Abstract

Objectives

Although the number of disabled women entering motherhood is growing, there is little quantitative evidence about the utilisation of essential antenatal care (ANC) services by women with disabilities. We examined inequalities in the use of essential ANC services between women with and without disabilities.

Design, setting and analysis

A secondary analysis of cross-sectional data from recent Demographic and Health Survey of Pakistan 2017–2018 was performed using logistic regression.

Participants

A total weighted sample of 6791 ever-married women (age 15–49) who had a live birth in the 5 years before the survey were included.

Outcome measures

Utilisation of ANC: (A) antenatal coverage: (1) received ANC and (2) completed four or more ANC visits and (B) utilisation of essential components of ANC.

Results

The percentage of women who were at risk of disability and those living with disability in one or more domains was 11.5% and 2.6%, respectively. The coverage of ANC did not differ by disability status. With utilisation of essential ANC components, consumption of iron was lower (adjusted OR, aOR=0.6; p<0.05), while advice on exclusive breast feeding (aOR=1.6; p<0.05) and urine test (aOR=1.7; p<0.05) was higher among women with disabilities as compared with their counterparts. Similarly, the odds of receiving advice on maintaining a balanced diet was higher (aOR=1.3; p<0.05) among women at risk of any disability as opposed to their counterparts. Differences were also found for these same indicators in subgroup analysis by wealth status (poor/non-poor) and place of residence (urban–rural).

Conclusion

Our study did not find glaring inequalities in the utilisation of ANC services between women with disabilities and non-disabled women. This was true for urban versus rural residence and among the poor versus non-poor women. Some measures, however, should be made to improve medication compliance among women with disabilities.

Keywords: antenatal, maternal medicine, quality in health care

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Our study used nationally representative data to determine the association between disability and utilisation of antenatal care (ANC).

Cluster effect and sample weighting were taken into consideration in the analysis of this study.

Our capacity to infer causality was constrained by the inherent drawbacks of a cross-sectional study design.

Our study did not present the association between each type of disability and ANC outcomes due to low percentages.

The study is limited by the type of measure included in the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (eg, duration of disability and disability status of women during pregnancy).

Background

Over a billion people across the globe have different forms of disability, with 80% living in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 Individuals with disabilities are the world’s largest minority, which is constantly increasing from population growth and chronic medical conditions.2 The conceptualisation of disability is complicated and it varies due to its dynamic and multidimensional nature.3 While there is no unanimously agreed definition of disability,4 the most commonly used is provided by the United Nation, which is, ‘long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder individual’s full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others’.5

Global awareness of disability-inclusive development is increasing. The Sustainable Development Goal 3 seeks to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all people at all ages.2 The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities reinforces the privileges of persons with disabilities to attain the highest standard of healthcare services without any discrimination.6 However, despite global commitments, individuals with disabilities often live in poverty and experience poor health due to stigma and exclusions from employment, education and access to healthcare services.7 8

The number of disabled women who are entering motherhood is growing,9 although their ability to engage in a sexual relationship, marriage, caregiving and mothering is often questioned.10–12 Although women with disabilities have the same or even greater biological and social needs and legitimate rights for sexual and reproductive (SRH) education and care,12 they face a plethora of health system challenges such as: physical inaccessibility, negative and abusive health workers’ attitudes, long queues at the health facilities to seek high-quality and affordable SRH services when compared with women without disabilities.7 8 13–15 Apart from the health system factors, individual and community level factors such as: sociocultural and religious beliefs, low literacy level, communication barriers, negative public attitude, social stigma, sexual violence and lack of social support also play a pivotal role to access high quality reproductive health services by women with disabilities.16 However, a few studies also highlight that utilisation of maternal and reproductive health services among women with disabilities is either better or not much different from non-disabled women.8 17–21 By and large, there are mixed findings regarding using maternal healthcare services among women with disabilities.

Due to inequalities in and substandard quality of healthcare services, maternal and child mortality and morbidity remain a major public health concern for LMICs, particularly in South Asia.22 Among several interventions, high-quality of antenatal care (ANC) has been shown to improve maternal23 and child24 health outcomes. ANC provides a unique opportunity for birth preparedness by promoting healthy practices among pregnant women, improving nutrition, and preparing women mentally, physically and logistically for childbirth.25 This care can reduce the maternal death rate by up to 20%.23 Although there has been a shift from improving the coverage of healthcare to improving the quality of healthcare worldwide,26 there is a dearth of literature on the quality of maternal care for women with disabilities.27 28

Notably, women’s experiences of maternity care vary according to the type of impairment,18 29 where women with multiple disabilities are least satisfied with the care offered to them.18 Studies also show that women with disabilities who are living in rural areas and belong to poor socioeconomic strata may face greater challenges in accessing and utilisation of maternal healthcare services.30 31

Deeply rooted discriminatory attitudes and practices, as well as the lack of laws and policy enforcement, continue to violate the legitimate rights of people with disabilities.32–34 In addition, healthcare professionals may lack the knowledge and skills they need to provide care to pregnant women with disabilities.33 The international community has emphasised disability-inclusive health services by strengthening health systems to recognise and accommodate the needs of those with disabilities.35 36 To improve health outcomes for all women and children, there is a need to organise and deliver services that are technically appropriate, culturally acceptable, socially sensitive and equitably distributed to all women with and without disabilities.

Country context

With a population of 207 million,37 Pakistan failed to achieve optimal targets to reduce maternal and child mortality that were pledged under Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 by the United Nations.38 The country has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the world39 and is ranked unsafe for the survival of newborns.40 There are stark inequalities in maternal, reproductive, and child health indicators, and the situation among women who are uneducated, belong to the poorest wealth quintile and live in rural areas is far worse.41 42 The country is among the top 10 countries where healthcare interventions are the most inequitable.41 Although the general coverage of ANC from a skilled professional is quite high (86.2%) in Pakistan, most often all aspects of essential ANC are not included in the care provided to the pregnant women.42–44 Approximately 15% of childbearing women in Pakistan live with some disability;42 however, there is a dearth of literature on the challenges faced by these women living with disabilities. In Pakistan, the existing laws only focus on the rights and inclusion of persons with disabilities, in general.45 46 However, explicit policies around SRH needs, priorities and access to SRH education and services of disabled women are limited.

Research questions

Based on the aforementioned evidence, we hypothesise that the utilisation of essential ANC services will be lower among women with disabilities as compared with non-disabled women, women who are poor and living in the rural areas may be more deprived of these services as compared with urban and affluent segment, respectively. The specific research questions are as follows:

What are the levels of inequalities in the use of essential ANC services between women with and without disabilities, and by the type of disability?

How is the relationship between women’s disability and the utilisation of essential ANC antenatal moderated by women’s wealth status and place of (urban vs rural) residence?

Data and methods

Data

This study employed publicly available data from the most recent Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey collected in 2017–2018.42 With a stratified two-stage sample design, the survey obtained information from a nationally representative sample of the population of Pakistan.42 The response rate was 96%, and in the interviewed household, 94% of ever-married women age 15–49 were interviewed.

Sample derivation

A total of 15 068 ever-married women age 15–49 were interviewed in-person at their homes in the survey. However, we reduced our sample to two levels in accordance with our study objectives and sample representativeness. At the first stage, women who resided in the Gilgit Baltistan (n=984) and Azad Jammu and Kashmir (n=1720) regions were excluded because these two regions used a separate sampling procedure and a separate weight, and could not be combined with the other regions.42 At the second stage, we excluded women (n=5561) who did not have a live birth in the 5 years before the survey. Consequently, we performed our analysis on an unweighted sample of 6803 women (weighted sample 6711). Information about ANC was only collected and analysed for the most recent birth. We found less than missing cases in different disability variables that replace with ‘0’code, indicating no disability.

Variables

Dependent variables

The utilisation of essential ANC was the outcome variable for this study. The construction of outcome variables was guided by the WHO’s Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth guidelines, which detail the essential maternal health services that should be provided to women.47 For maternal healthcare-seeking, we used two measures: (1) received ANC and (2) completed four or more ANC visits. We also created an overall measure to ascertain if the women received all the essential components of ANC.47 These components were classified as: (1) Counselling as (A) received advice on early initiation of breast feeding, (B) received advice on exclusive breast feeding and (C) received advice on maintaining a balanced diet during pregnancy; (2) Examination as (A) blood pressure measurement, (B) blood test and (C) urine test; and (3) Treatment as (A) received two or more tetanus toxoid (TT) injections during pregnancy and (B) took iron tablets or syrup. For the overall measure of utilisation of essential components of ANC, women were coded with a ‘1’ if they had received all eight essential ANC components and ‘0’ otherwise.

Independent variables

A standard disability module was administered for collecting information on the six core functional domains of disability that included seeing, hearing, communication, cognition, walking and self-care. This questionnaire about disability was originally developed by the Washington Group on Disability.48 The module was based on the framework of the WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. The response to each question was classified as 0=no difficulty, 1=some difficulty, 2=a lot of difficulty or 3=cannot function at all in the specified domain. Women experiencing ‘no difficulty’ were considered as non-disabled; ‘some difficulty’ were classified as at risk of disability; and finally, ‘a lot of difficulty’ and ‘cannot function at all’ were classified as women with disability.

In accordance with the guidelines of Washington Group,48 we constructed an ordinal measure depicting the overall status of disability following three steps: (A) women who reported ‘a lot of difficulty’ or ‘cannot functional at all’ in any of the six domains were classified as women with disability; (B) of the remaining sample, women reported ‘some difficulty’ in one or more domains were classified as at risk of disability and (C) rest were considered as non-disabled women (ie, women who reported ‘no difficulty’ across all six domains).

Covariates

We included a range of covariates in our analysis that had the potential to be confounders. These included women’s age in three distinct categories (age 15–24, 25–34 and 35–49), place of residence (urban/rural), women’s education (no formal education/any formal education), women with first pregnancy–primigravida (yes/no) and wealth quintile (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest). The wealth index was computed by the DHS programme with principal component analysis.49

Effect modifiers

To develop a deeper understanding of the relationship between the status of functional disability and ANC, we performed subgroup analysis by wealth status and place of residence, and assessed if the disability–ANC relationship differed by place of residence and socioeconomic status. The wealth quintile variable was dichotomised into poor and non-poor, with women belonging to ‘poorest’ or ‘poorer’ quintiles grouped and coded as ‘0’, and the ‘middle’, ‘richer’ and richest’ grouped and coded as ‘1’. Similar categorisation of wealth quintile has also been reported in other researches.50 51

Statistical analysis

We performed the statistical analyses in different phases: descriptive, bivariate and multivariate analysis. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the socio demographic characteristics of the sample by means, SD, frequencies and percentages. We estimated the percentage (95% CIs) of overall disability and for each of the six domains of functional disability, and the percentage (95% CIs) utilisation of each essential ANC component. Next, we used Pearson’s χ2 to test if the percentage of disability varied by the wealth status and place of residence.

Second, we ran the bivariate analysis with the Pearson’s chi-square test to determine the crude association between utilisation of ANC and the women’s disability status.

In the third phase, we fitted separate multivariate logistic regression models to examine the relationship between disability and each ANC outcome in the overall sample, and then by place of residence (urban/rural) and wealth status (poor/non-poor). A series of models were fit separately on the full dataset, and the urban–rural and poor-non-poor subgroups. Finally, to ascertain the role of place of residence and wealth status as effect modifiers, we developed separate logistic regression models to test interactions of the disability measures with place of residence (urban/rural) and wealth status (poor/non-poor). The multivariate models also accounted for other covariates such as age, education, place of residence, primigravida and wealth quintile to produce adjusted ORs (aOR).

The data were analysed with Stata V.16.0 (StataCorp). All analyses were adjusted for the complex survey design, strata, primary sampling units (clusters) and probability sampling using individual weights. We used svy: commands as a prefix for cross-tabulations and logistic regression models. In the survey settings, we used ‘singleunit(centred)’ option, which specifies that strata with a single Primary Sampling Unit be centred at the grand mean instead of stratum mean. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

The method section is organised in accordance with Preferred Reporting items for Complex Sample Survey Analysis guidelines.52

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

Characteristics of study population

Table 1 shows the background characteristics of the 6711 women age 15–49 who had a live birth in the 5 years before the survey for overall sample and according to the disability status. Overall, nearly two-thirds (66.5%) of the women lived in rural areas. The mean age of women was 29.6 (SD=6.4) with more than half (55.5%) between age 25–34. Approximately half (47.9%) of the women had no formal education, and one in five women (19.9%) was primigravida. The segregated results showed that women with disabilities are relatively older, non-primigravida and belonged to poorer wealth quintile as opposed to their counterparts.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of women age 15–49 with a live birth in the 5 years before the survey

| Characteristics | Women without disabilities | Women at risk of any disability | Women with any disabilities | Overall sample | ||||

| n | n | N % | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Place of residence (p=0.44) | ||||||||

| Urban | 1912 | 33.2 | 282 | 36.4 | 54 | 31.3 | 2248 | 33.5 |

| Rural | 3852 | 66.8 | 492 | 63.6 | 119 | 68.7 | 4463 | 66.5 |

| Women’s age (p≤0.000) | ||||||||

| 15–24 | 1429 | 24.8 | 92 | 11.9 | 25 | 14.2 | 1545 | 23.0 |

| 25–34 | 3241 | 56.2 | 399 | 51.6 | 85 | 49.2 | 3725 | 55.5 |

| 35–49 | 1094 | 19.0 | 283 | 36.6 | 63 | 36.6 | 1440 | 21.5 |

| Mean (SD) | 28.9 | (6.1) | 32.0 | (6.5) | 32.3 | (6.8) | 29.6 | (6.4) |

| Education (p=0.1486) | ||||||||

| No formal education | 2775 | 48.1 | 340 | 44.0 | 97 | 56.0 | 3212 | 47.9 |

| Any formal education | 2989 | 51.9 | 434 | 56.0 | 76 | 44.0 | 3499 | 52.1 |

| Primigravida (p≤0.001) | ||||||||

| Yes | 4542 | 78.8 | 676 | 87.3 | 156 | 90.3 | 1337 | 19.9 |

| No | 1222 | 21.2 | 98 | 12.7 | 17 | 9.7 | 5374 | 80.1 |

| Wealth quintile (p≤0.002) | ||||||||

| Poorest | 1278 | 22.2 | 125 | 16.1 | 42 | 24.1 | 1444 | 21.5 |

| Poor | 1072 | 18.6 | 195 | 25.2 | 32 | 18.5 | 1299 | 19.4 |

| Middle | 1151 | 20.0 | 175 | 22.7 | 45 | 25.7 | 1371 | 20.4 |

| Richer | 1136 | 19.7 | 175 | 22.6 | 39 | 22.3 | 1349 | 20.1 |

| Richest | 1127 | 19.6 | 105 | 13.5 | 16 | 9.4 | 1248 | 18.6 |

| Total | 5764 | 100.0 | 774 | 100.0 | 173 | 100.0 | 6711 | 100.0 |

Status of functional disability

Figure 1 presents the percentage of overall functional disability and by each domain. About 11.5% (95% CI 10.3% to 13.0%) of the women had at risk of disability in one or more domains, while 2.6% (95% CI 2.1% to 3.2%) were living with disability (either have a lot of difficulty or cannot function at all) in at least one of the specified domains. With regard to the risk of disability, the most prevalent forms of functional disabilities were vision (6.1%, 95% CI 5.2% to 7.2%), cognition (4.2%, 95% CI 3.4% to 5.2%), walking (3.7%, 95% CI 3.0% to 4.4%) and hearing (1.6%, 95% CI 1.2% to 2.1%), while fewer than 1% were at risk of disability in the domain of self-care and communication. In terms of the experiencing disability, the most commonly cited domain was walking disability at 1.2% (95% CI 0.8% to 1.6%). The percentage of women living with disability in other domains was less than 1%.

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of women age 15–49 years with a live birth in the 5 years before the survey who are at risk and living with any functional disability, according to the domains (n=6711).

A comparison of functional disability between urban and rural, and poor and non-poor segments of the population is shown in table 2. The percentage of functional disability does not differ significantly according to the place of residence or wealth status of the household. The only exception was that the women who live in urban areas (5.0%) and those who are non-poor (4.4%) had significantly higher percentage of walking disability as compared with women living in rural areas (3.0%) and those who are poor (2.6%), respectively.

Table 2.

Proportion of functional disability among women who had a live birth in 5 years before the survey, according to wealth status and place of residence

| Characteristics | Overall disability | Vision | Cognition | Mobility | No of women | ||||

| At risk of any disability | With any disability | At risk | Disabled | At risk | Disabled | At risk | Disabled | ||

| Pooled estimates | |||||||||

| Percentage | 11.5 | 2.6 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 6711 |

| Wealth status | |||||||||

| Poor | 11.7 | 2.7 | 6.4 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 2743 |

| Non-poor | 11.5 | 2.5 | 6.0 | 0.9 | 3.8 | 0.7 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 3968 |

| P value | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.34 | 0.04 | |||||

| Place of residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 12.5 | 2.4 | 6.8 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 1.1 | 2248 |

| Rural | 11.0 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 4463 |

| P value | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |||||

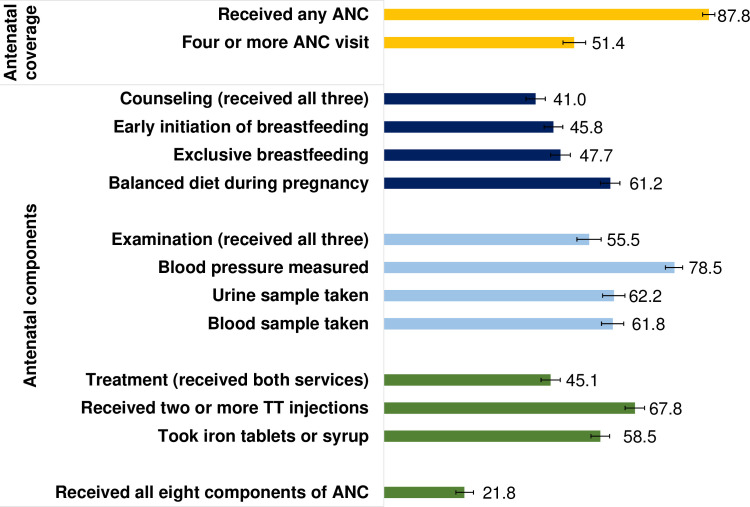

Utilisation of essential antenatal services

Figure 2 presents ANC coverage and the receipt of essential ANC components among the sampled women. Nearly 9 in 10 women received any ANC and half (51.4%) completed four or more ANC visits. Three in five (61.2%, 95% CI 58.5% to 63.8%) women reported receiving advice on maintaining a balanced diet during pregnancy, while fewer than half received counselling on the early initiation of breast feeding (45.8%, 95% CI 43.3% to 48.3%) and exclusive breast feeding (47.7%, 95% CI 45.1% to 50.4%). About 41% (95% CI 38.4% to 43.6%) received counselling on all three components. With ANC visits, approximately 78.5% (95% CI 76.1% to 80.7%) had their blood pressure checked, while urine and blood samples were taken from approximately three in five women. Just over half (55.5%, 95% CI 52.2% to 58.7%) of the women reported receiving all three examination components. Fewer than half of the women (45.1%, 95% CI 42.5% to 47.7%) received the recommended doses of TT and consumed iron tablets or syrup during pregnancy. Only one in five women (21.8%, 95% CI 19.5% to 24.2%) received all eight components of ANC during pregnancy.

Figure 2.

Utilisation of essential ANC components among women age 15–49 with a live birth in the 5 years before the survey. ANC, antenatal care.

Inequalities in utilisation of essential ANC services between women with and without disability

Table 3 shows the results of the overall analysis from bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis in the form of crude percentages and aORs. Column 2 in the table shows the percentage of outcomes among women with disability, at risk of disability and non-disabled women. These models were adjusted for the range of covariates as described in the analysis section above. The overall measures of disability showed no association with the ANC coverage indicators. However, we found a positive association between disability status and uptake of certain ANC components. Women with disability in at least one domain had 1.7 times the odds (AOR 1.7, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.7; p<0.05) of taking a urine test, and 1.6 times the odds (AOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.4; p<0.05) of receiving advice of about exclusive breast feeding as opposed to the non-disabled women. Similarly, as compared with non-disabled women, those women who are at risk of disability in one or more domains had 30% (AOR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.7; p<0.05) greater odds of receiving advice on maintaining a balanced diet during pregnancy. The only exception was that women with disability in one or more domain were 40% less likely to consume iron tablets or syrup (AOR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4 to 0.9) as compared with their counterparts.

Table 3.

Inequalities in the uptake of essential ANC services between women with and without disabilities

| Variables | Full dataset | |

| Percentage of outcome | AOR (95% CI) | |

| ANC coverage | ||

| Received ANC (Ref. non-disabled) | 87.8 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 89.5 | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.8) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 88.2 | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.7) |

| 4+ANC visits (Ref. non-disabled) | 51.4 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 48.9 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 54.1 | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.3) |

| Treatment | ||

| Received two or more tetanus toxoid injections (Ref. non-disabled) | 67.8 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 70.8 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 69.8 | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.3) |

| Took iron tablets or syrup (Ref. non-disabled) | 59.2 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 56.0 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 45.6* | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9)* |

| Examination | ||

| Blood pressure measured (Ref. non-disabled) | 78.5 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 78.3 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 77.7 | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.9) |

| Urine sample taken (Ref. non-disabled) | 62.2 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 59.7 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 68.4 | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.7)* |

| Blood sample taken (Ref. non-disabled) | 62.1 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 60.6 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 57.4 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) |

| Counselling | ||

| Advice on early initiation of breast feeding (Ref. non-disabled) | 45.8 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 46.4 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 49.9 | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.2) |

| Advice on exclusive breast feeding (Ref. non-disabled) | 47.7 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 48.1 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 54.8 | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.4)* |

| Advice on maintaining balanced diet during pregnancy (Ref. non-disabled) | 60.4 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 66.3 | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7)* |

| Disability in one or more domains | 62.1 | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.0) |

| Received all essential ANC components (Ref. non-disabled) | 22.1 | 1 |

| At risk of disability in one or more domains | 19.8 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Disability in one or more domains | 20.8 | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) |

*p<0.05

The results of subgroup analysis from bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis are presented in online supplemental file 1, the key findings, however, are narrated here. With the exception of the use of iron tablets, none of the interaction terms in the full model was found to be significant, which suggests that the relationship between disability and utilisation of ANC does not differ by wealth status and place of residence. Women with disabilities had significantly lower odds of consuming iron tablets or syrup as compared with their counterparts both in rural (AOR 0.54, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.8; p<0.05) and poor (AOR 0.32, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.7; p<0.01) segment of population. The similar relationship consumption of iron tablets or syrup held true for the measure of t risk of disability in one or more domains (AOR 0.72, 95% CI 0.5 to 1.0; p<0.05) both in non-poor segments of population and those living in urban areas (AOR 0.67, 95% CI 0.5 to 1.0; p<0.05).

bmjopen-2023-074262supp001.pdf (35.5KB, pdf)

Among the poor segment of the population, women at risk of disability in one or more domain had a significantly greater (AOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.2; p<0.05) odds of receiving ANC and had 60% (AOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.2; p<0.05) greater odds of receiving advice on maintaining a balanced diet during pregnancy as opposed to their counterparts. Similar, in non-poor segment of population, women with disability in one or more domains were twice as likely to have their urine sample taken (AOR 2.1, 95% CI 1.0 to 4.1; p<0.05) and were given advice on exclusive breast feeding (AOR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.0; p<0.05) as opposed to their counterparts. We observed similar findings in the urban-rural subgroup analysis. Among the rural segment of population, women who have at risk of disability in one or more domains had 41% (AOR 1.41, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.9; p<0.05) greater odds of receiving advice on maintaining a balanced diet during pregnancy.

Discussion

Women with disabilities have been an invisible population in maternity care and reproductive health. Globally, there is a dearth of empirical literature on the maternal and reproductive health needs of women with disabilities, particularly in LMICs. Our study is one of the first of its kind to examine inequalities in the utilisation of essential ANC services between women with and without disabilities in Asia. This study found that a substantial proportion (11.5%) of women of childbearing age have some level of difficulty in at least one domain of disability, while 2.6% have a lot of difficulty or cannot function at all. A multicountry study conducted in Africa had reported the percentage of functional disabilities for women age 15–39 and 40–49. Among women age 15–39, the percentage of any severe disability was estimated to be around 0.5%–1.3% and 5.9%–7.6% for any moderate or severe disability, while among women age 40–49, the percentage ranged from 1.2%–3.8% to 15.3%–21.9%, respectively.53 The percentage of disability among women of reproductive age in Pakistan is similar to other LMICs. In contrast, studies from the USA and UK reported that 12%54 and 6.1%55 of women of reproductive age are disabled (any disability), respectively. This indicated that the percentage of disability among women of childbearing age in Pakistan is relatively lower than in high-income countries. Consistent with trends in other countries,53 the most common forms of functional disabilities were related to vision (at risk=6.1%, disabled=0.8%), walking (at risk=3.7%, disabled=1.2%) and cognition (at risk=4.2%, disabled=0.6%), while difficulty in communicating was the least prevalent.

Our study revealed that women with disabilities were relatively older and non-primigravida as opposed to their counterparts. These findings are consistent with other countries such as Nepal56 and England.18 We observed no clear trend of disability with wealth status. However, some studies have found that poor people are more likely to have disability due to factors such as ill health, malnourishment, unsafe work and the inability to afford medical care that may prevent disability.57 58 We found no significant differences in the percentage of functional disability by urban–rural residence. The only exception was the domain of walking disability, which was more commonly found in urban areas as compared with the rural areas. One study in African countries also reported varying patterns in the percentage of urban–rural disabilities across countries.53 However, another recent study from the USA found a significantly higher percentage of disability in rural settings versus the urban areas.59 Comparisons should be made with caution because these studies reported disability for either the adult (USA) or the entire population (African countries), whereas our estimates are based on childbearing women.

Notably, in this study, 88% of women sought ANC but only 20% received all eight essential ANC components. In Pakistan, there has been a significant increase in the coverage of several maternal and newborn healthcare services. However, this increase hasn’t proportionally translated into reduction in maternal and neonatal mortality—primarily due to inequalities in service coverage and inconsistent quality of services.39 42 60 This stark difference clearly highlights a critical gap in the quality of ANC in our healthcare system, a gap that requires urgent interventions to improve the quality of healthcare services. Furthermore, understanding the underlying causes and implications of these differences require nuanced quality research using the principles of implementation research. Health inequalities including utilisation of ANC among women with disabilities are common across the globe.2 However, our study could not find major inequalities in the utilisation of ANC by disabled women in Pakistan. We found limited evidence of the association between functional disability and utilisation of ANC services. Although we were unable to locate any comparable study, this finding is in agreement with a systematic review from LMICs that found no difference in coverage of maternal health services between women with and without disabilities.8 The same association has also been documented in other studies conducted in India, Cameroon, Sierra Leone and UK where utilisation of maternal and reproductive health services were not different in women with and without disability.18–21 55 In contrast, some studies from African region (Ghana, Uganda and Senegal) and rural Pakistan did identify a range of challenges faced by women with disabilities in accessing reproductive health services.31 61–63 This mixed evidence in inequalities with disabled women requires in-depth exploration so as to understanding why women with disabilities received discriminatory care in one setting and not in other settings. The rights of people living with disabilities are reflected in national policies and legislations which covers a comprehensive range of facilities and services for people with disabilities—from prenatal care to the advanced levels of healthcare. For instance, the policy proclaimed that disabled people are equally entitled to the opportunities as other non-disabled have in all spheres of life. However, implementation is these policies to ensure provision of disability-inclusive services is identified as a challenge.63–65

We found significant underutilisation of iron tablets or syrup by women with disability as compared with their counterparts. Among all the ANC components, consumption of iron tablets/syrup relies on the women’s choice to take the iron rather than receiving a prescription by a service provider. This suggests that women with disabilities tend to struggle adhering to a provider’s suggestion to take iron tablets/syrup on their own. This was suggested in another study that found lower adherence among people with disabilities.8 It may also be possible that fewer women with disability were prescribed medication by their service providers. From the programmatic perspective, we suggest that during consultations, service providers might also inform the accompanying person or other members of household about the medication and encourage the women to take their medication.

In some cases, women with certain functional disabilities have reported higher utilisation of ANC components such as advice on exclusive breast feeding and maintenance of a balanced diet during pregnancy as compared with non-disabled women. This could be due to the fact that in general, women with disabilities are considered high risk during their pregnancy11 and require more ANC and medical examinations than non-disabled women.66 This could also be explained by sympathetic behaviour of healthcare providers towards women with disabilities.63 It is also pertinent to note that, in rare instances, this sympathetic behaviour may be perceived as patronising by women when they desire to be cared for in a similar, if not identical, manner to those without disability. This could lead to a sense of being singled out and labelled as high risk on account of their disability when it is not medically indicated.67 A study from Nepal also found that the attitude of healthcare providers towards the disabled was negative and that the providers had limited knowledge and skills about providing services for the disabled. Few participants reported that the attitude of healthcare providers was kind, respectful, caring or helpful towards women with disabilities.68 Furthermore, women living with disabilities in Pakistan receive social and economic support from family members, neighbours and society, which may encourage them to seek better ANC. Redshaw et al reported that women with disabilities in the UK use maternity services more than non-disabled women and had sufficient access and involvement in maternity care services.18 Thus, there are conflicting arguments about the health service utilisation by women with disabilities. When there is a good health infrastructure, women with disabilities may benefit even more from health systems than women with no disabilities. We noticed that this trend of higher utilisation of ANC services was primarily found in ANC counselling, in the overall analysis as well as among the poor population and those who reside in the rural areas. This pattern of favourable care for women living with disabilities could also be attributed to the active involvement of community health workers (officially called the lady health workers (LHWs)) who are responsible for providing basic maternal and child healthcare services (including ANC counselling) during their routine household visits.69 The LHWs are residents of the same community and can relate to other women and navigate local norms, languages and social relationships more effectively than outsiders.70

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that specifically examined the relationship between disability and utilisation of ANC services, particularly among LMICs. The results are based on the most recent national survey in Pakistan. Our study presents a comprehensive analysis of the disability–ANC relationship that used numerous independent and dependent variables, and performed subgroup analyses.

Our study has some limitations. First, since the analysis used cross-sectional data, we cannot draw inferences about causal relationships between disability and ANC. Second, since we excluded two regions because their use of a different sampling frame, our findings cannot be generalised to the excluded regions, and they are not representative of Pakistan as a whole. The few significant disability–ANC associations in the subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution because the unweighted cell count was less than 25 or 50. Moreover, we did not include the association between each domain of any disability (eg, vision, walking and cognition) with ANC outcomes due to low percentage. Furthermore, the survey did not collect information on length of disability hence it was not possible to ascertain whether a woman was disabled during the antenatal period. Finally, the focus of our study was utilisation of essential ANC services, while the interpersonal aspects of care such as the social and emotional support extended to women by the service providers were not included and are also important to consider.

Conclusions

Pakistan has a considerable population of disabled women in reproductive age. The percentage of disability does not differ linearly by wealth quintile (highest among poorest and lowest among richest) or urban–rural geographies. Overall, the proportion of effective ANC coverage is very low and requires urgent measures for quality improvement. Our analyses indicate that the utilisation of essential ANC services among women with disabilities is not different or lower than non-disabled women. This pattern is seen for urban-rural geographies and among the poor-non-poor segments of the population. It seems that the country’s health system, to a great extent, is responsive to the needs of women with disabilities for ANC services. However, adherence to medication (in this study, iron tablets/syrup) may be challenging for women with disabilities and could be improved by engaging a companion from same household to encourage compliance. Moving forward, there is a need in Pakistan to conduct qualitative studies that enhance our understanding of how our health system is meeting the unique needs of women with disabilities, to develop greater insights into how the psychosocial needs of women with disabilities are addressed during the provision of care, and to replicate disability-inclusive best practices in a broader context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Shireen Assaf as mentor and Christina Juan as a co-mentor of the 2020 DHS Fellows Program for their technical support. We are thankful to United States Agency for International Development for funding our research through the DHS Fellows Program, which is implemented by ICF. Lastly, we express our gratitude to our reviewer Courtney Allen for her valuable insights, and thanks to the editor and formatter who supported us in finalising the report.

Footnotes

Contributors: WH and MA conceptualised the study under the guidance and supervision of BIA and SS. WH and MA analysed the data. WH and MA wrote the first and final draft and prepared tables. BIA supervised data analysis, and both BIA and SS critically reviewed the manuscript and provided comprehensive feedback for improvements. WH revised the draft based on BIA and SS feedback. All authors read and approved the manuscript. WH is the overall content guarantor.

Funding: United States Agency for International Development (grant number: N/A).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. We study used analysis of secondary data which is publicly available from the Demographic Health Survey website. URL: https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not required.

References

- 1.Bickenbach J. The world report on disability. Disability & Society 2011;26:655–8. 10.1080/09687599.2011.589198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Disability and health - fact sheet. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization, World Bank . World report on disability. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitra S. The capability approach and disability. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 2006;16:236–47. 10.1177/10442073060160040501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) . Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and optional protocol. New York: United Nation, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacKay D. The United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce 2007;34:323–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banks LM, Kuper H, Polack S. Poverty and disability in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018;13:e0204881. 10.1371/journal.pone.0204881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bright T, Kuper H. A systematic review of access to general healthcare services for people with disabilities in low and middle income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1879. 10.3390/ijerph15091879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackford KA, Richardson H, Grieve S. Prenatal education for mothers with disabilities. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:898–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frohmader C, Ortoleva S. Issues paper: the sexual and reproductive rights of women and girls with disabilities. International Conference on Human Rights; 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh-Gallagher D, Sinclair M, Mc Conkey R. The ambiguity of disabled women’s experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood: a phenomenological understanding. Midwifery 2012;28:156–62. 10.1016/j.midw.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund . Promoting sexual and reproductive health for persons with disabilities: WHO/UNFPA guidance note. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rugoho T, Maphosa F. Challenges faced by women with disabilities in accessing sexual and reproductive health in Zimbabwe: the case of Chitungwiza town. Afr J Disabil 2017;6:252. 10.4102/ajod.v6i0.252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawler D, Lalor J, Begley C. Access to maternity services for women with a physical disability: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Childbirth 2013;3:203–17. 10.1891/2156-5287.3.4.203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang K, Johnston M, Tulsky D, et al. Access and coordination of health care service for people with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 2009;20:28–34. 10.1177/1044207308315564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganle JK, Baatiema L, Quansah R, et al. Barriers facing persons with disability in accessing sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020;15:e0238585. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malouf R, Henderson J, Redshaw M. Access and quality of maternity care for disabled women during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period in England: data from a national survey. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016757. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redshaw M, Malouf R, Gao H, et al. Women with disability: the experience of maternity care during pregnancy, labour and birth and the postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:174. 10.1186/1471-2393-13-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmood S, Hameed W, Siddiqi S. Are women with disabilities less likely to utilize essential maternal and reproductive health services? – a secondary analysis of Pakistan demographic health survey. PLoS ONE 2022;17:e0273869. 10.1371/journal.pone.0273869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trani J-F, Browne J, Kett M, et al. Access to health care, reproductive health and disability: a large scale survey in Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:1477–89. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeBeaudrap P, Mouté C, Pasquier E, et al. Disability and access to sexual and reproductive health services in Cameroon: a mediation analysis of the role of socioeconomic factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:417. 10.3390/ijerph16030417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN maternal mortality estimation inter-agency group. Lancet 2016;387:462–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikiema L, Kameli Y, Capon G, et al. Quality of antenatal care and obstetrical coverage in rural Burkina Faso. J Health Popul Nutr 2010;28:67–75. 10.3329/jhpn.v28i1.4525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhnt J, Vollmer S. Antenatal care services and its implications for vital and health outcomes of children: evidence from 193 surveys in 69 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017122. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekabua J, Ekabua K, Njoku C. Proposed framework for making focused Antenatal care services accessible: a review of the Nigerian setting. ISRN Obstet Gynecol 2011;2011:253964. 10.5402/2011/253964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. The Lancet Global Health 2018;6:e1196–252. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thierry JM. Promoting the health and wellness of women with disabilities. J Womens Health 1998;7:505–7. 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrison J, Basnet M, Budhathoki B, et al. Disabled women’s maternal and newborn health care in rural Nepal: a qualitative study. Midwifery 2014;30:1132–9. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Homer CSE, Malata A, Ten Hoope-Bender P. Supporting women, families, and care providers after stillbirths. Lancet 2016;387:516–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01278-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganle JK, Otupiri E, Obeng B, et al. Challenges women with disability face in Accessing and using maternal Healthcare services in Ghana: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158361. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahumuza SE, Matovu JKB, Ddamulira JB, et al. Challenges in accessing sexual and reproductive health services by people with physical disabilities in Kampala, Uganda. Reprod Health 2014;11:59. 10.1186/1742-4755-11-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephanie O, Sisters LHF. Forgotten sisters - a report on violence against women with disabilities: an overview of its nature, scope, causes and consequences. Northeastern University School of Law Research Paper, No. 104. Boston, MA, USA: Northeastern University School of Law, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipson JG, Rogers JG. Birth, and disability: women’s health care experiences. Health Care Women Int 2000;21:11–26. 10.1080/073993300245375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prilleltensky O. A ramp to motherhood: the experiences of mothers with physical disabilities. Sex Disabil 2003;21:21–47. 10.1023/A:1023558808891 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Achu K, Al Jubah K, Brodtkorb S, et al. Community-based rehabilitation: CBR guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa-De-Araujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health 2015;105 Suppl 2:S198–206. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pakistan Bureau of Statistics . 6th population and housing census - 2017. Islamabad: Ministry of Statistics, Government of Pakistan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Victora CG, Requejo JH, Barros AJD, et al. Countdown to 2015: a decade of tracking progress for maternal, newborn, and child survival. Lancet 2016;387:2049–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00519-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institute of Population Studies Pakistan, Macro International Inc . Pakistan demographic and health survey 2006-7. Islamabad: Government of Pakistan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN inter-agency group for child mortality estimation. Lancet 2015;386:2275–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00120-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barros AJD, Ronsmans C, Axelson H, et al. Equity in maternal, newborn, and child health interventions in countdown to 2015: a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet 2012;379:1225–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60113-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and ICF . Pakistan demographic and health survey 2017-18. Islamabad, Pakistan and Rockville,Maryland, USA: NIPS and ICF, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tappis H, Kazi A, Hameed W, et al. The role of quality health services and discussion about birth spacing in postpartum contraceptive use in Sindh, Pakistan: a multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0139628. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hameed W, Avan BI. Women's experiences of mistreatment during childbirth: a comparative view of home- and facility-based births in Pakistan. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194601. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The Institute for Social Justice . Situation of women, children and minorities with disability in Pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan: The Institute for Social Justice, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ministry of Human Rights . National assembly bill, Pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Assembly of Pakistan, 2021: 7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, UNICEF . Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care: a guide for essential practice 3rd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Madans JH, Loeb ME, Altman BM. Measuring disability and monitoring the UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: the work of the Washington group on disability Statistics. BMC Public Health 2011;11 Suppl 4:S4. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S4-S4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. DHS comparative reports 6: the DHS Wealth Index. 2004. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ndwandwe D, Uthman OA, Adamu AA, et al. Decomposing the gap in missed opportunities for vaccination between poor and non-poor in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicountry analyses. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018;14:2358–64. 10.1080/21645515.2018.1467685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fagbamigbe AF, Kandala NB, Uthman OA. Mind the gap: what explains the poor-non-poor inequalities in severe wasting among under-five children in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE 2020;15:e0241416. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seidenberg AB, Moser RP, West BT. Preferred reporting items for complex sample survey analysis (PRICSSA). J Surv Stat Methodol 2023;00:1–15. 10.1093/jssam/smac040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitra S. Disability, health and human development. In: Mitra S, ed. Prevalence of functional difficulties. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2018: 61–88. 10.1057/978-1-137-53638-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults--United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:421–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murthy GVS, John N, Sagar J, et al. Reproductive health of women with and without disabilities in South India, the SIDE study (South India disability evidence) study: a case control study. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:146. 10.1186/s12905-014-0146-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Devkota HR, Murray E, Kett M, et al. Are maternal Healthcare services accessible to vulnerable group? A study among women with disabilities in rural Nepal. PLoS ONE 2018;13:e0200370. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson S. Disability prevalence and trends. United Kingdom: Institute of Development Studies, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Plantinga LC, Johansen KL, Schillinger D, et al. Lower socioeconomic status and disability among US adults with chronic kidney disease, 1999-2008. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:E12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao G, Okoro CA, Hsia J, et al. Prevalence of disability and disability types by urban-rural County classification-U.S., 2016. Am J Prev Med 2019;57:749–56. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and ICF . Pakistan maternal mortality survey 2019. Islamabad, Pakistan, Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPS and ICF, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ganle JK, Otupiri E, Obeng B, et al. Challenges women with disability face in accessing and using maternal Healthcare services in Ghana: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2016;11:e0158361. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burke E, Kébé F, Flink I, et al. A qualitative study to explore the barriers and enablers for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in Senegal. Reprod Health Matters 2017;25:43–54. 10.1080/09688080.2017.1329607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ahmad M. Health care access and barriers for the physically disabled in rural Punjab. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 2013;33:246–60. 10.1108/01443331311308276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahmed M, Khan AB, Nasem F. Policies for special persons in Pakistan: analysis policy implementation. Berkeley Journal of Social Sciences 2011;1. Available: https://www.humanitarianlibrary.org/sites/default/files/2014/02/Feb%201.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 65.Razzaq S, Rathore FA. Disability in Pakistan: past experiences, current situation and future directions. J Pak Med Assoc 2020;70:2084–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mitra M, Clements KM, Zhang J, et al. Maternal characteristics, pregnancy complications, and adverse birth outcomes among women with disabilities. Med Care 2015;53:1027–32. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blair A, Cao J, Wilson A, et al. Access to, and experiences of, maternity care for women with physical disabilities: a scoping review. Midwifery 2022;107:103273. 10.1016/j.midw.2022.103273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Devkota HR, Murray E, Kett M, et al. Healthcare provider’s attitude towards disability and experience of women with disabilities in the use of maternal healthcare service in rural Nepal. Reprod Health 2017;14:79. 10.1186/s12978-017-0330-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.World Health Organization, Global Health Workforce Alliance . Country case study: Pakistan’s Lady Health Worker Programme. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mumtaz Z, Salway S, Nykiforuk C, et al. The role of social geography on Lady health workers' mobility and effectiveness in Pakistan. Soc Sci Med 2013;91:48–57. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-074262supp001.pdf (35.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. We study used analysis of secondary data which is publicly available from the Demographic Health Survey website. URL: https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.