Abstract

Two new ecdysteroids, spectasterone A (1) and spectasterone B (2), together with four known ecdysteroids, breviflorasterone (3), ajugalactone (4), 20-hydroxyecdysone (5), and polypodine B (6) were isolated from the Korean endemic plant Ajuga spectabilis using feature-based molecular networking analysis. The chemical structures of 1 and 2 were determined based on the interpretation of NMR and mass spectrometric data. Their absolute configurations were established using 3JH, H coupling constants, NOESY interactions, Mosher’s method, and ECD and DP4+ calculations. To identify their biological target, a machine learning-based prediction system was applied, and the results indicated that ecdysteroids may have 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1)-related activity, which was further supported by molecular docking results of ecdysteroids with 11β-HSD1. Following this result, all the isolated ecdysteroids were tested for their ability to affect the expression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) in HaCaT cells irradiated with UVB. Compounds 2–5 exhibited inhibition of 11β-HSD1 expression and increases in GR activity.

1. Introduction

The genus Ajuga belongs to the Lamiaceae family and consists of more than 300 species that produce diverse secondary metabolites. In particular, Ajuga species are known as rich sources of ecdysteroids.1 Ecdysteroids are characteristically polyhydroxylated and generally possess a 14α-hydroxy-7-en-6-one chromophoric moiety. As the most representative ecdysteroid, 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E) has attracted the interest of the pharmaceutical and medicinal industry because of its beneficial pharmacological activities, such as anabolic, hypolipidemic, antidiabetic, antifibrotic, anti-inflammatory, and nontoxic effects.2Achyranthes japonica (A. japonica) extract, which is known to contain 20E as a major compound, inhibited inflammation and articular cartilage degradation in monosodium iodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis in rats.3 As a consequence of this result, A. japonica is being developed as a new functional supplement for improving joint health.

The perennial herb Ajuga spectabilis (A. spectabilis) is a species endemic to Korea. It is found mainly in the alpine regions of Korea, including the Sobaek, Baegyang, Naejang, Gaya, Daeryong, and Gongjak mountains.4 To date, phytochemical and biological studies of this plant have been limited to three investigations. Chemical investigations of A. spectabilis led to the isolation of one iridoid glycoside (jaranidoside)5 and one flavonoid glycoside (luteolin 5-glucoside).6 Biological studies of A. spectabilis extract and luteolin 5-glucoside revealed antitumor and neuroprotective effects.6

To continue the search for new bioactive compounds from A. spectabilis, ecdysteroids were targeted and isolated utilizing a feature-based molecular networking (FBMN) approach with ion identity networking. Target-specific ensemble ECBS (TS-ensECBS) analysis predicted that ecdysteroids have the potential to bind 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1). Glucocorticoids (GC) are known as anti-inflammatory drugs, which suppress proinflammatory regulators such as nuclear factor-κB or activator protein 1 by activating the glucocorticoid receptors (GRs).7 11β-HSD1 converts inactive glucocorticoids (GC) to active GC, and this is responsible for delayed wound healing. 11β-HSD1 is detected in epidermal keratinocytes, dermal fibroblasts, sebocytes, and sweat gland cells in the skin, and its expression is increased by chronological aging and photoaging. It has been proposed that inhibition of 11β-HSD1 is of potential therapeutic benefit to skin aging.8

Herein, we report on the molecular networking, isolation, structure elucidation, and biological evaluation of two new ecdysteroids (1–2) together with four known ecdysteroids (3–6) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of ecdysteroids 1–6.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Phytochemical Investigation

The 70% EtOH extract of A. spectabilis was partitioned sequentially with n-hexane, n-butanol, and water. The mass spectrum data of MS2 acquisition in the n-butanol fraction were collected using QE Orbitrap MS, and the MS2 data obtained were analyzed using GNPS to calculate the FBMN (Figure S1).9,10 De novo molecular formula annotation and structure elucidation using a deep neural network, SIRIUS, were used to identify the molecular formula of the query compound of both previously observed and unobserved.11 Additionally, compound classes were predicted using CANOPUS.12 The nodes in the FBMN were directly connected by MS1 annotation in ion identification networking and cosine in MS2. In the compound classes, “organooxygen compounds (26%)” and “steroids and steroid derivatives (26%)” were the most common followed by “prenol lipids (15.7%)”, “carboxylic acid and derivatives (11.6%)”, and “flavonoids (5.4%)”. Five networks included in the top four classes (excluding “organooxygen compounds”) were selected in order of the highest MS1 intensity. Using GNPS and SIRIUS, eight known compounds were identified in networks 1, 2, and 3 (Figures S2–S4). An unknown compound (compound 2) with the same molecular formula (calculated for C29H44O8, 520.3036) and predicted structure as cyasteron but with a different retention time (tR of cyasteron: 12.58 and tR of compound 2: 13.65) was found in network 4. An unknown compound (compound 1) with no nodes connected to known compounds was found in independent network 5. Using ZODIAC and CSI:FingerID,13,14 the molecular formula of the predicted structure (compound 1) was calculated as C27H44O9 (512.2985). From the predicted structure obtained from CANOPUS and SIRIUS, the class of the compound was identified as “steroids and steroid derivatives”. As a result of molecular networking analysis, compounds 1 and 2 were targeted for isolation because of their potential as new metabolites (Figure 2). Guided by the LC–MS analysis, two new ecdysteroids (1–2) were obtained using repeated liquid column chromatography.

Figure 2.

Molecular network of the n-butanol fraction from A. spectabilis; cluster corresponding to compounds 1 (b) and 2 (a) of unknown ecdysteroids.

2.2. Structural Characterization

Compound 1 was isolated as a white amorphous powder. The molecular formula of 1 was determined to be C27H44O9 using HRESIMS at m/z 513.3063 [M + H]+ (calculated for C27H45O9, 513.3058). The 1H NMR data (Table 1) displayed resonances for four oxygenated methines at δH 4.53 (1H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H-11), 4.16 (1H, ddd, J = 3.1, 4.6, 12.1 Hz, H-2), 3.96 (1H, br q, J = 3.1 Hz, H-3), and 3.31 (1H, overlapped on the methanol-d4 solvent peak, H-22); four aliphatic methines at δH 2.95 (1H, t, J = 9.5 Hz, H-17), 2.54 (2H, overlapped, H-8 and H-9), and 1.58 (1H, m, H-25); three tertiary methyls at δH 1.29 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.14 (3H, s, H3-21), and 1.07 (3H, s, H3-19); two secondary methyls at δH 0.94 (3H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H3-26) and 0.93 (3H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H3-27); and seven methylenes in the range δH 2.70–1.22. The 13C NMR data (Table 1) showed 27 carbon resonances, which, supported by the HSQC data, were attributed to two ketones (δC 213.7 and 212.9); eight methines, including four oxygenated methines (δC 78.2, 73.4, 70.9, and 68.5) and four aliphatics (δC 49.6, 44.8, 40.3, and 29.3); seven methylenes (δC 38.7, 37.7, 37.3, 36.3, 32.7, 30.6, and 21.5); five methyls (δC 23.5, 22.8, 21.0, 18.4, and 17.7); and five nonprotonated carbons (δC 89.0, 82.8, 77.2, 62.2, and 48.1). The HMBC and 1H–1H COSY correlations were extensively utilized to complete the NMR assignments for the ecdysteroid skeleton (Figure 3). Key HMBC cross-peaks from H3-19 to C-5 (δC 82.8), H3-18 to C-14 (δC 89.0), and H3-21 to C-20 (δC 77.2) and C-22 (δC 78.2) confirmed the locations of the four hydroxy groups at C-5, C-14, C-20, and C-22. The remaining three hydroxy functionalities were connected to C-2, C-3, and C-11 based on the 1H–1H COSY correlations, H2-1/H-2/H-3/H2-4 and H-11/H-9/H-8/H2-7. Additionally, two ketones substituted at the C-6 and C-12 positions were deduced from the HMBC cross-peaks of H3-18/C-12 (δC 213.7) and H2-7 (δH 2.69, 2.22)/C-6 (δC 212.9). The COSY spin system, H-22/H2-23/H2-24/H-25/H3-26/H3-27, and the HMBC correlations of the side chain protons H-22 to C-17 (δC 44.8) unambiguously confirmed that the 2,6-methylheptane-2,3-diol side chain was attached to C-17. In all naturally arising ecdysteroids, the A/B ring junction is generally cis and hardly ever trans, whereas the B/C and C/D ring junctions are always trans.(15) In the NOESY spectrum of 1 (Figure 3), the strong correlations between H-2/H-9 supported a cis A/B ring junction. The α-configurations of H-2 and H-3 could be confirmed by the large and small coupling constants (3JH-1β/H-2 = 12.1 Hz and 3JH-2/H-3 = 3.1 Hz), respectively. The β-orientation of H-11 was established by the NOESY correlations between H-11/H3-19. Furthermore, the β-configuration of H3-18 was supported by the NOESY correlations between H-11/H3-18. The NOESY cross-peaks between H-17/H-15α and between H3-21/H3-18 confirmed that the H-17 should be α-oriented and the configuration of C-20 was R. To clarify the stereochemistry of C-20, the aprotic solvent was employed. A set of additional NOESY cross-peaks between 20-OH (δH 4.86, s)/H-16β (δH 2.54, m) was present in pyridine-d5 (Table S1). Additionally, we used the DP4+ probability to determine the configuration of 1 at C-20. The calculated 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts of the two possible diastereomers, 1a (20R) and 1b (20S), were compared with the experimental values of 1 by utilizing DP4+ probability analysis, which predicted that the configuration 20R was the most probable, 100% at the B3LYP/6-31G+(d,p) level (Figure S17). The absolute configuration of the secondary hydroxy moiety at C-22 was deduced using Mosher’s method. A comprehensive analysis of the 1H NMR resonances of the R- and S-MTPA ester derivatives of 1 revealed a systematic distribution of ΔδS–R values, which established a 22R configuration (Figure 4). From the above results, the structure of 1 was established as a new ecdysteroid and named spectasterone A.

Table 1. 1H and 13C NMR Data of Compounds 1 and 2 in Methanol-d4.

|

1 |

2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | δH mult. (J in Hz) | δC | δH mult. (J in Hz) | δC | |

| 1α | 2.32, dd (13.6, 4.6) | 36.3 | 1.79a | 37.4 | |

| 1β | 1.74a | 1.43, dd (12.2, 13.6) | |||

| 2 | 4.16, ddd (3.1, 4.6, 12.1) | 68.5 | 3.84, ddd (3.3, 4.7, 12.2) | 68.7 | |

| 3 | 3.96, br q (3.1) | 70.9 | 3.95, q (3.3) | 68.5 | |

| 4α | 2.30, dd (13.1, 4.2) | 37.3 | 1.70a | 32.9 | |

| 4β | 1.77a | ||||

| 5 | 82.8 | 2.39a | 51.8 | ||

| 6 | 212.9 | 206.4 | |||

| 7α | 2.69, t (13.3) | 38.7 | 5.82, d (2.6) | 122.3 | |

| 7β | 2.22, dd (3.1, 13.3) | ||||

| 8 | 2.54a | 40.3 | 167.6 | ||

| 9 | 2.54a | 49.6 | 3.16, dd (2.6, 7.1) | 35.1 | |

| 10 | 48.1 | 39.3 | |||

| 11α | 1.70a | 21.6 | |||

| 11β | 4.53, d (8.1) | 73.4 | 1.84a | ||

| 12α | 213.7 | 2.16, td (13.1, 4.8) | 32.5 | ||

| 12β | 1.92, m | ||||

| 13 | 62.2 | 48.7 | |||

| 14 | 89.0 | 85.2 | |||

| 15α | 1.79, m | 32.7 | 1.60, m | 31.9 | |

| 15β | 1.54, m | 2.01a | |||

| 16α | 1.74a | 21.5 | 1.70a | 21.6 | |

| 16β | 2.04, m | 2.01a | |||

| 17 | 2.95, t (9.5) | 44.8 | 2.39a | 51.1 | |

| 18 | 1.29, s | 17.7 | 0.91, s | 18.0 | |

| 19 | 1.07, s | 18.4 | 0.97, s | 24.4 | |

| 20 | 77.2 | 78.1 | |||

| 21 | 1.14, s | 21.0 | 1.31a | 22.6 | |

| 22 | 3.31a | 78.2 | 3.51, s | 73.3 | |

| 23 | 1.67, m | 30.6 | 4.81, d (7.7) | 81.5 | |

| 1.33, m | |||||

| 24 | 1.48, m | 37.7 | 2.71a | 43.8 | |

| 1.24, m | |||||

| 25 | 1.58, m | 29.3 | 2.71a | 38.1 | |

| 26 | 0.94, d (2.4) | 23.5 | 183.8 | ||

| 27 | 0.93, d (2.4) | 22.8 | 1.60a | 19.7 | |

| 28 | 1.02, t (7.3) | 13.5 | |||

| 29 | 1.31a | 11.8 | |||

Overlapped signals; chemical shifts were determined from HSQC cross-peaks.

Figure 3.

Key HMBC, COSY, and NOESY correlations of compounds 1 and 2.

Figure 4.

ΔδS–R values for the Mosher’s ester derivatives of compound 1.

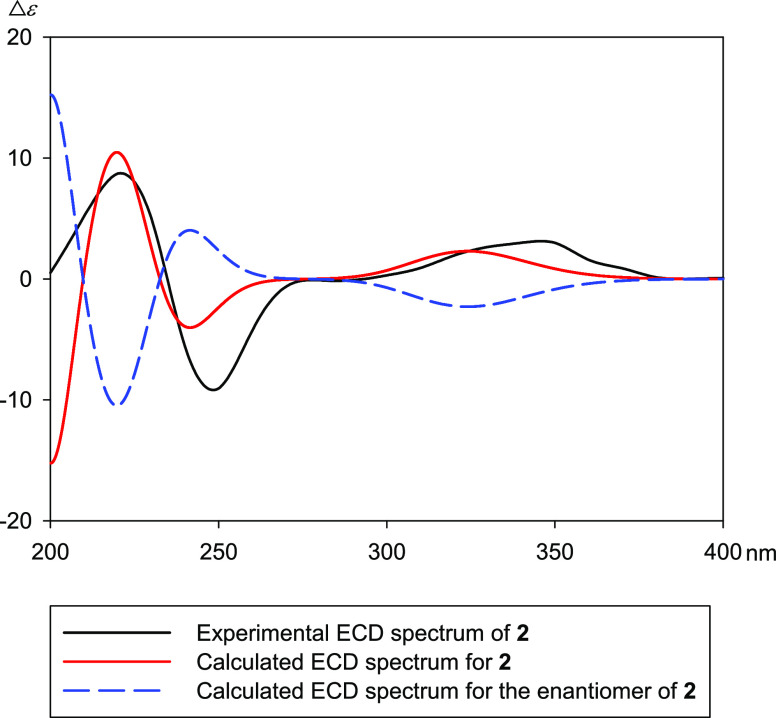

Compound 2 was isolated as a white amorphous powder. The molecular formula of 2 was determined to be C27H44O9 using HRESIMS at m/z 521.3107 [M + H]+ (calculated for C29H45O8, 521.3109). The 1D NMR spectroscopic data of 2 were similar to those of breviflorasterone (3). The differences were the 1H and 13C chemical shifts of the lactone ring, indicating that 2 could be a diastereomer of 3. The NOESY cross-peaks and coupling constants (3JH-1β/H-2 = 12.2 Hz and 3JH-2/H-3 = 3.3 Hz) confirmed a cis A/B ring junction and α-configurations of H-2 and H-3. The NOESY correlations of H-11β with H3-19 and H3-18 indicated β-orientations. Furthermore, the α-orientation of H-17 was established by the NOESY cross-peaks between H-17/H-12α. The configuration of C-20 was assigned as R by the NOESY correlations between H3-21/H3-18 and H3-21/H-12β. The configuration of C-22 was also determined as R by the NOESY cross-peaks between H-22/H-16α and H-22/H-16β. Conformational search calculations provided the lowest energy conformer, for which the geometry was optimized using the DFT method. This structure supported all the NOESY cross-peaks. The coupling constant of H-22/H-23 (3JH-22/H-23 = 0 Hz) suggested a torsion angle of H-22/H-23 of about 90° according to the Karplus equation (two possible configurations, Figure 5). To clarify the structure of 2, the aprotic solvent pyridine-d5 was employed (Table S1). There was no NOESY correlation between 22-OH/H-23, suggesting that 2 corresponded to the 22R,23S model. The probability of this correlation is very high because the distance between 22-OH/H-23 was very small in the 22R,23R model. The NOESY cross-peaks between H-17/H-23 also supported a 23S. In addition, the large coupling constant of H-23/H-24 (3JH-23/H-24 = 8.6 Hz) indicated an anti-orientation, and irradiation of H-23 at δH 4.92 correlated with the signal at δH 2.71 (H-25) in the 1D NOE experiment (Figure S30), suggesting that H-23 and H-25 were on the same face of the molecule. The absolute configuration of 2 was determined using an ECD experiment. As shown in Figure 6, the calculated ECD curve of 2 (red) matched well with the experimental ECD spectrum for 2 (black). From the above results, the structure of 2 was established as a new ecdysteroid and was named spectasterone B.

Figure 5.

Newman projections of the two possible configurations at C-23 with key NOESY interactions illustrated for C-23S.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the experimental and calculated ECD spectra of 2.

Additionally, through comparison of the obtained spectroscopic data with those reported in the literature, four known ecdysteroids (3–6) were identified: breviflorasterone (3),16 ajugalactone (4),17 hydroxyecdysone (5),18 and polypodine B (6).18

2.3. Evolutionary Chemical Binding Similarity (ECBS) Application and Molecular Docking of the Isolated Compounds

To investigate the biological uses of these isolated compounds, ecdysteroids were applied to the ECBS model. ECBS is a machine learning model that represents chemical similarity in terms of target-binding properties. Of the 7690 targets, those with high scores were considered potential binding target candidates. In particular, 11β-HSD1 was selected for subsequent experimental validation via a comprehensive consideration of the biological roles of the ecdysteroids and their binding score with the molecular target. In addition, the molecular dockings of all ecdysteroids 1–6 into 11β-HSD1 were carried out to indirectly check the feasibility of our inference. Ecdysteroids 2–5 showed better affinities (−3.1 to −3.6 kcal/mol) with 11β-HSD1 in comparison with ecdysteroids 1 and 6 (−2.2 and −2.5 kcal/mol) (Figure 7). Structural analysis with these results showed that ecdysteroids 2–5 have in common the absence of the hydroxy group at C-5. Based on these predictions, we checked whether these compounds affect the expression of 11β-HSD1. Furthermore, GR activities of these compounds were also tested due to the deep biological correlation with 11β-HSD1.

Figure 7.

Binding models of ecdysteroids 2–5 in 11β-HSD1 (UniProt P28845; PDB 2BEL). The molecule in red represents the ligand molecule. The light green circles represent the residues that form van der Waal’s interactions, the dark green represents the residues that form hydrogen bonds, and the pink represents the residues that form hydrophobic (alkyl/π–alkyl) interactions.

2.4. Biological Evaluation

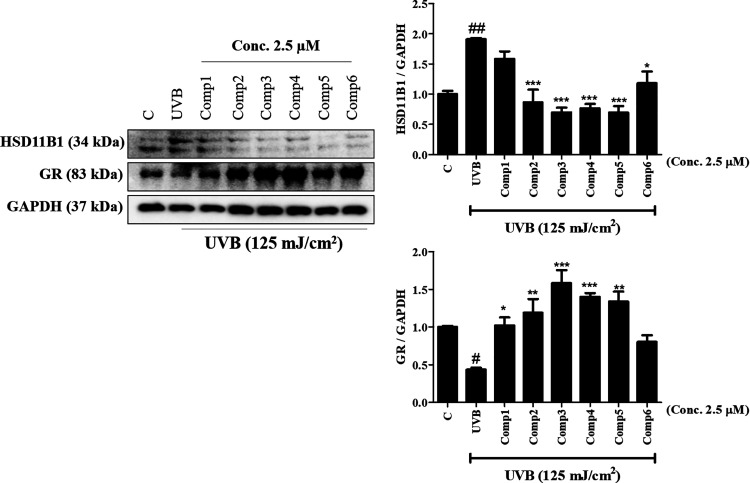

UVB is capable of increasing the inflammatory process in the skin and contributes to several types of skin damage (dermal atrophy, telangiectasia, fragility, and poor wound healing).19 Glucocorticoids (GCs) are well-known as steroid hormones that regulate multiple elements including the suppression of skin damage.20 Furthermore, it has been reported that the activity of 11β-HSD1 to reduce GR expression contributes to the regulation of cutaneous responses to UVB.20 They appear to represent novel targets for the identification of skin-antiaging agents, which correlate with the skin photoaging process. In our work, UVB irrigation increased the level of 11β-HSD1 (##p < 0.01), but the expressed level of GRs (#p < 0.05) was reversed (Figure 8). Ecdysteroids 2–5 inhibited the protein level of 11β-HSD1 (***p < 0.001) in UVB-induced HaCaT cells, indicating that this new compound may be a potential skin-antiaging agent. In addition, ecdysteroids 2–5 recovered the expressed levels of GRs (**p < 0.01).

Figure 8.

Effect of ecdysteroids on UVB-induced 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1) and glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) in HaCaT keratinocyte cells. Cells were treated with ecdysteroids at 2.5 μM concentrations for 2 h, and then, HaCaT cells were irradiated with UVB (125 mJ/cm2). 11β-HSD1 and GRs were quantified in the UVB-induced group with HaCaT cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs control group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 vs the UVB-induced group.

3. Conclusions

In general, ecdysteroids are known as arthropod steroid hormones that are responsible for the regulation of molting, development, and reproduction. However, plants also produce ecdysteroids for protection against phytophagous insects and synthesize these molecules in higher quantities (4–5%) than insects.1 To date, more than 500 ecdysteroids have been reported in over 100 terrestrial plants. Of these, 20-hydroxyecdysone, ajugasterone C, and polypodine B are the most commonly found. In particular, 20-hydroxyecdysone exhibits an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting the activation of NF-κB,21 and ajugasterone C demonstrates antimicrobial activity against multiresistant strains.22Ajuga species belonging to Lamiaceae are rich sources of ecdysteroids.1 In this study, we described the ecdysteroids from the aerial parts of Ajuga spectabilis, which is a species endemic to Korea. Previous phytochemical studies of this plant have been limited to the isolation of iridoid glycosides and flavonoid glycosides. Our study is the first to report the presence of ecdysteroids in A. spectabilis. A new ecdysteroid (spectasterone B; 2) is a diastereomer of breviflorasterone (3). They differ from each other in two stereogenic centers at C-23 and C-24. Based on careful consideration of the biological roles of ecdysteroids and binding scores with molecular targets in the ECBS model and molecular docking study, all ecdysteroids 1–6 were tested for their capacity to express 11β-HSD1 and GRs in HaCaT cells irradiated with UVB. Compounds 2–5 not only inhibited 11β-HSD1 but also increased GR expression. Compared with no-activity ecdysteroids (1 and 6), these ecdysteroids (2–5) lacked the hydroxy group in position C-5. These results indicated that a substituted proton at C-5 in ecdysteroids had activities on 11β-HSD1 and GRs. This is the first report to evaluate the effects of ecdysteroids on the expression of 11β-HSD1 and GRs. In addition, our results provide a rationale for the further development of ecdysteroids 2–5 as therapeutic candidates for new antiaging agents.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured on a Jasco P-2000 polarimeter (Tokyo, Japan). UV spectra were obtained using a Mecasys Optizen POP (Daejeon, Republic of Korea). Infrared spectra were obtained using an Agilent Cary 630 FTIR (Santa Clara, CA, USA). NMR spectra were obtained using a Varian (Palo Alto, CA, USA) or Bruker (Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) 500 MHz spectrometer, with chemical shifts referenced to solvent peaks. The ECD spectrum was recorded utilizing an Applied Photophysics Chirascan V100 spectrometer (Leatherhead, Surrey, UK). Flash column chromatography was performed using YMC reversed-phase silica gel (ODS-A 12 nm S-150 μm, Tokyo, Japan). Preparative (prep) and semipreparative (semiprep) HPLC was performed using a YMC LC-Forte/R system and a Gilson purification system (Middleton, WI, USA) together with a YMC Pack ODS-A column (250 × 20.0 mm, 5.0 μm), a Phenomenex Luna C18(2) column (250 × 21.2 mm, 10.0 μm, Torrance, CA, USA), a Phenomenex Luna C18(2) column (250 × 10.0 mm, 10.0 μm), a Phenomenex Luna C8(2) column (250 × 21.2 mm, 10.0 μm), and a Phenomenex Luna C8(2) column (250 × 10.0 mm, 10.0 μm).

4.2. Plant Material

Whole plants of A. spectabilis were collected in May 2020 from Geoje-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea. The collected plant material was authenticated by Taek Joo Lee (Hantaek Botanical Garden). A voucher specimen (HTS2020-00001) was deposited at the Herbarium of Hantaek Botanical Garden, Yongin, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea.

4.3. Extraction and Isolation

The dried whole plant of A. spectabilis (305.9 g) was extracted using 70% EtOH (3 L, 7 days) at room temperature. The filtrates were concentrated using a rotary evaporator to obtain 45.5 g of crude extract. This extract was suspended in distilled water (200 mL) and partitioned sequentially with n-hexane (2 × 200 mL) and n-butanol (2 × 200 mL). A portion (5.3 g) of the n-butanol fraction (20.7 g) was subjected to flash C18 column separation, and six fractions (BPAS00003-1 to BPAS00003-6) were obtained via stepwise gradient elution using 600 mL of methanol/water (20:80, 40:60, 50:50, 60:40, 70:30, and 100:0). BPAS00003-3 (933.1 mg) was isolated using prep HPLC (7 mL/min, a gradient of acetonitrile:water from 20:80 to 30:70 over 60 min) with a C18 column (Phenomenex, 250 × 21.2 mm, 10 μm) to obtain nine fractions (BPAS00003-3-1 to BPAS00003-3-9). BPAS00003-3-4 (541.2 mg) was separated using prep HPLC (10 mL/min, with the isocratic flow of 30% methanol for 100 min) with a C8 column (Phenomenex, 250 × 21.2 mm, 10.0 μm) to yield 6 (10.9 mg, tR of 83.6 min) and 5 (36.7 mg, tR of 95.0 min). BPAS00003-3-8 (20.5 mg) was purified using semiprep HPLC (3 mL/min, a gradient of acetonitrile:water from 20:80 to 25:75 over 60 min) with a C18 column (Phenomenex, 250 × 10.0 mm, 10 μm) to obtain 1 (3.3 mg, tR 43.0 min) and BPAS00003-3-8-2. BPAS00003-3-8-2 (10.7 mg) was further purified using semiprep HPLC (3 mL/min, a gradient of acetonitrile:water from 20:80 to 25:75 over 60 min) with a C8 column (Phenomenex, 250 × 10.0 mm, 10 μm) to obtain 2 (5.3 mg, tR of 33.0 min). BPAS00003-3-9 (17.7 mg) was purified using semiprep HPLC (3 mL/min, a gradient of acetonitrile:water from 20:80 to 25:75 over 60 min) with a C18 column (Phenomenex, 250 × 10.0 mm, 10 μm) to obtain 4 (8.0 mg, tR of 38.4 min). BPAS00003-4 (129.8 mg) was isolated using prep HPLC (3 mL/min, a gradient of acetonitrile:water from 20:80 to 50:50 over 60 min) with a C18 column (Phenomenex, 250 × 21.2 mm, 10.0 μm), to obtain 10 fractions (BPAS00003-4-1 to BPAS00003-4-10). BPAS00003-4-6 (10.0 mg) was purified using semiprep HPLC (3 mL/min, a gradient of acetonitrile:water from 20:80 to 25:75 over 60 min) with a C8 column (Phenomenex, 250 × 10 mm, 10.0 μm) to obtain 3 (4.7 mg; tR of 47.2 min).

4.3.1. Spectasterone A (1)

White powder; [α]20D +4.0 (c 0.03, acetonitrile); UV (acetonitrile) λmax: 210 (4.00); IR (KBr) νmax cm–1: 3420, 2953, 1709, 1631, 1317, 1086; 1H and 13C NMR, see Table 1 and Table S1; (+)-HRESIMS m/z 513.3063 [M + H]+ (calculated for C27H45O9, 513.3058).

4.3.2. Spectasterone B (2)

White powder; [α]20D +15.0 (c 0.1, acetonitrile); UV (acetonitrile) λmax: 240 (4.13); IR (KBr) νmax cm–1: 3420, 2924, 1747, 1650, 1384, 1055; ECD (c 0.096 mM, acetonitrile): Δε +8.9 (222), −9.2 (248), +3.3 (336); 1H and 13C NMR, see Table 1 and Table S1; (+)-HRESIMS m/z 521.3107 [M + H]+ (calculated for C29H45O8, 521.3109).

4.4. Preparation of the S- and R-MTPA Ester Derivatives of Compound 1

A quantity of 0.5 mg of compound 1 was dissolved in 500 μL of pyridine-d5. To initiate the reaction, 12 μL of R-MTPA-Cl was added with careful stirring and then monitored every 30 min by measuring the 1H NMR spectrum. The mixture was allowed to react for 2 h at 30 °C and then quenched with the addition of a few drops of methanol. The solvents were removed under a vacuum to provide a white solid. The solid was purified using semiprep HPLC (3 mL/min, a gradient of acetonitrile:water from 30:70 to 100:0 over 60 min) with a C18 column (Phenomenex Luna 250 × 10.0 mm, 10 μm) to obtain the S-MTPA ester derivative. Compound 1 was reacted in an analogous manner using 12 μL of S-MTPACl to provide the R-MTPA ester derivative.

4.4.1. S-MTPA Ester of Compound 1

1H NMR (500 MHz, pyridine-d5): δH 6.11 (1H, m, H-2), 5.62 (1H, m, H-22), 5.57 (1H, overlapped, 3-OH), 2.64 (1H, m, H2-1), 2.48 (1H, m, H2-1), 1.83 (1H, m, H-23), 1.79 (3H, s, H3-21), 1.63 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.32 (1H, m, H-25), 0.74 (6H, overlapped, H3-26 and H3-27).

4.4.2. R-MTPA Ester of Compound 1

1H NMR (500 MHz, pyridine-d5): δH 6.06 (1H, m, H-2), 5.62 (1H, m, H-22), 5.49 (1H, overlapped, 3-OH), 2.76 (1H, m, H2-1), 2.55 (1H, m, H2-1), 1.81 (3H, s, H3-21), 1.67 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.66 (1H, m, H-23), 1.20 (1H, m, H-25), 0.68 (3H, d, H3-26), 0.63 (3H, d, H3-27).

4.5. Computational Analysis

Computational analysis was performed with reference to the literature.23 Conformational analysis was conducted using Spartan′14 software (Wavefunction, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) under the molecular mechanics force field. The conformers with a cumulative Boltzmann distribution cutoff of 0.95 were examined using Gaussian 09 software (Wallingford, CT, USA). The calculations for their geometry optimization were carried out at the density functional theory (DFT) B3LYP/6-31G+(d,p) level. ECD calculation was performed based on time-dependent DFT CAM-B3LYP/SVP with a CPCM solvent model (acetonitrile) using Gaussian 09 software. The calculated ECD spectra were simulated with a half-bandwidth of 0.3 eV. The ECD curves were extracted using SpecDis 1.71 software. After geometry optimization, the gauge-including atomic orbital shielding constants were calculated at the B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p) level in a methanol solvent model using Gaussian 09. The experimental and calculated data were analyzed using the DP4+ probability method previously mentioned.24

4.6. UHPLC-Q Exactive Orbitrap MS

Chromatographic separation was achieved using a Thermo Vanquish UHPLC system (Waltham, MA, USA) with a Phenomenex Luna Omega Polar C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.6 μm, 100 Å). The mobile phase was composed of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both with 0.1% formic acid. The total flow rate and column temperature were set at 0.3 mL/min and 40 °C, respectively. The gradient program of the mobile phase was set initially at 5% B for 1 min, increased to 40% B for 14 min, further increased to 100% B for 1 min, and then held at 100% B for 3 min before being decreased to the initial 5% B, and this was followed by a 3 min re-equilibration period. Thermo Q Exactive (QE) Orbitrap mass spectrometry (Waltham, MA, USA) was utilized with a heated electrospray ionization (H-ESI II) probe in the full scan and MS/ddMS2 modes. The scan range of the full scan mode was set at 400 to 1100 m/z. The resolutions of the full scan and ddMS2 modes were set at 70,000 and 17,500, respectively. Automatic gain control and maximum injection time were set at 1e6 and 100 ms in the full scan mode and at 5e4 and 50 ms in ddMS2 mode, respectively. In the ddMS2 mode setting, the TopN (N, the number of topmost abundant ions for fragmentation) was set to 10. The normalized collision energy was set to 30% (average value of collision energy of 15, 30, and 45%), and the isolation window was set at 1.6 m/z. For the H-ESI II probe setting in the positive ion mode, the capillary temperature and auxiliary gas heater temperature were set at 300 and 400 °C, respectively. The sheath gas and auxiliary gas flow rates were set at 41 and 11, respectively, and the S-lens rf level was 50.

4.7. MS Data Preprocessing and Molecular Networking Analysis

The MS data were preprocessed using the MZmine3 program. The MS1 and MS2 noise levels were 1E4 and 3E3, respectively. An ADAP chromatogram was built with a minimum group size of 4 scans, a scan-to-scan accuracy of 10 ppm, and a minimum feature height of 5E4. The Savitzky–Golay smoothing algorithm was used with a retention time smoothing of 5. Chromatographic deconvolution was calculated as a local minimum feature resolver with a chromatographic threshold of 90%, a minimum ratio of peak top/edge of 1.8, and a peak duration ranging from 0 to 1.51. The 13C isotope filter was calculated with an m/z tolerance of 3 ppm, a retention time tolerance of 0.05 min, and a maximum charge of 2. An isotopic peak filter was performed with chemical elements of H, C, N, O, and S, an m/z tolerance of 3 ppm, and a maximum charge of isotope m/z of 1. Metacorrelation was calculated using a Pearson correlation of 70% and a retention time tolerance of 0.055. Ion identity networking was obtained via [M + H]+, [M + Na]+, [M + NH4]+, and [M + 2H]2+ included with modifications of [M-H2O] and [M-2H2O]. Preprocessed MS data were submitted to FBMN on the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) website. In addition, SIRIUS was used as a tool to obtain structural information about known and unknown compounds in preprocessed MS data. The SIRIUS tool includes molecular formula identification, ZODIAC (for network-based improvement of SIRIUS molecular formula ranking), CSI:FingerID (for fingerprint prediction and structure database search), and CANOPUS (for compound class prediction). The FBMN was visualized using Cytoscape.

4.8. Prediction of Chemical Binding Targets

The ECBS model was applied to predict potential binding targets of chemical compounds and to infer target-associated chemical activity.25 As in our previous study, of the ECBS model variants, we used the target-specific ensemble ECBS (TS-ensECBS) models prebuilt for a total of 7690 targets.26 The large-scale predictions of the TS-ensECBS models enabled the estimation of a comprehensive target-binding profile for a given chemical compound; targets were scored using the maximum chemical binding similarity value to the previously known active molecules for the target. The target scores were then used to select potential binding targets for the subsequent experimental validation.

4.9. Molecular Docking

The PDB structure for the 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 (11β-HSD1) (UniProt ID P28845) was taken from the RCSB (PDB ID 2BEL). The structure had 4 copies of a single unique chain and a ligand attached to it. The unique chain was isolated, and all the ligands and cofactors attached to it were removed. This protein chain was used as the receptor file for the molecular docking experiment. Molecular docking of the protein–ligand complexes was performed with the help of AutoDock (version 1.5.7). The receptor and ligand molecules were converted to .pdbqt format, which is recognized by the AutoDock tools. Polar hydrogen atoms, Kollman charges (for a receptor), and Gasteiger charges (for a ligand) were added to prepare the receptor and ligand for docking. The grid box was positioned based on binding site information of the original ligand bound in the crystal structure of 2BEL. The atom-specific affinity maps for all ligand atom types and electrostatic and desolvation potentials were computed with the help of Autogrid (version 4.2.6). The docking simulation for every protein–ligand pair consisted of 100 iterations following genetic algorithm methods. The energy evaluations were performed using the Lamarckian genetic algorithm local search method in AutoDock (version 4.2.6). All the other parameters like the number of generations, the maximum number of top individuals to survive to the next generation, the mutation rate, and the crossover rate were set to their default value. The total minimum energy resulting from the 100 docking runs was used as the binding energy for analysis.

4.10. Biological Activity

The biological activities of samples isolated from the Korean endemic plant A. spectabilis were evaluated as described in our previous study with minor modifications.27 HaCaT cells (Korean Cell Line Bank, Seoul, Republic of Korea) were seeded into 60 mm plates (1 × 106 cells/well) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium including 5% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Samples at a 2.5 μM concentration were treated in the wells for 2 h and then exposed to UVB at 125 mJ/cm2 using a UV lamp. After UVB irradiation, the cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS (1×), and lysed in PRO-PREP (iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc., Sungnam, Republic of Korea). Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) obtained from the lysed cells were loaded onto 10% SDS gels and then transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The transferred membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (1:1000) including GRs (Cell Signaling, MA, USA), 11β-HSD1 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and α-tubulin (Cell Signaling). After 1 day, the attached primary antibody membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:2000) for 2 h. All membranes were analyzed using a ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The detected band intensity was calculated using Bio-Rad Quantity One software (ver. 4.3.0, Bio-Rad).

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Program (2E32641).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.3c02421.

Network of feather-based molecular networking of the n-BuOH fraction; HRESIMS, IR, UV, 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR data of 1–2; computational data (PDF)

Author Contributions

# I.P. and K.P. contributed equally to this work. The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Arif Y.; Singh P.; Bajguz A.; Hayat S. Phytoecdysteroids: distribution, structural diversity, biosynthesis, activity, and crosstalk with phytohormones. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8664–8696. 10.3390/ijms23158664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan L.; Dioh W.; Veillet S.; Lafont R. 20-Hydroxyecdysone, from plant extracts to clinical use: therapeutic potential for the treatment of neuromuscular, cardio-metabolic and respiratory diseases. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 492–524. 10.3390/biomedicines9050492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. S.; Lee H. S.; Yu H.-J.; Jang S. H.; Seo Y.; Cho H. Y.; Choe S. Y. Effect of fermented Achyranthes japonica (Miq.) Nakai extract on osteoarthritis. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 49, 104–109. 10.9721/KJFST.2017.49.1.104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. W. A distribution of Ajuga spectabilis Nakai (Labiatae) of Korean endemic plant. Korean J. Pl. Taxon. 1992, 22, 47–49. 10.11110/kjpt.1992.22.1.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung B.-S.; Lee H.-K.; Kim J.-W. Iridoid glycoside (I) -studies on the iridoid glycoside of Ajuga spectabilis Nakai. Korean J. Pharmacogn. 1980, 11, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Woo K. W.; Sim M. O.; Kim A. H.; Kang B. M.; Jung H. K.; An B.; Cho J. H.; Cho H. W. Quantitative analysis of luteolin 5-glucoside in Ajuga spectabilis and their neuroprotective effects. Korean J. Pharmacogn. 2016, 47, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata M.; Lee J. Y.; Susuki-Miyata S.; Wang W. Y.; Xu H.; Kai H.; Kobayashi K. S.; Flavell R. A.; Li J. D. Glucocorticoids suppress inflammation via the upregulation of negative regulator IRAK-M. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6062–6074. 10.1038/ncomms7062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiganescu A.; Walker E. A.; Hardy R. S.; Mayes A. E.; Stewart P. M. Localization, age- and site-dependent expression, and regulation of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 30–36. 10.1038/jid.2010.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Carver J. J.; Phelan V. V.; Sanchez L. M.; Garg N.; Peng Y.; Nguyen D. D.; Watrous J.; Kapono C. A.; Luzzatto-Knaan T.; Porto C.; Bouslimani A.; Melnik A. V.; Meehan M. J.; Liu W. T.; Crüsemann M.; Boudreau P. D.; Esquenazi E.; Sandoval-Calderón M.; Kersten R. D.; Pace L. A.; Quinn R. A.; Duncan K. R.; Hsu C. C.; Floros D. J.; Gavilan R. G.; Kleigrewe K.; Northen T.; Dutton R. J.; Parrot D.; Carlson E. E.; Aigle B.; Michelsen C. F.; Jelsbak L.; Sohlenkamp C.; Pevzner P.; Edlund A.; McLean J.; Piel J.; Murphy B. T.; Gerwick L.; Liaw C. C.; Yang Y. L.; Humpf H. U.; Maansson M.; Keyzers R. A.; Sims A. C.; Johnson A. R.; Sidebottom A. M.; Sedio B. E.; Klitgaard A.; Larson C. B.; Boya P C. A.; Torres-Mendoza D.; Gonzalez D. J.; Silva D. B.; Marques L. M.; Demarque D. P.; Pociute E.; O’Neill E. C.; Briand E.; Helfrich E. J. N.; Granatosky E. A.; Glukhov E.; Ryffel F.; Houson H.; Mohimani H.; Kharbush J. J.; Zeng Y.; Vorholt J. A.; Kurita K. L.; Charusanti P.; McPhail K. L.; Nielsen K. F.; Vuong L.; Elfeki M.; Traxler M. F.; Engene N.; Koyama N.; Vining O. B.; Baric R.; Silva R. R.; Mascuch S. J.; Tomasi S.; Jenkins S.; Macherla V.; Hoffman T.; Agarwal V.; Williams P. G.; Dai J.; Neupane R.; Gurr J.; Rodríguez A. M. C.; Lamsa A.; Zhang C.; Dorrestein K.; Duggan B. M.; Almaliti J.; Allard P. M.; Phapale P.; Nothias L. F.; Alexandrov T.; Litaudon M.; Wolfender J. L.; Kyle J. E.; Metz T. O.; Peryea T.; Nguyen D. T.; VanLeer D.; Shinn P.; Jadhav A.; Müller R.; Waters K. M.; Shi W.; Liu X.; Zhang L.; Knight R.; Jensen P. R.; Palsson B. Ø.; Pogliano K.; Linington R. G.; Gutiérrez M.; Lopes N. P.; Gerwick W. H.; Moore B. S.; Dorrestein P. C.; Bandeira N. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 828–837. 10.1038/nbt.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothias L.-F.; Petras D.; Schmid R.; Dührkop K.; Rainer J.; Sarvepalli A.; Protsyuk I.; Ernst M.; Tsugawa H.; Fleischauer M.; Aicheler F.; Aksenov A. A.; Alka O.; Allard P. M.; Barsch A.; Cachet X.; Caraballo-Rodriguez A. M.; da Silva R. R.; Dang T.; Garg N.; Gauglitz J. M.; Gurevich A.; Isaac G.; Jarmusch A. K.; Kameník Z.; Kang K. B.; Kessler N.; Koester I.; Korf A.; le Gouellec A.; Ludwig M.; Martin H. C.; McCall L. I.; McSayles J.; Meyer S. W.; Mohimani H.; Morsy M.; Moyne O.; Neumann S.; Neuweger H.; Nguyen N. H.; Nothias-Esposito M.; Paolini J.; Phelan V. V.; Pluskal T.; Quinn R. A.; Rogers S.; Shrestha B.; Tripathi A.; van der Hooft J. J. J.; Vargas F.; Weldon K. C.; Witting M.; Yang H.; Zhang Z.; Zubeil F.; Kohlbacher O.; Böcker S.; Alexandrov T.; Bandeira N.; Wang M.; Dorrestein P. C. Feature-based molecular networking in the GNPS analysis environment. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 905–908. 10.1038/s41592-020-0933-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dührkop K.; Fleischauer M.; Ludwig M.; Aksenov A. A.; Melnik A. V.; Meusel M.; Dorrestein P. C.; Rousu J.; Böcker S. SIRIUS 4: a rapid tool for Turning tandem mass spectra into metabolite structure information. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 229–302. 10.1038/s41592-019-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djoumbou Feunang Y.; Eisner R.; Knox C.; Chepelev L.; Hastings J.; Owen G.; Fahy E.; Steinbeck C.; Subramanian S.; Bolton E. ClassyFire: automated chemical classification with a comprehensive, computable taxonomy. Aust. J. Chem. 2016, 8, 1–20. 10.1186/s13321-016-0174-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dührkop K.; Shen H.; Meusel M.; Rousu J.; Böcker S. Searching molecular structure databases with tandem mass spectra using CSI: FingerID. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 12580–12585. 10.1073/pnas.1509788112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig M.; Nothias L.-F.; Dührkop K.; Koester I.; Fleischauer M.; Hoffmann M. A.; Petras D.; Vargas F.; Morsy M.; Aluwihare L.; Dorrestein P. C.; Böcker S. Database-independent molecular formula annotation using Gibbs sampling through ZODIAC. bioRxiv 2020, 2, 629–641. 10.1038/s42256-020-00234-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont R.; Balducci C.; Dinan L. Ecdysteroids. Encycl. 2021, 1, 1267–1302. 10.3390/encyclopedia1040096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ványolós A.; Simon A.; Tóth G.; Polgár L.; Kele Z.; Ilku A.; Mátyus P.; Báthori M. C-29 ecdysteroids from Ajuga reptans var. reptans. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 929–932. 10.1021/np800708g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadati N.; Jenett-Siems K.; Siems K.; Ardekani M. R. S.; Hadjiakhoondi A.; Akbarzadeh T.; Ostad S. N.; Khanavi M. Major constituents and cytotoxic effects of Ajuga chamaecistus ssp. tomentella. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 2012, 67, 275–281. 10.1515/znc-2012-5-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiftsoglou O. S.; Stefanakis M. K.; Lazari D. M. Chemical constituents isolated from the rhizomes of Helleborus odorus subsp. cyclophyllus (Ranunculaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2018, 79, 8–11. 10.1016/j.bse.2018.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gromkowska-Kępka K. J.; Puścion-Jakubik A.; Markiewicz-Żukowska R.; Socha K. The impact of ultraviolet radiation on skin photoaging—Review of in vitro studies. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3427–3431. 10.1111/jocd.14033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiganescu A.; Hupe M.; Jiang Y. J.; Celli A.; Uchida Y.; Mauro T. M.; Bikle D. D.; Elias P. M.; Holleran W. M. UVB induces epidermal 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 activity in vivo. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 24, 370–376. 10.1111/exd.12682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschel W.; Kump A.; Prieto J. M. Effects of 20-hydroxyecdysone, Leuzea carthamoides extracts, dexamethasone and their combinations on the NF-κB activation in HeLa cells. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 63, 1483–1495. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliouche L.; Larguet H.; Amrani A.; Leon F.; Brouard I.; Benayache S.; Zama D.; Meraihi Z.; Benayache F. Isolation, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Ecdysteroids from Serratula cichoracea. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2018, 14, 60–66. 10.2174/1573407214666171211154922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J.; Hwang H.; Selvaraj B.; Lee J. H.; Park W.; Ryu S. M.; Lee D.; Park J.-S.; Kim H. S.; Lee J. W.; et al. Phenolic constituents isolated from Senna tora sprouts and their neuroprotective effects against glutamate-induced oxidative stress in HT22 and R28 cells. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 114, 105112 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimblat N.; Zanardi M. M.; Sarotti A. M. Beyond DP4: an improved probability for the stereochemical assignment of isomeric compounds using quantum chemical calculations of NMR shifts. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 12526–12534. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K.; Ko Y. J.; Durai P.; Pan C. H. Machine learning-based chemical binding similarity using evolutionary relationships of target genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e128 10.1093/nar/gkz743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. S.; Ko K.; Kim S. H.; Lee J. K.; Park J. S.; Park K.; Kim M. R.; Kang K.; Oh D. C.; Kim S. Y.; et al. Tropolone-bearing sesquiterpenes from Juniperus chinensis: structures, photochemistry and bioactivity. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2020–2027. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razia S.; Park H.; Shin E.; Shim K.-S.; Cho E.; Kim S.-Y. Effects of Aloe vera flower extract and its active constituent isoorientin on skin moisturization via regulating involucrin expression: In vitro and molecular docking studies. Molecules 2021, 26, 2626. 10.3390/molecules26092626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.