suggested both the probable ability of SARS-CoV-2 to recognize the ACE2 receptors of Bovidae (Luan et al., 2020) and the reduced ability of cattle ACE2 to bind to SARS-CoV-2 (Low-Gan et al., 2021).

The assessment of the total ΔG level of RBD-ACE2 complexes conducted in this study is of utmost importance. This assessment considers the combined effect of all amino acids on the creation of a stable conformation of the RBD-ACE2 complex and the formation of interface contacts. Additionally, in this study, the ΔG calculation was performed not only for the WT virus but also for five SARS-CoV-2 variants (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron BA.1). This approach enables tracking the virus’s adaptation to ACE2 receptor binding.

Horses and donkeys have ACE2 receptors with high degrees of the similarity to human ACE2. In these species, the stability of the RBD-ACE2 complex, as evaluated by the ΔG calculation, decreases for the WT virus and increases for latter SARS-CoV-2 variants. Notably, the Omicron variant harbors a set of mutations that demonstrate the highest specificity for horse and donkey ACE2 receptors, forming a network of favorable chemical contacts in the RBD-ACE2 interface. Throughout evolution, SARS-CoV-2 variants have increased their affinity for horse and donkey ACE2s, underscoring the need of further monitoring. Other recent studies investigating in vitro interactions between the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 and horse ACE2 (Lan et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022) have also highlighted the potential susceptibility of horses to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The complexes formed by some variants with rabbit ACE2 exhibit higher ΔG values compared to similar complexes with human ACE2, indicating a reduced affinity of the virus for rabbit ACE2. However, in the cases of Beta and Gamma variants, the ΔG values are slightly lower than those for complexes with human ACE2, suggesting that complexes with rabbit ACE2 are relatively more stable. Looking at studies (Preziuso, 2020; Mykytyn et al., 2021; Bosco-Lauth et al., 2021) it can be concluded that rabbit species may interact with SARS-CoV-2, including forming energetically stable RBD-ACE2 complexes on the cell surface, but the subsequent consequences of such interactions, including susceptibility to the virus and further disease development, may differ.

In camel species (dromedary, bactrian), all virus variants showed reduced affinity for camel receptors. However, the trend of stabilizing RBD-ACE2 complexes observed from the WT virus to the latter variants suggests that evolutionary changes in the virus have slightly enhanced its potential to interact with camel cell receptors, so further monitoring is needed. Llamas, being phylogenetically related to camels, exhibit notably weaker interactions with the virus RBD. This reduced interaction is in particular attributed to more radical differences in the “hot spots” of llama ACE2.

In the case of pigs, the ΔG values of RBD-ACE2 complexes for all virus variants are relatively higher compared to humans, indicating a decrease in the stability of interactions between the virus and the pig ACE2 receptor. Simultaneously, in vitro studies have demonstrated a relatively high affinity of SARS-CoV-2 for the pig receptor (Zhou et al., 2020; Conceicao et al., 2020). Several other studies, attempting to induce experimental infection in pigs, have indicated that pigs are not susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 (Shi et al., 2020; Haddock et al., 2022; Vergara-Alert et al., 2021; Lean et al., 2022). Pigs may possess protective mechanisms against COVID-19 (Nelli et al., 2021) which could prevent the development of disease even in cases when the virus successfully interacts with the ACE2 receptor.

As for Taurine cattle, the small number of amino acid substitutions in the “hot spots” contributes to the formation of RBD-ACE2 complexes in stability comparable to complexes involving the human receptor in cases with early virus variants. Conversely, the Omicron variant has a lower specificity to the receptors of Ruminantia species compared to human ACE2. Several studies mentioned in (Meekins et al., 2021) have reported the low susceptibility of cattle to experimental SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, concerns arise regarding the further evolution of SARS-CoV-2, as well as the potential emergence of recombinants with bovine coronavirus (Wernike et al., 2022).

The complexes formed between the ACE2 receptors of avian species and the RBDs of the WT and early variants of the virus had low stability, with the ΔG values differing from the corresponding values observed for humans. Additionally, noteworthy changes in the ΔG values were observed for the complexes involving the Omicron variant, suggesting the presence of a highly effective set of mutations enabling interactions even with avian receptors. Moreover, the ΔG level of avian ACE2s complexes with Omicron variant approaches the baseline (Fig. 2) for some species (ostrich, mallard) and even falls below it for others (chicken, helmeted guineafowl). In other words, it exceeds the threshold of the initial specificity of the WT virus to the human receptor. However, the likelihood of the Omicron variant undergoing a full replication cycle and causing COVID-19 in bird species, despite successful binding to ACE2, remains questionable given the substantial phylogenetic distance and physiological differences between humans and birds. Another in silico study (Mesquita et al., 2023) identified strong molecular interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and helmeted guineafowl (N. meleagris). Alternatively, several studies indicated the lack of susceptibility in chickens, turkeys, ducks, quail, and geese to experimental SARS-CoV-2 infections (Shi et al., 2020; Suarez et al., 2020).

The ΔG calculations obtained for ACE2 of ferrets and American minks yield results of significant importance. The receptors of these species form highly stable complexes with the RBD, a slight dependence on the SARS-CoV-2 variant. The RBD-ACE2 complexes formed by the receptors of these animals, along with the RBD of WT and earlier variants of the virus, are thus even more stable than those complexes with human ACE2. The Omicron variant also showed comparable affinity for ACE2s of humans, minks, and ferrets. The high affinity of SARS-CoV-2 for ACE2 receptors of minks and ferrets is explained by the formation of favorable contacts in the interface of the complexes, facilitated by stabilizing amino acid substitutions (D30E, H34Y, G354H/R). These findings not only indicate a persistent risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to ferrets and minks that does not decrease during the evolution and the emergence of new variants of the virus but are also confirmed by the evidence of natural (Pomorska-Mól et al., 2021; Gortázar et al., 2021) and experimental infections (Meekins et al., 2021) of these animals. Moreover, both transmissions of the virus from humans to minks and reverse transmissions from minks to humans have been documented. It is know that the presence of Y453F, F486L, and N501T mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 RBD enhances virus adaptation to infect minks and ferrets (Welkers et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2022; Su et al., 2022). A variant of the virus with three simultaneous mutations is likely to pose the greatest risk to these animals. At the same time, since humans continue to be the main reservoir of COVID-19, a further increase or decrease in the specificity of the virus to other species still largely depends on the set of mutations in these SARS-CoV-2 variants that will be predominant in the human population.

Thus, for some animal species of agricultural importance (horses, donkeys, minks, and ferrets), there are significant risks of transmission and spread among them of the Omicron sublineages due to increased ACE2 receptor affinity evaluated for these animal species. The Omicron, thanks to a set of beneficial mutations, also increased the stability of the RBD-ACE2 complexes formed with receptors of camel and bird species. Given the ongoing high risks of COVID-19 spread among animals, it is essential to monitor the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 and the ability of new virus variants to infect not only humans but also animals. This can be done both using the bioinformatic approache presented in this study and expanding observations by including in the monitoring programs also the prediction of the virus evolution and the assessment of rare virus variants for their infectivity for animals. After all, it may not necessarily be the most common SARS-CoV-2 variant that will have the ability to overcome the interspecies barrier (Zhou et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2022). On the contrary, it is possible that a virus with a rare useful set of mutations could be accidentally transmitted from a human to some animal. Therefore, it seems important to maintain continuous monitoring of the SARS-CoV-2 ability to infect animal species.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the interactions between the RBDs of different SARS-CoV-2 variants and ACE2 receptors of livestock species using a versatile bioinformatic approach. Comparative and phylogenetic analyses were conducted on ACE2 receptor sequences for humans and 21 animal species. The study also assessed differences in the “hot spot” amino acids in the ACE2 receptors. To evaluate the stability of RBD-ACE2 complexes formed between different SARS-CoV-2 variants and animal receptors, calculations of the ΔG and ΔΔG were performed. The findings indicate that the ACE2 receptors of ferrets, minks, horses, and donkeys can effectively interact with the RBD of the Omicron variant. These interactions are facilitated by the formation of favorable chemical bonds in the interface of the RBD-ACE2 complex, despite differences in “hot spot” amino acids compared to the human receptor. Consequently, there are concerns about the potential spread of the Omicron variant among these animal species. Given the high mutability of the virus, the risks of future SARS-CoV-2 variants acquiring specificity to new animal species remain significant. To monitor the situation and prevent the emergence of new reservoirs of COVID-19 among animals, the continued use and expansion of the bioinformatic approach presented in this study may be relevant.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Academy of Agrarian Sciences of Ukraine.

Data availability statement

All models of RBD-ACE2 complexes built as part of the study are freely available in PDB format at the following link: https://svinarstvo.com/covid19/. Additional data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethical statement

The methodology of the study provided exclusively for the use of in silico methods. Authors confirm that the study did not involve any animal or human subjects.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to O. Tsereniuk for his assistance in placing the models of the RBD-ACE2 complexes on the web site of the Institute of Pig Breeding and Agroindustrial Production of the National Academy of Agrarian Sciences of Ukraine, and to M. Pidtereba for creating the corresponding web page.

References

- Barton M.I., MacGowan S.A., Kutuzov M.A., Dushek O., Barton G.J., van der Merwe P.A. Effects of common mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD and its ligand, the human ACE2 receptor on binding affinity and kinetics. eLife. 2021;10:e70658. doi: 10.7554/eLife.70658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashor, L., Gagne, R.B., Bosco-Lauth, A., Bowen, R., Stenglein, M., & VandeWoude, S. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 evolution in animals suggests mechanisms for rapid variant selection. bioRxiv: The preprint server for biology, 2021.03.05.434135. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.05.434135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Borkotoky S., Dey D., Hazarika Z. Interactions of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) and SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain (RBD): A structural perspective. Molecular Biology Reports. 2023;50(3):2713–2721. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-08193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco-Lauth A.M., Root J.J., Porter S.M., Walker A.E., Guilbert L., Hawvermale D., Pepper A., Maison R.M., Hartwig A.E., Gordy P., Bielefeldt-Ohmann H., Bowen R.A. Peridomestic mammal susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 infection. Emerging infectious diseases. 2021;27(8):2073–2080. doi: 10.3201/eid2708.210180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.K., Dorosky D., Sharma P., Abbasi S.A., Dye J.M., Kranz D.M., Herbert A.S., Procko E. Engineering human ACE2 to optimize binding to the spike protein of SARS coronavirus 2. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2020;369(6508):1261–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.abc0870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conceicao C., Thakur N., Human S., Kelly J.T., Logan L., Bialy D., Bhat S., Stevenson-Leggett P., Zagrajek A.K., Hollinghurst P., Varga M., Tsirigoti C., Tully M., Chiu C., Moffat K., Silesian A.P., Hammond J.A., Maier H.J., Bickerton E., Shelton H.…Bailey D. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein has a broad tropism for mammalian ACE2 proteins. PLoS Biology. 2020;18(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damas J., Hughes G.M., Keough K.C., Painter C.A., Persky N.S., Corbo M., Hiller M., Koepfli K.P., Pfenning A.R., Zhao H., Genereux D.P., Swofford R., Pollard K.S., Ryder O.A., Nweeia M.T., Lindblad-Toh K., Teeling E.C., Karlsson E.K., Lewin H.A. Broad host range of SARS-CoV-2 predicted by comparative and structural analysis of ACE2 in vertebrates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2020;117(36):22311–22322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010146117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaro N., Lorusso A. Novel human coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A lesson from animal coronaviruses. Veterinary Microbiology. 2020;244 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehouck Y., Kwasigroch J.M., Rooman M., Gilis D. BeAtMuSiC: Prediction of changes in protein-protein binding affinity on mutations. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41(Web Server issue):W333–W339. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobeil S.M., Janowska K., McDowell S., Mansouri K., Parks R., Stalls V., Kopp M.F., Manne K., Li D., Wiehe K., Saunders K.O., Edwards R.J., Korber B., Haynes B.F., Henderson R., Acharya P. Effect of natural mutations of SARS-CoV-2 on spike structure, conformation, and antigenicity. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2021;373(6555):eabi6226. doi: 10.1126/science.abi6226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke H., Case D.A. Converging free energy estimates: MM-PB(GB)SA studies on the protein-protein complex Ras-Raf. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004;25(2):238–250. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S.A., Weiss S.R. Origins and pathogenesis of Middle East respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus: Recent advances. F1000Research. 2017;6:1628. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11827.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortázar C., Barroso-Arévalo S., Ferreras-Colino E., Isla J., de la Fuente G., Rivera B., Domínguez L., de la Fuente J., Sánchez-Vizcaíno J.M. Natural SARS-CoV-2 infection in Kept Ferrets, Spain. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2021;27(7):1994–1996. doi: 10.3201/eid2707.210096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham R. Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1974;185(4154):862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4154.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N., Peitsch M.C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18(15):2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock E., Callison J., Seifert S.N., Okumura A., Tang-Huau T.L., Leventhal S.S., Lewis M.C., Lovaglio J., Hanley P.W., Shaia C., Hawman D.W., Munster V.J., Jarvis M.A., Richt J.A., Feldmann H. Three-week old pigs are not susceptible to productive infection with SARS-COV-2. Microorganisms. 2022;10(2):407. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10020407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S., Henikoff J.G. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(22):10915–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.C., Goldstein S.A., Rasmussen A.L., Robertson D.L., Crits-Christoph A., Wertheim J.O., Anthony S.J., Barclay W.S., Boni M.F., Doherty P.C., Farrar J., Geoghegan J.L., Jiang X., Leibowitz J.L., Neil S., Skern T., Weiss S.R., Worobey M., Andersen K.G., Garry R.F.…Rambaut A. The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review. Cell. 2021;184(19):4848–4856. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Yang C., Xu X.F., Xu W., Liu S.W. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta pharmacologica Sinica. 2020;41(9):1141–1149. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.T., Taylor W.R., Thornton J.M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Computer Applications in the Biosciences: CABIOS. 1992;8(3):275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J., Chen P., Liu W., Ren W., Zhang L., Ding Q., Zhang Q., Wang X., Ge J. Structural insights into the binding of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and hCoV-NL63 spike receptor-binding domain to horse ACE2. Structure (London, England: 1993) 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.str.2022.07.005. S0969-2126(22)00274-X. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang X. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581(7807):215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lean F.Z.X., Núñez A., Spiro S., Priestnall S.L., Vreman S., Bailey D., James J., Wrigglesworth E., Suarez-Bonnet A., Conceicao C., Thakur N., Byrne A.M.P., Ackroyd S., Delahay R.J., van der Poel W.H.M., Brown I.H., Fooks A.R., Brookes S.M. Differential susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 in animals: Evidence of ACE2 host receptor distribution in companion animals, livestock and wildlife by immunohistochemical characterisation. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 2022;69(4):2275–2286. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.H., Wu C.I., Luo C.C. Nonrandomness of point mutation as reflected in nucleotide substitutions in pseudogenes and its evolutionary implications. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1984;21(1):58–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02100628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang H., Tang X., Fang S., Ma D., Du C., Wang Y., Pan H., Yao W., Zhang R., Zou X., Zheng J., Xu L., Farzan M., Zhong G. SARS-CoV-2 and three related coronaviruses utilize multiple ACE2 orthologs and are potently blocked by an improved ACE2-Ig. Journal of Virology. 2020;94(22) doi: 10.1128/JVI.01283-20. e01283-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likic V.A., Gooley P.R., Speed T.P., Strehler E.E. A statistical approach to the interpretation of molecular dynamics simulations of calmodulin equilibrium dynamics. Protein science: A Publication of the Protein Society. 2005;14(12):2955–2963. doi: 10.1110/ps.051681605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H., Baek A., Kim J., Kim M.S., Liu J., Nam K.Y., Yoon J., No K.T. Hot spot profiles of SARS-CoV-2 and human ACE2 receptor protein protein interaction obtained by density functional tight binding fragment molecular orbital method. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):16862. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73820-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low-Gan J., Huang R., Kelley A., Jenkins G.W., McGregor D., Smider V.V. Diversity of ACE2 and its interaction with SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain. The Biochemical Journal. 2021;478(19):3671–3684. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20200908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan J., Jin X., Lu Y., Zhang L. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein favors ACE2 from Bovidae and Cricetidae. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020;92(9):1649–1656. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv L., Li G., Chen J., Liang X., Li Y. Comparative genomic analyses reveal a specific mutation pattern between human Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and Bat-CoV RaTG13. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.584717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytras S., Xia W., Hughes J., Jiang X., Robertson D.L. The animal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2021;373(6558):968–970. doi: 10.1126/science.abh0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira F., Pearce M., Tivey A., Basutkar P., Lee J., Edbali O., Madhusoodanan N., Kolesnikov A., Lopez R. Search and sequence analysis tools services from EMBL-EBI in 2022. Nucleic Acids Research. 2022:gkac240. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac240. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdy M., Younis W., Ewaida Z. An overview of SARS-CoV-2 and animal infection. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.596391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meekins D.A., Gaudreault N.N., Richt J.A. Natural and experimental SARS-CoV-2 infection in domestic and wild animals. Viruses. 2021;13(10):1993. doi: 10.3390/v13101993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita F.P., Noronha Souza P.F., Aragão D.R., Diógenes E.M., da Silva E.L., Amaral J.L., Freire V.N., de Souza Collares Maia Castelo-Branco D., Montenegro R.C. In silico analysis of ACE2 from different animal species provides new insights into SARS-CoV-2 species spillover. Future Virology. 2023 doi: 10.2217/fvl-2022-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykytyn A.Z., Lamers M.M., Okba N., Breugem T.I., Schipper D., van den Doel P.B., van Run P., van Amerongen G., de Waal L., Koopmans M., Stittelaar K.J., van den Brand J., Haagmans B.L. Susceptibility of rabbits to SARS-CoV-2. Emerging Microbes & Infections. 2021;10(1):1–7. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1868951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman S.B., Wunsch C.D. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1970;48(3):443–453. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelli R.K., Phadke K.S., Castillo G., Yen L., Saunders A., Rauh R., Nelson W., Bellaire B.H., Giménez-Lirola L.G. Enhanced apoptosis as a possible mechanism to self-limit SARS-CoV-2 replication in porcine primary respiratory epithelial cells in contrast to human cells. Cell Death Discovery. 2021;7(1):383. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00781-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owoloye A.J., Ligali F.C., Enejoh O.A., Musa A.Z., Aina O., Idowu E.T., Oyebola K.M. Molecular docking, simulation and binding free energy analysis of small molecules as PfHT1 inhibitors. PloS one. 2022;17(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahari S., Li G., Murthy A.K., Liang S., Fragoza R., Yu H., Alexov E. SAAMBE-3D: Predicting Effect of mutations on protein-protein interactions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21(7):2563. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak A., Adegboye O.A., Adekunle A.I., Rahman K.M., McBryde E.S., Eisen D.P. Economic consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak: The need for epidemic preparedness. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020;8:241. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomorska-Mól M., Włodarek J., Gogulski M., Rybska M. Review: SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks - an overview of current knowledge on occurrence, disease and epidemiology. Animal: An International Journal of Animal Bioscience. 2021;15(7) doi: 10.1016/j.animal.2021.100272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preziuso S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) exhibits high predicted binding affinity to ACE2 from lagomorphs (Rabbits and Pikas) Animals: An Open Access Journal From MDPI. 2020;10(9):1460. doi: 10.3390/ani10091460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.T., Sobur M.A., Islam M.S., Ievy S., Hossain M.J., El Zowalaty M.E., Rahman A.T., Ashour H.M. Zoonotic diseases: Etiology, impact, and control. Microorganisms. 2020;8(9):1405. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues C., Myung Y., Pires D., Ascher D.B. mCSM-PPI2: Predicting the effects of mutations on protein-protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47(W1):W338–W344. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saied A.A., Metwally A.A. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concerns in animals: An unmonitored rising health threat. Virusdisease. 2022;33(4):466–476. doi: 10.1007/s13337-022-00794-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladino V., Algeri D., Auriemma V. The psychological and social impact of Covid-19: New perspectives of well-being. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, L.L.C. (2022). The PyMOL molecular graphics system, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC. (Version 2.0) [Software]. https://pymol.org.

- Shi J., Wen Z., Zhong G., Yang H., Wang C., Huang B., Liu R., He X., Shuai L., Sun Z., Zhao Y., Liu P., Liang L., Cui P., Wang J., Zhang X., Guan Y., Tan W., Wu G., et al. Susceptibility of ferrets, cats, dogs, and other domesticated animals to SARS-coronavirus 2. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2020;368(6494):1016–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.abb7015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su C., He J., Han P., Bai B., Li D., Cao J., Tian M., Hu Y., Zheng A., Niu S., Chen Q., Rong X., Zhang Y., Li W., Qi J., Zhao X., Yang M., Wang Q., Gao G.F. Molecular basis of mink ACE2 binding to SARS-CoV-2 and its mink-derived variants. Journal of Virology. 2022;96(17) doi: 10.1128/jvi.00814-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez D.L., Pantin-Jackwood M.J., Swayne D.E., Lee S.A., DeBlois S.M., Spackman E. Lack of susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV in poultry. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2020;26(12):3074–3076. doi: 10.3201/eid2612.202989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synowiec A., Szczepański A., Barreto-Duran E., Lie L.K., Pyrc K. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): A systemic infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2021;34(2) doi: 10.1128/CMR.00133-20. e00133-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Nei M., Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(30):11030–11035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2021;38(7):3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C.C.S., Lam S.D., Richard D., Owen C.J., Berchtold D., Orengo C., Nair M.S., Kuchipudi S.V., Kapur V., van Dorp L., Balloux F. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from humans to animals and potential host adaptation. Nature Communications. 2022;13:2988. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30698-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencak T.G., Csiszar A., Szalai G., Podlutsky A., Tarantini S., Fazekas-Pongor V., Papp M., Ungvari Z. Animal reservoirs of SARS-CoV-2: Calculable COVID-19 risk for older adults from animal to human transmission. GeroScience. 2021;43(5):2305–2320. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00444-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gunsteren W.F., Billeter S.R., Eising A.A., Hünenberger P.H., Krüger P., Mark A.E.…Tironi I.G. Biomolecular Simulation: The GROMOS96 Manual and User Guide. 1st ed. Biomos b.v; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara-Alert J., Rodon J., Carrillo J., Te N., Izquierdo-Useros N., Rodríguez de la Concepción M.L., Ávila-Nieto C., Guallar V., Valencia A., Cantero G., Blanco J., Clotet B., Bensaid A., Segalés J. Pigs are not susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection but are a model for viral immunogenicity studies. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 2021;68(4):1721–1725. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.F., Eaton B.T. Bats, civets and the emergence of SARS. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2007;315:325–344. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Zhang Y., Wu L., Niu S., Song C., Zhang Z., Lu G., Qiao C., Hu Y., Yuen K.Y., Wang Q., Zhou H., Yan J., Qi J. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181(4):894–904. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S., Studer G., Tauriello G., Gumienny R., Heer F.T., de Beer T., Rempfer C., Bordoli L., Lepore R., Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2018;46(W1):W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R.A., Sankaran N. Emergence of epidemic diseases: Zoonoses and other origins. Faculty Reviews. 2022;11:2. doi: 10.12703/r/11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welkers M.R.A., Han A.X., Reusken C.B.E.M., Eggink D. Possible host-adaptation of SARS-CoV-2 due to improved ACE2 receptor binding in mink. Virus Evolution. 2021;7(1):veaa094. doi: 10.1093/ve/veaa094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng G., Wang E., Wang Z., Liu H., Zhu F., Li D., Hou T. HawkDock: A web server to predict and analyze the protein-protein complex based on computational docking and MM/GBSA. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47(W1):W322–W330. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernike K., Böttcher J., Amelung S., Albrecht K., Gärtner T., Donat K., Beer M. Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 suggestive of single events of spillover to cattle, Germany. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2022;28(9):1916–1918. doi: 10.3201/eid2809.220125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020, March 11). WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 — 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020.

- World Health Organization. (2022, March 7). Joint statement on the prioritization of monitoring SARS-CoV-2 infection in wildlife and preventing the formation of animal reservoirs. https://www.who.int/news/item/07-03-2022-joint-statement-on-the-prioritization-of-monitoring-sars-cov-2-infection-in-wildlife-and-preventing-the-formation-of-animal-reservoirs.

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants.

- Xia S., Zhu Y., Liu M., Lan Q., Xu W., Wu Y., Ying T., Liu S., Shi Z., Jiang S., Lu L. Fusion mechanism of 2019-nCoV and fusion inhibitors targeting HR1 domain in spike protein. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2020;17(7):765–767. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0374-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Sakagami H., Miwa N. ACE2: The key molecule for understanding the pathophysiology of severe and critical conditions of COVID-19: Demon or Angel? Viruses. 2020;12(5):491. doi: 10.3390/v12050491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong P., Zhang C., Zheng W., Zhang Y. BindProfX: Assessing mutation-induced binding affinity change by protein interface profiles with pseudo-counts. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2017;429(3):426–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Kang X., Han P., Du P., Li L., Zheng A., Deng C., Qi J., Zhao X., Wang Q., Liu K., Gao G.F. Binding and structural basis of equine ACE2 to RBDs from SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and related coronaviruses. Nature Communications. 2022;13(1):3547. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31276-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Chen Y., Lu H., Zhao F., Alvarez R.V., Goncearenco A., Panchenko A.R., Li M. MutaBind2: Predicting the impacts of single and multiple mutations on protein-protein interactions. iScience. 2020;23(3) doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.100939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Peacock T.P., Brown J.C., Goldhill D.H., Elrefaey A.M.E., Penrice-Randal R., Cowton V.M., De Lorenzo G., Furnon W., Harvey W.T., Kugathasan R., Frise R., Baillon L., Lassaunière R., Thakur N., Gallo G., Goldswain H., Donovan-Banfield I., Dong X., et al. Mutations that adapt SARS-CoV-2 to mink or ferret do not increase fitness in the human airway. Cell Reports. 2022;38(6) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L., Chen H.D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.D., Liu M.Q., Chen Y., Shen X.R., Wang X., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All models of RBD-ACE2 complexes built as part of the study are freely available in PDB format at the following link: https://svinarstvo.com/covid19/. Additional data is available upon request from the corresponding author.