Abstract

Aurora kinase A (Aurora-A), a serine/threonine kinase, plays a pivotal role in various cellular processes, including mitotic entry, centrosome maturation and spindle formation. Overexpression or gene-amplification/mutation of Aurora-A kinase occurs in different types of cancer, including lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer. Alteration of Aurora-A impacts multiple cancer hallmarks, especially, immortalization, energy metabolism, immune escape and cell death resistance which are involved in cancer progression and resistance. This review highlights the most recent advances in the oncogenic roles and related multiple cancer hallmarks of Aurora-A kinase-driving cancer therapy resistance, including chemoresistance (taxanes, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide), targeted therapy resistance (osimertinib, imatinib, sorafenib, etc.), endocrine therapy resistance (tamoxifen, fulvestrant) and radioresistance. Specifically, the mechanisms of Aurora-A kinase promote acquired resistance through modulating DNA damage repair, feedback activation bypass pathways, resistance to apoptosis, necroptosis and autophagy, metastasis, and stemness. Noticeably, our review also summarizes the promising synthetic lethality strategy for Aurora-A inhibitors in RB1, ARID1A and MYC gene mutation tumors, and potential synergistic strategy for mTOR, PAK1, MDM2, MEK inhibitors or PD-L1 antibodies combined with targeting Aurora-A kinase. In addition, we discuss the design and development of the novel class of Aurora-A inhibitors in precision medicine for cancer treatment.

Key words: Aurora-A, Therapy resistance, Chemoresistance, Targeted therapy, Radioresistance, Synthetic lethality, Alisertib, PROTAC

Graphical abstract

This review highlights the most recent advances in Aurora-A-mediated cancer therapy resistance (chemoresistance, targeted therapy resistance, endocrine therapy resistance and radioresistance) and summarizes the synthetic lethality and combinational strategy for targeting Aurora-A kinase in precision medicine for cancer treatment.

1. Introduction

In normal cells, Aurora-A executes a series of critical mitotic events, including centrosome maturation, mitosis entry, mitotic spindle formation and cytokinesis1. However, Aurora-A is closely related to tumorigenesis through its amplification and/or overexpression in human cancers2. It has been concluded that Aurora-A plays multiple roles in regulating tumor development and progression by facilitating cell-cycle progression, activating cell survival and anti-apoptosis/or necroptosis signaling, inducing genomic instability, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stem cells (CSCs)2,3. In recent studies, some novel cancer hallmarks have been found to regulate tumor progression and therapy resistance associated with alteration of Aurora-A kinase.

The types of cancer treatment including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy aim to eliminate/or suppress effectively cancer cells for patients, but in some patients, the remaining cancer cells become therapy resistant, which lead to life-threatening recurrence and metastasis4, 5, 6. Cancer therapy resistance is usually characterized by a poor prognosis. Therefore, it is urgent to clarify the potential molecular mechanisms of therapy resistance and investigate potential therapeutic/combinational approaches based on the molecular mechanisms6. In recent years, the molecular mechanisms of Aurora-A mediated cancer therapy resistance have been increasingly reported in various malignancies. Thus, we will summarize the biological role of Aurora-A kinase in human cancer hallmarks, especially focus on the development of resistance to radiotherapy, chemotherapy and targeted therapy through modulating DNA damage repair, feedback activation bypass pathway, apoptosis, necroptosis, autophagy, DNA damage repair, metastasis and stemness. Meanwhile, we will also highlight the most recent advances in the potential synthetic lethality and combinational strategy of targeting Aurora-A in precision medicine for cancer treatment.

2. The biological function of Aurora-A kinase

Aurora kinases, firstly discovered in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and named Ipl1 (increase in ploidy 1) in 1993, were evolutionally conserved C-terminal serine/threonine kinase domain in various eukaryotic organisms7. In mammals, the Aurora kinase families have three members: Aurora-A (AURKA), Aurora-B (AURKB) and Aurora-C (AURKC). The genes encoding human Aurora-A, B and C are located on chromosome 20q13.2–q13.3, 17p13.1 and 19q13.43, respectively8, 9, 10. Although these three Aurora kinases are similar in structure, their expression patterns, cellular localization and physiological functions are entirely different (Fig. 1A). Aurora-A is activated and localized into the centrosomes at the G2 phase, then translocated to mitotic spindles during prometaphase and metaphase11,12. Aurora-A regulates mitotic entry, centrosome maturation and spindle formation, and degrades after metaphase–anaphase transition13.

Figure 1.

The structure and expression of Aurora-A kinase. (A) Schematic diagram of the domain structure of Aurora kinases. The catalytic domain of Aurora-A, Aurora-B, and Aurora-C is highly conserved (all gray junction region). Autophosphorylation of Thr287/288 in the activation loop (also known as the “T-loop”) of Aurora-A is required for activation of its kinase activity. A short amino acid peptide motif called a “destruction box” (D-box) is present in the carboxy-terminal region of Aurora-A, Aurora- B, and Aurora-C. Aurora-A has the amino terminal “D-box-activating domain box (A-Box)” required for D-box functional activation. (B) The expression of Aurora-A kinase in human tissues; (C) The alteration of Aurora-A in human cancer. According to TCGA combined database, overexpression (gene amplification) and mutation of AURKA occur in various types of human cancer, including lung cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, etc.

2.1. The expression of Aurora-A in human tissues

As shown in Fig. 1B, the expression levels of the AURKA gene and protein were enriched in bone marrow & lymphoid and testis tissues; moderately expressed in colon, lung, stomach, liver and ovary tissues; and the expressions of AURKA gene and protein were not detected in thyroid, pancreas, smooth muscle, skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, spleen, and prostate tissues. Data was obtained from The Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/; accessed on November 2022).

2.2. Activation, regulation of Aurora-A-manipulated signaling pathways

The activation of Aurora-A includes its serine/threonine phosphorylation site to phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation, and auto-phosphorylation procession. Aurora-A phosphorylated at Thr288 (and possibly Thr287) could down-regulate kinase activity through phosphorylation at Ser342, whereas Aurora-A phosphorylated on Thr288 could also up-regulate kinase activity through phosphorylation of Ser8914,15. The activity of Aurora-A depends on its phosphorylation Thr288 on the activation loop (Asp274–Glu299) of the kinase, which is also called “T-loop” (Fig. 1A).

The effect of Aurora-A could be activated by co-factor Bora, Ajuba, PPI-2 (protein phosphatase inhibitor-2), PAK1 (p21-activated kinase 1), and TPX2 (target protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2), and deactivated by PP2A (protein phosphatase 2A) in human cancer. KCTD12 (potassium channel tetramerization domain containing 12) and Cdk1 (cyclin-dependent kinase 1) appear to activate Aurora-A in the form of positive feedback loop9,16, 17, 18. And, ubiquitin-specific peptidase 3 (USP3) could promote deubiquitination of Aurora-A19. The best-characterized regulator of Aurora-A is the microtubule-binding protein TPX2. Aurora-A and TPX2 are co-expressed in the cell cycle progression, and the complex might be used as a novel holoenzyme20. Mutation or overexpression of Aurora-A led to the increased auto-phosphorylation and allosteric activation after binding to TPX2, and then promoted downstream pathways, such as oncogenic MYC21,22. Additionally, Aurora-A kinase was activated in an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2-dependent manner through the C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) and C–X–C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) pathway in human glioblastoma. The CXCL12-ERK1/2 signaling induces Ajuba expression, leading to auto-phosphorylation of Aurora-A at Thr28823.

Aurora-A is a crucial regulatory constituent of the p53 pathway, especially in the checkpoint-reaction pathway necessary for the oncogenic transformation through phosphorylation and stabilization of p5324. Recently, Aurora-A was found to regulate Yes-associated protein (YAP)-mediated transcriptional activity, which is a downstream effector in the Hippo pathway. Aurora-A seemed to interact with YAP, mainly locating into the nucleus, where the higher expression of YAP was closely related to the proliferation in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)25. In addition, Aurora-A could also phosphorylate other target proteins, including CDC25B (cell division cycle 25 homolog B), HDAC6 (histone deacetylase 6), KIF2A (kinesin family member 2A), LATS2 (large tumor suppressor 2), RASSF1 (ras-association domain family member 1) and TACC3 (transforming acidic coiled-coil protein 3)26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34. These targets could activate multiple pathways, such as AKT (protein kinase B), STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) and NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B), promote cell survival and proliferation, inflammation, self-renewal, angiogenesis, metastasis, and induce tumor malignancy and resistance.

2.3. Redox regulation of Aurora-A

Aurora-A kinase is hyper-phosphorylated in the early phase of mitosis under oxidative stress that might interfere with the function of Aurora-A in mitotic spindle formation35. The redox-sensitive cysteine residues of the Aurora-A domain were depicted by the X-ray crystal structure analysis36. These residues could allosterically regulate kinase activity after covalent modification. Among them, a conserved cysteine residue Cys290 is essential for Aurora-A activation by auto-phosphorylation on Thr28835,36. The catalytic activity of Aurora-A is also strictly controlled by a specific and reversible oxidative modification of Cys290, which locates adjacent to Thr288 on T-loop35. Moreover, a new Aurora-A regulatory mechanism was achieved by CoA modification under cell reaction to oxidative stress37. CoA locks Aurora-A in an inactive state through a unique “dual anchor” inhibitory mechanism, including covalent modification of Cys290 through the thiol group of pantetheine tail, and selective binding of ADP moiety of CoA to ATP binding pocket of Aurora-A. Thus, the covalent modification of Aurora-A by CoA is specificity, and could be induced by redox.

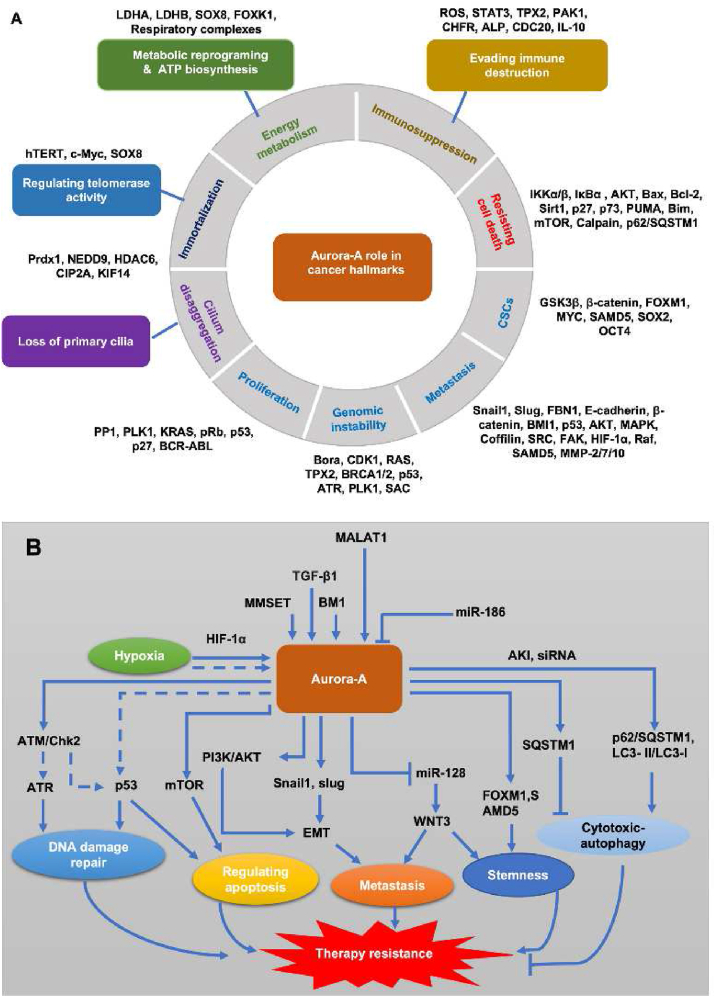

3. The role of Aurora-A in human cancer hallmarks and cancer acquired resistance

Overexpression (gene amplification) and mutation of AURKA occur in various types of human cancer2,38, including lung cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer. According to the TCGA database, 12.73% amplification and 1.82% mutation of AURKA was measured in human lung cancer; 3.11% (164/5280 cases) amplification and 0.81% mutation of AURKA was detected in human colorectal cancer; 3.48% (183/5265 cases) amplification and 0.38% of AURKA was found in human breast cancer (Fig. 1C). Overexpression or gene-amplification/mutation of Aurora-A kinase not only increased susceptibility in carcinogenesis and caused cancer drug resistance. To date, the role of Aurora-A in cancer hallmarks and mediated cancer therapy resistance have been increasingly reported in various malignancies. In addition to proliferation, the role of Aurora-A kinase in the regulation of telomerase activity, reprogramming energy metabolism and ATP biosynthesis, evading immune destruction, primary cilium disaggregation, resistance cell death, EMT and metastasis, and cancer stem cells were system summarized (Fig. 2A). The related cancer hallmarks, especially resistance cell death, in Aurora-A-mediated cancer acquired resistance were also addressed (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

The role of Aurora-A in human cancer hallmarks and cancer acquired resistance. (A) Aurora-A plays multiple roles in regulating tumor development and progression by facilitating cell-cycle progression, activating cell survival and anti-apoptosis or necroptosis signaling, inducing genomic instability, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stem cells (CSCs). In recent studies, some novel cancer hallmarks have been found to regulate tumor progression associated with Aurora-A kinase; (B) Mechanisms of Aurora-A-mediated cancer acquired resistance. Aurora-A kinase on producing the resistance to radiotherapy, chemotherapy and targeted therapy via modulating DNA damage repair, feedback activation bypass pathway, apoptosis, metastasis, stemness and autophagy.

3.1. Aurora-A kinase regulates telomerase activity

It is generally believed that telomerase reactivation is related to carcinogenesis and is a critical step in tumor immortalization39,40. A study revealed that ectopic Aurora-A expression induced telomerase activity in human ovarian HIOSE118 and breast epithelial MCF10A cell lines41. Meanwhile, Aurora-A significantly stimulated the mRNA and promoter activities of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), which was related to the up-regulation of c-Myc by the ectopic Aurora-A expression. The c-Myc binding sites of the hTERT promoter were essential for the hTERT promoter activity induced by Aurora-A41. Furthermore, Aurora-A enhanced the hTERT activity by directly binding to the transcription factor sex-determining region Y-box 8 (SOX8) and phosphorylation in ovarian cancer42.

3.2. Reprogramming energy metabolism and ATP biosynthesis

Glucose metabolic reprogramming is an emerging hallmark of malignant cancer cells. Otto Warburg first discovered an abnormal characteristic of cancer cell energy, called “aerobic glycolysis”40,43,44. In p53-deficient cancer cells, overexpression of Aurora-A directly binds to lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) B and inhibits the reverse reaction of LDHB. Aurora-A phosphorylated LDHB at Ser162 to reduce substrate-inhibition, leading to increased lactate production and NAD+ regeneration, and promotes glycolysis45. Glycolytic phenotypes were significantly enhanced with the up-regulation of Aurora-A, whereas Aurora-A knockdown resulted in a decrease of glycolysis-related proteins, like LDHA and hexokinase 2 (HK2)42. Moreover, Aurora-A directly bound with SOX8 in the nucleus and activated it through phosphorylation at Ser327. The binding of SOX8 with FOXK1 (forkhead/winged helix family k1) promoter facilitated the glycolysis by upregulation of LDHA and HK2 expressions42. Additionally, mitochondrial network reshapes could meet the increasing energy requirements of cancer cells46. Interphasic Aurora-A is imported into the mitochondrial matrix through its N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS)47. Transmission electron microscopy analyses show that when Aurora-A was overexpressed, mitochondria interconnectivity would increase, but no apparent signs of intra-mitochondrial content loss. Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that overexpression of Aurora-A induced the levels of respiratory complex IV subunits. Meanwhile, the interactome analysis of Aurora-A by proteomics revealed that Aurora-A directly interacts with multiple subunits of all respiratory complexes. The increased abundance and activity of respiratory complexes depend on oxidative phosphorylation to produce ATP48. The above results indicate that overexpressed Aurora-A affects the mitochondrial respiratory chain, increasing ATP production47. Therefore, overexpression of Aurora-A could enhance the glycolytic flux and ATP biosynthesis, further facilitate cancer cell proliferation.

3.3. Evading immune destruction

Immunogenic cancer cells are likely to escape immune destruction by deactivating immune system components dispatched initially to eliminate them40. For example, cancer cells exhibit actively immunosuppressive by recruiting inflammatory cells, including myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs), which can inhibit the response of cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTL)49,50. Using Aurora-A inhibitor alisertib (MLN8237) to evaluate the immunosuppressive microenvironment dominated by MDSC and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in immune-competent mammary tumor mice models, resulted in a significant reduction of MDSC and TAM populations after alisertib treatment51. The inhibition of Aurora-A selectively induced intensive cancer cell apoptosis, disrupted the immunosuppressive and tumor-promoting functions of MDSCs, but protected T cells from apoptosis. The transcriptomic analysis found that p-STAT3 was significantly suppressed in MDSCs isolated from alisertib-treated mice, indicating that alisertib might prevent immunosuppression of MDSCs by blocking Aurora-A/STAT3 signaling51.

The inhibition of Aurora-A activity by alisertib or AURKA gene knockout may increase the population of intratumoral CD8+ T cells in tumors52. CD8+ T cells could predict the overall survival rate of patients with colorectal cancer, and the infiltration and activation of CD8+ T cells improve the prognosis of patients. CD8+ T cells isolated from alisertib-treated cancers found that the level of IL-10Rα mRNA was significantly upregulated, resulting in an enhancement in IL-10 production. In the migration assay, IL-10 secreted by cancer cells indeed recruited tumor-specific CD8+ T cell infiltration52. Consequently, Aurora-A evades immune destruction in tumors, which might be related to STAT3 signaling and promoted IL-10 secretion in cancer cells.

3.4. Primary cilium disaggregation

The loss of primary cilia has been recently correlated with various tumors, such as squamous cell carcinoma, renal cancer and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma53. Aurora-A, a marker protein of cilium disaggregation, induces primary cilia disassembly54. Aurora-A could mediate the regulation of peroxiredoxin1 (PRDX1) signaling of cilium disaggregation and affects the tumor formation in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma34. Aurora-A was phosphorylated by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activation, leading to the loss of primary cilia during oral mucosa carcinogenesis55. Furthermore, the cancerous inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A (CIP2A), a characteristic human oncoprotein, located in the centrosome, forms a complex with Aurora-A, and further regulates cilia disassembly through the activation of Aurora-A56. The activity of Aurora-A also acts as a downstream mediator of at least some of the primary cilium defects associated with kinesin family member 14 (KIF14) depletion, and KIF14 is considered to be an important element connecting effective ciliogenesis57.

3.5. Resistance to cell death

3.5.1. Apoptosis

Induction of apoptosis is one of the primary mechanisms of chemotherapeutic drugs and irradiation kill cancer cells. While many types of cancer cell acquired resistance to apoptosis, leading to cancer drug resistance58. Aurora-A has been found to promote cell proliferation through mTOR activation in TNBC cells59. Silencing Aurora-A resulted in a significant reduction of p-mTOR in Aurora-A overexpressed TNBC cells, suggesting that Aurora-A positively regulates p-mTOR expression59. In the epigenetic processes study, histone methyltransferase multiple myeloma SET domain protein (MMSET) methylated N-terminal region of Aurora-A at K14 and K117 methylation sites60. The methylation of Aurora-A reduced p53 stability through proteasomal degradation and inducing cell proliferation and suppressing cell apoptosis. Moreover, suppression of Aurora-A activity by alisertib activated the calpain signaling, and induced apoptosis through p27 degradation and Bax cleavage in gastric cancer cells61.

3.5.2. Necroptosis

Aurora-A could inhibit necroptosis, which might be used as a local inhibitor to directly interact with receptor-interacting serine/threonine kinase (RIPK) 1 or RIPK3 in pancreatic cancer62. Aurora-A phosphorylated glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) at serine 9, which interfered with the formation of RIPK3 and mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) complex, reduced necrosome activation and hindered necroptosis62. Thus, the alteration of Aurora-A kinase resulted in resistance to necroptosis-mediated cell death.

3.5.3. Autophagy

Accumulating evidence shows that autophagy plays a critical role in chemoresistance. Chemotherapeutic agents induce cytotoxic autophagy, enhancing drug-sensitivity and cellular apoptosis. However, autophagy also exerts its cytoprotective effect through degrading drug molecules63. Aurora-A was related to the expression of autophagy-associated protein SQSTM1 in breast cancer64. The depletion or inhibition of Aurora-A reduced SQSTM1 and induced cytotoxic-autophagy. Pharmacological inhibitors of autophagy (BAF or chloroquine) also enhanced cytotoxicity by depletion or inhibition of Aurora-A64. Additionally, with alisertib treatment, the expression of p62/SQSTM1 and LC3B significantly elevated, thereby facilitating cytotoxic-autophagy65. In pancreatic cancer cells, AURKA-depletion using siRNA led to autophagic-cell death, accompanied by LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and p62/SQSTM1 accumulation66. Furthermore, Aurora-A inhibited autophagy by protecting the protein stability of the transcription co-factor YAP in lung cancer67.

3.5.4. DNA damage repair

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are well-known DNA-damaging inducers, which activate the DNA damage response (DDR) and subsequently induce cancer cell apoptosis or death68. However, the sustained induction of the DDR is frequently limited, attributed to the resistance of cancer cells to DNA-damaging anticancer therapy. Aurora-A is a downstream target of DNA damage triggering pathways, and its function is also affected by DNA damage at multiple levels69. DNA damage directly repressed Aurora-A activity and perturbed the interaction with Bora. However, a forced fusion of Aurora-A to Bora under DNA damage results in phosphorylation of DNA damage checkpoint Plk1, and then activated G2 phase. Consistently, Aurora-A was activated by ectopically expressing overrides DNA damage signals facilitated bypassing the G2 arrest70. Additionally, Aurora-A activated ATM/CHK2 to dysregulate the DDR molecules, such as ATM, ATR and p53, resulting in tumor progression71. Besides, the function of Aurora-A was counteracted by BRCA1/2 to suppress DDR and cell cycle checkpoints signaling, and enhanced sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy71,72.

3.6. EMT and metastasis

Tumor metastasis exhibits resistance to cancer therapy, and EMT is the initial stage of solid tumor metastasis73. Aurora-A is highly expressed in liver metastases of colorectal cancer patients74. The overexpression of Aurora-A contributes to the increased expressions of EMT-related transcription factors Snail1 and Slug, and down-regulated expression of epithelial marker E-cadherin, indicating that Aurora-A induces the EMT process74. Meanwhile, Aurora-A was up-regulated by BMI1, a member of the chromatin-modifying protein polycomb group, by stabilizing the expression of Snail1 to promote the occurrence of EMT, and subsequently enhanced the migration and invasion in HNSCC cells75. A recent study revealed that Aurora-A could promote EMT and cancer metastasis through PI3K/AKT pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)76. The hypoxic induction of Aurora-A was dependent on HIF-1α by increasing the recruitment of HIF-1α to potential hypoxia-responsive elements (HREs) on AURKA promoter77. Notably, nuclear Aurora-A bound to HIF1α/β and up-regulated HIF-responsive genes (e.g., CXCR4 and MMP1), and further induced hypoxia signaling, like HIF-1α, NF-κB or TNF-α, which, in turn, led to hypoxia in breast cancer and promoted metastasis78.

3.7. Cancer stem cells

CSCs, a subpopulation of cancer cells with self-renewal and differentiation characteristics, are considered to be the basis of the malignant phenotypes. Increasing evidence indicates that current anticancer drugs do not effectively eliminate CSCs, consequently contributing to drug resistance79. Aurora-A was reported to be overexpressed and controlled the amount of centrosome amplification in human colorectal CSCs (CR-CSCs)80. Aurora-A knockdown could inhibit the proliferation of CR-CSCs and sensitize CR-CSCs to chemotherapy (5-FU or oxaliplatin)-induced cell death, accompanied by the down-regulation of anti-apoptotic factors80. Similarly, Aurora-A was also overexpressed in ovarian CSCs81,82. Through high-throughput drug sensitivity and resistance testing, alisertib was more cytotoxic to spheroid cells than some conventional chemotherapeutics agents, such as cytarabine and vincristine82. Nuclear-localized Aurora-A could enhance breast CSCs (BCSCs) phenotype, which possesses transactivation activity that binds and activates the MYC promoter. Perturbation Aurora-A nuclear translocation by shRNA promotes the anticancer efficacy and overcome resistant BCSCs83. Moreover, nuclear Aurora-A could recruit forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1) as a co-factor to drive FOXM1 activation-mediated positive feedback loop, thereby promoting the tumorigenesis of BCSCs. Aurora-A and FOXM1 inhibitors synergistically suppress BCSC self-renewal84. In addition, Raf (rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma)-1 mutant MCF7 cells were constructed to up-regulate Aurora-A showing activation of cancer stem cell markers and the nuclear localization of SMAD5 (small mother against decapentaplegic homolog 5). SMAD5-induced chemoresistance was associated with the maintenance of CD44+/CD24− cancer stem-like phenotypes85,86. The inhibition of Aurora-A kinase reduced p-SMAD5, further confirming the role of Aurora-A in modulating phosphorylation of SMAD5 and self-renewal ability86. In human breast cancer MCF7 cells, overexpression of Aurora-A inhibited endogenous miR-128, increased the expression of WNT3 protein, and induced the self-renewal and metastatic properties of breast cancer-initiating cells (BCIC)87.

4. Aurora-A and chemoresistance

Chemotherapeutic agents are still the first-line drugs for the treatment of most cancers, but the development of acquired resistant phenotype of cancer cells lead to clinical treatment failure. Overexpression of Aurora-A promotes chemoresistance including taxanes and cisplatin. Aurora-A also participates in autophagy which induced by some chemotherapy drugs such as cyclophosphamide. Understanding these mechanisms of Aurora-A-mediated chemoresistance will contribute to overcome cancer drug resistance and improve the efficacy of the conventional chemotherapy.

4.1. Taxanes resistance

Taxanes, including paclitaxel and docetaxel, are among the most successful anticancer agents for anticancer chemotherapy. However, the development of taxanes resistance is becoming increasingly common88,89. Taxanes act as anti-mitotic drugs by promoting tubulin polymerization, thereby disrupting mitosis and cell division, and ultimately leading to cell death90. Overexpression of Aurora-A in HeLa cells could lead to a striking increase in resistance to paclitaxel-induced apoptosis, suggesting that Aurora-A kinase could force paclitaxel resistance91. Additionally, the overexpression of Aurora-A enhanced paclitaxel resistance in MDA-MB-231 cells by up-regulating FOXM1. Aurora-A directly bound and attenuated the ubiquitination of FOXM192. The combination of Aurora-A inhibitor VX680 or thiostrepton targeting FOXM1 with paclitaxel could significantly restore the sensitivity of paclitaxel-resistant cells92.

It has been found that paclitaxel could induce the down-regulation of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2N (UBC13). The reduction of UBC13 increased Aurora-A levels and promoted paclitaxel resistance of ovarian cancer cells93. Besides, USP7 (ubiquitin-specific processing protease 7) was depleted by shRNA, causing Aurora-A to accumulate in laryngeal cancer HEp2 and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) H1299 cells, and desensitizing cancer cells to paclitaxel94. Besides, transforming growth factor beta1 (TGF-β1) could increase phosphorylated Aurora-A level, and develop docetaxel resistance strictly with the dependent on Aurora-A expression. The dual pharmacological targeted inhibition of TGF-β1 and Aurora-A pathway effectively reverses chemoresistance through down-regulating Snail195.

4.2. Cisplatin resistance

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy can improve the survival rate of patients with cancer, but its efficacy is limited due to drug resistance96. The higher expression of Aurora-A is correlated to the poor OS and progression-free survival (PFS) in NSCLC97,98. Overexpression of Aurora-A enhanced the cisplatin resistance, whereas the suppression of Aurora-A improved sensitivity to cisplatin in A549 cells. Aurora-A was also determined at a high protein level in A549/DDP (cisplatin-resistant variant) cells. Under the co-treatment of cisplatin and alisertib, the cell viability of A549/DDP cells was significantly decreased97. In ovarian cancers, cisplatin resistance is closely related to reducing cell senescence and increasing glucose metabolism. Aurora-A directly interacted with transcription factor SOX8 and activated its downstream target FOXK1, which could block senescence and improve glucose metabolism, further contributing to cisplatin resistance42.

4.3. Other chemoresistance

Recently, the induction of autophagy is associated with chemoresistance in various cancer treatments63. In lymphoma Raji cells, treatment with cyclophosphamide could induce autophagy and chemoresistance. However, treatment of alisertib reversed drug resistance and normalized the autophagy activity, indicating that switching autophagy by Aurora-A inhibition might play an important role in overcoming chemoresistance99. Moreover, Raf-1 mutant MCF7 cells induced constitutive activation of MAPK signaling and enhanced tumorigenicity, leading to daunorubicin resistance, whereas alisertib treatment could restore the sensitivity to daunorubicin in Raf-1 mutant MCF7 cells100.

5. Aurora-A and targeted therapy resistance

Currently, the major challenge to successful usage of targeted therapy is the development of acquired resistance, such as EGFR-TKIs. Aurora-A activation results in acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs, whereas EGFR inhibition in turn enhances the activation of Aurora-A. Pharmacological inhibition of Aurora-A kinase could restore the sensitivity of targeted therapeutics agents.

5.1. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

The application of small-molecule protein kinase inhibitors has become promising targeted therapeutics for cancer therapy. However, most of them usually produce an incomplete response followed by rapidly acquired resistance, such as EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)101. Aurora-A activation could contribute to acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs. Conversely, down-regulation of endogenous Aurora-A by siRNA significantly reduced gefitinib resistance in A549-p53-deficient cells102. Furthermore, EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma cells developed acquired resistance to the third-generation EGFR-TKIs (osimertinib), whereas EGFR inhibition contributed to Aurora-A activation during the establishment of acquired resistance103. As expected, EGFR-TKIs were sensitive to Aurora-A inhibition, and the combination of Aurora-A inhibitors and TKIs could induce apoptosis through up-regulation of Bcl-2-like protein 11 (BIM)103. Additionally, Aurora-A silencing by shRNA sensitized chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) KCL-22 or K562 cells to imatinib. The specific inhibitor of Aurora A, S1451, combined with imatinib, nilotinib or dasatinib, could provide a highly sensitive and lower toxic approach for the treatment of CML to prevent acquired resistance104. In addition, sorafenib is one of the most effective targeted therapies to improve the clinical prognosis of patients with advanced HCC. Unfortunately, the resistance of sorafenib is frequently observed105. Overexpression of MALAT1 (long non-coding RNA metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1) was found to reduce the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib and facilitated the progression of HCC, and MALAT1 regulated the mRNA and protein levels of Aurora-A, that is, MALAT1 silencing down-regulated the expression of Aurora-A. Inversely, overexpression of MALAT1 could up-regulate the level of Aurora-A106. Hence, it could be speculated that MALAT1 might affect sorafenib resistance through Aurora-A dependent manner. Recently, PI3K inhibitors have been approved for various cancers, such as buparlisib107. PI3K inhibitors have shown significant affected on patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) by blocking the proliferation pathway. However, some clinical trials have not observed the benefit to the prognosis of patients, because of the rapid development of acquired resistance to these inhibitors after administration108,109. In the establishment of PI3K inhibitor-resistant cell lines using patient-derived glioma spheroid-forming cell (GSC) xenografts, a combination of buparlisib and Aurora-A inhibitor GSK107016 effectively enhanced the sensitivity of drug-resistant GSC cells110.

5.2. Monoclonal antibody (mAb) resistance

Cetuximab is an anti-EGFR chimeric mAb that selectively binds to EGFR, and competitively blocks EGF or TGF-α, inhibits intracellular signal transduction pathways, and induces cancer cell apoptosis111. It has been proven effective against head and neck cancer, but cetuximab with a single treatment could produce drug resistance112. In squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), Aurora-A and EGFR were evaluated as highly expressed113. The combination of cetuximab and pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor R763 contributed to a significantly elevated percentage of apoptotic cells, indicating that co-targeting Aurora-A and EGFR could overcome the resistance to monotherapy in SCCHN cells113. In addition, the anti-human CD20 mAb rituximab combined with chemotherapy is an effective therapy for B-cell lymphoma (B-NHL)114. In B-NHL cells, the combination therapy of rituximab-alisertib-vincristine significantly enhanced cell apoptosis, and overcame resistance to monotherapy or dual therapy115.

5.3. Endocrine therapy resistance

Endocrine therapy suppresses the growth of endocrine-related tumors by blocking hormone receptor signaling pathways. In clinical samples, high levels of Aurora-A expression were detected, and the Aurora-A expression was positively correlated with expression level of androgen receptor (AR) or estrogen receptor (ER).

5.3.1. Prostate cancer

The current therapeutic strategy is mainly to inhibit androgen dependence of tumor growth by inactivating the AR with androgen-deprivation and/or anti-androgen therapies for prostate cancer (PC). However, most patients usually relapse with more aggression, due to the reaction of AR signaling and androgen receptor variants (AR-Vs), including AR gene amplification and mutation116. In clinical prostate cancer specimens, high-level of Aurora-A were determined116,117. Moreover, AURKA expression was up-regulated by AR, and bound to AR through an androgen receptor binding site (ARBS) on its promoter and intrinsic regions in the construction of overexpressing-AR PC cell lines116. The cells expressing the highest levels of AR were significantly sensitive to Aurora-A inhibitors, and cell growth was significantly inhibited at low concentrations of alisertib. Besides, down-regulated Aurora-A attenuated AR-Vs expression and chromatin enrichment118. Notably, the inhibition of Aurora-A reduced AR activity and proliferation of PC. However, Aurora-A could phosphorylate E3 ligase C-terminus of HSP70-interacting protein (CHIP) at the Ser273 site and enhance AR degradation via the proteasome119. Therefore, Aurora-A inhibitors might increase the proliferation of prostate cancer through the protection of AR from degradation, which indicated that Aurora-A inhibitors might have unintended adverse effects in PC118,119.

5.3.2. Breast cancer

The ER pathway is considered a critical carcinogenic pathway for ER-positive breast cancer. Adjuvant endocrine therapy has always been the main treatment for breast cancer, but about one-third of patients will eventually recurrence due to the resistance of endocrine therapy120. In estradiol-treated MCF7 cells, higher levels of Aurora-A were determined in an ER-dependent manner121,122. Aurora-A could phosphorylate nuclear transcription factor ERα transactivation activity at Ser167/Ser305, and interacted/colocalized with ERα, leading to tamoxifen resistance and disease relapse in ERα-positive breast cancer122. Meanwhile, the inhibition of Aurora-A sensitized tamoxifen-resistant cells and overcame the resistance of tamoxifen, further impeded estrogen-induced cell growth123. Similarly, the combination of fulvestrant and alisertib has robust inhibitory activity against tamoxifen-resistant MCF7 cells124.

6. Aurora-A and radioresistance

Radiotherapy (RT) is the primary anticancer treatment, usually combined with surgery and/or chemotherapy. The basic principle of RT is that ionizing radiation (IR) interacts with substances in tumor cells to destroy proteins and lipids, especially DNA, resulting in the termination of cell division and proliferation, and even leading to cell necrosis or apoptosis125. However, RT failure remains a major clinical challenge due to the development of resistance in the course of treatment. Aurora-A could affect the resistance to RT, since IR induces a DNA damage repair network by regulating Aurora-A in cancer cells71. Up-regulation of Aurora-A expression by transfection with AURKA cDNA, the percentage of apoptotic cells under IR condition was significantly reduced. Based on the Western blot and IHC analysis, Aurora-A was overexpressed in the tumor zone and facilitated the resistance of RT for nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients126.

Further studies revealed that knockdown Aurora-A restored the radiosensitivity of radiation-resistant HCC cells. Its mechanism was related to Aurora-A inducing NF-κB signaling and the activation of anti-apoptotic-related proteins127. Moreover, alisertib sensitizes lung cancer and NSCLC cell lines expressing p53 to IR in vitro. However, there is no significant enhancement in p53-deficient lung cancer, suggesting that the sensitivity of Aurora-A inhibitors to RT is related to p53 status128. In prostate cancer cells, Aurora-A inhibitor MLN8054 eliminated IR-regulated Aurora-A phosphorylation, induced G2/M arrest, and polyploidy. MLN8054 caused DNA damage and reduced DNA repair, resulting in radiosensitization129. In glioblastoma cells, CXCL12 mediates the resistance of glioblastoma to radiotherapy in the subventricular zone. After RT (5 Gy) drops, both Aurora-A and CXCL12 are in favor of radioresistant survival fractions. Treatment with MLN8054 was sufficient to sensitize CXCL12-stimulated glioblastoma cells to RT23.

In brief, radiotherapy could cause DNA damage through IR. However, IR can regulate Aurora-A phosphorylation, and initiate DNA damage and repair network, resulting in radioresistance in cancer cells. Thus, targeting inhibition of Aurora-A could significantly enhance the sensitivity of radioresistance.

7. Synthetic lethality strategy for targeting Aurora-A kinase

Synthetic lethality means that perturbation of two genes simultaneously leads to cell death, while the alteration of either gene alone is viable. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors are the first clinically approved anticancer drugs designed to utilize synthetic lethality. Patients carrying mutations of BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene are sensitive to PARP inhibitors130. Recent studies revealed that the synthetic lethal interaction of Aurora-A and other potential genes, these findings will expand the effectiveness in cancer treatment, and overcome drug resistance131.

7.1. RB1

Retinoblastoma gene RB1 mutations are common in refractory malignancies. Using drug-screening tests to identify drugs with selective sensitivity to RB1 mutant cancer cells, and found that Aurora-A inhibitors have synthetic lethality with RB1 loss132. Compared with RB1 wild-type, the inhibition of Aurora-A with Aurora-A inhibitors LY3295668 and ENMD-2076 has synthetically lethality of RB1-deficient lung cancer. Indeed, RB1-deficient cells exhibited unbalanced microtubule dynamics, and up-regulated the microtubule destabilizer stathmin133. Aurora-A inhibition facilitated stathmin activity by reducing phosphorylation, promoted microtubule instability and resulted in the destruction of microtubule dynamics, thereby triggering the synthetic lethality of RB1–Aurora-A132.

7.2. ARID1A

In CRC cells, the loss of AT-rich interactive domain 1A (ARID1A) is closely related to cancer progression and metastasis134. Similarly, the inhibition of Aurora-A does not impact on the growth of ARID1A wild-type CRC cells, but significantly inhibits the growth of ARID1A-deficient cancers135. Aurora-A inhibitor induced multi-nucleation, G2/M arrest and apoptosis in ARID1A-deficient cells. Moreover, ARID1A-deficient ovarian cancer cells are also significantly more sensitive to Aurora-A inhibitors than ARID1A wild-type cells, indicating that the synthetic lethality of ARID1A- Aurora-A existed in ovarian cancer.

7.3. MYC

The MYC oncogene has been identified as the crucial driver in cancers. In MYC-overexpressing non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), Aurora-A inhibition induced G2/M arrest and caspase-independent cell death99. Consistently, AURKA or TPX2 knockdown inhibited the proliferation of MYC-overexpressing cells more effectively22,99.

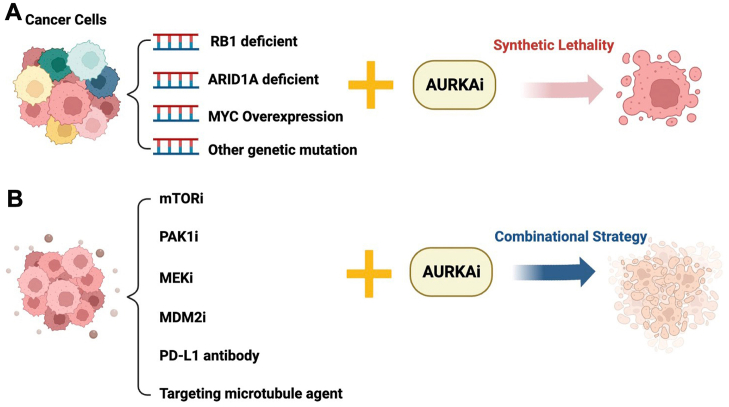

These investigations revealed that the inhibition of Aurora-A with RB1, ARID1A and MYC gene mutation phenotypes exists synthetic lethality, which could develop a novel strategy of Aurora-A-related cancer therapy (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Synthetic lethality and pharmacological combination strategy for targeting Aurora-A. (A) Synthetic lethality strategy for targeting Aurora-A. Aurora-A inhibitors have synthetic lethality in RB1, ARID1A and MYC gene mutation tumors, which also provides thoughts for the Aurora-A inhibitors towards individual therapy; (B) Combinational strategy for targeting Aurora-A. Aurora-A inhibitors have been demonstrated to have synergistic effects in combination with other therapeutics agents, including mTOR inhibitor, PAK1 inhibitor, MEK inhibitor, MDM2 inhibitor, PD-L1 antibody and microtubule inhibitor.

8. Pharmacological combination strategy for targeting Aurora-A kinase

In addition to synthetic lethality, the rational combination strategy of Aurora-A kinase inhibitor and other conventional cancer therapeutic agents result in a synergistic effect on the growth of cancer cells. For example, Aurora-A suppression induced the G2/M arrest, whereas the combination with Bcl-2 inhibitor navitoclax significantly reduced the G2/M phase and increased sub-G1 fraction, and drove cells into apoptosis136. Recently, some small molecular kinase inhibitors or immune checkpoint inhibitors can be sensitized in combination with Aurora-A inhibitors, and exhibit potent synergistic anticancer effect. Herein, we highlight the promising synergistic strategy for mTOR, PAK1, MDM2, MEK inhibitors or PD-L1 antibodies combined with targeting Aurora-A kinase (Fig. 3B).

8.1. mTOR inhibitors

The mTOR inhibitors alone caused G1 phase arrest. Researchers found that Aurora-A kinase could regulate mTOR activity through the ERK 1/2 pathway in TNBC59. Notably, synergistic effects were observed only when alisertib was administered before rapamycin treatment, reflecting the importance of scheduling sequences in therapeutic regimens. The combination of mTOR and Aurora-A inhibitors was observed to enhance the anticancer effects than any inhibitor alone59,137.

8.2. Microtube dynamics inhibitor

Eribulin, a microtubule dynamics inhibitor, induces the accumulation of active Aurora-A in TNBC, and provides a new thought for combined treatment. Aurora-A inhibition induced cytotoxic autophagy via activation of LC3B/P62 axis, resulting in the eradication of metastasis, but does not effect on the growth of breast cancers65. Interestingly, the combination of alisertib and eribulin causes the synergistic response of apoptosis and cytotoxic autophagy in breast cancers.

8.3. PAK1 inhibitor

The high-level expressions of oncoproteins also provided a strategy for drug combination. For instance, p21 activated kinase 1 (PAK1) and Aurora-A were commonly overexpressed in breast cancers, combined inhibition of FRAX1036 (a highly selective PAK1 inhibitor) and alisertib have remarkably synergistic antitumor effects138. Although drug resistance emerged to single-agent FRAX1036, combined alisertib with FRAX1036 caused an outstanding therapeutic response of drug-resistant subclones. In addition to PAK1, these combinations based on multiple mechanisms, as well as the combinations with the inhibition of ERα phosphorylation and C-MYC expression were also involved138,139.

8.4. MEK inhibitors

The combination of Aurora-A and MEK inhibitors has been found to have synergistic activity in CRC with KRAS and PIK3CA mutation140. The further evaluation indicated that the p53 mutant status affected apoptosis induced by combination with Aurora-A and MEK inhibitors in KRAS and PIK3CA mutant CRC141.

8.5. MDM2 inhibitors

Aurora-A combined with MDM2 antagonists could activate p53 and inhibit tumor growth. The combination therapy with alisertib and (–)-nutlin-3 further promoted the tumor immunological infiltration of host immune cells, such as NK cells, macrophages and antigen-presenting dendritic cells142.

8.6. PD-L1 antibody

PD-L1 expression was significantly enhanced in MDSCs after treatment with alisertib, and the anticancer activity of the effector T cells may be impaired by activating PD-1. In the 4T1 tumor-bearing mice model, the synergistic effect of the combination of alisertib and PD-L1 mAb on tumor suppression was found over a single treatment51. CD8+ T cells were dramatically enhanced in tumors under treatment with alisertib and PD-L1 mAb, while the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α in CD8+ T cells also elevated significantly.

9. Novel inhibitors targeting Aurora-A

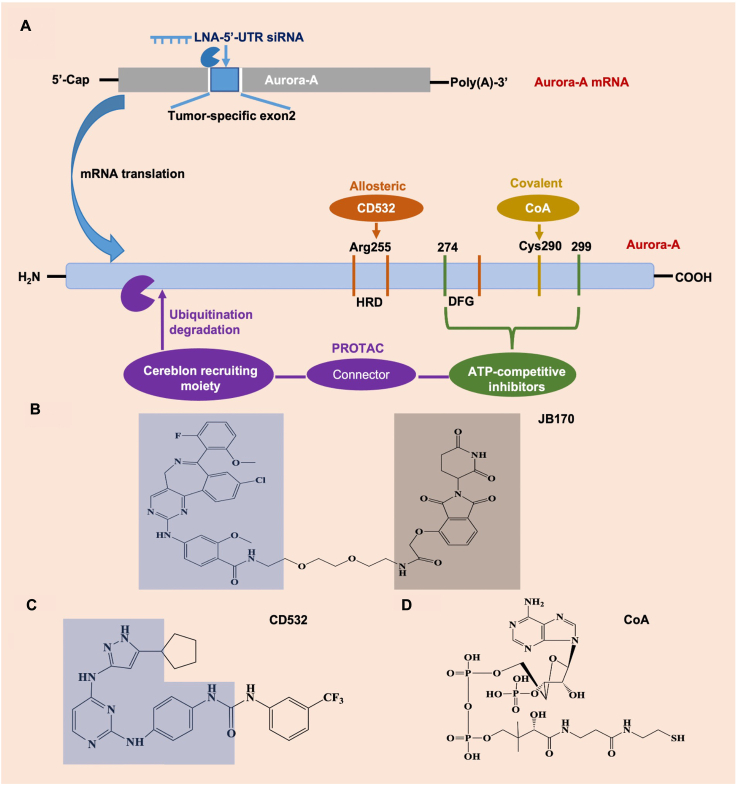

Given that Aurora-A participates in multiple of key cancer biological events, such as cell cycle regulation, cancer occurrence and advancement, and development of therapy resistance. Thus, Aurora-A inhibition exists a potent and selective anticancer activity. Currently, the targeted Aurora-A strategies could include ATP-competitive inhibitors and proteolytic targeting chimeras (PROTAC)-mediated degradation (Fig. 4). The selective small-molecule Aurora-A kinase inhibitors have potent anticancer efficacy in various cancer types. The majority of Aurora-A kinase inhibitors so far reported are competitive small molecule inhibitors that target the binding of ATP at the active site, such as alisertib. Alisertib is a highly selective Aurora-A kinase inhibitor developed by Millennium based on its predecessor MLN8054 (Table 1)143. Recently, a phase III trial was designed to assess the efficacy of alisertib in patients with relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL)144. Alisertib showed great efficacy in PTCL patients, but was not superior to the comparators. Including alisertib, several selective Aurora-A inhibitors have entered into clinical trials and achieved promising results (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Drug design strategies for targeting Aurora-A. (A) Schematic diagram of several targeted Aurora-A approaches. LNA, locked nucleic acid; UTR, untranslated region. (B) PROTACs contain three ethylene glycol molecules linked by amides of ATP-competitive inhibitor alisertib (blue region) and thalidomide (gray region). (C) The chemical structure of allosteric inhibitor CD532. The blue region represents chemical structures of allosteric conformational destruction (CD) compound diaminopyrimidine scaffold. (D) Covalent modification of Cys290 in Aurora-A by the thiol group of the pantetheine tail of CoA.

Table 1.

Selective Aurora-A inhibitor alisertib in clinical trailsa.

| Drug | Structure | Target | Type of cancer | Phase/Status | Design | Clinical trial numberb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alisertib (MLN8237) |  |

Aurora-A IC50 1.2 nmol/L |

Relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma | III/C | M | NCT01482962 |

| Aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; Acute myelogenous leukemia and high-grade myelodysplastic syndrome; Children with recurrent/refractory solid tumors and leukemias; Ovarian carcinoma; Recurrent or persistent leiomyosarcoma of the uterus; Metastatic castrate resistant and neuroendocrine prostate cancer; Advanced or metastatic sarcoma; Rhabdoid tumors |

II/C | M | NCT00807495; NCT00830518; NCT01154816; NCT00853307; NCT01637961; NCT01799278; NCT01653028; NCT02114229 | |||

| Unresectable Stage III–IV Melanoma | II/T (low accrual) | M | NCT01316692 | |||

| Malignant mesothelioma | II/NR | M | NCT02293005 | |||

| Unspecified childhood solid tumor, excluding CNS neuroblastoma | I/C | M | NCT02444884 | |||

| Myelofibrosis or relapsed or refractory acute megakaryoblastic leukemia | NR | M | NCT02530619 | |||

| Chemotherapy-pretreated urothelial cancer | II/C | M or CW: Paclitaxel | NCT02109328 | |||

| Relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma | II/C | M or CW: Rituximab | NCT01812005 | |||

| Locally advanced or metastatic, endocrine-resistant breast cancer | II/NR | M or CW: Fulvestrant | NCT02860000 | |||

| High-risk AML | II/C | CW: Induction chemotherapy | NCT02560025 | |||

| Small cell lung cancer | II/C | CW: Paclitaxel | NCT02038647 | |||

| Metastatic or locally recurrent breast cancer | II, NR | CW: Paclitaxel | NCT02187991 | |||

| Refractory multiple myeloma | I, II/C | CW: Bortezomib | NCT01034553 | |||

| Relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma | I, II/C | CW: Rituximab and vincristine | NCT01397825 | |||

| Non-small cell lung cancer | I, II/C | CW: Erlotinib | NCT01471964 | |||

| Neuroblastoma | I, II/C | CW: Irinotecan and temozolomide | NCT01601535 | |||

| Hormone-resistant prostate cancer | I, II/C | CW: Abiraterone and prednisone | NCT01848067 | |||

| Rb-deficient head and neck squamous cell cancer | I, II/R | CW: Pembrolizumab | NCT04555837 | |||

| Relapsed or recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma, B-Cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or peripheral T-cell lymphoma | I/C | CW: Vorinostat | NCT01567709 | |||

| Relapsed or refractory B-Cell or T-Cell lymphomas | I/C | CW: Romidepsin | NCT01897012 | |||

| Metastatic breast cancer | I/C | CW: MLN0128c | NCT02719691 | |||

| Metastatic EGFR-mutant lung cancer | I/C | CW: Osimertinib | NCT04085315 | |||

| Recurrent high grade gliomas | I/C | CW: Hyperfractionated radiation therapy | NCT02186509 | |||

| Head and neck cancer | I/C | CW: Cetuximab and definitive Radiation | NCT01540682 | |||

| Pancreatic cancer | I/C | CW: Gemcitabine | NCT01924260 | |||

| Gastrointestinal tumors | I/C | CW: mFOLFOX | NCT02319018 | |||

| Colorectal cancer | I/C | CW: Irinotecan | NCT01923337 | |||

| Solid tumors | I/C | CW: Pazopanib | NCT01639911 | |||

| Relapsed and refractory mantle cell and low grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma | I, NR | CW: Bortezomib and rituximab | NCT01695941 |

Abbreviations: C, completed, M, monotherapy; CW, combination with; NR, not recruiting; R, recruiting; T, terminated; mFOLFOX: a modified oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin regimen.

www.clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on March 2022).

MLN0128: a dual TORC1/2 inhibitor.

Table 2.

Several selective Aurora-A inhibitors in clinical trails.a

| Drug | Structure | Target | Type of cancer | Phase/status | Design | Clinical trial numberb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LY3295668 erbumine |  |

Aurora-A IC50 0.6 nmol/L |

Solid tumors | I, II/C | M | NCT03092934 |

| Small-cell lung cancer | I/C | M | NCT03898791 | |||

| Metastatic breast cancer | I/C | M or CW: Endocrine therapy or midazolam | NCT03955939 | |||

| Relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma | I/NR | M or CW: Topotecan or cyclophosphamide | NCT04106219 | |||

| EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer | I, II/R | CW: Osimertinib | NCT05017025 | |||

| ENMD-2076 |  |

Aurora-A IC50 14 nmol/L |

Triple negative breast cancer; ovarian clear cell carcinoma; advanced/metastatic soft tissue sarcoma; advanced fibrolamellar carcinoma | II/C | M | NCT01639248; NCT01914510; NCT01719744; NCT02234986 |

| Relapsed or refractory hematological malignancies; multiple myeloma; ovarian cancer | I/C | M | NCT00904787; NCT00806065; NCT01104675 | |||

| TAS-119 |  |

Aurora-A IC50 1.0 nmol/L |

Advanced solid tumors | I/T | M | NCT02448589 |

| Advanced solid tumors | I/T | CW: Paclitaxel | NCT02134067 | |||

| MLN8054 |  |

Aurora-A IC50 4 nmol/L |

Advanced malignancies | I/T (toxicity) | M | NCT00652158 |

Abbreviations: C, completed, M, monotherapy; CW, combination with; NR, not recruiting; R, recruiting; T, terminated.

www.clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on March 2022).

9.1. PROTAC-mediated degradation

Bifunctional small molecules, such as PROTACs, can target catalytic and non-catalytic functions145. The PROTACs were developed as effective Aurora-A degrading agents by linking alisertib to the E3-ubiquitin CEREBLON-binding thalidomide or thalidomide derivative-pomalidomide146,147. One kind of PROTACs comprises two or three (JB170) ethylene glycol molecules linked by amides of alisertib and thalidomide. These compounds caused a rapid decrease intra cellular level of Aurora-A kinase146. The degraders induced Aurora-A ubiquitination through CEREBLON, followed by undergoing proteolysis through the proteasome. PROTAC-mediated depletion does not require Aurora-A catalytic activity, as demonstrated that enzymatically inactive versions of mutated Aurora-A (Aurora-AD274N, Aurora-AK162R) were found to be depleted by JB170 to a similar degree as the un-mutated. PROTAC-mediated degradation is highly specific to Aurora-A, attributed to the combination of degrader between CEREBLON and Aurora-A supporting the formation of ternary complexes. Strikingly, the chemical knockdown mediated by the degrader caused a strong S phase arrest, and induced apoptosis in several types of cancer cells. At the subcellular level, PROTACs could eliminate Aurora-A on the mitotic spindle and leave the centrosome Aurora-A activity. PROTAC-mediated non-centrosome clearance regulated the cytoplasmic role of Aurora-A in mitochondrial dynamics147. Therefore, Aurora-A degraders are a powerful new tools that can be used to study the scaffold and catalytic functions of Aurora-A, and to develop a novel class of drugs to withstand the functions of Aurora-A in carcinogenesis.

9.2. LY3295668 erbumine

LY3295668 erbumine, developed by Eli Lilly, is a highly selective inhibitor of Aurora-A, with IC50 of 0.6 nmol/L, more than 1000-fold selectivity versus Aurora-B. LY3295668 was initially synthetically lethal in RB−/− cancer cells, especially for SCLC132. In breast and lung cancer cells, LY3295668 induced mitosis arrest and apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner148. LY3295668 inhibited tumor growth in SCLC xenograft models, and 50 mg/kg of LY3295668 in twice-daily for 28-day cycles treatment showed 97.2% of tumor growth inhibition. A phase I clinical trial explored the safety and anticancer activity in patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. The maximum tolerated dose of LY3295668 is 25 mg twice daily. Currently, LY3295668 has been proved to have anticancer activity in some patients149.

9.3. TAS-119

TAS-119, developed by Taiho Pharmaceuticals, is an orally Aurora-A inhibitor with an IC50 of 1.04 nmol/L and high selectivity versus Aurora-B (IC50 = 95 nmol/L)150. TAS-119 induced the accumulation of mitotic cells via Aurora-A inhibition in vitro and in vivo. Besides, TAS-119 showed strong anticancer activity, especially in various cancers carrying MYC amplification and CTNNB1 (encoding β-catenin) mutations151. Moreover, TAS-119 increased the anti-proliferative and in vitro and in vivo antitumor effects of paclitaxel in various cancer model, which suggested the further study of TAS-119 to find potential synergistic effects152. In a phase I study with an intermittent schedule of 200 mg TAS-119 twice daily, targeted regulation was demonstrated, but the antitumor effects were not as expected153. Although the observed ocular toxicity, the overall safety of TAS-119 appears to be outstanding compared to other Aurora-A inhibitors153.

10. Conclusion and perspective

Aurora-A not only impacts on the occurrence and progression of tumors, but also participates the development of cancer therapy resistance. The oncogenetic mechanism of Aurora-A involves proliferation, survival, metastasis, stemness, and the latest discovered emerging cancer hallmarks, including energy metabolic reprogramming and immune escape, which are the basis for targeting therapy. Aurora-A regulates energy metabolism by increasing glycolytic flux and ATP biosynthesis. At the same time, Aurora-A is involved in evading immune destruction, which is associated with increased MDSCs, TAMs populations and T cell apoptosis. More detailed understanding of Aurora-A in tumorigenesis is helpful for targeted therapy and effectively targeting cancer treatment in individual patients. Furthermore, Aurora-A plays crucial roles in therapy resistance, causing chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The mechanism of drug-resistant development involves DNA damage repair, metastasis, stemness and autophagy. Meanwhile, the inhibition of Aurora-A could increase the sensitivity of drug treatment and radiation therapy. In addition, emerging evidence shows that Aurora-A is associated with poor OS, and could bind and activate oncogenes promoters (such as MYC) through nuclear transactivation activity to induce stemness and further generate therapeutic resistance.

There is no doubt that the inhibition of Aurora-A improves cancer therapy and reverse drug resistance. So far, the primary targeted therapy of Aurora-A is ATP-competitive inhibitors. Single-agent targeted therapy in clinical trials has shown clinical benefits, like alisertib. However, the phase III clinical trial of alisertib in the treatment of relapsed/refractory PTCL has been terminated since the primary endpoints did not achieve. Selective Aurora-A inhibitors such as alisertib are still the most promising representative drugs. The tolerability and safety of alisertib are acceptable for patients, but its limitations are the complexity of using doses among various tumor types or ethnicities, and it has not been proved to be more efficacy than comparators. Recently, alisertib has launched numerous trials for drug combination, which are expected to be approved for cancer therapy. LY3295668 Erbumine is also a promising drug. Unlike alisertib, LY3295668 Erbumine is mainly used for the treatment of solid tumors. The clinical application of TAS-119 might be limited by its ocular toxicity. Moreover, phase I or II clinical trials of some ATP-competitive pan-Aurora inhibitors have announced withdrawal or termination due to high toxicity or other unreported reasons. Thus, more targeted Aurora-A strategies are being developed in addition to ATP-competitive inhibitors. Through allosteric or covalent modification, PROTAC-mediated degradation and targeting mRNA of Aurora-A, lower toxicity and more potent efficacy were significantly observed (Fig. 4)146,154,155. The most representative is the allosteric inhibitor CD532 (IC50 = 45 nmol/L), which can disrupt the conformation of this kinase, disrupt the non-catalytic function, and significantly induce cell cycle arrest156. Of note, Aurora-A degraders are a promising tool that can be used to study the scaffold and catalytic functions of Aurora-A, and to develop a novel class of drugs targeting Aurora-A. Besides, numerous experimental studies on immunotherapy are applied in Aurora-A as a target and have achieved better responses. For example, using Aurora-A as a tumor antigen for cellular immunotherapy, as well as the reduction of tumor immunosuppression by Aurora-A inhibitors, are potential therapeutic strategies157,158. Furthermore, to assess the benefit and accuracy of targeted therapy, the application of specific biomarkers is critical. For instance, MYC has been suggested to predict the sensitivity of targeted Aurora-A therapy159.

In addition, since some ATP-competitive inhibitors have not achieved expected effects, combination therapy is a promising treatment strategy. Aurora-A was found to have synthetic lethality in some gene-mutated tumors. To date, Aurora-A inhibitors have synthetic lethality in RB1, ARID1A and MYC gene mutation tumors, which also provides thoughts for the Aurora-A inhibitors towards individual therapy. Additionally, Aurora-A inhibitors have been demonstrated to have synergistic effects with conventional chemotherapy, small molecular kinase inhibitors or mAbs, such as mTOR inhibitor (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02719691). These combinations could reduce the dosage of the Aurora-A inhibitors, enable low toxicity and enhanced anticancer efficacy. Hence, targeted Aurora-A therapy may be beneficial to patients through preventing cancer progression and overcoming the therapy resistance.

Acknowledgments

We want to apologize for those authors whose study we could not cite due to space constrains. The project was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (No. H2020209284, China, Dayong Zheng); Scientific Research Foundation of Higher Education Institutions of Hebei Province (No. QN2021120, Dayong Zheng); Department of Science and Technology of Liaoning province (No. 2020-MS-225, China, Jun Li); the Montefiore Einstein Cancer Center grant (NCI P30CA013330, USA, Edward Chu).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

Contributor Information

Edward Chu, Email: edward.chu@einsteinmed.edu.

Ning Wei, Email: ning.wei@einsteinmed.edu.

Author contributions

Ning Wei and Dayong Zheng conceived and designed this review. Dayong Zheng and Jun Li analyzed the literatures and summarized the results. Ning Wei and Dayong Zheng designed and regenerated the figures. Ning Wei and Edward Chu reviewed and edited this review. Han Yan, Gang Zhang and Wei Li checked the figures and formatted the tables. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Barr A.R., Gergely F. Aurora-A: the maker and breaker of spindle poles. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2987–2996. doi: 10.1242/jcs.013136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan M., Wang C., He B., Yang M., Tong M., Long Z., et al. Aurora-A kinase: a potent oncogene and target for cancer therapy. Med Res Rev. 2016;36:1036–1079. doi: 10.1002/med.21399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin X., Xiang X., Hao L., Wang T., Lai Y., Abudoureyimu M., et al. The role of aurora-A in human cancers and future therapeutics. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:2705–2729. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perona R., Sánchez-Pérez I. Control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:573–577. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Housman G., Byler S., Heerboth S., Lapinska K., Longacre M., Snyder N., et al. Drug resistance in cancer: an overview. Cancers. 2014;6:1769–1792. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos P., Bentires-Alj M. Mechanism-based cancer therapy: resistance to therapy, therapy for resistance. Oncogene. 2015;34:3617–3626. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan C.S., Botstein D. Isolation and characterization of chromosome-gain and increase-in-ploidy mutants in yeast. Genetics. 1993;135:677–691. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.3.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmena M., Earnshaw W.C. The cellular geography of aurora kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:842–854. doi: 10.1038/nrm1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marumoto T., Zhang D., Saya H. Aurora-A—a guardian of poles. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:42–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veerakumarasivam A., Goldstein L.D., Saeb-Parsy K., Scott H.E., Warren A., Thorne N.P., et al. AURKA overexpression accompanies dysregulation of DNA-damage response genes in invasive urothelial cell carcinoma. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3525–3533. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.22.7042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor S., Peters J.M. Polo and aurora kinases: lessons derived from chemical biology. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lens S.M., Voest E.E., Medema R.H. Shared and separate functions of polo-like kinases and aurora kinases in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:825–841. doi: 10.1038/nrc2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikonova A.S., Astsaturov I., Serebriiskii I.G., Dunbrack R.L., Jr., Golemis E.A. Aurora A kinase (AURKA) in normal and pathological cell division. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:661–687. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Littlepage L.E., Ruderman J.V. Identification of a new APC/C recognition domain, the A box, which is required for the Cdh1-dependent destruction of the kinase aurora-A during mitotic exit. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2274–2285. doi: 10.1101/gad.1007302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Littlepage L.E., Wu H., Andresson T., Deanehan J.K., Amundadottir L.T., Ruderman J.V. Identification of phosphorylated residues that affect the activity of the mitotic kinase aurora-A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15440–15445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202606599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eyers P.A., Erikson E., Chen L.G., Maller J.L. A novel mechanism for activation of the protein kinase aurora A. Curr Biol. 2003;13:691–697. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong Y., Yang J., Xu W.W., Wang Y., Zheng C.C., Li B., et al. KCTD12 promotes tumorigenesis by facilitating CDC25B/CDK1/aurora A-dependent G2/M transition. Oncogene. 2017;36:6177–6189. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tavernier N., Thomas Y., Vigneron S., Maisonneuve P., Orlicky S., Mader P., et al. Bora phosphorylation substitutes in trans for T-loop phosphorylation in aurora A to promote mitotic entry. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1899. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21922-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi K., Zhang J.Z., Yang L., Li N.N., Yue Y., Du X.H., et al. Protein deubiquitylase USP3 stabilizes aurora A to promote proliferation and metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1196. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08934-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayliss R., Sardon T., Vernos I., Conti E. Structural basis of aurora-A activation by TPX2 at the mitotic spindle. Mol Cell. 2003;12:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zorba A., Buosi V., Kutter S., Kern N., Pontiggia F., Cho Y.J., et al. Molecular mechanism of aurora A kinase autophosphorylation and its allosteric activation by TPX2. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.02667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi Y., Sheridan P., Niida A., Sawada G., Uchi R., Mizuno H., et al. The AURKA/TPX2 axis drives colon tumorigenesis cooperatively with MYC. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:935–942. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willems E., Dedobbeleer M., Digregorio M., Lombard A., Goffart N., Lumapat P.N., et al. Aurora A plays a dual role in migration and survival of human glioblastoma cells according to the CXCL12 concentration. Oncogene. 2019;38:73–87. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0437-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsueh K.W., Fu S.L., Chang C.B., Chang Y.L., Lin C.H. A novel aurora-A-mediated phosphorylation of p53 inhibits its interaction with MDM2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang S.S., Yamaguchi H., Xia W., Lim S.O., Khotskaya Y., Wu Y., et al. Aurora A kinase activates YAP signaling in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:1265–1275. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dutertre S., Cazales M., Quaranta M., Froment C., Trabut V., Dozier C., et al. Phosphorylation of CDC25B by aurora-A at the centrosome contributes to the G2-M transition. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2523–2531. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toji S., Yabuta N., Hosomi T., Nishihara S., Kobayashi T., Suzuki S., et al. The centrosomal protein Lats2 is a phosphorylation target of aurora-A kinase. Gene Cell. 2004;9:383–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cazales M., Schmitt E., Montembault E., Dozier C., Prigent C., Ducommun B. CDC25B phosphorylation by aurora-A occurs at the G2/M transition and is inhibited by DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1233–1238. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rong R., Jiang L.Y., Sheikh M.S., Huang Y. Mitotic kinase aurora-A phosphorylates RASSF1A and modulates RASSF1A-mediated microtubule interaction and M-phase cell cycle regulation. Oncogene. 2007;26:7700–7708. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang C.Y., Coppinger J.A., Seki A., Yates J.R., 3rd, Fang G. Plk1 and aurora A regulate the depolymerase activity and the cellular localization of Kif2a. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1334–1341. doi: 10.1242/jcs.044321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song S.J., Song M.S., Kim S.J., Kim S.Y., Kwon S.H., Kim J.G., et al. Aurora A regulates prometaphase progression by inhibiting the ability of RASSF1A to suppress APC-Cdc20 activity. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2314–2323. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emery A., Sorrell D.A., Lawrence S., Easthope E., Stockdale M., Jones D.O., et al. A novel cell-based, high-content assay for phosphorylation of Lats2 by aurora A. J Biomol Screen. 2011;16:925–931. doi: 10.1177/1087057111413923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajeev R., Singh P., Asmita A., Anand U., Manna T.K. Aurora A site specific TACC3 phosphorylation regulates astral microtubule assembly by stabilizing γ-tubulin ring complex. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:58. doi: 10.1186/s12860-019-0242-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Q., Li J., Yang X., Ma J., Gong F., Liu Y. Prdx1 promotes the loss of primary cilia in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:372. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06898-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Byrne D.P., Shrestha S., Galler M., Cao M., Daly L.A., Campbell A.E., et al. Aurora A regulation by reversible cysteine oxidation reveals evolutionarily conserved redox control of Ser/Thr protein kinase activity. Sci Signal. 2020;13 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aax2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim D.C., Joukov V., Rettenmaier T.J., Kumagai A., Dunphy W.G., Wells J.A., et al. Redox priming promotes aurora A activation during mitosis. Sci Signal. 2020;13 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.abb6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuchiya Y., Byrne D.P., Burgess S.G., Bormann J., Baković J., Huang Y., et al. Covalent aurora A regulation by the metabolic integrator coenzyme A. Redox Biol. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang A., Gao K., Chu L., Zhang R., Yang J., Zheng J. Aurora kinases: novel therapy targets in cancers. Oncotarget. 2017;8:23937–23954. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broccoli D., Godwin A.K. Telomere length changes in human cancer. Methods Mol Med. 2002;68:271–278. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-135-3:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang H., Ou C.C., Feldman R.I., Nicosia S.V., Kruk P.A., Cheng J.Q. Aurora-A kinase regulates telomerase activity through c-Myc in human ovarian and breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:463–467. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun H., Wang H., Wang X., Aoki Y., Wang X., Yang Y., et al. Aurora-A/SOX8/FOXK1 signaling axis promotes chemoresistance via suppression of cell senescence and induction of glucose metabolism in ovarian cancer organoids and cells. Theranostics. 2020;10:6928–6945. doi: 10.7150/thno.43811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng A., Zhang P., Wang B., Yang D., Duan X., Jiang Y., et al. Aurora-A mediated phosphorylation of LDHB promotes glycolysis and tumor progression by relieving the substrate-inhibition effect. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5566. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13485-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giacomello M., Pyakurel A., Glytsou C., Scorrano L. The cell biology of mitochondrial membrane dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:204–224. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertolin G., Bulteau A.L., Alves-Guerra M.C., Burel A., Lavault M.T., Gavard O., et al. Aurora kinase A localises to mitochondria to control organelle dynamics and energy production. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.38111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Signes A., Fernandez-Vizarra E. Assembly of mammalian oxidative phosphorylation complexes I–V and supercomplexes. Essays Biochem. 2018;62:255–270. doi: 10.1042/EBC20170098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gabrilovich D.I., Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin T., Zhao Z.B., Guo J., Wang T., Yang J.B., Wang C., et al. Aurora A inhibition eliminates myeloid cell-mediated immunosuppression and enhances the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 therapy in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79:3431–3444. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han J., Jiang Z., Wang C., Chen X., Li R., Sun N., et al. Inhibition of aurora-A promotes CD8+ T-cell infiltration by mediating IL10 production in cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2020;18:1589–1602. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yasar B., Linton K., Slater C., Byers R. Primary cilia are increased in number and demonstrate structural abnormalities in human cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:571–574. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2016-204103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Korobeynikov V., Deneka A.Y., Golemis E.A. Mechanisms for nonmitotic activation of aurora-A at cilia. Biochem Soc Trans. 2017;45:37–49. doi: 10.1042/BST20160142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin F., Chen Q., Shi Y., Xu H., Huang J., Qing M., et al. Activation of EGFR-aurora A induces loss of primary cilia in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2022;28:621–630. doi: 10.1111/odi.13791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeong A.L., Ka H.I., Han S., Lee S., Lee E.W., Soh S.J., et al. Oncoprotein CIP2A promotes the disassembly of primary cilia and inhibits glycolytic metabolism. EMBO Rep. 2018;19 doi: 10.15252/embr.201745144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pejskova P., Reilly M.L., Bino L., Bernatik O., Dolanska L., Ganji R.S., et al. KIF14 controls ciliogenesis via regulation of aurora A and is important for Hedgehog signaling. J Cell Biol. 2020;219 doi: 10.1083/jcb.201904107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fulda S. Tumor resistance to apoptosis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:511–515. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang W., Xia D., Li Z., Zhou T., Chen T., Wu Z., et al. Aurora-A/ERK1/2/mTOR axis promotes tumor progression in triple-negative breast cancer and dual-targeting aurora-A/mTOR shows synthetic lethality. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:606. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1855-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park J.W., Chae Y.C., Kim J.Y., Oh H., Seo S.B. Methylation of aurora kinase A by MMSET reduces p53 stability and regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2018;37:6212–6224. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0393-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hou D., Che Z., Chen P., Zhang W., Chu Y., Yang D., et al. Suppression of AURKA alleviates p27 inhibition on Bax cleavage and induces more intensive apoptosis in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:781. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0823-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie Y., Zhu S., Zhong M., Yang M., Sun X., Liu J., et al. Inhibition of aurora kinase A induces necroptosis in pancreatic carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1429–1443. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mele L., Del Vecchio V., Liccardo D., Prisco C., Schwerdtfeger M., Robinson N., et al. The role of autophagy in resistance to targeted therapies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;88 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zou Z., Yuan Z., Zhang Q., Long Z., Chen J., Tang Z., et al. Aurora kinase A inhibition-induced autophagy triggers drug resistance in breast cancer cells. Autophagy. 2012;8:1798–1810. doi: 10.4161/auto.22110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kozyreva V.K., Kiseleva A.A., Ice R.J., Jones B.C., Loskutov Y.V., Matalkah F., et al. Combination of eribulin and aurora A inhibitor MLN8237 prevents metastatic colonization and induces cytotoxic autophagy in breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1809–1822. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]