Abstract

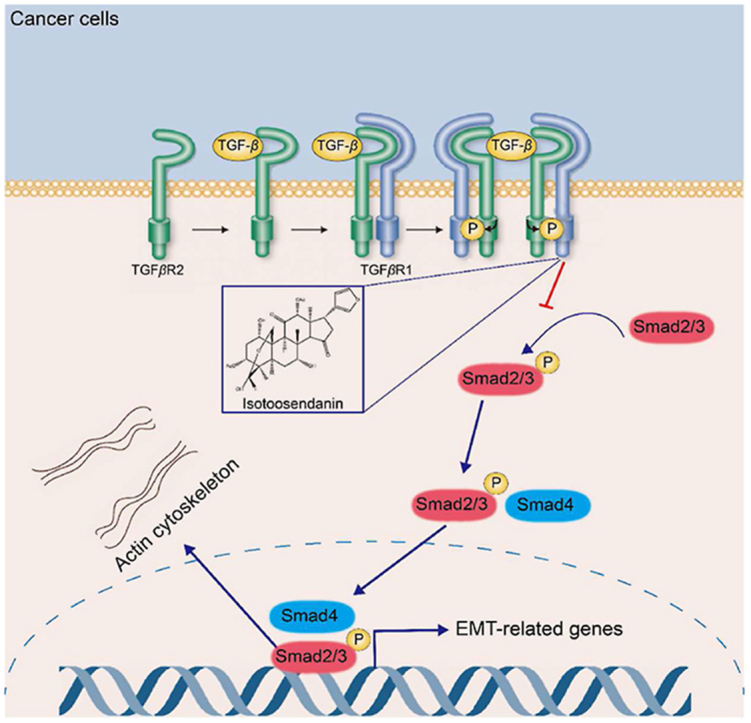

As the most aggressive breast cancer, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is still incurable and very prone to metastasis. The transform growth factor β (TGF-β)-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is crucially involved in the growth and metastasis of TNBC. This study reported that a natural compound isotoosendanin (ITSN) reduced TNBC metastasis by inhibiting TGF-β-induced EMT and the formation of invadopodia. ITSN can directly interact with TGF-β receptor type-1 (TGFβR1) and abrogated the kinase activity of TGFβR1, thereby blocking the TGF-β-initiated downstream signaling pathway. Moreover, the ITSN-provided inhibition on metastasis obviously disappeared in TGFβR1-overexpressed TNBC cells in vitro as well as in mice bearing TNBC cells overexpressed TGFβR1. Furthermore, Lys232 and Asp351 residues in the kinase domain of TGFβR1 were found to be crucial for the interaction of ITSN with TGFβR1. Additionally, ITSN also improved the inhibitory efficacy of programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody for TNBC in vivo via inhibiting the TGF-β-mediated EMT in the tumor microenvironment. Our findings not only highlight the key role of TGFβR1 in TNBC metastasis, but also provide a leading compound targeting TGFβR1 for the treatment of TNBC metastasis. Moreover, this study also points out a potential strategy for TNBC treatment by using the combined application of anti-PD-L1 with a TGFβR1 inhibitor.

Key words: TNBC, Isotoosendanin, Metastasis, TGFβR1, Epithelial–mesenchymal transition, Invadopodia, PD-L1, Tumor microenvironment

Graphical abstract

A natural compound isotoosendanin improved the tumor microenvironment via inhibiting EMT through directly interacting with the kinase domain of TGFβR1, which not only blocked TNBC metastasis but also enhanced the efficacy of anti-PD-L1.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent gynecologic tumor accounting for 25% of all female tumors, and its incidence is still on the rise1. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a subtype of breast cancer categorized with the negative expression of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, accounting for approximately 15% of breast cancers1,2. TNBC is characterized by a huge tendency to relapse and a high rate of metastasis, mostly accompanied with liver, lung, bone and brain metastasis3,4. The prognosis of patients with metastatic TNBC is very poor, and the median overall survival is only 13.3 months even after treatment5.

TNBC patients generally fail to benefit from endocrine therapy and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-targeted therapy, so chemotherapy or surgery remains the only first-line treatment1,6. Several conventional drugs such as paclitaxel, cisplatin and mutant serine/threonine-protein kinase B-RAF inhibitors have been approved for TNBC treatment by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These drugs exhibited good efficacy in inhibiting tumor growth, yet not in preventing TNBC metastasis. Even worse, some of these drugs were reported to promote metastasis in preclinical in vivo models instead of exerting suppression7. Therefore, there is an urgent need for seeking effective drugs for TNBC treatment.

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is highly expressed in the tumor microenvironment8,9. TGF-β effectively drives the epithelial cells from polygonal to spindle-shaped via promoting the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) process in tumors, including enhancing the expression of mesenchymal markers like actin alpha 2 (α-SMA), fibroblast specific protein-1 (FSP1) and Vimentin, and decreasing the expression of epithelial markers like E-cadherin, Claudin-1 and ZO-1, thereby leading to tumor metastasis10, 11, 12. In response to TGF-β stimulation, the receptor type II (TGFβR2) bound to receptor type I (TGFβR1) and induced its phosphorylation, which facilitated the phosphorylation of downstream transcription factors like Smad family member2/3 (Smad2/3), and then regulated the transcriptional expression of downstream EMT-related genes9,11. Currently, some drugs targeting TGF-β had been demonstrated to be effective in inhibiting tumor metastasis, but they were not yet widely used for cancer treatment in clinic because that their cardiac and intestinal toxicities were non-negligible13, 14, 15, 16. Therefore, further efforts are needed in the development and clinical translation of TGF-β inhibitors.

Tumors can evade immune surveillance through inducing the activation of immune checkpoints17. Among all these immune checkpoints, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) by far acquire the most attention. Numerous clinical studies have shown that anti-PD1/PD-L1 have potent and durable anti-cancer activity in renal cell carcinoma, lung cancer, melanoma and hepatocellular carcinoma18, 19, 20, 21. However, its efficacy in treating TNBC is still limited22. Researches have shown that TNBC resists anti-PD-L1 therapy mainly because that the infiltration of T lymphocytes into tumor tissues is very difficult23,24. It's well documented that the activation of TGF-β-initiated signaling pathway resulted in immunosuppression, because that the excessive collagen production induced by TGF-β prevented the infiltration of immune cells into the tumor microenvironment25. In addition, TGF-β decreased the immune response in tumor microenvironment by weakening the function of cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells, inhibiting the antigen presentation of dendritic cells (DCs) and inducing the differentiation of regulatory T cells25, 26, 27, 28, 29. Thus it can be seen that inhibiting TGF-β signaling pathway might have a potential to enhance the therapeutic efficacy provided by anti-PD-L1.

Isotoosendanin (ITSN) is a natural triterpenoid contained in Fructus Meliae Toosendan. Our previous report showed that ITSN effectively reduced the growth of TNBC30. In this study, a lower dose of ITSN was found to inhibit TNBC metastasis and enhance the inhibitory effect of anti-PD-L1 on TNBC growth by abrogating the TGF-β-induced EMT through directly targeting TGFβR1.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Antibodies and chemical reagents

Antibodies against E-cadherin, Vimentin, TGFβR2, FSP1, α-SMA, Smad2/3, phosphorylated Smad2/3, Snail family zinc finger 1 (Snail) and Flag were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibody against β-actin was purchased from Hua Biologics (Hangzhou, China). Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) antibody was purchased from ABclonal (Wuhan, China). TGF-β1 ELISA kits, TGFβR1 antibody and TGFβR1 recombinant protein were bought from R&D (Minneapolis, MN, USA). CD45, CD3, CD8, CD11C, MHC-II and CD206 antibodies were bought from BD Pharmingen (Franklin Lake, NJ, USA). CD107a, F4/80 and Granzyme B antibodies, BCA protein assay kits, Immunoprecipitation kit and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Anti-PD-L1 was purchased from Bioxcell (West Lebanon, NH, USA). Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (H + L) and anti-mouse IgG (H + L) were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA). Alexa Fluor 647 phalloidin or Alexa 488-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody, Alexa 488-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody or Alexa 568-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody were purchased from Life Technology (Carlsbad, CA, USA). TGF-β was obtained from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). Hoechst 33258 was purchased from Yeasen (Shanghai, China). Sepharose 6B beads and chip CM7 were purchased from Cytiva (Uppsala, Sweden). XenoLight d-Luciferin potassium salt was purchased from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA, USA). Collagenase B was purchased from Roche (Nutley, NJ, USA). Hyaluronidase was purchased from Absin (Shanghai, China). The catalogue number for the used antibodies is shown in Supporting Information Table S1.

2.2. Cell culture

MDA-MB-231, BT549 and 4T1 cells were purchased from ATCC (Rockefeller, MA, USA). BT549-luc-GFP, MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP, MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP-TGFβR1, MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP-shTGFβR1 and 4T1-luc-GFP cell lines were constructed by Zhong-Qiao-Xin-Zhou Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). 4T1, 4T1-luc-GFP, BT549 and BT549-luc-GFP cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium. MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP-TGFβR1, MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP-shTGFβR1 and MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose medium. Cell culture medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

2.3. Natural compound

ITSN (purity ≥98.0%) was purchased from Yuan-Ye Bio-Tech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The chemical structure of ITSN is shown in Supporting Information Fig. S1.

2.4. Animals

All animals received humane care in accordance with the institutional animal care guidelines approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and all experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Totally 73 nude (BALB/c, 4-week-old) female mice and 70 normal (BALB/c, 4-week-old) female mice were purchased from the Shanghai Experimental Animal Centre, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free condition according to the requirements of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines.

2.5. Animal treatment

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and TNBC cells (1 × 106 per mouse) were injected subcutaneously into the fourth right mammary fat pad at the base of the nipple of mice. When tumors were visible (Day 10), these mice were randomly grouped. MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mice, MDA-MB-231-TGFβR1 tumor-bearing mice, MDA-MB-231-shTGFβR1 tumor-bearing mice and BT549 tumor-bearing mice were given ITSN (0.1, 1 mg/kg/day, i.g.) continuously for 2 months on Day 10 after the injection of TNBC cells. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were given ITSN (0.1, 1 mg/kg/day, i.g.) continuously for 1 month on Day 10 after the injection of 4T1 cells. The blank and TNBC model groups were treated with an equal volume of vehicle (0.5% CMC-Na in water). Tumor growth was monitored every 3 days, and tumor volume was calculated according to Eq. (1):

| Volume = 0.5 × Length × Width2 | (1) |

For the ITSN and anti-PD-L1 combination therapy, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and 4T1 cells (1 × 106 per mouse) were injected subcutaneously into the fourth right mammary fat pad at the base of the nipple of mice. When tumors were visible (Day 10), these mice were randomly grouped with 13 mice in each group, among which 8 mice were used for evaluating the survival rate. Mice were given ITSN (1 mg/kg/day, i.g.) by gavage daily until the end of the experiment. At the same time, mice were given the intraperitoneal injection of α-PD-L1 (6.6 mg/kg/week, i.p.) every 2 weeks until the end of the experiment. The blank and TNBC model groups were treated with an equal volume of vehicle. Tumor growth was monitored every 3 days, and tumor volume was calculated as Eq. (1).

In the last week before the end of the experiment, tumor metastasis in mice was detected. After inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane, mice were imaged by using the IVIS Lumina system and Living Image software 4.0 (PerkinElmer) after an intraperitoneal injection of 2.5 mg of fluorescein (PerkinElmer). The total signal for each defined area of interest was calculated as photons/s/cm2 (total flux/area).

Mice were anesthetized by the inhalation of isoflurane, and blood samples were taken from the abdominal aorta. Primary tumors and organs were harvested, paraffin-embedded, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

2.6. Wound healing assay

TNBC cells were seeded in 24-well plates. When cells reached the required confluence, the plates were scraped by using a pipette tip. Then, cells were further incubated with the indicated concentration of ITSN. Wound healing was imaged at 0 and 24 h after the addition of ITSN by using a microscope (IX81, Olympus, Japan). The migration percentage was analyzed by using Image J 1.8.0.

2.7. Cell migration and invasion assay

Migration and invasion of TNBC cells were detected by using a Transwell chamber (Corning, NY) with a polycarbonate membrane of 8-μm pore. For the migration assay, 200 μL cells (2 × 104 cells) were seeded into the chamber that was placed in a 24-well plate, and cell culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum was added into the 24-well plate down the chamber. After the incubation with ITSN for 24 h, cells in the chamber were scraped, and cells migrated to the dorsal surface of the chamber were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. For the invasion assay, polycarbonate membranes in the chamber were pre-coated with matrigel, and the other experimental procedures were the same as described in the migration assay. For quantification, cells in six randomly selected fields were counted under a microscope (IX81, Olympus, Japan). All experiments were performed three times independently.

2.8. Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Cells and tumor tissues were homogenized in the ice-cold lysis buffer. Protein concentration in each sample from the same experiment was standardized to the same protein concentration. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and then incubated with a combination of primary and secondary antibodies. Proteins were visualized by using a chemiluminescence kit. The grey densities of protein bands were normalized by using β-actin density as an internal control and the results were further normalized to the control (The statistical results for WB bands are shown in Supporting Information Fig. S2).

2.9. Immunofluorescence staining assay

To stain Smad2/3, TGFβR1 and F-actin, TNBC cells were incubated with or without TGF-β or ITSN for 24 h. After treatment, cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 30 min, and then incubated with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 min and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h. Cells were further incubated overnight (4 °C) with the appropriate primary antibody or phalloidin, and then incubated with Alexa 488-labelled goat anti-rabbit antibody or Alexa 488-labelled goat anti-mouse antibody or Alexa 568-labelled goat anti-rabbit antibody for 1 h at room temperature and protected from light. Hoechst 33258 was used to stain the nuclei. The cells were imaged under confocal microscopy (TCS SP8, Leica, Germany).

2.10. Immunoprecipitation assay

Cells were lysed on ice for 2 h in 1 × RIPA lysis solution containing protease inhibitors. The supernatants were collected after centrifugation and further incubated with Dynabeads and Smad2/3 antibody or TGFβR1 antibody at room temperature with gentle shaking. After precipitation, Dynabeads were washed 3 times with cold wash buffer, boiled for 10 min at 99 °C in 2 × loading buffer and then further analyzed by Western blotting.

2.11. H&E staining

Lung or liver tissues were fixed in 4% PFA. Samples were then sectioned (5 μm), stained with H&E reagent, and then observed under a light microscope (Olympus X81) to quantify the metastatic foci.

2.12. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The supernatant from cultured TNBC cells was collected for ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 100 μL of standard, control or sample was added to each well. The system is incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Each well is then aspirated and washed with wash buffer (400 μL) and the process is repeated four times. Next, 100 μL of coupling compound is added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The aspiration and washing process was repeated five times. Then, 100 μL of substrate solution was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Then 100 μL of stop solution was added to each well. Finally, the optical density of each well was measured at 450 nm.

2.13. RNA sequencing and analysis

Total RNA was extracted by using a Trizol reagent and RNA quality was assessed by using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument (Paloalto, CA, USA). Libraries were quantified by using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and an ABI StepOnePlus RT-PCR system (Thermo Fisher, MA, USA). The Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform was used to sequence the transcriptomes of 4T1 model tumor samples from mice and their control samples (n = 3). The sequencing data underwent a pre-processing filtering step (removing splice sequences and short fragments) after sequencing quality control, and the resulting trimmed data is compared to the reference genome, and then the genes and transcripts are quantitatively analyzed. Differentially expressed transcripts were identified according to the following criteria: |fold change| > 1 and P-value <0.05. A total of 404 genes were differentially expressed, of which 53 were up-regulated and 351 were down-regulated (Supporting Information Table S2) (GSE217003).

2.14. Proteomic analysis

An equal number of three samples from 4T1 mice model tumor samples were digested with trypsin according to the filter-assisted sample preparation method. The solution was collected by centrifugation at 11,000 × g and 4 °C, and then the reaction was stopped by adding 0.4% trifluoroacetic acid. The final sample was dried by using a high-speed vacuum concentrator and dissolved in 30 μL of 0.1% formic acid for liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis. Peptides were detected by nano-LC/orbitrap Fusion Lumos HR-MS and columns were separated on a 2 μm Acclaim Pepmap RSLC C18 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The mass spectrometer was operated in a “top speed” algorithm in a data-dependent acquisition mode under positive ionization. The Orbitrap Fusion Lumos High Resolution Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) detects peptides and analyses samples by scanning the mass range of 350–1300 m/z at 70,000 primary resolution and 15,000 secondary resolution. The dynamic exclusion time is 30 s to prevent duplicate analysis of ions. Proteomics data in RAW file format generated by mass spectrometry were searched and identified. Proteins were identified by using Proteome Discoverer Software 2.4 via the mouse database on the Uniprot website (http://www.uniprot.org) at an S/N threshold of 1.5, protein FDR <1% and peptide FDR <1%. Proteins were quantified using Proteome Discoverer Software 2.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Differential proteins were filtered at ploidy changes >1.5 or <0.67 and P < 0.05. Differential proteins are shown in Supporting Information Table S3.

2.15. Virtual docking

The atomic coordinates of TGFβR1 were extracted from 5E8X.pdb, a crystal structure of TGFβR1 complexed with the inhibitor staurosporine. AutoDock Vina (version 1.1.2) was conducted with TGFβR1 as the receptor, ITSN as the ligand and TGFβR1 kinase domain active site as the active pocket center (x = −14.382, y = −16.069, z = 9.663) for semi-flexible molecular docking according to default parameters to obtain the first 9 binding free energy results. The conformation with the lowest binding free energy was visualized by using PyMOL after docking.

2.16. Pull-down assay

The binding of ITSN to TGFβR1 was analyzed by using a pull-down assay with ITSN-conjugated Sepharose 6B beads. The MDA-MB-231 cell lysate (500 μg protein) or 100 ng active TGFβR1 protein was incubated with ITSN-Sepharose 6B beads (10 mmol/L) in reaction buffer. Only Sepharose 6B beads without ITSN were used as a control. After the overnight incubation at 4 °C with gentle shaking, wash buffer was used to wash beads five times. Proteins bound to beads were detected by immunoblotting.

2.17. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay

TGFβR1 (target protein) was coupled to the CM7 chip according to the Biacore T200 instruction and tested on the chip surface and under regenerative condition before being used for subsequent experiments. ITSN was serially diluted to 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.125, 1.5625 and 0.78125 μmol/L in PBS-P buffer containing 5% DMSO. Multi-cycle kinetic injection mode was used for the injection of samples. The concentration of 0 was subtracted from all data to acquire the final binding dissociation curve. Data were also imported into the Biacore evaluation software program and then analyzed for affinity and kinetic data.

2.18. Cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)

Cell lysates from TNBC cells were obtained by five repeated freeze–thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. Cell lysates were treated with or without ITSN for 1 h and then heated individually at different temperatures (49–64 °C) for 3 min followed by cooling on ice. The soluble lysates were centrifuged, and supernatants were detected by Western blot or ELISA.

2.19. Drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS)

Cells were lysed with lysis solution and divided into aliquots. Each aliquot was treated with ITSN (1000 nmol/L) or DMSO. After an additional 1 h incubation at room temperature, the ITSN or vector (DMSO) treated solution was divided into 40 μL and added to each tube, followed by 4 μL of pronase solution (pronase/protein ratio = 1:100, 1:300, 1:1000, 1:3000) in the tube. Samples were then individually digested in a Biosafer PCR machine (Safer Biotechnology Ltd., Nanjing, China) at 25 °C for 20 min. For undigested samples, the protease was replaced with the same volume of TNC buffer (50 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 10 mmol/L CaCl2, pH 8.0). The digestion reaction was then stopped by adding 4 μL of 20 × protease inhibitor cocktail, followed by the incubation on ice for 10 min. Finally, the samples were analyzed by Western blot.

2.20. TGFβR1 enzymatic activity assay

Enzyme, substrate, ATP and inhibitor were diluted according to TGFβR1 enzymatic activity Kit's instruction, and then incubated with ITSN at room temperature for 120 min, and then incubated with ADP-Glo reagent for 40 min at room temperature. Finally, kinase detection reagent was added and incubated with the above mixture for an additional 30 min at room temperature, and luminescence was recorded under an enzyme marker.

2.21. Bioinformatics analysis

RNA-sequencing expression profiles and corresponding clinical information for breast cancer including TNBC were downloaded from the TCGA dataset (https://portal.gdc.com). For Kaplan–Meier curves, P-values and hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval were generated by log-rank tests and univariate cox proportional hazards regression. All the analysis methods and R packages were implemented by R (foundation for statistical computing 2020) version 4.0.3. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.22. Flow cytometry for immune profiling

Mice were sacrificed, and tumor tissues were harvested. Single-cell suspensions were prepared by using buffer containing collagenase B and hyaluronidase. After digestion, the suspensions were filtered by 40 μm Nylon cell strainers. Before staining, cells were suspended in PBS and dyed by Fixable Viability Stain 700. Fluorescent staining was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Fluorescent antibodies recognizing murine CD45, CD3, CD8a, CD107a, Granzyme B, CD11b, MHC-Ⅱ, CD11c, CD206 and F4/80 were used in this assay. Flow cytometry was performed by using Beckman CytoFLEX LX. Flow cytometry data were analyzed by Flowjo v10.

2.23. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS inc.) was used to analyze the results. The significance of differences between groups was evaluated by one-way ANOVA with the LSD post hoc test, and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant difference. The correlations in the gene expression levels were analyzed by Pearson's rank correlation coefficients.

3. Results

3.1. ITSN reduced TNBC metastasis both in vivo and in vitro

To evaluate whether ITSN can abrogate TNBC cell migration, the wound healing assay was conducted in MDA-MB-231 and BT549 cells derived from human, and 4T1 cells derived from mouse. As shown in Fig. 1A, ITSN obviously reduced the wound closure of those above three TNBC cells in a concentration-dependent manner. Meanwhile, the invasion assay by using Transwell evidenced that ITSN decreased the invasion of those above three TNBC cells (Fig. 1B). Moreover, ITSN also markedly reduced the migration of those above three TNBC cells (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

ITSN reduced TNBC metastasis both in vitro and in vivo. ITSN reduced the wound closure (A), invasion (B) and migration (C) of TNBC cells (n = 3). (D) Representative images of BLI at 8 weeks after the injection of MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP cells, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 5). (E) Representative images of H&E staining of liver (n = 3). (F) Representative images of BLI at 8 weeks after the injection of BT549-luc-GFP cells, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 6). (G) Representative images of H&E staining of liver and lung (n = 3). (H) Representative images of BLI at 4 weeks after the injection of 4T1-luc-GFP cells, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 4–6). (I) Representative images of H&E staining of liver and lung (n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus cont.

To investigate the inhibition of ITSN on TNBC metastasis in vivo, three in situ tumor models (including mice bearing MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP, BT549-luc-GFP or 4T1-luc-GFP cells) were constructed. In vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) results displayed that ITSN obviously abrogated TNBC metastasis (Fig. 1D, F, H). Meanwhile, H&E staining results exhibited that ITSN reduced the elevated number of nodal foci of the metastasis of TNBC into liver or lung (Fig. 1E, G, I).

These above results clearly demonstrate that ITSN abrogated TNBC metastasis both in vivo and in vitro.

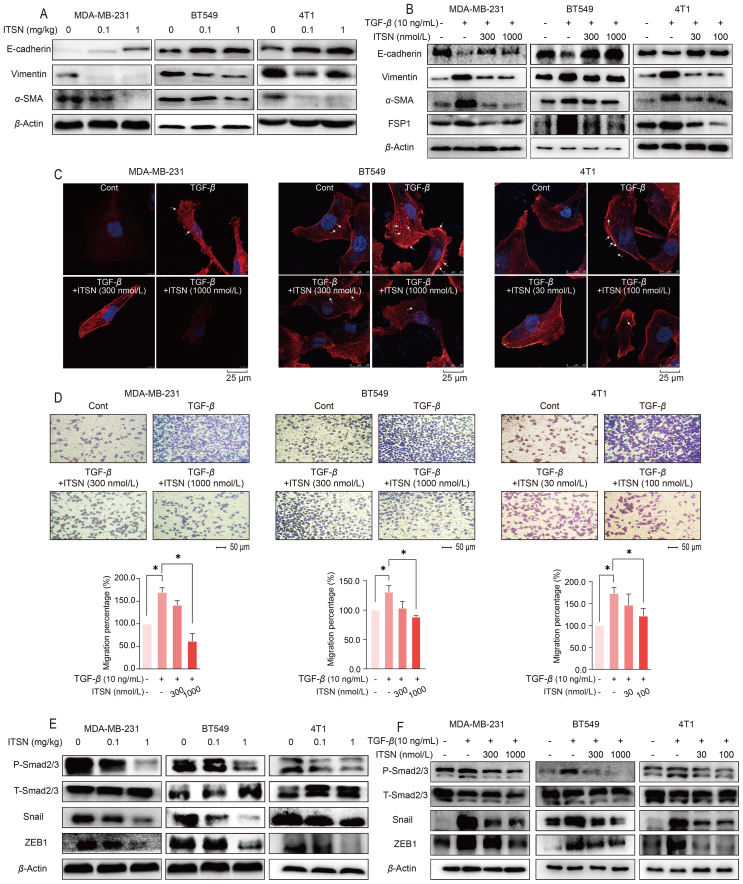

3.2. ITSN reversed EMT and the formation of invadopodia

RNA sequencing and proteomics technologies were used to screen signal pathways potentially involved in the ITSN-provided inhibition on TNBC metastasis. RNA-sequencing results suggested that ITSN might affect EMT and TGF-β signaling pathway, which was further confirmed by the results of proteomic assay (Supporting Information Fig. S3). Next, the expression of Vimentin, α-SMA and E-cadherin in TNBC tumor tissues and in TNBC cells treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) was observed. ITSN decreased the expression of Vimentin and α-SMA, and enhanced E-cadherin expression both in tumor tissues from mice and in TGF-β-treated TNBC cells (Fig. 2A and B). Moreover, ITSN also decreased FSP1 expression in TNBC cells stimulated with TGF-β (Fig. 2B). These results evidence that ITSN reversed EMT, which was consistent with the results from RNA-sequencing and proteomic assay.

Figure 2.

ITSN reversed EMT and the formation of invadopodia. (A) Protein expression of E-cadherin, Vimentin and α-SMA in tumor tissues from mice bearing TNBC cells (n = 3). (B) Protein expression of E-cadherin, Vimentin, α-SMA and FSP1 in TNBC cells stimulated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) (n = 3). (C) The invadopodia formation of TNBC cells was stained by phalloidin (n = 3). (D) ITSN decreased the migration of TNBC cells induced by TGF-β (10 ng/mL), and the statistical results are shown below (n = 3). (E) Protein expression of P-Smad2/3, T-Smad2/3, Snail and ZEB1 in tumor tissues from mice bearing TNBC cells (n = 3). (F) Protein expression of P-Smad2/3, T-SAMD2/3, Snail and ZEB1 in TNBC cells stimulated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) (n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05.

Invadopodia formation initiated by various signals including TGF-β has already been reported to promote tumor metastasis31. Given that ITSN inhibited the TGF-β-induced EMT, we examined whether it also blocked the TGF-β-induced invadopodia formation in TNBC cells by using laser confocal microscopy. The results display that ITSN prevented the formation of invadopodia in TNBC cells treated with TGF-β (Fig. 2C). What's more, the TGF-β-induced migration of TNBC cells was also decreased by ITSN (Fig. 2D). EMT and metastasis of cancer cells is highly dependent on the transcriptional activation of Smad2/3, Snail or ZEB18. As shown in Fig. 2E and F, ITSN markedly decreased the phosphorylation of Smad2/3 and the expression of Snail and ZEB1 in tumor tissues from mice bearing TNBC cells as well as in three TNBC cells stimulated with TGF-β (Fig. 2E and F).

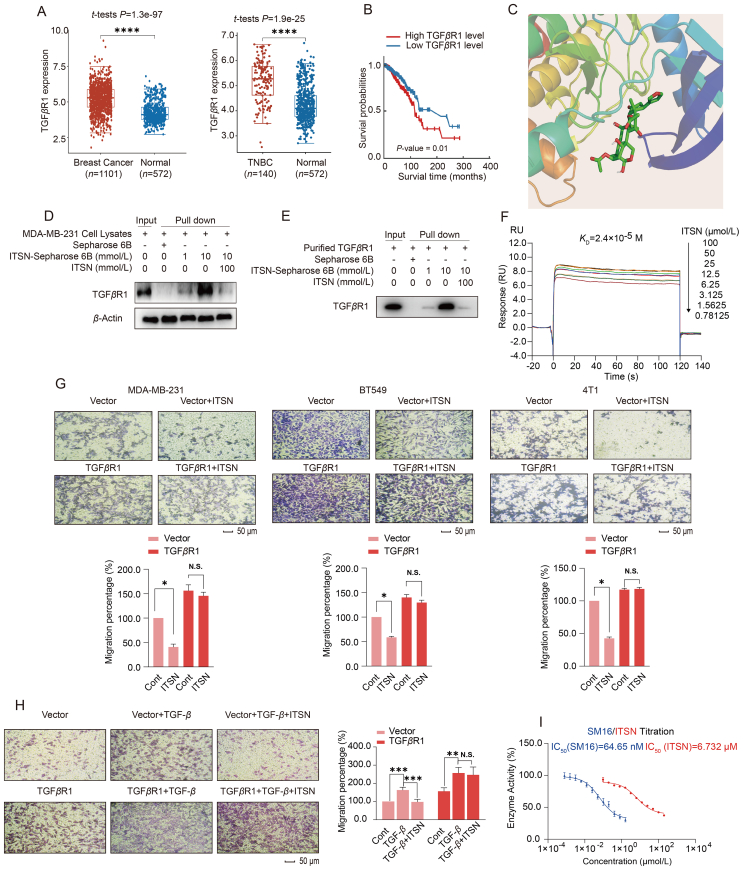

3.3. ITSN directly interacted with TGFβR1

Results in Fig. 2 demonstrate that ITSN inhibited the TGF-β-induced EMT in TNBC cells. However, ITSN didn't alter the protein expression of TGF-β itself and its two receptors including TGFβR1 and TGFβR2 in MDA-MB-231, BT549 or 4T1 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S4). How did ITSN inhibit the TGF-β signaling pathway? RNA sequencing data downloaded from the TCGA database revealed that TGFβR1 expression was significantly higher in breast cancer patients, especially in TNBC tissues, than in normal tissues, and its expression was also negatively correlated with breast cancer patient's survival rate (Fig. 3A and B), implying that TGFβR1 may be crucial for TNBC metastasis. To find the concrete target of ITSN, ITSN was immobilized on Sepharose 6B beads, and then a pull-down assay followed by a global analysis of ITSN-binding proteins in MDA-MB-231 cell lysates was conducted by using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. TGFβR1 was found to be the top enriched protein (Supporting Information Fig. S5). A virtual docking showed that the binding affinity of ITSN with TGFβR1 is −8.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

ITSN directly interacted with TGFβR1. (A) The differential expression of TGFβR1 in samples from breast cancer patients (n = 1101) and TNBC patients (n = 140) versus normal people (n = 572) in the TCGA database. (B) The survival curve of breast cancer patients with different levels of TGFβR1 expression in the TCGA database (n = 1101). (C) Virtual docking of ITSN and TGFβR1. (D) Pull-down assay was used to detect the binding of ITSN to TGFβR1 protein in MDA-MB-231 cell lysates (n = 3). (E) Pull-down assay was used to detect the binding of ITSN with recombinant TGFβR1 protein (n = 3). (F) SPR assay. (G) The effect of ITSN on the migration of TNBC cells with or without TGFβR1 overexpression, and the statistical results are shown below (n = 3). The used concentration of ITSN on MDA-MB-231 and BT549 cells was 1000 nmol/L, and on 4T1 cells was 100 nmol/L. (H) The effect of ITSN (1000 nmol/L) on the migration of MDA-MB-231 cells with or without TGFβR1 overexpression after the stimulation with TGF-β (10 ng/mL), and the statistical results are shown right (n = 3). (I) The kinase activity of TGFβR1 was analyzed, and SM16 was used as a positive control (n = 3). DMSO was used as the vehicle control. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. N.S. indicates no significant difference.

Temperature-dependent and concentration-dependent CETSA showed that ITSN affected the thermal stability of TGFβR1 protein (Supporting Information Fig. S6). In addition, a DARTS assay was carried out in TNBC cells. In DARTS, when a small molecule binds to a target protein, it produces a stable conformational structure that inhibits the degradation of the target protein by pronase32. Experimental results showed that ITSN specifically inhibited the degradation of TGFβR1 by pronase, but did not affect the degradation of both TGFβR2 and β-actin (Supporting Information Fig. S7). To further validate the binding of ITSN with TGFβR1, a pull-down assay was carried out with purified TGFβR1 protein and MDA-MB-231 cell lysates. The experimental results exhibited that Sepharose 6B beads fixed with ITSN could pull down TGFβR1 protein in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas the high concentration of free ITSN interfered this binding due to its competitive binding to TGFβR1 (Fig. 3D and E). SPR assay displayed that ITSN concentration-dependently responded to the TGFβR1 immobilized on a solid-phase carrier with a dissociation constant (KD) of 2.4 × 10−5 mol/L (Fig. 3F). All these results indicate that ITSN can directly bind to TGFβR1 in TNBC cells, which contributes to its inhibition on TGF-β signal pathway.

To investigate whether TGFβR1 was the key target for the ITSN-provided inhibition on TNBC metastasis, TGFβR1 was overexpressed in MDA-MB-231, BT549 or 4T1 cells, respectively. ITSN (1000 or 100 nmol/L) effectively inhibited the migration of these three TNBC cells transfected with vector control, but this inhibition totally disappeared in TNBC cells overexpressed TGFβR1 (Fig. 3G). Moreover, ITSN (1000 nmol/L) also abrogated the TGF-β-induced cell migration when MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with vector control, but this abrogation disappeared when cells were transfected with TGFβR1 (Fig. 3H). In addition, ITSN also decreased the kinase activity of TGFβR1 in vitro, with TGFβR1 chemical inhibitor SM16 used as the positive control (Fig. 3I). The IC50 value of ITSN on the inhibition of TGFβR1 kinase activity is 6.732 μmol/L (Fig. 3I). We also tested whether ITSN will affect the kinase activity of AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (AKT) and protein kinase A (PKA), which are both serine/threonine kinases like TGFβR1 and are also ATP-dependent kinases33,34. The results show that ITSN did not affect the kinase activity of AKT or PKA (Supporting Information Fig. S8). All these results indicate that TGFβR1 was crucial for the ITSN-provided inhibition on TNBC metastasis in vitro.

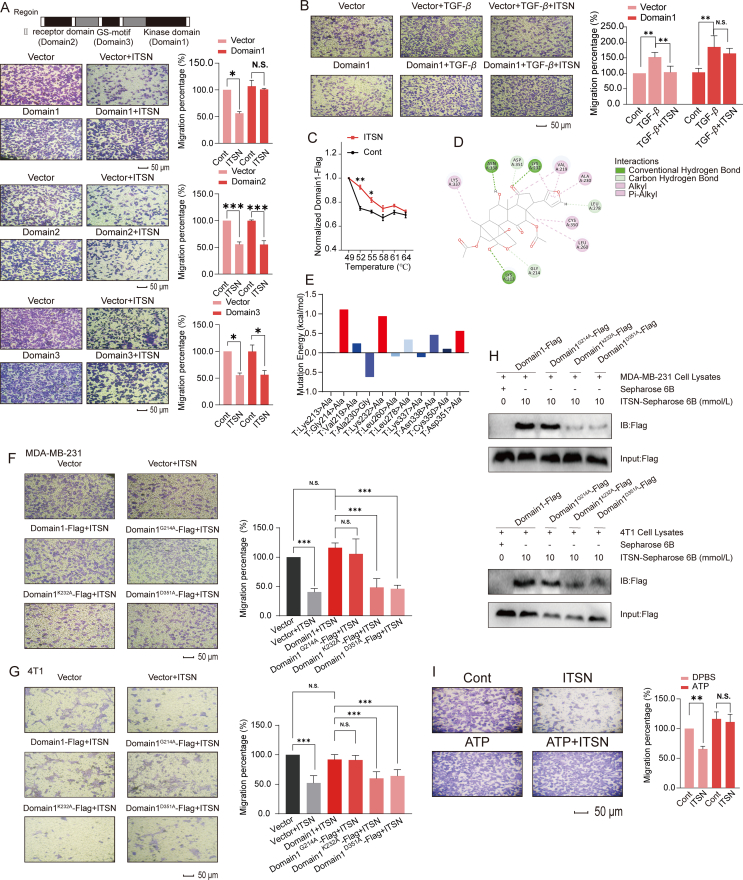

3.4. ITSN could bind to Lys232 and Asp351 residues in the kinase domain of TGFβR1

Next, the potential site where ITSN interacts with TGFβR1 was investigated. According to the previous literature, TGFβR1 has three highly conserved domains, namely TGFβR2 domain, GS-motif and kinase domain35. Therefore, we constructed truncated variants of TGFβR2 domain, GS-motif and kinase domain, and overexpressed them in BT549 cells, respectively. Cell migration assay showed that the overexpression of the kinase domain of TGFβR1 (Domain 1) alone could effectively block the anti-migratory effect of ITSN (1000 nmol/L), but the overexpression of TGFβR2 domain (Domain 2) or GS-motif (Domain 3) did not have this function (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, ITSN (1000 nmol/L) also abrogated the TGF-β-induced BT549 migration when cells were transfected with vector control, but this abrogation was disappeared when cells were transfected with the kinase domain (Domain 1) of TGFβR1 (Fig. 4B). Next, the result of CETSA show that ITSN effectively increased the thermal stability of the kinase domain of TGFβR1, indicating a direct binding between ITSN with the kinase domain (Fig. 4C). Results of virtual docking imply that ITSN forms hydrogen bonds with residues including Lys213, Gly214, Leu278, Lys232, Asp351 and Asn338 in the catalytic pocket of TGFβR1 (Fig. 4D), but the results of virtual mutations indicate that only the mutation of residues including Gly214, Lys232 or Asp351 to alanine affect the binding between ITSN with TGFβR1 (Fig. 4E). Next, Gly214, Lys232 or Asp351 residues in the kinase domain of TGFβR1 was mutated to alanine, and overexpressed in MDA-MB-231 or 4T1 cells. Data in Fig. 4F and G displays that the overexpression of the kinase domain of TGFβR1 obviously reversed the anti-migratory effect of ITSN, and this phenomenon was diminished in TNBC cells overexpressed with TGFβR1 kinase domain with the mutation of Lys232 or Asp351 residue, but not Gly214. Moreover, the content of the Flag-labelled TGFβR1 kinase domain with the mutation of Lys232 or Asp351 residue but not Gly214 was obviously reduced in cell lysates pulled down by ITSN-Sepharose (Fig. 4H). Next, CESTA results show that ITSN still affects the thermal stability of the TGFβR1 kinase domain with the mutation of Gly214, but ITSN no longer affects the thermal stability of TGFβR1 kinase domain with the mutation of Lys232 or Asp351 (Supporting Information Fig. S9). Since Lys232 and Asp351 residues were both included in the ATP binding site of TGFβR1, we further tested whether excess ATP could competitively inhibit the anti-migratory effect of ITSN. The results show that the addition of ATP obviously inhibited the anti-migratory effect of ITSN (Fig. 4I). These results evidence that Lys232 and Asp351 residues are critical for the binding of ITSN to TGFβR1.

Figure 4.

ITSN could bind to Lys232 and Asp351 in the kinase domain of TGFβR1. (A) BT549 cells overexpressed with three truncated mutants of TGFβR1 were incubated with ITSN (1000 nmol/L), and cell migration was detected, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 3). (B) BT549 cells overexpressed with the truncated kinase domain of TGFβR1 (Domain 1) were pre-incubated with ITSN (1000 nmol/L) and further stimulated with TGF-β, and then cell migration was detected, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 3). (C) MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressed the truncated kinase domain (Domain 1). CETSA was used to detect the effect of ITSN (1000 nmol/L) on the thermal degradation of truncated kinase domain in MDA-MB-231 cell lysates. Cell lysates were analyzed by using ELISA with the Flag antibody (n = 3). (D) Virtual docking analysis. Green represents hydrogen bonding. Pink represents hydrophobic interactions. (E) Virtual mutation analysis was used to predict the potential sites in TGFβR1 where ITSN can interact with TGFβR1. (F) Migration assay in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with or without ITSN (1000 nmol/L). MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressed Domain1-Flag, Domain1G214A-Flag, Domain1K232A-Flag or Domain1D351A-Flag, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 3). (G) Migration assay in 4T1 cells treated with or without ITSN (100 nmol/L). 4T1 cells overexpressed Domain1-Flag, Domain1G214A-Flag, Domain1K232A-Flag and Domain1D351A-Flag, respectively, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 3). (H) Pull-down analysis. MDA-MB-231 or 4T1 cells overexpressed Domain1-Flag, Domain1G214A-Flag, Domain1K232A-Flag and Domain1D351A-Flag, respectively (n = 3). (I) MDA-MB-231 cells were stimulated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL), then stimulated with ATP (50 μmol/L) or an equal volume of DPBS, then treated with ITSN (1000 nmol/L). Cell migration was detected, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 3). DMSO was used as the vehicle control. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. N.S. indicates no significant difference.

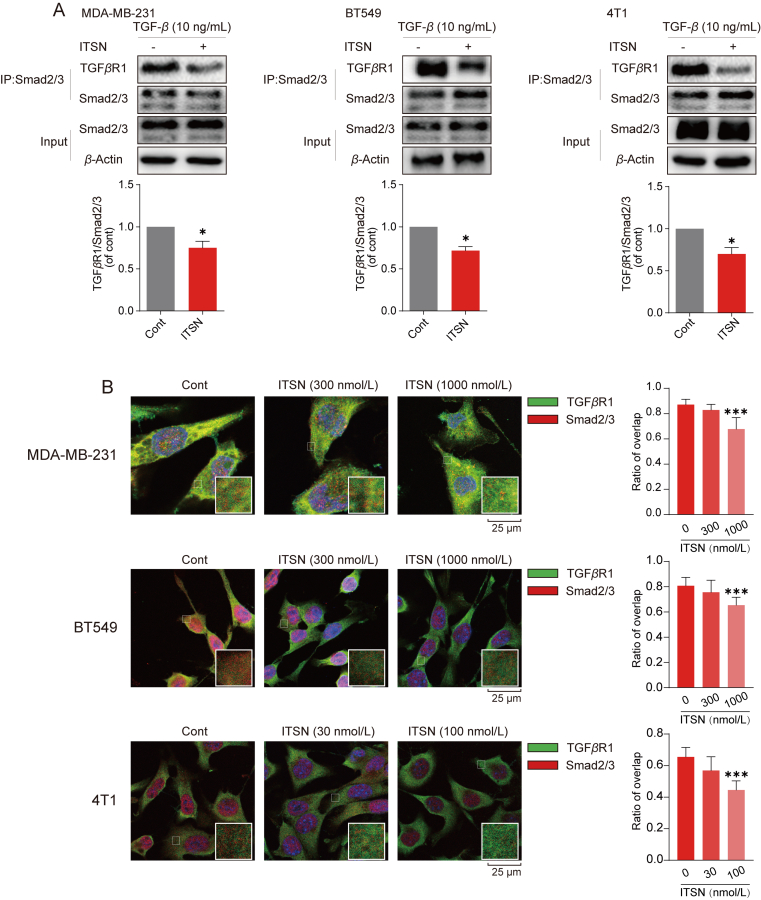

3.5. ITSN reduced the binding of Smad2/3 with TGFβR1

It has been reported that the binding of Smad2/3 to the TGFβR1 kinase domain is essential for its phosphorylated activation35. Since ITSN was found to interact with the kinase domain of TGFβR1, we hypothesized that it could interfere with the interaction of TGFβR1 with Smad2/3, but not with TGFβR2. Cell extracts from ITSN-treated TNBC cells were immunoprecipitated by using Smad2/3 antibody, and then the expression of TGFβR1 was detected. TGFβR1 protein expression in TNBC cells with the incubation of ITSN was lower than in cells without ITSN treatment, implying that ITSN decreased the interaction between TGFβR1 with Smad2/3 (Fig. 5A). Additionally, cell extracts from BT549 and 4T1 cells treated with or without ITSN were immunoprecipitated by using TGFβR1 antibody, and then the expression of TGFβR2 was detected. Data in Supporting Information Fig. S10 show that the expression of TGFβR2 immunoprecipitated by using TGFβR1 antibody showed no alternation in cells treated with or without ITSN treatment. Next, the confocal immunofluorescent analysis was used to detect the co-localization of TGFβR1 and Smad2/3 in TNBC cells. ITSN obviously weakened the intensity of the merged fluorescence signal came from the overlapping of TGFβR1 and Smad2/3 in TNBC cells (Fig. 5B). In conclusion, ITSN specifically inhibited the binding of TGFβR1 to Smad2/3.

Figure 5.

ITSN reduced the binding of Smad2/3 with TGFβR1. MDA-MB-231 and BT549 cells were incubated with ITSN (1000 nmol/L), and 4T1 cells were incubated with ITSN (100 nmol/L) for 24 h. (A) Co-immunoprecipitation assay was used to detect the binding of TGFβR1 with Smad2/3, and the statistical results are shown below (n = 3). (B) Co-localization of TGFβR1 (green) and Smad2/3 (red) was detected by immunofluorescence analysis, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 3). DMSO was used as the vehicle control. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus cont.

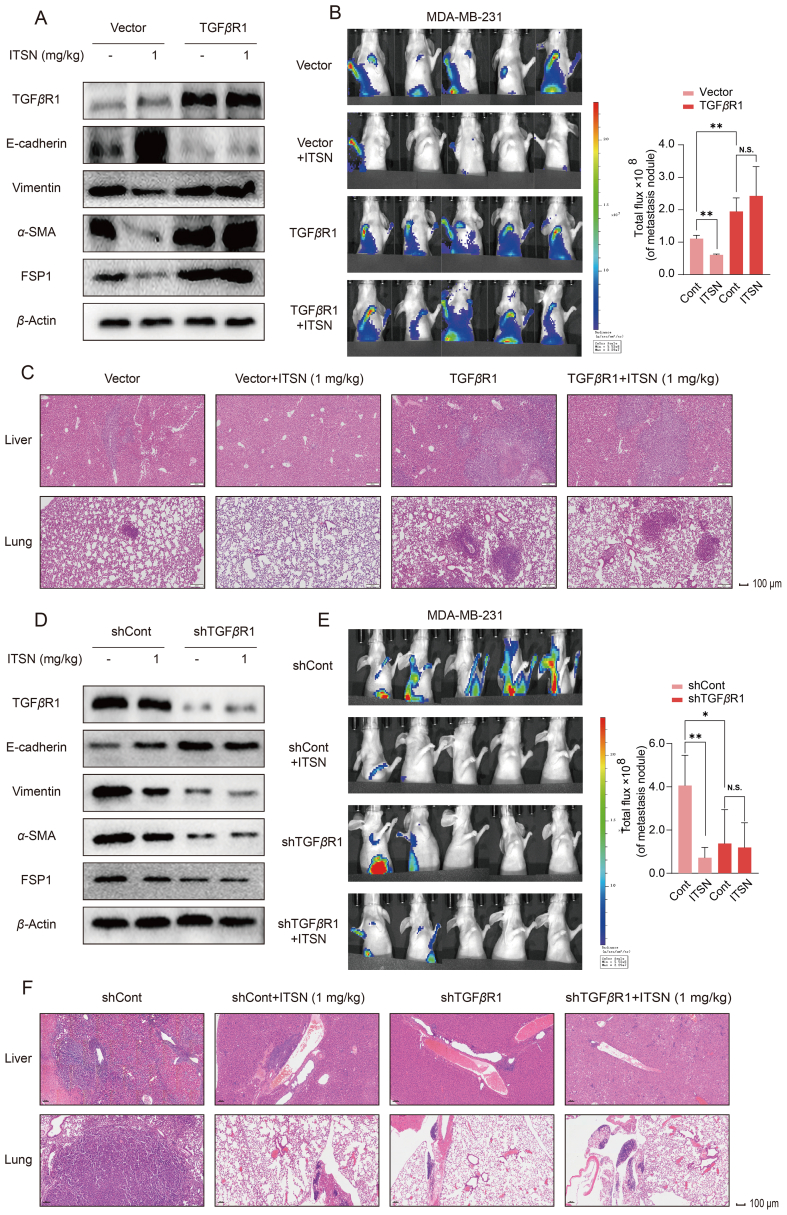

3.6. The suppression of ITSN on TNBC metastasis in vivo was TGFβR1-dependent

To further investigate whether TGFβR1 was critical for the ITSN-provided inhibition on TNBC metastasis in vivo, in situ TNBC tumor model was established in mice bearing TGFβR1-overexpression or TGFβR1-knockdown MDA-MB-231 cells constructed by using lentivirus. As shown in Fig. 6A, TGFβR1's expression was obviously enhanced in tumor tissues from mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressed TGFβR1. Also, ITSN (1 mg/kg) reversed EMT (the expression of Vimentin, α-SMA and FSP1 was decreased, but the expression of E-cadherin was enhanced) in tumor tissues from mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with control vector, but this phenomenon was totally disappeared in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressed TGFβR1. Meanwhile, the EMT was more serious in tumor tissues from mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressed TGFβR1 than from mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with control vector (Fig. 6A). Data in Fig. 6B show that ITSN (1 mg/kg) obviously abrogated TNBC metastasis in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with control vector, but this inhibition provided by ITSN was disappeared in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressed TGFβR1. Moreover, results from H&E staining show that the ITSN-provided inhibition on the increased metastatic TNBC nodal foci in liver and lung totally disappeared in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressed TGFβR1 (Fig. 6C). Additionally, the metastasis of TNBC was also more serious in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressed TGFβR1 than in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with control vector (Fig. 6B and C).

Figure 6.

The suppression of ITSN on TNBC metastasis in vivo was TGFβR1-dependent. (A) Protein expression of TGFβR1, E-cadherin, Vimentin, α-SMA and FSP1 in tumor tissues from mice bearing MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP-Vector or MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP-TGFβR1 cells (n = 3). (B) Representative images of BLI at 8 weeks after the injection of cells, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 5). (C) Representative images of H&E staining of liver and lung (n = 3). (D) Protein expression of TGFβR1, E-cadherin, Vimentin, α-SMA and FSP1 in tumor tissues from mice bearing MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP-shCont or MDA-MB-231-luc-GFP-shTGFβR1 cells (n = 3). (E) Representative images of BLI at 8 weeks after the injection of cells, and the statistical results are shown right (n = 5). (F) Representative images of H&E staining of liver and lung (n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. N.S. indicates no significant difference.

As shown in Fig. 6D, TGFβR1's expression was obviously decreased in tumor tissues from mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells with TGFβR1 knockdown. Also, the expression of Vimentin, α-SMA and FSP1 was decreased, but the expression of E-cadherin was elevated in tumor tissues from mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells with TGFβR1 knockdown (Fig. 6D). These results demonstrate that just like ITSN, the knockdown of TGFβR1 in TNBC cells could also reverse EMT in vivo. Just like in ITSN-treated mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with control vector, TNBC metastasis was obviously reduced in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells with TGFβR1 knockdown whatever mice were given with ITSN or without ITSN (Fig. 6E). Similarly, the increased metastatic TNBC nodal foci in liver and lung was also decreased in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells with TGFβR1 knockdown whatever mice were given with ITSN or without ITSN (Fig. 6F).

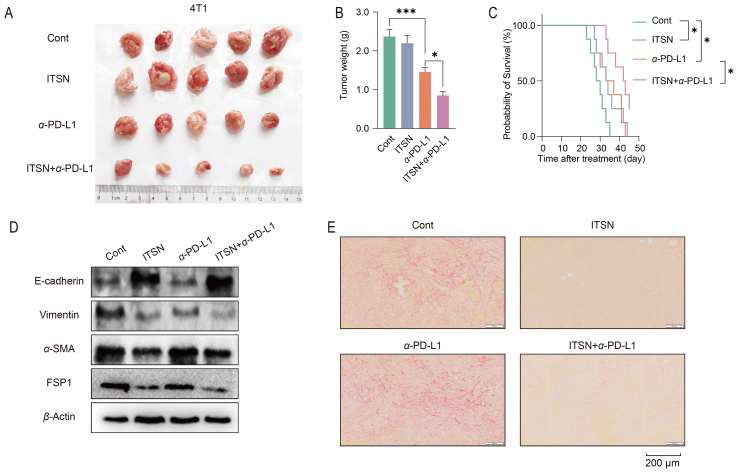

3.7. ITSN improved the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 therapy for TNBC in vivo

Only a small proportion of patients with TNBC can benefit from anti-PD-L1 therapy36. This is attributed to the fact that cytotoxic T cells cannot infiltrate well into the tumor tissues, and the reverse of EMT and the alleviation of collagen deposition in tumor microenvironment may be helpful for its infiltration37. The combination of anti-PD-L1 with ITSN in vivo obviously aggravated the inhibition on the growth of TNBC provided by anti-PD-L1 alone; and also prolonged the survival time of mice bearing 4T1 cells (Fig. 7A–C). Both ITSN and ITSN combined with anti-PD-L1 reversed EMT in tumor tissues from mice bearing 4T1 cells, but anti-PD-L1 alone didn't have this function (Fig. 7D). Next, the Sirius red staining assay was conducted to detect the collagen deposition in the tumor microenvironment. The results show that both ITSN and the combination therapy were effective in reducing collagen deposition in tumor tissues as compared to control or anti-PD-L1 alone (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7.

ITSN improved the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 therapy for TNBC in vivo. Mice bearing 4T1 cells received the treatment of combination therapy (1 mg/kg/day ITSN and 6.6 mg/kg/week α-PD-L1) or monotherapy (1 mg/kg/day ITSN or 6.6 mg/kg/week α-PD-L1). (A) Images of tumors (n = 5). (B) Tumor weight (n = 5). (C) The overall survival curve of mice. BALB/c mice were challenged with 5 × 105 4T1 cells on Day 0. Therapy was initiated on Day 7 (8 mice for each group). The survival status of mice was monitored for 45 days (n = 8). (D) Expression of EMT-associated proteins and (E) collagen deposition was detected by using Sirius red staining assay in tumor tissues from mice bearing 4T1 cells (n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

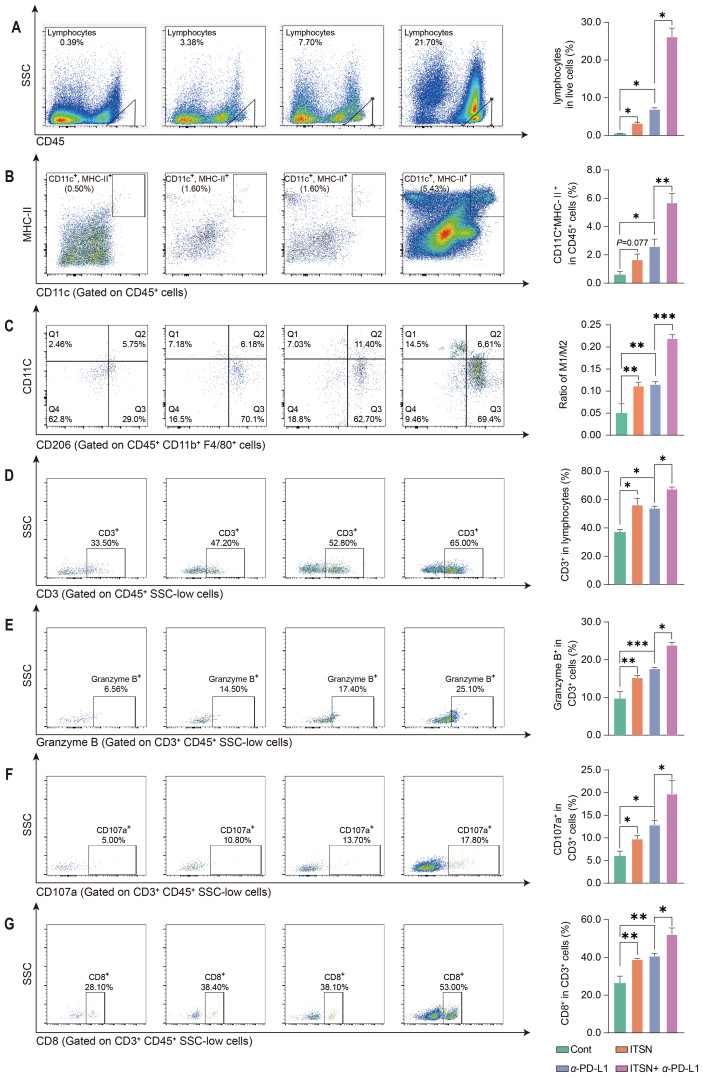

Data in Fig. 8A exhibit that the combination of anti-PD-L1 with ITSN enhanced the number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). The combination of anti-PD-L1 with ITSN increased the density of DCs (Fig. 8B) and the ratio of M1-like macrophages to M2-like macrophages (Fig. 8C) in tumors as compared to anti-PD-L1 alone. The combination of anti-PD-L1 with ITSN enhanced the density of cytotoxic T cells including CD3+ T cells (Fig. 8D), Granzyme B+ T cells (Fig. 8E), CD107a+ T cells (Fig. 8F) and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 8G) in tumors as compared to anti-PD-L1 alone.

Figure 8.

ITSN promoted the infiltration of immune cells into the tumor microenvironment. Representative images of TILs (A), DCs (B), macrophages (C), T cells (D), Granzyme B+ T cells (E), CD107a+ T cells (F) and CD8+ T cells (G). The statistical results are shown right (n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

In vivo imaging, circulating tumor cells (CTCs) counting and H&E staining showed that the combination treatment somewhat reduced the bioluminescence intensity (P = 0.075) and the number of CTCs (P = 0.075) as well as the number of foci of metastases in the liver and lung compared to monotherapy (Supporting Information Fig. S11).

4. Discussion

In our previous study, natural triterpenoid ITSN was found to inhibit TNBC growth for the first time30. In this study, we characterized ITSN as a validated TGFβR1 inhibitor from both in vivo and in vitro experiments. ITSN not only reduced TNBC metastasis but also enhanced the inhibitory efficacy of anti-PD-L1 on TNBC growth through reversing the TGF-β-induced EMT.

ITSN is an analogue of toosendanin (TSN), and many reports have displayed that TSN has promising antitumor efficacy in various cancers including osteosarcoma, non-small-cell lung carcinoma, liver cancer, colorectal cancer, glioblastoma, and so on38. However, TSN was also reported to have obvious hepatotoxicity39,40, which will limit its further development into a drug to some extent. Our previous study showed that ITSN's cytotoxicity (IC50 was 1294.23 μmol/L) in human normal L-02 hepatocytes was obviously weaker than TSN's (IC50 was 3.331 μmol/L). However, ITSN has the same inhibitory effect as TSN on TNBC growth in vivo30. There was no obvious adverse effect when ITSN (30 mg/kg) was orally given to 4T1 tumor-bearing mice continuously for 5 weeks30, and this dose is much higher than the anti-metastatic dose of ITSN (1 mg/kg). Our preliminary results showed that the anti-metastatic effect of ITSN in TNBC tumor-bearing mice was also almost the same as TSN (data not shown). Thus it can be seen that ITSN has more potential than TSN to be developed as a candidate drug for TNBC treatment.

TGF-β signaling pathway is often hyperactive in the TNBC microenvironment and is associated with the progression of TNBC41. Results from RNA sequencing and proteomic assay hint that TGF-β signaling pathway may participate in the ITSN-provided inhibition on TNBC metastasis. As a secreted cytokine, TGF-β drives the progression of many tumors including TNBC not only through its pro-angiogenic and immunosuppressive effects but also perhaps because that it is an inducer of EMT8,9,11. EMT refers to the dynamic change of cell phenotype from epithelial to mesenchymal, leading to the changed capacity of migration and invasion42. TGF-β is responsible for the activation of some EMT-associated transcription factors like Snail, Slug, ZEB1, ZEB2 and Twist through triggering both Smad2/3 and non-Smad2/3 signaling pathways, therefore it is an important inducer for EMT and is crucial for regulating tumor progression43,44. A previous study has demonstrated that TSN weakened the TGF-β-induced EMT in lung cancer cells45. Invadopodia are F-actin-rich membrane protrusions that exert the capacity to degrade extracellular matrix, thereby promoting tumor invasion46. In addition to EMT, invadopodia formation was also crucial for the TGF-β-induced tumor metastasis and was found in many aggressive cancers31,47. Recent evidences have also demonstrated a direct association between invadopodia formation and tumor metastasis both in experimental mice and clinical patients48,49. In this study, our results show that ITSN inhibited TGF-β-induced EMT and invadopodia formation both in vivo and in vitro, which further confirmed its inhibition on TGF-β signaling pathway.

TGF-β signaling pathway is activated when TGF-β interacts with the tetrameric cell surface complexes of type II and type I transmembrane kinase receptors named TGFβR2 and TGFβR150. The binding of TGF-β with TGFβR2 activates the TGFβR1 by leading to its phosphorylation, and TGFβR1 further phosphorylates the intracellular molecules including Smad2 and Smad3 proteins. Then, Smad2/3 proteins were associated with Smad4 to form a trimeric complex that was translocated into the nucleus and regulated the expression of downstream genes51. The pull-down assay combined with proteomic analysis identified TGFβR1 as a candidate target for ITSN. Further results from virtual docking, the pull-down assay combined with Western blot, SPR, CETSA and DARTS all evidenced the direct interaction of ITSN with TGFβR1. Interestingly, ITSN had no inhibition on cell migration in TNBC cells overexpressed TGFβR1, and ITSN was also unable to exert anti-metastatic activity in mice bearing TNBC cells overexpressed TGFβR1. More importantly, the ITSN-provided inhibition on EMT in tumor tissues disappeared in mice bearing TNBC cells overexpressed TGFβR1. Moreover, TNBC metastasis and EMT were obviously reduced in mice bearing TNBC cells with TGFβR1 knockdown. All these results clearly demonstrated that TGFβR1 as the direct target of ITSN was crucial for its inhibition on TNBC metastasis.

By performing truncated mutants and amino acid point mutations on the TGFβR1 protein, we identified that the kinase domain of TGFβR1 and residues including Lys232 and Asp351 are critical for the interaction of ITSN with TGFβR1. A previous study has already shown that when the catalytic salt bridge between Asp245 and Lys232 was broken, it will keep TGFβR1 in an inactive conformation35. The salt bridge between Arg372 and Asp351 also affects the binding of ATP to the kinase domain of TGFβR135. This may be a key reason why ITSN decreased TGFβR1 kinase activity. Also, our results further evidence that ATP could reverse the ITSN-provided inhibition on TNBC cell migration. These results display that ITSN could compete with ATP for the TGFβR1 binding site, thereby inhibiting the binding of TGFβR1 to Smad2/3 and abrogating the TGF-β signaling pathway.

Although the number of cancer patients treated with immunotherapy is steadily increasing, only 12.5% of patients currently benefit from it36. According to the state of tumor microenvironment, tumors can be classified into three phenotypes: immunoinflammatory, immune desert and immune rejection. Immunoinflammatory tumors are the most likely to respond to PD-1/PD-L1 therapy, whereas the other two phenotypes were rarely responsive17. Normalizing the dysregulated TGF-β signaling in the tumor microenvironment was reported to be helpful for the infiltration of cytotoxic T-cells into tumors, thereby restoring the immunosuppressed tumor to immunoinflammatory tumor25,26,52,53. Previous studies have shown that bispecific antibodies targeting both TGF-β and PD-L1 had better efficacy for breast cancer, and the reason is that because bispecific antibodies enhanced the number of TILs and DCs, elevated the ratio of M1/M2 and increased cytokine production from T cells54,55. Recently, some clinical trials of the TGF-β inhibitor combined with anti-PD-L1 had not achieved the ideal endpoint. For example, the clinical trials of Bintrafusp alfa, a bifunctional fusion protein composed of the extracellular domain of TGFβR2 (a TGF-β “trap”) and PD-L1 antibody56, for metastatic biliary tract cancer and non-small-cell lung carcinoma were both terminated in 2021 due to its failure to meet the primary endpoint. But it is encouraging that clinical trials of Bintrafusp alfa for TNBC are still ongoing57. Antibody drugs may be more effective against haematological tumors than against solid tumors, which may be probably because of their poor ability to penetrate into solid tumors58.

In contrast, the small chemical compound can enter tumor tissues more easily than macromolecules like antibody drugs. Chidamide enhanced tumor immunogenicity and promoted the infiltration of immune cells into the TNBC, thereby enhancing the therapeutic effect of PD-L1 antibody59. Oxymatrine was found to enhance the therapeutic efficacy provided by a PD-L1 antibody through promoting the infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the tumor in a lung adenocarcinoma mice model60. In this study, natural compound ITSN as a TGFβR1 inhibitor was also found to enhance the therapeutic efficacy against TNBC growth in vivo provided by anti-PD-L1 via improving the tumor microenvironment. Therefore, the combination of natural compounds with PD-L1 antibody may be an effective strategy to resolve the lack of immune infiltration of anti-PD-L1 therapy.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that natural compound ITSN is a novel chemical inhibitor of TGFβR1 through directly interacting with the kinase domain of TGFβR1, thereby abrogating the TGF-β-induced EMT in the TNBC microenvironment. The ITSN-provided reduced EMT in the tumor microenvironment not only blocked TNBC metastasis but also enhanced the inhibitory efficacy of PD-L1 antibody on TNBC growth.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Xiaojun Wu (Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine) for assistance in completing the SPR assay. The authors thank KangChen Bio-tech (China) for assistance with RNA sequencing. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82273994) and the leadership in the Science and National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC1707302).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.05.006.

Author contributions

Jingnan Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing-Original Draft. Ze Zhang: Methodology, Investigation, Validation. Zhenlin Huang: Validation, Formal analysis. Manlin Li: Methodology, Investigation. Fan Yang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization. Zeqi Wu: Investigation. Qian Guo: Investigation. Xiyu Mei: Investigation. Bin Lu: Methodology. Changhong Wang: Writing-Review & Editing. Zhengtao Wang: Writing-Review & Editing. Lili Ji: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing-Review & Editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fuchs H.E., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harbeck N., Gnant M. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2017;389:1134–1150. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31891-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yagata H., Kajiura Y., Yamauchi H. Current strategy for triple-negative breast cancer: appropriate combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Breast Cancer. 2011;18:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s12282-011-0254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dent R., Hanna W.M., Trudeau M., Rawlinson E., Sun P., Narod S.A. Pattern of metastatic spread in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:423–428. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassam F., Enright K., Dent R., Dranitsaris G., Myers J., Flynn C., et al. Survival outcomes for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: implications for clinical practice and trial design. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9:29–33. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2009.n.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stecklein S.R., Jensen R.A., Pal A. Genetic and epigenetic signatures of breast cancer subtypes. Front Biosci. 2012;4:934–949. doi: 10.2741/E431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steeg P.S. Targeting metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:201–218. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massagué J. TGFβ in cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikushima H., Miyazono K. TGFβ signalling: a complex web in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:415–424. doi: 10.1038/nrc2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian W., Li J.T., Wang Z., Zhang T., Han Y., Liu Y.Y., et al. HYD-PEP06 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like properties by inhibiting PI3K/AKT and WNT/β-catenin signaling activation. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:1592–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J., Lamouille S., Derynck R. TGFβ-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res. 2009;19:156–172. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lei X.P., Li Z., Zhong Y.H., Li S.P., Chen J.C., Ke Y.Y., et al. Gli1 promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition and metastasis of non-small cell lung carcinoma by regulating snail transcriptional activity and stability. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:3877–3890. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammad K.S., Javelaud D., Fournier P.G., Niewolna M., McKenna C.R., Peng X.H., et al. TGFβRI kinase inhibitor SD-208 reduces the development and progression of melanoma bone metastases. Cancer Res. 2011;71:175–184. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y.Y., Hu Q.F., Li W.S., Liu S.J., Li K.M., Li X.Y., et al. Simultaneous blockage of contextual TGFβ by cyto-pharmaceuticals to suppress breast cancer metastasis. J Control Release. 2021;336:40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbertz S., Sawyer J.S., Stauber A.J., Gueorguieva I., Driscoll K.E., Estrem S.T., et al. Clinical development of galunisertib (LY2157299 monohydrate), a small molecule inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2015;9:4479–4499. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S86621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandyopadhyay A., Agyin J.K., Wang L., Tang Y.P., Lei X.F., Story B.M., et al. Inhibition of pulmonary and skeletal metastasis by a transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor kinase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6714–6721. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen D.S., Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature. 2017;541:321–330. doi: 10.1038/nature21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verma V., Sharma G., Singh A. Immunotherapy in extensive small cell lung cancer. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2019;8:5. doi: 10.1186/s40164-019-0129-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motzer R.J., Escudier B., McDermott D.F., George S., Hammers H.J., Srinivas S., et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robert C., Schachter J., Long G.V., Arance A., Grob J.J., Mortier L., et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu X.D., Sun H.C. Emerging agents and regimens for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:110. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0794-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emens L.A. Breast cancer immunotherapy: facts and hopes. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:511–520. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chrétien S., Zerdes I., Bergh J., Matikas A., Foukakis T. Beyond PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition: what the future holds for breast cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2019;11:628. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Abreo N., Adams S. Immune-checkpoint inhibition for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: safety first?. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:399–400. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mariathasan S., Turley S.J., Nickles D., Castiglioni A., Yuen K., Wang Y.L., et al. TGFβ attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature. 2018;554:544–548. doi: 10.1038/nature25501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tauriello D.V.F., Palomo-Ponce S., Stork D., Berenguer-Llergo A., Badia-Ramentol J., Iglesias M., et al. TGFβ drives immune evasion in genetically reconstituted colon cancer metastasis. Nature. 2018;554:538–543. doi: 10.1038/nature25492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanamori M., Nakatsukasa H., Okada M., Lu Q.J., Yoshimura A. Induced regulatory T cells: their development, stability, and applications. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park B.V., Freeman Z.T., Ghasemzadeh A., Chattergoon M.A., Rutebemberwa A., Steigner J., et al. TGFβ1-mediated Smad3 enhances PD-1 expression on antigen-specific T cells in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:1366–1381. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas D.A., Massagué J. TGF-β directly targets cytotoxic T cell functions during tumor evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J.N., Yang F., Mei X.Y., Yang R., Lu B., Wang Z.T., et al. Toosendanin and isotoosendanin suppress triple-negative breast cancer growth via inducing necrosis, apoptosis and autophagy. Chem Biol Interact. 2022;351 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pignatelli J., Tumbarello D.A., Schmidt R.P., Turner C.E. Hic-5 promotes invadopodia formation and invasion during TGF-β-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:421–437. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lomenick B., Hao R., Jonai N., Chin R.M., Aghajan M., Warburton S., et al. Target identification using drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21984–21989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910040106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X.L., Zhang S.W., Yamane H., Wahl R., Ali A., Lofgren J.A., et al. Kinetic mechanism of AKT/PKB enzyme family. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13949–13956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitehouse S., Feramisco J.R., Casnellie J.E., Krebs E.G., Walsh D.A. Studies on the kinetic mechanism of the catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:3693–3701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaikuad A., Bullock A.N. Structural basis of intracellular TGF-β signaling: receptors and Smads. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2016;8:a022111. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haslam A., Prasad V. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for and respond to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy drugs. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lau E.Y., Lo J., Cheng B.Y., Ma M.K., Lee J.M., Ng J.K., et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts regulate tumor-initiating cell plasticity in hepatocellular carcinoma through c-Met/FRA1/HEY1 signaling. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1175–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang S., Cao L., Wang Z.R., Li Z., Ma J. Anti-cancer effect of toosendanin and its underlying mechanisms. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2019;21:270–283. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2018.1451516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin Y., Huang Z.L., Li L., Yang Y., Wang C.H., Wang Z.T., et al. Quercetin attenuates toosendanin-induced hepatotoxicity through inducing the Nrf2/GCL/GSH antioxidant signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2019;40:75–85. doi: 10.1038/s41401-018-0024-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu X.Y., Ji C., Tong W., Lian X.P., Wu Y., Fan X.H., et al. Integrated analysis of microRNA and mRNA expression profiles highlights the complex and dynamic behavior of toosendanin-induced liver injury in mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep34225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tewari D., Priya A., Bishayee A., Bishayee A. Targeting transforming growth factor-β signalling for cancer prevention and intervention: recent advances in developing small molecules of natural origin. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12:e795. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vincent T., Neve E.P., Johnson J.R., Kukalev A., Rojo F., Albanell J., et al. A SNAIL1–SMAD3/4 transcriptional repressor complex promotes TGFβ mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:943–950. doi: 10.1038/ncb1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moustakas A., Heldin C.H. Signaling networks guiding epithelial–mesenchymal transitions during embryogenesis and cancer progression. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1512–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peinado H., Olmeda D., Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype?. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo W.W., Liu X., Sun W., Lu J.J., Wang Y.T., Chen X.P. Toosendanin, a natural product, inhibited TGF-β1-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition through ERK/Snail pathway. Phytother Res. 2018;32:2009–2020. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guan X.M. Cancer metastases: challenges and opportunities. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:402–418. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamaguchi H. Pathological roles of invadopodia in cancer invasion and metastasis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:902–907. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gligorijevic B., Bergman A., Condeelis J. Multiparametric classification links tumor microenvironments with tumor cell phenotype. PLoS Biol. 2014;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eckert M.A., Lwin T.M., Chang A.T., Kim J., Danis E., Ohno-Machado L., et al. Twist1-induced invadopodia formation promotes tumor metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:372–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.ten Dijke P., Miyazono K., Heldin C.H. Signaling via hetero–oligomeric complexes of type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi Y.G., Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yi M., Jiao D.C., Qin S., Chu Q., Wu K.M., Li A.P. Synergistic effect of immune checkpoint blockade and anti-angiogenesis in cancer treatment. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:60. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0974-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu Y.Y., Xiong J.Y., Sun X.Y., Gao H.L. Targeted nanomedicines remodeling immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:4327–4347. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yi M., Niu M.K., Zhang J., Li S.Y., Zhu S.L., Yan Y.X., et al. Combine and conquer: manganese synergizing anti-TGFβ/PD-L1 bispecific antibody YM101 to overcome immunotherapy resistance in non-inflamed cancers. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:146. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01155-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yi M., Zhang J., Li A.P., Niu M.K., Yan Y.X., Jiao Y., et al. The construction, expression, and enhanced anti-tumor activity of YM101: a bispecific antibody simultaneously targeting TGFβ and PD-L1. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:27. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01045-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paz-Ares L., Kim T.M., Vicente D., Felip E., Lee D.H., Lee K.H., et al. Bintrafusp alfa, a bifunctional fusion protein targeting TGF-β and PD-L1, in second-line treatment of patients with NSCLC: results from an expansion cohort of a phase 1 trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:1210–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gulley J.L., Schlom J., Barcellos-Hoff M.H., Wang X.J., Seoane J., Audhuy F., et al. Dual inhibition of TGF-β and PD-L1: a novel approach to cancer treatment. Mol Oncol. 2022;16:2117–2134. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Imai K., Takaoka A. Comparing antibody and small-molecule therapies for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:714–727. doi: 10.1038/nrc1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tu K., Yu Y.L., Wang Y., Yang T., Hu Q., Qin X.Y., et al. Combination of chidamide-mediated epigenetic modulation with immunotherapy: boosting tumor immunogenicity and response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13:39003–39017. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c08290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zheng C.L., Xiao Y., Chen C., Zhu J.L., Yang R.J., Yan J.N., et al. Systems pharmacology: a combination strategy for improving efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Briefings Bioinf. 2021;22:bbab130. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.