Abstract

Higher numbers of donor plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) increased survival and reduced graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) in human recipients of unrelated donor bone marrow (BM), but not G-CSF peripheral blood grafts. In murine models, we have shown that donor BM pDC increase survival and decrease GvHD compared to G-CSF-mobilized pDC. To increase the content of pDC in BM grafts we studied the effect of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) treatment of murine BM donors on transplant outcomes. Flt3L treatment (300μg/kg/day) resulted in a schedule-dependent increase in the content of pDC in the marrow. Mice treated on days −4 and −1 had > 5-fold increase in pDC content without significant changes in numbers of HSC, T cells, B cells, and NK cells in the marrow graft. In an MHC mismatched murine transplant model, recipients of Flt3L-treated T-cell depleted BM (F-TCD BM) and cytokine-untreated T cells had increased survival and decreased GvHD scores with fewer Th1 and Th17 polarized T cells post-transplant compared with recipients of equivalent numbers of untreated donor TCD BM and T cells. Gene array analyses of pDC from Flt3L-treated human and murine donors showed upregulation of adaptive immune pathways and immunoregulatory checkpoints compared with pDC from untreated BM donors. Transplantation of F-TCD BM plus T cells resulted in similar tumor burden and prolonged survival compared with grafts from untreated donors in two murine GvL models. Thus, Flt3L treatment of marrow donors is a novel method to increase the content of pDC in allografts, increase survival, and decrease GvHD without diminishing the GvL effect.

Keywords: Plasmacytoid dendritic cells, Flt3L, Allogeneic Transplant, GvHD, GvL

INTRODUCTION

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is curative for patients with hematological malignances and bone marrow failure disorders.1 HSC grafts are typically obtained from aspiration of bone marrow (BM) or from apheresis of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) mobilized peripheral blood.2, 3 The major complications of allo-HSCT including graft rejection, disease relapse, and graft-versus-host disease (GvHD).4, 5 These adverse effects are initiated and regulated by both the content of donor immune cells in the graft and residual antigen presenting cells in the recipient.6 Results of BMTCTN 0201 showed that an increased content of donor plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) in BM allografts increased survival and decreased GvHD, but not in G-CSF mobilized (G-mobilized) allografts.7 It has been reported that dendritic cell reconstitution post-transplant predicts outcomes including incidence of GvHD, relapse and death.8 We have observed that transplantation of purified BM pDC increased survival and decreased GvHD without affecting graft-versus-leukemia (GvL) in allogeneic murine transplant models compared to G-mobilized pDC (Hassan, 2018, submitted). Because pDC content of the marrow is variable among allogeneic donors, methods to increase the pDC content in marrow are attractive strategies to enhance survival and GvL while limiting GvHD.

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells can be identified as Lin−(CD3, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD20) HLADR+CD123+CD11c−CD33− in humans and PDCA1+CD11c+B220+Lin−(CD3, CD11b, CD19, IgM, CD49b, Ter119) in mice.9, 10 (add see, peter, science, June 2017). Plasmacytoid dendritic cells play a significant role in both innate and adaptive immunity because they are the primary source of type 1 interferon in both humans and mice.11 Recipient pDC are depleted following irradiation, allowing for examination of the effect of donor pDC on post-transplant GvHD and GvL.12 Donor pDC have been shown to possess graft-facilitating functions including enhancing donor cell engraftment and survival post-transplant.13 The immunological status, inflammatory or immunosuppressive, of donor pDC that interact with donor T cells is paramount to their ability to limit GvHD.14 We have shown that pDC facilitate immunity through early post-transplant IL-12 secretion which enhances engraftment and GvL effect and late IFNγ response pathways that decrease GvHD via induction of IDO production and increased numbers of Treg.15–17

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) is necessary for pDC differentiation and Flt3L treatment can be used to increase pDC content in vitro.18–21 Although the use of CDX-301, a recombinant Flt3L, in mobilization of HSC has been studied, the effect of in vivo Flt3L administration alone on the content and immunological activity of pDC in bone marrow is yet to be determined.22, 23 We hypothesized that Flt3L treatment of bone marrow donors would increase the pDC content of the allograft and transplanting Flt3L-stimulated marrow grafts would enhance survival while limiting GvHD. We tested this hypothesis in an MHC mismatched C57BL/6➔B10.BR transplant model in which donors were treated with PBS or two injections of 300μg/kg of Flt3L. Herein, we report that treatment of donors with Flt3L increased the pDC content of the marrow graft, increased survival, and decreased GvHD in allo-transplant recipients compared to marrow grafts from PBS-treated donors. Additionally, we observed decreased Th1 and Th17 polarization in T cells recovered from FBM transplant recipients on day 3. Using FACS purified pDC, we show that Flt3L treatment of donors led to upregulation of adaptive immune pathways and immunoregulation checkpoints in donor pDC without a reduction in GvL effect. Therefore, Flt3L treatment is a novel method that increases pDC content in donor grafts, increases survival, and decreases GvHD in allogeneic transplantation.

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 (H-2Kb) and B10.BR (H-2Kk) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Male donor and recipient mice were 8–10 weeks and 10–12 weeks, respectively. National Institutes of Health animal care guidelines were used and approved by Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flt3L Treatment of Mice

C57BL/6 mice were treated with a variety of schedules of daily subcutaneous injections of PBS or 300μg/kg of recombinant human Flt3L (CDX-301) generously donated by CellDex Therapeutics (Hampton, NJ).

G-CSF Treatment

C57BL/6 mice were treated with five consecutive days of subcutaneous injections of PBS or 300μg/kg of recombinant G-CSF from Sandoz (Princeton, NJ).

Donor Cell Preparation

Donor mice were euthanized and femora and tibias of donor C57BL/6 mice were flushed with 2% FBS PBS. Biotinylated anti-mouse CD3 from BD Bioscience (San Jose, CA) was used for T cell depletion. T cell purification was performed by incubating with biotinylated B220, CD49b, Gr-1, Ter119 antibodies. T cell depletion and purification samples were then incubated with anti-biotin microbeads and negative selection with a LS Miltenyi MACS column was performed (Gladbach, Germany).

Flow Cytometry

Anti-mouse (CD3, CD11b, CD19, IgM, CD49b, Ter119) PE or CD11b PE-CY7, CD11c FITC or APC-CY7, B220 PERCP-CY5.5 and PDCA1 ef450 were used for pDC analysis and purchased from BD Bioscience (San Jose, CA), Biolegend (San Diego, CA), and eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Stimulation of pDC for cytokine profile analysis was done using 50μM of CpG (ODN 1585, Invivogen, San Diego, CA) of whole bone marrow in complete RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100μg/mL of streptomycin, and 50μM each of 2-mercaptoethonaol, nonessential amino acids, HEPES, and sodium pyruvate (complete media) in 10cm wells for 9 hours at 37°C. BD golgiplug was added at hour 3. Intracellular analysis of pDC was done using BD Bioscience cytofix/cytoperm kit and anti-mouse IDO PerCP-Cy5.5, IFNα FITC, IL-10 PECY7 and IL-12 APC antibodies.

Splenocytes were stained using anti-mouse CD3 FITC, CD4 PE-CF594, CD8 PERCP-CY5.5, and CD25 APC-CY7. T cells were stimulated with BD leukocyte activation cocktail and golgiplug for 6 hours. Intranuclear staining was done using the eBioscience fixation kit and Tbet PE-CY7, GATA3 PE, RORγT APC, and FoxP3 PE antibodies. Data were acquired with a FACS Aria (BD, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, Oregon).

In vitro T cell Activation

MACS purified splenic T cells from C57BL/6 mice were cultured with 2μL of anti-CD3/28 Dynabeads per 106 T cells (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). A 1:2 ratio of PBS or Flt3L-treated pDC to T cells were incubated in 96 well plates in complete media for 72 hours at 37°C.

Transplantation

On day −1 recipients were irradiated twice at 5.5 Gy, with fractions separated by 3–4 hours, for a total of 11Gy.24 Mice were transplanted with 5 × 106 T cell depleted PBS or Flt3L-treated BM with or without 4 × 106 T cells on day 0. GvHD monitoring used a 10-point scoring system including weight, attitude/activity, skin condition, hunching, and coat condition.25

Tumor Cell Challenge and Bioluminescent Imaging

A generous gift by Dr. Bruce Blazar, an acute myeloid leukemia cell line, luciferase-transfected C1498, was used for graft-versus-leukemia experiments. On day 2, mice were lethally irradiated (11Gy), on day 1 injected with 50,000 C1498 cells, and on day 0 T cell depleted bone marrow or bone marrow from Flt3L treat bone marrow donors with or without untreated T cells were then transplanted. For bioluminescent imaging, 150μg/kg of D-Luciferin was injected and mice were imaged with IVIS spectrum (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Luminescence was measured in photons/sec/cm2 and normalized to control mice (recipients of the same transplant without luciferase+ tumor).

Gene Array Analysis

Human subjects were treated with 75μg/kg of Flt3L (CDX-301) for 5 consecutive days and underwent large volume leukapheresis as part of an IRB-approved clinical trial (Clinical trial NCT022000380). Bone marrow samples from volunteer donors were collected as part of a separate IRB-approved clinical study of immune cells in the marrow (NCT02485639). Gene expression of human BM and Ftl3L mobilized peripheral blood FACS isolated pDC was assessed using Illumina HumanHT-12 v4 beadchip microarray. Data was preprocessed, quantile normalized, background-corrected and log2 transformed for downstream analysis.26 RNASeq gene expression of murine BM and Flt3L-treated BM pDC was assessed. Preparation of cDNA was performed using the Takara SMART-Seq v4 low input RNA kit. The sequencing library was created using NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA kit. Samples were sequenced on next generation sequencing at 2 X 151 bp in the paired ends. Fastq reads were trimmed and filtered for quality and adapter contamination with trimmomatic. Post-filtered reads were mapped against Ensemble mouse GRCm38/mm10 reference genome and gencode Release M16 gene annotation using STARaligner. Sequencing results are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive, accession SRP155387. Expression quantification was obtained using HTSeq counts, DESeq normalized and log2 transformed for further analysis.27 Differential expression analysis for both human and murine samples was performed using a moderated t-test.26 Heatmaps were created using NOJAH (http://bbisr.shinyapps.winship.emory.edu/NOJAH/). Genes were determined to be significantly differentially expressed based on both a fold-change of 1.5 and an FDR cutoff of 0.05. Pathway analysis was performed using Cytoscape software v3.6.1 and ReactomeFI plugin.28, 29

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism version 5 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA) for MAC and are displayed as mean+SD unless otherwise specified. Survival differences were calculated in a pairwise fashion using the log-rank test. Applicable data were compared by student-test and 1-way ANOVA. Significance was considered as a p-value of ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Flt3L administration expands pDC content in bone marrow in vivo

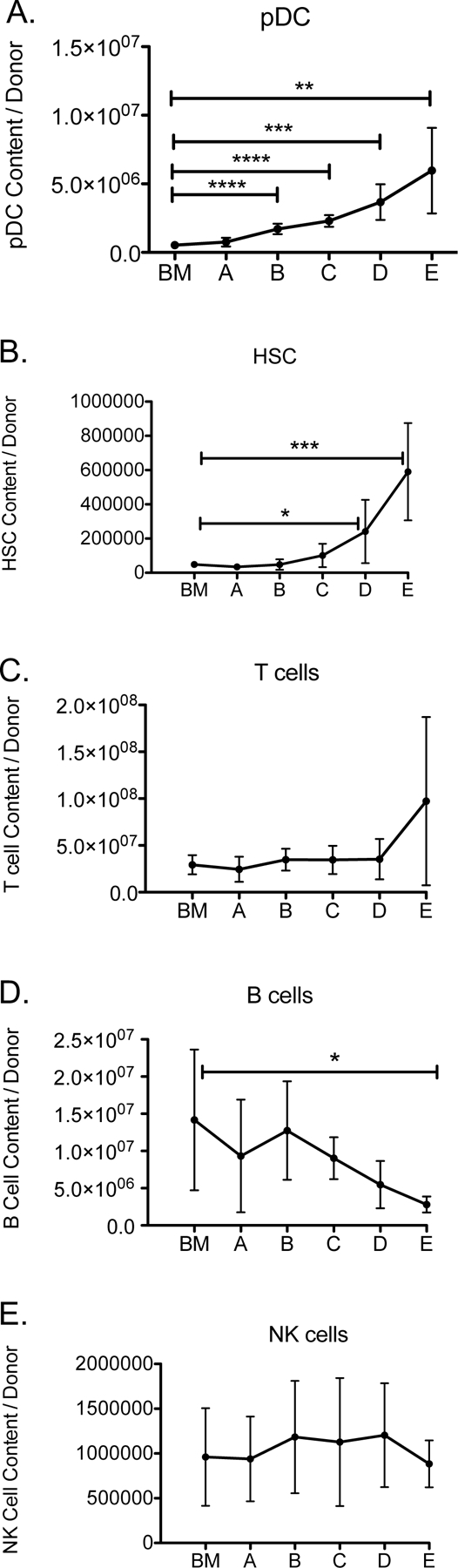

To examine whether Flt3L treatment could enhance pDC content in vivo, we tested the effect of Flt3L administration on murine bone marrow donors due to the known effect of Flt3L in stimulating differentiation and expansion of pDC.30 We measured the content of HSC, pDC, T cell, B cell, and NK in bone marrow from mice treated with different dosing schedules of PBS or Flt3L (Table 1). The increased pDC content in marrow was proportionate to the number of Flt3L doses administered (Figure 1A). HSC, T cell, B cell, and NK cell content was not significantly affected in mice treated with less than 4 doses of Flt3L (Figure 1B–E). A schedule of 2 doses of Flt3L (schedule C) was chosen for all subsequent experiments because pDC content was increased 5-fold without significant differences in the content of other immune cells that might modulate GVHD, including HSC, T cells, B cells, and NK cells.

Table 1. Flt3L administration schedule.

Bone marrow controls were treated with PBS according to the schedule in the table. Experimental mice were treated with 300μg/kg of Flt3L following the schedule in the table.

| Dosage Schedule (Days) |

|---|

| BM: Control |

| A: −7 |

| B: −4 |

| C: −4, −1 |

| D: −7, −5, −3, −1 |

| E: −7, −6, −5, −4, −3, −2, −1 |

Figure 1. Flt3L administration to bone marrow donors increased pDC content in graft.

Mice were treated with PBS or 300μg/kg of Flt3L according to the schedule in Table 1. (A) pDC, (B) HSC, (C) T cell, (D) B cell, and (E) NK cell content were measured by flow cytometry. n=6 per group, combined data from 2 independent experiments. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Flt3L administration to bone marrow donors may affect homing and lineage, but not phenotype of pDC

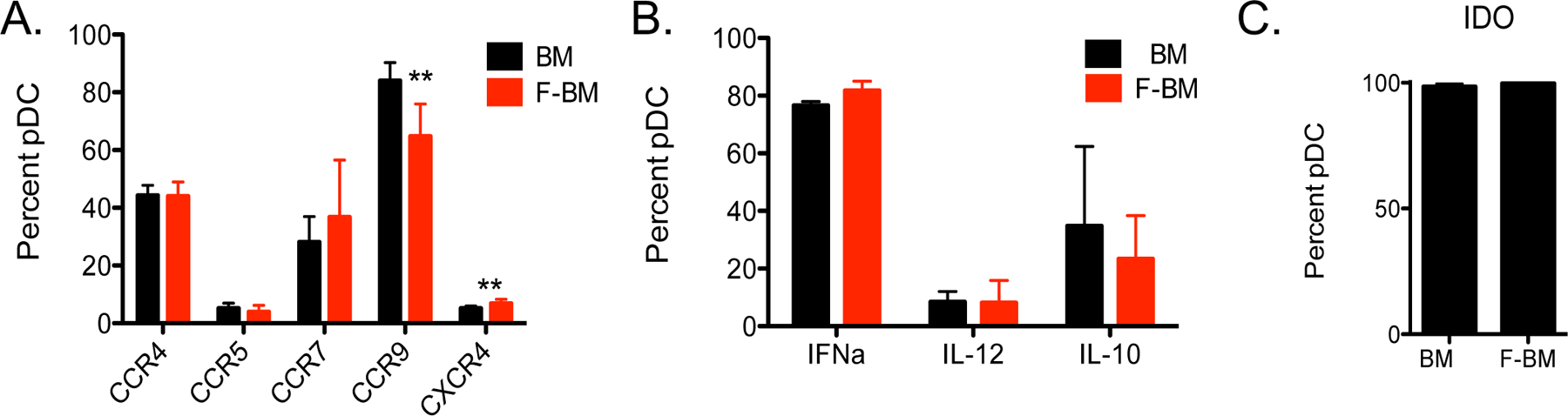

Because homing of donor pDC to GvHD target organs is dependent on their chemokine receptor expression31 we measured expression of CCR4, CCR5, CCR7, CCR9, and CXCR4 on pDC from untreated BM and FBM.32 Mice were treated with PBS or 300μg/kg of Flt3L on days −4 and −1 and bone marrow was harvested. There was significantly less CCR9 and more CXCR4 expression in pDC from FBM compared with control pDC (Figure 2A), suggesting that ability of pDC to migrate to the gut and lymph nodes could be altered by treatment with Flt3L.33, 34

Figure 2. Phenotype of pDC from BM versus FBM grafts are similar.

Mice were treated with PBS or 300μg/kg of Flt3L on days −4 and −1. (A) Surface marker expression of chemokine receptors was measured by flow cytometry. (B) Whole BM or FBM grafts were treated with 50μg of CpG for 9 hours at 37°C. Intracellular staining for cytokine and (C) IDO expression was measured by flow cytometry. n=3–6 per group, from 2 independent experiments. **P < .01.

To better understand the effect of pDC on T cell activation and polarization, we next examined the cytokine profiles and IDO production of pDC from BM and FBM grafts. Flt3L treatment did not result in substantive changes in the levels of IFNα, IL-12, IL-10 and IDO in FBM pDC compared with pDC from untreated BM (Figure 2B–C).

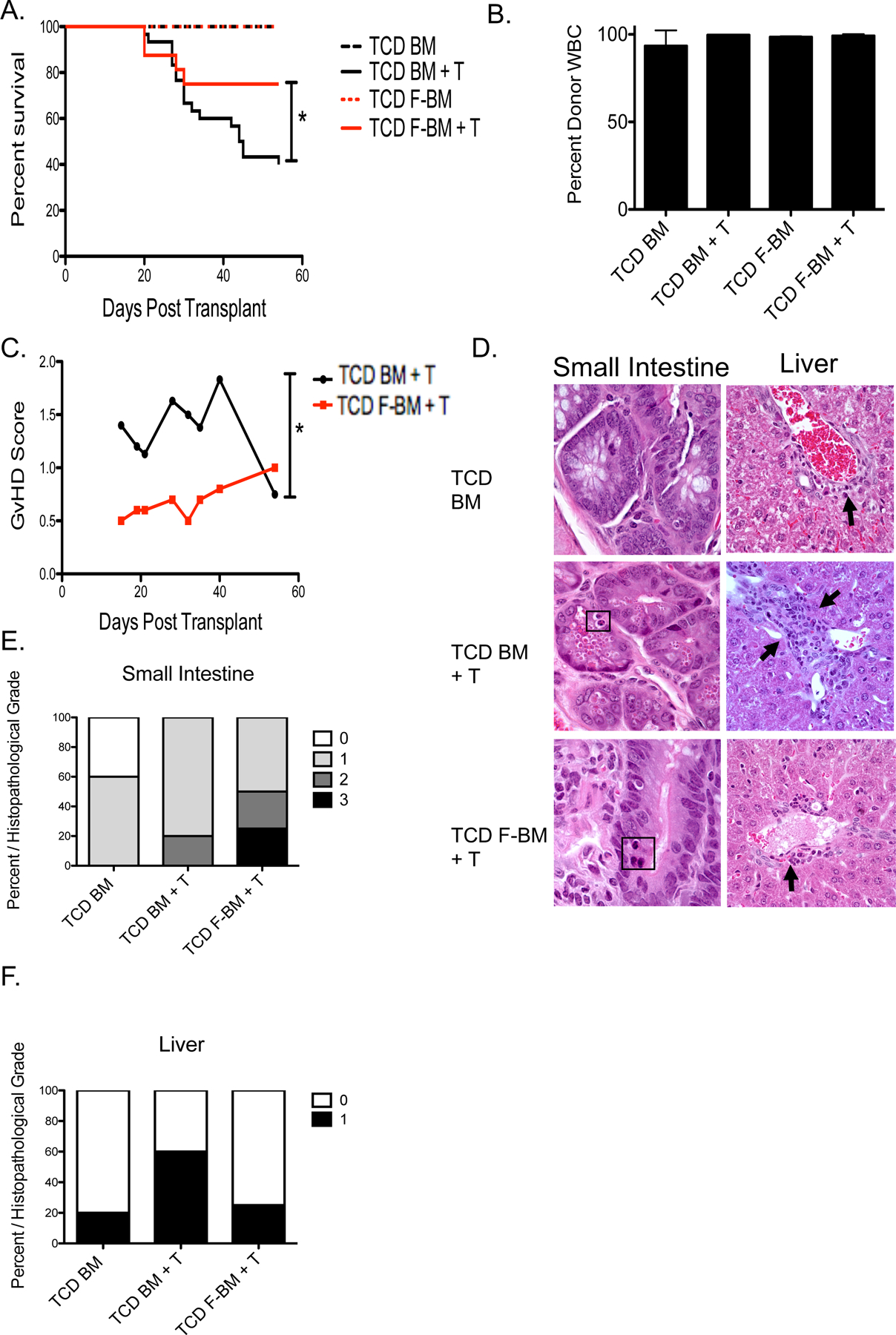

Recipients of FBM had increased survival and less GVHD compared to untreated BM recipients

We next performed a transplant using untreated BM or FBM with the addition of donor T cells form untreated mice to assess the effect of Flt3L-treatment of donor BM on post-transplant survival and GvHD. Lethally irradiated (11 Gy) B10.BR mice were transplanted with 5 million T cell depleted (TCD) BM from C57BL/6 donor mice treated with PBS or 300μg/kg of Flt3L on days −4 and −1 in combination with 4 million T cells from PBS-treated C57BL/6 donor mice. On average, TCD BM grafts consisting of 5 million nucleated cells from PBS-treated donors contained ~50,000 pDC and TCD FBM contained ~250,000 pDC. Mice that received allogeneic TCD FBM with the addition of donor T cells had significantly increased survival compared with recipients of TCD BM plus T cells (Figure 3A). Donor hematopoietic engraftment in all groups was near 100% (Figure 3B). Recipients of TCD FBM plus T cells had significantly lower GvHD than recipients of control TCD BM plus T cells (Figure 3C). Histological analysis of the liver and small intestine showed scant evidence for GvHD pathology in recipients of control TCD BM, without the addition of donor T cells. Using NIH criteria for histological diagnosis of GvHD35–37, and euthanizing mice on day +30 post-transplant, GvHD pathology was not significantly different comparing scoring sections of small intestine or liver between recipients of TCD BM + T cells and TCD FBM + T cells (Figure 3D–E), although the small numbers of mice studies sacrified at this time point and possible differences in sampling of tissue limit the statistical power of this comparison.

Figure 3. Grafts from Flt3L treated donors increased survival and decreased GvHD.

C57BL/6 donor mice were treated with PBS or 300μg/kg of Flt3L on days −4 and −1. B10.BR recipient mice were transplanted with 5 million T cell depleted (TCD) BM or FBM cells with or without the addition of 4 million T cells. (A) Survival of murine transplants recipients. Recipient groups included TCD BM, TCD FBM, TCD BM + 4 million T cells (BMT), and TCD FBM + 4 million T cells (FBMT). *P < .05 represents significance between BMT and FBMT recipients using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. (B) Chimerism of recipients 30 days post-transplant by groups as indicated. (C) Clinical GvHD scores of mice that received T cells. n=30 per group, from 2 independent experiments. *P < .05 represents significance between BMT and FBMT recipients using 2-way ANOVA. (D) Representative histopathological samples of small intestine and liver at day 15 from each treatment group photographed at 600X. Black squares denote apoptotic cells in the small intestine crypts. Histopathological scores of GvHD associated pathology. Score of 0: no pathology, 1: villi shortening, 2: apoptotic cells, 3: loss of crypts. Liver pathology included lymphocytic infiltration to the portal triad and rare apoptotic bile duct epithelial cells (black arrows). (E) Percentage of mice within each group that showed GvHD-associated pathology in the small intestine (F) or liver. n=4–6 per group, from 2 independent experiments.

To isolate the role of pDC from FBM in this transplant model, we transplanted B10.BR recipients with purified 5,000 HSC, 106 T cells, and 50,000 FACS-isolated pDC from FBM or untreated C57BL/6 BM. Recipients of FBM pDC had 90% survival and lower GvHD scores compared to recipients of BM pDC, in which survival was 80% (p=NS; Supplemental Figure 1A–B).

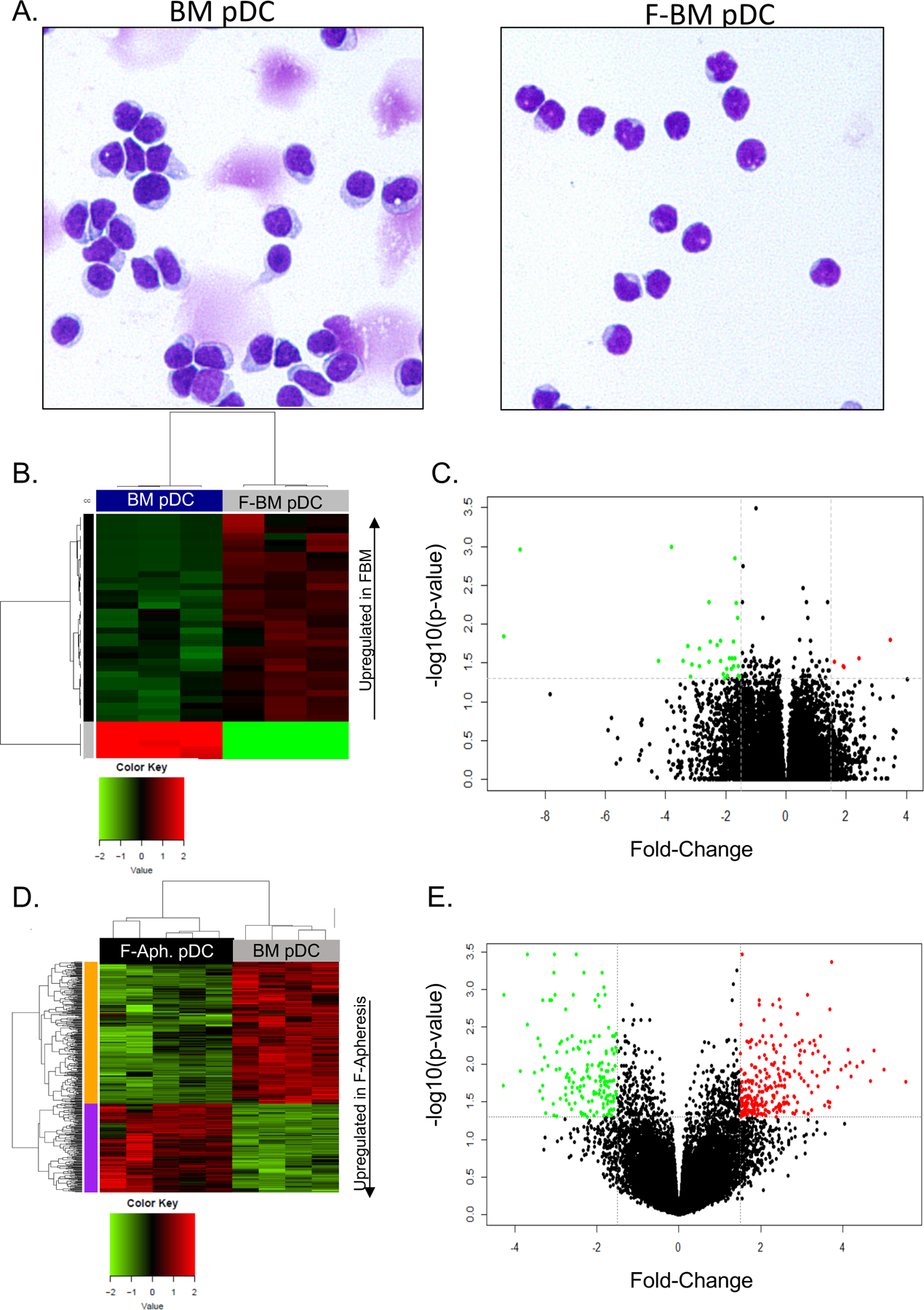

Flt3L treated donors have different gene expression profiles than bone marrow donors

After observing a trend towards increased survival in the group that received an equal number of FACS isolated FBM pDC compared with untreated BM pDC in a model system using purified HSC, T cell, and pDC transplants we hypothesized that quantitative effects of Flt3L treatment on the increased number of pDC in donor marrow is not the sole determinant of improved transplant outcome following Flt3L treatment. Thus, to explore qualitative effects of Flt3L treatment on pDC we analyzed gene expression profiles of pDC from FBM versus BM from untreated donor mice. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells were isolated by FACS from the bone marrow of mice treated with PBS or 300μg/kg of Flt3L on days −4 and −1. RNA was obtained from these purified pDC and sequenced using next generation sequencing. Pairwise analyses were conducted on individual genes and immunological pathways using a p-value cutoff of < .05 (Supplemental Tables 1, 2). FBM pDC have distinct gene expression profiles from pDC from untreated BM grafts (Figure 4A–B). Immunological pathways that showed significant differences (p-value < .05) include the adaptive immune pathways and immune checkpoint pathways. Upregulation of genes in the adaptive immune pathway include APRIL, Hmox1, and Etv5, all of which may affect the ability of donor pDC to regulate T cell polarization and activation.38 Immune checkpoint pathway genes, Bcl2, Cyclin D3, TIM-3, and ACK1, are upregulated in pDC from FBM grafts, suggesting an increased ability for immune cell regulation.39 Finally, pDC from FBM grafts upregulated Tox1 and Prss16, genes that regulate T cell selection in the thymus (Table 2).40, 41

Figure 4. FBM pDC have distinct gene expression profile from BM pDC.

Mice were treated with PBS and 300μg/kg of Flt3L on days −4 and −1. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells were isolated by FACS. RNA was sequenced by next generation sequencing. (A) Heatmap depicting the significantly differentially expressed genes in the murine samples using z-score scaling, 1-pearson correlation distance, and ward.D clustering. (B) Volcano plot of gene upregulation and downregulation (BM vs FBM). n=3 per group. (C) Healthy human donors were untreated or treated with 75μg/kg of CDX-301 (recombinant Flt3L) for 5 consecutive days. Untreated donors underwent bone marrow harvest and Flt3L-treated donors underwent leukapheresis on day 6. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells were isolated by FACS. RNA sequencing was done with Illumina HumanHT-12 v4 beadchip. Heatmap depicting the significantly differentially expressed genes in the human samples using z-score scaling, Euclidean distance, and complete clustering. (D) Volcano plot depicting upregulation and downregulation of genes (BM vs F-Apheresis). n=4–5 per group.

Table 2. Genes upregulated in FBM pDC.

Upregulated genes FBM vs BM in adaptive immune, immune checkpoint and thymic induced T cell selection pathways that are present in Figure 4B plotted Fold Change (logFC) by –log10(p-value).

| Gene | Pathway | logFC | NegLog10pvalue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bcl2 | Immune Checkpoint | −1.66 | 2.27 |

| Cyclin D3 | Immune Checkpoint | −1.60 | 2.08 |

| Etv5 | Adaptive Immunity | −2.30 | 1.73 |

| APRIL | Adaptive Immunity | −3.25 | 1.71 |

| TIM-3 | Immune Checkpoint | −1.79 | 1.56 |

| Tox1 | T cell selection | −4.24 | 1.53 |

| Prss16 | T cell selection | −3.12 | 1.48 |

| Hmox1 | Adaptive Immunity | −1.73 | 1.46 |

| ACK1 | Immune Checkpoint | −1.97 | 1.43 |

In order to better interpret the translational relevance of these murine studies, gene expression profiles were compared between FACS-isolated human pDC from untreated bone marrow donors and pDC isolated from apheresis products of Flt3L-treated sibling donors. Because we did not have access to the bone marrow from healthy human volunteers treated with Flt3L, we used grafts from sibling stem cell donors that underwent mobilization with 5 daily injections of 75 μg/kg of CDX-301 (recombinant Flt3L) as a single mobilization agent from an IRB-approved clinical study (NCT022000380) that assessed the efficacy of Flt3L in mobilizing stem cells, and compared gene expression to pDC isolated from untreated BM acquired on a separate clinical study (NCT02485639). RNA from pDC samples were sequenced by Illumina Chip (Supplemental Tables 3, 4). Similar to the murine gene array analysis, KLRF1 and SLAMF6 in the adaptive immune pathway and BCL2 and BIRC3 in the immune checkpoint pathway were upregulated in pDC from the Flt3L-treated donors compared with pDC from untreated bone marrow volunteers (Figure 4C–D) (Table 3). Additionally, toll like receptor (TLR) genes, including those in the TLR4 pathway, APP, MAP2K6, CD36, ACTG1, and IRF7, were downregulated in Flt3L-treated donor pDC, indicating decreased ability to stimulate innate immune pathways (Table 4).42

Table 3. Genes upregulated in F-Apheresis pDC.

Upregulated genes F-apheresis vs. BM in adaptive immune and immune checkpoint pathways that are present in Figure 4D plotted Fold Change (logFC) by –log10(p-value).

| Gene | Pathway | logFC | NegLog10pvalue |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCL2 | Immune Checkpoint | −2.34 | 1.35 |

| KLRF1 | Adaptive Immunity | −3.70 | 2.53 |

| SLAMF6 | Adaptive Immunity | −2.74 | 2.16 |

| BIRC3 | Immune Checkpoint | −2.37 | 1.58 |

Table 4. Genes downregulated in F-Apheresis pDC.

Downregulated genes in toll-like receptor cascades including the TLR4 pathway that are present in Figure 4D plotted Fold Change (logFC) by –log10(p-value).

| Downregulated in human F-Apheresis pDC | logFC | NegLog10pvalue |

|---|---|---|

| APP | 3.67 | 2.02 |

| MAPK6 | 1.85 | 1.47 |

| CD36 | 3.14 | 2.93 |

| ACTG1 | 1.91 | 1.32 |

| IRF7 | 3.24 | 1.39 |

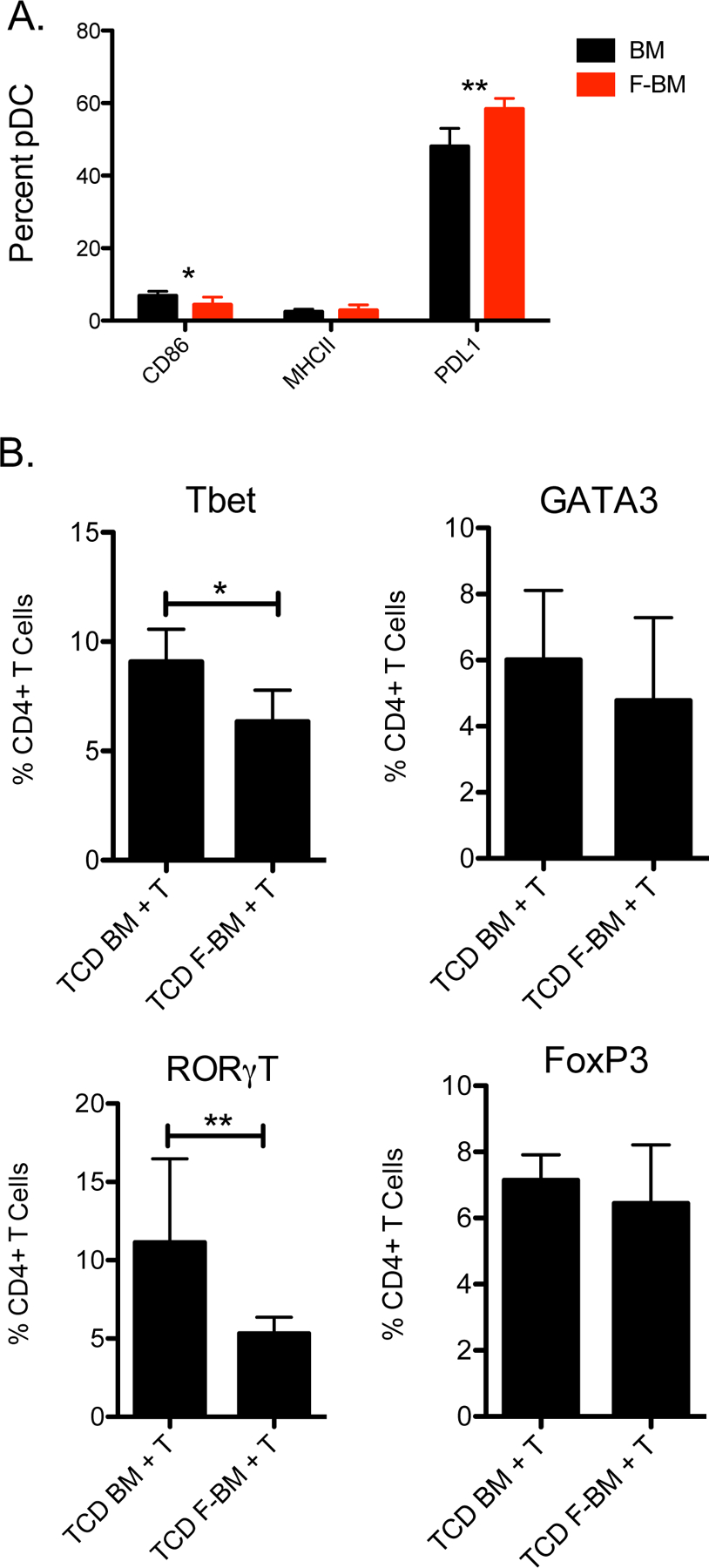

Flt3L bone marrow reduced T cell polarization post transplantation

Based upon the results of the gene array analyses of pDC from Flt3L treated mice and humans, we next studied the ability of pDC to interact with and influence donor T cell activation and immune polarization post-transplant in a non-paracrine cytokine fashion.43, 44 We examined the potential of pDC to stimulate or inhibit allo-activation of T cells by measuring surface expression of MHC II, CD86, and PDL1 on pDC. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells from Flt3L-treated donors expressed less MHC II and CD86 and expressed more PDL1 (Figure 5A). To determine whether changes in surface expression of co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules affects T cell polarization, we performed a C57BL/6→B10.BR transplant with 5 million T cell depleted BM or FBM cells and 4 million untreated T cells. On day 3 post-transplant, donor T cells were analyzed for their content of T cell transcription factors by flow cytometry. Mice that received TCD FBM + 4 million T cells had donor T cells with significantly lower levels of Tbet and RoRγT expression on day 3 post-transplant, consistent with decreased Th1 and Th17 polarization (Figure 5B). To better determine what role pDC placed in the pattern of transcription factor expression in T cells post-transplant, we performed a C57BL/6→B10.BR using purified HSC, T cells, and purified populations of BM or FBM pDC, and again measured T cell transcription factor expression on day 3. The same trend of lower Tbet and RoRγT expression in T cells post-transplant was observed in this experiment as well (Supplemental Figure 2A). The effect of FBM pDC on T cells does not appear to limit T cell proliferation, as T cell proliferation was equivalent comparing the addition of FBM pDC versus untreated BM pDC to T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 beads (Supplemental Figure 3A–B).

Figure 5. Flt3L treatment of bone marrow donors decreased expression of T helper cell transcription factors in recipients.

Donor mice were treated with PBS or 300μg/kg of Flt3L on days −4 and −1. (A) CD86, MHC II, and PDL1 surface expression was measured by flow cytometry. (B) A C57BL/6→B10.BR transplant was performed where recipient mice were transplanted with 5 million T cell depleted BM or FBM cells with the addition of 4 million T cells. Intranuclear staining of transcription factors Tbet, GATA3, RoRγT, and FoxP3 of T cells was assessed by flow cytometry 3 days post-transplant. n=6 per group, combined data from 2 independent experiments. *P < .05.

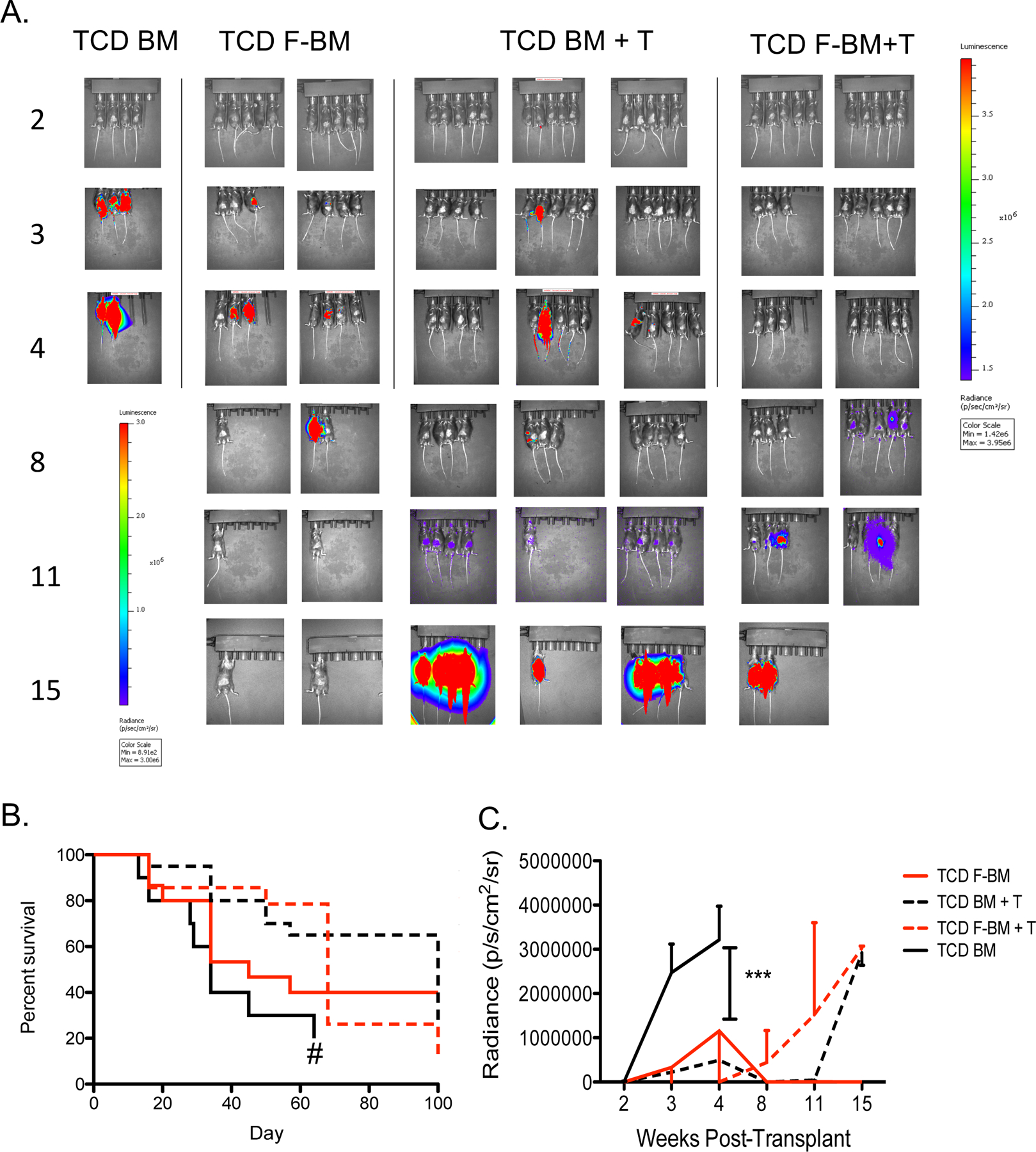

GvL activity was not diminished in recipients of FBM

To determine whether Flt3L treatment of marrow donors affected the GvL activity of the allogeneic transplant, we compared the growth of leukemia cells in recipients of FBM compared with untreated BM using bio-luminescent imaging of luciferase+ leukemia cells and survival analyses of leukemia-bearing transplant recipients. First, C57BL/6 mice were irradiated (11Gy) on day −2, inoculated with 50,000 syngeneic luciferase+ C1498 tumor cells on day −1, and then transplanted with 5 million TCD BM or FBM cells plus 4 million T cells from MHC-mismatched B10.BR donors on day 0. Tumor burden was measured serially by bioluminescence. There was no significant difference in tumor burden comparing recipients of untreated TCD BM plus 4 million T cells versus TCD FBM plus 4 million T cells recipients (Figure 6A–C). Additionally, using the LBRM tumor line in C57BL/6→B10.BR transplant recipients, there was a significant prolongation of survival comparing recipients of TCD FBM plus 4 million T cells to recipients of TCD BM plus 4 million T cells (Supplemental Figure 4A–C).

Figure 6. No loss of GvL effect in recipients of FBM.

B10.BR→ C57BL/6 murine transplant recipients received 5 million T cell depleted bone marrow cells and 4 million T cells. Recipient mice received 50,000 luciferase+ C1498 cells. (A) Serial bioluminescent imaging of recipient mice. (B) Survival curve of murine transplant recipients. (C) Quantification of tumor burden. n=10–15 per group, from 2 independent experiments. *P < .05.

DISCUSSION

GvHD remains the most significant complication following HSCT.45 Although recipients of bone marrow or G-CSF-mobilized grafts from unrelated donors have equal survival up to 7 years post-transplant, there is a higher incidence of chronic GvHD in recipients of G-CSF-mobilized grafts.46, 47 Furthermore, the BMTCTN 0201 study showed that recipients of marrow grafts containing higher numbers of pDC had increased survival and lower treatment related mortality due to less GvHD.7 Results of this study also showed that pDC content of the marrow graft varied greatly amongst volunteer bone marrow donors, raising the question of how to increase the content of immune-regulatory donor pDC in all bone marrow allografts. We report herein that administration of Flt3L to bone marrow donors increased pDC content of the graft and graft recipients of Flt3L-treated bone marrow or purified donor pDC from FBM have increased survival and less GvHD after allo-transplantation.

In our previous studies, we have shown that murine BM donor pDC limit GvHD without attenuating GvL.16, 17 Furthermore, we have unpublished data confirming that with transplantation of allo-grafts containing highly purified HSC, T cells, and pDC, recipients of BM pDC have increased survival and decreased GvHD incidence compared to recipients of G-CSF-mobilized pDC (Hassan 2018, submitted). Thus, data from the current study showed that Flt3L administration to bone marrow donors increased pDC content 5-fold spurred further characterization of the effects of Flt3L treatment on the quantity and quality of pDC in bone marrow and HSCT outcomes. Transplanting 5 million T cell depleted bone marrow cells from Flt3L-treated donors with the addition of 4 million T cells from untreated donors increased survival with decreased GvHD compared with transplantation of an equal number of untreated TCD BM cells and T cells.

Interestingly, although pDC from untreated BM and FBM have a similar phenotype, we show that FBM pDC have an enhanced cell-intrinsic ability to limit GvHD and a gene expression profile that supports greater immune-modulatory capacity compared with pDC from untreated BM in a C57BL/6B10.BR heterogenous transplant model with characteristics of both acute and chronic GvHD, a common aspect of HSCT recipients in a clinical setting (JCI 21). Of note, T cells from recipients of FBM pDC had less Th1 (Tbet) and Th17 (RoRγT) polarization than T cells from recipients of pDC from untreated BM (Figure 5B and Supplemental Figure 2A). Thus the upregulation of adaptive immune and immune checkpoint pathways in pDC from FBM may be responsible for their ability to regulate donor T cell immune polarization, decrease Th1 and Th17 polarization, and limit the incidence and severity of GvHD compared with pDC from untreated BM.47–50 This coupled with increased expression of genes involved in positive and negative selection in the thymus may enable FBM pDC to induce post-transplant tolerance of donor stem cell-derived T cells. Additionally, pDC from Flt3L treated human donors have downregulated the expression of genes involved in TLR cascades and innate immune cell pathways compared with pDC from untreated BM, with the most significant decrease seen in expression of TLR4 pathway genes. Downregulation of the TLR4 pathway may also play a role in limiting GvHD in the gut, because gut GvHD can activate the release of LPS from bacteria, ultimately activating TLR4 on pDC, which can further aggravate injury in the gut and augment GVHD.51–53 Thus, the downregulation of genes involved in TLR cascades and other innate immune pathways in FBM pDC may also play a role in the attenuation of GvHD following transplantation of pDC from FBM.

The present study has some limitations. Although the current studies focus on donor pDC and the effect of Flt3L administration to bone marrow donors on pDC, other donor cell types may contribute to the transplant outcomes following Flt3L treatment of BM donors. We have shown with one dose and one schedule of Flt3L administration (day −4 and day −1 with respect to marrow harvest), there is a significant increase in content and quality of the pDC. Although there was no significant change in content of HSC, NK cells, T cells, and B cells in Flt3L-treated donor bone marrow grafts, determining the effect of Flt3L administration on the cell-intrinsic qualities of these cells to interact with donor T cells and regulate immune responses may further clarify the mechanisms that result in increased survival and decreased GvHD in FBM recipients.47 Thus, the clinical utility of Flt3L treatment of human bone marrow donors could be studied by characterizing the effect on immune cell content and quality within the bone marrow graft. Among volunteers treated with Flt3L, some previous phase 1 studies have shown safety of daily administration for a week or more.22 Additionally, we did not test the ability of peripheral blood mobilized Flt3L grafts to affect transplant outcomes, because we observed that HSC and pDC mobilization was not equivalent to G-CSF mobilization (Supplemental Figure 5A–B). Furthermore, Flt3L as a single agent for stem cell mobilization is not efficient (Clinical trial NCT022000380) and Flt3L would need to be combined with other agents such as CXCR4 antagonists for this approach to be feasible for clinical practice. Additionally, we compared gene expression in different sources of Flt3L-stimulated pDC in mice and humans, isolating FBM pDC from Ftl3L-treated mouse BM and F-apheresis pDC from human donor apheresis products due to the lack of available human FBM samples. Nevertheless, the similarities in gene expression between pDC from murine samples and human samples, and the striking findings of improved survival with less GVHD in the murine transplant models suggest that characterization of pDC from bone marrow of Flt3L-treated human donors is warranted in a planned clinical study to further validate the clinical translation potential of these findings.

To summarize, we report a novel method using Flt3L treatment of bone marrow donors to reduce the GvHD-promoting activity of marrow graft and marrow pDC and improve survival of allogeneic BM transplant recipients. Flt3L treatment increased the content and immune-regulatory capacity of pDC in bone marrow grafts, leading to decreased severity of GvHD in murine recipients. Notably, the reduction of GvHD activity following Flt3L treatment of BM donors was not associated with an attenuation of the GvL activity of donor T cells. Thus, the present pre-clinical data provide an impetus to test the clinical effect of Flt3L treatment of bone marrow donors as a novel method to improve transplant outcomes.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Flt3L treatment of murine bone marrow donors significantly increases pDC content

Flt3L-treated bone marrow donor grafts increased survival and decreased GvHD

Flt3L-treated bone marrow donor grafts do not diminish the graft-versus-tumor effect

Flt3L-treated bone marrow donor pDC upregulate genes in adaptive immune pathways

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT AND GRANT SUPPORT

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant 5R01-CA188523. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource and Emory Integrated Genomics Core (EIGC) Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and NIH/NCI under award number P30CA138292. This work was supported by the Research Pathology Shared Resource and the Cancer Animal Models of Winship Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Meuwissen HJ, Gatti RA, Terasaki PI, Hong R, Good RA. Treatment of lymphopenic hypogammaglobulinemia and bone-marrow aplasia by transplantation of allogeneic marrow. Crucial role of histocompatiility matching. N Engl J Med 1969; 281(13): 691–697. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196909252811302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Update of recommendations for the use of hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors: evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14(6): 1957–1960. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dale DC, Bonilla MA, Davis MW, Nakanishi AM, Hammond WP, Kurtzberg J et al. A randomized controlled phase III trial of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim) for treatment of severe chronic neutropenia. Blood 1993; 81(10): 2496–2502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrara JL, Yanik G. Acute graft versus host disease: pathophysiology, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2005; 3(5): 415–419, 428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattsson J Recent progress in allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2008; 10(4): 343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Impola U, Larjo A, Salmenniemi U, Putkonen M, Itala-Remes M, Partanen J. Graft Immune Cell Composition Associates with Clinical Outcome of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with AML. Front Immunol 2016; 7: 523. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waller EK, Logan BR, Harris WA, Devine SM, Porter DL, Mineishi S et al. Improved survival after transplantation of more donor plasmacytoid dendritic or naive T cells from unrelated-donor marrow grafts: results from BMTCTN 0201. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(22): 2365–2372. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy V, Iturraspe JA, Tzolas AC, Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold J, Wingard JR. Low dendritic cell count after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation predicts relapse, death, and acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2004; 103(11): 4330–4335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collin M, McGovern N, Haniffa M. Human dendritic cell subsets. Immunology 2013; 140(1): 22–30. doi: 10.1111/imm.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu Rev Immunol 2013; 31: 563–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cella M, Facchetti F, Lanzavecchia A, Colonna M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells activated by influenza virus and CD40L drive a potent TH1 polarization. Nat Immunol 2000; 1(4): 305–310. doi: 10.1038/79747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banovic T, Markey KA, Kuns RD, Olver SD, Raffelt NC, Don AL et al. Graft-versus-host disease prevents the maturation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol 2009; 182(2): 912–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auletta JJ, Devine SM, Waller EK. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: benefit or burden? Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51(3): 333–343. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koyama S, Aoshi T, Tanimoto T, Kumagai Y, Kobiyama K, Tougan T et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells delineate immunogenicity of influenza vaccine subtypes. Sci Transl Med 2010; 2(25): 25ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darlak KA, Wang Y, Li JM, Harris WA, Owens LM, Waller EK. Enrichment of IL-12-producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells in donor bone marrow grafts enhances graft-versus-leukemia activity in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013; 19(9): 1331–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Y, Giver CR, Sharma A, Li JM, Darlak KA, Owens LM et al. IFN-gamma and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase signaling between donor dendritic cells and T cells regulates graft versus host and graft versus leukemia activity. Blood 2012; 119(4): 1075–1085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-322891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu Y, Waller EK. Dichotomous role of interferon-gamma in allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009; 15(11): 1347–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Amico A, Wu L. The early progenitors of mouse dendritic cells and plasmacytoid predendritic cells are within the bone marrow hemopoietic precursors expressing Flt3. J Exp Med 2003; 198(2): 293–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YL, Chang S, Chen TT, Lee CK. Efficient Generation of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell from Common Lymphoid Progenitors by Flt3 Ligand. PLoS One 2015; 10(8): e0135217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angelov GS, Tomkowiak M, Marcais A, Leverrier Y, Marvel J. Flt3 ligand-generated murine plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cells differ in their capacity to prime naive CD8 T cells and to generate memory cells in vivo. J Immunol 2005; 175(1): 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biswas M, Sarkar D, Kumar SR, Nayak S, Rogers GL, Markusic DM et al. Synergy between rapamycin and FLT3 ligand enhances plasmacytoid dendritic cell-dependent induction of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg. Blood 2015; 125(19): 2937–2947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-599266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anandasabapathy N, Breton G, Hurley A, Caskey M, Trumpfheller C, Sarma P et al. Efficacy and safety of CDX-301, recombinant human Flt3L, at expanding dendritic cells and hematopoietic stem cells in healthy human volunteers. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015; 50(7): 924–930. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaglowski S, Waller EK, Kindwall-Keller TL, McCarty JM, Dugan M, Yellin M et al. Preliminary Safety and Efficacy Data Using CDX-301 (Flt3 ligand) As a Sole Agent to Mobilize Hematopoietic Cells Prior to HLA-Matched Sibling Donor Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Tr 2016; 22(3): S324–S325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.11.801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waller EK, Ship AM, Mittelstaedt S, Murray TW, Carter R, Kakhniashvili I et al. Irradiated donor leukocytes promote engraftment of allogeneic bone marrow in major histocompatibility complex mismatched recipients without causing graft-versus-host disease. Blood 1999; 94(9): 3222–3233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooke KR, Kobzik L, Martin TR, Brewer J, Delmonte J, Jr., Crawford JM et al. An experimental model of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after bone marrow transplantation: I. The roles of minor H antigens and endotoxin. Blood 1996; 88(8): 3230–3239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43(7): e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 2010; 11(10): R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 2003; 13(11): 2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu G, Dawson E, Duong A, Haw R, Stein L. ReactomeFIViz: a Cytoscape app for pathway and network-based data analysis. F1000Res 2014; 3: 146. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.4431.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyman SD, Jacobsen SE. c-kit ligand and Flt3 ligand: stem/progenitor cell factors with overlapping yet distinct activities. Blood 1998; 91(4): 1101–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson PJ, Krensky AM. Chemokines, chemokine receptors, and allograft rejection. Immunity 2001; 14(4): 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosoba S, Harris WA, Lin KL, Waller EK. Chemokine and lymph node homing receptor expression on pDC vary by graft source. Oncoimmunology 2014; 3(10): e958957. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.958957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wendland M, Czeloth N, Mach N, Malissen B, Kremmer E, Pabst O et al. CCR9 is a homing receptor for plasmacytoid dendritic cells to the small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104(15): 6347–6352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609180104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penna G, Sozzani S, Adorini L. Cutting edge: selective usage of chemokine receptors by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol 2001; 167(4): 1862–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shulman HM, Kleiner D, Lee SJ, Morton T, Pavletic SZ, Farmer E et al. Histopathologic diagnosis of chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: II. Pathology Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006; 12(1): 31–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobsohn DA, Vogelsang GB. Acute graft versus host disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007; 2: 35. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snover DC. Acute and chronic graft versus host disease: histopathological evidence for two distinct pathogenetic mechanisms. Hum Pathol 1984; 15(3): 202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKenna K, Beignon AS, Bhardwaj N. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: linking innate and adaptive immunity. J Virol 2005; 79(1): 17–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.17-27.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ray A, Das DS, Song Y, Richardson P, Munshi NC, Chauhan D et al. Targeting PD1-PDL1 immune checkpoint in plasmacytoid dendritic cell interactions with T cells, natural killer cells and multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia 2015; 29(6): 1441–1444. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkinson B, Chen JY, Han P, Rufner KM, Goularte OD, Kaye J. TOX: an HMG box protein implicated in the regulation of thymocyte selection. Nat Immunol 2002; 3(3): 272–280. doi: 10.1038/ni767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klein L, Hinterberger M, Wirnsberger G, Kyewski B. Antigen presentation in the thymus for positive selection and central tolerance induction. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9(12): 833–844. doi: 10.1038/nri2669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int Immunol 2005; 17(1): 1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young LJ, Wilson NS, Schnorrer P, Proietto A, ten Broeke T, Matsuki Y et al. Differential MHC class II synthesis and ubiquitination confers distinct antigen-presenting properties on conventional and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 2008; 9(11): 1244–1252. doi: 10.1038/ni.1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mouries J, Moron G, Schlecht G, Escriou N, Dadaglio G, Leclerc C. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells efficiently cross-prime naive T cells in vivo after TLR activation. Blood 2008; 112(9): 3713–3722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-146290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Antin JH. Thomas’ hematopoietic cell transplantation : stem cell transplantation, Fifth edition. edn John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom; Hoboken, NJ, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee SJ, Logan B, Westervelt P, Cutler C, Woolfrey A, Khan SP et al. Comparison of Patient-Reported Outcomes in 5-Year Survivors Who Received Bone Marrow vs Peripheral Blood Unrelated Donor Transplantation: Long-term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2(12): 1583–1589. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacDonald KP, Hill GR, Blazar BR. Chronic graft-versus-host disease: biological insights from preclinical and clinical studies. Blood 2017; 129(1): 13–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-06-686618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill GR, Olver SD, Kuns RD, Varelias A, Raffelt NC, Don AL et al. Stem cell mobilization with G-CSF induces type 17 differentiation and promotes scleroderma. Blood 2010; 116(5): 819–828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-256495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antin JH, Ferrara JL. Cytokine dysregulation and acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood 1992; 80(12): 2964–2968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teshima T, Reddy P, Lowler KP, KuKuruga MA, Liu C, Cooke KR et al. Flt3 ligand therapy for recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplants expands host CD8 alpha(+) dendritic cells and reduces experimental acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2002; 99(5): 1825–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrara JL. The cytokine modulation of acute graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant 1998; 21 Suppl 3: S13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raetz CR. Biochemistry of endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem 1990; 59: 129–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koyama M, Cheong M, Markey KA, Gartlan KH, Kuns RD, Locke KR et al. Donor colonic CD103+ dendritic cells determine the severity of acute graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med 2015; 212(8): 1303–1321. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.