Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Most patients with schizophrenia are diagnosed in their early twenties and often have commercial insurance at diagnosis. These young adults can experience changes in insurance coverage, that is, “churn,” which can lead to disruptions in care.

OBJECTIVE:

To examine the frequency, speed, and type of insurance churn events in a young adult schizophrenia population with commercial insurance coverage at diagnosis.

METHODS:

The Colorado All-Payer Claims Database, containing insurance claims data from commercial and public insurers for Colorado residents, was used for the study. Eligible patients were required to have at least 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient claims for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, be of age 18-34 years at index, have previous insurance coverage for 12 consecutive months, and have commercial insurance at diagnosis. These patients were 1:5 propensity score matched (PSM) with nonschizophrenia members. Percentages of members on different insurance types were calculated monthly to assess churn events. Cohorts were compared using descriptive statistics, Cox proportional hazards, and generalized estimating equation models.

RESULTS:

The matched schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia cohorts comprised 501 and 2,510 members, respectively. Before PSM, cohorts were imbalanced (schizophrenia cohort had a younger median age and higher proportion of males). After matching, the cohorts were similar in terms of the matched baseline characteristics. Previous mental health disorders were more common in the schizophrenia cohort (75%) than in the nonschizophrenia cohort (26%). The proportion of members with at least 1 churn event for the schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia cohorts, respectively, were 53.8% vs 36.5% after 12 months and 84.6% vs 69.2% after 48 months. Time to first churn event was significantly shorter in the schizophrenia cohort (16 months) than the nonschizophrenia cohort (23 months; P < 0.001). Schizophrenia cohort members had 64.1 and 56.8 churn events per 1,000 members per month vs 43.0 (P ≤ 0.001) and 42.8 (P = 0.011) churn events for nonschizophrenia cohort members in the first and second 6-month periods, respectively. Proportions of members in the schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia cohorts on public insurance, respectively, were 22.9% vs 6.9% after 12 months and 52.4% and 10.7% after 48 months. In the schizophrenia cohort, the most common churn event type was from commercial to public insurance rather than to a different commercial insurance; notably, 41% of members were still on a commercial plan 4 years after diagnosis.

CONCLUSIONS:

Young adults with schizophrenia experienced churn events more rapidly and more frequently than those without schizophrenia for the first 4 years studied after the index date. These disruptions may be associated with reduced access to care and treatment gaps in this vulnerable patient population.

What is already known about this subject

Insurance churn, defined as transitioning between different insurance plans or between insured and uninsured status, can lead to disruptions in physician care, medication adherence, increased emergency department use, and worsening self-reported quality of care and health status in patients.

Diagnosis of schizophrenia typically occurs in young adulthood, and the initial stages of schizophrenia represent a crucial window for increasing the likelihood of achieving symptomatic remission.

Patients with schizophrenia with commercial insurance are likely candidates for insurance churn because of job changes, disability, or aging out of parents’ coverage.

What this study adds

In our study of commercially insured residents of Colorado, patients with schizophrenia were more likely to experience at least 1 churn event (85%) in the 4 years after diagnosis compared with a matched sample of individuals without schizophrenia (69%).

The median time to first churn event was shorter in patients with schizophrenia (16 months) than those without schizophrenia (23 months; P < 0.001), with churn events being particularly common in the first year compared with those without schizophrenia.

The most common insurance churn event type was from commercial to Medicaid rather than to a different commercial insurance. Notably, of all patients with schizophrenia who had commercial insurance at baseline, 41% were still on commercial insurance 4 years after diagnosis.

Schizophrenia is a chronic mental illness characterized by deficiencies in thought processes and perceptions and changes in emotional responsiveness and social interactions.1,2 Diagnosis typically occurs in young adulthood, with some differences by sex (onset in males early twenties; onset in females late twenties).1,2 The initial stages of schizophrenia represent a crucial window for increasing the likelihood of achieving symptomatic remission,3 and health insurance coverage is a critical factor in care continuity and effective management of the disease.

Many individuals, particularly young adults, experience instability in their insurance coverage, transitioning between different insurance plans or between insured and uninsured status, which is referred to as “insurance churning.”4 Insurance churning has been found to be detrimental, as evidenced by disruptions in physician care, medication adherence, increased emergency department use, and worsening self-reported quality of care and health status.4 In Medicaid, coverage disruptions are associated with delays in care characterized by missed preventive care visits, fewer prescription drug refills, and increased use of emergency services.5 Despite the vulnerability of the young adult schizophrenia population and the deleterious effects of insurance churn and subsequent care disruptions, the effect of insurance churn among this group has not been reported in the literature.

A 2002-2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey revealed that 87% of all Americans with schizophrenia were covered by Medicare or Medicaid; 15% were commercially insured; and 7% were uninsured.6 In commercially insured patients, the risk of insurance churn is high when patients switch into or out of employer-sponsored insurance because of job changes or become eligible for public insurance because of low income or disability.7,8 Other transitions include switching between sources of subsidized coverage because of changes in eligibility (eg, switching from commercial to Medicaid and vice versa); loss of coverage because of changes in eligibility (eg, switching from Medicaid to uninsured); switching between plans within the same coverage type, either voluntarily (if a better plan becomes available) or involuntarily (if an insurer exited a marketplace plan); and switching because of administrative disruptions in coverage (eg, difficulty with Medicaid renewal).7,8

In addition, for Medicaid-covered individuals, insurance churn can occur because of contacts with the criminal justice system, where patients may experience either a suspension or termination of coverage.9,10 The 2014 Affordable Care Act (ACA) allows adult children to remain on parents’ commercial insurance plan until age 26.11 A recent study found that this expansion of dependent coverage was associated with an increase in private insurance among young adults with early psychoses.12 Although this suggests that there may be an overall decrease in insurance churning since the ACA, there is still evidence of the negative consequences when it does occur.4,7,8

This study explored the occurrence of insurance churn among young adults aged 18-34 years at diagnosis with schizophrenia who resided in Colorado with commercial insurance coverage at the time of diagnosis. The objectives were to compare a young adult schizophrenia cohort with a matched nonschizophrenia cohort on (1) types of insurance coverage over the follow-up period, (2) the proportion of patients who experienced at least 1 churn event by various time points, (3) the time from index date until the first churn event, and (4) the rate of churn events over different periods in the follow-up.

We hypothesized that young adults with schizophrenia are more likely to undergo insurance churn (particularly from commercial to public insurance) and at a faster rate compared with a matched cohort of young adults without schizophrenia. Results of this analysis should provide key data that influence policies to reduce the frequency of insurance churn and mitigate its negative impacts.

Methods

DATA SOURCE

The Colorado All-Payer Claims Database (CO APCD) captures health insurance claims data for more than 4.3 million unique Colorado residents, representing the majority (76%) of insured beneficiaries living in the state.13,14 The CO APCD contains deidentified claims from commercial insurers operating within the state, as well as Medicare and Medicaid and allows for the ability to follow members longitudinally as members change insurance coverage. Claims are not included from members who become incarcerated or who have TRICARE, Veterans Administration health care, tribal health care, federal employee health benefits, are self-insured payers who do not report their claims (approximately 75%14), or are those who leave the state.15

The data for this study comprised 2 member groups: (1) any member with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder aged between 18-34 years during the study period January 1, 2012-December 31, 2019 (schizophrenia data group), and (2) a 25% random sample of residents aged 18-34 years without a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder at any time over the study period (nonschizophrenia data group; Supplementary Figure 1 (1MB, pdf) , available in online article). The HIPAA and HITECH compliant deidentified data request was reviewed by the Data Release Review Committee and met all requirements for security and privacy.

INCLUSION CRITERIA

Schizophrenia Cohort.

A schizophrenia cohort was created from the schizophrenia data group if it met the following 4 conditions: (1) at least 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient (on separate days) claims for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code 295.xx; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification code F20.xx and F25.xx;); (2) aged 18-34 years on the index date; (3) continuous medical insurance coverage of any type for at least 12 months before the index date (defined as the date of the earliest schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder diagnosis code); and (4) commercial medical insurance coverage on the index date (Supplementary Figure 1 (1MB, pdf) ).

Commercial insurance coverage included any of the following plan types: commercial, health maintenance organization (HMO), indemnity insurance, point of service (POS), preferred provider organization (PPO), or self-funded. Because it was possible for members to have more than 1 type of insurance coverage in the same month, members with both commercial and public insurance were considered commercially insured, since commercial insurance is typically the primary payer.

Nonschizophrenia Cohort.

A nonschizophrenia cohort was created from the nonschizophrenia data group if all conditions applied to the schizophrenia cohort apart from claims for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. For nonschizophrenia cohort members, the index date was randomly assigned based on the distribution of index dates observed in the schizophrenia cohort.

Complete inclusion criteria for both cohorts are described in Supplementary Figure 1 (1MB, pdf) .

COHORT MATCHING

In order to minimize bias between the 2 cohorts for comparative analyses, schizophrenia cohort members were matched on several factors with nonschizophrenia cohort members using propensity score methodology (see Statistical Analysis section).16

FOLLOW-UP PERIOD

Members in both cohorts were followed for 48 months or until members had no more enrollment records or the end of the study period, whichever occurred first. In each month of follow-up, the types of insurance that members were covered by were contained in the data (eg, commercial, HMO, PPO, Medicare, and Medicaid). Members could have more than 1 type of insurance coverage in a month.

In addition, members could not have any insurance coverage in some months (eg, not residing in the state, incarceration, no insurance coverage, self-insured employer coverage); in such cases, these gap months were recorded as “uninsured/unknown” if the gap was followed by a period with insurance coverage. If there was no further insurance coverage, the last month of the member’s coverage was considered the end of the follow-up period.

CHURN EVENT

A churn event was defined as a change in type of insurance coverage from one month to the subsequent month. These changes included changes from commercial insurance to public insurance or from one type of commercial insurance to another type (eg, HMO to PPO, but not HMO to a different HMO, since such changes were not recorded in the data). Cases in which a transition month occurred, where the previous and subsequent types of insurance coverage overlapped for 1 month, were considered a single churn event, rather than 2 events (eg, HMO to HMO + Medicaid to Medicaid). Members churning into uninsured/unknown status and then churning back into an insured status were considered to have had 2 churn events (Supplementary Figure 2 (1MB, pdf) , available in online article).

OUTCOMES

The primary outcomes of this study were the comparison between the schizophrenia and matched nonschizophrenia cohorts on (1) types of insurance coverage over the follow-up period, (2) the proportion of patients who experienced at least 1 churn event by various time points, (3) the time from index date until the first churn event, and (4) the rate of churn events over different periods in the follow-up period.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Propensity score matching.

The matching factors used to create the propensity score included age at index date, year of index date, sex, number of insurance churn events in the year before diagnosis, baseline (over the 1 year before index), health statistics region (21 health statistics regions were developed by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment based on county population size, demographic factors, and the number of communities served by each county health department),17 Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, and the number of inpatient hospital admissions not related to mental health in the year before the index date (Supplementary Table 1 (1MB, pdf) , available in online article).

No mental health-related comorbidities were included in the matching process to allow the matched nonschizophrenia cohort to be representative of the nonschizophrenia population in the state. Schizophrenia cohort members were matched to nonschizophrenia cohort members at an overall 1:5 ratio without replacement, using an established SAS macro.18 The propensity of belonging to the schizophrenia cohort was modeled using logistic regression based on the previously mentioned factors. Given the large pool from which to choose controls, a “greedy” variable-ratio matching algorithm was used. Propensity scores were matched on 8 digits initially, then, if no match was found, the match criteria was sequentially reduced by 1 digit until a match was found.

Descriptive and Inferential Statistics.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia cohorts before and after matching. Differences between groups were analyzed using chi-square tests for categorical data and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous data. Aside from the descriptive statistics of baseline characteristics, all churn-related analyses were performed on the matched cohorts. Cox proportional hazards regression was conducted to examine the time to first churn event, controlling for the covariates of age at index, previous number of insurance churn events, number of previous mental health medications, number of nonmental health admissions, insurance type at index date, CCI score, and whether receiving insurance from an ACA health insurance exchange.

In addition, a longitudinal Poisson regression analysis using generalized estimating equations (GEE) clustered at the patient level was used to estimate the churn event rate (churn events per 1,000 members per month) for each 6-month period up to 48 months (ie, churn event rate from index date to month 6, month 7 to month 12, and so on). The same covariates were controlled for in the GEE model as in the Cox model. Robust standard errors were used.

Results

COHORT SELECTION

Of the 16,374 young adults in the schizophrenia data group and 1,180,817 young adults in the nonschizophrenia data group, 516 and 133,164 members met the inclusion criteria for the schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia cohorts, respectively. Following propensity score matching, the final analytical cohort comprised 501 members in the schizophrenia cohort and 2,510 in the matched nonschizophrenia cohort (Supplementary Figure 1 (1MB, pdf) ). Five additional controls were selected by the greedy algorithm due to variable ratio matching.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS BEFORE PROPENSITY SCORE MATCHING

Baseline demographic, clinical, and previous churn event characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There was a higher proportion of males in the schizophrenia cohort (67.2%) compared with the nonschizophrenia cohort (47.9%; P < 0.001) with a younger median age of 23 years in the schizophrenia cohort compared with 27 years in the nonschizophrenia cohort (P < 0.001). HMO and Medicaid coverage at index was more common in the schizophrenia cohort than the nonschizophrenia cohort, covering 17% and 3.1%, respectively (P < 0.001). Schizophrenia cohort members were also more likely to have their insurance relation as a child (39.7%) compared with the nonschizophrenia cohort (27.1%; P < 0.001) and also more likely to have had at least 1 month of Medicaid (29.8% vs 8.5%; P < 0.001) coverage in the year before their index dates.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographics and Characteristics

| Before Propensity Score Matching | After Propensity Score Matching | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | SCZ cohort | Non-SCZ cohort | P valuea | Overall | Matched SCZ cohort | Matched non-SCZ cohort | P valuea | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Total | 133,680 | 100.0 | 516 | 0.4 | 133,164 | 99.6 | – | 3,011 | 100.0 | 501 | 16.6 | 2,510 | 83.4 | – |

| Sexb | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 64,126 | 48.0 | 347 | 67.2 | 63,779 | 47.9 | < 0.001 | 2,007 | 66.7 | 337 | 67.3 | 1,670 | 66.5 | 0.751 |

| Female | 69,554 | 52.0 | 169 | 32.8 | 69,385 | 52.1 | 1,004 | 33.3 | 164 | 32.7 | 840 | 33.5 | ||

| Year of indexb | ||||||||||||||

| 2013 | 22,838 | 17.1 | 99 | 19.2 | 22,739 | 17.1 | 0.715 | 534 | 17.7 | 95 | 19.0 | 439 | 17.5 | 0.761 |

| 2014 | 16,085 | 12.0 | 64 | 12.4 | 16,021 | 12.0 | 357 | 11.9 | 62 | 12.4 | 295 | 11.8 | ||

| 2015 | 20,918 | 15.6 | 86 | 16.7 | 20,832 | 15.6 | 479 | 15.9 | 81 | 16.2 | 398 | 15.9 | ||

| 2016 | 21,283 | 15.9 | 77 | 14.9 | 21,206 | 15.9 | 476 | 15.8 | 76 | 15.2 | 400 | 15.9 | ||

| 2017 | 19,286 | 14.4 | 64 | 12.4 | 19,222 | 14.4 | 450 | 14.9 | 63 | 12.6 | 387 | 15.4 | ||

| 2018 | 19,268 | 14.4 | 75 | 14.5 | 19,193 | 14.4 | 426 | 14.1 | 73 | 14.6 | 353 | 14.1 | ||

| 2019 | 14,002 | 10.5 | 51 | 9.9 | 13,951 | 10.5 | 289 | 9.6 | 51 | 10.2 | 238 | 9.5 | ||

| Age at index, yearsb | ||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.58 | (4.86) | 24.09 | (4.52) | 26.59 | (4.86) | < 0.001 | 24.19 | (4.47) | 24.09 | (4.54) | 24.20 | (4.46) | 0.442 |

| Median (IQR) | 27.00 | (9.00) | 23.00 | (7.00) | 27.00 | (9.00) | 23.00 | (7.00) | 23.00 | (7.00) | 23.00 | (7.00) | ||

| 18-21 | 26,846 | 20.1 | 170 | 32.9 | 26,676 | 20.0 | < 0.001 | 993 | 33.0 | 165 | 32.9 | 828 | 33.0 | 0.983 |

| 22-25 | 30,750 | 23.0 | 182 | 35.3 | 30,568 | 23.0 | 1,088 | 36.1 | 178 | 35.5 | 910 | 36.3 | ||

| 26-29 | 30,155 | 22.6 | 79 | 15.3 | 30,076 | 22.6 | 446 | 14.8 | 75 | 15.0 | 371 | 14.8 | ||

| 30-34 | 45,929 | 34.4 | 85 | 16.5 | 45,844 | 34.4 | 484 | 16.1 | 83 | 16.6 | 401 | 16.0 | ||

| Health statistics region at indexb | ||||||||||||||

| Logan, Morgan, Phillips, Sedgwick, Washington, and Yuma counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | 0.023 | c | c | c | c | c | c | 0.989 |

| Larimer County | 6,676 | 5.0 | 25 | 4.8 | 6,651 | 5.0 | 148 | 4.9 | 25 | 5.0 | 123 | 4.9 | ||

| Douglas County | 8,842 | 6.6 | 39 | 7.6 | 8,803 | 6.6 | 247 | 8.2 | 39 | 7.8 | 208 | 8.3 | ||

| El Paso County | 10,856 | 8.1 | 51 | 9.9 | 10,805 | 8.1 | 284 | 9.4 | 50 | 10.0 | 234 | 9.3 | ||

| Cheyenne, Elbert,Kit Carson, and Lincoln counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Baca, Bent, Crowley, Huerfano, Kiowa, Las Animas, Otero, and Prowers counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Pueblo County | 3,052 | 2.3 | 14 | 2.7 | 3,038 | 2.3 | 79 | 2.6 | 14 | 2.8 | 65 | 2.6 | ||

| Alamosa, Conejos, Costilla, Mineral, Rio Grande, and Saguache counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Archuleta, Dolores,La Plata, Montezuma, and San Juan counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Delta, Gunnison, Hinsdale, Montrose, Ouray, and San Miguel counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Jackson, Moffat,Rio Blanco, and Routt counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Eagle, Garfield, Grand, Pitkin, and Summit counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Chaffee, Custer, Fremont, and Lake counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Adams County | 12,450 | 9.3 | 55 | 10.7 | 12,395 | 9.3 | 351 | 11.7 | 55 | 11.0 | 296 | 11.8 | ||

| Arapahoe County | 17,237 | 12.9 | 91 | 17.6 | 17,146 | 12.9 | 524 | 17.4 | 88 | 17.6 | 436 | 17.4 | ||

| Boulder and Broomfield counties | 9,843 | 7.4 | 29 | 5.6 | 9,814 | 7.4 | 171 | 5.7 | 28 | 5.6 | 143 | 5.7 | ||

| Clear Creek, Gilpin, Park, and Teller counties | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Weld County | 6,782 | 5.1 | 26 | 5.0 | 6,756 | 5.1 | 148 | 4.9 | 25 | 5.0 | 123 | 4.9 | ||

| Mesa County | 2,924 | 2.2 | 5 | 1.0 | 2,919 | 2.2 | 21 | 0.7 | 5 | 1.0 | 16 | 0.6 | ||

| Denver County | 20,638 | 15.4 | 87 | 16.9 | 20,551 | 15.4 | 490 | 16.3 | 85 | 17.0 | 405 | 16.1 | ||

| Jefferson County | 19,696 | 14.7 | 64 | 12.4 | 19,632 | 14.7 | 406 | 13.5 | 64 | 12.8 | 342 | 13.6 | ||

| Missing | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | c | ||

| Insurance at index | ||||||||||||||

| HMO | 55,711 | 41.7 | 175 | 33.9 | 55,536 | 41.7 | < 0.001 | 1,172 | 38.9 | 173 | 34.5 | 999 | 39.8 | < 0.001 |

| PPO | 29,386 | 22.0 | 82 | 15.9 | 29,304 | 22.0 | 649 | 21.6 | 81 | 16.2 | 568 | 22.6 | ||

| POS | 18,935 | 14.2 | 46 | 8.9 | 18,889 | 14.2 | 380 | 12.6 | 45 | 9.0 | 335 | 13.3 | ||

| Self-funded | 13,200 | 9.9 | 29 | 5.6 | 13,171 | 9.9 | 246 | 8.2 | 29 | 5.8 | 217 | 8.6 | ||

| HMO + Medicaid | 4,171 | 3.1 | 86 | 16.7 | 4,085 | 3.1 | 212 | 7.0 | 85 | 17.0 | 127 | 5.1 | ||

| Other | 12,277 | 9.2 | 98 | 19.0 | 12,179 | 9.1 | 352 | 11.7 | 88 | 17.6 | 264 | 10.5 | ||

| Health exchange member at index | ||||||||||||||

| No | 126,770 | 94.8 | 483 | 93.6 | 126,287 | 94.8 | 0.207 | 2,801 | 93.0 | 473 | 94.4 | 2,328 | 92.7 | 0.182 |

| Yes | 6,910 | 5.2 | 33 | 6.4 | 6,877 | 5.2 | 210 | 7.0 | 28 | 5.6 | 182 | 7.3 | ||

| Insurance relation at index | ||||||||||||||

| Child | 36,268 | 27.1 | 205 | 39.7 | 36,063 | 27.1 | < 0.001 | 1,243 | 41.8 | 202 | 40.3 | 1,041 | 41.5 | 0.109 |

| Employee | 79,168 | 59.2 | 272 | 52.7 | 78,896 | 59.2 | 1,466 | 7.5 | 260 | 51.9 | 1,206 | 48.1 | ||

| Dependent/spouse/unknown | 18,244 | 13.6 | 39 | 7.6 | 18,205 | 13.7 | 302 | 50.7 | 39 | 7.8 | 263 | 10.5 | ||

| At least 1 month Medicaid in previous 12 months | ||||||||||||||

| No | 122,168 | 91.4 | 362 | 70.2 | 121,806 | 91.5 | < 0.001 | 2,509 | 83.3 | 348 | 69.5 | 2,161 | 86.1 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 11,512 | 8.6 | 154 | 29.8 | 11,358 | 8.5 | 502 | 16.7 | 153 | 30.5 | 349 | 13.9 | ||

| Previous inpatient nonmental health admitsb | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 122,602 | 91.7 | 411 | 79.7 | 122,191 | 91.8 | <0.001 | 2,416 | 80.2 | 401 | 80.0 | 2,015 | 80.3 | 0.907 |

| 1 | 9,233 | 6.9 | 74 | 14.3 | 9,159 | 6.9 | 427 | 14.2 | 70 | 14.0 | 357 | 14.2 | ||

| 2 | 1,185 | 0.9 | 16 | 3.1 | 1,169 | 0.9 | 76 | 2.5 | 15 | 3.0 | 61 | 2.4 | ||

| 3+ | 660 | 0.5 | 15 | 2.9 | 645 | 0.5 | 92 | 3.1 | 15 | 3.0 | 77 | 3.1 | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Indexb | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 126,789 | 94.8 | 459 | 89.0 | 126,330 | 94.9 | < 0.001 | 2,705 | 89.8 | 445 | 88.8 | 2,260 | 90.0 | 0.579 |

| 1 | 5,501 | 4.1 | 42 | 8.1 | 5,459 | 4.1 | 239 | 7.9 | 42 | 8.4 | 197 | 7.8 | ||

| 2+ | 1,390 | 1.0 | 15 | 2.9 | 1,375 | 1.0 | 67 | 2.2 | 14 | 2.8 | 53 | 2.1 | ||

| At least 1 mental health medication | ||||||||||||||

| At least 1 mental health medication | 20,057 | 15.0 | 315 | 61.0% | 19,742 | 14.8 | < 0.001 | 720 | 23.9 | 308 | 61.5 | 412 | 16.4 | < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.27 | (0.84) | 2.79 | (3.40) | 0.26 | (0.80) | < 0.001 | 0.74 | (1.90) | 2.81 | (3.41) | 0.33 | (1.00) | < 0.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 2.00 | (4.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 2.00 | (4.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | ||

| Previous number of churnsb | ||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.24 | (0.56) | 0.37 | (0.65) | 0.24 | (0.56) | < 0.001 | 0.40 | (0.68) | 0.38 | (0.66) | 0.40 | (0.69) | 0.633 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (1.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (1.00) | 0.00 | (1.00) | 0.00 | (1.00) | ||

| 0 | 109,128 | 81.6 | 362 | 70.2 | 108,766 | 81.7 | < 0.001 | 2,071 | 68.8 | 350 | 69.9 | 1,721 | 68.6 | 0.844 |

| 1 | 18,260 | 13.7 | 124 | 24.0 | 18,136 | 13.6 | 750 | 24.9 | 121 | 24.2 | 629 | 25.1 | ||

| 2+ | 6,292 | 4.7 | 30 | 5.8 | 6,262 | 4.7 | 190 | 6.3 | 30 | 6.0 | 160 | 6.4 | ||

a Kruskal-Wallis or chi-square tests as appropriate.

b Covariates used in the propensity score matching.

c Items suppressed as per CO APCD publication guidelines.

CO APCD = Colorado All-Payer Claims Database; HMO = health maintenance organization; IQR = interquartile range; POS = point of service; PPO = preferred provider; SCZ = schizophrenia.

Occurrence of at least 1 churn event in the year before the index date was more common in the schizophrenia cohort (29.8%) compared with the nonschizophrenia cohort (18.3%, P < 0.001). Members of the schizophrenia cohort were more likely to have had at least 1 inpatient admission in the year before the index date (20.3% vs 8.3%, P < 0.001). CCI scores were higher in the schizophrenia cohort than the nonschizophrenia cohort with 11.0% and 5.1% having a CCI of 1 or greater (P < 0.001). Members of the schizophrenia cohort were more likely to have taken at least 1 mental health medication in the year before the index date than the nonschizophrenia cohort (61.0% vs 14.8%, P < 0.001) and more likely to have at least 1 mental health comorbidity (74.6% vs 29.4%, P < 0.001; Supplementary Figure 3A (1MB, pdf) , available in online article). The most common mental health comorbidities in the schizophrenia cohort (vs the nonschizophrenia cohort) were other psychotic disorders (39.1% vs 0.7%, P < 0.001), substance-related and addictive disorders (34.1% vs 9.0%, P < 0.001), and depressive disorders (33.8% vs 10.5%, P < 0.001).

The schizophrenia cohort also had greater occurrence of nonmental health comorbidities compared with the nonschizophrenia cohort, such as chronic pulmonary disease (9.4% vs 5.1%, P < 0.001), other neurological disorders (8.2% vs 1.9%, P < 0.001), fluid and electrolyte disorders (5.0% vs 1.3%, P < 0.001), and hypertension (4.0% vs 1.5%, P < 0.001).

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS FOLLOWING PROPENSITY SCORE MATCHING

After propensity score matching, none of the differences previously described remained in the variables used in the propensity score model between the schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia cohorts (Table 1). For variables not used in the propensity score model, the cohorts differed significantly in the type of commercial insurance and the proportion of members with mental health comorbidities (Supplementary Figure 3B (1MB, pdf) , available in online article). At least 1 previous mental health condition occurred in 74.9% of the schizophrenia cohort compared with 26.2% in the nonschizophrenia cohort (P < 0.001). In the schizophrenia cohort, the most common mental health conditions were other psychotic disorders (43.9%), depressive disorders (38.7%), anxiety disorders (36.5%), substance-related and addictive disorders (31.5%), bipolar and related disorders (25.5%), and trauma and stressor-related disorders (20.2%). In the nonschizophrenia cohort, the proportion of members reporting a mental health condition was significantly lower than in the schizophrenia cohort, with the most common being anxiety disorders (10.7%), depressive disorders (9.2%), and substance-related and addictive disorders (6.5%).

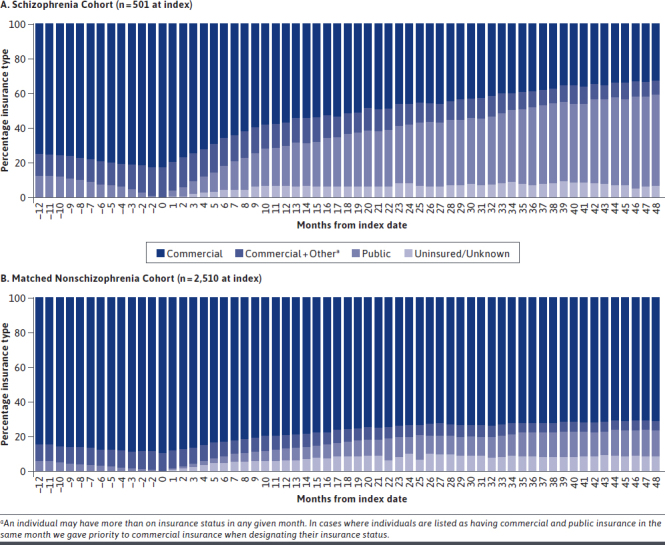

TYPE OF INSURANCE COVERAGE AFTER INDEX DATE

At 12 months after the index date, 22.9% of the schizophrenia cohort were publicly insured vs 6.9% of the nonschizophrenia cohort (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2 (1MB, pdf) ). By 24 months, the percentage of young adults with schizophrenia who were publicly insured rose to 33.8% vs 6.4% of the nonschizophrenia cohort, and at month 48, 52.4% vs 10.7% were publicly insured. Notably, 40.7% of the schizophrenia cohort were still on commercial insurance 48 months after diagnosis. The proportion of members who were uninsured/unknown at 12 months was 6.6% for the schizophrenia cohort vs 6.1% for the nonschizophrenia cohort. By 24 and 48 months, the proportion of members who were uninsured/unknown were 7.8% vs 10.0% and 6.6% vs 8.5% for the schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia cohorts, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Insurance Status by Month From 12 Months Before Index to 48 Months After Index: (A) Schizophrenia Cohort and (B) Matched Nonschizophrenia Cohort (N = 3,011)

PROPORTION OF PATIENTS WITH A CHURN EVENT

There was a higher proportion of members with at least 1 churn event in the schizophrenia cohort than the nonschizophrenia cohort, starting at 53.8% vs 36.5% in the first 12 months from the index date, increasing in both cohorts to 68.8% vs 54.7% by 24 months, 79.8% vs 64.5% by 36 months, and 84.6% vs 69.2% by 48 months (Supplementary Figure 4 (1MB, pdf) and Supplementary Table 3 (1MB, pdf) , available in online article).

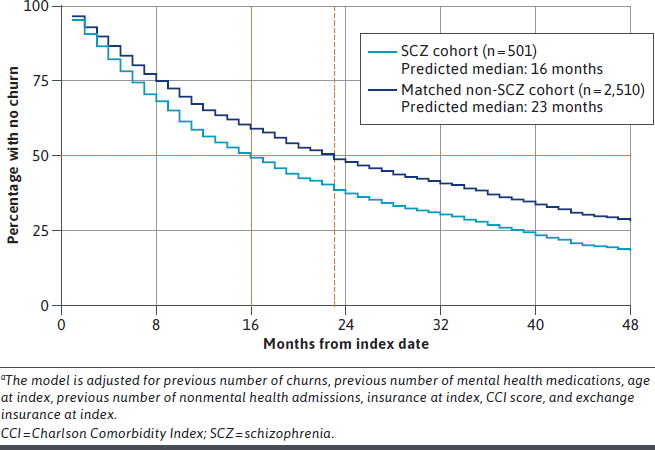

TIME TO FIRST CHURN EVENT AND CHURN EVENT RATE

The Cox regression adjusted median time to first churn event was significantly shorter in the schizophrenia cohort (16 months) than the nonschizophrenia cohort (23 months; P < 0.001; Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4 (1MB, pdf) , available in online article).

FIGURE 2.

Cox Proportional Hazards Regression: Adjusted Time to First Churna (N = 3011)

Members of the schizophrenia cohort had significantly higher unadjusted and adjusted rates of churn events per 1,000 members per month (P1KMPM) in the first and second 6-month periods compared with members in the matched nonschizophrenia cohort (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 5 (1MB, pdf) , available in online article). Members in the schizophrenia cohort had adjusted rates of 64.1 and 56.8 churn events P1KMPM vs 43.0 (P ≤ 0.001) and 42.8 (P = 0.011) churn events P1KMPM for nonschizophrenia cohort members in the first and second 6-month periods, respectively. Rates of churn plateaued in the later months, with 33-43 churn events P1KMPM for the schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia cohorts. There were no significant differences between the cohorts in the later 6-month periods (Supplementary Table 5 (1MB, pdf) ).

FIGURE 3.

Average Number of Churns per 1,000 Patients per 6-Month Perioda,b

Discussion

This analysis found that young adults with schizophrenia and commercial insurance coverage at the time of diagnosis experience insurance churn more frequently and more rapidly compared with a matched cohort without schizophrenia.

Study results show that, among young adults, a schizophrenia diagnosis is associated with unstable insurance coverage. These patients are most likely experiencing first-episode schizophrenia, which is a critical period for medical and nonmedical interventions that can address symptoms and reduce the duration of untreated psychosis.3 Disruptions in health insurance coverage, including changes in payer type and health plan, may lead to gaps in care and poor clinical and functional outcomes.4,5

Nearly a quarter of the schizophrenia cohort had transitioned to public insurance within the first 12 months of diagnosis, and approximately half had at least 1 churn event. Churn events were also high in the first and second 6-month periods after diagnosis, with rates approximately 33% and 49% higher, respectively, in the schizophrenia cohort than the nonschizophrenia cohort. The high rate of churn events so close to diagnosis is important because previous research has shown that the first year after diagnosis has higher resource utilization and cost than later years, largely driven by high hospitalization and emergency department admissions in early months.19,20 It is in the first few months after diagnosis when patients are likely to receive their first medications and therapy.19 Given this, the high frequency and rate of churn events observed in the 12 months after diagnosis is of particular concern.

Although the 12 months after diagnosis is a critical time period in the early course of the disease, schizophrenia is a chronic condition requiring long-term treatment.21 For this reason, the finding that churn events continue up to 48 months after diagnosis is significant. The effect of insurance churn for patients with schizophrenia may result in gaps and disruptions in coverage and access to health care, potentially leading to treatment interruptions, relapse, additional health care burden, emotional distress, and income instability.22 More specifically, changes in health insurance coverage may be accompanied by disruptions in medication treatment resulting in nonadherence, which is a key driver of relapse.23

Return to active psychosis reflects a period of disease progression that may not allow patients to return to their previous level of function and put them at risk of treatment refractoriness.24-26 In addition, relapse is associated with progressive functional deterioration, worsening clinical outcomes, escalating caregiver burden, and an increased economic burden for families and society. Further, changes in medication, such as switching from dual therapy to monotherapy due to policy differences between insurance providers can cause an increase in symptoms and treatment discontinuations.27

Although the rates of churn 12 months after diagnosis were similar between the 2 cohorts, the proportion of patients on commercial insurance continued to drop through the end of the study period. However, over 40% of patients with schizophrenia remained on commercial insurance, highlighting that the long-term insurance burden after diagnosis is shared between public and commercial insurance. Although the overall prevalence of schizophrenia is relatively low among commercial insurers in the United States, commercial payers should be concerned about the cost of this population.19 In a 2011 study analyzing a commercially insured population using the IBM MarketScan database, the reported average total claim cost per patient with schizophrenia was more than 4 times the average total claim cost for a demographically adjusted population without schizophrenia.19 For newly diagnosed patients, costs were highest in the month of diagnosis.19

Almost half (46%) of the members of the schizophrenia cohort in this study had dependent status, suggesting that the ACA requirement for commercial insurers to cover dependents until the age of 26 may be increasing the number of young adults with schizophrenia covered by commercial insurance. This corresponds to a study using the National Inpatient Sample and Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, which found a 20% relative increase of private insurance paying for psychosis-related hospitalization stays for patients aged 20-26 years compared with patients aged 27-29 years.12

Of the members in the schizophrenia cohort who were employed at the start of the study (52%), it is likely that loss or change of employment was a factor in the higher occurrence of churn events in this population, which aligns with the low employment rates of patients with schizophrenia reported in Western society (4%-13%).28 The combination of changing or losing employment and the increased disease burden associated with a schizophrenia diagnosis makes a case for these patients to have continued, uninterrupted insurance to ensure sufficient access to care.

The results of this study support the importance of stronger policies for commercial insurers to minimize churn events and protect patients with schizophrenia who experience churn events. Both aspects will help ensure that these patients get the treatment continuity needed, particularly in the first 12 months after diagnosis—a time most crucial to patient outcomes.19 One option for minimizing churn events is the widespread adoption of multimarket health plans in which the same insurer participates in the private insurance and manages state Medicaid plans so that the patient and network are constant even if the payer changes.29

Policies to reduce the effect of insurance churn events could include ensuring consistency of access to medications and health care professionals. This is the goal of a New York State policy that requires existing providers to cover treatment for 60 days after a member changes plans that may not include that provider during and after switching from commercial to public insurance.30 In addition, commercial payers have a role to play in ensuring that young, recently diagnosed adults with schizophrenia receive the care needed without barriers in the critical period after diagnosis. The benefit to the patient and society is immeasurable, given that most of these young adults with schizophrenia will eventually be covered under public insurance.

LIMITATIONS

This study has some limitations to consider. The CO APCD does not specify a plan ID, only a provider type. This limited our ability to identify certain switches, which could have the effect of both under- and overestimating the number of churn events. For instance, an HMO-to-HMO switch between different payers would not be captured as a churn event, which could lead to an underestimation of events. Conversely, a change in type of insurance within the same payer was counted as a churn event, although such an event may be less disruptive.

In using the CO APCD, it was not possible to determine if members without claims were uninsured, incarcerated, moved out of state, were part of a self-insured employer plan that did not voluntarily share their claims, or were covered by insurance not captured in the dataset (eg, TRICARE, Veterans Affairs plans, or tribal programs). Such residents may not even be represented in the data, while members moving to one of these scenarios would be classified as “uninsured/unknown” in our analysis, which would have affected the generalizability of our results. Since the study was limited to the Colorado population, results should be interpreted with caution when extrapolating.

We assumed that the differences in number and rates of churn events between cohorts were driven by the presence or absence of schizophrenia, but additional factors not available in the database, and thus not included in the matching process, may be confounders, such as employment status, including salary, marital status, may be confounders.

Finally, this study did not examine the effect that insurance churn may have had on patients with schizophrenia (eg, if churn events caused changes in medication prescriptions and/or medical resource utilization).

Conclusions

Young adults with schizophrenia encounter more frequent and more rapid changes in insurance coverage during the first 4 years following diagnosis. The disruption resulting from churning from commercial to public insurance, as well as periods of being uninsured/unknown, may lead to reduced access to care and possible treatment gaps for this vulnerable patient population. Further research is warranted to evaluate the effect of these changes in insurance on patient care and clinical and societal outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support for the development of this manuscript was provided by Chris Whittaker, PhD, of Zoetic Science, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. 2018. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia.shtml

- 2.National Alliance on Mental Illness. Schizophrenia. 2021. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Mental-Health-Conditions/Schizophrenia/Overview

- 3.Schennach R, Riedel M, Musil R, Möller HJ. Treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2012;10(2): 78-87. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2012.10.2.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommers BD, Gourevitch R, Maylone B, Blendon RJ, Epstein AM. Insurance churning rates for low-income adults under health reform: lower than expected but still harmful for many. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(10):1816-24. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee R, Ziegenfuss JY, Shah ND. Impact of discontinuity in health insurance on resource utilization. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:195. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khaykin E, Eaton WW, Ford DE, Anthony CB, Daumit GL. Health insurance coverage among persons with schizophrenia in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(8):830-34. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.8.830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommers BD, Rosenbaum S. Issues in health reform: how changes in eligibility may move millions back and forth between Medicaid and insurance exchanges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(2):228-36. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sommers BD, Graves JA, Swartz K, Rosenbaum S. Medicaid and marketplace eligibility changes will occur often in all states; policy options can ease impact. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):700-07. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pew Charitable Trusts. How and when Medicaid covers people under correctional supervision. Issue Brief. August 2, 2016. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2016/08/how-and-when-medicaid-covers-people-under-correctional-supervision

- 10.Kaiser Family Foundation. States reporting corrections-related Medicaid enrollment policies in place for prisons or jails. 2019. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/states-reporting-corrections-related-medicaid-enrollment-policies-in-place-for-prisons-or-jails

- 11.Healthcare.gov. How to get or stay on a parent’s plan. 2021. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.healthcare.gov/young-adults/children-under-26/

- 12.Busch SH, Golberstein E, Goldman HH, Loveridge C, Drake RE, Meara E. Effects of ACA expansion of dependent coverage on hospital-based care of young adults with early psychosis. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(11):1027-33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Center for Improving Value in Health Care. Percent covered lives/population in the CO APCD by county. 2020. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.civhc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/CO-APCD-Percent-Covered-Lives-by-Payer-and-CO-County.xlsx

- 14.Center for Improving Value in Health Care. What’s in the CO APCD? 2020. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.civhc.org/get-data/whats-in-the-co-apcd/

- 15.Center for Improving Value in Health Care. Capabilities of the Colorado All Payer Claims Database. 2017. Accessed February 23, 2021. http://www.civhc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/CO-APCD-Capabilities_Oct-2017_Final.pdf

- 16.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41-55. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colorado Health Institute. Colorado health access survey methodology report. 2015. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.shadac.org/sites/default/files/CO_2015_HH_Methodology.pdf

- 18.Parsons LS. Performing a 1:n case-control match on propensity score. SAS Conference Proceedings: SAS Users Group International. 2004. Accessed June 1, 2021. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings/proceedings/sugi29/165-29.pdf

- 19.Fitch K, Iwasaki K, Villa KF. Resource utilization and cost in a commercially insured population with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7(1):18-26. Accessed June 1, 2021. https://www.ahdbonline.com/issues/2014/january-february-2014-vol-7-no-1/1640-resource-utilization-and-cost-in-a-commercially-insured-population-with-schizophrenia [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholl D, Akhras KS, Diels J, Schadrack J. Burden of schizophrenia in recently diagnosed patients: healthcare utilisation and cost perspective. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(4):943-55. doi: 10.1185/03007991003658956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayo Clinic. Schizophrenia. 2020. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/schizophrenia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354443

- 22.Brugnoli-Ensin I, Mulligan J. Instability in insurance coverage: the impacts of churn in Rhode Island, 2014-2017. R I Med J. 2018;101(8):46-49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Priede A, Hetrick SE, et al. Risk factors for relapse following treatment for first episode psychosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis of longitudinal studies. Schizophr Res. 2012;139(1-3):116-28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kane JM. Treatment strategies to prevent relapse and encourage remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 1):27-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Koreen A, et al. Psychobiologic correlates of treatment response in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14 (3 Suppl):13s-21s. doi: 10.1016/0893-133x(95)00200-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyatt RJ. Research in schizophrenia and the discontinuation of antipsychotic medications. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(1):3-9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Constantine RJ, Andel R, McPherson M, Tandon R. The risks and benefits of switching patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder from two to one antipsychotic medication: a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2015;166(1-3):194-200. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evensen S, Wisløff T, Lystad JU, Bull H, Ueland T, Falkum E. Prevalence, employment rate, and cost of schizophrenia in a high-income welfare society: a population-based study using comprehensive health and welfare registers. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(2):476-83. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardwell A. Revisiting churn: an early understanding of state-level health coverage transitions under the ACA. August 2016. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Churn-Brief.pdf

- 30.New York State Department of Financial Services. Consumer rights and responsibilities. 2021. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.dfs.ny.gov/consumers/health_insurance/your_rights_as_a_health_insurance_consumer