Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Final results for the primary endpoint of the COVID-19 Monoclonal antibody Efficacy Trial-Intent to Care Early (COMET-ICE) randomized controlled trial (NCT04545060) showed a 79% (P < 0.001) adjusted relative risk reduction in longer-than-24-hour hospitalization or death due to any cause in high-risk patients with COVID-19 receiving sotrovimab compared with placebo at Day 29. Given the substantial costs associated with COVID-19 hospitalizations, there is a need to quantify the economic impact of clinical trial outcomes to inform decisionmaking.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare longer-than-24-hour hospitalization costs (primary objective) and total health care costs (secondary objective) associated with COVID-19 care in the sotrovimab vs placebo group in the COMET-ICE trial.

METHODS:

This was a 2-step, retrospective, post hoc, within-trial economic analysis. Step 1 was a health care claims (MarketScan) database analysis to source unit cost data (2020 USD) from a US payer perspective for COVID-19 care-related resource use from April 1 through June 30, 2020, among adults diagnosed with COVID-19 at high risk of progression (similar to those enrolled in the COMET-ICE trial). Cost per day for an inpatient event stratified by the following maximum respiratory support levels was obtained: no respiratory support or oxygen therapy only, noninvasive ventilation, and invasive mechanical ventilation. Cost per event was obtained for outpatient resource use. Step 2 was the within-trial economic analysis, in which unit costs from Step 1 were applied to the resource use (based on maximum respiratory support and length of stay for inpatient events and number of visits for outpatient events) observed during the first 29 days post-randomization in COMET-ICE.

RESULTS:

A total of 1,057 patients from the intent-to-treat COMET-ICE population were included (sotrovimab, n = 528; placebo, n = 529). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were well balanced between groups. During 29 days of follow-up, mean (SD) costs for the primary endpoint, longer-than-24-hour hospitalization, were $2,827 ($15,545) in the placebo group and $485 ($5,049) in the sotrovimab group (difference, −$2,342; P < 0.0001). Total health care costs were $2,850 ($15,546) in the placebo group and $525 ($5,070) in the sotrovimab group (difference, −$2,325; P = 0.0021).

CONCLUSIONS:

This post hoc within-trial economic analysis of COMET-ICE data shows that early treatment with sotrovimab vs placebo may be associated with lower longer-than-24-hour hospitalization costs and total health care costs for COVID-19 care in high-risk patients with COVID-19. These findings may be important in informing decision-making regarding use of sotrovimab in clinical practice.

Plain language summary

Patients who are older or who have existing illnesses are at high risk of being seriously ill with COVID-19. A clinical trial showed that for these patients, the drug sotrovimab reduces the risk of being hospitalized or dying. In this study, we combined insurance claims and data from the trial. We found that using sotrovimab may save money by reducing the risk of being hospitalized.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

A substantial economic burden is associated with hospitalizations due to COVID-19. By demonstrating the significant reduction in hospitalization costs and total health care costs associated with sotrovimab compared with placebo, our findings may help inform decision-making regarding the introduction and use of sotrovimab in clinical practice.

The global impact of COVID-19 on public health has been exceptional; as of February 2022, more than 5.6 million deaths have been reported to the World Health Organization.1 COVID-19 disproportionally results in hospitalization or death in older patients and those with underlying risk factors in the form of comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease.2

The economic burden associated with COVID-19 is substantial. An analysis of Medicare fee-for-service inpatient claims found that total costs to the US health care system from inpatient hospitalizations due to COVID-19 would range from $9.6 billion to $16.9 billion in 2020.3 Furthermore, an analysis of the US Premier Healthcare COVID-19 Database found median hospital charges and costs were $43,986 and $12,046, respectively. Patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit and required invasive mechanical ventilation incurred hospital charges of $198,394 and costs of $54,402.4

Sotrovimab is an Fc-engineered human monoclonal antibody, which was developed from a parental antibody isolated from a survivor of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003.5-9 It targets a highly conserved epitope in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, and preclinical studies have shown it retains neutralizing activity against emerging variants of concern, including Delta and Omicron.6 Sotrovimab is administered once via a single 500-mg intravenous infusion.2

The COVID-19 Monoclonal antibody Efficacy Trial-Intent to Care Early (COMET-ICE; NCT04545060) trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of sotrovimab administered intravenously in high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19.10 Final results (n = 1,057) for the primary endpoint showed a 79% (P < 0.001) adjusted relative risk reduction in longer-than-24-hour hospitalization or death due to any cause in patients receiving sotrovimab (6/528; 1% [hospitalizations = 6; deaths = 0]) compared with placebo (30/529; 6% [hospitalizations = 29; deaths = 2]).10

In May 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted emergency use authorization for sotrovimab among patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 at high risk of progression to severe COVID-19.11 As of April 5, 2022, the FDA reversed its emergency use authorization for sotrovimab owing to increases in the proportion of COVID-19 cases caused by the Omicron BA.2 subvariant.12 Although preclinical studies demonstrated that sotrovimab retains activity against the full combination of mutations in the spike protein of the Omicron BA.1 subvariant,6 initial in vitro data suggest that the BA.2 subvariant exhibited marked resistance to most monoclonal antibodies tested, including sotrovimab.13 However, given the evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, continuous emergence of new variants, and real-world data,14-16 there may be an ongoing role for sotrovimab in future clinical practice in the United States. In addition, sotrovimab remains in use in other jurisdictions, including the European Union and United Kingdom.17,18 Substantial costs are associated with COVID-19 hospitalizations, and, as such, there is a need to quantify the economic impact of clinical trial outcomes and assess the cost implications of using different treatments.

A post hoc within-trial economic analysis of resource use from the COMET-ICE trial was therefore conducted, with the primary objective of comparing estimated hospitalization costs associated with COVID-19 care in the sotrovimab group vs the placebo group. Estimated total health care costs were also assessed as a secondary objective.

Methods

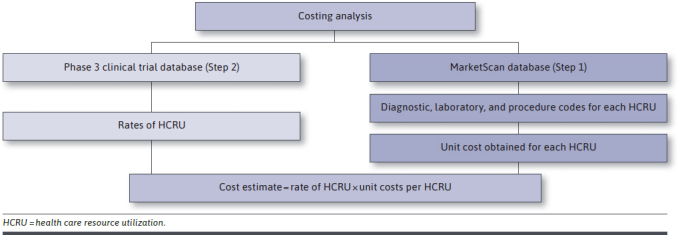

STUDY DESIGN

This was a retrospective, post hoc, within-trial economic analysis performed in 2 steps (Figure 1). Step 1 involved obtaining unit costs per COVID-19 care-related resource use from a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data. Step 2 was a within-trial economic analysis, in which unit costs obtained from Step 1 were applied to the resource use observed during the first 29 days post-randomization among the COMET-ICE intent-to-treat trial population.

FIGURE 1.

Study Design

COMET-ICE captured health care resource endpoints, which allowed for an analysis of sotrovimab’s effect on health care resource utilization (HCRU) and associated costs over the acute phase of illness. In COMET-ICE, the following endpoints were established a priori: all-cause longer-than-24-hour hospitalization through Day 29; proportion of patients with all-cause emergency department visits or hospitalizations of any duration through Day 29; and proportion of patients with progression to severe COVID-19 (defined as the requirement for supplemental oxygen) or critical COVID-19 (defined as requirement for mechanical ventilation) through Day 29. These prespecified endpoints were taken directly from the trial and used to inform the design of Step 1.

For Step 1, IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (Commercial) and Medicare Supplemental (Medicare) data were used. Unit cost per COVID-19 care-related resource use from a US payer perspective (valued in 2020 USD) was obtained using a retrospective, cross-sectional, event-based costing methodology. The target population included patients initially diagnosed with COVID-19 in an outpatient setting (using ≥ 1 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] diagnosis code U07.1) during April 1 through June 30, 2020. The final analysis sample was limited to adults deemed at high risk of disease progression to identify a sample similar to those enrolled in the COMET-ICE trial.

A 12-month pre-index period from April 1, 2019, was used to identify patient comorbidities to identify those at high risk of COVID-19 progression. Patients at high risk of progression were identified using a diagnosis of significant pulmonary disease (such as severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or pulmonary fibrosis), heart failure, chronic kidney disease, acute myocardial infarction, obesity, moderate/severe asthma (≥ 2 asthma diagnoses ≥ 30 days apart and ≥ 1 pharmacy or medical claim for a maintenance medication), or diabetes requiring medication or with complications during the year prior to and including the COVID-19 diagnosis. Per COMET-ICE, patients aged 55 years or older, irrespective of comorbidities, were also defined as high risk. Furthermore, patients meeting the following criteria were excluded to mimic the screening criteria applied in the trial: diagnosis for pregnancy, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, hepatitis B/C, any malignancy or evidence of oncolytic therapy/immunosuppressants during the year prior to the COVID-19 diagnosis date, and/or receipt of solid organ or allogenic stem cell transplant or chronic oral corticosteroid therapy during the 3 months prior to the COVID-19 diagnosis date.

For the above-identified sample, mean cost per COVID-19 care-related resource use (events with an ICD-10-CM code of U07.1 in any position on the claim) from April 1, 2020, through June 30, 2020, was calculated. The first COVID-19-related inpatient event (restricted to length of stay [LOS] > 1) after the outpatient diagnosis was used to obtain cost per day for an inpatient event. This was then further stratified by the maximum respiratory support level required during the event: no respiratory support or oxygen support only, noninvasive ventilation, and invasive mechanical ventilation. The type of respiratory support used during each inpatient event was identified using codes (Supplementary Table 1 (23.8KB, pdf) , available in online article), and the maximum level of respiratory support was used as a proxy for the severity of that inpatient event. For example, the unit cost estimate per day of an inpatient stay where invasive mechanical ventilation was the maximum level of respiratory support used was obtained by averaging the cost per day (total cost of inpatient stay/LOS) across all inpatient admission claims with invasive mechanical ventilation as the maximum respiratory support level. Cost per event was obtained for outpatient resource use, including emergency department visits, home health visits, physician office visits, and telehealth visits, and capturing laboratory and imaging costs.

For Step 2, the unit costs obtained from Step 1 were applied to the resource use observed in the COMET-ICE trial, allowing for a comparison of the costs associated with COVID-19 care (hospitalization and total costs) in the sotrovimab group vs the placebo group. The cost of acquiring and administering sotrovimab was not accounted for in these costs.

This study complied with all applicable laws regarding subject privacy. No direct contact or primary collection of individual human subject data occurred, and analyses omitted subject identification. This study therefore did not require informed consent or ethics committee/institutional review board approval.

STUDY VARIABLES

The primary endpoint of the within-trial economic analysis was the cost associated with longer-than-24-hour hospitalizations per patient for COVID-19 care, from the US payer perspective over the 29-day trial follow-up period. Care may include mechanical ventilation use, other forms of respiratory support, intensive care, other treatments, and diagnostic procedures.

The secondary endpoint was total health care costs, defined as outpatient and inpatient costs associated with COVID-19 care per patient from the US payer perspective over the 29-day trial follow-up period.

Key characteristics of the trial patients were collected (published elsewhere10), including demographics (age, sex, race, and ethnicity), subject disposition (follow-up days and treatment arm), and baseline disease characteristics (risk factors for COVID-19 progression, number of such risk factors, COVID-19 symptoms, and their duration).

DATA ANALYSIS

For continuous measures, descriptive statistics (mean ± SD, medians, and 25th and 75th percentiles) were provided. For categorical measures, the frequency and percentage were reported.

Both hospitalization and total COVID-19 care-related cost per patient were compared between the sotrovimab and placebo groups in the COMET-ICE trial using Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests (nonparametric). We obtained 95% CIs around the estimate of the difference in mean costs using 1,000 bootstrapped samples (of 1,057 patients each) with replacement.19,20 For each of the bootstrapped samples, the difference in mean costs was estimated yielding 1,000 estimations of the difference in mean costs. The 95% CIs around the difference in mean costs between the 2 groups were then estimated as the 2.5% percentile and 97.5% percentile of the 1,000 bootstrapped difference in means. Bootstrapping was not used to compute the difference in mean costs or the P values that test statistical significance of the difference.

All statistical tests performed tested a 2-sided hypothesis of no difference between treatment arms at a significance level of 0.05. All P values and 95% CIs reported are not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

Sensitivity analyses were performed using (1) the median estimate of unit costs from the overall claims sample and (2) the mean and median unit cost estimates from the Commercial population only.

Results

CLAIMS ANALYSIS (STEP 1)

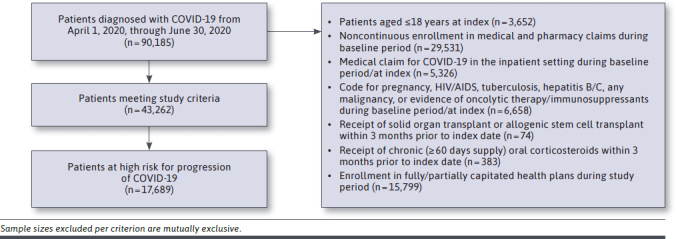

A total of 17,689 patients at high risk for progression of COVID-19 were identified from the claims analysis (Figure 2; HCRU among the sample is detailed in Supplementary Table 2 (23.8KB, pdf) , from which mean unit costs were then calculated). Mean unit costs obtained for longer-than-24-hour inpatient hospitalizations were $4,831/day when no respiratory support or only oxygen therapy was required. Mean unit costs associated with noninvasive ventilation and invasive mechanical ventilation were $6,067/day and $6,660/day, respectively. COVID-19-related HCRU among the high-risk population, and mean unit costs for all settings, are detailed in Table 1.

FIGURE 2.

Database Claims Analysis Study Attrition Diagram

TABLE 1.

Resource Utilization From the COMET-ICE Trial and Corresponding Unit Costs From Administrative Claims Data

| From COMET-ICE trial (Step 2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (%) | Placebo | Sotrovimab | ||||

| N = 1,057 | (100.0) | N = 529 | N = 528 | |||

| Any health care utilization, n (%) | 68 | (6.4) | 46 | (8.7) | 22 | (4.2) |

| Inpatient (> 24-hour hospitalizations ONLY), n (%) | 35 | (3.3) | 29 | (5.5) | 6 | (1.1) |

| No respiratory support or oxygen therapy only, n (%) | 27 | (77.1) | 21 | (72.4) | 6 | (100.0) |

| Cumulative LOS in days | 176 | 123 | 53 | |||

| Noninvasive ventilation, n (%) | 4 | (11.4) | 4 | (13.8) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Cumulative LOS in days | 64 | 64 | ||||

| Invasive MV, n (%) | 4 | (11.4) | 4 | (13.8) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Cumulative LOS in days | 77 | 77 | ||||

| ECMO, n (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Cumulative LOS in days | N/A | |||||

| Inpatient (≤ 24-hour hospitalizations ONLY)a, n (%) | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.2) |

| No respiratory support/oxygen therapy, n (%) | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.2) |

| Cumulative LOS in days | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Outpatient, n (%) | 36 | (3.4) | 20 | (3.8) | 16 | (3.0) |

| Emergency department visit, n (%) | 15 | (1.4) | 9 | (1.7) | 6 | (1.1) |

| Cumulative number of visits | 17 | 9 | 8 | |||

| Home health care visit, n (%) | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.2) |

| Cumulative LOS in days | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Internal medicine/GP, n (%) | 8 | (0.8) | 5 | (1.0) | 3 | (0.6) |

| Cumulative number of visits | 8 | 5 | 3 | |||

| Telehealth, n (%) | 10 | (1.0) | 5 | (1.0) | 5 | (1.0) |

| Cumulative number of visits | 10 | 5 | 5 | |||

| Urgent care, n (%) | 4 | (0.4) | 2 | (0.4) | 2 | (0.4) |

| Cumulative number of visitsb | 5 | 3 | 2 | |||

| Other, n (%) | 3 | (0.3) | 2 | (0.4) | 1 | (0.2) |

| Cumulative number of visitsc | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Cumulative number of visitsd | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| From claims (Step 1) | ||||

| Unit cost per resource use | ||||

| Main | Sensitivity 1 | Sensitivity 2 | Sensitivity 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall mean | Commercial mean | Overall mean | Commercial mean | |

| Any health care utilization | ||||

| Inpatient (> 24-hour hospitalizations ONLY) | ||||

| No respiratory support or oxygen therapy only | ||||

| Cumulative LOS in days | $4,831/day | $5,032/day | $4,103/day | $4,291/day |

| Noninvasive ventilation | ||||

| Cumulative LOS in days | $6,067/day | $6,067/day | $3,837/day | $3,837/day |

| Invasive MV | ||||

| Cumulative LOS in days | $6,660/day | $7,145/day | $5,963/day | $6,236/day |

| ECMO | ||||

| Cumulative LOS in days | N/A | |||

| Inpatient (≤24-hour hospitalizations ONLY)a | ||||

| No respiratory support/oxygen therapy | ||||

| Cumulative LOS in days | $4,831/day | $5,032/day | $4,103/day | $4,291/day |

| Outpatient | ||||

| Emergency department visit | ||||

| Cumulative number of visits | $1,197/visit | $1,212/visit | $945/visit | $983/visit |

| Home health care visit | ||||

| Cumulative LOS in days | $372/day | $301/day | $132/day | $137/day |

| Internal medicine/GP | ||||

| Cumulative number of visits | $110/visit | $110/visit | $92/visit | $92/visit |

| Telehealth | ||||

| Cumulative number of visits | $110/visit | $111/visit | $92/visit | $93/visit |

| Urgent care | ||||

| Cumulative number of visitsb | $110/visit | $110/visit | $92/visit | $92/visit |

| Other | ||||

| Cumulative number of visitsc | $110/visit | $110/visit | $92/visit | $92/visit |

| Cumulative number of visitsd | $110/visit | $111/visit | $92/visit | $93/visit |

a One participant in the treatment group had a ≤ 24-hour hospitalization. The cost of that hospitalization was not included in the primary objective results but was included in the secondary objective results (total costs). That participant had 2 consecutive days flagged as “in hospital” in the day-level status file, but the summary data suggested the participant was in the hospital for 1 day and ≤ 24 hours. Because 2 separate consecutive days were flagged as inpatient, the cost of that hospitalization for this participant was included as 2 × unit cost per day for consistency in method used to compute hospitalization costs.

b Procedure codes for urgent care visits were included in the unit costs for office visits; therefore, office visit unit costs were used.

c Other outpatient included “CXR done,” “EMS visit to house,” and “pulmonologist” (applied office visit unit cost for all 3 visits).

d Other outpatient included “speaking with pulmonologist” (applied telehealth unit cost).

COMET-ICE = COVID-19 Monoclonal antibody Efficacy Trial-Intent to Care Early; CXR = chest X-ray; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; EMS = emergency medical services; GP = general practitioner; LOS = length of stay; MV = mechanical ventilation; N/A = not applicable.

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS (STEP 2)

The COMET-ICE trial enrolled a total of 1,057 patients and all were included in this within-trial economic analysis (528 patients randomized to sotrovimab and 529 randomized to placebo). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar across the sotrovimab and placebo groups.10 Mean (SD) age of the trial population was 52.1 (14.9) years, and 46% were male. The most prevalent risk factor for COVID-19 progression was obesity, defined as body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 (63%), followed by age 55 years or older (47%) and diabetes requiring medication (22%). A total of 43% of patients had 2 or more risk factors for progression of disease.

In COMET-ICE, treatment with sotrovimab resulted in a 79% (95% CI = 50%-91%; P < 0.001) reduction in relative risk of all-cause longer-than-24-hour hospitalization or death due to any cause through Day 29 (6/528 [1%] of sotrovimab patients vs 30/529 [6%] placebo patients).10 Overall, low resource utilization was observed over the 29-day followup in the COMET-ICE trial. Of all the trial patients, 6.4% (n = 68) had any health care utilization (Table 1). A higher proportion of patients who received placebo incurred any HCRU compared with those on sotrovimab (8.7% vs 4.2%). Additionally, longer-than-24-hour hospitalizations were more common in the placebo group compared with the sotrovimab group (n = 29, 5.5% vs n = 6, 1.1%). Of those with a longer-than-24-hour inpatient stay, 8 patients (27.6%) in the placebo group required noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation (n = 4 for both forms of ventilation), compared with 0 patients in the sotrovimab group. Outpatient resource use was similar across treatment groups.

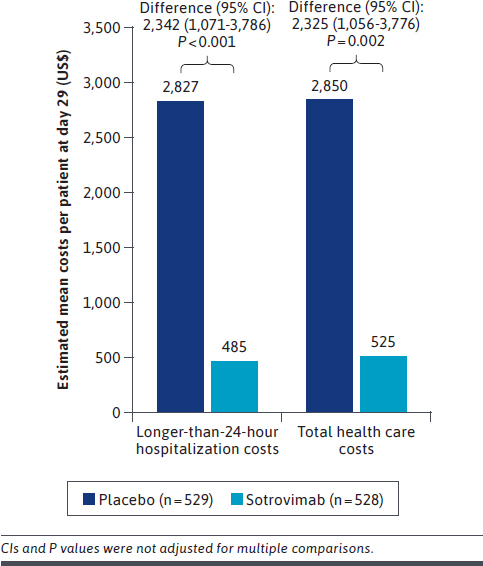

During 29 days of follow-up, mean (SD) costs across longer-than-24-hour hospitalization were $2,827 ($15,545) in the placebo group and $485 ($5,049) in the sotrovimab group. Mean hospitalization costs per patient in the sotrovimab group were therefore $2,342 (95% CI = $1,071-$3,786) lower than those in the placebo group (P < 0.001) (Figure 3). Average cost per longer-than-24-hour hospitalization among those with an event was $42,674 in the sotrovimab arm (all hospitalizations requiring no respiratory support/oxygen therapy only), compared with $51,562 in the placebo arm (hospitalizations requiring no respiratory support/oxygen therapy only: $28,296; noninvasive mechanical ventilation: $97,092; invasive mechanical ventilation: $128,205). Mean (SD) total health care costs were $2,850 ($15,546) in the placebo group and $525 ($5,070) in the sotrovimab group. Mean total health care costs per patient in the sotrovimab group were therefore $2,325 (95% CI = $1,056-$3,776) lower compared with those in the placebo group (P = 0.002).

FIGURE 3.

Estimated Mean Longer-Than-24-Hour Hospitalization and Total Health Care Costs at Day 29

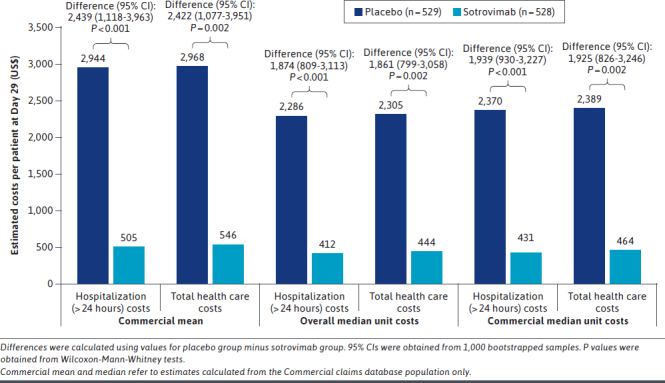

Results of the sensitivity analyses (using the overall median, mean costs from the Commercial population only, and median costs from the Commercial population only as unit costs) were consistent with the main results (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Estimated Longer-Than-24-Hour Hospitalization and Total Health Care Costs at Day 29 (Sensitivity Analyses)

Discussion

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated the rapid development and introduction of new vaccines and medicines for prevention and treatment of the disease. Evaluating the economic impact of such therapies is important to inform decision-making about their introduction and use in clinical practice. In the case of sotrovimab, this may inform decision-making regarding potential future use of sotrovimab and allocation of resources when further variants emerge. In addition, this study can inform decision-making outside of the United States, where sotrovimab continues to be used to treat COVID-19. This post hoc analysis based on COMET-ICE data is the first to examine the economic impact of sotrovimab. Our results show that early treatment with sotrovimab vs placebo may be associated with significantly lower longer-than-24-hour hospitalization costs and total health care costs for COVID-19 care in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 at high risk of disease progression. Results of sensitivity analyses were consistent with those for the primary and secondary objectives.

It is important to acknowledge the exclusion of acquisition and administration costs from this analysis. However, accounting for a wholesale acquisition cost of $2,100 and one-time administration costs of $450, sotrovimab is still cost neutral. In addition, our analysis only accounts for the first 29 days post-randomization, and potential longterm benefits of sotrovimab are therefore not considered. A recent Institute for Clinical and Economic Review of COVID-19 treatments report found that sotrovimab was cost-effective at standard levels in the United States when treatment costs of $2,100 were accounted for.21

Treatment of COVID-19 is associated with a substantial economic burden, especially when patients require hospitalization.3 Di Fusco et al4 studied more than 170,000 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 from April to October 2020 who were identified from the US Premier Health Database. Median hospital LOS was 5 days and median hospital costs were $12,046, increasing to 15 days and $54,402 in patients who required invasive mechanical ventilation while in intensive care. Another analysis of the Premier Healthcare Database hospital admissions data estimated costs for COVID-19 hospitalizations between April and December 2020. Median total hospital costs were $8,714 among patients not requiring supplemental oxygen. Total hospital costs increased when supplemental oxygen and noninvasive ventilation were required ($10,776 and $21,970, respectively). Highest total hospital costs of $47,454 were associated with use of invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.22 Neither of these studies was limited to patients at high risk of disease progression.

Treatments for COVID-19 that reduce risk of hospitalization and time to recovery and lower the need for oxygen support have great potential to conserve scarce hospital resources. Results from this within-trial analysis are based on hospitalization rates (approximately 6%) from the randomized controlled COMET-ICE trial. However, there are data to suggest that real-world hospitalization rates may be higher (in the range of 10%-20%),23-25 and 180-day readmission rates of 26.8% have been reported for hospitalized patients with COVID-19.26 This suggests that the potential for cost savings associated with sotrovimab treatment may be even greater than that found in the present analysis. In addition, this study did not examine how preexisting conditions associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes, such as diabetes and obesity,27 affect HCRU and costs. A recent study found that hypertension, diabetes, obesity, chronic renal failure, and rheumatic, hematologic, and neurologic diseases were associated with higher COVID-19 hospitalization costs, with total costs increased by 10%-24% according to the number of comorbidities.28 Further study of this in the context of sotrovimab is warranted.

Our study has a number of strengths. Particularly, our analyses were based directly on the results of the COMET-ICE clinical trial, rather than modeling the resource use and hence costs in the population. In addition, Step 1 of the analysis used the MarketScan database to obtain costs for patients with COVID-19 specifically, rather than using a proxy such as influenza, as has been previously done.29 Furthermore, the study allows for the estimation of cost savings due to reduced severity of inpatient events, in addition to the reduction in overall inpatient events and duration of hospital stays.

LIMITATIONS

As this is a within-trial economic analysis, results may not be generalizable to the use of sotrovimab beyond the analysis time frame of 29 days. In addition, the HCRU reported here is representative of a select clinical trial population with mild/moderate COVID-19 at high risk of progression and may therefore differ in the real world among patients with varying comorbidities and severity levels. The COMET-ICE trial population and the population from which the unit costs were derived are also different, and although steps were taken to ensure these were as aligned as possible, this may limit generalizability of the results. Furthermore, administrative claims data are intended for billing purposes as opposed to research purposes, so these data may be subject to coding errors and/or may not accurately reflect the patient’s clinical state. In addition, our study assumed that the costs associated with a hospitalization event were equally distributed across the days spent in hospital. There is also the possibility of incomplete data capture for post-hospitalization resource use, as this analysis only examined the first 29 days post-randomization. However, the benefit of the intervention may have been underestimated because of the study visits and protocol-driven care occurring. Finally, the analysis does not account for sotrovimab drug acquisition and administration costs (as discussed previously) or the use of oxygen support outside of hospital (although this would be far outweighed by the costs associated with hospitalization).

Conclusions

This within-trial economic analysis demonstrated that the reduction in hospitalization seen with sotrovimab in the COMET-ICE trial is associated with reduced health care costs. COVID-19-related hospitalization costs per patient were lower in the sotrovimab group compared with the placebo group from the COMET-ICE trial over the 29-day follow-up period. Similarly, COVID-19-related total health care costs (both inpatient and outpatient costs) per patient were lower in the sotrovimab group than in the placebo group. Although these findings are based on a within-trial analysis, they may be important in informing decision-making regarding the use of sotrovimab in clinical practice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Helen Birch (GSK) for her contribution to the study design, interpretation of results, and critical review of the manuscript. Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, including preparation of the draft manuscript under the direction and guidance of the authors, collating and incorporating authors’ comments for each draft, assembling tables and figures, grammatical editing, and referencing) was provided by Kathryn Wardle and Tony Reardon of Aura, a division of Spirit Medical Communications Group Limited (Manchester, UK), and was funded by GSK. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data required for interpretation of these results are included in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. 2022. Accessed February 1, 2021. https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al. Early treatment for Covid-19 with SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody sotrovimab. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(21):1941-50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markward N, Sloan C, Young J, et al. COVID-19 hospitalizations projected to cost up to $17B in US in 2020. Avalere Health. June 19, 2020. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://avalere.com/insights/covid-19-hospitalizations-projected-to-cost-up-to-17b-in-us-in-2020

- 4.Di Fusco M, Shea KM, Lin J, et al. Health outcomes and economic burden of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2021;24(1):308-17. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2021.1886109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinto D, Park Y-J, Beltramello M, et al. Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Nature. 2020;583(7815):290-5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2349-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cathcart AL, Havenar-Daughton C, Lempp FA, et al. The dual function monoclonal antibodies VIR-7831 and VIR-7832 demonstrate potent in vitro and in vivo activity against SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. 2021. Preprint posted online December 15, 2021. Accessed January 14, 2022. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.09.434607v10.full.pdf

- 7.Ko S-Y, Pegu A, Rudicell RS, et al. Enhanced neonatal Fc receptor function improves protection against primate SHIV infection. Nature. 2014;514(7524):642-5. doi: 10.1038/nature13612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zalevsky J, Chamberlain AK, Horton HM, et al. Enhanced antibody half-life improves in vivo activity. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(2):157-9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaudinski MR, Coates EE, Houser KV, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of the Fc-modified HIV-1 human monoclonal antibody VRC01LS: A phase 1 open-label clinical trial in healthy adults. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1):e1002493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al. Effect of sotrovimab on hospitalization or death among high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327(13):1236-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.2832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes additional monoclonal antibody for treatment of COVID-19. May 26, 2021. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-additional-monoclonal-antibody-treatment-covid-19

- 12.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA updates Sotrovimab emergency use authorization. May 4, 2022. Accessed May 15, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-updates-sotrovimab-emergency-use-authorization

- 13.Iketani S, Liu L, Guo Y, et al. Antibody evasion properties of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Nature. 2022;604(7906):553-6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04594-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radcliffe C, Palacios CF, Azar MM, et al. Real-world experience with available, outpatient COVID-19 therapies in solid organ transplant recipients during the omicron surge. Am J Transplant. Published online May 18, 2022. doi: 10.1111/ajt.17098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinchera B, Buonomo AR, Scotto R, et al. Sotrovimab in solid organ transplant patients with early, mild/moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection: A singlecenter experience. Transplantation. 2022;106(7):e343-5. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazzaferri F, Mirandola M, Savoldi A, et al. Exploratory data on the clinical efficacy of monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant of Concern. medRxiv. 2022. Preprint posted online May 9, 2022. Accessed May 15, 2022. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.06.22274613v1.full.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.European Medicines Agency. Xevudy. July 28, 2022. Accessed August 3, 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/xevudy

- 18.Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics for Xevudy. March 28, 2022. Accessed August 3, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-xevudy-sotrovimab/summary-of-product-characteristics-for-xevudy#summary-of-product-characteristics

- 19.Yu H, Greenberg M, Haviland A. The impact of state medical malpractice reform on individual-level health care expenditures. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(6):2018-37. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dean BB, Saundankar V, Stafkey-Mailey D, et al. Medication adherence and healthcare costs among patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension treated with oral prostacyclins: A retrospective cohort study. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2020;7(3):229-39. doi: 10.1007/s40801-020-00183-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Special Assessment of Outpatient Treatments for COVID-19. March 28, 2022. Accessed May 15, 2022. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ICER_COVID_19_Evidence_Report_032822.pdf

- 22.Ohsfeldt RL, Choong CK, Mc Collam PL, et al. Inpatient hospital costs for COVID-19 patients in the United States. Adv Ther. 2021;38(11):5557-95. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01887-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bariola JR, McCreary EK, Wadas RJ, et al. Impact of bamlanivimab monoclonal antibody treatment on hospitalization and mortality among nonhospitalized adults with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(7):ofab254. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Destache CJ, Aurit SJ, Schmidt D, et al. Bamlanivimab use in mild-to-moderate COVID-19 disease: A matched cohort design. Pharmacotherapy. 2021;41(9):743-7. doi: 10.1002/phar.2613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webb BJ, Buckel W, Vento T, et al. Real-world effectiveness and tolerability of monoclonal antibody therapy for ambulatory patients with early COVID-19. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(7):ofab331. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Günster C, Busse R, Spoden M, et al. 6-month mortality and readmissions of hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A nationwide cohort study of 8,679 patients in Germany. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treskova-Schwarzbach M, Haas L, Reda S, et al. Pre-existing health conditions and severe COVID-19 outcomes: An umbrella review approach and meta-analysis of global evidence. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):212. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02058-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miethke-Morais A, Cassenote A, Piva H, et al. COVID-19-related hospital cost-outcome analysis: The impact of clinical and demographic factors. Braz J Infect Dis. 2021;25(4):101609. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2021.101609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartsch SM, Ferguson MC, McKinnell JA, et al. The potential health care costs and resource use associated with COVID-19 in the United States. Heath Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):927-35. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]