Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Interventions for ankylosing spondylitis (AS) have improved patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in clinical studies. However, limited data exist associating these improvements with health care resource utilization (HCRU) or cost savings. Few studies have evaluated the economic impact of patient-reported physical status and related disease burden in patients with AS in the United States.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the association of PRO measures with HCRU and health care costs in patients with AS from a national US registry.

METHODS:

This cohort study included adults with a diagnosis of AS enrolled in the FORWARD registry from July 2009 to June 2019 who completed at least 1 questionnaire from January 2010 to December 2019 and completed the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) (0-3) and/or Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) (0-10). Patient-reported data for demographics, clinical characteristics, and PROs were collected through questionnaires administered biannually and reported from the most recent questionnaire. Patient-reported HCRU and total health care costs (2019 US dollars) for hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, outpatient visits, diagnostic tests, and procedures were captured during the 6 months prior to the most recent survey completion. The relationship between HAQ-DI or BASDAI and HCRU outcomes was assessed using negative binomial regression models, and the relationship between HAQ-DI or BASDAI and the cost outcomes was evaluated using generalized linear models with γ distribution and log-link function.

RESULTS:

Overall, 334 patients with AS who completed the HAQ-DI (n = 253) or BASDAI (n = 81) were included. The mean (SD) HAQ-DI and BASDAI scores at the time of patients’ most recent surveys were 0.9 (0.7) and 3.7 (2.3), respectively. HAQ-DI score was positively associated with number of hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, and diagnostic tests, whereas BASDAI was not associated with HCRU outcomes. Overall annualized mean (SD) total health care, medical, and pharmacy costs for patients with AS were $44,783 ($40,595); $6,521 ($12,733); and $38,263 ($40,595), respectively. Annualized total health care, medical, and pharmacy costs adjusted for confounders increased by 35%, 76%, and 26%, respectively, for each 1.0-unit increase in HAQ-DI score (coefficient [95% CI]: 1.35 [1.15-1.58], 1.76 [1.22-2.55]; both P < 0.01 and 1.26 [1.04-1.52]; P < 0.05, respectively); BASDAI score was not significantly associated with cost outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS:

Higher HAQ-DI scores were associated with higher HCRU and total health care costs among patients with AS in FORWARD, but BASDAI scores were not. These findings indicate that greater functional impairment may impose an increased economic burden compared with other patient-reported measures of AS.

Plain language summary

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) can answer specific questions as part of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) or Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) to show how AS affects how they are able to complete common tasks. In this study, patients with a worse HAQ-DI score had more hospitalizations, emergency department visits, doctor visits, and tests and spent more money to care for their disease; BASDAI did not have the same results.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

AS physical burden can be assessed with the BASDAI or HAQ-DI. Increased HAQ-DI scores were associated with higher health care resource utilization and related health care expenditures in patients with AS; however, BASDAI score was not. These findings suggest that improved physical burden in patients with AS, perhaps through therapeutic interventions, may reduce the resource and economic burden for health care payers and systems.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), also known as radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, is a chronic inflammatory disease that primarily involves the sacroiliac joints and axial skeleton and presents with numerous clinical manifestations.1 AS is characterized by inflammatory back pain, radiographic sacroiliitis, and progressive spinal stiffness and is associated with postural abnormalities, hip and buttock pain, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, and dactylitis.2 In the absence of adequate disease control, systemic inflammation in patients with AS can trigger extraarticular manifestations, including psoriasis, acute anterior uveitis, and inflammatory bowel disease.2-4 AS affects approximately 0.35% of the population in the United States.5 Age of onset is typically younger than 40 years, when patients are primarily of working age6; therefore, the lifetime impact of the burden of disease for AS can be high.

AS is associated with high disease burden from progressive loss of physical function and pain linked to disease activity, which can significantly affect patient quality of life (QoL) and functional status.7-10 Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures are used to assess disease burden, QoL, and therapeutic response for AS.11-13 The PRO measures Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)14 and Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI)15 are frequently used to measure disease activity16-19 and physical function,20-22 respectively, in clinical trials for rheumatic diseases; both have been shown to be significantly associated with clinical response and treatment retention. Studies in AS have reported significant improvements in BASDAI scores following treatment with biologic therapies,23-27 and HAQ-DI scores have also been reported to be significantly correlated with clinical response to treatment and radiographic progression in patients with rheumatic disease.28-30

Patients with AS experience substantial economic burden because of increased need for health care resource utilization (HCRU) for disease management and burden from work impairment and productivity loss.31-35 Increased disease activity and poorer physical function are associated with higher costs of illness among patients with AS.7,36 Treatments for AS have been shown to improve PRO measures in clinical studies23,37; however, there are limited data associating these improvements with HCRU or cost savings in a real-world setting. Additionally, prior studies evaluating the impact of functional disability and QoL on health care costs in AS primarily involved patients outside the United States.36,38-40 Understanding the relationship between PROs and HCRU can facilitate discussions about patient access to optimal treatments in a timely manner, which may subsequently lead to a reduction in direct costs and HCRU for the health care system. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association of PRO measures, particularly HAQ-DI or BASDAI score, with HCRU and health care costs in patients with AS from a national US registry.

Methods

DATA SOURCE AND PATIENT POPULATION

FORWARD, the National Databank for Rheumatic Diseases, is a longitudinal observational databank that collects patient-reported data through questionnaires administered every 6 months. Patients recruited from rheumatology clinics throughout the United States have patient-reported, physician-diagnosed diseases. This cohort study included adult participants with a diagnosis of AS enrolled in FORWARD from July 2009 to June 2019 who completed at least 1 questionnaire from January 2010 to December 2019 and completed the HAQ-DI and/or BASDAI (added in 2018) questionnaire. Patients with a primary diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, reactive arthritis, or an autoimmune disorder other than AS on the most recent questionnaire were excluded.

ASSESSMENTS AND OUTCOMES

Data were collected from the most recent questionnaire and included patient demographics (age, sex, race, education level, insurance type, marital status, and geographic location), clinical characteristics (disease duration, smoking status, rheumatic disease comorbidity index,41 and comorbid conditions), treatment history (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [DMARDs], biologics, prednisone, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], and opioids), and work productivity measures (patient-reported current working status, percentage of work time missed, and percentage of impairment while working).

PROs reported on the most recent questionnaire included measures of health and functional status, such as HAQ-DI score (comprising 20 questions across 8 categories of daily activities; scale 0 [no difficulty completing task] to 3 [unable to complete task]; higher score corresponds to higher disability), BASDAI score (includes 6 questions to assess fatigue, pain/swelling, localized tenderness, and morning stiffness; scale 0 [no disease activity] to 10 [worst disease activity]; a cutoff of ≥ 4 for moderate/severe disease activity), Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 29-item (PROMIS-29) (categories include physical function, anxiety, depression, fatigue, pain interference, sleep disturbance, and satisfaction with social roles; each category has a scale of 1 to 5; a higher score represents worse outcomes in all categories, except physical function and satisfaction with social roles) score, and patient-reported presence of heel or low back pain (none, mild, moderate, or severe).

HCRU and total health care costs were assessed during the period covering 6 months prior to respondents’ survey completion and were annualized by multiplying by 2. Collected data reported by patients on the questionnaires consisted of HCRU (number of hospitalizations, emergency department [ED] visits, outpatient visits, procedures, and diagnostic tests). Health care costs were estimated by linking medical HCRU to Medicare fee schedule amounts; pharmacy costs were assessed using the wholesale acquisition cost from the ProspectoRx database. All costs included both reimbursement to the payer and patient out-of-pocket cost, and these costs were inflated to 2019 US dollars using the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index.

The primary objective was to evaluate the association of HAQ-DI or BASDAI score with annualized HCRU and total health care costs in patients with AS. Secondary objectives were to describe HCRU, total health care costs, medical costs, and pharmacy costs by increases in HAQ-DI and BASDAI scores using linear regression models and to assess the association of changes in other PRO measures (eg, PROMIS-29, back and heel pain) with HCRU and health care costs. Sensitivity analyses evaluated the association of changes in HAQ-DI and BASDAI scores with HCRU and costs in patients with AS adjusted for (1) race, income, education level, and geographic area and (2) physician-confirmed diagnosis for each model and the significant univariate predictors.

DATA ANALYSIS

Data on patient demographics, clinical characteristics, treatment histories, PRO measures, and work productivity measures were summarized descriptively.

The association between HAQ-DI or BASDAI score and annualized HCRU outcomes (number of hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, procedures, and diagnostic tests) was assessed using negative binomial regression models adjusted for confounders that were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) in univariate models. Associations between HAQ-DI or BASDAI score and annualized health care costs (total, medical, pharmacy) were determined using generalized linear models with γ distribution and log-link function adjusted for confounders and are reported as incremental dollar amount change from base value per 1.0-unit increase in HAQ-DI score.

HAQ-DI and BASDAI are commonly used in AS, and PROMIS-29 was included to assess if PROs that can be applied across diseases would also be predictive of changes in HCRU and cost outcomes. Specifically, PROMIS-29 category raw scores were transformed to standardized T-score metrics, with a mean (SD) of 50 (10), to assess the relationship between PROMIS-29 categories and HCRU and costs. PROMIS-29 raw score conversion tables used to produce the final T-scores have previously been described.42

Covariates for multivariable analyses were identified using bivariate analyses, with a significance cutoff of 5%, and included race, income, education level, geographic region, rheumatic disease comorbidity index, insurance type, age, disease duration, physician-reported AS diagnosis, and treatment profile (opioid, biologic, or prednisone use). Multivariable regression models were conducted to estimate the relationship between HCRU (hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, procedures, and diagnostic tests) and cost outcomes (total health care cost, total medical costs, and pharmacy cost) and functional disability, as measured by HAQ-DI or BASDAI. The sensitivity analyses were computed similarly to the primary analyses, with each model adjusted for additional prespecified variables, which included (1) race, income, education level, geographic area, and significant univariate predictors and (2) a cohort of patients with a physician-confirmed diagnosis. No imputations were conducted for missing data, and the last value was carried forward when available. The FORWARD registry includes a series of data quality control checks and complete details have been previously published.43 P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA software version 14.2 (StataCorp, LLC).

Results

STUDY POPULATION AND PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

Overall, 334 patients with AS enrolled in the FORWARD databank who completed at least 1 BASDAI and/or HAQ-DI questionnaire were included in this analysis; of these patients, 81 completed the BASDAI and 253 were missing a BASDAI questionnaire. Overall, 61.7% of patients were female, 94.6% were White, and the mean (SD) age and disease duration were 54.4 (14.3) years and 21.6 (14.6) years, respectively (Table 1). A total of 37.4% patients had a rheumatic disease comorbidity index of 3 or more. The most frequent comorbidities reported were hypertension (30.8%), dyslipidemia (28.3%), depression (23.4%), gastrointestinal disorders (19.5%), and cardiovascular disease (18.9%). The mean (SD) HAQ-DI and BASDAI scores at the time of patients’ most recent surveys were 0.9 (0.7) and 3.7 (2.3), respectively, and 71.2% of patients reported moderate or severe back pain. Generally, the characteristics for the 253 patients who were missing a BASDAI questionnaire were similar to those of the 334 patients in the overall cohort who completed the HAQ-DI and/or BASDAI. However, the 81 patients who completed the BASDAI questionnaire had longer disease duration, with a mean (SD) of 26.6 (16.5) years; a higher proportion (45.7%) had a rheumatic disease comorbidity index of 3 or more; and lower proportions of patients reported current and past use of biologics (35.8%), NSAIDs (35.8%), and opioids (17.3%) than patients who completed only the HAQ-DI and did not complete the BASDAI questionnaire.

TABLE 1.

Demographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Disease Activity Measures in Patients With AS Who Responded to the HAQ-DI and/or BASDAI

| Characteristic | Completed the HAQ-DI and/or BASDAI (N = 334) | Completed the BASDAI (n = 81) | Did not complete the BASDAI (n = 253) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 54.4 (14.3) | 58.7 (13.6) | 53.1 (14.2) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 206 (61.7) | 50 (61.7) | 156 (61.7) |

| Male | 128 (38.3) | 31 (38.3) | 97 (38.3) |

| White race, n (%) [n]a | 282 (94.6) [298] | 72 (93.5) [77] | 219 (95.0) |

| Insurance status, n (%) | |||

| Private | 114 (34.1) | 27 (33.3) | 87 (34.4) |

| Medicare | 135 (40.4) | 35 (43.2) | 100 (39.5) |

| Medicaid | 30 (9.0) | 8 (9.9) | 22 (8.7) |

| Other | 43 (12.9) | 10 (12.4) | 33 (13.0) |

| None | 12 (3.6) | 1 (1.2) | 11 (4.4) |

| Disease duration, mean (SD), years [n] | 21.6 (14.6) [303] | 26.6 (16.5) [78] | 19.8 (13.5) [225] |

| Rheumatic disease comorbidity index, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 54 (16.2) | 11 (13.6) | 43 (17.0) |

| 1 | 93 (27.8) | 23 (28.4) | 70 (27.7) |

| 2 | 62 (18.6) | 10 (12.4) | 52 (20.6) |

| ≥ 3 | 125 (37.4) | 37 (45.7) | 88 (34.8) |

| Comorbid condition, n (%) [n]b | |||

| Hypertension | 103 (30.8) [334] | 26 (32.1) [81] | 77 (30.4) [253] |

| Dyslipidemia | 94 (28.3) [332] | 26 (32.1) [81] | 68 (27.1) [251] |

| Depression | 78 (23.4) [334] | 11 (13.6) [81] | 67 (26.5) [253] |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 65 (19.5) [334] | 12 (14.8) [81] | 53 (21.0) [253] |

| Cardiovascular disease | 63 (18.9) [334] | 19 (23.5) [81] | 44 (17.4) [253] |

| AS treatment history (current and past use), n (%) [n]c | |||

| DMARDs | 114 (35.5) [321] | 26 (32.1) [81] | 88 (36.7) [240] |

| Biologics | 141 (43.9) [321] | 29 (35.8) [81] | 112 (46.7) [240] |

| Prednisone | 33 (11.3) [291] | 8 (12.1) [66] | 25 (11.1) [225] |

| NSAIDs | 160 (49.8) [321] | 29 (35.8) [81] | 131 (54.6) [240] |

| Opioids | 101 (30.2) [334] | 14 (17.3) [81] | 87 (34.4) [253] |

| AS disease activity, mean (SD) [n] | |||

| HAQ-DI | 0.9 (0.7) [333] | 0.7 (0.6) [81] | 0.94 (0.72) [253] |

| PROMIS-29 categories | |||

| Physical function | 42.6 (9.2) [169] | 45.2 (9.3) [81] | 39.9 (8.2) [79] |

| Anxiety | 51.2 (14.3) [13] | – | 51.2 (14.3) [13] |

| Depression | 50.8 (12.9) [13] | – | 50.8 (12.9) [13] |

| Fatigue | 54.4 (11.5) [158] | 51.6 (11.8) [80] | 57.2 (10.6) [78] |

| Pain interference | 57.8 (9.7) [94] | 53.9 (10.1) [32] | 59.9 (8.9) [62] |

| Sleep disturbance | 52.4 (8.6) [158] | 51.0 (8.7) [80] | 53.9 (8.3) [78] |

| Satisfaction with social roles | 48.5 (10.0) [158] | 50.4 (10.5) [80] | 46.6 (9.1) [78] |

| BASDAI | 3.7 (2.3) [81] | 3.7 (2.3) [81] | – |

| Heel pain, n (%) | n = 186 | n = 40 | n = 146 |

| Mild | 40 (21.5) | 5 (12.5) | 35 (24.0) |

| Moderate/severe | 49 (26.3) | 8 (20.0) | 41 (28.1) |

| Back pain, n (%) | n = 285 | n = 65 | n = 220 |

| Mild | 72 (25.3) | 18 (27.7) | 54 (24.6) |

| Moderate/severe | 203 (71.2) | 44 (67.7) | 159 (72.3) |

a [n] represents the number of patients with data available.

b Comorbidities reported by more than 10% of the study cohort.

c Treatment history included use at the time of survey completion and use within the 6 months prior.

AS = ankylosing spondylitis; BASDAI = Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; HAQ-DI = Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PROMIS-29 = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 29-item form.

HCRU AND ECONOMIC BURDEN AMONG PATIENTS WITH AS

Among patients with AS who completed at least 1 HAQ-DI or BASDAI questionnaire, the most common settings of HCRU were outpatient visits and procedures with mean (SD) annualized use of 18.9 (13.3) and 4.5 (6.4), respectively (Table 2). Overall, mean (SD) total health care costs for patients were $44,783 ($40,595), with pharmacy costs ($38,263 [$40,595]) representing the driver of health care expenditures. Additionally, patients reported a mean (SD) of $6,521 ($12,733) for medical costs related to AS, of which costs for hospitalizations ($3,459 [$11,912]) and outpatient visits ($2,160 [$1,547]) attributed the numerically highest portion of total medical costs.

TABLE 2.

Average Annualized HCRU and Costs Among Patients With AS Who Completed At Least 1 HAQ-DI or BASDAI Questionnaire

| Outcome | Mean (SD) for patients with AS who completed the HAQ-DI and/or BASDAI |

|---|---|

| HCRU, no. of uses | |

| Hospitalization | 0.30 (0.96) |

| ED visit | 0.62 (1.56) |

| Outpatient visit | 18.94 (13.30) |

| Diagnostic tests | 0.41 (1.02) |

| Procedures | 4.54 (6.35) |

| Medical costs, USD | |

| Total health care costs | 44,783 (40,595) |

| Medical costsa | 6,521 (12,733) |

| Hospitalizations | 3,459 (11,912) |

| ED visits | 242 (579) |

| Outpatient visits | 2,160 (1,547) |

| Diagnostic tests | 491 (655) |

| Procedures | 169 (615) |

| Pharmacy costs | 38,263 (40,595) |

a Includes costs for hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, procedures, and diagnostic tests.

AS = ankylosing spondylitis; BASDAI = Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; ED = emergency department; HAQ-DI = Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; HCRU = health care resource utilization; USD = US dollar.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HCRU AND PRO MEASURES

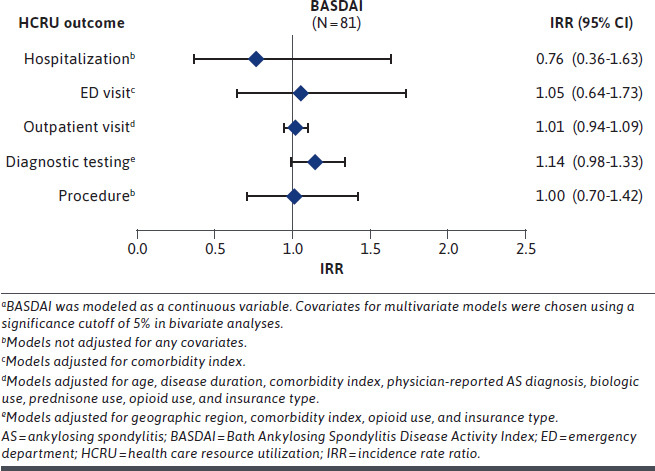

Increasing HAQ-DI score was significantly associated (incidence rate ratio [IRR] [95% CI]) with an increased number of hospitalizations (2.51 [1.36-4.63]; P < 0.01), ED visits (1.70 [1.04-2.77]; P < 0.05), outpatient visits (1.35 [1.18-1.55]; P < 0.01), and diagnostic tests (1.67 [1.28-2.18]; P < 0.01) (Figure 1). In a sensitivity analysis, adjusting for race, income, education, and geographic region, increasing HAQ-DI score was significantly associated (IRR [95% CI]) with an increased risk of number of hospitalizations (2.64 [1.28-5.45]; P < 0.01), outpatient visits (1.14 [1.22-1.63]; P < 0.01), and diagnostic tests (1.65 [1.22-2.22]; all P < 0.01) for patients with AS (Supplementary Figure 1 (877.2KB, pdf) , available in online article). An additional analysis of patients with a physician-confirmed diagnosis for AS was in line with these findings, with a significant association between HAQ-DI score and hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and diagnostic tests (Supplementary Figure 2 (877.2KB, pdf) ). In contrast, among patients who completed the BASDAI questionnaire, BASDAI score was not significantly associated with any HCRU outcomes measured in the primary analysis (Figure 2), the sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Figure 3 (877.2KB, pdf) ), or the physician-confirmed diagnosis cohort (Supplementary Figure 4 (877.2KB, pdf) ).

FIGURE 1.

Association of Adjusted Annualized Health Care Resource Utilization With HAQ-DI Score Among Patients With AS in the Primary Analysisa

FIGURE 2.

Association of Adjusted Annualized Health Care Resource Utilization With BASDAI Score Among Patients With AS in the Primary Analysisa

Several PROMIS-29 categories assessed were associated with minor but significant risk of increased number of outpatient visits with worsened PRO measures, including fatigue, pain interference, and sleep disturbance (Supplementary Figure 5 (877.2KB, pdf) ). Conversely, an improvement in PROMIS-29 scores for physical function and satisfaction with ability to participate in social roles was significantly associated with a decrease in the number of outpatient visits, whereas an improvement in satisfaction with social roles was associated with a minor but significant reduction in the risk of diagnostic testing and procedures. Furthermore, there was a significant direct relationship between increased severity of low back pain and a risk of increased number of outpatient visits, as seen with moderate/severe low back pain, compared with mild or no low back as reference (Supplementary Figure 5 (877.2KB, pdf) ).

ASSOCIATION OF PRO MEASURES WITH HEALTH CARE COSTS

A 1.0-unit increase in HAQ-DI score was significantly associated (incremental amount [IA] [95% CI]) with a 35% (1.35 [1.15-1.58]; P < 0.01) increase in total health care costs, which were driven by a 76% (1.76 [1.22-2.55]; P < 0.01) and 26% (1.26 [1.04-1.52]; P < 0.05) increase in medical costs and pharmacy costs, respectively, for this study population (Table 3). Conversely, no significant association (IA [95% CI]) was found between BASDAI score and total health care costs (1.03 [0.93-1.16]), medical costs (1.05 [0.91-1.22), or pharmacy costs (1.03 [0.91-1.15]) for patients with available BASDAI data; similar results were determined with a 2.0-unit increase in BASDAI score (data not shown). The sensitivity analysis further demonstrated the significant relationship (IA [95% CI]) between a 1.0-unit increase in HAQ-DI score and increased total health care costs, medical costs, and pharmacy costs with a 1.51 (1.24-1.83), 2.00 (1.34-2.99), and 1.38 (1.11-1.73; all P < 0.01) time increase in costs, respectively. In the sensitivity analysis, no significant association (IA [95% CI]) was found between BASDAI score and health care expenditures for total health care costs (1.06 [0.94-1.21), medical costs (1.03 [0.87-1.22]), or pharmacy costs (1.06 [0.92-1.21]) for patients who completed the BASDAI questionnaire. Similar results were determined for a BASDAI score of 4 or more in the primary analysis, sensitivity analysis, and physician-confirmed diagnosis cohort, with no significant association found for health care costs compared with BASDAI scores less than 4 (Table 3). Improvements in scores for physical function and satisfaction with social roles in the PROMIS-29 were associated with minor but significant reductions in total health care and pharmacy costs (Supplementary Table 1 (877.2KB, pdf) ). Based on model predictions, adjusted average total health care costs increased with increasing HAQ-DI (Supplementary Figure 6 (877.2KB, pdf) ) and BASDAI (Supplementary Figure 7 (877.2KB, pdf) ) scores in 0.5-unit and 1.0-unit increments, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Relationship Between Adjusted Health Care Costs and HAQ-DI or BASDAI Score in Patients With AS Who Completed the HAQ-DI or BASDAI Questionnaire

| Total health care costs, USD | Medical costs, USDa | Pharmacy costs, USD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base value | Incremental amountb (95% CI) | Base value | Incremental amountb (95% CI) | Base value | Incremental amountb (95% CI) | |

| Primary analysisc | ||||||

| HAQ-DI | 14,928 | 1.35 (1.15-1.58)d | 3,621 | 1.76 (1.22-2.55)d | 11,545 | 1.26 (1.04-1.52)e |

| BASDAI | 19,149 | 1.03 (0.93-1.16) | 2,423 | 1.05 (0.91-1.22) | 16,916 | 1.03 (0.91-1.15) |

| BASDAI ≥ 4f | 19,666 | 1.22 (0.73-2.03) | 3,244 | 1.18 (0.64-2.17) | 17,121 | 1.17 (0.67-2.03) |

| Sensitivity analysisg | ||||||

| HAQ-DI | 13,333 | 1.51 (1.24-1.83)d | 617 | 2.00 (1.34-2.99)d | 36,571 | 1.38 (1.11-1.73) |

| BASDAI | 12,594 | 1.06 (0.94-1.21) | 2,660 | 1.03 (0.87-1.22) | 11,603 | 1.06 (0.92-1.21) |

| BASDAI ≥ 4h | 13,182 | 1.59 (0.85-2.95) | 2,860 | 1.08 (0.53-2.21) | 10,987 | 1.57 (0.80-3.07) |

| Physician-confirmed diagnosis cohorth | ||||||

| HAQ-DI | 18,996 | 1.66 (1.28-2.14)d | 3,210 | 2.28 (1.43-3.65)d | 13,135 | 1.38 (1.07-1.78)e |

| BASDAI | 27,146 | 1.08 (0.93-1.25) | 1,935 | 1.07 (0.95-1.21) | 19,673 | 1.03 (0.89-1.20) |

| BASDAI ≥ 4f | 30,773 | 1.59 (0.77-3.28) | 2,095 | 1.53 (0.97-2.41) | 20,089 | 1.28 (0.63-2.60) |

a Includes costs for hospitalizations, emergency department visits, outpatient visits, procedures, and diagnostic tests.

b Multiplicative incremental dollar amount for change from corresponding base value per 1.0-unit increase in HAQ-DI score.

c Adjusted for covariates significant at 5% in bivariate analyses: geographic region, rheumatic disease comorbidity index, and opioid use.

d P < 0.01.

e P < 0.05.

f Health care costs were determined with BASDAI scores less than 4 as reference.

g Multivariate model further adjusted for race, income, education, geographic area, and significant univariate predictors.

h Included patients who had a physician-confirmed diagnosis (n = 167). Model adjusted for comorbidity index and insurance type.

AS = ankylosing spondylitis; BASDAI = Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; HAQ-DI = Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; USD = US dollar.

Discussion

This real-world study of US patients with AS is one of the first to describe the direct association between physical function, measured by the HAQ-DI and BASDAI questionnaires, and HCRU and health care costs. The main drivers for the relationship between increased risk of HCRU and increased HAQ-DI score were hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, and diagnostic testing for this study cohort. Furthermore, every 1.0-unit increase in HAQ-DI score was significantly associated with increased expenditures for total health care costs, medical costs, and pharmacy costs. Although there were no significant associations between BASDAI score and HCRU or health care costs, there were trends in minor increases in HCRU and health care costs with worsening BASDAI score that should be further studied to assess the potential for a significant relationship.

Our mean HCRU and health care costs findings among patients with AS are similar to those previously reported including patients with AS. A US-based retrospective descriptive study that included claims data for 6,679 patients with AS found similar trends in average HCRU.33 The main contributors to HCRU were the mean (SD) number of outpatient office visits (10.56 [7.56]) and outpatient services (14.16 [15.72]) per patient per year, although values differed to varying degree from the use seen in this study.33 Although the costs for total reimbursements, which included copays, deductibles, and coinsurance, were lower than those observed in our study; similar trends in increased mean (SD) health care costs attributed to all-cause health care costs of $33,285 ($46,363) per patient per year, and outpatient pharmacy costs were also substantial contributors to increased expenditures, with a mean (SD) of $14,074 ($16,381).33 Another retrospective, observational study that included claims data for 4,288 US patients with AS found the highest mean (SD) all-cause HCRU to be for office visits (10.8 [7.7]), followed by hospitalizations (6.6 [9.6]).31 Additionally, all-cause mean (SD) direct costs for Medicare employer-sponsored, plan-paid medical expenditures for hospitalizations ($4,285 [$26,503]) and office visits ($1,571 [$2,242]) were the drivers of expenditures for patients with AS, which is consistent with the distribution of expenditure categories and ranges seen in our observations in this study. Trends in the main drivers of HCRU and health care costs described in this study are in line with those previously reported, although increased expenditures and generally higher resource use for the shared health care resource categories assessed were observed for patients included in this cohort.

Patient characteristics in this study population, such as biologic use and comorbidity burden, could potentially contribute to the high utilization and health care costs observed in these findings. Patients with AS have an increased risk of developing comorbidities, compared with the general population,44,45 and treatment patterns among patients with AS have been shown to be inconsistent, with frequent medication switching and discontinuation, which may be the result of unstable disease control or inadequate treatment response32,46; these factors may impact HCRU and health care costs for patients with AS. More than one-third of patients (37.4%) had a rheumatic disease comorbidity index of 3 or more, and approximately one-third of patients reported treatment history with prescription DMARDs (35.5%), biologics (43.9%), and opioids (30.2%). A retrospective study that included expenditure data covered by national health insurance of Korea for 1,111 patients with AS in Korea found that patients incurred 3.3 times higher annual health expenditures compared with matched controls who were insured and did not have a diagnosis for AS, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus.47 This study conducted by Lee et al also reported that a higher comorbidity burden, as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index, was significantly associated with increased annual health care, and a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score was a significant risk factor for physician-assessed disability.47 A recent retrospective analysis of US claims data for 719 patients with AS who newly initiated a biologic, including those who had switched biologics or discontinued a biologic, reported similar all-cause HCRU, as seen in this study, with the highest mean (SD) use for outpatient visits (31.31 [22.69]), followed by comparable hospitalizations and ED visits, as seen in this study.35 Additionally, all-cause health care costs, from private insurance claims, Medicare-covered payments paid by employers, and out of pocket expenses, were lower for all patients who newly initiated a biologic compared with our cohort; however, the study did find that patients who switched or discontinued biologics had higher HCRU and those who switched prescription biologics had the highest total health care costs. Further studies need to be conducted to assess the degree to which patient characteristics such as prescription drug use and comorbidity burden can influence HCRU and health care costs in relationship to PRO measures of physical disability.

Few data are available on the relationship between physical function and HCRU and health care expenditures, most of which has been conducted outside the United States.38-40 One prospective, longitudinal survey-based study of 241 US patients with AS reported functional disability, as measured by the HAQ for the Spondyloarthropathies (HAQ-S)—a modified version of the HAQ that allows for increased capturing of more relevant functional disability—was a significant predictor of higher costs; in a multivariate analysis, the risk of patients having high costs (> $10,000) increased 3 times for every 1.0 unit increase in HAQ-S score.48 This study was published in 2002, so it is difficult to compare costs with the data reported in our study, as the treatment landscape was different at that time compared with now. Our study does take these factors into account and may better represent the current economic burden associated with disease management and decreased functional ability seen with AS.

Similarly, a cross-sectional, retrospective study in a cohort of 545 Canadian patients found that costs increased significantly with worsening physical function (measured by Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index [BASFI]) and high disease activity (BASDAI), which is aligned with findings presented in our study. In contrast to the finding from our study, they reported an inverse relationship between resource utilization and BASDAI and BASFI scores, yet different cutoffs were used.40 Additionally, a retrospective, cross-sectional study of 145 patients in Hong Kong with AS reported that functional impairment, as measured by BASDAI and BASFI, was a driver of direct costs; however, only BASFI was significantly associated with direct costs related to AS.49 Moreover, a cross-sectional postal survey-based study in a sample of 1,000 patients with AS in the United Kingdom demonstrated a direct correlation between increased 3-month total National Health Service or self-funded costs and higher disease activity (BASDAI, r = 0.46; P < 0.001) and functional impairment (BASFI, r = 0.53; both P < 0.001).38 The results presented in this study further substantiate the direct relationship between physical disability and HCRU and costs, as measured with HAQ-DI. Conversely, the results for this cohort did not determine a significant relationship between disease activity (measured by BASDAI) and HCRU or health care costs, even though BASDAI is tailored more to AS than the HAQ DI questionnaire. A BASDAI score of 4 or more is generally considered the cutoff for active disease, and the relatively low mean (SD) BASDAI score (3.7 [2.3]) seen in this cohort, compared with other similar studies (range 4.3-6.3),36-38,40 could have partially contributed to the findings. This may be reflective of the study cohort, who were regularly treated by a rheumatologist, with more than one-third of patients receiving current or past DMARDs (32.1%), biologics (35.8%), or NSAIDs (35.8%), which may have helped control disease activity. The small sample size of patients who completed the BASDAI questionnaire (81 patients) may also not reflect the general population of patients with AS. Further studies should be performed with more robust samples; and the use of additional PRO measures specific to AS, such as BASFI or HAQ-S, may be beneficial to assess AS-related functional status, as they are more or just as sensitive to detect change in disease activity as with BASDAI.11,50,51

LIMITATIONS

Although this study provides valuable insights into the HCRU and health care costs associated with AS, this study is subject to the general limitations of real-world observational studies. The findings presented here may not be representative of all patients with AS, since patients were predominantly female and White and were recruited to volunteer to participate during visits to rheumatology clinics, which could represent an active role among patients in disease management that may not be indicative of the general population of patients with AS. Study data were obtained solely via questionnaires that were based on patient recall. Consequently, the responses presented here may be affected by recall bias, and health care costs may be underestimated if some costs were inaccurately attributed to comorbid conditions. Our study also assumed that PRO scores would be stable over the 6-month period during which the HCRU and total health care cost data were accrued, which may not accurately represent the progression of functional status for the general population of patients with AS. Furthermore, health care costs presented in this study were estimated based on the Medicare fee schedule for services recorded in the registry and were not observed directly. Pharmacy cost information was based on wholesale acquisition cost and does not incorporate any price reductions due to rebates. Additionally, the sample size of patients with AS who completed only a BASDAI questionnaire was small, and the mean BASDAI score was relatively low in our population compared with that of other similar studies. Additional studies with larger patient populations that include patients with more varied BASDAI scores should be conducted to corroborate the association between this PRO measure and HCRU and total health care costs. Finally, the HAQ-DI was used to assess function and disability. This measure is uncommonly used in AS and the BASFI is generally used instead; however, the BASFI was not available in this dataset. The modified version, HAQ-S, accounts for activities and/or disabilities as a result of spine involvement.52-54 This measure is strongly correlated with the HAQ-DI, suggesting the HAQ-DI alone is suitable to account for disability in AS.

Conclusions

There was a significant direct relationship between functional disability and HCRU and health care costs demonstrated in this cohort, which is consistent with previous studies. A significant increase in the risk of hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, and diagnostic testing was significantly associated with HAQ-DI score. Additionally, for every 1.0-unit increase in HAQ-DI, total health care costs, medical costs, and pharmacy costs significantly increased. The results presented provide further evidence of the economic burden and increased resource use experienced by patients with more severe physical disability associated with AS, which substantiates the need for earlier and more stable disease control to improve the overall quality of life and burden seen with this disease. Therapies for the treatment of AS that can effectively improve functional impairment may reduce costs for patients and the health care system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the participating providers and patients for contributing data to FORWARD. Medical writing support was provided by Charli Dominguez, PhD, CMPP, of Health Interactions, Inc, and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. This manuscript was developed in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines. Authors had full control of the content and made the final decision on all aspects of this publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baraliakos X, Listing J, Rudwaleit M, et al. Progression of radiographic damage in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: Defining the central role of syndesmophytes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):910-5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenker KJ, Quint JM. Ankylosing spondylitis. StatPearls. Preprint posted online August 4, 2021. Accessed October 26, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470173/

- 3.El Maghraoui A. Extra-articular manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis: Prevalence, characteristics and therapeutic implications. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(6):554-60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brophy S, Pavy S, Lewis P, et al. Inflammatory eye, skin, and bowel disease in spondyloarthritis: Genetic, phenotypic, and environmental factors. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(12):2667-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strand V, Rao SA, Shillington AC, Cifaldi MA, McGuire M, Ruderman EM. Prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis in United States rheumatology practices: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society criteria versus rheumatology expert clinical diagnosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(8):1299-306. doi: 10.1002/acr.21994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldtkeller E, Khan MA, van der Heijde D, van der Linden S, Braun J. Age at disease onset and diagnosis delay in HLA-B27 negative vs. positive patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23(2):61-6. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0237-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boonen A, van der Linden SM. The burden of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2006;78:4-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis JC, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Woolley JM. Reductions in health-related quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and improvements with etanercept therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(4):494-501. doi: 10.1002/art.21330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotsis K, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA, Carvalho AF, Hyphantis T. Health-related quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A comprehensive review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14(6):857-72. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.957679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkham N, Kong KO, Tennant A, et al. The unmet need for anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44(10):1277-81. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zochling J. Measures of symptoms and disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Scale (ASQoL), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Global Score (BAS-G), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), Dougados Functional Index (DFI), and Health Assessment Questionnaire for the Spondylarthropathies (HAQ-S). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63 Suppl 11: S47-58. doi: 10.1002/acr.20575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis JC, Jr., Revicki D, van der Heijde DM, et al. Health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis treated with adalimumab: Results from a randomized controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(6):1050-7. doi: 10.1002/art.22887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marzo-Ortega H, Sieper J, Kivitz A, et al. Secukinumab and sustained improvement in signs and symptoms of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis through two years: Results from a phase III study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(7):1020-9. doi: 10.1002/acr.23233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(12):2286-91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S14-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krabbe S, Glintborg B, Ostergaard M, Hetland ML. Extremely poor patient-reported outcomes are associated with lack of clinical response and decreased retention rate of tumour necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2019;48(2):128-32. doi: 10.1080/03009742.2018.1481225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramiro S, van der Heijde D, van Tubergen A, et al. Higher disease activity leads to more structural damage in the spine in ankylosing spondylitis: 12-year longitudinal data from the OASIS cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(8):1455-61. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, Sieper J. Prediction of a major clinical response (BASDAI 50) to tumour necrosis factor alpha blockers in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(6):665-70. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.016386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss A, Song IH, Haibel H, Listing J, Sieper J. Good correlation between changes in objective and subjective signs of inflammation in patients with short-but not long duration of axial spondyloarthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor-blockers. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(1):R35. doi: 10.1186/ar4464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O, et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1243-52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottlieb AB, Langley RG, Philipp S, et al. Secukinumab improves physical function in subjects with plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Results from two randomized, phase 3 trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(8):821-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells AF, Edwards CJ, Kivitz AJ, et al. Apremilast monotherapy in DMARD-naive psoriatic arthritis patients: Results of the randomized, placebo-controlled PALACE 4 trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(7):1253-63. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deodhar AA, Dougados M, Baeten DL, et al. Effect of secukinumab on patient-reported outcomes in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: A phase III randomized trial (MEASURE 1). Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(12):2901-10. doi: 10.1002/art.39805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(2):582-91. doi: 10.1002/art.20852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baraliakos X, Braun J, Deodhar A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of secukinumab 150 mg in ankylosing spondylitis: 5-year results from the phase III MEASURE 1 extension study. RMD Open. 2019;5(2):e001005. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inman RD, Davis JC Jr, van der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of golimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(11): 3402-12. doi: 10.1002/art.23969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landewe R, Braun J, Deodhar A, et al. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms of axial spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis: 24-week results of a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled Phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):39-47. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Krueger GG, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and the association with clinical response in patients with active psoriatic arthritis treated with golimumab: Findings through 2 years of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(10):1666-73. doi: 10.1002/acr.22044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McInnes IB, Puig L, Gottlieb AB, et al. Association between enthesitis and health-related quality of life in psoriatic arthritis in biologic-naive patients from 2 phase III ustekinumab trials. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(11):1458-61. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajima A, Aoki Y, Terayama K, et al. Health assessment questionnaire-disability index (HAQ-DI) score at the start of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) therapy is associated with radiographic progression of large joint damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27(6):967-72. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2017.1294302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenberg JD, Palmer JB, Li Y, Herrera V, Tsang Y, Liao M. Healthcare resource use and direct costs in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis in a large US cohort. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(1):88-96. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howe A, Eyck LT, Dufour R, Shah N, Harrison DJ. Treatment patterns and annual drug costs of biologic therapies across indications from the Humana commercial database. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(12):1236-44. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.12.1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh JA, Song X, Kim G, Park Y. Healthcare utilization and direct costs in patients with ankylosing spondylitis using a large US administrative claims database. Rheumatol Ther. 2018;5(2): 463-74. doi: 10.1007/s40744-018-0124-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reveille JD, Ximenes A, Ward MM. Economic considerations of the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343(5):371-4. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182514093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yi E, Dai D, Piao OW, Zheng JZ, Park Y. Health care utilization and cost associated with switching biologics within the first year of biologic treatment initiation among patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(1):27-36. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2020.19433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooksey R, Husain MJ, Brophy S, et al. The cost of ankylosing spondylitis in the UK using linked routine and patient-reported survey data. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0126105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Heijde DM, Revicki DA, Gooch KL, et al. Physical function, disease activity, and health-related quality-of-life outcomes after 3 years of adalimumab treatment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(4):R124. doi: 10.1186/ar2790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rafia R, Ara R, Packham J, Haywood KL, Healey E. Healthcare costs and productivity losses directly attributable to ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(2):246-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boonen A, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, et al. Direct costs of ankylosing spondylitis and its determinants: An analysis among three European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(8):732-40. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.8.732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobelt G, Andlin-Sobocki P, Maksymowych WP. Costs and quality of life of patients with ankylosing spondylitis in Canada. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(2):289-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michaud K, Wolfe F. Comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(5):885-906. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.PROMIS. Obtain & administer measures. Health Measures. 2021. Accessed June 10, 2020; https//www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=71&Itemid=817

- 43.Wolfe F, Michaud K. The National Data Bank for rheumatic diseases: A multiregistry rheumatic disease data bank. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(1):16-24. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang JH, Chen YH, Lin HC. Comorbidity profiles among patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A nationwide population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1165-8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.116178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenbaum J, Chandran V. Management of comorbidities in ankylosing spondylitis. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343(5):364-6. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182514059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walsh JA, Adejoro O, Chastek B, Park Y. Treatment patterns of biologics in US patients with ankylosing spondylitis: Descriptive analyses from a claims database. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(4):369-80. doi: 10.2217/cer-2017-0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JS, Oh BL, Lee HY, Song YW, Lee EY. Comorbidity, disability, and healthcare expenditure of ankylosing spondylitis in Korea: A population-based study. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward MM. Functional disability predicts total costs in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(1):223-31. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu TY, Tam LS, Lee VW, Hwang WW, Li TK, Lee KK, et al. Costs and quality of life of patients with ankylosing spondylitis in Hong Kong. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(9):1422-5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Dawes PT. Patient-assessed health in ankylosing spondylitis: A structured review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44(5):577-86. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruof J, Sangha O, Stucki G. Comparative responsiveness of 3 functional indices in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(9):1959-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chakravarty SD, Abell J, Leone-Perkins M, Orbai AM. A novel qualitative study assessing patient-reported outcome measures among people living with psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;8(1): 609-20. doi: 10.1007/s40744-021-00289-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Daltroy LH, Larson MG, Roberts NW, Liang MH. A modification of the Health Assessment Questionnaire for the spondyloarthropathies. J Rheumatol. 1990;17(7):946-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ogdie A, Blachley T, Lakin PR, et al. Evaluation of clinical diagnosis of axial psoriatic arthritis (PsA) or elevated patient-reported spine pain in CorEvitas’ PsA/Spondyloarthritis registry. J Rheumatol. 2022;49(3)281-90. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.210662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]