ABSTRACT

Nuclear receptors are ligand-activated transcription factors that play an important role in regulating innate antiviral immunity and other biological processes. However, the role of nuclear receptors in the host response to infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) infection remains elusive. In this study, we show that IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment of DF-1 or HD11 cells markedly decreased nuclear receptor subfamily 2 group F member 2 (NR2F2) expression. Surprisingly, knockdown, knockout, or inhibition of NR2F2 expression in host cells remarkably inhibited IBDV replication and promoted IBDV/poly(I·C)-induced type I interferon and interferon-stimulated genes expression. Furthermore, our data show that NR2F2 negatively regulates the antiviral innate immune response by promoting the suppressor of cytokine signaling 5 (SOCS5) expression. Thus, reduced NR2F2 expression in the host response to IBDV infection inhibited viral replication by enhancing the expression of type I interferon by targeting SOCS5. These findings reveal that NR2F2 plays a crucial role in antiviral innate immunity, furthering our understanding of the mechanism underlying the host response to viral infection.

IMPORTANCE Infectious bursal disease (IBD) is an immunosuppressive disease causing considerable economic losses to the poultry industry worldwide. Nuclear receptors play an important role in regulating innate antiviral immunity. However, the role of nuclear receptors in the host response to IBD virus (IBDV) infection remains elusive. Here, we report that NR2F2 expression decreased in IBDV-infected cells, which consequently reduced SOCS5 expression, promoted type I interferon expression, and suppressed IBDV infection. Thus, NR2F2 serves as a negative factor in the host response to IBDV infection by regulating SOCS5 expression, and intervention in the NR2F2-mediated host response by specific inhibitors might be employed as a strategy for prevention and treatment of IBD.

KEYWORDS: NR2F2, IBDV, type I interferon, SOCS5

INTRODUCTION

Infectious bursal disease (IBD), also known as Gambro disease, is an acute and highly contagious disease caused by the IBD virus (IBDV), leading to substantial economic losses to the poultry industry worldwide (1). IBDV damages the bursa of Fabricius (BF) in 3- to 6-week-old chicks by destroying its target cells, the B lymphocyte precursors (2–4). Chickens infected with IBDV suffer from severe immunosuppression, leading to increased susceptibility to other pathogens and refractory to vaccines (1). IBDV, a member of the genus Avibirnavirus in the family Birnaviridae, is a nonenveloped and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus (5). The viral genome contains two RNA segments: segment A (3.17 kb) and segment B (2.8 kb) (6). Segment A comprises two partially overlapping open reading frames (ORFs), which encode nonstructural protein VP5 and a pVP2-VP4-VP3 precursor (7). The pVP2-VP4-VP3 precursor is cleaved by viral protease VP4 into pVP2, VP4, and VP3 (8). Segment B encodes VP1, an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) (8, 9).

Innate immunity is the first line of host defense against viral infection (10). Upon infection with RNA viruses, the host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as TLR3, MDA5, and RIG-I, sense the viral dsRNA in the cytoplasm and promote downstream type I interferon production to combat the viral infection (11). In chickens, MDA5 and TLR3 are the cellular sensors for viral dsRNA in the cytoplasm due to the genetic deficiency of RIG-I in chickens (12). Host cells restrict IBDV infection by producing type I interferon and inflammatory cytokines upon recognition of viral dsRNA by MDA5 and TLR3 (13, 14). In addition to PRRs, nuclear receptors play important roles in various physiological and pathobiological processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation (15), metabolism (16), immune regulation (17), tumor development (18), etc. Some nuclear receptors, such as the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), retinoid X receptor alpha (RXRα), and small heterodimer partner (SHP), are involved in regulating type I interferon production and viral replication (19–21). However, the role of nuclear receptors in the host response to IBDV infection remains unclear.

Nuclear receptor subfamily 2 group F member 2 (NR2F2), also known as chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II (COUP-TFII), is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily (22). NR2F2 plays a crucial role in many biological processes, including angiogenesis and heart development (23), neuronal development (24), cell fate determination (22), and metabolic homeostasis (25). It was reported that NR2F2 is required for regenerating the pulmonary vascular endothelium after viral pneumonia (26). However, the role of NR2F2 in the host response to IBDV infection is not clear.

In this study, we found that NR2F2 expression markedly decreased in host cells after IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment and that knockdown or knockout of NR2F2 in host cells promoted the expression of type I interferon and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) induced by IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment, suppressing IBDV replication. Importantly, we found that NR2F2 regulated the expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 5 (SOCS5), and overexpression of SOCS5 blocked the antiviral effect of NR2F2 deficiency in DF-1 cells, suggesting that NR2F2 is a negative regulator of innate immunity against viral infection.

RESULTS

IBDV infection reduced NR2F2 expression in DF-1 and HD11 cells.

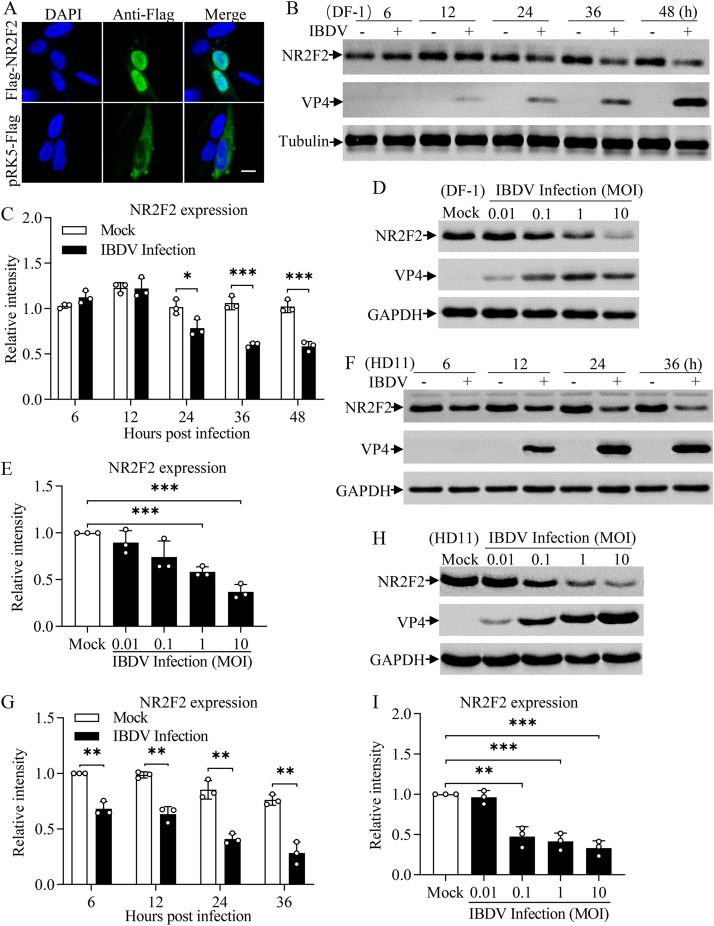

To determine if transcription factors were involved in the host response to IBDV infection, we performed a nuclear proteomic analysis of primary chicken embryonic fibroblasts (CEFs) infected with IBDV strain Lx and found many transcription factors that were differentially expressed (the CEF nuclear proteomic data are presented in the supplemental material). Among these differentially expressed proteins, nuclear receptor NR2F2 attracted our attention due to its involvement in the host response to virus infection (26, 27). In mammals, NR2F2 is located mainly in the nucleus and regulates the expression of downstream genes by binding to its promoter (26, 28). To determine the localization of chicken NR2F2 (chNR2F2) in chicken cells, we transfected DF-1 cells with a eukaryotic expression vector expressing chicken NR2F2 and observed the localization of chNR2F2 by laser confocal microscopy. Consistent with what is observed in mammals, chicken NR2F2 is located mainly in the nucleus (Fig. 1A). To further determine the effect of IBDV infection on NR2F2 expression, we infected DF-1 cells with IBDV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 at different time points or different doses and examined the expression of NR2F2 by Western blotting. As a result, the expression of NR2F2 in DF-1 cells markedly decreased after IBDV infection compared to that of controls in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B to E). To rule out the possibility that the decreased expression of NR2F2 in IBDV-infected cells was cell type specific, we infected cells of HD11, a chicken macrophage cell line, with IBDV and examined the expression of NR2F2 in cells after viral infection. Similarly, the expression of NR2F2 was dramatically downregulated in IBDV-infected HD11 cells compared to that in mock-infected cell controls in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1F to I). These results clearly show that the IBDV infection reduced the expression of NR2F2 in host cells, indicating involvement of NR2F2 in the host response to IBDV infection.

FIG 1.

NR2F2 expression was reduced in cells with IBDV infection. (A) Examination of the localization of NR2F2 by laser confocal scanning microscopy. DF-1 cells were seeded on 24-well plates with coverslips in the wells and cultured overnight. Cells were transfected with pRK5-Flag-NR2F2 or empty vector as a control. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were fixed, permeabilized, and probed with mouse anti-Flag antibodies, followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (green). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Cells were observed with a laser confocal scanning microscope. Bar = 10 μm. (B to E) IBDV infection reduced NR2F2 expression in DF-1 cells. DF-1 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at an MOI of 1. At different time points (6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h) after IBDV infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-tubulin antibodies (B). Endogenous tubulin expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for NR2F2 in panel B were quantitated by densitometry (C). The relative levels of NR2F2 were calculated as the ratio of the band density of NR2F2 to that of tubulin. DF-1 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at MOI of 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10. Twenty-four hours after infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (D). Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for NR2F2 in panel D were quantitated by densitometry (E). The relative levels of NR2F2 were calculated as the ratio of the band density of NR2F2 to that of GAPDH. (F to I) The expression of NR2F2 decreased in HD11 cells with IBDV infection. HD11 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at an MOI of 1. At the indicated time points after IBDV infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (F). Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for NR2F2 in panel F were quantitated by densitometry (G). HD11 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at MOI of 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10. Twenty-four hours after infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (H). Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for NR2F2 in panel H were quantitated by densitometry (I). The relative levels of NR2F2 were calculated as the ratio of the band density of NR2F2 to that of GAPDH. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Treatment of host cells with poly(I·C) decreased NR2F2 expression.

Upon infection with IBDV, the expression of host proteins altered in response to viral proteins or dsRNA (29, 30). To explore the effect of viral components (viral proteins or RNA) on the expression of NR2F2 in host cells after IBDV infection, we transfected DF-1 cells with eukaryotic expression vectors expressing the viral proteins (VP1 to VP5) of IBDV and examined the expression of NR2F2 in these cells by Western blotting. As a result, the ectopic expression of VP1 to VP5 in host cells did not alter NR2F2 expression compared to that of controls (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting that reduced expression of NR2F2 in IBDV-infected cells was unrelated to viral protein components.

FIG 2.

Effect of IBDV viral proteins and dsRNA on NR2F2 expression in cells. (A and B) IBDV viral proteins did not affect NR2F2 expression in host cells. DF-1 cells were transfected with pEGFP-N1, pEGFP-VP1, pEGFP-VP2, pEGFP-VP3, pEGFP-VP4, or pEGFP-VP5. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2, anti-GFP, and anti-GAPDH antibodies. Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for NR2F2 in panel A were quantitated by densitometry (B). The relative levels of NR2F2 were calculated as the band density of NR2F2/that of GAPDH. (C and D) The expression of NR2F2 decreased in DF-1 cells with poly(I·C) treatment. DF-1 cells were transfected with 0.1, 0.5, or 1 μg/mL of poly(I·C) or medium. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2 and anti-GAPDH antibodies. Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for NR2F2 in panel C were quantitated by densitometry (D). (E and F) NR2F2 expression was reduced in HD11 cells with poly(I·C) treatment. HD11 cells were transfected with 0.1, 0.5, or 1 μg/mL of poly(I·C) or medium. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2 and anti-GAPDH antibodies. Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for NR2F2 in panel E were quantitated by densitometry (F). Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

Since viral proteins do not affect the expression of NR2F2, we assumed that the viral genome (dsRNAs) might be responsible for the decreased expression of NR2F2 in IBDV-infected cells. To test this hypothesis, we transfected DF-1 cells with different doses of poly(I·C), a synthetic dsRNA analog. As shown in Fig. 2C and D, treatment of DF-1 cells with poly(I·C) markedly reduced the expression of NR2F2 in cells compared to that of controls, as did the expression of NR2F2 in poly(I·C)-treated HD11 cells compared to that of controls (Fig. 2E and F). These data suggest that the viral genome, rather than other components of IBDV, reduced NR2F2 expression in host cells.

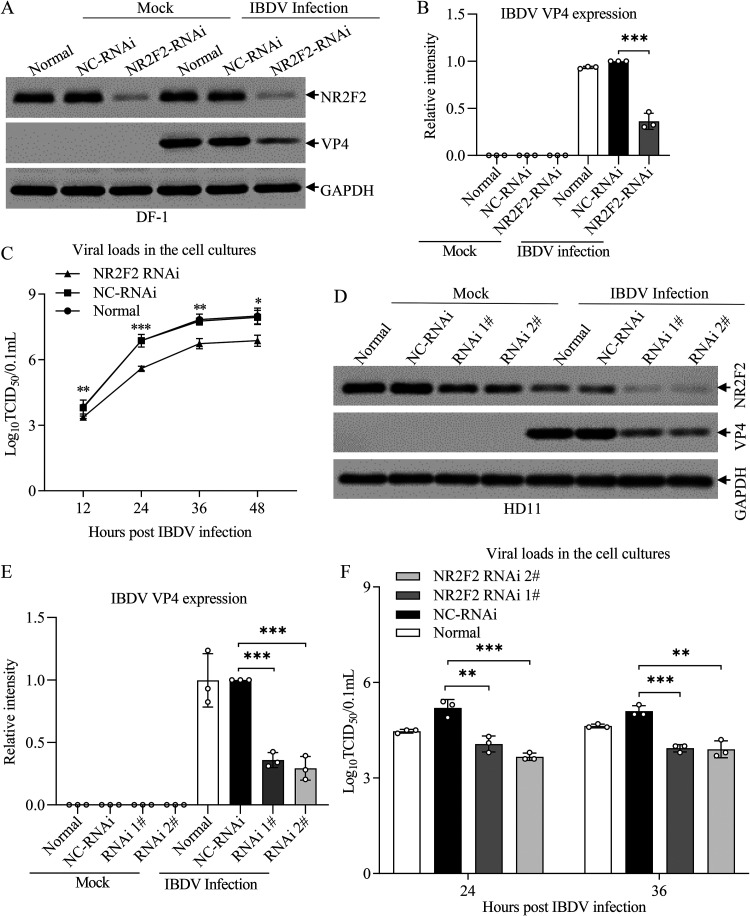

Knockdown or knockout of NR2F2 inhibited IBDV replication in host cells.

Since IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment decreased NR2F2 expression, we proposed that NR2F2 might play a crucial role in the host response to IBDV infection. To test this hypothesis, we knocked down NR2F2 expression by RNA interference (RNAi) in DF-1 cells, infected these cells with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1, and examined the effect of NR2F2 knockdown on IBDV replication. As a result, the expression of IBDV VP4 was significantly reduced in NR2F2 knockdown cells with IBDV infection compared to that of controls (Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, we measured IBDV growth in NR2F2-knockdown cells at different time points (12, 24, 36, and 48 h) after IBDV infection using 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) assays. As a result, viral titers in NR2F2-RNAi-treated DF-1 cells markedly decreased at 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after IBDV infection compared to that of the control (Fig. 3C). Consistently, knockdown of NR2F2 in HD11 cells significantly inhibited VP4 expression in IBDV-infected cells compared to that in RNAi controls (Fig. 3D and E), and the viral titers in NR2F2-RNAi-transfected HD11 cells markedly decreased at 24 and 36 h after IBDV infection compared to that of the control (Fig. 3F). These results clearly show that knockdown of NR2F2 expression in host cells inhibited IBDV replication, suggesting that NR2F2 is involved in the host response to IBDV infection.

FIG 3.

Knockdown of NR2F2 by RNAi suppressed IBDV replication. (A and B) Knockdown of NR2F2 by RNAi in DF-1 cells reduced IBDV VP4 expression. DF-1 cells were double transfected with NR2F2 siRNA 2# or RNAi controls at a 24-h interval. Twenty-four hours after the second transfection, cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. Twenty-four hours after infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (A). Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for VP4 in panel A were quantitated by densitometry (B). The relative levels of VP4 were calculated as the band density of VP4/that of GAPDH. (C) Knockdown of NR2F2 by RNAi in DF-1 cells suppressed IBDV growth. DF-1 cells were treated as described for panel A. At the indicated time points (12, 24, 36, and 48 h) after IBDV infection, the viral loads in the cell cultures were determined by TCID50 assays. (D and E) Knockdown of NR2F2 by RNAi in HD11 cells reduced IBDV VP4 expression. HD11 cells were transfected with NR2F2 siRNA 1#, siRNA 2#, or RNAi controls. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 1. Twenty-four hours after infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (D). Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for VP4 in panel D were quantitated by densitometry (E). (F) Knockdown of NR2F2 by RNAi in HD11 cells suppressed IBDV replication. HD11 cells were transfected with NR2F2 siRNA 1#, siRNA 2#, or RNAi controls. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. At 24 and 36 h after IBDV infection, the viral loads in the cell cultures were determined by TCID50 assays. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

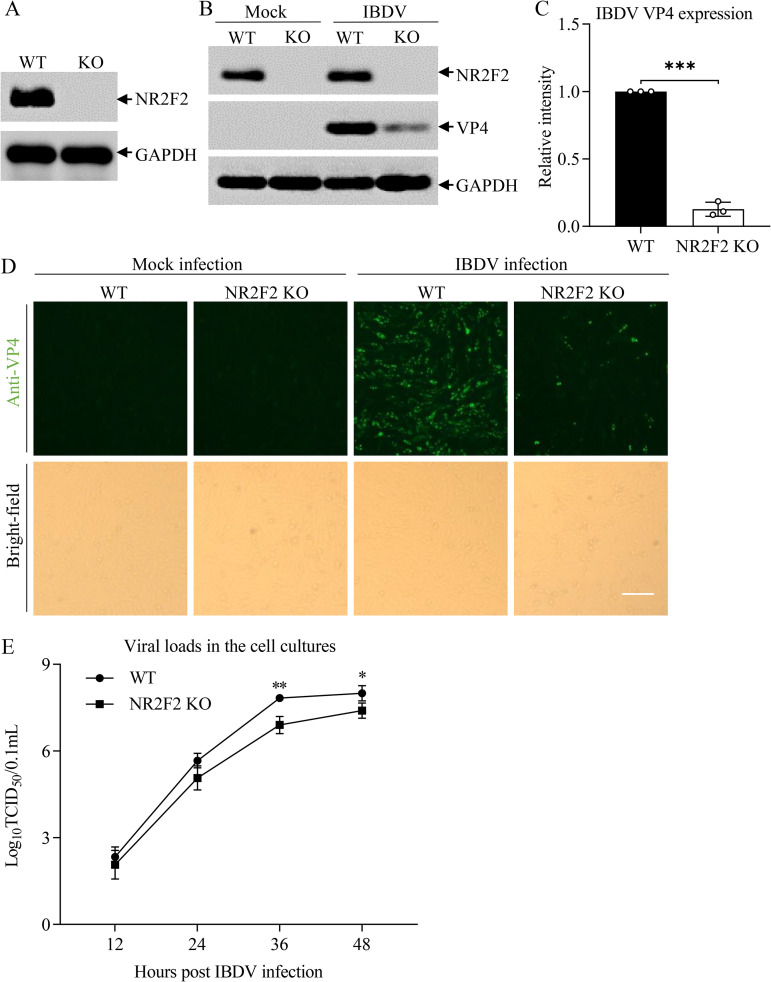

To consolidate these findings, we generated an NR2F2-deficient DF-1 cell line by the CRISPR-Cas9 method, infected wild-type (WT) DF-1 or NR2F2 knockout (NR2F2-KO) DF-1 cells with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1, and examined the expression of IBDV VP4 by Western blotting and indirect immunofluorescent-antibody assay (IFA). As shown in Fig. 4A, the established NR2F2 KO cell line was completely deficient in NR2F2, as demonstrated by Western blotting. Importantly, the NR2F2 deficiency in DF-1 cells markedly inhibited the expression of VP4 in IBDV-infected cells compared to that of the WT control (Fig. 4B to D) and significantly restricted IBDV growth at 36 and 48 h after IBDV infection compared to WT DF-1 cells (Fig. 4E), indicating that deficiency of NR2F2 in host cells suppressed IBDV replication. These results suggest that reduced NR2F2 expression in IBDV-infected cells is an important antiviral means employed by host cells in response to IBDV infection.

FIG 4.

NR2F2 deficiency suppressed IBDV replication. (A) Examination of NR2F2 expression in NR2F2 knockout DF-1 cell line by Western blotting. (B and C) Knockout of NR2F2 in DF-1 cells reduced IBDV VP4 expression. WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. Twenty-four hours after infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-GAPDH antibodies. Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for VP4 in panel B were quantitated by densitometry (C). The relative levels of VP4 were calculated as the ratio of the band density of VP4 to that of GAPDH. (D) Examination of IBDV replication in WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells by IFA. WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were fixed and examined for IBDV VP4 protein by immunofluorescence assays. The pictures in the upper panels were taken under a fluorescence microscope, and those in the lower panels were taken under a light microscope. Bar = 100 μm. (E) IBDV replication was suppressed in NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells. WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.01. At different time points (12, 24, 36, and 48 h) postinfection, the viral loads in the cell cultures were determined by TCID50 assays. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

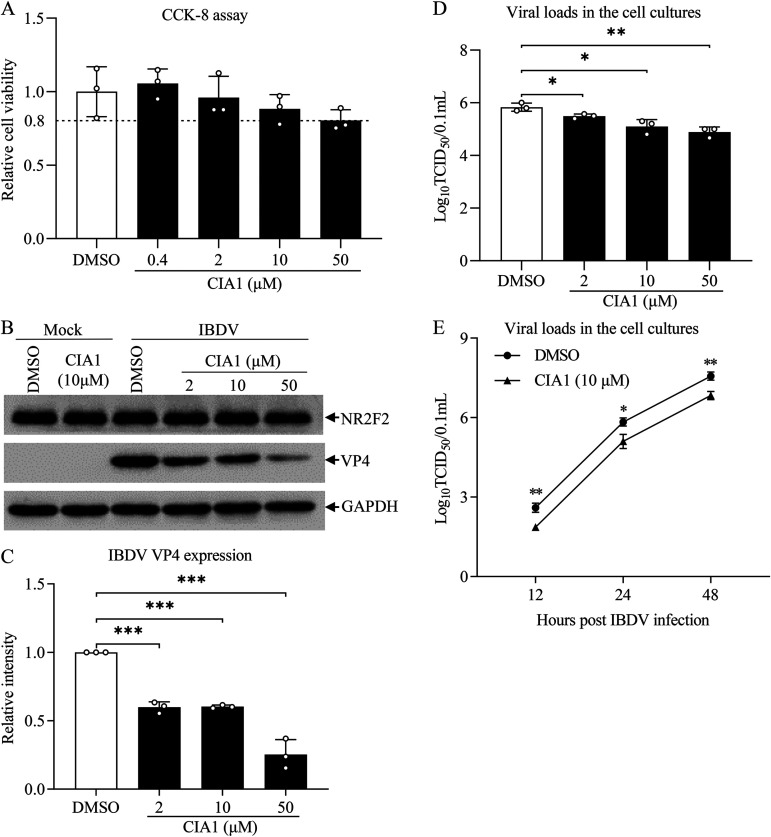

Inhibition of NR2F2 restricted IBDV replication in DF-1 cells.

Nuclear receptors are important targets for disease treatment. It was reported that CIA1 acted as a specific inhibitor of NR2F2, which might be used to treat cancers (31). Since knockdown or knockout of NR2F2 has an anti-IBDV effect, it was intriguing to ascertain the effect of the NR2F2-specific inhibitor CIA1 on IBDV replication. Thus, we treated DF-1 cells with 0.4 to 50 μM CIA1 and examined IBDV replication in host cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, treatment of cells with CIA1 did not have a discernible cytotoxic effect on cell viability, as demonstrated by a CCK-8 assay. Interestingly, we found that treatment of DF-1 cells with CIA1 at 2, 10, and 50 μM markedly decreased VP4 expression in IBDV-infected cells (Fig. 5B and C), suggesting that inhibition of NR2F2 by CIA1 suppressed viral replication. Furthermore, we measured IBDV growth in cells treated with CIA1 at different doses (2, 10, and 50 μM) and at different time points (12, 24, and 48 h) after IBDV infection using TCID50 assays. As a result, treatment of DF-1 cells with CIA1 significantly suppressed IBDV replication compared to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) treatment, and this suppression by CIA1 treatment occurred in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, treatment of DF-1 cells with CIA1 at 10 μM markedly inhibited IBDV replication at 12, 24, and 48 h after IBDV infection (Fig. 5E). These results indicate that inhibition of NR2F2 by the specific inhibitor CIA1 inhibited IBDV replication in host cells, supporting results showing that reduced NR2F2 expression in IBDV-infected cells suppressed viral replication.

FIG 5.

Inhibition of NR2F2 by the specific inhibitor CIA1 suppressed IBDV replication. (A) Examination of DF-1 cell viability by CCK-8 assay after incubation with the NR2F2 inhibitor CIA1 for 24 h. (B and C) CIA1 treatment reduced IBDV VP4 expression. DF-1 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. Two hours after infection, cells were treated with CIA1 at different doses (2, 10, and 50 μM) or DMSO control. Twenty-four hours after infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (B). Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for VP4 in panel B were quantitated by densitometry (C). The relative levels of VP4 were calculated as the band density of VP4/that of GAPDH. (D and E) CIA1 treatment suppressed IBDV growth. DF-1 cells were treated as described for panel B, and the viral loads in the cell cultures were determined by TCID50 assays (D). At the indicated time points (12, 24, and 48 h) after IBDV infection, the viral loads in the cell cultures were determined by TCID50 assays (E). Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Knockdown or knockout of NR2F2 enhanced IBDV/poly(I·C)-induced expression of type I interferon and interferon-stimulated genes in host cells.

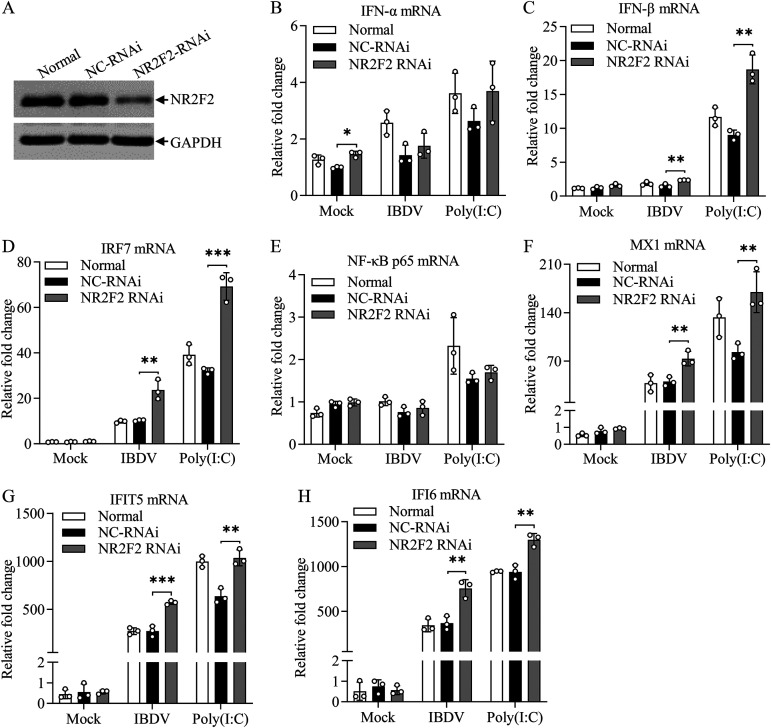

Since knockdown or knockout of NR2F2 inhibited IBDV replication, it was intriguing to explore the underlying mechanism. Host cells combat RNA virus infection by producing type I interferon upon recognition of viral dsRNA by pattern recognition receptors (11). We speculated that NR2F2 regulated type I interferon expression in cells with IBDV infection. To test this hypothesis, we transfected DF-1 cells with NR2F2 small interfering RNA (siRNA) and examined the expression of type I interferon in these cells with IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). As a result, the expression of NR2F2 was markedly reduced in NR2F2-RNAi cells (Fig. 6A), and knockdown of NR2F2 significantly increased the expression of beta interferon (IFN-β) rather than IFN-α in cells with IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment (Fig. 6B and C). Furthermore, we examined the expression of the type I interferon-related transcriptional regulators IRF7 and NF-κB (32). As shown in Fig. 6D and E, the expression of IRF7 markedly increased in NR2F2 knockdown cells with IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment compared to that in controls, whereas NF-κB p65 expression was not affected.

FIG 6.

Knockdown of NR2F2 by RNAi in DF-1 cells increased IBDV/poly(I·C)-induced expression of type I interferon and interferon-stimulated genes. DF-1 cells were transfected with NR2F2 siRNA 1# or RNAi controls. Thirty-six hours after transfection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-NR2F2 and anti-GAPDH antibodies (A). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 1 or treated with poly(I·C) at a final concentration of 0.4 μg/mL. Twelve hours after IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment, the mRNA expression of IFN-α (B), IFN-β (C), IRF7 (D), NF-κB p65 (E), MX1 (F), IFIT5 (G), and IFI6 (H) was measured by qRT-PCR using specific primers. The mRNA expression of GAPDH was used as an internal control. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) play a crucial role in the process of host resistance to viral infection (33). To explore whether NR2F2 affects the expression of ISGs, we examined the mRNA expression of three ISGs: MX1, IFIT5, and IFI6. Our data show that knockdown of NR2F2 markedly promoted the expression of MX1, IFIT5, and IFI6 in cells with IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment (Fig. 6F to H). These results indicate that the knockdown of NR2F2 increases the expression of type I interferon and ISGs in host cells in response to IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment. Furthermore, we examined the effect of NR2F2 inhibitor CIA1 on type I IFN responses after poly(I·C) treatment. We found that DF-1 cells with CIA1 treatment also enhanced poly(I·C)-induced expression of IFN-β, MX1, and IFI6 (see Fig. S1B to D in the supplemental material), suggesting that NR2F2 plays an important role in the type I interferon signaling pathway.

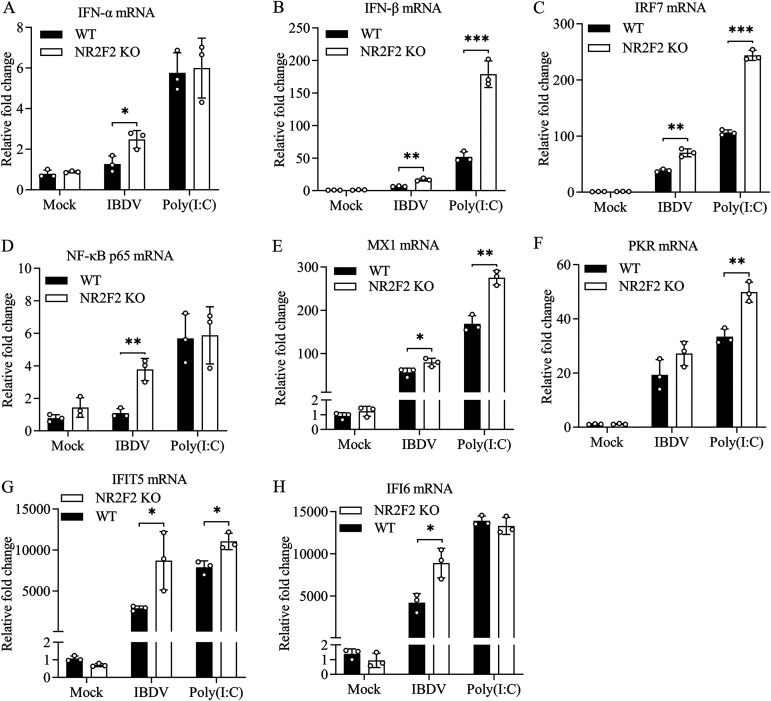

To consolidate these findings, we examined the expression of type I interferon and ISGs in NR2F2-KO cells with IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment. Consistently, NR2F2 deficiency in DF-1 cells with IBDV infection significantly promoted the mRNA expression of type I IFNs, IRF7, NF-κB p65, and ISGs (MX1, IFIT5, and IFI6) compared to that of WT controls (Fig. 7A to E, G, and H). Similarly, NR2F2 deficiency in DF-1 cells with poly(I·C) treatment markedly increased the mRNA expression of IFN-β, IRF7, MX1, PKR, and IFIT5 (Fig. 7B, C, and E to G). These results indicate that NR2F2 deficiency in DF-1 cells promotes the expression of type I interferon and ISGs in response to IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment.

FIG 7.

NR2F2 deficiency in DF-1 cells enhanced IBDV/poly(I·C)-induced expression of type I interferon and interferon-stimulated genes. WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 1 or treated with poly(I·C) at a final concentration of 0.4 μg/mL. Twelve hours after IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment, the mRNA expression of IFN-α (A), IFN-β (B), IRF7 (C), NF-κB p65 (D), MX1 (E), PKR (F), IFIT5 (G), and IFI6 (H) was measured by qRT-PCR. The mRNA expression of GAPDH was used as an internal control. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

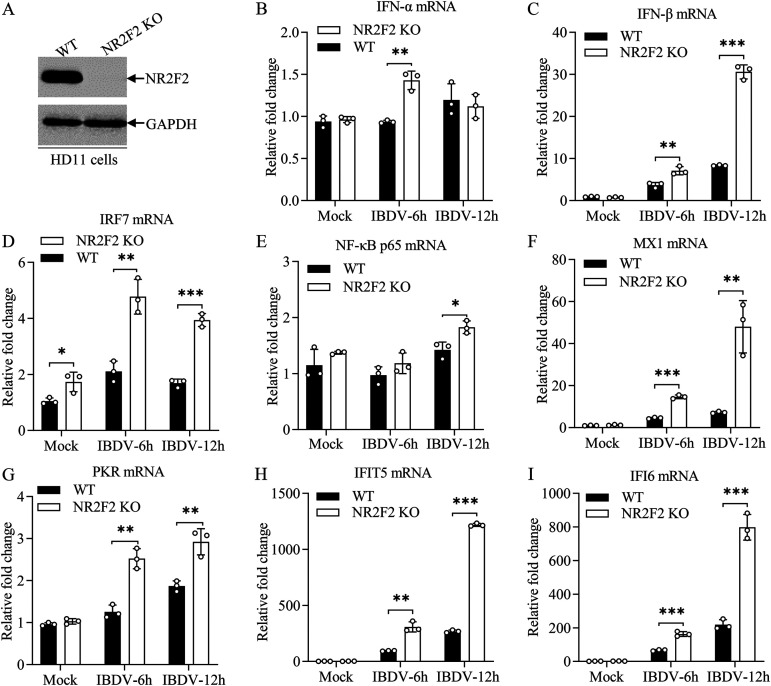

To further determine the regulatory effect of NR2F2 on the expression of type I interferon in host cells, we generated an NR2F2 knockout of HD11, a chicken macrophage cell line, using CRISPR-Cas9 (Fig. 8A), infected WT and NR2F2-KO HD11 cells with IBDV at an MOI of 5, performed qRT-PCR at 6 and 12 h after infection, and examined the expression of type I IFNs and ISGs. As shown in Fig. 8B to I, the expression of type I IFNs, ISGs, and related transcription factors significantly increased in NR2F2-deficient HD11 cells compared to that of WT control cells. These results show that knockdown or knockout of NR2F2 enhances the expression of type I interferon and ISGs in host cells in response to IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment, suggesting that NR2F2 serves as a negative regulator for the type I interferon signaling pathway.

FIG 8.

NR2F2 deficiency in HD11 cells enhanced IBDV-induced expression of type I interferon and interferon-stimulated genes. (A) Examination of NR2F2 expression in the NR2F2 knockout HD11 cell line by Western blotting. (B to I) The expression of type I interferon and ISGs was enhanced in NR2F2-KO HD11 cells with IBDV infection. WT and NR2F2-KO HD11 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 5. Six and 12 h after infection, the mRNA expression of IFN-α (B), IFN-β (C), IRF7 (D), NF-κB p65 (E), MX1 (F), PKR (G), IFIT5 (H), and IFI6 (I) was measured by qRT-PCR. The mRNA expression of GAPDH was used as an internal control. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

NR2F2 regulates SOCS5 expression.

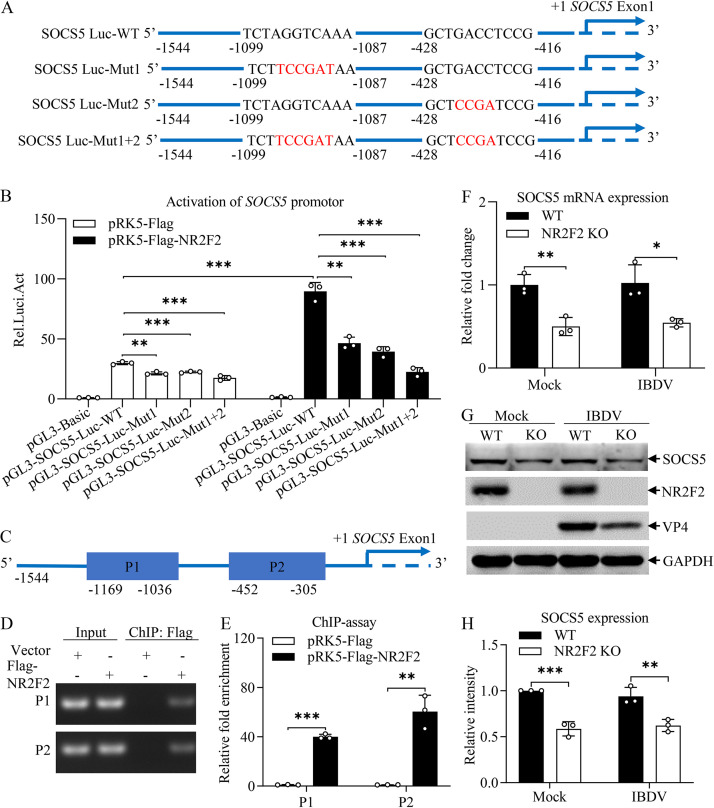

As NR2F2 is a ligand-dependent transcription factor regulating gene expression (26) and our data show that NR2F2 suppressed the expression of type I IFN and ISGs, we proposed that NR2F2 might regulate the expression of negative regulators for the immune response. It is well known that the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS), a negative regulator of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, suppresses the host response to viral infection (34). Thus, we examined the effect of NR2F2 on the expression of SOCS. Using the JASPAR database (https://jaspar.genereg.net/), we identified NR2F2 as the transcription factor that has multiple binding sites in the region of SOCS5 promoter. We cloned the promoter region (−1544 to +18) of SOCS5 into the luciferase reporter vector pGL3-Basic to examine the effect of NR2F2 on activation of SOCS5 promoter by luciferase reporter gene assay. As shown in Fig. 9A, the luciferase reporter gene plasmid pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-WT contained the SOCS5 promoter region, and other constructs (pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-Mut1, pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-Mut2, and pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-Mut1+2) had various mutations in the region of NR2F2 binding site. We transfected DF-1 cells with luciferase reporter plasmids (pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-WT or mutant plasmids) together with a NR2F2 eukaryotic expression plasmid or control plasmids, and performed a luciferase reporter gene assay to measure SOCS5 promoter activity. As a result, the promoter activation was markedly induced in DF-1 cells transfected with pRK5-Flag-NR2F2 together with pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-WT compared to that of control (Fig. 9B), while this induction was reduced in cells transfected with pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-Mut1 or pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-Mut2 and completely abolished in cells transfected with pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-Mut1+2, indicating that NR2F2 activated the SOCS5 promoter by binding to two sites in the region of SOCS5 promoter. Furthermore, we examined the NR2F2-binding region in SOCS5 promoter using a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay, focusing on the two binding regions (P1 and P2) as indicated in Fig. 9C. We transfected NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells with pRK5-Flag-NR2F2 or control vector and performed a ChIP assay using anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (MAb). As a result, the anti-Flag MAb readily pulled down SOCS5 promoter segments P1 and P2 in pRK5-Flag-NR2F2-transfected cells but not in the pRK5-Flag empty vector-transfected controls, as demonstrated by PCR and qPCR assays (Fig. 9D and E). These data indicate that NR2F2 activated the SOCS5 promoter by binding to its specific sites in the promoter.

FIG 9.

NR2F2 enhanced SOCS5 expression by binding to its promoter. (A) Schematic diagram of pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-WT and mutant plasmids. (B) Overexpression of NR2F2 induced activation of SOCS5 promoter. DF-1 cells were transfected with pRK5-Flag-NR2F2 or empty vector (pRK5-Flag) as a control together with the indicated reporter plasmids (pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-WT or mutant plasmids). pRL-TK plasmid was added to each transfection as a control. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and a luciferase reporter gene assay was performed to measure SOCS5 promoter activity. (C to E) Examination of the binding of NR2F2 to the SOCS5 promoter by ChIP analysis. Schematic diagram of the ChIP assay of SOCS5 promoter segments (C). NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were transfected with pRK5-Flag-NR2F2 or empty vector (pRK5-Flag) as a control. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were cross-linked and subjected to a ChIP assay using ChIP kits. The enrichment of SOCS5 promoter segments was analyzed by PCR (D) or qPCR (E) assays using specific primers. (F) Effect of NR2F2 deficiency on SOCS5 mRNA expression. WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at an MOI of 1. Twelve hours after infection, the mRNA expression of SOCS5 was measured by qRT-PCR using specific primers. The mRNA expression of GAPDH was used as an internal control. (G and H) Effect of NR2F2 deficiency on SOCS5 expression. WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. Twenty-four hours after infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-SOCS5, anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (G). Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for SOCS5 in panel G were quantitated by densitometry (H). The relative levels of SOCS5 were calculated as the ratio of the band density of SOCS5 to that of GAPDH. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Furthermore, we examined the expression of SOCS5 in DF-1 cells after CIA1 treatment. As a result, DF-1 cells treated with CIA1 inhibited the mRNA and protein expression of SOCS5 (Fig. S2A to C). To consolidate these findings, we examined the expression of SOCS5 in NR2F2-KO cells. As shown in Fig. 9F to H, deficiency of NR2F2 in NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells significantly reduced the expression of SOCS5 at both mRNA and protein levels compared to that of WT controls, with or without IBDV infection. These data suggest that NR2F2 acts as a transcriptional regulator, promoting SOCS5 expression by binding to its promoter.

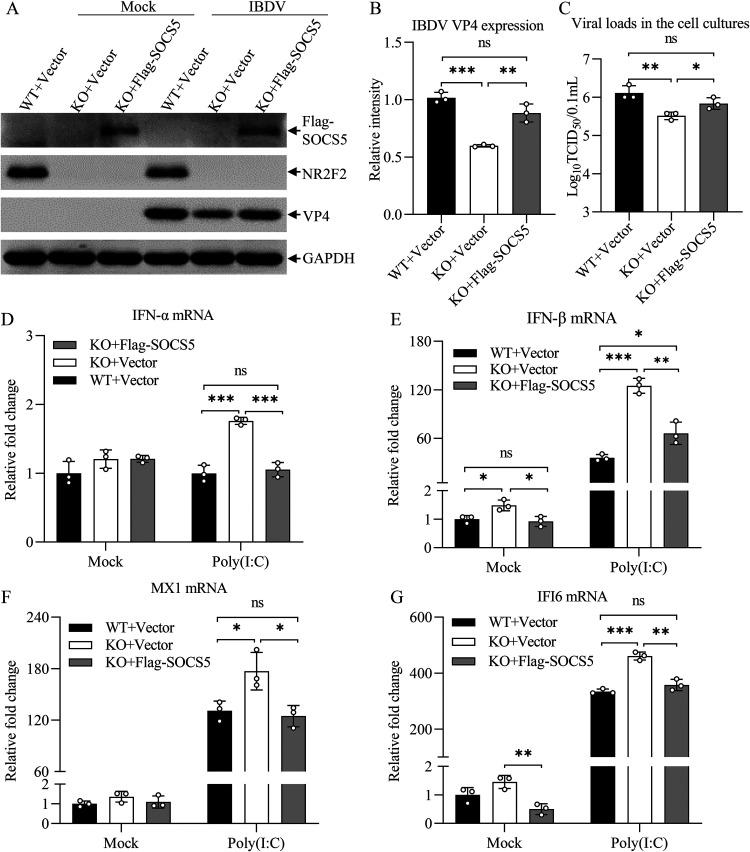

The antiviral effect of NR2F2 deficiency could be blocked by SOCS5 overexpression in host cells.

Since NR2F2 promotes SOCS5 expression, and our laboratory previously found that SOCS5 negatively regulated the type I interferon signaling pathway during IBDV infection (35), we assumed that NR2F2 inhibits the antiviral innate response by enhancing SOCS5 expression; therefore, overexpression of SOCS5 would block the inhibiting effect of NR2F2 deficiency on viral replication. To test this hypothesis, we transfected WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells with pRK5-Flag-SOCS5 or with empty vector (controls), infected these cells with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1, and examined IBDV replication in these cells by Western blot and TCID50 assays. As a result, the VP4 expression in IBDV-infected NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells was markedly reduced compared to that in WT controls, while this reduction could be completely abolished by overexpression of SOCS5 in NR2F2-KO cells (Fig. 10A and B). Consistently, the reduction of viral titers in NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells was blocked by overexpression of SOCS5 in cells (Fig. 10C). These data clearly show that NR2F2 inhibited antiviral innate response via SOCS5.

FIG 10.

The antiviral effect of NR2F2 deficiency in host cells could be blocked by SOCS5 overexpression. (A to C) Transfection of NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells with pRK5-Flag-SOCS5 blocked NR2F2 deficiency-mediated suppression of IBDV replication. WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were transfected with pRK5-Flag or pRK5-Flag-SOCS5. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. Twenty-four hours after infection, cell lysates were prepared and examined by Western blotting using anti-Flag, anti-NR2F2, anti-VP4, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (A). Endogenous GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The band intensities for VP4 in panel A were quantitated by densitometry (B). The relative levels of VP4 were calculated as the ratio of the band density of VP4 to that of GAPDH. The viral loads in the cell cultures were determined by TCID50 assays (C). (D to G) SOCS5 overexpression blocked NR2F2 deficiency-mediated enhancement of poly(I·C)-induced expression of type I interferon and interferon-stimulated genes. WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were transfected with pRK5-Flag or pRK5-Flag-SOCS5. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with poly(I·C) at a final concentration of 0.2 μg/mL. Twelve hours after treatment, the mRNA expression of IFN-α (D), IFN-β (E), MX1 (F), and IFI6 (G) was measured by qRT-PCR using specific primers. The mRNA expression of GAPDH was used as an internal control. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are means and SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

Because NR2F2 expression was reduced in poly(I·C)-treated cells and knockout of NR2F2 suppressed IBDV replication and enhanced the expression of type I interferon and ISGs, we hypothesized that NR2F2 inhibits poly(I·C)-induced type I interferon and ISG expression via SOCS5. To test this hypothesis, we transfected NR2F2-KO cells with pRK5-Flag-SOCS5, treated these cells with poly(I·C), and examined the expression of type I IFNs and ISGs in these cells by qRT-PCR analysis. As expected, the expression of type I IFNs and ISGs (MX1 and IFI6) was remarkably enhanced in NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells after poly(I·C) treatment compared to that of WT controls (Fig. 10D to G), while this enhancement could be completely abolished by overexpressing SOCS5 in NR2F2-KO cells with pRK5-Flag-SOCS5 transfection, indicating that NR2F2 negatively regulates the host innate response to viral infection by promoting SOCS5 expression.

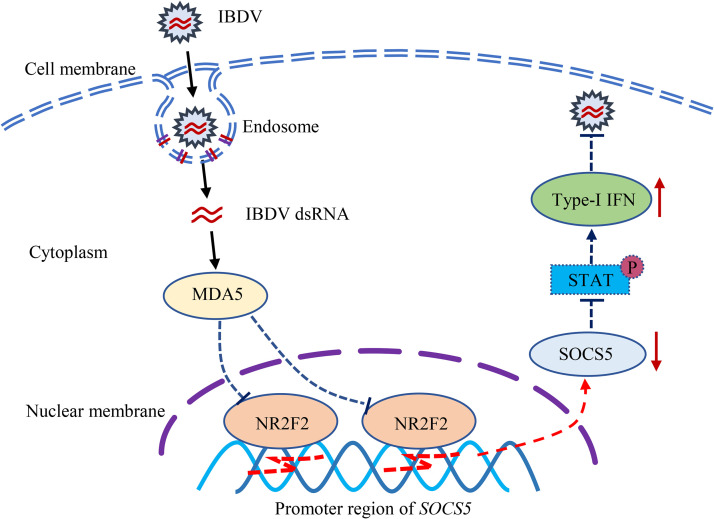

Taken together, our data show that NR2F2 expression was reduced in the host response to IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment and that reduction of NR2F2 expression in host cells resulted in promoting type I interferon expression and suppressing viral replication by reducing SOCS5 expression (Fig. 11). Thus, NR2F2 serves as a negative regulator for the host innate immune response to viral infection via direct promotion of SOCS5 expression.

FIG 11.

Model for the role of NR2F2 in the host response to IBDV infection. Recognition of IBDV dsRNA in the cytosol of host cells by the pattern recognition receptor MDA5 inhibits NR2F2 expression. As a consequence, the reduced expression of NR2F2 in IBDV-infected cells resulted in decreased SOCS5 expression, thereby enhancing type I interferon expression and suppressing IBDV replication.

DISCUSSION

Infectious bursal disease (IBD) is an immunosuppressive disease that damages the bursa of Fabricius in chickens (1). IBDV-infected chickens display compromised immune responses, leading to increased susceptibility to other pathogens (2, 4). Thus, IBD remains a threat to the poultry industry worldwide. In particular, the recent emergence of variant strains of IBDV in China caused a considerable economic loss to stakeholders (4, 36). Effective control of IBD by vaccination is in great demand in practice. However, knowledge regarding the pathogenesis of IBDV infection is currently insufficient to guide the development of novel vaccines for the effective control of IBD. In the present study, we first found that NR2F2 expression markedly decreased in host cells after IBDV infection or poly(I·C) treatment. Second, knockdown or knockout of NR2F2 or inhibition of NR2F2 by specific inhibitors in host cells suppressed IBDV replication. Third, knockdown or knockout of NR2F2 in host cells promoted IBDV- or poly(I·C)-induced type I interferon expression. Importantly, we found that NR2F2 bound to the promoter of SOCS5 and regulated its expression. Finally, our data show that NR2F2 regulated type I interferon production via SOCS5, thereby affecting IBDV replication. Our results, for the first time, reveal an important role of NR2F2 in the host immune response to IBDV infection.

IBDV, a double-stranded RNA virus, consists of five viral proteins (VP1 to VP5) (5). Upon IBDV infection, host cells sense the viral dsRNA by the pattern recognition receptors MDA5 and TLR3, initiating downstream type I interferon production to combat viral infection (13, 14). Recently it was found that the recognition of dsRNA of IBDV by MDA5 upregulated the expression of the transcription factor GATA3 in IBDV-infected cells and that GATA3 promotes the expression of miR-155, which increases the expression of type I interferon by targeting TANK and SOCS1, two negative regulators of host responses, and inhibits viral replication (29, 37). Thus, GATA3 serves as an antiviral factor in the host response to IBDV infection. In the present study, we identified another transcription factor, NR2F2, involved in the host response to viral infection, whose expression is downregulated in IBDV-infected cells, and found that NR2F2 suppressed the host response to viral infection by SOCS5, a negative regulator for STAT signaling pathway involved in the host response to infection (38). Therefore, NR2F2 serves as a suppressor for antiviral response to IBDV infection. It seems that hosts combat IBDV infection by upregulating GATA3 expression and downregulating NR2F2 expression, orchestrating various regulators to maximally enhance type I interferon expression and inhibit viral replication. Dulwich et al. demonstrated that the very virulent IBDV strain induces lower levels of IFN-I than the classical strain in vivo and in vitro, and this is due to strain-dependent differences in the VP4 protein (39). Our previous studies demonstrated that the VP4 protein of the Lx strain interacts with the glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) to antagonize host IFN-I production (40). In this study, we demonstrated that NR2F2 negatively regulates the host response to IBDV infection, and the viral genome, rather than other components of Lx, reduced NR2F2 expression in host cells. Thus, it is possible that the viral proteins (especially VP4) of very virulent strains may have additional countermeasures to prevent the downregulation of NR2F2. IBDV has evolved various strategies to evade the host responses for its own benefit (40). For example, IBDV protein VP4 interacts with the GILZ and increases GILZ expression by inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitylation of GILZ, inhibiting type I interferon expression (30, 40), while IBDV VP3 inhibits innate antiviral immunity by blocking viral dsRNA binding to MDA5 (41), TBK1-TRAF3 complex formation and IRF3 activation (42), and TRAF6-mediated NF-κB activation (43). Thus, the pathogenesis of IBDV infection and the molecular mechanism of the host response to IBDV infection seem much more complicated than anticipated.

The host response to viral infection is involved in alteration of antiviral molecule expression, including cellular proteins and noncoding RNAs (29, 44). Transcription factor GATA3, which was upregulated in IBDV-infected cells through the MDA5-TBK1-IRF7 pathway, promoted the expression of miR-155, increasing type I interferon expression and inhibiting viral replication (29, 37). miR-27b-3p and miR-130b, whose expression was upregulated after IBDV infection, promoted type I interferon expression and inhibited viral replication by targeting the suppressor of cytokine signaling proteins (35, 44). In this study, we found that the expression of NR2F2 decreased in IBDV-infected cells and that viral dsRNA, rather than viral proteins, reduced NR2F2 expression, suggesting that the host, upon sensing IBDV dsRNA in the cytosol by the pattern recognition receptor MDA5, initiated an antiviral response to reduce NR2F2 expression, which directly decreased the expression of SOCS5, thereby unharnessing the STAT-interferon signaling pathway and inhibiting viral replication. However, more efforts will be required to investigate the exact molecular mechanism underlying IBDV-reduced NR2F2 expression in host cells.

NR2F2 is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, which plays a crucial role in various biological processes (25). Lines of evidence show that nuclear receptors regulate diverse aspects of immunity, including T cell differentiation (45, 46), B cell responses to antigens (47), monocyte differentiation (15), the inflammatory response (48, 49), macrophage polarization (50), and the antiviral innate immune response (19, 21). It was reported that the abnormal expression of NR2F2 is associated with the development of Parkinson’s disease (51), heart failure (52), muscular dystrophy (53), and a variety of malignant tumors (54, 55). NR2F2 promotes the growth and metastasis of multiple tumors, including skin squamous cell carcinoma (18), prostate cancer (56, 57), and lung cancer (58). Interestingly, inhibition of NR2F2 activity by a chemical inhibitor (CIA1) was useful for the treatment of tumor diseases (18, 31). NR2F2, as an orphan nuclear receptor, can be activated by high concentrations of all-trans-retinoic acid and 9-cis-retinoic acid (59), and 1-deoxysphingolipids may be the endogenous ligand of NR2F2 (60). It was reported that NR2F2 was essential for pulmonary vascular endothelial regeneration after viral pneumonia (26). However, the role of NR2F2 in innate immunity against viral infection remains elusive. Our data demonstrate that NR2F2 is a negative regulator of type I interferon signaling and that inhibition of NR2F2 activity in host cells by a specific inhibitor (CIA1) or knockout or knockdown of NR2F2 in host cells markedly suppressed IBDV replication, furthering our understanding of the mechanism underlying host response to IBDV infection.

It was reported that nuclear receptors played an important role in the host response to viral infection (61, 62). Pseudorabies virus reduced the expression of liver X receptors (LXR) to promote viral infection (62). The expression of LXR was upregulated after gammaherpesvirus infection, and it inhibited gammaherpesvirus replication by suppressing the activity of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis pathways (63). In this study, our data show that a decrease in NR2F2 expression in IBDV-infected cells promoted type I interferon expression and restricted viral replication by targeting SOCS5, which supported the previous findings that some nuclear receptors are negative regulatory molecules of type I interferon expression (19–21). For example, SHP interacted with CREB-binding protein (CBP) in the nucleus after viral infection, thereby obstructing CBP/β-catenin interaction competitively, and then blocked the expression of type I interferon (21); constitutive AHR signaling inhibited type I interferon-mediated innate immune defense by upregulating the expression of the ADP-ribosylase TIPARP (19); and the expression of RXRα was downregulated after viral infection, poly(I·C), or poly(A·T) treatment, and RXRα suppressed type I interferon expression after virus infection by inhibiting nuclear translocation of β-catenin and then attenuating the host antiviral response (20). These findings show that nuclear receptors play an important role in innate immunity against viral infection. Investigation of the roles of other nuclear receptors in the host response to pathogenic infection should be strongly encouraged.

The suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS), a negative regulator of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, negatively regulates the host immune response to viral infection (34). Our previous studies showed that SOCS family proteins play an important role in the host response to IBDV infection (35, 44). Multiple antiviral miRNAs were found to exert antiviral effects in IBDV-infected cells by targeting SOCSs, promoting type I interferon expression, and inhibiting viral replication, such as miR-155 targeting SOCS1 (37), miR-130b targeting SOCS5 (35), and miR-27b-3p targeting SOCS3 and SOCS6 (44). SOCS5, a member of the SOCS family of proteins, is involved in the host response to viral infection (38) and promotes feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) and feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1) replication by inhibiting type I interferon signaling (64–66). However, upon infection with some viruses, such as duck Tembusu virus (DTMUV), novel duck reovirus (NDRV), and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), the cellular SOCS5 promoted an antiviral type I interferon response and inhibited viral replication (67–69). Therefore, SOCS5 may play a different role in type I interferon expression under different host and virus conditions. In the present study, we found that NR2F2 regulated the expression of SOCS5 and that the antiviral effect induced by NR2F2 deficiency could be blocked by SOCS5 overexpression, demonstrating that NR2F2 is involved in regulation of type I interferon signaling and inhibiting IBDV replication via SOCS5.

In conclusion, our data show that NR2F2 expression decreased in IBDV-infected cells, which consequently reduced SOCS5 expression, promoted type I interferon expression, and suppressed IBDV infection. Thus, NR2F2 serves as a negative factor in the host response to IBDV infection by regulating SOCS5 expression, and intervention with NR2F2-mediated host response by specific inhibitors might be employed as a strategy for prevention and treatment of IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

DF-1 (immortal chicken embryo fibroblasts) and HD11 (chicken macrophage-like cell line) cells were obtained from ATCC. DF-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) in a 5% CO2 incubator, and HD11 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Invitrogen). Lx, a cell-culture-adapted IBDV strain, was kindly provided by Jue Liu (Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry, Beijing, China).

Reagents.

All restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (USA). pRK5-Flag, pEGFP-N1, pGL3-Basic, and pRL-TK were obtained from Clontech (USA). Mouse monoclonal antibody against IBDV VP4 (catalog no. EU0207) was purchased from CAEU Biological Company (Beijing, China). Anti-NR2F2 rabbit monoclonal antibody (D16C4) and anti-Myc (9B11) mouse monoclonal antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA), anti-Flag mouse monoclonal antibody (F1804) was from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), anti-GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) monoclonal antibody (60004-1-Ig) was purchased from Proteintech, anti-α-tubulin MAb (M175-3) was from MBL (Japan), and anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) rabbit polyclonal antibody (AE011) was from ABclonal (Wuhan, China). Polyclonal antibodies against chicken SOCS5 were prepared by immunizing BALB/c mice with prokaryotically expressed chicken SOCS5 protein in our laboratory. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and goat anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Dingguo Company (Beijing, China). DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). Poly(I·C) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The NR2F2 inhibitor CIA1 (no. 7960292) was purchased from ChemBridge (USA).

Plasmids construction.

Chicken NR2F2 (GenBank accession number NM_204421.2) and SOCS5 (GenBank accession number XM_040697277.2) coding sequences were cloned from DF-1 cells using the following specific primers: for NR2F2, sense primer 5′-ATGGCAATGGTAGTCGGTG-3′ and antisense primer 5′-TTATTGAATGGACATGTAAGGCC-3′; for SOCS5, sense primer 5′-ATGGATAAAGTGGGAAAGATG-3′ and antisense primer 5′-TTACTTTGTTTTTATAGGTTCCCGC-3′. The promoter region of SOCS5 was amplified from the genomic DNA of DF-1 cells with the primers 5′-TCCTCTGGACCTGCTCAAAGAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGCGACACCTCGGTAGCCAATG-3′ (antisense). All the primers were synthesized by Sangon Company (Shanghai, China). pRK5-Flag-NR2F2, pRK5-Flag-SOCS5, and pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-WT/Mut1/Mut2/Mut1 + 2 were constructed by standard molecular biology techniques. pEGFP-N1-VP1, pEGFP-N1-VP2, pEGFP-N1-VP3, pEGFP-N1-VP4, and pEGFP-N1-VP5 were constructed previously by our laboratory (29, 70).

IFA.

WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were seeded on 12-well plates and cultured overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and incubated with anti-VP4 mouse monoclonal antibodies, followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (green). The cells were observed with a fluorescence microscope.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy assay.

DF-1 cells were seeded on coverslips in 24-well plates and were cultured overnight before transfection with pRK5-Flag-NR2F2 or pRK5-Flag. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 15 min, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin at 37°C for 1 h, and then probed with mouse anti-Flag antibodies at room temperature for 1 h, followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI at room temperature for 2 min. The samples were observed under a laser confocal scanning microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

qRT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was prepared from DF-1 cells using an RNAfast200 total RNA extraction kit (Fastagen, China) per the manufacturer’s instructions. One microgram of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis by reverse transcription using a HiScript III all-in-one RT SuperMix kit (Vazyme, China). The quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed using 2*M5 HiPer SYBR premix EsTaq (mei5bio, China) on a LightCycler 480 machine (Roche, USA). GAPDH was used as an endogenous control. All samples were performed in triplicate on the same plate. The gene expression levels were calculated relative to the GAPDH and are presented as fold change relative to the control. The following primers were used: for chicken IFN-α, 5′-CCAGCACCTCGAGCAAT-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGCGCTGTAATCGTTGTCT-3′ (antisense); for chicken IFN-β, 5′-GCCTCCAGCTCCTTCAGAATACG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTGGATCTGGTTGAGGAGGCTGT-3′ (antisense); for chicken IRF7, 5′-GCTCTCTGACTCTTTCAACCTCTT-3′ (sense) and 5′-AATGCTGCTCTTTTCTCCTCTG-3′ (antisense); for chicken NF-κB p65, 5′-CCACAACACAATGCGCTCTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-AACTCAGCGGCGTCGATG-3′ (antisense); for chicken MX1, 5′-GGTGTCATTACTCGCTGT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTTTCTTCACCTCTGATGC-3′ (antisense); for chicken PKR, 5′-GGCACCAGAACAGTTTGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTTCAGTGGAAGGTCACC-3′ (antisense); for chicken IFIT5, 5′-CCCTCTCAAGCTGAAGCACT-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGAACAGACAAGCAAACGCA-3′ (antisense); for chicken IFI6, 5′-TCAGGCTTTACCAGCAGTGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGCCACCCATTGAGATAGACTG-3′ (antisense); for chicken SOCS5, 5′-TTAGCCCCCGGTATGACTGA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGCGCGACTGTAGACAAAGT-3′ (antisense); for chicken GAPDH, 5′-TGCCATCACAGCCACACAGAAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACTTTCCCCACAGCCTTAGCAG-3′ (antisense). All primers were designed with reference to previous publications (35, 71) and synthesized by Sangon Company.

Western blot analysis.

To examine the NR2F2 expression in host cells, DF-1 or HD11 cells were seeded on 12-well cell culture plates and cultured overnight, followed by mock infection, infection with IBDV, or transfection with poly(I·C) or PBS, VP1-VP5 overexpression plasmids, or empty vectors using the transfection reagent jetPRIME. To determine the IBDV replication, DF-1 cells were transfected with NR2F2 siRNAs or controls and SOCS5 overexpression plasmids or empty vectors. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. To examine IBDV replication, DF-1 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1; 2 h after infection, cells were treated with CIA1 at different doses (2 μM, 10 μM, and 50 μM) or DMSO as a control. To analyze the expression of SOCS5, WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1. Cell lysates were prepared using a lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 5 mM EDTA; 1% NP-40; 10% glycerol; 1×complete protease inhibitor cocktail), boiled with 6× SDS loading buffer for 10 min. The denatured protein samples were separated by electrophoresis on SDS-PAGE gels, and resolved proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) or nitrocellulose (NC) membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk, the membranes were incubated with indicated antibodies, followed by incubation with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Blots were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Millipore, USA).

Cell viability assay.

The DF-1 cells were seeded on 96-well cell culture plates and cultured overnight. Cells were treated with different concentrations of the NR2F2 inhibitor CIA1 (0.4, 2, 10, and 50 μM) or DMSO control. Twenty-four hours after treatment, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent (Beyotime, China) was dispensed into each well, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h, and the optical density of the solution was measured at 450 nm using a microplate absorbance spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, USA). The results are representative of three independent experiments.

Knockdown of NR2F2 by RNAi.

To knock down the expression of NR2F2 in DF-1 and HD11 cells, siRNAs were designed and synthesized by Genepharma Company (Suzhou, China). The siRNAs for targeting NR2F2 in DF-1 and HD11 cells included RNAi 1# (sense, 5′-GCAUGUCGACUCCGCAGAATT-3′; antisense, 5′-UUCUGCGGAGUCGACAUGCTT-3′), RNAi 2# (sense, 5′-GAUGUAGCCCAUGUUGAAATT-3′; antisense, 5′-UUUCAACAUGGGCUACAUCTT-3′), and the negative-control siRNA (sense, 5′-GCGACGAUCUGCCUAAGAUTT-3′; antisense, 5′-AUCUUAGGCAGAUCGUCGCTT-3′). DF-1 and HD11 cells were seeded on 12-well cell culture plates and cultured overnight, followed by transfection with the NR2F2 siRNAs or negative-control siRNAs using the transfection reagent jetPRIME per the manufacturer’s instructions (PolyPlus, France). Double transfections were performed at 24-h intervals. Twenty-four hours after the second transfection, cell lysates were prepared and examined for NR2F2 by Western blotting.

Generation of NR2F2-deficient DF-1 and HD11 cells by CRISPR-Cas9.

To generate the NR2F2-deficient cell lines, the single guide RNA (sgRNA) was designed by CrispRGold (https://crisprgold.mdc-berlin.de/index.php). The sequence of sgRNA for targeting NR2F2 exon is 5′-GACGATGTGCCCGGAGCTCAGGG-3′. The sgRNA sequence was cloned as double-stranded oligonucleotides into the plasmid pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) (Addgene plasmid number 48138). DF-1 or HD11 cells were transfected with PX458-NR2F2 sgRNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were split and seeded on 96-well cell culture plates to establish single-cell clones. As soon as single-cell clones were visible, cell culture was extended before cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis for validation of NR2F2-deficient clones.

Dual-luciferase reporter gene assay.

To determine the activation of the SOCS5 promoter by transcription factor NR2F2, DF-1 cells were cotransfected with firefly luciferase reporter gene plasmids (pGL3-SOCS5-Luc-WT or mutant plasmids), pRK5-Flag-NR2F2, or vector controls using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, USA). To normalize for transfection efficiency, 20 ng of the pRL-TK Renilla luciferase reporter gene plasmid was added to each transfection. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase reporter gene assays were performed using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, USA). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized on the basis of Renilla luciferase activities. Each reporter gene assay was repeated at least three times. Data presented are means and standard deviations (SD).

ChIP assay.

The ChIP assay was performed using Pierce magnetic ChIP kit (26157; Thermo Fisher Scientific) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were transfected with pRK5-Flag-NR2F2 or control plasmids. Then, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde, the membrane and cytosol were lysed, and cells were digested with micrococcal nuclease (MNase). Nuclei were lysed by sonication to obtain chromatin, chromatin was incubated with anti-Flag antibody, and protein A/G magnetic beads were added for immunoprecipitation. After reverse cross-linking, the DNA samples were analyzed by qPCR or PCR. The following primers were used: for segment P1, 5′-TGCAGACCTTAGCTTCCCTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACCGTCAGACCAACACTTCAG-3′ (antisense); for segment P2, 5′-ACAGAATCACAGGACGGCTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGAGCCTTTTCTGCACCTCG-3′ (antisense).

Measurement of IBDV growth in DF-1 cells and HD11 cells.

To determine the effect of NR2F2 knockdown on IBDV replication, DF-1 and HD11 cells transfected with NR2F2-specific siRNAs or control siRNAs were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1, and cell cultures were collected at different time points (12, 24, 36, and 48 h) after infection. After being freeze-thawed three times, the samples were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were stored at −80°C until use. The viral titers in the total cell cultures were titrated using a TCID50 assay with DF-1 cells. Briefly, DF-1 cells were seeded on 96-well cell culture plates and cultured overnight, the viral fluid was diluted 10-fold in DMEM, and a 100-μL aliquot of each diluted sample was added to the well. DF-1 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 5 days, and cell culture wells with cytopathic effect (CPE) were determined to be positive. The titer was calculated based on the Reed-Muench method (72). To determine the effect of NR2F2 on IBDV replication, WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.01 or 0.1, and cell cultures were collected at different time points (12, 24, 36, and 48 h) after infection. Viral titers in cell cultures were determined by TCID50 assay as described above. To determine the effect of SOCS5 on IBDV replication, WT and NR2F2-KO DF-1 cells transfected with pRK5-Flag-SOCS5 or control plasmid were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1; 24 h after infection, cell cultures were collected, and the viral titers were determined by TCID50 assay as described above. To determine the effect of NR2F2 inhibition on IBDV replication, DF-1 cells were mock infected or infected with IBDV at an MOI of 0.1; 2 h after infection, cells were treated with CIA1 at different doses (2, 10, and 50 μM) or DMSO as controls. At different time points (12, 24, and 48 h) after infection, cell cultures were collected, and the viral titers were determined by TCID50 assay as described above.

Statistical analysis.

The statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. The significance of the differences between IBDV infection and mock infection, poly(I·C) treatment and controls, NR2F2 knockdown and controls, NR2F2-KO and WT controls, CIA1 treatment and DMSO-treated controls, and SOCS5 overexpression and controls with regard to gene expression, luciferase activities, and viral growth was analyzed using Student’s t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA). The data are presented as means and standard deviations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jue Liu and Wenhai Feng for their assistance.

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32130105), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1800300), and the Earmarked Fund for Modern Agro-Industry Technology Research System (No. CARS-40), China. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Li Gao, Email: 2019194@cau.edu.cn.

Shijun J. Zheng, Email: sjzheng@cau.edu.cn.

Bryan R. G. Williams, Hudson Institute of Medical Research

REFERENCES

- 1.Jackwood DJ. 2017. Advances in vaccine research against economically important viral diseases of food animals: infectious bursal disease virus. Vet Microbiol 206:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Withers DR, Young JR, Davison TF. 2005. Infectious bursal disease virus-induced immunosuppression in the chick is associated with the presence of undifferentiated follicles in the recovering bursa. Viral Immunol 18:127–137. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez-Lecompte JC, Nino-Fong R, Lopez A, Frederick Markham RJ, Kibenge FS. 2005. Infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) induces apoptosis in chicken B cells. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 28:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan L, Wu T, Wang Y, Hussain A, Jiang N, Gao L, Li K, Gao Y, Liu C, Cui H, Pan Q, Zhang Y, Wang X, Qi X. 2020. Novel variants of infectious bursal disease virus can severely damage the bursa of fabricius of immunized chickens. Vet Microbiol 240:108507. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahgoub HA, Bailey M, Kaiser P. 2012. An overview of infectious bursal disease. Arch Virol 157:2047–2057. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller H, Scholtissek C, Becht H. 1979. The genome of infectious bursal disease virus consists of two segments of double-stranded RNA. J Virol 31:584–589. doi: 10.1128/JVI.31.3.584-589.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mundt E, Beyer J, Muller H. 1995. Identification of a novel viral protein in infectious bursal disease virus-infected cells. J Gen Virol 76:437–443. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-2-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lombardo E, Maraver A, Caston JR, Rivera J, Fernandez-Arias A, Serrano A, Carrascosa JL, Rodriguez JF. 1999. VP1, the putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of infectious bursal disease virus, forms complexes with the capsid protein VP3, leading to efficient encapsidation into virus-like particles. J Virol 73:6973–6983. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.8.6973-6983.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan MM, Macreadie IG, Harley VR, Hudson PJ, Azad AA. 1988. Sequence of the small double-stranded RNA genomic segment of infectious bursal disease virus and its deduced 90-kDa product. Virology 163:240–242. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesev EV, LeDesma RA, Ploss A. 2019. Decoding type I and III interferon signalling during viral infection. Nat Microbiol 4:914–924. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0421-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehwinkel J, Gack MU. 2020. RIG-I-like receptors: their regulation and roles in RNA sensing. Nat Rev Immunol 20:537–551. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0288-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SB, Park YH, Chungu K, Woo SJ, Han ST, Choi HJ, Rengaraj D, Han JY. 2020. Targeted knockout of MDA5 and TLR3 in the DF-1 chicken fibroblast cell line impairs innate immune response against RNA ligands. Front Immunol 11:678. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X, Chen Y, Kang S, Chen G, Wei P. 2017. Differential regulation of chTLR3 by infectious bursal disease viruses with different virulence in vitro and in vivo. Viral Immunol 30:490–499. doi: 10.1089/vim.2016.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CC, Wu CC, Lin TL. 2014. Chicken melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) recognizes infectious bursal disease virus infection and triggers MDA5-related innate immunity. Arch Virol 159:1671–1686. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-1983-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider C, Nobs SP, Kurrer M, Rehrauer H, Thiele C, Kopf M. 2014. Induction of the nuclear receptor PPAR-gamma by the cytokine GM-CSF is critical for the differentiation of fetal monocytes into alveolar macrophages. Nat Immunol 15:1026–1037. doi: 10.1038/ni.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou B, Jia L, Zhang Z, Xiang L, Yuan Y, Zheng P, Liu B, Ren X, Bian H, Xie L, Li Y, Lu J, Zhang H, Lu Y. 2020. The nuclear orphan receptor NR2F6 promotes hepatic steatosis through upregulation of fatty acid transporter CD36. Adv Sci (Weinh) 7:2002273. doi: 10.1002/advs.202002273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass CK, Saijo K. 2010. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat Rev Immunol 10:365–376. doi: 10.1038/nri2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mauri F, Schepkens C, Lapouge G, Drogat B, Song Y, Pastushenko I, Rorive S, Blondeau J, Golstein S, Bareche Y, Miglianico M, Nkusi E, Rozzi M, Moers V, Brisebarre A, Raphael M, Dubois C, Allard J, Durdu B, Ribeiro F, Sotiriou C, Salmon I, Vakili J, Blanpain C. 2021. NR2F2 controls malignant squamous cell carcinoma state by promoting stemness and invasion and repressing differentiation. Nat Cancer 2:1152–1169. doi: 10.1038/s43018-021-00287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada T, Horimoto H, Kameyama T, Hayakawa S, Yamato H, Dazai M, Takada A, Kida H, Bott D, Zhou AC, Hutin D, Watts TH, Asaka M, Matthews J, Takaoka A. 2016. Constitutive aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling constrains type I interferon-mediated antiviral innate defense. Nat Immunol 17:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni.3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma F, Liu SY, Razani B, Arora N, Li B, Kagechika H, Tontonoz P, Nunez V, Ricote M, Cheng G. 2014. Retinoid X receptor alpha attenuates host antiviral response by suppressing type I interferon. Nat Commun 5:5494. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JH, Yoon JE, Nikapitiya C, Kim TH, Uddin MB, Lee HC, Kim YH, Hwang JH, Chathuranga K, Chathuranga WAG, Choi HS, Kim CJ, Jung JU, Lee CH, Lee JS. 2019. Small heterodimer partner controls the virus-mediated antiviral immune response by targeting CREB-binding protein in the nucleus. Cell Rep 27:2105–2118.E5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su T, Stanley G, Sinha R, D’Amato G, Das S, Rhee S, Chang AH, Poduri A, Raftrey B, Dinh TT, Roper WA, Li G, Quinn KE, Caron KM, Wu S, Miquerol L, Butcher EC, Weissman I, Quake S, Red-Horse K. 2018. Single-cell analysis of early progenitor cells that build coronary arteries. Nature 559:356–362. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0288-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira FA, Qiu Y, Zhou G, Tsai MJ, Tsai SY. 1999. The orphan nuclear receptor COUP-TFII is required for angiogenesis and heart development. Genes Dev 13:1037–1049. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanatani S, Honda T, Aramaki M, Hayashi K, Kubo K, Ishida M, Tanaka DH, Kawauchi T, Sekine K, Kusuzawa S, Kawasaki T, Hirata T, Tabata H, Uhlen P, Nakajima K. 2015. The COUP-TFII/neuropilin-2 is a molecular switch steering diencephalon-derived GABAergic neurons in the developing mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:E4985–E4994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420701112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Xie X, Qin J, Jeha GS, Saha PK, Yan J, Haueter CM, Chan L, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. 2009. The nuclear orphan receptor COUP-TFII plays an essential role in adipogenesis, glucose homeostasis, and energy metabolism. Cell Metab 9:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao G, Weiner AI, Neupauer KM, de Mello Costa MF, Palashikar G, Adams-Tzivelekidis S, Mangalmurti NS, Vaughan AE. 2020. Regeneration of the pulmonary vascular endothelium after viral pneumonia requires COUP-TF2. Sci Adv 6:7eabc4493. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou S, Guan H, Ricciardi RP. 2002. In adenovirus type 12 tumorigenic cells, major histocompatibility complex class I transcription shutoff is overcome by induction of NF-kappaB and relief of COUP-TFII repression. J Virol 76:3212–3220. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.7.3212-3220.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamazaki T, Yoshimatsu Y, Morishita Y, Miyazono K, Watabe T. 2009. COUP-TFII regulates the functions of Prox1 in lymphatic endothelial cells through direct interaction. Genes Cells 14:425–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Haiyilati A, Zhou L, Chen J, Wang Y, Gao L, Cao H, Li X, Zheng SJ. 2022. GATA3 inhibits viral infection by promoting microRNA-155 expression. J Virol 96:e01888-21. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01888-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He Z, Chen X, Fu M, Tang J, Li X, Cao H, Wang Y, Zheng SJ. 2018. Infectious bursal disease virus protein VP4 suppresses type I interferon expression via inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitylation of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ). Immunobiology 223:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2017.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Cheng CM, Qin J, Xu M, Kao CY, Shi J, You E, Gong W, Rosa LP, Chase P, Scampavia L, Madoux F, Spicer T, Hodder P, Xu HE, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. 2020. Small-molecule inhibitor targeting orphan nuclear receptor COUP-TFII for prostate cancer treatment. Sci Adv 6:eaaz8031. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz8031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Chen ZJ. 2005. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell 122:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM. 2014. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu Rev Immunol 32:513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshimura A, Naka T, Kubo M. 2007. SOCS proteins, cytokine signalling and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol 7:454–465. doi: 10.1038/nri2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu M, Wang B, Chen X, He Z, Wang Y, Li X, Cao H, Zheng SJ. 2018. MicroRNA gga-miR-130b suppresses infectious bursal disease virus replication via targeting of the viral genome and cellular suppressors of cytokine signaling 5. J Virol 92:e01646-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01646-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Qiao Y, Deng Q, Chen R, Chen J, Huang T, Wei T, Mo M, He X, Wei P. 2022. The emerging naturally reassortant strain of IBDV (genotype A2dB3) having segment A from Chinese novel variant strain and segment B from HLJ 0504-like very virulent strain showed enhanced pathogenicity to three-yellow chickens. Transbound Emerg Dis 69:e566–e579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang B, Fu M, Liu Y, Wang Y, Li X, Cao H, Zheng SJ. 2018. gga-miR-155 enhances type I interferon expression and suppresses infectious burse [sic] disease virus replication via targeting SOCS1 and TANK. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:55. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang S, Liu K, Cheng A, Wang M, Cui M, Huang J, Zhu D, Chen S, Liu M, Zhao X, Wu Y, Yang Q, Zhang S, Ou X, Mao S, Gao Q, Yu Y, Tian B, Liu Y, Zhang L, Yin Z, Jing B, Chen X, Jia R. 2020. SOCS proteins participate in the regulation of innate immune response caused by viruses. Front Immunol 11:558341. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.558341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dulwich KL, Asfor A, Gray A, Giotis ES, Skinner MA, Broadbent AJ. 2020. The stronger downregulation of in vitro and in vivo innate antiviral responses by a very virulent strain of infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV), compared to a classical strain, is mediated, in part, by the VP4 protein. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:315. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Z, Wang Y, Li X, Li X, Cao H, Zheng SJ. 2013. Critical roles of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper in infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV)-induced suppression of type I interferon expression and enhancement of IBDV growth in host cells via interaction with VP4. J Virol 87:1221–1231. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02421-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ye C, Jia L, Sun Y, Hu B, Wang L, Lu X, Zhou J. 2014. Inhibition of antiviral innate immunity by birnavirus VP3 protein via blockage of viral double-stranded RNA binding to the host cytoplasmic RNA detector MDA5. J Virol 88:11154–11165. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01115-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng T, Hu B, Wang X, Lin L, Zhou J, Xu Y, Yan Y, Zheng X, Zhou J. 2021. Inhibition of antiviral innate immunity by avibirnavirus VP3 via blocking TBK1-TRAF3 complex formation and IRF3 activation. mSystems 6:e00016-21. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00016-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng T, Hu B, Wang X, Ding S, Lin L, Yan Y, Peng X, Zheng X, Liao M, Jin Y, Dong W, Gu J, Zhou J. 2022. TRAF6 autophagic degradation by avibirnavirus VP3 inhibits antiviral innate immunity via blocking NFKB/NF-kappaB activation. Autophagy 18:2781–2798. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2022.2047384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duan X, Zhao M, Li X, Gao L, Cao H, Wang Y, Zheng SJ. 2020. gga-miR-27b-3p enhances type I interferon expression and suppresses infectious bursal disease virus replication via targeting cellular suppressors of cytokine signaling 3 and 6 (SOCS3 and 6). Virus Res 281:197910. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.197910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hermann-Kleiter N, Gruber T, Lutz-Nicoladoni C, Thuille N, Fresser F, Labi V, Schiefermeier N, Warnecke M, Huber L, Villunger A, Eichele G, Kaminski S, Baier G. 2008. The nuclear orphan receptor NR2F6 suppresses lymphocyte activation and T helper 17-dependent autoimmunity. Immunity 29:205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang XO, Pappu BP, Nurieva R, Akimzhanov A, Kang HS, Chung Y, Ma L, Shah B, Panopoulos AD, Schluns KS, Watowich SS, Tian Q, Jetten AM, Dong C. 2008. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR alpha and ROR gamma. Immunity 28:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan C, Hiwa R, Mueller JL, Vykunta V, Hibiya K, Noviski M, Huizar J, Brooks JF, Garcia J, Heyn C, Li Z, Marson A, Zikherman J. 2020. NR4A nuclear receptors restrain B cell responses to antigen when second signals are absent or limiting. Nat Immunol 21:1267–1279. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0765-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuk JM, Kim TS, Kim SY, Lee HM, Han J, Dufour CR, Kim JK, Jin HS, Yang CS, Park KS, Lee CH, Kim JM, Kweon GR, Choi HS, Vanacker JM, Moore DD, Giguere V, Jo EK. 2015. Orphan nuclear receptor ERRalpha controls macrophage metabolic signaling and A20 expression to negatively regulate TLR-induced inflammation. Immunity 43:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang M, Yan Y, Zhang Z, Yao X, Duan X, Jiang Z, An J, Zheng P, Han Y, Wu H, Wang Z, Glauben R, Qin Z. 2021. Programmed PPAR-alpha downregulation induces inflammaging by suppressing fatty acid catabolism in monocytes. iScience 24:102766. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]