Significance

Aquaporin-4 (AQP4), the autoantigen in neuromyelitis optica (NMO), is expressed in central nervous system (CNS) and other tissues. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), the target in MOG antibody–associated disease, is restricted to the CNS. Wild-type mice resist AQP4-induced, but not MOG-induced, autoimmunity. Unlike MOG, tolerance to AQP4 in WT mice is protected by peripheral T cell–dependent apoptotic depletion of pathogenic AQP4-specific T cells. Pathogenic AQP4 epitopes identified bind MHC II with high affinity and share homology with distinct aquaporins. We postulate that there is cross-tolerance, and conversely, a break in AQP4 tolerance may permit T cell reactivity to other aquaporins. “Self-antigen mimicry” could contribute to development of autoimmune conditions associated with NMO, including Sjögren’s syndrome, possibly representing “autoimmune aquaporinopathy.”

Keywords: molecular mimicry, aquaporin-4, T cell tolerance, neuromyelitis optica, Sjögren’s syndrome

Abstract

Aquaporin-4 (AQP4)-specific Th17 cells are thought to have a central role in neuromyelitis optica (NMO) pathogenesis. When modeling NMO, only AQP4-reactive Th17 cells from AQP4-deficient (AQP4−/−), but not wild-type (WT) mice, caused CNS autoimmunity in recipient WT mice, indicating that a tightly regulated mechanism normally ensures tolerance to AQP4. Here, we found that pathogenic AQP4 T cell epitopes bind MHC II with exceptionally high affinity. Examination of T cell receptor (TCR) α/β usage revealed that AQP4-specific T cells from AQP4−/− mice employed a distinct TCR repertoire and exhibited clonal expansion. Selective thymic AQP4 deficiency did not fully restore AQP4-reactive T cells, demonstrating that thymic negative selection alone did not account for AQP4-specific tolerance in WT mice. Indeed, AQP4-specific Th17 cells caused paralysis in recipient WT or B cell-deficient mice, which was followed by complete recovery that was associated with apoptosis of donor T cells. However, donor AQP4-reactive T cells survived and caused persistent paralysis in recipient mice deficient in both T and B cells or mice lacking T cells only. Thus, AQP4 CNS autoimmunity was limited by T cell–dependent deletion of AQP4-reactive T cells. In contrast, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-specific T cells survived and caused sustained disease in WT mice. These findings underscore the importance of peripheral T cell deletional tolerance to AQP4, which may be relevant to understanding the balance of AQP4-reactive T cells in health and in NMO. T cell tolerance to AQP4, expressed in multiple tissues, is distinct from tolerance to MOG, an autoantigen restricted in its expression.

Aquaporin-4 (AQP4), a member of the ubiquitous family of water channels (1), is the principal autoantigen target for pathogenic antibodies in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMO/NMOSD), a central nervous system (CNS) autoimmune disease that may cause paralysis and blindness (2). AQP4 is expressed abundantly on astrocyte end-foot processes at the blood–brain barrier (3), the site of CNS damage in NMO, but it is also expressed in kidney, muscle, lung, and heart (1, 4, 5) tissues that are characteristically unaffected in NMO. Evidence suggests T cells may have an important role in NMO pathogenesis (2, 6). AQP4-specific antibodies in NMO serum are IgG1, a T cell–dependent IgG subclass (7). T cells can be identified in NMO lesions, and it has been established that CNS inflammation induced by T cells permits CNS entry of AQP4-specific antibodies (8, 9). NMO susceptibility is also associated with allelic MHC II genes, in particular HLA-DR17 (DRB1*0301) (10), and AQP4-specific HLA-DR-restricted CD4+ Th17 cells can be identified in the peripheral blood of NMO patients (11, 12). While these observations indicate that AQP4-specific T cells contribute to NMO pathogenesis, they do not address mechanisms responsible for the generation and regulation of those T cells.

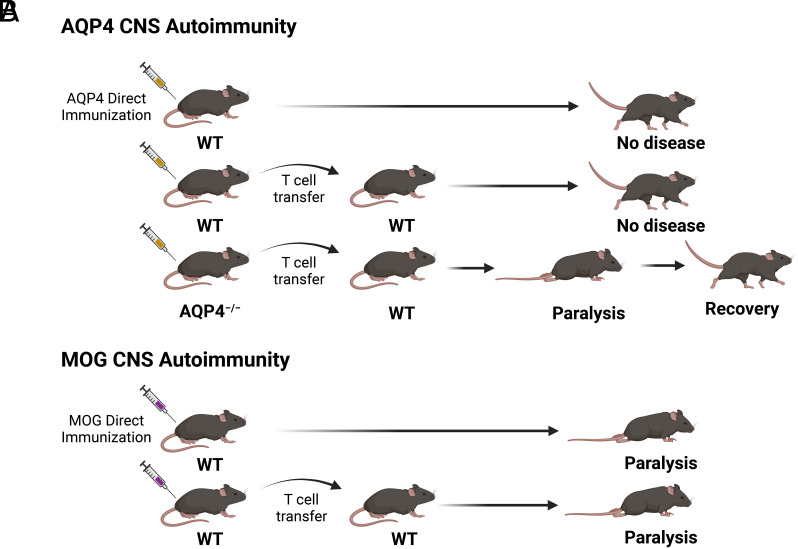

Substantial effort has been devoted to development of NMO animal models in order to investigate how AQP4-specific T cells and antibodies participate in cellular and humoral CNS autoimmune responses in vivo. Those efforts have met with limited success (13–19). Unlike experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), which is induced either by direct immunization of wild-type (WT) mice with myelin proteins or by adoptive transfer of WT myelin-specific T cells, attempts to create an AQP4-targeted NMO model in WT mice or rats by either direct immunization of AQP4 or its peptides or by adoptive transfer of WT AQP4-specific T cells were unsuccessful. However, two AQP4 determinants that were predicted to bind MHC II (I-Ab) avidly elicited robust proliferative T cell responses in AQP4-deficient (AQP4−/−) mice but not in WT mice (18). When used as donor T cells, Th17-polarized AQP4 peptide-specific cells from AQP4−/− mice, but not from WT mice, induced paralysis and CNS inflammation in WT mice lasting several days (Fig. 1) (18, 20). Thus, mechanisms of tolerance that control T cell reactivity to AQP4 and myelin autoantigens may be distinct.

Fig. 1.

AQP4-specific Th17 cells from AQP4-deficient, but not from WT, mice induce CNS autoimmune disease. (A) WT mice are resistant to AQP4 CNS autoimmune disease by direct immunization with AQP4 (13, 14, 17, 18). Donor WT AQP4-specific T cells do not induce CNS autoimmune disease in WT recipient mice. In contrast, donor AQP4-specific T cells from AQP4-deficient mice induce short-lived clinical and histologic CNS autoimmune disease in recipient WT mice. (B) WT mice are susceptible to MOG CNS autoimmune disease (i.e., EAE) induced by immunization with MOG or by adoptive transfer donor WT MOG-specific T cells. Graphics created using BioRender.com.

Thymic negative selection and peripheral regulation are two distinct processes that safeguard against T cell reactivity to tissue-specific antigens. The inability to generate pathogenic AQP4-reactive T cells from WT mice suggested that development of AQP4-reactive T cells may be prevented by thymic negative selection. Here, we examined how both central and peripheral mechanisms may contribute to T cell tolerance to AQP4 in WT mice. By examining peptide binding to purified MHC II molecules biochemically, we observed that the two pathogenic AQP4 T cell determinants bind I-Ab with higher affinity than nonpathogenic AQP4 T cell epitopes or the immunodominant encephalitogenic MOG p35–55. Single-cell T cell receptor sequencing (scTCR-Seq) was performed to examine AQP4-specific TCR α/β usage in combination with use of MHC II (I-Ab):AQP4 peptide tetramers to identify TCR-bearing cells that recognized the pathogenic AQP4 T cell epitopes. T cells from AQP4−/− mice selected an AQP4-specific TCR repertoire that was distinct from WT mice and exhibited clonal expansion. Collectively, these findings suggested that thymic negative selection may contribute to AQP4-specific T cell tolerance. Medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs), a cell type capable of expressing tissue-specific antigens (TSAs), including AQP4, are thought to direct negative selection by presenting those antigens in association with MHC molecules to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, eliminating high-affinity TCR-bearing self-antigen-specific T cells. Therefore, we created mice that were selectively deficient in mTEC expression of AQP4 and compared generation of AQP4-specific TCR-bearing (tetramer-positive, tet+) cells by AQP4 immunization in these mice, AQP4−/− mice and WT mice. The frequency of peripheral tet+ T cells generated in AQP4−/− mice was 10-fold higher than in WT mice. In comparison to WT mice, tet+ T cells were significantly elevated in mice selectively deficient in thymic AQP4 expression but not to the level observed in AQP4−/− mice. The autoimmune regulator, Aire and Fezf2, two transcription factors expressed by mTECs that direct negative T cell selection to many autoantigens, did not impact the frequency of tet+ T cells generated in comparison to WT mice. These findings suggest that thymic negative selection alone may not be the predominant mechanism of AQP4-specific T cell tolerance.

Expression of T cell-polarizing cytokines by pathogenic AQP4−/− and nonpathogenic WT AQP4-specific T cells was similar, suggesting that resistance to CNS autoimmunity in WT mice was not due to an intrinsic inability to generate proinflammatory AQP4-reactive T cells or expansion of regulatory AQP4-specific T cells (18, 19). Thus, we questioned whether another process contributed to tolerance to AQP4. Donor AQP4-reactive Th17 cells were tested for their capability to induce clinical and histologic disease in recipient WT mice, in mice deficient in both T and B cells, and in mice lacking either T cells or B cells only. Recipient WT mice and mice containing T cells, but not B cells, developed clinical disease and CNS inflammation but then recovered. In contrast, recipient mice deficient in both T and B cells, or mice lacking T cells only, developed persistent paralysis, suggesting that peripheral host T cells promoted recovery. Donor AQP4-specific T cells, like MOG-specific T cells, persisted in secondary lymphoid tissue and in the CNS of T cell-deficient mice. While donor AQP4-specific T cells were detected initially in recipient WT mice, there was a dramatic reduction during CNS disease and recovery, which was associated with an increased frequency of apoptotic cells among residual AQP4-reactive donor cells. By comparison, MOG-reactive T cells caused persistent paralysis in recipient WT mice and were detected in all compartments at each time evaluated. Our results indicate that peripheral T cell deletion has a prominent role in tolerance to AQP4, a member of the ubiquitous water channel family.

Results

Pathogenic AQP4 T Cell Epitopes Bind MHC II with High Affinity.

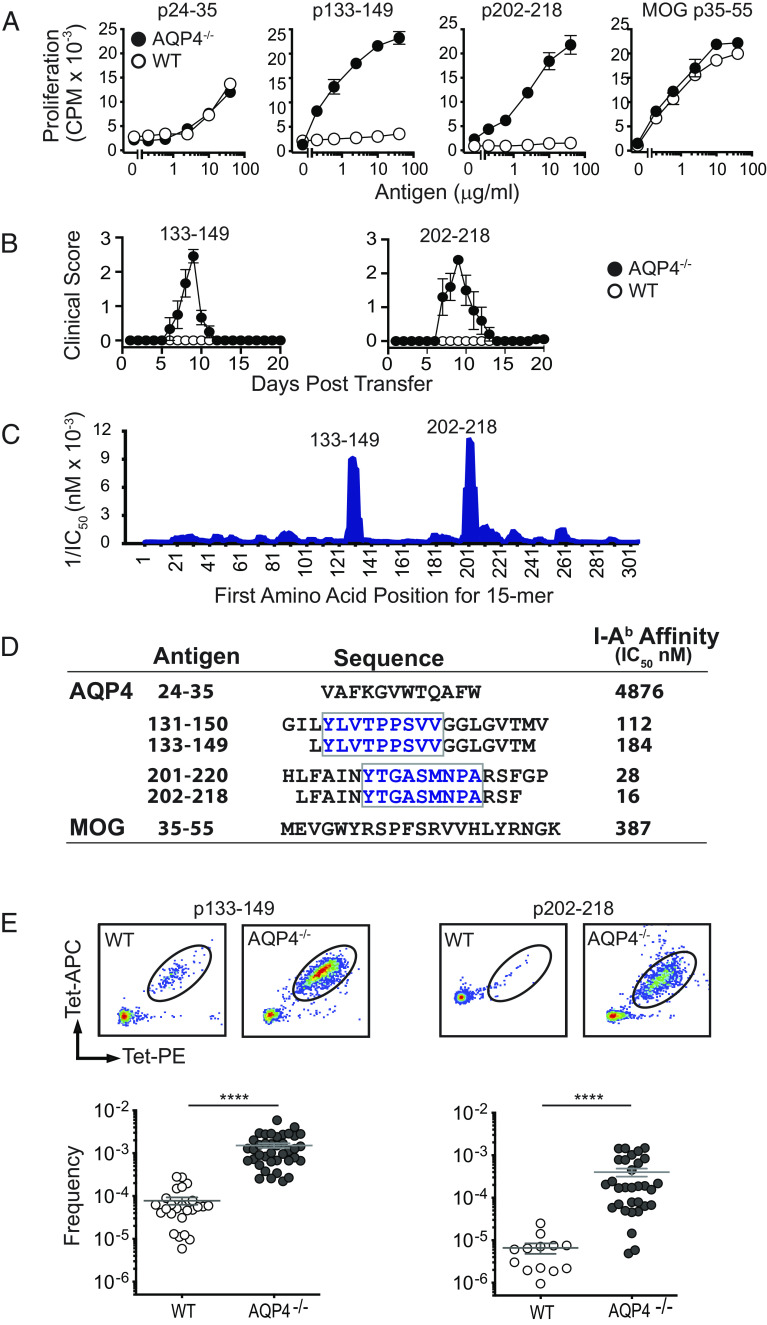

Pathogenic AQP4 T cell determinants located within amino acids 133–153 and 201–220 were identified when studying immune responses in AQP4−/− mice (17, 18). Peptides p133–149 and p202–218 induce robust proliferative responses in AQP4−/−, but not WT, mice (Fig. 2A), and Th17 cells specific for these AQP4 peptides are capable of inducing paralysis and CNS inflammation in WT mice (Fig. 2B). Discordance in proliferation between AQP4−/− and WT mice was not observed for nonpathogenic AQP4 T cell epitopes (e.g., AQP4 p24–35) (13) or encephalitogenic MOG p35–55.

Fig. 2.

Pathogenic AQP4 determinants bind I-Ab with high affinity and elicit proliferation of AQP4:I-Ab-specific TCR-bearing T cells in AQP4-deficient mice. (A) WT or AQP4−/− mice were immunized s.c. with peptides indicated. Peptide-specific proliferation of draining lymph node cells was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation (mean ± SEM, representative of five experiments). (B) Lymph node cells from AQP4 immunized WT or AQP4−/− mice were cultured for 3 d with cognate antigen under Th17 polarizing conditions. AQP4 p133–149- and p202–218-specific Th17 cells from AQP4−/− donors induce paralysis in WT recipient mice. (C) IEDB, an in silico method for predicting determinants within proteins that bind MHC alleles, was used to identify AQP4 amino acid sequences anticipated to bind I-Ab for recognition by AQP4-specific/I-Ab-restricted CD4+ T cells. 1/IC50 is plotted against the first amino acid for each overlapping AQP4 15 mer. Peaks correspond to increased predicted binding affinity. (D) Purified I-Ab molecules were tested biochemically for peptide binding affinity using a competitive binding assay between a radiolabeled high-affinity competitor peptide and unlabeled peptides (21). Lower IC50 values indicate higher binding affinity. Boxed amino acids designate the core binding regions. (E) Lymph node T cells isolated from WT or AQP4−/− mice immunized with AQP4 p133–149 or p202–218 were stained with I-Ab:p133–149 and I-Ab:p220–218 tetramers, bead-enriched, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Upper panels show representative tetramer staining of bead-enriched lymph node cell samples. Lower panels show frequency of tetramer-binding T cells among CD4+ T cells, calculated from enriched and unenriched fractions using counting beads for quantification. Each data point represents one mouse. ****P < 0.0001 (Mann–Whitney U test).

Both AQP4 p133–149 and p202–218 are predicted to bind MHC II (I-Ab) with high affinity according to the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) (Fig. 2C), an in silico method for predicting determinants within proteins that bind allele-specific MHC molecules for presentation to T cells (22). We have now examined AQP4 peptide affinity for I-Ab biochemically. I-Ab molecules that were purified by affinity chromatography were tested in a competitive binding assay between a radiolabeled high-affinity competitor peptide and unlabeled peptides (21). Indeed, peptides containing the two pathogenic AQP4 T cell determinants bound I-Ab with higher affinity than the nonpathogenic AQP4 p24–35 T cell epitope or MOG p35–55 (Fig. 2D). In fact, AQP4 p202–218 bound I-Ab with more than ten times greater affinity than MOG p35–55.

MHC II:peptide tetramers, I-Ab:AQP4 p133–149 and I-Ab:p202–218, were created in order to detect CD4+ T cells bearing TCRs specific for the two pathogenic AQP4 determinants. Analysis of primary lymph node CD4+ T cells from AQP4 peptide-immunized WT and AQP4-deficient mice identified a 10-fold higher frequency of proliferative tetramer-positive (tet+) T cells in AQP4-deficient mice (Fig. 2E). I-Ab:AQP4 p133–149 tet+-sorted T cells from p133–149-immunized AQP4−/− mice transferred CNS autoimmunity to WT mice, although it was possible to expand tet− pathogenic T cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Thus, tet+ status did not identify pathogenic T cells exclusively. Collectively, our observations that AQP4 p133–149 and p202–218 bound I-Ab avidly and that AQP4−/−, but not WT, T cells for these determinants transferred CNS autoimmune disease to WT recipient mice suggested that generation of the pathogenic AQP4-specific T cell repertoire is prevented by negative selection.

AQP4-Specific TCR Repertoire Selection in WT and AQP4−/− Mice Is Distinct.

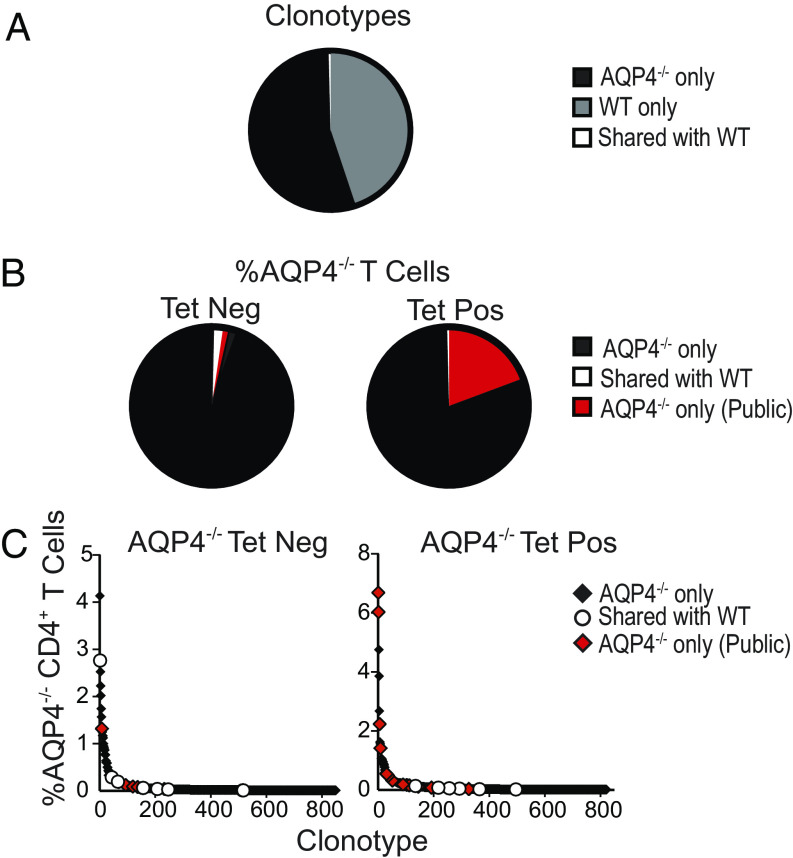

If loss of thymic negative selection permits expansion of pathogenic AQP4-specific T cells, one might predict that TCRs selected by AQP4-reactive T cells in AQP4-deficient and WT mice would differ. We evaluated this possibility by examining rearranged TCR α/β genes within individual AQP4-reactive T cells from AQP4 p133–149-primed AQP4-deficient and WT mice by scTCR-Seq using the 10X Genomics platform. Here, we focused on p133–149-specific T cells as those cells bound their corresponding tetramers more efficiently. Only a small fraction (0.3%) of AQP4-specific TCR α/β clonotypes examined were shared between WT and AQP4−/− mice (Fig. 3A). AQP4-specific tet+ T cells from AQP4−/− mice had minimal overlap between WT and AQP4-deficient T cells (Fig. 3B). The tet+ T cells from AQP4−/− mice contained many expanded TCR clonotypes that were shared amongst multiple AQP4−/− mice (“public” indicated in red) (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the AQP4-reactive tet− T cells contained very few public TCR sequences, where overlap was primarily with WT T cells. Although this sampling represents a small proportion of the entire TCR repertoire, our results indicate that thymic negative selection is one mechanism that restricts development of pathogenic AQP4-reactive T cells in WT mice.

Fig. 3.

AQP4-specific TCR repertoire selection differs in AQP4-deficient and WT mice. Draining lymph node cells from AQP4 p133–149-immunized AQP4−/− and WT mice were cultured with p133–149 for 10 d and then restimulated with irradiated splenic APC and p133–149 every 10 d for two stimulations. CD4+ T cells were isolated and subjected to scRNA-seq for TCR V(D)J α/β repertoire analysis (3,000 to 6,000 clonotypes/group/experiment). (A) The pie chart shows the number of individual clonotypes per 10,000 detected in AQP4−/− mice only (black, 54.8%), WT mice only (gray, 44.9%) and those that were common (white, 0.3%) to AQP4−/− and WT mice. (B) A higher frequency of tet+ (19.3%) than tet− (2.3%) TCR α/β clonotypes were shared (red, “public”) by separate AQP4−/− mice. Data represent a total of 16,000 tet+ and tet− clonotypes analyzed in two experiments (2 mice/group/experiment). (C) A majority of expanded AQP4− tet− TCR clonotypes and all amplified tet+ TCR α/β clonotypes analyzed were not detected among WT AQP4-specific TCR clonotypes. The tet+ AQP4− population contained several public TCR clonotypes. A total of 9,700 tet− T cells (3,500 clonotypes) and 6,300 tet+ T cells (1,033 clonotypes) are represented.

Absence of Thymic Negative Selection Alone Does Not Permit Expansion of AQP4-Reactive T cells.

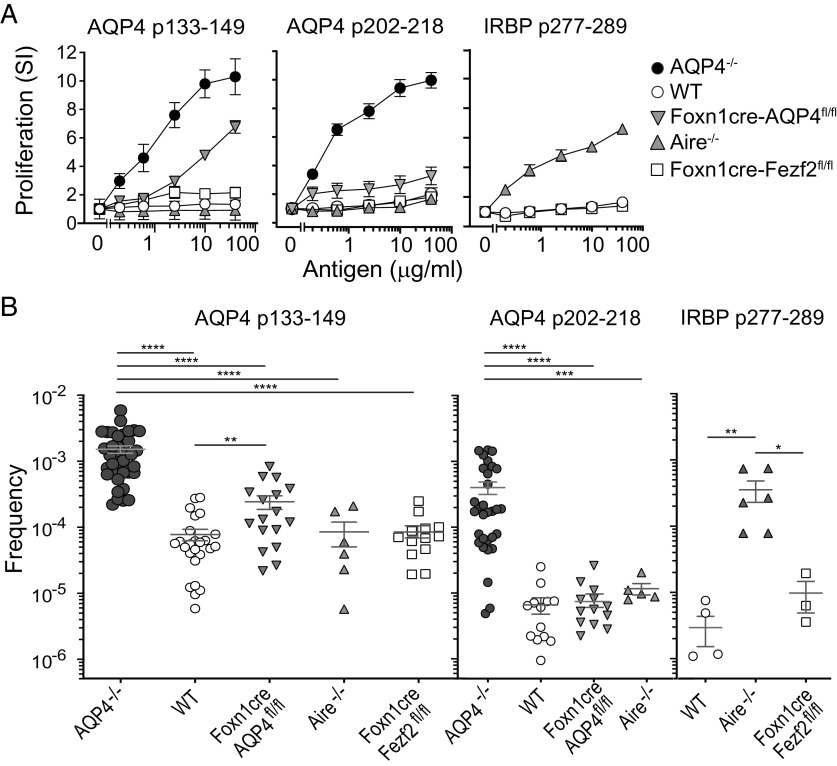

mTECs express peripheral TSAs for the purpose of presenting them and deleting self-antigen-reactive thymic T cells, a process known as negative selection (23). Aire and Fezf2 are two distinct transcription factors expressed by mTECs that control deletion of T cells reactive to a majority of TSAs (24, 25). Data suggest that mTEC AQP4 expression may be Aire-dependent (26) or Fezf2-dependent (25). To examine our hypothesis that thymic deletion constrains development of peripheral AQP4-reactive T cells, we created mice that were selectively deficient in mTEC AQP4 (Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl) expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). We compared priming to the pathogenic T cell epitopes in those mice with WT and AQP4−/− mice, as well as Aire−/− mice and mice selectively deficient in mTEC Fezf2 (Foxn1cre-Fezf2fl/fl) expression. AQP4 p133–149 induced robust proliferative T cell responses in AQP4−/− mice and also induced proliferation in Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl mice but not to the same level as in AQP4−/− mice (Fig. 4A). AQP4 p133–149 induced little or no proliferation in WT mice, Foxn1cre-Fezf2fl/fl mice, or Aire−/− mice. Like AQP4 p133–149, p202–218 induced strong proliferation in AQP4−/− mice but only marginal responses in Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl mice and no significant responses in WT or Aire−/− mice.

Fig. 4.

Negative selection of AQP4 p133–149-reactive T cells is bypassed partially in mice deficient in thymic AQP4 expression. (A) AQP4−/−, WT, Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl, Aire−/−, or Foxn1cre- Fezf2fl/fl mice were immunized s.c. with peptides indicated. Peptide-specific proliferation of draining lymph node cells was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation (mean ± SEM, representative of five experiments). Comparisons within the five experiments for p133–149 at 10 μg/mL: WT vs. AQP4−/− (P = 0.008), WT vs. Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl (P = 0.008). (B) Ten days after peptide immunization, CD4+ T cells from draining lymph nodes were analyzed for I-Ab:peptide tetramer binding by flow cytometry. Each data point represents the frequency (mean ± SEM) of CD4+ T cells bound to cognate antigen–tetramer in a single mouse. Comparisons were calculated by the Mann–Whitney U test (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05) Comparisons which did not reach statistical significance are not shown. For p133–149: WT vs. Aire−/− (P = 0.9), WT vs. Foxn1cre-Fezf2fl/fl (P = 0.3). For p202–218: WT vs. Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl (P = 0.3), WT vs. Aire−/− (P = 0.06).

The frequencies of AQP4 p133–149-specific and p202–218-specific CD4+ tet+ T cells in individual AQP4 p133–149- and p202–218-primed mice were examined with I-Ab:p133–149 and I-Ab:p202–218 tetramers, respectively (Fig. 4B). I-Ab:p133–149 tet+ T cells were significantly elevated in AQP4−/− mice in comparison to WT, Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl, Aire−/−, and Foxn1cre-Fezf2fl/fl mice, results that were compatible with the proliferative T cell responses in these mice. Similarly, I-Ab:p202–218 tet+ T cells were elevated in AQP4−/− mice in comparison to other strains. Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP), a self-antigen known to contain a T cell determinant, p277–289, which is Aire-dependent (27), was tested in parallel and, as anticipated, p277–289 immunization promoted expansion of CD4+ I-Ab:IRBP p277–289 tet+ CD4+ T cells in Aire−/− mice. Thus, Fezf2 and Aire do not participate in negative selection to these AQP4-specific T cell epitopes in WT mice.

While frequencies of I-Ab:p133–149 tet+ T cells in Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl mice were significantly lower than in AQP4−/− mice, their frequencies were significantly elevated in comparison to AQP4 p133–149-specific T cells in WT mice, which was consistent with proliferative responses to this determinant in these mice (Fig. 4A). These two observations, along with TCR repertoire analysis, indicate that thymic negative selection does influence formation of the T cell repertoire to AQP4 p133–149. Of particular interest, Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl mice were resistant to CNS autoimmunity by immunization with p133–149 (SI Appendix, Table S1). Our results clearly demonstrate that central tolerance alone does not restrain development of pathogenic AQP4-reactive T cells in WT mice.

Peripheral T Cell Deletion Restricts AQP4-Targeted CNS Autoimmune Disease.

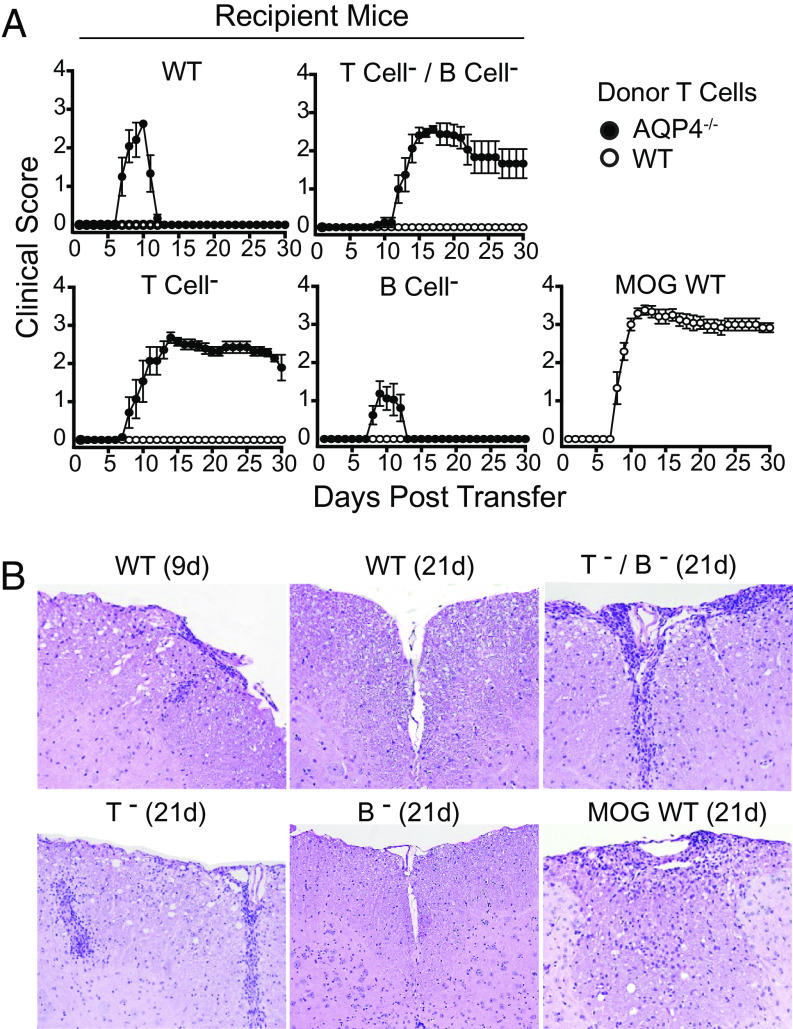

Previously, it was observed that pathogenic and nonpathogenic AQP4-specific T cells could not be distinguished based on potential differences in production of proinflammatory or regulatory cytokines. Therefore, we questioned whether another mechanism of peripheral tolerance prevented AQP4-targeted disease induction in WT mice. Pathogenic AQP4-specific p133–149-specific Th17 cells from AQP4−/− mice were transferred to WT, T and B cell–deficient (RAG1−/−), T cell–deficient (TCRα−/−), or B cell–deficient (JHT) mice. Recipient WT and JHT mice developed paralysis beginning around day 7 after transfer but then recovered completely 4 to 5 d later (Fig. 5A). CNS inflammation accompanied clinical disease (day 9) and was no longer evident after recovery (day 21) (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Table S2). In contrast, recipient RAG1−/− and TCRα−/− mice developed persistent paralysis and CNS inflammation similar to WT mice that received donor MOG p35–55-specific Th17 cells.

Fig. 5.

Pathogenic AQP4-specific Th17 cells induce sustained CNS autoimmune disease in T cell–deficient mice. (A) Th17-polarized AQP4 p133–149-specific T cells from AQP4−/− mice were transferred into WT, T cell– and B cell–deficient (T cell-/B cell-, RAG1−/−), T cell–deficient (T cell-, TCRα−/−) and B cell–deficient (B cell-, JHT) recipient mice then scored for clinical disease. Donor Th17-polarized MOG p35-55-specific T cells were transferred into WT recipient mice as a control. Results are representative of four experiments (n = 5 per group). (B) Recipient mice were evaluated for histologic evidence of meningeal and CNS parenchymal inflammation (H&E). Results are representative of two experiments (two to four mice/group/timepoint/experiment).

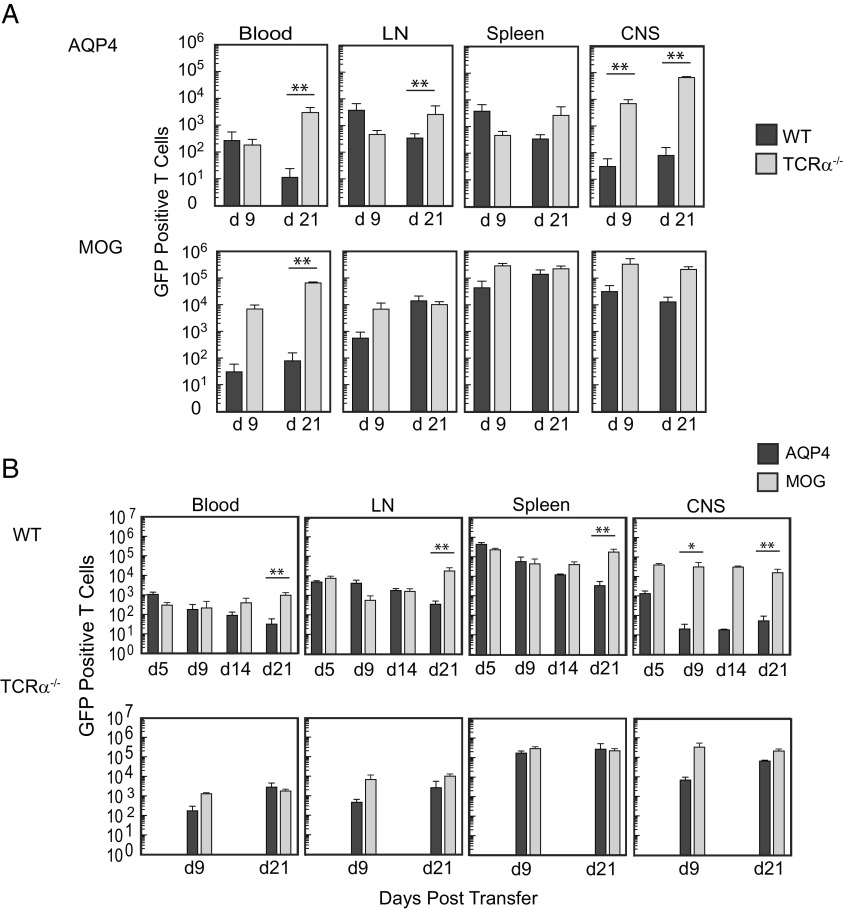

Our findings suggested that a peripheral T cell–dependent mechanism restricts AQP4-targeted CNS autoimmunity. In order to evaluate whether this process limited survival of AQP4-reactive T cells, we examined recovery of donor green fluorescent protein (GFP)+ pathogenic AQP4-specific T cells in TCRα−/− and WT mice. There was a 2 to 3 log-fold reduction in recovery of donor T cells in WT recipient mice in comparison compared to TCRα−/− mice (Fig. 6A). Donor GFP+ MOG-specific T cells were evaluated in parallel. Both donor AQP4-specific and MOG-specific T cells were detected in the CNS and secondary lymphoid tissues at multiple timepoints in TCRα−/− mice that developed persistent CNS autoimmune disease. Donor MOG-specific T cells were also detected in the CNS and secondary lymphoid tissues of WT recipient mice at all time points tested (Fig. 6B). In comparison, there was a 2 to 3 log-fold relative reduction in the number of donor AQP4-specific T cells in the CNS of WT mice during acute disease and recovery and a similar reduction of AQP4-specific donor T cells in secondary lymphoid tissues during recovery. Thus, in contrast to MOG-specific T cells, AQP4-specific T cells do not persist in WT hosts.

Fig. 6.

Pathogenic AQP4-specific Th17 cells persist in T cell–deficient mice but not in WT mice. (A) Donor Th17-polarized AQP4 p133–149-specific and MOG p35–55-specific primary T cells from actin-GFP/AQP4−/− mice were transferred into WT or T cell–deficient (TCRα−/−) mice and then examined for recovery in 100 μL blood, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes combined (LN), the spleen, and the CNS at 9 and 21 d by flow cytometry. Cells were gated on single, viable GFP+CD4 T cells. Counting beads were used for quantification. (B) AQP4 p133–149 or MOG p35–55-primed Th17-polarized LN cells from AQP4−/− actin-GFP+ mice were transferred into WT or TCRα−/− mice and then examined by flow cytometry at the indicated timepoints. Data shown for A and B represent a composite from three experiments [n = 6 per condition (mean ± SEM)]. Statistical comparison of surviving numbers of GFP+ donor cells was performed by the Mann–Whitney U test (**P < 0.01).

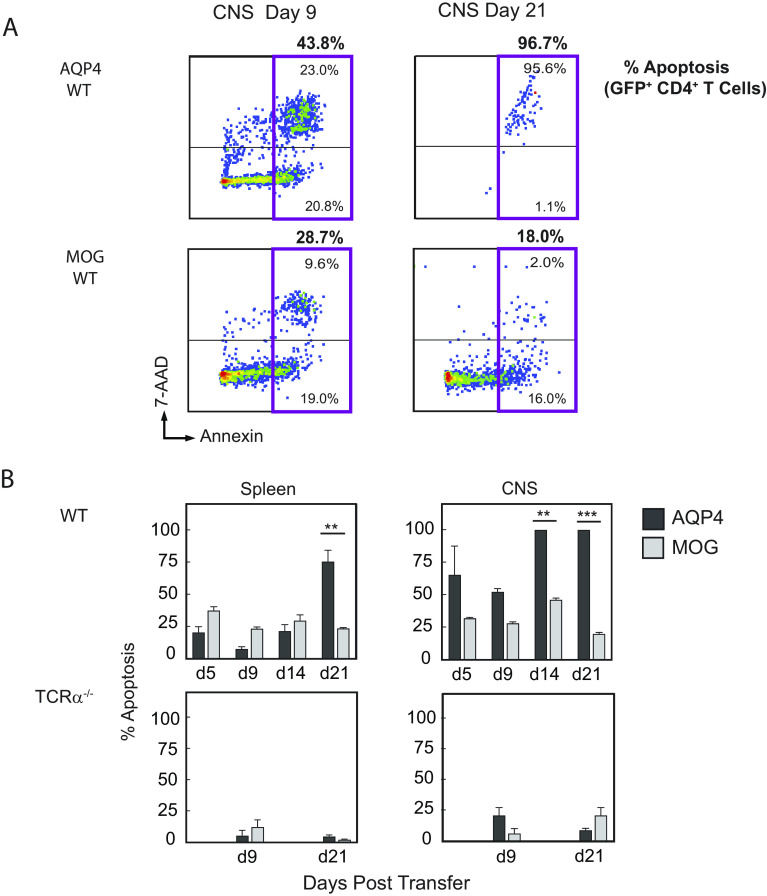

Annexin V staining was performed to determine whether loss of donor AQP4-specific T cells in WT mice reflected increased apoptotic cell death in vivo (Fig. 7A). In contrast to donor MOG-specific T cells, there was a marked increased frequency of apoptotic AQP4-specific T cells in the CNS during disease and after recovery (Fig. 7B). The frequency of Annexin V+ donor MOG-specific and AQP4-specific T cells in recipient TCRα−/− mice that developed persistent disease was low in both the spleen and the CNS and did not differ between groups. These findings indicate that AQP4-reactive T cells are more susceptible to peripheral deletion.

Fig. 7.

Reduced survival of pathogenic AQP4-specific Th17 cells WT mice is associated with apoptosis. (A) GFP+ T cells were examined for viability and apoptosis by staining with Annexin V and 7-AAD followed by flow cytometry (28, 29)). Viable cells are negative for Annexin V and 7-AAD. Apoptotic cells are Annexin V positive, which are further distinguished by early stage (7-AAD negative) and late stage (7-AAD positive). A representative flow staining pattern is shown. The total apoptotic donor populations for CD4+GFP+ AQP4-specific and MOG-specific T cells are shown (magenta box) with the percentages indicated above. Percentages of late-stage and total apoptotic donor GFP+AQP4-specific T cells were higher than donor GFP+MOG-specific T cells in recipient WT mice at day 9 and day 21. (B) Apoptotic GFP+CD4+ T cells from recipient mice were examined in the spleen and CNS, and counting beads were used for quantification. The data shown represent a composite from three experiments, n = 6 per condition (mean ± SEM). Statistical analysis for comparison of surviving numbers of GFP+ donor cells was performed using a t test with the Holm–Sidak correction for multiple comparisons (**P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001).

Discussion

NMO and MOG antibody–associated disease (MOGAD) are two distinct CNS autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating diseases (30). Antibodies specific for APQ4 in NMO or MOG in MOGAD are IgG1, a T cell–dependent antibody isotype. The importance of humoral autoimmunity in NMO is underscored by the remarkable success of the complement inhibitor, eculizumab (31). However, only limited data support a pathogenic role for MOG-specific antibodies in MOGAD (32, 33). MOG was identified as an autoantigen in EAE (34) more than a decade before anti-MOG antibodies were identified in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) (35) and nearly two decades before they were associated with optic neuritis and transverse myelitis (36, 37). Important lessons from MOG EAE can be applied to MOGAD (38–42). MOG EAE is a T cell–mediated disease, and while anti-MOG antibodies can exacerbate EAE and CNS demyelination, those antibodies are neither necessary nor sufficient to cause EAE in the absence of MOG-specific T cells (32, 34, 41). Similarly, AQP4-specific antibodies are not pathogenic in the absence of CNS inflammation (8, 9). As for MOGAD, identifying mechanisms regulating T cell recognition of AQP4 in a model system may provide important conceptual advances for understanding the role of AQP4-specific T cells in NMO.

Recognition that WT mice were resistant to AQP4-induced CNS autoimmune disease and that pathogenic AQP4-specific T cells could be generated in AQP4−/− but not in WT mice created a conundrum. Are AQP4-specific T cells restricted by central or peripheral tolerance? In this report, our findings that the AQP4-specific TCR repertoire selected in AQP4−/− and WT mice were not the same and that there was a significant increase in AQP4 p133–149 tet+ T cells in thymic AQP4-deficient mice in comparison to WT mice supported operation of a central tolerance mechanism. However, the numbers of p133–149 tet+ T cells in thymic AQP4-deficient mice were significantly lower than in AQP4−/− mice, and thymic AQP4 deficiency did not permit significant restoration of AQP4 p202–218 tet+ T cells. Thus, a central mechanism alone did not shape the peripheral repertoire of AQP4-specific T cells. Demonstration that CNS autoimmunity in WT mice was self-limited and associated with reduced survival of AQP4-reactive T cells indicates that there is a dominant peripheral deletional mechanism distinct from MOG-targeted disease, which provides an additional layer of protection from AQP4 T cell autoimmunity.

Our observations that AQP4-targeted CNS autoimmunity was constrained by peripheral deletion of AQP4-reactive T cells and that this process was T cell–dependent are unique. However, peripheral apoptotic (e.g., FasL-induced) T cell deletion as may occur by repetitive stimulation with cognate antigen is well recognized (43, 44). We have not yet identified which T cells may be responsible for apoptosis of pathogenic AQP4-reactive T cells. Recent studies have demonstrated that self-peptide-specific CD8+ T cells (45), including the Kir+CD8+ subset in humans and Ly49+CD8+ in mice, can suppress CD4+ antigen-specific T cell autoimmune responses (46, 47). Thus, in future studies, we will investigate whether CD8+ T cells or another individual T cell subset may be responsible for deletion of pathogenic AQP4-reactive T cells.

IEDB, which was used as a resource for the initial characterization of the two pathogenic AQP4 T cell determinants, predicted that they bind MHC II I-Ab molecules with high affinity (18). Those predictions were validated biochemically in this report. It is important to recognize that the binary interaction of peptide with MHC II, a prerequisite for antigen presentation, does not necessarily translate to high avidity TCR engagement of MHC II:peptide complexes. We did not directly assess avidity of AQP4-specific TCRs for I-Ab:AQP4 peptide, although it has been observed that high-affinity self-antigen-reactive T cells are preferentially detected by MHC II:peptide tetramers (48). However, we have identified AQP4 p133–149-specific tet+ T cells that escaped negative selection in AQP4−/− and Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl mice but not in WT mice. Thus, it should now be possible to determine whether AQP4-specific T cells subject to negative selection in the normal host express TCRs with high affinity for I-Ab:AQP4 p133–149 (49).

One potential limitation of this study is that we examined only a finite number of T cells by scTCR-Seq, yet the naive repertoire of potential TCR α/β clonotypes is immense (50). However, our goal was to focus on AQP4-specific T cells that were expanded by AQP4 priming in vivo. Further, our use of I-Ab:AQP4 tetramers in combination with scTCR-Seq permitted us to capture a large proportion of the polyclonal tet+ T cells. Although it is recognized that AQP4 is expressed most abundantly in the CNS, kidney, muscle, and lung, it is not clear whether AQP4 is expressed in peripheral T cells. In previous work, we did not detect AQP4 protein or mRNA in WT murine peripheral T cells (51). However, one group reported that T cell AQP4 deficiency reduced TCR-mediated signaling, although they did not detect any change in thymocyte subsets (52). It should be recognized that it was the AQP4-specific T cells from AQP4−/− but not WT mice that induced CNS autoimmune disease. Donor T cells from AQP4−/− and WT mice did not differ in production of proinflammatory-polarizing and anti-inflammatory cytokines or frequency of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (18). Last, both donor AQP4-reactive and MOG-reactive T cells used in studies evaluating T cell survival in WT and TCRα−/− mice were isolated from AQP4−/− mice. Thus, any potential change in TCR signaling would have been common to donor AQP4-specific and MOG-specific T cells.

AQP4 is expressed in multiple tissues, yet why is tissue damage in NMO considered primarily restricted to the CNS? Antibodies in NMO target membrane tetramers of AQP4 assembled into orthogonal arrays of particles (OAPs) that are expressed abundantly in astrocyte end-foot processes (53–55). OAPs provide an ideal substrate for binding of AQP4-specific antibodies, permitting cross-linking via C1q and activation of complement (56). NMO is a humoral OAP autoimmune disease. In contrast, AQP4-specific T cells recognize linear fragments of AQP4 in association with MHC molecules on APC, and not conformational determinants of AQP4 or OAPs. While AQP4-specific antibodies target astrocyte OAPs and account for the tissue specificity in NMO, T cells may be exposed to AQP4 in several tissues. We hypothesize that peripheral AQP4-specific T cell deletion provides a layer of protection against formation of AQP4-specific antibodies by B cells and the development of NMO. High-affinity MHC peptide binding may not only promote presentation but also deletion. It may not be coincidence that the encephalitogenic AQP4 p202–218, which binds MHC II with the highest affinity among peptides examined in this report, is remarkably homologous to amino acid sequences in aquaporins 1, 2, 5, and 6 (Table 1), aquaporins that are expressed ubiquitously. Thus, via “self-antigen mimicry,” peripheral T cell deletion of AQP4-reactive T cells may provide tolerance to aquaporins, collectively. Conversely, a break in tolerance that permits T cell activation to an AQP4 epitope in one tissue may promote a proinflammatory response to AQP4, or a closely related sequence of another aquaporin, in a different organ. Both AQP4 and AQP5 are expressed in salivary glands (5). Thus, one can speculate that the Sjögren’s syndrome–like salivary gland inflammation that is often associated with seropositive NMO (57–61) may be representative of an “autoimmune aquaporinopathy” (30), and sometimes even serve as a forme fruste forewarning the onset of NMO (62).

Table 1.

Homology of pathogenic AQP4 T cell epitopes with other aquaporins

| Identity‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Position* | Sequence*,† | Sequence (%) | Core (%) | Organs§ |

| AQP4 | 133–149 | LYLVTPPSVVGGLGVT | CNS, kidney, salivary gland, heart, GI tract, muscle, and lung | ||

| AQP6 | 115–131 | LYGVTPGGIRETLGVN | 50 | 44 | Brain and kidney |

| AQP4 | 202–218 | LFAINYTGASMNPARSF | |||

| AQP1 | 181–197 | LLAIDYTGCSINPARSF | 77 | 78 | CNS, kidney, heart, lung, GI tract, ovary, testis, liver, muscle, and spleen |

| AQP4 | 202–218 | LFAINYTGASMNPARSF | |||

| AQP2 | 173–189 | LLGIYFTGCSMNPARSL | 65 | 78 | Kidney, ear, and ductus deferens |

| AQP4 | 202–218 | LFAINYTGASMNPARSF | |||

| AQP5 | 174–190 | LVGIYFTGCSMNPARSF | 71 | 78 | Salivary gland, eye, trachea, lung, GI tract, ovary, and kidney |

| AQP4 | 202–218 | LFAINYTGASMNPARSF | |||

| AQP6 | 182–198 | LIGIYFTGCSMNPARSF | 71 | 78 | Brain and kidney |

*Each mouse aquaporin was aligned individually to AQP4 using the Clustal Omega Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool (Clustal Omega < Multiple Sequence Alignment < EMBL-EBI), and homologous regions were identified.

†Identical residues are identified in bolded black, and core binding regions are underlined.

‡The % homology for the sequence listed and the binding region is listed.

§Ref. (5).

We have not created NMO in mice. However, we have provided a foundation to evaluate the regulation of AQP4-specific T cells in CNS autoimmunity, which may advance our understanding of aquaporin-specific T cells in NMO and in other autoimmune diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6 (H-2b), mice, B cell–deficient (JHT), T cell–deficient (TCRα−/−), T and B cell–deficient (RAG1−/−), and Foxn1cre mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). C57BL/6 AQP4−/− mice were provided by A. Verkman (UCSF), AQP4fl/fl mice (63) were a gift from Ole Petter Ottersen (University of Oslo), Fezf2fl/fl mice (64) were from Nenad Sestan (Yale University), and Aire−/− were provided by M. Anderson (UCSF). Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl and Foxn1cre-Fezf2fl/fl mice were generated by breeding female Foxn1cre mice with male AQP4fl/fl or Fezf2fl/fl mice, respectively. Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at UCSF Laboratory Animal Research Center. All studies were approved by the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Ethics Statement.

The experimental protocol adheres to guidelines for animal use in research set by the NIH and was approved by the Office of Research, UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC Approval).

Antigens.

AQP4 peptides p133–149, p202–218, p24–35, MOG p35–55, and IRBP p277–289 were synthesized by Genemed Synthesis.

I-Ab Affinity Assay.

Purification of MHC class II I-Ab molecules by affinity chromatography and the performance of assays based on the inhibition of binding of a high-affinity radiolabeled peptide to quantitatively measure peptide binding were performed as described (21). Lower IC50 values indicate higher binding affinity. Excellent binders have affinities less than 100 nM, and good binders have affinities less than 1,000 nM.

Proliferation Assays.

Mice were immunized subcutaneously (s.c.) with 100 μg of AQP4, MOG, or IRBP peptide in CFA containing 400 μg M. tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco Laboratories). Lymph nodes were harvested on days 10 to 12 and cultured at 2 × 105/well with various concentrations of peptide in triplicate wells for 72 h. One μci/well of 3H-thymidine was added 18 h prior to cell harvest, and data are presented as counts per minute (CPM). The stimulation index was calculated by dividing CPM in wells with Ag by CPM in wells with no antigen controls of each assay test group.

Flow Cytometry.

For analysis of tetramer binding, AQP4 p133–149, p202–218, IRBP p277–289, and hCLIP p87–101 IAb tetramers conjugated to PE or APC were provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Tetramer Core Facility at Emory University. Lymphocytes were coincubated with 1 μg/mL tetramer conjugated to PE or APC for 2 h at room temperature, washed, and enriched using anti-PE magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi) over a magnetic column. Binding to hCLIP tetramer was used as a negative control. Dead cells were excluded using the Live/Dead fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen), lineage-negative cells were excluded using antibodies to CD11b (M1/70), B220 (RA3-6B2), and CD8 (53–6.7), and positive cells were selected using antibodies to CD3 (145-2C11) and CD4 (RM4.5). 123count eBeads (Invitrogen) were used with unenriched and enriched samples for quantification of the frequency of tet+ CD4+ T cells (total number of tet+ CD4+ T cells divided by total CD4+ T cells per mouse). For figures showing tetramer staining, flow cytometry of the enriched cells is shown. For analysis of GFP+ T cells, mice were perfused with PBS, and the CNS was dissected, minced, digested with collagenase and DNase I (Roche), and isolated over a Ficoll gradient as described previously (41). Live CD4+ cells were analyzed with a viability stain (near-IR) and antibodies to CD11b, B220, CD8, and CD4. Apoptosis was analyzed separately using the same antibody staining, followed by Annexin V and 7-AAD staining in Annexin V binding buffer (BioLegend) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were quantified using 123count eBeads.

Single-Cell TCR Sequencing.

AQP4−/− and WT mice were immunized with AQP4 p133–149. T cells were harvested from draining lymph nodes and cultured with cognate antigen, receiving fresh antigen and irradiated splenocytes every 10 d for two stimulations. CD4+ p133–149-specific AQP4−/− T cells were sorted into tetramer positive or negative cells by flow cytometry. A single-cell library of the T-cell V(D)J regions targeting 10,000 cells from each group was constructed using the 10× Genomics Chromium Single Cell 5′ Library and Gel Bead Kit and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq. Data shown represent two experiments.

Bioinformatic Analysis.

All datasets were analyzed using the Cell Ranger (v3.1.0) variable diversity joining (VDJ) function, which aligned reads to the GRCm38 Alts Ensembl reference (v3.1.0) using STAR (v2.5.1). Reads present in more than one sample that shared the same cell barcode and UMI were omitted using the SingleCellVDJdecontamination computational pipeline (https://github.com/UCSF-Wilson-Lab/SingleCellVDJdecontamination). TCR α and β chain contigs per cell, outputted from CellRanger, were further analyzed using custom bioinformatic programming scripts written in R and perl. For each cell, only one TCR α and one TCR β chain were kept by filtering for contigs assembled with the largest number of UMIs and raw reads. Cells were assigned to the same TCR clonotype if they share identical V genes, J genes, and CDR3 amino acid sequences for both the TCR α and β chains. Cells with sequences that contained only a single chain or more than one TCR α and β chain were omitted, leaving 3,000 to 6,000 T cells per group. A clonotype was defined as clonally expanded if contained within two or more T cells (65, 66). The datasets are available as an NCBI BioProject, Accession PRJNA989238, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/989238) (67).

CNS Autoimmune Disease Induction and Analysis.

For adoptive induction of CNS disease with primary lymphocytes, mice were immunized s.c. with 100 µg AQP4 or MOG peptides in CFA containing 400 µg Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco Laboratories). After 10 to 12 d, lymph node cells were cultured with 15 μg/mL antigen for 3 d with 20 ng/mL IL-23 and 10 ng/mL IL-6, under Th17 polarizing conditions. A total of 2 × 107 cells were injected i.v. into naïve recipients, which then received 200 ng B. pertussis toxin (Ptx) (List Biological) i.p. on days 0 and 2. Clinical scores: 0 = no disease, 1 = tail tone loss, 2 = impaired righting, 3 = severe paraparesis or paraplegia, 4 = quadraparesis, and 5 = moribund or death.

For induction of CNS disease by I-Ab:AQP4 tet-sorted cells targeted cells, primary lymph node cells from AQP4−/− or WT mice were restimulated with 15 μg/mL antigen and irradiated splenocytes every 10 d. Percent tetramer binding was monitored by flow cytometry. In preparation for adoptive transfer, cells were washed and cultured with 1:10 T cell-to-irradiated splenocytes under polarizing conditions for 3 d. CD4+ cells were negatively sorted using magnetic beads (Miltenyi). 5 × 106 were transferred to TCRα−/− recipients. Two hundred nanograms of Ptx was given on days 0 and 2.

Isolation of TECs.

Thymi from 6-wk-old AQP4−/−, WT, and Foxn1cre-AQP4fl/fl mice were isolated, digested with 50 μg/mL liberase-TM (Roche) and 24 U/mL DNaseI (Sigma), stained with anti-CD45, anti-EpCAM, anti-Ly5.1, and anti-I-Ab, and separated by FACS cell sorting into mTEChi, mTEClo, and cTEC cells. The mRNA was purified (Qiagen) and tested for AQP4 and GAPDH mRNA expression using ddPCR (Bio-Rad) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histopathology.

Brain, spinal cord, optic nerve, kidney, and muscle tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Meningeal and parenchymal inflammatory lesions and areas of demyelination were assessed in a blinded manner as described (41).

Statistical Analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistics for the frequency of T cell binding to tetramer and for the recovery of GFP+ T cells after adoptive transfer were calculated using the Mann–Whitney nonparametric T test. Statistics for the frequency of apoptotic cells in recovered tissues used a t test with the Holm–Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. P values are designated as follows: *P < 0.5, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Patricia A. Nelson and Akash Virupakshaiah for helpful discussion and critical review of the manuscript. Support was provided by grants from the NIH 1 R01 AI131624-01A1 (S.S.Z.), NIH K08 NS107619 (J.J.S.), National Multiple Sclerosis Society FAN-2107-38301 (C.E.M.), NMSS TA-1903-33713 (J.J.S.), Race to Erase MS (S.S.Z.), Westridge Foundation (M.R.W.), NIH 1 R01-NS095435 (A.S.), and the Weill Institute of Neurosciences (S.S.Z.).

Author contributions

S.A.S., J.J.S., and S.S.Z. designed research; S.A.S., Z.M., R.D., J.S., J.J.S., and S.S.Z. performed research; Z.M., C.E.M., A.S.V., O.P.O., and M.S.A. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; S.A.S., Z.M., C.E.M., R.D., C.M.S., R.A.S., J.S., A.S., L.S., M.R.W., J.J.S., and S.S.Z. analyzed data; and S.A.S., C.M.S., L.S., J.J.S., and S.S.Z. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Reviewers: H.C., Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; and A.S., Immunology Kymera Therapeurtics.

Contributor Information

Lawrence Steinman, Email: steinman@stanford.edu.

Scott S. Zamvil, Email: zamvil@ucsf.neuroimmunol.org.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. The data have been deposited on 29-Jun-2023 with links to BioProject accession number PRJNA989238 in the NCBI BioProject database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/989238) (67).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Agre P., et al. , Aquaporin water channels–from atomic structure to clinical medicine. J. Physiol. 542, 3–16 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zekeridou A., Lennon V. A., Aquaporin-4 autoimmunity. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2, e110 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen S., et al. , Specialized membrane domains for water transport in glial cells: High-resolution immunogold cytochemistry of aquaporin-4 in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 17, 171–180 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magni F., et al. , Proteomic knowledge of human aquaporins. Proteomics 6, 5637–5649 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azad A. K., et al. , Human aquaporins: Functional diversity and potential roles in infectious and non-infectious diseases. Front. Genet. 12, 654865 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucchinetti C. F., et al. , The pathology of an autoimmune astrocytopathy: Lessons learned from neuromyelitis optica. Brain Pathol. 24, 83–97 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurieva R. I., Chung Y., Understanding the development and function of T follicular helper cells. Cell Mol. Immunol. 7, 190–197 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett J. L., et al. , Intrathecal pathogenic anti-aquaporin-4 antibodies in early neuromyelitis optica. Ann. Neurol. 66, 617–629 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradl M., et al. , Neuromyelitis optica: Pathogenicity of patient immunoglobulin in vivo. Ann. Neurol. 66, 630–643 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brum D. G., et al. , HLA-DRB association in neuromyelitis optica is different from that observed in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 16, 21–29 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varrin-Doyer M., et al. , Aquaporin 4-specific T cells in neuromyelitis optica exhibit a Th17 bias and recognize Clostridium ABC transporter. Ann. Neurol. 72, 53–64 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaknin-Dembinsky A., et al. , T-cell reactivity against AQP4 in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 79, 945–946 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson P. A., et al. , Immunodominant T cell determinants of aquaporin-4, the autoantigen associated with neuromyelitis optica. PLoS One 5, e15050 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalluri S. R., et al. , Functional characterization of aquaporin-4 specific T cells: Towards a model for neuromyelitis optica. PLoS One 6, e16083 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeka B., et al. , Highly encephalitogenic aquaporin 4-specific T cells and NMO-IgG jointly orchestrate lesion location and tissue damage in the CNS. Acta Neuropathol. 130, 783–798 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pohl M., et al. , Pathogenic T cell responses against aquaporin 4. Acta Neuropathol. 122, 21–34 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones M. V., Huang H., Calabresi P. A., Levy M., Pathogenic aquaporin-4 reactive T cells are sufficient to induce mouse model of neuromyelitis optica. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 3, 28 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sagan S. A., et al. , Tolerance checkpoint bypass permits emergence of pathogenic T cells to neuromyelitis optica autoantigen aquaporin-4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 14781–14786 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogel A. L., et al. , Deletional tolerance prevents AQP4-directed autoimmunity in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 47, 458–469 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sagan S. A., et al. , Induction of paralysis and visual system injury in mice by T cells specific for neuromyelitis optica autoantigen aquaporin-4. J. Vis. Exp., 56185 (2017), 10.3791/56185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Sidney J., Measurement of MHC/peptide interactions by gel filtration or monoclonal antibody capture. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 18, Unit 18.3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendes M., et al. , IEDB-3D 2.0: Structural data analysis within the Immune Epitope Database. Protein Sci. 32, e4605 (2023), 10.1002/pro.4605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein L., Kyewski B., Allen P. M., Hogquist K. A., Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: What thymocytes see (and don’t see). Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 377–391 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson M. S., Su M. A., AIRE expands: New roles in immune tolerance and beyond. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 247–258 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takaba H., et al. , Fezf2 orchestrates a thymic program of self-antigen expression for immune tolerance. Cell 163, 975–987 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson M. S., et al. , Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science 298, 1395–1401 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taniguchi R. T., et al. , Detection of an autoreactive T-cell population within the polyclonal repertoire that undergoes distinct autoimmune regulator (Aire)-mediated selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7847–7852 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmermann M., Meyer N., Annexin V/7-AAD staining in keratinocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. 740, 57–63 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Telford W. G., Multiparametric analysis of apoptosis by flow cytometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 1678, 167–202 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zamvil S. S., Slavin A. J., Does MOG Ig-positive AQP4-seronegative opticospinal inflammatory disease justify a diagnosis of NMO spectrum disorder? Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2, e62 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pittock S. J., et al. , Eculizumab in aquaporin-4-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 614–625 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spadaro M., et al. , Pathogenicity of human antibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Ann. Neurol. 84, 315–328 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabatino J. J. Jr., Probstel A. K., Zamvil S. S., B cells in autoimmune and neurodegenerative central nervous system diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 728–745 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendel I., Kerlero de Rosbo N., Ben-Nun A., A myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide induces typical chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in H-2b mice: Fine specificity and T cell receptor V beta expression of encephalitogenic T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 25, 1951–1959 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Connor K. C., et al. , Self-antigen tetramers discriminate between myelin autoantibodies to native or denatured protein. Nat. Med. 13, 211–217 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato D. K., et al. , Distinction between MOG antibody-positive and AQP4 antibody-positive NMO spectrum disorders. Neurology 82, 474–481 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitley J., et al. , Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders with aquaporin-4 and myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies: A comparative study. JAMA Neurol. 71, 276–283 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slavin A. J., et al. , Requirement for endocytic antigen processing and influence of invariant chain and H-2M deficiencies in CNS autoimmunity. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1133–1139 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bettelli E., Baeten D., Jager A., Sobel R. A., Kuchroo V. K., Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T and B cells cooperate to induce a Devic-like disease in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2393–2402 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krishnamoorthy G., Lassmann H., Wekerle H., Holz A., Spontaneous opticospinal encephalomyelitis in a double-transgenic mouse model of autoimmune T cell/B cell cooperation. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2385–2392 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molnarfi N., et al. , MHC class II-dependent B cell APC function is required for induction of CNS autoimmunity independent of myelin-specific antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 210, 2921–2937 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shetty A., et al. , Immunodominant T-cell epitopes of MOG reside in its transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains in EAE. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 1, e22 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xing Y., Hogquist K. A., T-cell tolerance: Central and peripheral. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a006957 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ElTanbouly M. A., Noelle R. J., Rethinking peripheral T cell tolerance: Checkpoints across a T cell’s journey. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 257–267 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu W., et al. , Clonal deletion prunes but does not eliminate self-specific alphabeta CD8(+) T lymphocytes. Immunity 42, 929–941 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saligrama N., et al. , Opposing T cell responses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nature 572, 481–487 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li J., et al. , KIR(+)CD8(+) T cells suppress pathogenic T cells and are active in autoimmune diseases and COVID-19. Science 376, eabi9591 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sabatino J. J. Jr., Huang J., Zhu C., Evavold B. D., High prevalence of low affinity peptide-MHC II tetramer-negative effectors during polyclonal CD4+ T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 208, 81–90 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nyberg W. A., et al. , An evolved AAV variant enables efficient genetic engineering of murine T cells. Cell 186, 446–460.e19 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkins M. K., Chu H. H., McLachlan J. B., Moon J. J., On the composition of the preimmune repertoire of T cells specific for Peptide-major histocompatibility complex ligands. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 275–294 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li L., Zhang H., Varrin-Doyer M., Zamvil S. S., Verkman A. S., Proinflammatory role of aquaporin-4 in autoimmune neuroinflammation. FASEB J. 25, 1556–1566 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicosia M., et al. , Water channel aquaporin 4 is required for T cell receptor mediated lymphocyte activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 113, 544–554 (2023), 10.1093/jleuko/qiad010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rash J. E., Yasumura T., Hudson C. S., Agre P., Nielsen S., Direct immunogold labeling of aquaporin-4 in square arrays of astrocyte and ependymocyte plasma membranes in rat brain and spinal cord. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 11981–11986 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verkman A. S., Ratelade J., Rossi A., Zhang H., Tradtrantip L., Aquaporin-4: Orthogonal array assembly, CNS functions, and role in neuromyelitis optica. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 32, 702–710 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palazzo C., et al. , AQP4ex is crucial for the anchoring of AQP4 at the astrocyte end-feet and for neuromyelitis optica antibody binding. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 7, 51 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soltys J., et al. , Membrane assembly of aquaporin-4 autoantibodies regulates classical complement activation in neuromyelitis optica. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 2000–2013 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Javed A., et al. , Minor salivary gland inflammation in Devic’s disease and longitudinally extensive myelitis. Mult. Scler. 14, 809–814 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pittock S. J., et al. , Neuromyelitis optica and non organ-specific autoimmunity. Arch Neurol. 65, 78–83 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kahlenberg J. M., Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder as an initial presentation of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 40, 343–348 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim S. M., et al. , Sjogren’s syndrome myelopathy: Spinal cord involvement in Sjogren’s syndrome might be a manifestation of neuromyelitis optica. Mult. Scler. 15, 1062–1068 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jarius S., et al. , Frequency and syndrome specificity of antibodies to aquaporin-4 in neurological patients with rheumatic disorders. Mult. Scler. 17, 1067–1073 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jayarangaiah A., Sehgal R., Epperla N., Sjogren’s syndrome and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD)–A case report and review of literature. BMC Neurol. 14, 200 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haj-Yasein N. N., et al. , Glial-conditional deletion of aquaporin-4 (Aqp4) reduces blood-brain water uptake and confers barrier function on perivascular astrocyte endfeet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17815–17820 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han W., et al. , TBR1 directly represses Fezf2 to control the laminar origin and development of the corticospinal tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3041–3046 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vander Heiden J. A., et al. , pRESTO: A toolkit for processing high-throughput sequencing raw reads of lymphocyte receptor repertoires. Bioinformatics 30, 1930–1932 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nouri N., Kleinstein S. H., A spectral clustering-based method for identifying clones from high-throughput B cell repertoire sequencing data. Bioinformatics 34, i341–i349 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sagan S. A., et al. , Repertoire selection of AQP4-specific T cells that cause CNS autoimmune disease in mice. NCBI BioProject database. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/989238. Deposited 29 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. The data have been deposited on 29-Jun-2023 with links to BioProject accession number PRJNA989238 in the NCBI BioProject database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/989238) (67).