Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Given relapse frequency early in the course of schizophrenia, recently diagnosed patients may benefit from longacting injectable antipsychotics, which are associated with reduced risk of relapse and hospitalization compared with oral antipsychotics (OAPs).

OBJECTIVE:

To compare health care resource utilization (HCRU) and costs in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia treated with continuous paliperidone palmitate (PP) or continuous OAP or who switched from OAP to PP.

METHODS:

In this analysis, we combined the 2 randomized phases of the prospective, open-label Disease Recovery Evaluation and Modification (DREaM) clinical study using the principal stratification method to generate 3 treatment strategies: continuous PP for 18 months (PP-PP), continuous OAP for 18 months (OAP-OAP), and initial OAP switched to PP after 9 months (OAP-PP). HCRU metrics included psychiatric hospitalizations, psychiatric and nonpsychiatric emergency department visits, and ambulatory visits. Costs were analyzed using generalized linear models with inverse-probability weighting based on time-varying probabilities of exposure. Robust SEs were estimated using individual-level clustered bootstrapping. Subgroup analyses were performed by region and prior antipsychotic use (< 6 vs ≥ 6 months).

RESULTS:

A total of 181 patients were included in the PP-PP (n = 61), OAP-OAP (n = 61), and OAP-PP (n = 59) groups. The majority of patients (73%) were enrolled at study sites in the United States, and 48% had received an antipsychotic for less than 6 months prior to study entry. Baseline characteristics were well balanced, and no significant differences in discontinuation rates were observed across treatment strategies. Compared with OAP-OAP, significantly lower cumulative HCRU and costs were apparent before 9 months in the PP-PP group and after 9 months in the OAP-PP group. The cumulative 18-month effects of PP-PP and OAP-PP vs OAP-OAP on the number of psychiatric hospitalizations were ‒0.28 (95% CI = ‒0.51 to ‒0.08) and ‒0.27 (95% CI = ‒0.50 to 0.04), respectively, and those on cumulative mean per-patient total health care costs (in 2020 USD) were −$2,867 (95% CI = ‒$5,133 to ‒$750) and ‒$2,789 (95% CI = ‒$5,155 to ‒$701), respectively. Subgroup analyses indicated a greater reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations and costs with PP-PP or OAP-PP relative to OAP-OAP in patients with less than 6 vs 6 or more months of prior antipsychotic therapy.

CONCLUSIONS:

Continuous early use of PP in adults with recentonset schizophrenia significantly reduced psychiatric hospitalizations and associated estimated costs compared with OAP; these effects were particularly notable for patients with a shorter duration of prior antipsychotic use. As this was a post hoc analysis of a study that was not powered for HCRU assessments, future studies calibrating these effects to larger real-world populations will be useful.

Plain language summary

Patients with a recent diagnosis of schizophrenia often have symptoms return, also known as relapse. Severe symptoms may require a hospital stay. Paliperidone palmitate is a medication for schizophrenia that patients take every 1, 3, or 6 months. In this study, patients treated with paliperidone palmitate for 9 or 18 months were less likely to have a psychiatric hospital stay than patients who took other daily medication.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

This analysis shows that the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in patients recently diagnosed with schizophrenia can reduce the risk for psychiatric hospitalizations, thus lowering associated health care costs, in comparison with the standard of care, daily oral antipsychotics.

The clinical course of schizophrenia involves periods of relative quiescence punctuated by episodes of increased symptom presence and severity. Such relapses may be severe and require hospital admission to achieve symptom control.1 The consequences of relapse are myriad, including risk of self-harm, interference with daily life and relationships, loss of function, and disease progression.2,3 At the healthsystem level, relapse generates a considerable health care resource utilization (HCRU) and cost burden, most notably in the form of hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits.4-6 The economic ramifications of schizophrenia are especially pronounced for recently diagnosed patients, a group that is more likely to experience repeated hospitalizations and ED visits and have a longer hospital length of stay relative to patients with established disease.7 Although there are data demonstrating that use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) delay time to first hospitalization in patients with early-phase disease,8 there is comparatively little information available regarding the influence of LAI vs oral antipsychotic (OAP) use on HCRU and costs in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia.

The Disease Recovery Evaluation and Modification (DREaM; NCT02431702) study was a prospective, openlabel, multicenter, doubly randomized, matched-control study designed to compare the effectiveness of paliperidone palmitate (PP) vs OAP in delaying time to first treatment failure in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder.9 Patients were initially randomized to treatment with either PP or OAP. After 9 months of treatment, patients randomized to PP continued PP and patients randomized to OAP were rerandomized to treatment with PP or OAP for an additional 9 months. No statistically significant differences between groups were observed for the primary outcome, time to first treatment failure, defined as psychiatric hospitalization due to worsening symptoms, suicidal or homicidal ideation or behavior requiring immediate intervention, new arrest or incarceration, discontinuation of antipsychotic treatment owing to inadequate efficacy, discontinuation of antipsychotic treatment owing to safety/tolerability, increase in level of psychiatric services to prevent imminent psychiatric hospitalization, or treatment supplementation with another antipsychotic owing to inadequate efficacy. However, when treatment supplementation with another antipsychotic was removed from the definition of treatment failure (an analysis that was informed by the recognition that supplementation as a means of dose adjustment for LAI is not considered a treatment failure by many clinicians), significant differences were observed in the proportion of patients who experienced treatment failure during the second 9 months of treatment in the continuous PP for 18 months (PP-PP), continuous OAP for 18 months (OAP-OAP), and initial OAP followed by a switch to PP after 9 months (OAP-PP) treatment groups (treatment failure rates, 4.1%, 14.0%, and 27.0%, respectively; P = 0.002).

In this analysis, we combined the 2 randomized phases of the DREaM study using the principal stratification method10 to generate 3 treatment strategies: PP-PP, OAP-OAP, and OAP-PP. The goals of this analysis were to compare cumulative HCRU and associated health care costs over 18 months by treatment strategy and to evaluate whether region or treatment history influenced HCRU and costs in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

Details of the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the DREaM study have been previously described.9 Briefly, the study enrolled adult men and women aged 18-35 years who had a current diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder and a first psychotic episode within the past 24 months. Patients were excluded if they met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition criteria for a moderate or severe substance use disorder (with the exception of nicotine) within 2 months of screening. The present analysis only included patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, as that is the US Food and Drug Administration-approved indication for 1-month or 3-month PP extended-release injectable suspension (Invega Sustenna and Invega Trinza, respectively; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc).11,12 All study participants provided written informed consent.

STUDY DESIGN

Patients who met study inclusion criteria entered a 2-month, oral therapy run-in period, during which they received oral paliperidone extended-release or oral risperidone. After the run-in period, patients were randomized 1:2 to treatment with long-acting PP (1-month PP for a minimum of 4 months, then transitioned to 3-month PP) or OAP (investigator choice of 7 protocol-approved OAPs) for 9 months. Patients who completed the initial 9-month treatment phase were eligible for the next treatment phase, during which those who were receiving PP continued with PP and those receiving OAP were rerandomized 1:1 to PP or to continue OAP for an additional 9 months.

For the purposes of our analysis, we grouped patients by the 3 possible mutually exclusive treatment strategies: (1) PP-PP—comprising patients who were assigned to PP for both 9-month treatment periods; (2) OAP-OAP—comprising patients who were assigned to OAP for both 9-month treatment periods; and (3) OAP-PP—comprising patients who were assigned to OAP for the first 9 months and switched to PP for the second 9 months. Patients initially randomized to PP who discontinued during the first 9 months of treatment were included in the PP-PP analysis population. In this way, we are replicating an intention-to-treat approach, in which some patients assigned to PP would drop out before 9 months and others would continue to receive PP through 18 months. Patients initially randomized to OAP who discontinued during the first 9 months of treatment were randomly assigned to the OAP-OAP or OAP-PP treatment group for the purposes of the analysis, to achieve a similar intention-to-treat approach. Random allocation ensured that the experiences before discontinuation were similar for the 2 strategies during the first 9 months.

The DREaM study protocol was approved by institutional review boards at each site, and the study was performed in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and in compliance with federal and state research and privacy laws.

ASSESSMENTS AND OUTCOMES

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder diagnosis, duration of substance abuse, duration of antipsychotic use, and country of residence, were collected during the run-in period.

Measures of HCRU, including psychiatric hospitalizations, psychiatric ED visits, nonpsychiatric ED visits, psychiatric day visits, nonpsychiatric day visits, and outpatient visits, were measured from the start of treatment through study discontinuation, loss to follow-up, or the end of the study (18 months postbaseline). The following composite visit metrics were also assessed: total outpatient care visits, which comprised psychiatric day, nonpsychiatric day, and outpatient visits; total ED visits, which comprised psychiatric and nonpsychiatric ED visits; and total care visits, which comprised total ED visits and total outpatient care visits.

STATISTICAL METHODS

We modeled the total counts for accumulated HCRU in 3-month intervals (ie, at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months) using a generalized linear model with negative binomial distribution and log link function to adjust for the nonlinear distribution of these count data. Treatment strategy indicators and time intervals were covariates in the model. To account for differences in duration of assessment due to patient discontinuation or loss to follow-up, we applied time-varying inverse-probability weighting.13-15 Censoring probabilities were estimated by modeling time-varying discontinuation/completion times across treatment assignment groups over the 18 months as a function of baseline characteristics. Similar analyses were repeated for each type of HCRU. We report the incremental total use over an 18-month period.

SEs for both the levels of use for a treatment group and the increment effects across treatment groups were obtained using 1,000 individual-level clustered bootstrap replicates to capture the covariance across different HCRU types and for the same kind of HCRU over time within individuals.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were similar between patients randomized to PP or OAP, and, by default, across PP-PP, OAP-OAP, and OAP-PP groups based on how we constructed these cohorts using principal stratification; therefore, our main analyses did not adjust for any baseline characteristics. The robustness of our main results with regard to potential imbalances in baseline characteristics was assessed through sensitivity analyses using propensity score weighting based on baseline factors. We further explored the heterogeneity of the comparative effects across important subgroups, including enrollment at a US site and baseline duration of antipsychotics use (< 6 months vs > 6 months).

Costs were calculated by weighting HCRU estimates from our previous analyses with US-based population-level unit costs for each of the utilization measures. All costs are expressed in 2020 dollars. Unit costs are presented in Supplementary Table 1 (1.9MB, pdf) (available in online article).

To understand the time trajectory of any cumulative effects of a strategy on HCRU and costs, the generalized linear models were repeated with an interaction of strategy and time interval indicators. Incremental time trajectories of each type of HCRU between the 3 groups are presented. The SEs for these incremental effects were obtained via clustered bootstrap analysis. Stata 16.1 was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 181 adults with recent-onset schizophrenia were included in the PP-PP (n = 61), OAP-OAP (n = 61), and OAP-PP (n = 59) treatment strategy groups (Figure 1). Taking into account the random allocation to the OAP-OAP and OAP-PP analysis groups for patients who discontinued OAP during the initial treatment phase, discontinuation rates over the 18-month treatment period were 50.8% (PP-PP), 39.3% (OAP-OAP), and 40.6% (OAP-PP; Supplementary Table 2 (1.9MB, pdf) ). The difference in discontinuation rates across strategies did not reach statistical significance. Compared with OAP-OAP, the hazard ratios for discontinuation in the PP-PP and OAP-PP groups were 1.24 (95% CI = 0.67‒2.31; P = 0.49) and 1.17 (95% CI = 0.62‒2.22; P = 0.63), respectively (Supplementary Figure 1 (1.9MB, pdf) ). We discuss the implications of this result in the Discussion section. The mean and median durations of followup across all arms were 395 and 505 days, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Patient Disposition

Baseline and disease characteristics were qualitatively similar across treatment strategies (Table 1). The mean age was 23 years, and the patient population was predominantly male (76% to 82%). A large proportion of the population was Black (35% to 40%), and approximately one-third of patients were Hispanic/Latino. The majority of patients (72% to 74%) were enrolled from study sites in the United States. Nearly half of the population had received an antipsychotic for less than 6 months prior to study entry. Baseline and disease characteristics for patients with schizophrenia were consistent with the overall study population (Supplementary Table 3 (1.9MB, pdf) ).

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics | PP-PP (n = 61) | OAP-OAP (n = 61) | OAP-PP (n = 59) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at randomization, years a | 23.6 (4.7) | 22.6 (3.9) | 24.5 (5.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 50 (82) | 47 (77) | 45 (76) |

| Female | 11 (18) | 14 (23) | 14 (24) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 31 (50) | 25 (41) | 27 (45) |

| Black | 21 (35) | 24 (39) | 24 (40) |

| Other | 9 (15) | 12 (20) | 9 (15) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, n (%) | 23 (37) | 20 (32) | 20 (34) |

| Duration of substance use, n (%) | |||

| ≤ 2 years | 12 (19) | 13 (22) | 9 (16) |

| > 2 years | 24 (40) | 24 (39) | 18 (31) |

| Missing | 25 (41) | 24 (39) | 31 (52) |

| Duration of antipsychotic use, n (%) | |||

| < 6 months | 27 (45) | 28 (46) | 30 (52) |

| 6-12 months | 13 (22) | 15 (25) | 11 (18) |

| > 12 months | 17 (28) | 15 (25) | 14 (24) |

| Missing | 2 (4) | 3 (5) | 4 (7) |

| Country, n (%) | |||

| United States | 44 (72) | 45 (74) | 42 (72) |

| Brazil | 12 (20) | 10 (17) | 12 (21) |

| Mexico | 5 (8) | 6 (10) | 4 (7) |

| Run-in period duration, days a | 57 (1.9) | 58.4 (5.0) | 57.6 (2.8) |

| HCRU during the 12 months prior to study entry a | |||

| Psychiatric hospitalization | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.01 (0.11) |

| Psychiatric ED visits | 0 (0) | 0.04 (0.28) | 0 (0) |

| Other ED visits | 0.08 (0.45) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.05 (0.22) |

| Psychiatric day treatments | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.01 (0.11) |

| Other day treatments | 0 (0) | 0.02 (0.14) | 0 (0) |

| Total outpatient visits | 0.25 (0.44) | 0.35 (0.48) | 0.33 (0.47) |

a Data are means (SDs).

ED = emergency department; HCRU = health care resource utilization; OAP = oral antipsychotic;

PP = paliperidone palmitate.

HCRU

During the 18-month treatment period, the proportion of patients with any psychiatric hospitalization was 21% for the OAP-OAP group and 7% for each of the OAP-PP and PP-PP groups. The average number of psychiatric hospitalizations per patient in the OAP-OAP group was 0.36 (SE = 0.10). Using this group as the reference, the average numbers of psychiatric hospitalizations for patients in the OAP-PP and PP-PP groups were lower by 0.27 (95% CI = ‒0.50 to ‒0.04) and 0.28 (95% CI = ‒0.51 and ‒0.08), respectively (Figure 2). There were no significant differences between groups in any other HCRU metrics for the overall population (Supplementary Table 4 (1.9MB, pdf) ).

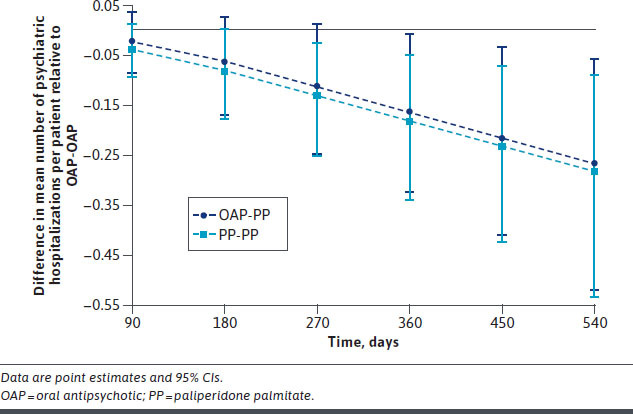

Figure 2.

Cumulative Effects of Treatment Strategies on Health Care Resource Utilization

HCRU in the subgroup of patients enrolled in the United States was consistent with the overall population (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4 (1.9MB, pdf) ). However, the magnitude of reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations with PP-PP or OAP-PP relative to OAP-OAP was greater for patients with less than 6 vs 6 or more months of prior antipsychotic therapy (Figure 2). There was also a trend toward a reduction in ED visits for the PP-PP strategy compared with OAP-OAP in patients with 6 or more months of prior antipsychotic therapy.

Analyses of HCRU over time revealed that PP-PP produced a significant reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations compared with OAP-OAP in the first 9 months of treatment, as indicated by a 95% CI upper bound on cumulative effects being below 0 by day 270 (Figure 3). The OAP-PP strategy achieved a significant reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations after the first 9 months of treatment (ie, after the transition to PP). Differences between groups were not significant over time for other HCRU measures (Supplementary Figure 2 (1.9MB, pdf) ). Similar results were obtained after adjusting for baseline characteristics (Supplementary Table 5 (1.9MB, pdf) ).

Figure 3.

Projected Cumulative Effect on Psychiatric Hospitalizations of Treatment Strategies Involving PP Compared With Continuous OAP Treatment at Specific Time Intervals

The difference in psychiatric hospitalizations for patients enrolled in the United States was apparent for PP-PP vs OAP-OAP by day 180 (Supplementary Figure 3 (1.9MB, pdf) ). For patients with less than 6 months of prior antipsychotic use, the reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations with PP-PP and OAP-PP vs OAP-OAP was significant by day 360; statistical significance was not achieved in the subgroup with 6 or more months of prior antipsychotic use (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5 (1.9MB, pdf) ). No other significant differences were observed in subgroup analyses.

HEALTH CARE COSTS

Compared with OAP-OAP, PP-PP and OAP-PP decreased total health care costs by $2,867 (95% CI = ‒$5,133 to ‒$750) and $2,789 (95% CI = ‒$5,155 to ‒$701) per patient, respectively (Table 2). These cost savings were primarily driven by decreases in psychiatric hospitalizations (Supplementary Table 6 (1.9MB, pdf) ). Significant cost reductions with PP-PP and OAP-PP relative to OAP-OAP were also observed in the subgroups of patients enrolled in the United States and patients with less than 6 months of prior antipsychotic use (Table 2). Cost savings did not reach statistical significance for patients with 6 or more months of prior antipsychotic use.

Table 2.

Cumulative Effects of Alternate Strategies on Associated Health Care Costs (in 2020 US Dollars) Over 18 Months

| Subgroup | Health care costs by treatment strategy, mean (SE) a | Comparison of health care costs, mean difference (95% CI) a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost category | PP-PP | OAP-OAP | OAP-PP | PP-PP (ref: OAP-OAP) | OAP-PP (ref: OAP-OAP) |

| All patients | (n = 61) | (n = 61) | (n = 59) | ||

| Psychiatric hospitalizations | 716 (347) | 3,480 (1,014) | 862 (471) | ‒2,765 (‒5,025 to ‒782) | ‒2,619 (‒4,852 to ‒412) |

| Totalb | 1,669 (418) | 4,536 (1,014) | 1,747 (498) | ‒2,867 (‒5,133 to ‒750) | ‒2,789 (‒5,115 to ‒701) |

| Patients enrolled in United States | (n = 44) | (n = 45) | (n = 42) | ||

| Psychiatric hospitalizations | 498 (347) | 4,222 (1,333) | 1,160 (622) | ‒3,724 (‒6,598 to ‒1,243) | ‒3,062 (‒6,180 to ‒382) |

| Totalb | 1,552 (481) | 5,454 (1,331) | 2,266 (642) | ‒3,903 (‒6,881 to ‒1,235) | ‒3,189 (‒6,338 to ‒648) |

| Patients with < 6 months of prior antipsychotic use | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | (n = 30) | ||

| Psychiatric hospitalizations | 1,210 (885) | 5,097 (2,222) | 543 (491) | ‒3,887 (‒9,283 to ‒241) | ‒4,554 (‒10,027 to ‒1,216) |

| Totalb | 2,347 (1,108) | 5,758 (2,240) | 1,423 (572) | ‒3,411 (‒9,043 to ‒841) | ‒4,335 (‒9,915 to ‒941) |

| Patients with ≥ 6 months of prior antipsychotic use | (n = 30) | (n = 30) | (n = 29) | ||

| Psychiatric hospitalizations | 266 (313) | 2,172 (1,250) | 1,196 (866) | ‒1,907 (‒4,973 to 254) | ‒976 (‒4,137 to 2,119) |

| Totalb | 1,402 (499) | 2,833 (1,249) | 2,075 (906) | ‒1,430 (‒4,605 to 959) | ‒758 (‒3,916 to 2,342) |

Bold indicates that 95% CI does not include zero.

aData are presented as the per-patient mean in 2020 United States dollars.

b Total costs represents all costs associated with psychiatric hospitalizations, psychiatric and nonpsychiatric emergency department visits, psychiatric and nonpsychiatric day clinic visits, and all outpatient visits.

OAP = oral antipsychotic; PP = paliperidone palmitate; ref = reference.

Trends in the effect on health care costs over time followed a similar pattern to that of psychiatric hospitalization, with PP-PP showing a significant decrease in cumulative average health care costs by the first 9 months, whereas OAP-PP only achieved such savings after the first 9 months (ie, after the transition to PP; Supplementary Figure 6 (1.9MB, pdf) ).

Discussion

In this evaluation of patients with recent-onset schizophrenia, we used an innovative approach to analyze data from the DREaM study in order to compare different antipsychotic use strategies. Specifically, within the 2-stage randomization design of the DREaM study, patients initially randomized to PP who discontinued during the first 9 months of treatment were included in the PP-PP analysis population. Patients initially randomized to OAP who discontinued during the first 9 months of treatment were randomly assigned to the OAP-OAP or OAP-PP treatment group for the purposes of the analysis. Random allocation ensured that the experiences before discontinuation were similar for the 2 strategies during the first 9 months. We found that the use of PP conferred reductions in HCRU and costs compared with OAP over an 18-month treatment period. The greatest benefit was observed for patients who were initially randomized to PP (ie, the PP-PP cohort), although patients who switched from OAP to PP after 9 months (ie, the OAP-PP cohort) also experienced fewer psychiatric hospitalizations and lower associated costs than patients who received OAP throughout. Reductions were notable in the subgroups of patients enrolled at study sites in the United States and patients with a shorter duration (< 6 months) of antipsychotic use prior to study entry.

A reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations with PP vs OAP is consistent with data from the Paliperidone Palmitate Research in Demonstrating Effectiveness (PRIDE) clinical trial, wherein patients with schizophrenia and a history of incarceration were randomized to treatment with once-monthly PP or daily OAP for 15 months.16 Psychiatric hospitalizations were reported for 8.0% of patients who received PP and 11.9% of patients who received OAP,16 which corresponded to an average of 0.13 fewer psychiatric hospitalizations per patient in the PP treatment group over the course of the study.17 Compared with the DREaM study, the PRIDE patient population was older (mean age, 38 years) and had a longer duration of illness (> 80% of patients with a duration of > 5 years).16 Data for the comparison of PP and OAP in patients with a more recent diagnosis of schizophrenia (within 1-5 years) are available from the Prevention of Relapse with Oral Antipsychotics versus Injectable Paliperidone Palmitate (PROSIPAL) clinical trial.18 Results from PROSIPAL demonstrated that treatment with PP in patients experiencing an acute episode of schizophrenia and who had a history of 2 or more relapses requiring psychiatric hospitalization within the past 24 months significantly lengthened the time to relapse, an endpoint that included psychiatric hospitalizations, compared with OAP. Whereas the PROSIPAL data represent the experiences for patients with a more recent diagnosis compared with PRIDE, the mean time from diagnosis (3 years) suggests that this study population is less representative of the recentonset schizophrenia experience than DREaM.

Given the elevated risk for relapse and hospitalization early in the course of schizophrenia,7 the recent-onset patient experience may differ from that of patients with a longer disease history. Clinical studies have demonstrated a reduction in hospitalization with LAI vs usual therapy/OAP in patients with early-phase/recent-onset disease.8,19 In the Prevention of Relapse in Schizophrenia (PRELAPSE) study, patients with less than 5 years of lifetime antipsychotic use were randomized to treatment with an LAI or usual care (predominantly OAP) for up to 24 months.8 Forty-six percent of the study population had less than 1 year of prior antipsychotic therapy. Treatment with an LAI delayed time to first hospitalization and reduced the incidence of hospitalization by 44% compared with OAP. In a comparatively small study of patients who had a first major episode of schizophrenia within the prior 2 years, psychiatric hospitalizations were required in significantly fewer patients treated with an LAI (5.0%) vs an OAP (18.6%) during the 12-month treatment period.19 These data combined with the results of the DREaM study support the use of LAI to reduce the risk of psychiatric hospitalization in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia. Moreover, we did not find any evidence that use of LAI significantly reduced outpatient visits, indicating that patient engagement was not hampered.

An intriguing finding from our analysis was the observation that between-group comparisons for HCRU metrics and costs differed between patients with less than 6 vs 6 or more months of prior antipsychotic use. The data suggest that earlier treatment with PP has the potential to yield the greatest protection against need for psychiatric hospitalization in patients with recent-onset disease. However, there was a trend toward a reduction in ED visits in patients with 6 or more months of prior antipsychotic use in the PP-PP group vs the OAP-OAP group that was not observed for those with less than 6 months of prior antipsychotic use. These findings warrant further investigation.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations that influence the interpretation these analyses. First, DREaM was not powered to detect difference in HCRU metrics and associated health care costs. Hence, when comparing HCRU and costs, we are likely to incur a high rate of type 2 errors while keeping the type 1 error rate fixed. That is, we are less likely to identify significant effects on HCRU when there is an actual effect than a larger study designed with HCRU and costs as the main outcome measures. Second, the cost analysis did not include pharmacy costs, as would be available in a real-world dataset rather than a clinical trial. Third, as with trials of this nature, loss to follow-up and discontinuation are all considered to be censoring events. Although not statistically significant, the PP-PP arm showed a higher rate of discontinuation. Qualitatively analyzing the “other” reasons for discontinuation revealed that one of the reasons for a somewhat higher rate of withdrawal of consent among patients who received PP was that more patients receiving PP vs OAP felt that their symptoms were relieved to the extent that they no longer needed to continue their treatment. Lastly, the DREaM study did not collect data on OAP adherence; therefore, we were unable to assess whether the effects on HCRU were related to differences in adherence between the treatment strategies.

Conclusions

The results of our analysis support the potential benefit of initiating treatment with PP early in the course of schizophrenia, a crucial point in the disease course and yet a period when clinicians are reluctant to consider treatment with LAIs. Patients who received PP experienced significant reductions in psychiatric hospitalizations and associated costs compared with OAP, with the greatest benefit in patients initially randomized to PP and those with a less-than-6-month prior history of antipsychotic use. Notably, the cumulative cost savings from the reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations continued to increase over the 18-month study period. Future studies are needed to validate the potential impact on HCRU of early LAI use in real-world populations and determine the cost-effectiveness of such a treatment strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support, funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, was provided by Crystal Murcia, PhD, of Inkwell Medical Communications LLC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jorgensen KT, Bog M, Kabra M, Simonsen J, Adair M, Jonsson L. Predicting time to relapse in patients with schizophrenia according to patients’ relapse history: A historical cohort study using real-world data in Sweden. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):634. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03634-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane JM. Treatment strategies to prevent relapse and encourage remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68 Suppl 14:27-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, Harvey BH. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong J, Windmeijer F, Novick D, Haro JM, Brown J. The cost of relapse in patients with schizophrenia in the European SOHO (Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes) study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(5):835-41. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, et al. The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lafeuille MH, Gravel J, Lefebvre P, et al. Patterns of relapse and associated cost burden in schizophrenia patients receiving atypical antipsychotics. J Med Econ. 2013;16(11):1290-9. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.841705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicholl D, Akhras KS, Diels J, Schadrack J. Burden of schizophrenia in recently diagnosed patients: Healthcare utilisation and cost perspective. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(4):943-55. doi: 10.1185/03007991003658956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. Effect of long-acting injectable antipsychotics vs usual care on time to first hospitalization in early-phase schizophrenia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1217-24. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alphs L, Brown B, Turkoz I, Baker P, Fu DJ, Nuechterlein KH. The Disease Recovery Evaluation and Modification (DREaM) study: Effectiveness of paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in patients with recentonset schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder. Schizophr Res. 2022;243:86-97. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2022.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frangakis CE, Rubin DB. Principal stratification in causal inference. Biometrics. 2002;58(1):21-9. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00021.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Invega Sustenna (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use. Prescribing information. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Invega Trinza (palperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use. Prescribing information. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bang H, Tsiatis AA. Estimating medical costs with censored data. Biometrika. 2000;87(2):329-43. doi: 10.1093/biomet/87.2.329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Y. Cost analysis with censored data. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S115-9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819bc08a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao H, Cheng Y, Bang H. Some insight on censored cost estimators. Stat Med. 2011;30(19):2381-8. doi: 10.1002/sim.4295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alphs L, Benson C, Cheshire-Kinney K, et al. Real-world outcomes of paliperidone palmitate compared to daily oral antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia: A randomized, open-label, review board-blinded 15-month study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):554-61. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muser E, Kozma CM, Benson CJ, et al. Cost effectiveness of paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia and a history of criminal justice involvement. J Med Econ. 2015;18(8):637-45. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2015.1037307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreiner A, Aadamsoo K, Altamura AC, et al. Paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in recently diagnosed schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;169 (1-3):393-9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]