Abstract

Genes coding for human antibody Fab fragments specific for Entamoeba histolytica were cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. Lymphocytes were separated from the peripheral blood of a patient with an amebic liver abscess. Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from the lymphocytes, and then genes coding for the light chain and Fd region of the heavy chain were amplified by a reverse transcriptase PCR. The amplified DNA fragments were ligated with a plasmid vector and were introduced into Escherichia coli. Three thousand colonies were screened for the production of antibodies to E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS by an indirect fluorescence-antibody (IFA) test. Lysates from five Escherichia coli clones were positive. Analysis of the DNA sequences of the five clones showed that three of the five heavy-chain sequences and four of the five light-chain sequences differed from each other. When the reactivities of the Escherichia coli lysates to nine reference strains of E. histolytica were examined by the IFA test, three Fab fragments with different DNA sequences were found to react with all nine strains and another Fab fragment was found to react with seven strains. None of the four human monoclonal antibody Fab fragments reacted with Entamoeba dispar reference strains or with other enteric protozoan parasites. These results indicate that the bacterial expression system reported here is effective for the production of human monoclonal antibodies specific for E. histolytica. The recombinant human monoclonal antibody Fab fragments may be applicable for distinguishing E. histolytica from E. dispar and for use in the serodiagnosis of amebiasis.

Amebiasis is caused by the enteric protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. It has been estimated that 50 million people develop hemorrhagic colitis and extraintestinal abscesses, resulting in 100,000 deaths annually (36). E. histolytica has recently been reclassified into two species, E. histolytica Schaudinn, 1903, and Entamoeba dispar Brumpt, 1925, on the basis of biochemical, immunological, and genetic findings (8). The two species are morphologically inseparable, but only E. histolytica is responsible for invasive amebiasis. Therefore, for clinical and epidemiological reasons it is important to distinguish between E. histolytica and E. dispar (37).

The use of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) has been shown to be an important part of a specific and sensitive diagnostic strategy. To date, MAbs specifically reactive with either E. histolytica or E. dispar have been produced by hybridoma technology (10, 19, 20, 25–29, 33). It was reported that some of the MAbs were able to detect E. histolytica antigen in feces and serum by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (1, 11, 13, 14).

Recently, a new approach for the production of MAbs has been devised on the basis of recombinant DNA technology (2–4, 7, 24). In addition, vectors for the cloning and expression of immunoglobulin Fab fragment genes have been developed (30, 31). Here we report on the preparation of recombinant human MAb Fab fragments specific for E. histolytica. The use of a small amount of peripheral blood from a patient with amebiasis was effective at producing E. histolytica-specific MAbs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

Trophozoites of several strains of E. histolytica (listed in Table 1) and Entamoeba moshkovskii Laredo were axenically grown in BI-S-33 medium (9). Trophozoites of E. dispar SAW1734RclAR were cultured monoxenically with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in BCSI-S medium (32). Trophozoites of E. dispar SAW1719 were cultured xenically in Robinson’s medium (22). Trophozoites of Entamoeba hartmanni, Entamoeba coli, Endolimax nana, Dientamoeba fragilis, and Trichomonas hominis, isolated in our laboratories, were also xenically cultured in Robinson’s medium (22). Trophozoites of Giardia intestinalis Portland I were grown in modified BI-S-33 medium (15). All of these trophozoites were washed three times with ice-cold 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) before being used.

TABLE 1.

Reactivity by IFA test of human MAb Fab fragments to reference strains of E. histolytica and various enteric protozoan parasites

| Species | Strain | Zymo-deme | Reactivity

of the following clonea:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A235 (A429) | B220 | C546 | E244 | |||

| Entamoeba histolytica | HM-1:IMSS | II | ++ | + | + | + |

| HK-9 | II | ++ | ++ | + | + | |

| 200:NIH | II | + | + | + | + | |

| HB-301:NIH | II | ++ | + | + | ++ | |

| H-302:NIH | II | ++ | + | − | + | |

| H-303:NIH | II | ++ | + | + | ++ | |

| DKB | II | ++ | + | + | + | |

| C-3-2-1 | II | + | + | + | ++ | |

| SAW1627 | IIα− | ++ | ++ | − | + | |

| SAW755CR | XIV | ++ | + | + | ++ | |

| Entamoeba dispar | SAW1734RclAR | I | − | − | − | − |

| SAW1719 | I | − | − | − | − | |

| Entamoeba coli | − | − | − | − | ||

| Entamoeba hartmanni | − | − | − | − | ||

| Entamoeba mosh-kovskii | Laredo | − | − | − | − | |

| Endolimax nana | − | − | − | − | ||

| Dientamoeba fragilis | − | − | − | − | ||

| Trichomonas hominis | − | − | − | − | ||

| Giardia intestinalis | Portland I | − | − | − | − | |

++, strongly positive; +, positive; −, negative.

Amplification and cloning of the genes coding heavy and light chains.

Ten milliliters of peripheral blood was obtained from a patient with amebic liver abscess. Lymphocytes were separated from the blood by centrifugation with Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from lymphocytes by using the QuickPrep mRNA Purification Kit (Pharmacia). Reverse transcriptase PCR was performed with the GeneAmp RNA PCR Kit (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For cDNA synthesis, an oligo(dT)16 primer was used. For amplification of the genes encoding the κ and λ light chains and the Fd region of the γ heavy chain, the primer sets shown in Fig. 1 were used. The primer sequences contain the restriction sites for cloning. PCR amplification was performed in 100-μl reaction mixtures. Both sense and antisense primers were used at 1 μM. Thirty-five cycles of PCR were performed as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 50°C for 2 min, and polymerization at 72°C for 3 min. An initial denaturation step of 4 min at 94°C and a final polymerization step of 7 min at 72°C were also included. The amplified DNA fragments were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The DNA fragments were treated with AscI and NheI or SfiI and NotI and were then purified by agarose gel electrophoresis in combination with the QIAEX Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). Since the amount of the amplified λ light-chain gene was small, only the κ light-chain gene was ligated into an expression vector, pFab1-His2 (30), and was then introduced into Escherichia coli JM109. The bacteria were spread on Luria broth plates containing 50 μg of ampicillin per ml, and the vector with the inserts was selected. Next, the Fd heavy-chain gene was ligated into pFab1-His2, which contained the light-chain gene, and was introduced into Escherichia coli.

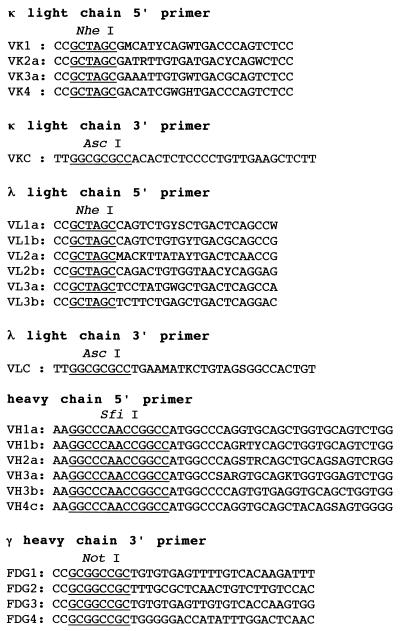

FIG. 1.

Primers used for PCR amplification of human immunoglobulin genes. Primer sequences are aligned from 5′ to 3′. Restriction sites are underlined. Degenerate nucleotides are indicated as follows: M = A or C, Y = C or T, W = A or T, R = A or G, H = A, C, or T, S = C or G, and K = T or G.

Expression in Escherichia coli and screening of clones.

Each clone was cultured in 2 ml of super broth (30 g of tryptone, 20 g of yeast extract, 10 g of MOPS [morpholinepropanesulfonic acid] per liter [pH 7]) containing ampicillin until an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 to 0.8 was achieved. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (final concentration, 0.1 mM) was added to the bacterial cultures, which were then incubated overnight at 30°C. The bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation, suspended in 150 μl of PBS containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and then sonicated. The lysates were centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min. The resultant supernatant was subjected to screening by an indirect fluorescent-antibody (IFA) test. Each of the positive clones selected by the screening process was cultured in 1 liter of medium. Twenty milliliters of the resultant supernatant, prepared as described above, was used in the present study.

DNA sequencing.

Cloned DNA fragments coding the heavy and light chains were recloned into sequencing vectors CV-1 and CV-2, respectively. Cycle sequencing in both directions was performed with Thermo Sequenase (Amersham Life Science, Cleveland, Ohio) with M13 forward (5′-CACGACGTTGTAAAAACGAC-3′) and reverse (5′-GGATAACAATTTCACACAGG-3′) primers. The reactions were run on a model 4000L automated DNA sequencer (LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebr.).

IFA test.

The IFA test, which was performed with formalin-fixed trophozoites which were smeared on glass slides and air dried, was carried out as described previously (28). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat immunoglobulin G (IgG) to human IgG Fab (Organon Teknica Co., Durham, N.C.) was used as the secondary antibody. An IFA test with live, intact trophozoites was also performed as described previously (29).

Western immunoblot analysis.

Western immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously (28) and was based on the procedure of Towbin et al. (34). Trophozoites of E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS suspended in PBS were solubilized with an equal volume of the sample buffer (17) containing 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM N-α-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone, 2 mM p-hydroxymercuriphenyl sulfonic acid, and 4 μM leupeptin for 5 min at 95°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was subjected to electrophoresis in a 7.5% running gel under nonreducing conditions with Laemmli’s buffer system and was then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Each strip of the membrane was incubated with 500 μl of Escherichia coli extract containing MAb Fab fragments. The plasma fraction of peripheral blood from the patient with an amebic liver abscess, obtained during the separation of lymphocytes by Ficoll-Paque centrifugation, served as a positive control. A polyclonal rabbit antibody to the heavy subunit of galactose (Gal)- and N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (GalNAc)-inhibitable lectin of E. histolytica, provided by W. A. Petri, Jr., of the University of Virginia, was also used. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep antibodies to human IgG F(ab′)2 and rabbit IgG (Organon Teknica) were used as secondary antibodies. Development was done with a Konica Immunostaining HRP-1000 kit (Konica Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported here have been submitted to DDBJ and have been assigned accession nos. AB022650 to AB022656.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the clones.

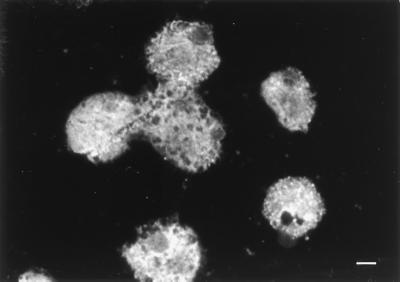

When 3,000 colonies were screened for human antibody Fab fragments reactive with E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS by the IFA test with formalin-fixed trophozoites, Escherichia coli lysates from five clones showed fluorescence (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Immunofluorescent photomicrograph of formalin-fixed trophozoites of E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS treated with recombinant human MAb A429, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat IgG to human IgG Fab. Bar, 10 μm.

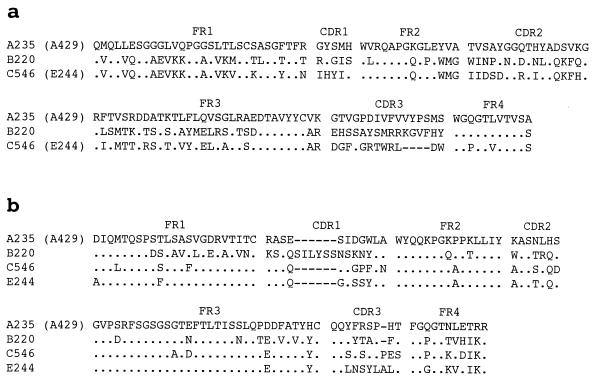

The genes coding the heavy and κ chains of these clones were sequenced. The deduced amino acid sequences are shown in Fig. 3. Concerning the heavy-chain genes, the sequences of clones A235 and A429 and of clones C546 and E244 were identical. The κ chain sequences of clones A235 and A429 were also identical. The sequences of the variable (V) regions of the heavy and κ chains were compared with sequences in the Kabat database. The heavy-chain V gene of A235 (A429) belonged to VH3; those of B220 and C546 (E244) to the VH1 group. The kappa-chain V genes of all clones except B220 belonged to Vκ1; that of B220 belonged to Vκ4.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of deduced amino acid sequences of genes coding the variable region of the heavy chain (a) and the κ light chain (b). Dots indicate identical amino acids. Hyphens designate gaps added to permit alignment. FR, framework region; CDR, complementarity-determining region.

Reactivities of Fab fragments.

The reactivities of the recombinant human MAb Fab fragments to nine reference strains of E. histolytica were examined by the IFA test with formalin-fixed trophozoites (Table 1). Clones A235 (A429), B220, and E244 reacted with all the strains. However, clone C546 failed to react with strains H-302:NIH and SAW1627. When the reactivities of these MAb Fab fragments to various enteric protozoan parasites was examined, none reacted with trophozoites of E. dispar, E. moshkovskii, E. coli, E. hartmanni, E. nana, D. fragilis, T. hominis, or G. intestinalis. The reactivities of the MAbs to live intact trophozoites of E. histolytica in suspension were also examined. However, fluorescence was not observed, indicating that epitopes are not present on the cell surface.

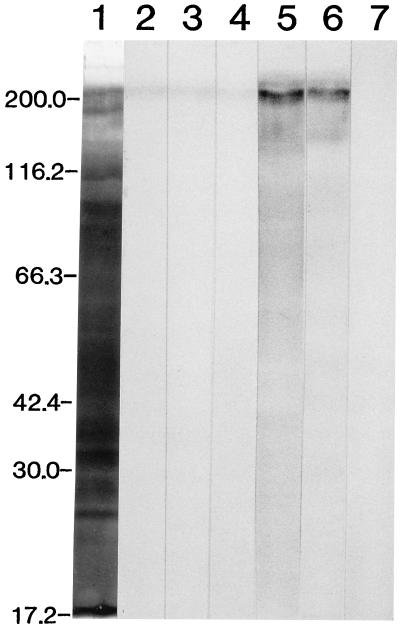

The molecular mass of the antigen(s) recognized by the Fab fragments was examined by Western immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4). Clones A235 (A429) and B220 recognized the 260-kDa band under nonreduced conditions. Similar bands were strongly recognized by plasma from the patient with an amebic liver abscess (the donor of the lymphocytes) and by a rabbit polyclonal antibody to the heavy subunit of Gal- and GalNAc-inhibitable lectin. No positive band was elicited by incubation with clone C546 or E244.

FIG. 4.

Western immunoblot analysis of reactivity of recombinant human MAb Fab fragments with trophozoites of E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS. Cell lysates were subjected to electrophoresis in a 7.5% running gel and were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The protein bands in lane 1 were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lanes 2 to 7 were treated as follows: lane 2, clone A235; lane 3, clone A429; lane 4, clone B220; lane 5, plasma of a patient with amebic liver abscess (1:200 diluted); lane 6, rabbit antibody to Gal- and GalNAc-inhibitable lectin (5 μg); and lane 7, Escherichia coli lysates (vector control). This was followed by treatment with HRP-labeled sheep antibody to human IgG F(ab′)2 or HRP-labeled sheep antibody to rabbit IgG. Numbers to the left indicate the molecular masses of the markers (in kilodaltons).

DISCUSSION

Hybridoma technology (16) has resulted in unlimited supplies of specific rodent MAbs. However, it has been much less successful for the production of human MAbs. The present study demonstrates that the bacterial expression system reported here is effective for the production of human MAbs specific for E. histolytica. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the preparation of recombinant human MAb Fab fragments specific for any parasite. Western immunoblot analysis demonstrated that the antigen recognized by clones A235 (A429) and B220 is a major antigen of E. histolytica. Therefore, it may be possible to prepare human MAbs to such antigens by the screening of several thousand clones.

A possible use of recombinant human MAbs may be as controls in serodiagnosis (12). To interpret serologic data, known positive controls must be used. For agglutination tests, antibodies prepared in animals are available. However, for ELISA and the IFA test, which use second antibodies, human antibodies must be used as positive controls. The technology reported here offers unlimited supplies of human MAbs specific for any given pathogen.

The preparation of rodent MAb by hybridoma technology takes about 3 months by standard protocols (26, 27, 29). Most of the technician’s time is spent on the immunization of mice and cloning of the hybridoma cells. By using the peripheral blood of patients with amebiasis, it will be possible to obtain human MAbs within 1 month.

The most significant application of human MAbs would be as therapy and passive immunization, just as polyclonal antibodies have been used (23). Western immunoblot analysis demonstrated that A235 (A429) and B220 are reactive with the same antigen recognized by a rabbit polyclonal antibody to the heavy subunit of Gal- and GalNAc-inhibitable lectin. It is known that there are adherence-blocking epitopes in the heavy subunit of the lectin (18, 21). We have recently observed that a recombinant mouse MAb Fab fragment specific for a 150-kDa surface antigen of E. histolytica inhibits amebic adherence to erythrocytes (6, 30). Therefore, if the human Fab fragment prepared in the present study can inhibit amebic adherence to mammalian cells, it may be valuable for clinical use. However, in preliminary experiments, the adherence of E. histolytica trophozoites to erythrocytes was not affected (data not shown). Since we could not localize the epitope on the cell surface of intact trophozoites by the IFA test, clones A235 (A429) and B220 may recognize the cytoplasmic domain of the Gal- and GalNAc-inhibitable lectin (35).

It is known that the heavy chain is dominant in determining antigen binding (5). In the present study, although the heavy-chain sequences of C546 and E244 were identical, the reactivities of these MAbs to several strains of E. histolytica were quite different. This observation suggests that the strength of binding activity to antigen is changeable by displacement of the light chain.

In this study, genes with identical sequences were cloned. The reason why the same genes were cloned is unclear. It seems likely that a large number of lymphocytes that express the gene existed. Otherwise, several populations of genes were predominantly amplified by PCR. In any event, for the cloning of antibody genes encoding the minor antigen of E. histolytica, we recommend that high titers of the antibody gene library be constructed and a phage display system be used for screening (5).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to O. Suzuki and W. A. Petri, Jr., for gifts of primers and antibody. We also thank W. Stahl for reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan, a Tokai University School of Medicine Research Aid, a grant from Ohyama Health Foundation, and a grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abd-Alla M D, Jackson T F H G, Gathiram V, El-Hawey A M, Ravdin J I. Differentiation of pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica infections from nonpathogenic infections by detection of galactose-inhibitable adherence protein antigen in sera and feces. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2845–2850. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2845-2850.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbas C F, III, Kang A S, Lerner R A, Benkovic S J. Assembly of combinatorial antibody libraries on phage surfaces: the gene III site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7978–7982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.7978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Better M, Chang C P, Robinson R R, Horwitz A H. Escherichia coli secretion of an active chimeric antibody fragment. Science. 1988;240:1041–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.3285471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton D R, Barbas III C F, Persson M A A, Koenig S, Chanock R M, Lerner R A. A large array of human monoclonal antibodies to type 1 human immunodeficiency virus from combinatorial libraries of asymptomatic seropositive individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10134–10137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton D R, Barbas C F., III Human antibodies from combinatorial libraries. Adv Immunol. 1994;57:191–280. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60674-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng X-J, Tsukamoto H, Kaneda Y, Tachibana H. Identification of the 150-kDa surface antigen of Entamoeba histolytica as a galactose- and N-acetyl-d-galactosamine-inhibitable lectin. Parasitol Res. 1998;84:632–639. doi: 10.1007/s004360050462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Condra J H, Sardana V V, Tomassini J E, Schlabach A J, Davies M-E, Lineberger D W, Graham D J, Gotlib L, Colonno R J. Bacterial expression of antibody fragments that block human rhinovirus infection of cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2292–2295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamond L S, Clark C G. A redescription of Entamoeba histolytica Schaudinn, 1903 (Emended Walker, 1911) separating it from Entamoeba dispar Brumpt, 1925. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993;40:340–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diamond L S, Harlow D R, Cunnick C C. A new medium for the axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica and other Entamoeba. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1978;72:431–432. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(78)90144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Haque R, Rehman T, Aguirre A, Jaramillo C, Castañon G, Hall A, Guhl F, Ruiz-Palacios G, Warhurst D C, Miles M A. A monoclonal antibody for distinction of invasive and noninvasive clinical isolates of Entamoeba histolytica. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2807–2813. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2807-2813.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Haque R, Rehman T, Aguirre A, Hall A, Guhl F, Warhurst D C, Miles M A. Diagnosis of amebic dysentery by detection of Entamoeba histolytica fecal antigen by an invasive strain-specific, monoclonal antibody-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:964–970. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.964-970.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hackett J, Jr, Hoff-Velk J, Golden A, Brashear J, Robinson J, Rapp M, Klass M, Ostrow D H, Mandecki W. Recombinant mouse-human chimeric antibodies as calibrators in immunoassays that measure antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1277–1284. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1277-1284.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haque R, Kress K, Wood S, Jackson T F H G, Lyerly D, Wilkins T, Petri W A., Jr Diagnosis of pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica infection using a stool ELISA based on monoclonal antibodies to the galactose-specific adhesin. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:247–249. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haque R, Neville L M, Wood S, Petri W A., Jr Detection of Entamoeba histolytica and E. dispar directly in stool. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:595–596. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keister D B. Axenic culture of Giardia lamblia in TYI-S-33 medium supplemented with bile. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:487–488. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Köhler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256:495–497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann, B. J., C. Y. Chung, J. M. Dodson, L. S. Ashley, L. L. Braga, and T. L. Snodgrass. Neutralizing monoclonal antibody epitopes of the Entamoeba histolytica galactose adhesin map to the cysteine-rich extracellular domain of the 170-kilodalton subunit. Infect. Immun. 61:1772–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Mirelman D, Keren Z, Bracha R. Cloning and partial characterization of an antigen detected on membrane surfaces of non-pathogenic strains of Entamoeba histolytica. Arch Med Res. 1992;23:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petri W A, Jr, Jackson T F H G, Gathiram V, Kress K, Saffer L D, Snodgrass T L, Chapman M D, Keren Z, Mirelman D. Pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains of Entamoeba histolytica can be differentiated by monoclonal antibodies to the galactose-specific adherence lectin. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1802–1806. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1802-1806.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petri W A, Jr, Snodgrass T L, Jackson T F H G, Gathiram V, Simjee A E, Chadee K, Chapman M D. Monoclonal antibodies directed against the galactose-binding lectin of Entamoeba histolytica enhance adherence. J Immunol. 1990;144:4803–4809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson G L. The laboratory diagnosis of human parasitic amoebae. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1968;62:285–294. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(68)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seydel K B, Braun K L, Zhang T, Jackson T F H G, Stanley S L., Jr Protection against amebic liver abscess formation in the severe combined immunodeficient mouse by human anti-amebic antibodies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:330–332. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skerra A, Plückthun A. Assembly of a functional immunoglobulin Fv fragment in Escherichia coli. Science. 1988;240:1038–1041. doi: 10.1126/science.3285470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strachan W D, Chiodini P L, Spice W M, Moody A H, Ackers J P. Immunological differentiation of pathogenic and non-pathogenic isolates of Entamoeba histolytica. Lancet. 1988;i:561–563. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tachibana H, Kobayashi S, Cheng X-J, Hiwatashi E. Differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica from E. dispar facilitated by monoclonal antibodies against a 150-kDa surface antigen. Parasitol Res. 1997;83:435–439. doi: 10.1007/s004360050276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tachibana H, Kobayashi S, Kaneda Y, Takeuchi T, Fujiwara T. Preparation of a monoclonal antibody specific for Entamoeba dispar and its ability to distinguish E. dispar from E. histolytica. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 1997;4:409–414. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.4.409-414.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tachibana H, Kobayashi S, Kato Y, Nagakura K, Kaneda Y, Takeuchi T. Identification of a pathogenic isolate-specific 30,000-Mr antigen of Entamoeba histolytica by using a monoclonal antibody. Infect Immun. 1990;58:955–960. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.955-960.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tachibana H, Kobayashi S, Nagakura K, Kaneda Y, Takeuchi T. Reactivity of monoclonal antibodies to species-specific antigens of Entamoeba histolytica. J Protozool. 1991;38:329–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1991.tb01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tachibana H, Takekoshi M, Cheng X-J, Maeda F, Aotsuka S, Ihara S. Bacterial expression of a neutralizing mouse monoclonal antibody Fab fragment to a 150-kilodalton surface antigen of Entamoeba histolytica. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:35–40. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.1.9988319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takekoshi M, Maeda F, Tachibana H, Inoko H, Kato S, Takakura I, Kenjyo T, Hiraga S, Ogawa Y, Horiki T, Ihara S. Neutralizing human monoclonal Fab fragment specific for human cytomegalovirus displayed on filamentous phage. J Virol Methods. 1998;74:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeuchi T, Kobayashi S. Entamoeba dispar: cultivation without viable associate and its characterization. Arch Med Res. 1997;28:S108–S109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torian B E, Reed S L, Flores B M, Creely C M, Coward J E, Vial K, Stamm W E. The 96-kilodalton antigen as an integral membrane protein in pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica: potential differences in pathogenic and nonpathogenic isolates. Infect Immun. 1990;58:753–760. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.3.753-760.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vines R R, Ramakrishnan G, Rogers J B, Lockhart L A, Mann B J, Petri W A., Jr Regulation of adherence and virulence by the Entamoeba histolytica lectin cytoplasmic domain, which contains a β2 integrin motif. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2069–2079. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh J A. Prevalence of Entamoeba histolytica infection. In: Ravdin J I, editor. Amebiasis. Human infection by Entamoeba histolytica. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1988. pp. 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. Entamoeba taxonomy. Bull W H O. 1997;75:291–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]