Abstract

It is unclear how autonomy-related parenting processes are associated with Latinx adolescent adjustment. This study uses Latent Profile Analysis to identify typologies of parental monitoring and parent–adolescent conflict and examines their association with Latinx youth’s school performance and depressive symptoms. The sample included 248 Latinx 9th and 10th graders (50% female) who completed surveys during fall (Time 1) and spring (Time 2) semesters of the school year. When compared to a high monitoring/low conflict parenting profile, a moderate monitoring/moderate conflict profile was associated with stronger declines in school performance; for boys, a high monitoring/moderately high conflict profile also was associated with greater increases in depressive symptoms. For Latinx immigrant families, researchers should consider monitoring and conflict as co-occurring processes.

Keywords: Latinx adolescents, Latent profile analysis, Parental monitoring, Parent–adolescent conflict, Depressive symptoms, School performance

Introduction

Adolescent increases in autonomy and independence often are accompanied by a renegotiation of parent-child boundaries, declines in parental authority, and heightened parent-child conflicts. Informed by research on families who have lived in the U.S. for generations, researchers speculate that adolescent autonomy leads to declines in parental monitoring and increases in parent–child conflicts (Laursen and Collins 2009; Smetana 1995a). It is unclear, however, how parental monitoring and parent-adolescent conflict are experienced among Latinx adolescents whose families have immigrated to the U.S. The combination of Latino values emphasizing family loyalty and interdependence, as well as mainstream U.S. values endorsing youth’s independence, creates a unique context for autonomy-related parenting processes among many Latinx adolescents (Villalobos-Solis et al. 2016). Little empirical work has focused on interrelated, parent-child dynamics relevant to Latinx adolescent autonomy. Understanding heterogeneity in Latinx adolescent experiences of parents’ monitoring behaviors, parent-child conflicts, and in the co-occurrence of monitoring and conflicts may help researchers gain greater insight into the optimal parent-child dynamics for Latinx adolescents’ adjustment.

This study uses person-centered methods to (1) describe patterns of parental monitoring and parent-adolescent conflicts in Latinx families and (2) examine associations between these parenting patterns with youth’s school performance and depressive symptoms during high school. Mexican- and Central American-origin U.S. adolescents are at heightened risk for low school performance and poor mental health (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC 2016; Child Trends 2017), and these outcomes can compromise health and well-being through adulthood (Loeber and Burke 2011). Learning about processes that predict both of these outcomes is important because adolescents’ capacity to perform well in school often depends on youth’s positive mental health (Ryan and Deci 2000). The present study examines how autonomy-related parenting typologies are associated with adolescent school performance and depressive symptoms in high school during the fall semester and, again during the spring semester, four to six months later. Survey data are collected from Mexican- and Central American-origin adolescents living in a new immigrant destination, thereby, maximizing the relevance of study findings for the multitude of new immigrant areas burgeoning in the U.S. (Frey 2015).

Parental Monitoring, Parent–Adolescent Conflict, and Latinx Adolescent Adjustment

Parent–adolescent conflicts, indicated by arguments and/or disagreements, are important proximal correlates of adolescent mental health and school performance, including for Latinx adolescents (Lopez-Tamayo et al. 2016; Weymouth et al. 2016; Wheeler et al. 2015). Conflicts tend to increase from late childhood into early adolescence and then decrease in frequency thereafter (Laursen and Collins 2009; Van Doorn et al. 2011). The preponderance of evidence indicates higher levels of conflict in parent-daughter versus parent-son relationships (Pasch et al. 2006) and stronger associations between parent-child conflict and negative outcomes among girls, compared to boys (Weymouth et al. 2016). Among a sample of Mexican-American adolescent females, those experiencing more frequent conflicts with their mothers around issues such as youth’s friends and physical appearance experienced more than a five-fold increase in the likelihood of being in a “low functioning” group, characterized by poor mental health and low academic motivation, than in a “high functioning” group (Bámaca-Colbert et al. 2011). Similarly, parent-adolescent conflicts around behaviors such as youth’s schoolwork, curfews, dating, and family obligations were associated with more depressive symptoms among Mexican-American female adolescents (Bámaca-Colbert et al. 2012).

Parental monitoring often is assessed by behavioral control and solicitation. Behavioral control refers to parental limits and oversight, such as parents’ requiring that youth get permission when going out with friends and making sure that youth get homework done; solicitation refers to parents’ information seeking, such as asking where the young person is going and what she or he did while spending time with friends. Research based on samples of youth in Western European countries and of U.S. youth from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds has shown that youth experience progressively less behavioral control and solicitation as they spend more time in the company of peers and away from family from early to late adolescence (Gutman et al. 2017; Keijsers et al. 2009; Kerr et al. 2010). Among Latinx adolescents, girls have been shown to experience greater parental monitoring than boys (Lac et al. 2011). Higher levels of parental monitoring, assessed by a mix of behavioral control and solicitation practices, tend to be associated with better adjustment among Latinx adolescents (Nair et al. 2018; Santiago et al. 2014). Research among first- and second-generation Latinx high school students has shown that monitoring assessed by parental knowledge of youth’s activities and whereabouts, are associated with better academic motivation and engagement (Plunkett and Bámaca-Gómez 2003; Plunkett et al. 2009). Findings from research assessing parents’ solicitation often are inconsistent. For example, one study found no association between parental solicitation and youth’s school performance and depressive symptoms (Blocklin et al. 2011); another found that solicitation was associated with fewer depressive symptoms for males and females and greater educational expectations for males (Wheeler et al. 2015); and, a third showed positive associations between solicitation and adolescent problem behavior (Fernandez et al. 2018). It is possible that such inconsistent findings are explained by variability in the co-occurring dynamics of monitoring and conflict. For example, solicitation may not co-occur with elevated conflict for some parent-adolescent dyads, but may be accompanied by parent–child conflict in other dyads. Learning about the co-variation between different kinds of monitoring practices and conflicts can help advance knowledge about their potential impacts on adolescent adjustment and address prior inconsistencies in research.

It is unclear how the co-occurrence of parental monitoring and parent-adolescent conflict might be experienced for Latinx adolescents whose families immigrated to the U. S. Reactance theory suggests that parents’ limits on adolescent behavior will co-vary with parent–child conflicts (Smetana 2006). Latinx youth may resent parents’ monitoring behaviors and experience conflicts with parents in situations where youth desire the same kind of autonomy as afforded to their mainstream U.S. peers (Kagitcibasi 2005). Alternatively, the co-variation between high conflict and monitoring purported to occur for adolescents whose families have lived in the U.S. for generations may not extend to Latinx youth due to traditional cultural values endorsing the legitimacy of parental authority (Phinney et al. 2000) and the primacy of family over peers (Lionetti et al. 2018; Pasch et al. 2006; Kakihara and Tilton-Weaver 2009). By utilizing person-centered analytic approaches to measuring parenting, the present study identifies patterns of various kinds of parental monitoring behaviors and parent–adolescent conflicts experienced by Latinx adolescents whose families immigrated to the U.S.

Social domain theory (Turiel 1983) provides valuable insight into the conditional nature of monitoring and conflicts as co-occurring processes. According to this theory, adolescents are more receptive to parental oversight of behaviors that increase risks to youth well-being than to oversight of behaviors that youth perceive as harmless (Smetana 1995a, b). Smetana and colleagues postulate that parent-child conflicts stemming from parental restrictions occur around youth behaviors falling within “personal” and “ambiguously personal” domains. Personal domain behaviors concern adolescents’ privacy and personal choice, such as decisions around hairstyle and clothing; ambiguously personal behaviors fall under adolescents’ personal jurisdiction and parental authority, such as how youth spend their time with peers, whether or not they get schoolwork done, and how late they stay up on school nights (Smetana and Daddis 2002). Some research findings for Latinx adolescents align well with the theory that adolescents are more receptive to parental limits when there is a greater potential for risk tied to a particular behavior. For example, Latinx adolescents whose families immigrated to the U.S. reported fewer depressive symptoms when experiencing parental monitoring around unsupervised time with peers, a potentially risky activity, but reported more depressive symptoms when experiencing monitoring around less consequential activities such as youth’s homework, time spent after school, and the school day (Roche et al. 2018). Extrapolating from these findings to conflict, the present study examines whether youth are more likely to experience conflict and monitoring simultaneously when experiencing restrictions on behaviors posing less direct risk to adolescent health and safety.

Current Study

Informed by social domain theory and knowledge about Latinx and mainstream U.S. American cultural systems, this research seeks to answer two research questions: (1) How do Latinx adolescents whose families have immigrated to the U.S. experience parenting typologies defined by co-varying patterns of parental monitoring and parent-child conflicts? (2) How are parenting typologies associated with Latinx adolescents’ school performance and depressive symptoms during Fall (Time 1) and Spring (Time 2) semesters? It is hypothesized that any latent profile characterized by higher monitoring and less conflict will be associated with youth reporting better school performance and fewer depressive symptoms contemporaneously and over time. Parental monitoring behaviors and parent-adolescent conflicts are assessed across a variety of adolescent behaviors within personal and ambiguously personal domains of behavior. A person-centered approach is useful for identifying subgroups of adolescents that experience different combinations of parenting processes (Bergman and Trost 2006). Gender differences in pathways from parenting to youth outcomes are explored due to the differential experiences and consequences of parenting and parent-child relationships for boys and girls (Plunkett et al. 2009; Wheeler et al. 2015). To account for important demographic and social context characteristics of youth and their families, models account for indicators of youth’s age and immigrant generational status due to the salience that each has to parenting and parent-adolescent relationships (Laursen and Collins 2009; Weymouth et al. 2016). Analytic models also account for relevant social context variables. Adolescent school performance and mental health can be jeopardized by youth’s deviant peer affiliation (Barrera et al. 2002) and by a family not owning their home, an indicator of unstable housing and less household wealth (McConnell 2015). Finally, the models account for the number of younger siblings at home because family caretaking, an important part of Latinx family life, has demonstrated both positive and negative impacts on adolescent well-being (East 2010; Kuperminc et al. 2009).

Methods

Procedures

The present study uses data from school-based surveys administered in the Fall Semester and, again, four to six months later in the Spring semester, of the 2014–15 school year to Latinx adolescents. Youth in this study all attended a public high school in suburban Atlanta, an emerging immigrant destination with rapid growth in the Latinx population during the 1990s (Odem 2008). Study materials, including consents and survey instruments, were provided in English and Spanish. Validated Spanish versions of survey measures were used when available. For other measures, as well as for consent and recruitment documents, materials were translated and back translated by individuals with extensive experience and knowledge of the target population. Within grade and gender strata of Latinx students enrolled in the 9th and 10th grade (N = 507), a random sample of n = 335 students was selected to participate in this study. From enrollment lists, 24 students were excluded due to no longer being enrolled in school at the time of the Fall data collection or not having a parent reachable by phone, a requirement for obtaining parental permission. Among the 311 eligible students, the response rate was 81%, resulting in a final sample of 252 students. Non-respondents included students whose parents did not provide permission and students who did not show up for scheduled surveys. Among the 252 surveyed youth, four were excluded due to special education needs or because they were from South America and thus not representative of Mexican- and Central American-origin individuals, the primary national origins in the target Latinx population. Among Time 1 (T1) participants surveyed in the fall semester (n = 248), 91% also were surveyed at Time 2 (T2), an average of just over four months later during youth’s spring semester; those lost-to-follow up had either transferred or dropped out of school.

Among the 248 participants, half (50%) were female, two-thirds (68%) were U.S. born, and 70% were of Mexican-origin. Central Americans of diverse national origins comprised the remaining 30%. The vast majority of mothers (94%) and fathers (96%) were foreign born. More than two-thirds of adolescents lived in homes that were rented (70%) versus owned. Youth completed self-administered surveys on mini-iPads using Qualtrics software, a password-protected and encrypted, web-based survey that integrates data collection and downloads (Qualtrics 2014). Survey completion took between 30 and 45 min. A small number of adolescents (n = 8; 3%) chose to complete the survey in Spanish. Youth were provided a $20 gift card at each time point in return for study participation. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the sponsoring institution.

Measures

Parenting typologies

To develop parenting typologies, a latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted using youth’s T1 responses to 22 separate items on parental monitoring and parent-child conflict. Of these items, 13 assessed monitoring (Stattin and Kerr 2000) and nine indicated parent–adolescent conflict (Robin and Foster 1989). Monitoring items assessed both parent solicitation and behavioral control practices. Adolescents reported on how often parents asked about things such as where the child went and what s/he did if out at night with friends (ambiguously personal) and did things such as make sure youth get homework done (personal) and get permission before going out with friends (ambiguously personal). Parent-adolescent conflict was assessed by asking adolescents how often they argued or disagreed with their parent about things such as staying up late on a school night (ambiguously personal), clothing/hairstyle (personal), and spending time with friends rather than family (ambiguously personal). Response categories ranged from 1 = never to 5 = always. We do not report Cronbach’s alpha due to the fact that individual items, rather than parenting scales, were submitted for the LPA.

Depressive symptoms

Adolescent depressive symptoms were assessed at T1 and T2 using seven items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD) scale (Radloff 1977); these items have shown strong validity for Latinx youth of different immigrant generations (Perreira et al. 2005). Adolescents reported on their past week experience of feeling lonely, depressed, sad, life was not worth living, fearful, and not being able to shake off the blues, even with the help of family or friends. Responses included: 1 = rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day); 2 = some or a little of the time (1 to 2 days); 3 = occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3 to 4 days), and 4 = most or all of the time (5 or more days). Two items—“life not worth living” and “feeling fearful”—were dropped from the scale due to low factor loadings. Higher scores on the resulting five-item scale indicated more depressive symptoms and ranged from 1 to 4, with a mean of 1.54 (SD = 0.71) at T1 and of 1.57 (SD = 0.73) at T2. The scale demonstrated high reliability (α = 0.87, T1; α = 0.84, T2).

School performance

School performance was assessed by grade point average (GPA) at T1 and T2 using youth’s report of grades in Math, English, Science, and Social Studies/History. Responses included A (4.0), B (3.0), C (2.0), D (1.0), and F (0). At T1, youth reported on grades received at the end of the prior academic year, which was spring semester of the 2013–14 academic year (M = 3.21, SD = 0.86); at T2, youth reported on grades received in the prior semester, which was the fall semester of the 2014–15 academic year (M = 2.93, SD = 0.84).

Covariates

Covariates were assessed at T1 and included several dummy coded demographic variables as well as a measure of youth’s deviant peer affiliation. Demographic variables included 0–1 dummy coded variables for youth gender (male = 1, 50% of the sample); youth nativity (U.S. born = 1, 68% of the sample) and family home ownership (own home = 1, 30% of the sample), and continuous measures of youth’s age in years (M = 15.21, SD = 1.01) and number of younger siblings (M = 1.74, SD = 1.09). Models also accounted for youth’s deviant peer affiliation, an index score of how many of the adolescent’s three closest friends were in a gang, dropped out of school, and/or planned to drop out before finishing 12th grade (0 = none, 1 = one, 2 = two, 3 = all three; M = 0.13, SD = 0.33).

Analysis Plan

Missing data

The three-form planned missing survey design was used as a cost-effective way to obtain valid survey data, while minimizing respondent burden (Little and Rhemtulla 2013; Rhemtulla et al. 2014). Youth were assigned randomly to take one of three surveys. Across all surveys, youth responded to items assessing demographics and youth outcomes (including depressive symptoms). For multi-item scales, such as those used to assess parenting, all surveys included a subset of scale items and a unique subset of items from these same scales. The planned missing data from the three-form survey design (33%) was missing completely at random and thus completely unbiased. Missing data due to item non-response ranged from 1 to 5% and were assumed to be missing at random based on low correlations with variables in the dataset. All missing data were imputed using the Quark package in R (Lang et al. 2017), whereby, principal components analysis was used to create a set of auxiliary variables, which were then used in the multiple imputation procedure (Howard et al. 2015). Analyses were run using 100 multiply imputed data sets produced using the Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) package in R (Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn 2011). Descriptive statistics were obtained using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp. 2016). Structural equation modeling (SEM) in Mplus 7.3 was used to test the associations of interest (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012).

Latent profile analysis

Latent profile analyses, a person-centered measurement approach useful for modeling heterogeneity within a group (Laursen and Hoff 2006; Magnusson 2003), was used to identify subgroups of adolescents who experience similar combinations of parent-adolescent conflict and parental monitoring. LPA was conducted using all 22 survey items assessing different kinds of parental monitoring behaviors and parent-adolescent conflicts. The optimal LPA solution was identified by finding the solution with the best interpretability, highest entropy, which measures how well profiles are classified, and lowest fit indices including Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR; Lo et al. 2001) and Vuong Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR; Nylund et al. 2007). Indices of fit were examined by estimating models with an additional profile until the model fit the data well (Kass and Wasserman 1995). Low BIC and AIC, and p-values from the VLMS were used to indicate a significant improvement in model fit when compared to the previous model (Golden 2000).

After identifying the optimal model in Mplus, parenting typology was examined as a manifest variable, and a series of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with F-tests were used to identify how membership in parenting profiles differed with respect to mean scores for individual parenting items and for T1 and T2 adolescent outcomes. Additional bivariate analyses examined how parenting types were associated with study background variables and adolescent outcomes. Cross-tabulations with chi-square tests of significance were run for analyses with categorical variables, and ANOVAs with F-tests were used for analyses with continuous variables. Bivariate analyses of parenting and adolescent outcomes were run separately for males and females. After conducting bivariate analyses in SPSS (IBM Corp., 2016), the data, including manifest indicators of parenting typology, were imported back into Mplus for Structural Equation Models.

Structural equation models

A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was run to correct for item measurement error in relationships between survey items and the latent construct of depressive symptoms as a way of determining the construct validity for depressive symptoms. Parceling techniques were used to attain greater reliability, more communality, a higher ratio of common-to-unique factor variance, fewer distributional violations, and less chance for correlated residuals or dual loadings than is the case for single item indicators of latent constructs (Little 2013). Measurement invariance for depressive symptoms was examined across gender and time. Invariance was assessed by running multiple group models and examining changes in model fit statistics when proceeding from configural to weak to strong invariance. Evidence for invariance was apparent if the change in CFI was <0.01, the value of the RMSEA remained within the confidence interval of the preceding model, and there was no statistically significant change in the chi-square value. Change in model fit statistics also were examined from multiple group models run to identify statistically significant gender differences in structural model pathways. Next, structural models were run to regress T2 GPA and depressive symptoms on these same outcomes assessed at T1, as well as study background variables. Structural models also included the estimation of pathways for within-time associations for parenting and youth outcomes. Measurement and structural models were deemed to fit underlying data adequately when the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was <0.05 and the comparative fit index (CFI) was >0.90 (Browne and Cudeck 1993; Hu and Bentler 1999). Following Lang and Little (2015), the grand mean data set from the 100 multiply imputed data sets was used to conduct multiple group analyses.

Results

Preliminary Findings

For the five items assessing depressive symptoms, CFA was conducted using item parceling techniques. The first parceled indicator was represented by the average of responses to items on youth having felt lonely and that their life had been a failure; the second parceled indicator was represented by the average score for youth having felt sad and that life was not worth living; and, the final indicator was represented by a single item on youth having felt depressed. Results from tests of measurement invariance across gender and time indicated factorial invariance across gender and time and partial strong invariance across time (depressive symptom parcels 1 and 2 were allowed to vary across time). Factor loadings for depressive symptoms ranged from 0.90 to 1.14 (unstandardized) and from 0.79 to 0.92 (standardized), all significant at a probability level <0.001.

LPA results indicated that a three-profile model provided the optimal representation of parenting. Although fit statistics improved from the three- to four-profile model (Table 1), the three-profile solution was retained due to the small cell size and poor interpretability of one group identified in the four-profile solution. These analyses identified three groups of youth differentiated by experiences of both monitoring and conflict. These groups are characterized by “High Monitoring/Low Conflict” (38%); “Moderate Monitoring/Moderate Conflict” (37%); and “High Monitoring/ Moderately High Conflict” (26%). Given that the mean scores on monitoring and conflict rarely dipped below, or above, respective scale midpoints (Table 2), no parenting profile was characterized by truly low monitoring or high conflict.

Table 1.

Comparison of models for latent profiles of parenting (N = 248)

| Number of Profiles | Log-likelihood | AIC | BIC | Lo-Mendell-Rubin | Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −7859.61 | 15799.23 | 15939.77 | – | – | – |

| 2 | −7471.27 | 15064.54 | 15278.85 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | 0.91 |

| 3 | −7306.13 | 14776.28 | 15064.38 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | 0.89 |

| 4 | −7205.03 | 14616.07 | 14977.95 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | 0.90 |

Note: Three-profile solution, shown in bold font, was selected for analyses in structural model due to its improved model fit statistics from the two-profile solution and because the four-profile solution resulted in an insufficient cell size for one of the profiles

Table 2.

Mean scores for parenting items across the three latent parenting profiles

| Parenting items | High monitoring low conflict | Moderate monitoring moderate conflict | High monitoring moderately high conflict |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 93 (38%) | n = 91 (37%) | n = 64 (26%) | |

| Solicitation | |||

| Parent asks… | |||

| where & with whom going before going out with friends | 4.67a | 3.58b | 4.48a |

| where & with whom went after out at night | 4.74a | 3.21b | 4.47a |

| what did with friends when together | 4.18a | 2.41b | 3.92a |

| how spent time after school | 4.02a | 2.24b | 3.97a |

| what day was like at school | 4.45a | 2.64b | 4.09a |

| asks about school work | 4.34a | 3.03b | 4.17a |

| Behavioral control | |||

| Need permission to go out with friends | 4.77a | 3.88b | 4.50a |

| Parent checks to see parent is home at friend’s home | 3.97a | 3.38b | 4.06a |

| Must tell parents how spent money | 2.90a | 2.03b | 3.42c |

| Parent makes sure homework gets done | 2.76a | 4.18b | 4.17b |

| Parent–adolescent conflict | |||

| Chores | 2.62a | 2.24b | 3.56c |

| Hairstyle, clothing | 1.56a | 2.15b | 2.78c |

| Schoolwork | 2.02a | 2.83b | 3.88c |

| How late up on school night | 1.98a | 2.20a | 3.42b |

| Who friends are and what they do | 1.85a | 2.13a | 3.86b |

| Talking back/being disrespectful | 2.04a | 2.62b | 3.31c |

| Youth time with friends vs. family | 1.68a | 2.30b | 2.78c |

| Youth privacy | 1.62a | 1.91a | 2.59b |

| How youth spends his/her money | 1.75a | 2.22b | 3.19c |

Notes: Different subscripts for values in same row indicate statistically significant differences at a probability of <0.05 for mean values of parenting items between parenting profiles, based on F-tests of significance

Results from the one-way ANOVA models with F-tests and Bonferroni post-hoc pair-wise comparisons indicated that parenting profiles mostly were distinguished by the levels of monitoring and conflict, rather than by a specific kind of monitoring behavior or conflict (Table 2). Adolescents in the high monitoring/low conflict profile, however, were unique with respect to the specific kind of monitoring behavior for two. The mean score for how frequently parents make sure that homework gets done (i.e., parental behavioral control) was significantly lower for adolescents in the “High Monitoring/Low Conflict” profile (M = 2.80), than for youth in the “High Monitoring/Moderately High Conflict” (M = 4.17) or “Moderate Monitoring/Moderate Conflict” (M = 4.18) profiles (F (2) = 55.13, p < 0.001). In addition, the mean score for how frequently the child needed to tell the parent how s/he spends money (i.e., parental behavioral control) was significantly lower for youth in the “High Monitoring/Low Conflict” profile (M = 2.90), as compared to the “High Monitoring/Moderately High Conflict” profile (M = 3.42; F (2) = 32.49, p < .001). Those two monitoring items were unique in that they did not assess parental monitoring of youth activities with peers or of youth’s unsupervised time.

In terms of conflict, the frequency of youth arguing and disagreeing with parents around various issues was incrementally higher in profiles characterized by, respectively, low, moderate, and moderately high conflict. There were, however, three exceptions specific to the type of conflict experienced. There were no statistically significant differences between the “High Monitoring/Low Conflict” and “Moderate Monitoring/Moderate Conflict” profiles with respect to mean scores for conflict regarding (1) how late youth stay up on school nights; (2) who youth’s friends are and what they do; and (3) youth’s privacy. Relative to other conflict items, which focused on issues such as chores, hairstyle/clothing, spending money, and talking back/being disrespectful, these three items have relatively greater salience to adolescent adjustment and potential risk.

Although there were no significant associations between study background variables and parenting profiles or between GPA and depressive symptoms at T1 or T2, adolescent outcomes varied significantly by gender, age, and youth’s deviant peer affiliation. Boys reported fewer depressive symptoms at both T1 (1.64 versus 1.44; F (246) = 4.34, p < 0.05) and T2 (1.65 versus 1.44; F (246) = 7.12, p < 0.01) and a lower GPA at both T1 (2.94 versus 2.62; F (242) = 9.75, p < 0.01) and T2 (2.92 versus 2.62; F (243)= 7.47, p < 0.01) than did girls. Affiliation with deviant peers also was associated positively with depressive symptoms at both time points (r = 0.15, p < 0.05), and older youth reported a lower T1 GPA (r =−0.25, p < 0.001).

Bivariate Associations between Parenting Type and Youth Outcomes

Results from one-way ANOVAs with F-tests indicated that school performance for boys and girls and depressive symptoms for boys varied significantly by parenting profile (see Table 3). Results from Bonferroni post-hoc pair-wise comparisons indicated that, for boys, a high monitoring/low conflict context was associated with less T1 and T2 depressive symptomology than was a high monitoring/moderately high conflict context. Boys in a high monitoring/ low conflict context also reported less T2 depressive symptomology than boys in a high monitoring/moderately high conflict context. In terms of school performance, boys in a high monitoring/low conflict context reported a significantly higher T1 and T2 GPA than those in a moderate monitoring/moderate conflict context and, at T1, than boys in a high monitoring/moderately high conflict context. Girls in the high monitoring/low conflict context reported significantly less T1 depressive symptomology than girls in the high monitoring/moderately high conflict context. In addition, girls in the high monitoring/low conflict context reported higher T1 GPA than did girls in the moderate monitoring/moderate conflict context. There were no significant associations between parenting and youth outcomes for girls at T2.

Table 3.

Comparison of means for time 1 (T1) and time 2 (T2) adolescent outcomes by parenting typologies for adolescent males (Top Row) and females (Bottom Row)

| High monitoring/low conflict | Moderate monitoring/moderate conflict | High monitoring/moderately high conflict | F Statistic (df) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 depressive symptoms | 1.19a | 1.51c | 1.61b | F(2) = 5.30** |

| 1.45 | 1.65 | 1.78 | F(2) = 2.56 | |

| T2 depressive symptoms | 1.15a | 1.57b | 1.62b | F(2) = 10.47*** |

| 1.59 | 1.68 | 1.73 | F(2) = 1.12 | |

| T1 grade point average | 2.93 | 2.46 | 2.44 | F(2) = 3.61* |

| 3.10 | 2.70 | 3.03 | F(2) = 3.16* | |

| T2 grade point average | 2.89a | 2.45b | 2.52 | F(2) = 4.61* |

| 3.04a | 2.67b | 3.08a | F(2) = 5.08** |

Notes: F-test indicates significance for overall between-group differences. The different subscripts for values in same row indicate statistically significant between-group differences at a probability of <0.05 for mean values of youth outcomes between parenting typologies. Results from Bonferroni post-hoc comparison tests manifest marginally statistically significant differences in T1 GPA by parenting profile: for females, the difference was between “high monitoring/low conflict” and “moderate monitoring/moderate conflict” (p = 0.052); and, for males, differences were between “high monitoring/low conflict” and both “moderate monitoring/moderate conflict” (p = 0.087) and “high monitoring/moderately high conflict” (p = 0.054)

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

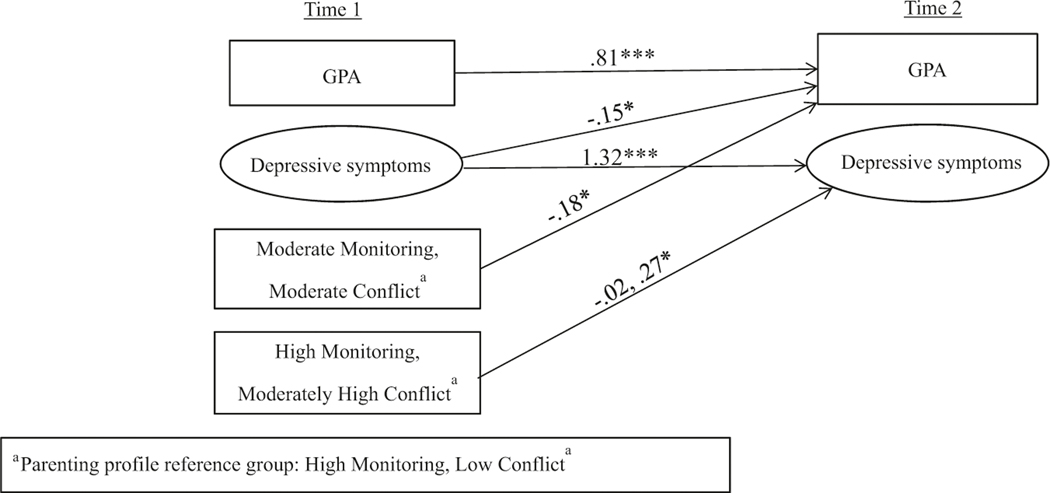

Multivariate Associations: Structural Equation Models

SEM results for associations between parenting typologies and adolescent outcomes over time are shown in Fig. 1. Results from multiple group models indicated an improvement in model fit after allowing two pathways to differ by gender: (1) high monitoring/moderately high conflict parenting to T2 depressive symptoms (Δ χ2 (1) = 3.96, p < 0.05) and (2) youth’s deviant peer affiliation to T2 GPA (Δ χ2 (1) = 9.78, p < 0.01). When compared to adolescents in the high monitoring/low conflict profile, adolescents who experienced moderate monitoring/moderate conflict reported significantly stronger declines in GPA from T1 to T2 (B = −0.18, SD = 0.08; β = −0.13, p < 0.05). Adolescent boys in the high monitoring/moderately high conflict profile also reported significantly stronger increases in depressive symptoms from T1 to T2 than boys in the high monitoring/low conflict profile (B = 0.27, SD = 0.13, β = 0.15, p < 0.05). Finally, T1 depressive symptoms were associated with significant declines in GPA from T1 to T2 for all youth (B = −0.15, SD = 0.07, β = −0.11, p < 0.05). The only covariate to reach statistical significance was shown for boys: greater affiliation with deviant peers was associated with a significant decline in boys’ GPA from T1 to T2 (B = −0.26, SD = 0.10, β = −0.19, p < 0.01). The structural model demonstrated a strong model fit (χ2 (109) = 166.607; RMSEA = 0.065 (0.044, 0.084); CFI = 0.96).

Fig. 1.

Within and across time associations between parenting typologies and Latinx adolescent adjustment. Notes: Unstandardized coefficients for statistically significant (p < 0.05) paths shown. Statistically significant (p < 0.05) gender differences indicated by showing the value for females, followed by value for males. The structural model controls for within-time associations and for associations between youth outcomes and study covariates including youth’s age, number of younger siblings, immigrant generational status, affiliation with deviant peers, and living in home that family owns (versus rents). χ2 (109) = 166.607, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.065 (0.044, 0.084); CFI = 0.96. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Alternative Models

Findings from alternative models were run to examine the robustness of results shown above. First, a model was run excluding this study’s set of background variables. Findings from this pared-down model replicated parenting associations with youth outcomes illustrated in Fig. 1. Second, the final model was run excluding the subset of adolescents who were very recent immigrants—youth who immigrated to the U.S. at age 10 or older (n = 12, 5%). There were no changes in study results when excluding very recently immigrated youth.

Discussion

There is a need to understand how co-occurring experiences of parental monitoring and parent-adolescent conflict matter for the adjustment of Latinx adolescents whose families have immigrated to the United States. Parenting and parent-child relationships within Latinx immigrant families tend to unfold within a cultural context emphasizing family interdependence and harmony to a greater degree than is the case for families who have lived in the U.S. for generations (Smokowski et al. 2008). Among Mexican- and Central American-origin 9th and 10th graders, this study used person-centered techniques to assess parenting typologies defined by monitoring and conflict and then examined how these typologies were associated with adolescent school performance and mental health over the span of four to six months during high school. Informed by social domain theory, this study focused on monitoring behaviors and parent–adolescent conflicts pertinent to youth behaviors in domains where the legitimacy of parental authority is questionable. In this way, this research advances knowledge about autonomy-related parenting dynamics for adolescent behaviors most likely to create discord between youth and their parents.

This study’s results manifest important within-person variability in the co-occurrence of monitoring and conflict among Latinx adolescents whose families have immigrated to the U.S. Response scores for individual parenting items indicate that over one-third (38%) of adolescents experience high parental monitoring and low conflict, about a quarter (26%) experience high monitoring and moderately high conflict, and over one-third (37%) experience moderate levels of both monitoring and conflict. The high levels of monitoring characterizing most adolescents in this study (e.g., no group was characterized by low monitoring and three-quarters of youth were characterized by high monitoring) corroborate scholarship showing that Latinx parents tend to engage in high levels of parental behavioral control due to cultural values emphasizing the importance of youth’s respect for parental authority (Halgunseth et al. 2006). Aligned with reactance and social domain theories, parent-adolescent conflicts appear to co-occur with monitoring for situations where parents arguably have less legitimate authority because the behavior is in the personal domain. For example, adolescents in a high monitoring/low conflict context do not report high monitoring with respect to parents making sure homework gets done and, to some extent, youth needing to tell parents how they spend their money. Parents’ selective provision of autonomy for issues in the personal domain posing little risk to youth may help adolescents engage in responsible behavior and feel trusted by parents, thereby mitigating parent–child conflicts.

Although many scholars consider that inconsistent findings in the parental monitoring literature stem from definitional and measurement variability in the monitoring construct (Anderson and Branstetter 2012; Augenstein et al. 2016), this study’s findings suggest that heterogeneity in adolescent experiences of monitoring also may contribute to these inconsistencies. By ignoring this larger parenting context, findings for parental monitoring may mask heterogeneity important to Latinx adolescents’ adjustment. To date, researchers have not used person-centered methods to model co-occurrences of specific aspects and domains of monitoring and conflict nor tested interactions between parent–child conflict and monitoring. Although this research does not assess the breadth of components comprising a parenting context, including parenting style, socialization goals, and parenting practices, the idea that an individual parenting behavior has a different meaning depending upon the context of other parenting behaviors is not new (Darling and Steinberg 1993).

There is strong evidence indicating that a combination of high parental monitoring and low-parent-adolescent conflict may facilitate positive adjustment for Latinx adolescents in the 9th and 10th grade. When compared to a high monitoring/low conflict context, a moderate monitoring/moderate conflict context was related to stronger declines in GPA for boys and girls and a high monitoring/moderately high conflict context was associated with stronger increases in depressive symptoms for boys. These longitudinal results are especially compelling given the brief time lag—four to six months—between the two time points of data collection.

The pronounced salience of parenting typologies to outcomes among boys in this study is noteworthy. Both bivariate and multivariate results indicated that parenting typologies were more strongly associated with school performance and depressive symptoms for boys, compared to girls. This finding runs contrary to theory (Rudolph 2002) and research indicating that parenting factors, particularly parent–child conflict, are more strongly tied to the adjustment of adolescent females, compared to males (Chung et al. 2009; Weymouth et al. 2016). As an exception to these studies, Lorenzo-Blanco and colleagues found that family conflict was more strongly linked to depressive symptoms for Latino adolescent boys than girls. Those scholars speculated that Latino boys might suffer emotionally when family conflict is elevated due to boys perceiving a need to protect the family (Lorenzo-Blanco et al. 2012). This study’s findings suggest that the co-occurrence of specific monitoring and conflict processes may be particularly relevant to Latino adolescent males whose families immigrated to the U.S. due to the unique set of stressors tied to masculinity and immigrant status. For example, when compared to their female counterparts, Mexican-American adolescent males have been shown to hold more traditional gender role attitudes throughout adolescence (Updegraff et al. 2014). Further complicating these attitudes is the fact that Latinx youth in this study lived in families with few socioeconomic resources. Less than a third of participants’ families owned their own home, an important indicator of financial assets. Thus, Latinx adolescent males may be especially vulnerable to stress rooted in needs to establish an autonomous male identity within a U.S. context, while simultaneously maintaining traditional values of respect for parental authority and family connection.

To put the advances in knowledge contributed by this study’s findings in context, study limitations are noted. By relying on two time points of data spaced only four to six months apart during one year of high school, it was not possible to examine changes in parenting dynamics over time, to identify reciprocity between parenting and adolescent adjustment, or to learn about the long-term associations between parenting and youth outcomes. Considering change in parenting dynamics over time was beyond the scope of this study, and future studies with more waves and more time between waves would be better suited to considering change and stability in parenting dynamics and reciprocity between parenting dynamics and youth outcomes. In terms of reciprocity, multiple time points of data might provide greater insight into the finding that boys were especially susceptible to the two parenting profiles that happen to be uniquely characterized by high homework monitoring. Perhaps parents’ high level of monitoring around homework occurred in response to boys and having difficulty getting school work completed. An additional limitation stems from the reliance on youth self-report data only; shared method variance may have resulted in overestimates of the associations between parenting and adolescent outcomes. This study also was limited with respect to inattention to gender dyads, such as mother/son, mother/ daughter, father/son, father/daughter, that influence parenting impacts on adolescent boys and girls (Chung et al. 2009; Dumka et al. 2009). Finally, it is important to note that this study’s findings may not generalize to Latinx families living in more longstanding immigrant destination areas and/or those who have resided in the United States for more generations than is shown for this sample of mostly second-generation immigrant youth.

A critical next step in research on this topic is a focus on the larger cultural context within which autonomy-related parenting processes unfold. Prior research supports the salience of cultural factors to Latino parenting (Calzada et al. 2010). Cultural values including familismo, emphasizing the primacy of family cohesion and obligations, and respeto, stressing the importance of youth obeying and respecting parents’ authority, correlate with higher levels of parental behavioral control and monitoring (Davis et al. 2015; Taylor et al. 2012) and with less family and parent-child conflict (Lorenzo-Blanco et al. 2012). Using latent profile analysis, some researchers have found patterns of co-variation between parenting behaviors, including monitoring, and culture-specific variables, such as parents’ socialization emphasizing respeto (Kim et al. 2018) or family values emphasizing familismo (Ayón et al. 2015). As part of the cultural context, it also is valuable to consider acculturation-related stressors, particularly for families living in new immigrant destinations, where there exist few Spanish language supports or co-ethnic enclaves (Ebert and Ovink 2014). Research conducted with Latinx early adolescents, for example, has shown that parental monitoring may buffer youth from the negative impacts of acculturation stress on youth problem behaviors (Hurwich-Reiss and Gudiño 2016). By incorporating information about acculturation, cultural socialization, and cultural values into the study of both monitoring and conflict, it will be possible to gain a more finely tuned understanding of the complex parenting processes informative about youth’s negotiation of autonomy vis-à-vis the cultural context experienced by Latinx families.

Conclusion

This short-term longitudinal study addressed the need for research indicating how co-varying autonomy-related parenting processes are associated with the adjustment of teens in Latinx families who immigrated to the U.S. The study’s findings advance the literature by identifying three unique types of parenting styles defined by monitoring and parent-youth conflict and indicating how these parenting typologies relate to youth’s academic success and depression concurrently and over the school year. The combination of high monitoring and low conflict was associated with higher grades and fewer depressive symptoms in bivariate analyses focused on within-time associations and in prospective analyses across the school year, especially for boys. By exploiting heterogeneity in parenting styles as a function of different types of monitoring behaviors and conflicts, this research provides some needed insight into the complexity of associations between parenting styles and outcomes among Latinx youth. Middle adolescence may be a critical window of development during which time youth’s school performance and mental health are especially sensitive to autonomy-related parenting dynamics. Family-based preventive interventions for Latinx families who immigrated to the U.S. would be well served to ensure that parents engage in solicitation and limit-setting behaviors in ways that minimize parent–adolescent conflicts. Future research must consider the co-occurrence of both parent–child conflicts and parental monitoring behaviors when seeking to understand parenting dynamics tied to Latinx adolescent adjustment.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the families for their participation in the project.

Funding

This research was supported by the Springboard Grants Program (Roche) at the Milken Institute School of Public Health, The George Washington University.

Biographies

Kathleen M. Roche MSW, PhD is an Associate Professor in the Department of Community and Preventive Health at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at The George Washington University. Her research examines cultural and contextual variations in parenting influences on adolescent adjustment, particularly for adolescents in Latinx immigrant families.

Sharon F. Lambert PhD is an Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology in the Department of Psychology at The George Washington University. Her research focuses on the development and course of depressive symptoms in urban and ethnic minority adolescents, neighborhood and race-related stress, and school-based prevention.

Rebecca M. B. White PhD, MPH is an Associate Professor at Arizona State University. Her major research interests include neighborhood effects on adolescent development with a special focus on adolescents from groups that experience marginalization.

Esther J. Calzada PhD is an Associate Professor at the University of Texas. Her work focuses on the construct of acculturation in immigrant and second-generation Latino families and the relation between acculturation and parenting practices in parents of preschoolaged children. Outcome variables of interest are related to behavioral development in young children.

Todd D. Little PhD is a Professor of Educational Psychology and Leadership and founding Director of the Institute for Measurement, Methodology, Analysis and Policy (immap.educ.ttu.edu) at Texas Tech University. His quantitative work focuses on various aspects of applied SEM (e.g., indicator selection, parceling) as well as substantive developmental research examining action-control processes and motivation, coping, and self-regulation.

Gabriel P. Kuperminc PhD is a Professor of Psychology and Public Health at Georgia State University. His research is focused on understanding processes of resilience and positive youth development in adolescence and evaluating the effectiveness of community-based prevention and health promotion programs.

John E. Schulenberg PhD is a Professor at the University of Michigan. His research concerns the etiology and epidemiology of drug and alcohol use across adolescence and the transition to adulthood, and the impact of developmental transitions on trajectories of health and well-being.

Footnotes

Data Sharing and Declaration The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest T.L. owns Yhat Enterprises, LLC, which operates his stats camps (statscamp.org). The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Anderson RJ, & Branstetter SA (2012). Adolescents, parents, and monitoring: A review of constructs with attention to process and theory. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4, 1–19. 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2011.00112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Augenstein TM, Thomas SA, Ehrlich KB, Daruwala S, Reyes SM, Chrabaszcz JS, & De Los Reyes A. (2016). Comparing multi-informant assessment measures of parental monitoring and their links with adolescent delinquent behavior. Parenting: Science and Practice, 16, 164–186. 10.1080/15295192.2016.1158600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, Williams LR, Marsiglia FF, Ayers S, & Kiehne E. (2015). A latent profile analysis of Latino parenting: The infusion of cultural values on family conflict. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services, 96, 203–210. 10.1606/1044-3894.2015.96.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bámaca-Colbert MY, Gayles J, & Lara R. (2011). Family correlates of adjustment profiles in Mexican-origin female adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 33, 123–151. 10.1177/0739986311403724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bámaca-Colbert MY, Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Gayles J. (2012). A developmental-contextual model of depressive symptoms in Mexican-origin female adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 48, 406–421. 10.1177/0739986311403724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR, & Trost K. (2006). The person-oriented versus the variable-oriented approach: Are they complementary, opposites, or exploring different worlds? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52, 601–632. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/mpq/vol52/iss3/10. [Google Scholar]

- Blocklin MK, Crouter AC, Updegraff KA, & McHale SM (2011). Sources of parental knowledge in Mexican American families. Family Relations, 60, 30–44. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Prelow HM, Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Michaels ML, & Tein J. (2002). Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents’ distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family, and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 135–152. 10.1002/jcop.10000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen KA& Long JS(Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Buuren SV, & Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. (2011). mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–67. 10.18637/jss.v045.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Fernandez Y, & Cortes DE (2010). Incorporating the cultural value of respeto into a framework of Latino parenting. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority. Psychology, 16, 77–86. 10.1037/a0016071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016). 1991–2015 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/.

- Trends Child, Inc. (2017). Child Trends’ calculations using U.S. Census Bureau (2017). School enrollment in the United States: October - detailed Tables. https://www.census.gov/topics/education/school-enrollment/data/tables.html.

- Chung GH, Flook L, & Fuligni AJ (2009). Daily family conflict and emotional distress among adolescents from Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1406–1415. 10.1037/a0014163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, & Steinberg L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 1113, 487–496. 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AN, Carlo G, & Knight GP (2015). Perceived maternal parenting styles, cultural values, and prosocial tendencies among Mexican American youth. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 176, 235–252. 10.1080/00221325.2015.1044494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Bonds DD, & Millsap RE (2009). Academic success of Mexican-origin adolescent boys and girls: The role of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and cultural orientation. Sex Roles, 60, 588–599. 10.1007/s11199008-9518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL (2010). Children’s provision of family caregiving: Benefit or burden? Child Development Perspectives, 4, 55–61. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert K, & Ovink SM (2014). Anti-immigrant ordinances and discrimination in new and established destinations. American Behavioral Scientist, 58, 1784–1804. 10.1177/0002764214537267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A, Loukas A, & Pasch KE (2018). Examining the bidirectional associations between adolescents’ disclosure, parents’ solicitation, and adjustment problems among non-Hispanic White and Hispanic early adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 1–15. 10.1007/s10964-018-0896-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Frey WH (2015). Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics are Remaking America. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Golden RM (2000). Statistical tests for comparing possibly mis-specified and non-nested models. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 44, 153–170. 10.1006/jmps.1999.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Peck SC, Malanchuk O, Sameroff AJ, & Eccles JS (2017). Chapter 8 Family characteristics. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 82, 114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth LC, Ispa JM, & Rudy D. (2006). Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development, 77, 1282–1297. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard WJ, Little TD, & Rhemtulla M. (2015). Using principal component analysis (PCA) to obtain auxiliary variables for missing data estimation in large data sets. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 285–299. 10.1080/00273171.2014.999267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwich-Reiss E, & Gudiño OG (2016). Acculturation stress and conduct problems among Latino adolescents: The impact of family factors. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 4, 218–231. 10.1037/lat0000052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2016). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, & Wasserman L. (1995). A reference Bayesian test for nested hypotheses and its relationship to the Schwarz criterion. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90, 928–934. 10.1080/01621459.1995.10476592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kagitcibasi C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 403–422. 10.1177/0022022105275959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kakihara F, & Tilton-Weaver LC (2009). Adolescents’ interpretations of parental control: Differentiated by domain and types of control. Child Development, 80, 1722–38. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keijsers L, Frijns T, Branje SJT, & Meeus W. (2009). Developmental links of adolescent disclosure, parental solicitation and control with delinquency: Moderation by parental support. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1314–1327. 10.1037/a0016693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H, & Burk WJ (2010). A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 39–64. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00623.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Chen S, Hou Y, Zeiders KH, & Calzada EJ (2018). Parental socialization profiles in Mexican-origin families: Considering cultural socialization and general parenting practices. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 10.1037/cdp0000234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kuperminc GP, Jurkovic GJ, & Casey S. (2009). Relation of filial responsibility to the personal and social adjustment of Latino adolescents from immigrant families. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(1), 14–22. 10.1037/a0014064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, Unger JB, Basanez T, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, & Baezconde-Garbanati L. (2011). Marijuana use among Latino adolescents: Gender differences in protective familial factors. Substance Use & Misuse, 46, 644–655. 10.3109/10826084.2010.528121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang KM, & Little TD (2015). The supermatrix technique: Simple framework for hypothesis testing with missing data. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38, 461–470. 10.1177/0165025413514326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang KM, Little TD, & PcAux development team (2017). PcAux: Automatically extract auxiliary variables for simple, principled missing data analysis. R package version; 0.0.0.9004. http://github.com/PcAux-Package/PcAux. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, & Collins W. (2009). Parent-child relationships during adolescence. In Lerner RM& Steinberg L(Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 3–42). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen BP, & Hoff E. (2006). Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52, 377–389. 10.1353/mpq.2006.0029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti F, Palladino BE, Passini CM, Casonato M, Hamzallari O, Ranta M, Dellagiulia A, & Keijsers L. (2018). The development of parental monitoring during adolescence: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 10.1080/17405629.2018.1476233. [DOI]

- Little TD (2013). Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, & Rhemtulla M. (2013). Planned missing data designs for developmental researchers. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 199–204. 10.1111/cdep.12043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell N, & Rubin D. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767–778. 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, & Burke JD (2011). Developmental pathways in juvenile externalizing and internalizing problems. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 34–46. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Tamayo R, Robinson WL, Lambert SF, Jason LA, & Ialongo NS (2016). Parental monitoring, association with externalized behavior, and academic outcomes in urban African American youth: A moderated mediation analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57, 366–379. 10.1002/ajcp.12056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Ritt-Olson A, & Soto D. (2012). Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in Hispanic youth: The roles of gender, Hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1350–1365. 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson D. (2003). The person approach: Concepts, measurement models, and research strategy. New Directions in Child Development, 3–23. 10.1002/cd.79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McConnell ED (2015). Hurdles or walls? Nativity, citizenship, legal status and Latino homeownership in Los Angeles. Social Science Research, 53, 19–33. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, & Muthén L. (1998). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nair R, Roche KM, & White RBM (2018). Acculturation gap distress among Latino youth: Prospective links to family processes and youth depressive symptoms, alcohol use, and academic performance. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 47, 105–120. 10.1007/s10964-017-0753-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14, 535–569. 10.1080/10705510701575396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odem ME (2008). Unsettled in the suburbs: Latino immigration and ethnic diversity in metro Atlanta. In Singer A, Hardwick SW& Brettell CB(Eds.) Twenty-first century gateways: Immigrant incorporation in suburban America. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pasch LA, Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E, Penilla C, & Pantoja P. (2006). Acculturation, parent-adolescent conflict, and adolescent adjustment in Mexican-American families. Family Process, 45, 75–86. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Deeb-Sossa N, Harris KM, & Bollen K. (2005). What are we measuring? An evaluation of the CES-D across race/ ethnicity and immigrant generation. Social Forces, 83, 1567–1602. 10.1353/sof.2005.0077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J, Ong A, & Madden T. (2000). Cultural values and intergenerational value discrepancies in immigrant and non-immigrant families. Child Development, 71, 528–539. 10.1111/1467-8624.00162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett SW, & Bámaca-Gómez MY (2003). The relationship between parenting, acculturation, and adolescent academics in Mexican-origin immigrant families in Los Angeles. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 222–239. 10.1177/0739986303025002005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett SW, Behnke AO, Sands T, & Choi BY (2009). Adolescents’ reports of parental engagement and academic achievement in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 257–268. 10.1007/s10964-008-9325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics (2014). Qualtrics software, Qualtrics Research Suite. Qualtrics, Provo, UT. http://www.qualtrics.com. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhemtulla M, Jia F, Wu W, & Little TD (2014). Planned missing designs to optimize the efficiency of latent growth parameter estimates. International Journal of Behavior Development, 1–12. 10.1177/0165025413514324. [DOI]

- Robin AL, & Foster SL (1989). Negotiating Parent-Adolescent Conflict: A Behavioral-Family Systems Approach. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, Little TD, Ghazarian SR, Lambert SF, Calzada EJ, & Schulenberg J. (2018). Parenting processes and adolescent adjustment in immigrant Latino families: The use of residual centering to address the multicollinearity problem. Journal of Latino/a Psychology, early view available online February 22. 10.1037/lat0000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD (2002). Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 3–13. 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago C, Gudiño OG, Baweja S, & Nadeem E. (2014). Academic achievement among immigrant and U.S.-born Latino adolescents: Associations with cultural, family, and acculturation factors. Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 735–747. 10.1002/jcop.21649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG (1995a). Conflict and coordination in adolescent-parent relationships. In Schulman S(Ed.), Close relationships and socioemotional development (pp. 155–184). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG (1995b). Parenting styles and conceptions of parental authority during adolescence. Child Development, 66, 299–316. 10.2307/1131579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG (2006). Social-cognitive domain theory: Consistencies and variations in children’s moral and social judgments. In Killen M& Smetana JG(Ed.), Handbook of moral development (pp. 19–154). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, & Daddis C. (2002). Domain-specific antecedents of parental psychological control and monitoring: The role of parenting beliefs and practices. Child Development, 73, 563–580. 10.1111/1467-8624.00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Rose RA, & Bacallao M. (2008). Acculturation and Latino family processes: How cultural involvement, biculturalism, and acculturation gaps influence family dynamics. Family Relations, 57, 295–308. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00501.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, & Kerr M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085. 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ZE, Larsen-Rife D, Conger RD, & Widaman KF (2012). Familism, interparental conflict, and parenting in Mexican-origin families: A cultural-contextual framework. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 312–327. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. (1983). The Development of Social Knowledge: Morality and Convention. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Zeiders KH, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Perez-Brena NJ, Wheeler LA, & Rodríguez De Jesús SA (2014). Mexican-American adolescents’ gender role attitude development: The role of adolescents’ gender and nativity and parents’ gender role attitudes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 2041–53. 10.1007/s10964-014-0128-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorn MD, Branje SJT, & Meeus WHJ (2011). Developmental changes in conflict resolution styles in parent–adolescent relationships: A four-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 97–107. 10.1007/s10964-010-9516-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos-Solis M, Smetana JG, & Tasopoulos-Chan M. (2016). Evaluations of conflicts between Latino values and autonomy desires among Puerto Rican adolescents. Child Development, 88, 1581–1597. 10.1111/cdev.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weymouth BB, Buehler C, Zhou N, & Henson RA (2016). A meta-analysis of parent-adolescent conflict: Disagreement, hostility, and youth maladjustment. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8, 95–112. 10.1111/jftr.12126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler LA, Updegraff K, & Crouter A. (2015). Mexican-origin parents’ work conditions and adolescents’ adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 29, 447–457. 10.1037/fam0000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]